Advanced Polymer Processing Optimization: Integrating AI, Statistical Methods, and Physics-Informed Approaches for Enhanced Product Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern optimization techniques in polymer processing, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

Advanced Polymer Processing Optimization: Integrating AI, Statistical Methods, and Physics-Informed Approaches for Enhanced Product Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern optimization techniques in polymer processing, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It explores the foundational principles of optimization, details advanced methodologies from evolutionary algorithms to data-driven models, and presents systematic troubleshooting frameworks. By comparing the efficacy of various validation techniques and optimization approaches, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing the most suitable methods to achieve superior product quality, process efficiency, and sustainability in polymer-based product development.

The Critical Role of Optimization in Modern Polymer Processing: Principles and Drivers

Polymer processing optimization has evolved from a reliance on tacit operator knowledge and inefficient trial-and-error methods to a systematic, data-driven engineering discipline. In today's manufacturing landscape, characterized by volatile feedstock costs, fluctuating energy prices, and tightening quality specifications, systematic optimization is no longer a luxury but a necessity for maintaining competitiveness [1]. Traditional process control technologies often fall short in delivering the performance enhancements needed to address these mounting pressures.

The fundamental goal of polymer processing optimization is to determine the optimal set of process parameters—including operating conditions and equipment geometry—that yield the best possible product quality and process efficiency while minimizing resource consumption [2] [3]. This transformation from empirical methods to systematic design represents a paradigm shift that leverages computational modeling, advanced optimization algorithms, and artificial intelligence to unlock new levels of operational excellence.

The Economic and Technical Imperative for Optimization

The business case for implementing systematic optimization methodologies in polymer processing is compelling. Non-prime or off-spec production represents one of the most significant hidden costs in polymer manufacturing, accounting for 5-15% of total output in specialty polymers and complex polymerization processes [1]. This off-spec material not only represents inefficient use of raw materials but also leads to increased reprocessing costs, scrap expenses, and missed delivery deadlines.

Energy consumption remains another major component of operating expenses in polymer plants, with traditional approaches often struggling to reduce energy usage without sacrificing throughput or quality [1]. Systematic optimization challenges this historical trade-off by identifying hidden capacity within existing equipment, enabling simultaneous throughput gains and energy savings.

Table 1: Quantitative Benefits of Systematic Optimization in Polymer Processing

| Performance Metric | Traditional Approach | With Systematic Optimization | Key Enabling Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-spec Production | 5-15% of total output [1] | >2% reduction [1] | Closed-loop AI optimization, Machine learning |

| Energy Consumption | High and inflexible | 10-20% reduction in natural gas consumption [1] | Real-time setpoint adjustment, Multi-objective optimization |

| Throughput | Limited by conservative operation | 1-3% increase [1] | AI-driven capacity unlocking, Reduced process variability |

| Development Time for New Materials | Months of experimental work | Significant reduction through computational prediction [4] | Convolutional Neural Networks, QSPR models |

Foundational Methodologies and Algorithms

The mathematical foundation of polymer processing optimization involves formulating real-world problems as Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (MOOPs), where multiple, often conflicting objectives must be satisfied simultaneously [2]. Common objectives include minimizing energy consumption, cycle time, and residual stress while maximizing throughput, product quality, and degree of cure.

Optimization Algorithm Selection

Different optimization algorithms offer varying capabilities for addressing polymer processing challenges. The selection of an appropriate algorithm depends on the problem characteristics, including whether it involves single or multiple objectives, the nature of the objective space, and the need to find global optima.

Table 2: Optimization Algorithms for Polymer Processing Applications

| Algorithm | Single Objective | Global Optimum | Discontinuous Objective Space | Multi-Objective | Flexibility | Typical Polymer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Methods | +++ | - | - | --- | --- | Die design, mold flow balancing |

| Simulated Annealing | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | Cure cycle optimization |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | +++ | + | + | +++ | + | Injection molding parameters |

| Artificial Bee Colony | +++ | + | + | +++ | + | Extruder screw design |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | Multi-objective process optimization |

| Bayesian Optimization | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | Computationally expensive simulations [5] |

Key: +++ (Excellent), ++ (Good), + (Fair), - (Poor), --- (Very Poor) [2]

Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization for Cure Cycle Design

Bayesian optimization has emerged as a particularly powerful approach for optimizing polymer composite manufacturing processes, which typically involve computationally expensive simulations. Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) utilizes probabilistic surrogate models, typically Gaussian Processes (GP), to guide the optimization process while providing uncertainty estimates in unexplored regions of the design space [5].

This approach is especially valuable for optimizing cure cycles for thermoset composites, where the exothermic nature of the curing reaction can lead to thermal gradients, uneven degree of cure, and residual stresses if not properly controlled [5]. Unlike traditional methods that require thousands of finite element analysis (FEA) simulations, MOBO can achieve convergence with significantly fewer evaluations by intelligently selecting the most promising points to evaluate based on an acquisition function.

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Computational Screening of Functional Monomers for Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

Purpose: To rationally design molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) through computational screening of functional monomers, reducing reliance on trial-and-error experimentation [6].

Background: Molecularly imprinted polymers are synthetic materials with specific recognition sites for target molecules. Traditional development involves extensive laboratory experimentation to identify optimal monomer-template combinations.

Materials and Equipment:

- Template molecule (e.g., sulfadimethoxine for veterinary drug detection)

- Candidate functional monomers (e.g., acrylic acid, methacrylic acid, 4-vinylbenzoic acid)

- Computational chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian for quantum chemical calculations)

- Molecular dynamics simulation environment

- Linux-based high-performance computing cluster

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the chemical structure of the template molecule in standard format (SMILES, MOL2, or PDB).

- Generate 3D coordinates and optimize geometry using molecular mechanics force fields.

Quantum Chemical (QC) Calculations:

- Perform conformational analysis of the template and monomer molecules.

- Optimize all structures at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory.

- Calculate electrostatic potential surfaces and natural bond orbital (NBO) charges.

- Evaluate template-monomer complexes in vacuum and implicit solvent models.

- Compute binding energies (ΔEbind) for 1:1 template-monomer complexes.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- Construct pre-polymerization mixtures containing template, functional monomer, cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA), and solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) in explicit solvent models.

- Run MD simulations for 10-50 ns using appropriate force fields (e.g., GAFF, CGenFF).

- Analyze hydrogen bond occupancy, radial distribution functions, and binding modes.

- Calculate quantitative parameters: Effective Binding Number (EBN) and Maximum Hydrogen Bond Number (HBNMax).

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top-ranked MIP candidates using surface-initiated supplemental activator and reducing agent atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-SARA ATRP).

- Perform binding experiments to validate computational predictions.

Data Analysis:

- Higher EBN and HBNMax values indicate more effective binding efficiency.

- Optimal template-to-monomer ratios are typically identified at 1:3 based on EBN and collision probability analysis [6].

- Carboxylic acid monomers generally exhibit higher bonding energies with template molecules than carboxylic ester monomers [6].

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop AI Optimization for Polymerization Processes

Purpose: To implement real-time, closed-loop artificial intelligence optimization for polymerization processes to reduce off-spec production and energy consumption [1].

Background: Traditional control strategies based on first-principles models often fail to capture complex nonlinear relationships and disturbances in polymerization processes, leading to suboptimal performance and quality variations.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymerization reactor with instrumented sensors (temperature, pressure, flow rates)

- Process historian or data acquisition system

- Laboratory information management system (LIMS) for quality data

- Closed-loop AI optimization software (e.g., Imubit AIO platform)

- Secure network infrastructure for data transfer

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Preparation:

- Extract 12-24 months of historical process data, including:

- Time-series sensor data (temperature, pressure, flow rates)

- Laboratory-measured product quality results

- Operator interventions and setpoint changes

- Feedstock quality information

- Clean data by removing periods of maintenance, startup, and shutdown.

- Align process data with quality data using appropriate time offsets.

- Extract 12-24 months of historical process data, including:

Model Development and Training:

- Identify key process variables and quality parameters for optimization.

- Train machine learning models to predict product quality based on process conditions.

- Validate model performance using hold-out datasets and cross-validation.

- Establish operating constraints and safety limits for closed-loop operation.

Closed-Loop Implementation:

- Deploy AI models in real-time optimization mode.

- Implement setpoint adjustments initially in open-loop (recommendation) mode.

- Establish operator trust through explainable AI and transparency in recommendations.

- Transition to closed-loop operation with appropriate safety interlocks.

- Continuously monitor model performance and retrain as process characteristics change.

Performance Monitoring:

- Track key performance indicators (KPIs): off-spec rate, energy consumption, throughput.

- Compare pre- and post-implementation performance using statistical process control.

- Conduct regular reviews with operations team to identify improvement opportunities.

Data Analysis:

- Typical results include 1-3% throughput increase, 10-20% reduction in natural gas consumption, and over 2% reduction in off-spec production [1].

- Reactor temperature optimization can lead to seven-figure annual savings in catalyst-intensive processes through optimized catalyst use [1].

Protocol 3: Bayesian Optimization of Composite Cure Cycles

Purpose: To optimize thermal cure cycles for fiber-reinforced thermoset polymer composites using Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) to minimize process time and residual stresses while ensuring complete cure [5].

Background: Manufacturer-recommended cure cycles are often conservative and do not account for specific part geometry or reinforcement materials, leading to unnecessarily long cycle times or suboptimal part quality.

Materials and Equipment:

- Thermoset composite material (pre-preg or resin-infiltrated reinforcement)

- Cure kinetics model for the resin system

- Multiscale finite element analysis software

- Bayesian optimization framework (e.g., GPyOpt, BoTorch, or custom MATLAB/Python code)

- Thermal analysis equipment (DSC, TMA) for model validation

Procedure:

- Characterize Cure Kinetics:

- Perform differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments to determine kinetic parameters.

- Fit kinetic model (e.g., autocatalytic model) to experimental data.

- Characterize glass transition temperature (Tg) evolution with degree of cure.

Develop Multiscale Process Model:

- Create representative volume element (RVE) models to capture micro-scale material behavior.

- Develop macro-scale finite element model of the composite part.

- Couple heat transfer, cure kinetics, and stress development in the model.

- Validate model predictions against experimental measurements.

Define Optimization Problem:

- Design Variables: Cure cycle parameters (hold temperatures, times, ramp rates)

- Objectives: Minimize total process time, minimize transverse residual stress, maximize final degree of cure

- Constraints: Maximum temperature limit (to prevent degradation), minimum final degree of cure (e.g., >0.95)

Implement Bayesian Optimization:

- Select Gaussian Process prior and acquisition function (e.g., q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement).

- Generate initial design points using Latin Hypercube Sampling.

- Run iterative optimization: a. Evaluate candidate cure cycles using multiscale FEA b. Update Gaussian Process surrogate model with results c. Select next candidate points using acquisition function d. Check convergence criteria (e.g., hypervolume improvement < tolerance)

- Extract Pareto-optimal set of cure cycles.

Experimental Validation:

- Manufacture composite parts using optimized cure cycles.

- Measure residual stresses, degree of cure, and mechanical properties.

- Compare with parts manufactured using standard cure cycles.

Data Analysis:

- Bayesian optimization typically requires significantly fewer function evaluations (FEA runs) compared to traditional methods like Genetic Algorithms [5].

- Results typically show significant reduction in process time and residual stresses compared to manufacturer-recommended cycles while maintaining or improving degree of cure [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Polymer Processing Optimization

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Form specific interactions with template molecules in MIPs [6] | Acrylic acid (AA), Methacrylic acid (MAA), 4-vinylbenzoic acid (4-VBA), Trifluoromethylacrylic acid (TFMAA) |

| Cross-linkers | Create rigid polymer network in MIPs; stabilize binding sites [6] | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), Trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TRIM) |

| Quantum Chemical Calculation Software | Predict monomer-template binding energies and interaction modes [6] | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, NWChem (B3LYP/6-31G(d) level) |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation Packages | Simulate pre-polymerization mixtures and analyze binding dynamics [6] | GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD, AMBER (with GAFF or CGenFF force fields) |

| Finite Element Analysis Software | Model cure kinetics, heat transfer, and stress development [5] | ABAQUS, COMSOL, ANSYS (with custom user subroutines for cure kinetics) |

| Bayesian Optimization Frameworks | Efficient global optimization for expensive black-box functions [5] | GPyOpt, BoTorch, MATLAB Bayesian Optimization, Scikit-Optimize |

| Convolutional Neural Network Platforms | Predict polymer properties from chemical structure [4] | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras (with custom architectures for SMILES processing) |

| Process Data Historians | Store and retrieve temporal process data for AI model training [1] | OSIsoft PI System, AspenTech InfoPlus.21, Siemens SIMATIC PCS 7 |

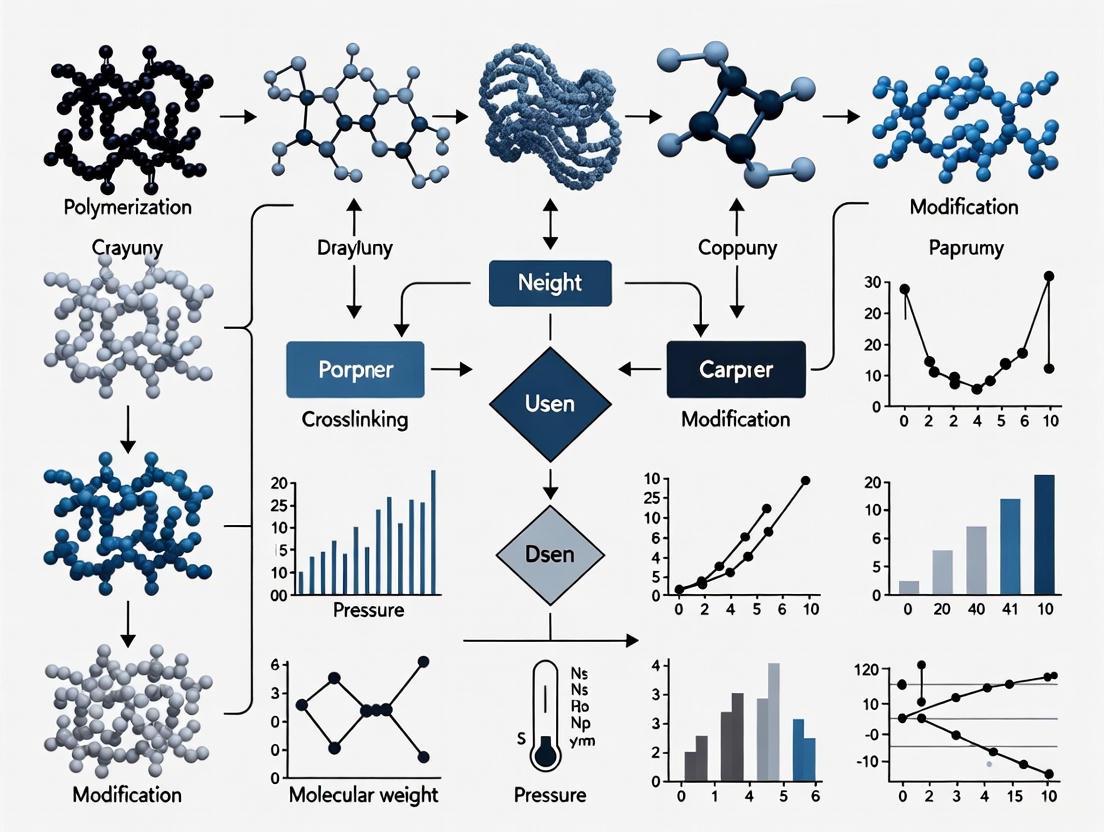

Workflow Visualization

Systematic Optimization Workflow for Polymer Processing

Computer-Aided Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers

The field of polymer processing optimization continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. The integration of AI and machine learning across multiple scales—from molecular design to process control—represents the most significant advancement. Convolutional neural networks can now predict key polymer properties such as glass transition temperature with approximately 6% relative error based solely on chemical structure encoded in SMILES notation [4]. This capability enables accelerated materials design without costly synthesis and experimentation.

As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, we anticipate wider adoption of digital twin technology in polymer manufacturing, where virtual replicas of processes enable real-time optimization and predictive maintenance. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on sustainability and circular economy principles will drive optimization efforts toward minimizing energy consumption, reducing waste, and enabling polymer recyclability through intelligent process design.

The transformation from trial-and-error to systematic design in polymer processing represents a fundamental shift that empowers researchers and manufacturers to achieve unprecedented levels of efficiency, quality, and sustainability. By leveraging the methodologies, protocols, and tools outlined in this article, the polymer industry can accelerate innovation and maintain competitiveness in an increasingly challenging global landscape.

The polymer processing industry faces increasing pressure to balance economic viability with environmental responsibility. Rising energy costs, volatile feedstock prices, and stringent sustainability regulations are driving the adoption of strategies that minimize waste and reduce energy consumption. Within the broader context of polymer processing optimization research, this paper details practical protocols and application notes for implementing these strategies, focusing on technical approaches that align economic benefits with ecological stewardship. The transition from traditional linear models to a circular economy framework is imperative, requiring innovations in process engineering, material science, and digital technologies [7]. This document provides a structured framework for researchers and industry professionals to implement these advancements effectively.

The tables below summarize key quantitative data on waste management trends and the potential benefits of optimization strategies, providing a baseline for research and implementation planning.

Table 1: Polymer Waste Management Market and Material Trends (2024-2030)

| Category | Specific Metric | Value / Trend | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | Global Polymer Waste Management Market (2024) | USD 4.87 Billion | [8] |

| Projected Market Size (2030) | USD 6 Billion | [8] | |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 2.7% | [8] | |

| Material Segments | HDPE Share of Market Earnings (2024) | 53.1% | Driven by high recyclability for packaging and infrastructure [8] |

| High-Growth Segment | EPDM | For geomembranes, roofing, and solar panels due to durability [8] | |

| Regional Analysis | Asia Pacific Market Share (2024) | 36.9% of global revenue | Large populations and high plastic consumption in China and India [8] |

| Fastest-Growing Region | North America | Driven by policies like single-use plastic bans in federal operations by 2035 [8] |

Table 2: Quantified Benefits of Optimization Strategies in Polymer Processing

| Strategy | Key Performance Indicator | Reported Improvement | Context and Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Process Optimization | Reduction in Off-Spec Production | >2% reduction | Leads to millions in annual savings [1] |

| Increase in Throughput | 1-3% average increase | Achieved without capital expenditure on new equipment [1] | |

| Reduction in Natural Gas Consumption | 10-20% | In polymer production units [1] | |

| Energy Efficiency in Extrusion | Motor/Drive System Upgrade | 10-15% energy savings | From switching to direct-drive systems, eliminating gearboxes [9] |

| Enhanced Heating Techniques | ~10% cut in total heating energy | Using induction heating with proper insulation [9] | |

| Waste Heat Recovery | Reclaim up to 15% of lost energy | Using surplus thermal energy to pre-heat feedstock [9] | |

| Corporate Case Study | Electricity Consumption Reduction | 28% over three years | MGS Technical Plastics, while increasing turnover [10] |

| Carbon Footprint Reduction | 41% in four years | MGS Technical Plastics [10] |

Application Note: Closed-Loop AI Optimization for Polymer Processing

Background and Principle

Closed-Loop Artificial Intelligence Optimization (AIO) leverages machine learning and real-time plant data to push complex polymerization processes to their optimal state. This strategy directly addresses major economic drivers: the cost of off-spec production, which can account for 5-15% of total output, and high energy consumption. Unlike traditional physics-based models, AIO learns complex, non-linear relationships from data to maintain ideal conditions despite disturbances like feedstock variability or reactor fouling [1].

Experimental Protocol for AIO Implementation

Objective: To implement a closed-loop AI system to reduce energy consumption and off-spec production in a polymerization reactor.

Materials and Reagents:

- Data Historian: A centralized database (e.g., OSIsoft PI System) collecting at least one year of historical process data.

- Sensor Network: Calibrated sensors for temperature, pressure, flow rates, and motor load.

- Lab Analysis Data: Data on critical product quality properties (e.g., Molecular Weight Distribution, Melt Flow Index) linked to process timestamps.

- AI Software Platform: A closed-loop AI optimization platform (e.g., from vendors like Imubit).

- Polymerization Reactor System: A representative industrial-scale reactor for validation.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Extract a minimum of 12 months of high-frequency (e.g., per minute) historical data from the data historian for all relevant process variables.

- Merge this dataset with laboratory quality analysis results, ensuring accurate time alignment.

- Perform data cleaning, including handling of missing values, filtering of outliers, and removal of periods of significant plant shutdown or malfunction.

Model Training and Validation:

- The AI platform uses machine learning to train a model that correlates the cleaned process data (inputs) with the resulting product quality (outputs).

- The model is validated against a held-out portion of historical data not used in training. The model must accurately predict key quality parameters within a predefined margin of error (e.g., ±5%) before proceeding.

Closed-Loop Implementation and Testing:

- The validated AI model is deployed in a closed-loop system. It continuously reads real-time process data and dynamically adjusts key setpoints (e.g., reactor temperature profiles, catalyst feed rates) to maintain optimal conditions.

- Conduct a controlled trial, comparing a period of AIO-driven operation against a baseline period of standard operational practice.

- Monitor and record the rate of off-spec production, total energy consumption (e.g., natural gas, electricity), and throughput during both periods.

Analysis and Scaling:

- Calculate the difference in key performance indicators (KPIs) between the trial and baseline periods. Perform statistical analysis to confirm the significance of the improvements.

- Based on the successful trial, the AIO system can be scaled to other reactors or units within the plant.

Troubleshooting:

- Model Drift: Periodically retrain the AI model with new data to account for long-term process changes.

- Operator Adoption: Ensure transparency by providing operators with explainable AI recommendations to build trust and facilitate collaboration [1].

Application Note: Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Polymer Extrusion

Background and Principle

Polymer extrusion is a highly energy-intensive process, with significant losses occurring in motor drives, heating, and cooling systems. Modern optimization strategies target these specific loss mechanisms through hardware upgrades and smart process control, offering energy savings of 25-40% [9]. This directly reduces operational costs and the carbon footprint of production.

Experimental Protocol for Systematic Extrusion Efficiency Audit

Objective: To identify, quantify, and mitigate energy inefficiencies in a single-screw polymer extrusion line.

Materials and Reagents:

- Power Analyzer: A portable, calibrated power analyzer (e.g., Fluke 434 Series II) for measuring voltage, current, power factor, and harmonic distortion.

- Thermal Imaging Camera: An infrared camera to identify thermal leaks and poor insulation.

- Data Acquisition System: A system to log temperature, pressure, and motor load data.

- Representative Polymer Resin: A standard polymer (e.g., Polypropylene) to be used under consistent processing conditions.

Procedure:

- Baseline Energy Assessment:

- Install the power analyzer at the main electrical feed to the extruder. Record total energy consumption (kWh) over a stable 8-hour production run.

- Use the thermal camera to scan the entire barrel heating zones, die, and cooling units. Document areas of significant heat loss.

- Measure and record the temperature profile along the barrel, pressure at the die, and screw speed.

Motor and Drive System Evaluation:

- Using the power analyzer, measure the load factor and power factor of the main drive motor during operation.

- Compare the motor's operating efficiency to its nameplate efficiency. Calculate the potential energy savings from upgrading to a modern AC vector drive or a direct-drive system [9].

Heating and Cooling System Analysis:

- Heating: Calculate the heat-up time from ambient to processing temperature. Assess the feasibility of retrofitting resistance heaters with induction heating, which provides faster, more uniform heating with less loss [9].

- Cooling: Monitor the temperature differential and flow rate of the cooling water. Evaluate if a conformal cooling system or an optimized air-cooling system could provide more uniform cooling with lower energy and water usage.

Waste Heat Recovery Feasibility Study:

- Measure the temperature of exhaust air or cooling water outputs.

- Model the technical and economic feasibility of installing a heat exchanger to capture this waste energy for pre-heating incoming feedstock or for space heating [9].

Implementation and Verification:

- Prioritize and implement the most cost-effective upgrades identified in the audit.

- Repeat the baseline assessment post-implementation to quantify the energy savings and ROI.

Protocol for Electrochemical Upcycling of Polymer Waste

Background and Principle

Traditional mechanical recycling struggles with mixed waste streams and leads to down-cycled materials. Chemical upcycling transforms waste into high-value materials. This protocol is based on a novel electrochemical method that functionalizes oligomers from recycling processes, enabling their re-assembly into new, high-performance thermoset materials [11]. This closes a critical loop for materials like carbon-fiber reinforced polymers (CFRPs).

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Objective: To convert low-value oligomer byproducts from CFRP recycling into a new covalently adaptable network (CAN) with restored mechanical properties via dual C-H functionalization using electrolysis.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Upcycling

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Oligomer Byproducts | Feedstock; short-chain polymer fragments from the deconstruction of CFRPs or similar cross-linked materials. |

| Electrolyte Salt | Conducts ionic current within the electrochemical cell, enabling the electrolysis reaction. |

| Solvent (Anhydrous) | Dissolves the oligomers and electrolyte to create a homogeneous reaction medium. |

| Working Electrode | Surface where the oxidation reaction takes place, functionalizing the oligomer backbone. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow through the cell. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential to accurately control and measure the working electrode's potential. |

| Potentiostat | Precision instrument that applies a controlled electrical potential/current to the electrochemical cell. |

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the oligomer byproducts in an anhydrous solvent with a supporting electrolyte salt (e.g., 0.1 M) in an inert atmosphere glovebox.

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Assemble a standard three-electrode cell (e.g., with a glassy carbon working electrode, platinum counter electrode, and Ag/Ag+ reference electrode). Purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) to remove oxygen.

- Electrolysis (Dual C-H Functionalization):

- Using the potentiostat, apply a controlled potential sufficient to drive the dual carbon-hydrogen functionalization of the oligomer backbone. The reaction installs two key functional groups (e.g., alkene and oxygenated groups) at tertiary allylic C-H sites.

- Continue electrolysis until the charge passed indicates the desired degree of functionalization (e.g., 2.5 F/mol).

- Work-up and Network Formation:

- After the reaction, precipitate the functionalized oligomers into a non-solvent, then filter and dry them.

- The installed functional groups (e.g., aldehydes and alkenes) can now cross-link. Heat the modified oligomers to induce a network-forming reaction, creating a new covalently adaptable network (CAN).

- Material Characterization:

- Use Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to confirm the successful functionalization of the oligomer chain.

- Perform dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) and tensile testing to evaluate the mechanical properties (e.g., storage modulus, tensile strength) of the newly formed CAN material and compare them to the original oligomer waste.

Visual Workflows and Research Toolkit

Integrated Strategy for Sustainable Polymer Processing

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between the core strategies discussed in this document, forming a comprehensive approach to sustainability.

Electrochemical Upcycling Workflow

This diagram details the specific experimental workflow for the electrochemical upcycling protocol.

In the realm of polymer processing and drug development, process designers are invariably faced with a fundamental challenge: the need to simultaneously optimize multiple, often conflicting, criteria. A perfect configuration that maximizes all desired outcomes rarely exists. Instead, improvements in one objective, such as product performance, frequently come at the expense of another, like manufacturing cost or production speed. This inherent conflict frames the Multi-Objective Optimization Problem (MOOP). The solution is not a single optimal point but a set of trade-off solutions known as the Pareto front, where any improvement in one objective necessitates a deterioration in at least one other [12]. Within the broader thesis on polymer processing optimization, understanding these core challenges is paramount for developing efficient, intelligent, and robust manufacturing systems. This article delineates these challenges and provides structured protocols for addressing them, with a focus on applications in polymer processing and pharmaceutical development.

Core Challenges in Multi-objective Optimization

Navigating multi-objective problems requires an understanding of the specific hurdles that complicate the search for a satisfactory set of solutions. The primary challenges can be categorized as follows:

The Curse of Dimensionality in Objective Space: As the number of objectives increases beyond three, the problem transitions into a Many-Objective Optimization Problem (MaOP). This shift introduces significant challenges:

- Loss of Selection Pressure: In many-objective problems, almost every solution in a population becomes non-dominated, causing Pareto-based dominance relations to fail in effectively guiding the search toward the true Pareto front [12].

- Visualization and Decision-Making Difficulty: Visualizing a high-dimensional Pareto front is impractical for human decision-makers, complicating the final solution selection process.

- Poor Scalability of Algorithms: Many algorithms designed for two or three objectives experience a severe performance degradation when applied to problems with a higher number of objectives, as they cannot adequately sample the exponentially growing objective space [12].

Conflicting and Non-Commensurable Objectives: The very nature of MOOPs involves objectives that are both conflicting and measured on different scales. For instance, in polymer processing, a goal might be to maximize the mechanical strength of a component while minimizing its production cycle time and material usage [3]. These units (e.g., MPa, seconds, kilograms) are non-commensurable, making direct comparison and aggregation into a single objective function non-trivial and often misleading.

Computational Expense and the Need for Surrogates: High-fidelity simulations, such as Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for modeling water-assisted injection molding, are computationally intensive [13]. Evaluating thousands of candidate solutions via these simulations in an iterative optimization loop is often prohibitively expensive. This necessitates the use of surrogate models—fast, approximate models like Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) that are trained on simulation data to replace costly simulations during the optimization process [13].

Dynamic Environments: In real-world manufacturing, conditions are not always static. A Dynamic Multi-Objective Optimization Problem (DMOOP) arises when the Pareto front and Pareto set change over time due to shifting environmental parameters, such as material property variations or machine wear [14]. This requires algorithms that can not only find the Pareto optimal set but also track its movement over time, demanding robust response mechanisms like diversity introduction or prediction strategies.

Quantitative Data on Common Conflicts

The table below summarizes typical conflicting objectives encountered in polymer processing and drug design, illustrating the practical manifestation of these core challenges.

Table 1: Common Conflicting Objectives in Process Design

| Field | Objective 1 (Typically to Maximize) | Objective 2 (Typically to Minimize) | Conflicting Relationship & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection Molding [15] | Dimensional Stability (e.g., minimize warpage) | Production Efficiency (e.g., minimize volumetric shrinkage, cycle time) | Process parameters that reduce warpage (e.g., higher pressure, slower cooling) often increase cycle time and may affect shrinkage, creating a direct trade-off. |

| Polymer Extrusion [3] | Output Rate | Energy Consumption / Melt Homogeneity | Increasing screw speed boosts output but raises energy consumption through viscous dissipation and can compromise mixing quality. |

| Water-Assisted Injection Molding (WAIM) [13] | Hollow Core Ratio (R_HC) |

Wall Thickness Deviation (D_WT) |

Achieving a large, consistent hollow channel (high R_HC) is often in conflict with maintaining a uniform wall thickness (low D_WT) across a complex part geometry. |

| de novo Drug Design [12] | Drug Potency / Binding Affinity | Synthesis Cost / Toxicity | Designing a molecule with very high affinity for a target receptor may require a complex, expensive-to-synthesize structure or could lead to increased off-target interactions and toxicity. |

Methodologies and Algorithmic Solutions

A variety of computational strategies have been developed to tackle MOOPs, each with distinct strengths for handling the challenges outlined above.

Table 2: Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm Class | Example Algorithms | Key Mechanism | Strengths | Common Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) | NSGA-II, NSGA-III [13] | Uses non-dominated sorting and crowding distance to evolve a population of solutions toward the Pareto front. | Well-suited for complex, non-linear problems; finds a diverse set of solutions in a single run. | Polymer processing [3], de novo drug design [12]. |

| Swarm Intelligence | Multi-Objective PSO (MOPSO) [16] | Particles fly through the search space, guided by their own experience and the swarm's best known positions. | Fast convergence; simple implementation. | Protein structure refinement (AIR method) [16]. |

| Surrogate-Assisted EAs | ANN + NSGA-II [13] | Replaces computationally expensive simulations (CFD) with fast, data-driven models (ANN) for fitness evaluation. | Dramatically reduces computational cost; makes optimization of complex simulations feasible. | WAIM optimization [13], Injection molding [15]. |

| Prediction-Based for DMOPS | DVC Method [14] | Classifies decision variables as convergence- or diversity-related and uses different prediction strategies for each after an environmental change. | Effectively balances convergence and diversity in dynamic environments. | Theoretical and applied dynamic problems. |

Workflow for Multi-Objective Process Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, integrated workflow for applying these methodologies to a process design problem, such as optimizing a polymer manufacturing technique.

Diagram 1: Multi-Objective Process Optimization Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Surrogate-Assisted Optimization for Injection Molding

This protocol details the methodology for minimizing warpage and volumetric shrinkage in plastic sensor housings, as presented in a 2025 study [15].

- Objective: To minimize warpage deformation and volumetric shrinkage of an injection-molded sensor housing.

- Materials & Software:

- Plastic Material: The specific polymer grade used for the sensor housing.

- Injection Molding Machine: Standard industrial machine.

- Simulation Software: Moldflow or equivalent for generating the training dataset.

- Computing Environment: Python/R/Matlab for running the optimization algorithms.

- Procedure:

- Design of Experiments (DOE): Utilize a Central Composite Face (CCF) design to vary key process parameters methodically. The variables typically include melt temperature, injection pressure, packing pressure, packing time, and cooling time. This design efficiently explores the design space with a manageable number of simulation runs.

- Data Generation: For each combination of parameters in the DOE, run a Moldflow simulation to compute the corresponding responses: warpage and volumetric shrinkage.

- Surrogate Model Development: Train an eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model using the dataset from steps 1 and 2. The process parameters are the model inputs, and the warpage and shrinkage are the outputs. The model is hyperparameter-tuned using an Improved Northern Goshawk Optimization (INGO) algorithm to enhance its predictive accuracy [15].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Execute a Multi-Objective Multiverse Optimization (MOMVO) algorithm. The trained and validated INGO-XGBoost model is used as the internal fitness function to predict warpage and shrinkage for any given set of parameters, replacing the need for slow Moldflow simulations during the optimization loop.

- Pareto Front Analysis: The MOMVO algorithm outputs a Pareto front, a set of non-dominated solutions representing the best trade-offs between warpage and shrinkage.

- Optimal Solution Selection: Apply the CRITIC-TOPSIS multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method to select the single best process parameters from the Pareto front. CRITIC objectively weights the importance of each objective, and TOPSIS ranks the solutions based on their distance from an ideal point.

- Validation: The final selected parameters are validated by running a final Moldflow simulation and/or a physical production trial. The cited study reported reductions of 30.9% in warpage and 8.7% in volumetric shrinkage compared to initial settings [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section lists key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting multi-objective optimization research in process design.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Multi-Objective Optimization Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Optimization | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFD/FEA Software (e.g., Moldex3D, ANSYS) | Simulation | Provides high-fidelity data on process outcomes (flow, cooling, stress) for a given set of parameters and geometry. | Validating a WAIM process model to generate data for surrogate model training [13]. |

| ANN / XGBoost Surrogate | Machine Learning Model | Acts as a fast, approximate substitute for computationally expensive simulations during the iterative optimization process. | Replacing Moldex3D CFD runs in an NSGA-II loop to predict Hollow Core Ratio and Wall Thickness Deviation [13] [15]. |

| NSGA-II / NSGA-III | Optimization Algorithm | A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm that finds a diverse set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto front) for problems with multiple conflicting objectives. | Optimizing extrusion parameters for output rate vs. energy consumption [3]. NSGA-III is designed for many-objective problems (>3 objectives) [12]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explainable AI Tool | Interprets complex surrogate models (like XGBoost) by quantifying the contribution of each input parameter to the output predictions. | Identifying which process parameters (melt temp, pressure) most influence warpage and shrinkage in injection molding [15]. |

| PyePAL | Active Learning Library | Implements an active learning Pareto front algorithm that intelligently selects the most informative samples to evaluate next, reducing the total number of expensive simulations or experiments required. | Optimizing spin coating parameters for polymer thin films to achieve target hardness and elasticity [17]. |

The journey toward optimal process design is fundamentally a navigation of trade-offs. The core challenges of multi-objective optimization—dimensionality, conflict, computational cost, and dynamic environments—are pervasive in polymer processing and drug development. However, as detailed in this article, a robust methodological framework exists to meet these challenges. By leveraging advanced algorithms like NSGA-II and MOPSO, harnessing the power of surrogate models to overcome computational barriers, and employing structured protocols for experimentation and decision-making, researchers can effectively map the Pareto-optimal landscape. The integration of explainable AI and active learning further enhances this process, making it more efficient and interpretable. Ultimately, mastering these multi-objective optimization techniques is key to driving innovation and achieving superior, balanced outcomes in complex process design.

The optimization of polymer processing is critical in research and industrial applications, ranging from pharmaceutical development to advanced material manufacturing. While chemical composition often receives primary focus, two hidden material properties—Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) and Melt Flow Index (MFI)—exert profound influence over processing behavior and final product performance. MWD describes the statistical distribution of individual molecular chain lengths within a polymer sample, fundamentally governing mechanical strength, toughness, and thermal stability [18] [19]. MFI, conversely, is a vital rheological measurement indicating how easily a molten polymer flows under specific conditions, serving as a crucial proxy for viscosity and molecular weight that directly predicts processability in operations like injection molding, extrusion, and blow molding [20] [21] [22]. This application note details the intrinsic relationship between MWD and MFI, provides standardized protocols for their characterization, and demonstrates how their precise control and measurement are indispensable for advancing polymer processing optimization, particularly where consistent quality and performance are non-negotiable.

Quantitative Correlation Between MWD and MFI

The relationship between MWD and MFI is inverse and non-linear, governed by the underlying polymer melt viscosity. The quantitative correlations, derived from empirical and theoretical models, are summarized below.

Table 1: Fundamental Correlations Between Molecular Weight, MFI, and Polymer Properties

| Parameter | Mathematical Relationship | Key Influencing Factors | Impact on Polymer Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Shear Melt Viscosity (η₀) | η₀ = K × Mwα [23] | Average Molecular Weight (Mw), Polymer type (constants K & α) | Directly determines resistance to flow; higher η₀ means lower MFI. |

| MFI and Molecular Weight | 1 / MFI = G × Mwα [24] [23] | For Polypropylene (PP), α ≈ 3.4 [23] | Inverse correlation: High Mw leads to low MFI, and vice versa. |

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) | PDI = Mw / Mn [19] | Polymerization process (e.g., controlled vs. free-radical) | Narrow MWD (PDI ~1): More uniform properties. Broad MWD (PDI >1): Easier processing but potentially lower mechanical strength. |

Table 2: Typical MFI Ranges for Common Manufacturing Processes

| Manufacturing Process | Typical MFI Range (g/10 min) | Rationale for MFI Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Blow Molding | 0.2 - 0.8 [20] | Low MFI ensures melt strength and parison stability for uniform material distribution. |

| Extrusion | ~1 [20] | Balanced flowability for consistent, uniform output and shape retention. |

| Injection Molding | 10 - 30 [20] | High MFI enables fast flow to fill complex mold cavities efficiently. |

Diagram 1: Relationship between MWD, MFI, and polymer properties. High molecular weight and broad MWD increase melt viscosity, resulting in a low MFI, which signals both processing challenges and enhanced final product properties.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Designing and Synthesizing Tailored MWD in Flow Reactors

Principle: This protocol uses a computer-controlled tubular flow reactor to synthesize polymers with targeted MWDs by accumulating sequential plugs of narrow-MWD polymer [25]. Taylor dispersion under laminar flow conditions is harnessed to achieve a narrow residence time distribution, which is critical for producing each polymer fraction with a low dispersity [25].

Materials:

- Computer-controlled syringe pumps: For precise delivery of initiator and monomer streams.

- Tubular flow reactor: (e.g., PFA or stainless steel, dimensions: radius 0.0889–0.254 mm, length 7.6–15.2 m) [25].

- Temperature-controlled bath or oven: To maintain consistent reactor temperature.

- Collection vessel: For accumulating synthesized polymer fractions.

- Reagents: Monomer, initiator/catalyst, and solvent appropriate for the chosen polymerization chemistry (e.g., lactide for ROP, styrene for anionic polymerization) [25].

Procedure:

- Reactor Design Calculation: Based on the target MWD profile, use established reactor design rules to calculate the required sequence of flow rates (Q). The plug volume is proportional to ( R^2 \sqrt{L Q} ), where R is the reactor radius and L is the reactor length [25].

- Reactor Setup and Calibration: Set up the flow reactor system and calibrate pumps. Equilibrate the entire system to the desired reaction temperature.

- Polymer Synthesis: Initiate the flow of monomer and initiator streams according to the pre-calculated flow rate program. Each discrete flow rate produces a specific narrow-MWD polymer fraction.

- Product Collection: Collect the entire effluent from the reactor in a single vessel. Over time, the accumulated polymer builds the final, broad MWD profile.

- Purification: Isolate the polymer from the collection vessel using standard techniques (e.g., precipitation, drying).

Notes: This protocol is chemistry-agnostic and has been successfully demonstrated for ring-opening polymerization (ROP), anionic polymerization, and ring-opening metathesis polymerization [25]. The mathematical model enables a-priori prediction of the MWD based on flow rates.

Protocol for Determining the Melt Flow Index (MFI)

Principle: The MFI measures the mass of polymer extruded through a standard capillary die under specified conditions of temperature and load over 10 minutes, providing a standardized indicator of melt viscosity [20] [21] [22].

Materials:

- Melt Flow Indexer: Consisting of a temperature-controlled barrel, a calibrated capillary die, a weighted piston, and a cutting mechanism.

- Analytical Balance: Accurate to at least 0.001 g.

- Timer.

- Spatula.

- Personal protective equipment (heat-resistant gloves, safety glasses).

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Pre-heat the MFI instrument barrel to the standard temperature specified for the polymer material (e.g., 190°C for polyethylene, 230°C for polypropylene) [22]. Ensure the barrel and piston are clean.

- Sample Loading: Add a representative sample of polymer (approx. 4-5 g) into the barrel. After 60 seconds, compact the melt with the piston to remove air bubbles.

- Extrusion and Measurement: After a total preheat time of 4-6 minutes (as per standard), place the specified weight on the piston. After the piston descends to a reference mark, start the timer.

- Sample Collection: At a predetermined time (or after the piston passes a second mark), use the cutter to cleanly sever the extrudate. Collect one or more extrudate strands.

- Weighing and Calculation: Weigh the collected, cooled extrudate accurately. The MFI is calculated as the mass of extrudate in grams multiplied by 600 and divided by the measurement time in seconds, yielding the final value in g/10 min [21] [22].

[ \text{MFI} \left( \frac{g}{10 \text{ min}} \right) = \frac{\text{mass of extrudate (g)} \times 600}{\text{measurement time (s)}} ]

Notes: This test must be performed in accordance with standardized methods (e.g., ASTM D1238 or ISO 1133) to ensure reproducibility and inter-lab comparability [20] [21]. The test is a single-point measurement and may not fully capture the rheological behavior of the polymer under all processing conditions.

Diagram 2: MFI testing workflow. The protocol involves pre-heating, loading, compacting, applying weight, and extruding the polymer to determine the mass flow rate over 10 minutes according to ASTM D1238 or ISO 1133 standards.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Polymer Synthesis and Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Computer-Controlled Flow Reactor | Enables precise synthesis of polymers with targeted MWD by controlling residence time and reagent mixing [25]. |

| Melt Flow Indexer | Standard instrument for determining MFI/MFR, a critical quality control and processability metric [20] [21]. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Absolute method for determining MWD, Mn, Mw, and PDI [24] [23]. |

| Rheometer | Provides comprehensive analysis of viscosity and viscoelastic properties beyond the single-point MFI measurement [26]. |

| Lactide / Styrene Monomers | Model monomers for developing polymerization protocols (e.g., Ring-Opening Polymerization, Anionic Polymerization) [25]. |

| Flow Modifiers (e.g., avanMFI PLUS 2 PO) | Additives used to intentionally adjust the MFI of a polymer blend or recycled material to meet specific processing requirements [22]. |

A Practical Guide to Optimization Algorithms and Their Implementation

The optimization of polymer processing is of primordial practical importance given the global economic and societal significance of the plastics industry. Processing thermoplastic polymers typically involves plasticization, melt shaping, and cooling stages, each characterized by complex interactions between heat transfer, melt rheology, fluid mechanics, and morphology development [2] [27]. The selection of appropriate optimization methodologies has consequently emerged as a critical research domain for improving product quality, reducing resource consumption, and enhancing manufacturing efficiency.

Traditional trial-and-error approaches to polymer processing optimization are increasingly being replaced by systematic computational strategies that can handle multiple, often conflicting objectives [2]. These advanced methodologies are particularly valuable for addressing inverse problems in polymer engineering, where conventional simulation tools are used inefficiently to determine optimal equipment geometry and operating conditions [27]. The complexity of these optimization challenges has driven the development and application of diverse algorithmic approaches, primarily categorized as evolutionary or gradient-based methods.

This analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of optimization algorithms applied to polymer processing, with specific emphasis on their theoretical foundations, practical implementation requirements, and performance characteristics across various polymer processing applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Optimization Algorithms

Gradient-Based Optimization Methods

Gradient-based optimization methods utilize derivative information to navigate the parameter space efficiently. The fundamental principle involves iteratively moving in the direction opposite to the gradient of the objective function, which represents the steepest descent direction [28].

The classical gradient descent algorithm follows these essential steps [28]:

- Compute the gradient of the objective function at the current parameter position

- Update parameters by moving in the negative gradient direction

- Repeat until convergence criteria are met

Mathematically, the parameter update rule is expressed as:

θ_t ← θ_(t-1) - ηg_t

where g_t represents the gradient ∇_(θ_(t-1)) f(θ_(t-1)) and η is the learning rate.

Advanced gradient-based methods have evolved to address limitations of basic gradient descent. Momentum optimization incorporates information from previous iterations to accelerate convergence and overcome local minima [28]. Adaptive learning rate methods like Adagrad, RMSprop, and Adam dynamically adjust step sizes for each parameter based on historical gradient information, improving performance on problems with sparse gradients or noisy objectives [28]. Recent innovations like the MAMGD optimizer further enhance gradient methods through exponential decay and discrete second-order derivative approximations, demonstrating high convergence speed and stability with fluctuations [28].

Evolutionary Optimization Methods

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) belong to the class of population-based metaheuristic optimization methods inspired by biological evolution. Unlike gradient-based methods, EAs do not require derivative information and instead maintain a population of candidate solutions that evolve through selection, recombination (crossover), and mutation operations [2] [29].

The fundamental procedure for EAs involves [30]:

- Initialization of a random population of candidate solutions

- Evaluation of each candidate's fitness (objective function value)

- Selection of parents based on fitness

- Application of crossover and mutation to create offspring

- Formation of new population through selection mechanisms

- Repetition until termination criteria are satisfied

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) represent one of the most prominent EA variants and have been successfully applied to multi-objective optimization problems in polymer processing [29]. Other popular evolutionary approaches include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which simulates social behavior patterns, and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithms, which model the foraging behavior of honey bees [2].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Optimization

Hybrid approaches that combine machine learning with traditional optimization methods are increasingly applied to polymer processing challenges. Boosting methods, including Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM, have demonstrated particular effectiveness for tackling high-dimensional problems with complex non-linear relationships [31] [32]. These ensemble techniques build strong predictive models by combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees, and have been applied to predict polymer properties, optimize processing parameters, and design polymer formulations [31].

Bayesian Optimization provides another powerful framework for sample-efficient optimization, particularly valuable when objective function evaluations are computationally expensive [5]. This approach uses probabilistic surrogate models, typically Gaussian Processes, to guide the exploration-exploitation trade-off during optimization [5].

Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Performance

Computational Efficiency Comparison

The computational requirements of optimization algorithms vary significantly based on problem dimensionality, evaluation cost, and convergence characteristics. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for major algorithm classes:

Table 1: Computational Efficiency of Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Derivative Requirements | Memory Usage | Scalability to High Dimensions | Typical Convergence Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Descent | First-order | Low | Moderate | Linear |

| Newton Methods | Second-order | High | Challenging | Quadratic |

| Genetic Algorithm | None | High | Good | Sublinear |

| Particle Swarm | None | Moderate | Good | Sublinear |

| Simulated Annealing | None | Low | Moderate | Sublinear |

| Bayesian Optimization | None | Moderate | Limited for high dimensions | Varies |

Empirical comparisons demonstrate that for low-dimensional problems with inexpensive objective functions, gradient-based methods typically outperform evolutionary approaches in convergence speed [30]. However, as problem dimensionality increases or objective function evaluations become computationally expensive (e.g., multiphysics simulations), the relative efficiency of evolutionary algorithms improves [30].

For polymer processing applications specifically, studies indicate that Evolutionary Algorithms (EA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithms demonstrate strong performance across multiple criteria, including global optimization capability, handling of discontinuous objective spaces, and flexibility for different problem types [2].

Application-Specific Performance in Polymer Processing

The effectiveness of optimization algorithms varies significantly across different polymer processing applications. The table below synthesizes performance observations from multiple studies:

Table 2: Algorithm Performance in Polymer Processing Applications

| Processing Method | Effective Algorithms | Common Objectives | Notable Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection Molding | Gradient, EA, Regression, SA | Minimize defects, cycle time, improve quality | Gradient methods effective for gate location; EA for multi-objective [2] |

| Polymer Composite Curing | GA, NSGA-II, Bayesian Optimization | Minimize process time, residual stress, maximize degree of cure | Bayesian Optimization reduced evaluations by 10x vs traditional methods [5] |

| Extrusion Processes | EA, PSO, ABC | Output maximization, energy consumption minimization, homogeneity | PSO and ABC show excellent convergence and flexibility [2] [27] |

| Reverse Engineering of Polymerization | ML-enhanced GA | Match target properties, minimize reaction time | ML surrogate models reduced computational cost by 95% [29] |

| Functionally Graded Materials | Gradient-based, EA | Property gradient control, interfacial stress reduction | Multi-objective approaches essential for conflicting requirements [33] |

A critical consideration in polymer processing optimization is the multi-objective nature of most practical problems, which often involve competing aims such as maximizing product quality while minimizing production time and resource consumption [2]. Evolutionary algorithms, particularly NSGA-II and other multi-objective variants, have demonstrated excellent capability for identifying Pareto-optimal solutions across these complex trade-space explorations [2] [5].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Protocol 1: ML-Enhanced Evolutionary Optimization for Reverse Engineering

This protocol adapts the methodology described by [29] for reverse engineering polymerization processes to achieve target polymer properties.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protocol 1

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Monomer Systems | Butyl acrylate or other vinyl monomers | Primary reactant for polymerization |

| Initiator Systems | Thermal or photochemical initiators | Initiate radical polymerization process |

| Solvents | Appropriate for monomer system | Control viscosity, heat transfer |

| Kinetic Monte Carlo Simulator | Custom or commercial software | Generate training data for ML models |

| Machine Learning Framework | Python/TensorFlow or equivalent | Develop surrogate property predictors |

| Genetic Algorithm Library | DEAP, JMetal, or custom code | Implement multi-objective optimization |

Procedure:

- Data Generation: Perform Kinetic Monte Carlo simulations for a diverse set of polymerization recipes (monomer concentration, initiator type and concentration, temperature profiles) to generate training data encompassing a broad range of process conditions [29].

- Surrogate Model Development: Train machine learning models (e.g., gradient boosting, neural networks) to predict polymer properties (molar mass distribution, conversion, etc.) from recipe parameters. Apply feature selection techniques (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) to identify most influential parameters [34].

- Optimization Problem Formulation: Define multi-objective optimization problem with targets such as reaction time minimization, monomer conversion maximization, and molar mass distribution similarity to desired targets [29].

- Genetic Algorithm Implementation: Configure GA with appropriate population size (typically 50-100), selection, crossover, and mutation operators. Utilize ML surrogate models for fitness evaluation to reduce computational cost [29].

- Pareto Front Analysis: Execute optimization runs until Pareto front convergence, then select optimal recipes based on application-specific priorities using decision-making methods [29].

Validation: Validate optimal recipes identified through optimization with full Kinetic Monte Carlo simulations or limited laboratory experiments to confirm performance [29].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Composite Cure Cycle Design

This protocol implements the Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) approach described by [5] for designing efficient cure cycles for thermoset polymer composites.

Procedure:

- Multiscale Model Setup: Establish finite element models capturing cure kinetics at both macro-structural and representative volume element scales, incorporating heat transfer, resin flow, and cure-induced stress development [5].

- Gaussian Process Prior Definition: Initialize Gaussian Process surrogate models for each objective function (total process time, transverse residual stress, degree of cure) with appropriate kernel functions based on expected response surfaces [5].

- Acquisition Function Selection: Implement q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-EHVI) as acquisition function to efficiently explore the multi-objective Pareto front without requiring scalarization [5].

- Iterative Optimization Loop: a. Evaluate initial design points (cure temperature, hold times, ramp rates) using high-fidelity FEA b. Update Gaussian Process surrogates with simulation results c. Select next evaluation points by maximizing acquisition function d. Run FEA at selected points and update data set e. Repeat until convergence or evaluation budget exhaustion [5]

- Pareto Solution Selection: Identify optimal cure cycle parameters from the final Pareto front based on application priorities (e.g., production throughput vs. product quality).

Validation: Compare optimized cure cycles against Manufacturer Recommended Cure Cycles (MRCC) for performance metrics including total process time, residual stress distribution, and degree of cure uniformity [5].

Visualization of Algorithm Workflows and Relationships

Algorithm Selection Framework for Polymer Processing

ML-Enhanced Evolutionary Optimization Workflow

The comparative analysis of optimization algorithms for polymer processing reveals a complex landscape where no single approach dominates across all application scenarios. Gradient-based methods offer computational efficiency for problems with available derivative information and well-behaved objective functions, while evolutionary algorithms provide robust global optimization capability for multi-objective problems with discontinuous or noisy response surfaces [2] [30].

The emerging trend toward hybrid methodologies that combine machine learning surrogate modeling with traditional optimization frameworks represents a promising direction for addressing the computationally intensive nature of polymer process simulation [29] [5]. These approaches leverage the sample efficiency of Bayesian optimization or the predictive power of boosting algorithms to reduce the number of expensive function evaluations required for convergence [31] [5] [32].

Selection of an appropriate optimization strategy must consider multiple factors including problem dimensionality, evaluation cost, objective function characteristics, and computational resources. The protocols and decision frameworks presented in this analysis provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these methods in diverse polymer processing applications, from reaction engineering to composite manufacturing.

Polymeric materials are integral to numerous applications, from medical devices to automotive parts, yet their design and processing have traditionally relied on empirical methods and time-consuming trial-and-error experiments [35]. The intrinsic complexity of polymer systems, characterized by multi-scale behaviors and non-linear dynamics, presents significant challenges for conventional modeling approaches. The emergence of data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming this landscape. By leveraging artificial neural networks (ANNs) and other ML algorithms, researchers can now accelerate material discovery, predict complex property relationships, and optimize manufacturing processes with unprecedented efficiency [35] [36]. This document provides application notes and detailed experimental protocols for implementing these advanced computational techniques within polymer processing optimization research.

Core Machine Learning Approaches and Their Quantitative Performance

The application of ML in polymer science encompasses several distinct methodologies, each with specific strengths. The table below summarizes the primary approaches and their reported performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance of Key Machine Learning Approaches in Polymer Science

| ML Approach | Primary Application Area | Reported Performance / Outcome | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-in-the-Loop RL [37] | Design of tough, 3D-printable elastomers | Created polymers 4x tougher than standard counterparts | Combines AI exploration with human expertise for inverse design |

| ANN for Fatigue Prediction [38] | Predicting fatigue life of fiber composites | High predictive quality with as few as 92 training data points | Effective with small datasets; no prior mechanistic model needed |

| Closed-Loop AI Optimization [1] | Polymer process control in manufacturing | >2% reduction in off-spec production; 10-20% reduction in energy consumption | Real-time setpoint adjustment for quality and energy savings |

| Physics-Informed NN (PINN) [39] | Polymer property prediction & process optimization | Integrates physical laws (PDEs) directly into the loss function | Data efficiency; ensures predictions are physically consistent |

| ANN for Biosensors [40] | Modeling catalytic activity of polymer-enzyme biosensors | Pearson's ρ: 0.9980; MSE: 3.0736 × 10⁻⁵ | Excellent interpolatory capacity for predicting sensor response |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Human-in-the-Loop RL for Inverse Material Design

This protocol outlines the procedure for designing elastomers with enhanced mechanical properties, such as high toughness, using a collaborative human-AI workflow [37].

3.1.1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Human-in-the-Loop Elastomer Design

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix | Base material for the elastomer system. | Polyacrylate [41]. |

| Candidate Crosslinkers | Molecules that form weak, force-responsive links in the polymer network. | Ferrocene-based mechanophores like m-TMS-Fc [41]. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | For high-throughput robotic synthesis of proposed compositions. | Automated science tools for rapid iteration [37]. |

| Mechanical Tester | To quantitatively measure the properties of synthesized materials. | For measuring tear strength and resilience [41]. |

3.1.2. Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of human-in-the-loop reinforcement learning for material design.

3.1.3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Problem Formulation: Clearly define the target property or multi-objective portfolio (e.g., maximize toughness while maintaining flexibility) [37].

- Initialization: The ML model is provided with a database of known polymer structures and properties to establish a baseline understanding.

- AI Suggestion: The model proposes a new chemical formulation or structure (e.g., a specific ferrocene crosslinker) expected to improve the target properties [41].

- Human Execution & Analysis: Expert chemists synthesize the proposed material using automated platforms and characterize its properties through standardized mechanical testing [37].

- Feedback Loop: The experimental results (success or failure) are fed back to the ML model as new training data.

- Iteration: The model updates its internal logic and suggests a refined experiment. This human-AI iterative cycle continues until the performance targets are met [37].

Protocol: ANN for Predictive Modeling of Composite Properties

This protocol details the use of Artificial Neural Networks to predict complex properties of polymer composites, such as fatigue life or wear performance, from compositional and processing data [38].

3.2.1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for ANN Predictive Modeling of Composites

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix | The continuous phase of the composite. | Epoxy, polypropylene, etc. |

| Fillers/Reinforcements | Discontinuous phase added to modify properties. | Short glass, aramid, or carbon fibers; PTFE, graphite lubricants [38]. |

| Standardized Testing Equipment | To generate high-quality training and validation data. | Fatigue testing machines, wear testers, dynamic mechanical analyzers (DMA). |

| Computational Software | Platform for building and training the ANN. | Python (with libraries like TensorFlow or PyTorch), MATLAB. |

3.2.2. Workflow Diagram

The workflow for developing an ANN predictive model for composite properties is as follows.

3.2.3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Collection: Compile a comprehensive dataset from historical experiments or literature. Critical parameters include matrix/filler types, composition ratios, processing conditions (e.g., curing temperature), and the resulting measured properties [38].

- Preprocessing: Clean the data (handle missing values, outliers) and normalize the input and output variables to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1) to ensure stable ANN training.

- Network Architecture Design: Choose the number of hidden layers and neurons per layer. Start with a simple architecture (e.g., 1-2 hidden layers) and increase complexity if needed. Select appropriate activation functions (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid) [38] [40].

- Model Training: Split the data into training, validation, and test sets. Use the training set to adjust the ANN's weights via backpropagation, typically using an optimization algorithm like Adam. The validation set is used to tune hyperparameters and prevent overfitting.

- Performance Validation: Evaluate the trained model on the unseen test set using metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) or Pearson's correlation coefficient (ρ) [40]. The model is ready for deployment only when prediction accuracy meets the required threshold.

- Deployment and Prediction: Use the validated ANN to predict the properties of new, untested composite formulations, thereby guiding the design process and reducing the need for extensive experimentation [38].

Protocol: Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for Multi-Scale Modeling

PINNs address the challenge of modeling polymer behavior across different scales (atomistic to macroscopic) by embedding physical laws directly into the learning process [39] [36].

3.3.1. Workflow Diagram

The architecture and workflow of a PINN for solving a polymer-related PDE is detailed below.

3.3.2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Define the Physical System: Formulate the problem using governing Partial Differential Equations (PDEs),

N(u(x,t)) = f(x,t), which describe the physics of the system (e.g., stress evolution, heat transfer, diffusion) [39]. - Construct the Hybrid Loss Function: The total loss function

(L)is defined as a weighted sum of:L_data: The error between model predictions and sparse experimental data.L_physics: The residual of the governing PDE, ensuring the solution satisfies physical laws.L_BC: The error in satisfying the boundary and initial conditions [39].

- Network Training: The PINN is trained by minimizing the total loss

L. The gradients of the outputuwith respect to the inputs(x, t)required forL_physicsare computed using automatic differentiation. - Solution and Analysis: Once trained, the PINN provides a functional approximation of the solution

u(x,t)that inherently respects the underlying physics, making it particularly useful for problems with sparse or noisy data [39] [36].

The integration of machine learning and artificial neural networks into polymer science marks a paradigm shift from intuition-based discovery to data-driven, predictive design. The protocols outlined herein—from human-in-the-loop reinforcement learning for inverse design to ANNs for property prediction and PINNs for multi-scale modeling—provide a robust toolkit for researchers. By adopting these approaches, scientists can significantly accelerate the development of advanced polymeric materials, optimize complex manufacturing processes, and ultimately push the boundaries of what is possible in fields ranging from medical devices to sustainable packaging. Future progress will hinge on the development of larger, shared polymer datasets, improved model interpretability, and the tighter integration of AI into automated laboratory workflows [36].