Advanced Strategies for Reducing Viscosity Issues in Polymer Melts: From Molecular Design to Process Control

This article provides a comprehensive overview of innovative strategies to mitigate viscosity-related challenges in polymer melts, a critical issue affecting processing efficiency and final product quality.

Advanced Strategies for Reducing Viscosity Issues in Polymer Melts: From Molecular Design to Process Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of innovative strategies to mitigate viscosity-related challenges in polymer melts, a critical issue affecting processing efficiency and final product quality. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies, practical troubleshooting techniques, and robust validation frameworks. By exploring the integration of explainable AI, high-throughput molecular dynamics, real-time soft sensors, and advanced rheological analysis, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to optimize polymer processing, reduce material waste, and accelerate the development of high-performance materials for biomedical and clinical applications.

Understanding the Root Causes of Polymer Melt Viscosity

The Fundamentals of Polymer Viscoelasticity and Flow

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers investigating viscosity reduction in polymer melts. High melt viscosity presents significant challenges in industrial and pharmaceutical processing, leading to increased energy consumption, difficulty in achieving uniform mixing, and limitations in using advanced manufacturing techniques. This resource synthesizes current research and established methodologies to help scientists diagnose, understand, and resolve common flow-related issues encountered during experiments, with a specific focus on strategies for effective viscosity reduction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is viscoelasticity and why is it critical in polymer melt processing?

Viscoelasticity describes the dual nature of polymers, which exhibit both viscous, liquid-like flow and elastic, solid-like recovery when deformed [1]. This time-dependent response to applied stress or strain is fundamental to polymer processing. During flow, strain energy is partially stored (elastic component) and partially dissipated as heat (viscous component) [1]. Understanding this balance is crucial because the elastic component can cause undesirable effects like die swell in extrusion, while the viscous component dictates the flow resistance and energy required for processing.

Q2: My polymer melt viscosity is too high for processing. What are proven methods to reduce it?

Several strategies exist to lower melt viscosity, each with distinct mechanisms and applications. The choice depends on your material system and process constraints.

- Thermal Modification: Increasing temperature is a common method, as higher temperatures create larger free volume between polymer chains, allowing them to move more easily and reducing viscosity [2]. This is often modeled using the Arrhenius equation.

- Mechanical Shearing: Applying higher shear rates during processing can disentangle polymer chains, leading to shear-thinning behavior and lower effective viscosity during the process itself [1] [2].

- Chemical Plasticization: Adding miscible low-molecular-weight substances, such as certain drugs or plasticizers, can separate polymer chains and increase their mobility, resulting in a plasticizing effect that lowers viscosity [2].

- Supercritical Fluid Addition: Introducing supercritical carbon dioxide (scCOâ‚‚) into a polymer melt acts as a physical plasticizer, significantly reducing viscosity without the need for high thermal loads [3].

- Nanoparticle Additives: Recent research shows that incorporating specific nanoparticle geometries, such as nanotetrapods, can introduce packing frustration in the polymer matrix, enhancing chain mobility and reducing composite viscosity without compromising mechanical properties [4].

Q3: Why does my polymer's viscosity change between material lots, and how can I manage this?

Variations in viscosity between lots of the same polymer are common and often stem from differences in molecular weight distribution or thermal history. The Melt Flow Index (MFI) is a key indicator provided by material suppliers. It's crucial to note that a single "12 melt" material can have an MFI tolerance range as large as 7 to 15 percent, leading to a potential viscosity shift of up to 20% between lots [5]. To manage this, always check the vendor's certification for the MFI of your specific lot and adjust your processing parameters (e.g., temperature, injection pressure) accordingly. Implementing in-process viscosity monitoring can provide real-time alerts to these variations.

Q4: How can I experimentally distinguish between a plasticizing effect and a filler effect from an additive?

The effect of an additive on viscosity is determined by its miscibility with the polymer and its concentration, as summarized in the table below.

Table: Distinguishing Plasticizing and Filler Effects in Polymer Mixtures

| Effect Type | Cause | Impact on Viscosity | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasticizing | Additive is miscible and dissolves in the polymer [2]. | Decreases viscosity [2]. | Low to moderate, within solubility limit. |

| Filler | Additive is immiscible or exceeds its solubility in the polymer [2]. | Increases viscosity [2]. | Moderate to high, above solubility limit. |

A single additive can exhibit both effects simultaneously. At concentrations below its solubility limit, it acts as a plasticizer, reducing viscosity. Any concentration exceeding the solubility limit will result in a suspended, immiscible fraction that acts as a filler, increasing viscosity [2]. Techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) or rheology can be used to determine the solubility limit.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Viscosity Measurements

Symptoms: High variability in repeated measurements; data does not fit expected models (e.g., Carreau, Power-Law).

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Check Sample Preparation: For powdered pharmaceuticals and polymers, sample preparation is critical for reproducibility. Ensure a consistent and homogeneous mixing protocol [2].

- Verify Instrument Calibration and Selection: Confirm your rheometer is calibrated. Choose the appropriate measurement geometry (e.g., cone-plate, parallel plate). Be aware that rotational rheometers have a limited shear rate range (typically 10â»Â²â€“10² sâ»Â¹) and high shear rates can cause the gap to empty, leading to erroneous data [2].

- Confirm the Linear Viscoelastic Region: Perform a strain sweep before oscillatory measurements to ensure you are working within the material's linear viscoelastic region, where the microstructure is not destroyed by the deformation.

Problem 2: Unexpected Viscosity Increase with Nanoparticle Additives

Symptoms: Adding nanoparticles (NPs) to a polymer matrix results in a higher-than-expected viscosity, or even causes gelation, making processing more difficult.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Assess NP Dispersion: A common cause is nanoparticle aggregation or poor dispersion, which creates flow obstacles and dramatically increases viscosity [4]. Improve nanoparticle surface functionalization to enhance compatibility with the polymer matrix.

- Evaluate NP Geometry: Spherical (SN) and rod-like (NR) nanoparticles typically increase viscosity at low loadings [4]. Consider switching to architecturally complex nanoparticles like nanotetrapods (TPs), which have been shown to reduce polymer melt viscosity by introducing polymer packing frustration [4].

- Optimize NP Loading: Viscosity increases monotonically with concentration for most NP shapes. Re-evaluate the optimal loading level for your application.

Problem 3: Polymer Degradation During Melt Processing

Symptoms: Viscosity drops unexpectedly during processing; parts have reduced mechanical strength and may exhibit flash.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Identify Degradation Mechanism: Polymer chain degradation (chain scission) reduces molecular weight and, consequently, viscosity [5]. This can be caused by excessive barrel temperatures, over-drying, prolonged exposure to UV light, or chemical contaminants [5].

- Monitor Viscosity In-Process: Track a proxy for viscosity, such as the product of fill time and injection pressure at transfer. A sudden drop in this value indicates likely degradation [5].

- Use a Melt Flow Indexer: Compare the MFI of your raw material with the MFI of plastic processed through your equipment. An increase in MFI (meaning lower viscosity) confirms degradation has occurred [5]. Review and moderate your thermal history and drying parameters.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Oscillatory Rheometry for Viscoelastic Characterization

This protocol is fundamental for characterizing the viscoelastic properties of polymer melts.

- Sample Loading: Place a homogeneous sample between the pre-heated plates of a rotational/oscillatory rheometer. Ensure the sample completely fills the gap and trim excess material.

- Temperature Equilibration: Allow the sample to equilibrate at the desired test temperature for a specified time to ensure thermal uniformity.

- Strain Sweep: At a fixed frequency, perform a strain sweep to determine the maximum strain value within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) of the material.

- Frequency Sweep: Conduct a frequency sweep at a strain within the LVR. This measures the material's response across different timescales.

- Data Collection: Record the Storage Modulus (G'), which represents the elastic, solid-like component where energy is stored; the Loss Modulus (G"), which represents the viscous, liquid-like component where energy is dissipated; and the Complex Viscosity (η*) [2]. The damping factor, tan δ = G"/G', indicates whether the material is more liquid-like (tan δ > 1) or solid-like (tan δ < 1) [1].

Protocol 2: Modeling Viscosity as a Function of Shear Rate, Temperature, and Composition

This advanced protocol allows for the creation of a unified model to predict viscosity under various conditions, which is essential for process optimization [2].

- Experimental Design: Systematically vary shear rate, temperature, and drug/additive fraction in your formulations.

- Rheological Measurement: Use an oscillatory rheometer to measure the complex viscosity for each combination of parameters.

- Shear Rate Modeling: Fit the viscosity-shear rate data at a constant temperature and composition to the Carreau model to capture shear-thinning behavior [2].

- Temperature Modeling: Model the temperature dependence of the zero-shear viscosity using the Arrhenius equation (for temperatures well above Tg) or the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation (for temperatures near Tg) [1] [2].

- Composition Modeling: For drug/polymer mixtures, model the change in viscosity as a function of drug fraction using a drug shift factor. This factor can be based on the viscosity ratio or correlated to changes in the glass transition temperature (Tg) [2].

- Model Integration: Combine the individual models for shear rate, temperature, and composition into a universal predictive model.

Table: Common Models for Describing Polymer Melt Viscosity

| Model | Purpose | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Carreau Model | Describes shear-thinning behavior, showing the transition from Newtonian plateau to power-law decay [2]. | Modeling viscosity as a function of shear rate. |

| Arrhenius Equation | Captures the exponential increase in viscosity with decreasing temperature, suitable for T >> Tg [2]. | Modeling the temperature dependence of viscosity. |

| WLF Equation | Characterizes the non-linear increase in viscosity as the material approaches its glass transition temperature (Tg) [1] [2]. | Modeling temperature dependence near Tg. |

| Drug Shift Factor | A proposed factor to model the change in a polymer's viscosity as a function of the fraction of a miscible drug additive [2]. | Predicting viscosity of drug-polymer mixtures. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Polymer Melt Viscosity Research

| Material / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Polymers (e.g., Eudragit EPO, Soluplus, Plasdone S-630) | These are common polymeric carriers used as model excipients in hot melt extrusion and pharmaceutical research, providing a broad spectrum of properties [2]. |

| Model Drugs (e.g., Acetaminophen, Itraconazole, Griseofulvin) | These well-studied drugs are used to investigate drug-polymer interactions, miscibility, and their resulting plasticizing or filler effects on viscosity [2]. |

| Nanoparticles (CdSe Spheres, Rods, Tetrapods) | Additives of different geometries used to study and manipulate polymer dynamics. Tetrapods have been shown to reduce composite viscosity via confinement-induced packing frustration [4]. |

| Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (scCOâ‚‚) | A physical plasticizer that can be injected into a polymer melt during processing to achieve a substantial drop in viscosity, facilitating the processing of high-viscosity materials [3]. |

| Calcium Carbonate (CaCO₃) | A material with a defined particle size used as an immiscible additive to study the classic "filler effect," where suspended particles increase the viscosity of the composite [2]. |

| Salirasib | Salirasib, CAS:162520-00-5, MF:C22H30O2S, MW:358.5 g/mol |

| SD-208 | SD-208, CAS:627536-09-8, MF:C17H10ClFN6, MW:352.8 g/mol |

FAQs: Troubleshooting High Melt Viscosity

1. Why is the viscosity of my polymer melt so high, and how can I reduce it for processing? High melt viscosity typically results from a combination of high molecular weight, low processing temperature, or low shear rate. The viscosity (η) of polymer melts follows distinct physical relationships with these parameters [6]:

- Molecular Weight (Mw): A critical factor exists at the entanglement molecular weight (Me). Below Me, viscosity depends on Mw. Above Me, viscosity increases much more steeply, proportional to approximately Mw^3.4 [6] [7]. Using a polymer with a molecular weight below Me can drastically reduce viscosity.

- Temperature (T): Viscosity decreases exponentially with increasing temperature. This relationship is often described by the Arrhenius model or the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) model for temperatures near the glass transition [8].

- Shear Rate (ð›¾Ì‡): Most polymer melts are shear-thinning, meaning their viscosity decreases as the shear rate increases [9] [8].

Solution Strategies:

- Optimize Molecular Weight: Select or synthesize a polymer with a lower Mw, ideally below its Me, for a dramatic reduction in zero-shear viscosity [10] [7].

- Increase Processing Temperature: Raising the melt temperature is an effective way to reduce viscosity. Always balance this against the risk of polymer degradation [8].

- Operate at Higher Shear Rates: Design your process (e.g., extrusion, injection molding) to utilize higher shear rates to take advantage of shear-thinning behavior [9].

2. My polymer melt viscosity is unpredictable when I add a drug or filler. What is happening? The introduction of a second component, such as a drug in pharmaceutical development or nanotubes in composites, can have two opposing effects [8]:

- Plasticizing Effect: If the additive is miscible with the polymer, it can increase the free volume between polymer chains, allowing them to move more easily. This decreases the melt viscosity.

- Filler Effect: If the additive is immiscible or exceeds its solubility limit in the polymer, it acts as a physical obstacle to flow. This increases the melt viscosity.

Solution Strategies:

- Characterize Miscibility: Use techniques like DSC to determine the solubility of the additive in the polymer matrix [8].

- Model the Effect: For miscible systems, use a drug shift factor to model the plasticizing effect. For immiscible systems, models like Einstein's or Maron and Pierce can predict the viscosity increase based on the volume fraction of the filler [8].

3. How can I accurately measure viscosity at the high shear rates relevant to my process? Conventional rheometers (e.g., parallel plate) often measure at low shear rates (0.01–100 sâ»Â¹), while industrial processes like injection molding occur at much higher shear rates (100–100,000 sâ»Â¹) [11]. This creates a data gap.

Solution Strategies:

- Use a Capillary Rheometer: This instrument is designed to measure viscosity at high shear rates (e.g., 50–5000 sâ»Â¹ and beyond) by forcing the melt through a small die, simulating conditions in an extruder or injection molding machine [11].

- Apply Rheological Models: Fit your low-shear-rate data to a model like Carreau or Cross, which can accurately extrapolate to predict viscosity behavior at higher, unmeasured shear rates [11] [8].

4. Are there novel material strategies to reduce viscosity without compromising mechanical properties? Yes, overcoming the classic "trilemma" where increasing strength often leads to increased brittleness and higher melt viscosity is an active area of research. One promising strategy is the use of soft nanoparticles [12].

- Mechanism: When blended into a polymer, deformable nanoparticles can act as a lubricant, helping polymer chains disentangle more rapidly during flow, thereby reducing melt viscosity. Simultaneously, during deformation, these nanoparticles can move and form crossties between fibrils, increasing toughness and strength [12].

- Outcome: This approach can break the traditional trilemma, offering a path to materials that are strong, tough, and easy to process [12].

Data Tables: Key Viscosity Relationships

Table 1: Effect of Molecular Weight (Mw) on Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀)

| Molecular Weight Regime | Governing Power Law | Practical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Unentangled (Mw < Me) | η₀ ∠Mw¹ | Viscosity increases linearly with molecular weight. |

| Entangled (Mw > Me) | η₀ ∠Mw³˙ⴠ| Viscosity increases dramatically; small Mw changes have large effects [6]. |

Table 2: Common Models for Predicting Melt Viscosity

| Model Name | Governs | Equation | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carreau / Cross | Shear Rate (ð›¾Ì‡) | η = η₀ / [1 + (λð›¾Ì‡)^ᵃ]^(ᵇ) | Models shear-thinning; smooth transition from Newtonian plateau to power-law region [11] [8]. |

| Arrhenius | Temperature (T) | η ∠exp(Eâ‚/RT) | Accurate for temperatures significantly above Tg [8]. |

| Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) | Temperature (T) | log(η/ηᵣ) = [-Câ‚(T-Táµ£)] / [Câ‚‚ + (T-Táµ£)] | More accurate than Arrhenius near the glass transition temperature (Tg) [8]. |

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Viscosity Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Viscosity is too high for extrusion | Mw too high; T too low; ð›¾Ì‡ too low | Perform SEC/GPC for Mw; run temperature sweep on rheometer. |

| Viscosity is inconsistent between batches | Variations in Mw or PDI from synthesis | Characterize Mw/PDI of all batches; check for moisture content. |

| Unexpected viscosity change with additive | Additive acting as plasticizer or filler | Conduct DSC to check miscibility; run rheology at different additive loadings [8]. |

| Viscosity measurements are noisy or irreproducible | Sample degradation or poor thermal equilibrium in rheometer | Perform TGA to check thermal stability; ensure adequate equilibration time in rheometer. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Full Viscosity Flow Curve with a Capillary Rheometer This protocol is essential for characterizing viscosity across the wide range of shear rates encountered in processing [11].

- Sample Preparation: For pelletized materials, dry according to manufacturer specifications. For powders, compress into pre-formed rods.

- Instrument Setup: Install a capillary die with a specific length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio (e.g., 20:1) and a matching, larger diameter reservoir. Select the appropriate pressure transducer.

- Bagley Correction: Perform a series of experiments at a constant temperature and shear rate, but using at least two capillaries with the same diameter but different L/D ratios. This corrects for entrance and exit pressure losses.

- Shear Rate Sweep: At a fixed temperature, measure the pressure drop (ΔP) and volumetric flow rate (Q) across a series of piston speeds. Repeat for all relevant temperatures.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the apparent shear stress (Ï„app) and apparent shear rate (ð›¾Ì‡app).

- Apply the Bagley correction to find the true wall shear stress.

- Apply the Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch correction to find the true shear rate at the wall.

- Calculate true viscosity: η = (True Shear Stress) / (True Shear Rate).

- Model Fitting: Fit the corrected data to a Carreau or Cross model to obtain a mathematical description of the viscosity function.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of a Drug or Additive on Melt Viscosity This protocol helps determine if an additive acts as a plasticizer or a filler [8].

- Sample Preparation: Create homogeneous mixtures of the polymer and additive using a twin-screw extruder or solvent casting. Prepare samples with a range of additive loadings (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, 30% by weight).

- Rheological Testing: Using a rotational or oscillatory rheometer, perform a frequency sweep (or shear rate sweep) on each sample at a constant temperature. Ensure the strain is within the linear viscoelastic region.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the complex viscosity (|η*|) or dynamic viscosity (η) against frequency or shear rate for all compositions.

- Analyze the zero-shear viscosity (η₀) by identifying the Newtonian plateau at low frequencies.

- Interpretation:

- Plasticizing Effect: If η₀ decreases with increasing additive content, the additive is miscible and plasticizing.

- Filler Effect: If η₀ increases with increasing additive content, the additive is immiscible and acting as a filler.

- Combined Effect: A decrease in η₀ at low loadings followed by an increase at high loadings suggests the additive's solubility limit has been exceeded.

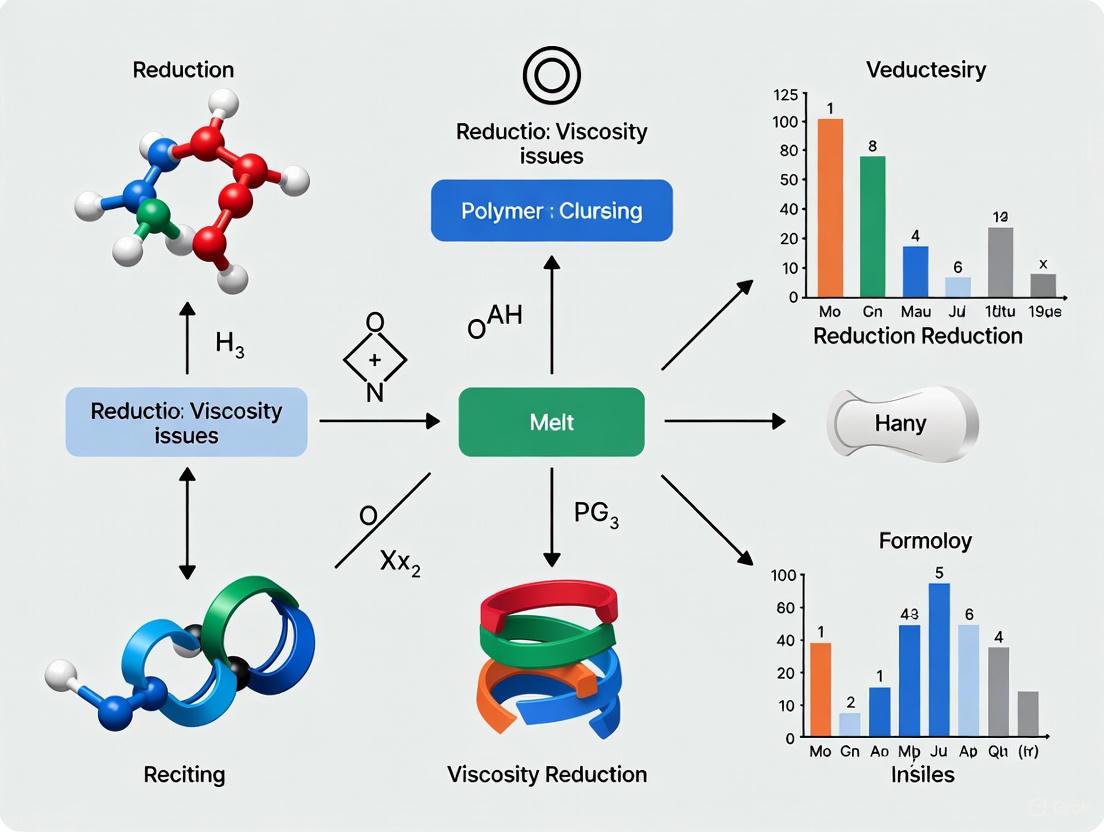

Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram Title: Decision Flow for Melt Viscosity Factors

Diagram Title: Capillary Rheometry Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Melt Viscosity Research

| Material / Reagent | Function / Rationale | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Polymer Powders/Pellets | Well-characterized reference materials for method validation and baseline studies. | Polypropylene (PP) [9], Polystyrene (PS) [7], Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) [11]. |

| Pharmaceutical-Grade Polymers | Excipients with regulatory compliance for drug product development. | Eudragit E PO, Soluplus, Plasdone S-630 [8]. |

| Model Drug Substances | Poorly soluble APIs used to study the impact of additives on rheology. | Acetaminophen (ACE), Itraconazole (ITR), Griseofulvin [8]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | High-aspect-ratio fillers for studying reinforcement and composite rheology. | Creating conductive composites; studying filler effects on viscosity [11]. |

| Soft Nanoparticles | Additives designed to break the strength-toughness-processability trilemma. | Reducing melt viscosity while enhancing mechanical properties [12]. |

| Chain Limiter (e.g., Phthalic Anhydride) | Controls molecular weight during synthesis by terminating chain growth. | Synthesizing polyimide R-BAPB with specific, targeted molecular weights [10]. |

| Semagacestat | Semagacestat|γ-Secretase Inhibitor|For Research Use | Semagacestat is a potent γ-secretase inhibitor that reduces Aβ peptides. For research applications only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Siguazodan | Siguazodan, CAS:115344-47-3, MF:C14H16N6O, MW:284.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Identifying Common Viscosity-Related Defects in Processing

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common viscosity-related defects in polymer processing, and how can I identify them?

The most common viscosity-related defects are melt fracture, void formation, and viscous heating. The table below summarizes their key characteristics, causes, and identification methods.

| Defect | Key Identifying Characteristics | Primary Viscosity-Related Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Melt Fracture [13] | Surface distortions like sharkskin (fine ripples), washboard patterns, or gross irregular distortions on the extrudate. | High shear stress from processing high-viscosity polymers at excessive speeds. |

| Void Formation [14] [15] [16] | Internal pores or bubbles that weaken mechanical properties; detectable via X-ray micro-CT scanning [15]. | High melt viscosity impedes powder coalescence and traps air [16]; poor binder-particle compatibility leads to dewetting [14]. |

| Viscous Heating [17] | Shifts in retention time, loss of resolution, and poor reproducibility in chromatography; caused by temperature gradients from frictional heating. | High flow rates with viscous mobile phases through narrow-bore columns generate excessive frictional heat [17]. |

Q2: How can I troubleshoot and resolve melt fracture in extrusion processes?

Melt fracture is a direct consequence of viscoelastic instability and can be systematically addressed [13].

- Reduce Extrusion Rate: Lowering the screw speed is the most direct way to decrease shear stress and eliminate flow instabilities [13].

- Optimize Temperature: Increase the die temperature to lower the polymer melt's viscosity, promoting smoother flow. Ensure temperatures remain below the polymer's degradation point [13].

- Modify Die Design: Use dies with streamlined, gradual transitions and adequate land lengths to stabilize polymer flow and prevent instability [13].

- Adjust Material Properties: Switch to a polymer with a lower molecular weight or a narrower molecular weight distribution, which reduces melt elasticity and susceptibility to fracture [13].

- Use Processing Aids: Incorporate additives, such as fluoropolymers, which act as lubricants to reduce surface friction within the die [13].

Q3: What experimental protocol can I use to characterize polymer solution viscosity for process optimization?

Accurate viscosity measurement is crucial for predicting and optimizing processing behavior. The following protocol, based on rotational rheometry, is detailed in [18].

Objective: To determine the intrinsic viscosity [η] and flow behavior of a polymer solution.

Materials and Equipment:

- Stress-controlled rotational rheometer (e.g., TA Instruments Discovery HR-30) [18]

- Double Wall Concentric Cylinder geometry (to minimize artifacts for low-viscosity solutions) [18]

- Polymer sample (e.g., 600 kDa Polyethylene Oxide, PEO) [18]

- Solvent (e.g., Deionized Water) [18]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of at least 4-5 dilute polymer solutions in a solvent, with concentrations ranging from, for example, 0.1 wt% to 0.8 wt% [18].

- Instrument Setup: Equip the rheometer with the concentric cylinder geometry and a solvent trap to prevent evaporation. Set the temperature to a precise, constant value (e.g., 25°C) [18].

- Steady-State Flow Sweep: For each solution and the pure solvent, perform a steady-state flow sweep, measuring the viscosity over a range of shear rates (e.g., 0.1 to 1000 sâ»Â¹) [18].

- Data Fitting: Fit the resulting flow curve for each solution to the Cross model (Equation 1) to extract the zero-shear viscosity, η₀. This value represents the viscosity at rest, free from shear-thinning effects, and is critical for intrinsic viscosity calculation [18].

- Calculate Intrinsic Viscosity:

- Calculate the relative viscosity, η_rel = η₀(solution) / η₀(solvent) for each concentration [18].

- Calculate the reduced viscosity, ηred = (ηrel - 1) / concentration and the inherent viscosity, ηinh = ln(ηrel) / concentration [18].

- Plot both

η_redandη_inhagainst concentration and perform linear regression using the Huggins and Kraemer models, respectively [18]. - The intrinsic viscosity

[η]is the Y-intercept where these two linear fits converge [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for researching and mitigating viscosity-related defects.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viscosity Research |

|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Blends [16] | Blending high and low molecular weight polymers (e.g., Polypropylene) creates a feedstock with optimized viscosity, enhancing coalescence in Powder Bed Fusion and reducing void content [16]. |

| Fluoropolymer Process Aids [13] [19] | These additives reduce die build-up and melt fracture by lowering friction at the polymer-die interface during extrusion [13] [19]. |

| Epoxy-Modified Acrylic Polymer [20] | Acts as a viscosity-reducing agent (viscosity breaker) for heavy oils via emulsification, demonstrating a principle applicable to modifying polymer melt flow [20]. |

| Surface-Functionalized Particles [14] | Modifying particle surfaces (e.g., with bonding agents) improves chemical compatibility with the polymer binder, reducing interfacial void formation in highly filled composites [14]. |

| Sulfaclozine | Sulfaclozine, CAS:102-65-8, MF:C10H9ClN4O2S, MW:284.72 g/mol |

| Skimmianine | Skimmianine, CAS:83-95-4, MF:C14H13NO4, MW:259.26 g/mol |

Experimental Workflows and Defect Pathways

Melt Fracture Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic, decision-tree approach to troubleshooting melt fracture, based on extrusion best practices [13].

Viscosity-Related Defect Formation Pathways

This diagram illustrates the cause-and-effect relationships leading from high viscosity to common processing defects [14] [13] [17].

The Impact of Polymer Chemistry and Chain Entanglements

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental relationship between polymer chain entanglement and viscosity? Polymer chain entanglement is a key regulator of viscosity in polymer melts and solutions. When polymer chains are short and/or stiff, they do not tangle significantly, leading to low-viscosity materials that are easy to process but often weak. However, once molecular weight exceeds a critical value (Mc), chains begin to entangle, dramatically increasing melt viscosity. In the entangled regime, viscosity increases with molecular weight to the power of approximately 3.4, creating much stronger materials but making them more difficult to process [21].

FAQ 2: What is "melt fracture" and how is it related to chain entanglements? Melt fracture is a flow instability occurring when entangled polymer melts are forced through a die at high rates, causing surface defects like sharkskinning or gross distortion. It arises from the viscoelastic nature of polymers; highly entangled, high molecular weight chains are more elastic and prone to these instabilities under high shear stress [13].

FAQ 3: How can I quantitatively determine if my polymer is entangled? Entanglement is determined by a polymer's critical molecular weight (Mc). Each polymer has a unique Mc, which can be found experimentally. A polymer is considered entangled if its molecular weight is greater than Mc. Below Mc, viscosity increases linearly with molecular weight. Above Mc, viscosity scales with Mw^3.4 [21]. The following table provides Mc values for common polymers:

| Polymer | Critical Entanglement Molecular Weight (Mc) | Notes on Typical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate (PC) | Low Mc | High toughness even at modest molecular weights [21]. |

| Polyisobutylene (PIB) | ~17,000 | [21] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | ~24,900 | [21] |

| Polyvinyl acetate (PVA) | ~24,900 | [21] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | ~38,000 | Low toughness, can snap easily [21]. |

| Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) | ~29,600 | Low toughness, can snap easily [21]. |

FAQ 4: What is the Melt Flow Index (MFI) and what does it tell me about my material? The Melt Flow Index (MFI) or Melt Flow Rate (MFR) is a standardized test (ASTM D1238, ISO 1133) that measures how easily a thermoplastic polymer flows in its melted state. It is inversely related to molecular weight and melt viscosity. A high MFI indicates a low molecular weight polymer with easy flow and lower entanglement, while a low MFI indicates a high molecular weight, highly entangled polymer with higher viscosity and greater strength [22] [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Melt Fracture in Extrusion

Melt fracture is a surface defect caused by flow instabilities of entangled polymer melts in the die [13].

- Symptoms: Rough extrudate surface, appearing as sharkskin (fine ripples), washboard patterns, or severe irregular distortions [13].

- Primary Causes and Corrective Actions:

| Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|

| Extrusion Rate Too High | Reduce the extrusion speed to lower the shear stress on the polymer melt [13]. |

| Suboptimal Die Temperature | Increase the die temperature to lower the polymer's viscosity. Ensure it remains below the polymer's degradation point [13]. |

| Poor Die Design | Inspect the die for sharp edges or short land lengths. Redesign the die with smooth, gradual transitions and longer land lengths to stabilize flow [13]. |

| Polymer Too Elastic | Switch to a polymer grade with a lower molecular weight or a narrower molecular weight distribution. Consider using processing aids (e.g., fluoropolymer additives) to reduce surface friction [13]. |

Guide 2: Managing Excessively High Viscosity

High viscosity, driven by entanglements, can lead to incomplete mold filling, high energy consumption, and degradation.

- Symptoms: High pressure in the extruder, short shots in injection molding, high motor load, and potential thermal degradation [22].

- Primary Causes and Corrective Actions:

| Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Too High | Source a polymer grade with a lower molecular weight (higher MFI) that is below the critical entanglement weight (Mc) for your application [21] [22]. |

| Operation Below Melting Point | Ensure the processing temperature is high enough to effectively disentangle chains and reduce viscosity. Verify the accuracy of temperature sensors [13]. |

| Incorrect Formulation | Incorporate plasticizers or processing aids into the formulation to lubricate polymer chains and facilitate their slippage past one another. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: Determining Melt Flow Rate (MFR) / Melt Flow Index (MFI)

Objective: To measure the flowability of a thermoplastic polymer melt under specified conditions, providing insight into its molecular weight and processability [23].

Materials:

- Melt flow index tester (extrusion plastometer)

- Analytical balance

- Polymer sample (pre-conditioned if required by standard)

- Timer

Method:

- Setup: Pre-heat the barrel of the plastometer to the temperature specified by the standard for your polymer (e.g., 190°C for polyethylene, 230°C for polypropylene).

- Loading: Add the polymer sample (typically 4-6 grams) into the barrel and allow it to melt for a set time.

- Purging: A weight is applied to the piston to push out any air bubbles. The initial extrudate is discarded.

- Measurement: Apply the standard weight (e.g., 2.16 kg, 5.00 kg) to the piston. After a clean cut, collect the extrudate for a timed interval (typically 10 minutes or adjusted to get a measurable amount).

- Weighing: Weigh the collected extrudate accurately.

- Calculation: The MFR is calculated as the mass of extrudate in grams per 10 minutes. The test is typically performed in triplicate for reliability [23].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening for Viscosity-Temperature Performance

Objective: To efficiently produce data on the viscosity-temperature performance of various polymer structures using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling machine learning-driven discovery of new materials like Viscosity Index Improvers (VIIs) [24].

Materials:

- High-performance computing cluster

- Automated workflow software (e.g., RadonPy open-source library can be a starting point)

- Molecular structure inputs (SMILES strings)

Method:

- Input Generation: Define a library of polymer structures using SMILES strings. A database uniform sampling strategy can be used for data augmentation from a small starting set [24].

- Force Field Configuration: The automated workflow assigns appropriate force field parameters for the MD simulations.

- High-Throughput MD Simulation: Run non-equilibrium MD (NEMD) simulations in a batch-processed manner to calculate shear viscosity across a range of temperatures. This step is computationally intensive but generates consistent, high-quality data [24].

- Data Aggregation & Feature Engineering: Collect simulation results into a structured dataset. Calculate high-dimensional physical features (descriptors) for each polymer.

- Model Building & Screening: Use machine learning (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) to build a predictive model. Apply the model to screen a vast virtual library of polymers for high-performance candidates, which can then be validated by direct MD simulation [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Essential materials and computational tools for research into polymer melt viscosity and chain entanglements.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Standard Thermoplastics (e.g., PE, PP, PS) | Model systems for foundational studies on the effects of molecular weight and architecture on entanglement and viscosity [21] [22]. |

| Processing Aids (e.g., Fluoropolymer Additives) | Used to modify polymer-polymer and polymer-wall friction, helping to mitigate surface melt fracture without changing the base polymer's bulk properties [13]. |

| Purge Compounds | Specialized compounds used to clean processing equipment when transitioning between polymers with different melt flows (MFI), preventing cross-contamination that could skew experimental results [22]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Enables atomic-scale simulation of polymer chain dynamics, allowing for the prediction of properties like viscosity and the direct observation of entanglement phenomena [24]. |

| Melt Flow Index Tester | Standard laboratory equipment for measuring the Melt Flow Rate (MFR) of thermoplastics, a critical quality control and material selection metric [23]. |

| SMI-16a | SMI-16a, MF:C13H13NO3S, MW:263.31 g/mol |

| SMI-4a | SMI-4a, CAS:438190-29-5, MF:C11H6F3NO2S, MW:273.23 g/mol |

For researchers working with polymer melts, controlling viscosity is not merely a processing concern but a fundamental challenge that impacts everything from product performance to manufacturing efficiency. A deep understanding of rheological principles—specifically the transition from Newtonian plateaus to shear-thinning regimes—is essential for innovating in fields ranging from drug delivery to advanced materials manufacturing. This technical resource center addresses the core challenges scientists face when aiming to reduce viscosity issues in polymer melts, providing actionable troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols grounded in current rheological science. The ability to precisely manipulate a polymer's flow behavior enables breakthroughs in processing efficiency and functional performance, making mastery of these principles a critical competency for research and development professionals.

Understanding the Basics: FAQs on Fundamental Rheological Concepts

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a Newtonian plateau and shear-thinning behavior in polymer melts?

In polymer melts, a Newtonian plateau occurs at very low shear rates, where the viscosity remains constant at its maximum value (zero-shear viscosity, η₀) because the entangled polymer chains have sufficient time to relax between deformations, resulting in a constant resistance to flow [25]. In contrast, shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) behavior manifests as a decreasing viscosity with increasing shear rate, occurring when the applied shear is sufficiently high to cause polymer chains to disentangle and align in the direction of flow [26] [25]. This molecular rearrangement reduces internal resistance, facilitating easier processing. The transition between these regimes is critical for manufacturing, as most polymer processing operations occur within the shear-thinning region.

FAQ 2: Why does viscosity plateau at both very low and very high shear rates in polymer systems?

Polymer melts exhibit three distinct regions in their viscosity profile. At very low shear rates, the viscous forces are too weak to overcome chain entanglements, resulting in a constant zero-shear viscosity plateau (η₀) where the microstructure remains unaffected [26] [25]. In the intermediate shear rate region, applied stress disentangles and aligns polymer chains, causing shear-thinning where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate [26]. At very high shear rates, polymers reach complete disentanglement and alignment, leading to a second Newtonian plateau characterized by infinite-shear viscosity (η∞), representing the minimum achievable viscosity where no further structural simplification occurs [26] [25].

FAQ 3: What molecular factors control the onset and extent of shear-thinning in polymers?

The onset and intensity of shear-thinning are governed by several molecular factors: (1) Molecular weight and distribution – Higher molecular weights increase chain entanglement density, lowering the shear rate required for thinning onset and amplifying its effect [25]; (2) Chain architecture – Branched polymers exhibit different shear-thinning profiles compared to linear chains due to varied entanglement dynamics [25]; (3) Temperature – Elevated temperatures reduce zero-shear viscosity and can shift the shear-thinning onset [25]; (4) Additives and fillers – Nanoparticles, plasticizers, or other modifiers can either enhance or suppress shear-thinning based on their interactions with polymer chains [12]. Understanding these factors enables targeted molecular design to achieve desired flow properties.

FAQ 4: How can I determine whether observed thinning is time-dependent (thixotropy) or instantaneous (shear-thinning)?

Shear-thinning (pseudoplasticity) describes an instantaneous, reversible viscosity decrease with increasing shear rate, where viscosity recovers immediately upon shear removal [26]. Thixotropy represents a time-dependent viscosity decrease under constant shear, with a slow recovery period after shear cessation [26]. To distinguish them: (1) Conduct step-rate tests – apply constant shear rates in increasing then decreasing sequences; shear-thinning shows reversible, overlapping curves while thixotropy exhibits hysteresis loops [26]; (2) Perform time-sweep tests at constant shear – instantaneous viscosity drops indicate shear-thinning, while gradual decreases suggest thixotropy [26]; (3) Implement recovery tests – rapid viscosity recovery indicates shear-thinning, while slow recovery confirms thixotropy [26].

Quantitative Rheological Models: A Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Key Mathematical Models for Describing Polymer Melt Viscosity

| Model Name | Mathematical Formulation | Parameters | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Law (Ostwald-de Waele) | Ï„ = Kγ̇⿠or η = Kγ̇â¿â»Â¹ [26] [25] |

K: Consistency indexn: Flow index (n<1 for shear-thinning) [26] [25] | • High shear-rate processes• Regions where Newtonian plateaus are negligible [25] | • Fails at very low and very high shear rates• Does not predict η₀ or η∞ [25] |

| Cross Model | η(γ̇) = η₀ / [1 + (η₀γ̇/τ*)^(1-n)] [25] |

η₀: Zero-shear viscosityτ*: Critical stress for thinning onsetn: Power law index [25] | • General polymer processing• Where low-shear-rate behavior matters [25] | • Does not account for curing effects• Limited for thermosetting polymers [25] |

| Herschel-Bulkley | τ = τ_y + Kγ̇⿠[26] |

τ_y: Yield stressK: Consistency indexn: Flow index [26] | • Yield stress fluids• Filled polymers• Suspensions with solid-like behavior at rest [26] | • More complex parameter determination• Not for simple polymer melts without yield stress [26] |

| Castro-Macosko | η(T,γ̇,α) = η₀(T) / [1 + (η₀γ̇/τ*)^(1-n)] × (α_g/(α_g-α))^(C1+C2α) [25] |

α: Degree of conversion/curingα_g: Gel pointC1, C2: Fitting constants [25] | • Reactive processing• Thermoset polymers• Curing-dependent viscosity [25] | • Complex parameter determination• Overly complicated for non-reactive systems [25] |

Table 2: Key Rheological Parameters and Their Experimental Determination

| Parameter | Physical Significance | Experimental Determination Method | Typical Values for Polymer Melts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) | Maximum viscosity at rest; relates to molecular weight and entanglement density [25] | Extrapolation from low-shear-rate plateau in flow curve; Carreau-Yasuda model fitting [27] | 10² - 10ⶠPa·s (highly MW-dependent) |

| Infinite-Shear Viscosity (η∞) | Minimum achievable viscosity at extreme shear rates [26] [25] | High-shear-rate extrapolation; often difficult to measure directly [25] | 10â»Â¹ - 10² Pa·s |

| Power Law Index (n) | Degree of shear-thinning: lower n = more pronounced thinning [26] [25] | Slope of log(η) vs log(γ̇) in power law region [26] | 0.2-0.8 (typically 0.3-0.6 for polymer melts) |

| Transition Shear Rate (γ̇_c) | Onset of shear-thinning behavior [25] | Point of deviation from η₀ plateau in flow curve [25] | 10â»Â³ - 10² sâ»Â¹ (highly MW-dependent) |

| Activation Energy (Eâ‚) | Temperature sensitivity of viscosity [27] | Arrhenius plot of η₀ vs 1/T [27] | 20-100 kJ/mol (polymer-dependent) |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Viscosity Measurements Between Batches

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Molecular weight variations: Implement stricter control over synthetic procedures and verify molecular weight distributions for each batch [25]

- Thermal history differences: Standardize annealing protocols and thermal processing conditions to ensure consistent chain entanglement states [25]

- Moisture content: Control environmental humidity during processing and testing, as water can plasticize some polymers [25]

- Testing protocol inconsistencies: Standardize rheological measurement parameters including temperature equilibration time, shear rate sweep rates, and gap settings [28]

Problem: Unexpected Viscosity Increases in Polymer Formulations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Unintended crosslinking: Verify thermal stability limits and reduce processing temperatures if approaching degradation thresholds [25]

- Filler aggregation: Improve nanoparticle dispersion through surface modification or optimized mixing protocols [12]

- Phase separation: Characterize component compatibility and consider compatibilizers for multiphase systems [28]

- Polymer degradation: Implement antioxidant additives and reduce oxygen exposure during processing [25]

Problem: Insufficient Shear-Thinning for Target Processing Applications

Strategies for Enhancement:

- Molecular weight manipulation: Increase molecular weight to enhance entanglement density, which amplifies shear-thinning response [25]

- Chain architecture modification: Introduce long-chain branching to create more complex entanglement networks [25]

- Additive incorporation: Consider specifically designed nanoparticles that can disrupt chain entanglements under shear [12]

- Blending strategies: Create polymer blends with controlled phase separation to introduce additional shear-sensitive mechanisms [27]

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Rheological Characterization

Protocol: Establishing Complete Flow Curves for Polymer Melts

Objective: Characterize viscosity across Newtonian plateau, shear-thinning, and high-shear regions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Strain-controlled or stress-controlled rheometer with temperature control system [28]

- Appropriate geometry (cone-and-plate recommended for homogeneous shear) [28]

- Sample preparation tools (spatula, cutting device)

- Environmental control system (for humidity-sensitive materials)

Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Pre-heat rheometer plates to test temperature. Load sample between plates, ensuring complete filling without air bubbles. Trim excess material [28]

- Temperature Equilibration: Allow sufficient time (typically 5-10 minutes) for temperature equilibration, monitoring normal force until stabilization [28]

- Strain Sweep (Linear Viscoelastic Region Determination): At fixed frequency (e.g., 10 rad/s), sweep strain from 0.01% to 100% to determine maximum strain within linear response [27]

- Flow Curve Measurement: Using strain amplitude within linear region, perform steady shear rate sweep from low to high shear rates (typically 0.001-1000 sâ»Â¹), allowing sufficient time at each step for stress stabilization [28]

- Data Analysis: Plot log(viscosity) versus log(shear rate). Identify η₀ plateau at low shear rates, shear-thinning region, and potential η∞ plateau at high shear rates. Fit appropriate models (Cross, Carreau) to extract parameters [25] [27]

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If edge fracture occurs at high shear rates, reduce maximum shear rate or use roughened geometries

- For temperature-sensitive materials, use solvent traps to prevent evaporation

- If normal force trends during measurement, indicate structural changes or wall slip

Protocol: Time-Temperature Superposition for Extended Frequency Range

Objective: Construct master curves covering extended effective frequency range.

Procedure:

- Perform frequency sweeps (0.1-100 rad/s) at multiple temperatures (typically spanning 20-50°C above and below Tg or processing temperature) [27]

- Select reference temperature (often Tg or processing temperature)

- Horizontally shift data at other temperatures along frequency axis to create master curve

- Apply vertical shift factors if necessary to account for density changes

- Extract shift factors (aT) and fit to WLF or Arrhenius equations [27]

Protocol: Characterizing Structural Recovery After Shear

Objective: Quantify time-dependent recovery after shear-induced structural breakdown.

Procedure:

- Pre-shear sample at high shear rate (e.g., 100 sâ»Â¹) for defined duration to ensure consistent initial structure

- Immediately step shear rate to very low value (e.g., 0.01 sâ»Â¹)

- Monitor viscosity recovery as function of time

- Fit recovery curve to appropriate model (exponential, stretched exponential) to quantify recovery kinetics [26]

Advanced Strategies for Viscosity Reduction in Polymer Melts

Nanoparticle-Based Viscosity Control

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate that specifically designed nanoparticles can simultaneously address the "trilemma" of enhancing strength and toughness while reducing melt viscosity [12]. Single-chain nanoparticles with deformable surfaces enable this unique combination by:

- Lubrication mechanism: Polymer chains partially penetrate and slide along nanoparticle surfaces, facilitating disentanglement [12]

- Structural stabilization: Nanoparticles migrate during deformation to form crossties between fibrils, delaying crazing and stabilizing the structure [12]

- Reduced entanglement density: Nanoparticles create topological constraints that modify chain dynamics without increasing viscosity [12]

Table 3: Nanoparticle Additives for Viscosity Modification

| Nanoparticle Type | Mechanism of Action | Effect on Viscosity | Additional Benefits | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Chain Nanoparticles (deformable) | Chain sliding on rugged surfaces; entanglement dilution [12] | Reduction (up to 60% reported) [12] | Simultaneous increases in strength and toughness [12] | Requires specific compatibility with matrix |

| Rigid Nanocrystals (Porous Organic) | Chain alignment through pores; restricted mobility [12] | Increase (typically) [12] | Enhanced strength and stiffness [12] | Generally increases process difficulty |

| Silica Nanoparticles | Network formation; restricted chain mobility [26] | Increase (can induce yield stress) [26] | Enhanced thermal stability; thixotropy [26] | Surface modification critical for dispersion |

Molecular Design Approaches for Targeted Rheology

Bottlebrush Copolymers represent a powerful architectural strategy for viscosity control through their inherent dynamic tube dilution effect [27]. The side chains act as built-in solvents, diluting backbone concentration and resulting in significantly reduced zero-shear viscosity compared to linear polymers of equivalent molecular weight [27]. This approach enables:

- Viscosity reduction without compromising molecular weight

- Tunable shear-thinning through side chain length and density manipulation

- Enhanced processability while maintaining mechanical performance in final product [27]

Block Sequence Control significantly impacts viscoelastic response, with sequential block copolymers generally exhibiting enhanced mechanical strength and more pronounced shear-thinning compared to statistical copolymers of identical composition [27]. This enables precise tuning of flow properties for specific processing methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Materials for Rheological Studies of Polymer Melts

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethyl methacrylate) Derivatives | Model polymer for rheological studies [12] | Fundamental studies of shear-thinning behavior [12] | Wide range of molecular weights available; good thermal stability |

| Soybean Phosphatidylcholine (SPC) | Lipid component for vesicle formation [28] | Drug delivery system rheology; ultradeformable liposomes [28] | Natural source; biocompatible; requires strict temperature control |

| Carbomer Polymers (e.g., Carbopol 974P) | Rheology modifier; gelling agent [29] | Pharmaceutical gels; mucoadhesive systems [29] | pH-dependent gelation; strong shear-thinning behavior |

| Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) (POEGMA) | Neutral water-soluble block [27] | Double hydrophilic block copolymers for drug delivery [27] | Biocompatible; tunable LCST; versatile functionality |

| Silica Nanoparticles | Rheological modifier; reinforcement filler [26] | Creating yield stress fluids; viscosity enhancement [26] | Surface chemistry critical for compatibility; concentration-dependent effects |

| Single-Chain Nanoparticles | Multifunctional additive [12] | Breaking strength-toughness-processability trilemma [12] | Specific synthesis required; deformable surface essential |

| SMI 6860766 | SMI 6860766, CAS:433234-16-3, MF:C15H11BrClNO, MW:336.61 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SZL P1-41 | SZL P1-41, MF:C24H24N2O3S, MW:420.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Material Behavior

Polymer Rheology Characterization Workflow

Viscosity versus Shear Rate Profile

Emerging Research Directions and Future Perspectives

The field of polymer rheology continues to evolve with several promising research directions for addressing viscosity challenges. Nonlinear preconditioning frameworks represent an advanced computational approach for solving complex nonlinear rheological problems, particularly those involving shear-thinning behavior in materials with complex microstructure [30]. These methods help overcome convergence issues in simulations of materials exhibiting strong non-Newtonian behavior.

The integration of machine learning and neural network approaches with rheological measurement is emerging as a powerful strategy for melt viscosity control in polymer extrusion [31]. These methods enable real-time viscosity prediction and adjustment, potentially revolutionizing processing of complex polymeric systems.

Continued development of multi-stimuli responsive polymers with precisely tunable rheological behavior offers exciting possibilities for advanced drug delivery and manufacturing applications [27]. Systems that undergo predictable viscosity changes in response to temperature, pH, or other external cues represent a frontier in smart material design with significant implications for pharmaceutical processing and biomedical applications.

Innovative Computational and Experimental Methods for Viscosity Control

Leveraging High-Throughput Molecular Dynamics as a Data Flywheel

Troubleshooting Guides

Table: Common HT-MD Workflow Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Preparation | Simulation fails during energy minimization or initial steps. | Incorrect topology or parameters for polymer force field. [32] | Use automated tools like StreaMD for system preparation and verify force field compatibility with your polymer's chemistry. [32] |

| Sampling & Performance | Simulation cannot access rare, high-barrier events (e.g., polymer chain disentanglement). | Conventional MD timescales are too short to observe slow dynamics. [33] | Integrate enhanced sampling techniques, such as metadynamics or variationally enhanced sampling, to improve sampling of rare events. [34] |

| Data Generation & Accuracy | MD-predicted properties (e.g., viscosity) deviate significantly from experimental data. | Systematic force field error or insufficient sampling of configurational space. [24] | Employ a high-throughput workflow to calibrate force fields and run replicas; use metrics beyond average errors to validate against target properties. [33] [24] |

| Analysis & Property Calculation | Viscosity calculation from NEMD is noisy or non-convergent. | Simulation time is too short, or shear rate in NEMD is too high. [24] | Extend simulation duration to improve statistics and ensure shear rate is in the linear response regime. Use automated analysis pipelines. [24] [32] |

Table: Troubleshooting Polymer Melt Viscosity Issues

| Observed Issue | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly Low Viscosity | 1. Check for bond-breaking events using analysis tools.2. Analyze polymer chain dimensions (e.g., radius of gyration) over time. | Review and validate the force field's ability to describe polymer chain scission or check for unrealistic chain collapse. [35] |

| Viscosity Diverges or is Unphysical | 1. Verify the integrity of the topology and bonding parameters.2. Check system stability (energy, temperature) during equilibration. | Re-run system preparation, paying close attention to the assignment of bonded terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals) in the polymer. [35] |

| Poor Reproducibility Across Replicas | 1. Confirm consistent starting configurations and simulation parameters.2. Check for adequate sampling by comparing property distributions. | Standardize the simulation setup using an automated pipeline like StreaMD to minimize manual intervention and errors. [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core concept of using High-Throughput MD as a "Data Flywheel" in polymer science?

The "Data Flywheel" concept refers to an automated, integrated pipeline where high-throughput MD simulations generate large, consistent datasets from a small initial set of structures. This data is then used to train machine learning (ML) models for virtual screening and to uncover quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPR). The insights gained guide the selection of new candidates for subsequent rounds of simulation, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of data production and model improvement, which is especially powerful in data-scarce fields like polymer melt research. [24]

Q2: How can I quickly generate a large dataset for polymer viscosity analysis?

A high-throughput pipeline can be established by:

- Input: Starting from a library of polymer structures defined by their SMILES strings. [24]

- Automation: Using a tool like StreaMD or a custom script to automate the workflow: system preparation (solvation, parameterization), simulation execution (equilibration, production NEMD), and data analysis (viscosity calculation). [32]

- Parallelization: Distributing thousands of independent simulations across a computing cluster or network using libraries like Dask to maximize throughput. [32] This approach can transform a handful of polymer types into a dataset of over a thousand entries for analysis. [24]

Q3: Our ML models trained on MD data fail to predict experimental viscosity. What could be wrong?

This is often a problem of data quality and representativeness, not just quantity.

- Systematic Error: The force field used in MD may have inherent inaccuracies for your specific polymer chemistry, creating a systematic bias in all your training data. [24]

- Insufficient Sampling: The MD simulations might not be long enough to capture the slow, complex dynamics of polymer melts, leading to inaccurate viscosity labels for your ML model. [35]

- Poor Generalization: The initial training data might not cover a diverse enough chemical space. Use data augmentation strategies (e.g., varying chain lengths, tacticity) and ensure your ML model incorporates physically meaningful descriptors to improve transferability. [24]

Q4: What are the best practices for ensuring our HT-MD workflow is robust and reproducible?

- Automation: Minimize manual steps to reduce human error. Tools like StreaMD automate system setup, execution, and analysis. [32]

- Documentation & Versioning: Keep meticulous records of all simulation parameters, software versions, and force fields. [36]

- Validation: Do not rely solely on average errors. Develop quantitative metrics that are directly relevant to the dynamics you are studying (e.g., rare event prediction) to validate your MD results. [33]

- Checkpointing: Always use simulation checkpoint files. This allows you to recover from failures and extend simulations seamlessly, which is critical for managing large queues in high-throughput work. [32]

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: High-Throughput NEMD for Polymer Viscosity

This protocol outlines the process for calculating shear viscosity of polymer melts using Non-Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (NEMD) in a high-throughput manner. [24]

System Preparation

- Initial Structure: Generate an initial configuration of the polymer melt with a sufficient degree of polymerization (e.g., >10 monomers) to avoid finite-size effects. A typical system may contain 10,000-100,000 atoms. [24]

- Force Field Assignment: Assign atom types and interaction parameters using a suitable force field (e.g., AMBER99SB-ILDN, OPLS-AA). The choice must be validated for the specific polymer chemistry. [32] [35]

- Solvation and Energy Minimization: Place the structure in a simulation box and perform energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm to remove bad contacts and prepare the system for dynamics. [32]

Equilibration

- NVT Ensemble: Run a simulation in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble for 1-5 ns to stabilize the system temperature (e.g., 300-500 K for melts). Use a thermostat like Nosé-Hoover. [35]

- NPT Ensemble: Subsequently, run in the NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensemble for 5-10 ns to achieve the correct melt density. Use a barostat like Parrinello-Rahman. [35]

Production Run (NEMD)

- Apply Shear: Conduct the production run under the SLLOD equations of motion combined with a Lees-Edwards boundary condition to impose a steady-state shear flow. [24]

- Shear Rate: Apply a constant, low shear rate to ensure the system remains in the linear response regime, where Newtonian behavior is observed. A typical rate might be 10^7 to 10^9 sâ»Â¹, but this is system-dependent. [24]

- Duration: Simulate for a sufficiently long time (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) to obtain a well-converged average for the viscous stress tensor.

Viscosity Calculation

- The shear viscosity (η) is calculated using the Green-Kubo relation from equilibrium MD or, as in this NEMD protocol, directly from the ratio of the average shear stress (P{xy}) to the applied shear rate (γ̇): η = - ⟨P{xy}⟩ / γ̇

- Average the stress component over the production phase of the simulation to obtain the final viscosity value.

Workflow Visualization

DOT Script for HT-MD Data Flywheel

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Defines the potential energy function and parameters governing atomic interactions. [35] | AMBER99SB-ILDN, OPLS-AA; must be chosen and validated for the specific polymer system. [32] |

| MD Simulation Software | Engine for performing the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. [32] | GROMACS is a common, versatile, and high-performance choice for running HT-MD. [32] |

| Automation & HT Toolkits | Scripts or software to manage the end-to-end simulation workflow with minimal user input. [32] | StreaMD (for general MD), RadonPy (for polymers); automate setup, execution, and analysis. [24] [32] |

| Polymer Structures (SMILES) | The starting molecular input that defines the chemical structure to be simulated. [24] | Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System; enables automated construction of polymer chains. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Accelerates the sampling of rare events and complex free energy landscapes. [34] | Metadynamics, variationally enhanced sampling; crucial for probing high-barrier processes in melts. [34] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Used to build models from HT-MD data for prediction and discovery. [24] | XGBoost, Scikit-learn for traditional ML; SHAP and Symbolic Regression for interpretability. [24] |

| Tabersonine | Tabersonine, CAS:4429-63-4, MF:C21H24N2O2, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sofpironium Bromide | Sofpironium Bromide, CAS:1628106-94-4, MF:C22H32BrNO5, MW:470.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Explainable AI and Symbolic Regression for Quantifying Structure-Property Relationships

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my AI model for polymer viscosity prediction a "black box" and how can I interpret it?

Issue: Traditional machine learning models like deep neural networks provide accurate viscosity predictions but lack interpretability, making it difficult to understand the underlying structure-property relationships [37] [38]. These "black box" models cannot provide the physical or chemical intuition needed for scientific discovery.

Solution: Implement Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, particularly Symbolic Regression (SR), to obtain transparent, interpretable models.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Model Assessment: Determine if your current model is a black box by checking whether you can mathematically trace how input features affect viscosity predictions.

- Symbolic Regression Implementation: Apply SR to discover compact mathematical expressions that describe the relationship between polymer structures and viscosity.

- Expression Validation: Test the derived symbolic expressions against known physical laws and experimental data to ensure physicochemical validity.

- Feature Analysis: Use SR outcomes to identify which structural features (e.g., molecular weight, branching) most significantly impact viscosity.

Preventive Measures:

- Incorporate domain knowledge constraints during model training.

- Use techniques like SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) that combine symbolic regression with compressed sensing for materials data [39].

- Implement hierarchical SR approaches to manage complex, high-dimensional polymer systems.

How can I overcome data scarcity when building viscosity prediction models?

Issue: High-quality, diverse datasets for polymer viscosity are scarce, expensive to generate, and often inconsistent, limiting AI model performance [24] [40].

Solution: Employ a multi-faceted approach combining data augmentation, high-throughput computation, and specialized algorithms for small datasets.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Data Production: Utilize high-throughput all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) as a "data flywheel" to generate consistent viscosity data computationally [24].

- Feature Engineering: Apply automated molecular feature engineering to extract maximum information from limited data [24].

- Transfer Learning: Leverage knowledge from related chemical tasks or larger materials databases to improve performance on small viscosity datasets [41].

- Active Learning: Implement iterative cycles where the model guides which new experiments or simulations would be most informative.

Validation Protocol:

- Use k-fold cross-validation with limited data.

- Validate computational predictions with targeted experiments.

- Compare SR results with traditional mixing rules and physical models [9].

Why does my symbolic regression model produce overly complex expressions?

Issue: SR sometimes generates complicated, hard-to-interpret mathematical expressions that may be overfitted to the training data [42].

Solution: Apply regularization techniques and simplified SR approaches designed to produce parsimonious models.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Complexity Constraints: Implement filter-introduced genetic programming (FIGP) to generate simpler expressions [42].

- Noise Introduction: Add empirical noise and variable swapping to training data to reduce overfitting and increase model robustness [9].

- Model Selection: Prioritize expressions with fewer terms and lower complexity when performance differences are minimal.

- Physical Unit Consistency: Ensure derived expressions maintain dimensional consistency, which often naturally reduces complexity.

Advanced Techniques:

- Use Pareto optimization to balance model accuracy and complexity.

- Apply SISSO++ for improved feature representation and refined solver algorithms [39].

How can I improve prediction of melt fracture and extrusion defects?

Issue: Melt fracture and extrusion defects occur due to complex interactions between polymer structure, rheology, and processing conditions [13].

Solution: Develop interpretable AI models that connect molecular features to processing behavior.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Defect Identification: Classify the specific defect type (sharkskinning, washboarding, gross distortion) to guide troubleshooting [13].

- Feature Selection: Identify key molecular descriptors (molecular weight, branching, MWD) that influence defect formation.

- SR Model Building: Apply symbolic regression to derive quantitative relationships between polymer structures and critical rheological parameters.

- Process Optimization: Use interpretable models to guide adjustments in extrusion rate, die temperature, and die design.

Key Adjustments:

- For high molecular weight polymers: Reduce extrusion rates to decrease shear stress [13].

- For problematic die designs: Modify to include smoother transitions and adequate land lengths.

- Consider processing aids or alternative polymer grades with narrower molecular weight distributions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between traditional AI and symbolic regression for polymer research?

Traditional AI (e.g., deep neural networks) operates as a "black box" that makes predictions based on complex statistical correlations without revealing underlying mathematical relationships. In contrast, symbolic regression discovers compact, interpretable mathematical expressions that directly describe structure-property relationships, similar to fundamental scientific equations [37] [38].

Q2: How does explainable AI accelerate polymer discovery compared to traditional methods?

Explainable AI significantly shortens development cycles by replacing resource-intensive Edisonian approaches (trial-and-error) with data-driven insights. It provides interpretable models that guide researchers toward promising molecular designs, reducing the need for exhaustive experimental screening [24] [41].

Q3: Can AI completely replace experimental measurements for polymer viscosity prediction?

No. AI should complement rather replace experiments. While high-throughput MD simulations can generate initial datasets [24], and AI models can predict properties, experimental validation remains essential for verifying predictions and ensuring real-world applicability [9].

Technical Implementation

Q4: What types of polymer descriptors work best with symbolic regression?

Physically meaningful descriptors with clear connections to polymer properties tend to yield the most interpretable and robust models. These include molecular weight, molecular weight distribution, branching characteristics, and chemical composition features [40] [43]. Automated descriptor engineering can also help identify relevant features without extensive domain knowledge [24].

Q5: How much data is needed to build reliable symbolic regression models for viscosity prediction?

Symbolic regression can be effective with relatively small datasets (hundreds to thousands of entries) compared to deep learning approaches that require massive data [24] [39]. For example, meaningful viscosity models have been built with datasets of ~1,200 entries [24] or even smaller focused collections.

Q6: What are the most common pitfalls when applying SR to polymer viscosity problems?

Common issues include: overfitting to limited data, generating overly complex expressions, ignoring physical constraints (like unit consistency), and insufficient validation against experimental data. These can be mitigated through regularization, noise introduction, and rigorous cross-validation [42] [9].

Application and Validation

Q7: How can I validate that my symbolic regression model has discovered physically meaningful relationships?

Validation strategies include: (1) Checking consistency with known physical laws and principles, (2) Testing predictions on hold-out data not used for training, (3) Comparing with established empirical models, and (4) Experimental verification of novel predictions [9] [38].

Q8: What viscosity parameters are most suitable for SR modeling?

Both fundamental parameters (zero-shear viscosity, relaxation time, shear thinning behavior) and industrial indicators (Melt Flow Rate) have been successfully modeled with SR [9] [43]. The choice depends on available data and application requirements.

Q9: Can symbolic regression help identify new polymer structures for reduced viscosity issues?

Yes. By providing interpretable relationships between molecular features and viscosity, SR enables inverse design - identifying promising polymer structures that target specific viscosity profiles while minimizing processing issues like melt fracture [24] [13].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Methods for Polymer Property Prediction

| Method | Typical Data Requirements | Interpretability | Accuracy (R² Range) | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Regression | 10²-10³ entries [24] | High (explicit equations) | 0.85-0.99+ [9] | MFR prediction, shear viscosity models |

| Genetic Programming (GP) | 10²-10ⴠentries [38] | Medium-High | Varies with complexity | Fundamental property relationships |

| Filter-Introduced GP (FIGP) | 10²-10³ entries [42] | High (simpler expressions) | Comparable or better than GP [42] | Drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility |

| Deep Neural Networks | 10â´-10â· entries [24] | Low (black box) | High with sufficient data [40] | Complex pattern recognition |

| Random Forest/SVM | 10²-10ⴠentries [37] | Medium | Moderate to high [37] | Glass transition temperature, mechanical properties |

Table 2: Molecular Parameters and Their Impact on Polymer Melt Viscosity

| Parameter | Effect on Zero-Shear Viscosity | Effect on Shear Thinning | Influence on Processing Issues | SR Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Proportional to ~Mw^3.4 above critical Mw [43] | Increases shear sensitivity | High M_w increases melt fracture risk [13] | Power-law expressions with M_w terms |

| Molecular Weight Distribution | Moderate effect | Broad MWD increases thinning at lower rates [43] | Broader MWD can improve processibility | Complex terms representing distribution width |

| Long Chain Branching | Increases at low frequency [43] | Significant increase in rate dependence | Affects die swell, strain hardening [43] | Separate branching parameters in models |

| Chain Architecture | Varies with flexibility | Depends on branch length/frequency | Influences relaxation spectrum | Topological descriptors |