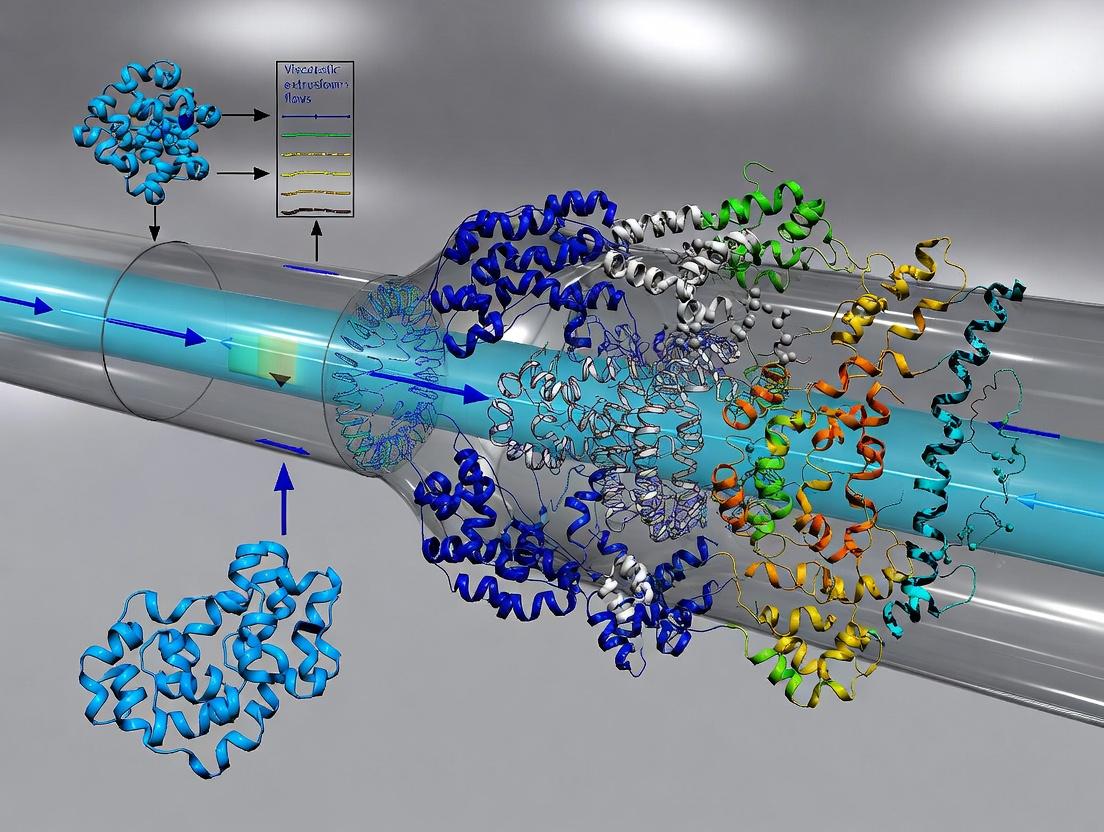

Advanced 3D Finite Element Modeling for Viscoelastic Extrusion Flows: From Theory to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 3D Finite Element Modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows, critical in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes like hot-melt extrusion and 3D bioprinting.

Advanced 3D Finite Element Modeling for Viscoelastic Extrusion Flows: From Theory to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 3D Finite Element Modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows, critical in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes like hot-melt extrusion and 3D bioprinting. It explores the foundational principles of viscoelasticity and numerical methods, details step-by-step methodologies for model implementation and application to drug-loaded polymer melts, addresses common numerical instabilities and optimization strategies, and validates models against experimental data. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource bridges computational modeling with practical challenges in controlled drug delivery system development.

Understanding Viscoelasticity and FEM Fundamentals for Extrusion Flow Analysis

Viscoelasticity is the property of materials that exhibit both viscous (liquid-like) and elastic (solid-like) characteristics when undergoing deformation. This dual nature fundamentally distinguishes polymer melts from simple Newtonian fluids like water. In the context of 3D Finite Element Modeling (FEM) for extrusion flows, accurately capturing viscoelasticity is critical for predicting phenomena such as die swell, melt fracture, and residual stresses, which are absent in purely viscous flows.

Quantitative Comparison: Water vs. Polymer Melt

The table below summarizes the key quantitative differences in rheological behavior.

Table 1: Rheological Properties of Water vs. A Generic Polymer Melt (e.g., Polyethylene)

| Property | Water (Newtonian) | Polymer Melt (Viscoelastic) | Implications for Extrusion Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity (η) | Constant (~1 mPa·s at 20°C). Independent of shear rate. | Shear-thinning: Decreases with increasing shear rate (e.g., from 10^3 to 10^2 Pa·s). | Pressure drop and flow rate are non-linearly related. FEM must use a constitutive model like Power Law or Carreau. |

| Elasticity | None. No energy storage upon deformation. | Significant. Stores deformation energy. Quantified by First Normal Stress Difference (N₁). | Causes die swell (extrudate is larger than die diameter). Requires modeling of elastic recovery. |

| Relaxation Time (λ) | ~10^-12 s (instantaneous relaxation). | Finite and long (e.g., 0.1 - 10 seconds). | Flow history matters. Stress depends on deformation rate and time. FEM requires differential/constitutive models (e.g., Upper-Convected Maxwell). |

| Response to Shear | Shear stress (σ) linear with shear rate (γ̇): σ = η γ̇. | Non-linear. Requires complex models: e.g., σ = ∫ G(t-t') γ̇(t') dt' (Memory integral). | Flow simulation is computationally intensive, requiring iterative solvers and memory of past states. |

| Extensional Viscosity | Trouton's ratio ~3. Constant. | Strain-hardening: Extensional viscosity can increase dramatically with stretch rate. | Influences stretching flows at the die entry and draw-down. Critical for fiber spinning modeling. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Viscoelasticity

Protocol 3.1: Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) Test

Purpose: To characterize the linear viscoelastic modulus (storage G' and loss G'') without disrupting the material's structure. Equipment: Controlled-stress or controlled-strain rheometer with parallel plate or cone-and-plate geometry. Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Place polymer melt sample between pre-heated plates. Trim excess. Ensure no bubbles.

- Temperature Equilibrium: Allow sample to equilibrate at test temperature (e.g., 200°C) for 5-10 minutes.

- Strain Amplitude Sweep: At a fixed frequency (e.g., 1 rad/s), apply oscillatory strain from 0.1% to 100%. Identify the Linear Viscoelastic Region (LVR) where G' and G'' are constant.

- Frequency Sweep: Within the LVR (e.g., at 5% strain), perform a frequency sweep from 0.01 to 100 rad/s.

- Data Analysis: Plot G'(ω) and G''(ω). The crossover point (G' = G'') indicates the approximate relaxation time (λ ≈ 1/ω_crossover). The plateau in G' at high frequencies indicates the entanglement modulus.

Protocol 3.2: Capillary Rheometry for Shear Viscosity and Die Swell

Purpose: To measure shear-dependent viscosity and observe elastic die swell under conditions relevant to extrusion. Equipment: Capillary rheometer with a reservoir, piston, pressure transducer, and interchangeable dies (various L/D ratios). Procedure:

- Barrel Filling: Load polymer pellets into the pre-heated barrel. Compact and purge to remove air.

- Steady Shear Tests: Drive the piston at constant speeds to achieve a range of wall shear rates (e.g., 10 to 10,000 s^-1). Record the steady-state pressure drop (ΔP) for each speed.

- Bagley Correction: For each shear rate, repeat tests with dies of the same diameter but different lengths. Plot ΔP vs. L/D to correct for entrance pressure losses (extrapolate to zero length to find "end correction").

- Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch Correction: Apply correction to shear rate for non-parabolic velocity profile in non-Newtonian fluids.

- Die Swell Measurement: Extrude a strand at a defined shear rate and temperature. Allow it to cool. Measure the diameter of the cooled strand (Df) versus the die diameter (D0). Die Swell Ratio = Df / D0.

- Data Analysis: Calculate true shear stress and viscosity. Plot viscosity vs. shear rate (log-log). Correlate die swell ratio with shear stress or first normal stress difference.

Diagram: The Viscoelastic Response Workflow

Viscoelastic Response to Deformation

Diagram: 3D FEM for Viscoelastic Extrusion Workflow

3D FEM Workflow for Viscoelastic Extrusion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Viscoelastic Polymer Melt Characterization

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibrate rheometers and validate experimental protocols. Provide known rheological properties. | NIST Polyethylene SRM 2490 (for melt viscosity). |

| Thermally Stable Polymers | Model systems for fundamental studies, minimizing degradation during long tests. | Polystyrene (narrow MWD), Polyethylene, Polypropylene. |

| Antioxidant Additives | Prevent oxidative degradation of polymer melts during high-temperature testing. | Irganox 1010, BHT. Added at ~0.1 wt%. |

| Silicone Oil or Inert Gas Blanket | Creates an oxygen-free environment in the rheometer to prevent degradation. | Applied around sample edges or as a purge gas. |

| Partitioned Plate Geometries | Minimize edge fracture during large deformation tests (e.g., extensional rheometry). | Sentmanat Extensional Rheometry (SER) fixtures. |

| High-Temperature Grease | Seal gaps in fixtures to prevent sample leakage. | Silicon-based grease stable >250°C. |

| Solvents for Cleaning | Thoroughly remove polymer residue from rheometer tools after testing. | Xylene (for polyolefins), DCM (for polystyrene). |

| Non-Newtonian Fluid Standards | Verify shear-thinning and viscoelastic calculations in CFD/FEM software. | Aqueous polyacrylamide or polyvinylpyrrolidone solutions. |

The Critical Role of Extrusion in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing (HME, 3D Printing)

Extrusion technologies, specifically Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) and its integration with 3D Printing (Fused Deposition Modeling), are transformative for pharmaceutical manufacturing. They enable the production of amorphous solid dispersions, controlled-release formulations, and personalized dosage forms. This document details application notes and experimental protocols, framed within a research thesis utilizing 3D finite element modeling (FEM) to simulate viscoelastic polymer melt flow during extrusion, aiming to optimize process parameters and predict product performance.

Table 1: Key Material Properties for HME & Pharmaceutical 3D Printing

| Material/Polymer | Tg (°C) | Melt Temp (°C) | Typical Drug Load (%) | Solubility Parameter (MPa^1/2) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluplus | 70 | 70-80 | 10-40 | ~21.1 | Amorphous dispersions |

| Eudragit E PO | 48 | 50-60 | 10-50 | ~20.3 | Taste masking, immediate release |

| PVA (Filament) | 85 | 190-220 | 1-10 | ~25.8 | FDM 3D printing of tablets |

| PLGA | 45-55 | N/A (Extruded) | 10-70 | ~21.9 | Long-acting implantables |

| HPMC (HPMCAS) | 120 | N/A (Thermally processed) | 10-30 | ~23.4 | Enteric coatings, stability |

Table 2: Impact of Key Extrusion Parameters on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

| Process Parameter | Typical Range (HME) | Typical Range (FDM) | Primary Influence on CQA | FEM Modeling Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrel Temperature | 80-180°C | 160-250°C (Nozzle) | Drug degradation, Amorphicity | Thermal boundary condition |

| Screw Speed | 50-500 rpm | N/A | Residence time, Shear stress | Rotational velocity, Shear rate |

| Feed Rate | 0.2-5 kg/hr | 0.5-2 mm/s (Flow) | Mixing homogeneity, Porosity | Mass inflow rate |

| Die Diameter | 2-5 mm | 0.2-0.8 mm (Nozzle) | Die swell, Melt pressure | Geometry, Exit boundary condition |

| Cooling Rate | 10-50°C/s (Calender) | N/A | Crystallinity, Stability | Heat transfer coefficient |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Hot-Melt Extrusion for Amorphous Solid Dispersion

Objective: To manufacture an ASD of itraconazole using Soluplus via twin-screw HME. Materials: Itraconazole (API), Soluplus (carrier), co-rotating twin-screw extruder, differential scanning calorimeter (DSC), X-ray powder diffractometer (XRPD). Method:

- Pre-blending: Geometrically mix itraconazole and Soluplus (30:70 w/w) in a turbula mixer for 15 min.

- Extrusion: Feed pre-blend into extruder at 2 kg/hr. Set barrel temperature profile from feed to die: 130/140/150/155°C. Maintain screw speed at 200 rpm.

- Processing: Collect the molten strand, cool on a conveyor belt at 20°C, and pelletize.

- Analysis: Assess amorphicity by DSC (heating rate 10°C/min) and XRPD (5-40° 2θ range). FEM Context: Model this flow to correlate shear rate (from screw speed) with mixing efficiency and predict temperature homogeneity using viscoelastic (Oldroyd-B) constitutive equations.

Protocol 3.2: Fabrication of Personalized Printlets via FDM 3D Printing

Objective: To produce immediate-release printlets using a drug-loaded PVA filament. Materials: HME-produced PVA/paracetamol filament (5% drug load), desktop FDM 3D printer, slicing software, USP dissolution apparatus II. Method:

- Filament Preparation: Manufacture filament per Protocol 3.1 using a single-screw strand extruder and PVA with API.

- Design & Slicing: Design a 10mm diameter, 3mm height tablet (approx. 500 mg) in CAD. Export as STL, slice with 100% infill, 0.2mm layer height, and a rectilinear pattern.

- Printing: Load filament, set nozzle temp to 200°C, bed temp to 60°C, and printing speed to 30 mm/s. Execute print.

- Dissolution Testing: Test printlet in 900 mL pH 6.8 phosphate buffer at 37°C, 50 rpm paddle speed. Sample at 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 min. FEM Context: Model the non-Newtonian, viscoelastic flow through the FDM nozzle to understand shear-thinning behavior and predict strand deposition accuracy for dimensional fidelity.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: HME to FDM Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Workflow

Diagram Title: 3D FEM for Extrusion Process Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HME & Pharmaceutical 3D Printing Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Brand/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Carriers | Form matrix for amorphous solid dispersions; govern release profile. | Soluplus, Eudragit series, PVA, PLGA, HPMCAS |

| Plasticizers | Lower polymer Tg and melt viscosity, enabling processing at lower temps. | Triethyl citrate, Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Dibutyl sebacate |

| Melt Flow Index Tester | Empirically measures polymer melt viscosity under standardized conditions. | Key capillary rheometer data feeds FEM model validation. |

| Twin-Screw Extruder (Lab-scale) | Provides scalable, continuous mixing and conveying of API-polymer blends. | 11mm or 16mm co-rotating twin-screw extruder. |

| Desktop FDM 3D Printer (Pharma-modified) | Enables small-batch, on-demand printing of complex dosage forms. | Printer with enclosed chamber, precision temperature control. |

| Hot-Stage Microscopy | Visually observes API melting and dissolution into polymer in real-time. | Crucial for initial screening of API-polymer miscibility. |

| Rheometer (Rotational & Capillary) | Characterizes viscoelastic melt properties for constitutive model input. | Data (G', G'', complex viscosity) essential for accurate FEM. |

| Stability Chamber | Assesses physical stability (recrystallization) of ASDs under ICH conditions. | Critical for confirming predicted performance from models. |

Core FEM Concepts in Fluid Dynamics

The Finite Element Method provides a robust framework for approximating solutions to complex systems of partial differential equations governing fluid flow. For viscoelastic extrusion flows, the method discretizes the domain into finite elements, transforming the continuous problem into a solvable algebraic system.

Key Governing Equations for Viscoelastic Flow:

- Conservation of Mass (Continuity): ∇·u = 0

- Conservation of Momentum: ρ(∂u/∂t + u·∇u) = -∇p + ∇·τ + f

- Constitutive Equation (e.g., Oldroyd-B): τ + λ₁ τ∇ = 2η₀ (D + λ₂ D∇)

Where u is velocity, p is pressure, τ is the extra-stress tensor, D is the rate-of-deformation tensor, ρ is density, η₀ is zero-shear viscosity, λ₁ is relaxation time, and λ₂ is retardation time.

Application Notes for Viscoelastic Extrusion Modeling

Model Formulation and Challenges

Modeling viscoelastic extrusion flows in 3D presents specific challenges addressed by FEM:

- High Weissenberg Number Problem (HWNP): Numerical instabilities as elasticity (Weissenberg number, Wi) increases. Stabilized formulations (SUPG, GLS) are essential.

- Mixed Formulations: Velocity, pressure, and stress fields require inf-sup stable element pairs (e.g., Taylor-Hood elements for velocity-pressure).

- Free Surface Tracking: The extrudate swell interface requires techniques like the Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) method or Level Set approaches.

Table 1: Common Constitutive Models for Polymer Extrusion

| Model | Equation (Differential Form) | Parameters | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper-Convected Maxwell (UCM) | τ + λ₁ τ∇ = 2η₀ D | λ₁, η₀ | Benchmark, highly elastic melts |

| Oldroyd-B | τ + λ₁ τ∇ = 2η₀ (D + λ₂ D∇) | λ₁, λ₂, η₀ | Boger fluids, solvent-polymer mix |

| Giesekus | τ + λ₁ τ∇ + (αλ₁/η₀) τ·τ = 2η₀ D | λ₁, η₀, α (mobility) | Shear-thinning polymers |

| Phan-Thien–Tanner (PTT) | Y(tr(τ))τ + λ₁ τ∇ = 2η₀ D | λ₁, η₀, ε, ξ | Broad range of polymer melts |

Table 2: Comparison of Stabilization Techniques for HWNP

| Technique | Mechanism | Added Term | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streamline-Upwind/Petrov-Galerkin (SUPG) | Adds diffusion along streamlines | τ_SUPG(u·∇δu)·R | Effective for convection dominance | Can over-diffuse stress |

| Galerkin/Least-Squares (GLS) | Minimizes residual in least-squares sense | τ_GLS L(δu)·R | More robust for mixed problems | Higher computational cost |

| Log-Conformation Representation (LCR) | Reformulates constitutive equation | Solves for log(τ) instead of τ | Extremely stable at high Wi | Complex implementation |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Numerical Simulation of Axisymmetric Die Swell

Aim: To simulate the viscoelastic extrudate swell from a cylindrical die and compare swell ratio with experimental/theoretical data. Materials: FEM software (e.g., COMSOL, ANSYS Polyflow, or open-source FEniCS), high-performance computing cluster. Methodology:

- Geometry & Mesh: Create a 2D axisymmetric domain comprising the die channel (length L=10R) and a large exterior region for the swell. Use a refined, boundary-fitted mesh with high density at the die exit and free surface.

- Physics Setup:

- Select a viscoelastic constitutive model (e.g., Oldroyd-B).

- Apply a fully-developed velocity profile (Poiseuille) at the inlet.

- Set zero traction (neutral) at the outlet.

- Apply no-slip condition on die walls.

- Define the free surface using an ALE moving mesh with surface tension.

- Solver Configuration:

- Use a segregated solver: solve flow field (u-p), then stress field.

- Implement a GLS stabilization scheme.

- Employ an adaptive time-stepping scheme, starting with a small time step.

- Analysis: Calculate the steady-state swell ratio (final extrudate radius / die radius) as a function of the Weissenberg number (Wi = λ₁ * U_avg / R).

Protocol: 3D Simulation of Square-Die Extrusion with Corner Vortices

Aim: To capture secondary flows and corner vortex patterns in the extrusion of a viscoelastic fluid through a square cross-section die. Methodology:

- 3D Geometry: Model the die with a square cross-section and sufficient entry length.

- Mesh: Utilize hexahedral elements with local refinement near the corners and walls.

- Boundary Conditions: As per Protocol 3.1, but with a 3D parabolic inlet profile.

- Solver: Use a parallelized coupled solver for efficiency. The log-conformation formulation is recommended for stability.

- Post-Processing: Visualize and quantify the intensity of the secondary flow vectors in the cross-sectional plane and the development of corner vortices along the die length.

Visualization: Workflows and Relationships

Title: FEM Workflow for Viscoelastic Flow Analysis

Title: From Material Parameters to Solver Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Components for 3D FEM Viscoelastic Extrusion Research

| Item / "Reagent" | Function in the Research Context |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Constitutive Model (e.g., PTT, Giesekus) | Defines the mathematical relationship between stress, strain, and strain rate for the viscoelastic fluid. Crucial for accurate physics. |

| Stabilization Scheme (SUPG, GLS, LCR) | "Stabilizing agent" against numerical instability (HWNP). Allows solutions at practically relevant high Weissenberg numbers. |

| Mixed Finite Element Formulation (e.g., P2-P1 for u-p) | The core "reaction vessel." Ensures compatibility between interpolation spaces for velocity and pressure, preventing spurious oscillations. |

| Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) Algorithm | Dynamically concentrates computational elements in regions of high stress gradient (e.g., die lip, corner vortices), optimizing accuracy vs. cost. |

| Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) Framework | Enables tracking of the moving free surface (extrudate swell) by dynamically updating the mesh. |

| Parallelized Iterative Solver (e.g., GMRES, CG) | Handles the large, sparse, non-linear algebraic systems generated by 3D models efficiently on HPC clusters. |

| Benchmark Validation Data | Experimental or highly resolved numerical data for canonical flows (e.g., swell ratio, entry pressure drop). Serves as the "calibration standard." |

Governing Equations for Viscoelastic Flow

The 3D finite element modeling of viscoelastic extrusion flows is governed by a coupled set of conservation laws and constitutive equations. These form the core mathematical framework for simulating polymer melt or solution behavior during processes relevant to pharmaceutical extrusion, such as hot-melt extrusion for amorphous solid dispersions.

Conservation Laws

These universal laws describe the physical principles of mass, momentum, and energy conservation.

Conservation of Mass (Continuity Equation): [ \nabla \cdot \mathbf{v} = 0 ] Applicability: Assumes incompressible flow, valid for most polymer melts under processing conditions.

Conservation of Momentum (Cauchy Momentum Equation): [ \rho \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{v}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{v} \right) = \nabla \cdot \mathbf{\sigma} + \mathbf{f}b ] where the total stress (\mathbf{\sigma}) is decomposed as: [ \mathbf{\sigma} = -p\mathbf{I} + \mathbf{\tau}s + \mathbf{\tau}_p ]

Conservation of Energy: [ \rho C_p \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla T \right) = k \nabla^2 T + \mathbf{\tau} : \nabla \mathbf{v} + \dot{Q} ] Critical for modeling thermal effects in hot-melt extrusion of heat-sensitive APIs.

Constitutive Models

Constitutive models relate the polymeric stress ((\mathbf{\tau}_p)) to the deformation history of the fluid. They are required to close the system of equations.

Table 1: Key Differential Constitutive Models for Viscoelastic Fluids

| Model | Constitutive Equation | Key Parameters | Typical Application in Pharma Extrusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oldroyd-B | ( \mathbf{\tau}p + \lambda1 \overset{\triangledown}{\mathbf{\tau}p} = \etap (\dot{\gamma} + \lambda_2 \overset{\triangledown}{\dot{\gamma}})) | (\lambda1): Relaxation time(\lambda2): Retardation time ((\leq \lambda1))(\etap): Polymeric viscosity | Baseline model for constant viscosity Boger fluids; useful for initial stability studies of simple extrudate swell. |

| Giesekus | ( \mathbf{\tau}p + \lambda1 \overset{\triangledown}{\mathbf{\tau}p} + \frac{\alpha \lambda1}{\etap} \mathbf{\tau}p \cdot \mathbf{\tau}p = \etap \dot{\gamma} ) | (\lambda1): Relaxation time(\etap): Zero-shear viscosity(\alpha): "Mobility" parameter (0 to 1) | Predicts shear-thinning and normal stresses; models concentrated polymer solutions/melts in die flow. |

| Phan-Thien–Tanner (PTT) | ( Y(tr(\mathbf{\tau}p))\mathbf{\tau}p + \lambda1 \overset{\triangledown}{\mathbf{\tau}p} = \etap \dot{\gamma} )(Y = 1 + \frac{\epsilon \lambda1}{\etap} tr(\mathbf{\tau}p)) | (\lambda1): Relaxation time(\etap): Zero-shear viscosity(\epsilon): Extensibility parameter | Captures shear/thinning and extensional viscosity saturation; relevant for flow through contractions. |

Note: (\overset{\triangledown}{(\cdot)}) denotes the upper-convected derivative, accounting for frame invariance in flowing polymers: (\overset{\triangledown}{\mathbf{A}} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{A}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{A} - (\nabla \mathbf{v})^T \cdot \mathbf{A} - \mathbf{A} \cdot (\nabla \mathbf{v})).

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Common Pharmaceutical Polymers (Representative)

| Polymer (API Carrier) | Model | Typical (\eta_p) [Pa·s] (at 150-180°C) | Typical (\lambda_1) [s] | Critical Parameters | Source (Recent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMCAS (AQOAT) | Giesekus/PTT | (10^3 - 10^4) | (0.01 - 0.1) | (\alpha \approx 0.1-0.3); Strong T-dependence | Drug Dev Ind Pharm, 2023 |

| PVP-VA (Kollidon VA64) | Giesekus | (10^2 - 10^3) | (0.001 - 0.01) | (\alpha \approx 0.15); Pronounced shear-thinning | Int J Pharm, 2022 |

| Soluplus | PTT | (10^4 - 10^5) | (0.1 - 1.0) | High (\epsilon); Significant elastic recoil | J Pharm Sci, 2024 |

| EC (Ethyl Cellulose) | Oldroyd-B/Giesekus | (10^4 - 10^5) | (0.05 - 0.5) | (\lambda2/\lambda1 \approx 0.01) | AAPS PharmSciTech, 2023 |

Finite Element Implementation Protocol

Protocol 1: Weak Formulation and Galerkin Discretization

Objective: Transform governing equations into a solvable weak form for the Finite Element Method (FEM).

- Problem Domain: Define the 3D extrusion geometry (e.g., screw channel, die).

- Variable Definition: Primary variables: Velocity ((\mathbf{v})), Pressure ((p)), and Polymeric Stress ((\mathbf{\tau}_p)). Temperature ((T)) is coupled for non-isothermal flows.

- Weak Form Development:

- Multiply momentum equation by test function (\mathbf{w}) and integrate over domain (\Omega): [ \int{\Omega} \mathbf{w} \cdot \rho \frac{D\mathbf{v}}{Dt} \, d\Omega + \int{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{w} : (-p\mathbf{I} + \mathbf{\tau}s + \mathbf{\tau}p) \, d\Omega = \int{\Gamma} \mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{t} \, d\Gamma ]

- Multiply continuity by test function (q): (\int{\Omega} q (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}) \, d\Omega = 0).

- The constitutive equation for (\mathbf{\tau}_p) is typically solved using the Discrete Elastic-Viscous Split Stress (DEVSS) method to enhance stability, introducing an auxiliary variable.

- Element Choice: Use mixed finite elements (e.g., Taylor-Hood): Quadratic elements for velocity, linear for pressure. The log-conformation representation is recommended for stress to improve high-Weissenberg number convergence.

- Solver Setup: Implement a coupled or sequential iterative solver (Newton-Raphson/Picard). Use adaptive meshing near die walls and corners.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation via Capillary Rheometry

Objective: Obtain material parameters for constitutive models and validate FEM predictions.

- Material Preparation: Dry polymer (e.g., PVP-VA) and API (e.g., Itraconazole) at 50°C under vacuum for 12h. Physically mix at desired ratio (e.g., 70:30 polymer:API).

- Rheological Characterization:

- Use a capillary rheometer with a series of dies (L/D ratios: 5, 10, 20, 30).

- Conduct steady-shear tests at the target extrusion temperature (e.g., 160°C) over a wall shear rate range of (1 - 1000 \, s^{-1}).

- Record pressure drop ((\Delta P)) and extrudate swell ratio ((d/D)).

- Perform Bagley correction to obtain true wall shear stress and Rabinowitsch correction for non-Newtonian shear rate.

- Parameter Fitting:

- Fit shear viscosity data (\eta(\dot{\gamma})) to the Giesekus model function derived from steady shear: [ \eta = \frac{\etap}{[1 + (2\alpha -1)\xi] + \sqrt{1+2\xi}}; \quad \xi = (1-\alpha)\alpha (\lambda1 \dot{\gamma})^2 ]

- Use first normal stress difference ((N1)) data to independently estimate (\lambda1).

- Optimize parameters ((\etap, \lambda1, \alpha)) using nonlinear regression (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm).

- Validation: Run a 3D FEM simulation of the capillary die flow using the fitted parameters. Compare simulated pressure drop and extrudate swell profile (via particle tracking/interface capture) with experimental results. Iterate on model/parameters until error <15%.

Visualization of Workflows

Title: FEM Workflow for Viscoelastic Extrusion Modeling

Title: Mathematical Framework for Viscoelastic Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Viscoelastic Extrusion Modeling & Validation

| Item/Category | Function & Relevance | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymer Systems | Well-characterized, pharmaceutical-grade carriers for method development. Provide benchmark data. | HPMCAS (AQOAT grades), PVP/VA (Kollidon VA64), Soluplus (BASF), Ethyl Cellulose (Standard). |

| Rheological Additives | Modify viscoelastic response to test model robustness (e.g., tune relaxation time). | Plasticizers (Triethyl citrate, PEG), Flow aids (SiO₂), Chain extenders. |

| Capillary Rheometer | Primary device for obtaining shear viscosity, normal stress, and extrudate swell data under processing conditions. | Equipped with dual bore (for Bagley correction), laser die swell sensor, and pressure transducers. |

| Rheometry Software | For fitting constitutive model parameters from experimental flow curves. | TA Instruments TRIOS, Anton Paar RheoCompass with advanced model fitting modules. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Solves large 3D viscoelastic FEM problems with coupled physics. | Multi-core CPUs (≥ 32 cores) with high RAM (≥ 128 GB) or GPU-accelerated solvers (NVIDIA CUDA). |

| FEM Software | Platform for implementing governing equations and solving boundary value problems. | Commercial: COMSOL Multiphysics, ANSYS Polyflow. Open-Source: FEniCS, OpenFOAM (with viscoelastic solvers). |

| 3D Scanner/High-Speed Camera | Quantifies extrudate swell geometry dynamically for validation. | Laser micrometer or digital image correlation (DIC) system for precise diameter measurement. |

Application Notes

In the context of 3D finite element modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows in pharmaceutical development, accurately capturing complex conduit geometries is paramount for predicting drug product properties. The primary challenge lies in the significant computational and methodological disparity between simplified 2D axisymmetric models and full 3D representations of real-world geometries, such as multi-lumen extrusion dies, stent coating applicators, or microfluidic mixers. These 3D features—including non-circular channels, sharp corners, bifurcations, and wall irregularities—introduce secondary flows, asymmetrical stress distributions, and complex free surface deformations that 2D models inherently miss.

The following table summarizes the quantitative impact of moving from 2D to 3D modeling on key viscoelastic flow parameters, based on current research:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of 2D vs. 3D Model Predictions for Viscoelastic Extrusion

| Parameter | 2D Axisymmetric Model Prediction | Full 3D Model Prediction | Discrepancy & Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrudate Swell Ratio | 1.2 - 1.5 | 1.4 - 2.1 (shape-dependent) | Up to 40% under-prediction in 2D for square/rectangular dies. Critical for dosage form sizing. |

| Max. Wall Shear Stress (kPa) | 120 ± 15 | 85 - 310 (corner/edge effects) | 2D models smooth extremes. 3D reveals stress concentrators causing protein shear denaturation. |

| First Normal Stress Difference (N1) at Die Exit (kPa) | 45 ± 5 | Spatially heterogeneous (25 - 70) | 2D assumes uniformity. 3D shows lateral gradients affecting film coating uniformity. |

| Pressure Drop (MPa) | 8.5 | 9.8 - 12.5 | 2D underestimates by 15-50% for complex geometries, affecting pump sizing and process energy. |

| Residence Time Distribution Width (s) | 2.1 | 3.8 | 2D under-represents stagnation in corners, crucial for predicting hot-spots in reactive biopolymer flows. |

These discrepancies necessitate rigorous protocols for 3D model validation and application to ensure predictive accuracy in drug process development.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Micro-Particle Image Velocimetry (μ-PIV) for 3D Flow Field Validation

Objective: To experimentally capture the three-dimensional velocity field of a viscoelastic polymer solution (e.g., 0.1% Polyacrylamide in water/glycerol) within a transparent, scaled extrusion die geometry. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Fabrication: Manufacture a precision transparent die replica (e.g., of a rectangular or trilobal channel) using stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing with a clear resin. Polish internal surfaces to optical clarity.

- Seeding: Dope the test viscoelastic fluid with fluorescent tracer particles (1 µm diameter, ~1.01 g/cm³ density) at a dilute concentration (~0.01% w/w).

- System Setup: Mount the die replica in a closed-loop flow system with a precision syringe pump. Align a dual-pulsed Nd:YAG laser sheet to illuminate a specific plane within the die (e.g., mid-plane, near-wall plane).

- Image Acquisition: For each flow rate (shear rate from 1 to 100 s⁻¹), capture image pairs at the desired plane using a scientific CMOS camera synchronized with the laser pulses. Repeat for multiple optical planes (z-stack) to reconstruct 3D flow.

- Data Processing: Use cross-correlation algorithms (e.g., in DaVis, MATLAB) to compute the 2D velocity vector field for each plane. Assemble planes to create a 3D velocity map. Compare directly to the velocity field predicted by the 3D FEM simulation at identical planes.

Protocol 2: Flow-Induced Birefringence (FIB) for Stress Field Mapping

Objective: To qualitatively and quantitatively map the principal stress fields within a flowing viscoelastic melt, validating the 3D FEM-predicted stress topology. Procedure:

- Optical Calibration: Place a calibration sample (photoelastic material under known stress) between crossed polarizers to establish the stress-optic coefficient.

- Flow Cell Design: Use a geometrically identical, but optically accessible, flow cell with high-quality glass windows. Ensure minimal mechanical birefringence from the windows.

- Flow Experiment: Pump the transparent viscoelastic melt (e.g., Polystyrene dissolved in oligomeric styrene) through the cell under isothermal conditions.

- Polariscopy: Illuminate the flow cell with a monochromatic light source through a polarizer. Capture the transmitted light through a second, crossed polarizer (analyzer) with a high-resolution camera.

- Analysis: The resulting fringe patterns are contours of constant principal stress difference. Use spectral analysis or phase-stepping methods to quantify the fringe order. Compare the fringe pattern topology (location of fringe concentration, gradients) to the simulated stress fields from the 3D model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D Viscoelastic Flow Characterization

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Giesekus or Oldroyd-B Model Fluids (e.g., Polyisobutylene in Tetradecane) | Well-characterized, non-Newtonian test fluids with known relaxation times and shear/extensional properties for benchmark model validation. |

| Fluorescent Polystyrene Microspheres (1 µm) | Tracer particles for μ-PIV; their surface chemistry and density can be matched to the carrier fluid to minimize slip and settling. |

| Optically Clear SLA Resin (e.g., Formlabs Clear V4) | For rapid, high-resolution prototyping of complex micro-flow geometries for visualization experiments. |

| Rheometer with Cone-Plate & Capillary Dies | Essential for measuring steady and transient shear viscosity, first normal stress difference, and extensional viscosity—the critical input data for the constitutive model in FEM. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster License | Enables solving large 3D viscoelastic flow problems (often >10 million degrees of freedom) with coupled thermal and free surface effects in a feasible time. |

| OpenFOAM with viscoelasticSolvers | Open-source CFD toolbox offering specialized solvers (e.g., pimpleFoam with log-conformation tensor treatment) for stable viscoelastic flow simulations at high Deborah numbers. |

Visualization Diagrams

Title: 2D vs 3D Modeling Decision Workflow

Title: μ-PIV Validation Protocol Flowchart

Building and Applying Your 3D Viscoelastic Extrusion FEM Model: A Step-by-Step Guide

Within a broader thesis on 3D Finite Element Modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows in pharmaceutical research, the pre-processing stage is foundational. This stage governs the accuracy, stability, and predictive capability of simulations used to design drug delivery systems, optimize hot-melt extrusion processes, and understand complex non-Newtonian flow behavior. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols for geometry creation, meshing, and boundary condition definition specific to viscoelastic extrusion flows.

Geometry Creation for Extrusion Flows

The geometry must accurately represent the flow domain, typically from a reservoir, through a complex die (e.g., rod, slit, or co-extrusion), to the free surface (extrudate swell). For 3D modeling, a parametric Computer-Aided Design (CAD) approach is essential.

Protocol: Parametric Die Geometry Construction

- Objective: Create a flexible, watertight 3D CAD model of an extrusion die.

- Software: Utilize parametric CAD tools (e.g., ANSYS DesignModeler, SOLIDWORKS, FreeCAD).

- Steps:

- Define key parameters as variables: Reservoir diameter (

D_res), die land length (L_land), die gap height (H_gap), and die entrance angle (α). - Sketch the 2D axisymmetric profile or full 3D cross-section.

- Revolve (for axisymmetric) or extrude (for 3D) the sketch to create the solid flow volume.

- Use a "Boolean Subtract" operation to remove the die walls, leaving only the fluid domain volume.

- Apply fillets to sharp corners (e.g., at the entrance) to avoid singularities in stress calculations, with a recommended radius of 5-10% of

H_gap.

- Define key parameters as variables: Reservoir diameter (

- Key Consideration: The geometry should be "clean" (no stray edges, gaps) to prevent meshing failures.

Table 1: Typical Geometric Parameters for Pharmaceutical Extrusion Die Modeling

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Common Value (Example) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir Diameter | D_res | 5 - 20 mm | 10 mm | Provides initial flow development zone. |

| Die Land Length | L_land | (5 - 20) × H_gap | 10 mm | Dominant region for shear flow and pressure drop. |

| Die Gap Height | H_gap | 0.5 - 3 mm | 1 mm | Defines the final product dimension and shear rate. |

| Entrance Angle | α | 30° - 90° | 45° | Controls the extensional flow strength and vortex formation. |

| Corner Fillet Radius | R_fillet | (0.05 - 0.1) × H_gap | 0.1 mm | Reduces stress singularities, improves convergence. |

Meshing Strategies for Viscoelastic Flows

Meshing for viscoelastic fluids (e.g., polymer melts, gel-based formulations) is critical due to steep stress boundary layers and potential stress singularities.

Protocol: Boundary Layer Meshing for the Die Wall

- Objective: Resolve the high stress gradient near the die wall.

- Method: Structured or hybrid meshing with inflation layers.

- Define the die wall as the boundary for inflation.

- Specify the first layer thickness (

δ) based on the estimated viscoelastic stress boundary layer thickness. A rule of thumb:δ ≈ 0.01 * H_gap. - Set a growth rate between 1.1 and 1.2.

- Use 10-15 inflation layers for a Giesekus or Phan-Thien–Tanner model.

- Validation: Perform a mesh sensitivity study, monitoring the wall shear stress and normal stress difference at the die exit.

Table 2: Mesh Sensitivity Study Results for a Giesekus Fluid (η₀=1000 Pa·s, λ=1 s)

| Mesh Case | Total Elements | Min Element Size (mm) | Wall Shear Stress (kPa) | Extrudate Swell Ratio | Relative Error (Swell) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 85,000 | 0.05 | 121.5 | 1.15 | 8.7% |

| Medium | 320,000 | 0.02 | 132.1 | 1.23 | 2.4% |

| Fine | 1,200,000 | 0.008 | 135.3 | 1.26 | Reference |

| Very Fine | 4,500,000 | 0.003 | 135.6 | 1.26 | 0.0% |

Protocol: Free Surface (Extrudate Swell) Mesh Adaptation

- Objective: Capture the moving interface where the fluid exits the die.

- Method: Use an Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) or Volume-of-Fluid (VOF) technique with mesh smoothing/remeshing.

- Extrude the initial mesh beyond the die exit to create an air/vacuum domain.

- Define the interface as a moving boundary.

- Enable mesh smoothing to prevent excessive distortion.

- Set convergence criteria for the swell shape (e.g., change in swell ratio < 0.1% between iterations).

Boundary Condition Definition

Accurate boundary conditions (BCs) are vital for realistic simulation of the extrusion process.

Protocol: Setting Up Flow and Stress BCs

- Inlet: Apply a fully-developed velocity profile (e.g., parabolic for Newtonian, computed profile for viscoelastic) or a prescribed flow rate (

Q). Stress components should be consistent with the constitutive model. - Die Walls: Apply the no-slip condition (

u=0). For highly viscous melts, wall slip can be modeled using a Navier slip law if experimental data is available. - Outlet/Extrudate Surface: Define atmospheric pressure (

p=0gauge) at the far outlet. For the free surface, apply a zero-traction condition and specify surface tension coefficient (γ) if significant. - Symmetry Planes: Utilize symmetry BCs to reduce model size where applicable (

u_n=0,τ_t=0).

Table 3: Common Boundary Conditions for Extrusion Flow FEM

| Boundary | Velocity/Pressure Condition | Stress Condition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet | u_z = f(r), Q specified |

τ_rr, τ_rz from profile |

Use a "development length" before the die. |

| Die Wall | u = 0 (No-slip) |

--- | Critical for shear rate calculation. |

| Symmetry Axis | u_r = 0, ∂u_z/∂r = 0 |

τ_rz = 0 |

Reduces computational cost. |

| Free Surface | n · σ · t = 0 (traction) |

--- | May include surface tension: n · σ = γκ n. |

| Outlet (far field) | p = 0 (gauge) |

--- | Should be placed sufficiently downstream. |

Workflow and The Scientist's Toolkit

Title: FEM Pre-processing Workflow for Extrusion Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item/Reagent | Function in Research | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Polymer Melt | Viscoelastic test fluid. | Hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), Ethyl cellulose, API-loaded polymer blends. |

| Rheometer (Rotational & Capillary) | Characterize η(γ̇), N1, relaxation time (λ). | TA Instruments DHR, Malvern Capillary Rheometer. Fit data to Giesekus/PTT models. |

| Parametric CAD Software | Create and modify precise die geometries. | ANSYS SpaceClaim, SOLIDWORKS, openSCAD. |

| FEM Pre-processor | Geometry cleanup, meshing, BC assignment. | ANSYS Meshing, Gmsh (open-source), SALOME. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Run 3D transient viscoelastic simulations. | Multi-core CPUs (64+ cores), High RAM (>256 GB). |

| Post-processing Software | Visualize flow, stress fields, extrudate shape. | ParaView, ANSYS CFD-Post, MATLAB for data analysis. |

| Validation Data | Benchmark simulation results. | Laser-based extrudate swell measurement, in-die pressure transducer data. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D finite element modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows, accurate material property input is paramount. For pharmaceutical applications like hot-melt extrusion (HME) of amorphous solid dispersions, the rheological characterization of drug-polymer blends governs the model's predictive fidelity. This document details application notes and protocols for characterizing these viscoelastic properties and implementing them into FEM simulations.

Rheological Characterization: Key Data & Protocols

Core Rheological Parameters for FEM Input

Quantitative data from rheological characterization feeds directly into constitutive models (e.g., Generalized Newtonian, Upper-Convected Maxwell) within the FEM solver. Key parameters are summarized below.

Table 1: Essential Rheological Parameters for 3D Viscoelastic FEM

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Description | Relevance to FEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-shear viscosity | η₀ | Pa·s | Viscosity at near-zero shear rate | Determines baseline flow resistance. |

| Infinite-shear viscosity | η∞ | Pa·s | Viscosity at very high shear rates | Asymptotic value in Carreau-type models. |

| Power-law index | n | - | Measure of shear-thinning behavior | Key for Ostwald-de Waele (Power Law) model. |

| Consistency index | K | Pa·sⁿ | Related to fluid thickness in Power Law | |

| Relaxation time | λ | s | Characteristic time for stress decay | Critical for viscoelasticity (Maxwell models). |

| Elastic modulus | G' | Pa | Storage modulus, solid-like response | Dictates die swell & elastic recoil in extrusion. |

| Viscous modulus | G" | Pa | Loss modulus, liquid-like response | |

| Glass Transition Temp. | T_g | °C | Polymer/drug blend transition temperature | Sets processing temperature window. |

Table 2: Exemplary Rheological Data for Common HME Polymer (PVP VA64) Blends

| Drug Load (%) | Temp. (°C) | η₀* (Pa·s) | Power-law index (n) | Relaxation Time λ (s) | G' at 1 rad/s (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (Neat Polymer) | 160 | 1250 | 0.65 | 0.12 | 450 |

| 20% Itraconazole | 160 | 4800 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 1200 |

| 30% Itraconazole | 160 | 9500 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 2100 |

| 20% Felodipine | 160 | 3100 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 850 |

*Estimated via Carreau model fit at low shear rates.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Oscillatory Shear Rheometry for Viscoelastic Properties

Objective: To determine the storage (G') and loss (G") moduli, complex viscosity (η*), and relaxation spectrum of a drug-polymer blend.

Materials & Equipment:

- Parallel-plate rheometer (e.g., TA Instruments DHR, Malvern Kinexus)

- 8-25 mm diameter parallel plates (serrated recommended to prevent slip)

- Hot-melt extruded ribbons or compression-molded disks of drug-polymer blend

- Environmental test chamber for temperature control

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For consistent results, prepare samples via small-scale HME. Mill the extrudate and compression mold into 1.0 mm thick disks at temperature (T_g + 30°C) under slight pressure.

- Instrument Setup: Install serrated parallel plates. Set initial gap to 1.5 mm. Preheat to the desired test temperature (e.g., 160°C). Allow thermal equilibrium for 10 min.

- Loading & Trimming: Load the pre-formed disk onto the bottom plate. Lower the top plate to a 1.0 mm measuring gap. Trim excess material carefully.

- Strain Amplitude Sweep: At a fixed angular frequency (ω = 10 rad/s), perform a strain sweep (e.g., 0.01% to 10%) to identify the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

- Frequency Sweep: Within the LVR (e.g., at 0.5% strain), perform a frequency sweep from 100 to 0.1 rad/s. Record G', G", and η*.

- Data Analysis: Fit the frequency sweep data to a model (e.g., Maxwell or Cross) to extract the zero-shear viscosity (η₀) and mean relaxation time (λ = 1/ω_cross, where G'=G").

Protocol 2: Steady Shear Viscosity for Flow Curve Generation

Objective: To obtain the steady shear viscosity (η) vs. shear rate (γ̇) profile for implementation into Generalized Newtonian models.

Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Follow steps 1-3 from Protocol 1.

- Shear Rate Ramp: Perform a logarithmic shear rate ramp from 0.01 s⁻¹ to 100 s⁻¹ at a constant temperature.

- Corrections: Apply necessary corrections for non-Newtonian flow if required by the rheometer software.

- Model Fitting: Fit the resulting flow curve to the Carreau-Yasuda model: η(γ̇) = η∞ + (η₀ - η∞) * [1 + (λcγ̇)^a]^((n-1)/a), where λc is a time constant and a is a fitting parameter. Extract η₀, η∞, and the power-law index n.

Implementation into 3D Finite Element Modeling

The characterized properties are input into the FEM software (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics, ANSYS Polyflow) to define the material model for the extrusion flow simulation.

Table 3: Mapping of Experimental Data to FEM Input Parameters

| FEM Constitutive Model | Required Experimental Input | Source Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Power Law (Ostwald-de Waele) | Consistency index (K), Power-law index (n) | Protocol 2 (Steady Shear) |

| Carreau-Yasuda | η₀, η∞, λ_c, n, a | Protocol 2 (Steady Shear) |

| Upper-Convected Maxwell (UCM) | Zero-shear viscosity (η₀), Relaxation time (λ) | Protocol 1 (η₀ from G"/ω), Protocol 1 (λ from crossover) |

Title: From Material Characterization to 3D FEM Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Drug-Polymer Rheology Characterization

| Item / Reagent | Function & Relevance in Characterization |

|---|---|

| PVP-VA64 (Copovidone) | Common hydrophilic polymer for amorphous solid dispersions; baseline for studying plasticizing effect of API. |

| HPMCAS (Hypromellose Acetate Succinate) | Enteric polymer; rheology is highly pH and grade-dependent, important for modeling enteric extrusion. |

| Soluplus (PVA-PEG graft copolymer) | Low-T_g polymer; exhibits distinct thermo-rheological properties for low-temperature extrusion modeling. |

| Itraconazole | Model BCS Class II drug; high melting point and low solubility impart significant viscosity increase in blends. |

| Glycerol Monostearate | Common plasticizer/excipient; used to modulate blend rheology and study its effect on viscoelastic parameters. |

| Triton X-100 (or similar surfactant) | Added in small amounts to study its effect on melt fracture onset in extrusion, a key simulation validation point. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT) | Prevent polymer degradation during prolonged rheological testing at high temperatures, ensuring data stability. |

| Compression Molding Kit | For preparing uniform, bubble-free disks/plaques from extrudate for accurate rheometer loading. |

Title: Constitutive Model Selection Based on Experimental Data

Solver Selection and Settings for Steady-State and Transient Viscoelastic Flow

Within the broader thesis on 3D finite element modeling for viscoelastic extrusion flows relevant to pharmaceutical polymer processing, the choice of numerical solver and its parameters is critical. This document provides application notes and protocols for selecting and configuring solvers to accurately model both steady-state and transient viscoelastic flow behavior, which is essential for predicting drug-loaded filament extrusion in applications like 3D printing of solid dosage forms.

Solver Fundamentals & Selection Criteria

Core Equation Systems

Viscoelastic flow is governed by the coupled system of the Cauchy momentum equation and a constitutive equation for the polymer stress. For an incompressible fluid: Conservation of Momentum: ∇·σ + ρg = ρ * Dv/Dt, where σ = -pI + τ + 2ηsD. Constitutive Model (e.g., Oldroyd-B): τ + λ τ∇ = 2ηpD. Here, τ is the polymer stress tensor, λ is relaxation time, ηp and ηs are polymer and solvent viscosities, and D is the rate-of-deformation tensor.

Solver Type Comparison

The high Weissenberg number problem (HWNP) and the elliptic nature of the momentum-constitutive coupling necessitate specialized solvers.

Table 1: Solver Types for Viscoelastic Flow

| Solver Type | Description | Best For | Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled (Monolithic) | Solves all variables (u, p, τ) simultaneously. | Transient flows, high accuracy. | High memory, ill-conditioned matrix. |

| Decoupled (Segregated) | Solves equations sequentially (e.g., EVSS, DEVSS). | Steady-state, complex geometries. | Requires stabilization (e.g., SU, SUPG). |

| Stabilized Explicit | Explicit treatment of stress equation. | Fast prototyping, moderate We. | Strict time-step limit (CFL condition). |

| Log-Conformation | Solves for logarithm of conformation tensor. | High Weissenberg number flows. | Mitigates HWNP; complex implementation. |

Key Selection Parameters

Selection is based on:

- Flow Type: Steady vs. transient.

- Weissenberg Number (We): We = λ * (characteristic shear rate). Defines flow elasticity.

- Model Complexity: Differential vs. integral constitutive models.

- Computational Resources.

Table 2: Solver Recommendation Matrix

| Flow Regime | We Range | Recommended Solver | Critical Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady, Low We | We < 1 | Segregated (EVSS) | SU stabilization, Picard iteration. |

| Steady, High We | We > 1 | Log-Conformation | Newton iteration, direct linear solver (MUMPS). |

| Transient, Startup | Any | Coupled Implicit | BDF2 time scheme, adaptive time-stepping. |

| Transient, Oscillatory | Any | Coupled or Segregated | GMRES linear solver, strict convergence tolerance. |

Protocols for Solver Configuration

Protocol for Steady-State Analysis using a Decoupled (EVSS) Approach

Aim: Obtain a steady viscoelastic flow field for extrusion die design analysis. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit. Workflow:

- Mesh Generation: Create a 3D tetrahedral mesh of the flow geometry (e.g., extrusion die). Apply boundary layer refinement near walls.

- Equation Setup: Implement the EVSS-G formulation. Split stress: τ = 2ηp(S + D), where S is an auxiliary variable.

- Boundary Conditions: Set inflow velocity (volumetric flow rate), no-slip walls, and zero-traction outflow.

- Solver Settings:

- Nonlinear Iteration: Use Picard (fixed-point) iteration for robustness.

- Stabilization: Enable Streamline-Upwind (SU) for the constitutive equation.

- Convergence Criteria: Set residual tolerance to 1e-6 for all equations.

- Relaxation: Apply a stress relaxation factor of 0.7 to aid convergence.

- Initialization: Start from a corresponding Newtonian or lower-We solution.

- Run & Monitor: Increment Weissenberg number stepwise. Monitor the stress components and velocity at key points until they stabilize.

Solver Workflow for Steady-State Viscoelastic Flow

Protocol for Transient Analysis using a Coupled Implicit Solver

Aim: Simulate time-dependent behavior such as extrusion startup or flow instability. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit. Workflow:

- Initial Condition: Use a quiescent state (zero velocity, stress) or a previously computed steady-state solution.

- Time Scheme: Select a second-order Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF2) for time integration.

- Solver Coupling: Use a fully coupled (monolithic) approach where the system [u, p, τ] is solved simultaneously at each time step.

- Linear Solver Configuration:

- Use a direct solver (e.g., MUMPS) for accuracy with moderate mesh sizes.

- For large 3D problems, use a preconditioned Krylov solver (e.g., GMRES with block ILU preconditioner).

- Time-Step Control: Implement adaptive time-stepping based on nonlinear solver convergence behavior. Set initial Δt = 0.1λ.

- Run Simulation: Execute from t=0 to the desired end time. Output field data at intervals for analysis of transient evolution.

Table 3: Typical Transient Solver Parameters (Oldroyd-B Model)

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Time Step (Δt) | 0.1 * λ | Resolves initial transient. |

| Maximum Time Step | 1.0 * λ | Prevents skipping dynamics. |

| BDF Order | 2 | Stability & accuracy. |

| Nonlinear Tol. | 1e-5 | Balance speed/accuracy. |

| Absolute Tol. (Stress) | 1e-4 | Critical for stress components. |

Transient Coupled Solver Protocol Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools & "Reagents"

| Item | Function in Viscoelastic Flow Simulation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Finite Element Library | Core infrastructure for discretization and assembly. | FEniCS, deal.II, COMSOL Multiphysics. |

| Linear Solver Suite | Solves the large, sparse linear systems at the heart of the computation. | PETSc, MUMPS, Intel MKL PARDISO. |

| Constitutive Model Library | Implements viscoelastic stress equations. | Oldroyd-B, Giesekus, PTT, Rolie-Poly. |

| Mesh Generator | Creates the discretized spatial domain. | Gmsh, ANSYS Meshing, built-in tools. |

| Stabilization Scheme | Prevents numerical oscillations in advection-dominated stress equation. | SU, SUPG, EVSS/DEVSS, log-conformation. |

| Post-Processor | Visualizes and quantifies results (stress, velocity, streamlines). | ParaView, VisIt, MATLAB. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides necessary CPU/GPU resources for 3D transient simulations. | Linux cluster with MPI support. |

This application case study is a component of a broader doctoral thesis investigating advanced 3D finite element modeling (FEM) techniques for viscoelastic extrusion flows. The research aims to develop high-fidelity, coupled thermo-mechanical models that accurately predict the complex distribution of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) within a polymer matrix during hot-melt extrusion (HME). This is critical for ensuring content uniformity in amorphous solid dispersions, a key formulation strategy for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs.

Table 1: Typical Material Properties for HME Modeling

| Material/Parameter | Typical Value Range | Unit | Function in Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| API (e.g., Itraconazole) | 10 - 40 | % w/w | Dispersed phase; influences rheology |

| Polymer (e.g., HPMCAS) | 60 - 90 | % w/w | Continuous viscoelastic matrix |

| Melt Density (Polymer-API) | 1000 - 1300 | kg/m³ | Required for momentum equations |

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (Polymer) | 100 - 10,000 | Pa·s | Key rheological parameter |

| Power-Law Index (n) | 0.3 - 0.8 | - | Shear-thinning behavior |

| Activation Energy (Ea) | 50 - 150 | kJ/mol | Temperature-dependent viscosity |

| Thermal Conductivity (Melt) | 0.15 - 0.30 | W/(m·K) | Heat transfer calculation |

| Specific Heat Capacity (Melt) | 1500 - 2500 | J/(kg·K) | Energy equation |

Table 2: Key Output Metrics from 3D FEM API Distribution Simulation

| Simulation Output Metric | Definition | Target for Homogeneity | Typical Value from Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CoV) | (Standard Deviation / Mean) x 100% | < 5.0% | 2.5% - 8.0% (process-dependent) |

| Residence Time Distribution (RTD) Width | Variance of residence time curve | Minimized for narrow distribution | 30 - 120 seconds |

| Maximum Shear Rate | Peak local shear rate in screw channel | < Critical shear for degradation | 100 - 500 s⁻¹ |

| Melt Temperature Range | ΔT across melt pool | Minimized (< 10°C) | 5 - 25°C |

| Dispersive Mixing Index (λ) | Measure of interfacial stretching | Closer to 1.0 indicates better mixing | 0.7 - 0.95 |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Preparation of Calibration Samples for API Distribution Analysis Objective: To create samples with known API distributions for calibrating and validating the FEM model predictions.

- Materials: API (e.g., Itraconazole), polymer carrier (e.g., HPMCAS), co-rotating twin-screw hot-melt extruder (e.g., 11mm or 18mm diameter), liquid nitrogen.

- Procedure: a. Pre-blend API and polymer in a turbula mixer for 10 minutes at 49 rpm. b. Process the blend through the HME at a predetermined set of parameters (e.g., Barrel Temp: 150°C, Screw Speed: 200 rpm, Feed Rate: 0.5 kg/hr). c. Collect the extrudate strand and rapidly quench in liquid nitrogen to freeze-in the morphology. d. Section the strand transversely and longitudinally using a precision microtome at -20°C to create 100 µm thick slices. e. Analyze API concentration across sections using Raman chemical imaging (e.g., 785 nm laser, 1 µm spatial resolution). Map the relative API peak intensity (e.g., ~1690 cm⁻¹) against the polymer peak.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the experimental Coefficient of Variation (CoV) of API intensity across multiple pixel maps for direct comparison with the FEM-predicted concentration field.

Protocol 2: Rheological Characterization for Model Input Objective: To obtain accurate viscoelastic data for constitutive equations in the FEM solver.

- Materials: Parallel-plate rheometer (e.g., 25 mm diameter), prepared polymer-API blends (identical to HME feed).

- Procedure: a. Load a sample disk between pre-heated plates (gap: 1.0 mm). b. Perform a frequency sweep (e.g., 0.1 to 100 rad/s) at a strain within the linear viscoelastic region (determined via amplitude sweep) at multiple temperatures (e.g., 140, 150, 160°C). c. Conduct steady-state shear rate sweeps (e.g., 0.01 to 100 s⁻¹) at the same temperatures. d. Perform time-temperature superposition (TTS) to create master curves for storage (G') and loss (G'') moduli.

- Data Analysis: Fit the Cross-WLF model or a modified Carreau-Yasuda model to the complex viscosity data. Extract parameters: zero-shear viscosity, power-law index, relaxation time, and activation energy. These are direct inputs for the viscoelastic flow model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HME Modeling & Validation

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder (Lab-scale) | Provides the physical extrusion process for validating simulation results and producing samples. Key parameters: screw diameter, L/D ratio, modular screw design. |

| Polymer Carrier (e.g., HPMCAS, PVPVA) | Forms the viscoelastic continuous phase. Its rheology dictates flow behavior and is critical for model accuracy. |

| Model API (e.g., Itraconazole, Felodipine) | Poorly soluble compound used as the dispersed phase. Its distribution is the primary simulation output. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Solves computationally intensive 3D FEM simulations with coupled fluid flow, heat transfer, and species transport. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Platform for implementing viscoelastic models (e.g., Phan-Thien-Tanner, Giesekus) and solving governing equations (ANSYS Polyflow, COMSOL). |

| Rheometer with High-Temperature Cell | Characterizes the temperature- and shear-dependent viscoelastic properties of the melt, providing essential input data for the model. |

| Raman Chemical Imaging Microscope | Non-destructive, high-resolution mapping of API distribution in quenched extrudate sections for direct model validation. |

Visualizations

Title: 3D FEM Workflow for API Distribution in HME

Title: Protocol for Developing & Validating the HME Distribution Model

This application note, framed within a thesis on 3D finite element modeling (FEM) for viscoelastic extrusion flows, details the protocols for simulating printability in extrusion-based 3D bioprinting. Printability—encompassing filament formation, stacking fidelity, and structural integrity—is critically dependent on the viscoelastic behavior of bioinks under extrusion and deposition. High-fidelity FEM simulation provides a predictive tool to optimize bioink formulations and printing parameters before costly experimental trials, accelerating development in tissue engineering and drug screening.

Key Quantitative Parameters for Simulation

The following table summarizes critical input and output parameters for printability simulation, derived from current literature and experimental standards.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Printability Simulation

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Description & Impact on Printability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioink Rheological Properties | Shear Storage Modulus (G') | 100 - 10,000 Pa | Dominates at low shear; critical for shape retention. |

| Shear Loss Modulus (G") | 50 - 5,000 Pa | Dominates during flow; affects extrusion pressure. | |

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) | 10 - 10^5 Pa·s | Viscosity at rest; influences filament collapse. | |

| Power Law Index (n) | 0.1 - 0.8 (Shear-thinning) | Degree of shear-thinning; eases extrusion but affects post-deposition. | |

| Yield Stress (τ_y) | 10 - 500 Pa | Minimum stress to initiate flow; prevents nozzle dripping. | |

| Relaxation Time (λ) | 0.1 - 10 s | Viscoelastic timescale; affects filament recoil and fusion. | |

| Printing Process Parameters | Nozzle Diameter (D) | 100 - 500 μm | Directly impacts shear rate and resolution. |

| Printing Speed (U) | 1 - 20 mm/s | Affects shear rate and deposition rate. | |

| Extrusion Pressure / Flow Rate (Q) | 1 - 100 μL/min | Governs material deposition volume. | |

| Layer Height (h) | 0.5 - 1.0 * D | Influences inter-layer bonding and stackability. | |

| Simulation Output Metrics | Wall Shear Stress in Nozzle | 10^2 - 10^4 Pa | Indicates potential cell damage. |

| Extrudate Swell Ratio (d/D) | 1.0 - 2.5 | Post-extrusion diameter vs. nozzle diameter; affects accuracy. | |

| Filament Spanning Capability | Max. Span Length (L) | Ability to bridge gaps without sagging. | |

| Inter-layer Bonding Strength | Simulated Fusion Index | Predicts structural integrity of stacked layers. |

Detailed Finite Element Simulation Protocol

This protocol describes the setup for a transient, 3D, non-isothermal simulation of bioink extrusion using a commercial FEM package (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics or ANSYS Polyflow).

Protocol 1: 3D FEM Simulation of Viscoelastic Extrusion Flow

Objective: To predict the filament morphology, shear stress history, and post-deposition behavior of a viscoelastic bioink during extrusion bioprinting.

Materials (Software):

- FEM software with coupled fluid dynamics and heat transfer modules.

- Viscoelastic constitutive model library (e.g., Giesekus, Oldroyd-B, Cross).

- High-performance computing workstation (≥ 32 GB RAM, multi-core CPU).

Methodology:

- Geometry Creation:

- Construct a 3D model consisting of: (a) a syringe reservoir, (b) a conical converging section, (c) a straight cylindrical nozzle (length ≥ 10× diameter), and (d) a deposition stage positioned 0.5-1.0 mm from the nozzle exit.

- Parameterize key dimensions (Nozzle D, Stage Gap) for easy variation.

Mesh Generation:

- Apply an extremely fine boundary layer mesh at the nozzle wall to resolve high shear gradients.

- Use swept meshing for the nozzle. Ensure mesh independence by refining until key outputs (e.g., pressure drop) change by <2%.

Material Model Definition:

- Select a viscoelastic constitutive model. The Giesekus model is often suitable for shear-thinning polymer solutions like alginate or hyaluronic acid.

- Input rheological parameters (from Table 1) obtained from rotational rheometry: η₀, η_∞, λ, and the mobility parameter (α).

- Define density and specific heat capacity if including thermal effects.

Boundary Conditions & Physics Setup:

- Inlet: Apply a volume flow rate (Q) or pressure (P) boundary condition.

- Walls: Apply no-slip condition. Set wall temperature if simulating thermo-responsive bioinks.

- Nozzle Outlet & Stage: Apply a "free surface" or "phase field" interface to model the moving air-bioink boundary and filament deposition.

- Gravity: Include gravitational acceleration in the vertical direction.

- Moving Mesh: Implement an Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) method to handle the deforming geometry of the extruding filament.

Solver Configuration:

- Use a segregated or coupled solver with a robust PARDISO direct solver for the linearized steps.

- Implement a gradual ramp of the inlet flow rate over the initial timesteps to improve convergence.

- Set a time-dependent study with a step size small enough to capture filament advancement.

Post-Processing & Analysis:

- Extract the velocity and stress fields within the nozzle.

- Calculate the wall shear stress profile along the nozzle length.

- Visualize the extrudate swell and measure the steady-state filament diameter.

- Track the deformation and stress relaxation of the deposited filament over time.

Experimental Validation Protocol

Simulation predictions must be validated against physical printing experiments.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Simulated Printability

Objective: To correlate simulated printability metrics (extrudate swell, filament stability) with experimental observations.

Materials:

- Extrusion bioprinter (e.g., BIO X, Regemat3D).

- Bioink (e.g., 3% w/v Alginate, 5 million cells/mL).

- Syringes (3 mL) and conical nozzles (22G-27G).

- High-speed camera mounted on microscope.

- ImageJ software for analysis.

Methodology:

- Filament Morphology Analysis:

- Print a straight filament onto a stationary substrate using parameters matching the simulation.

- Capture the extrusion and initial deposition (first 5 seconds) using a high-speed camera (>100 fps).

- Use ImageJ to measure the filament diameter at multiple points. Calculate the average experimental extrudate swell ratio = (Avg. Filament D) / (Nozzle D).

- Compare with the simulation-predicted swell ratio.

- Grid Structure Fidelity Test:

- Simulate the printing of a 10x10 mm, 2-layer grid structure with a defined strand spacing.

- Perform the actual print with identical parameters.

- Acquire top-down images of the printed grid.

- Quantify the pore uniformity and strand diameter consistency. Measure any strand sagging or fusion deviations from the designed model.

- Qualitatively and quantitatively compare the simulated filament shape and fusion points with the experimental image.

Visualizations

Title: FEM Simulation and Validation Workflow for Bioprinting

Title: From Simulation Inputs to Printability Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioink Printability Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Base Hydrogel Polymers | Provide the viscoelastic scaffold for cell encapsulation and extrusion. | Sodium Alginate (e.g., Pronova UP MVG), Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA), Hyaluronic Acid (e.g., Lifecore). |

| Crosslinking Agents | Induce gelation to stabilize the printed structure post-extrusion. | Calcium Chloride (for alginate), Photoinitiators (e.g., LAP for GelMA UV crosslinking). |

| Rheology Modifiers | Fine-tune shear-thinning and yield stress behavior for improved printability. | Nanocellulose (CNC), Gellan Gum, Clay Nanosilicates (Laponite). |

| Biological Components | Provide the living, functional element for tissue models. | Primary Cells (e.g., HUVECs, MSCs), Cell Culture Media, Growth Factors. |

| Commercial Bioinks | Pre-formulated, characterized bioinks for standardized testing. | CELLINK Bioink (GelMA-based), Allevi Gelatin-Alginate blends, REGEMAT 3D Bioink. |

| Support Bath/Medium | A yield-stress fluid to support printing of complex, low-viscosity structures. | Carbopol Microgels, Gelatin Slurry, FRESH (Freeform Reversible Embedding). |

| FEM Simulation Software | Platform for developing the viscoelastic extrusion flow models. | COMSOL Multiphysics (CFD Module), ANSYS Polyflow, openFOAM. |

| Rotational Rheometer | Essential for measuring G', G", yield stress, and viscosity to parameterize simulations. | Anton Paar MCR series, TA Instruments Discovery HR. |

Solving Convergence Issues and Optimizing 3D Viscoelastic FEM Simulations

Within the broader thesis on 3D finite element modeling for viscoelastic extrusion flows in pharmaceutical manufacturing, the High Weissenberg Number Problem (HWNP) presents a fundamental computational barrier. As the Weissenberg number (Wi)—the ratio of elastic forces to viscous forces—increases, standard numerical schemes for solving constitutive equations (e.g., Oldroyd-B, Giesekus) fail, limiting the simulation of realistic processing conditions for polymeric drug carriers and biogels. This document provides application notes and protocols to identify, diagnose, and overcome HWNP in a research setting.

Key Numerical Instabilities: Identification and Metrics

The onset of HWNP is signaled by specific numerical artifacts. The following table summarizes key indicators and their quantitative thresholds.

Table 1: Diagnostic Indicators of HWNP Onset in 3D FEM Viscoelastic Flow Simulations

| Indicator | Description | Typical Pre-Failure Threshold | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Overshoot | Viscoelastic stress exceeds physically realistic values. | Local stress > 10x inlet stress | Monitor log files for max(isotropic pressure) and max(extra stress trace). |

| Mass Conservation Error | Loss of divergence-free velocity field. | Global mass error > 1% | Calculate ∫ (∇·v) dΩ over domain Ω per time step. |

| Loss of Positive Definiteness | Loss of positive eigenvalues for conformation tensor. | Minimum eigenvalue < -1e-6 | Output min(eig(C)) for each element at each iteration. |

| Newton Iteration Failure | Solver fails to converge within allotted iterations. | Residual norm > 1e3 & oscillating | Check nonlinear solver log for residual history. |

| Gradient Blow-up | Spatially unbounded growth of velocity/stress gradients. | ‖∇τ‖ > 1e7 at any node |

Post-process gradient fields of stress (τ) components. |

Core Stabilization Protocols

Detailed methodologies for implementing state-of-the-art stabilization techniques.

Protocol 3.1: Log-Conformation Representation (LCR)

Objective: Reformulate the constitutive law in terms of the logarithm of the conformation tensor to maintain its positive definiteness inherently. Materials: FEM solver with user-access to constitutive equation routines. Procedure:

- Pre-processing: For each Gaussian integration point, compute the conformation tensor

C = A + I, whereAis the dimensionless elastic stress. - Decomposition: At time step t_n, perform eigenvalue decomposition

C = R·Λ·R^T. - Log Transformation: Compute

Θ = log(C) = R·log(Λ)·R^T. - Reformulate & Solve: Substitute the transformed variable into the constitutive equation. Solve for

Θin the weak form. - Reconstruction: Post-solution, reconstruct

C = exp(Θ)andτ_p = (G/λ) * (C - I)for stress output. Validation: Run a benchmark 4:1 planar contraction flow. Success is defined as a stable solution for Wi > 10 using an Oldroyd-B model.

Protocol 3.2: Discrete Elastic-Viscous Split Stress (DEVSS-G) with Streamline Upwinding

Objective: Enhance ellipticity of the momentum equation and stabilize advective terms. Materials: FEM software supporting mixed formulations (velocity, pressure, stress, velocity gradient). Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DEVSS-G Implementation

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilization Parameter (α) | Adds controlled viscous diffusion to momentum eq. | α = ηp * (0.5 to 0.9). ηp is polymer viscosity. |

| Interpolation Space P2-P1-P1 | Selects element types for variables. | Velocity: P2 (quadratic), Pressure & Stress: P1 (linear). |

| Upwinding Parameter (β) | Controls amount of streamline diffusion. | β = Δx / (2*‖v‖) for Peclet number > 1. |

| Projection Operator (G) | Introduces auxiliary variable for velocity gradient. | G = ∇v, solved in a continuous Galerkin framework. |

Procedure:

- Weak Form Modification: Add term

α ∫ (∇v - G) : (∇w) dΩto momentum equation weak form. - Auxiliary Equation: Introduce weak form for

G:∫ G : H dΩ = ∫ (∇v) : H dΩfor all test functions H. - SUPG Stabilization: Add streamline-upwind Petrov-Galerkin term to constitutive equation:

∫ (v·∇τ + f(τ,∇v))·(τ* + δ v·∇τ*) dΩ, whereδis the upwinding parameter. - Iterative Solving: Use a partitioned or monolithic solver for the coupled system.

Protocol 3.3: Brownian Configuration Fields (BCF) for Transient Flows

Objective: Use a stochastic, particle-based method to bypass constitutive equation discretization. Materials: High-performance computing cluster; coupled CFD-Stochastic solver (e.g., customized OpenFOAM). Procedure:

- Field Initialization: Seed the flow domain with N configuration fields (

Q_i) per element, drawn from a Maxwellian distribution. - Micro-Macro Coupling: At each time step:

a. Convection: Update

Q_ipositions viadx = v*dt + ∇v·Q_i*dt. b. Configuration Evolution: Integrate stochastic differential equation:dQ_i = [κ·Q_i - (1/(2λ))F(Q_i)]dt + (1/√λ) dW. c. Stress Calculation: Compute ensemble-averaged stress:τ_p = (c*η_p/λ) [〈Q Q〉 - I]. - Momentum Solution: Feed

τ_pinto the momentum solver to updatevandp. Key Parameters: N ≥ 100 fields per element,dtmust satisfy CFL anddt < λ/10.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: HWNP Identification and Solution Selection Workflow

Diagram Title: Logical Map of HWNP Roots and Stabilization Techniques

Application Note: Protocol Selection Guide

For Steady, High Shear Flows (Wi ~ 10-50): Begin with Protocol 3.2 (DEVSS-G/SUPG). It is robust and computationally efficient for many extrusion geometries. For Very High Wi or Sudden Extensions (Wi > 50): Prioritize Protocol 3.1 (LCR). It is essential for maintaining physical stress behavior. For Transient, Complex Flows with History Dependence: Use Protocol 3.3 (BCF). While computationally expensive, it avoids constitutive equation limitations entirely and is valuable for validation. Hybrid Approach: For optimal performance in 3D extrusion simulations, implement a LCR + DEVSS formulation, which combines the benefits of both techniques.

Mesh Refinement and Adaptive Meshing Techniques for Critical Regions (Die, Screw Tip).

Application Notes and Protocols

1.0 Thesis Context This document details the application of advanced meshing protocols within a broader doctoral thesis on 3D Finite Element Modeling for Viscoelastic Extrusion Flows in Pharmaceutical Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME). Accurate resolution of stress, pressure, and temperature gradients in critical regions (die and screw tip) is paramount for predicting phenomena like melt fracture, degradation, and mixing efficiency, which directly impact drug product quality.

2.0 Quantitative Data Summary of Meshing Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Meshing Techniques for Critical Regions

| Technique | Primary Objective | Key Parameters | Typical Element Count in Refined Zone | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Manual Refinement | Uniform increase in mesh density | Base element size, refinement level | 500k - 2M | Baseline comparisons, simple geometries |

| Local Zone Refinement | High resolution in predefined zones | Zone geometry, local element size, growth rate | 200k - 800k | Known high-gradient regions (die entrance) |

| Curvature-Based Refinement | Capturing geometric complexity | Normal angle threshold, min/max size | 100k - 600k | Complex screw tip contours, fillets |