Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Design: Accelerating Drug Delivery Material Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Bayesian Optimization (BO) for navigating the complex parameter space of polymer design in drug development.

Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Design: Accelerating Drug Delivery Material Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Bayesian Optimization (BO) for navigating the complex parameter space of polymer design in drug development. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it covers foundational concepts of BO and polymer properties, details practical methodologies for building surrogate models and acquisition functions, addresses common implementation challenges, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with traditional methods. The goal is to equip professionals with the knowledge to dramatically reduce experimental cycles and cost while optimizing polymers for specific biomedical applications like controlled drug release, targeting, and biocompatibility.

Navigating Complexity: Why Bayesian Optimization is the Key to Polymer Parameter Space

Technical Support Center: Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Research

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our Bayesian Optimization (BO) routine is not converging on an optimal polymer formulation. The acquisition function seems to be exploring randomly. What could be wrong? A: This is often due to poor hyperparameter tuning of the underlying Gaussian Process (GP) model or an incorrectly specified acquisition function.

- Check 1: Verify your kernel choice. For high-dimensional polymer spaces (e.g., >10 components), a Matérn kernel (

nu=2.5ornu=1.5) is typically more robust than a standard squared-exponential (RBF) kernel, which can misrepresent length scales. - Check 2: Re-examine your noise parameter (

alpha). Experimental noise in polymer synthesis (e.g., batch-to-batch variation) is often underestimated. Increasealphaif your objective function values are noisy. - Protocol: Perform a preliminary hyperparameter optimization of the GP model using a maximum marginal likelihood estimate (MLE) on your existing data before each BO iteration.

Q2: How do I effectively encode categorical parameters (e.g., solvent type, initiator class) alongside continuous parameters (e.g., concentration, temperature) in a BO loop? A: Use a mixed-variable kernel. Common approaches include:

- One-Hot Encoding with a Coregionalization Kernel: Treat each category as an extra dimension. Use a combination of a continuous kernel (e.g., Matérn) for numeric features and a coregionalization kernel to model interactions between categories.

- Separate Kernels: Use a product kernel:

K_total = K_continuous * K_categorical. For the categorical kernel, a Hamming distance-based kernel is appropriate. - Recommendation: Libraries like

BoTorchandDragonflyhave built-in support for mixed search spaces. Start with their default implementations.

Q3: Experimental evaluation is the bottleneck. How can I minimize the number of synthesis rounds needed? A: Implement a batch or asynchronous BO strategy.

- Methodology: Instead of suggesting one polymer to test per iteration, use a batch acquisition function like

q-EI(Expected Improvement) orq-UCB(Upper Confidence Bound) to propose 3-5 candidates per batch. This allows parallel synthesis and characterization. - Critical Consideration: Ensure your lab's high-throughput screening (HTS) protocol is robust enough that batch results are comparable. Include a control sample in every batch for normalization.

Q4: We have some prior knowledge from failed historical projects. How can we incorporate this "negative data" into the BO model? A: You can warm-start the BO process.

- Protocol: Aggregate all historical data, including formulations that did not meet target properties. Pre-process the data to ensure consistent objective metrics. Initialize your BO's GP model with this dataset. To prevent bias from overwhelmingly negative data, consider:

- Clustering the data and selecting diverse representatives.

- Applying a small weight to older data points.

- Model Adjustment: You may need to use a non-zero mean function for the GP to reflect prior trends.

Experimental Protocols for Cited Key Experiments

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Copolymer Ratios for Drug Encapsulation Efficiency

- Design: Using BO, generate a batch of 5 candidate copolymer compositions (e.g., PLGA-PEG ratios).

- Parallel Synthesis: Prepare each copolymer via ring-opening polymerization in a 96-well microreactor block.

- Nanoprecipitation: Form nanoparticles from each copolymer batch using a standardized solvent displacement method.

- Drug Loading: Incubate a fixed concentration of model drug (e.g., Doxorubicin) with each nanoparticle batch.

- Analysis: Centrifuge to separate free drug. Use HPLC to quantify unencapsulated drug in the supernatant. Calculate encapsulation efficiency (EE%) as the objective function for BO.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Cross-Linking Density in Hydrogels for Mechanical Strength

- Design: BO suggests parameters: cross-linker molar percentage, UV irradiation time, and polymer concentration.

- Synthesis: Formulate hydrogels in standardized cylindrical molds (n=3 per formulation).

- Curing: Expose to UV light at a fixed wavelength for the specified time.

- Equilibration: Swell gels in PBS for 24h at 37°C.

- Testing: Perform uniaxial compression testing on a texture analyzer. Record compressive modulus at 15% strain. Use the average modulus as the BO objective.

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Bayesian Optimization Frameworks for Polymer Research

| Framework/Library | Mixed Variable Support | Parallel/Batch Evaluation | Key Advantage for Polymer Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| BoTorch (PyTorch) | Excellent (via Ax) |

Native (q-acquisition functions) | Flexibility for custom models & high-dimensional spaces. |

| Scikit-Optimize | Basic (transformers) | Limited | Simplicity, integrates easily with Scikit-learn. |

| Dragonfly | Excellent | Good | Handles combinatorial conditional spaces well (e.g., if solvent=A, use parameter X). |

| GPyOpt | Limited | Limited | Good for rapid prototyping of simple spaces. |

Table 2: Example Polymer Formulation Search Space (Hydrogel Stiffness)

| Parameter | Type | Range/Options | BO Encoding Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Conc. | Continuous | 5-20% (w/v) | Normalized to [0, 1]. |

| Cross-linker Type | Categorical | EGDMA, MBA, PEGDA | One-Hot Encoding. |

| Cross-linker % | Continuous | 0.5-5.0 mol% | Normalized to [0, 1]. |

| Initiator Conc. | Continuous | 0.1-1.0 wt% | Log-scale normalization. |

| Temp. | Continuous | 25-70 °C | Normalized to [0, 1]. |

Visualizations

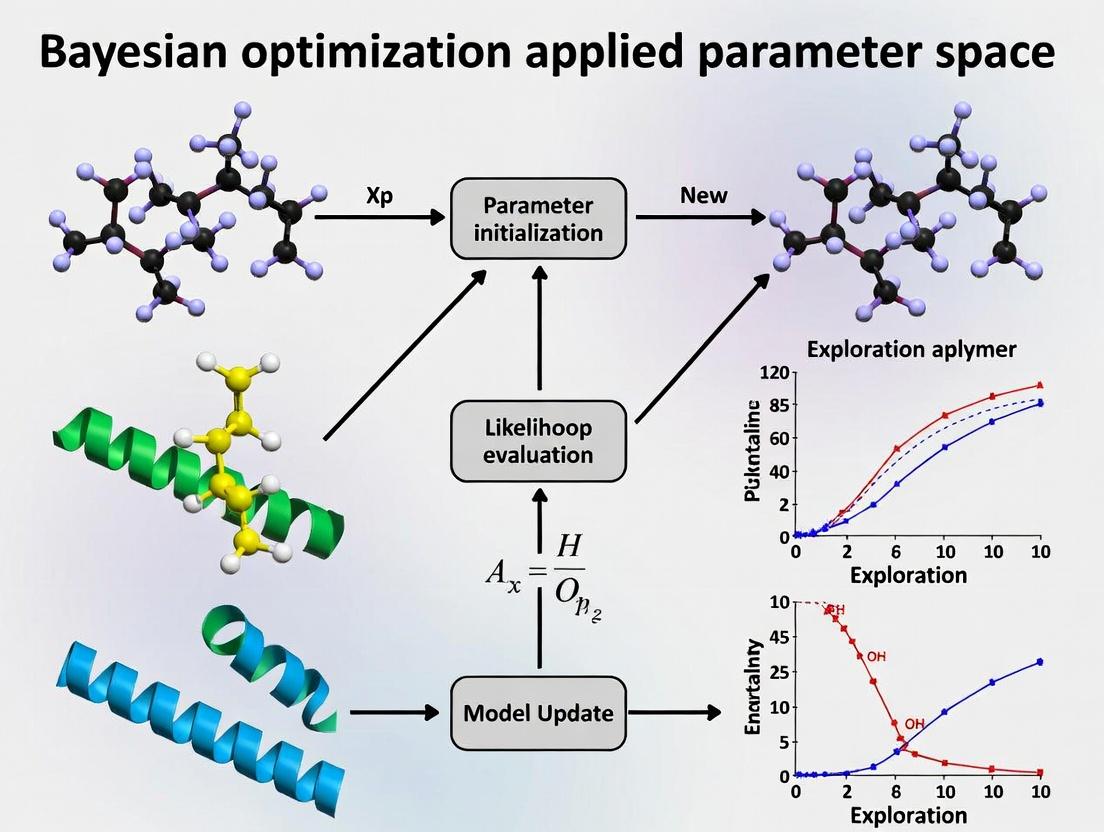

Title: Bayesian Optimization Loop for Polymer Design

Title: BO Reduces Haystack Searches for Optimal Polymer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Polymer/BO Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate Reactors | Enables parallel synthesis of BO-suggested polymer batches. | Must be chemically resistant to monomers/solvents. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses variable ratios of monomers/solvents for reproducibility. | Calibration is critical for high-dimensional formulation accuracy. |

| GPC/SEC System | Provides key objective function data: molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and dispersity (Đ). | Ensure compatible solvent columns for your polymer library. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures glass transition temperature (Tg), a critical polymer property for BO targets. | Use hermetically sealed pans to prevent solvent evaporation. |

| Plate Reader with DLS | High-throughput measurement of nanoparticle size (PDI) and zeta potential. | Well-plate material must minimize particle adhesion. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software (e.g., BoTorch) | Core algorithm for navigating the polymer parameter space and suggesting experiments. | Requires clean, structured data input from characterization tools. |

Troubleshooting & FAQs: Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Parameter Space Research

FAQ 1: My Gaussian Process (GP) model fails to converge or produces unrealistic predictions for my polymer viscosity data. What could be wrong?

- Answer: This is often due to an inappropriate kernel (covariance function) choice or poorly scaled input data. Polymer properties like viscosity can span several orders of magnitude.

- Action: Log-transform your target variable (e.g., viscosity). Standardize all input parameters (e.g., monomer ratio, temperature, catalyst concentration) to have zero mean and unit variance.

- Kernel Selection: For polymer parameter spaces, start with a Matérn 5/2 kernel, which is less smooth than the common RBF kernel and better handles abrupt changes in material properties. Combine it with a WhiteKernel to account for experimental noise.

FAQ 2: The acquisition function keeps suggesting experiments in a region of the parameter space I know from literature is unstable or hazardous. How do I incorporate this prior knowledge?

- Answer: You must constrain the optimization. Implement constrained Bayesian optimization.

- Methodology: Model the constraint (e.g., "reactor pressure < 100 bar") with a separate GP classifier or GP regressor. The acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) is then multiplied by the probability that the constraint is satisfied. This ensures the algorithm only suggests safe, feasible experiments.

FAQ 3: After several iterations, the optimization seems stuck, suggesting very similar polymer formulations. Is it exploiting too much?

- Answer: This is a classic exploitation vs. exploration trade-off issue. Your acquisition function's balance is off.

- Troubleshooting: Increase the exploration parameter. For the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function, increase the

kappaparameter (e.g., from 2.0 to 3.5). For Expected Improvement (EI) or Probability of Improvement (PI), use a larger xi parameter to encourage looking further from known good points.

- Troubleshooting: Increase the exploration parameter. For the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function, increase the

FAQ 4: How do I validate that my Bayesian Optimization routine is working correctly on my polymer project before committing expensive lab resources?

- Answer: Perform a synthetic benchmark.

- Protocol:

- Choose a known simulated function (e.g., Branin-Hoo) that roughly mimics the complexity of your polymer response surface.

- Run your full BO pipeline (GP modeling, acquisition, suggestion) on this synthetic function for 20-50 iterations.

- Track the cumulative best-observed value. A well-tuned BO should find the optimum significantly faster than random sampling or grid search.

- Compare different kernel/acquisition function pairs in this controlled environment.

- Protocol:

FAQ 5: My experimental measurements for polymer tensile strength have high noise, which confuses the GP model. How should I handle this?

- Answer: Explicitly model the noise.

- Guide: When initializing your GP model, do not assume

alpha(noise level) is a small constant. Instead, specify a WhiteKernel as part of your kernel combination (e.g.,Matérn() + WhiteKernel()). Allow the GP's hyperparameter optimization to learn the noise level from your data. Alternatively, if you have known experimental error bars, you can pass thealphaparameter as an array of measurement variances for each data point.

- Guide: When initializing your GP model, do not assume

Key Performance Metrics: Benchmarking BO Algorithms

The following table summarizes typical performance gains when applying BO to material science problems, based on recent literature.

Table 1: Benchmark Results for BO in Material Parameter Search

| Material System | Parameters Optimized | Benchmark vs. Random Search | Typical Iterations to Optimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block Copolymer Morphology | Chain length ratio, annealing temperature, solvent ratio | 3x - 5x faster | 15-25 |

| Hydrogel Drug Release Rate | Polymer concentration, cross-linker density, pH | 2x - 4x faster | 20-30 |

| Conductive Polymer Composite | Filler percentage, mixing time, doping agent concentration | 4x - 8x faster | 10-20 |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Bayesian Optimization Loop for Polymer Synthesis

Title: Iterative Bayesian Optimization for Polymer Design

Objective: To efficiently identify the polymer formulation parameters that maximize tensile strength.

Methodology:

- Initial Design: Perform 8-10 initial experiments using a Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) design across the parameter space (e.g., Monomer A%, Catalyst Level, Reaction Temp).

- Characterization: Measure the target property (Tensile Strength in MPa) for each initial sample.

- Modeling: Fit a Gaussian Process model with a Matérn 5/2 kernel to the (parameters, strength) data.

- Acquisition: Calculate the Expected Improvement (EI) across a dense grid of candidate parameters.

- Suggestion: Select the candidate with the maximum EI as the next experiment.

- Iteration: Run the new experiment, add the result to the dataset, and repeat steps 3-5 until the strength improvement falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., <2% improvement over 3 consecutive iterations) or the budget is exhausted.

Visualizing the Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Diagram Title: Bayesian Optimization Loop for Polymer Design

Visualizing the Gaussian Process Regression Process

Diagram Title: From Prior to Posterior in Gaussian Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer BO

Table 2: Essential Materials for Polymer Parameter Space Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Bayesian Optimization Context |

|---|---|

| Multi-Parameter Reactor Station | Enables automated, precise control of synthesis parameters (temp, stir rate, feed rate) as dictated by BO suggestions. |

| High-Throughput GPC/SEC System | Provides rapid molecular weight distribution data for each synthesis iteration, a common target property for optimization. |

| Automated Tensile Tester | Quickly measures mechanical properties (strength, elongation) of polymer films from multiple BO iterations. |

| Standardized Monomer Library | Well-characterized starting materials ensuring that changes in properties are due to optimized parameters, not batch variance. |

| In-line Spectrophotometer | Allows for real-time monitoring of reaction progress, providing dense temporal data to enrich the BO dataset. |

| Robotic Sample Handling System | Automates the preparation and quenching of reactions, increasing throughput and consistency between BO cycles. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During nanoparticle self-assembly, my polymer yields inconsistent particle sizes (PDI > 0.2) despite using the same nominal molecular weight. What could be the root cause and how can I fix it? A: High polydispersity (PDI) often stems from uncontrolled polymerization kinetics or inadequate purification. Nominal molecular weight from suppliers is an average; batch-to-batch variations in dispersity (Đ) are critical.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) to determine the true Đ of your polymer batch. Do not rely on nominal values.

- Purify: For amphiphilic block copolymers, use preparatory-scale SEC or iterative precipitation to isolate narrow fractions.

- Process Control: Ensure consistent solvent evaporation rates (e.g., use a syringe pump for nanoprecipitation) and mixing dynamics. Turbidity can be monitored in real-time.

- Protocol - Nanoprecipitation with Size Control:

- Dissolve the amphiphilic block copolymer in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., THF, acetone) at 1-5 mg/mL.

- Filter the polymer solution through a 0.45 µm PTFE filter.

- Using a syringe pump, add the organic solution to stirred milli-Q water (typical 1:10 v/v ratio) at a constant rate (e.g., 1 mL/min).

- Allow the mixture to stir uncovered for 4-6 hours to evaporate the organic solvent.

- Filter the resulting suspension through a 0.8 µm filter to remove aggregates.

- Characterize immediately by DLS.

Q2: My polymer library for drug encapsulation shows erratic loading efficiency when I vary composition (hydrophilic:hydrophobic ratio). How can I systematically map the optimal composition? A: Erratic loading indicates crossing a phase boundary in the parameter landscape. A systematic, high-throughput screening approach is needed.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Design a Matrix: Create a composition library where the hydrophobic block length is varied while holding the hydrophilic block constant, or vice versa.

- High-Throughput Formulation: Use a liquid handling robot to prepare formulations in 96-well plates.

- Direct Measurement: Quantify drug loading via HPLC-UV after disrupting nanoparticles with acetonitrile, rather than relying on indirect calculations.

- Protocol - Microscale Drug Loading Screening:

- Prepare stock solutions of polymer variants in DMSO (10 mg/mL) and drug (e.g., Docetaxel) in DMSO (5 mg/mL).

- Using a liquid handler, mix polymer and drug solutions in a 96-well plate to achieve desired polymer:drug ratios and compositions. Keep total DMSO <10%.

- Add phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to each well under gentle mixing to induce nanoprecipitation.

- Centrifuge the plate to pellet any aggregates or free drug crystals.

- Transfer supernatant to a new plate. Quantify unencapsulated drug in the supernatant via HPLC-UV.

- Calculate Loading Efficiency (%) = [(Total drug amount - Free drug amount) / Total drug amount] * 100.

Q3: When testing star vs. linear polymer architectures for controlled release, my release kinetics data is noisy and irreproducible. What are the key experimental pitfalls? A: Noisy release data commonly arises from sink condition failure and sample handling artifacts.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Maintain Sink Conditions: The release medium volume must be ≥10x the saturation volume of the drug. Use surfactants (e.g., 0.1% w/v Tween 80) in PBS to increase drug solubility.

- Control Temperature & Agitation: Use a thermostated shaker/incubator with consistent orbital shaking speed.

- Minimize Sampling Error: Use dedicated dialysis setups or centrifugal filter devices for each time point to avoid cumulative disturbance.

- Protocol - Robust Dialysis-Based Release Study:

- Prepare nanoparticle solution (1 mg/mL polymer in PBS with surfactant).

- Load 1 mL into a pre-soaked dialysis device (e.g., Float-A-Lyzer G2, 10 kDa MWCO).

- Immerse the device in 50 mL of release medium (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.1% Tween 80) in a 50 mL conical tube.

- Place the tube on a tube rotator in a 37°C incubator.

- At predetermined intervals, remove the entire tube. Take a 1 mL sample from the external medium and replace with 1 mL of fresh, pre-warmed release medium.

- Analyze drug concentration in samples via HPLC.

Table 1: Impact of Molecular Weight Dispersity (Đ) on Nanoparticle Characteristics

| Polymer Type | Nominal Mn (kDa) | Measured Đ (GPC) | Nanoparticle Size (nm, DLS) | PDI (DLS) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-PLGA A | 20-10 | 1.05 | 98.2 ± 3.1 | 0.08 | 85.5 ± 2.3 |

| PEG-PLGA B | 20-10 | 1.32 | 145.6 ± 25.7 | 0.21 | 72.1 ± 8.4 |

| PEG-PCL A | 15-8 | 1.08 | 82.5 ± 2.5 | 0.06 | 88.9 ± 1.7 |

Table 2: Drug Loading Efficiency vs. Hydrophobic Block Length (Constant Drug:Polymer Ratio)

| Polymer Architecture | Hydrophobic Block Length (kDa) | LogP (Drug: Paclitaxel) | Loading Efficiency (%) | Observed Nanoparticle Morphology (TEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear PEG-PLGA | 5 | 3.7 | 52.3 ± 5.1 | Spherical, some micelles |

| Linear PEG-PLGA | 10 | 3.7 | 78.9 ± 3.5 | Spherical, uniform |

| Linear PEG-PLGA | 15 | 3.7 | 81.2 ± 2.1 | Spherical & short rods |

| 4-arm star PEG-PCL | 8 (per arm) | 3.7 | 91.5 ± 1.8 | Spherical, very dense |

Visualizations

Bayesian Optimization Loop for Polymer Formulation

Linear vs Star Polymer Architecture & Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Example Product/Brand | Function in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Polymerization Kit | RAFT (Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer) Polymerization Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) | Enables synthesis of polymers with low dispersity (Đ) and precise block lengths, critical for defining the parameter landscape. |

| High-Throughput Formulation System | TECAN Liquid Handling Robot with Nano-Assembler Blaze module | Automates nanoprecipitation and formulation in 96/384-well plates for rapid screening of polymer parameter space. |

| Advanced Purification System | Preparative Scale Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) System (e.g., Agilent) | Isolates narrow molecular weight fractions from a polydisperse polymer batch, ensuring parameter consistency. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Plate Reader | Wyatt DynaPro Plate Reader II | Measures nanoparticle size and PDI directly in 384-well plates, integrating with HTS workflows. |

| Dialysis Device for Release | Float-A-Lyzer G2 (Spectrum Labs) | Provides consistent, large-volume sink conditions for reproducible in vitro drug release kinetics studies. |

| LogP Predictor Software | ChemDraw Professional or ACD/Percepta | Calculates partition coefficient (LogP) of drug molecules to rationally match polymer hydrophobicity for optimal loading. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs for Bayesian Optimization in Polymer-Based Drug Delivery

FAQs on Integrating Bayesian Optimization with Experimental Objectives

Q1: During iterative Bayesian optimization of polymer composition for sustained release, my model predictions and experimental results diverge sharply after the 5th batch. What could be the cause? A1: This is often due to an inaccurate surrogate model or an overly narrow parameter space. Implement the following protocol to diagnose and resolve:

Protocol: Surrogate Model Validation & Space Expansion

- Step 1: Re-evaluate your acquisition function. If using Expected Improvement (EI), check for over-exploitation. Temporarily switch to a Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) with a higher κ (e.g., κ=5) to encourage exploration of uncertain regions.

- Step 2: Perform a posterior check. Re-train the Gaussian Process (GP) model on all data (Batches 1-5). Generate predictions for 50 random points within your defined parameter bounds and compare variance. If variance is uniformly low (<0.1 scaled), your space may be exhausted.

- Step 3: Expand your parameter space logically. If optimizing for lactide:glycolide (LA:GA) ratio and molecular weight (MW), consider the expanded bounds in the table below.

- Step 4: Synthesize 2-3 new polymers from the expanded, high-uncertainty regions and measure release kinetics (see Release Kinetics Protocol). Add this data to retrain the GP.

Data Summary: Common Parameter Spaces for PLGA Nanoparticles

Parameter Typical Initial Range Suggested Expanded Range Performance Link LA:GA Ratio 50:50 to 85:15 25:75 to 95:5 Release Kinetics: Higher LA content slows hydrolysis, prolonging release. Polymer MW (kDa) 10 - 50 kDa 5 - 100 kDa Release Kinetics/Safety: Lower MW leads to faster erosion. Very low MW may increase burst release. Drug Loading (%) 1 - 10% w/w 0.5 - 20% w/w Safety/Release: High loading can cause crystallization and unpredictable release or cytotoxicity. PEGylation (%) 0 - 5% 0 - 15% Targeting/Safety: Reduces opsonization, prolongs circulation. >10% may hinder cellular uptake.

Q2: My targeted nanoparticle consistently shows poor cellular uptake in vitro despite high ligand density. How can I troubleshoot this targeting failure? A2: Poor uptake often stems from a "binding vs. internalization" issue or a hidden colloidal stability problem. Follow this systematic workflow.

- Protocol: Targeting Efficiency Diagnostic Workflow

- Step 1 - Confirm Ligand Activity: Perform a free ligand inhibition assay. Pre-incubate cells with soluble ligand (e.g., 100 µM folate for folate-targeted particles) for 30 min, then add nanoparticles. If uptake of targeted particles is still high, the issue is not specific receptor binding.

- Step 2 - Measure Hydrodynamic Diameter & PDI: Use DLS in complete cell culture media (37°C). Aggregation (>300 nm or PDI >0.25) will invalidate targeting. If aggregation occurs, revisit PEG density or use a stabilizer like HSA (0.1%).

- Step 3 - Check Surface Charge: Measure zeta potential in 10mM PBS (pH 7.4). A highly negative charge (< -30 mV) or positive charge (> +10 mV) can cause non-specific interactions or toxicity, masking active targeting.

- Step 4 - Internalization Pathway: Use specific inhibitors. Pre-treat cells with chlorpromazine (10 µg/mL) for clathrin-mediated, genistein (200 µM) for caveolae-mediated, or amiloride (1 mM) for macropinocytosis. Compare uptake vs. untreated cells to identify the dominant pathway.

Q3: How do I balance the multi-objective optimization of release profile (kinetics), targeting efficiency, and safety (low cytotoxicity) in a single Bayesian framework? A3: Use a constrained or composite multi-objective approach. Define a primary objective and treat others as constraints or combine them into a single score.

Protocol: Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Setup

- Step 1 - Define Quantitative Metrics: Assign a measurable output for each objective (see table below).

- Step 2 - Choose Optimization Strategy:

- Strategy A (Constrained): Maximize targeting efficiency (e.g., cellular uptake fold-change) subject to constraints:

Cumulative Release at 24h < 25%ANDCell Viability > 80%. - Strategy B (Composite): Create a unified objective function:

Score = w1*[Targeting] + w2*[Release Profile Similarity] + w3*[Viability]. Weights (w1, w2, w3) are set by researcher priority (e.g., 0.5, 0.3, 0.2).

- Strategy A (Constrained): Maximize targeting efficiency (e.g., cellular uptake fold-change) subject to constraints:

- Step 3 - Implement in Code: Use a library like

BoTorchorGPyOptthat supports constrained optimization or implements the composite function directly as the GP's training target.

Data Summary: Key Metrics for Multi-Objective Optimization

Objective Measurable Metric (Example) Ideal Target Range Assay Protocol Reference Release Kinetics Similarity factor (f2) vs. target profile f2 > 50 USP <711>; Sampling at t=1, 4, 12, 24, 48, 72h. Targeting Cellular Uptake Fold-Change (vs. non-targeted) > 2.0 Flow cytometry (FITC-labeled NPs), 2h incubation. Safety (in vitro) Cell Viability (%) at 24h (MTT assay) > 80% ISO 10993-5; Use relevant cell line (e.g., HepG2, THP-1).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Relevance to Bayesian Optimization |

|---|---|

| PLGA Polymer Library | Varied LA:GA ratios & molecular weights. Essential for defining the initial parameter space for the BO search. |

| DSPE-PEG-Maleimide | Functional PEG-lipid for conjugating thiolated targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) to nanoparticle surfaces. |

| Fluorescent Probe (DiD or DIR) | Hydrophobic near-IR dyes for nanoparticle tracking in in vitro uptake and in vivo biodistribution studies. |

| MTT Cell Viability Kit | Standardized colorimetric assay for quantifying cytotoxicity, a critical safety constraint in optimization. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | For purifying conjugated nanoparticles from free ligand, ensuring accurate ligand density measurements. |

| Zetasizer Nano System | Critical for characterizing hydrodynamic diameter, PDI, and zeta potential—key parameters influencing release and targeting. |

Visualizations

Bayesian Optimization Workflow for Drug Delivery

Targeting & Internalization Pathways

Multi-Objective Optimization Logic

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Surrogate Modeling Phase

Q1: My Gaussian Process (GP) model fails to converge or predicts nonsensical values when modeling polymer properties. What could be wrong? A: This is often due to poor hyperparameter initialization or an inappropriate kernel choice for the chemical parameter space. Polymer data often exhibits complex, non-stationary behavior.

- Check: Ensure your input features (e.g., monomer ratios, chain lengths, processing temperatures) are properly normalized (e.g., z-score).

- Protocol: Implement a protocol to test multiple kernels. Start with a standard Matérn kernel (e.g., Matérn 5/2) and a composite kernel (e.g.,

Linear + RBF). Use a maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) routine with multiple restarts (≥10) to find optimal hyperparameters. Validate on a held-out test set of known polymer data points. - Solution: If instability persists, switch to a Random Forest or a Bayesian Neural Network as an alternative surrogate, which can better handle discontinuities.

Q2: How do I handle categorical or discrete parameters (e.g., catalyst type, solvent class) within the continuous GP framework? A: Use one-hot encoding or a dedicated kernel for categorical variables.

- Protocol:

- One-hot encode all categorical parameters.

- Use a combined kernel: a continuous kernel (e.g., RBF) for numerical parameters multiplied by a categorical kernel (e.g., Hamming kernel) for the encoded dimensions.

- Alternatively, use a dedicated mixed-variable BO package like

BoTorchorDragonfly.

- FAQs Data Table:

| Issue | Primary Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP Model Divergence | Unscaled features, wrong kernel | Plot 1D posterior slices | Normalize data, use Matérn kernel |

| Poor Uncertainty Quantification | Inadequate data density | Check length-scale values | Increase initial DOE points |

| Categorical Parameter Failure | Improper encoding | Inspect covariance matrix | Implement one-hot + Hamming kernel |

Acquisition Function Phase

Q3: The optimizer keeps suggesting the same or very similar polymer formulation in consecutive loops. How can I encourage more exploration? A: The acquisition function is over-exploiting. Increase the exploration weight.

- Check: Monitor the standard deviation (uncertainty) of suggestions. If it's very low, the algorithm is not exploring uncertain regions.

- Protocol: For the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function, systematically increase the

betaparameter (e.g., from 2.0 to 4.0 or higher). For Expected Improvement (EI), consider adding a small noise term or using theq-EIvariant for batch diversity. - Solution: Switch to a portfolio of acquisition functions or use a entropy-based method like Predictive Entropy Search for more systematic exploration.

Q4: How do I set meaningful constraints (e.g., viscosity < a threshold, cost < budget) in the acquisition step? A: Use constrained Bayesian optimization.

- Protocol:

- Model each constraint with a separate surrogate model (GP classifier for binary, GP regressor for continuous).

- Formulate a constrained acquisition function, such as Constrained Expected Improvement (CEI).

- The probability of constraint satisfaction is multiplied with the standard EI value.

- FAQs Data Table:

| Symptom | Likely Culprit | Tuning Parameter | Alternative Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Clustering | High exploitation | Lower xi (EI), lower kappa (GP-UCB) |

Use Thompson Sampling |

| Ignoring Constraints | Unmodeled constraints | Constraint violation penalty | Model constraint as a separate GP |

| Slow Suggestion Generation | Complex AF optimization | Increase optimizer iterations | Use random forest surrogate for faster prediction |

Iterative Learning & Experimental Integration

Q5: Experimental noise is high, causing the BO loop to chase outliers. How can I make the loop more robust? A: Explicitly model noise and implement robust evaluation protocols.

- Check: Perform replicates (n≥3) for a few previous suggestions to estimate the experimental noise level.

- Protocol:

- Set the

alphaornoiseparameter in the GP model to the estimated noise variance. - Implement a replicate protocol: For each suggested point, perform 3 experimental replicates. Feed the mean property value to the surrogate model. The cost of replicates can be incorporated into the acquisition function.

- Set the

- Solution: Use a Student-t process as a surrogate, which has heavier tails and is more robust to outliers.

Q6: The experimental evaluation of a polymer sample is expensive/time-consuming. How can I optimize the loop for "batch" or parallel suggestions? A: Implement batch Bayesian optimization to suggest multiple points per cycle.

- Protocol: Use a batch acquisition function.

- Kriging Believer: Optimize the first point, add its predicted value to the dataset, re-optimize for the next point.

- q-EI/q-UCB: Use Monte Carlo methods to optimize a batch of

qpoints simultaneously for joint expected improvement. - This allows parallel synthesis and characterization of several polymer formulations in one experimental cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Polymer BO | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Robot | Automates preparation of polymer libraries from BO-suggested parameters (ratios, catalysts). | Enables rapid testing of 10s-100s of formulations per batch. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatograph (GPC) | Provides critical polymer properties: Molecular Weight (Mw, Mn) and Dispersity (Đ). Key target/constraint for BO. | Must be calibrated for the polymer class under study. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures thermal properties (Tg, Tm, crystallinity) which are common optimization targets. | Sample preparation consistency is critical for low noise. |

| Rheometer | Characterizes viscoelastic properties (complex viscosity, modulus), often a constraint or target. | Parallel plate geometry is common for polymer melts/solutions. |

| BO Software Stack | Core algorithmic engine. Python libraries: GPyTorch/BoTorch, scikit-optimize, Dragonfly. |

BoTorch is preferred for modern, modular BO with GPU support. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Tracks all experimental data, ensuring a clean, auditable link between BO suggestion and result. | Essential for reproducibility and dataset integrity. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Design of Experiments (DoE) for Polymer Space Exploration Objective: Generate an initial, space-filling dataset to train the first surrogate model. Method:

- Define the parameter space bounds (e.g., comonomer ratio: 0-100%, initiator concentration: 0.1-2.0 mol%, temperature: 60-120°C).

- Use a Sobol sequence or Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to select 5-10 points per parameter dimension. This ensures low discrepancy and good coverage.

- Synthesize and characterize polymers at these points using standardized methods (see Protocol 2).

- Record all data (parameters, property results) in the LIMS.

Protocol 2: Standardized Polymer Synthesis & Characterization (for BO Loop Evaluation) Objective: Ensure consistent, low-noise experimental feedback for the BO loop. Synthesis:

- Prepare: Based on BO suggestion, calculate masses/volumes of monomers, initiator, solvent using stoichiometry.

- Conduct Reaction: Use inert atmosphere (N2/Ar) if needed. Perform polymerization in controlled temperature vial or reactor.

- Precipitate & Purify: Terminate reaction, precipitate polymer into a non-solvent, filter, and dry under vacuum to constant weight. Characterization:

- GPC: Dissolve ~5 mg of purified polymer in eluent, filter (0.45 µm), inject. Record Mw, Mn, Đ.

- DSC: Seal ~5 mg of sample in a pan. Run heat/cool/heat cycle at 10°C/min under N2. Record Tg from the second heating ramp.

- Rheology: Prepare a disk sample. Perform a frequency sweep at the application-relevant temperature. Record complex viscosity at 1 rad/s.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: The Core Bayesian Optimization Iterative Loop

Title: Integrated Experimental-Computational BO Workflow

Title: Trade-off in Acquisition Function Decision

Building Your Bayesian Optimization Pipeline for Polymer Discovery

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During dynamic light scattering (DLS) for nanoparticle size characterization, my polymer sample shows a high polydispersity index (PDI > 0.3). What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A: High PDI often indicates poor polymerization control or aggregation. First, ensure your solvent is pure and fully degassed. Filter the sample through a 0.22 µm membrane syringe filter directly into a clean DLS cuvette. If the issue persists, consider optimizing your polymerization initiator concentration or reaction time. For Bayesian optimization workflows, log this PDI as a key output variable to be minimized.

Q2: My gel permeation chromatography (GPC) trace shows multiple peaks or significant tailing. How should I proceed before featurization?

A: Multiple peaks suggest incomplete monomer conversion or side reactions. Verify your polymerization stopped completely by using an inhibitor. Re-run the sample after passing it through a basic alumina column to remove residual catalyst. Do not featurize this data directly; the molecular weight distribution must be unimodal for reliable parameterization. Document the purification step in your metadata.

Q3: How do I handle missing values in my dataset of polymer properties (e.g., missing Tg for some formulations)?

A: Do not use simple mean imputation. For Bayesian optimization, employ a two-step strategy: 1) Flag the entry as "experimentally undetermined" in your data table. 2) Use a preliminary Gaussian process model on your complete features to predict the missing property value for initial prototyping only. The primary optimization loop must later target this formulation for experimental measurement to fill the gap.

Q4: When calculating descriptors for polymer chains (like topological indices), which software is recommended, and how do I format the output for the optimization pipeline?

A: RDKit and Polymer Informatics Platform (PIP) are standard. Generate SMILES strings for your repeat units. Calculate descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, fraction of rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) batch-wise. Format the output as a CSV where each row is a unique polymer formulation and columns are features. See Table 1 for essential descriptors.

Table 1: Key Polymer Descriptors for Featurization

| Descriptor | Typical Range | Measurement Technique | Relevance to BO Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Avg. Mol. Wt. (Mn) | 5 kDa - 500 kDa | GPC | Correlates with viscosity, Tg |

| Dispersity (Ð) | 1.01 - 2.5 | GPC | Indicates polymerization control |

| Glass Transition Temp. (Tg) | -50°C - 250°C | DSC | Predicts physical state at use temp |

| Hydrodynamic Diameter | 10 nm - 500 nm | DLS | Critical for nanoparticle formulations |

| End-group Functionality | 0.8 - 1.2 | NMR | Impacts conjugation efficiency |

Experimental Protocol: GPC Analysis for Bayesian Optimization Input

- Sample Prep: Dissolve 5-10 mg of purified polymer in 1 mL of eluent (e.g., THF for PS standards). Filter through a 0.45 µm PTFE filter.

- System Calibration: Inject a series of 5 narrow dispersity polystyrene standards covering the expected molecular weight range.

- Sample Run: Inject 100 µL of sample solution. Run at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30°C.

- Data Processing: Use the software to integrate peaks. Record Mn, Mw, and Ð.

- Data Logging: Enter the values into the master dataset with experiment ID linked to the polymerization parameters (e.g., initiator type, [M]/[I] ratio, time).

Experimental Protocol: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for Tg Determination

- Sample Prep: Accurately weigh 5-10 mg of solid, dry polymer into a sealed aluminum Tzero pan.

- Method: Equilibrate at -30°C. Ramp temperature at 10°C/min to 150°C (above expected Tg). Hold for 5 min to erase thermal history. Cool at 10°C/min to -30°C, then re-ramp at 10°C/min to 150°C (this second heating cycle is used for analysis).

- Analysis: Use the software's tangent method on the second heat cycle to determine the midpoint Tg.

- Featurization: Record the Tg value to the nearest 0.1°C. This is a critical target property for many polymer BO campaigns.

Data Pipeline for Polymer Bayesian Optimization

Polymer Input-Output Property Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Polymer Parameterization |

|---|---|

| Syringe Filters (0.22 & 0.45 µm, PTFE) | Critical for clarifying DLS and GPC samples by removing dust and aggregates that skew size and MW data. |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl3, DMSO-d6) | For NMR characterization to determine monomer conversion, end-group analysis, and copolymer composition. |

| Narrow Dispersity PS Standards | Essential for calibrating GPC/SEC systems to obtain accurate molecular weight and dispersity values. |

| Tzero Hermetic Aluminum Pans (DSC) | Ensure no solvent loss during Tg measurement, providing reliable and reproducible thermal data. |

| Basic Alumina (Brockmann I) | Used in purification columns to remove residual catalysts and inhibitors post-polymerization. |

| Inhibitor (e.g., BHT, MEHQ) | Added to monomer stocks for storage and to quench polymerizations precisely for kinetic studies. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During a Bayesian optimization loop for polymer glass transition temperature prediction, my Gaussian Process (GP) model is taking prohibitively long to train as the dataset grows past 200 samples. What are my options?

A1: This is a common scalability issue with standard GPs (O(n³) complexity). You have several actionable paths:

- Switch to a Sparse GP Approximation: Implement a variational sparse GP using libraries like GPyTorch. This induces a set of m inducing points (where m << n), drastically reducing complexity to O(n m²).

- Use a Random Forest (RF) Surrogate: RFs scale approximately O(n log n) for training and are very efficient for prediction, making them suitable for larger datasets common in high-throughput polymer screening.

- Protocol for Switching to Sparse GP:

- Install GPyTorch.

- Define a variational model with an

InducingPointKernel. - Initialize inducing points via k-means clustering on your existing data.

- Train using stochastic variational inference (SVI), which allows for mini-batching.

Q2: My Random Forest surrogate model for drug-polymer solubility seems to be overfitting the noisy experimental data, causing poor optimization performance. How can I tune it?

A2: Overfitting in RFs is often due to overly deep trees. Use the following tuning protocol:

- Increase

min_samples_leaf: Set this to a value between 5 and 20. This prevents leaves with few samples, smoothing predictions. - Limit

max_depth: Restrict tree depth (e.g., 10-30) to prevent memorization. - Increase

min_samples_split: Require more samples to split an internal node. - Use Out-of-Bag (OOB) Error: Set

oob_score=Trueto get an unbiased validation score without cross-validation. - Protocol: Perform a grid search over these parameters, using OOB error as the validation metric, before integrating the surrogate into the Bayesian optimization loop.

Q3: For optimizing polymer film morphology parameters, the acquisition function (e.g., EI) is not exploring effectively and gets stuck. Could my choice of surrogate kernel be the cause?

A3: Yes, especially for GP models. The default Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel assumes smooth, stationary functions. Polymer morphology landscapes can have discontinuities or sharp transitions.

- Solution: Use a composite kernel. A

Matern kernel(e.g., Matern 5/2) allows for less smooth functions. For categorical parameters (like solvent type), use aHamming kernelencoded alongside a continuous kernel using addition or multiplication. - Protocol: Construct and compare kernels:

RBF,Matern32,Matern52, and a composite(Matern52 + WhiteKernel)to model noise. Use log marginal likelihood on a held-out set to select the best.

Q4: I need uncertainty estimates from my Random Forest model to use in the acquisition function. How do I obtain well-calibrated predictive variances?

A4: Standard RFs provide a variance estimate based on the spread of predictions from individual trees, which can be biased.

- Use a method like Quantile Regression Forests (QRF) or Jackknife-based methods (e.g., implemented in

sklearnwithoob_score=Trueandbootstrap=True). These provide more reliable uncertainty intervals. - Protocol: Use the

sklearnForestRegressorwithbootstrap=True. Enableoob_scoreand calculate the variance across trees for each prediction. For critical applications, implement a Jackknife+ after bootstrap (JoaB) estimator as per recent literature for more robust intervals.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Surrogate Model Comparison for Polymer/Drug Formulation BO

| Feature | Gaussian Process (GP) | Random Forest (RF) |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability (n samples) | Poor (O(n³)); use sparse approx. for >~1000 | Excellent (O(n log n)) |

| Native Uncertainty Quantification | Natural, probabilistic | Derived from ensemble; requires calibration |

| Handling of Categorical Inputs | Requires special kernels (e.g., Hamming) | Native handling |

| Handling of Noisy Data | Explicit noise model (WhiteKernel) | Robust; but can overfit without tuning |

| Interpretability | Medium (via kernel parameters) | High (feature importance) |

| Best Use Case in Polymer BO | Small, expensive experiments (<200 data points) | Larger datasets, high-dimensional, or mixed parameter spaces |

Table 2: Recommended Hyperparameter Tuning Ranges

| Model | Hyperparameter | Recommended Tuning Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process | alpha (noise level) |

1e-5 to 1e-1 | Regularization, handles noise |

length_scale (RBF/Matern) |

Log-uniform (1e-2 to 1e2) | Determines function smoothness | |

nu (Matern Kernel) |

1.5, 2.5, ∞ (RBF) | Controls smoothness differentiability | |

| Random Forest | n_estimators |

100 to 1000 | More trees reduce variance |

max_depth |

5 to 30 (or None) | Limits overfitting | |

min_samples_leaf |

3 to 20 | Smooths predictions, prevents overfit | |

min_samples_split |

5 to 30 | Prevents spurious splits on noise |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking GP vs. RF Surrogate for a Known Polymer Property Dataset

Objective: Empirically select the best surrogate model for Bayesian Optimization of a target polymer property (e.g., viscosity).

- Data Preparation: Use a public dataset (e.g., Polymer Genome). Split into a initial training set (20 points) and a large hold-out test set.

- Model Training: Train a standard GP (RBF kernel) and a tuned RF on the initial set.

- Simulated BO Loop: For 50 iterations:

- Fit the surrogate to current data.

- Use Expected Improvement (EI) to select the next point to "evaluate."

- "Evaluate" by retrieving the true value from the hold-out set.

- Append the new data point.

- Metric: Track the best-found value over iterations. Repeat with 5 different random seeds. The surrogate leading to faster, more reliable convergence is preferred.

Protocol 2: Calibrating Random Forest Uncertainty for Acquisition

Objective: Improve the reliability of RF-predicted variances for use in UCB or EI.

- Train RF: Fit an RF regressor with

bootstrap=Trueandoob_score=True. - Calculate Jackknife Variance: For each prediction point

x:- Get the prediction from every tree

t_i(x). - Calculate the mean prediction.

- Compute the variance:

V_jack = (B-1)/B * Σ (t_i(x) - mean)^2, where B is the number of trees.

- Get the prediction from every tree

- Incorporate into BO: Use

μ(x) = mean predictionandσ(x) = sqrt(V_jack)when calculating your acquisition function.

Mandatory Visualization

Decision Flowchart for Surrogate Model Selection

Bayesian Optimization Workflow for Polymer Research

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools

| Item | Function in Surrogate Modeling & BO |

|---|---|

| GPyTorch / GPflow | Libraries for flexible, scalable Gaussian Process modeling, enabling sparse GPs for larger datasets. |

| scikit-learn | Provides robust implementations of Random Forest regressors and essential data preprocessing tools. |

| Bayesian Optimization Libraries (BoTorch, scikit-optimize) | Frameworks that provide acquisition functions, optimization loops, and integration with GP/RF surrogates. |

| Chemical Descriptor Software (RDKit, Dragon) | Generates numerical feature vectors (e.g., molecular weight, functional groups) from polymer/drug structures for the model input. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotics | Automates the synthesis and testing of polymer formulations, generating the data needed to train and update the surrogate model efficiently. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My optimization seems stuck, repeatedly sampling near the same point. The Expected Improvement (EI) value is near zero everywhere. What is happening and how do I fix it?

A1: This is a classic sign of over-exploitation, often due to an incorrectly scaled or too-small "exploration" parameter.

- For EI & Probability of Improvement (PI): The issue is likely an overly small

xi(orepsilon) parameter, which controls exploration. Ifxi=0, the algorithm becomes purely greedy. - For UCB: The

kappaparameter is too small, over-weighting the mean (exploitation) vs. the uncertainty (exploration). - Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Diagnose: Plot your acquisition function alongside the model's mean and confidence intervals. You will see EI/PI is flat near zero, or UCB mirrors the mean too closely.

- Action: Increase the exploration parameter incrementally.

- EI/PI: Increase

xifrom a default of0.01to0.05or0.1. This makes improvements relative to the best observationy* + ximore probable. - UCB: Increase

kappafrom a default of2.576to3.5or5. This gives more weight to uncertain regions.

- EI/PI: Increase

- Validate: Run the next few iterations and observe if the algorithm proposes points in less-explored regions.

Q2: My optimization is behaving erratically, jumping to very distant, unexplored regions instead of refining promising areas. Why?

A2: This is a sign of over-exploration.

- For EI & PI: The

xiparameter is set too high. The algorithm is seeking improvements over an unrealistically optimistic target. - For UCB: The

kappaparameter is too large, causing it to chase pure uncertainty without regard for performance. - Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Diagnose: Check if the proposed point lies far outside the data-dense region with a very high standard deviation.

- Action: Systematically reduce the exploration parameter.

- Advanced Check: Ensure your Gaussian Process kernel length scales are appropriate for your parameter space. An excessively long length scale can cause this by over-estimating uncertainty far from data points.

Q3: How do I choose between EI, UCB, and PI for my polymer property optimization goal?

A3: The choice depends on your primary objective within the polymer parameter space. Refer to the decision table below.

Table 1: Acquisition Function Selection Guide for Polymer Research

| Your Primary Goal | Recommended Function | Key Parameter | Rationale for Polymer Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Find the global maximum efficiently with balanced exploration/exploitation. | Expected Improvement (EI) | xi (Exploration weight) |

The default and robust choice. Effectively trades off the probability and magnitude of improvement, ideal for navigating complex, multi-modal polymer response surfaces. |

| Maximize a property (e.g., tensile strength) as quickly as possible, accepting good-enough solutions. | Probability of Improvement (PI) | xi (Exploration weight) |

More exploitative. Use when you want to climb to a good region of polymer formulation space rapidly, but may get stuck in a local maximum. |

| Characterize the entire response surface or ensure no promising region is missed. | Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | kappa (Exploration weight) |

Explicitly tunable for exploration. Excellent for initial scans of a new polymer system to map the landscape before targeted optimization. |

| Meet a specific target property threshold (e.g., degradation time > 30 days). | Expected Improvement (EI) or PI | Target y* (Threshold) |

Set the target y* to your threshold. EI is generally preferred as it considers how much you exceed the threshold. |

Q4: Can you provide a standard experimental protocol for comparing EI, UCB, and PI on my polymer dataset?

A4: Yes. Follow this benchmark protocol.

- Data Preparation: Reserve a historical dataset of polymer formulations (e.g., monomer ratios, initiator concentrations, reaction temperatures) and their measured target property (e.g., molecular weight, yield).

- Initialization: Start each optimization algorithm from the same small, random subset of your data (e.g., 5 initial points).

- Parameter Setting: Use standard parameters for a fair baseline:

EI(xi=0.01),PI(xi=0.01),UCB(kappa=2.576). Use the same Gaussian Process kernel (e.g., Matérn 5/2) for all. - Simulated Experiment Loop:

- For each algorithm iteration

i: - The algorithm proposes the next polymer formulation to "test".

- Retrieve the actual property value for that formulation from your reserved dataset (simulating an experiment).

- Add this (formulation, value) pair to the algorithm's training data.

- Record the current best observed value.

- For each algorithm iteration

- Analysis: Plot Iteration vs. Current Best Value for all three functions. The most efficient function for your landscape will show the fastest ascent to the highest value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for Bayesian Optimization in Polymer Science

| Item / Solution | Function in the Optimization Workflow |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regression Model | The surrogate model that learns the nonlinear relationship between polymer formulation parameters and the target property, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates. |

| Matérn (ν=5/2) Kernel | The default covariance function for the GP; it effectively models typically smooth but potentially rugged polymer property landscapes. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) Algorithm | The acquisition function that calculates the expected value of improvement over the current best, guiding the next experiment. |

| Parameter Space Normalizer | Scales all polymer input parameters (e.g., %, °C, mL) to a common range (e.g., [0, 1]), ensuring the kernel and optimization process are numerically stable. |

| Experimental Data Logger | A structured database (e.g., electronic lab notebook) to record all formulation inputs and measured outputs, which is essential for training and validating the GP model. |

Visualization: Acquisition Function Decision Logic

Title: Decision Logic for Choosing an Acquisition Function

Technical Support Center

This support center integrates Bayesian optimization (BO) as a core framework for troubleshooting PLGA nanoparticle formulation and characterization. The following guides address common experimental pitfalls within the polymer parameter space.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During BO-guided formulation, my nanoparticles exhibit low encapsulation efficiency (EE%) despite high drug loading targets. What are the primary culprits?

- A: This often stems from a mismatch between your selected parameters. Key factors to re-examine:

- Polymer MW & Drug Solubility: Low MW PLGA (e.g., 10-20 kDa) degrades too quickly, causing drug leakage. For hydrophobic drugs, very high MW (>75 kDa) can hinder diffusion, but may improve EE. Use BO to model the interaction between

PLGA_MW,Drug_LogP, andEE. - Organic Solvent Choice: Ethyl acetate, while less toxic, can lower EE for highly water-soluble drugs compared to dichloromethane. Consider solvent

logPas a parameter in your BO model. - Aqueous Phase Additives: Insufficient stabilizer (e.g., PVA concentration <1%) leads to aggregation and drug loss. Ensure your BO algorithm's constraints include

PVA_Concentration(%, w/v) as a continuous variable (typical range 0.5-3%).

- Polymer MW & Drug Solubility: Low MW PLGA (e.g., 10-20 kDa) degrades too quickly, causing drug leakage. For hydrophobic drugs, very high MW (>75 kDa) can hinder diffusion, but may improve EE. Use BO to model the interaction between

Q2: My in vitro release profile shows a "burst release" >40% in 24 hours, not the desired sustained kinetics. How can I adjust my BO search space to correct this?

- A: Burst release indicates surface-associated drug. Refine your BO parameter space by prioritizing these variables:

- Increase Lactide:Glycolide (L:G) Ratio: Shift search towards higher L:G ratios (e.g., 75:25 or 85:15). The more hydrophobic lactide slows hydration and degradation.

- Optimize Nanoparticle Size & Density: Aim for smaller, denser particles. In your protocol, increase homogenization speed or sonication energy (

Joules/mL) as a tunable input. A denser polymer matrix retards initial diffusion. - Introduce a Core-Shell Design: Consider a double emulsion (W/O/W) for hydrophilic drugs. Add

Emulsion_Type(Single vs. Double) as a categorical parameter to your BO run.

Q3: The BO algorithm suggests a formulation with a very high polymer-to-drug ratio, making it cost-prohibitive for scale-up. How can I incorporate cost constraints?

- A: This is a multi-objective optimization problem. Modify your BO approach:

- Define a Cost-Aware Acquisition Function: Create a composite objective function that balances

Sustained_Release_Score(e.g., % release at target day) with aCost_Penaltybased onPLGA_mg_per_dose. - Set a Hard Constraint: In the BO search space, set an upper limit for the

Polymer_to_Drug_Ratiovariable (e.g., ≤ 30:1) based on preliminary cost analysis. - Explore Alternative Excipients: Allow the model to evaluate lower-cost stabilizers like poloxamers alongside PVA by including

Stabilizer_Typeas a parameter.

- Define a Cost-Aware Acquisition Function: Create a composite objective function that balances

Q4: After BO-recommended scale-up, my particle size distribution (PSD) widens significantly. What process parameters did the lab-scale model overlook?

- A: The BO model likely used static process parameters. For scale-up, you must dynamicize them:

- Scale-Dependent Energy Input: Swap

Sonication_TimeforVolumetric_Energy_Input(kJ/mL) as a critical BO parameter. - Mixing Dynamics: Include

Reynolds_Numberin the agitation step or the feed rate of organic phase into aqueous phase (mL/min) as a tunable variable. - Purification Consistency: Ensure diafiltration or centrifugation parameters (e.g.,

G-Force × Timeproduct) are consistent and modeled.

- Scale-Dependent Energy Input: Swap

Table 1: Impact of PLGA Properties on Nanoparticle Characteristics & Release

| Parameter | Tested Range | Effect on Size (nm) | Effect on Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Impact on Release (t50%) | BO Recommendation Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L:G Ratio | 50:50 to 85:15 | 150 → 220 (Increase) | 65% → 88% (Increase) | 3 days → 21 days (Increase) | High |

| Molecular Weight | 10 kDa to 75 kDa | 120 → 250 (Increase) | 45% → 82% (Increase) | 2 days → 14 days (Increase) | High |

| End Group | Ester (-COOH) | ~180 | ~75% | Moderate Burst (~30%) | Medium |

| Capped (-CH₃) | ~170 | ~70% | Higher Burst (~40%) | Medium |

Table 2: Bayesian Optimization Results vs. Traditional OFAT Approach

| Metric | Traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiments to Optimum | 45-60 | 15-25 | ~60% Reduction |

| Optimal t50% (Days) | 10.2 ± 1.5 | 14.8 ± 0.7 | +45% Prolongation |

| Optimal EE% | 78% ± 5% | 85% ± 2% | +7% Absolute |

| Polymer Used (g) | ~12.5 | ~4.2 | ~66% Savings |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: BO-Informed Nanoparticle Preparation (Single Emulsion-Solvent Evaporation)

- Parameter Initialization: Define BO search space:

PLGA_LG_Ratio(categorical: 50:50, 75:25),PLGA_MW(continuous: 15-50 kDa),Drug_Polymer_Ratio(continuous: 1:10 to 1:30),PVA_Concentration(continuous: 0.5-2.5%). - Organic Phase: Dissolve

X mgof PLGA (per BO suggestion) and drug in 3 mL of dichloromethane (DCM). - Aqueous Phase: Dissolve

Y mgof PVA (per BO suggestion) in 30 mL of deionized water. - Emulsification: Add organic phase to aqueous phase under magnetic stirring (500 rpm). Immediately emulsify using a probe sonicator at

Z Joules/mL(BO-tunable) on ice. - Solvent Evaporation: Stir the emulsion overnight at room temperature to evaporate DCM.

- Purification: Centrifuge at 18,000 rpm for 30 min, wash pellet twice with water, and resuspend via sonication.

- Characterization: Measure size (PDI) via DLS, determine EE% via HPLC (lyophilized nanoparticles dissolved in acetonitrile).

- Feedback to BO: Input

Size,PDI,EE%, andBurst_Release_%(from release assay) as objective values for the next iteration.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Release Study under Sink Conditions

- Sample Preparation: Place nanoparticle suspension equivalent to 2 mg of drug into a pre-swelled dialysis bag (MWCO 12-14 kDa).

- Release Medium: Immerse bag in 50 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 0.1% w/v Tween 80 to maintain sink conditions.

- Incubation: Agitate continuously at 100 rpm and 37°C.

- Sampling: At predetermined intervals (1, 4, 8, 24, 48, 96, 168 hours etc.), withdraw 1 mL of external medium and replace with fresh pre-warmed medium.

- Analysis: Quantify drug concentration using HPLC/UV-Vis. Plot cumulative release vs. time.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: Bayesian Optimization Workflow for PLGA Formulation

Title: PLGA Degradation & Drug Release Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PLGA Nanoparticle Optimization

| Item | Function/Description | Key Consideration for BO |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Various L:G, MW, Endcap) | Biodegradable polymer matrix; core component defining release kinetics. | Primary tunable variable. Stock multiple grades. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Stabilizer/surfactant; critical for controlling particle size and PDI. | Concentration and molecular weight are tunable parameters. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Common organic solvent for PLGA. Fast evaporation rate influences particle morphology. | May be a fixed variable; can be swapped for ethyl acetate. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard medium for in vitro release studies (pH 7.4). | Maintains physiological pH. Additive (e.g., Tween) ensures sink conditions. |

| Dialysis Tubing (MWCO 12-14 kDa) | For separating nanoparticles from release medium during kinetic studies. | MWCO must be significantly smaller than nanoparticle size. |

| Sonication Probe | Provides high-energy input for creating fine oil-in-water emulsions. | Energy input (J/mL) is a critical, scalable process parameter. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic diameter, PDI, and zeta potential. | Provides immediate feedback for size objective in BO. |

| HPLC-UV/Vis System | Quantifies drug concentration for encapsulation efficiency and release kinetics. | Essential for obtaining accurate objective function values. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Hybrid Nanoparticle Formulation

Q1: Why are my hybrid nanoparticles forming aggregates immediately after preparation? A: This is typically due to rapid, uncontrolled mixing or incorrect buffer conditions. Implement a controlled mixing protocol using a microfluidic device or staggered pipetting. Ensure your aqueous buffer (e.g., citrate, pH 4.0) and polymer-lipid organic solution are at the same temperature (e.g., 25°C) prior to mixing. Aggregation can also indicate an overly high concentration of cationic polymer; consider reducing the amine-to-phosphate (N:P) ratio incrementally from 30 to 10.

Q2: My mRNA encapsulation efficiency is consistently below 70%. How can I improve it? A: Low encapsulation often stems from suboptimal complexation. First, verify the integrity of your mRNA via gel electrophoresis. Then, systematically adjust two parameters:

- Incubation Time: Increase the complexation time from 20 minutes to 60 minutes at room temperature before buffer exchange.

- Order of Addition: If using a lipid component (e.g., DOTAP, DOPE), try adding the pre-formed polymer-mRNA polyplex to the lipid film, instead of mixing all components simultaneously. Evaluate encapsulation using a Ribogreen assay.

Q3: How do I differentiate between free mRNA and nanoparticle-associated mRNA in my gel shift assay? A: A standard agarose gel may not sufficiently retain nanoparticles. Use a heparin displacement assay. Incalate your nanoparticles with increasing concentrations of heparin (0-10 IU/µg polymer) for 30 min before loading on the gel. The anionic heparin competes with mRNA, causing a dose-dependent release visible as a band shift. The minimal heparin dose causing complete release indicates binding strength.

Q4: I observe high cytotoxicity in my in vitro transfection experiments. What are the likely causes? A: Cytotoxicity from polymer-lipid hybrids is frequently linked to excessive surface charge or poor biodegradability.

- Check Surface Charge: Measure the zeta potential. A highly positive potential (> +25 mV) can cause membrane disruption. Incorporate more neutral or PEGylated lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG) to shield charge.

- Assess Polymer Component: If using high-molecular-weight cationic polymers (e.g., PEI), switch to bioreducible or lower molecular weight variants. Run an MTT assay comparing your hybrid to a lipofectamine control at identical mRNA doses.

Q5: My formulations show good in vitro performance but fail in vivo. What should I re-evaluate? A: This highlights a common formulation-screening gap. Focus on serum stability and particle size distribution.

- Serum Stability Test: Incubate nanoparticles with 50% FBS at 37°C. Measure particle size (DLS) and PDI at 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes. A >20% increase in size indicates aggregation in serum, leading to rapid clearance.

- Size Homogeneity: Ensure a Polydispersity Index (PDI) < 0.2 via DLS. Use size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to purify a monodisperse population before in vivo administration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the optimal N:P ratio range for polymer-lipid hybrids containing mRNA? A: The optimal range is formulation-dependent but typically lies between 10 and 30 for initial screening. Use the Bayesian optimization loop to refine this parameter alongside lipid-to-polymer weight ratios.

Q: Which characterization techniques are non-negotiable for a new hybrid formulation? A: The core characterization suite includes:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): For hydrodynamic diameter and PDI.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: For surface charge.

- Ribogreen Assay: For mRNA encapsulation efficiency.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) or Cryo-EM: For morphology.

- In vitro transfection & cell viability: For functionality and safety.

Q: How do I incorporate Bayesian optimization into my screening workflow? A: Frame your experiment within the Bayesian optimization loop. Define your parameter space (e.g., polymer MW, lipid type, N:P ratio, PEG %). Choose an objective function (e.g., maximize encapsulation efficiency * in vitro expression * cell viability). After each small batch of experiments, input the data into the model to predict the next, most informative set of parameters to test.

Q: What is a critical but often overlooked step in the preparation of polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles? A: The drying and hydration of the lipid component. Ensure the lipid film is completely desiccated under vacuum for at least 2 hours before hydration with the polymer-containing buffer. Incomplete drying leads to heterogeneous lipid vesicles and inconsistent hybrid formation.

Q: How can I assess endosomal escape capability? A: Perform a confocal microscopy assay using a pH-sensitive dye (e.g., Lysosensor Green). Co-localization of nanoparticles (labeled with a red fluorophore) with acidic vesicles over time (0-12 hours) indicates endosomal trapping. A decrease in co-localization after 4-6 hours suggests successful escape.

Table 1: Benchmarking of Common Cationic Polymers in Hybrid Formulations

| Polymer | Typical MW (kDa) | Optimal N:P Range | Typical EE% | Common Cytotoxicity (vs. Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene imine) (PEI) | 10-25 | 5-15 | 80-95% | 60-80% viability |

| Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) | 10-15 | 10-30 | 70-90% | 70-85% viability |

| Poly(β-amino esters) (PBAE) | 10-20 | 20-60 | 85-98% | 80-95% viability |

| Chitosan | 10-50 | 40-100 | 50-80% | >90% viability |

Table 2: Impact of Helper Lipids on Hybrid Nanoparticle Properties

| Helper Lipid (with cationic polymer) | Function | Typical Molar Ratio | Effect on Size (nm) | Effect on Transfection Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) | Fusogenic, promotes endosomal escape | 30-50% | Increase by 10-20 | Significant increase |

| Cholesterol | Membrane stability, in vivo longevity | 40-50% | Minimal change | Moderate increase |

| DSPE-PEG2000 | Steric stabilization, reduces clearance | 1-10% | Increase by 5-15 | Often decreases in vitro, increases in vivo |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Microfluidic Preparation of Polymer-Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles Objective: Reproducible, scalable formulation of hybrid nanoparticles. Materials: Syringe pump, staggered herringbone micromixer chip, syringes, tubing, cationic polymer solution (in 25 mM citrate buffer, pH 4.0), lipid mix (in ethanol), mRNA (in citrate buffer). Steps:

- Prepare the organic phase: Dissolve cationic lipid (e.g., DOTAP, 2 mM) and helper lipid (e.g., DOPE, 2 mM) in ethanol. Mix with a biodegradable polymer (e.g., PBAE, 5 mg/mL) solution in ethanol.

- Prepare the aqueous phase: Dilute mRNA to 0.1 mg/mL in 25 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

- Load the two phases into separate syringes. Connect to the microfluidic chip.

- Set a total flow rate (TFR) of 12 mL/min and a flow rate ratio (FRR, aqueous:organic) of 3:1.

- Collect the effluent in a vial. Stir gently for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Use a desalting column or tangential flow filtration to exchange the buffer to 1x PBS (pH 7.4).

Protocol 2: Heparin Competition Gel Shift Assay for mRNA Encapsulation Objective: Qualitatively assess mRNA binding strength and completeness of encapsulation. Materials: Agarose, TBE buffer, heparin sodium salt, loading dye, gel imager. Steps:

- Prepare a 1% agarose gel in 1x TBE with a safe nucleic acid stain.

- Aliquot 10 µL of nanoparticle sample (containing ~200 ng mRNA).

- Prepare heparin solutions in nuclease-free water (e.g., 0.1, 1, 5, 10 IU/µL).

- Add 2 µL of each heparin solution to separate aliquots. Incubate 30 min at RT.

- Add loading dye and load onto the gel. Include free mRNA as control.

- Run gel at 90V for 45 minutes. Image. Complete encapsulation is indicated by no band in the 0-1 IU heparin lanes, with a band appearing at higher heparin doses.

Visualization: Diagrams and Workflows

Bayesian Optimization Loop for Formulation

Polymer-Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticle Formulation Workflow

Intracellular mRNA Delivery Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Hybrid mRNA Delivery | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Cationizable/Biodegradable Polymer | Condenses mRNA via electrostatic interaction, should promote endosomal escape and degrade to reduce toxicity. | Poly(β-amino ester) (PBAE, e.g., Polyjet), Branched PEI (bPEI, 10kDa). |

| Ionizable/Cationic Lipid | Enhances mRNA complexation, bilayer formation, and often aids endosomal escape. | DLin-MC3-DMA, DOTAP, DOTMA. |

| Fusogenic Helper Lipid | Promotes non-bilayer phase formation, facilitating endosomal membrane disruption and escape. | DOPE, Cholesterol. |

| PEGylated Lipid | Provides a hydrophilic corona to reduce aggregation, opsonization, and extend circulation time. | DSPE-PEG2000, DMG-PEG2000. |

| pH-Sensitive Fluorescent Dye | To track nanoparticle localization and endosomal escape efficiency via confocal microscopy. | Lysosensor Green, pHrodo. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled mRNA | For direct visualization of nanoparticle unpacking and mRNA release kinetics. | Cy5-mRNA, FAM-mRNA. |

| Heparin Sodium Salt | A competitive polyanion used in displacement assays to test mRNA binding strength. | Heparin from porcine intestinal mucosa. |

| Quant-iT RiboGreen Assay Kit | Highly sensitive fluorescent assay for quantifying both encapsulated and free mRNA. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, R11490. |

| Microfluidic Mixing Device | Enables reproducible, scalable nanoprecipitation with controlled mixing kinetics. | Dolomite Microfluidics Mitos Syringe Pump, Precision NanoSystems NanoAssemblr. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: When using GPyTorch for my polymer property model, I encounter "CUDA out of memory" errors, even with small datasets. How can I resolve this?

A: This is common when using exact Gaussian Process inference. For Bayesian optimization of polymer parameters, use approximate methods.

- Solution: Switch from

ExactGPto a scalable model usingSingleTaskVariationalGPor use inducing points withApproximateGP. Reduce the size of the inducing point set. - Protocol: Modify your model initialization:

Q2: Scikit-Optimize (skopt) optimizers are slow to converge on my high-dimensional polymer parameter space (e.g., 10+ variables like monomer ratio, chain length, etc.). What tuning can improve performance?

A: The default gp_minimize uses a Constant mean function and Matern kernel. For complex polymer spaces, adjust the surrogate model.

- Solution: Use

skopt.Optimizerdirectly with a customized GPyTorch surrogate model for better priors. Increasen_initial_pointsto at least 10 times your dimensionality. - Protocol:

- Ensure all parameters have appropriate bounds (

dimensions). - Use

acq_func="EIps"(Expected Improvement per second) if evaluation times vary. - Set

acq_optimizer="lbfgs"for more robust acquisition function optimization. - Key Tuning Table:

- Ensure all parameters have appropriate bounds (

Q3: How can I integrate a custom laboratory synthesis robot (e.g., for polymer synthesis) into a closed-loop Bayesian optimization workflow with these libraries?

A: Integration requires a stable data pipeline and state management.

- Solution: Build a lightweight middleware (e.g., using FastAPI or a simple Python daemon) that bridges the BO system and the lab hardware's API. Use a shared database (SQLite/PostgreSQL) or a structured file (JSON) to log experiments and queue suggested parameters.

- Protocol:

- Workflow Setup: Implement the following automated loop.

- Error Handling: Build in checks for synthesis failure (e.g., yield below threshold) to flag data points for the BO model.

Q4: I get "Linear algebra errors" (non-positive definite matrices) in GPyTorch during fitting of my polymer dataset. What causes this and how do I fix it?

A: This is often due to numerical instability from duplicate or very similar input parameter sets, or an improperly scaled output.

- Solution: Add a small

jitter(1e-6) to the covariance matrix. Normalize your input parameters (e.g., usingsklearn.StandardScaler) and consider normalizing target properties. - Protocol:

Experimental Protocols for Bayesian Optimization in Polymer Research

Protocol 1: Benchmarking GPyTorch Kernels for Polymer Property Prediction

- Objective: Identify the optimal kernel for a Gaussian Process surrogate modeling polymer tensile strength from synthesis parameters.

- Methodology:

- Data: Use historical data for 200 polymer formulations (parameters: catalyst concentration, temperature, reaction time).

- Models: Train separate exact GP models (GPyTorch) with RBF, Matern 2.5, and Spectral Mixture kernels. Use 80/20 train-test split.

- Training: Use Adam optimizer, maximize marginal log likelihood for 200 iterations.

- Evaluation: Compare Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Negative Log Predictive Density (NLPD) on the test set.

- Quantitative Data Summary:

| Kernel Type | MAE (MPa) | NLPD | Training Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBF | 4.2 | 1.2 | 45 |

| Matern 2.5 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 48 |

| Spectral Mixture (k=4) | 3.5 | 0.9 | 112 |

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop Optimization of Polymer Viscosity