Comparative Analysis of Polymer Degradation Methods: Mechanisms, Applications, and Advancements for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of polymer degradation methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Degradation Methods: Mechanisms, Applications, and Advancements for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of polymer degradation methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It explores the fundamental mechanisms—including thermal, oxidative, hydrolytic, and enzymatic pathways—that govern polymer breakdown. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications in conventional processing, additive manufacturing, and material testing, alongside strategic troubleshooting for optimizing polymer stability and controlled degradation. By critically evaluating and validating analytical techniques from chromatography to spectroscopy, this review serves as a foundational guide for selecting appropriate degradation methods to achieve precise material performance in biomedical applications, from drug delivery systems to implantable devices.

Unraveling Core Mechanisms: A Deep Dive into the Fundamental Pathways of Polymer Degradation

Polymer degradation is defined as a change in the properties—such as tensile strength, color, shape, and molecular weight—of a polymer or polymer-based product under the influence of one or more environmental factors like heat, light, or chemicals [1]. These alterations are primarily due to changes in the polymer's chemical composition and structure, ultimately leading to a decrease in its molecular weight through mechanisms like random or specific chain scission [1]. This process can be undesirable, leading to product failure, or desirable, as in programmed biodegradation or recycling [1]. The susceptibility of a polymer to degradation is heavily influenced by its specific structure; for instance, polymers with aromatic rings are vulnerable to ultraviolet (UV) light, while hydrocarbon-based polymers are more prone to thermal degradation [1].

Understanding these changes is critical for selecting materials in research and development, particularly in fields like drug delivery and sustainable materials, where performance under environmental stress is paramount.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Degradation

The following tables summarize quantitative data on how different polymers and their properties are affected by various degradation conditions, providing a clear, comparative overview for researchers.

Changes in Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed ABS Plus After Accelerated Aging [2]

| Polymer Color | Aging Duration (hours) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Change from Reference (%) | Flexural Strength (MPa or N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow (Reference) | 0 | 33.46 | - | - |

| Blue | 337 | 34.33 | +9.58% | - |

| Green | 225 | 33.54 | +0.23% | - |

| Blue | 450 | 31.38 | -6.22% | - |

| Green | 450 | 30.75 | -8.09% | - |

| Purple | 337 | 24.63 | - | - |

| Red | 450 | - | - | 45.27 N |

Degradation Susceptibility of Common Polymer Types [1]

| Polymer Type/Structure | Primary Degradation Factor | Typical Degradation Mechanism | Key Property Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxies, Aromatic polymers | Ultraviolet (UV) Light | Photo-oxidation | Loss of color, surface cracking, reduced tensile strength |

| Hydrocarbon-based Polymers (e.g., PE, PP) | Heat (Thermal) | Random scission, oxidation | Molecular weight decrease, embrittlement, shape distortion |

| Poly-α-methylstyrene | Heat (Thermal) | Specific chain scission ("unzipping") | Reversion to monomer |

| Polyesters (e.g., PCL, PBSA) | Biological Activity (Enzymatic) | Hydrolysis of ester bonds | Weight loss, reduction in tensile strength, surface erosion |

Comparative Degradability of Biodegradable Polymers in a Marine Environment [3] [4]

| Polymer | Synthesis Method | Key Degrading Enzyme | Primary Degradation Products/Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHBH (e.g., PHBH) | Biological | poly(3HB) depolymerase | Monomers (3-hydroxybutyrate, 3-hydroxyhexanoate) |

| PCL, PBSA, PBAT | Chemical | Lipase, Cutinase | Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC), COâ‚‚ |

| Conventional Plastics (PE, PP, PS) | Chemical | Limited abiotic initiation | Persistent microplastics, slow COâ‚‚ evolution |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Polymer Degradation

Accelerated Aging via Xenon Arc Lamp Weathering

This protocol simulates long-term environmental exposure to sunlight, rain, and dew in a controlled, accelerated manner [2].

- Objective: To investigate the effects of combined light, heat, and moisture on the mechanical and optical properties of polymers.

- Materials: Polymer specimens (e.g., injection-molded or 3D-printed sheets), xenon arc lamp weathering chamber.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer specimens with standardized dimensions according to relevant testing standards (e.g., for tensile, flexural tests).

- Aging Conditions: Expose specimens to continuous light from a xenon arc lamp, which closely mimics the full solar spectrum. Conditions are often set at a specific black standard temperature (e.g., 48°C) and relative humidity (e.g., 50%) [2].

- Duration: Exposure times can vary from hundreds to over a thousand hours, with samples extracted at intervals (e.g., 112, 225, 337, 450 hours) for analysis [2].

- Post-Exposure Analysis:

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile, flexural, and hardness tests on aged and unaged control samples.

- Optical Analysis: Measure color change (ΔE) and gloss retention using spectrophotometers and glossmeters.

- Morphological Inspection: Examine fracture surfaces and micro-cracking using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) [2].

Sequential Abiotic and Biotic Degradation Assay

This comprehensive protocol assesses combined degradation pathways, providing a more realistic environmental fate than biotic tests alone [4].

- Objective: To quantify polymer degradation through both abiotic (non-living) and biotic (microbial) processes, tracking carbon mobilization.

- Materials: Polymer films or powders, simulated seawater, marine microbial inoculum, photoreactor, bioreactors.

- Methodology:

- Abiotic Phase (Photodegradation and Hydrolysis):

- Expose polymer samples to simulated sunlight in a photoreactor while submerged in simulated seawater.

- Monitor the release of Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) from the polymer into the water, a key indicator of abiotic breakdown [4].

- Biotic Phase (Biodegradation):

- Inoculate the photodegraded polymer and its leachate with a defined marine microbial community.

- Monitor multiple endpoints over 28-60 days:

- Abiotic Phase (Photodegradation and Hydrolysis):

- Key Insight: Relying solely on COâ‚‚ measurement (as in standard tests like ASTM 6691-17) can underestimate total degradation by up to two-fold, as it misses carbon converted to biomass and DOC [4].

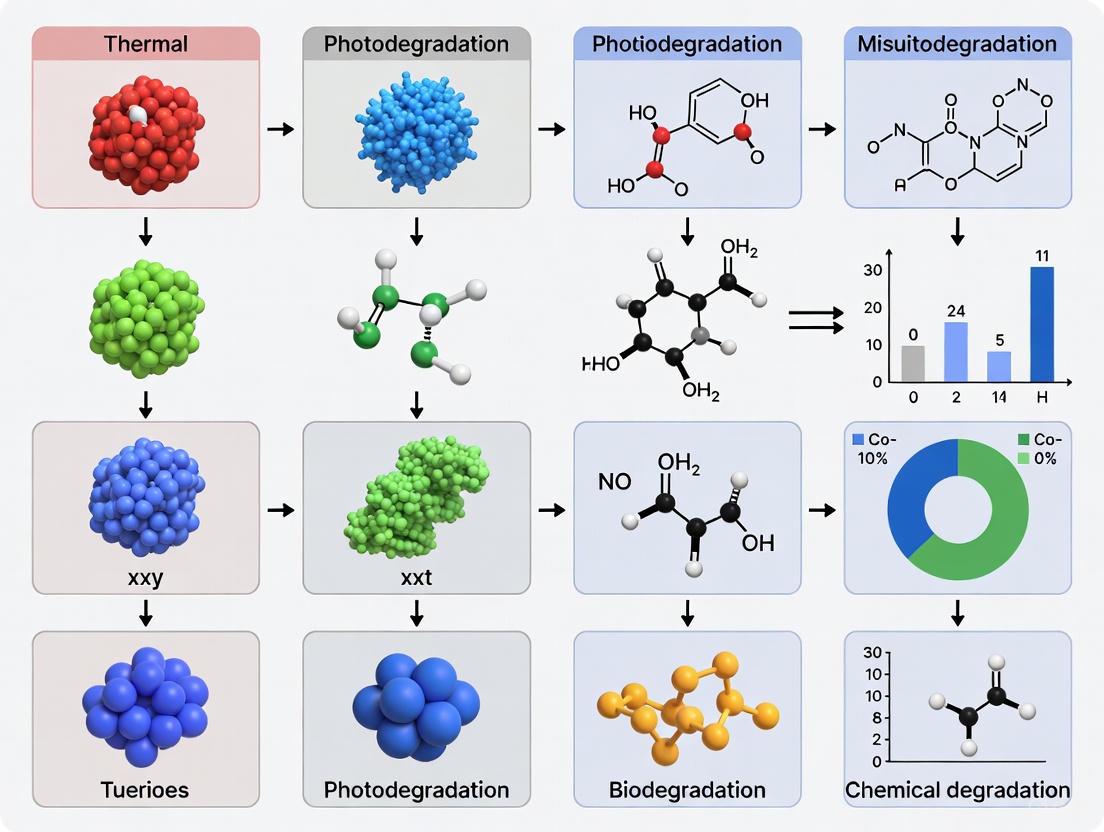

Pathways and Workflows in Polymer Degradation

Autocatalytic Oxidation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the generally accepted autocatalytic cycle of thermal- and photo-oxidative polymer degradation, a key pathway leading to chain scission and loss of properties [1].

Experimental Workflow for Comparative Degradation Analysis

This workflow maps out a integrated approach for comparing the degradation behavior of different polymer materials, from preparation to multi-faceted analysis [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for conducting polymer degradation research.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Xenon Arc Lamp Chamber | Accelerated weathering; simulates full-spectrum sunlight, heat, and moisture to catalyze photodegradation. | Testing weatherability of ABS Plus for outdoor applications; exposure for hundreds of hours simulates years of outdoor use [2]. |

| Marine Microbial Inoculum | Provides a natural consortium of microorganisms for biotic degradation assays in marine-relevant conditions. | Sourced from brackish water or tidal flats; used to test the biodegradability of polymers like PCL, PBSA, and PHBH [3] [4]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer | Detects changes in chemical structure (formation/degradation of functional groups) during oxidation. | Monitoring the growth of carbonyl groups (C=O) at ~1710 cmâ»Â¹, a key indicator of oxidative degradation [1] [5]. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Measures changes in molecular weight and molecular weight distribution, indicating chain scission or cross-linking. | Quantifying the reduction in average molecular weight (Mw) after thermal or photo-oxidative degradation [1]. |

| Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) Analyzer | Quantifies carbon leached from a polymer into solution, a critical metric for abiotic degradation and bioavailable carbon. | Used in sequential abiotic-biotic assays to track carbon mobilization before microbial inoculation [4]. |

| Specific Hydrolases | Enzyme-based degradation; used to probe polymer degradability via specific chemical bonds (e.g., esters). | Lipase and cutinase for chemically synthesized polyesters (PCL, PBSA); poly(3HB) depolymerase for PHAs like PHBH [3]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Visualizes surface topography, cracks, cavities, and biofilm formation on degraded polymer samples. | Examining the fracture surfaces of tensile-tested specimens or microbial colonization on the polymer surface (plastisphere) [5] [2]. |

| UC-781 | UC-781, CAS:178870-32-1, MF:C17H18ClNO2S, MW:335.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Threonyl-seryl-lysine | Threonyl-seryl-lysine|CAS 71730-64-8|RUO | Threonyl-seryl-lysine tripeptide for research. Shown to interact with LHRH, modulating hormonal activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Thermal degradation of polymers refers to the molecular deterioration that occurs at elevated temperatures, typically between 150–200 °C and above, where primary chemical bonds begin to separate [6]. This process fundamentally changes a polymer's properties—including tensile strength, color, and shape—and is a critical consideration for both industrial applications and environmental sustainability [6]. Understanding these mechanisms is particularly vital for researchers and drug development professionals working with polymeric nanoparticles in targeted drug delivery systems, where thermal stability directly impacts shelf life, biocompatibility, and functional integrity [7].

The specific pathway a polymer follows during thermal decomposition depends primarily on its chemical structure and the presence of unstable impurities or additives [6]. Among the several types of degradation, three primary thermal degradation mechanisms dominate: chain depolymerization, random scission, and substituent reactions [6]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to ongoing research in polymer science and pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Analysis of Degradation Mechanisms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, influencing factors, and representative polymers for the three primary thermal degradation mechanisms.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Polymer Thermal Degradation

| Mechanism | Chemical Process Description | Key Influencing Factors | Representative Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain Depolymerization | A "unzipping" process where monomers are successively released from the chain end, often regenerating a high yield of the original monomer. | Stability of the chain-end radical; resonance stabilization of the monomer; steric hindrance. | Poly(methyl methacrylate) [6], Poly(α-methylstyrene) [6], Poly(tetrafluoroethylene) [6]. |

| Random Scission | The polymer backbone breaks at random points along the chain, resulting in a mixture of oligomers and smaller fragments rather than pure monomer. | Bond dissociation energies along the backbone; temperature; presence of catalysts or impurities. | Polyethylene [6], Aliphatic Polyamides (e.g., PA310, PA510) [8]. |

| Substituent Reactions | Side groups (substituents) are cleaved from the polymer backbone, which may or may not cause chain scission. The backbone often cross-links afterward. | Stability of the side-group bond; reactivity of the radical left on the backbone. | Poly(vinyl chloride) [6]. |

The degradation pathway is strongly influenced by the aliphatic chain length. In short-chain polyamides, degradation is often dominated by C–N bond cleavage and cyclization, whereas in long-chain polyamides, reactions like β-CH hydrogen transfer become predominant [8].

Experimental Investigation of Degradation Mechanisms

Key Analytical Techniques and Methodologies

Elucidating thermal degradation mechanisms requires a multi-technique approach that correlates mass loss with chemical and structural changes. The following workflow outlines a standard experimental protocol for a comprehensive analysis.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Thermal Degradation

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): This foundational technique measures the mass change of a sample as a function of temperature or time in a controlled atmosphere. The resulting mass-loss profile is used to determine the degradation temperature and kinetics [8].

- Volatile Product Analysis: Coupling the TGA to a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (TG-FTIR) or a Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (Py/GC–MS) allows for the real-time identification of gases and volatile products released during degradation. This is crucial for deducing the chemical pathways of scission [8].

- Kinetic Analysis: Models like the Kissinger method and the Flynn-Wall-Ozawa method are applied to TGA data obtained at different heating rates to calculate the apparent activation energy (Eâ‚) of the degradation process without assuming a specific reaction model. This helps quantify thermal stability [8].

- Structural Characterization: Techniques like X-ray Diffraction (XRD) track the evolution of crystal structure during heating, revealing phase transitions or loss of crystallinity that accompany degradation [9].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Computational methods like MD can model the behavior of polymer chains under thermal stress at the atomic level, providing insights into initial breakdown events and verifying proposed mechanisms [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Polymer Degradation Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Representative Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymers | Serve as well-defined systems for studying structure-degradation relationships. | Bio-based aliphatic polyamides (PA310, PA510) [8]; Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polyesters [4]. |

| Catalysts / Additives | Can be added to study their effect on degradation kinetics or to simulate industrial formulations. | Ammonium polyphosphate (fire-retardant) [8]. |

| Solvents for Synthesis & Processing | Used in polymer synthesis, purification, and preparation of samples for analysis (e.g., film casting). | N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) for slurry preparation [9]. |

| Characterization Standards | Used for instrument calibration and ensuring data comparability. | Not specified in sources, but universally includes melting point standards, IR calibration films, etc. |

| Inert / Reactive Gases | Create controlled atmospheres (nitrogen for thermal, oxygen for thermo-oxidative degradation) during TGA. | Nitrogen, air [8]. |

| Tideglusib | Tideglusib|GSK-3β Inhibitor|For Research Use | |

| Taltirelin | Taltirelin, CAS:103300-74-9, MF:C17H23N7O5, MW:405.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Experimental Data and Case Studies

Case Study: Bio-based Aliphatic Polyamides

A 2025 study on bio-based polyamides provides excellent quantitative data on how structure influences mechanism and stability [8]. The research successfully synthesized PA310 and PA312 from 1,3-propanediamine and compared them with commercial PA510.

Table 3: Experimental Kinetic Data for Bio-based Polyamides [8]

| Polymer | Activation Energy (Eâ‚) | Degradation Mechanism Notes | Key Volatile Products Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA510 | Highest Eâ‚ | More stable, requiring higher energy for degradation initiation. | Cyclopentanone, hydrocarbons, amines (from chain scission). |

| PA310 | Intermediate Eâ‚ | Higher amide bond density influences pathway. | Similar to PA510, but product distribution varied. |

| PA312 | Lowest Eâ‚ | Less thermally stable under the tested conditions. | Similar to PA510, but product distribution varied. |

Experimental Protocol Summary [8]:

- Synthesis: PA310 and PA312 were synthesized via melt polymerization (MP) followed by solid-state polymerization (SSP) using 1,3-propanediamine and bio-based dicarboxylic acids.

- Characterization: Molecular weight was determined viscometrically. Crystallinity and thermal properties (melting point) were analyzed using techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

- Thermal Degradation Kinetics: TGA was performed at multiple heating rates in a nitrogen atmosphere. The Kissinger and Flynn-Wall-Ozawa methods were applied to the mass-loss data to calculate Eâ‚.

- Mechanism Elucidation: TG-FTIR and Py/GC–MS were used to identify volatile degradation products, enabling the reconstruction of the dominant scission pathways.

Beyond conventional heating, the energy input method can drastically alter the degradation mechanism. A 2025 study on C-phycocyanin (CPC) demonstrated that microwave heating caused more significant degradation and structural changes at lower temperatures and in shorter times compared to conventional water bath heating [10]. This was analyzed using:

- Spectroscopy: Color index, UV-Vis absorbance, fluorescence, and circular dichroism.

- Degradation Kinetics: Modeled with the Weibull model.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Revealed that microwave heating at 55 °C led to increased structural fluctuations and disrupted inter-residue interactions more severely than conventional heating.

This highlights that the "experimental protocol" itself—specifically the heating method—is a critical variable in any comparative study of degradation mechanisms.

The comparative analysis of thermal degradation mechanisms reveals a clear structure-property relationship. The dominant pathway—whether chain depolymerization, random scission, or substituent reaction—is intrinsically linked to the polymer's chemical architecture. For researchers in drug development, understanding these mechanisms is not merely academic. It is essential for:

- Designing Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs): Selecting polymers with known and stable thermal profiles ensures the integrity of the drug delivery system during processing (e.g., sterilization, lyophilization) and storage [7].

- Predicting Product Lifespan: Kinetic parameters like activation energy (Eâ‚) allow for the modeling of long-term stability.

- Developing "Smart" Polymers: Knowledge of degradation triggers (heat, pH) is the foundation for designing stimuli-responsive PNPs that release their payload in a controlled manner at the target site [7].

Future research will continue to leverage the experimental toolkit outlined here—especially the coupling of advanced spectroscopy with computational simulations—to unravel more complex degradation phenomena in next-generation polymeric materials, ultimately enabling more predictive and precise material design for both industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

Oxidative degradation is a fundamental chemical process that dictates the lifetime, stability, and ultimate fate of polymeric materials. At the heart of understanding this phenomenon lies the Bolland and Gee basic autoxidation scheme (BAS), a foundational mechanistic framework derived from studies of rubbers and lipids in the 1940s [11] [12] [6]. This scheme describes a chain reaction process comprising initiation, propagation, and termination steps to explain how polymers degrade in the presence of oxygen, with oxygen-centered radicals playing the central role. For decades, the BAS has served as the universal model for explaining the oxidative degradation of virtually all polymers. Its core premise is that propagation of damage occurs primarily via a hydrogen atom transfer from the polymer chain (RH) to a peroxyl radical (ROO•), generating a hydroperoxide (ROOH) and a new carbon-centered radical (R•) that perpetuates the chain reaction [11] [6].

However, contemporary research has revealed significant limitations and paradoxes within this classical model, particularly when applied to saturated polymers. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the traditional Bolland and Gee framework against emerging alternative mechanisms, supported by current experimental data. It is structured to assist researchers in selecting appropriate analytical protocols and interpreting results within a modernized understanding of polymer degradation.

Critical Comparative Analysis: Classical vs. Modern Paradigms

The following table summarizes the core principles, supporting evidence, and key limitations of the classical autoxidation scheme compared with modern perspectives.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Bolland and Gee Scheme and Modern Degradation Paradigms

| Aspect | Classical Bolland and Gee (BAS) Framework | Modern Perspectives and Alternative Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Core Propagation Mechanism | Relies on hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from polymer (RH) to peroxyl radical (ROO•): ROO• + RH → ROOH + R• [11] [6]. | HAT is thermodynamically disfavored for saturated polymers. Peroxyl radical termination and other pathways may dominate, forming alkoxy radicals that readily undergo chain scission [11]. |

| Role of Polymer Structure | Implicitly treats most polymers similarly, with HAT as the default propagation path [11]. | Polymer structure is critical. Branching and substitution (e.g., tertiary carbons) majorly influence stability and degradation products. Unsaturated defect sites may be primary loci for HAT [11]. |

| Role of Oxygen | Oxygen universally accelerates degradation via perpetual radical chain propagation [11]. | Counterintuitively, oxygen can sometimes slow degradation (e.g., in polyolefins, PMMA), potentially by stabilizing radicals or altering dominant pathways [11]. |

| Key Radical Intermediates | Peroxyl radicals (ROO•) are the primary propagators. Carbon-centered radicals (R•) are precursors to ROO• [12] [6]. | A wider range of radicals is considered significant, including alkoxy radicals (RO•) from termination events and specific carbonyl radicals (•C(O)-) identified via spin trapping [11] [12]. |

| Initiation Sources | Often focuses on thermal or radical initiation. | Expands to include other reactive species: ozone, hydroperoxyl radical, hydroxyl radical, which can initiate hydroperoxide formation without invoking classical peroxyl transfer [11]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Radical Analysis

Validating and differentiating between degradation mechanisms requires sophisticated methodologies capable of detecting and quantifying transient radical species and their products.

Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) Spin Trapping

This technique is essential for direct observation of short-lived radical intermediates, overcoming the limitation of their transient nature [12].

- Objective: To directly identify and characterize short-lived free radicals (e.g., alkyl, alkoxy, peroxyl) generated during the thermo-oxidative degradation of polymers.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Antioxidant-free polymer granules (e.g., polypropylene) are used. A spin-trapping reagent (e.g., TTBNB) is uniformly impregnated into the polymer matrix using a swelling method with supercritical COâ‚‚ to ensure deep penetration [12].

- Oxidative Aging: Samples are subjected to controlled thermo-oxidative aging (e.g., 90°C under 100 mL/min oxygen flow for 1000 hours) [12].

- Radical Generation & Trapping: During thermal treatment, generated short-lived radicals (•R) react with the spin trap (ST) to form a stable, detectable spin adduct (ST-•R).

- ESR Measurement: The ESR spectrum of the spin adduct is recorded. The hyperfine coupling constants (hfcc) of the spectrum are analyzed to identify the molecular structure of the original trapped radical [12].

- Key Data Output: Identification of specific radical types. For instance, studies on oxidized PP have detected carbonyl radicals (•C(O)-), whose concentration is highest in homopolymers, indicating higher susceptibility to oxygen attack compared to copolymers [12].

Chemiluminescence (CL) Analysis

CL is a highly sensitive method for monitoring the early stages of oxidation, particularly the formation and decomposition of hydroperoxides [13].

- Objective: To track the kinetics of oxidation in real-time by measuring the light emission associated with radical termination reactions.

- Protocol:

- Sample Setup: Polymer samples (e.g., powder, film) are placed in a heated chamber under a controlled atmosphere (oxygen or nitrogen) [13].

- Temperature Programming: Experiments can be run in either isothermal (constant temperature) or non-isothermal (ramped temperature) modes. A common range is 40–220°C [13].

- Light Detection: A photomultiplier tube detects the weak light (chemiluminescence) emitted when two peroxyl radicals terminate (ROO• + ROO• → products + hν) [13].

- Data Interpretation: The induction time to a rapid autoaccelerating increase in CL intensity and the maximum intensity are correlated with the material's oxidative stability. The presence of antioxidants shifts the induction time to longer durations [13].

- Key Data Output: CL-intensity vs. time/temperature curves that provide information on oxidation induction time and rate.

Cryogenic EPR for Radical Quantification

This specialized EPR approach is used to probe the radical landscape in aged materials, particularly for lifetime prediction in critical applications [14].

- Objective: To quantify and characterize stable and trapped radicals in aged polymer samples as a measure of aging degree and antioxidant efficacy.

- Protocol:

- Aging and Sampling: Polymer materials (e.g., cross-linked polyethylene for cable insulation) are subjected to gamma radiation aging at different dose rates.

- Probe Irradiation: Aged samples are frozen in liquid nitrogen and uniformly irradiated with a low dose of gamma radiation. This "probe" radiation generates a new, measurable population of radicals whose type and stability are influenced by the material's prior aging history.

- Cryogenic EPR Measurement: EPR spectra are acquired at low temperatures (e.g., 100 K) and then at stepwise increasing temperatures to monitor radical recombination kinetics.

- Radical Identification: Spectra are deconvoluted to quantify the relative concentrations of alkyl (Alk•) and peroxyl (POO•) radicals [14].

- Key Data Output: Ratios of peroxy-to-alkyl radicals and their decay kinetics, which serve as indicators of the material's aging state and the depletion level of its antioxidants [14].

Visualization of Key Degradation Pathways and Workflows

The Basic Autoxidation Scheme and Modern Extensions

This diagram illustrates the core steps of the classical Bolland-Gee scheme and integrates key modern modifications, such as alternative termination pathways and the role of alkoxy radicals.

Experimental Workflow for Radical Identification

This flowchart outlines the integrated experimental workflow for analyzing radical intermediates using ESR spin trapping and chemiluminescence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments critical for conducting research on oxidative degradation pathways.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxidative Degradation Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant-Free Polymer Granules | Provides a baseline material free of interfering stabilizers, allowing study of the pure polymer's degradation mechanism. | Isotactic PP homopolymer, random copolymer, block copolymer [12]. |

| Spin Trapping Reagents | Compounds that react with short-lived radicals to form stable, detectable spin adducts for ESR analysis. | TTBNB; impregnated into polymer matrix using supercritical COâ‚‚ [12]. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ System | Used as a swelling medium to deeply and uniformly impregnate spin traps or other reagents into the polymer matrix. | Ensures homogeneous distribution of the spin trap throughout the sample [12]. |

| Chemiluminescence Apparatus | Instrument to measure the weak light emission from termination reactions during oxidation; used for determining oxidative induction time. | Can be operated in isothermal or temperature-ramp modes [13]. |

| Cryogenic EPR Setup | System for low-temperature EPR measurements, essential for stabilizing and studying transient radical species generated by probe irradiation. | Used to track radical recombination kinetics from 100 K to room temperature [14]. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Oven | For subjecting polymer samples to precise thermo-oxidative aging conditions (temperature, gas environment, duration). | E.g., 90°C under 100 mL/min O₂ flow for 1000 hours [12]. |

| Organic Catalysts (for Degradation Studies) | Potent catalysts used in studies of chemical recycling via degradation, highlighting the lability of certain bonds. | 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) catalyzes polyester and polycarbonate degradation [15]. |

| Tas-301 | Tas-301, CAS:193620-69-8, MF:C23H19NO3, MW:357.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lck Inhibitor | Lck Inhibitor, MF:C31H30N8O, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Bolland and Gee basic autoxidation scheme remains a foundational model for understanding polymer oxidation. However, contemporary research underscores that it is not universally applicable. The dominant degradation pathways are highly dependent on polymer structure, with termination reactions and alkoxy radical chemistry competing effectively with the classical propagation via hydrogen transfer in many saturated systems. For researchers, this necessitates a critical approach: mechanistic models must be chosen and applied with consideration of the specific polymer chemistry. Advanced techniques like ESR spin trapping and chemiluminescence provide the necessary experimental data to move beyond assumptions and build accurate, material-specific degradation models that are crucial for developing stable polymers or efficient recycling strategies.

Biodegradable polyesters, such as Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), represent a promising sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics. Understanding their degradation mechanisms is paramount for applications ranging from drug delivery systems to environmental remediation [16]. The end-of-life fate of these materials is primarily governed by two key processes: hydrolytic degradation, which is an abiotic chemical process, and enzymatic degradation, which is mediated by microorganisms [17] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the degradation profiles of PLA and PHA, underpinned by experimental data and protocols, to inform researchers and scientists in the field of polymer science and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Degradation Mechanisms

The biodegradation of polymers is a complex process initiated by the breakdown of large polymer chains into smaller fragments, which are subsequently assimilated by microorganisms [16]. For biodegradable polyesters like PLA and PHA, this process predominantly occurs through the scission of ester bonds in their backbone [17] [18]. While both polymers are susceptible to hydrolysis and enzymatic attack, the primary pathways, responsible enzymes, and degradation kinetics differ significantly due to their distinct chemical origins and physical structures.

PLA, a synthetic polyester derived from renewable resources like corn, undergoes degradation mainly via chemical hydrolysis in aqueous environments, which can be accelerated by temperature [18]. Its enzymatic degradation is more specific and is facilitated by enzymes such as proteases, lipases, cutinases, and esterases secreted by microorganisms [19]. Notably, PLA-degrading enzymes are categorized into two types: Type I (protease-based), which is specific to PLLA, and Type II (lipase/cutinase-based), which shows a preference for PDLA [18]. A critical challenge with PLA is its resistance to degradation in many natural environments, such as freshwater and seawater at low temperatures, due to its hydrophobic nature and the low prevalence of active depolymerizing enzymes in these settings [18] [20]. Its degradation is highly dependent on environmental conditions and material properties, such as crystallinity—amorphous regions degrade more readily than crystalline ones [18].

In contrast, PHA is a natural polyester accumulated as an energy reserve by various microorganisms [21]. Its degradation is predominantly enzymatic, driven by extracellular PHA depolymerases secreted by a wide range of bacteria and fungi found in diverse ecosystems [21]. These enzymes are highly effective and allow PHA to be more readily biodegradable in natural environments, including soil, freshwater, and marine systems, compared to PLA [20]. PHA degradation is influenced by polymer composition, crystallinity, and the presence of specific microbial communities [21].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of PLA and PHA Degradation Profiles

| Characteristic | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Degradation Mechanism | Chemical hydrolysis (abiotic), followed by enzymatic attack [18]. | Primarily enzymatic hydrolysis via microbial depolymerases [21]. |

| Key Enzymes Involved | Proteases, lipases, cutinases, esterases (Type I & II depolymerases) [19] [18]. | Extracellular PHA-specific depolymerases [21]. |

| Typical Degradation Environments | Industrial compost, soil, wastewater; slow in freshwater/seawater [18] [20]. | Soil, compost, marine and freshwater environments, activated sludge [21]. |

| Influence of Crystallinity | High crystallinity slows degradation; amorphous regions degrade first [19] [18]. | High crystallinity (e.g., in PHB) can slow degradation; copolymers like PHBV degrade faster [21]. |

| Representative Degradation Products | Lactic acid monomers, oligomers, micro/nanoplastics [20]. | Hydroxyalkanoate monomers/oligomers, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O [21]. |

| Relative Degradation Rate in Compost | Fast (can degrade within months under industrial composting) [18]. | Fast to Very Fast (depending on copolymer composition) [21]. |

Table 2: Key Microbial Strains and Their Associated Degrading Enzymes

| Polymer | Source of Degrading Microbes/Enzymes | Key Microbial Genera / Enzyme Types |

|---|---|---|

| PLA | Actinomycetes, bacteria, fungi [18]. | Actinomycetes, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Streptomyces, Rhodococcus, Amycolatopsis; Proteases, Lipases, Cutinases [19] [18]. |

| PHA | Soil, sludge, freshwater, marine habitats, extreme environments [21]. | Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Cupriavidus, Alcaligenes, Comamonas, Acidovorax; PHA Depolymerases [21]. |

Visualizing the Degradation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the parallel hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation pathways for PLA and PHA, highlighting the key steps and differences in their breakdown processes.

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Assessment

A comprehensive assessment of polymer degradation requires a multi-faceted approach, evaluating physical, chemical, and mechanical property changes over time. The following protocols outline standardized methods for in vitro degradation studies.

Gravimetric Analysis (Mass Loss)

This is a fundamental method for tracking the physical erosion of a polymer sample.

- Principle: Measure the mass loss of a polymer sample after immersion in a degradation medium over time [22].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer films or specimens with known dimensions (e.g., 10 mm x 10 mm x 0.5 mm). Dry in a vacuum desiccator until a constant initial dry mass (Mâ‚€) is achieved.

- Immersion: Incubate samples in a degradation medium (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, 37°C, or specific enzyme solutions) under sterile conditions [22].

- Sampling: At predetermined time points, remove samples from the medium (in triplicate), rinse gently with deionized water, and dry again to a constant weight (Mₜ).

- Calculation: Determine the remaining mass percentage using the formula: > Remaining Mass (%) = (Mₜ / M₀) × 100 [22].

Molecular Weight Determination via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

This technique monitors the chemical degradation of the polymer backbone by tracking the reduction in molecular weight, which often precedes measurable mass loss [23].

- Principle: Also known as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), GPC separates polymer molecules by their hydrodynamic volume, providing data on the average molecular weight (Mâ‚™, Mð„¯) and polydispersity index (PDI) [23] [22].

- Procedure:

- Pre-degradation Baseline: Analyze the molecular weight of the initial, undegraded polymer sample.

- Post-degradation Analysis: At selected time points, retrieve samples from the degradation study, dry them, and dissolve them in a suitable chromatographic solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran for PLA and PHA).

- Chromatography: Pass the filtered solution through a GPC system equipped with a refractive index detector. Compare the retention times against a calibration curve built with polymer standards of known molecular weights [23].

- Data Interpretation: A steady decrease in molecular weight over time indicates bulk hydrolysis of the polymer's ester bonds.

Enzymatic Degradation Assay

This protocol specifically quantifies the enzymatic susceptibility of a polymer.

- Principle: Measure the rate of polymer breakdown in the presence of a specific, purified enzyme, often by monitoring the release of soluble degradation products [19].

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a solution of the target enzyme (e.g., Proteinase K for PLA or a PHA depolymerase for PHA) in an appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). The enzyme solution should be filtered sterilized.

- Incubation: Add a known mass of polymer film or powder to the enzyme solution. Maintain under optimal temperature and agitation conditions for the enzyme (e.g., 37°C for Proteinase K). A control without the enzyme must be run in parallel.

- Quantification:

- Method A (UV-Vis): Periodically, withdraw aliquots from the supernatant and measure the concentration of soluble peptides/oligomers using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., at 280 nm for aromatic residues) or via the Lowry/BCA assay [5].

- Method B (Titration): For polymers that release acidic monomers (like lactic acid from PLA), the degradation can be tracked by titrating the acid released or by monitoring a pH stat [19].

- Analysis: The rate of product formation is directly proportional to the enzymatic activity on the polymer substrate.

Table 3: Summary of Key Analytical Techniques for Degradation Assessment

| Technique | Parameter Measured | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Analysis | Mass loss / Surface erosion [22]. | Quantifies physical disintegration of solid samples. | Simple, cost-effective, provides direct evidence of material loss. | Cannot detect initial bulk hydrolysis; mass loss may be mistaken for dissolution [22]. |

| GPC / SEC | Molecular weight distribution [23] [22]. | Tracks chain scission and chemical degradation in the polymer bulk. | Highly sensitive to early-stage degradation; provides quantitative Mâ‚™, Mð„¯ data. | Requires soluble samples; specialized, costly equipment [22]. |

| SEM | Surface morphology and erosion [23] [5]. | Visualizes physical changes, cracks, pits, and microbial colonization on the surface. | Provides direct visual evidence of degradation; high resolution. | Qualitative; sample preparation can be destructive; infers but does not confirm degradation [22]. |

| HPLC / GC-MS | Identification and quantification of monomers/oligomers [22] [20]. | Chemical analysis of degradation products in the surrounding medium. | Highly specific and sensitive; can identify toxic leachates. | Requires method development; long analysis times; expensive [5]. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Changes in chemical functional groups [23]. | Identifies chemical changes on the polymer surface (e.g., ester bond reduction). | Rapid, non-destructive; can be used for solid and liquid samples. | Less sensitive than chromatographic methods; can be semi-quantitative. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in polymer degradation requires specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table lists key items and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Samples | The subject of degradation studies; available in various forms (film, powder, scaffold). | PLA (PLLA, PDLA), PHA (PHB, PHBV) [19] [21]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintain a stable pH in degradation media to simulate physiological or environmental conditions. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Tris-HCl Buffer [22]. |

| Purified Enzymes | To study specific enzymatic degradation pathways and kinetics. | Proteinase K (for PLA), PHA Depolymerases, Lipases, Cutinases [19] [21] [18]. |

| Chromatographic Solvents | To dissolve polymers for molecular weight analysis via GPC. | High-purity Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Chloroform [23]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | To calibrate GPC systems for accurate molecular weight determination. | Narrow-dispersity Polystyrene (PS) or Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) standards [23]. |

| Simulated Body Fluids (SBF) | To test biodegradation and bioabsorption of materials for biomedical applications. | Kokubo's SBF recipe [17]. |

| Microbial Strains | To investigate biotic degradation under more complex, environmentally relevant conditions. | Pseudomonas sp., Bacillus sp., Streptomyces sp. [21] [18]. |

| Tolciclate | Tolciclate, CAS:50838-36-3, MF:C20H21NOS, MW:323.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tolclofos-methyl | Tolclofos-methyl|Broad-Spectrum Fungicide|RUO | Tolclofos-methyl is a broad-spectrum systemic fungicide for research use only (RUO). It controls soil and seed-borne fungal pathogens. Not for human or personal use. |

The Impact of Polymer Structure and Bond Dissociation Energies on Stability

The stability of polymers is a fundamental property that dictates their application, processing, and lifespan. This stability is intrinsically governed by the strength of the chemical bonds within their structure, quantified by bond dissociation energies (BDEs). Understanding the relationship between polymer structure, BDE, and stability is crucial for researchers and scientists developing new materials, especially in demanding fields like drug delivery and high-performance composites. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different polymer structures and their associated BDEs influence stability against thermal, chemical, and environmental degradation, equipping professionals with the data and methodologies to make informed material selections.

Fundamental Principles: Bond Dissociation Energy and Radical Stability

Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) is the energy required to break a chemical bond homolytically, resulting in two neutral free radicals. As such, it serves as a direct measure of bond strength. A critical principle is the inverse relationship between BDE and the stability of the generated radicals: a lower BDE often indicates that the resulting free radicals are more stable [24].

Several structural factors influence radical stability and, consequently, BDE:

- Substitution Level: Radical stability increases in the order methyl < primary < secondary < tertiary, leading to a decrease in C–H BDE [24].

- Resonance: Conjugation significantly stabilizes radicals, substantially lowering BDE. For example, a primary C–H bond adjacent to two alkenes (doubly allylic) has a BDE as low as 76 kcal/mol due to extensive resonance delocalization [24].

- Adjacent Atoms: Atoms with lone pairs can stabilize an adjacent radical, while increasing electronegativity destabilizes radicals, resulting in higher BDEs (e.g., H–F BDE is 136 kcal/mol) [24].

- Hybridization: Bonds to atoms with higher s-character (e.g., sp-hybridized carbons in acetylene) have higher BDEs because the orbital is held closer to the nucleus [24].

Table 1: Bond Dissociation Energies (BDEs) and Influencing Factors

| Bond Type | Example Molecule | BDE (kcal/mol) | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| C–H (Methyl) | H–CH₃ | 104 | Reference value |

| C–H (Primary) | H–CH₂CH₃ | 98 | Substitution level |

| C–H (Tertiary) | H–C(CH₃)₃ | 96 | Substitution level |

| C–H (Allylic) | H–CH₂CH=CH₂ | 88 | Resonance stabilization |

| C–H (Doubly Allylic) | H–CH(CH=CH₂)₂ | 76 | Enhanced resonance |

| O–H | H–OH | 119 | High electronegativity of O |

| C–H (sp²) | H–CH=CH₂ | 109 | sp² Hybridization |

| Disulfide | R–S–S–R | ~60 [25] | Dynamic covalent bond |

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Stability

Thermal Stability of Fluorinated Polymers

Fluorinated polymers are benchmarks for thermal stability. The high strength of the carbon-fluorine (C–F) bond places polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) at the performance top, with a continuous service temperature of 260°C [26]. The thermal stability of linear vinyl polymers is closely related to the BDE of the backbone carbon-carbon (C–C) bond. Studies using model compounds and thermodynamic cycles show PTFE has a C–C bond strength 30–40 kJ/mol higher than polyethylene (PE) [26].

The stability trend based on weight loss during thermal degradation is: PTFE > ETFE > PVDF ≈ PE > ECTFE > PCTFE [26]. This hierarchy can be attributed to the bond energies and the susceptibility to elimination reactions. Partially fluorinated polymers like PVDF and ECTFE are prone to HF and HCl elimination, respectively, which lowers their relative thermal stability compared to PTFE [26].

Table 2: Comparative Thermal Stability of Select Polymers

| Polymer | Full Name | Key Bonds in Backbone | Relative Thermal Stability (Weight Loss) | Notable Degradation Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene | C–C, C–F | Highest | Depolymerization at high T |

| ETFE | Ethylene-Tetrafluoroethylene Alternating Copolymer | C–C, C–F, C–H | High | Complete depolymerization |

| PE | Polyethylene | C–C, C–H | Medium | Chain scission |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Fluoride | C–C, C–F, C–H | Medium | HF elimination |

| ECTFE | Ethylene-Chlorotrifluoroethylene Alternating Copolymer | C–C, C–F, C–H, C–Cl | Lower | HCl elimination |

| PCTFE | Polychlorotrifluoroethylene | C–C, C–F, C–Cl | Lowest | HCl elimination |

Susceptibility to Different Degradation Methods

Different degradation technologies target bonds with specific energies and chemistries. Condensation polymers are often more amenable to chemical recycling than polyolefins because ester bond cleavage is energetically more favorable than C–C bond cleavage [15].

- Organocatalyzed Degradation: Organic catalysts like 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) are highly effective in degrading condensation polymers (e.g., polyesters, polycarbonates) via transesterification. TBD operates through a dual hydrogen-bonding mechanism, activating both the ester carbonyl and the hydroxyl group of the nucleophile (e.g., alcohol) [15].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Enzymes break down polymers through specific biochemical pathways. Hydrolases target ester bonds in polyesters via hydrolysis, inserting water molecules to break polymer chains into monomers. Oxidoreductases break down hydrocarbon-based plastics like polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) by oxidizing strong carbon-carbon bonds [27].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between polymer structure, bond energy, and its susceptibility to various degradation methods.

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Thermal Stability

Objective: To evaluate the thermal stability and decomposition profile of a polymer by measuring its mass change as a function of temperature under a controlled atmosphere [26].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-20 mg of the polymer sample into a pristine TGA crucible.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample into the TGA and purge the furnace with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) at a flow rate of 50-100 mL/min to create an oxygen-free environment.

- Temperature Program: Heat the sample from room temperature to a high temperature (e.g., 800°C) at a constant heating rate (e.g., 10°C/min).

- Data Collection: Continuously record the mass (or percentage mass loss) and temperature. The first derivative of the TGA curve (DTG) can be calculated to identify precise decomposition temperatures.

- Data Analysis: Determine key parameters from the TGA curve:

- Onset Decomposition Temperature (Tₒₙₛₑₜ): The temperature at which decomposition begins, often identified by the intersection of tangents.

- Midpoint Decomposition Temperature (Tₘᵢð’¹): The temperature at which 50% mass loss occurs.

- Char Yield: The percentage of residual mass at the final temperature.

Protocol: Investigating Pre-polymerization Interactions via Computational and Experimental Methods

Objective: To rationally design molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) by screening functional monomers based on their interaction energy with a template molecule, thereby improving imprinting efficiency [28].

Methodology:

- Quantum Chemical (QC) Calculations:

- Structure Optimization: Use computational software (e.g., Gaussian) to optimize the geometry of the template and potential functional monomers at a level like B3LYP/6-31G(d).

- Interaction Energy Calculation: Model the 1:1 template–monomer complex. Calculate the binding energy (ΔEbind) in vacuum using the formula: ΔEbind = E(complex) - [E(template) + E(monomer)]. More negative ΔEbind values indicate stronger interactions [28].

- Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis: Perform NBO analysis to examine the charge characteristics of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors [28].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- System Setup: Simulate a pre-polymerization system containing the template, functional monomer, crosslinker, and solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) in an explicit solvent model.

- Quantitative Parameter Definition: Analyze the simulation trajectories to define parameters like the Effective Binding Number (EBN) and maximum Hydrogen Bond Number (HBNMax). Higher values indicate higher effective binding efficiency between the template and monomer [28].

- Experimental Validation:

- Polymer Synthesis: Prepare MIPs based on the optimal monomer identified from simulations, typically using surface-initiated polymerization techniques.

- Adsorption Tests: Evaluate the binding capacity and selectivity of the synthesized MIPs to validate the computational predictions [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key reagents and materials used in the experimental protocols and research areas discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Diphenylphosphate (DPP) | Brønsted acid catalyst for controlled ring-opening polymerization of disulfide-containing lactones, offering remarkable tolerance to disulfide bonds [25]. | Synthesis of poly(disulfide)s with narrow molecular weight distributions (PDI < 1.1) [25]. |

| 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) | Organocatalyst for the degradation and chemical recycling of condensation polymers via a dual hydrogen-bonding activation mechanism [15]. | Glycolysis of PET to bis(hydroxyethyl)terephthalate (BHET) [15]. |

| PETase Enzyme | Hydrolase enzyme that specifically targets and cleaves ester bonds in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) via hydrolysis [27]. | Enzymatic depolymerization of PET waste at ambient conditions [27]. |

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | Functional monomer for Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs); carboxylic acid group forms strong interactions with template molecules [28]. | Pre-polymerization complex with sulfadimethoxine (SDM) for MIP development [28]. |

| Benzyl Alcohol (BnOH) | Initiator for controlled lactone ring-opening polymerization [25]. | Initiation of 1,4,5-oxadithiepan-2-one (OTP) polymerization to produce well-defined poly(disulfide)s [25]. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Nucleophile (diol) for glycolysis reactions in polymer degradation [15]. | Solvent and reactant for organocatalyzed degradation of PET [15]. |

| Tomatine | Tomatine (α-Tomatine) - CAS 17406-45-0 - For Research Use | |

| Telomycin | Telomycin, CAS:19246-24-3, MF:C59H77N13O19, MW:1272.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Theory-Guided Machine Learning (TGML) for Property Prediction

A emerging approach to predict mechanical properties like tensile strength across different temperatures and strain rates is Theory-Guided Machine Learning (TGML). This framework integrates physically-based strength theoretical models with machine learning algorithms (e.g., Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) [29]. TGML offers superior performance under small-sample conditions, enhanced prediction accuracy, and better generalizability compared to purely data-driven black-box models by incorporating fundamental physical principles [29].

Analytical Techniques for Polymer Aging

Understanding long-term stability requires advanced analytical techniques to study polymer aging. Key methods include [30]:

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): Tracks changes in molecular weight distribution, revealing chain scission or cross-linking.

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies formation or disappearance of functional groups, providing a chemical fingerprint of degradation.

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) Spectroscopy: Detects and quantifies free radicals that drive oxidative degradation.

- Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS): Analyzes polymer breakdown products and migrating additives.

The integration of these methods provides a comprehensive view of degradation mechanisms, moving beyond single-metric assessments [30]. Furthermore, machine learning is emerging as a tool to process complex datasets from these techniques to build predictive models of polymer lifespan [30].

The stability of polymers is an intricate property directly derived from their molecular structure and the bond dissociation energies of their constituent bonds. This comparative guide demonstrates that while strong C–F and C–C bonds impart high thermal stability, as seen in PTFE, they can make polymers recalcitrant to recycling. Conversely, polymers with lower BDE bonds, such as esters and disulfides, offer pathways for controlled degradation and recycling, which is crucial for a circular economy. The choice of polymer for any application, particularly in drug development and high-tech industries, must therefore balance the need for operational stability with end-of-life considerations. The experimental protocols and advanced analytical techniques outlined provide a foundation for researchers to systematically evaluate and engineer polymers with tailored stability profiles.

From Theory to Practice: Analytical Methods and Applications in Processing and Biomedicine

Chromatographic techniques are indispensable tools for characterizing polymers and their degradation products. For researchers investigating polymer degradation, two techniques are paramount: Gas Chromatography (GC) for determining the composition of low-molecular-weight additives, residual monomers, and degradation volatiles, and Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) / Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for measuring the molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of polymer chains. The selection between these methods is dictated by the analytical goal: GC is optimal for separating and identifying volatile and semi-volatile compounds within a polymer matrix, providing a detailed picture of its chemical composition. In contrast, SEC/GPC separates dissolved polymer molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume in solution, directly yielding the molecular weight distribution, a parameter critically sensitive to chain scission and cross-linking events during degradation. A thorough comparative analysis of these techniques provides scientists with a foundational framework for selecting the optimal methodology to monitor chemical and physical changes throughout the polymer lifecycle, from formulation and processing to aging and environmental breakdown.

Comparative Analysis: GC vs. SEC/GPC

The following table provides a direct comparison of the core characteristics, applications, and outputs of GC and SEC/GPC, highlighting their complementary roles in polymer analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of GC and SEC/GPC for Polymer Characterization

| Feature | Gas Chromatography (GC) | Size Exclusion Chromatography/Gel Permeation Chromatography (SEC/GPC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Analytical Focus | Composition and purity of low-molecular-weight components [31]. | Molecular weight (MW) and molecular weight distribution (MWD) of polymers [32] [33]. |

| Separation Principle | Volatility and partitioning between a mobile gas phase and a stationary liquid phase [34]. | Hydrodynamic volume (size in solution) [35] [32]. |

| Ideal Analytes | Volatile and semi-volatile compounds: plasticizers (e.g., DOA), stabilizers (e.g., PBNA), residual monomers, solvents, and degradation volatiles [31] [34]. | Soluble macromolecules: synthetic polymers, proteins, and other large molecules [32] [33]. |

| Key Measured Outputs | Retention time, peak area/height for identification and quantification [31]. | Elution volume, which is calibrated to molecular weight; intrinsic viscosity [35] [32]. |

| Typical Detectors | Flame Ionization (FID), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Thermal Conductivity (TCD) [36]. | Refractive Index (RI), Light Scattering (LS), Viscometer [32] [33]. |

| Role in Degradation Studies | Identifies and quantifies small molecules leached, emitted, or formed during degradation [34]. | Tracks changes in average MW (Mn, Mw) and MWD, indicating chain scission or cross-linking [33]. |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires extraction, headspace sampling, or derivatization to increase volatility [34]. | Requires complete dissolution in an appropriate solvent [35] [33]. |

Advanced Detection and Data Interpretation

Modern chromatographic analysis extends beyond simple separation, leveraging advanced detection systems to provide deeper structural insights. In SEC/GPC, the use of a triple-detector array (refractive index, light scattering, and viscometer) has become a powerful tool. This combination allows for the determination of absolute molecular weight without reliance on column calibration standards, while also providing information on molecular conformation, branching density, and intrinsic viscosity [32]. The Mark-Houwink plot, which graphs intrinsic viscosity against molecular weight, is a key output from such a system; deviations from a linear trend can clearly reveal the presence of branching in a polymer, a structural feature that significantly influences degradation behavior and mechanical properties [32].

For GC, coupling to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is the gold standard for unambiguous identification of unknown compounds in complex mixtures, such as degradation products or impurities. Furthermore, comprehensive two-dimensional GC (GC×GC) greatly enhances the separation power and peak capacity, making it invaluable for characterizing complex samples like packaging volatiles that migrate into food, thereby providing a detailed fingerprint of a material's composition and its interactions with the environment [34].

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Characterization

Protocol 1: GC Analysis of Organic Additives in a Polymer Matrix

This protocol, adapted from a study on solid propellant ingredients, outlines a unified GC method for analyzing multiple organic additives—such as plasticizers, curing agents, and stabilizers—in a single run [31].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Weigh approximately 20-50 mg of the polymer sample. For solid polymers, cryo-grind the material to a fine powder to increase surface area. Extract the organic additives using a suitable solvent (e.g., acetonitrile for analytes like dioctyl adipate (DOA) and phenyl-2-naphthylamine (PBNA)) in an ultrasonic bath for 30-60 minutes [31]. Filter the extract through a 0.45 µm syringe filter to remove any particulate matter.

- 2. Instrumental Conditions:

- GC System: Configured with a split/splitless inlet and a flame ionization detector (FID) or mass spectrometer (MS).

- Column: Use a 100% poly-dimethyl siloxane (GSBP-1 or equivalent) capillary column (e.g., 30 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness) for broad-range separation [31].

- Temperature Program: Employ a ramped oven temperature. An example program is: initial temperature 60°C, hold for 2 minutes; ramp at 10°C/min to 300°C; hold for 10 minutes [31].

- Carrier Gas: Helium or hydrogen, at a constant linear velocity (e.g., 1.0 mL/min).

- Injection: Split mode (e.g., 10:1 split ratio) with a 1 µL injection volume.

- 3. Calibration and Quantification: Prepare a series of calibration standards with known concentrations of the target analytes (e.g., DOA, TDI, PBNA). Inject these standards to establish a linear calibration curve (peak area vs. concentration). The correlation coefficient (R²) should be >0.995 for accurate quantification [31].

- 4. Data Analysis: Identify compounds based on their retention times compared to standards. Quantify using the established calibration curves. Report the concentration of each additive as a percentage (%) in the original polymer sample, along with the relative standard deviation (RSD) for repeatability [31].

Protocol 2: SEC/GPC for Absolute Molecular Weight and Branching Analysis

This protocol details the use of a triple-detection SEC/GPC system to obtain absolute molecular weight data and characterize polymer branching, which is critical for understanding degradation mechanisms [32].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 2-10 mg of polymer into a vial. Add a known mass of solvent (e.g., Tetrahydrofuran, THF, for synthetic polymers) to achieve a target concentration. The ideal concentration is dependent on the polymer's molecular weight and dispersity; broadly distributed samples can tolerate higher concentrations (e.g., 2-4 mg/mL), while high-MW or narrowly distributed samples require lower concentrations (e.g., 1 mg/mL) to avoid undesirable "overloading" effects that distort peak shape and elution volume [35]. Stir or agitate gently until fully dissolved, which may take several hours. Finally, filter the solution through a 0.2 µm syringe filter.

- 2. Instrumental Conditions:

- System: A triple-detection system comprising a Refractive Index (RI) detector, a Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) detector, and a viscometer.

- Columns: A set of SEC columns (e.g., mixed-bed columns providing a suitable molecular weight separation range).

- Mobile Phase: HPLC-grade solvent (e.g., THF), degassed and maintained at a constant flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min).

- Temperature: Maintain a constant temperature in the column oven and detectors (e.g., 35°C) for stable baselines and reproducible results [32].

- 3. System Calibration: While traditional GPC requires a column calibration curve, the use of a light scattering detector provides an absolute molecular weight measurement. The system must be calibrated for the detector normalization and inter-detector delay volumes using a narrow-dispersity polymer standard (e.g., polystyrene) of known molecular weight. The dn/dc value (specific refractive index increment) for the polymer-solvent pair must be known, either from literature or by offline measurement [32].

- 4. Data Analysis: The software calculates the absolute weight-average molecular weight (Mw) and number-average molecular weight (Mn) directly from the light scattering data. The polydispersity index (PDI) is calculated as Mw/Mn. The intrinsic viscosity (IV) is obtained from the viscometer. Generate a Mark-Houwink plot (log IV vs. log M). A plot for a linear polymer will show a consistent upward trend, while a branched polymer will appear as a parallel line offset to lower intrinsic viscosity or show a downward curve, depending on the branching architecture [32].

Visualizing the Analytical Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical sequence of steps for both GC and SEC/GPC analyses, providing a clear overview of the workflows for researchers.

Diagram Title: GC and SEC/GPC Polymer Analysis Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful chromatographic analysis relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and consumables. The following table details the essential items for performing the experiments described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Chromatographic Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| GC Capillary Column (e.g., 100% PDMS) | The stationary phase for separating volatile compounds; a non-polar phase like polydimethylsiloxane offers broad applicability [31]. |

| SEC/GPC Columns (e.g., mixed-bed) | The packed bed that separates polymer molecules by their size in solution [32]. |

| HPLC-grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, THF) | High-purity mobile phases and solvents for sample preparation, free from impurities that can interfere with detection [31] [32]. |

| Narrow Dispersity Polymer Standards (e.g., Polystyrene) | Used for system calibration in traditional GPC and for verifying the performance of light scattering detectors [32]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (e.g., Dioctyl Adipate, Toluene Diisocyanate) | High-purity chemical standards for calibrating GC and LC methods, ensuring accurate identification and quantification [31]. |

| Syringe Filters (0.2 µm and 0.45 µm) | For removing particulate matter from samples prior to injection, protecting the chromatographic column from blockage [31] [32]. |

| dn/dc Value (for polymer-solvent pair) | A critical constant required for absolute molecular weight determination using light scattering detection [32]. |

| Temocapril | Temocapril, CAS:111902-57-9, MF:C23H28N2O5S2, MW:476.6 g/mol |

| Tributyrin | Tributyrin, CAS:60-01-5, MF:C15H26O6, MW:302.36 g/mol |

Gas Chromatography and Size Exclusion Chromatography are not competing techniques but rather complementary pillars of comprehensive polymer characterization. GC excels in providing a detailed inventory of the small molecules that comprise a formulation or are generated during its degradation, directly impacting material purity, safety, and performance. In contrast, SEC/GPC, especially when equipped with advanced detection, offers an unparalleled view into the macromolecular architecture, quantifying the molecular weight distribution and structural features like branching that govern bulk physical properties. For researchers conducting a comparative analysis of polymer degradation, the strategic application of both methods is imperative. By integrating compositional data from GC with structural and molecular weight data from SEC/GPC, scientists can construct a complete mechanistic picture of degradation pathways, enabling the development of more durable and predictable polymeric materials for pharmaceutical and advanced technological applications.

In the field of materials science, particularly in the comparative analysis of polymer degradation methods, understanding molecular and crystalline structure is paramount. Advanced characterization techniques are indispensable for elucidating changes in polymer architecture, crystallinity, and chemical functionality during degradation processes. Among the most powerful tools for this purpose are Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD). These techniques provide complementary information across different length scales, from atomic-level molecular dynamics to long-range crystalline order. This guide provides an objective comparison of these core spectroscopic techniques, detailing their fundamental principles, specific applications in polymer degradation research, and experimental protocols, supported by current experimental data.

The following table provides a high-level comparison of the three core techniques, highlighting their primary functions, physical principles, and key output metrics relevant to polymer degradation studies.

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Techniques for Polymer Structural Analysis

| Technique | Primary Information | Underlying Principle | Key Metrics for Degradation | Sample Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR | Molecular structure, dynamics, chemical environment, quantitative composition [37] [38] | Interaction of atomic nuclei (e.g., ^1H, ^13C) with magnetic fields and RF pulses [37] | Relaxation times (Tâ‚, Tâ‚‚), chemical shift, residual dipolar coupling [37] [38] | Solid or liquid |

| FTIR | Chemical bonding, functional groups, molecular vibrations [37] [39] | Absorption of IR radiation by vibrating chemical bonds [39] | Presence/absence of characteristic bands (e.g., C=O, O-H), band shifts [37] [40] | Solid, liquid, gas |

| XRD | Crystalline structure, phase identification, crystallite size, degree of crystallinity [41] [42] | Constructive interference of X-rays scattered by crystalline planes (Bragg's Law) [41] | Crystallinity Index (CI), crystal lattice parameters, peak position & width [41] [42] | Solid (crystalline) |

Principles and Specific Applications in Polymer Degradation

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy probes the local magnetic fields around atomic nuclei. When placed in a strong external magnetic field, nuclei like ^1H and ^13C absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation at frequencies characteristic of their chemical environment [37]. This provides unparalleled insight into molecular structure, dynamics, and composition.

In polymer degradation studies, advanced NMR methods are crucial. 1D and 2D NMR relaxometry can characterize the dynamics of polymer chains and monitor changes during degradation by measuring spin-spin (Tâ‚‚) and spin-lattice (Tâ‚) relaxation times [37]. For instance, the degradation of electrospun nanofibers made from polymers like PVA, chitosan, and fish gelatin has been characterized using Tâ‚‚ distributions and 2D EXSY Tâ‚‚-Tâ‚‚ exchange maps [37]. Furthermore, solid-state ^13C Cross-Polarization Magic Angle Spinning (CP-MAS) NMR is a gold-standard method for determining the crystallinity index of cellulose by deconvoluting the C4 carbon region into crystalline and amorphous contributions [42]. Double-quantum (DQ) NMR measurements can also probe residual dipolar coupling in rigid components of complex organo-mineral fertilizers, filtering out signals from highly mobile chains [38].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy operates on the principle that chemical bonds vibrate at specific frequencies when exposed to infrared light. The technique measures the absorption of this light, creating a molecular "fingerprint" based on the vibrational modes of the functional groups present (e.g., stretching, bending) [39]. The Fourier transform process converts the raw interferogram signal into a readable spectrum [39].

FTIR is extensively used to monitor chemical changes during polymer degradation. It can identify the formation of new functional groups, such as carbonyl groups (C=O) from oxidation, which appear around 1700 cmâ»Â¹, or the disappearance of others due to chain scission [39] [4]. It is also employed to calculate the Crystallinity Index (CI) in polymers like cellulose, often by using height ratios of bands sensitive to crystalline and amorphous regions (e.g., the A1370/A2900 method) [42]. The Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode enables rapid, minimal sample preparation analysis of solids and liquids, making it ideal for screening falsified drugs and analyzing degraded polymer surfaces [40].

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD relies on Bragg's Law to analyze the atomic structure of crystalline materials. When a monochromatic X-ray beam strikes a crystalline sample, it is diffracted at specific angles that correspond to the spacings between atomic planes [41]. The resulting diffractogram is a unique pattern that acts as a fingerprint for crystalline phases.

The primary application of XRD in polymer science is the quantification of crystallinity. The Crystallinity Index (CI) can be calculated using several methods, with the Segal method being a common, though rough, estimate [41] [42]. More accurate methods involve deconvoluting the diffraction pattern into crystalline peaks (often modeled with Voigt functions) and an amorphous halo [41]. The area under the crystalline peaks relative to the total area gives the CI. Polymer degradation often leads to changes in crystallinity; for example, abiotic or enzymatic breakdown typically targets amorphous regions first, potentially increasing the overall CI, while further degradation can dismantle crystalline domains [27] [4]. XRD is also used to identify crystal phase changes (e.g., from cellulose I to cellulose II) induced by chemical treatments [42].

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Determining Cellulose Crystallinity Index via XRD Deconvolution [41]

- Sample Preparation: Cellulose samples are dried and mounted on a quartz substrate. For amorphous reference, a separate sample is ball-milled for 6.5 hours.

- Data Acquisition: XRD patterns are collected using a diffractometer with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å), typically over a 2θ range of 5° to 50°.

- Deconvolution & CI Calculation:

- The amorphous profile from the ball-milled sample is fitted with a Fourier series to accurately model its contribution.

- The diffraction pattern of the semi-crystalline sample is deconvoluted using crystalline peaks (Voigt functions) and the Fourier-series-fitted amorphous profile.

- CI is calculated as the ratio of the integrated area of the crystalline peaks to the total area of the diffractogram.

Protocol 2: Structural Characterization of Electrospun Nanofibers by NMR [37]

- Sample Preparation: Nanofibers are prepared via electrospinning of polymer solutions (e.g., Chitosan/PVA, Fish Gelatin/PVA) and used as-is.

- Data Acquisition:

- 1D NMR: A Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence is used to measure Tâ‚‚ relaxation times, followed by an Inverse Laplace Transform to obtain a Tâ‚‚ distribution.

- 2D NMR: Tâ‚-Tâ‚‚ and Tâ‚‚-Tâ‚‚ (EXSY) correlation experiments are performed to study chemical exchange and dynamics between different polymer phases.

- Data Interpretation: A longer Tâ‚‚ component is associated with more mobile (often amorphous) polymer chains, while a shorter Tâ‚‚ component corresponds to rigid (often crystalline) regions. Changes in these components indicate morphological alterations due to degradation.

Protocol 3: Monitoring Polymer Degradation via ATR-FTIR [4]

- Sample Preparation: Polymer films or fragments are placed directly onto the ATR crystal. Minimal pressure is applied to ensure good contact.

- Data Acquisition: Spectra are recorded in the range of 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹ with a resolution of 4 cmâ»Â¹, averaging 64 scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. A background scan of the clean crystal is collected first.

- Data Interpretation: Spectra are baseline-corrected and normalized. The appearance of new peaks (e.g., -OH around 3400 cmâ»Â¹ from hydrolysis, or C=O from oxidation) or changes in the relative intensity of existing peaks (e.g., the crystallinity-sensitive bands in cellulose) are tracked over degradation time.

Quantitative Data Comparison

The following table summarizes experimental data obtained from the literature, demonstrating the quantitative output of these techniques in practical research scenarios.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Polymer Characterization Studies

| Study Material | Technique | Key Quantitative Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospun PVA Nanofibers [37] | 1D/2D NMR | Order degree range: 0.27 to 0.61 (from ANN analysis of NMR data) | More ordered structure than natural polymer nanofibers. |

| Electrospun Chitosan/Fish Gelatin Nanofibers [37] | 1D/2D NMR | Order degree range: 0.051 to 0.312 (from ANN analysis of NMR data) | Less ordered, more amorphous structure compared to PVA. |