Antimicrobial Polymer Composites: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Applications in Healthcare

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of antimicrobial polymer composites, addressing the critical need for innovative materials to combat healthcare-associated infections and multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Antimicrobial Polymer Composites: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Applications in Healthcare

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of antimicrobial polymer composites, addressing the critical need for innovative materials to combat healthcare-associated infections and multidrug-resistant pathogens. It explores the foundational mechanisms of action, including contact-killing, biocide-releasing, and anti-fouling strategies, against a broad spectrum of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. The review systematically compares the efficacy of composites incorporating metal nanoparticles, metal oxides, and natural compounds, linking their structural properties to antimicrobial performance. Further, it details advanced fabrication techniques, applications in high-touch surfaces and food packaging, and the challenges of standardization in efficacy testing. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis synthesizes current research trends to guide the development of next-generation, sustainable antimicrobial materials with enhanced safety and functionality.

Unveiling the Mechanisms: How Antimicrobial Polymer Composites Combat Pathogens

The growing challenge of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and antimicrobial resistance has accelerated the development of advanced materials capable of reducing microbial transmission. Antimicrobial polymer composites represent a critical technological advancement in this field, offering a first line of defense against pathogenic microbes on high-touch surfaces and medical devices [1]. These materials are particularly valuable in healthcare settings, where approximately one in 31 hospital patients acquires at least one HAI, contributing to an estimated 72,000 deaths annually in U.S. acute care hospitals alone [1]. Unlike conventional antibiotics, antimicrobial polymers pose a minimal risk of developing contagions with antibiotic resistance, making them an increasingly important component of infection control strategies, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic [1] [2].

Antimicrobial polymer composites function through distinct mechanisms that can be broadly categorized into three primary systems: biocidal polymers, polymeric biocides, and biocide-releasing systems. Each system offers unique advantages and limitations regarding spectrum of activity, durability, environmental impact, and potential for resistance development. Understanding these fundamental categories is essential for researchers and scientists developing new antimicrobial materials for healthcare applications, drug development, and medical device manufacturing. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these systems, focusing on their defining characteristics, mechanisms of action, experimental assessment methodologies, and relative performance metrics to inform research direction and material selection.

Classification and Mechanisms of Action

Antimicrobial polymer composites are classified based on their fundamental structure and mechanism of antimicrobial action. The three primary systems—biocidal polymers, polymeric biocides, and biocide-releasing systems—differ significantly in their composition, functionality, and applications.

Defining the Three Primary Systems

Biocide-Releasing Systems: These materials consist of a polymeric matrix that acts as a reservoir for antimicrobial agents (biocides), which are released from the material to exert their effect on surrounding microbes [1] [3]. The polymer itself is typically inert and serves primarily as a delivery vehicle. These systems can be further categorized based on their release mechanisms, including diffusion-controlled, chemically-controlled, or environmentally-triggered release [3]. Examples include polymers loaded with metal nanoparticles (e.g., silver, copper), antibiotics, or natural antimicrobials like essential oils [4] [5].

Polymeric Biocides: These macromolecules contain antimicrobial functional groups embedded within their main-chain backbone or as side chains [1] [3]. Unlike biocide-releasing systems, the antimicrobial activity is an intrinsic property of the polymer itself rather than an additive that migrates from the material. The antimicrobial repeating units are covalently bonded to the polymer structure, making them non-leaching [1]. Examples include polymers with quaternary ammonium compounds, N-halamines, or antimicrobial peptides tethered to their structure [1] [6].

Biocidal Polymers: This broader category includes polymer systems that exhibit antimicrobial activity through various mechanisms, not necessarily requiring covalently bonded antimicrobial groups [3]. They encompass polymeric biocides but also include systems where the polymer itself may not be directly biocidal but creates a biocidal environment or surface through physical or chemical properties. These can include polymers with inherent antimicrobial properties, nanocomposites with antimicrobial fillers, or blends of inert polymers with polymeric biocides [3].

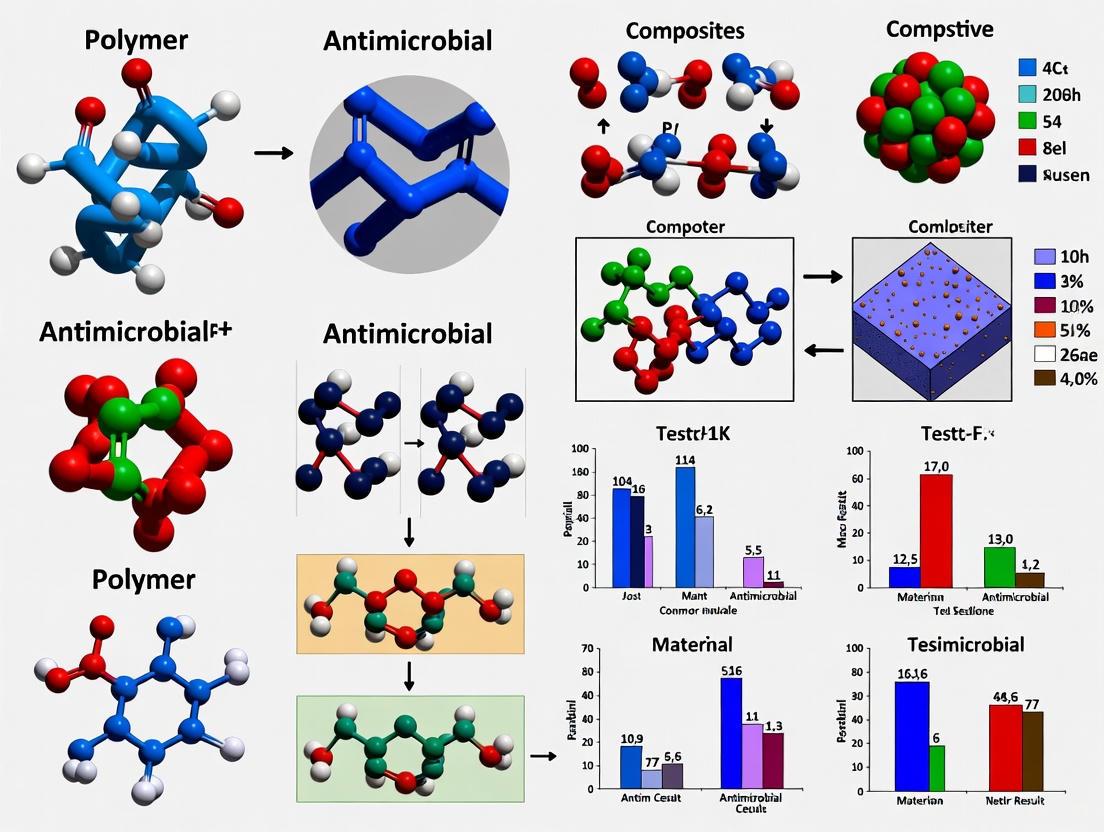

The following diagram illustrates the structural relationships and key characteristics of these three systems:

Antimicrobial Mechanisms at the Cellular Level

The antimicrobial efficacy of these polymer systems derives from their ability to disrupt essential microbial structures and functions. The specific mechanisms vary significantly between systems and target microorganisms:

Membrane Disruption Mechanisms: Polymeric biocides and certain biocidal polymers primarily act through direct contact with microbial cell membranes. For bacteria, the phospholipid sponge effect occurs when negatively charged phospholipids from cell membranes are attracted to positively charged surface groups, damaging the phospholipid bilayer and causing cell death [1]. When the tethering molecule is sufficiently long, the polymeric spacer effect allows the biocide to penetrate the cell membrane, leading to leakage of cellular contents [1]. These mechanisms are particularly effective against Gram-positive bacteria, though less so against Gram-negative bacteria due to their protective outer membrane [3].

Oxidative Damage Mechanisms: Certain polymeric biocides incorporating N-halamines or other oxidative compounds cause microbial inactivation through the action of oxidative halogen targeted at thio or amino groups of cell receptors [6]. This mechanism effectively disrupts enzymatic function and cellular metabolism, leading to microbial death.

Physical Repellency Mechanisms: Some biocidal polymers function through passive anti-fouling action rather than active microbial killing. These materials prevent microbial adhesion through hydrophilic surfaces, negative charges, or low surface free energy that repels microorganisms [1] [6]. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) achieves this through high chain mobility, large exclusion volume, and steric hindrance effects of its highly hydrated layer [1]. Zwitterionic polymers and charged polyampholytes similarly create surfaces resistant to protein adsorption and bacterial adhesion [1].

Viral Inactivation Mechanisms: Enveloped viruses like coronaviruses are particularly susceptible to materials that disrupt lipid membranes. The same mechanisms that damage bacterial membranes—particularly the phospholipid sponge and polymeric spacer effects—can effectively destabilize viral envelopes, rendering the virus non-infectious [1]. Non-enveloped viruses are generally more resistant to these physical disruption mechanisms.

The following diagram illustrates the primary antimicrobial mechanisms employed by these different polymer systems:

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methodologies

Standardized testing methodologies are essential for evaluating and comparing the efficacy of antimicrobial polymer composites. The following section outlines key experimental approaches used in the field.

Quantitative Efficacy Testing Protocols

Shake Flask Method (for Biocide-Releasing Systems): This quantitative method determines microbial reduction by measuring optical density at 600nm or counting colony-forming units (CFU). In a typical protocol, sample discs are immersed in inoculated nutrient broth and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with rotational shaking at 150rpm [7]. The antimicrobial activity is calculated based on the reduction in CFU or optical density compared to controls. This method is particularly suitable for evaluating biocide-releasing systems where antimicrobial agents diffuse into the surrounding medium.

Solid-State Diffusion Tests (for Non-Leaching Systems): These tests evaluate antimicrobial activity under dry conditions that mimic real-world applications like air conditioner filters or high-touch surfaces [4]. Samples are placed on inoculated solid media, and zones of inhibition or direct surface contact methods assess antimicrobial efficacy. This approach is particularly relevant for evaluating polymeric biocides and biocidal polymers that function through contact-killing without releasing antimicrobial agents into the environment.

Contact-Killing Assays: These tests evaluate materials that kill microbes upon direct contact without releasing biocidal agents. Microbial suspensions are applied directly to material surfaces, incubated for specific time intervals, then removed and assessed for viability [1]. This method is essential for validating the efficacy of polymeric biocides and certain biocidal polymers that function through surface-mediated mechanisms.

Biofilm Formation assays: These specialized tests evaluate a material's ability to prevent or disrupt biofilm formation, which is crucial for healthcare applications where approximately 80% of bacterial infections are biofilm-related [1]. Methods include growing biofilms on material surfaces and quantifying biomass through crystal violet staining or assessing metabolic activity using resazurin assays.

Standardized Comparison Framework

To enable direct comparison between different antimicrobial polymer systems, researchers should employ a standardized testing framework that evaluates key performance parameters:

Table 1: Standard Testing Parameters for Antimicrobial Polymer Composites

| Parameter | Test Method | Biocide-Releasing Systems | Polymeric Biocides | Biocidal Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial Activity | ISO 22196 / JIS Z 2801 | High initial efficacy | Sustained efficacy | Variable based on mechanism |

| Antiviral Activity | ISO 21702 (enveloped viruses) | Limited unless specifically formulated | Effective against enveloped viruses | Dependent on specific formulation |

| Duration of Activity | Extended incubation tests | Limited by reservoir depletion | Long-lasting | Potentially long-lasting |

| Leaching Potential | Extraction tests followed by HPLC/ICP-MS | High | Minimal to none | Minimal to moderate |

| Surface Adhesion Resistance | Anti-fouling assays with fluorescent tagging | Limited inherent resistance | Good resistance | Excellent resistance |

| Cytotoxicity | ISO 10993-5 (MTT assay) | Variable (depends on biocide) | Generally low with proper design | Generally low |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Direct comparison of the three antimicrobial polymer systems reveals distinct performance profiles that dictate their suitability for specific applications.

Efficacy and Durability Comparison

Comprehensive evaluation of antimicrobial performance across multiple parameters demonstrates significant differences between the three systems:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Antimicrobial Polymer Systems

| Performance Characteristic | Biocide-Releasing Systems | Polymeric Biocides | Biocidal Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrum of Activity | Broad-spectrum (depends on biocide) | Primarily antibacterial, some antiviral | Variable (can be tailored) |

| Speed of Action | Rapid (minutes to hours) | Moderate to rapid (contact-dependent) | Variable (mechanism-dependent) |

| Duration of Efficacy | Limited (depletes over time) | Long-lasting (non-depleting) | Long-lasting |

| Risk of Resistance Development | Moderate to high | Low | Low to moderate |

| Surface Coverage Requirement | Local and surrounding area | Direct contact only | Direct contact only |

| Environmental Impact | Potential leaching concerns | Minimal environmental impact | Minimal environmental impact |

| Toxicity Profile | Variable (depends on biocide) | Generally favorable | Generally favorable |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | Moderate |

| Cost Considerations | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | Moderate |

Recent research has highlighted both the capabilities and limitations of these systems. For instance, studies on copper nanoparticle-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) and polyurethane (TPU) composites for 3D-printed air conditioner filters demonstrated significant antibacterial activity in liquid tests but limited efficacy in solid-state diffusion tests after processing, highlighting how manufacturing methods and testing conditions dramatically influence observed performance [4]. This underscores the importance of testing antimicrobial materials under conditions that simulate their intended application environment.

Material Composition and Formulation Strategies

The specific composition of antimicrobial polymer composites significantly influences their performance characteristics:

Table 3: Common Material Compositions and Their Properties

| System Category | Typical Matrix Materials | Antimicrobial Agents/Functional Groups | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocide-Releasing Systems | PVC [7], PET-EVA [8], Epoxy [1] | Metal nanoparticles (Ag, Cu) [4] [9], Zinc oxide [5], Essential oils [5], Traditional antibiotics [3] | Broad-spectrum activity, Rapid efficacy, Established manufacturing methods | Limited longevity, Potential environmental contamination, Resistance development |

| Polymeric Biocides | Quaternary ammonium polymers [1] [6], N-halamine polymers [6], Polyethylenimine [6] | Covalently bonded quaternary ammonium groups [1], N-halamine compounds [6], Antimicrobial peptides [1] | Non-leaching, Long-lasting activity, Low resistance development, Stable chemistry | Complex synthesis, Potential toxicity if improperly designed, Limited to contact activity |

| Biocidal Polymers | PEG [1] [6], Zwitterionic polymers [1], Chitosan [5], Alginate [5] | Passive repellent groups [1], Chitosan amino groups [5], Composite nanostructures [3] | Anti-fouling properties, Excellent biocompatibility, Multifunctional capabilities | May not kill microbes, Effectiveness depends on environmental conditions |

Recent innovations have explored hybrid approaches that combine multiple mechanisms to overcome individual limitations. For example, Liang et al. combined N-halamine siloxane (a biocide-releasing system) with quaternary ammonium salt siloxane (a polymeric biocide) to form a composite polyurethane coating that displayed lasting antimicrobial activity due to the addition of the contact-killing quaternary ammonium compounds, which continued to provide antimicrobial action after the releasing component was depleted [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Developing and evaluating antimicrobial polymer composites requires specific reagents and materials tailored to each system:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Antimicrobial Polymer Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [7], Polylactic acid (PLA) [4], Polyurethane (TPU) [4], Chitosan [5], Ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) [8] | Base material for composite formation | Provides structural integrity, processability, and determines physical properties |

| Antimicrobial Additives | Silver nanoparticles [4] [9], Copper nanoparticles/oxides [4] [8], Zinc oxide [8] [5], Quaternary ammonium salts [1] [6], Moringa seed oil [7] | Impart antimicrobial activity to biocide-releasing systems | Active antimicrobial agents that migrate or diffuse to exert effect |

| Surface Modification Agents | Ionic liquids [7], Polyethylene glycol (PEG) [1] [6], Zwitterionic compounds [1] [6], Silane coupling agents | Creating biocidal polymer surfaces | Modify surface properties to create repellent or contact-killing characteristics |

| Polymerization Reagents | Antimicrobial monomers (quaternary ammonium methacrylates [6], N-halamine precursors [6]), Initiators (AIBN, peroxides), Cross-linking agents | Synthesizing polymeric biocides | Enable covalent incorporation of antimicrobial functionality into polymer structure |

| Characterization Standards | Reference strains (S. aureus ATCC 6538, E. coli ATCC 25922 [7]), Nutrient media, Staining solutions | Standardized efficacy testing | Provide consistent, comparable assessment of antimicrobial performance |

| Tomeglovir | Tomeglovir, CAS:233254-24-5, MF:C23H27N3O4S, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sulfisoxazole Acetyl | Sulfisoxazole Acetyl, CAS:80-74-0, MF:C13H15N3O4S, MW:309.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Workflow for Development and Evaluation

A systematic approach to developing and evaluating antimicrobial polymer composites ensures comprehensive assessment and meaningful comparisons:

Research Implications and Future Directions

The comparative analysis of antimicrobial polymer composites reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each system, guiding researchers toward appropriate selection based on application requirements. Biocide-releasing systems offer immediate, broad-spectrum efficacy but face challenges with limited duration and potential environmental impact. Polymeric biocides provide durable, non-leaching protection with minimal resistance development but require more complex synthesis. Biocidal polymers offer versatile mechanisms including anti-fouling properties but may require tailored approaches for specific pathogens.

Future research directions should address several critical challenges. Standardization of testing methodologies remains paramount, as current variations in protocols complicate direct comparison between studies [1]. Development of multifunctional systems that combine mechanisms presents a promising approach to overcome individual limitations, as demonstrated by hybrid materials incorporating both releasing and contact-killing components [1]. The growing emphasis on sustainability drives innovation in biodegradable polymer matrices and green antimicrobial agents, particularly for food packaging and single-use medical devices [5] [10]. Advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing enable complex geometries and customized applications but require careful optimization to maintain antimicrobial efficacy after processing [4].

For researchers developing new antimicrobial polymer composites, the selection of appropriate systems should be guided by target applications, desired duration of activity, environmental considerations, and manufacturing constraints. Continued innovation in this field holds significant potential for reducing the burden of healthcare-associated infections, extending product shelf life, and creating safer environments across multiple sectors.

The escalating global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has intensified the search for effective antimicrobial materials, driving significant research into polymer composites with specialized surface properties [11] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the fundamental mechanisms behind these materials is crucial for developing next-generation antimicrobial solutions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three primary antimicrobial mechanisms employed in polymer composites: contact-killing surfaces, biocide-releasing systems, and anti-fouling surfaces. We objectively evaluate each mechanism's performance through experimental data, standardized testing methodologies, and practical applications within biomedical and industrial contexts. The strategic selection of antimicrobial mechanisms depends on specific application requirements, including desired duration of activity, environmental conditions, and target microorganisms [13] [3] [5].

Mechanisms of Action: Comparative Analysis

Contact-Killing Surfaces

Contact-killing materials possess non-leaching antimicrobial surfaces that inactivate microorganisms upon direct contact through various physicochemical interactions [13]. These materials provide long-lasting antimicrobial activity without depleting active components into the environment.

Mechanism: Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) exhibit antimicrobial activity primarily through electrostatic interactions between their positively charged quaternary amine groups (N+) and negatively charged bacterial cell membranes [13]. This interaction disrupts membrane integrity, leading to cell leakage and death. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), consisting of 20-50 amino acids with hydrophobic and cationic regions, compete with magnesium and calcium ions to disrupt electrochemical gradients across bacterial membranes, ultimately causing cell death [11] [13]. The antimicrobial efficacy of both QACs and AMPs increases with greater density of active groups on the material surface [13].

Experimental Evidence: In dental resin composites, QACs with longer alkyl chains demonstrate enhanced antibacterial activity due to increased hydrophobicity, which improves penetration through bacterial cell membranes [13]. Immobilized AMPs like Dhvar4 reduce growth of oral pathogens such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, Veillonella parvula, and Prevotella intermedia by approximately 3 logs [13]. Hybrid peptides combining attacin and coleoptericin-like proteins show enhanced activity against E. coli [11].

Table 1: Efficacy Data for Contact-Killing Antimicrobial Materials

| Material Type | Target Microorganism | Efficacy Results | Testing Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| QACs in dental polymers | Streptococcus mutans (oral pathogen) | >99% reduction in bacterial viability | JIS Z 2801 [13] |

| Immobilized Dhvar4 AMP | F. nucleatum, V. parvula, P. intermedia | ~3 log reduction in bacterial growth | Not specified [13] |

| Hybrid attacin-coleoptericin peptide | Escherichia coli | Enhanced antimicrobial activity | Laboratory assessment [11] |

| Quaternary ammonium monomers | Mixed oral biofilms | Significant inhibition of biofilm formation | ASTM E2180 [13] |

Biocide-Releasing Systems

Biocide-releasing systems function through controlled release of antimicrobial agents from a polymer matrix, enabling targeted delivery to microorganisms over time [3] [5]. These systems typically provide high initial antimicrobial activity but may have limited longevity compared to contact-killing approaches.

Mechanism: Biocide-releasing systems incorporate various antimicrobial agents including metal nanoparticles (silver, zinc, copper), plant-derived compounds (essential oils), and synthetic chemicals [14] [15] [5]. The release kinetics depend on diffusion processes, polymer matrix properties, and environmental conditions. Metal nanoparticles like silver and zinc release ions that disrupt microbial cell walls and interfere with enzymatic functions [15] [5]. Natural compounds such as essential oils from thyme or oregano disrupt cell membranes through hydrophobic interactions [5].

Experimental Evidence: Silver-doped hydroxyapatite (5% Ag/HAp) demonstrates inhibition zones of 19.7 mm and 13.8 mm against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, in disc diffusion tests [15]. Chitosan-based coatings exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, and yeasts through electrostatic interactions with microbial cell walls [5]. Alginate coatings function as effective carrier matrices for controlled release of antimicrobial agents like nisin, showing particular efficacy against Listeria monocytogenes [5].

Table 2: Efficacy Data for Biocide-Releasing Antimicrobial Systems

| Biocide-Releasing System | Antimicrobial Agent | Target Microorganisms | Efficacy Results | Release Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite composite | Silver nanoparticles (5%) | E. coli, S. aureus | Inhibition zones: 19.7 mm (E. coli), 13.8 mm (S. aureus) | Ion release [15] |

| Chitosan-based coating | Chitosan (natural polymer) | Broad-spectrum (bacteria, fungi, yeast) | Significant growth inhibition | Controlled diffusion [5] |

| Alginate-based coating | Nisin (bacteriocin) | Listeria monocytogenes | Promising inhibition results | Gel matrix-controlled release [5] |

| Gelatin-based film | Cinnamon/clove essential oils | E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus | Strong antibacterial activity | Diffusion-mediated release [5] |

| Polymeric micelles | Amphiphilic polycarbonate | Gram-positive bacteria | Bacterial membrane disruption | Self-assembly degradation [3] |

Anti-Fouling Surfaces

Anti-fouling surfaces prevent microbial attachment and colonization through physicochemical surface modifications, either by creating repellent surfaces or by incorporating mechano-bactericidal nanostructures [16] [17]. These approaches aim to prevent initial biofilm formation rather than killing established microorganisms.

Mechanism: Superhydrophobic surfaces with water contact angles >150° create a physical barrier that prevents microbial adhesion [17]. This effect is often achieved through micro-nano hierarchical structures inspired by natural surfaces like shark skin [17]. Nanostructured surfaces with high-aspect-ratio features physically deform and lyse bacterial membranes upon contact [16]. The antifouling efficacy depends on specific topographic features including pillar height, tip radius, spacing, and substrate stiffness [16].

Experimental Evidence: Bioinspired Fe-based amorphous coatings with superhydrophobic modification demonstrate 98.6% resistance to Nitzschia closterium f. minutissima, 87% resistance to Bovine serum albumin protein, and 99.8% resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa [17]. Nanostructured Cu₂O fibers combined with superhydrophobic layers provide dual killing-resisting functionality through controlled Cu⺠ion release and physical barrier properties [17]. Bioinspired nano- and micro-structured surfaces (NMSS) reduce real contact area and increase local shear forces, preventing microbial attachment [16].

Table 3: Efficacy Data for Anti-Fouling Surface Technologies

| Anti-Fouling Approach | Surface Characteristics | Target Microorganisms/Fouling | Efficacy Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-based amorphous coating with superhydrophobic modification | Water contact angle >150°, micro-nano hierarchical structure | Nitzschia closterium f. minutissima, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, protein adsorption | 98.6% resistance to diatoms, 99.8% resistance to P. aeruginosa, 87% resistance to protein [17] |

| Bioinspired nano-/micro-structured surfaces (NMSS) | High-aspect-ratio nanostructures, tuned geometry | Various bacterial species | Membrane deformation and cell lysis upon contact [16] |

| Shark skin-inspired topography | Micro-riblets, patterned surface | Marine fouling organisms | Significant reduction in bacterial adhesion [17] |

| Hybrid zwitterionic nanostructured surfaces | Combined topography with benign chemistries | Mixed-species biofilms | Enhanced robustness under protein conditioning [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Antimicrobial Evaluation

Standardized testing protocols are essential for objectively comparing antimicrobial efficacy across different material systems. The following section details key methodologies referenced in the literature.

Standardized Quantitative Methods

JIS Z 2801 / ISO 22196: These standard protocols evaluate antibacterial activity on plastic surfaces and other non-porous materials [13] [5]. The method involves inoculating test and control surfaces with bacterial suspensions, followed by incubation for 24 hours at 35°C under high humidity. Antimicrobial activity is quantified by calculating the difference in logarithmic values between the control and test samples after incubation [13].

ASTM E2180: This standard test method determines the effectiveness of incorporated antimicrobial agents in polymeric or hydrophobic materials against bacterial biofilm formation [13]. The method simulates conditions where biofilm formation is likely and assesses the material's ability to prevent microbial colonization on its surface.

Disc Diffusion Assay: This common screening method involves placing antimicrobial-containing discs on agar plates inoculated with test microorganisms [15]. After incubation, the diameter of inhibition zones around the discs is measured, providing a quantitative assessment of antimicrobial activity. The method was used to evaluate Ag/HAp composites, showing 19.7 mm and 13.8 mm zones for E. coli and S. aureus, respectively [15].

Specialized Testing Approaches

Marine Field Tests: For anti-fouling coatings, real-world evaluation involves immersion in marine environments with subsequent assessment of organism attachment over time [17]. These tests provide critical data on long-term performance under practical conditions.

Protein Adsorption Assays: Anti-fouling efficacy is often evaluated using protein resistance tests with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [17]. The percentage reduction in protein adsorption compared to control surfaces quantifies the anti-fouling performance.

Biofilm Inhibition Tests: Specific assays measure a material's ability to prevent biofilm formation using crystal violet staining or metabolic activity indicators [13]. These tests are particularly relevant for dental and medical applications where biofilms pose significant challenges.

Diagram 1: Three primary antimicrobial mechanisms with their molecular targets and resulting outcomes

Advanced Testing Workflows

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for evaluating antimicrobial material efficacy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Antimicrobial Polymer Studies

| Research Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs) | Contact-killing antimicrobial agents | Positively charged quaternary amine groups disrupt bacterial membranes | Dental resins, surface coatings [13] |

| Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Natural contact-killing biomolecules | 20-50 amino acids, cationic and hydrophobic domains | Defensins, jelleines, royalisin [11] [13] |

| Silver Nanoparticles (Ag NPs) | Biocide-releasing antimicrobial agents | Release Ag⺠ions that disrupt cell walls and enzymes | Ag-doped hydroxyapatite, polymer nanocomposites [15] |

| Chitosan | Natural biopolymer with inherent antimicrobial activity | Positively charged amino groups interact with bacterial cell walls | Edible coatings, wound dressings [5] |

| Alginate | Biopolymer carrier for controlled release | Forms gel matrices for sustained antimicrobial delivery | Nisin-alginate coatings for food protection [5] |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAp) | Biocompatible ceramic for composite materials | Serves as carrier for antimicrobial metal ions | Ag/HAp, Zn/HAp, Cu/HAp composites [15] |

| Superhydrophobic Agents (e.g., FAS) | Creates water-repellent anti-fouling surfaces | Low surface energy compounds with micro-nano structures | Fluorinated alkyl silanes [17] |

| Suloctidil | Suloctidil, CAS:54767-75-8, MF:C20H35NOS, MW:337.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Pimelic Diphenylamide 106 | Pimelic Diphenylamide 106, CAS:937039-45-7, MF:C20H25N3O2, MW:339.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This comparison guide demonstrates that contact-killing, biocide-releasing, and anti-fouling surfaces each offer distinct advantages for specific applications in antimicrobial polymer composites. Contact-killing surfaces provide durable, non-depleting antimicrobial activity ideal for medical devices and high-touch surfaces. Biocide-releasing systems deliver potent, immediate antimicrobial action suitable for infection control in healthcare and food packaging. Anti-fouling surfaces offer sustainable prevention of microbial colonization particularly valuable in marine and industrial applications. The choice between these mechanisms involves trade-offs between efficacy duration, spectrum of activity, potential resistance development, and environmental impact. Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches combining multiple mechanisms, improving the longevity of biocide-releasing systems, and developing more robust anti-fouling surfaces for challenging environments. As antimicrobial resistance continues to pose global health challenges, these advanced material strategies will play increasingly important roles in infection prevention and control across diverse sectors.

The escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates the development of novel materials that inactivate pathogens through non-traditional mechanisms, thereby circumventing conventional resistance pathways. Antimicrobial polymer composites represent a promising frontier in this effort, exerting their effects through precise physical and chemical interactions with key cellular structures. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the efficacy of various composite materials, focusing on three primary cellular targets: microbial membranes, intracellular proteins, and the redox environment. We objectively evaluate the performance of different composite strategies using quantitative experimental data, detailing the methodologies required to assess their antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities. The information presented is designed to assist researchers in selecting and developing the next generation of antimicrobial materials for applications ranging from medical devices to protective equipment.

Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Composite Strategies

The table below summarizes the performance of different antimicrobial composite strategies against various pathogens, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Composites and Their Cellular Targets

| Material Class | Specific Formulation | Test Microorganism | Key Efficacy Metric | Reported Value | Primary Cellular Target(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Doped Hydroxyapatite [15] | 5% Ag/HAp | E. coli | Inhibition Zone (mm) | 19.7 mm | Membrane integrity, protein function, ROS generation |

| 5% Ag/HAp | S. aureus | Inhibition Zone (mm) | 13.8 mm | Membrane integrity, protein function, ROS generation | |

| Zinc Oxide Nanocomposite [18] | 5 wt% ZnO in Dental Composite | S. mutans | Reduction in Live Bacteria (vs. control) | ~62% reduction | Biofilm disruption, membrane damage, ROS generation |

| Copper-Polymer Composite [4] | 1 wt% Cu in PLA/TPU (Liquid Test) | Gram+ & Gram- Bacteria | Antimicrobial Activity | Observed | Membrane disruption, ROS generation |

| Cold Atmospheric Plasma [19] | Reactive Oxygen & Nitrogen Species (RONS) | S. typhimurium | Inactivation Kinetics | Time-dependent; >5-log reduction | Membrane lysis, lipid peroxidation, DNA/protein damage |

| Biochar with Free Radicals [20] | Biochar (PFRs) | E. coli, S. aureus | Antibacterial Effects | Demonstrated | Oxidative stress via ROS generation |

Detailed Methodologies for Assessing Antimicrobial Activity

Agar Diffusion Assay for Metal-Doped Composites

The agar diffusion assay is a standard method for initial screening of antimicrobial activity, particularly for materials where active agents may diffuse through agar.

- Procedure: As applied to silver-doped hydroxyapatite (Ag/HAp) composites, a microbial suspension is spread evenly on an agar plate [15]. The test material, such as a disc of the composite, is then placed on the solidified agar surface. The plate is incubated to allow bacterial growth and the diffusion of antimicrobial agents.

- Data Analysis: The zone of inhibition—the clear area around the disc where bacterial growth is prevented—is measured. For instance, 5% Ag/HAp composites produced inhibition zones of 19.7 mm against E. coli and 13.8 mm against S. aureus, indicating potent, broad-spectrum activity [15].

- Considerations: This method is ideal for a qualitative and comparative initial screen but is less effective for non-diffusible materials or for determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC).

Direct Contact Test (DCT) for Surface-Active Materials

The Direct Contact Test (DCT) is designed to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of solid materials, such as dental resins or 3D-printed filters, where direct contact is the primary mode of action.

- Procedure: As used to test zinc oxide nanoparticle (ZnO-NP) composites against S. mutans, a small volume of bacterial suspension is placed directly onto the surface of the sterilized composite disc and incubated for 1 hour to ensure contact [18]. The bacteria are then eluted from the surface, diluted, and plated on agar.

- Data Analysis: After incubation, the number of viable bacterial colonies is counted. A novel composite with ZnO-NPs showed a statistically significant reduction in colony-forming units (CFUs) compared to the unmodified control, confirming surface antibacterial efficacy [18].

- Considerations: The DCT is highly relevant for applications where bacteria reside on material surfaces, such as medical implants or packaging, as it is independent of the diffusibility of the antimicrobial agent.

Biofilm Inhibition and Analysis

Assessing antibiofilm activity is crucial, as biofilms confer significant resistance to antibiotics. This is often evaluated using staining and microscopy.

- Procedure: Biofilms are grown on composite surfaces over several days (e.g., a 7-day model for S. mutans). The mature biofilm is then stained with a live/dead bacterial viability kit [18].

- Data Analysis: The stained biofilm is visualized using Confocal Raman Microscopy (CRM) or laser scanning microscopy. Live and dead cells are quantified based on fluorescence. ZnO-NP composites demonstrated a significant increase in the ratio of dead to live cells within the biofilm compared to controls, indicating strong antibiofilm activity [18].

- Considerations: This method provides visual and quantitative data on a material's ability to not only kill planktonic bacteria but also penetrate and disrupt complex biofilm structures.

Assessment of Membrane Integrity and Cellular Leakage

The integrity of the microbial membrane is a key target. Its disruption can be assessed by measuring the leakage of intracellular components.

- Procedure: For cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment, bacterial cell suspensions are treated, and samples are analyzed over time. The leakage of intracellular materials like proteins and DNA into the surrounding solution is measured using spectrophotometric methods (e.g., absorbance at 260nm and 280nm) [19].

- Data Analysis: A time-dependent increase in the concentration of leaked proteins and nucleic acids was observed in CAP-treated S. typhimurium, directly confirming the lytic effect of plasma-generated reactive species on the outer membrane and cell envelope [19].

- Considerations: This method provides direct evidence of physical membrane damage, a primary mechanism for many antimicrobial composites and treatments.

Diagram: Interplay of Primary Antimicrobial Mechanisms. This pathway illustrates how advanced composites target multiple cellular components simultaneously, leading to irreversible cell damage and death. ROS generation is a central mechanism that can cause damage across all major biomolecules [21] [19] [20].

Mechanisms of Action at the Cellular Level

Disruption of Microbial Membranes

The bacterial membrane serves as a critical barrier, and its compromise is a lethal event. Multiple composite strategies exploit this target.

- Cold Plasma-Induced Lysis: Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) generates a complex mixture of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS) such as •OH, ¹O₂, H₂O₂, and •NO. In Gram-negative bacteria like Salmonella typhimurium, these RONS target the outer membrane (OM), disrupting the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure and integrity of inner phospholipids. This damage increases membrane permeability, leading to the leakage of proteins and nucleic acids, and ultimately, cell lysis [19].

- Nanoparticle Action: Metal nanoparticles, including silver and zinc oxide, can physically associate with the bacterial membrane. This interaction can disrupt lipid bilayers and create pores, which also facilitates the uncontrolled influx of ions and efflux of cellular contents, culminating in cell death [15] [18].

Induction of Oxidative Stress

A common and potent mechanism of antimicrobial composites is the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), overwhelming the bacterial antioxidant systems.

- The Oxidative Cascade: ROS, including superoxide anions (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH), oxidize and damage all major cellular macromolecules. They cause lipid peroxidation in membranes, strand breaks and base modifications in DNA, and carbonylation of proteins, rendering them non-functional [20] [22].

- Sources of ROS: This oxidative burst can be induced by various agents.

- Metal Nanoparticles: Ag, Cu, and ZnO nanoparticles can generate ROS through catalytic reactions on their surfaces, often via the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions [15] [4].

- Biochar: Biochar can contain persistent free radicals (PFRs) that activate oxygen or persulfate to produce ROS, such as •OH and SO₄•â», which then attack pathogens [20].

- Cold Plasma: As mentioned, CAP is a direct external source of a diverse cocktail of RONS [19].

Protein Dysfunction and Enzyme Inhibition

Disruption of protein function is another effective pathway to inhibit bacterial growth and survival.

- Metal Ion Interference: Released metal ions (e.g., Agâº, Zn²âº, Cu²âº) can bind to thiol groups (-SH) in enzyme active sites, inhibiting their catalytic activity. They can also displace essential metal cofactors in metalloenzymes, disrupting critical metabolic processes like respiration [15].

- ROS-Mediated Damage: As noted, ROS directly oxidize amino acid side chains in proteins, leading to misfolding, loss of function, and aggregation. This widespread protein damage contributes significantly to the lethality of oxidative stress [20] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Antimicrobial Composite Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HAp) [15] | Biocompatible ceramic matrix for metal nanoparticle doping. | High surface area, excellent biocompatibility, capacity for ion exchange. |

| Metal Salt Precursors (e.g., AgNO₃, Zn(NO₃)₂, Cu(NO₃)₂) [15] | Starting materials for synthesizing metal nanoparticles within a composite matrix. | High purity, water-soluble, decomposes to metal oxides or elemental metals upon calcination. |

| Polymer Matrices (PLA, TPU) [4] | Base material for creating 3D-printable antimicrobial filaments. | Thermoplastic processability, compatibility with nanofillers, defined rheological properties. |

| Live/Dead Bacterial Viability Kit [18] | Fluorescent staining for quantifying live vs. dead cells in planktonic or biofilm states. | Typically contains SYTO 9 (green, live) and propidium iodide (red, dead) stains. |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Probes (e.g., DCFH-DA, DHE) [20] | Chemical probes for detecting and quantifying intracellular ROS generation in microbes. | Cell-permeable, become fluorescent upon oxidation by specific ROS. |

| Nutrient Agar/Broth (e.g., BHI, TSB) [18] | Culture medium for growing and maintaining test microbial strains. | Supports robust microbial growth, standardized for reproducible assays. |

| SR-3737 | SR-3737|JNK3 Inhibitor|For Research Use | SR-3737 is a potent JNK3 inhibitor for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| ST-148 | ST-148, CAS:400863-77-6, MF:C21H19N5OS2, MW:421.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data and methodologies presented here underscore that advanced antimicrobial polymer composites exert their effects through a multi-target mechanism of action. Key strategies include the physical disruption of microbial membranes, the induction of lethal oxidative stress via ROS, and the inactivation of essential proteins and enzymes. The efficacy of a composite is highly dependent on its formulation—the choice of polymer matrix, the type and concentration of antimicrobial nanofiller (e.g., Ag, ZnO, Cu), and the resulting material properties. While materials like silver-doped hydroxyapatite show impressive zones of inhibition, and zinc oxide composites effectively disrupt biofilms, a critical challenge remains in ensuring that these properties are retained after manufacturing processes, such as 3D printing. Future research should focus on optimizing nanofiller distribution and surface availability, developing standardized testing protocols that mimic real-world conditions, and thoroughly investigating the long-term stability and potential for resistance emergence against these physical and chemical modes of action.

Within the field of antimicrobial materials research, polymer composites have emerged as a frontline defense against microbial contamination in healthcare, food packaging, and public settings. The central thesis of this guide is that the antimicrobial efficacy of these composites is not universal but is highly dependent on the composite's mechanism of action and the structural characteristics of the target microorganism. A critical understanding of this spectrum of activity is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to design targeted and effective antimicrobial solutions. This guide provides a structured comparison of various polymer composites, supported by experimental data, to elucidate their differential performance against Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, enveloped viruses, and fungi.

Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Polymer Composites

The following tables summarize the efficacy of various polymer composites against different microbial classes, based on experimental data from recent research.

Table 1: Efficacy of Metal- and Natural Polymer-Based Composites Against Bacteria and Fungi

| Composite Material | Active Agent | Microbial Target | Efficacy & Key Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA-Copper Composite [23] | Copper microparticles | E. coli (Gram-negative), S. aureus (Gram-positive) | 99.5% reduction after 20 min; effective against both types. | 3D-printed sheets tested over time intervals (5 min - 24 h). |

| Chitosan [24] | Cationic polymer | Broad-spectrum (Bacteria & Fungi) | Stronger activity against Gram-negative bacteria; also effective against fungi. | Analysis of polymer mechanisms and microbial cell wall interactions. |

| SEBS/ZnPT Composite [25] | Zinc Pyrithione (ZnPT) | E. coli, S. aureus | 99.9% reduction of E. coli; 99.7% reduction of S. aureus. | Modified thermoplastic elastomers against bacterial populations. |

| Ag/HAp Composite [15] | Silver Nanoparticles (5%) | E. coli, S. aureus | Inhibition zones: 19.7 mm (E. coli), 13.8 mm (S. aureus). | Disc diffusion test on agar surface. |

| Chitosan Acetate [24] | Cationic polymer | S. aureus (Gram-positive), Salmonella spp. (Gram-negative) | More susceptible to Gram-positive bacteria. | Film-based antimicrobial activity tests. |

Table 2: Efficacy of Composites Against Viruses and Fungi

| Composite Material | Active Agent | Microbial Target | Efficacy & Key Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR Disinfectant [26] | PHMB, EDTA, Surfactants | Enveloped Viruses (FCV surrogate), C. auris | Superior reduction in wet (30s/5min) and dry (24h) states vs. comparators. | Surface disinfection test on silicone discs. |

| SEBS/AgNano Composite [25] | Silver Nanoparticles | E. coli, S. aureus, A. niger, C. albicans | 99.7% (E. coli), 95.5% (S. aureus) reduction; zone of inhibition for fungi. | Modified thermoplastic elastomers. |

| TPU/Cu Composite [27] | Copper Particles (1 wt%) | S. aureus, E. coli | Hindered growth and inhibited biofilm formation. | Melt-blended composite films. |

| Wood Plastic/Copper-Zinc [23] | Copper-Zinc Alloy | E. coli | 90.43% reduction in growth. | Reinforced composite material. |

Mechanisms of Action and Microbial Structural Determinants

The differential efficacy outlined in the tables above is rooted in the distinct mechanisms of action of the composites and the structural biology of the microbes.

Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Polymer Composites

- Contact-Killing (Cationic Polymers): Polymers with positively charged functional groups (e.g., chitosan's amine groups, quaternary ammonium compounds) interact electrostatically with negatively charged microbial membranes [1] [24]. This attraction can lead to membrane disruption, leakage of cellular contents, and cell death. The "phospholipid sponge effect" describes how cationic surfaces can extract lipids from the membrane, causing its breakdown [1].

- Metal Ion Release: Composites incorporating metal ions like silver (Agâº), copper (Cu²âº), or zinc (Zn²âº) exert their effects through the release of these ions [23] [25] [27]. The mechanisms include:

- Biocide-Releasing Systems: In these systems, the polymer matrix acts as a reservoir for antimicrobial agents (e.g., essential oils, organic acids, antibiotics), which are released over time to kill surrounding microbes [1] [5]. The release kinetics are critical for long-term efficacy.

Microbial Structures and Susceptibility

The varying susceptibility of different microbes to these mechanisms is primarily dictated by their surface structures, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram Title: Microbial Structures and Primary Susceptibility

- Gram-positive Bacteria: Their thick, porous peptidoglycan layer, studded with anionic teichoic acids, creates a highly negative surface. This makes them particularly susceptible to cationic polymers (e.g., chitosan) which can easily bind and disrupt the cell membrane [24].

- Gram-negative Bacteria: The presence of a complex outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides (LPS) acts as a formidable permeability barrier. This structure can reduce the efficacy of some large molecular agents, making these bacteria generally less susceptible to cationic polymers alone than Gram-positive species. However, they remain highly vulnerable to metal ions (e.g., Agâº, Cu²âº) which can generate ROS and damage internal components [24].

- Enveloped Viruses: Viruses such as coronaviruses and influenza possess a lipid bilayer envelope derived from the host cell. This envelope is highly susceptible to detergents, surfactants, and membrane-disrupting agents (e.g., PHMB, some surfactants in the VR disinfectant), which can disintegrate the envelope and render the virus non-infectious [1] [28]. Non-enveloped viruses, lacking this layer, are typically more resistant to such physical disruption.

- Fungi: Fungal cells, such as Candida species, have a complex and rigid cell wall containing chitin, β-glucans, and mannoproteins [29]. This structure can be a challenge for some antimicrobials, but metal nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Zn) and certain cationic polymers have demonstrated potent antifungal activity by disrupting the cell membrane and inducing oxidative stress [29] [15].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and validate the comparative data, this section details standard experimental protocols used in the cited research.

Protocol 1: Assessing Antibacterial Activity via Time-Kill Assays

This method is used to determine the rate and extent of antimicrobial activity over time, as seen in the evaluation of PLA-copper composites [23].

- Sample Preparation: Inoculate the surface of the antimicrobial material (e.g., a 3D-printed composite sheet) and a control surface (e.g., steel or plastic) with a standardized microbial suspension (~10ⶠCFU/mL for bacteria).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the inoculated surfaces under controlled conditions. Sample at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, 1 h, 8 h, 24 h).

- Neutralization and Elution: At each time point, transfer the sample to a neutralizing solution (e.g., D/E neutralizing broth) to stop antimicrobial action. Sonicate or vortex to elute viable microorganisms.

- Enumeration: Perform serial dilutions of the eluent and plate on appropriate agar media. Count the Colony Forming Units (CFU) after incubation.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage reduction in microbial load compared to the control at time zero.

Protocol 2: Disc Diffusion Assay for Screening Efficacy

This qualitative and semi-quantitative method is widely used for initial screening, as employed in testing hydroxyapatite-based composites [15].

- Agar Preparation: Pour a standardized nutrient agar medium into Petri dishes and allow it to solidify.

- Inoculation: Evenly spread a standardized suspension of the test microorganism over the surface of the agar.

- Application of Test Material: Impregnate sterile filter paper discs with the antimicrobial composite solution or place pre-formed composite discs on the inoculated agar surface.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate the plates at the optimal temperature for the test microorganism for a specified period (e.g., 24-48 h). Measure the diameter of the clear zone of inhibition (including the disc) in millimeters.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Dry-State Residual Antimicrobial Activity

This protocol is crucial for assessing long-lasting efficacy on surfaces, a key feature of the VR disinfectant [26].

- Surface Coating: Apply the antimicrobial solution (e.g., polymer coating or disinfectant) to a relevant surface (e.g., silicone disc) and allow it to dry completely under ambient conditions for a set period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Challenge Inoculation: After the drying period, inoculate the pre-treated surface with the test pathogen.

- Dry Contact: Allow the inoculum on the coated surface to dry completely.

- Recovery and Enumeration: After the desired contact time, recover the microorganisms by sonicating the surface in a neutralizer/saline solution. Quantify the viable microbes using standard plating techniques and compare to controls (untreated surfaces).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Antimicrobial Composite Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A biodegradable thermoplastic polymer frequently used as a base matrix in fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D printing of antimicrobial composites [23]. |

| Chitosan | A natural cationic biopolymer derived from chitin; serves as both a film-forming matrix and an active antimicrobial agent due to its positive charge [24] [5]. |

| Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs) | A class of cationic surfactants and polymers that provide contact-killing antimicrobial activity by disrupting microbial membranes [1]. |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial metallic nanoparticles that release Ag⺠ions, inducing oxidative stress and damaging cells [25] [15] [27]. |

| Copper Microparticles/Nanoparticles | Metallic additives with potent, broad-spectrum biocidal properties, often used to create self-disinfecting surfaces [23] [27]. |

| Polyhexamethylene Biguanide (PHMB) | A polymeric biguanide with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, known for its membrane-disrupting action and use in disinfectant formulations [26]. |

| D/E Neutralizing Broth | A growth medium containing neutralizers (e.g., lecithin, polysorbate) used to inactivate antimicrobial agents during testing, ensuring accurate microbial recovery in time-kill assays [26]. |

| Silicone Test Discs | Inert, non-porous substrates used as standardized surfaces for testing the dry-state and wet-state efficacy of disinfectants and antimicrobial coatings [26]. |

| Stattic | Stattic, CAS:19983-44-9, MF:C8H5NO4S, MW:211.20 g/mol |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone) For Research |

The efficacy of antimicrobial polymer composites is intrinsically linked to a complex interplay between their mechanism of action and the structural vulnerabilities of the target microorganism. Key conclusions from this comparative analysis are:

- Metal-ion based composites (e.g., Ag/HAp, PLA/Copper) demonstrate broad-spectrum and potent activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with performance highly dependent on concentration and composition.

- Cationic polymers (e.g., Chitosan, PHMB) show high efficacy but their activity can be differentially influenced by the cell wall structure of bacteria, often showing a preference for Gram-positive strains, while also being highly effective against enveloped viruses.

- Composite performance is context-dependent. The material's application method (e.g., 3D printing, coating), the test environment (wet vs. dry state), and the presence of organic matter can significantly influence the reported efficacy.

Therefore, the selection or development of an antimicrobial polymer composite for a specific application must be guided by a clear understanding of the primary microbial threat and the environment in which the material will function. Future research should continue to elucidate structure-activity relationships and develop standardized testing protocols that better simulate real-world conditions.

The ESKAPE pathogens—Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species—represent a group of bacteria that collectively "escape" the biocidal action of conventional antibiotics and are the leading cause of life-threatening nosocomial infections worldwide [30] [31]. These pathogens are listed as critical or high-priority on the World Health Organization's (WHO) priority pathogen list due to their extensive multi-drug resistance (MDR) profiles and ability to cause infections in immunocompromised patients [32] [31]. The treatment of patients with ESKAPE infections presents substantial challenges for healthcare providers due to limited therapeutic options, increased morbidity and mortality, and elevated healthcare costs [33]. A recent study at a tertiary care hospital revealed that 90.5% of ESKAPE infections were multidrug-resistant, with particularly high resistance rates observed in A. baumannii (95.6% MDR) and K. pneumoniae (83.8% MDR) [33]. This comprehensive review examines the current landscape of ESKAPE pathogens, their resistance mechanisms, and the promising potential of antimicrobial polymer composites as innovative therapeutic strategies.

Global Prevalence and Clinical Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens

ESKAPE pathogens are formidable adversaries in healthcare settings, responsible for a significant proportion of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) and exhibiting alarming resistance patterns to first-line and last-resort antimicrobial agents. The clinical impact of these pathogens is substantial, with patients infected by MDR ESKAPE strains showing significantly increased 30-day mortality rates [33]. Risk factors for MDR ESKAPE infections include advanced age, ICU admission, and invasive procedures such as indwelling urinary catheters (IUC), central venous catheters (CVC), and mechanical ventilation (MV) [33].

Table 1: Global Prevalence and Resistance Profiles of ESKAPE Pathogens

| Pathogen | Gram Stain | Prevalence Trends | Key Resistance Markers | Noted Resistance in Clinical Isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | Positive | Increasing VRE rates | Vancomycin resistance (vanA) | 40% MDR; 20% vancomycin resistance [33] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Positive | MRSA prevalence concerning | Methicillin resistance (mecA) | 68.2% MDR; 85% oxacillin resistance [33] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Negative | ESBL and CRKP spreading | Carbapenem resistance (KPC, NDM) | 83.8% MDR; >90% extended-spectrum cephalosporin resistance [33] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Negative | Extremely drug-resistant | Carbapenem resistance (OXA) | 95.6% MDR; >95% carbapenem resistance [33] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Negative | Difficult-to-treat resistance | Multidrug efflux pumps | 22.6% MDR; 30% carbapenem resistance [33] |

| Enterobacter spp. | Negative | Emerging concern in UTIs | AmpC β-lactamases | Limited quantitative data in recent studies [30] [34] |

Table 2: Documented Risk Factors for MDR ESKAPE Infections

| Risk Factor Category | Specific Factors | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Odds Ratio/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | Age ≥65 years | p<0.035 | Increased MDR incidence [33] |

| Hospital Department | ICU admission | p<0.001 | 90.6% MDR rate [33] |

| Invasive Procedures | Indwelling Urinary Catheter (IUC) | p<0.001 | 86.8% MDR with IUC [33] |

| Invasive Procedures | Central Venous Catheter (CVC) | p<0.000 | 93.2% MDR with CVC [33] |

| Invasive Procedures | Mechanical Ventilation (MV) | p<0.008 | 91.6% MDR with MV [33] |

| Clinical History | Prior antibiotic use (1 month) | p=0.216 | 83.9% MDR with prior use [33] |

The resistance patterns observed in ESKAPE pathogens are not limited to clinical settings. Recent evidence indicates that antibiotic-resistant ESKAPE strains can be isolated from environmental reservoirs such as surface water, wastewater, food, and soil, posing potential risks for community-acquired infections [34]. This environmental persistence further complicates containment strategies and underscores the need for innovative approaches to combat these pathogens.

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens

ESKAPE pathogens employ diverse and sophisticated mechanisms to circumvent the activity of antimicrobial agents. These resistance strategies can be categorized as either intrinsic (naturally occurring) or acquired (through mutation or horizontal gene transfer), and many pathogens utilize multiple mechanisms simultaneously to enhance their survival capabilities [31].

Molecular Resistance Strategies

The primary resistance mechanisms employed by ESKAPE pathogens include:

Enzymatic Inactivation: Production of enzymes that modify or destroy antibiotics. β-lactamases represent the most prevalent mechanism, with extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (e.g., NDM-1, OXA-48, KPC) conferring resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics [31]. Other inactivating enzymes include chloramphenicol acetyltransferases (CATs) and aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes [31].

Efflux Pump Systems: Transmembrane proteins that actively export antibiotics from the bacterial cell, reducing intracellular concentrations to subtherapeutic levels. These systems include the resistance nodulation division (RND) superfamily in Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., AcrAB-TolC in E. coli, MexCD-OprJ in P. aeruginosa) and drug-specific pumps (e.g., TetA, TetL) in Gram-positive pathogens [31]. These pumps often have broad substrate specificity, contributing to multidrug resistance phenotypes [31].

Target Site Modification: Alteration of antibiotic binding sites through mutation or enzymatic modification. Examples include mutations in DNA gyrase (gyrA) and topoisomerase IV (parC) conferring fluoroquinolone resistance, ribosomal methylation (erm genes) conferring macrolide resistance, and acquisition of alternative, low-affinity penicillin-binding proteins (PBP2a in MRSA) [31].

Membrane Permeability Barriers: Reduction of antibiotic penetration through the bacterial cell envelope. Gram-negative bacteria achieve this through porin loss (e.g., OprD in P. aeruginosa) or changes in membrane lipopolysaccharide structure [31]. Gram-positive pathogens can modify membrane charge through mechanisms such as the multiple peptide resistance factor (MprF) in S. aureus, which increases positive charge and repels cationic antimicrobials like daptomycin [31].

Biofilm Formation: Development of structured microbial communities encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. Biofilms provide physical protection against antibiotics and host immune responses, with embedded bacteria exhibiting up to 1000-fold increased resistance compared to planktonic cells [21] [35]. Biofilms also facilitate horizontal gene transfer, accelerating the dissemination of resistance genes [21].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected relationship between various resistance mechanisms employed by ESKAPE pathogens:

Diagram 1: Resistance mechanisms in ESKAPE pathogens. Both intrinsic and acquired mechanisms contribute to multidrug resistance, with horizontal gene transfer facilitating the spread of resistance determinants.

Antimicrobial Polymer Composites: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy

With traditional antibiotic development stagnating—only one new antibiotic class (daptomycin) has been approved since 2003—researchers are increasingly exploring alternative approaches to combat ESKAPE pathogens [31]. Antimicrobial polymer composites represent a promising strategy that can either directly kill pathogens or prevent their adhesion and colonization on surfaces [32] [35] [36].

Composition and Classification

Antimicrobial polymer composites typically consist of a base polymer matrix integrated with active antimicrobial agents. These materials can be broadly categorized based on their composition and mechanism of action:

Table 3: Classification of Antimicrobial Polymer Composites

| Composite Type | Base Polymer Examples | Antimicrobial Agents | Primary Mechanisms | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Nanocomposites | Chitosan, Polyvinyl alcohol, Cellulose derivatives | Silver, Zinc oxide, Copper oxide, Titanium dioxide nanoparticles | Metal ion release, ROS generation, membrane disruption | Medical device coatings, wound dressings, textiles [21] [15] [35] |

| Peptide-Loaded Systems | Polycarbonate, Polylactic acid, Polycaprolactone | Antimicrobial peptides (LL-37, magainin, nisin), synthetic AMP mimics | Membrane permeabilization, target disruption | Topical formulations, implant coatings, drug delivery systems [36] |

| Cationic Polymers | Quaternary ammonium compounds, Guanidine-based polymers | Inherently antimicrobial polymers | Membrane disruption through electrostatic interactions | Surface coatings, disinfectants, water treatment [32] [36] |

| Carbon-Based Composites | Thermoplastic elastomers, Polyurethane | Graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes | Physical damage, oxidative stress, electron transfer | Filtration systems, protective equipment, industrial surfaces [21] [35] |

Key Advantages Over Conventional Antibiotics

Polymer composites offer several distinct advantages for combating ESKAPE pathogens:

Multiple Simultaneous Mechanisms: Unlike most conventional antibiotics that target specific cellular processes, antimicrobial composites often employ multiple mechanisms simultaneously, making it more difficult for pathogens to develop resistance [36]. For example, silver nanoparticle composites can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupt membrane integrity, and interfere with cellular respiration concurrently [15] [35].

Reduced Resistance Development: The physical nature of many antimicrobial composite mechanisms (e.g., membrane disruption through cationic interactions) presents a higher evolutionary barrier for resistance development compared to single-target antibiotics [36].

Surface Modification Capabilities: Composites can be engineered as non-leaching contact-killing surfaces that prevent microbial adhesion and biofilm formation, particularly valuable for medical devices and hospital surfaces [35] [36].

Sustained Release Kinetics: Polymer matrices can be designed to provide controlled release of antimicrobial agents, maintaining effective concentrations at infection sites for extended periods while reducing systemic exposure [36].

Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Composites Against ESKAPE Pathogens

Recent research has demonstrated the significant potential of various composite formulations against ESKAPE pathogens. The following experimental data highlights the efficacy of different approaches:

Hydroxyapatite-Based Composites

A 2024 study systematically evaluated hydroxyapatite (HAp) composites incorporating metal nanoparticles for healthcare applications [15]. The researchers synthesized pure HAp and metal-doped variants (Cu/HAp, Zn/HAp, Ag/HAp) with weight ratios ranging from 0-15% using wet-impregnation assisted by ultrasonication, followed by calcination at 600°C for 2 hours. Antimicrobial efficacy was assessed using a modified disc diffusion method against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens.

Table 4: Efficacy of Hydroxyapatite-Based Composites Against ESKAPE Pathogens

| Composite Formulation | Inhibition Zone vs. S. aureus (mm) | Inhibition Zone vs. E. coli (mm) | Inhibition Zone vs. P. aeruginosa (mm) | Optimal Concentration | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure HAp | <5 | <5 | <5 | N/A | Minimal inherent antimicrobial activity |

| 5% Cu/HAp | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.5 | 5-10% | Moderate broad-spectrum activity |

| 5% Zn/HAp | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 5-10% | Improved Gram-positive targeting |

| 5% Ag/HAp | 13.8 ± 0.5 | 19.7 ± 0.6 | 15.2 ± 0.4 | 5% | Superior broad-spectrum efficacy |

| 10% Ag/HAp | 14.1 ± 0.6 | 20.3 ± 0.7 | 15.8 ± 0.5 | 5% | Marginally improved over 5% |

| Tetracycline (control) | 18.5 ± 0.7 | 22.1 ± 0.8 | 16.3 ± 0.6 | 30 μg/disc | Reference antibiotic |

The exceptional performance of Ag/HAp composites, particularly at 5% concentration, demonstrates an optimal balance between antimicrobial efficacy and material properties. Silver nanoparticles release Ag⺠ions that disrupt microbial membrane integrity, interfere with respiratory enzymes, and generate reactive oxygen species [15]. The hydroxyapatite matrix serves as a biocompatible carrier that facilitates controlled release and enhances stability.

Biopolymer Nanocomposites

Advanced biopolymer nanocomposites utilizing natural and synthetic polymers functionalized with nanofillers have shown promising results against MDR ESKAPE pathogens [21]. These systems leverage the inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability of biopolymers while enhancing their antimicrobial properties through chemical modifications (sulfation, carboxymethylation, amination) and nanofiller incorporation.

The following experimental workflow illustrates the development and evaluation process for antimicrobial polymer composites:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for developing antimicrobial polymer composites, from material synthesis to application development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Research on antimicrobial composites against ESKAPE pathogens requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit outlines critical components for investigating polymer-based antimicrobial strategies:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Antimicrobial Composite Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Chitosan, Alginate, Cellulose derivatives, Polyvinyl alcohol, Polycaprolactone | Biocompatible backbone for composite formation | Molecular weight, degree of deacetylation (chitosan), viscosity, modification potential [21] |

| Inorganic Fillers | Silver nanoparticles, Zinc oxide, Copper oxide, Graphene oxide, Metal-organic frameworks | Primary antimicrobial activity enhancement | Particle size, surface area, concentration, dispersion stability [21] [15] [35] |

| Chemical Modifiers | Sulfating agents, Carboxymethylation reagents, Amination compounds | Enhance antimicrobial potency and material properties | Degree of substitution, reaction efficiency, impact on biodegradability [21] |

| Characterization Techniques | XRD, SEM/TEM, XPS, FTIR, Particle size analysis | Material structure, morphology, and composition analysis | Crystallinity, elemental composition, surface chemistry, size distribution [15] |

| Antimicrobial Assays | Disc diffusion, Broth microdilution (MIC/MBC), Time-kill kinetics, Biofilm assays | Efficacy assessment against ESKAPE pathogens | Standardization according to CLSI/EUCAST guidelines, growth media, inoculation density [15] |

| Cytotoxicity Evaluation | MTT assay, Live/dead staining, Hemolysis testing | Safety and biocompatibility assessment | Cell line selection, exposure time, relevance to application site [15] [36] |

| UC-112 | UC-112, CAS:383392-66-3, MF:C22H24N2O2, MW:348.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| UCK2 Inhibitor-2 | UCK2 Inhibitor-2, CAS:866842-71-9, MF:C28H23N3O4S, MW:497.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

For researchers evaluating antimicrobial composites against ESKAPE pathogens, the following standardized protocols provide reproducible methodology:

Protocol 1: Disc Diffusion Assay for Antimicrobial Activity Assessment

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow ESKAPE pathogen isolates in appropriate broth (e.g., Mueller-Hinton) to logarithmic phase (0.5 McFarland standard, ~1.5 × 10⸠CFU/mL) [15].

- Inoculation: Evenly spread bacterial suspension on Mueller-Hinton agar plates using sterile swabs.

- Sample Application: Aseptically place composite-incorporated discs (6 mm diameter) on inoculated agar surfaces.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 35°C for 16-20 hours appropriate for each pathogen.

- Measurement: Measure inhibition zone diameters (including disc diameter) using digital calipers. Perform triplicate measurements for each test condition.

- Controls: Include appropriate positive (standard antibiotics) and negative (polymer-only) controls.

Protocol 2: Broth Microdilution for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

- Composite Preparation: Prepare serial two-fold dilutions of antimicrobial composites in appropriate broth medium in 96-well microtiter plates.

- Inoculation: Add standardized bacterial inoculum (5 × 10ⵠCFU/mL final concentration) to each well.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 35°C for 16-20 hours without shaking.

- Endpoint Determination: MIC is defined as the lowest composite concentration showing no visible growth. Confirm results using resazurin staining or optical density measurements (620 nm).

- Quality Control: Include growth control (inoculated medium), sterility control (uninoculated medium), and reference strain controls.

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance among ESKAPE pathogens demands innovative approaches that extend beyond traditional antibiotic development. Antimicrobial polymer composites represent a promising frontier in this battle, offering multiple mechanisms of action, reduced potential for resistance development, and versatile application formats. Current research demonstrates particularly promising results with metal nanoparticle-functionalized composites, especially silver-doped hydroxyapatite systems showing inhibition zones of 19.7 mm and 13.8 mm against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively [15].

Future research directions should focus on optimizing composite formulations for specific clinical applications, enhancing the durability of antimicrobial activity, and addressing potential toxicity concerns through comprehensive in vivo studies. Additionally, combination approaches integrating polymer composites with conventional antibiotics, bacteriophages, or other novel therapeutics may provide synergistic effects against the most recalcitrant ESKAPE infections [31] [36]. As research advances, antimicrobial polymer composites hold substantial potential to become invaluable tools in our ongoing efforts to overcome multidrug resistance and improve outcomes for patients with serious bacterial infections.

From Lab to Application: Fabrication Techniques and Real-World Implementations

The escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance has intensified the search for innovative materials that can effectively inhibit pathogenic microorganisms. Within this landscape, polymer composites integrated with antimicrobial additives have emerged as a front-line solution across biomedical, packaging, and environmental applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of three principal categories of antimicrobial additives: metal/metal oxides, organic compounds, and advanced hybrid systems. By synthesizing current experimental data on their efficacy, mechanisms, and practical performance, this analysis aims to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the selection and development of next-generation antimicrobial materials. The focus on quantitative outcomes and detailed methodologies ensures a practical, evidence-based resource for advancing research in antimicrobial polymer composites.

Comparative Antimicrobial Performance of Additive Classes

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Antimicrobial Efficacy Across Additive Classes

| Additive Class | Specific Material/Composite | Target Microorganisms | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|