Antimicrobial Polymers in Biomedicine: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive review of antimicrobial polymers (APs) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Antimicrobial Polymers in Biomedicine: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of antimicrobial polymers (APs) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of APs, including their classification and mechanisms of action against multidrug-resistant threats like the ESKAPE pathogens. The scope covers methodological advances in material design, from bio-based polymers and nanostructures to novel non-amphiphilic systems, detailing their applications in drug delivery, medical implants, and tissue engineering. It further addresses key challenges in biocompatibility, selectivity, and industrial scalability, while offering comparative analyses of material performance and translational potential to guide future research and clinical application.

Understanding Antimicrobial Polymers: Definitions, Mechanisms, and the Fight Against Drug-Resistant Infections

Antimicrobial polymers represent a sophisticated class of functional materials engineered to inhibit or eliminate pathogenic microorganisms. These materials have gained significant importance in biomedical engineering as alternatives to conventional antibiotics, particularly in addressing the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance [1]. The classification system for these polymers is fundamentally structured around three distinct categories based on their mechanism of action: biocidal polymers, polymeric biocides, and biocide-releasing systems [2]. This taxonomy is crucial for researchers and product development professionals as it directly correlates with application performance, regulatory pathways, and biological safety profiles.

The global market for antimicrobial biomedical polymers has demonstrated substantial growth, reaching approximately $1.2 billion in 2022 with projections indicating expansion to $2.1 billion by 2028, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 8.7% [3]. This market trajectory underscores the increasing importance of these materials across medical devices, wound dressings, and pharmaceutical applications. Within this landscape, a precise understanding of the classification framework enables targeted development of antimicrobial solutions with optimized efficacy and minimal toxicity.

Table 1: Fundamental Categories of Antimicrobial Polymers

| Category | Structural Principle | Mechanism of Action | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocidal Polymers | Antimicrobial activity emerges from the entire macromolecular structure [2] | Membrane disruption via electrostatic interactions and insertion [2] [4] | Selective toxicity, non-leaching, resistance prevention |

| Polymeric Biocides | Biocidal groups attached to polymer backbone as repeating units [1] [2] | Dependent on tethered biocidal groups (e.g., quaternary ammonium) [5] | Activity potentially reduced compared to monomers |

| Biocide-Releasing Systems | Polymer matrix acts as carrier for antimicrobial agents [1] | Controlled release of encapsulated biocides (e.g., antibiotics, metal ions) [1] [3] | High initial efficacy, potential for reservoir depletion |

Systematic Classification of Antimicrobial Polymers

Biocidal Polymers

Biocidal polymers represent materials whose antimicrobial activity is an emergent property of the entire macromolecular architecture rather than individual functional groups [2]. These polymers are designed to mimic the mechanism of natural host defense peptides (HDPs), which provide broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity through membrane disruption without inducing significant resistance [4]. The structural hallmarks of these biomimetic polymers include: (1) cationic charge density for electrostatic attraction to negatively charged bacterial membranes, (2) optimal amphiphilic balance to facilitate membrane integration, and (3) precisely tuned molecular weight to enable multivalent interactions with microbial cells [4].

The mechanism of action for biocidal polymers primarily involves initial electrostatic attraction to anionic components of bacterial membranes, followed by hydrophobic insertion into the lipid bilayer, ultimately leading to membrane disruption and cell lysis [2] [4]. This non-specific mechanism presents a high barrier to resistance development compared to traditional antibiotics that target specific metabolic pathways. Research has demonstrated that systematic optimization of copolymer composition, chain length, hydrophobicity, and cationic charge can yield materials with exceptional broad-spectrum activity and high biocompatibility [4].

Polymeric Biocides

Polymeric biocides constitute macromolecules where biocidal functional groups are covalently incorporated as repeating units along the polymer backbone [1] [2]. Unlike biocidal polymers where activity emerges from the macromolecular structure, polymeric biocides essentially function as multiple interconnected biocides that ideally retain the mechanism of action of their monomeric counterparts [2]. Common examples include polymers functionalized with quaternary ammonium compounds, N-halamines, or antimicrobial peptides [5].

A significant consideration in designing polymeric biocides is that polymerization does not always preserve antimicrobial activity. Steric hindrance from the polymer backbone or reduced accessibility to biocidal groups can diminish efficacy compared to monomeric analogues [2]. For instance, while quaternary ammonium compounds maintain their membrane-disrupting capability when polymerized, some antibiotics lose activity when tethered via non-cleavable bonds [2]. Successful implementation requires careful structural design to ensure biocidal groups remain accessible to microbial targets.

Biocide-Releasing Systems

Biocide-releasing systems utilize polymers as reservoirs or matrices for antimicrobial agents that are released into the surrounding environment upon contact with moisture or specific stimuli [1]. These systems provide high local concentrations of antimicrobials at the infection site and include formulations such as polymer micelles, vesicles, nanoparticles, and hydrogels [1]. Common released agents include antibiotics, silver ions, zinc compounds, and natural antimicrobials [3].

These systems offer the advantage of rapid and potent antimicrobial action but face challenges related to finite reservoir capacity and potential environmental contamination from released biocides [2]. Recent advances have focused on developing "smart" release mechanisms triggered by environmental stimuli such as pH changes, enzyme presence, or bacterial metabolites, enabling targeted antimicrobial delivery only when needed [3]. This approach extends functional lifetime while minimizing unnecessary biocide release that could contribute to resistance development.

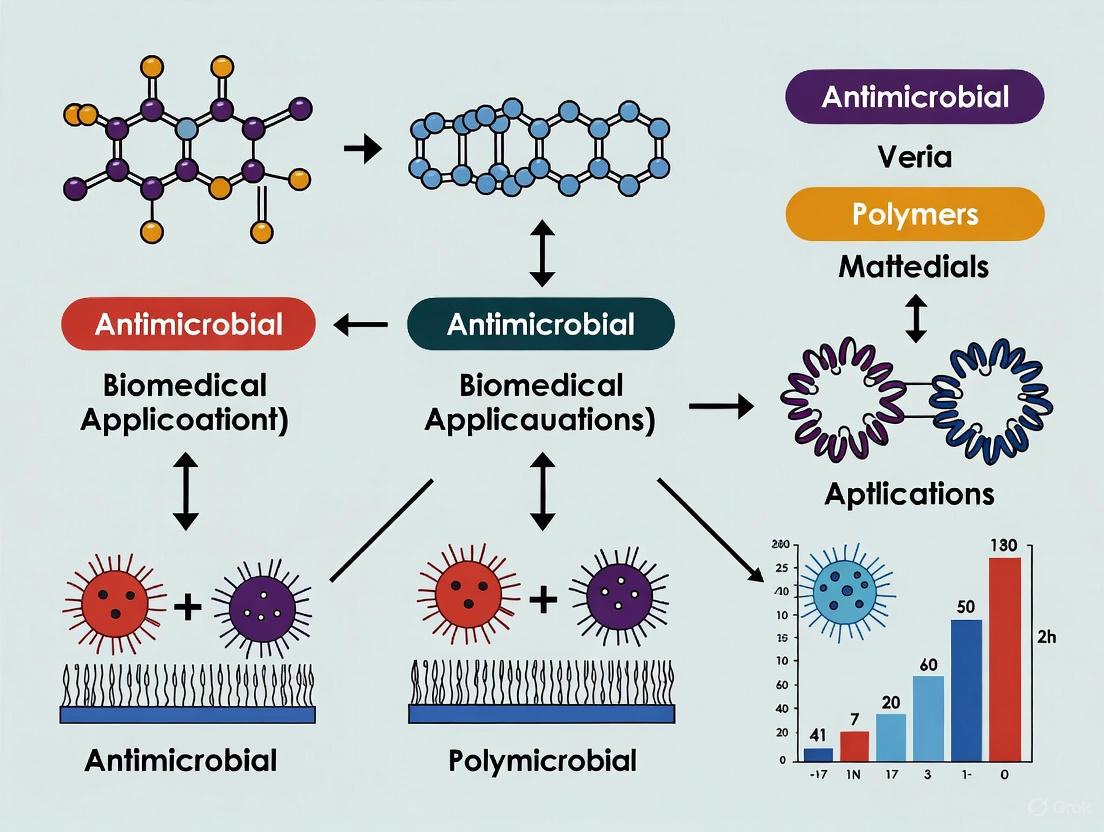

Diagram 1: Classification framework for antimicrobial polymers showing three primary categories and their fundamental characteristics.

Quantitative Analysis and Structure-Activity Relationships

The biological performance of antimicrobial polymers is governed by precise structure-activity relationships that balance efficacy against microorganisms with safety toward host cells. Key parameters include cationic charge density, hydrophobic content, molecular weight, and architectural topology [4]. Quantitative metrics such as minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) provide standardized measurements for comparing antimicrobial efficacy across different polymer systems.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Antimicrobial Polymer Classes

| Polymer Class | Representative Structure | MIC Range (μg/mL) | Hemolytic Concentration (HC50, μg/mL) | Therapeutic Index (HC50/MIC) | Primary Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocidal Polymers | Poly(methacrylate) with chlorhexidine-like side groups [2] | 1-25 [4] | >1000 [4] | >40 [4] | Broad-spectrum (Gram+/Gram-) |

| Polymeric Biocides | Quaternary ammonium-functionalized polymers [5] | 5-100 [5] | 100-500 [5] | 2-20 [5] | Gram-positive bacteria |

| Biocide-Releasing Systems | Silver nanoparticle-impregnated polymers [3] | 0.1-50 [3] | >200 [3] | >4 [3] | Broad-spectrum (bacteria, fungi) |

| Antimicrobial Peptide Mimetics | β-peptides, peptoids [4] | 2-30 [4] | 100-2000 [4] | 10-100 [4] | Multidrug-resistant pathogens |

The therapeutic index (typically calculated as HC50/MIC) represents a crucial parameter for evaluating the selectivity of antimicrobial polymers, with higher values indicating greater selectivity for microbial cells over mammalian cells [4]. Biocidal polymers often demonstrate superior therapeutic indices due to their biomimetic mechanisms that exploit structural differences between bacterial and mammalian membranes [4]. This selectivity stems from the higher negative charge density and distinct lipid composition of bacterial membranes compared to the neutral cholesterol-rich mammalian cell membranes.

Experimental Protocols and Characterization Methods

Protocol 1: Evaluation of Antimicrobial Efficacy

Objective: Determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of antimicrobial polymers against reference bacterial strains.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (for bacteria) or Sabouraud dextrose broth (for fungi)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Standard bacterial strains (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922)

- Sterile 96-well polypropylene microtiter plates with lids

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or sterile water for polymer dissolution

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions of test polymer in appropriate solvent (DMSO concentration should not exceed 1% in final assay)

- Perform twofold serial dilutions of polymer in culture medium across microtiter plate (100 μL/well)

- Prepare bacterial inoculum from fresh overnight culture, adjusting to ~5 × 10^5 CFU/mL in broth

- Add 100 μL bacterial inoculum to each well, resulting in final inoculum of ~5 × 10^4 CFU/mL

- Include growth control (inoculum without polymer) and sterility control (medium only)

- Incubate plates at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours without shaking

- Determine MIC as lowest polymer concentration showing no visible growth

- For MBC determination, subculture 10 μL from clear wells onto agar plates and incubate 24 hours

- Calculate MBC as lowest concentration achieving ≥99.9% reduction in viable count [1] [4]

Quality Control: Include reference antibiotics as positive controls; verify inoculum viability by plating serial dilutions.

Protocol 2: Cytotoxicity and Hemocompatibility Assessment

Objective: Evaluate cytotoxic effects of antimicrobial polymers on mammalian cells and hemolytic activity on erythrocytes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293, HaCaT, or primary fibroblasts)

- Complete cell culture medium with serum supplements

- Fresh human or animal erythrocytes in anticoagulant solution

- AlamarBlue, MTT, or similar metabolic activity indicator

- 96-well tissue culture-treated plates

- Centrifuge tubes and microplate reader

Procedure for Cytotoxicity Testing:

- Seed cells in 96-well plates at optimal density (typically 10,000 cells/well)

- Incubate 24 hours to allow cell attachment

- Prepare serial dilutions of test polymer in culture medium

- Replace medium with polymer solutions and incubate 24-48 hours

- Add viability indicator (e.g., 10% AlamarBlue) and incubate 2-4 hours

- Measure fluorescence/absorbance using microplate reader

- Calculate IC50 (concentration causing 50% reduction in viability) [4]

Procedure for Hemolysis Assay:

- Wash erythrocytes 3× with PBS and prepare 2% (v/v) suspension

- Mix erythrocyte suspension with equal volume polymer solutions

- Include negative control (PBS) and positive control (1% Triton X-100)

- Incubate 1 hour at 37°C with gentle mixing

- Centrifuge and measure hemoglobin release at 540 nm

- Calculate hemolysis percentage relative to positive control [4]

Interpretation: HC50 (concentration causing 50% hemolysis) should be significantly higher than MIC for selective antimicrobial action.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials Toolkit

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Antimicrobial Polymer Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Supplier Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Monomers | 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA), Quaternary ammonium methacrylates (QAMs) | Impart positive charge for electrostatic binding to microbial cells | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America; requires purification before polymerization |

| Hydrophobic Comonomers | Butyl methacrylate, Hexyl methacrylate, Styrene | Control amphiphilic balance for membrane insertion | Available in high purity from major chemical suppliers |

| Polymerization Reagents | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), Ammonium persulfate (APS) | Free-radical initiators for polymer synthesis | Recrystallize AIBN before use for optimal results |

| Microbiological Media | Mueller-Hinton broth, Tryptic Soy Agar | Standardized antimicrobial susceptibility testing | BD Diagnostics, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Reference Strains | S. aureus ATCC 29213, E. coli ATCC 25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | Quality control and standardized efficacy assessment | American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) |

| Cytotoxicity Assays | AlamarBlue, MTT, LDH assay kits | Assessment of mammalian cell compatibility | Thermo Fisher, Promega, Roche |

| Characterization Standards | Phosphate buffered saline, Dimethyl sulfoxide | Solvent and buffer systems for biological testing | Use tissue-culture grade for biological assays |

| SOD1-Derlin-1 inhibitor-1 | SOD1-Derlin-1 inhibitor-1, MF:C19H12Br2N4OS, MW:504.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Spiraprilat | Spiraprilat, CAS:83602-05-5, MF:C20H26N2O5S2, MW:438.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: Mechanism of membrane disruption by biocidal polymers showing sequential steps from initial attraction to final cell lysis.

Application Protocols for Biomedical Implementations

Protocol 3: Fabrication of Antimicrobial Coatings for Medical Devices

Objective: Apply durable antimicrobial polymer coatings to medical device surfaces to prevent biofilm formation.

Materials and Equipment:

- Plasma cleaner or corona treater for surface activation

- Polymer solution (1-5% w/v in appropriate solvent)

- Dip-coating apparatus or spray coater

- Curing oven or UV crosslinking system

- Medical-grade substrate (polyurethane, silicone, titanium)

- Characterization tools: contact angle goniometer, FTIR, SEM

Procedure:

- Clean substrate surfaces with sequential washes (detergent, water, ethanol)

- Activate surfaces using oxygen plasma (100-200 W, 1-5 minutes) to generate reactive groups

- Prepare antimicrobial polymer solution ensuring complete dissolution

- Apply coating using dip-coating (withdrawal speed 1-10 mm/s) or spray coating (multiple thin layers)

- Crosslink coating using appropriate method:

- Thermal curing: 60-120°C for 1-4 hours

- UV crosslinking: 254-365 nm, 5-30 minutes with photoinitiator

- Wash coated surfaces extensively to remove unbound polymer

- Characterize coating thickness, uniformity, and stability [3] [2]

Quality Assessment:

- Perform adhesion testing via tape test or cross-hatch method

- Evaluate coating durability in simulated physiological conditions

- Verify antimicrobial efficacy using ISO 22196 or similar standardized methods

Protocol 4: Formulation of Stimuli-Responsive Antimicrobial Hydrogels

Objective: Develop hydrogel systems that release antimicrobial agents in response to specific environmental triggers.

Materials and Reagents:

- Polymer matrix (e.g., polyethylene glycol, chitosan, hyaluronic acid)

- Crosslinker (e.g., N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide, genipin)

- Antimicrobial payload (antibiotics, silver nanoparticles, antimicrobial peptides)

- Stimuli-responsive monomers (pH-sensitive, enzyme-cleavable, thermoresponsive)

- Molding apparatus or 3D printing system

Procedure:

- Prepare polymer solution in appropriate buffer (2-10% w/v)

- Incorporate antimicrobial payload with gentle mixing

- Add crosslinking initiator system (chemical, photo-, or thermal)

- Transfer to mold or directly print into desired architecture

- Crosslink using appropriate conditions:

- Chemical crosslinking: 37°C for 2-24 hours

- Photocrosslinking: 365-405 nm, 5-15 minutes

- Wash hydrogel to remove unreacted components

- Characterize swelling ratio, mechanical properties, and release kinetics [1] [3]

Trigger Evaluation:

- pH-responsive: Measure release across pH 5.0-7.4

- Enzyme-responsive: Incubate with specific enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases)

- Bacterial metabolite-responsive: Test in presence of bacterial culture supernatants

Performance Validation: Assess antimicrobial activity against clinically relevant biofilm models using colony counting or metabolic activity assays.

The structured classification of antimicrobial polymers into biocidal polymers, polymeric biocides, and biocide-releasing systems provides a rational framework for research and development in this rapidly advancing field. Each category offers distinct advantages and limitations that dictate appropriate application contexts. Biocidal polymers demonstrate exceptional potential for long-term, resistance-resistant antimicrobial surfaces, while biocide-releasing systems offer potent, immediate protection in clinical scenarios where rapid microbial elimination is paramount.

Future directions in antimicrobial polymer development include creating multi-mechanistic systems that combine elements from multiple categories, advanced stimuli-responsive "smart" materials with precisely controlled activation, and hybrid natural-synthetic polymers that maximize biocompatibility while maintaining efficacy [6] [3]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on environmental sustainability is driving research toward biodegradable antimicrobial polymers that minimize ecological impact after use.

As antimicrobial resistance continues to pose grave challenges to global health, these functional polymeric materials represent increasingly vital tools in the multidisciplinary effort to develop effective anti-infective strategies. The standardized protocols and classification systems presented in this work provide researchers with a foundation for systematic development, characterization, and implementation of these advanced materials in biomedical applications.

Antimicrobial polymers (AMPs) represent a promising class of agents in the fight against multidrug-resistant pathogens. A primary mechanism by which these polymers exert their effects is through membrane disruption culminating in cell lysis. This process is initiated by electrostatic interactions between the cationic charges on the polymer and the anionic components of the microbial membrane [7] [8] [9]. This interaction is fundamental because bacterial membranes are rich in anionic phospholipids like phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and cardiolipin (CL), in contrast to the more neutral mammalian cell membranes that contain zwitterionic lipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and cholesterol [8]. This charge differential provides a basis for the selective targeting of microbial cells over host cells, a crucial advantage for therapeutic applications [10].

Following the initial electrostatic attraction, the amphipathic nature of many antimicrobial polymers—possessing both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions—enables their insertion into and subsequent disruption of the lipid bilayer [7] [9]. This disruption can follow several models, including the toroidal-pore, barrel-stave, and carpet models, all of which ultimately compromise the membrane's integrity [11] [8]. The loss of membrane integrity leads to uncontrolled ion flux, leakage of cellular contents, and eventually, cell lysis and death [7] [12]. Due to the physical nature of this mechanism, it presents a significantly higher barrier to the development of microbial resistance compared to conventional antibiotics that target specific proteins or biochemical pathways [13] [10].

Diagram: Mechanism of Microbial Membrane Disruption by Cationic Polymer

Quantitative Data on Antimicrobial Polymer Parameters

The antimicrobial efficacy of polymers is influenced by several key physicochemical parameters. The cationic charge density facilitates the initial binding to negatively charged microbial surfaces, while hydrophobicity promotes the subsequent insertion into the lipid bilayer [9] [13]. The molecular weight and architecture (e.g., linear, branched) further modulate this activity by influencing the polymer's ability to aggregate on and disrupt the membrane [9]. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is a standard metric used to quantify the potency of these antimicrobial agents, representing the lowest concentration that prevents visible microbial growth [10].

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Parameters Influencing Antimicrobial Polymer Activity

| Parameter | Structural Feature | Impact on Antimicrobial Activity | Optimal Range/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Charge | Quaternary ammonium, guanidinium groups | Enables electrostatic attraction to anionic microbial membranes; essential for initial binding [9] [14] | High charge density (e.g., polyethylenimine) [14] |

| Hydrophobicity | Alkyl chains, aromatic groups | Mediates insertion into the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer; enhances membrane disruption [7] [9] | Balanced to avoid excessive host cell toxicity [7] |

| Molecular Weight | Polymer chain length | Influences membrane penetration capability and multivalent interactions; high MW often correlates with higher activity [9] | Varies by polymer (e.g., high MW PEI is highly active) [9] |

| Amphipathicity | Presence of both cationic and hydrophobic regions | Allows for initial binding (via cationic face) followed by membrane integration (via hydrophobic face) [7] | Fundamental design principle for many synthetic AMPs [10] |

Table 2: Example Antimicrobial Polymers and Their Reported Efficacy

| Antimicrobial Polymer | Target Microorganism(s) | Reported Efficacy (MIC or % Reduction) | Primary Mechanism / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-alkyl-polyethylenimine | Broad-spectrum (airborne and waterborne bacteria, fungi) | ~100% cell inactivation when surface-immobilized [9] | Membrane disruption; nontoxic to mammalian cells [9] |

| Poly-ε-lysine | Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., B. subtilis) | Effective at low concentrations (specific MIC values not listed) [9] | Electrostatic interaction and cell wall penetration [9] |

| Chitosan | Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, Fungi | More effective on fungi than yeasts; greater effect on Gram-negative than Gram-positive bacteria [9] | Efficacy depends on pH, influencing electrostatic vs. chelating/hydrophobic interactions [9] |

| Polyguanidines | Broad-spectrum (greater on Gram-positive) | High efficacy with low toxicity; high water solubility [9] | Electrostatic forces; high MW polymers penetrate Gram-positive bacteria more effectively [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Bacterial Membrane Disruption via Cytoplasmic Leakage

This protocol details a method to evaluate the membrane disruption activity of antimicrobial polymers by measuring the release of intracellular components, such as nucleic acids, from bacterial cells.

1. Principle: Upon polymer-induced membrane damage, the cytoplasmic membrane becomes permeable, allowing intracellular materials like DNA and RNA to leak into the surrounding supernatant. The concentration of these nucleic acids can be quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm, providing a quantitative indicator of membrane disruption [11] [15].

2. Materials:

- Test Organism: Mid-logarithmic phase culture of target bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213).

- Antimicrobial Polymer Solution: Prepared in an appropriate solvent (e.g., deionized water, buffer).

- Control Solutions: A growth medium negative control and a positive disruption control (e.g., 1% Triton X-100).

- Spectrophotometer or microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

- Centrifuge and microcentrifuge tubes.

- Appropriate Buffer: e.g., Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or a low-absorbance growth medium.

3. Procedure: 1. Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain to mid-logarithmic phase in a suitable broth (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth). Harvest cells by centrifugation (e.g., 5,000 × g for 10 minutes). 2. Cell Washing: Wash the cell pellet twice with buffer to remove residual medium and extracellular nucleic acids. Resuspend the final pellet in buffer to an optical density (OD~600~) of approximately 0.5, representing ~10^8^ CFU/mL. 3. Polymer Exposure: In a microcentrifuge tube, mix 450 µL of the cell suspension with 50 µL of the antimicrobial polymer solution at the desired test concentration. Include negative (buffer only) and positive (detergent) controls. 4. Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 37°C with shaking for a predetermined time (e.g., 1-2 hours). 5. Pellet Removal: Centrifuge the samples at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes to pellet intact cells and cellular debris. 6. Supernatant Measurement: Carefully transfer 200 µL of the clear supernatant to a quartz cuvette or a UV-transparent microplate. Measure the absorbance at 260 nm (A~260~) against a buffer blank.

4. Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cytoplasmic leakage relative to the positive control (100% leakage) using the formula: [ \text{Leakage} = \frac{(A{sample} - A{negative control})}{(A{positive control} - A{negative control})} \times 100\% ] A significant increase in A~260~ in the polymer-treated samples compared to the negative control indicates substantial membrane disruption and cell lysis [15].

Protocol 2: Visualizing Membrane Damage using Fluorescent Dye Uptake

This protocol uses membrane-impermeant fluorescent dyes to visually confirm the loss of membrane integrity induced by antimicrobial polymers.

1. Principle: Propidium iodide (PI) is a fluorescent dye that is excluded from cells with intact membranes. When the cytoplasmic membrane is compromised, PI enters the cell, binds to nucleic acids, and exhibits a strong red fluorescence. This allows for the direct observation of damaged cells via fluorescence microscopy [11].

2. Materials:

- Bacterial Culture: Prepared as described in Protocol 1, step 1.

- Antimicrobial Polymer Solution.

- Propidium Iodide (PI) Stock Solution: (e.g., 1 mg/mL in water).

- Fluorescence Microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets for PI (excitation/emission ~535/617 nm).

- Microscope slides and coverslips.

- Incubator.

3. Procedure: 1. Cell Preparation: Prepare a bacterial cell suspension as in Protocol 1, steps 1-2. 2. Staining and Treatment: Mix 995 µL of cell suspension with 5 µL of PI stock solution. Add the antimicrobial polymer to the desired final concentration. 3. Incubation: Incubate the mixture in the dark at 37°C for 30-60 minutes. 4. Microscopy: Place a 10 µL aliquot of the stained cell suspension on a microscope slide, cover with a coverslip, and immediately observe under the fluorescence microscope. 5. Image Acquisition: Capture images using both brightfield and fluorescence channels. Cells with compromised membranes will show bright red fluorescence.

4. Data Analysis: Compare the number of fluorescent (PI-positive) cells in the polymer-treated sample to the negative control. A high percentage of PI-positive cells confirms that the polymer's mechanism of action involves permeabilization of the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane [11].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Membrane Disruption Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Membrane Disruption Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., Polyethylenimine, Chitosan) | Direct antimicrobial agents for mechanism of action studies. | Used as positive controls or benchmark materials; assess impact of MW and charge density [9] [14]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane-impermeant fluorescent nucleic acid stain. | Vital for fluorescence microscopy protocols to visualize loss of membrane integrity in treated cells [11]. |

| SYTOX Green / Other Viability Stains | Alternative membrane-impermeant dyes for flow cytometry or high-throughput screening. | Provides quantitative data on the percentage of permeabilized cells in a population [11]. |

| Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, SDS) | Positive control reagents for total lysis and membrane disruption. | Used to define 100% leakage or killing in cytotoxicity and leakage assays [12] [15]. |

| Luria-Bertani (LB) / Mueller-Hinton Broth | Standard media for culturing gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial test strains. | Ensures robust and reproducible cell growth prior to polymer exposure [15]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Buffer for washing and resuspending cells during experimental procedures. | Provides an isotonic and chemically defined environment, free from interfering substances [15]. |

| High-Pressure Homogenizer / Sonicator | Equipment for mechanical cell lysis. | Used as a reference method for total cell disruption and content release or in preparatory methods [12] [16]. |

| Srpin340 | Srpin340, CAS:218156-96-8, MF:C18H18F3N3O, MW:349.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stampidine | Stampidine, CAS:217178-62-6, MF:C20H23BrN3O8P, MW:544.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The ESKAPE pathogens—Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species—represent a critical group of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria that pose a severe threat to global health [17]. These pathogens are the leading cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), responsible for significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs worldwide [18]. In 2019 alone, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was associated with 4.95 million deaths globally, with ESKAPE pathogens being major contributors to this burden [19]. The clinical management of ESKAPE infections is complicated by their extensive antibiotic resistance profiles and ability to rapidly develop resistance to new antimicrobial agents, including those recently developed or still in clinical trials [20]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current research and detailed protocols for targeting these formidable bacterial threats within the context of developing innovative biomedical solutions, particularly antimicrobial polymers.

Current Threat Assessment and Resistance Profiles

ESKAPE pathogens demonstrate alarming resistance rates across healthcare settings. A seven-year retrospective study (2018-2024) at a tertiary hospital revealed that from 2,483 positive blood cultures, 3,724 ESKAPE pathogens were isolated [18]. S. aureus and K. pneumoniae predominated, particularly in intensive care and hematology wards [18]. The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) yielded the highest number of isolates, with S. aureus (25.7%), K. pneumoniae (25.6%), and A. baumannii (23.4%) being most prevalent [18].

Table 1: Prevalence and Key Resistance Profiles of ESKAPE Pathogens in Bloodstream Infections (2018-2024)

| Pathogen | No. of Isolates | ICU Prevalence (%) | Key Resistance Markers | Reserve Antibiotic Susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | 508 | 6.7 | Vancomycin Resistance (VRE) | Linezolid (preserved) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1284 | 25.7 | Methicillin Resistance (MRSA) | - |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 963 | 25.6 | ESBL Production, Carbapenemase Producers (including NDM+OXA-48) | Modern β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 461 | 23.4 | Near-universal Multidrug Resistance | Colistin (preserved) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 328 | - | Lower overall resistance | Colistin (preserved) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 182 | - | - | Carbapenem-susceptible |

Beyond clinical settings, ESKAPE pathogens are increasingly detected in aquatic environments, acting as reservoirs for resistance genes and posing transmission risks through water systems [21]. Anthropogenic activities such as farming and wastewater influx introduce these pathogens into water bodies, creating environmental reservoirs that contribute to the spread of AMR [21].

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance

ESKAPE pathogens employ sophisticated biochemical strategies to evade antimicrobial treatments, with Gram-negative species presenting additional challenges due to their complex cell envelope structure [17] [22].

Primary Resistance Mechanisms

Drug Uptake Limitations: The Gram-negative outer membrane, characterized by its asymmetric lipid bilayer with an outer leaflet of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), creates a formidable physicochemical barrier to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic antimicrobial compounds [22].

Enzymatic Drug Inactivation: Production of hydrolytic enzymes like β-lactamases that degrade critical antibiotics, particularly in Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens [17].

Efflux Pump Systems: Expression of broad-spectrum efflux pumps that actively transport antimicrobials out of bacterial cells [17] [22].

Target Site Modification: Alteration of antibiotic binding sites through mutation or enzymatic modification [17].

Biofilm Formation: Development of structured microbial communities encased in extracellular polymeric substances that provide collective protection against antibiotics and host defenses [23].

Table 2: Major Resistance Mechanisms in ESKAPE Pathogens

| Mechanism | Functional Category | Example in ESKAPE Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Membrane Permeability Barrier | Intrinsic Resistance | LPS structure in Gram-negative ESKAPE [22] |

| Antibiotic-Inactivating Enzymes | Acquired Resistance | β-lactamases in K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii [17] |

| Efflux Pump Systems | Intrinsic/Acquired Resistance | RND pumps in P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii [17] |

| Target Site Modification | Acquired Resistance | VanA gene cluster in E. faecium (VRE) [19] |

| Biofilm Formation | Adaptive Resistance | Polysaccharide matrix in S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [23] |

Biofilm-Associated Resistance

Biofilms represent a significant resistance mechanism wherein microbial communities develop within an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix [23]. The biofilm lifecycle progresses through initial reversible attachment, irreversible attachment, maturation, and dispersion phases [23]. This structured environment creates chemical and physical gradients that generate heterogeneous microbial subpopulations with varying metabolic states and antibiotic susceptibility profiles [23]. The EPS matrix itself acts as a diffusion barrier, impeding antibiotic penetration while facilitating horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants [23].

Diagram 1: Biofilm Development and Resistance Mechanisms

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

Antimicrobial Polymers

Synthetic nanoengineered antimicrobial polymers (SNAPs) represent a promising approach to combat MDR ESKAPE pathogens [22]. These polymers mimic the physicochemical properties of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) but offer advantages in manufacturing cost, stability, and tunability [22]. SNAPs containing N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) as hydrophobic constituents and N-(2-aminoethyl) acrylamide (AEAM) as cationic constituents demonstrate potent activity against Gram-negative pathogens like P. aeruginosa by targeting LPS and disrupting membrane integrity [22].

A particularly innovative approach involves oligoamidine (OA1) integrated into a thermoresponsive hydrogel (OA1-PF127), which exerts a triple antibacterial mechanism involving membrane disruption, DNA binding, and ROS generation [24]. This system offers convenient application to infected skin wounds and maintains full antimicrobial efficacy against MDR pathogens [24].

Phage Therapy

Bacteriophage therapy has re-emerged as a promising alternative to antibiotics, utilizing viruses that specifically infect and lyse bacterial cells [19] [25]. Phages offer strain-specific targeting, preserve the microbiome, and can co-evolve with bacteria, making them a flexible tool against resistance [19]. Recent advances include engineered phage cocktails and combination therapies with antibiotics, such as phage OMKO1 which targets bacterial efflux pumps in P. aeruginosa and increases antibiotic sensitivity when combined with ceftazidime [19].

Table 3: Emerging Therapeutic Approaches Against ESKAPE Pathogens

| Therapeutic Approach | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Nanoengineered Antimicrobial Polymers (SNAPs) | Membrane disruption via LPS targeting, pore formation [22] | Low toxicity, cost-effective production, multiple targets [22] | Preclinical research |

| Oligoamidine (OA1) Hydrogel | Triple mechanism: membrane disruption, DNA binding, ROS generation [24] | Biocompatible, wound-conforming, effective against MDR pathogens [24] | Ex vivo testing (pig skin model) |

| Bacteriophage Therapy | Bacterial cell lysis, biofilm disruption, enzymatic degradation [19] [25] | High specificity, co-evolution with bacteria, immune modulation [25] | Clinical trials and compassionate use |

| Phage-Antibiotic Synergy | Combined attack on bacterial structures and functions [19] | Enhanced efficacy, reduced resistance development [19] | Early clinical reports |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Laboratory Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance

Purpose: To characterize the potential for resistance development in ESKAPE pathogens against novel antimicrobial compounds [20].

Materials:

- Bacterial strains: ESKAPE pathogens (e.g., E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa)

- Antimicrobial compounds: Test and control antibiotics

- Culture media: Mueller-Hinton broth/agar

- Equipment: Microplate readers, automated systems (VITEK 2), incubators

Procedure:

- Strain Selection and Initial MIC Determination: Select MDR and drug-sensitive strains. Determine initial MICs for all antibiotics using broth microdilution following EUCAST/CLSI guidelines [20] [18].

- Spontaneous Frequency-of-Resistance (FoR) Analysis:

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE):

- Resistance Mechanism Characterization:

Diagram 2: Antibiotic Resistance Evolution Study Workflow

Protocol: Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for Surveillance Studies

Purpose: To monitor resistance patterns of ESKAPE pathogens in clinical settings [18].

Materials:

- Clinical isolates from blood cultures

- Blood culture bottles (aerobic and anaerobic)

- Identification systems: MALDI-TOF MS, VITEK 2

- Antimicrobial panels: AST cards for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria

- Quality control strains: P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing:

- Pathogen Identification:

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing:

- Resistance Mechanism Detection:

- Perform phenotypic ESBL detection with double-disk synergy tests [18].

- Detect carbapenemase production using PCR-based methods or immunochromatographic assays [18].

- Identify methicillin resistance in S. aureus using cefoxitin disk diffusion [18].

- Confirm vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus with E-test (MIC ≥32 μg/mL) [18].

Protocol: Evaluation of Antimicrobial Polymer Efficacy

Purpose: To assess the antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of synthetic antimicrobial polymers against ESKAPE pathogens [22].

Materials:

- Bacterial strains: P. aeruginosa LESB58 (clinical cystic fibrosis isolate)

- Antimicrobial polymers: SNAPs (e.g., a-D50 and a-T100 copolymers)

- Culture media: cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (caMHB)

- Analytical techniques: Scanning electron microscopy, atomic force microscopy, neutron reflectometry

Procedure:

- Bacterial Culture Preparation:

- MIC Determination:

- Morphological Analysis:

- Membrane Interaction Studies:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ESKAPE Pathogen Studies

| Reagent/System | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| VITEK 2 System (bioMérieux) | Automated identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing | AST-N334 cards for Gram-negative bacteria in surveillance studies [18] |

| BacT/ALERT Virtuo (bioMérieux) | Automated blood culture system | Detection of bloodstream infections from clinical samples [18] |

| MALDI-TOF MS (VITEK MS) | Rapid microbial identification | Species identification of ESKAPE pathogens from positive cultures [18] |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (caMHB) | Standardized susceptibility testing medium | MIC determination for antimicrobial polymers [22] |

| Synthetic Nanoengineered Antimicrobial Polymers (SNAPs) | Novel antimicrobial agents targeting bacterial membranes | Mechanism of action studies against P. aeruginosa [22] |

| Oligoamidine (OA1) | Cationic antimicrobial oligomer | Incorporation into hydrogels for wound infection treatment [24] |

| Biomimetic Asymmetric Membranes | Model bacterial outer membranes | Neutron reflectometry studies of polymer-membrane interactions [22] |

| RESIST-5 OOKNV Immunochromatographic Assay | Rapid carbapenemase detection | Identification of resistance mechanisms in K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii [18] |

| Stf-31 | Stf-31, CAS:724741-75-7, MF:C23H25N3O3S, MW:423.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Suksdorfin | Suksdorfin, CAS:53023-17-9, MF:C21H24O7, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The continuous evolution of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens necessitates innovative approaches that can overcome conventional resistance mechanisms. The integration of advanced antimicrobial polymers with traditional and emerging therapeutic strategies offers promising avenues for addressing this critical healthcare challenge. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide researchers with standardized methods for evaluating resistance development, monitoring epidemiological trends, and assessing novel interventions. As the field progresses, combination approaches leveraging multiple mechanisms of action—such as membrane disruption, nucleic acid binding, and immune modulation—will be essential for developing effective countermeasures against these formidable bacterial threats.

The Urgency of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and the Role of Polymeric Solutions

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a critical and escalating global health crisis, directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to nearly five million more [26]. Surveillance data from the World Health Organization (WHO) reveals that one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections globally are resistant to antibiotic treatments, with resistance rates increasing at an alarming 5-15% per year for over 40% of monitored antibiotic-bacteria combinations [27] [26]. This "silent pandemic" disproportionately affects regions with developing health systems and is particularly driven by the rise of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria [27] [28]. In this context, antimicrobial polymers emerge as a promising frontier in biomedical research, offering unique mechanisms of action that can circumvent traditional resistance pathways and provide new solutions for preventing and treating infections.

Global AMR Surveillance: Quantifying the Crisis

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the latest WHO Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report (2025) and supporting data, providing a snapshot of the current AMR landscape.

Table 1: Global Regional Resistance Prevalence (2023)

| WHO Region | Prevalence of Resistant Infections | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Global Average | 1 in 6 infections [27] | Baseline for global comparison |

| South-East Asia & Eastern Mediterranean | 1 in 3 infections [27] [26] | Highest regional prevalence |

| African Region | 1 in 5 infections [27] | Resistance exceeds 70% for some pathogens |

| Region of the Americas | 1 in 7 infections [27] | Slightly better than global average |

Table 2: Resistance in Key Gram-negative Pathogens

| Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Global Resistance Rate | Regional Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% [27] [26] | >70% in African Region [27] |

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% [27] [26] | Leading drug-resistant pathogen in bloodstream infections [27] |

| E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella, Acinetobacter | Carbapenems and Fluoroquinolones | Increasing, narrowing treatment options [27] [26] | Carbapenem resistance, once rare, is becoming more frequent [27] |

Antimicrobial polymers are designed to mimic host defense peptides and can be categorized based on their structure and mode of action. Their primary advantage lies in mechanisms that make it difficult for microbes to develop resistance, primarily through non-specific membrane disruption.

Classification and Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the logical classification of antimicrobial polymers and their primary mechanisms of action, which form the foundation for their application in biomedical research.

Membrane Lysis Mechanisms

Cationic polymers, rich in groups like quaternary ammonium or guanidinium, target the negatively charged bacterial membranes. The following workflow details the experimental process for synthesizing and evaluating the efficacy of such cationic antimicrobial polymers.

Experimental Protocols for Antimicrobial Polymer Evaluation

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in developing and characterizing antimicrobial polymers, designed for reproducibility in a research setting.

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Cationic Amphiphilic Polymers

Objective: To synthesize a cationic amphiphilic polymer with membrane-lysing properties [8]. Materials:

- Cationic Monomer: e.g., (3-Acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride (ATMAC)

- Hydrophobic Monomer: e.g., Butyl methacrylate (BMA)

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN)

- Solvent: Anhydrous methanol or ethanol

- Dialysis Tubing: Molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) appropriate for target polymer size

Procedure:

- Monomer Mixture Preparation: In a round-bottom flask, dissolve the cationic and hydrophobic monomers in a molar ratio of 70:30 (cationic:hydrophobic) in 50 mL of anhydrous solvent to achieve a total monomer concentration of 1.0 M.

- Initiator Addition: Add AIBN initiator at 1 mol% relative to total monomers. Purge the reaction mixture with nitrogen or argon for 20 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Polymerization: Heat the reaction mixture to 70°C with continuous stirring under an inert atmosphere for 18-24 hours.

- Purification: Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature. Precipitate the polymer by slowly dripping the solution into a large excess of cold diethyl ether or acetone. Re-dissolve the precipitate in deionized water and dialyze (using tubing with an appropriate MWCO, e.g., 3.5-7 kDa) against deionized water for 48 hours, changing the water every 12 hours.

- Characterization: Lyophilize the purified polymer. Characterize using ( ^1H )-NMR for composition and Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight and dispersity (Ã).

Protocol 2: Determining Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Objective: To determine the minimum concentration of the synthesized polymer that inhibits visible bacterial growth, based on standard broth microdilution methods [29] [13]. Materials:

- Test Organisms: Standard strains from the ESKAPE panel (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853).

- Growth Medium: Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CA-MHB).

- Sterile 96-well Polystyrene Microtiter Plate

- Positive Control: Broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin).

- Negative Control: CA-MHB only.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Adjust the turbidity of mid-logarithmic phase bacterial cultures in CA-MHB to 0.5 McFarland standard, then further dilute in CA-MHB to achieve a final concentration of approximately ( 5 \times 10^5 ) CFU/mL in the assay.

- Polymer Dilution: Prepare a stock solution of the test polymer in sterile water or DMSO (if poorly water-soluble). Create a two-fold serial dilution of the polymer directly in the microtiter plate using CA-MHB, typically covering a range from 1-512 µg/mL.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Add 100 µL of the prepared bacterial inoculum to each well containing 100 µL of the polymer dilution, mixing gently. Include growth control (bacteria + CA-MHB), sterility control (CA-MHB only), and a positive control well.

- Incubation: Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 18-24 hours without shaking.

- Result Interpretation: The MIC is the lowest concentration of the polymer that completely inhibits visible turbidity. Confirm the results by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) using a microplate reader.

Protocol 3: Membrane Integrity Assay via Cytoplasmic β-Galactosidase Activity

Objective: To confirm membrane-lysing activity by detecting the release of the cytoplasmic enzyme β-galactosidase from E. coli [8]. Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli ML-35 (constitutive for β-galactosidase).

- Assay Buffer: 0.1 M Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.0.

- Enzyme Substrate: Ortho-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG), prepared as a 10 mM solution in PBS.

- Stop Solution: 1 M Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Grow E. coli ML-35 to mid-log phase. Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash twice, and resuspend in PBS to an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.5.

- Polymer Exposure: Mix 450 µL of cell suspension with 50 µL of the test polymer solution at 1x and 2x the predetermined MIC. Include a negative control (cells + PBS) and a positive control (cells lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Reaction Initiation: Incubate the mixtures at 37°C for 60 minutes. Add 100 µL of 10 mM ONPG solution to each tube to start the reaction.

- Reaction Termination and Measurement: Incubate until a yellow color develops in the positive control (typically 10-30 minutes). Stop the reaction by adding 500 µL of 1 M Na₂CO₃. Remove cell debris by centrifugation and measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 420 nm.

- Analysis: Compare the absorbance of test samples to controls. A significant increase in absorbance compared to the negative control indicates membrane damage and the release of β-galactosidase.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential materials and reagents for research in antimicrobial polymers, as derived from the experimental protocols and literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Antimicrobial Polymer Development

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Monomers | Imparts positive charge for electrostatic binding to bacterial membranes [8] | (3-Acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride (ATMAC); Quaternized ammonium compounds. |

| Hydrophobic Monomers | Enables insertion and disruption of the lipid bilayer [8] | Butyl methacrylate (BMA); Modifies Hydrophobic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB). |

| Initiators | Starts polymerization reaction. | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN); For free-radical polymerization. |

| Standard Bacterial Strains | For in vitro efficacy and mechanism testing [29]. | ESKAPE panel strains: e.g., S. aureus (ATCC 29213), P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853). |

| Cell Culture Lines | For assessing cytotoxicity and selectivity [8]. | Mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HaCaT); Used in hemolysis and MTT assays. |

| Spectrophotometric Substrates | Detecting enzyme release from cytosol upon membrane damage. | Ortho-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG); Yields yellow product (o-nitrophenol) upon cleavage. |

| Sulfasymazine | Sulfasymazine, CAS:1984-94-7, MF:C13H17N5O2S, MW:307.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| T56-LIMKi | T56-LIMKi, MF:C19H14F3N3O3, MW:389.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Design and Deployment: Synthetic Strategies and Biomedical Applications of Antimicrobial Polymers

The escalating challenge of antibiotic resistance has catalyzed the exploration of advanced materials for antimicrobial applications. Within this landscape, polymers—both bio-based and synthetic—have emerged as pivotal tools. Bio-based polymers, such as chitosan (derived from chitin) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), offer exceptional biocompatibility and innate biological activity [30] [31]. Conversely, synthetic polymers like polyurethanes and polyesters provide unparalleled versatility, tunable mechanical properties, and widespread industrial utility [32] [33] [34]. This document frames these material classes within the context of antimicrobial biomedical research, providing application notes and detailed experimental protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The focus is on leveraging the intrinsic properties of these polymers and their hybrid systems to develop next-generation antimicrobial strategies.

Bio-Based Polymers

Chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide derived from the deacetylation of chitin, a primary component of crustacean shells and fungal cell walls. Its structure comprises β-(1→4)-linked N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine units [30]. The material is celebrated for its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low toxicity [30] [31].

Antimicrobial Mechanism: The primary mechanism of action is electrostatic. The protonated amino groups (NH₃âº) on the glucosamine units of chitosan interact with the negatively charged components of microbial cell membranes (e.g., lipopolysaccharides in gram-negative bacteria, teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria) [30]. This interaction increases membrane permeability, leading to cell leakage and death [30]. Additional mechanisms include the chelation of essential metals and the penetration into the cell to bind DNA, inhibiting RNA and protein synthesis [30].

Key Properties for Biomedical Use: The antimicrobial efficacy and overall performance of chitosan are governed by several factors, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Properties of Chitosan and Their Impact on Biomedical Applications

| Property | Description | Impact on Antimicrobial Activity & Biomedical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Degree of Deacetylation (DDA) | The proportion of D-glucosamine units in the polymer chain. | A higher DDA increases the density of cationic amine groups, enhancing antimicrobial efficacy, particularly at low pH [30]. |

| Molecular Weight | The size of the polymer chain. | Low molecular weight (LMW) chitosan can penetrate cell walls more effectively, while high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan may form a more extensive polymer film on cell surfaces [30]. LMW chitosan also demonstrates superior antioxidant activity [30]. |

| Solubility | Soluble in dilute acidic solutions (pH < 6.3) [30]. | Poor water solubility at neutral and basic pH is a major limitation for its application in physiological environments [30] [31]. |

| Mucoadhesivity | Ability to adhere to mucosal surfaces. | Enhances residence time at infection sites, promoting sustained antimicrobial action and improved drug delivery [30]. |

PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid))

PLGA is a synthetic, biodegradable copolymer that is FDA-approved for therapeutic use in humans. It hydrolyzes into its monomeric acids, lactic acid and glycolic acid, which are metabolized via the Krebs cycle [35]. While not intrinsically antimicrobial, its role as a controlled-release carrier for antimicrobial agents is indispensable.

Role in Antimicrobial Applications: PLGA serves as a protective reservoir for encapsulated drugs, shielding them from degradation and enabling controlled release kinetics. This prolongs the therapeutic presence of antimicrobials at the infection site, potentially reducing dosing frequency and improving efficacy against biofilms [35].

Key Formulation Considerations: The properties of PLGA can be tuned for specific drug delivery needs.

Table 2: Key Tunable Parameters of PLGA for Drug Delivery

| Parameter | Options | Impact on Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Lactide:Glycolide (L:G) Ratio | 50:50, 65:35, 75:25, 85:15 | A higher glycolide content generally leads to faster degradation and drug release rates due to increased hydrophilicity [36]. |

| Molecular Weight | Varies (e.g., 7,000-20,000 Da) | Higher molecular weight polymers degrade more slowly, leading to sustained drug release over a longer period. |

| End Group | Carboxylate (acid-capped) or Ester (ester-capped) | Acid-capped PLGA degrades faster than ester-capped due to autocatalysis by the terminal carboxylic acid groups. |

Chitosan-PLGA Hybrid Systems

The combination of chitosan and PLGA creates a synergistic system that merges the favorable properties of both polymers. The cationic surface of chitosan enhances mucoadhesion and interaction with bacterial membranes, while the PLGA core provides robust, controllable drug encapsulation [36] [35]. Furthermore, coating PLGA with chitosan can improve the stability of colloidal systems and enhance cellular uptake [35].

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Chitosan-Coated PLGA Nanoparticles via Double Emulsion (W/O/W) Method

This protocol is adapted from methods used to encapsulate cepharanthine and other hydrophilic drugs [35].

- 1. Aim: To fabricate and characterize antibiotic-loaded PLGA nanoparticles with a chitosan coat to enhance antimicrobial activity and stability.

- 2. Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated, Mw ~11,000 Da)

- Coating Polymer: Chitosan (Low Molecular Weight, ~14,000 Da, viscosity 20-100 mPa·s)

- Drug: Water-soluble antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin)

- Solvents: Dichloromethane (DCM), Acetone

- Aqueous Phases: Deionized Water, 1-5% (v/v) Acetic Acid solution

- Surfactants: Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), Poloxamer 188 (F68)

- Equipment: Probe sonicator, Magnetic stirrer/hot plate, Centrifuge, Lyophilizer, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) system for size and zeta potential measurement, HPLC system for encapsulation efficiency.

- 3. Workflow Diagram:

- 4. Experimental Procedure:

- Inner Aqueous Phase (W1): Dissolve the hydrophilic antibiotic (e.g., 10 mg) in 1 mL of deionized water.

- Organic Phase (O): Dissolve 100 mg of PLGA in 3 mL of DCM.

- Primary Emulsion (W1/O): Add the W1 phase to the O phase. Emulsify using a probe sonicator (e.g., 50-70 W power) on ice for 60-90 seconds to form a stable water-in-oil (W1/O) emulsion.

- Outer Aqueous Phase (W2): Dissolve 100 mg of PVA and 20-50 mg of chitosan in 100 mL of a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution. Adjust the pH to ~4.5-5.0 if necessary.

- Secondary Emulsion (W1/O/W2): Pour the primary W1/O emulsion into the W2 phase under constant stirring (500-700 rpm). Subsequently, sonicate the mixture on ice for 2-3 minutes to form the double (W1/O/W2) emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Stir the double emulsion continuously at room temperature for 4-6 hours or overnight to allow for complete evaporation of DCM and nanoparticle hardening.

- Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle suspension at high speed (e.g., 20,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C). Wash the pellet with deionized water to remove free surfactants and unencapsulated drug. Repeat centrifugation.

- Lyophilization: Re-suspend the final nanoparticle pellet in a minimal volume of water and lyophilize for 48 hours to obtain a dry powder for storage and further use.

- 5. Characterization:

- Size and Zeta Potential: Hydration particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential are measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). A successful chitosan coating is indicated by a positive zeta potential shift (e.g., from negative for plain PLGA to +20 to +40 mV) [35].

- Encapsulation Efficiency (EE): Determine by HPLC. Briefly, dissolve a known amount of nanoparticles in acetonitrile to break the matrix and release the drug. Filter and analyze the drug content via HPLC. Calculate EE% = (Amount of drug in nanoparticles / Total amount of drug used) × 100. Values above 80% are achievable [35].

- Morphology: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) or Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to confirm spherical morphology and monodisperse size distribution.

Synthetic Polymers

Polyurethanes

Polyurethanes (PUs) are a class of polymers characterized by carbamate (urethane) linkages in their backbone, formed by the reaction between a diisocyanate and a polyol [33]. Their properties can be finely tuned from soft elastomers to rigid foams by selecting appropriate starting materials.

Antimicrobial Mechanism (Cationic Poly(ester urethane)s): A significant advancement in antimicrobial PUs is the design of facially amphiphilic poly(ester urethane)s [32]. These polymers mimic antimicrobial peptides by incorporating cationic groups (e.g., quaternary ammonium) and hydrophobic segments uniformly along the polymer chain. The cationic groups electrostatically target negatively charged bacterial membranes, while the hydrophobic moieties integrate into and disrupt the lipid bilayer, causing leakage of cellular contents and cell death [32].

Structure-Activity Relationship: The balance between cationic charge density and hydrophobic character is critical for maximizing antimicrobial activity while minimizing toxicity to human cells (hemolysis) [32].

Table 3: Key Features and Applications of Synthetic Polymers

| Polymer | Key Monomers / Features | Primary Antimicrobial Mechanism | Example Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethanes | Diisocyanate (e.g., TDI, MDI, Hâ‚â‚‚MDI) + Polyol (e.g., polyether, polyester) [33]. | Membrane disruption via cationic-hydrophobic balance in designed polymers [32]. | Antimicrobial coatings on medical devices (catheters, endotracheal tubes), wound dressings [32] [33]. |

| Polyesters | Diacid (e.g., Terephthalic Acid) + Diol (e.g., Ethylene Glycol) [34]. | Primarily as a drug delivery vehicle (e.g., PLGA). Some inherent activity in natural polyesters. | Sutures, drug delivery systems (nanoparticles, microparticles), tissue engineering scaffolds [37] [34]. |

Polyesters

Polyesters contain ester functional groups in their main chain. While PLGA is a prominent biodegradable polyester in biomedicine, the broader class includes commodity plastics like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [37] [34]. In antimicrobial applications, they primarily function as carriers for active compounds, though some aliphatic polyesters like polylactic acid (PLA) exhibit mild acidic antimicrobial effects upon degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Antimicrobial Polymer Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Low Molecular Weight Chitosan | Provides a higher solubility and potentially better penetration. Defined by viscosity and degree of deacetylation. | Coating nanoparticles for enhanced mucoadhesion and antimicrobial effect [30] [35]. |

| PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated) | A standard, rapidly degrading copolymer for controlled drug release. | Forming the core matrix of drug-loaded nanoparticles [36] [35]. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) / EDC | Carbodiimide crosslinker system for activating carboxylic acids for amide bond formation. | Conjugating polymers (e.g., PLGA to chitosan) or attaching targeting ligands [36]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A common surfactant and stabilizer in emulsion-based nanoparticle synthesis. | Preventing aggregation of nanoparticles during formulation [35]. |

| Cationic Diisocyanate Monomer | A diisocyanate functionalized with a pending or inherent cationic group (e.g., quaternary ammonium). | Synthesizing intrinsically antimicrobial polyurethanes [32]. |

| Methylene Diphenyl Diisocyanate (MDI) | An aromatic diisocyanate monomer. | Forming the urethane linkages in polyurethane synthesis; provides mechanical strength [33]. |

| Polyether Polyol | A polyol with ether linkages, providing hydrolytic stability and flexibility. | Creating the soft segment in polyurethanes for flexible applications like wound dressings [33]. |

| Tacedinaline | Tacedinaline, CAS:112522-64-2, MF:C15H15N3O2, MW:269.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TAK-070 free base | TAK-070 free base, CAS:212571-56-7, MF:C27H31NO, MW:385.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Application Notes & Testing Protocols

Application Note: Combating Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia with a Chitosan-PLGA Nanoemulsion

Background: Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia (SAP), particularly methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains, poses a significant therapeutic challenge due to antibiotic resistance and the need for drugs to penetrate the lung epithelium [35].

Solution: A cepharanthine-loaded, chitosan-coated PLGA nanoemulsion (CCPN) was developed [35]. The PLGA core provides sustained release of the anti-inflammatory and antibacterial drug cepharanthine, while the chitosan coating enhances stability, mucoadhesion in the lung, and intrinsic antibacterial activity.

Outcome: In a murine model of SAP, the CCPN system demonstrated:

- Significant reduction in bacterial load in lung tissue.

- Down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6).

- Inhibition of bacterial biofilm formation in vitro.

- Improved pathological scores of lung tissue compared to free drug [35].

This application highlights the synergy of a bio-based polymer (chitosan) and a synthetic polyester (PLGA) in creating an effective antimicrobial therapeutic system.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Assessment of Antimicrobial Polymer Activity

- 1. Aim: To evaluate the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and bactericidal kinetics of an antimicrobial polymer (e.g., a cationic poly(ester urethane) or chitosan derivatives).

- 2. Materials:

- Test polymer solution

- Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB)

- Sterile 96-well microtiter plates

- Overnight culture of test organisms (e.g., S. aureus, E. coli)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Multi-channel pipette

- Microplate reader

- 3. Workflow Diagram:

- 4. Experimental Procedure (MIC/MBC):

- Broth Dilution: Perform two-fold serial dilutions of the test polymer in MHB across a 96-well plate.

- Inoculation: Dilute a fresh overnight bacterial culture in MHB to achieve a concentration of approximately 5 x 10âµ CFU/mL. Add an equal volume of this bacterial suspension to each well containing the polymer dilutions. Include growth control (bacteria only) and sterility control (media only) wells.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 16-20 hours.

- MIC Determination: The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of polymer that completely inhibits visible growth, as observed visually or by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

- MBC Determination: From the wells showing no visible growth, subculture a sample (e.g., 10 µL) onto fresh agar plates. Incubate these plates for 24 hours. The Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) is the lowest polymer concentration that results in ≥99.9% killing of the initial inoculum (i.e., no growth on the subculture plate).

Protocol 3: Synthesis of Cationic Amphiphilic Poly(ester urethane)s

- 1. Aim: To synthesize a poly(ester urethane) with uniform distribution of cationic and hydrophobic groups for membrane-disrupting antimicrobial activity [32].

- 2. Materials:

- Cationic diol monomer (containing e.g., quaternary ammonium group)

- Hydrophobic diol monomer (e.g., polycaprolactone diol)

- Diisocyanate (e.g., HDI or MDI)

- Catalyst (e.g., Dibutyltin dilaurate, DBTDL)

- Anhydrous solvent (e.g., DMF or DMSO)

- Schlenk line or round-bottom flask with nitrogen inlet

- 3. Experimental Procedure:

- Monomer Preparation: Dry all monomers and solvents thoroughly before use.

- Reaction: In a flame-dried flask under an inert nitrogen atmosphere, dissolve the cationic diol and hydrophobic diol in anhydrous solvent. Add the diisocyanate monomer in a slight stoichiometric excess relative to the total OH groups.

- Catalysis: Add a few drops of the catalyst (e.g., DBTDL).

- Polymerization: Heat the reaction mixture to 70-85°C with stirring for 6-24 hours. The reaction progress can be monitored by FT-IR, observing the disappearance of the isocyanate peak (~2270 cmâ»Â¹).

- Purification: Precipitate the resulting polymer into a large excess of a non-solvent (e.g., diethyl ether or cold methanol). Filter and dry the purified polymer under vacuum.

The strategic use of bio-based and synthetic polymers offers a powerful arsenal for developing advanced antimicrobial solutions. Chitosan provides a naturally derived, active platform, while PLGA offers a proven, controllable delivery vehicle. Synthetic polymers like polyurethanes and polyesters contribute tunable mechanical and chemical properties, with the capacity for sophisticated molecular design to impart intrinsic antimicrobial activity. The future of this field lies in the intelligent design of hybrid materials and copolymers that maximize synergy between components, ultimately leading to more effective therapies against drug-resistant infections.

The escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates the development of novel materials that can effectively combat pathogenic microbes without inducing resistance. Polymeric materials, particularly those with inherent antimicrobial activity, have emerged as a cornerstone of this effort, offering versatile platforms for biomedical applications such as medical devices, wound dressings, and drug delivery systems [38] [6]. The global market for polymeric biomaterials is projected to reach 169.88 billion USD by 2029, reflecting the intense research and commercial interest in this field [6]. The efficacy of these materials is intrinsically linked to sophisticated synthesis and functionalization strategies, including quaternization, grafting, and nanostructure fabrication, which allow for precise control over their biological interactions. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for key methodologies employed in the development of advanced antimicrobial polymers, framed within a thesis on biomedical applications.

Application Notes & Quantitative Data

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs) as Antimicrobial Agents

The incorporation of quaternary ammonium centers (QACs) into polymers is a primary strategy for creating contact-killing, non-releasing antimicrobial surfaces. These cationic groups interact electrostatically with negatively charged bacterial cell envelopes, disrupting membranes and causing cell death [38]. A critical factor influencing biocidal activity is the structure of the QAC, particularly the length of the alkyl chain.

Table 1: Antibacterial Efficacy of Quaternary Ammonium Surfmeters with Different Alkyl Chain Lengths

| Surfrmer / Compound | Alkyl Chain Length | Test Organism | Minimal Inhibition Concentration (MIC, μmol Lâ»Â¹) | Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC, μmol Lâ»Â¹) | Killing Efficiency (log CFU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12QAS [39] | C12 | S. aureus | 15.00 | 60.00 | > 1.69 |

| 14QAS [39] | C14 | S. aureus | 3.75 | 15.00 | 2.86 |

| 16QAS [39] | C16 | S. aureus | 1.875 | 7.50 | 3.59 |

| 18QAS [39] | C18 | S. aureus | 0.937 | 3.75 | 4.23 |

| 16QAS [39] | C16 | E. coli | 16.13 | 32.25 | 2.61 |

| CTAB (Control) [39] | C16 | S. aureus | 1.875 | 7.50 | 3.59 |

Data from [39] demonstrate a clear structure-activity relationship. Against S. aureus, antibacterial potency increases with alkyl chain length, with 18QAS showing the lowest MIC and highest killing efficiency. Furthermore, the study highlights that QACs are generally more effective against Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus) than Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) due to differences in their cell wall structures [39].

Beyond small molecules, QACs can be integrated into polymer resins for water treatment. Research on quaternary ammonium pyridine resins (QAPRs) identified hexyl (C6) chains as the optimal alkyl group for antibacterial performance. A novel resin, Py-61, was synthesized by grafting a hexyl-bearing QAC onto a poly(4-vinylpyridine) backbone, achieving an exceptional antibacterial efficiency of 99.995% in water disinfection, successfully reducing viable bacteria from 3600 CFU/mL to 17 CFU/mL to meet drinking water standards [40].

Grafting Techniques for Antimicrobial Surfaces

Creating non-releasing, antimicrobial surfaces often requires covalently attaching polymer chains to a substrate. The choice of grafting methodology significantly impacts the density and efficacy of the resulting coating.

Table 2: Comparison of Grafting Methodologies for Antimicrobial Polymer Surfaces

| Grafting Method | Mechanism | Key Features | Antimicrobial Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Grafting From" (e.g., SI-ATRP, SI-RAFT) [38] [41] | Polymerization initiator is immobilized on the surface, and polymer chains grow directly from the substrate. | Achieves high grafting density and uniform coating. Requires surface pre-functionalization with an initiator. | Produces surfaces with high charge density (up to 10¹ⶠcharges/cm²), leading to quick bacterial cell death upon contact [38]. |

| "Grafting To" [38] [41] | Pre-synthesized polymer chains are attached to the surface via a coupling reaction. | Simpler but suffers from low grafting density due to steric hindrance from already-attached chains. | Lower charge density (∼10¹ⴠcharges/cm²) and consequently lower biocidal efficacy compared to "grafting from" [38]. |

| Radiation-Induced Grafting [42] | Gamma radiation generates active sites on a polymer substrate (e.g., silicone), initiating monomer polymerization. | No initiators or catalysts needed; a pure and versatile method. Can be performed at room temperature. | Used to graft poly(N-vinylimidazole) onto silicone catheters, which were subsequently quaternized or loaded with antibiotics to impart antimicrobial functionality [42]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Synthesis of an Antimicrobial Quaternary Ammonium Pyridine Resin (Py-61)

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a highly efficient antibacterial resin for water disinfection, based on the procedure described in [40].

Principle: A two-stage quaternization process is used to first functionalize the surface of a poly(4-vinylpyridine) resin with a highly efficient antibacterial alkyl group (hexyl), followed by comprehensive bulk modification to maximize cationic charge density.

Materials:

- Poly(4-vinylpyridine) resin (Py-0, 25% cross-linkage)

- N, N-dimethylhexylamine

- 1,3-dibromopropane

- Iodomethane

- Absolute ethanol, acetone, methanol

- 15% (wt./wt.) Sodium chloride (NaCl) solution

- Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) gas

Procedure:

- Synthesis of Brominated QAC (Br-QAC-C6):

- In a round-bottom flask under N₂ atmosphere, react N, N-dimethylhexylamine (0.15 mol) with 1,3-dibromopropane (0.15 mol) at 76°C for 6 hours.

- Cool to room temperature and purify the product to obtain Br-QAC-C6.

Surface-Selective Functionalization:

- Charge a 500 mL three-necked flask with poly(4-vinylpyridine) resin (Py-0, 20 g) and 60 mL absolute ethanol.

- Add the synthesized Br-QAC-C6 (0.009 mol) dropwise to the stirring suspension.

- Continuously stir the system at 200 rpm at 38°C under reflux for 24 hours.

- Filter the resin and wash thoroughly with acetone, methanol, and absolute ethanol. Label this product as Py-6N.

Bulk Quaternization:

- Transfer the Py-6N resin to a clean three-necked flask containing 60 mL absolute ethanol and 60 g of iodomethane.

- Stir continuously at 200 rpm at 38°C under reflux for 48 hours.

- Filter the obtained resin and extract sequentially with acetone, methanol, and absolute ethanol. Label this intermediate as Py-61-I.

Anion Exchange and Activation:

- Activate the Py-61-I resin by stirring it in a 15% (wt./wt.) NaCl solution for 4 hours to exchange counter anions (Brâ» and Iâ») for Clâ», reducing the potential for toxic disinfection byproducts.

- Wash the resin five times with ultrapure water. The final product is Py-61.

Quality Control: The surficial N⺠charge density can be determined using a dye-binding assay with sodium tetraphenylborate [40]. Antibacterial efficiency should be evaluated against model strains like E. coli and S. aureus.

Protocol 2: "Grafting From" Poly(DMAEMA) Brushes via Surface-Initiated ATRP

This protocol details the formation of a polymer brush coating with quaternizable amines on a glass surface, adapted from [38] [41].