Biopolymer Materials and Properties: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biopolymer materials, exploring their fundamental properties, advanced synthesis methodologies, and transformative applications in biomedicine and drug development.

Biopolymer Materials and Properties: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biopolymer materials, exploring their fundamental properties, advanced synthesis methodologies, and transformative applications in biomedicine and drug development. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it delves into the unique characteristics of natural and synthetic biopolymers—such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and tunable mechanical properties—that make them ideal for drug delivery systems, tissue engineering, and theranostic applications. The content further addresses current challenges in material optimization, scalability, and characterization, while offering insights into computational modeling and experimental validation strategies. By synthesizing the latest research and future directions, this guide serves as a critical resource for professionals navigating the evolving landscape of sustainable, high-performance biomaterials.

The Building Blocks of Life: Understanding Biopolymer Fundamentals and Sources

Biopolymers represent a distinct class of polymers integral to sustainable material research. They are defined as polymers produced by living organisms or synthesized from renewable biological resources [1] [2]. These materials are characterized by a structural backbone predominantly composed of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms, which facilitates their biodegradability, breaking them down into natural substances like carbon dioxide, water, and biomass through biological processes [2]. The fundamental distinction of biopolymers lies in their origin and eco-friendly lifecycle, positioning them as viable alternatives to conventional petroleum-based plastics. Their significance is increasingly pronounced in addressing global challenges such as plastic pollution, resource depletion, and the demand for biocompatible materials in advanced medical applications [1] [3].

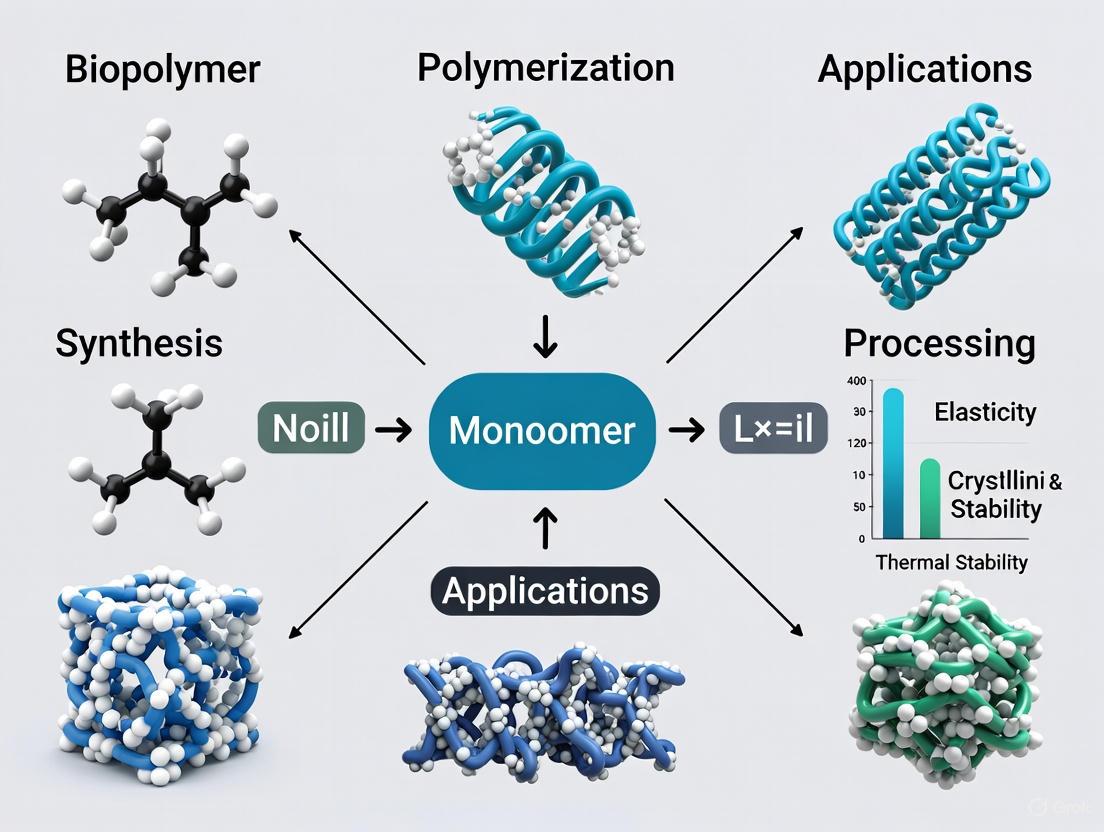

The classification of biopolymers is complex, reflecting their diverse origins and methods of production. As outlined in Figure 1, they can be systematically categorized based on their source and synthesis pathway. This foundational understanding is critical for researchers and drug development professionals who leverage these materials for their unique properties, including biodegradability, biocompatibility, low toxicity, and sustainability [2] [3]. The following sections will provide a detailed exploration of this classification, a comparative analysis with synthetic polymers, and the methodologies essential for their characterization and application in scientific research.

Figure 1: A comprehensive classification system for biopolymers, organized by their origin and primary sources [1] [2] [3].

Classification and Comparative Analysis

Key Classifications and Origins

Biopolymers are categorized primarily based on their origin and synthesis methods. As illustrated in Figure 1, the two primary categories are Natural Biopolymers, which are extracted directly from biological sources, and Synthetic Biopolymers, which are chemically synthesized from bio-derived monomers [2] [3].

Natural Biopolymers are further divided into three principal classes:

- Polysaccharides: This group includes ubiquitous polymers such as cellulose (sourced from agricultural trash like rice husk and seaweed), starch (from potatoes, maize, and cassava), chitosan (from fungi, mollusks, and crustaceans), and alginate (from seaweed) [2] [3]. Their molecular structures, composed of sugar monomers, make them highly suitable for drug delivery systems and food packaging.

- Proteins: Examples include collagen and gelatin (from cattle and pigs) and silk fibroin. These are valued in biomedical applications for their biofunctionality and adhesion properties [2] [3].

- Polyesters: A key example is Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), which are produced and stored as inclusion bodies within microorganisms like bacteria [1] [3].

Synthetic Biopolymers are synthesized chemically from monomers derived from renewable resources. The most prominent example is Polylactic Acid (PLA), produced via the fermentation of plant-based sugars (e.g., from corn or starch crops) followed by polymerization [1] [4]. While synthetic, these materials are considered biopolymers because they are derived from biomass.

The feedstocks for these polymers are vast and sustainable, encompassing plant sources (e.g., corn, potatoes, wheat, cotton), animal sources (e.g., cattle, fish, shrimp), microbial sources (e.g., algae, fungi, yeasts), and increasingly, agricultural wastes (e.g., apple pomace, tomato pomace, rice husks, sugarcane bagasse) [2] [3]. The utilization of waste streams is a key trend for 2025, supporting a circular economy model [1].

Biopolymers vs. Synthetic Polymers: A Technical Comparison

A critical understanding for researchers is the fundamental differences between biopolymers and conventional synthetic polymers, which dictate their application scope and performance. The comparative properties are quantified in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key properties between biopolymers and conventional synthetic polymers [2] [3].

| Property | Biopolymers | Synthetic Polymers | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Agro-resources, microorganisms [2] | Petroleum and gas [2] | Renewable vs. finite resource dependency |

| Biodegradability | Yes (enzymatic microbial action) [2] | No / Very slow [2] | Reduces environmental pollution and landfill waste |

| Toxicity | Low / Non-toxic, non-immunogenic [2] | High (potential for hormonally active agents) [2] | Superior for biomedical applications (e.g., drug delivery, implants) |

| Thermal & Mechanical Properties | Lower melting point, less stable, lower mechanical strength [2] [3] | High thermal stability and mechanical strength [2] | Limits use in high-performance applications without modification |

| Structural Complexity | Well-defined, precise 3D structures [2] | Stochastic, simpler structures [2] | Enables specific biological interactions |

| Cost | High (depends on type and production scale) [2] | Low [2] | A current barrier to widespread adoption |

The "green" credentials of biopolymers—including their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and sustainability—are their most significant advantages [2] [3]. However, their often inferior thermal and mechanical properties compared to synthetics present a research challenge. This is frequently addressed through blending, composite formation, and chemical functionalization to create advanced materials with enhanced performance for specific applications like drug delivery systems [3] [5].

Experimental Characterization and Synthesis

Synthesis and Processing Methodologies

The synthesis of biopolymers and their composite materials involves a range of techniques tailored to the polymer's origin and intended application. These methods can be broadly grouped into biological, chemical, and processing techniques.

Biological Synthesis is a sustainable approach where microorganisms are engineered to produce biopolymers intracellularly. For instance, bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis can be cultivated to produce Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). This process often utilizes agricultural or industrial waste as a feedstock, enhancing its sustainability [1]. The fermentation conditions—including carbon source, nutrient balance, and harvest time—are critical experimental variables that control the yield and molecular weight of the polymer [1] [3].

Chemical Synthesis involves the polymerization of bio-derived monomers. A prime example is the production of Polylactic Acid (PLA), which is typically synthesized in a two-step process: (1) fermentation of sugar feedstocks (e.g., from corn starch) to produce lactic acid, and (2) a metal-catalyzed polymerization of lactic acid monomers to form the long-chain polymer [1]. This method allows for precise control over the polymer's molecular weight and stereochemistry.

Material Processing Techniques are essential for transforming raw biopolymers into functional forms. Common laboratory and industrial methods include [2] [5]:

- Solvent Casting: Used for creating thin films, where a biopolymer is dissolved in a solvent and the solution is poured into a mold to evaporate.

- Electrospinning: Employed to produce nanofibers for drug delivery and tissue engineering by applying a high voltage to a biopolymer solution.

- Extrusion: A dominant method (holding 50% market share in processing [4]) for producing films and sheets, where biopolymer granules are melted and shaped through a die.

- Ionic Gelation/Coacervation: A key method for forming microspheres and nanoparticles, particularly with chitosan and alginate, by using cross-linking ions like tripolyphosphate [5].

Essential Characterization Techniques

Rigorous characterization is paramount to correlate the synthesis parameters with the resulting material properties. A standard experimental workflow employs the following techniques:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Used to identify functional groups and chemical bonds within the biopolymer, confirming successful synthesis or functionalization [1].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Provides detailed information on the polymer's chemical structure, composition, and purity [1].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): A thermal analysis technique that measures the glass transition temperature (Tg), melting point (Tm), and crystallinity of the biopolymer, which are critical for understanding its processing and stability [1].

- Mechanical Testing: Using universal testing machines to determine key properties such as tensile strength, elasticity (Young's modulus), and elongation at break [1]. These parameters are vital for applications requiring specific mechanical performance.

- Analysis of Biodegradation: Involves studying the degradation mechanisms and kinetics under various environmental conditions (e.g., in compost, soil, or simulated body fluids) to assess the rate at which microorganisms break down the polymer chains [1].

Figure 2: A generalized experimental workflow for the synthesis, processing, and characterization of biopolymer materials [1] [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential reagents, materials, and equipment for biopolymer research, particularly in drug delivery system (DDS) development.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | A natural polysaccharide; forms biodegradable nanoparticles and hydrogels via ionic gelation. | Targeted drug delivery, wound dressings, gene delivery (siRNA) [2] [5]. |

| Alginate | A natural polysaccharide; forms gentle gels with divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺). | Cell encapsulation, controlled drug release beads, wound healing [2] [5]. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A synthetic biopolymer; provides tunable mechanical strength and degradation rate. | 3D printed scaffolds, resorbable medical implants, sutures [1] [4] [6]. |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Microbial polyesters; offer high biodegradability and biocompatibility. | Medical implants, tissue engineering, compostable packaging [1] [4]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A crosslinking agent; enhances mechanical strength and stability of biopolymer matrices. | Crosslinking collagen scaffolds, chitosan microspheres [5]. |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | An ionic crosslinker; used for forming nanoparticles via electrostatic interaction. | Chitosan nanoparticle formation for drug encapsulation [5]. |

This technical guide has delineated the fundamental definition of biopolymers, drawing a clear distinction between their natural and synthetic origins, and has presented a systematic framework for their classification. The comparative analysis underscores a critical trade-off: while biopolymers offer unparalleled advantages in sustainability, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, they often require advanced processing and modification to meet the mechanical and thermal performance standards of their synthetic counterparts. The future of biopolymer research, particularly for drug development professionals, lies in the sophisticated design of composites and functionalized hybrids. Leveraging the experimental protocols and characterization techniques outlined herein will be paramount in developing the next generation of high-performance, application-specific biopolymer materials that align with the principles of a circular economy and advanced medical therapy.

Biopolymers represent a transformative class of materials defined by three essential properties: biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical strength. These characteristics position them as cornerstone solutions for addressing pressing global challenges in sustainability and advanced medicine. Within biomedical applications, biocompatibility ensures harmonious interaction with biological systems, preventing adverse immune responses and enabling use in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biodegradability allows controlled breakdown into non-toxic byproducts, eliminating the need for surgical removal and mitigating long-term environmental persistence. Meanwhile, mechanical strength provides the structural integrity necessary to withstand physiological stresses and maintain functionality throughout a device's intended lifespan. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, measurement methodologies, and advanced optimization strategies for these core properties, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for biopolymer research and development aligned with the demands of sustainable material science and advanced therapeutic applications.

Defining the Essential Properties

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility extends beyond simple non-toxicity to encompass a material's ability to perform its intended function without eliciting any detrimental local or systemic responses in the host organism. This property is paramount for applications involving direct biological contact, such as implantable devices, tissue scaffolds, and drug delivery systems. The biocompatibility of a biopolymer is governed by multiple factors, including its chemical composition, degradation products, surface morphology, and hydrophilicity. For instance, hyaluronic acid (HA) demonstrates exceptional biocompatibility due to its innate presence in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of human tissues, where it participates in critical biological processes including wound healing and tissue regeneration [7]. Its natural ligand-receptor interactions with CD44 and RHAMM receptors enable targeted therapeutic applications without provoking adverse immune reactions [7].

Biodegradability

Biodegradability refers to a material's capacity to break down into simpler compounds—typically water, carbon dioxide, and biomass—through the enzymatic action of microorganisms or physiological processes. The degradation mechanism, kinetics, and byproduct profile are critical design parameters for biopolymers. degradation can occur via hydrolysis, enzymatic cleavage, or oxidation, with rates influenced by crystallinity, molecular weight, and environmental conditions. In biomedical contexts, controlled biodegradability is essential, as illustrated by polylactic acid (PLA), where the higher-order structure dictates degradation behavior. Crystalline regions with densely folded molecular chains exhibit low molecular mobility and slow degradation, while non-crystalline regions with loosely packed chains demonstrate high mobility and faster breakdown [8]. This tunability allows researchers to engineer materials with degradation profiles matching specific therapeutic timeframes.

Mechanical Strength

Mechanical strength encompasses a material's ability to withstand external forces without deformation or failure, including properties such as tensile strength, compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, and fracture toughness. For biopolymers, achieving adequate mechanical performance while maintaining other essential properties presents significant challenges. Mechanical behavior is intrinsically linked to molecular structure; for example, the compressive strength of biopolymer-stabilized soils increases by 273% when xanthan gum (XG) and guar gum (GG) form synergistic composite structures [9]. Similarly, the mechanical integrity of HA hydrogels—manifested as viscoelasticity and shear-thinning properties—directly derives from their molecular architecture and extensive hydrogen bonding capacity [7].

Quantitative Property Analysis of Selected Biopolymers

Table 1: Mechanical and Physical Properties of Representative Biopolymers

| Biopolymer | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Degradation Time | Water Binding Capacity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Variable | 0.36-0.86 g water/g HA | Tissue engineering, drug delivery, cosmetics, ophthalmology [7] |

| Soy-based Bioplastic | Not Specified | Not Specified | Biodegradable | ~1.40% MAE in water absorption | Sustainable packaging, environmental biomaterials [10] |

| XG-GG Composite | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Soil stabilization (273% UCS increase) [9] |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Variable with crystallinity | Young's Modulus tunable via processing | Tunable via crystalline structure | Not Specified | Biodegradable films, medical implants [8] |

Table 2: Experimental Data Validation and Error Margins in Biopolymer Research

| Testing Methodology | Material System | Key Parameters Measured | Error Margins/Validation Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Based Modeling (ANFIS/ANN) | Soy-based Bioplastic | Water absorption, Solubility, Biodegradability | MAE: ~1.40% (water), 0.87% (methanol) | [10] |

| GA-BP Neural Network | Biopolymer-Fiber Stabilized Soil | 7-day Compressive Strength | R²: 0.887, MSE: 1413 | [9] |

| Bayesian Optimization with CNN | Polylactic Acid Films | Enzymatic degradation rate, Strain at break, Young's modulus | RMSE reduction via denoised NMR data | [8] |

Experimental Methodologies for Property Characterization

Biocompatibility Assessment

Biocompatibility evaluation requires a tiered approach employing both in vitro and in vivo methods. Initial screening involves cytocompatibility tests using cell lines relevant to the intended application:

- Cell Viability Assays: MTT, XTT, or PrestoBlue assays quantify metabolic activity of cells cultured with biopolymer extracts or in direct contact.

- Hemocompatibility Testing: For blood-contacting devices, hemolysis assays and platelet adhesion studies evaluate erythrocyte membrane integrity and thrombogenic potential.

- Cytokine Profiling: ELISA-based detection of inflammatory markers (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) from macrophages exposed to biopolymer degradation products.

- In vivo Implantation Studies: Subcutaneous or intramuscular implantation in animal models followed by histological analysis of the implant site for fibrous capsule formation, inflammatory cell infiltration, and tissue integration.

Hyaluronic acid's biocompatibility assessment exemplifies this comprehensive approach, where its innate role in ECM contributes to its excellent tissue compatibility, minimal immune activation, and promotion of cellular processes without cytotoxicity [7].

Biodegradability Testing

Standardized biodegradability testing evaluates degradation kinetics and byproduct toxicity under conditions mimicking the intended environment:

Enzymatic Degradation Protocol:

- Prepare phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with and without specific enzymes (e.g., protease, lipase, lysozyme) relevant to the application site.

- Sterilize biopolymer samples (e.g., films, scaffolds) and record initial mass (W₀) and dimensions.

- Incubate samples in enzyme solutions at 37°C with constant agitation; maintain enzyme-free controls.

- At predetermined intervals, remove samples (n=5-6 per group), rinse thoroughly with deionized water, and dry to constant weight.

- Calculate mass loss percentage: [(W₀ - Wₜ)/W₀] × 100.

- Characterize degradation products using HPLC, MS, or GPC.

Soil Burial Test:

- Bury pre-weighed samples in standardized soil at controlled moisture content (e.g., 40-60% water holding capacity).

- Maintain at constant temperature (e.g., 25-30°C) for duration of study.

- Retrieve triplicate samples periodically, clean gently, dry thoroughly, and measure mass loss.

- Analyze surface morphology changes via SEM.

Research on PLA films demonstrates how low-field NMR relaxation curves can predict degradation behavior by quantifying molecular mobility in crystalline, intermediate, and non-crystalline regions, enabling accelerated material development without lengthy degradation tests [8].

Mechanical Characterization

Mechanical property assessment varies based on the material form and intended application:

Tensile Testing for Films and Fibers (ASTM D882):

- Prepare standardized dog-bone specimens (e.g., 50 mm gauge length, 10 mm width).

- Condition samples at controlled temperature and humidity (e.g., 23°C, 50% RH) for 24 hours.

- Mount specimens in universal testing machine with appropriate load cell.

- Apply uniaxial tension at constant crosshead speed (e.g., 10 mm/min) until failure.

- Calculate tensile strength, elongation at break, and Young's modulus from stress-strain curves.

Compression Testing for Hydrogels and Composites:

- Prepare cylindrical specimens (e.g., 20 mm diameter, 20 mm height).

- Conduct unconfined compression tests at constant strain rate.

- Determine compressive strength and modulus from the linear region of stress-strain curve.

Advanced Rheological Characterization:

- Perform oscillatory rheometry to determine viscoelastic properties (storage modulus G', loss modulus G").

- Conduct frequency sweeps (0.1-100 rad/s) at constant strain within linear viscoelastic region.

- Perform temperature ramps to evaluate thermal transitions.

For biopolymer-stabilized soils, research demonstrates that 7-day unconfined compressive strength (UCS) testing provides a standardized metric for comparing mechanical enhancement, with optimal biopolymer dosages typically between 0.5% to 1.0% achieving maximum strength improvements [9].

Property Optimization Through Advanced Modeling

AI-Driven Formulation Design

Artificial intelligence approaches have revolutionized biopolymer development by enabling precise prediction of composition-property relationships:

Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Statistical optimization of multi-component systems, such as the combination of soy, corn, glycerol, vinegar, and water for bioplastic formulation, allows researchers to identify optimal ratios that maximize desired properties while minimizing resource consumption [10].

Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): These AI tools model complex non-linear relationships between processing parameters and resultant properties, achieving high predictive accuracy as demonstrated by the low mean absolute error in water absorption (~1.40%) and methanol absorption (0.87%) for soy-based bioplastics [10].

Genetic Algorithm-Optimized Backpropagation (GA-BP) Neural Networks: For biopolymer-fiber stabilized soils, GA-BP models significantly outperform standard BP and support vector machine approaches, with R² values of 0.887 compared to 0.714 and 0.554, respectively, enabling accurate prediction of mechanical behavior from composition data [9].

Bayesian Optimization for Process Parameters

Bayesian optimization (BO) represents a powerful machine learning approach for efficiently navigating complex parameter spaces with minimal experimental iterations:

Integration with Low-field NMR: CNN-based feature extraction from NMR relaxation curves creates latent space representations that correlate with material properties, enabling optimization of process conditions without direct property measurement [8].

Process Optimization Workflow:

- Acquire low-field NMR relaxation curves for varied process conditions (e.g., crystallization temperature, time, nucleating agent concentration).

- Apply CNN denoising to extract relevant features and reduce noise.

- Construct latent space representations encoding molecular structure information.

- Use Bayesian optimization to identify process conditions that maximize target properties.

- Validate predictions with limited experimental verification.

This approach is particularly valuable for biodegradable polymers where traditional degradation testing requires extended timeframes (30+ days), enabling accelerated material development cycles [8].

Figure 1: Machine Learning-Driven Optimization Workflow for Biopolymer Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biopolymer Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Extracellular matrix mimic; Drug delivery ligand; Tissue engineering scaffold | Molecular weight: 60 kDa - 2.5 MDa; Water retention: 0.36-0.86 g/g | Biomedical applications targeting CD44 receptors [7] |

| Xanthan Gum (XG) | Soil stabilization biopolymer; Viscosity modifier | Soluble in hot/cold water; Pseudoplastic behavior; pH stable | Enhances soil compressive strength in composite with GG [9] |

| Guar Gum (GG) | Soil stabilization biopolymer; Thickening agent | High galactose branching; Excellent viscosity enhancement | Synergistic composite with XG for soil stabilization [9] |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biodegradable polymer for films and implants | Crystallinity tunable (75-120°C); Enzymatically degradable | Model polymer for Bayesian optimization studies [8] |

| Soy Biomass | Feedstock for sustainable bioplastics | Renewable resource; Biodegradable | Base material for AI-optimized bioplastic formulations [10] |

Structural Property Relationships in Biopolymers

The essential properties of biopolymers derive fundamentally from their molecular and supramolecular organization, creating intricate structure-function relationships that inform material design:

Figure 2: Structure-Property Relationships Governing Biopolymer Performance

The strategic integration of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical strength defines the functional core of advanced biopolymer systems. These properties are not independent but exist in complex interrelationships that must be balanced for specific applications. Advanced characterization methodologies, particularly those leveraging machine learning and predictive modeling, now enable researchers to navigate this multi-dimensional design space with unprecedented precision. The continued development of biopolymers tailored for biomedical and environmental applications hinges on a fundamental understanding of the structure-property relationships outlined in this technical guide, coupled with the implementation of robust experimental and computational frameworks for property optimization. As the field advances, the integration of AI-driven design with high-throughput experimental validation promises to accelerate the development of next-generation biopolymer materials with precisely tuned functional characteristics.

The transition toward a circular bioeconomy has intensified the search for sustainable alternatives to conventional, petroleum-based materials. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the primary natural sources for biopolymer derivation: plants, animals, microorganisms, and agricultural waste. These feedstocks are rich in diverse biopolymers—including polysaccharides, proteins, and polyesters—which are characterized by their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and often, bioactive properties. The document meticulously details the fundamental properties and extraction methodologies for key biopolymers, supported by structured quantitative data. Furthermore, it outlines advanced experimental protocols for extraction and processing, visualizes critical metabolic pathways for microbial synthesis, and catalogues essential research reagents. While significant progress has been made in material performance, challenges in scalability, economic viability, and regulatory alignment remain active frontiers for research. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and technical procedures to advance the development and application of these sustainable materials.

Biopolymers, which are polymers produced by living organisms, form the basis for a new generation of sustainable materials aimed at reducing reliance on fossil fuels. The global waste crisis, with 2.24 billion tons of municipal solid waste generated annually, underscores the urgency of developing sustainable material solutions [11]. These materials are pivotal for a circular economy, transforming waste into valuable products and aligning with global sustainability goals such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals [12] [11]. Deriving biopolymers from renewable and waste sources offers a dual benefit: it mitigates the environmental impact of waste accumulation while providing a low-cost, renewable feedstock for material production [12] [13]. The primary sources for these biopolymers can be categorized into plants, animals, microorganisms, and agricultural waste streams, each offering a unique portfolio of polymer types with distinct characteristics and applications, particularly in packaging and biomedical fields [14] [15] [11].

Comprehensive Source Categorization and Properties

Biopolymers derived from natural sources can be systematically classified based on their chemical structure and origin. The following sections and tables provide a detailed overview of the primary biopolymers, their sources, and key characteristics.

Plant-Derived Biopolymers

Plants are a rich source of structural polysaccharides. Cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin are major components of plant cell walls, while starch serves as an energy reserve.

Table 1: Key Plant-Derived Biopolymers and Their Properties

| Biopolymer | Primary Plant Sources | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Wood, cotton, hemp, rice husks, wheat straw [12] [16] | High tensile strength, hydrophilic, biodegradable, biocompatible [16] | Drug delivery matrices, composites, food packaging [14] [16] |

| Starch | Corn, potato, cassava, wheat [12] [13] | Renewable, biodegradable, good film-forming ability [12] [17] | Bioplastics, edible films, food packaging [12] [11] |

| Pectin | Citrus peels, apple pomace [11] | Gelling, thickening, and stabilizing agent [11] | Edible films, drug delivery systems, food stabilizers [15] [11] |

Animal-Derived Biopolymers

Animal-derived biopolymers are primarily proteins and complex polysaccharides that offer exceptional biocompatibility, making them particularly suitable for biomedical applications.

Table 2: Key Animal-Derived Biopolymers and Their Properties

| Biopolymer | Primary Animal Sources | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan/Chitin | Crustacean shells (shrimp, crab) [15] [11] | Biocompatible, biodegradable, antimicrobial, mucoadhesive [15] | Wound healing, drug delivery (e.g., transdermal films) [15] [17] |

| Collagen | Animal skin, bones (bovine, porcine) [11] | Excellent biocompatibility, forms strong fibers [11] | Biomedical scaffolds, drug delivery systems [17] [11] |

| Gelatin | Hydrolyzed collagen [17] | Film-forming, biocompatible, biodegradable [17] | Pharmaceutical capsules, food packaging [17] |

Microbial Biopolymers

Microorganisms can synthesize a range of biopolymers, such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and exopolysaccharides, often through fermentation processes that can utilize waste streams as a carbon source.

Table 3: Key Microbial-Derived Biopolymers and Their Properties

| Biopolymer | Producing Microorganisms | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) | Cupriavidus necator, Bacillus spp. [11] [13] | Biodegradable, thermoplastic, biocompatible [13] | Biodegradable packaging, medical implants [12] [13] |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Fermentation (via lactic acid) [12] [13] | High strength, biodegradable, compostable [12] | Food packaging, biomedical devices [12] |

| Microbial Cellulose | Bacteria (e.g., Gluconacetobacter), Fungi [18] | High purity, high water-holding capacity, high mechanical strength [18] | Wound dressings, drug delivery, cosmetics [18] |

Agricultural Waste Derivatives

Agricultural waste provides a abundant and low-cost feedstock for biopolymer production, valorizing residues that would otherwise be burned or sent to landfills. The composition of these wastes directly influences the yield and type of extractable biopolymer.

Table 4: Biopolymer Potential of Major Agricultural Waste Streams

| Agricultural Waste | Lignocellulosic Composition | Primary Biopolymers Extractable | Estimated Global Generation (2025) [11] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane Bagasse | Cellulose (~40-50%), Hemicellulose (~25-35%), Lignin (~20-25%) [11] | Cellulose, nanocellulose, lignin [14] [11] | ~279 million metric tons/year [11] |

| Rice Husks | Cellulose (~30-45%), Hemicellulose (~20-30%), Lignin (~15-20%) [12] [11] | Cellulose, silica, lignin [12] [16] | ~150 million metric tons/year [11] |

| Fruit Peels (Citrus) | Pectin, Cellulose, Hemicellulose [11] | Pectin, cellulose [11] [16] | Part of ~1400 MMT food/organic waste [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Cellulose Extraction from Agricultural Waste (Rice Husk/Orange Peel)

This acid-base-chemical bleaching method is adapted from established procedures for purifying cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass [16].

- Raw Material Pretreatment: Wash the rice husks or orange peels thoroughly with distilled water to remove dirt and soluble impurities. Dry in an oven at 60°C until a constant weight is achieved. Mill the dried biomass and sieve to a uniform particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Alkali Treatment (Delignification): Suspend the milled biomass in a 4% (w/v) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (g/mL). Heat the mixture at 80°C for 2 hours with constant stirring. After cooling, filter the residue and wash repeatedly with distilled water until the filtrate reaches a neutral pH.

- Acid Treatment (Hydrolysis): Treat the alkali-insoluble residue with a 2% (w/v) hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (g/mL). Heat at 70°C for 1 hour with stirring. Filter and wash the solid residue with distilled water until neutral.

- Bleaching (Purification): To the resulting solid, add an acetate buffer solution (pH 4.5) and sodium chlorite (NaClO₂) at a concentration of 1.5% (w/v). Incubate the mixture at 70°C for 2 hours. Filter and wash the bleached cellulose thoroughly with distilled water and ethanol.

- Drying: The purified cellulose is dried in an oven at 50°C for 24 hours. The final product should be a white, fibrous powder. Yield and purity can be confirmed via Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to show removal of lignin and hemicellulose peaks, and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to determine crystallinity [16].

Protocol for Microbial Production of PHA from Agri-Waste

This protocol outlines the microbial fermentation process for producing Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) using agri-waste hydrolysates as a carbon source [11] [13].

- Strain Selection and Inoculum Preparation: Select a suitable microbial strain such as Cupriavidus necator (e.g., ATCC 17699). Inoculate a loopful of the strain from a stock culture into a nutrient-rich medium (e.g., LB) and incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 24 hours to prepare the seed culture.

- Agri-Waste Hydrolysate Preparation: Hydrolyze starchy (e.g., potato peel) or cellulosic (e.g., corn husk) agri-waste to fermentable sugars. For starch, use enzymatic hydrolysis with amylases. For cellulose, a pretreatment (e.g., with dilute acid or alkali) followed by enzymatic saccharification using cellulases is required. Filter the hydrolysate and adjust the pH to 7.0.

- Fermentation in a Nitrogen-Limited Medium: Use a mineral salt medium for fermentation. The key is to create an environment with a high carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio to trigger PHA accumulation. The agri-waste hydrolysate is the primary carbon source.

- Medium Composition (per liter): Agri-waste hydrolysate (equivalent to ~20 g/L sugars), (NH₄)₂SO₄ (1.0 g/L), KH₂PO₄ (2.0 g/L), Na₂HPO₄ (2.0 g/L), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.2 g/L), and 1 mL of trace element solution.

- Process: Inoculate the fermentation medium with 5-10% (v/v) of the seed culture. Incubate in a bioreactor or shake flasks at 30°C with adequate aeration (e.g., 200-300 rpm) for 48-72 hours.

- PHA Extraction and Recovery: Harvest cells by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min). Wash the cell pellet with distilled water. To extract PHA, lyophilize the cells and use a Soxhlet apparatus with hot chloroform or dichloromethane as the solvent for 12-24 hours. Precipitate the polymer by adding the concentrated extract to cold methanol or ethanol. Recover the purified PHA polymers by filtration or evaporation [13].

Metabolic Pathways and Workflow Visualization

PHA Biosynthesis Pathway in Bacteria

The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic pathways involved in the microbial synthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) from various carbon sources, a process critical for sustainable biopolymer production [13].

Diagram 1: Microbial PHA Biosynthesis Pathways. This figure outlines the primary metabolic routes in bacteria like Cupriavidus necator for converting carbon sources from agri-waste into PHA biopolymers. Key precursors from central metabolism and β-oxidation are polymerized by PHA synthase into intracellular granules [13].

Experimental Workflow for Agri-Waste Valorization

This diagram provides a high-level overview of the integrated experimental workflow for converting agricultural waste into functional biopolymer-based materials.

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Agri-Waste Valorization. This chart depicts the multi-stage process from raw waste to finished product, highlighting key stages and the critical characterization steps required at each phase to ensure material quality and functionality [14] [12] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for research in the extraction, processing, and characterization of biopolymers from primary sources.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biopolymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkali treatment for delignification of plant biomass [16]. | Effective for breaking lignin-carbohydrate complexes. Concentration typically 2-5% w/v. |

| Sodium Chlorite (NaClO₂) | Chemical bleaching agent for purifying cellulose [16]. | Used with acetate buffer (pH ~4.5) to generate chlorine dioxide for lignin removal. |

| Chloroform | Organic solvent for extracting microbial PHA biopolymers [13]. | Commonly used in Soxhlet extraction. Requires careful handling and fume hood use. |

| Commercial Cellulases | Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose to fermentable sugars [11]. | Critical for preparing agri-waste hydrolysates as carbon sources for microbial fermentation. |

| Glycerol | Plasticizer for biopolymer films [17]. | Reduces brittleness and improves flexibility of films by reducing intermolecular forces. |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., Genipin, Glutaraldehyde) | Enhance mechanical strength and stability of biopolymer matrices [17]. | Glutaraldehyde is effective but requires care due to toxicity; genipin is a natural alternative. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer | Characterizes chemical functional groups and confirms biopolymer purity [16]. | Identifies removal of lignin (peak at ~1500 cm⁻¹) in cellulose extraction. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Assesses thermal stability and decomposition profile of biopolymers [16]. | Determines degradation onset temperature and residual ash content. |

| X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Determines the crystallinity and crystal structure of biopolymers [16]. | Crystallinity Index (CI) can be calculated using the Segal method. |

Smart biopolymers, also referred to as stimuli-responsive or intelligent biopolymers, are a class of materials derived from biological sources that possess the unique ability to undergo reversible changes in their physical or chemical properties in response to specific external triggers [19] [20]. This adaptive behavior is inspired by natural biological systems, which follow a mechanism of sensing, reacting, and learning to survive [19]. The responsiveness of these biopolymers can be engineered for various stimuli, including physical factors like temperature and magnetic fields, chemical signals such as pH changes, and biological triggers [21].

The primary appeal of biopolymers lies in their inherent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and derivation from renewable resources, making them a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic polymers [1] [22]. When combined with "smart" responsive properties, they become powerful materials for advanced applications, particularly in biomedical fields like drug delivery, tissue engineering, and theranostics [20] [22]. This whitepaper explores the fundamental mechanisms, material systems, and experimental methodologies governing the responsive behavior of smart biopolymers to pH, temperature, and magnetic fields, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Stimuli-Responsive Behavior

The responsive behavior of smart biopolymers arises from specific, reversible changes in their molecular structure and intermolecular forces when exposed to an external trigger. The mechanism varies depending on the type of stimulus.

pH-Responsive Mechanisms

pH-responsive biopolymers contain functional groups that can accept or donate protons (i.e., ionizable groups), leading to a change in the net charge of the polymer chain. The response is triggered by the ionization state change of these functional groups at specific pH values [21] [22].

- Key Ionizable Groups: Common ionizable groups in biopolymers include carboxylic acids (e.g., in alginate, hyaluronic acid), which are deprotonated at high pH, and amine groups (e.g., in chitosan), which are protonated at low pH [21].

- Swelling/Deswelling: In an aqueous environment, the electrostatic repulsion between similarly charged groups along the polymer chain leads to an expansion of the polymer network. A shift in pH that neutralizes these charges causes the network to collapse due to diminished repulsive forces [22]. For instance, a chitosan-based hydrogel swells in an acidic environment (pH < 6.3) where its amine groups are protonated, leading to charge repulsion [21].

Thermo-Responsive Mechanisms

Thermo-responsive biopolymers exhibit a reversible change in solubility in response to temperature. The most common mechanism is based on a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) [21].

- LCST Behavior: Below the LCST, the polymer chains are hydrated and soluble in water. As the temperature rises above the LCST, the polymer undergoes a phase transition; the chains become dehydrated and collapse, leading to precipitation or gel shrinkage. This is driven by a delicate balance between hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions within the polymer [21].

- Molecular Interactions: Below the LCST, hydrogen bonding between polymer chains and water molecules dominates. Above the LCST, entropic effects and intramolecular hydrophobic interactions become dominant, leading to chain collapse and expulsion of water [21]. A widely studied example is Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM), but biopolymer counterparts like modified cellulose or chitosan can also exhibit this behavior [21].

Magneto-Responsive Mechanisms

Magneto-responsive behavior is typically not an intrinsic property of biopolymers but is engineered by incorporating magnetic nanoparticles, such as iron oxides (e.g., Fe₃O₄ magnetite) [22].

- Inductive Heating: When subjected to an alternating magnetic field, these nanoparticles generate heat through mechanisms like Neel and Brownian relaxation. This heat can then trigger a secondary response in a thermo-responsive biopolymer matrix, leading to controlled drug release or gel contraction [22].

- Direct Manipulation: The magnetic moment of the embedded nanoparticles can also allow the entire composite material to be manipulated or guided by an external magnetic field gradient, which is useful for targeted delivery [22].

Table 1: Summary of Key Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms

| Stimulus | Key Functional Group/Component | Primary Mechanism | Resulting Physical Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Ionizable groups (e.g., carboxylic acids, amines) | Change in ionization state & electrostatic repulsion | Swelling or deswelling of polymer network |

| Temperature | Balanced hydrophilic/hydrophobic moieties | Shift in hydrogen bonding & hydrophobic interactions (LCST) | Soluble-to-insoluble transition; gel volume change |

| Magnetic Field | Incorporated magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) | Inductive heating (hyperthermia) or direct force | Thermally-induced response or material movement |

Key Material Systems and Their Properties

Various natural and functionalized biopolymers form the backbone of stimuli-responsive material systems. Their properties can be finely tuned through chemical modification and composite formation.

Natural Biopolymer Scaffolds

Naturally derived biopolymers provide a biocompatible and biodegradable foundation that can be modified to be stimuli-responsive.

- Chitosan: A cationic polysaccharide known for its pH-responsive behavior due to the protonation of its primary amine groups in acidic environments [22].

- Alginate: An anionic polysaccharide that can form gels in the presence of divalent cations like Ca²⁺. Its carboxylic acid groups make it pH-responsive, swelling at higher pH values [22].

- Starch: An abundant polysaccharide consisting of amylose and amylopectin. Its film-forming ability and modifiability make it a suitable matrix for stimuli-responsive coatings, such as in controlled-release fertilizers [23].

- Cellulose and its derivatives: Materials like carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) can be engineered to be responsive to temperature and pH, exhibiting significant swelling in water [22].

Functionalized and Synthetic Hybrid Systems

To enhance responsiveness and mechanical properties, natural biopolymers are often chemically modified or combined with synthetic polymers.

- Grafting: Functional groups or polymer chains (like PNIPAM) are attached to the biopolymer backbone to introduce new responsive properties, such as thermo-sensitivity to chitosan [22].

- Cross-linking: Forms bonds between polymer chains to improve mechanical strength and thermal stability, and can be used to create hydrogels with controlled swelling behavior [22].

- Nanocomposites: Biopolymers are combined with nanomaterials such as magnetic nanoparticles for magneto-responsiveness, or nanofillers like biochar or SiO₂ to enhance mechanical robustness and introduce multi-stimuli responsiveness [21] [23].

Table 2: Swelling Properties of Common Biopolymer-Based Hydrogels

| Biopolymer | Swelling Degree (g/g) in Water | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 1.65 to 3.85 [22] | pH, ionic cross-linking (Ca²⁺) |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | 50 to 200 [22] | pH, degree of substitution |

| Starch | 500 to 1200% [22] | Amylose/amylopectin ratio, temperature |

| Chitosan | >100% [22] | pH, degree of deacetylation |

| Cellulose | 200 to 1000 [22] | Crystallinity, functionalization |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

The development and analysis of smart biopolymers require specific synthesis protocols and characterization techniques to validate their responsive behavior and functional performance.

Synthesis and Fabrication Methods

The choice of synthesis method dictates key properties of the resulting micro- or nano-gels, including size, polydispersity, and functionality.

- Precipitation Polymerization: A widely used technique for producing relatively monodisperse microgel particles, ideal for thermo-responsive polymers like PNIPAM. Particle nucleation occurs in a narrow time window, and growth proceeds via diffusion of monomers to existing nuclei [21].

- Emulsion Polymerization: This method involves polymerizing monomers within water droplets stabilized by surfactants in an oil continuous phase. It is versatile for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic polymers and allows for efficient production of small particles [21].

- Microfluidic Fabrication: This technique offers superior control over particle size and monodispersity by forming monodisperse droplets of monomers or polymers through precise manipulation of liquid streams, followed by cross-linking. It is excellent for generating larger microgels (1-30 µm) and encapsulating cells or nanoparticles [21].

Diagram 1: Microgel Synthesis Workflows

Key Characterization Techniques

Characterization is essential for linking the material's structure to its performance and responsive properties.

- Swelling Studies: The equilibrium swelling ratio (SR) or swelling degree (SD) is a fundamental metric calculated as SR = (Mswollen - Mdry) / M_dry, where M is mass. This property is measured under different conditions (e.g., varying pH or temperature) to quantify the material's responsiveness [22].

- Chemical Structure Analysis: Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) are used to confirm chemical composition, successful modification, and the presence of specific functional groups [1].

- Thermal Analysis: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is critical for identifying thermal transitions, most notably the LCST of thermo-responsive polymers [1].

- Mechanical Properties: Universal testing machines are used to measure tensile strength, elasticity, and modulus, ensuring the material meets the mechanical requirements for its intended application [1].

Protocol: Evaluating pH-Dependent Swelling Behavior

This protocol provides a standardized method to quantify the pH-responsive behavior of a biopolymer hydrogel.

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize the hydrogel and dry it completely to obtain the dry mass (M_dry).

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a series of buffer solutions covering the desired pH range (e.g., pH 3.0 to 8.0).

- Swelling Incubation: Immerse the pre-weighed dry hydrogel samples in the different pH buffers. Maintain a constant temperature.

- Equilibrium Swelling: Allow the samples to swell until equilibrium is reached (no further mass change). Gently remove samples, blot excess surface liquid, and immediately weigh to obtain the swollen mass (M_swollen).

- Data Calculation & Analysis: Calculate the Swelling Ratio (SR) at each pH using the formula: SR = (Mswollen - Mdry) / M_dry. Plot SR versus pH to visualize the swelling transition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Smart Biopolymer Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Building blocks for imparting stimuli-responsiveness. | N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) for thermo-response [21]; Ionic monomers like acrylic acid (pH-response) [21]. |

| Natural Biopolymers | Sustainable, biocompatible base materials. | Chitosan, alginate, starch, cellulose derivatives (e.g., CMC) [23] [22]. |

| Cross-linkers | Form 3D networks to create hydrogels/microgels; can be degradable. | Bis-acrylamides; degradable cross-linkers like disulfides or peptides for biodegradability [21]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Impart magneto-responsiveness for targeting or inductive heating. | Iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄); surface functionalization is often required for stable incorporation [22]. |

| Radical Initiators | Initiate polymerization reactions. | Ammonium persulfate (APS), Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) – choice depends on synthesis temperature [21]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow for Multi-Stimuli Response

Smart biopolymer systems can be designed to process multiple environmental signals in a logical manner, creating sophisticated, application-specific behaviors. The following diagram illustrates a conceptual pathway for a multi-stimuli-responsive system, such as one designed for targeted drug delivery in a tumor microenvironment.

Diagram 2: Multi-Stimuli Response Logic Pathway

Smart biopolymers represent a transformative frontier in material science, merging the sustainability of bio-based resources with the sophisticated, adaptive functionality of stimuli-responsive behavior. A deep understanding of the mechanisms driven by pH, temperature, and magnetic fields—coupled with robust experimental protocols for synthesis and characterization—enables researchers to tailor these materials for precision applications. While challenges in scalability, cost, and multi-stimuli coordination remain, the continued innovation in this field holds the promise of dynamically adjustable materials that can significantly advance biomedical technologies, environmental remediation, and beyond.

The field of biopolymer science is increasingly guided by a fundamental principle: structural hierarchy is the key to advanced functionality. Realizing the full potential of biopolymers in demanding applications such as drug delivery, regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering requires a deep understanding of the intricate relationships between a material's molecular architecture and its macroscopic properties [24]. This in-depth technical guide explores the design principles and methodologies for engineering biopolymer materials across multiple length scales, from the precise control of monomer sequences to the fabrication of complex three-dimensional architectures.

The conventional, serial approach to biopolymer design—involving synthesis, characterization, and functional testing—has proven inefficient, often failing to yield materials with the precise combination of features required for advanced biomedical applications [24]. An integrated strategy, which synergistically combines bottom-up computational modeling with advanced synthesis and processing techniques, presents a powerful alternative to accelerate the design process and unlock new material functionalities [24]. This guide examines this integrated approach, providing a framework for researchers to navigate the complex design space of hierarchical biopolymer materials.

The Hierarchical Design Paradigm

Biopolymers exhibit structural organization across several distinct length scales, each contributing to the overall material performance. The design paradigm involves the deliberate engineering of each level of this hierarchy.

- Monomer Sequence: The primary structure, defined by the specific order of amino acids, sugars, or other monomers, dictates the polymer's fundamental folding, self-assembly behavior, and bioactivity [25] [24]. Sequence-defined biomimetic polymers are engineered to bridge the gap between synthetic materials and biological precision [25].

- Secondary and Tertiary Structure: The chain folds into local motifs (e.g., β-sheets, α-helices) and overall three-dimensional conformations, which are influenced by both the monomer sequence and processing conditions [24].

- Supramolecular Assembly: Individual polymer chains organize into higher-order structures, such as fibrils, networks, or porous matrices, through non-covalent interactions [26].

- Macro-scale Architecture: The final material form—be it a hydrogel, a fibrous scaffold, or a porous foam—is defined by processing techniques that control the bulk morphology, anisotropy, and porosity on the micrometer to millimeter scale [26] [27].

Understanding and controlling the interconnections between these levels is critical for tailoring functional properties, such as mechanical strength, degradation kinetics, and cellular interactions [24].

Monomer Sequence: The Foundation of Function

Control at the monomeric level provides the most fundamental tool for dictating a biopolymer's properties. Precision in synthesis allows for the incorporation of specific chemical functionalities that direct folding, assembly, and recognition.

Table 1: Methods for Synthesizing Sequence-Defined Polymers

| Method | Type of Polymer | Key Outcome/Merits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant DNA | Peptide polymers | High-fidelity production of high molecular weight, monodisperse proteins; site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids [24]. | Requires biological expression systems; may be limited in scale. |

| Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis | Short peptides | Enables virtually unlimited sequence-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids and versatile peptide modifications [24]. | Typically limited to shorter peptide chains due to yield and efficiency. |

| Catalyzed Enzymatic Polymerization | Polysaccharides | Allows for "living" polymerization with predictable molecular weight and low polydispersity [24]. | Specific to certain polymer classes and monomer types. |

The strategic design of monomer sequences enables a wide range of biomedical applications. For instance, sequence-controlled polymers can enhance nucleotide delivery systems for gene therapy, improve the specificity of lectin and protein inhibition, and create novel antimicrobial peptides that mimic natural host defense molecules [25]. This precision at the molecular level is a prerequisite for engineering predictable and complex behavior at larger scales.

From Chains to Networks: Engineering Secondary and Supramolecular Structures

The transition from a linear polymer chain to a structured material is governed by the formation of secondary structures and their subsequent supramolecular assembly. This process can be guided by both the polymer's intrinsic sequence and external processing conditions.

Molecular-level engineering of biopolymer-based hydrogels offers a prime example of this principle. Advanced network design strategies are used to tailor the mechanical and responsive properties of these hydrogels:

- Double Networks (DN): Combining two interpenetrating networks with contrasting properties to create tough, resilient hydrogels [26].

- Interpenetrating Networks (IPN): Two or more networks are entangled but not covalently linked, allowing for independent tuning of different material characteristics [26].

- Supramolecular Assemblies: Utilizing transient, non-covalent bonds (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, host-guest chemistry) to create dynamic and self-healing materials [26].

Processing techniques are equally critical for directing this assembly into hierarchical structures:

- Hofmeister Effect-Induced Chain Aggregating: Uses specific ions to modulate polymer solubility, leading to controlled aggregation and gelation [26].

- Directional Freezing: Induces network alignment, creating anisotropic hydrogels with direction-dependent properties that mimic natural tissues [26].

- Cononsolvency-Based Porous Structure Controlling: Leverates the solvent-polymer interactions in mixed solvents to create well-defined porous architectures [26].

These methods exemplify how processing parameters are not merely shaping the material but are actively governing the internal hierarchical structure.

Fabricating Complex 3D Architectures

The final stage in the hierarchical design involves constructing the macro-scale 3D architecture that will interact directly with cells, tissues, or the environment. Advanced additive manufacturing techniques are pivotal for this purpose.

Experimental Protocol: Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP) for 3D Scaffolds

The following detailed methodology is adapted from studies creating 3D test platforms for cell culture [27].

1. Structure Design:

- Objective: To create a 3D grid structure with morphological hierarchy that facilitates easy imaging and analysis of cell-scaffold interactions.

- Design Parameters: The scaffold is based on a unit wall structure (210 µm long, 24 µm tall). The wall is divided into sections of varying widths (10 µm, 30 µm, 50 µm, 70 µm) by perpendicular cross-walls, creating "niches" of different dimensions on both sides. These unit walls are replicated and mirrored to form a long wall (840 µm) where niche sizes gradually increase and then reset.

- Hierarchical Scaling: Multiple parallel walls are fabricated with varying inter-wall distances (e.g., 20, 25, 35, and 55 µm), creating a complex array of chambers with footprints ranging from 200 µm² to 3850 µm². This design incorporates feature sizes from sub-cellular to multi-cellular scales [27].

2. Fabrication via TPP:

- Material: Use a bio-compatible polymer photoresist, such as SZ2080.

- Equipment: A microfabrication laser work station (e.g., Newport µFab system) equipped with a laser source suitable for two-photon absorption.

- Process: The 3D design is directly written into the photoresist using the TPP process. The fabrication uses a Z-slicing of 4 µm between each layer. The stage accuracy is 1 nm in XY and 20 nm in Z, ensuring high dimensional fidelity. The traced lines polymerize into walls with a measured thickness of approximately 2.0 ± 0.2 µm [27].

3. Post-Processing and Cell Seeding:

- Characterization: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to verify the final scaffold dimensions, including wall thickness and niche sizes.

- Sterilization: Sterilize the scaffold using standard methods (e.g., UV light, ethanol rinsing).

- Cell Seeding: Seed the scaffold with an appropriate cell line (e.g., A549 lung epithelial cells). The scaffold's design allows for easy access for fluorescence imaging.

4. Imaging and Analysis:

- Technique: Use confocal fluorescence microscopy with spectral imaging and linear unmixing. This separates the auto-fluorescence from the scaffold material from the fluorescence signal of the cells.

- Analysis: Quantify the volume of cellular material present in different scaffold sections (with different niche sizes and wall separations) to correlate cell distribution and motility with structural parameters [27].

Data-Driven Design and Characterization

The development of hierarchical materials is increasingly supported by computational and data-driven approaches. For instance, Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have been used to model and automate the synthesis of biomass-based plastics, optimizing formulations for properties like water absorption with high accuracy [10]. This integrated approach allows for a more efficient exploration of the vast design space.

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for Hierarchical Biopolymer Materials

| Property Category | Characterization Method | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface topology, porosity, and micro-scale architecture [28]. |

| Confocal Microscopy | 3D internal structure and cell distribution within scaffolds [28] [27]. | |

| Mechanical | Rheological Tests | Viscoelastic properties and gelation kinetics [28]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis | Material stiffness (storage modulus) and damping (loss modulus) under oscillation [28]. | |

| Thermal | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Thermal transitions (e.g., glass transition, melting temperature) [28]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Thermal stability and decomposition profile [28]. | |

| Physicochemical | FTIR Spectroscopy | Chemical composition and molecular interactions [10]. |

| Biodegradability Tests | Rate of material degradation under specific conditions [28]. |

Diagram 1: The logical flow of hierarchical materials design, illustrating the multi-scale progression from molecular sequences to functional applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hierarchical Biopolymer Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SZ2080 Photoresist | A biocompatible inorganic-organic hybrid polymer used for high-resolution 3D structuring via Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP) [27]. | Fabrication of precise 3D cell scaffold structures with hierarchical features for studying cell-material interactions [27]. |

| Recombinant Protein Polymers | Sequentially defined biopolymers (e.g., engineered silk, elastin, collagen) produced via recombinant DNA technology for precise control over sequence and properties [24]. | Creating hydrogels or fibers with tailored mechanical properties and bioactivity for tissue engineering [24]. |

| Supramolecular Crosslinkers | Molecules that form transient, non-covalent bonds (e.g., cyclodextrins, peptide motifs) to create dynamic and self-healing hydrogel networks [26]. | Engineering injectable or stress-relaxing hydrogels for drug delivery or 3D cell culture [26]. |

| Directional Freezing Apparatus | Equipment used to induce unidirectional ice crystal growth, templating the formation of aligned, anisotropic porous structures in hydrogels [26]. | Manufacturing scaffolds that mimic the anisotropic architecture of tissues like cartilage or muscle [26]. |

The journey from monomer sequences to complex 3D architectures represents a fundamental paradigm in advanced biopolymer research. By systematically engineering material structure across every hierarchical level—through integrated sequence design, controlled supramolecular assembly, and precision fabrication—researchers can precisely tailor material properties and functionalities. This holistic, multi-scale approach is essential for developing next-generation biomaterials that meet the complex demands of modern biomedical applications, from targeted drug delivery systems to bio-mimetic tissue scaffolds. The future of the field lies in the continued convergence of computational prediction, synthetic chemistry, and advanced processing technologies, enabling a truly predictive and integrated design process.

From Lab to Clinic: Synthesis Methods and Advanced Biomedical Applications

Biopolymers, derived from renewable biological sources, have garnered significant attention as sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based plastics due to their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and reduced environmental impact [29]. The global biopolymers market is experiencing rapid growth, projected to expand from USD 21.93 billion in 2025 to USD 53.68 billion by 2034, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.46% [4]. This growth is driven by increasing environmental concerns, regulatory pressures against single-use plastics, and advancements in production technologies that enable more efficient and scalable biopolymer manufacturing [30] [4]. Biopolymer synthesis routes can be broadly categorized into chemical, enzymatic, and microbial production methods, each offering distinct advantages for producing materials with tailored properties for applications spanning packaging, biomedical devices, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering [5] [31].

The fundamental building blocks of biopolymers are primarily polysaccharides (such as cellulose, chitin, and alginate), proteins (including collagen and silk fibroin), and polyesters (like polyhydroxyalkanoates) [5] [32]. These materials can be obtained through direct extraction from natural sources (plants, animals, or microorganisms) or produced via controlled synthesis using biological platforms [32]. Traditional extraction methods often require harsh chemicals and extensive downstream processing, whereas microbial and enzymatic synthesis offers a more sustainable alternative with greater control over polymer characteristics such as molecular weight, monomer sequence, and stereochemistry [32]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of these production routes, with detailed methodologies and comparative analysis to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in the field of biopolymer materials.

Microbial Production Routes

Microbial production represents one of the most promising approaches for sustainable biopolymer synthesis, utilizing engineered microorganisms as cell factories to convert simple carbon sources into complex polymeric materials [32]. This route offers several advantages, including higher regio- and stereoselectivity, reduced environmental impact compared to chemical synthesis, and the ability to produce tailored biopolymers with consistent properties without depending on seasonal variations or agricultural land [32].

Native and Engineered Microbial Pathways

Microorganisms naturally produce various biopolymers as storage materials or structural components. For instance, certain bacterial strains synthesize polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) as carbon and energy storage compounds, while others produce exopolysaccharides such as alginate, cellulose, and hyaluronan as part of their extracellular matrix [32]. These native producers can be metabolically engineered to enhance yield, control molecular weight, and modify material properties.

Table 1: Native Microbial Hosts for Biopolymer Production [32]

| Biopolymer | Native Microbial Host | Key Enzymes | Metabolic Precursors | Maximum Reported Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Acetobacter xylinum | Cellulose synthase (BcsA) | UDP-Glc | 15.3 g/L (10L batch) |

| Alginate | Azotobacter vinelandii | Glycosyltransferase (Alg8) | GDP-ManA | 6.6 g/L (1.5L batch reactors) |

| Hyaluronan | C. glutamicum | Hyaluronan synthase (HasA) | UDP-GlcUA + UDP-GlcNAc | 21.6 g/L (5L fed batch) |

| Chitin Oligosaccharides | E. coli (engineered) | Chitin synthase (NodC) | UDP-GlcNAc | 2.5 g/L (2L fed batch) |

For biopolymers not naturally produced by microorganisms, synthetic biology approaches enable the reconstruction of complete biosynthetic pathways in heterologous hosts such as Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum [32]. These engineered platforms benefit from well-established genetic tools, fast growth rates, and extensive knowledge of their metabolic networks. For example, the heterologous expression of Gluconacetobacter xylinus cellulose synthase genes in E. coli has demonstrated the feasibility of producing bacterial cellulose in non-native hosts, though the resulting polymer exhibited amorphous structure and non-native cellulose II morphology, highlighting the importance of host-specific membrane organization for proper crystallization [32].

Metabolic Engineering Strategies

Advanced metabolic engineering is crucial for optimizing microbial biopolymer production. Key strategies include:

- Precursor Supply Enhancement: Increasing the intracellular pool of activated monomeric precursors (e.g., UDP-glucose for cellulose, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine for chitin) by overexpressing enzymes in the precursor biosynthetic pathways and modulating competing metabolic fluxes [32].

- Polymerizing Enzyme Engineering: Optimizing the expression and activity of synthase complexes through codon optimization, promoter engineering, and protein fusion strategies to improve polymerization efficiency and control chain length [30].

- Co-factor Regeneration: Engineering systems for efficient regeneration of essential co-factors such as cyclic di-GMP, which activates bacterial cellulose synthase [32].

- Export and Crystallization Optimization: Coordinating the expression of synthase subunits and accessory proteins (e.g., BcsZ endoglucanase in cellulose production) that facilitate polymer export and crystallization [32].

The following diagram illustrates the general microbial synthesis workflow for polysaccharide-based biopolymers, highlighting the key metabolic engineering interventions:

Experimental Protocol: Microbial Cellulose Production in a Bioreactor

Objective: Produce bacterial cellulose (BC) using Acetobacter xylinum in a controlled bioreactor system to achieve high yields of crystalline cellulose.

Materials:

- Microorganism: Acetobacter xylinum BRC5 (or equivalent strain) [32]

- Culture Medium: Hestrin-Schramm medium containing: 2.0% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, 0.27% disodium phosphate, 0.115% citric acid [32]

- Equipment: 10-Liter bioreactor with temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen control; sterile air supply system; centrifugation equipment; freeze-dryer

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Inoculate a single colony of A. xylinum into 100 mL of sterile medium in a 500 mL flask. Incubate at 30°C for 48 hours with shaking at 120 rpm to achieve active pre-culture.

- Bioreactor Setup and Sterilization: Add 7 L of culture medium to the 10-L bioreactor vessel. Sterilize in situ by autoclaving at 121°C for 20 minutes. After cooling, connect sterile air supply and calibrate pH and dissolved oxygen probes.

- Fermentation Parameters: Set temperature to 30°C. Maintain pH at 5.0 using automatic addition of 1M NaOH or 1M HCl. Maintain dissolved oxygen at 30% saturation by adjusting agitation speed (100-300 rpm) and aeration rate (0.5-1.5 vvm).

- Inoculation and Process Monitoring: Aseptically transfer the 48-hour pre-culture (700 mL, 10% v/v inoculation) to the bioreactor. Monitor bacterial growth by measuring optical density at 600 nm. Track cellulose formation by observing pellicle formation at the air-liquid interface.

- Harvesting: After 120 hours of fermentation, carefully collect the cellulose pellicle from the surface using forceps. For suspended cellulose, centrifuge the culture broth at 8000 × g for 15 minutes to recover cellulose fibers.

- Purification: Resuspend the harvested cellulose in 1% NaOH solution and incubate at 80°C for 2 hours to remove residual cells and medium components. Wash thoroughly with distilled water until neutral pH is achieved.

- Drying: Freeze the purified cellulose at -80°C and lyophilize for 48 hours to obtain dry cellulose membrane or powder.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol can yield up to 15.3 g/L of bacterial cellulose with a production rate of 3.1 g/L/h [32]. The resulting material exhibits high crystallinity and purity suitable for biomedical applications such as wound dressings, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems.

Enzymatic Production Routes

Enzymatic synthesis offers a highly specific and environmentally friendly approach to biopolymer production, utilizing purified enzymes as biocatalysts for in vitro polymerization. This method provides exceptional control over polymer structure, including monomer sequence, stereochemistry, and molecular weight, without the complexity of whole-cell systems [32].

Key Enzymatic Systems

Enzymatic biopolymer synthesis primarily employs transferase enzymes that catalyze the formation of glycosidic, ester, or amide bonds between activated monomer units. Notable examples include:

- Glycosyltransferases: These enzymes transfer sugar moieties from activated donors (e.g., UDP-sugars) to growing polysaccharide chains. For instance, hyaluronan synthase (HasA) catalyzes the alternating addition of UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to form hyaluronan [32].

- Chitin Synthases: Responsible for the polymerization of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine into chitin chains via β-(1,4) linkages [32].

- Cellulose Synthases: Membrane-associated enzyme complexes that processively add glucose units from UDP-glucose to form cellulose microfibrils [32].

- Lipases and Esterases: These can catalyze the polymerization of hydroxyacid esters into polyesters like polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) under mild conditions [30].

Table 2: Key Enzymes for Biopolymer Synthesis [32]

| Enzyme | Biopolymer Product | Monomer Substrates | Reaction Type | Cofactors/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Synthase (BcsA) | Cellulose | UDP-Glucose | β-(1,4) glycosidic bond formation | Cyclic di-GMP activation |

| Hyaluronan Synthase (HasA) | Hyaluronan | UDP-GlcUA + UDP-GlcNAc | Alternating β-(1,4) and β-(1,3) glycosidic bonds | Membrane association |

| Chitin Synthase (NodC) | Chitin | UDP-GlcNAc | β-(1,4) glycosidic bond formation | Metal ions (Mn²⁺, Mg²⁺) |

| Alginate Glycosyltransferase (Alg8) | Alginate | GDP-ManA | β-(1,4) glycosidic bond formation | Membrane complex |

Experimental Protocol: Enzymatic Synthesis of Hyaluronan Using Recombinant Hyaluronan Synthase

Objective: Synthesize hyaluronan with controlled molecular weight using a cell-free enzymatic system containing recombinant hyaluronan synthase.

Materials:

- Enzyme: Recombinant hyaluronan synthase (HasA) expressed and purified from Bacillus subtilis or E. coli [32]

- Substrates: UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GlcUA), UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc)

- Buffer Components: 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Triton X-100