Advanced 3D Printing of Polymer Nanocomposite Filaments: From Materials Design to Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive article explores the cutting-edge field of 3D printing with polymer nanocomposite filaments, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced 3D Printing of Polymer Nanocomposite Filaments: From Materials Design to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive article explores the cutting-edge field of 3D printing with polymer nanocomposite filaments, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It provides a foundational understanding of material systems, including polymers (PLA, PCL, PVA) and nanofillers (CNTs, graphene, nanoclay, bioactive nanoparticles). The article details methodological approaches for filament fabrication (twin-screw extrusion, solvent casting) and advanced printing techniques (FDM, DIW) for creating scaffolds, drug delivery systems, and medical devices. It addresses critical troubleshooting for printability, dispersion, and interfacial adhesion, while offering optimization strategies for mechanical, thermal, and biological performance. Finally, it presents validation protocols and comparative analyses of different nanocomposite systems, evaluating their efficacy against regulatory and clinical benchmarks for translational research.

Polymer Nanocomposite Fundamentals: Building Blocks for Advanced 3D Printing

Application Notes

Within a research thesis focused on developing advanced polymer nanocomposite filaments for 3D printing, the selection of the core polymer matrix is foundational. These matrices determine the baseline mechanical properties, degradation profile, biocompatibility, and printability of the final composite material. The integration of nanofillers (e.g., hydroxyapatite, graphene, drug nanoparticles) aims to enhance these properties, but their performance is intrinsically tied to the host polymer. This section details the characteristics, applications, and quantitative data for three principal matrices.

Table 1: Core Properties of Biomedical Polymer Matrices for 3D Printing

| Polymer | Full Name | Typical Melting Temp. (°C) | Glass Transition Temp. (°C) | Degradation Time (Approx.) | Key Biomedical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Poly(lactic acid) | 150 - 180 | 55 - 65 | 12 - 24 months | Bone fixation devices, tissue engineering scaffolds, drug delivery capsules. | Brittle, slow degradation rate, acidic degradation products. |

| PCL | Poly(ε-caprolactone) | 58 - 65 | (-60) - (-65) | 24 - 48 months | Long-term implantable devices, soft tissue engineering, controlled drug delivery. | Low mechanical strength, very slow degradation, hydrophobic. |

| PVA | Poly(vinyl alcohol) | 180 - 230 (decomp.) | 58 - 85 | Water soluble (hours-days) | Sacrificial supports (dissolvable), temporary wound dressings, drug-loaded hydrogels. | Water-soluble, low thermal stability, limited long-term stability in vivo. |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) | Amorphous | 45 - 55 | 1 - 6 months (tunable) | Most common: tunable drug delivery systems, absorbable sutures, porous scaffolds. | Cost, variable batch-to-batch consistency. |

| PLA-PCL | PLA-PCL Copolymer | Varies by ratio | Varies by ratio | Tunable (3-24 months) | Soft-to-rigid tissue engineering, grafts requiring toughness and flexibility. | Complex synthesis, potential for phase separation. |

Table 2: Representative 3D Printing Parameters for Neat Polymers (FDM)

| Polymer | Nozzle Temp. Range (°C) | Bed Temp. Range (°C) | Print Speed (mm/s) | Adhesion Consideration | Special Consideration in Composites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 190 - 220 | 50 - 65 | 40 - 80 | Often not required | Nanofillers increase melt viscosity; may require higher temp. |

| PCL | 70 - 100 | 25 - 40 | 20 - 60 | Essential (blue tape, glue) | Low processing temp. limits heat-sensitive nanofiller inclusion. |

| PVA | 190 - 220 | 45 - 60 | 30 - 50 | Essential (glue stick) | Used primarily as a support; humidity control is critical. |

| PLGA | 200 - 230 | 55 - 70 | 20 - 50 | Essential (glass + adhesive) | Requires precise humidity control and often organic solvent handling. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of PLA-Hydroxyapatite (HA) Nanocomposite Filament for Bone Scaffolds

Objective: To produce and characterize a PLA-based nanocomposite filament reinforced with 5% wt. nano-hydroxyapatite for FDM 3D printing of bone tissue engineering scaffolds.

Materials & Reagents:

- PLA pellets (e.g., Ingeo 4043D)

- Nano-hydroxyapatite powder (particle size < 200 nm)

- Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) or chloroform

- Magnetic stirrer/hotplate

- Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator

- Teflon sheet or glass trays

- Laboratory vacuum oven

- Twin-screw micro-compounder or a heated mixing unit

- Single-screw filament extruder with diameter feedback control.

Procedure:

- Solution Blending: Dissolve 95g of PLA pellets in 500mL of DCM with vigorous stirring at room temperature until fully dissolved.

- Nanofiller Dispersion: Separately, disperse 5g of nano-HA in 100mL of DCM using probe sonication (200 W, 10 min, pulse cycle 5s on/5s off) to create a homogeneous suspension.

- Combination: Slowly add the nano-HA suspension to the PLA solution under continuous high-speed stirring. Stir for 2 hours.

- Precipitation & Drying: Pour the mixture into a large volume of methanol (non-solvent) to precipitate the composite. Filter the precipitate and wash with fresh methanol. Dry the recovered solid in a vacuum oven at 40°C for 48 hours to remove all residual solvents.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the dried composite blend into a twin-screw micro-compounder. Process at 180-190°C for 5 minutes at 50 rpm to ensure homogeneous mixing.

- Filament Extrusion: Immediately feed the compounded material into a single-screw extruder set to 175-185°C. Use a puller system to produce a filament with a consistent diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm. Spool the filament in a dry container.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Degradation and Drug Release Study of PCL/Drug-Loaded Scaffolds

Objective: To evaluate the mass loss and cumulative drug release profile from 3D-printed PCL scaffolds loaded with a model drug (e.g., Rifampicin) over 12 weeks.

Materials & Reagents:

- 3D-printed PCL or PCL/drug nanocomposite scaffolds (e.g., 10mm diameter x 2mm thick disks).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Model drug (e.g., Rifampicin).

- Sodium azide (0.02% w/v in PBS).

- Shaking incubator or water bath.

- Analytical balance (0.01 mg precision).

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC system.

- Vacuum desiccator.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh each scaffold individually (initial dry mass, M₀). Sterilize via ethanol immersion and UV exposure.

- Immersion: Place each scaffold in a sealed vial containing 10 mL of PBS with 0.02% sodium azide (to prevent microbial growth). Incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation (50 rpm).

- Media Sampling & Analysis: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 days):

- Withdraw 1 mL of release medium and replace with fresh, pre-warmed PBS.

- Analyze the sample for drug concentration using a validated UV-Vis or HPLC method to calculate cumulative release.

- Mass Loss Measurement: At selected time points, remove triplicate scaffolds from the study. Rinse with deionized water, dry in a vacuum desiccator to constant mass (Mₜ). Calculate mass loss as:

[(M₀ - Mₜ) / M₀] * 100%. - Characterization: Perform SEM, DSC, or FTIR on the dried degraded scaffolds to assess morphological and chemical changes.

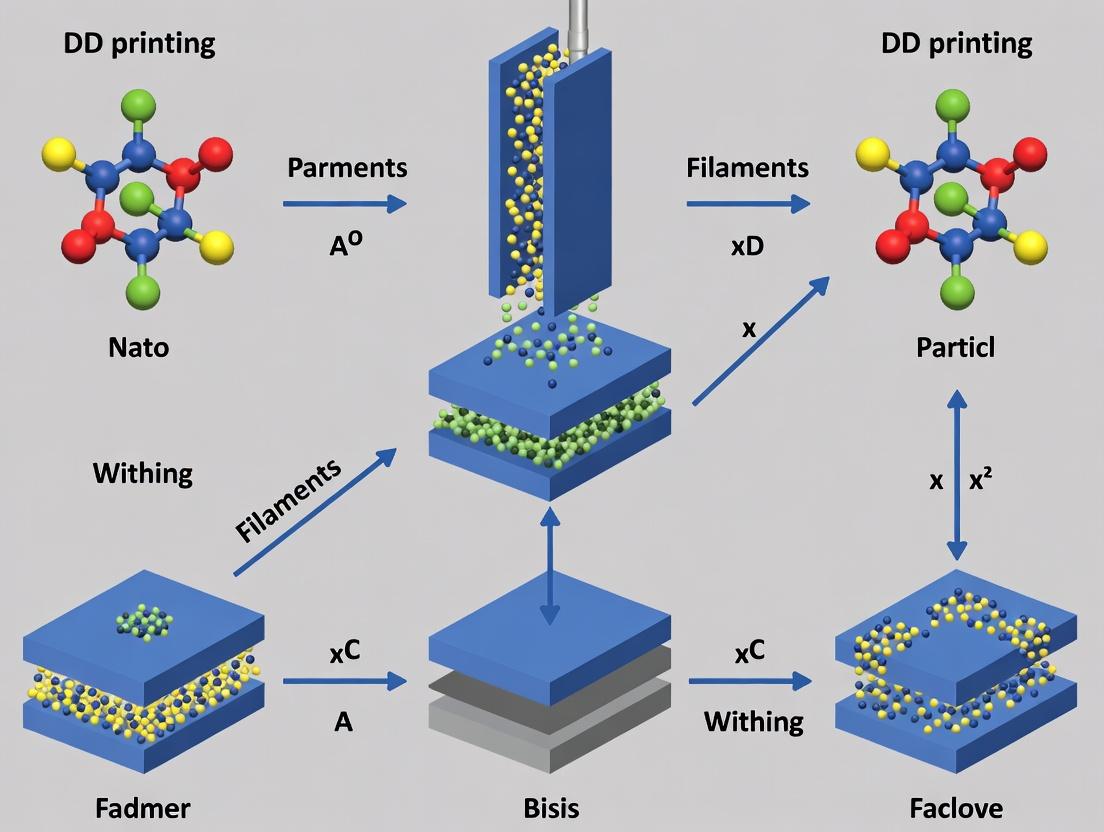

Diagrams

Title: Research Workflow for Nanocomposite Filaments

Title: Matrix Selection Drives Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| PLA (Ingeo 4043D/4032D) | Industry-standard, medical-grade resin with consistent rheology; baseline matrix for rigid, biodegradable constructs. |

| PCL (Capa 6500/6800) | Low-melt temperature, flexible polyester; ideal for blending and for in vitro cell studies requiring slow degradation. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, 87-89% hydrolyzed) | Water-soluble support material; critical for printing complex overhangs in multi-material designs with core composites. |

| PLGA (Resomer series) | Gold-standard copolymer for tunable drug delivery research; degradation rate adjusted via LA:GA ratio. |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite (<200nm) | Bioactive ceramic nanofiller; enhances stiffness, osteoconductivity, and protein adsorption of PLA/PCL matrices. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Common solvent for solution-based blending of polymers and nanofillers, especially for PLA and PLGA. |

| Twin-Screw Micro-Compounder (e.g., HAAKE MiniLab) | Essential for lab-scale, high-shear, homogeneous dispersion of nanofillers within molten polymer matrices. |

| Precision Single-Screw Filament Extruder | Produces consistent diameter (1.75mm/2.85mm) filament from compounded material for reliable FDM printing. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with Azide | Standard medium for in vitro degradation and drug release studies, preventing bacterial growth over long terms. |

Application Notes: Nanofillers for 3D Printed Polymer Nanocomposite Filaments

The integration of nanofillers into polymer matrices for fused deposition modeling (FDM) filament production represents a frontier in creating advanced functional materials. The selection and processing of nanofillers are critical for achieving desired mechanical, electrical, thermal, or bioactive properties without compromising printability.

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

Primary Application: Conductive composites, EMI shielding, structural reinforcement. Key Consideration: Dispersion is paramount. Agglomeration creates defects and acts as a failure point. Surface functionalization (e.g., carboxylation) improves compatibility with polar polymers like PLA or Nylon. High aspect ratio increases percolation threshold at low loadings (typically 0.5-5 wt%).

Graphene & Graphene Oxide (GO)

Primary Application: Electrical/thermal conductivity, barrier properties, mechanical strength. Key Consideration: GO offers better dispersion in aqueous and polymer phases due to oxygenated groups but is less conductive. Reduced GO (rGO) restores conductivity. Platelet morphology can significantly reduce gas permeability. Layer exfoliation and orientation during extrusion are crucial.

Nanoclays (e.g., Montmorillonite)

Primary Application: Flame retardancy, barrier improvement, mechanical stiffness, reduced warp. Key Consideration: Must be organically modified (e.g., with alkyl ammonium salts) for compatibility with hydrophobic polymers. Requires processing to achieve intercalation or exfoliation. Typically used at 1-8 wt%. Can increase melt viscosity significantly.

Bioactive Nanoparticles (e.g., Hydroxyapatite, Mesoporous Silica, Ag)

Primary Application: Drug delivery scaffolds, antimicrobial implants, bone tissue engineering. Key Consideration: Bioactivity must be preserved post-processing (extrusion & printing). Drug loading efficiency into nanoparticles before composite fabrication is key. Controlled release profiles can be tuned by polymer-nanoparticle matrix design. Sterility and cytotoxicity of final printed object are mandatory assessments.

Protocols

Protocol 1: Masterbatch Preparation and Filament Extrusion for CNT/Polymer Nanocomposites

Objective: To produce a uniform, agglomerate-free CNT/polylactic acid (PLA) filament for conductive 3D printing applications.

Materials:

- Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), carboxyl-functionalized

- PLA pellets (diameter ~3 mm)

- Dichloromethane (DCM) or Chloroform

- Sonicator (tip probe)

- Overhead mechanical stirrer

- Teflon-coated magnetic stir bars

- Fume hood

- Vacuum oven

- Twin-screw compounder (mini-lab scale) or single-screw extruder with mixing section

- Filament winding spool

- Laser micrometer

Procedure:

- Solution Mixing: Weigh 1.0 g of MWCNTs (targeting 2 wt% in final filament). Add to 500 mL of DCM in a 1000 mL glass beaker. Place beaker in an ice bath.

- Primary Dispersion: Using a tip sonicator, sonicate the mixture at 40% amplitude for 30 minutes (pulse cycle: 10 sec on, 5 sec off) to break primary agglomerates.

- Polymer Addition: Gradually add 49.0 g of PLA pellets to the stirring CNT suspension. Stir mechanically at 500 rpm for 2 hours until all polymer is dissolved.

- Precipitation & Drying: Slowly pour the viscous solution into 2 L of rapidly stirring methanol to precipitate the composite. Filter the precipitate using a Büchner funnel. Dry the wet cake in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 24 hours.

- Pelletization: Granulate the dried cake into small chips (~2-3 mm).

- Melt Compounding: Feed the chips into a twin-screw compounder. Use a temperature profile from 170°C to 190°C (hopper to die) and a screw speed of 100 rpm. Collect the extrudate, water-cool, and pelletize.

- Filament Extrusion: Feed the masterbatch pellets into a single-screw filament extruder. Use a precise temperature profile matching the polymer's melting point (e.g., 180-200°C for PLA). Adjust the haul-off speed to achieve a consistent filament diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm, monitored by a laser micrometer. Spool the filament under constant tension.

Protocol 2: In-situ Polymerization for Graphene Oxide/Nylon 6 Nanocomposite Filament

Objective: To achieve molecular-level dispersion of GO in Nylon 6 via caprolactam polymerization.

Materials:

- Graphene oxide (GO) aqueous dispersion (2 mg/mL)

- ε-Caprolactam monomer

- 6-Aminocaproic acid (initiator)

- Nitrogen gas cylinder

- Three-neck round-bottom flask

- Mechanical stirrer with heating mantle

- Vacuum distillation setup

- Strand die pelletizer

Procedure:

- Monomer-GO Mixing: In a three-neck flask, mix 500 g of ε-caprolactam with 250 mL of the GO dispersion (yields 0.1 wt% GO in final polymer). Begin stirring and heating to 90°C.

- Water Removal: Under a gentle stream of N₂, gradually raise the temperature to 140°C to distill off the water. Continue until the mixture becomes clear and viscous.

- Polymerization Initiation: Add 5.0 g of 6-aminocaproic acid. Increase temperature to 250°C under N₂ atmosphere. Maintain for 6 hours with constant stirring.

- Degassing & Processing: Apply vacuum for 1 hour to remove residual monomers and water. Pour the molten polymer composite onto a chilled metal plate.

- Pelletizing & Extrusion: Chip the cooled composite and dry at 80°C under vacuum for 12 hours. Extrude into filament using a standard Nylon 6 temperature profile (240-260°C).

Protocol 3: Assessment of Drug Release from Bioactive Nanoparticle-Loaded Filament

Objective: To quantify the release kinetics of a model drug (e.g., Vancomycin) from a 3D printed nanocomposite scaffold containing mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs).

Materials:

- 3D printed disc scaffold (e.g., 10 mm diameter x 2 mm height) from drug-loaded MSN/PLA filament

- Vancomycin hydrochloride

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Sodium azide

- Thermostated shaking water bath

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC system

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Dialysis bags (optional, for reservoir method)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh each 3D printed disc scaffold accurately (W₁). Sterilize under UV light for 30 minutes per side.

- Release Medium: Prepare PBS with 0.1% w/v sodium azide to prevent microbial growth.

- Incubation: Place each scaffold in a vial containing 10.0 mL of release medium. Seal the vials.

- Sampling: Place vials in a shaking water bath at 37°C, 60 rpm. At predetermined time points (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 168 hrs), remove 1.0 mL of the release medium and replace with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed PBS.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in the sample using a validated HPLC method (C18 column, UV detection at 280 nm) or a UV-Vis spectrophotometric assay.

- Data Processing: Calculate cumulative drug release as a percentage of the total drug loaded (determined via separate solvent extraction of the scaffold).

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Common Nanofillers in Polymer Matrices for FDM

| Nanofiller | Typical Loading (wt%) | Key Property Enhancement | Primary Challenge | Optimal Polymer Matrix Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNT | 0.5 - 5 | Electrical Conductivity (10⁻⁶ to 10¹ S/m), Tensile Strength (+20-100%) | Agglomeration, Viscosity Increase | PLA, ABS, Polycarbonate |

| Graphene | 0.5 - 8 | Thermal Conductivity (+50-300%), Tensile Modulus (+30-120%) | Restacking, Dispersion | Epoxy, PS, PP |

| Organoclay | 1 - 8 | Young's Modulus (+50-400%), O₂ Barrier (-40-80%) | Complete Exfoliation, Color | PA6, PP, PLA |

| n-Hydroxyapatite | 5 - 30 | Bioactivity, Compressive Modulus | Brittleness, Nozzle Clogging | PCL, PLGA, PEEK |

| Mesoporous SiO₂ | 1 - 10 | Drug Loading Capacity (up to 500 mg/g) | Aggregation, Weakening | PLA, PVA, PEG-PLA |

Table 2: Standard Characterization Suite for 3D Printed Nanocomposites

| Characterization | Technique | Target Information | Typical Result for Validated Composite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersion | TEM, SEM | State of nanofiller dispersion & distribution | Homogeneous distribution, no agglomerates >200 nm |

| Thermal | TGA, DSC | Degradation temp., Loading %, Crystallinity | Td increase >10°C; Tg/Tm shift |

| Mechanical | Tensile Tester (ASTM D638) | Young's Modulus, Tensile Strength, Elongation | Modulus/Strength increase >15% vs. neat polymer |

| Melt Flow | Melt Flow Indexer | Printability, Viscosity | MFI within 10-30% of neat polymer for reliable feeding |

| Functional | 4-point Probe, Impedance Analyzer | Electrical Conductivity, Dielectric Constant | Percolation threshold achieved; desired conductivity |

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Nanocomposite Filament Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Drug Release from 3D Printed Nanocomposite

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Nanocomposite Filament Development

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Surface-Modified Nanofillers | Carboxylated CNTs, Aminated Graphene, Quaternary Ammonium Clays. Provide functional groups for better polymer adhesion and dispersion, reducing agglomeration. |

| Compatibilizers | Maleic anhydride-grafted polymers (e.g., PE-g-MA, PP-g-MA). Act as molecular bridges between hydrophilic nanofillers and hydrophobic polymer matrices, improving interfacial strength. |

| High-Boiling Point Solvents | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), Dimethylformamide (DMF). Used in solution casting or in-situ polymerization for graphene/CNT composites due to excellent dispersion capability. |

| Thermal Stabilizers | Hindered phenol antioxidants (e.g., Irganox 1010). Critical for processing temperature-sensitive polymers (like PLA) with catalytic nanofillers (CNTs) to prevent degradation. |

| Plasticizers | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Citrate esters. Added in small amounts (1-5%) to bioactive composites to moderate melt viscosity and improve printability without sacrificing biofunctionality. |

| Sonication Probes (Tip) | For high-energy, direct cavitation in solutions to exfoliate graphene or break CNT bundles. Preferable over bath sonicators for masterbatch preparation. |

| Vacuum Drying Oven | Essential for removing residual solvents and moisture from nanocomposite pellets before extrusion. Moisture causes voids and poor filament quality. |

| Laser Micrometer | Non-contact measurement of filament diameter during spooling. Provides real-time feedback for process control to achieve the ±0.05 mm tolerance required by FDM printers. |

Application Notes

Within 3D printing of polymer nanocomposite filaments, the interfacial interaction between the polymer matrix and nanofiller (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, nanoclay, silica) is the critical determinant of final part performance. Strong interfacial adhesion facilitates effective stress transfer, leading to enhanced mechanical reinforcement, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity. Poorly designed interfaces result in agglomeration, defect sites, and print failure. For drug development, this interface can be engineered to control the loading and release kinetics of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from printed dosage forms.

Key Applications in 3D Printing & Drug Development:

- Mechanically Reinforced Implants & Devices: Strong covalent grafting of nanofillers to biopolymers (e.g., PCL, PLA) creates filaments for load-bearing bone scaffolds.

- Conductive Biosensor Traces: Percolation networks of graphene or CNTs in thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) enable printed, flexible electrode filaments.

- Tailored Drug Release Matrices: Nanoclay-polymer interfaces can act as diffusion barriers, modulating API release from printed tablets.

- Thermally Stable Fixturing: Strongly bonded silica nanoparticles in engineering plastics (e.g., Nylon) reduce warping and improve dimensional accuracy during printing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessment of Interfacial Adhesion via Rheological Percolation Threshold

- Objective: To determine the degree of nanoparticle dispersion and polymer-nanofiller interaction by measuring the critical filler content at which a solid-like network forms.

- Materials: Base polymer (e.g., PLA pellets), nanofiller (e.g., functionalized graphene nanoplatelets), twin-screw micro-compounder, rotational rheometer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare nanocomposites with 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and 5.0 wt% nanofiller via melt compounding.

- Under nitrogen purge, perform small-amplitude oscillatory shear tests on compression-molded discs.

- Measure the complex viscosity (η*) and storage modulus (G') as a function of frequency (0.1-100 rad/s) at the printing temperature.

- Plot the low-frequency (0.1 rad/s) G' versus filler concentration (wt%). The percolation threshold (φc) is identified by a sharp transition in slope.

- Interpretation: A lower φc indicates superior dispersion and stronger polymer-filler interactions, leading to more efficient reinforcement for filament extrusion.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Interfacial Strength via Modified Halpin-Tsai Model Fitting

- Objective: To derive an empirical parameter (χ) characterizing the interfacial strength by fitting tensile modulus data to a micromechanics model.

- Materials: 3D printed tensile bars (ASTM D638 Type V) from nanocomposite filaments, universal testing machine.

- Procedure:

- Print tensile bars at optimal orientation and 100% infill.

- Perform tensile tests (n=5) to obtain the experimental elastic modulus (E_comp).

- Apply the modified Halpin-Tsai equation for aligned fillers:

E_comp = E_matrix * [1 + ζηφ_filler] / [1 - ηφ_filler]whereη = [(E_filler/E_matrix) - 1] / [(E_filler/E_matrix) + ζ]. The parameterζ = 2 * (aspect ratio) * χ, where χ is the interfacial efficiency factor (0 ≤ χ ≤ 1). - Use known values for Ematrix, Efiller, aspect ratio, and φfiller. Iteratively adjust χ until the model prediction matches the experimental Ecomp.

- Interpretation: χ = 1 indicates perfect stress transfer (ideal interface). Values < 1 indicate interfacial slippage and inefficiency.

Protocol 3: Surface Energy Analysis for Predicting Filler Dispersion

- Objective: To determine the compatibility between polymer and nanofiller by measuring their surface energies.

- Materials: Neat polymer film, filler pellet or cake, contact angle goniometer, three test liquids (water, diiodomethane, formamide).

- Procedure:

- Measure the contact angle (θ) for each liquid on both the polymer and filler surfaces.

- Calculate the surface energy components (dispersion γ^d and polar γ^p) using the Owens-Wendt-Rabel-Kaelble (OWRK) method.

- Compute the Work of Adhesion (Wa) between polymer and filler:

W_a = 2 * [ sqrt(γ_polymer^d * γ_filler^d) + sqrt(γ_polymer^p * γ_filler^p) ]. - Calculate the interfacial energy (γinterface):

γ_interface = γ_polymer + γ_filler - W_a.

- Interpretation: A higher Wa and a lower γinterface predict spontaneous wetting and stable dispersion of the filler within the polymer matrix during compounding.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Interfacial Efficiency (χ) and Reinforcement in Common 3D Printing Nanocomposites

| Polymer Matrix | Nanofiller (1 wt%) | Functionalization | Percolation Threshold (φc, wt%) | Interfacial Efficiency (χ) | Tensile Modulus Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Graphene Oxide (GO) | None | ~2.5 | 0.4 | +22 |

| PLA | GO | APTES Silane | ~1.2 | 0.8 | +58 |

| TPU | Multi-Walled CNT | None | ~1.8 | 0.3 | +15 |

| TPU | Multi-Walled CNT | Acid Oxidation | ~0.9 | 0.7 | +45 |

| PCL | Nanoclay (MMT) | None | >5 | 0.2 | +8 |

| PCL | Nanoclay (MMT) | Chitosan Mod. | ~3.0 | 0.6 | +35 |

Table 2: Surface Energy Components and Work of Adhesion

| Material | γ^d (mJ/m²) | γ^p (mJ/m²) | Total γ (mJ/m²) | W_a with PLA (mJ/m²) | γ_interface with PLA (mJ/m²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (Matrix) | 38.2 | 6.8 | 45.0 | - | - |

| Pristine Graphene | ~40 | ~2 | ~42 | 84.1 | 2.9 |

| OH-Functionalized Graphene | 35.5 | 18.7 | 54.2 | 95.7 | 3.5 |

| APTES-Functionalized Silica | 23.1 | 32.9 | 56.0 | 98.2 | 2.8 |

Visualizations

Title: Workflow for 3D Printing Nanocomposite Research

Title: Stress Transfer Mechanisms at Polymer-Filler Interface

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Interface Engineering |

|---|---|

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | A coupling agent that forms covalent bonds between inorganic filler surfaces (e.g., SiO2, clay) and polymer matrices, dramatically improving χ. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI), Branched | A polymeric compatibilizer used to non-covalently functionalize carbon nanotubes/graphene, enhancing dispersion in polar polymers via charge interactions. |

| Pluronic F-127 Surfactant | A block copolymer surfactant used to stabilize nanoparticle dispersions in solvent-based pre-treatment methods prior to melt blending. |

| Dicumyl Peroxide (DICP) | A free-radical initiator used in reactive extrusion to graft maleic anhydride-functionalized polymers onto filler surfaces in situ. |

| 1,4-Phenylenediisocyanate (PPDI) | A bifunctional crosslinker used to create urethane linkages between hydroxyl-functionalized fillers and polymer end-groups. |

| Chitosan, Low Molecular Weight | A biopolymer used to modify nanoclay surfaces, improving biocompatibility and interfacial adhesion in bio-polyester (e.g., PCL, PLA) filaments. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing of polymer nanocomposite filaments, the targeted enhancement of mechanical strength, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity is paramount for advancing applications in custom laboratory equipment, biomedical devices, and controlled-release drug delivery systems. These property enhancements are achieved through the strategic incorporation of nanoscale fillers (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, nanoclay, ceramic nanoparticles) into thermoplastic matrices (e.g., PLA, ABS, PEEK). The resulting nanocomposite filaments enable the fabrication of structurally robust, heat-resistant, and functionally conductive components via fused filament fabrication (FFF).

Key Application Notes:

- Mechanical Strength: Enhanced tensile and flexural modulus is critical for load-bearing components in diagnostic devices and surgical guides. Nanoclay and carbon fiber reinforcements are prominent.

- Thermal Stability: Improved heat deflection temperature (HDT) and reduced coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) allow for autoclavable parts and components subjected to thermal cycling. Ceramic nanoparticles (Al2O3, SiO2) are effective.

- Electrical Conductivity: The introduction of conductive percolation networks enables applications in static dissipation, electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding, and embedded sensors for lab-on-a-chip devices. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene are primary fillers.

Summarized Quantitative Data from Recent Studies

Table 1: Comparative Enhancement of 3D Printed Polymer Nanocomposites

| Base Polymer | Nanofiller (wt%) | Key Enhancement | Measured Property | Result (vs. Neat Polymer) | Source/Ref (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Cellulose Nanocrystals (5%) | Mechanical Strength | Tensile Strength | +58% | Addit. Manuf. (2023) |

| Polyamide (PA12) | Carbon Nanotubes (3%) | Electrical Conductivity | Volume Conductivity | 10⁻¹ S/cm (from insulator) | Carbon (2024) |

| Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) | Graphene Nanoplatelets (8%) | Thermal Stability | Heat Deflection Temp | +22°C | Compos. Sci. Technol. (2023) |

| Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) | Nano Silica (10%) | Mechanical & Thermal | Flexural Modulus / HDT | +15% / +18°C | Mater. Des. (2024) |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Organoclay (4%) | Mechanical Strength | Young's Modulus | +120% | Polymers (2023) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of CNT/PLA Conductive Nanocomposite Filament

Aim: To produce a filament with enhanced electrical conductivity and mechanical strength for printable electrodes.

- Drying: Dry PLA pellets at 80°C for 6 hours. Dry multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) at 120°C for 2 hours.

- Masterbatch Preparation: Use a twin-screw micro-compounder. Pre-mix 15 wt% MWCNTs with PLA pellets via tumble blending. Feed mixture into the compounder at 190-210°C, 100 rpm for 5 min residence time to ensure dispersion.

- Dilution & Filament Extrusion: Dilute the masterbatch with virgin PLA to target 3 wt% CNT concentration via a second compounding step. Feed the compounded material into a single-screw filament extruder. Use a 1.75 mm die, precise temperature zones (200-210°C), and a laser micrometer for diameter feedback control. Spool the filament under constant tension.

- Post-processing: Anneal the spooled filament at 90°C for 2 hours in a vacuum oven to relieve internal stresses.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Thermal Stability via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Aim: To quantify the improvement in thermal decomposition temperature of a nanoclay/ABS composite.

- Sample Preparation: Print TGA sample pans (or obtain material) from 3D-printed nanoclay/ABS and neat ABS test specimens using identical printing parameters (220°C nozzle, 100% infill).

- Equipment Calibration: Calibrate the TGA (e.g., TA Instruments Q50) for temperature and weight using standard references.

- Experiment Setup: Load 5-10 mg of finely cut sample into a platinum pan. Set the method: equilibrate at 50°C, then heat from 50°C to 800°C at a rate of 20°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 60 mL/min).

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument software to determine the onset decomposition temperature (T₅%, temperature at 5% weight loss) and the temperature of maximum degradation rate (Tmax) from the derivative curve. Compare values between nanocomposite and neat polymer.

Protocol 3: Tensile Testing of 3D Printed Nanocomposite Specimens

Aim: To measure the enhancement in mechanical strength (Tensile Modulus & Strength) per ASTM D638.

- Specimen Printing: Design a Type I ASTM D638 dog-bone specimen in CAD. Slice with uniform parameters: 100% rectilinear infill, 0.2 mm layer height, 3 perimeter shells, and a raster angle of 0°/90°. Use consistent print speed and cooling fan settings for all specimens (neat polymer and nanocomposite).

- Conditioning: Condition all printed specimens at 23°C and 50% relative humidity for at least 48 hours before testing.

- Testing: Use a universal testing machine (e.g., Instron 5967) equipped with a 5 kN load cell and mechanical grips. Set the gauge length to 50 mm and the crosshead speed to 5 mm/min. Perform a minimum of 5 tests per material.

- Calculation: Calculate tensile modulus from the initial linear slope of the stress-strain curve. Record the ultimate tensile strength.

Diagrams and Workflows

Title: Nanocomposite Filament Fabrication Workflow

Title: Property-to-Application Relationship Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Polymer Nanocomposite Filament Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| Base Thermoplastics | The polymer matrix; determines printability, biocompatibility, and baseline properties. | PLA (NatureWorks), PEEK (Victrex), ABS (Styrolution) |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Imparts electrical conductivity and improves tensile strength. Require functionalization for dispersion. | MWCNTs, NC7000 (Nanocyl) |

| Graphene Nanoplatelets (GNPs) | Enhances thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, and barrier properties. | xGnP (XG Sciences) |

| Nanoclay | Significantly improves modulus, strength, and thermal stability (barrier effect). | Cloisite 30B (BYK) |

| Compatibilizer/Coupling Agent | Improves interfacial adhesion between filler and polymer matrix, critical for dispersion. | Maleic Anhydride-grafted polymer (e.g., PE-g-MA), Silanes |

| Twin-Screw Compounder | Provides high-shear mixing for distributive and dispersive nanofiller blending in the melt. | Micro-compounder (Xplore, DSM) |

| Filament Extruder | Produces consistent diameter (e.g., 1.75mm, 2.85mm) filament from compounded material. | Noztek Pro, 3devo Adventurer |

| Vacuum Drying Oven | Removes moisture from polymers and hygroscopic fillers prior to processing to prevent defects. | Binder VD series |

| Desktop 3D Printer (FFF) | For fabricating test specimens and prototypes using the developed filament. Requires hardened nozzle for abrasive composites. | Modified Prusa i3, Ultimaker S5 |

Application Notes: Targeted Drug Delivery & Antimicrobial Implants

Recent advances in nanocomposite filaments for 3D printing have pivoted towards creating multi-functional medical devices with precise therapeutic release profiles and inherent antimicrobial properties.

- Sustained-Release Drug-Eluting Implants: A significant breakthrough involves the use of polycaprolactone (PCL) blended with mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) loaded with anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., Ibuprofen). The high surface area of MSNs allows for a high drug payload, while the polymer-nanoparticle interface controls diffusion. 3D-printed bone scaffolds demonstrate sustained release over 28+ days, with drug release kinetics programmable by modifying MSN concentration (5-15 wt%) and print infill density (60-90%). This enables patient-specific, localized treatment for conditions like osteomyelitis or post-surgical inflammation.

- Active Antimicrobial Nanocomposites: To combat implant-associated infections, researchers have developed polylactic acid (PLA) filaments incorporating in-situ synthesized zinc oxide nanorods (ZnO NRs) and graphene oxide (GO) sheets. The ZnO NRs provide a sustained release of Zn²⁺ ions, disrupting bacterial membranes, while GO sheets offer photothermal antibacterial activity under near-infrared (NIR) light. 3D-printed meshes show a >99.9% reduction in S. aureus and E. coli viability within 24 hours of contact. Synergy is observed at 3 wt% ZnO and 0.5 wt% GO.

- Electrically Conductive Neural Guides: For nerve regeneration, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) filaments with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and piezoelectric barium titanate (BaTiO₃) nanoparticles have been co-printed. The MWCNTs (2-4 wt%) provide continuous conductive pathways (conductivity ~10⁻² S/cm), while the BaTiO₃ (5 wt%) generates localized electrical stimuli under mechanical deformation. In vitro studies with PC12 cells show a 40% increase in neurite outgrowth alignment and length on these nanocomposites compared to pure TPU controls.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Summary of Recent Nanocomposite Filament Systems (2023-2024)

| Application | Polymer Matrix | Nanofiller(s) | Key Performance Metric | Optimal Loading | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-Eluting Scaffold | Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Drug-Loaded Mesoporous Silica (MSNs) | Sustained Release Duration | 10 wt% MSNs | 2024 |

| Antimicrobial Mesh | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | ZnO Nanorods & Graphene Oxide (GO) | Bacterial Reduction (%) | 3 wt% ZnO, 0.5 wt% GO | 2023 |

| Neural Conduit | Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) | MWCNTs & BaTiO₃ | Electrical Conductivity (S/cm) | 3 wt% MWCNTs | 2024 |

| High-Strength Part | Nylon 6 | Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) | Tensile Strength Increase (%) | 5 wt% CNC | 2023 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Fabrication of Drug-Loaded PCL/MSN Nanocomposite Filament This protocol details the production of a uniform, drug-impregnated filament for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF).

- Nanoparticle Loading: Dissolve Ibuprofen (200 mg) in anhydrous ethanol (20 mL). Add 1g of MSNs (pore size: 5nm) and stir for 24h at room temperature in the dark. Centrifuge, wash with ethanol, and dry under vacuum to obtain drug-loaded MSNs (MSN-IBU).

- Melt Compounding: Dry PCL pellets and MSN-IBU at 50°C for 6h. Use a twin-screw micro-compounder at 90°C. Feed a physical premix of PCL with 10 wt% MSN-IBU. Employ a screw speed of 100 rpm for 5 min residence time to ensure homogeneity.

- Filament Extrusion: Directly extrude the compounded melt through a 1.75 mm die. Use a puller wheel system to spool the filament, maintaining diameter tolerance of ±0.05 mm. Store in a desiccator, protected from light.

Protocol 2.2: In-vitro Assessment of Antimicrobial Activity (ISO 22196 Modified) This protocol standardizes the testing of 3D-printed nanocomposite surfaces against bacterial cultures.

- Sample Preparation: 3D print 50mm x 50mm x 2mm plaques using standard FFF parameters. Sterilize under UV light for 30 minutes per side.

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow S. aureus (ATCC 6538) to mid-log phase in Tryptic Soy Broth. Centrifuge, wash, and resuspend in PBS to a concentration of 3.0 x 10⁵ CFU/mL.

- Contact Test: Apply 100 µL of inoculum onto the test sample. Carefully place a sterile, 40mm x 40mm polyethylene film overlay to spread inoculum without bubbles. Incubate at 35°C and >90% RH for 24h.

- Viable Count: Transfer the sample and film to 10 mL of SCDLP recovery medium. Sonicate in a water bath for 5 min, then vortex for 30s. Perform serial dilutions, plate on TSA, and count colonies after 24h incubation at 37°C. Calculate bacterial reduction relative to a pure polymer control.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Drug Release from MSN-PCL Nanocomposite

Diagram 2: Antibacterial Mechanism of ZnO/GO-PLA

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanocomposite Filament Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs), 5-10nm pore | High-surface-area carrier for drug molecules; pore size controls loading capacity and release kinetics. |

| Surface-Modified CNTs (COOH or OH functionalized) | Improves dispersion in polymer matrices; prevents agglomeration for consistent electrical/mechanical properties. |

| Pharmaceutical-Grade Therapeutic (e.g., Ibuprofen) | Model drug compound for proof-of-concept sustained-release studies in biocompatible scaffolds. |

| Twin-Screw Micro-Compounder (Haake/Minilab) | Enables precise, small-batch melt mixing of polymer and nanofillers with controlled shear and temperature. |

| Filament Diameter Gauge (Laser/Contact) | Critical for ensuring filament meets FFF printer specifications (typically 1.75 ± 0.05 mm). |

| ISO 22196:2011 Compliant Test Organisms (S. aureus, E. coli) | Standardized bacterial strains for quantitatively assessing antibacterial activity of 3D-printed surfaces. |

Fabrication to Function: Methods and Biomedical Applications of Printed Nanocomposites

Within the research for a thesis on 3D printing polymer nanocomposite filaments, the fabrication method critically dictates the final filament's properties, including nanoparticle dispersion, polymer crystallinity, and mechanical integrity. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three core fabrication techniques: Melt Blending, Solvent Casting, and In-Situ Polymerization. These protocols are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to produce specialized filaments for fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing, particularly for applications in drug delivery devices and functional prototypes.

Melt Blending (MB)

Application Notes

Melt blending is a solvent-free, industrially scalable process where polymer and nanofillers are mixed above the polymer's melting temperature using high shear forces. It is ideal for thermally stable polymers (e.g., PLA, ABS, PCL) and nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, metal oxides). Key advantages include rapid processing and absence of solvent residues. A primary challenge is achieving homogeneous nanoparticle dispersion without agglomeration.

Protocol: Twin-Screw Extrusion for Nanocomposite Filament

Objective: To produce a uniform PLA/graphene nanocomposite filament (1.75 mm diameter) with 2 wt% filler loading.

Materials & Equipment:

- PLA pellets (dried at 80°C for 4h)

- Graphene nanoplatelets

- Twin-screw extruder (co-rotating, L/D ratio 40:1)

- Filament winder

- Diameter measuring laser gauge

- Desiccator

Procedure:

- Pre-mixing: Manually pre-blend dried PLA pellets with graphene nanoplatelets in a sealed container for 10 minutes.

- Extrusion Parameters: Set extruder temperature profile from feed zone to die: 175°C, 180°C, 185°C, 190°C, 185°C. Screw speed: 150 rpm.

- Feeding: Use a gravimetric feeder to introduce the pre-mix into the extruder hopper at a constant rate.

- Extrusion & Pelletizing: The molten composite is extruded, water-cooled, and pelletized.

- Filament Extrusion: Feed pellets into a single-screw extruder equipped with a 1.75 mm diameter die. Use a puller and winder synchronized to maintain diameter tolerance (±0.05 mm). Monitor diameter in-line.

- Spooling & Storage: Spool the filament under constant tension and store in a desiccator.

Key Data from Recent Studies (Melt Blending)

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Melt-Blended Nanocomposite Filaments

| Polymer Matrix | Nanofiller (Loading) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Graphene (2 wt%) | 68.5 ± 3.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 2023 |

| ABS | CNT (1.5 wt%) | 45.2 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2024 |

| PCL | nHA (5 wt%) | 32.1 ± 1.8 | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 2023 |

Data sourced from recent peer-reviewed literature (2023-2024). CNT: Carbon Nanotubes; nHA: nanohydroxyapatite.

Solvent Casting (SC)

Application Notes

Solvent casting involves dissolving the polymer in a volatile solvent, dispersing the nanofiller into the solution, and then evaporating the solvent to form a film or, subsequently, a filament. This method excels at achieving exceptional nanoparticle dispersion at low filler loadings and is suitable for heat-sensitive polymers and bioactive compounds (e.g., proteins, drugs). The main drawbacks are solvent toxicity, removal residues, and difficulty in scaling.

Protocol: Solvent Casting and Pelletization for Drug-Loaded Filaments

Objective: To fabricate a PVA/gentamicin sulfate/montmorillonite nanocomposite filament for antimicrobial wound dressing scaffolds.

Materials & Equipment:

- PVA powder

- Gentamicin sulfate

- Montmorillonite (MMT) clay

- Deionized water (solvent)

- Magnetic stirrer with heating

- Ultrasonic bath & probe sonicator

- Glass casting plate

- Vacuum oven

- Bench-top pelletizer

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 10g PVA in 90mL DI water at 85°C with stirring for 2 hours until clear.

- Nanoparticle Dispersion: Disperse 3 wt% MMT (relative to PVA) and 5 wt% gentamicin in 10 mL DI water using probe sonication (200 W, 15 min, pulse mode).

- Mixing: Combine the MMT/drug suspension with the PVA solution under magnetic stirring (1 h). Subsequently, degas the solution in a vacuum desiccator for 30 min.

- Casting: Pour the solution onto a leveled glass plate using a doctor blade set to 1 mm thickness.

- Drying: Allow slow evaporation at room temperature for 24h, followed by drying in a vacuum oven at 40°C for 12h.

- Pelletizing: Cut the dried film into small pieces and feed into a bench-top pelletizer to create uniform granules for subsequent filament extrusion.

Key Data from Recent Studies (Solvent Casting)

Table 2: Properties of Solvent-Cast Nanocomposite Precursors for Filaments

| Polymer Matrix | Additive (Function) | Filler Loading | Key Outcome (Film State) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | Rifampicin (Drug) | 10 wt% | Sustained release over 28 days, >95% bioactivity retained. | 2024 |

| PLA | Cellulose NC (Reinf.) | 3 wt% | Transparent film; tensile strength increased by 120%. | 2023 |

| Chitosan | Ag NPs (Antimicrobial) | 0.5 wt% | Zone of inhibition: 12 mm against S. aureus. | 2024 |

In-Situ Polymerization (ISP)

Application Notes

In-situ polymerization involves dispersing nanofillers within a monomer or pre-polymer solution, followed by polymerization. This technique promotes strong interfacial adhesion between the polymer matrix and the filler, as nanoparticles can be chemically grafted or participate in the reaction. It is highly effective for creating nanocomposites with covalently bonded networks (e.g., epoxy/CNT, nylon-6/clay). Complexity and monomer handling are significant challenges.

Protocol: In-Situ Ring-Opening Polymerization for PA6/MWCNT Filament

Objective: To synthesize nylon-6 (PA6) multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) nanocomposite via in-situ polymerization and form it into filament.

Materials & Equipment:

- ε-Caprolactam monomer

- MWCNTs (COOH-functionalized)

- Sodium hydride (catalyst)

- N-Acetylcaprolactam (initiator)

- Three-neck reactor with N₂ inlet

- Mechanical stirrer

- Heating mantle

- Grinding mill

Procedure:

- Monomer Preparation: Melt 100g ε-caprolactam in the reactor under N₂ atmosphere at 80°C.

- Filler Dispersion: Add 1 wt% MWCNTs to the molten monomer. Use high-shear mechanical stirring (500 rpm) for 1 hour, followed by bath sonication for 30 min while maintaining temperature.

- Catalyst/Initiator Addition: Add 0.5 mol% sodium hydride (catalyst) and 0.3 mol% N-acetylcaprolactam (initiator) relative to monomer under constant stirring.

- Polymerization: Gradually raise temperature to 160°C and maintain for 4-6 hours under N₂ until viscosity increases significantly.

- Post-Processing: Crush the solidified product and wash with hot water to remove residual monomer. Dry and grind into powder.

- Compounding & Extrusion: The PA6/MWCNT powder must be melt-compounded in a twin-screw extruder (similar to Protocol 1.1) to ensure homogeneity before final filament extrusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanocomposite Filament Fabrication

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| PLA (Poly lactic acid) | Biodegradable, biocompatible polymer matrix for biomedical and prototyping filaments. | Ingeo 3D850, 4043D |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | Low melting point, flexible polymer ideal for drug delivery and tissue engineering scaffolds. | Capa 6500 |

| Functionalized Nanofillers | To improve interfacial adhesion and dispersion within the polymer matrix. | COOH-MWCNTs, APTES-modified SiO₂ |

| High-Boiling Point Solvent | For solvent casting with polymers requiring non-aqueous processing. | Dimethylformamide (DMF), Chloroform |

| Plasticizer | To modify filament flexibility and printability, especially for brittle polymers. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Tributyl citrate |

| Compatibilizer | To enhance miscibility between hydrophobic polymers and hydrophilic nanofillers. | Maleic anhydride-grafted polymers (e.g., PE-g-MA) |

| Thermal Stabilizer | To prevent polymer degradation during high-temperature melt processing. | Irganox 1010 |

| Monomer for ISP | Reactive precursor for in-situ synthesis of the polymer matrix around fillers. | ε-Caprolactam, Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA) |

Visualization of Technique Selection & Workflow

Diagram Title: Decision Flow for Filament Fabrication Technique

Diagram Title: Comparative Workflows for Three Filament Techniques

This document provides Application Notes and Protocols for optimizing the fused filament fabrication (FFF) of polymer nanocomposite filaments. The work is framed within a broader doctoral thesis investigating the structure-property-processing relationships in 3D-printed nanocomposites for advanced applications, including customized drug delivery devices and biomedical tooling. Achieving consistent, high-quality prints requires meticulous calibration of three interdependent parameters: Nozzle Temperature, Print Speed, and Bed Adhesion. This guide synthesizes current research to establish reproducible protocols for researchers and development professionals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix Filaments (e.g., PLA, ABS, PCL with 1-5% wt. nano-filler) | Base material. Nanofillers (CNTs, graphene, nanoclay) enhance mechanical, thermal, or electrical properties. PCL is common for biomedical applications due to biocompatibility. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (≥99%) | For degreasing print bed surfaces (glass, PEI) to remove oils and ensure uniform adhesive layer application. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) or Suitable Solvent | For preparing homogeneous nanoparticle dispersions in polymer solutions prior to filament extrusion (lab-scale production). |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Glue Stick or Hairspray | Provides a consistent, thin adhesive layer on build plates to improve first-layer adhesion for challenging materials. |

| 3D Print Bed Adhesive (Commercial) | Specialized adhesives (e.g., Magigoo, Layerneer) formulated for specific material groups to balance adhesion and part removal. |

| Brim or Raft Dissolution Solution | For water-soluble PVA support structures; often warm water with mild agitation. |

| Digital Calipers (0.01mm resolution) | For critical measurement of filament diameter, first layer height, and dimensional accuracy of printed test objects. |

| Thermal Camera (IR) or Pyrometer | For non-contact verification of actual nozzle and bed temperature profiles during printing. |

Core Parameter Optimization: Data & Protocols

Table 1: General Starting Parameter Ranges for Common Nanocomposites (FFF)

| Material (Nanocomposite) | Nozzle Temp. Range (°C) | Bed Temp. Range (°C) | Print Speed Range (mm/s) | Key Adhesion Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA + Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | 200 - 220 | 55 - 65 | 40 - 60 | Heated bed, clean glass |

| ABS + Graphene Nanoplatelets | 230 - 250 | 100 - 110 | 40 - 70 | Heated bed, ABS slurry/Kapton tape |

| PCL + Hydroxyapatite (Biomedical) | 70 - 90 | 25 - 40 (or cool) | 30 - 50 | PLA-coated glass, PVA glue |

| Nylon + Nanoclay | 240 - 260 | 80 - 90 | 30 - 50 | Heated bed, white glue (diluted) |

| PETG + CNTs/Graphene | 235 - 250 | 70 - 80 | 50 - 70 | Heated bed, clean PEI sheet |

Table 2: Effect of Parameter Variation on Print Quality

| Parameter | Increase Effect | Decrease Effect | Optimal Calibration Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Temperature | Reduced viscosity, better layer fusion, but may cause oozing, stringing, and thermal degradation of polymer/nanofiller. | Increased viscosity, poor layer adhesion, under-extrusion, higher nozzle pressure. | Lowest temperature that yields smooth extrusion and strong inter-layer bonding. |

| Print Speed | Faster build time, but may cause under-extrusion, layer skipping, and reduced adhesion due to shear. | Minimizes under-extrusion, improves adhesion, but increases build time and can cause heat creep. | Maximum speed without artifacts, adjusted relative to temperature and layer height. |

| Bed Adhesion | Excessive adhesion can damage part or build surface upon removal. | Warping, corner lifting, catastrophic print failure. | Uniform first layer squish with minimal force required for part removal after cooling. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nozzle Temperature Calibration Tower

Objective: To determine the optimal nozzle temperature for a given nanocomposite filament that balances flow characteristics and final part strength.

Materials: Target nanocomposite filament, calibrated FFF 3D printer, slicing software (e.g., Cura, PrusaSlicer).

Method:

- Design or download a temperature tower model with identifiable sections (e.g., 180°C to 230°C in 5°C increments).

- In your slicer, use the "Change at Z" or "Modifier" function to assign a different nozzle temperature to each section of the tower.

- Set all other parameters constant (Speed: 50 mm/s, Layer Height: 0.2 mm, Bed Temp: as per Table 1, 100% fan after first layer).

- Print the tower.

- Evaluation: Visually inspect for stringing between pillars (too hot) and layer adhesion/roughness (too cold). Perform a manual break test by trying to snap each section; the optimal temperature is where breaking is most difficult.

Protocol 2: Print Speed vs. Adhesion Test (First Layer & Warping)

Objective: To establish the maximum reliable print speed while maintaining excellent bed adhesion and minimizing warping.

Materials: Target nanocomposite filament, FFF printer, adhesive (as per Table 1), digital calipers.

Method:

- Apply the chosen bed adhesion method uniformly.

- Print a large, single-layer rectangle (e.g., 100mm x 100mm x 0.2mm) or a standard warping test shape (e.g., a 20mm tall cube with large brim).

- Iterative Test: Print the model multiple times, incrementally increasing the print speed (e.g., 30, 45, 60, 75 mm/s) while keeping nozzle and bed temperatures constant at your baseline.

- Evaluation: Use calipers to measure the actual first layer thickness across multiple points—it should match the set layer height. Visually inspect for gaps (under-extrusion) or ridges (over-extrusion). For the warping test, measure the gap between the part corner and the bed after complete cooling.

Protocol 3: Systematic Bed Adhesion Assessment

Objective: To empirically determine the best bed surface and preparation method for a new nanocomposite filament.

Materials: Nanocomposite filament, FFF printer, various bed surfaces (clean glass, PEI, blue tape), adhesion promoters (glue stick, hairspray, specialty adhesive).

Method:

- Prepare test surfaces: clean glass (IPA), PEI sheet, blue painter's tape. Apply different promoters to separate, labeled zones on one surface.

- Print a series of small, high-risk-for-warping objects (e.g., a 10mm single-wall cylinder) on each surface/zone.

- Use identical print parameters for all (Nozzle/Bed Temp from Table 1, Slow first layer speed: 20 mm/s).

- Allow the bed to cool fully.

- Evaluation: Qualitatively rank the effort required to remove the part (easy, moderate, difficult) and note any warp or damage to the part or bed surface. The optimal method allows secure adhesion during printing and easy removal after cooling.

Visualized Workflows & Relationships

Title: Workflow for Optimizing 3D Printing Parameters

Title: Interplay of Key Printing Parameters

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing of polymer nanocomposite filaments, this report details the frontier application of these advanced materials as biocompatible scaffolds. The research focuses on developing osteoconductive and osteoinductive constructs for bone and tissue engineering, leveraging the synergistic effects of nanocomposite matrices (e.g., PCL, PLA, GelMA) with bioactive reinforcements (e.g., nano-hydroxyapatite, graphene oxide, bioactive glass). This document provides application notes and detailed experimental protocols for key procedures.

Application Notes & Key Findings

Table 1: In Vitro and In Vivo Performance Metrics of Selected 3D-Printed Nanocomposite Scaffolds

| Polymer Matrix | Nanofiller (wt%) | Porosity (%) | Compressive Modulus (MPa) | Cell Viability (%, Day 7) | Key Osteogenic Marker (Fold Increase, vs Control) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | nHA (20%) | 68 ± 3 | 42.5 ± 5.1 | 95.2 ± 3.1 | ALP Activity: 2.8x | 2023 |

| PLA | Graphene Oxide (1%) | 72 ± 4 | 88.3 ± 7.2 | 97.5 ± 2.5 | Runx2 Expression: 3.2x | 2024 |

| GelMA-Hyaluronic Acid | Bioactive Glass (5%) | 85 ± 2 | 15.2 ± 1.8 | 98.1 ± 1.8 | OCN Secretion: 4.1x | 2024 |

| PCL-PEG | nHA (15%) + Sr ion | 65 ± 5 | 50.1 ± 4.3 | 96.8 ± 2.4 | Collagen I Deposition: 3.5x | 2023 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) of PCL/nHA Nanocomposite Scaffolds

Objective: To fabricate a 3D porous scaffold with osteoconductive properties. Materials: PCL/nHA (20% wt) nanocomposite filament (1.75 mm diameter), FDM 3D printer with heated bed, G-code slicer software. Procedure:

- Design & Slicing: Design a 10x10x3 mm³ scaffold with orthogonal pore geometry (strand distance: 400 µm, layer height: 200 µm) using CAD. Export as STL. Import into slicer. Set parameters: Nozzle Temp: 110°C, Bed Temp: 50°C, Print Speed: 15 mm/s, Filament Diameter: 1.75 mm.

- Printer Setup: Load the PCL/nHA filament. Level the build plate. Preheat nozzle and bed to set temperatures.

- Printing: Initiate print. Ensure first layer adhesion. Allow scaffold to cool on the bed after completion.

- Post-processing: Sterilize scaffolds by immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes, followed by UV irradiation (254 nm, 30 min per side).

Protocol 2:In VitroOsteogenic Differentiation Assay on Scaffolds

Objective: To evaluate the osteoinductive potential of printed scaffolds using human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Materials: Sterilized scaffolds, hMSCs (e.g., ATCC PCS-500-012), osteogenic media (α-MEM, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone), ALP staining kit, Alizarin Red S. Procedure:

- Seeding: Seed hMSCs onto scaffolds in 24-well plates at a density of 5x10⁴ cells/scaffold in growth media. Allow attachment for 4 hours, then add 1 mL of osteogenic or control media.

- Culture: Maintain at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Change media every 2-3 days for up to 21 days.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity (Day 7-10): Wash scaffolds with PBS, lyse cells with 0.1% Triton X-100. Assay lysate using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) substrate. Measure absorbance at 405 nm. Normalize to total protein content (BCA assay).

- Mineralization Assay (Day 21): Fix constructs with 4% PFA for 15 min. Stain with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2) for 20 min. Wash extensively. For quantification, de-stain with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and measure absorbance at 562 nm.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Scaffold Fabrication & Osteogenesis Assay Workflow

Diagram Title: Nanocomposite-Mediated Osteogenic Signaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanocomposite Scaffold Research

| Item Name / Solution | Supplier Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PCL / PLA Nanocomposite Filament (1.75 mm) | 3D4Makers, ColorFabb | Raw material for FDM printing; contains dispersed bioactive nanofillers (nHA, GO). |

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | Lonza, ATCC, Thermo Fisher | Primary cell model for evaluating scaffold biocompatibility and osteoinduction. |

| Osteogenic Differentiation Media Kit | MilliporeSigma, STEMCELL Tech. | Provides standardized supplements (dexamethasone, ascorbate, β-glycerophosphate) to induce osteogenesis. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Detection Kit (pNPP-based) | Abcam, Sigma-Aldrich | Quantifies early osteogenic differentiation via enzymatic activity in lysates. |

| Alizarin Red S Staining Solution | ScienCell, Sigma-Aldrich | Histochemical stain for detecting and quantifying calcium-rich mineral deposits. |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Calcein AM/EthD-1) | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | Fluorescence-based assay to simultaneously visualize live (green) and dead (red) cells on scaffolds. |

| RNeasy Mini Kit (for scaffolds) | Qiagen | Isolates high-quality total RNA from cells seeded on 3D scaffolds for qRT-PCR analysis. |

| Type I Collagen Antibody (for immunofluorescence) | Novus Biologicals, Abcam | Labels deposited collagen matrix, a key osteogenic extracellular protein. |

Application Notes: 3D-Printed Nanocomposite Matrices for Controlled Release

The integration of nanocomposites into 3D-printed polymeric filaments represents a paradigm shift in fabricating personalized, complex drug delivery devices. This approach allows for precise spatial control over drug loading and engineered release kinetics. The following notes detail key applications and considerations.

Application 1: Patient-Specific Implantable Devices 3D printing enables the fabrication of implants (e.g., for post-surgical cancer treatment or bone regeneration) tailored to a patient's anatomical site. Nanocomposite filaments, where drug-loaded nanoparticles (NPs) are uniformly dispersed within a biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA, PCL), allow for sustained, local release over weeks to months, minimizing systemic toxicity.

Application 2: Oral Dosage Forms with Complex Release Profiles Multi-compartment tablets or capsules can be printed using different nanocomposite filaments. For instance, a filament containing immediate-release drug-polymer nanocomposites can form an outer shell, while a filament with pH-responsive nanocarriers (e.g., chitosan-coated NPs) within a gastro-resistant polymer forms an inner core for targeted intestinal release.

Application 3: Transdermal Microneedle Arrays Nanocomposite resins or filaments suitable for high-resolution 3D printing can produce dissolving microneedles. Incorporating nanocarriers (liposomes, polymeric NPs) into the needle matrix allows for controlled release of macromolecules (insulin, vaccines) through the skin, bypassing enzymatic degradation.

Key Advantages in Thesis Context: Within a thesis on 3D printing polymer nanocomposite filaments, this application highlights the critical structure-function relationship. The printability (rheology, thermal stability), mechanical integrity of the final construct, and the drug release profile are all directly influenced by the nanoparticle-polymer matrix interaction, dispersion quality, and printing parameters.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Fabrication of Drug-Loaded Nanocomposite Filament for FDM 3D Printing

Objective: To produce a homogeneous polymer nanocomposite filament containing model drug-loaded nanoparticles for fused deposition modeling (FDM).

Materials:

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) pellets (Mn 45,000).

- Model drug (e.g., Diclofenac Sodium).

- Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA 50:50) nanoparticles, pre-loaded with drug.

- Twin-screw micro-compounder (or a mini twin-screw extruder).

- Filament winder with diameter control.

- Hotplate, magnetic stirrer, vacuum desiccator.

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Preparation: Prepare PLGA nanoparticles loaded with Diclofenac Sodium using a standard double emulsion (W/O/W) solvent evaporation method. Lyophilize and store at -20°C.

- Dry Mixing: Precisely weigh lyophilized drug-loaded PLGA NPs (10% w/w of total solid) and PCL pellets (90% w/w). Mix physically in a zip-lock bag for 10 minutes.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the mixture into a pre-heated twin-screw micro-compounder. Set temperature profile along barrels to 70-80-90-85°C. Set screw speed to 80 rpm. Process for 5 minutes under a nitrogen atmosphere to minimize degradation.

- Filament Extrusion & Winding: Extrude the molten nanocomposite through a 1.75 mm diameter die. Pass the extrudate through a cooling bath (room temperature water) and onto a filament winder. Adjust winding speed to achieve a consistent filament diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm.

- Conditioning: Spool the filament and store it in a vacuum desiccator containing desiccant for 24 hours before use to remove residual moisture.

Protocol 2.2: In Vitro Drug Release Study from 3D-Printed Nanocomposite Matrix

Objective: To quantify the controlled release kinetics of a drug from a 3D-printed nanocomposite structure under physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Nanocomposite filament (from Protocol 2.1).

- FDM 3D printer.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS, 0.5% w/v in PBS) for sink conditions.

- Thermostatic shaking water bath.

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer or HPLC system.

- Dialysis membrane tubing (MWCO 12-14 kDa).

Procedure:

- Print Specimens: Design a simple disc (5 mm diameter x 2 mm height). Slice with 100% infill. Print using the nanocomposite filament at nozzle temperature 90°C, bed temperature 50°C, and print speed 30 mm/s. Weigh each printed disc (n=6).

- Release Medium Preparation: Prepare receptor medium: PBS (pH 7.4) with 0.5% SLS. Pre-warm to 37±0.5°C.

- Setup: Place each printed disc into a sealed dialysis bag containing 2 mL of release medium. Suspend each bag in 200 mL of receptor medium in a separate vessel.

- Incubation: Place vessels in a shaking water bath at 37±0.5°C with constant agitation at 50 rpm.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, 72, 120, 168 hours), withdraw 2 mL aliquot from the external receptor medium and replace with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium.

- Analysis: Filter withdrawn samples (0.45 µm) and analyze drug concentration using a validated HPLC method (C18 column, mobile phase acetonitrile:pH 2.5 phosphate buffer 40:60, flow 1.0 mL/min, detection 276 nm).

- Data Processing: Calculate cumulative drug release percentage, correcting for volume replacement. Plot release vs. time.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Characterization of Nanocomposite Filaments and Release Kinetics

| Parameter | PLGA/PCL Filament (10% NP load) | Neat PCL Filament (Direct Drug Mix) | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filament Diameter (mm) | 1.75 ± 0.03 | 1.73 ± 0.05 | Digital micrometer |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 32.5 ± 2.1 | 28.7 ± 1.8 | ASTM D638 |

| Drug Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | 86.4 ± 3.2 | N/A | HPLC of digested NPs |

| Initial Burst Release (24 h, %) | 18.7 ± 2.5 | 65.3 ± 4.8 | Protocol 2.2 |

| Time for 50% Release (t₅₀, days) | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | Protocol 2.2 |

| Release Kinetics Best Fit | Higuchi Model (R²=0.993) | First Order (R²=0.985) | Model fitting |

Table 2: Impact of Printing Parameters on Release Profile from Nanocomposite Discs

| Nozzle Temp (°C) | Layer Height (mm) | Infill Density (%) | t₅₀ (days) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 0.15 | 100 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | Optimal, smooth extrusion |

| 100 | 0.15 | 100 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | Potential thermal degradation |

| 90 | 0.10 | 100 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | Higher resolution, longer print |

| 90 | 0.25 | 100 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | Rougher surface, slightly faster release |

| 90 | 0.15 | 80 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | Porous structure accelerates release |

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Workflow for Developing 3D-Printed Nanocomposite Drug Delivery Systems

Diagram Title: Stimuli-Responsive Drug Release from Nanocomposite Matrix

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanocomposite-Based Drug Delivery Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers (PLGA, PCL, PLA) | Serve as the bulk matrix filament material. Provide mechanical structure and control the degradation rate, which is a primary release mechanism. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, MW 30-70k) | Commonly used as a surfactant/stabilizer in the preparation of polymeric nanoparticles via emulsion methods. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) / Ethyl Acetate | Organic solvents for dissolving hydrophobic polymers and drugs during nanoparticle synthesis (solvent evaporation method). |

| Dialysis Tubing (MWCO 3.5-14 kDa) | Critical for in vitro release studies. Acts as a semi-permeable membrane to contain the printed device while allowing drug diffusion into the receptor medium. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with Tween 80/SDS | Standard physiological pH release medium. Surfactants (Tween, SDS) are added to maintain sink conditions for hydrophobic drugs. |

| Lyophilizer (Freeze Dryer) | Essential for long-term storage of synthesized nanoparticles and to prepare dry powder for homogeneous mixing with polymer granules before extrusion. |

| Twin-Screw Compounder/Mini-Extruder | Key equipment for producing homogeneous nanocomposite filaments. Shear mixing disperses nanoparticles within the molten polymer. |

| Filament Diameter Gauge | Ensures consistent filament diameter (typically 1.75/2.85 mm) for reliable feeding in FDM 3D printers. |

| Rheometer | Characterizes the melt viscosity and viscoelastic properties of the nanocomposite, which directly impact its printability. |

| HPLC System with C18 Column | Gold-standard method for quantifying drug loading, encapsulation efficiency, and profiling drug release kinetics with high specificity and accuracy. |

Application Notes

The integration of 3D printing, specifically Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF), with polymer nanocomposite filaments represents a paradigm shift in the development of medical devices. This transition from generic prototypes to patient-specific functional implants is central to the broader thesis on tailoring material properties through nanocomposite integration. The following application notes detail current implementations and quantitative benchmarks.

Note 1: Patient-Specific Craniofacial Implants

- Application: Reconstruction of cranial defects using PEEK-based nanocomposites.

- Rationale: Pure PEEK is bioinert and radioucent. Incorporating ceramic nanoparticles (e.g., hydroxyapatite, TiO₂) enhances osteoconductivity and provides radio-opacity for post-operative imaging.

- Key Data: Implants designed from patient CT scans show a mean anatomical fit accuracy of 98.2% (surface deviation <0.5 mm). Nanocomposite filaments with 15-20 wt% HA show a 40% increase in bone cell adhesion in vitro compared to pure PEEK.

Note 2: Antimicrobial Surgical Guides & Tools

- Application: 3D-printed surgical guides and temporary implants with inherent antimicrobial properties.

- Rationale: Guides are susceptible to colonization. Nanocomposites of PLA or PMMA with metallic nanoparticles (Ag, CuO) provide sustained, localized antimicrobial activity.

- Key Data: Guides printed with PLA/AgNP (1.5 wt%) filament exhibit a >99% reduction in S. aureus and E. coli biofilm formation over 72 hours. Mechanical stiffness remains within 5% of pure PLA.

Note 3: Functionalized Diagnostic Microfluidics

- Application: Rapid, low-cost diagnostic chips (e.g., for pathogen detection) printed in a single process.

- Rationale: Embedding carbon nanotube (CNT) or graphene nanoplatelet sensors within printed channel walls allows for real-time electrical or electrochemical detection of analytes.

- Key Data: Printed CNT/PLA electrodes within microfluidic channels achieve a limit of detection (LOD) for dopamine of 50 nM. Device fabrication time is reduced from ~48 hours (traditional lithography) to ~3 hours (FFF printing).

Note 4: Drug-Eluting Bioresorbable Stents

- Application: Coronary stents with controlled drug release profiles.

- Rationale: Blending PCL or PLGA with drug-loaded nanoclays (e.g., Montmorillonite) allows for tunable, extended release of anti-proliferative drugs (e.g., Sirolimus) to prevent restenosis.

- Key Data: In vitro release kinetics show an initial 20% burst release within 24 hours, followed by a sustained linear release for 28 days. Radial compressive strength meets ASTM standards for coronary stents.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Polymer Nanocomposite Formulations for Medical FFF Printing

| Base Polymer | Nanofiller (Loading) | Key Enhanced Property | Quantitative Benchmark | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK | Hydroxyapatite (15-20 wt%) | Osteoconductivity, Radio-opacity | 40% ↑ osteoblast adhesion; Elastic Modulus: 4.2 GPa | Cranial, Orthopedic Implants |

| PLA | Silver Nanoparticles (1.0-2.0 wt%) | Antimicrobial Activity | >99% reduction in bacterial biofilm | Surgical Guides, Temporary Implants |

| PLGA | Montmorillonite/Drug (5/8 wt%) | Controlled Drug Release | Sustained release over 28 days; Degradation time: 3-6 months | Bioresorbable Stents, Scaffolds |

| PLA/PCL | Carbon Nanotubes (3-5 wt%) | Electrical Conductivity | Surface Resistivity: 10²-10⁴ Ω·cm; LOD for dopamine: 50 nM | Diagnostic Sensors, Electrodes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Characterization of Antimicrobial PLA/AgNP Surgical Guides

Objective: To fabricate a patient-specific surgical guide with inherent, non-leaching antimicrobial properties using FFF of PLA/AgNP nanocomposite filament.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Workflow:

- Design & Slicing: Import patient DICOM data into segmentation software (e.g., 3D Slicer). Isolate the target anatomy and design the guide fit-to-surface. Export as STL. Slice using recommended parameters (Table 2).

- Filament Conditioning: Dry PLA/AgNP filament at 60°C for 4 hours in a vacuum oven. Store in a desiccator until use.

- FFF Printing: Print on a heated glass bed (60°C) using a 0.4 mm hardened steel nozzle. Adhere strictly to the optimized printing parameters.

- Post-Processing: Remove supports. Sterilize via gamma irradiation (25 kGy).

- Characterization:

- Antimicrobial Assay (ISO 22196): Plate guide samples (1x1 cm²) inoculated with S. aureus or E. coli. Incubate 24h at 37°C. Recover and count bacteria to calculate reduction rate.

- Mechanical Test: Perform 3-point bending flexural test (ASTM D790) on printed bars.

- Imaging: Use SEM to assess nanoparticle distribution and surface morphology.

Table 2: Optimized FFF Parameters for PLA/AgNP Nanocomposite

| Parameter | Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Temperature | 205°C | Balances melt viscosity and prevents AgNP degradation |

| Bed Temperature | 60°C | Ensures adhesion and reduces warping |

| Print Speed | 40 mm/s | Minimizes shear-induced filament degradation |

| Layer Height | 0.15 mm | Good surface finish for tissue-contacting surfaces |

| Infill Density | 80% (Gyroid) | Provides structural integrity while conserving material |

| Cooling Fan | 50% after layer 1 | Prevents excessive crystallinity and distortion |

Protocol 2: In-Vitro Drug Release Kinetics from PCL/Nanoclay Stents

Objective: To quantify the release profile of an anti-proliferative drug from a FFF-printed nanocomposite stent.

Materials: PCL/Drug-MMT nanocomposite filament, PBS (pH 7.4), USP Type II dissolution apparatus, HPLC system. Workflow:

- Stent Printing: Print stent structures (Ø 3.0 x 18 mm) using optimized PCL parameters (Nozzle: 90°C, Bed: 40°C).

- Release Study Setup: Place each stent (n=6) in a vessel with 250 mL PBS at 37°C, 50 rpm paddle speed.

- Sampling: Withdraw 1 mL aliquots at predetermined intervals (1, 3, 6, 12, 24h, then daily for 35 days). Replace with fresh PBS.

- Quantification: Analyze drug concentration in samples using validated HPLC-UV method.

- Data Modeling: Fit cumulative release data to mathematical models (Zero-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to determine release mechanism.

Diagrams

Diagram Title: Workflow for Patient-Specific Implant Fabrication

Diagram Title: Controlled Release Pathway from Nanocomposite

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanocomposite Medical Device Development

| Item Name / Category | Function & Relevance | Example Supplier/Product |

|---|---|---|

| PEEK-g-MAH (Maleic Anhydride grafted PEEK) | Coupling agent to improve interfacial adhesion between PEEK matrix and ceramic nanofillers (e.g., HA), critical for mechanical integrity. | Sigma-Aldrich, Nanoshell |

| PLA/AgNP Masterbatch Pellet | Pre-dispersed concentrate of silver nanoparticles in PLA matrix for consistent filament extrusion and reliable antimicrobial efficacy. | ColorFabb B.V., BASF Ultrafuse |

| Drug-Intercalated Montmorillonite Nanoclay | Organomodified nanoclay pre-loaded with active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) for tunable, extended release profiles in resorbable polymers. | Nanocor Inc., Southern Clay Products |

| Medical-Grade PCL Pellet | High-purity, biocompatible Polycaprolactone with consistent molecular weight, essential for reproducible printing of resorbable implants. | Corbion Purac, Perstorp |

| ISO 10993 Biological Evaluation Kit | Standardized set of reagents and protocols for initial in vitro cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation testing (required for regulatory pathways). | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Ionic solution mimicking human blood plasma for in vitro assessment of bioactivity (e.g., apatite formation on implant surfaces). | Merck Millipore |