Beyond Trial and Error: The Next Frontier of AI in Materials Discovery

This article explores the evolving role of Artificial Intelligence in accelerating and transforming materials discovery.

Beyond Trial and Error: The Next Frontier of AI in Materials Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the evolving role of Artificial Intelligence in accelerating and transforming materials discovery. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of foundational principles, cutting-edge methodologies, critical challenges, and validation frameworks. We examine how AI is moving beyond initial hype to address practical bottlenecks, from generative model design and experimental integration to ensuring reliability and guiding ethical development, ultimately charting a course toward a new paradigm of intelligent, self-driving laboratories for biomedical and clinical innovation.

AI in Materials Science: From Foundational Concepts to Current State-of-the-Art

The discovery of new functional materials and molecules has historically followed an Edisonian approach: iterative, trial-and-error experimentation guided by empirical observation and researcher intuition. This process is often slow, costly, and limited by human cognitive bias. The contemporary shift is toward a closed-loop, AI-driven discovery paradigm, where artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) form the core of a hypothesize-design-test-analyze cycle. This paradigm, central to future research directions in AI for materials discovery, leverages high-throughput computation, automated experimentation (robotics), and data-centric AI models to explore vast combinatorial spaces orders of magnitude faster than traditional methods.

Core AI Methodologies in Modern Discovery

The following table summarizes key quantitative benchmarks of AI-driven versus traditional discovery, based on recent literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Discovery Paradigms

| Metric | Edisonian/Traditional Approach | AI-Driven Approach | Key Study / Source (2023-2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (Experiments/Day) | 1-10 | 100 - 10,000+ | Nature, 2023: A robotic platform achieved >1,000 solar cell experiments/day. |

| Discovery Cycle Time | Months to Years | Days to Weeks | Sci. Adv., 2024: New solid-state electrolyte identified in 42 days via closed-loop AI. |

| Candidate Screening Rate | ~10² compounds/year | ~10⁸ compounds/virtual screen | ChemRxiv, 2024: Generative model screened 100M+ organic molecules for OLEDs. |

| Success Rate (Hit-to-Lead) | <10% | Reported up to 50-80%* | *Domain-dependent; ACS Cent. Sci., 2023: ML-guided synthesis raised success rate to ~65%. |

| Typical R&D Cost per Candidate | $1M - $10M+ | Potentially reduced by 50-90% | Industry analysis (2024) projects ~70% cost reduction in preclinical phases. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for an AI-Driven Closed-Loop Campaign

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for autonomous materials discovery, integrating generative AI, robotic synthesis, and characterization.

Protocol Title: Closed-Loop Discovery of Novel Perovskite-Inspired Photovoltaic Materials

Objective: To autonomously discover and optimize a novel lead-free, stable photovoltaic material.

Step 1: Initial Dataset Curation & Model Training

- Input Data: Gather structured data from sources like the Materials Project, ICSD, and relevant literature. Key features include formation energy, band gap (experimental & computed), crystal structure (space group, Wyckoff positions), ionic radii, and stability metrics.

- Preprocessing: Clean data, handle missing values, and standardize formats. Use

pymatgenfor crystal featurization. - Model Training: Train a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) or Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE) on the crystal structure data. Concurrently, train a Graph Neural Network (GNN) property predictor (for band gap, stability score) on the featurized data.

Step 2: AI-Driven Candidate Generation & Selection

- Generation: Sample the latent space of the trained generative model to propose novel crystal compositions and structures outside the training set.

- Prediction & Filtering: Use the trained property predictor to estimate the band gap (target: 1.2-1.8 eV) and thermodynamic stability (formation energy < 0.2 eV/atom) of generated candidates.

- Down-Selection: Apply multi-objective Bayesian optimization to balance property predictions. Select the top 50 candidates for stability validation via Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations (using VASP or QE).

Step 3: Robotic Synthesis & Characterization

- Automated Synthesis:

- Reagent Preparation: Use a liquid-handling robot to dispense precursor solutions (e.g., metal halide salts in DMSO) into well plates.

- Reaction Execution: Perform reactions in an automated glovebox with a robotic arm transferring plates to a spin-coater for thin-film deposition, followed by a thermal annealing station.

- Conditions Varied: Robotically vary annealing temperature (80-180°C), time (5-60 min), and precursor stoichiometry (±10%).

- High-Throughput Characterization:

- Inline Optical Spectroscopy: Measure UV-Vis absorption spectra immediately after annealing to derive preliminary band gaps.

- Automated XRD: Transfer samples via robotic stage to an X-ray diffractometer for phase identification.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Mapping: Perform automated PL mapping to assess film homogeneity and optoelectronic quality.

Step 4: Data Pipeline & Model Retraining

- Data Structuring: Automatically parse characterization results (XRD patterns, absorption spectra) into structured numerical descriptors (e.g., peak positions, intensities, FWHM, Tauc plot band gap).

- Feedback Loop: Append the new experimental data (synthesis parameters → resulting structure/properties) to the training database.

- Model Update: Finetune or retrain the generative and predictive models weekly with the expanded dataset, improving their accuracy for the next discovery cycle.

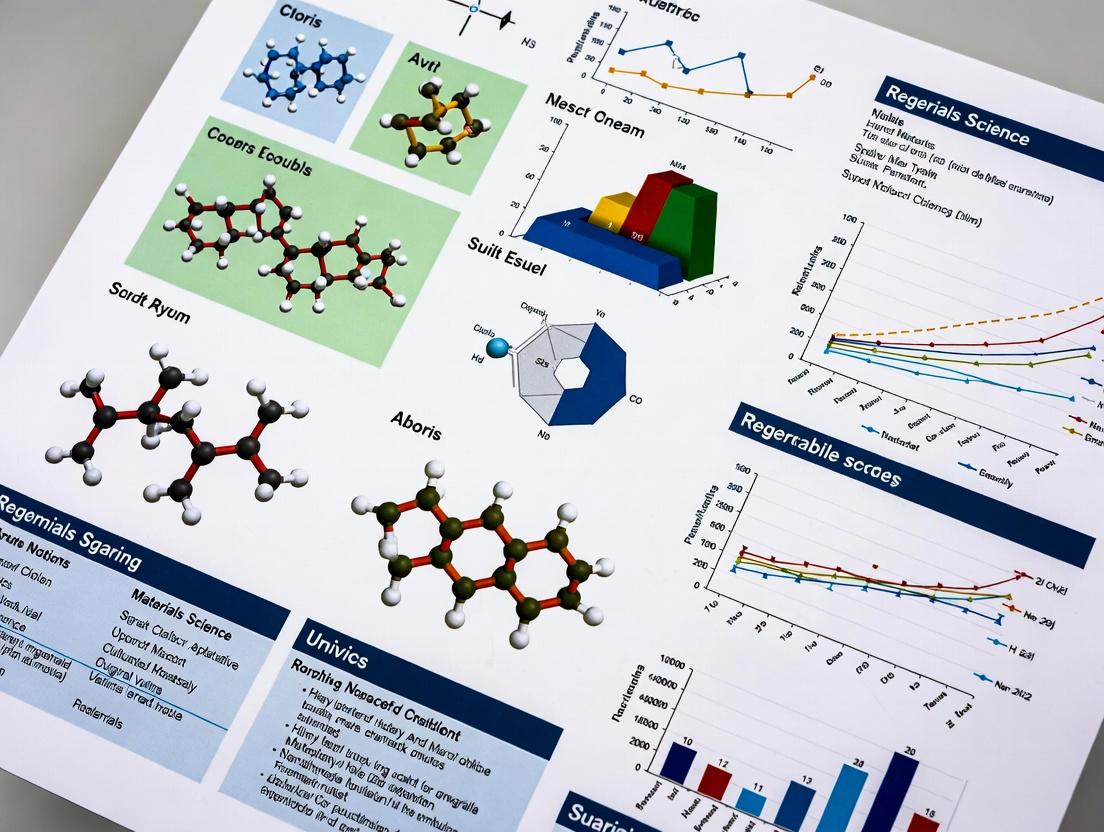

Visualization of the AI-Driven Discovery Workflow

AI-Driven Closed-Loop Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an AI-Driven Discovery Laboratory

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function in the Workflow | Key Consideration for AI Integration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursor Libraries (e.g., metal salts, organic building blocks) | Foundation for robotic synthesis. Consistent purity is critical for reproducibility. | Must be compatible with liquid handling robots (solubility, viscosity) and barcoded for inventory tracking. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Robots (e.g., Hamilton, Echo) | Enable precise, high-throughput dispensing of reagents for combinatorial experiments. | APIs must allow direct control from experiment design software (e.g., ChemOS, custom Python). |

| Integrated Robotic Glovebox & Annealing Station | Provides inert atmosphere for air-sensitive reactions (e.g., perovskites) and controlled thermal processing. | Robotics must be synchronized; thermal profiles must be logged digitally and linked to each sample ID. |

| High-Throughput Characterization Suite (Inline UV-Vis, Automated XRD, PL Mapper) | Generates the primary data for model feedback. Speed and automation are paramount. | Raw data (spectra, diffractograms) must be output in structured, machine-readable formats (e.g., .json, .h5) with metadata. |

| Computational Chemistry Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian) | Provides DFT validation of AI-predicted candidates before synthesis. | Jobs must be launched and results parsed via scripts to integrate seamlessly into the candidate selection pipeline. |

| Cloud/High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs intensive AI model training, generative sampling, and DFT calculations. | Requires orchestration tools (Kubernetes, SLURM) to manage mixed AI/HPC workloads dynamically. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | The digital backbone. Tracks samples, links synthesis parameters to characterization data, and manages versioning. | Must have a well-documented API for bidirectional data flow between lab hardware, AI models, and databases. |

This technical guide delineates core computational paradigms within the context of a broader thesis on AI-driven materials discovery and drug development. It provides a structured comparison, methodologies, and essential toolkits for researchers.

Core Definitions & Quantitative Comparison

The following table summarizes key quantitative and functional attributes of these technologies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core AI Paradigms

| Term | Primary Objective | Key Architecture/Model | Typical Data Volume | Dominant Application in Materials/Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Learn patterns & make predictions from data. | Random Forest, SVM, Gradient Boosting. | Medium (10³ - 10⁶ samples). | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, property prediction. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Learn hierarchical representations from raw data. | Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Graph Neural Network (GNN). | Large (10⁴ - 10⁹ samples). | Molecular graph property prediction, high-throughput screening image analysis. |

| Generative Models | Create new, plausible data samples. | Variational Autoencoder (VAE), Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), Diffusion Models. | Very Large (10⁵ - 10⁹ samples). | De novo molecular design, synthesis pathway generation, novel material structure proposal. |

| Digital Twins | Create a virtual, dynamic replica of a physical system. | Hybrid: Physics-based models + ML/DL for calibration. | Continuous stream from IoT/sensors. | In-silico prototyping of chemical reactors, patient-specific disease models for preclinical trials. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for a GNN-based Material Property Prediction Experiment

- Objective: Predict the bandgap of a crystalline material from its atomic structure.

- Input Data: CIF (Crystallographic Information File) files.

- Preprocessing: Convert CIF to graph representation: atoms as nodes (featurized by atomic number, valence), bonds as edges (featurized by bond length, type).

- Model Architecture: A 4-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) with skip connections.

- Training: Use a dataset like Materials Project (≈150k structures). Split 80/10/10 (train/validation/test). Optimize with Adam optimizer (learning rate=0.001) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) loss.

- Validation: Perform 5-fold cross-validation. Report MAE and R² scores on the hold-out test set.

Protocol for a Generative VAE-based Molecular Design Experiment

- Objective: Generate novel, drug-like molecules with high affinity for a target protein.

- Input Data: SMILES strings from ChEMBL database, filtered by molecular weight (≤500) and logP.

- Preprocessing: Tokenize SMILES strings. Use one-hot encoding for a fixed-length sequence.

- Model Architecture: A Sequence-based VAE: Encoder (Bidirectional LSTM), Latent Space (512-dim), Decoder (LSTM).

- Training: Train to reconstruct input SMILES. Add a regularization term (Kullback–Leibler divergence) to ensure a smooth latent space.

- Generation & Validation: Sample points from latent space and decode. Filter outputs for validity (RDKit), uniqueness, and novelty. Use a pre-trained predictor (e.g., a Random Forest QSAR model) to score generated molecules for the target property.

Visualizations

AI-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

Generative AI Model Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for AI in Materials & Drug Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Manipulates molecular structures, descriptors, and reactions. | SMILES validation, molecular featurization, fingerprint generation. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Provides flexible architecture for building and training neural networks. | Constructing GNNs, VAEs, and other custom model architectures. |

| Matminer / pymatgen | Materials Informatics Toolkit | Featurizes crystal structures and computes material properties. | Converting CIF files to feature vectors or graphs for ML input. |

| OpenMM / GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Engine | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules for Digital Twins. | Providing physics-based simulation data for model training/validation. |

| Modin / Dask | Scalable Data Processing | Enables handling of large datasets beyond single-machine memory limits. | Processing massive high-throughput screening datasets. |

| Weights & Biases / MLflow | Experiment Tracking | Logs experiments, hyperparameters, and results for reproducibility. | Tracking training runs for the GNN and VAE protocols. |

The field of Materials Informatics (MI), positioned as a cornerstone of the broader AI for materials discovery thesis, has evolved from a niche concept to a transformative discipline. It operationalizes the application of data-driven methods, statistics, and machine learning to materials science challenges, accelerating the design, discovery, and deployment of new materials. This historical perspective charts its evolution within the context of future research directions for AI in materials science.

Historical Phases and Quantitative Milestones

The development of MI can be segmented into distinct, overlapping phases, characterized by key drivers and enabling technologies.

Table 1: Phases in the Evolution of Materials Informatics

| Phase | Approx. Timeline | Core Paradigm | Key Enablers | Representative Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Computational Foundations | 1990s – Early 2000s | High-throughput computation, database creation | Density Functional Theory (DFT), increased computing power, early databases (ICSD, NIST). | First-principles property prediction for limited compound sets. |

| 2. Data-Centric Emergence | Mid-2000s – 2010s | Descriptor-based QSPR/QSAR for materials | Materials Project (2011), AFLOW, OQMD; rise of machine learning libraries (scikit-learn). | Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models for perovskites, thermoelectrics, and metallic glasses. |

| 3. AI-Driven Expansion | 2010s – Present | Deep learning, automated workflows, inverse design | Graph neural networks (GNNs), autoML, robotics (e.g., A-Lab), large language models. | Discovery of novel, stable inorganic crystals and high-performance organic photovoltaics. |

| 4. Autonomous Discovery | Present – Future | Closed-loop, multi-fidelity autonomous systems | Self-driving laboratories, federated learning, multi-modal data integration, generative AI. | Fully autonomous discovery and optimization of functional materials with minimal human intervention. |

Table 2: Quantitative Growth Indicators in Materials Informatics

| Metric | Circa 2010 | Circa 2020 | Current (2024-2025) | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public DFT Datasets | ~10^4 compounds | ~10^6 compounds | > 10^7 calculated materials | Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS |

| ML Publications/Year | Dozens | Hundreds | Thousands | PubMed/arXiv keyword analysis |

| Reported Experimental Validation Speed-up | 2-5x | 5-10x | 10-100x (for targeted systems) | A-Lab (Nature 2024), organic electronic discovery |

| Generative Model Output | N/A | ~10^3 candidate structures | > 10^6 viable candidate structures per run | GNoME, MatterGen |

Experimental Protocols: The Autonomous Discovery Loop

The cutting edge of MI is embodied in self-driving laboratories. The following protocol details the core methodology.

Protocol: Autonomous Closed-Loop Discovery of Inorganic Materials

- Objective: To discover and synthesize novel, stable inorganic materials with target functional properties.

- Workflow: A iterative loop of AI prediction, robotic synthesis, and automated characterization.

- AI Proposal: A generative model (e.g., diffusion model or GNN) proposes candidate compositions and structures. A separate filter model predicts thermodynamic stability (e.g., using formation energy from DFT data).

- Robotic Synthesis: Selected candidates are translated into robotic instructions. A robotic arm prepares precursor powders, performs weighing, mixing (via ball milling or mortar-and-pestle), and loads samples into sealed quartz tubes for solid-state reaction.

- Heat Treatment: Samples are fired in a programmable furnace under controlled atmosphere (e.g., Ar, vacuum).

- Automated Characterization: Robotic arm transfers sintered pellet to:

- X-ray Diffractometer (XRD): For phase identification. Pattern is matched against computed XRD from predicted structure.

- Automated SEM/EDS: For morphological and elemental analysis.

- AI Analysis & Loop Closure: Analysis results are fed back to the AI. A machine learning model classifies synthesis success (e.g., "single phase," "multiphase," "failed"). This data updates the generative and predictive models for the next iteration.

(Title: Autonomous Materials Discovery Closed Loop)

(Title: Core MI Data-Model-Application Pipeline)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Modern Materials Informatics Research

| Category | Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Data | Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes | First-principles calculation of electronic structure and properties. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP |

| Data Resources | Curated Materials Databases | Source of structured, cleaned data for training ML models. | Materials Project, AFLOW, OQMD, JARVIS, NOMAD |

| Descriptor Generation | Structure Featurization Libraries | Convert crystal/molecular structures into numerical descriptors (features). | matminer, DScribe, Roost |

| Core ML Frameworks | Machine Learning Libraries | Provide algorithms for regression, classification, and deep learning. | scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

| MI-Specific ML | Materials-GNN Libraries | Specialized neural networks for direct learning on crystal graphs. | MEGNet, ALIGNN, MatterGen, CHGNet |

| Workflow & Automation | Workflow Management Platforms | Automate computational and data analysis pipelines. | AiiDA, FireWorks, Apache Airflow |

| Experimental Integration | Laboratory Automation Software | Translate digital candidates into robotic synthesis/characterization instructions. | Bluesky, Stingray, Labber |

| Generative Design | Inverse Design Platforms | Generate novel material structures conditioned on target properties. | GNoME, DiffCSP, XenonPy |

The acceleration of materials discovery through artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally constrained by the quality, volume, and interoperability of its underlying data. This whitepaper delineates the three core data-generation pillars—High-Throughput Experiments (HTE), Simulations, and Literature Mining—that fuel modern AI-driven discovery pipelines. The synergistic integration of these heterogeneous data streams is critical for developing robust, predictive models that can navigate the vast combinatorial space of materials and molecular structures, a central thesis in the future of autonomous discovery research.

High-Throughput Experiments (HTE)

HTE employs automated, parallelized platforms to synthesize and characterize thousands of materials or compounds rapidly, generating vast empirical datasets.

2.1. Key Methodologies & Protocols

- Combinatorial Materials Synthesis: Using physical vapor deposition (PVD) masks or inkjet printing to create compositional gradients on a single substrate (e.g., a wafer).

- Protocol: A standard protocol for a thin-film library involves sequential sputtering from multiple targets onto a patterned substrate mounted on a rotating stage. Composition is controlled via masking geometry and deposition time.

- High-Throughput Electrochemical Characterization: For battery or catalyst screening, using multi-channel potentiostats coupled with automated sample handling.

- Protocol: A 96-electrode array plate is loaded with candidate catalyst inks. A robotic arm sequentially engages each electrode with a counter and reference electrode in a common electrolyte, running a standard cyclic voltammetry script (e.g., 50 mV/s sweep rate between 0.05 and 1.2 V vs. RHE) at each channel.

- Automated Synthesis & Screening in Drug Discovery: Utilizing platforms like acoustic droplet ejection to assemble nano-scale reactions in 1536-well plates.

- Protocol: For a biochemical inhibition assay, a protocol involves: 1) Acoustic transfer of 50 nL compound solution into assay plate, 2) Addition of 5 µL enzyme solution via dispenser, 3) Incubation (30 min, 25°C), 4) Addition of 5 µL fluorogenic substrate, 5) Kinetic fluorescence read (Ex/Em 485/530 nm) over 60 minutes.

2.2. The Scientist's Toolkit: HTE Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function in HTE |

|---|---|

| Combinatorial Sputtering Targets (e.g., Li, Co, Ni, Mn oxides) | High-purity sources for vapor-phase deposition of thin-film material libraries. |

| 1536-Well Microplate | Ultra-high-density plate for miniaturized reactions, maximizing throughput and minimizing reagent cost. |

| Fluorogenic/Luminescent Reporter Assay Kits | Provide turn-key biochemical assay components for high-throughput enzymatic or cellular activity screening. |

| Multi-Channel Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Enables simultaneous electrochemical characterization of up to 96 independent samples. |

| Acoustic Liquid Handler | Enables precise, contact-less transfer of picoliter-to-nanoliter volumes of reagents or compounds. |

2.3. Quantitative Data from Recent HTE Campaigns Table 1: Output Metrics from Representative High-Throughput Experimental Platforms

| Platform Type | Materials/Compounds per Cycle | Key Characterization Metric | Throughput (Data Points/Day) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin-Film Photovoltaic Library | 1,536 unique compositions | Photovoltaic Efficiency (%) | ~1,536 | 2023 |

| Heterogeneous Catalyst Screening | 768 catalyst formulations | Turnover Frequency (h⁻¹) | ~768 | 2024 |

| Organic LED Emitter Screening | 5,000+ molecules | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield | ~10,000 | 2023 |

| Biochemical Inhibition Assay | >100,000 compounds | IC₅₀ (nM) | >300,000 | 2024 |

Figure 1: Closed-loop HTE workflow for AI-driven materials discovery.

Simulations (Computational Data Generation)

First-principles and molecular simulations provide atomic-level understanding and generate precise physical property data at scale, crucial for training AI models where experimental data is scarce.

3.1. Key Methodologies & Protocols

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculation of Material Properties:

- Protocol: 1) Obtain crystal structure (e.g., from ICSD). 2) Geometry optimization using VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO with PBE functional and PAW pseudopotentials until forces < 0.01 eV/Å. 3) Static self-consistent field calculation. 4) Property calculation (e.g., band structure via K-path, density of states, elastic tensor). 5) Post-processing for target properties (e.g., band gap, bulk modulus).

- Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) for Protein-Ligand Binding:

- Protocol: 1) Prepare protein-ligand complex topology using CHARMM36/AMBER ff14SB force field. 2) Solvate in TIP3P water box with 10 Å padding. 3) Neutralize with ions. 4) Energy minimization (5,000 steps). 5) NVT and NPT equilibration (300 K, 1 bar, 100 ps each). 6) Production run (100 ns) on GPU-accelerated platform (e.g., OpenMM, GROMACS). 7) Trajectory analysis for RMSD, binding free energy (MM/PBSA).

3.2. Quantitative Data from Simulation Campaigns Table 2: Scale and Scope of Recent Computational Data Generation Efforts

| Project/DB Name | Simulation Method | # of Data Entries | Key Properties Calculated | Reference/Update |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | DFT (VASP) | >150,000 materials | Formation energy, Band gap, Elasticity, DOS | 2024 (Ongoing) |

| Open Catalyst Project | DFT (VASP) | >1.5M adsorbate-surface relaxations | Adsorption energies, Structures | 2023 |

| QM9 | DFT (G4MP2-like) | 134k small organic molecules | Electronic, Thermodynamic, Energetic properties | 2014 (Benchmark) |

| AlphaFold DB | Deep Learning (AlphaFold2) | >200M protein structures | 3D coordinates, per-residue pLDDT confidence | 2024 |

Figure 2: Computational data generation pipeline for AI training.

Literature Mining (Unstructured Data Extraction)

Scientific literature represents a vast, unstructured repository of experimental observations. Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques convert this text into structured, machine-actionable knowledge.

4.1. Key Methodologies & Protocols

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) for Materials Science:

- Protocol: 1) Corpus collection (PDF parsing of relevant journals). 2) Annotation of entity spans (e.g., material names, properties, synthesis conditions) using BRAT or LabelStudio. 3) Training a transformer-based model (e.g., SciBERT, MatBERT) on the annotated corpus. 4) Inference on new text to extract entities. 5) Linking extracted entities to canonical identifiers (e.g., via Materials API).

- Relationship Extraction for Drug-Disease Associations:

- Protocol: 1) Sentence segmentation from PubMed abstracts. 2) Dependency parsing using spaCy. 3) Application of a pre-trained relation extraction model (e.g., BioBERT fine-tuned on the ChemProt dataset) to identify "inhibits," "treats," or "binds" relationships between chemical and disease entities. 4) Populating a knowledge graph with subject-relation-object triples.

4.2. Quantitative Data from Literature Mining Table 3: Scale of Extracted Knowledge from Scientific Literature via NLP

| Source / Tool | Domain | # of Extracted Entities/Relations | Key Entity Types | Update |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBM Watson for Drug Discovery | Biomedicine | Millions of relationships | Genes, Diseases, Drugs, Adverse Events | 2023 |

| PolymerNLP | Polymer Science | ~80k polymerization records | Monomers, Initiators, Conditions, Properties | 2024 |

| ChemDataExtractor 2.0 | Chemistry | Curated from millions of docs | Materials, Properties, Spectra | 2023 |

| LitMined KGs (e.g., SPD) | General Science | Billions of triples | Materials, Methods, Applications | Ongoing |

4.3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Literature Mining Resources

| Item | Function in Literature Mining |

|---|---|

| SciBERT / MatBERT / BioBERT Pre-trained Models | Domain-specific language models providing foundational understanding of scientific text. |

| ChemDataExtractor Toolkit | Rule-based and ML-powered system for parsing chemistry-specific text, tables, and figures. |

| BRAT Annotation Tool | Web-based environment for collaborative annotation of text documents for NER/RE tasks. |

| PolymerGNN Pipeline | End-to-end system for extracting polymer property data and training graph neural networks. |

Figure 3: Literature mining to knowledge graph pipeline.

Integration for AI-Driven Discovery

The frontier of AI for materials discovery lies in the multimodal fusion of these data sources. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can operate on unified graph representations combining crystal structures (simulations), property vectors (experiments), and textual knowledge (literature). Transformer models can be jointly trained on sequence data (SMILES, protein sequences) and associated tabular data from HTE and simulations. This integration creates a more complete, causally informed digital twin of the materials discovery process, enabling robust predictions of novel, high-performing materials and therapeutics with unprecedented speed.

Within the broader thesis of accelerating the discovery-to-deployment cycle, Artificial Intelligence has evolved from a supplementary tool to a core driver of innovation in materials science. By integrating high-throughput computation, automated synthesis, and robotic testing, AI systems are identifying novel materials with unprecedented speed, addressing critical needs in energy storage, catalysis, and quantum computing.

Foundational Methodologies & Experimental Protocols

The AI-driven discovery pipeline follows a structured, iterative workflow.

The Closed-Loop Autonomous Discovery System

This protocol represents the state-of-the-art experimental framework.

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Robotic Laboratory for Inorganic Materials

- Problem Definition & Seed Data: Define target properties (e.g., band gap, formation energy). Assemble initial dataset from repositories like the Materials Project (MP) or the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD).

- AI Model Training: Train a graph neural network (GNN) or crystal graph convolutional neural network (CGCNN) on formation energy and property predictions. A Bayesian optimizer (e.g., TuRBO) is often used for active learning.

- Candidate Proposal: The AI model proposes promising chemical compositions and structures from a vast search space (e.g., ternary and quaternary spaces).

- Robotic Synthesis: Proposed recipes are executed by an automated liquid-handling or solid-dispensing robot. Common methods include solid-state reaction or powder processing in controlled atmosphere furnaces.

- Automated Characterization: Robotic systems transfer samples to characterization tools: PXRD (Phase Identification), SEM/EDS (Morphology & Composition), and automated resistivity measurements.

- Data Feedback & Model Refinement: Characterization results are parsed automatically, labeling success/failure and measured properties. This data is fed back into the AI model, closing the loop.

Protocol for Stable Novel Organic Molecular Discovery

Protocol: Generative AI for Organic Electronic Materials

- Generative Model Design: A variational autoencoder (VAE) or a generative adversarial network (GAN) is trained on SMILES strings from databases like PubChem.

- Conditional Generation: The generator is conditioned on target properties (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap, photovoltaic efficiency) predicted by a separate property predictor network.

- In-silico Screening: Generated candidates are filtered via DFT calculations (e.g., using Gaussian or ORCA) for stability and property validation.

- Synthesis Planning: A retrosynthesis AI (e.g., based on template-free models) proposes viable synthesis routes.

- Experimental Validation: Top candidates are synthesized and characterized via HPLC, NMR, and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

The following table summarizes key breakthroughs validated experimentally.

Table 1: Landmark AI-Discovered Functional Materials (2020-Present)

| Material System (Composition) | Discovery Platform/AI Model | Key Predicted & Validated Property | Potential Application | Reference/Project |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li-ion Solid Electrolyte (Li₆PS₅Cl variant) | Bayesian Optimization coupled with GNN | High ionic conductivity (>1 mS/cm) and stability | Solid-state batteries | A-Lab (UC Berkeley/Google) |

| Novel Ternary Oxide (Gd₆Mg₂O₅) | Deep Learning (CGCNN) on OQMD data | Thermodynamic stability (>90% confidence) | Catalysis, Phosphors | Autonomous Discovery (Toyota Research) |

| MOF for Carbon Capture (Not specified) | Genetic Algorithm + Molecular Simulation | High CO₂ adsorption capacity at low pressure | Carbon Capture | (Multiple groups) |

| Organic Photovoltaic Molecule (DSDP-K) | Generative Model (VAE) + DFT | High power conversion efficiency (PCE >12%) | Organic Solar Cells | (Univ. of Florida) |

| High-Entropy Alloy (Al-Ni-Co-Fe-Cr) | Random Forest + CALPHAD | Superior strength-ductility trade-off | Structural Materials | Citrination platforms |

Visualizing the Discovery Workflow

Diagram 1: Autonomous Materials Discovery Loop

Diagram 2: Generative Molecular Design Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents & Materials for AI-Driven Discovery Experiments

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Critical Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Inks/Powders | Raw materials for robotic solid-state synthesis. | High purity (>99.9%), controlled particle size for consistent dispensing. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Enables precise, repeatable mixing of solutions for MOF/polymer synthesis. | Must integrate with lab scheduling software (e.g., Kolabware). |

| Sealed Reaction Vessels | For solid-state reactions under inert/controlled atmosphere. | Compatible with robotic grippers and transfer arms. |

| Standardized XRD/SEM Sample Holders | Allows robotic plate-to-tool transfer for characterization. | Uniform geometry (e.g., 96-well plate format) is essential. |

| Structured Data Parsing Software | Converts raw characterization data (XRD peaks, spectra) into labeled training data. | Uses ML models for phase identification from PXRD patterns. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs DFT calculations for validation and ML model training. | GPU acceleration (NVIDIA A/V100) is critical for GNNs. |

The Critical Role of High-Quality, Curated Materials Datasets (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD)

Within the broader thesis of AI for materials discovery, high-quality, curated datasets are not merely convenient repositories but the foundational substrate upon which predictive models are built and validated. The acceleration of materials discovery, from next-generation battery electrodes to novel catalysts, is critically dependent on the scope, fidelity, and accessibility of these databases. This whitepaper details the core technical aspects of major materials databases, their role in the AI/ML pipeline, and provides protocols for their effective utilization in computational and experimental research.

Core Datasets: Architecture and Quantitative Comparison

Curated materials databases provide calculated and, increasingly, experimental properties for hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for leading platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Curated Materials Datasets (as of 2024)

| Database | Primary Institution | Total Entries | Primary Data Type | Key Properties Calculated | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) | LBNL, MIT | ~150,000 materials | DFT (VASP) | Formation energy, Band structure, Elastic tensor, Piezoelectric tensor, Phonon dispersion | REST API, Web Interface |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Northwestern University | ~1,000,000+ entries | DFT (mostly VASP) | Formation energy, Stability (energy above hull), Electronic energy levels | Web Interface, Database Download |

| AFLOW | Duke University, et al. | ~4,000,000 entries | DFT (VASP, others) | Enthalpy, Band gap, Elastic constants, Thermodynamic properties | REST API (AFLOW), Libs |

| NOMAD | European Consortium | ~200,000,000 calculations (raw & curated) | Diverse ab initio results | Meta-data from most major DFT codes, curated "encyclopedia" subsets | Web Interface, API, Oasis |

| JARVIS-DFT | NIST | ~70,000 materials | DFT (VASP, OptB88vdW) | Formation energy, Band gap, Elastic, piezoelectric, topological, exfoliation energies | Web Interface, API, GitHub |

Table 2: Typical DFT Calculation Parameters Underlying These Datasets

| Parameter | Common Setting in Databases | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | PBE (GGA) | Good balance of accuracy & computational cost for structural properties. |

| Precision | Standard (MP, OQMD) or High (AFLOW) | Convergence in energy, force, and stress. |

| k-point Density | ≥ 50 / Å⁻³ | Sufficient for Brillouin zone integration. |

| Cutoff Energy | 1.3-1.5 x highest ENMAX in POTCAR | Ensures plane-wave basis set convergence. |

| Pseudopotentials | Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) | Standard for accuracy and efficiency. |

Integrating Datasets into the AI for Materials Discovery Workflow

The role of these datasets extends far beyond simple lookup. They are integral to the closed-loop AI-driven discovery pipeline.

Diagram 1: The AI-Driven Materials Discovery Loop

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Using the Materials Project API for High-Throughput Data Retrieval

Objective: Programmatically retrieve crystal structure and thermodynamic data for a list of material identifiers. Methodology:

- Setup: Install the

pymatgenandrequestslibraries in a Python environment. - Authentication: Obtain an API key from the Materials Project website.

- Query Construction: Use the

MPResterclass frompymatgento interface with the API. - Data Retrieval: For a given material ID (e.g., "mp-1234"), query properties such as structure, formation energy, band gap, and elastic tensor.

- Data Parsing: Parse the returned JSON data into pandas DataFrames for analysis. Example Code Snippet:

Protocol 4.2: Stability Analysis Using the Phase Diagram (Energy Above Hull)

Objective: Determine the thermodynamic stability of a compound relative to competing phases. Methodology:

- Data Source: Query the OQMD or MP for the formation energy of the target compound and all other compounds in its chemical space.

- Phase Diagram Construction: Use the

PhaseDiagramclass inpymatgento construct the convex hull from the formation energies of all relevant phases. - Stability Calculation: Compute the "energy above hull" (Eabovehull) for the target compound. This is the energy difference between the compound and the convex hull at its composition.

- Interpretation: An Eabovehull ≤ 0 meV/atom indicates the compound is thermodynamically stable. Values > 0 indicate metastability (tolerance depends on application, often < 50 meV/atom for synthesis).

Key Formula:

E_above_hull = E_form(compound) - E_form(hull)

Diagram 2: Computational Stability Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Item (Software/Service) | Function/Benefit | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pymatgen | Python library for materials analysis. Core tool for parsing, analyzing, and manipulating crystal structures and computational data. | Converting between file formats, analyzing diffusion pathways, calculating order parameters, interfacing with databases. |

| Atomate | Workflow management library for computational materials science. Automates sequences of DFT calculations. | Setting up high-throughput property calculation pipelines (elastic tensors, band structures). |

| matminer | Library for creating machine-readable features (descriptors) from materials data. | Generating composition and structure-based features (e.g., Magpie, SiteStatsFixtures) for ML model training. |

| MPContribs (Materials Project) | Platform for sharing community-contributed datasets and analysis. | Accessing specialized datasets (e.g., experimental yield strength, battery cycling data) linked to core MP entries. |

| JARVIS-Tools | Software suite accompanying JARVIS databases for analysis and ML. | Applying pre-trained ML models for property prediction or performing classical force-field simulations. |

| AFLOW API | RESTful API for the AFLOW database. Enables complex combinatorial queries (chull, prototypes, properties). | Searching for all stable ternary compounds with a specific crystal prototype and a band gap > 1 eV. |

Cutting-Edge AI Methods and Their Real-World Applications in Materials R&D

Within the broader thesis on the future of AI for materials discovery, generative artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift from screening to creation. Inverse design, powered by generative models, directly optimizes for target properties, enabling the de novo generation of molecules and crystals with specified characteristics. This technical guide explores the core architectures, methodologies, and experimental protocols underpinning this transformative approach.

Core Generative Architectures

Molecular Generation

Generative models for molecules must handle discrete, graph-structured data and enforce chemical validity.

- VAEs (Variational Autoencoders): Encode molecular representations (e.g., SMILES, graphs) into a continuous latent space where interpolation and sampling occur. Decoders reconstruct valid structures.

- GNN-based GANs (Graph Neural Network-Generative Adversarial Networks): A generator creates molecular graphs, while a discriminator distinguishes generated from real molecules. Reinforcement learning (RL) is often added to fine-tune for properties.

- Flow-based Models: Learn invertible transformations between complex molecular data distributions and simple base distributions (e.g., Gaussian), enabling exact likelihood computation.

Crystal Structure Generation

Crystal generation requires modeling periodicity, symmetry (space groups), and composition.

- Diffusion Models: The state-of-the-art for crystal generation. These models gradually add noise to crystal structures during training and learn to reverse this process to generate novel, valid structures from noise.

- Conditional Generative Models: All architectures can be conditioned on target properties (e.g., formation energy, band gap, porosity) to steer the generation process.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Key Generative Models (2023-2024)

| Model Architecture | Primary Application | Key Metric | Reported Value | Benchmark Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-SchNet (VAE) | Molecule Generation | Validity (% valid structures) | 99.9% | QM9 |

| MoFlow (Flow) | Molecule Generation | Novelty (% unseen in training) | 94.2% | ZINC250k |

| CDVAE (Diffusion) | Crystal Generation | Property Optimization Success Rate | 82.5% | Perov-5 |

| MatFEGAN (GAN) | Crystal Generation | Structural Stability (% stable) | 76.1% | ICSD |

| CRYSTAL-GFN (RL) | Molecule & Crystal | Hit Rate (for target band gap) | 34.7% | MP-20 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Diffusion Model for Crystal Generation

The following protocol details a state-of-the-art approach for generating novel, stable crystal structures conditioned on a target chemical formula.

Protocol Title: Conditional Crystal Diffusion VAE (CDVAE) for de novo Crystal Structure Generation

Objective: To generate novel, thermodynamically stable crystal structures given a target composition (e.g., CaTiO₃).

Required Tools & Libraries:

- Python 3.9+

- PyTorch 1.12+

- PyTorch Geometric

- pymatgen

- ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment)

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Preprocessing (from Materials Project):

- Source: Query the Materials Project API for all experimentally reported structures for the broad chemical family (e.g., all perovskites).

- Standardization: Use

pymatgento standardize all crystal structures to a conventional cell setting. - Representation: Convert each crystal to a tuple representation:

(lattice matrix, fractional coordinates, atom types, composition). - Property Labeling: Annotate each entry with calculated properties (formation energy, band gap from DFT).

Model Training (Conditional Diffusion VAE):

- Encoder: A Graph Neural Network (GNN) encodes the crystal graph (atoms as nodes, edges based on proximity) into a latent vector

z. - Diffusion Process:

- Forward Process: Over

T=1000steps, progressively add Gaussian noise to the encoded latent vectorz. The noise schedule is defined by variance scheduleβ_t. - Reverse Process: Train a denoising network (a time-conditioned U-Net) to predict the added noise at each step

t. Condition this network on a learned embedding of the target composition.

- Forward Process: Over

- Decoder: A multi-layer perceptron predicts lattice parameters and atomic coordinates from a denoised latent vector.

- Loss Function: A weighted sum of:

- Reconstruction Loss: MSE between original and decoded lattice/coordinates.

- KL Divergence: Between the encoder's output distribution and a standard normal prior.

- Denoising Loss: MSE between true and predicted noise in the latent diffusion process.

- Encoder: A Graph Neural Network (GNN) encodes the crystal graph (atoms as nodes, edges based on proximity) into a latent vector

Conditional Generation & Sampling:

- Conditioning: Feed the target composition (e.g.,

"CaTiO3") into the model's conditioner to obtain a condition vectorc. - Sampling: Start from pure Gaussian noise

z_T. FortfromTto 1:- Input noisy

z_t, conditionc, and timesteptinto the trained denoiser. - Predict the noise component.

- Use the diffusion sampler (DDPM or DDIM) to compute a slightly denoised

z_{t-1}.

- Input noisy

- Decoding: Pass the final denoised latent vector

z_0through the decoder to obtain a candidate crystal structure.

- Conditioning: Feed the target composition (e.g.,

Validation & Filtering (Post-Processing):

- Validity Check: Ensure the generated structure has sensible interatomic distances (no atomic clashes) using

pymatgen's structure analyzer. - Stability Screening: Perform a rapid, approximate energy evaluation using a pre-trained machine learning force field (e.g., M3GNet) or a cheap DFT preset (e.g., VASP with PBEsol) to filter out high-energy, unstable candidates.

- Uniqueness Check: Compare the generated structure's fingerprint (e.g., XRD pattern or radial distribution function) to known structures in the training database to assess novelty.

- Validity Check: Ensure the generated structure has sensible interatomic distances (no atomic clashes) using

Diagram Title: Conditional Diffusion Model Workflow for Crystal Generation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Generative AI Experiments

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Generative AI in Inverse Design

| Item / Solution | Function / Role | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Materials Datasets | Provides the foundational data for training and validating generative models. Curated, large-scale datasets are critical. | Materials Project (MP), Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), OMDB, QM9, PubChemQC. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Library | Enables modeling of molecules and crystals as graphs (atoms=nodes, bonds=edges), crucial for capturing local atomic environments. | PyTorch Geometric (PyG), Deep Graph Library (DGL). |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | The computational "ground truth" for calculating material properties (energy, band gap) used to label training data and validate generated candidates. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP. |

| Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) | Accelerates stability screening of generated structures by providing energy/force predictions orders of magnitude faster than DFT. | M3GNet, CHGNet, NequIP. |

| Automated Structure Analysis Package | Performs validation, standardization, and feature extraction (e.g., symmetry, fingerprints) on generated molecular/crystal structures. | pymatgen, ASE, RDKit. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) / Cloud GPU | Provides the computational power necessary for training large generative models (diffusion, transformers) on complex chemical data. | NVIDIA A100/H100 GPUs, Google Cloud TPUs, AWS ParallelCluster. |

| Inverse Design Platform (Integrated) | End-to-end software platforms that combine generation, simulation, and optimization loops. | MatterGen (Meta AI), GNoME (Google DeepMind), ATOM3D. |

Future Directions and Integration into the AI-Driven Discovery Thesis

The trajectory of generative AI for inverse design points towards several critical research vectors that align with the overarching thesis of autonomous materials discovery:

- Multiscale & Multi-fidelity Generation: Moving beyond atomic structure to generate mesostructures and device geometries, while intelligently blending low- and high-fidelity data.

- Closed-Loop Autonomous Laboratories: Tight integration of generative models with robotic synthesis and characterization platforms, where AI-generated designs are automatically synthesized, tested, and the results fed back to improve the model.

- Foundational Models for Materials Science: Developing large-scale, pretrained models on vast, diverse datasets that can be fine-tuned for specific inverse design tasks with limited data, akin to GPT or AlphaFold for materials.

- Explicit Incorporation of Synthesis Constraints: Conditioning generation not only on target properties but also on feasible synthesis pathways (precursors, temperatures, pressures), bridging the gap between design and manufacturability.

The convergence of these directions will transition generative AI from a tool for in silico design to the core engine of a fully integrated, self-driving discovery pipeline.

Within the paradigm of AI for accelerated materials discovery, the precise modeling of atomic systems represents a fundamental challenge. Traditional quantum mechanical methods, while accurate, are computationally prohibitive for screening vast chemical spaces. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a transformative architecture, leveraging the inherent graph structure of molecules and crystals—where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges—to learn complex, high-dimensional interatomic potentials and relationships with quantum-accuracy at a fraction of the cost. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of GNNs in modeling atomic interactions, positioning them as a cornerstone for the next generation of materials informatics.

Theoretical Foundations: GNNs for Atomic Systems

A molecule or crystal is naturally represented as an undirected or directed graph ( G = (V, E) ), where ( V ) is the set of atomic nodes and ( E ) is the set of bonding/interaction edges. Each node ( i ) is attributed with a feature vector ( \mathbf{x}i ) (e.g., atomic number, formal charge, hybridization state). Each edge ( (i,j) ) can have features ( \mathbf{e}{ij} ) (e.g., bond type, distance).

The core operation of a GNN is message passing. In layer ( l ), for each node ( i ), the network:

- Aggregates messages from its neighboring nodes ( j \in \mathcal{N}(i) ): [ \mathbf{m}i^{(l)} = \text{AGGREGATE}^{(l)}({ \mathbf{h}j^{(l-1)}, \mathbf{e}_{ij} : j \in \mathcal{N}(i) }) ]

- Updates the node's hidden state by combining the aggregated message with its previous state: [ \mathbf{h}i^{(l)} = \text{UPDATE}^{(l)}(\mathbf{h}i^{(l-1)}, \mathbf{m}i^{(l)}) ] where ( \mathbf{h}i^{(0)} = \mathbf{x}_i ).

After ( L ) message-passing layers, a readout function pools the final node representations ( \mathbf{h}_i^{(L)} ) to produce a graph-level prediction (e.g., total energy, bandgap).

Diagram: The Message-Passing Paradigm in an Atomic Graph

Quantitative Performance of State-of-the-Art GNN Models

Recent benchmarking on standardized quantum chemistry datasets demonstrates the performance of leading GNN architectures. Key metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energy predictions and inference speed relative to Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNN Models on Molecular Property Prediction (QM9 Dataset)

| Model Architecture | MAE for Internal Energy (U0) [meV] | MAE for HOMO [meV] | Relative Inference Speed (vs. DFT) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SchNet | 14 | 27 | ~10^5 | Continuous-filter convolutional layers using radial basis functions. |

| DimeNet++ | 6.3 | 19.5 | ~10^4 | Directional message passing with spherical Bessel functions. |

| SphereNet | 5.9 | 18.2 | ~10^4 | E(3)-equivariant model using spherical harmonics for angular encoding. |

| PaiNN | 5.7 | 16.5 | ~10^4 | Equivariant message passing with vectorial features (scalar+vector streams). |

| GemNet | 5.4 | 15.2 | ~10^3 | Incorporates both directional and geometric information (angles, dihedrals). |

Table 2: GNN Performance on Solid-State Materials (OCP Datasets, MP-2020)

| Model / Target | MAE (Formation Energy) [meV/atom] | MAE (Band Gap) [eV] | MAE (Elasticity) [GPa] | Training Set Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGCNN | 28 | 0.39 | 0.41 | ~60k crystals |

| MEGNet | 23 | 0.33 | 0.37 | ~60k crystals |

| ALIGNN | 19 | 0.28 | 0.32 | ~60k crystals |

| GNoME (GNN) | < 15* | 0.25* | N/A | > 1 million* |

*Reported from latest pre-prints on large-scale discovery initiatives. ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network) incorporates bond angles via line graphs.

Experimental Protocols for GNN Training & Validation in Materials Discovery

A robust experimental pipeline is critical for developing reliable models.

Protocol 4.1: Building a Robust GNN Training Pipeline

- Data Curation: Assemble a dataset from quantum mechanics databases (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD, QM9). Features include atomic number, coordinates, lattice vectors, and target properties (energy, forces).

- Graph Representation: Convert each structure to a graph. Define a cutoff radius (e.g., 5-8 Å) for edges. Node/edge features are one-hot encoded or embedded.

- Splitting: Use structure-agnostic splitting (e.g., by composition hash, scaffold split for molecules) to prevent data leakage, ensuring no similar structures are in both train and test sets.

- Model Training: Use a rotationally invariant or equivariant architecture. Employ a loss function combining energy and force errors: ( \mathcal{L} = \lambdaE || \hat{E} - E ||^2 + \lambdaF \sumi || \hat{\mathbf{F}}i - \mathbf{F}_i ||^2 ). Train with the Adam optimizer.

- Validation: Monitor MAE on a held-out validation set. Use external test sets from different sources for final evaluation.

Protocol 4.2: Active Learning Loop for Directed Exploration

- Initial Model: Train a GNN on a known, diverse seed dataset.

- Candidate Generation: Use heuristic rules (e.g., substitution, structure search) or generative models to propose new candidate structures.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use the trained GNN ensemble (multiple models) to predict properties and their standard deviation (uncertainty) for each candidate.

- Acquisition: Select candidates with high predicted performance and high uncertainty (Pareto-optimal or using Upper Confidence Bound).

- DFT Verification: Perform first-principles calculation on the acquired candidates.

- Iteration: Add the newly verified data to the training set and retrain the model. Repeat from step 2.

Diagram: Active Learning Workflow for GNN-Driven Discovery

Table 3: Key Software & Computational Resources for GNN-Based Materials Research

| Item / Resource | Function & Purpose | Example / Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network Libraries | Provides modular, high-performance building blocks for developing custom GNN architectures. | PyTorch Geometric (PyG), Deep Graph Library (DGL), Jraph (JAX). |

| Interatomic Potentials/Force Fields | Pre-trained GNN models that serve as fast, accurate replacements for ab initio MD. | MACE, CHGNet, NequIP. Available on platforms like Open Catalyst Model Zoo. |

| Materials Databases | Source of ground-truth quantum mechanical data for training and benchmarking models. | Materials Project (MP), Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), JCrystalDB. |

| Automated Workflow Managers | Orchestrates high-throughput DFT calculations for generating training data and validation. | Atomate, AFLOW, FireWorks. |

| Structure Generation Tools | Generates candidate crystal or molecular structures for virtual screening. | PyXtal, AIRSS, GNoME's graph-based generator. |

| Active Learning Frameworks | Manages the iterative cycle of prediction, acquisition, and retraining. | AMPTOR, ChemOS, custom scripts leveraging Bayesian optimization libraries. |

Future Directions & Integration into the AI for Materials Discovery Thesis

The trajectory of GNNs points towards increasingly universal and foundational models. The future lies in training on multi-million-scale datasets spanning diverse elements and structures to create a single, general-purpose interatomic potential. Key challenges remain in improving extrapolation to unseen chemistries, modeling long-range interactions and electron densities, and seamlessly integrating with downstream robotic synthesis and characterization pipelines. As a core component of the AI for materials discovery thesis, GNNs evolve from specialized predictors to the central, unifying ab initio engine for a closed-loop, autonomous discovery system, dramatically accelerating the design cycle for advanced batteries, catalysts, polymers, and pharmaceuticals.

Within the broader thesis on future directions for AI in materials discovery, a fundamental challenge persists: the prohibitive cost and time of experiments and high-fidelity simulations. Active Learning (AL) and Bayesian Optimization (BO) have emerged as a powerful synergistic framework to overcome this bottleneck. This guide details their technical integration for intelligently guiding discovery pipelines, enabling researchers to converge on optimal materials or molecular candidates with minimal, maximally informative evaluations.

Foundational Concepts

Active Learning (AL) Cycle

AL is a supervised machine learning paradigm where the algorithm selects the most informative data points from a pool of unlabeled data to be labeled (i.e., experimentally/simulatively evaluated). The core cycle is: Train -> Query -> Label -> Update.

Bayesian Optimization (BO)

BO is a sequential design strategy for optimizing black-box, expensive-to-evaluate functions. It employs a probabilistic surrogate model (typically Gaussian Processes) to approximate the objective function and an acquisition function to decide the next point to evaluate by balancing exploration and exploitation.

Integrated AL/BO Workflow for Experimental Guidance

The integration of AL for model training and BO for objective optimization creates a robust closed-loop system.

Diagram 1: Closed-loop Bayesian Optimization Workflow (78 chars)

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: High-Throughput Virtual Screening with AL/BO

Objective: Identify organic photovoltaic molecules with a power conversion efficiency (PCE) > 12%.

- Initialization: Create a seed dataset of 50 molecules with known PCE from literature. Encode molecules as numerical descriptors (e.g., Mordred fingerprints, SOAP).

- Surrogate Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model using a Matérn kernel, mapping molecular descriptors to PCE.

- Acquisition: Calculate Expected Improvement (EI) across a pre-enumerated library of 100,000 candidate molecules.

- Selection & Evaluation: Select the top 5 molecules with highest EI. Evaluate their PCE using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) simulation.

- Update & Iterate: Add the new (descriptor, PCE) pairs to the training set. Retrain the GP model. Repeat steps 3-5 for 20 iterations (100 total evaluations).

- Validation: Synthesize and experimentally test the top 3 recommended molecules from the final model.

Protocol: Autonomous Optimization of Synthesis Parameters

Objective: Maximize the yield of a perovskite quantum dot synthesis reaction.

- Design Space: Define parameters: precursor concentration (0.1-1.0 M), reaction temperature (150-250 °C), injection rate (1-10 mL/min).

- Initial Design: Perform a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) of 10 initial experiments.

- Autonomous Loop: Implement the workflow from Diagram 1. The "Experiment" is an automated robotic synthesis platform coupled with inline UV-Vis spectroscopy for yield quantification.

- Surrogate Model: Use a GP with automatic relevance determination (ARD) to identify the most critical parameter.

- Stopping Rule: Terminate after 50 total experiments or if the predicted optimum yield stabilizes within 2% over 5 consecutive iterations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms on Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Avg. Evaluations to Optimum (Sphere) | Avg. Regret (Branin) | Success Rate (%) (Complex Composite) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | 500 ± 25 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 65 |

| Random Search | 320 ± 45 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 78 |

| Bayesian Optimization | 85 ± 12 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 98 |

Table 2: Recent Applications in Materials/Drug Discovery

| Field | Target Property | Search Space Size | AL/BO Evaluations | Random Search Evaluations (Equivalent Result) | Citation Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Dielectrics | Energy Density | ~10,000 candidates | 120 | >2,000 | 2023 |

| HER Catalyst | Overpotential | 3D Continuous | 65 | 240 | 2024 |

| Antibacterial Peptides | MIC | 10^5 sequences | 200 | 1,500 | 2023 |

| MOFs | CO2 Capacity | ~5,000 structures | 80 | 700 | 2022 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Guided Discovery

| Item/Reagent | Function in AL/BO Pipeline | Example Product/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Library | Core surrogate model for uncertainty quantification. | GPyTorch, scikit-learn, GPflow |

| Acquisition Function Module | Decides the next experiment. | BoTorch, Ax Platform, Dragonfly |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Encodes materials/molecules for the model. | RDKit (Mordred), DScribe (SOAP), Matminer |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robot | Executes selected experiments autonomously. | Chemspeed, Biosero, Opentrons |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Tracks experimental data, metadata, and results. | Benchling, Labguru, SampleManager |

| Automated Simulation Scripting | Runs computational evaluations (DFT, MD) for selected candidates. | ASE, PyMol, Schrodinger Maestro |

| Open-Source Discovery Platforms | Integrated frameworks for running closed loops. | ChemOS, Summit, Olympus |

Diagram 2: Autonomous Discovery Lab Information Flow (92 chars)

Advanced Considerations & Future Directions

The future of AI for materials discovery, as posited in the overarching thesis, will rely on advanced AL/BO formulations. Key directions include:

- Multi-Fidelity & Multi-Objective BO: Balancing cheap, low-fidelity simulations with expensive, high-fidelity experiments while optimizing for multiple, often competing, properties.

- Deep Kernel Learning: Integrating neural networks into GP kernels to learn rich, problem-specific representations directly from raw data (e.g., spectral graphs, microscopy images).

- Incorporation of Physical Laws: Using physics-informed kernels or constraints to ensure recommendations are physically plausible, improving data efficiency.

- Transfer & Meta-Learning: Leveraging knowledge from prior experimental campaigns on related systems to accelerate new searches, a cornerstone for building cumulative discovery engines.

The integration of Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization provides a mathematically rigorous and empirically proven framework for directing experimental and computational resources. By embedding this approach into self-driving laboratories, the materials and molecular discovery pipeline is poised for a paradigm shift towards unprecedented efficiency and acceleration.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represent a paradigm shift in scientific machine learning, enabling the seamless integration of physical laws (often expressed as partial differential equations, PDEs) into neural network training. This approach is particularly transformative for AI-driven materials discovery, where experimental data is often scarce, expensive to generate, or exists across disparate scales. PINNs address this by constraining the model's solution space with known physics, leading to more generalizable, interpretable, and data-efficient predictions—critical for accelerating the design of novel catalysts, polymers, batteries, and pharmaceuticals.

Core Architecture and Methodology

A PINN is a composite function u_θ(x, t) approximating the solution to a system of PDEs. The key innovation is the design of a composite loss function that penalizes deviations from both observed data and the underlying physics.

Core Loss Function:

L(θ) = L_data(θ) + λ * L_PDE(θ)

where:

L_data(θ) = 1/N_d Σ|u_θ(x_i, t_i) - u_i|²(Supervised loss on measured data).L_PDE(θ) = 1/N_f Σ|f(u_θ, ∂u_θ/∂x, ∂u_θ/∂t, ...; k)|²(Physics loss, wheref=0is the PDE residual).λis a weighting hyperparameter.

Automatic differentiation is used to compute exact derivatives of u_θ with respect to inputs (x, t) for the L_PDE term.

Diagram: PINN Architecture and Workflow

Key Experimental Protocols & Applications

Protocol: Solving Forward PDE Problems for Material Properties

Objective: Predict stress distribution in a composite material without full-field experimental data, using only governing equations and boundary conditions.

- Define Physics: Specify the governing PDE (e.g., linear elasticity: ∇·σ + f = 0) and constitutive law.

- Generate Computational Points: Sample

N_fcollocation points within the domain andN_bpoints on boundaries using Latin Hypercube Sampling. - Build PINN: Implement a fully connected network (e.g., 5 layers, 50 neurons, tanh activation).

- Define Loss:

L = 1/N_b Σ||u_θ - u_b||² + 1/N_f Σ||∇·σ(u_θ) + f||². - Train: Use Adam optimizer (LR=1e-3) for 50k iterations, then L-BFGS for fine-tuning.

- Validate: Compare PINN solution at sparse holdout points against high-fidelity FEM simulation.

Protocol: Inverse Problem for Parameter Identification in Drug Release

Objective: Infer unknown diffusion coefficient D in a controlled-release polymer scaffold from concentration data.

- Define Physics: Use Fick's law of diffusion:

∂C/∂t - D∇²C = 0. - Assimilate Data: Use sparse, noisy concentration measurements

C_obs(x_i, t_i)from imaging. - Build PINN: Represent both concentration

C_θ(x,t)and the unknown parameterD_θas trainable network outputs. - Define Loss:

L = 1/N_d Σ|C_θ - C_obs|² + 1/N_f Σ|∂C_θ/∂t - D_θ∇²C_θ|². - Train: Jointly optimize network weights and

D_θ. Penalty methods enhanceD_θstability. - Predict: Use calibrated

D_θto simulate release profiles for new scaffold geometries.

Table 1: Summary of PINN Performance in Selected Material Science Applications

| Application (Reference) | Key PDE/Physics | Data Requirement | Performance (vs. Traditional) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Stress Field (Raissi et al., 2019) | Navier's Equations (Elasticity) | Boundary data only | ~2-3% relative L2 error | Avoids costly mesh generation |

| Battery Electrode Degradation (Wu et al., 2023) | Phase-field Fracture Model | 20% of full-field data | 5x data efficiency gain | Identifies crack path w/ sparse data |

| Polymer Drug Release (Pant et al., 2022) | Fickian Diffusion-Advection | Sparse temporal profiles | Accurately infers diffusivity D |

Solves inverse problem concurrently |

| Catalyst Surface Reactivity (Lyu et al., 2022) | Reaction-Diffusion (Brusselator) | Limited noisy spectra | <5% parameter error | Robust to experimental noise |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Implementing PINNs in Materials Research

| Item / Solution | Function in PINN Experiment | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic Differentiation (AD) Library | Computes exact derivatives of network output w.r.t. inputs for PDE loss. | JAX, PyTorch, TensorFlow. JAX is often preferred for high-performance scientific computing. |

| Differentiable Physics Kernel | Encodes the specific PDE residual f in a differentiable manner. |

Custom layers using AD operators (e.g., grad, jacobian). Libraries like Modulus (NVIDIA) provide pre-built kernels. |

| Domain Sampling Strategy | Generates collocation points (N_f) and boundary/initial points (N_b). |

Latin Hypercube, Sobol sequences, or adaptive sampling based on residual. Critical for solution accuracy. |

| Loss Balancing Scheme | Manages weighting (λ) between L_data and L_PDE terms to stabilize training. |

Learned attention, NTK-based weighting, or gradient pathology algorithms (e.g., tanh scaling). |

| Optimizer Suite | Minimizes the composite, often stiff, loss landscape. | Adam (initial phase) + L-BFGS (fine-tuning) is a standard hybrid approach. |

| Benchmark Dataset / High-Fidelity Solver | Provides ground truth for validation and synthetic data generation. | COMSOL/ANSYS simulations, experimental Digital Image Correlation (DIC) data, or public repositories (e.g., Materials Project). |

Future Directions in Materials Discovery

PINNs are evolving into PINN-based frameworks for multiscale, multi-fidelity, and high-throughput discovery. Key future directions include:

- Hybrid and Multiscale PINNs: Coupling atomistic (DFT, MD) physics with continuum models to bridge scales.

- Bayesian PINNs: Quantifying prediction uncertainty, crucial for safety-critical material design.

- Generative PINNs: Integrating with variational autoencoders to design material microstructures that optimize a physical property.

- Foundation Models for Science: Pre-training PINNs on large corpora of PDE solutions for rapid fine-tuning to new material systems.

Diagram: PINNs in the AI for Materials Discovery Pipeline

Conclusion: PINNs offer a rigorous, flexible framework for integrating first-principles knowledge with modern data-driven approaches. For materials discovery, they reduce reliance on serendipity by enabling accurate predictions and inversions in data-sparse regimes, directly accelerating the design-test cycle for advanced materials and drug delivery systems.

Within the strategic pursuit of accelerated materials discovery and drug development, the integration of diverse data sources presents a critical path forward. Multi-fidelity learning (MFL) emerges as a cornerstone computational paradigm, systematically combining sparse, high-cost, high-accuracy experimental data (high-fidelity) with abundant, low-cost, lower-accuracy computational or proxy data (low-fidelity). This whitepaper details the technical frameworks, experimental protocols, and practical toolkit for deploying MFL, positioning it as an essential methodology for efficient exploration of vast chemical and materials spaces.

The AI for materials discovery thesis posits that future breakthroughs will hinge on the intelligent orchestration of heterogeneous data. The fidelity spectrum is characterized by an intrinsic cost-accuracy trade-off, as quantified below.

Table 1: Characteristic Data Fidelity Sources in Materials & Drug Discovery

| Fidelity Level | Exemplary Source | Typical Cost (Relative) | Estimated Error | Data Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (LF) | DFT Calculations | 1x | ~0.1-0.5 eV | High (10^4-10^6) |

| Medium (MF) | Semi-Empirical Methods | 5x | ~0.05-0.1 eV | Medium (10^3-10^4) |

| High (HF) | Experimental Synthesis & Characterization | 100x+ | <0.01 eV | Low (10^1-10^2) |

| Very High (VHF) | Synchrotron XRD/APS | 1000x+ | <0.001 eV | Very Low (10^0-10^1) |

Core Methodologies and Architectures

MFL models learn a mapping from an input space (e.g., molecular structure, composition) to the target property, while capturing the correlation between fidelities.

Linear Auto-Regressive Model

A foundational approach assumes a sequential relationship between fidelities.

y_t(x) = ρ * y_{t-1}(x) + δ_t(x)

where y_t is the output at fidelity level t, ρ is a scaling factor, and δ_t is the bias term learned from data at fidelity t.

Gaussian Process-Based Multi-Fidelity Learning

The most prevalent framework uses Gaussian Processes (GPs) to model correlations. The core concept is to construct a coupled covariance kernel:

k_{MF}((x, t), (x', t')) = k_x(x, x') ⊗ k_t(t, t')

where k_x models input similarity and k_t models inter-fidelity correlations.

Diagram 1: GP MFL Model Architecture

Deep Neural Network Approaches

Deep learning models, such as Multi-Fidelity Neural Networks (MFNN), use distinct network branches to process data from each fidelity before fusion.

Diagram 2: Multi-Fidelity Neural Network (MFNN)

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To validate an MFL approach for a materials discovery task (e.g., predicting perovskite solar cell efficiency), follow this structured protocol.

Protocol 1: MFL Model Training & Benchmarking

Objective: Compare the prediction accuracy and cost of an MFL model against a single-fidelity model using only high-fidelity data.

Materials & Data:

- LF Dataset: 10,000 material compositions with efficiency predicted from DFT (source: Materials Project).

- HF Dataset: 200 experimentally synthesized and characterized perovskites with measured PCE (source: literature curation).

- Holdout Test Set: 50 recent experimental records not used in training.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Standardize input features (compositional descriptors, band gap from DFT) and target variable (efficiency).

- Model Training:

- MFL Model: Train a Multi-Fidelity Gaussian Process (using a library like

gpfloworemukit) on the combined {LF (10k) + HF (150)} dataset. Use 50 HF samples as validation for hyperparameter tuning. - Baseline HF Model: Train a standard Gaussian Process only on the 150 HF training samples.

- MFL Model: Train a Multi-Fidelity Gaussian Process (using a library like

- Evaluation: Predict on the 50-sample holdout test set. Calculate key metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and

R².

Table 2: Protocol 1 Expected Results (Simulated)

| Model Type | Training Data Used | Test RMSE (PCE %) | Test MAE (PCE %) | R² Score | Effective Cost (Relative Units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Fidelity GP | 150 HF points | 1.85 | 1.52 | 0.76 | 15000 |

| Multi-Fidelity GP | 10k LF + 150 HF points | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 11500 |

| Single-Fidelity NN | 150 HF points | 2.10 | 1.68 | 0.69 | 15000 |

| Multi-Fidelity NN (MFNN) | 10k LF + 150 HF points | 1.15 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 11500 |

Protocol 2: Sequential Design via MFL (Active Learning)

Objective: Use MFL uncertainty to guide the next most informative experiment.

Procedure:

- Initialization: Train an initial MFL model on a small seed of HF data (e.g., 20 points) and the full LF dataset.

- Acquisition Loop: For

iin1...Niterations: a. Use the trained MFL model to predict the mean and variance (μ(x),σ²(x)) for all candidate materials in a large, unexplored pool (e.g., from LF source). b. Select the next candidatex*using an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement:EI(x) ∝ σ(x) * [Φ(z) + z * φ(z)], wherez = (μ(x) - y_best)/σ(x)). c. "Experiment": Acquire the high-fidelity ground truth forx*(simulate this from a held-out high-fidelity simulator or run actual experiment). d. Add the new(x*, y_HF)pair to the HF training set and retrain/update the MFL model. - Analysis: Plot the convergence of the best-discovered material property versus the cumulative number of high-fidelity experiments. Compare against random selection or single-fidelity guided search.

Diagram 3: MFL for Sequential Experimental Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential software, libraries, and data resources for implementing MFL in discovery research.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Multi-Fidelity Learning Implementation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in MFL | Key Feature / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emukit | Python Library | Multi-fidelity modeling & experimental design. | Built-in MFGP models, Bayesian optimization loops, and benchmarks. |

| GPy / GPflow | Python Library | Gaussian Process modeling foundation. | Provide flexible kernels for building custom MF covariance functions. |

| DeepHyper | Python Library | Scalable neural architecture & hyperparameter search. | Supports multi-fidelity early-stopping for efficient neural net training. |

| Materials Project | Database | Source of low-fidelity computational data. | Millions of DFT-calculated material properties for LF training. |

| AFLOW | Database | Source of low-fidelity computational data. | High-throughput DFT calculations for inorganic crystals. |

| PubChem | Database | Source of experimental bioactivity data (HF) & computed descriptors (LF). | Links compounds to experimental assay results. |

| Open Catalyst Project | Dataset | ML-ready dataset for catalysis. | Contains DFT relaxations (LF) and higher-level calculations (MF). |

| MODNet | Python Package | Materials property prediction with inherent multi-data source handling. | Designed for materials informatics, can weight data by fidelity. |

This whitepaper presents a detailed technical analysis of four pivotal case studies in AI-driven materials discovery, framed within a broader thesis on future research directions. The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) with high-throughput computation and automated experimentation is accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel materials. This paradigm shift is critical for addressing complex challenges in energy storage, pharmaceuticals, structural materials, and sustainable chemistry.

AI for Battery Electrolyte Discovery