Fabrication of Polymer Nanocomposites: Advanced Methods, Biomedical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive examination of polymer nanocomposite fabrication, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fabrication of Polymer Nanocomposites: Advanced Methods, Biomedical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of polymer nanocomposite fabrication, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science behind nanomaterials like graphene, carbon nanodots, and metal oxides, and details advanced fabrication methodologies from solution casting to 3D printing. The content addresses critical challenges in optimization and dispersion, while also covering validation techniques for biomedical applications, including drug delivery, antimicrobial coatings, and bioimaging. By synthesizing current research and future trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging these advanced materials in next-generation therapeutic and diagnostic solutions.

The Building Blocks: Understanding Nanomaterials and Polymer Matrices for Advanced Composites

In the realm of materials science, polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) represent a significant advancement, achieved by dispersing nanoscale fillers into polymer matrices. These nanofillers, typically with at least one dimension less than 100 nanometers, impart transformative properties to the base polymer, resulting in materials with enhanced mechanical, thermal, electrical, and barrier characteristics [1]. The immense surface area of well-dispersed nanofillers creates a substantial polymer-filler interfacial region, known as the interphase, which governs the composite's ultimate properties [2]. Based on their chemical composition and origin, nanofillers are fundamentally categorized into three core classes: carbon-based, organic, and inorganic. This document delineates these classes, their properties, and standard protocols for their incorporation into polymers, providing a framework for research and development aimed at fabricating advanced functional materials.

Classification and Properties of Core Nanofiller Classes

Carbon-Based Nanofillers

Carbon-based nanofillers are renowned for their exceptional electrical and thermal conductivity, high mechanical strength, and large specific surface area [3]. When incorporated into polymeric matrices, they facilitate the creation of nanocomposites for advanced applications in electronics, energy storage, and aerospace [4].

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): CNTs are cylindrical nanostructures composed of rolled graphene sheets, classified as either single-walled (SWCNT) or multi-walled (MWCNT) [1]. They exhibit an elastic modulus on the order of 1 TPa and a tensile strength that can reach 300 GPa for defect-free structures [1]. Their high aspect ratio and electrical conductivity make them ideal for creating conductive networks within polymers at low percolation thresholds.

- Graphene and its Derivatives: Graphene is a single layer of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice [1]. It possesses a Young's modulus of approximately 1 TPa, a fracture strength of 125 GPa, and exceptional electrical and thermal conductivity [1]. Graphene oxide (GO) is a solution-processable derivative of graphene, decorated with oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, epoxide, carboxyl), which makes it amphiphilic and amenable to chemical functionalization for improved dispersion [3].

- Other Carbon Allotropes: This class also includes nanodiamond, fullerenes, and carbon dots, each offering unique optical, electronic, and mechanical properties for specialized applications [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Carbon-Based Nanofillers

| Nanofiller Type | Structure/Dimensions | Key Properties | Exemplary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Single graphene cylinder; Diameter: ~1-2 nm [1] | Elastic Modulus: ~1 TPa; Superior electrical & thermal conductivity [1] | Conductive films, transistors, sensors [3] |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Multiple concentric graphene cylinders; Diameter: 5-20 nm [1] | High tensile strength; Good electrical conductivity [1] | Polymer reinforcement, flexible electrodes, antistatic coatings [3] [4] |

| Graphene | 2D sheet; Thickness: ~0.34 nm [1] | Young's Modulus: ~1 TPa; Electrical conductivity: up to 6000 S/cm [1] | Barrier films, composite reinforcement, transparent conductors |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Functionalized graphene sheet with O-groups [3] | Solution-processable; Amphiphilic; Insulating [3] | Precursor to conductive graphene, membrane materials, composite filler |

| Carbon Black | Nanoparticle aggregates [4] | Conductive; High surface area; UV absorbing | Static dissipation, laser welding additives, pigment [4] |

Inorganic Nanofillers

Inorganic nanofillers include a wide range of metal oxides, clays, and other ceramic nanoparticles. They are primarily used to enhance mechanical strength, thermal stability, flame retardancy, and gas barrier properties of polymers [5] [1].

- Layered Silicates (Nanoclays): Nanoclays, such as montmorillonite, are layered silicates that can be dispersed in polymers to form intercalated or exfoliated structures [5] [1]. An exfoliated structure, where individual silicate layers are uniformly dispersed in the polymer matrix, leads to significant improvements in modulus and gas barrier properties due to the high aspect ratio and creation of a "tortuous path" for diffusing molecules [1].

- Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Nanoparticles like titanium dioxide (TiO₂), silica (SiO₂), and alumina (Al₂O₃) are common inorganic fillers. For instance, TiO₂ nanoparticles are known for their UV resistance, hardness, and antibacterial activity [6]. Silica nanoparticles are widely used to reinforce polymers, improving mechanical properties like fracture strength [5].

- Other Inorganic Fillers: This category also includes boron nitride (BN) for thermal conductivity, layered double hydroxides (LDH), and molybdenum disulphide (MoS₂) [2].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Inorganic Nanofillers

| Nanofiller Type | Structure/Dimensions | Key Properties | Exemplary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montmorillonite Clay | Layered silicate; Layer thickness: ~1 nm [1] | High aspect ratio (~100-1500); Improves modulus & gas barrier [1] [2] | Food packaging, automotive parts, flame-retardant materials |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Nanoparticle; ~30 nm size [6] | UV resistance; Hardness; Antibacterial; Photocatalytic [6] | Self-cleaning coatings, UV-protective films, biomedical composites |

| Nano-Silica (SiO₂) | Spherical nanoparticle [5] | Improves fracture strength, thermal & chemical resistance [5] | Reinforcing filler for tires, adhesives, and transparent composites |

| Boron Nitride (BN) | Layered structure (similar to graphite) [2] | High thermal conductivity; Electrically insulating [2] | Thermal interface materials, electronic packaging |

Organic Nanofillers

Organic nanofillers are derived from natural or synthetic carbon-based sources and are often prized for their sustainability, biodegradability, and low cost. They can improve mechanical properties and impart specific functionalities like antimicrobial activity [6].

- Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) and Nanofibrils (CNF): These are derived from plant biomass and possess high tensile strength and stiffness. They are used to create reinforced biocomposites with improved mechanical and barrier properties [2].

- Bio-based Nanoparticles: This includes nanoparticles derived from agricultural waste, such as date seed nanoparticles (DSNP). DSNP, composed mainly of mannan hemicellulose, can enhance the microhardness, wear resistance, and compressive modulus of polymers like PMMA, offering an economical and eco-friendly reinforcing option [6].

- Engineered Polymer Particles: Nanoscale particles of one polymer can be used as a filler in a matrix of another polymer to create tailored morphologies and properties.

Table 3: Key Characteristics of Organic Nanofillers

| Nanofiller Type | Structure/Dimensions | Key Properties | Exemplary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date Seed Nanoparticles (DSNP) | Irregular organic particles; ~20 nm size [6] | Improves microhardness & wear resistance; Low cost; Eco-friendly [6] | Reinforcing bio-filler for PMMA in dental applications [6] |

| Nanocellulose | Rod-like crystals or fibrils; Width: 5-20 nm [2] | High stiffness; Biodegradable; Renewable | High-strength biodegradable plastics, barrier coatings |

Experimental Protocols for Nanocomposite Fabrication

Protocol: Melt Compounding of Silica/PMMA Nanocomposites

This protocol describes a simple, industrially viable method for dispersing unmodified silica nanoparticles into a thermoplastic polymer (e.g., PMMA) without surface modification or complex chemical reactions [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- Polymer Matrix: Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) pellets.

- Nanofiller: Colloidal silica nanoparticles (e.g., Aerosil).

- Equipment: Twin-screw extruder, vacuum oven, hydraulic press, injection molding machine.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Drying: Dry PMMA pellets in a vacuum oven at 80°C for at least 12 hours to remove moisture. 2. Dry Mixing: Manually pre-mix the dried PMMA pellets with the desired weight percentage (e.g., 1-10 wt%) of silica nanoparticles in a zip-lock bag. 3. Melt Compounding: Feed the pre-mix into a twin-screw extruder. Utilize a temperature profile appropriate for PMMA (e.g., 180-220°C from feed to die) and a high screw speed (e.g., 200-300 rpm) to generate sufficient shear stress. The shear forces in the molten polymer break down the loose silica agglomerates, leading to dispersion [5]. 4. Pelletizing: The extruded strand is passed through a water bath and subsequently pelletized. 5. Post-processing & Molding: Dry the composite pellets and then injection mold or compression mold them into standard test specimens (e.g., ASTM D638 for tensile testing) for characterization.

3. Critical Control Points

- Moisture Control: Ensure polymers and fillers are thoroughly dried to prevent void formation and polymer degradation.

- Shear Optimization: Screw speed and design must be optimized to provide enough shear for deagglomeration without degrading the polymer matrix.

- Safety: Standard personal protective equipment (PPE) including a lab coat, safety glasses, and heat-resistant gloves must be worn.

Protocol: In Situ Polymerization for PANI/CNT Nanocomposites

This protocol involves the oxidative polymerization of aniline in the presence of carbon nanotubes, resulting in a uniform coating of polyaniline (PANI) on the CNT surface, which is beneficial for sensor and supercapacitor applications [3] [7].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- Monomer: Aniline.

- Nanofiller: Single-walled or multi-walled carbon nanotubes.

- Oxidizing Agent: Ammonium persulfate (APS).

- Acid Dopant: 1M Hydrochloric acid (HCl).

- Solvent: Deionized water.

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, three-neck flask, mechanical stirrer, ice bath, vacuum filtration setup.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. CNT Dispersion: Disperse a known weight of CNTs (e.g., 1-5 wt% relative to aniline) in 1M HCl using an ultrasonic bath for 30-60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous dispersion. 2. Monomer Addition: Transfer the CNT dispersion to a three-neck flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer. Add the aniline monomer to the flask and continue stirring in an ice bath (0-5°C). 3. Initiator Preparation: Dissolve ammonium persulfate in 1M HCl in a separate beaker, pre-cooled in the ice bath. 4. Polymerization: Slowly add the APS solution dropwise to the stirring CNT/aniline mixture. The reaction mixture will gradually darken. 5. Reaction Completion: Allow the reaction to proceed with continuous stirring for 4-12 hours in the ice bath. 6. Isolation and Washing: Recover the resulting PANI/CNT nanocomposite by vacuum filtration. Wash the precipitate repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol until the filtrate is clear and neutral. 7. Drying: Dry the final product in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 24 hours.

3. Critical Control Points

- Temperature Control: Maintaining a low temperature (0-5°C) is crucial for controlling the polymerization rate and obtaining the desired emeraldine salt form of PANI.

- Dispersion Quality: Homogeneous initial dispersion of CNTs is essential to prevent aggregation during polymerization and to ensure a uniform coating.

- Safety: Aniline is toxic, and APS is a strong oxidizer. Handling must be conducted in a fume hood with appropriate PPE.

Protocol: Solvent Casting for PMMA/DSNP Biocomposites

This protocol outlines the preparation of PMMA composites reinforced with organic date seed nanoparticles for dental applications, utilizing a simple solvent casting and self-curing method [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- Polymer Matrix: Poly(methyl methacrylate) powder and methyl methacrylate monomer liquid.

- Nanofiller: Date seed nanoparticles (DSNP, ~20 nm) [6].

- Solvent: Not required for self-curing.

- Equipment: Analytical balance, mixing vessel, cylindrical molds, pressure pot.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Weighing: Accurately weigh the PMMA powder and the desired weight percentage of DSNP (e.g., 0.3 to 1.5 wt%) [6]. 2. Dry Mixing: Manually mix the PMMA powder and DSNP in a container to achieve a homogeneous dry pre-mix. 3. Monomer Addition: Add the PMMA monomer liquid (hardener) to the powder mixture at a recommended ratio (e.g., 1:2 monomer-to-powder by weight). Mix thoroughly for a set time (e.g., 20 minutes) to form a homogeneous dough [6]. 4. Packing and Curing: Pack the dough into a cylindrical mold. Cure the composite at room temperature and under pressure (e.g., 1.4 bar) for 2 hours to obtain the final specimen [6]. 5. Post-processing: The cured samples are then demolded and can be cut into specific dimensions for testing.

3. Critical Control Points

- Mixing Homogeneity: Ensuring a uniform distribution of DSNP in the PMMA powder before adding the monomer is critical to avoid agglomerates in the final composite.

- Curing Conditions: Time, temperature, and pressure during curing must be controlled to achieve optimal polymerization and prevent porosity.

- Filler Loading: Optimal mechanical properties (e.g., microhardness, compressive modulus) are typically observed at specific filler loadings (e.g., 1.2 wt% for DSNP); exceeding this can lead to agglomeration and property deterioration [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Nanocomposite Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Twin-Screw Extruder | Melt compounding & dispersion of nanofillers in thermoplastics [5] | Provides high shear stress essential for breaking down nanofiller agglomerates. |

| Ultrasonic Bath/Probe | Dispersion of nanofillers in solvents or monomers for in-situ or solution methods [3] | Crucial for achieving initial homogeneous dispersion and preventing re-agglomeration. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNT/SWCNT) | Conductive filler for creating electrically active composites [3] [1] | Prone to aggregation; often requires functionalization or surfactant use for good dispersion. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Versatile, solution-processable 2D nanofiller [3] | Serves as a precursor to conductive graphene; functional groups allow for covalent modification. |

| Montmorillonite Clay | Layered silicate for improving mechanical strength & gas barrier properties [1] [2] | Often requires organic modification (e.g., with alkylammonium salts) to be compatible with hydrophobic polymers. |

| Date Seed Nanoparticles (DSNP) | Economical & eco-friendly organic filler for reinforcement [6] | Example of a sustainable filler from waste biomass; can be competitive with inorganic fillers. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Oxidizing initiator for in-situ polymerization of aniline [7] | Reaction must be conducted at low temperatures (0-5°C) for controlled polymerization. |

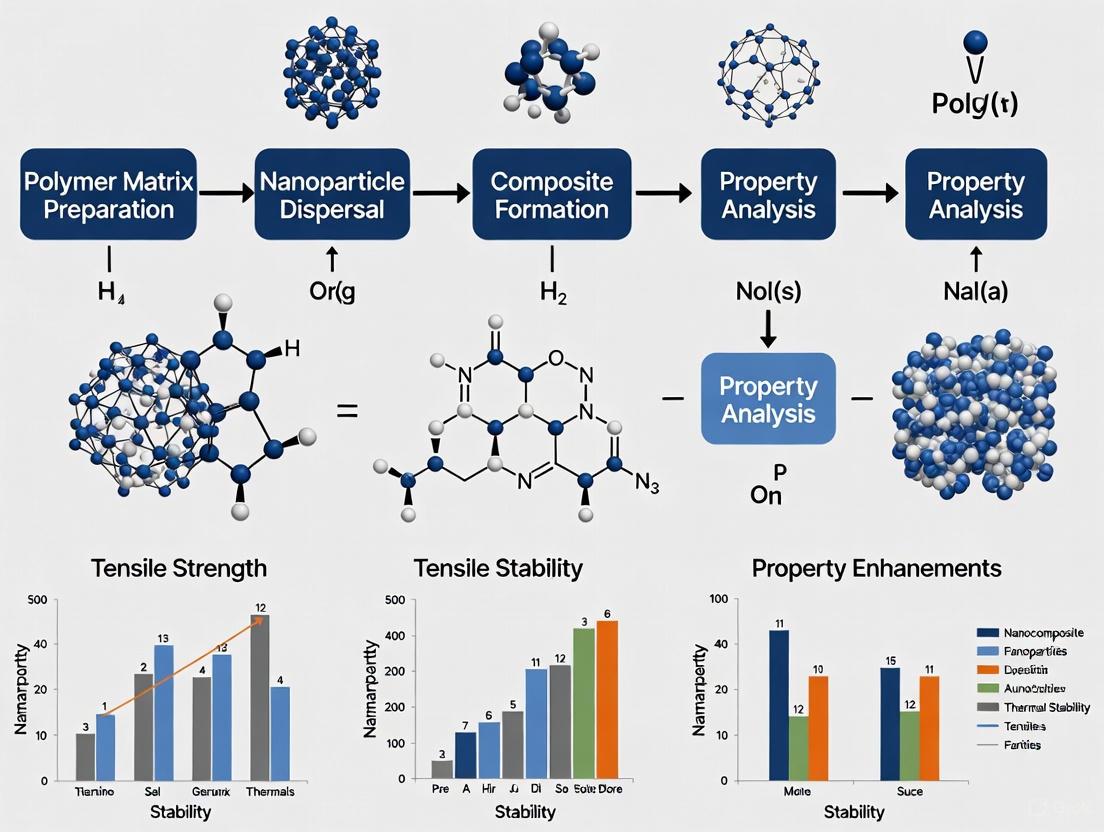

Visualization of Nanocomposite Fabrication Workflows

Diagram 1: Primary fabrication methods for polymer nanocomposites, highlighting key dispersion and consolidation steps.

Diagram 2: Morphology types for layered filler (e.g., clay) nanocomposites, determining final properties.

The selection of an appropriate polymer matrix is a critical first step in the fabrication of polymer nanocomposites, dictating the final material's properties, processability, and suitability for advanced applications. Polymer matrices are broadly categorized as either synthetic or biopolymer (natural) in origin, each with distinct advantages and limitations [8] [9]. This selection is paramount in biomedical fields such as drug delivery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine, where the matrix must meet stringent requirements for biocompatibility, biodegradation kinetics, and mechanical performance [8] [10].

Synthetic polymers are chemically synthesized, offering tunable mechanical properties, predictable biodegradation rates, and high batch-to-batch consistency [10] [11]. In contrast, biopolymers are derived from natural sources such as plants, animals, or microorganisms, and typically exhibit inherent biocompatibility, bioactivity, and often, enhanced sustainability profiles [12] [9]. The emerging trend involves blending or creating composites from both types to develop materials that synergize the performance and processability of synthetic polymers with the bio-recognition and low immunogenicity of biopolymers [8] [11]. This document provides a structured comparison and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting and processing polymer matrices for nanocomposites fabrication.

Comparative Analysis: Synthetic Polymers vs. Biopolymers

The choice between synthetic and biopolymer matrices involves a multi-faceted trade-off. The tables below summarize key characteristics, common polymers, and their applications to inform this decision.

Table 1: Characteristics and Applications of Common Synthetic Polymer Matrices

| Polymer | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications in Nanocomposites | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biodegradable, biocompatible, good mechanical strength, brittle [12] [10] | Tissue engineering scaffolds, drug delivery systems, packaging [12] [8] | Hydrophobic, slow degradation rate, poor toughness [8] |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Biodegradable, semi-crystalline, high elongation at break, slow degradation [8] [10] | Long-term implantable devices, drug delivery capsules, tissue engineering [8] | Low mechanical strength, hydrophobic [8] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Water-soluble, biodegradable, highly biocompatible, excellent film-forming ability [11] | Hydrogel matrices for wound dressings, drug delivery, emulsifier [8] [11] | Insufficient elasticity in pure form [11] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Hydrophilic, biocompatible, resistant to protein adsorption [8] [11] | Drug conjugation, hydrogel matrices for tissue engineering, surface functionalization [8] | Non-biodegradable in low MW forms [8] |

| Polypropylene (PP) | High chemical resistance, good mechanical properties, low cost, non-biodegradable [10] | Medical devices, sutures, prosthetic meshes [10] | Poor UV resistance, flammable, limited functional groups for modification [10] |

Table 2: Characteristics and Applications of Common Biopolymer Matrices

| Polymer | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications in Nanocomposites | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Biodegradable, biocompatible, antimicrobial, cationic, hemostatic [12] [11] | Wound healing dressings, drug delivery, tissue engineering scaffolds [12] [11] | Poor stability in aqueous solutions, low mechanical strength [12] |

| Alginate | Biocompatible, biodegradable, forms hydrogels with divalent cations [12] [11] | Cell encapsulation, wound dressings, model biofilms [12] | Low mechanical strength, limited cell adhesion [8] |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Major ECM component, high water retention, biodegradable, biocompatible [11] | Tissue regeneration, drug delivery, viscoelastic supplements [11] | Rapid degradation, poor mechanical properties [8] |

| Cellulose (and Bacterial Cellulose) | Most abundant biopolymer, high mechanical strength, biodegradable, hydrophilic [11] | Wound dressing membranes, reinforcement in composites [11] | Lacks intrinsic antibacterial activity, difficult to process [11] |

| Starch | Abundant, low-cost, biodegradable, good film-forming ability [11] | Drug delivery carriers, biodegradable packaging composites [11] | Water sensitivity, brittle [11] |

Table 3: Decision Matrix for Polymer Selection Based on Application Requirements

| Application Requirement | Recommended Polymer Type | Specific Examples & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High Mechanical Strength | Synthetic Polymers | PCL for ductility; PLA for stiffness. Biopolymers generally require reinforcement [8] [10]. |

| Rapid Biodegradation | Biopolymers (generally) | Chitosan, alginate, HA degrade more rapidly than many synthetics. PLA and PCL rates are tunable but slower [12] [8]. |

| Inherent Bioactivity | Biopolymers | Chitosan (antimicrobial), HA (cell signaling), collagen (cell adhesion) offer intrinsic biological functions [12] [11]. |

| Controlled Drug Release | Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PLA offer highly predictable and tunable degradation kinetics for controlled release profiles [8]. |

| Tissue Engineering Scaffolds | Blend/Composite | Synthetic (e.g., PLA, PCL) for structural integrity; Biopolymer (e.g., collagen, HA) for bioactivity [8] [9]. |

| Minimal Immunogenic Response | Synthetic Polymers | High-purity synthetic polymers (e.g., PEG, PLA) typically evoke a lower immune response than animal-derived biopolymers [10]. |

Polymer Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic decision-making workflow for selecting a polymer matrix based on key application requirements.

Experimental Protocols for Nanocomposite Fabrication

This section details standard protocols for incorporating nanofillers into polymer matrices, a critical step in fabricating advanced nanocomposites.

Protocol: In Situ Polymerization for 2D Material Nanocomposites

This method is suitable for creating nanocomposites with graphene oxide, MXenes, or other 2D materials, resulting in strong interfacial bonding and homogeneous dispersion [13].

1. Principle: The monomer is polymerized in the presence of a pre-dispersed nanofiller. The growing polymer chains graft onto or interact with the filler's surface, leading to a composite with excellent filler dispersion and strong matrix-filler interaction [13].

2. Materials:

- Nanofiller: e.g., Graphene Oxide (GO) flakes.

- Monomer: e.g., Methyl methacrylate (MMA), ε-Caprolactone, or other suitable monomers.

- Initiator: e.g., Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) for thermal initiation.

- Solvent: e.g., Toluene, DMF, or water, depending on monomer and filler solubility/dispersibility.

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath/probe, round-bottom flask, reflux condenser, magnetic stirrer, heating mantle, inert gas (N₂) supply.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Nanofiller Dispersion: Weigh the required amount of nanofiller (e.g., 1-5 wt% of expected polymer yield) and disperse it in the solvent using probe ultrasonication for 30-60 minutes to create a homogeneous suspension. 2. Reaction Mixture Preparation: Transfer the dispersion to a clean, dry round-bottom flask. Add the purified monomer and initiator (e.g., 1 wt% relative to monomer). 3. Deoxygenation: Seal the flask and purge the mixture with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 20-30 minutes while stirring to remove oxygen, which can inhibit free-radical polymerization. 4. Polymerization: Under a continuous inert atmosphere, heat the reaction mixture to the initiator's decomposition temperature (e.g., 60-80°C for AIBN) with constant stirring for a predetermined time (e.g., 6-24 hours). 5. Precipitation & Purification: After cooling, precipitate the resulting nanocomposite by slowly pouring the reaction mixture into a large excess of a non-solvent (e.g., methanol for PMMA) under vigorous stirring. 6. Isolation & Drying: Collect the precipitated solid via filtration or centrifugation. Wash repeatedly with non-solvent to remove residual monomer and un-grafted polymer. Dry the final product under vacuum at 40-60°C until constant weight is achieved.

4. Critical Parameters for Reproducibility:

- Filler Dispersion Quality: The duration and power of ultrasonication are critical to exfoliate and disperse the nanofiller without causing degradation.

- Oxygen Exclusion: Strict deoxygenation is essential for high monomer conversion and molecular weight in free-radical polymerizations.

- Filler:Monomer Ratio: This ratio directly impacts final composite properties and processability; it must be optimized for each system.

Protocol: Solution Blending and Casting for Biopolymer Nanocomposites

This versatile and simple method is ideal for heat-sensitive biopolymers like chitosan, alginate, and proteins, and is applicable for incorporating various nanofillers (e.g., ZnO, Ag NPs, cellulose nanofibers) [12] [14].

1. Principle: The polymer and nanofiller are separately dissolved/dispersed in a common solvent and then mixed. The solvent is evaporated, leading to the formation of a solid nanocomposite film or matrix [13].

2. Materials:

- Biopolymer: e.g., Chitosan (medium molecular weight).

- Nanofiller: e.g., Zinc Oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs).

- Solvent: e.g., 1% v/v acetic acid solution for chitosan.

- Crosslinker (Optional): e.g., Genipin or Tripolyphosphate (TPP).

- Equipment: Magnetic stirrer, ultrasonic bath, vacuum filtration setup, glass petri dishes, vacuum oven.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve the biopolymer (e.g., 2g of chitosan in 100 mL of 1% acetic acid) by stirring for several hours until a clear, viscous solution is obtained. 2. Filler Dispersion: Weigh the nanofiller (e.g., 1-10 wt% relative to polymer) and disperse it in the same solvent using ultrasonication for 20-30 minutes. 3. Blending: Add the nanofiller dispersion dropwise to the polymer solution under vigorous mechanical stirring. Continue stirring for 1-2 hours to ensure homogeneous mixing. 4. Crosslinking (Optional): For hydrogels or to improve stability, a crosslinking agent can be added at this stage with gentle stirring. 5. Casting: Pour the final mixture into a leveled glass petri dish. 6. Solvent Evaporation: Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature or in an oven at 40°C for 24-48 hours. 7. Post-processing: Carefully peel the resulting film from the petri dish. For further drying, place the film in a vacuum oven at 40°C to remove residual solvent.

4. Critical Parameters for Reproducibility:

- Solution Homogeneity: Ensure the polymer is fully dissolved and the nanofiller is uniformly dispersed before blending to prevent agglomerates.

- Solvent Evaporation Rate: A slow, controlled evaporation rate helps in forming films with uniform morphology and prevents bubble formation.

- pH Control: For biopolymers like chitosan and alginate, the solution pH can drastically affect chain conformation and crosslinking efficiency.

Experimental Workflow for Nanocomposite Fabrication and Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for fabricating and characterizing a polymer nanocomposite, integrating the protocols above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Polymer Nanocomposites Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application Notes | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A versatile, biodegradable synthetic polymer matrix for scaffolds and drug delivery [12] [8]. | Grade: Opt for medical-grade or high-purity to ensure biocompatibility. Crystallinity: Amorphous (PLLA) vs. semi-crystalline (PDLLA) affects degradation and mechanics. |

| Chitosan | A cationic biopolymer matrix with inherent antimicrobial properties for wound dressings and tissue engineering [12] [11]. | Degree of Deacetylation: Impacts solubility, biodegradability, and bioactivity. Molecular Weight: Affects solution viscosity and mechanical strength of final product. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A synthetic, slow-degrading, ductile polymer matrix for long-term implants and tissue engineering [8] [10]. | Molecular Weight: Higher MW increases melt viscosity and mechanical strength. Application: Ideal for electrospinning and 3D printing due to its low melting point. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | A 2D nanofiller for reinforcement, electrical conductivity, and functionalization in composites [13]. | Dispersion: Requires intense ultrasonication in aqueous or polar solvents. Functionalization: Surface -OH and -COOH groups allow for covalent bonding with polymer matrices. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles | A nanofiller imparting antimicrobial and reinforcing properties to biopolymer matrices like chitosan [12]. | Concentration: Optimal loading (typically 1-5%) is critical; higher loads can cause agglomeration and brittleness. Cytotoxicity: Dose-dependent effects must be evaluated for biomedical use. |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | A common thermal free-radical initiator for in situ polymerizations [13]. | Handling: Store refrigerated. Decomposition: Half-life of ~10 hours at 65°C; used to calculate polymerization time. |

| Genipin | A natural, low-toxicity crosslinking agent for biopolymers like chitosan and collagen [12]. | Reaction: Forms stable blue pigments upon crosslinking. Safety: Preferable over glutaraldehyde due to significantly lower cytotoxicity. |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | An ionic crosslinker used to form chitosan nanoparticles and hydrogels via electrostatic interaction [12]. | Process: Crosslinking is pH-dependent and occurs rapidly upon mixing. Application: Primarily used for ionic gelation and controlled release systems. |

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) represent a advanced class of materials formed by incorporating nanofillers, with at least one dimension between 1-100 nm, into a polymer matrix [1] [15]. The integration of these nanoscale fillers leads to exceptional property enhancements that are often unattainable with conventional micro-scale fillers, due to the high surface area-to-volume ratio and unique nano-effects of the additives [16] [17]. These materials have demonstrated transformative potential across aerospace, automotive, electronics, and biomedical sectors [15] [18]. This application note details the key mechanical, electrical, and thermal property enhancements achievable with nanofillers, providing structured quantitative data and standardized experimental protocols to support research and development activities.

Key Property Enhancements by Nanofiller Type

Table 1: Mechanical property enhancements achieved with various nanofillers.

| Nanofiller Type | Polymer Matrix | Filler Loading | Tensile Strength Increase | Modulus Increase | Reference System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide-Nanosilica Hybrid | Isophthalic Polyester | 0.3 wt% GO + 3 wt% NS | 38% | 25% | Neat resin [19] |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Silicone Rubber | 3 phr | - | 125% (Compressive) | Control sample [17] |

| Ag Nanoparticles | PVA/CMC/PEDOT:PSS | 7 mg | - | - | Base film [20] |

| Triple-Filler Hybrid (CNT, Clay, Fe) | Silicone Rubber | Hybrid system | Significant improvement | 137% (Compressive) | Control sample [17] |

Table 2: Electrical and thermal property enhancements achieved with various nanofillers.

| Nanofiller Type | Polymer Matrix | Filler Loading | Electrical Conductivity | Thermal Conductivity | Reference System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag Nanoparticles | PVA/CMC/PEDOT:PSS | 7 mg | 2.29 × 10⁻⁷ S·cm⁻¹ | - | 1.98 × 10⁻⁹ S·cm⁻¹ [20] |

| Boron Nitride with Lead Oxide | Polymer Nanocomposite | 13 wt% | - | 18.874 W/(m·K) | Base composite [17] |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide | Polyetherimide | 20 wt% | ~10⁻⁷ S/cm | - | Base polymer [17] |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Various Polymers | 0.5-5 wt% | Reaches percolation threshold | Significant improvement | Insulating polymer [1] [21] |

Mechanical Properties Enhancement

Nanofillers remarkably enhance mechanical properties including tensile strength, modulus, stiffness, and fracture toughness through several reinforcing mechanisms. The high aspect ratio of nanofillers like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene enables efficient stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the stiff nanofillers [1] [22]. The enormous surface area of nanofillers creates extensive polymer-filler interfaces, facilitating strong interfacial interactions and restricting polymer chain mobility [16] [17]. Hybrid filler systems demonstrate synergistic effects; for instance, combining one-dimensional CNTs with two-dimensional graphene creates a robust network that significantly improves load transfer and mechanical strength [23] [19].

Electrical Properties Enhancement

The incorporation of conductive nanofillers transforms insulating polymers into conductive composites through the formation of percolative networks. Carbon-based nanofillers including CNTs, graphene, and carbon black impart electrical conductivity when their concentration exceeds the percolation threshold, forming continuous conductive pathways [1] [21]. The electrical conductivity of nanocomposites exhibits a sharp, non-linear increase at this critical filler concentration, with enhancements reaching several orders of magnitude [1] [20]. Nanofillers with high aspect ratios, such as CNTs and graphene nanoribbons, achieve percolation at lower loadings due to their network-forming capability [21]. Research demonstrates that Ag nanoparticles significantly increase DC conductivity from 1.98 × 10⁻⁹ to 2.29 × 10⁻⁷ S·cm⁻¹ in PVA/CMC/PEDOT:PSS systems [20].

Thermal Properties Enhancement

Thermal stability and conductivity are substantially improved through nanofiller incorporation. Thermally conductive nanofillers such as graphene, boron nitride, and CNTs create percolating networks for efficient heat transport, with graphene composites achieving exceptional thermal conductivity up to 5000 W/m·K in isolated forms [1] [15]. Nanofillers act as superior insulators and mass transport barriers, enhancing thermal stability and flame retardancy by forming protective char layers that delay combustion [22] [19]. Studies report thermal conductivity reaching 18.874 W/(m·K) in boron nitride and lead oxide nanocomposites at 13 wt% loading [17]. Additionally, nanocomposites demonstrate improved glass transition temperatures and maximum thermal decomposition temperatures, expanding their operational temperature ranges [19].

Experimental Protocols

Solution Casting for Nanocomposite Fabrication

Table 3: Key research reagents for solution casting protocol.

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | Average MW ~534,000 g/mol | Polymer Matrix [23] |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Purity >95%, OD: 10-20 nm, L: 0.5-2 μm | Conductive Nanofiller [23] |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Analytical grade, purity ≥99.8% | Solvent [23] |

| Graphite Nanoparticles | From mechanical pencil lead (0.7 mm) | Reinforcing Nanofiller [23] |

Figure 1: Solution casting workflow for nanocomposites.

Procedure:

- Polymer Dissolution: Dissolve 1 g polymer (e.g., PVDF, PVA) in 50 ml of appropriate solvent (e.g., DMF, deionized water) with constant stirring at elevated temperature (70-90°C) until completely dissolved [23] [20].

- Filler Incorporation: Gradually add nanofillers (e.g., 20 mg MWCNTs + 30 mg graphite nanoparticles for PVDF system) to the polymer solution under continuous stirring [23].

- Homogenization: Subject the mixture to ultrasonication using a bath sonicator for 1 hour to deagglomerate nanoparticles and ensure uniform dispersion [23] [20].

- Casting: Pour the homogeneous solution into polystyrene Petri dishes, ensuring even distribution.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow solvent evaporation undisturbed overnight at room temperature [23].

- Drying: Transfer the cast film to a hot air oven at 100°C for 2 hours to remove residual solvent [23].

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent selection based on polymer-nanofiller compatibility

- Ultrasonication time and power to prevent nanofiller damage

- Controlled evaporation rate to avoid bubble formation

- Drying temperature below polymer degradation point

Melt Blending Protocol

Figure 2: Melt blending process for nanocomposites.

Procedure:

- Material Preparation: Pre-dry polymer pellets and nanofillers to remove moisture content.

- Melting: Feed polymer into a twin-screw extruder with temperature zones set according to polymer melting point (e.g., 180°C for PLA) [18].

- Filler Incorporation: Add nanofillers dropwise into the melting polymer through the feeder port.

- Melt Blending: Process the mixture in a Haake MiniLab II co-rotating twin-screw extruder for 15 minutes retention time at 20 rpm to achieve homogeneous dispersion [18] [16].

- Pelletization: Extrude the nanocomposite through a die and pelletize the strands for further processing.

- Molding: Process pellets using injection molding or compression molding to form final products.

Critical Parameters:

- Optimized temperature profile to prevent thermal degradation

- Screw speed and design to control shear forces

- Residence time for complete dispersion without filler damage

- Cooling rate to control crystallization behavior

Advanced Dispersion Techniques

Physical Dispersion Methods

Achieving optimal nanofiller dispersion remains critical for maximizing property enhancements in PNCs. Advanced physical dispersion techniques include:

Ultrasonication: Uses high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles that generate intense local pressure and shear forces, effectively breaking apart nanoparticle clusters [16]. Particularly effective for CNT dispersion, but excessive ultrasonication can cause nanotube shortening and surface defects [16].

Bead Milling: Grinds nanoparticle aggregates between small beads in a rotating chamber, generating high shear stress suitable for producing stable dispersions at larger scales [16]. Effective for high-viscosity systems but requires optimization of bead size and material to prevent contamination.

Three-Roll Milling: A shear-intensive technique particularly effective for dispersing nanoparticles in highly viscous matrices by passing the mixture through three rollers [16]. Commonly used for graphene and clay composites where uniform dispersion of plate-like particles is necessary.

Twin-Screw Extrusion: Applies both shear and thermal energy through intermeshing screws, making it suitable for industrial-scale production [16]. Offers continuous processing capability with controllable shear forces.

The strategic incorporation of nanofillers into polymer matrices enables remarkable enhancements in mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties, far exceeding the capabilities of traditional composites. The quantitative data and standardized protocols provided in this application note serve as essential guidelines for researchers developing next-generation polymer nanocomposites for advanced applications. Property enhancements are critically dependent on achieving optimal nanofiller dispersion and polymer-filler interfacial interactions, which can be accomplished through the detailed fabrication and characterization methods outlined. As research progresses, the development of hybrid nanofiller systems and sustainable nanocomposites presents promising avenues for creating multifunctional materials with tailored properties for specialized applications across diverse industrial sectors.

Interfacial Interactions and Bonding Mechanisms in Nanocomposites

In the field of polymer nanocomposites fabrication, the interface between the nanofiller and the polymer matrix is not merely a boundary but a dynamic, three-dimensional region that governs overall material performance. The properties of this interfacial region—dictated by chemical, physical, and mechanical bonding mechanisms—determine the efficiency of stress transfer, environmental stability, and ultimately, the composite's suitability for advanced applications. Achieving optimal properties in polymer nanocomposites requires a deep understanding of these interfacial interactions, which can be engineered through surface treatments, precise processing, and selective material pairing. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for characterizing and manipulating these critical interfaces, with particular relevance for scientific researchers and drug development professionals who require precise control over material properties in complex biological or structural environments.

Fundamental Bonding Mechanisms and Interfacial Phenomena

Primary Interaction Mechanisms

The interfacial region in polymer nanocomposites facilitates property enhancement through several distinct but often overlapping bonding mechanisms. Physical adsorption occurs through secondary interactions including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic attractions, which although individually weak, become significant at the nanoscale due to the enormous specific surface area of nanofillers [24]. Chemical bonding provides stronger, more durable interfaces through covalent attachment between functionalized nanoparticle surfaces and polymer chains, often mediated by coupling agents such as silanes [25]. Additionally, mechanical interlocking contributes to interfacial strength when polymer chains physically entangle with surface features or porous structures on nanofillers. The dominance of any particular mechanism depends on the chemical nature of both components and the processing conditions employed.

Bilayer Interfacial Architecture in Polar Polymers

Recent advanced characterization techniques have revealed that the interfacial region around nanoparticles in polar polymers exhibits a complex bilayer architecture rather than a simple monolayer. Direct observation using techniques like AFM-IR and PFM has identified:

- An inner bound layer (~10 nm thick) where polymer chains are strongly adsorbed to the nanoparticle surface with aligned molecular dipoles and higher segment density [26]. This layer exhibits distinct polar conformation and remains stable under mechanical and thermal stress.

- An outer polar layer (extending over 100 nm) with randomly oriented dipoles that gradually transition to bulk polymer properties [26]. This extended interfacial zone demonstrates that nanoparticle influence permeates far beyond immediate surface contact.

The spatial distribution and properties of these interfacial layers are significantly affected by interparticle distance. At low nanoparticle loadings where interparticle distances are large, complete polar interfacial regions form around isolated nanoparticles. As loading increases and interparticle distance decreases, overlapping interfacial regions can weaken polar conformation development, while interconnected nanoparticles create continuous interfacial pathways [26].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanofiller Types and Their Interfacial Characteristics

| Nanofiller Type | Representative Materials | Typical Dimensions | Key Interfacial Advantages | Primary Bonding Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Layered | Clay montmorillonite (MMT), Graphene | 1-5 nm thickness, 100-500 nm diameter [24] | High aspect ratio (>50) enabling efficient stress transfer [24] | Ion-dipole bonding, physical adsorption, mechanical interlocking |

| 1D Fibrous | Carbon nanotubes (CNT) | Diameter: nanometers, Length: micrometers [24] | High axial strength (50-150 GPa) and modulus (1 TPa) [24] | Covalent functionalization, π-π stacking, van der Waals forces |

| 0D Spherical | Silica (SiO₂), Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | 25-35 nm diameter [25] [26] | Isotropic reinforcement, surface modification versatility | Covalent bonding (via silanes), hydrogen bonding, physical adsorption |

Experimental Protocols for Interface Engineering and Characterization

Protocol: Surface Modification of SiO₂ Nanoparticles Using GPTMS

This protocol describes the silanization of fumed silica nanoparticles with glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS) to enhance compatibility with epoxy resin systems, based on established methodology with demonstrated improvements in mechanical and bonding properties [25].

Materials and Equipment

- Fumed silica nanoparticles (primary particle size: 25-35 nm)

- Glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS)

- Absolute ethanol (99.98%)

- Acetic acid

- Deionized water

- Ultrasonic bath (frequency: 40 kHz)

- Centrifuge

- Vacuum oven

- Round-bottom flask with stirring capability

Step-by-Step Procedure

Calculate stoichiometric silane requirement using the established relationship [25]:

- ( m{GPTMS} = 6\frac{{M{GPTMS} \cdot m{sio2} \cdot n{OH} \cdot S{sio2} \cdot 10^{18} }}{{N{A} }} )

- Where ( m{GPTMS} ) and ( M{GPTMS} ) are the mass and molecular mass of GPTMS, ( m{sio2} ) is the mass of silica, ( n{OH} ) is the number of hydroxyl groups, ( S{sio2} ) is the specific surface area, and ( N{A} ) is Avogadro's number.

Prepare nanoparticle suspension:

- Disperse 0.5 g of fumed silica in 70 g of ethanol.

- Sonicate the suspension at 30°C for 1 hour to achieve preliminary de-agglomeration.

Hydrolyze the silane coupling agent:

- Prepare a solution of GPTMS in ethanol, with water and acetic acid at a weight ratio of 0.1:0.05 (GPTMS:water:acetic acid).

- Adjust to optimal pH (typically 4.5-5.5) as determined by zeta potential analysis.

Execute surface modification:

- Place the silica suspension in a round-bottom flask with continuous stirring.

- Add the hydrolyzed GPTMS solution dropwise over 30 minutes.

- Continue mixing for 4 hours at room temperature to complete the reaction.

Recover modified nanoparticles:

- Centrifuge the solution to separate functionalized nanoparticles.

- Wash sediments three times with acetone to remove unreacted silane.

- Dry in an oven at 90°C for 12 hours to complete condensation.

Verify grafting success through characterization techniques:

- FTIR: Look for epoxy group signatures (~910 cm⁻¹) and disappearance of silane methoxy groups.

- TGA: Quantify organic content through weight loss in controlled atmosphere.

- XPS: Confirm elemental composition changes indicating successful grafting.

Optimization Notes

For enhanced grafting ratios, testing silane concentrations at 1X, 5X, 10X, and 20X of the stoichiometric calculation (where X represents the stoichiometric concentration) is recommended. Research indicates optimal performance often occurs at 10X concentration [25].

Protocol: Fabrication and Characterization of Epoxy Nanocomposite Adhesives

This protocol outlines the preparation of silica-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites for structural bonding applications, specifically targeting enhanced concrete-steel rebar adhesion.

Materials and Equipment

- Epoxy resin system (e.g., Nanya NPEL-128 resin with Epikure F205 hardener)

- Pure or silanized silica nanoparticles (from Protocol 3.1)

- n-butanol (dispersion medium)

- Vacuum mixer

- Ultrasonic processor (200 W, 40 kHz)

- Testing molds (for tensile, compressive, and pull-test specimens)

- Curing oven

Nanocomposite Preparation Procedure

Disperse nanoparticles in resin:

- Add nanoparticles (0.5, 1, 3, or 5 wt%) to n-butanol.

- Sonicate at 28°C and 200 W for 1 hour to achieve homogeneous dispersion.

- Gently add the suspension to epoxy resin while mixing at 350 rpm for 30 minutes.

Remove solvent:

- Transfer the mixture to a vacuum oven to evaporate n-butanol.

- Apply slow rolling or mixing during this process to prevent settling.

Add curing agent and cast:

- Incorporate hardener at 1:2 weight ratio (hardener:resin) with gentle mixing to minimize air entrapment.

- Pour into pre-treated molds according to required specimen geometry.

Execute curing cycle:

- Allow initial solidification under ambient conditions for 10 hours.

- Perform post-curing at 100°C for 5 hours to maximize cross-linking.

Mechanical and Bonding Performance Assessment

Tensile testing:

- Conduct according to ASTM D638 using dog-bone specimens.

- Reported improvements: 56% increase in strength and 81% increase in modulus compared to pristine epoxy when using silanized nanoparticles [25].

Compressive testing:

- Perform according to ASTM D695 using cylindrical specimens.

- Documented enhancements: 200% improvement in compressive strength and 66% increase in compressive modulus versus unmodified epoxy [25].

Pullout testing for concrete-steel adhesion:

- Embed steel rebar in concrete blocks using nanocomposite adhesive.

- Test bond strength using standardized pullout apparatus.

- Recorded data: 40% improvement in pullout strength, 33% enhancement in displacement, and 130% increase in adhesion energy compared to pristine epoxy adhesive [25].

Microstructural characterization:

- Analyze fractured surfaces using FE-SEM to assess nanoparticle dispersion and failure mechanisms.

- Identify interfacial failure versus cohesive failure patterns.

Protocol: Direct Characterization of Bilayer Interfacial Regions

This advanced protocol utilizes scanning probe techniques to directly observe and characterize the bilayer interfacial structure in polar polymer nanocomposites, based on recently published methodology [26].

Materials and Specialized Equipment

- Polar polymer matrix (e.g., poly(vinylidene fluoride) - PVDF)

- Nanoparticles (e.g., TiO₂, BaTiO₃)

- Atomic force microscope with IR capability (AFM-IR)

- Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM)

- Scanning electron microscope

- Silicon wafer substrates

- Spin coater

Sample Preparation for Interface Detection

Create protruded nanoparticle configuration:

- Spin-coat a pure polymer layer onto silicon wafer to eliminate substrate effects.

- Prepare nanocomposite with controlled film thickness (t) less than nanoparticle diameter (D) to force nanoparticle protrusion.

- Optimize spin-coating parameters to achieve precise thickness control.

Identify interfacial regions:

- Use SEM and HADDF imaging to locate nanoparticles and observe bound polymer layer.

- Perform carbon mapping to identify regions with higher polymer density.

Interfacial Characterization Steps

Chemical mapping with AFM-IR:

- Acquire IR spectra at characteristic wavenumbers (e.g., 840 cm⁻¹ for polar TTTT conformation and 766 cm⁻¹ for non-polar TGTG conformation in PVDF).

- Map spatial distribution of polar and non-polar conformations around protruded nanoparticles.

- Measure thickness of interfacial regions showing predominant polar conformation.

Dipole orientation analysis with PFM:

- Perform lateral PFM measurements along x and y directions.

- Conduct vertical PFM to determine out-of-plane dipole components.

- Combine phase images to reconstruct three-dimensional dipole orientation.

Data interpretation:

- Identify inner bound layer (∼10 nm) with aligned dipoles perpendicular to nanoparticle surface.

- Measure outer polar layer (over 100 nm) with randomly oriented dipoles.

- Correlate interfacial structure with bulk property measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanocomposite Interface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silane Coupling Agents | Surface modification of hydrophilic nanofillers for compatibility with hydrophobic polymers | Bifunctional structure with organoreactive and hydrolysable groups | GPTMS for epoxy systems [25] |

| Fumed Silica Nanoparticles | Reinforcement filler for polymer matrices | High specific surface area, tunable surface chemistry | 25-35 nm primary particle size [25] |

| Polar Polymer Matrices | Matrix material for studying interfacial polarization effects | Strong molecular dipoles, responsive to external fields | PVDF and its copolymers [26] |

| Metal/Oxide Nanoparticles | Functional fillers for electrical, dielectric, or biological applications | High permittivity, catalytic activity, biocompatibility | TiO₂, BaTiO₃ for dielectric properties [26] |

| Carbonaceous Nanofillers | Reinforcement for electrical and thermal conductivity | High aspect ratio, exceptional mechanical properties | CNTs, graphene [24] |

| Clay Montmorillonite | Two-dimensional reinforcement for barrier and mechanical properties | High aspect ratio platelet structure, ion exchange capacity | Naturally occurring layered silicate [24] |

Visualization of Interfacial Structures and Processes

Bilayer Interfacial Structure Around Nanoparticle

Surface Modification and Nanocomposite Fabrication Workflow

The Role of Surface Functionalization for Biomedical Compatibility

Surface functionalization has emerged as a critical engineering strategy for transforming synthetic materials into biocompatible interfaces for advanced biomedical applications. Within the context of polymer nanocomposite fabrication, surface functionalization enables precise control over the interactions between nanomaterial interfaces and biological systems [27]. This process involves the deliberate modification of nanomaterial surfaces with specific chemical groups, polymers, or biomolecules to enhance their compatibility, functionality, and safety in biological environments [28].

The fundamental challenge in biomedical nanocomposite development lies in the inherent mismatch between synthetic material properties and biological system requirements. While nanomaterials such as metals, metal oxides, carbon-based structures, and MXenes offer exceptional electrical, mechanical, and functional properties, their native surfaces often exhibit poor biocompatibility, potential cytotoxicity, or undesirable immune responses [27] [29]. Surface functionalization bridges this critical gap by engineering bio-instructive interfaces that can modulate protein adsorption, cellular adhesion, immune recognition, and degradation profiles [28].

For researchers and drug development professionals working with polymer nanocomposites, mastering surface functionalization techniques is essential for developing innovative solutions in drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, biosensors, and implantable medical devices. This protocol details the methodologies, characterization techniques, and biocompatibility assessment required to ensure the successful translation of functionalized nanocomposites from laboratory research to clinical application.

Key Functionalization Strategies and Mechanisms

Chemical Functionalization Approaches

Table 1: Chemical Surface Functionalization Methods for Nanomaterials

| Method | Key Reagents | Mechanism | Resulting Surface Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silanization | APTES, Carboxyethylsilanetriol | Covalent grafting of organosilanes to surface hydroxyl groups | -NH₂ or -COOH groups; Controlled charge density [28] | Metal oxide NPs, Silica-based composites |

| Oxidation | HNO₃/H₂SO₄, H₂O₂ | Introduction of oxygen-containing groups via strong oxidizers | -COOH, -OH, -C=O groups; Negative surface charge [28] | Carbon nanotubes, Graphene, MXenes |

| Click Chemistry | Azides, Alkynes, Cu(I) catalysts | Bioorthogonal cycloaddition for specific ligand attachment | Site-specific functionalization; Controlled orientation [28] | Targeted drug delivery, Bioconjugation |

| Polymer Grafting | PEI, Chitosan, PAA, PSS | Physisorption or covalent attachment of charged polymers | Tunable charge; Multivalent binding sites; Enhanced stability [28] | DNA/RNA delivery, Protein adsorption |

Physicochemical Mechanisms of Biointeraction

Surface functionalization modulates biological responses through several fundamental mechanisms that govern nanomaterial-behavior interactions:

Electrostatic Interactions: Surface charge engineering enables selective adsorption of biomolecules through attraction between oppositely charged surfaces. The isoelectric point (pI) of target biomolecules and environmental pH critically determine interaction strength and specificity [28].

Steric Stabilization: Polymer coatings create physical barriers that prevent nonspecific protein adsorption and nanoparticle aggregation, thereby improving colloidal stability and circulation time in biological fluids [28].

Hydrogen Bonding and Specific Interactions: Functional groups such as hydroxyls, carboxyls, and amines form directional hydrogen bonds with biological counterparts, adding specificity to binding interactions [28].

Protein Corona Modulation: Engineered surfaces can control the composition and behavior of the hard and soft protein coronas that define biological identity and cellular responses [28].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Functionalization

Protocol 1: Amine Functionalization via Silanization

Purpose: To introduce amine groups onto metal oxide nanoparticles for enhanced adsorption of negatively charged biomolecules and improved biocompatibility.

Materials:

- Metal oxide nanoparticles (TiO₂, Fe₃O₄, SiO₂)

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)

- Anhydrous toluene

- Ethanol (absolute)

- Inert atmosphere glove box

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Pretreatment: Dry nanoparticles at 120°C for 12 hours to remove adsorbed water.

- Silanization Reaction:

- Prepare 5% (v/v) APTES solution in anhydrous toluene

- Add nanoparticles at 10 mg/mL concentration

- React under inert atmosphere with stirring for 24 hours at room temperature

- Purification:

- Centrifuge functionalized nanoparticles at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes

- Wash sequentially with toluene, ethanol, and deionized water (3 cycles each)

- Resuspend in desired buffer for characterization

- Validation:

- Confirm functionalization success using FTIR (characteristic peaks at 3300 cm⁻¹ and 1640 cm⁻¹)

- Quantify amine density via acid-base titration

Protocol 2: Polymer Coating for Electrostatic Enhancement

Purpose: To apply cationic polymer coatings for improved adsorption of anionic therapeutic biomolecules (DNA, RNA, proteins).

Materials:

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI, branched, MW 25,000)

- Nanoparticle suspension (1 mg/mL in DI water)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Centrifugal filters (100 kDa MWCO)

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve PEI in PBS to 2 mg/mL concentration

- Coating Process:

- Add PEI solution dropwise to nanoparticle suspension under vortex mixing (1:1 v/v)

- Incubate mixture for 1 hour with gentle agitation

- Purification:

- Remove unbound polymer using centrifugal filtration (3 cycles at 10,000 × g)

- Resuspend coated nanoparticles in storage buffer

- Quality Control:

- Measure zeta potential to confirm charge reversal to positive values

- Determine hydrodynamic size by dynamic light scattering

- Verify colloidal stability by monitoring aggregation over 72 hours

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Evaluation

The following workflow outlines the complete process for developing and evaluating surface-functionalized nanocomposites:

Workflow: Surface Functionalization Evaluation

Characterization Techniques for Functionalized Surfaces

Table 2: Characterization Methods for Surface-Functionalized Nanocomposites

| Technique | Parameters Measured | Functionalization Insights | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge, Colloidal stability | Successful charge modification, Stability prediction | Aqueous suspension, Dilute concentration |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Chemical bonds, Functional groups | Presence of specific moieties (-NH₂, -COOH) | Powder or KBr pellet |

| XPS | Elemental composition, Chemical state | Surface elemental analysis, Grafting confirmation | Dry powder, Vacuum compatible |

| TEM with EDS | Morphology, Elemental mapping | Particle size, Surface coating uniformity | Ultrathin sections, Grid-mounted |

| TGA | Weight loss with temperature | Grafting density, Thermal stability | 5-10 mg dry powder |

| DLS | Hydrodynamic size, PDI | Aggregation state, Stability in media | Dilute aqueous suspension |

Biocompatibility Assessment Protocols

Regulatory Framework and Essential Testing

Biocompatibility evaluation of surface-functionalized nanocomposites for medical devices follows the ISO 10993 series standards within a risk management framework [30] [31]. The assessment must consider the final finished form of the device, including all processing steps and potential interactions between components [30].

The "Big Three" biocompatibility tests required for nearly all medical devices include:

- Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

- Sensitization Assessment

- Irritation Testing [31]

Additional tests such as genotoxicity, systemic toxicity, hemocompatibility, and implantation studies may be required based on the device nature and intended use [31].

Protocol 3: Cytotoxicity Testing per ISO 10993-5

Purpose: To evaluate the potential toxic effects of leachables from surface-functionalized nanocomposites on mammalian cells.

Materials:

- L929 or Balb/3T3 fibroblast cells

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS

- Extract vehicles: serum-free media, saline, DMSO

- 96-well tissue culture plates

- MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide)

- ELISA plate reader

Procedure:

- Extract Preparation:

- Use 0.1 g/mL or 6 cm²/mL surface area ratio in extraction vehicle

- Incubate at 37°C for 24±2 hours with agitation

- Filter sterilize (0.22 μm) if necessary

- Cell Culture:

- Seed cells at 1×10⁴ cells/well in 96-well plates

- Incubate for 24 hours to achieve 80% confluency

- Extract Exposure:

- Replace medium with material extracts (100 μL/well)

- Include negative (HDPE) and positive (latex) controls

- Incubate for 24±2 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- Viability Assessment:

- Add MTT solution (10 μL of 5 mg/mL)

- Incubate 2-4 hours until formazan crystals form

- Dissolve crystals in acidified isopropanol (100 μL)

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm with 630 nm reference

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate cell viability: (ODsample/ODnegative control) × 100%

- Acceptable biocompatibility: ≥70% cell viability relative to negative control

Biocompatibility Testing Decision Framework

The appropriate biocompatibility testing regimen depends on the device's nature of body contact and contact duration:

Diagram: Biocompatibility Testing Strategy

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Functionalization Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling Agents | APTES, MPTMS, Silane-PEG | Covalent surface modification | Moisture sensitivity, Reaction pH dependence |

| Cationic Polymers | PEI, Chitosan, Poly-L-lysine | Positive charge introduction, Nucleic acid binding | Molecular weight effects, Charge density |

| Anionic Polymers | PAA, PSS, Heparin | Negative charge modulation, Antifouling | Concentration optimization, Coating stability |

| Characterization Kits | Zeta potential standards, MTT assay kits | Performance validation, Biocompatibility assessment | Storage conditions, Shelf life |

| Cell Culture Models | L929 fibroblasts, HUVECs, MSC | Biocompatibility screening, Functional assessment | Cell line relevance, Passage number effects |

Applications in Polymer Nanocomposites

Surface-functionalized nanocomposites enable advanced biomedical applications through tailored biointerfaces:

Drug Delivery Systems: Functionalized surfaces enhance electrostatic adsorption of therapeutic biomolecules while providing targeting capabilities and controlled release profiles [28].

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: Conductive polymer composites with appropriate surface chemistry support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation for neural, cardiac, and bone tissue regeneration [32].

Biosensors and Diagnostics: Precisely engineered surfaces improve biomarker binding specificity and signal-to-noise ratios in diagnostic applications [27] [32].

Antimicrobial Surfaces: Functionalization with antimicrobial nanoparticles (Ag, ZnO) or cationic polymers creates surfaces that resist microbial colonization while maintaining host compatibility [33].

The successful development of these applications requires iterative optimization of surface functionalization parameters based on comprehensive characterization and biological validation data.

From Lab to Clinic: Fabrication Techniques and Emerging Biomedical Applications

The development of polymer nanocomposites represents a significant advancement in materials science, combining a polymer matrix with nanoscale fillers to create materials with superior mechanical, thermal, electrical, and barrier properties. The performance of these nanocomposites is profoundly influenced by the dispersion state of the nanofillers within the polymer matrix, which is in turn governed by the fabrication method employed [34]. This article details the three principal fabrication techniques—solution casting, in situ polymerization, and melt blending—within the context of advanced research and development. It provides structured protocols, comparative data, and practical guidance tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in the field of polymer nanocomposites. Achieving a uniform dispersion of nanofillers is the central challenge in nanocomposite fabrication, as agglomeration can lead to defect sites and diminished properties [1]. The selection of an appropriate fabrication method is therefore critical to obtaining the full potential of property enhancements, balancing factors such as processing efficiency, filler compatibility, and final application requirements [5] [35].

Solution Casting

Solution casting is a foundational technique for fabricating polymer nanocomposites, particularly in laboratory settings. This method involves dispersing nanoparticles within a polymer solution, followed by casting and drying to form a solid film or sheet [35]. The core principle relies on using a solvent to reduce the polymer's viscosity and separate its chains, thereby facilitating the incorporation and dispersion of nanofillers through stirring or sonication. As the solvent is removed via evaporation or precipitation, the polymer structure re-forms, trapping the nanoparticles in place [36]. This method is highly regarded for its ability to achieve a good dispersion of nanofillers, especially for materials that are sensitive to high temperatures [34]. However, its drawbacks include the consumption of large amounts of solvents—some of which may be toxic—and the potential for nanofiller re-agglomeration if solvent removal occurs over a prolonged period [34] [37].

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer (e.g., Poly(vinyl alcohol) - PVA, Poly(lactic acid) - PLA)

- Nanofiller (e.g., Graphene Oxide - GO, Carbon Nanotubes - CNTs)

- Solvent (e.g., water, DMF, chloroform, xylene; the choice depends on polymer solubility)

- Magnetic stirrer or mechanical overhead stirrer

- Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator

- Casting dish (e.g., glass Petri dish)

- Oven or controlled environment for drying

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Polymer Solution: Dissolve a precise mass of the polymer in a suitable solvent with continuous mechanical stirring until a homogeneous solution is obtained. This may require several hours and controlled heating, depending on the polymer.

- Disperse Nanofiller: In a separate container, disperse a calculated mass of the nanofiller in the same solvent. Subject this mixture to ultrasonication (e.g., probe sonication at 400 W for 30 minutes) to break down agglomerates and create a stable suspension [36].

- Combine Mixtures: Gradually add the nanofiller suspension to the polymer solution under vigorous mechanical stirring. Continue stirring for several hours to ensure uniform mixing.

- Cast the Solution: Pour the final mixture into a clean casting dish, ensuring an even thickness across the substrate.

- Remove Solvent: Allow the solvent to evaporate in a controlled environment (e.g., in an oven at 40-50°C for 24-48 hours). Alternatively, induce precipitation by immersing the cast film in a non-solvent bath (e.g., methanol), followed by drying [34] [36].

- Post-Processing: Peel the resulting composite film from the dish and condition it before further testing or application.

Application Notes

Solution casting is particularly advantageous for processing thermally sensitive polymers and for creating thin films for applications such as gas-separation membranes [5], contact lenses [5], and electrochemical sensors [37]. The use of green solvents, such as Cyrene, has been recently explored to improve the environmental sustainability of this method [37]. A key challenge is preventing the re-aggregation of nanofillers during the solvent evaporation phase. Optimizing the solvent removal rate and using surfactants or functionalized nanoparticles can help mitigate this issue [34].

In Situ Polymerization

In situ polymerization involves the synthesis of a polymer from its monomer precursors in the direct presence of the nanofillers. This method is distinct as it does not involve pre-formed polymers [5] [34]. The monomers, being small molecules with low viscosity, can readily intercalate into the galleries of layered nanofillers or wet the surface of nanoparticles. Subsequent polymerization uses heat, radiation, or initiators to grow the polymer chains, effectively pushing the nanofiller layers apart (exfoliation) or grafting polymer chains onto the nanoparticle surfaces [5] [38]. This approach often results in a strong interfacial adhesion and a superior dispersion of the nanofiller, as the particles tend to nucleate and grow on the active sites of the developing macromolecular chains [34]. It is especially useful for polymers that are difficult to process by melting or dissolving and for fabricating nanocomposites with thermosetting matrices. A limitation is the potential for increasing viscosity during polymerization, which can complicate process control [34].

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer (e.g., ε-caprolactam, methyl methacrylate, styrene)

- Nanofiller (e.g., organically modified layered silicates [cation:1], multi-walled carbon nanotubes - MWCNTs [34])

- Polymerization initiator or catalyst (specific to the monomer system)

- Reaction vessel with temperature control and inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glove box)

- Mechanical stirrer

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Disperse Nanofiller in Monomer: Add the nanofiller to the liquid monomer. Use vigorous stirring and/or ultrasonication to achieve a homogeneous dispersion. For layered silicates, this step is crucial for monomer intercalation.

- Initiate Polymerization: Transfer the mixture to a reaction vessel. Introduce the catalyst or initiator and begin polymerization under a controlled atmosphere and temperature. For example, nylon 6/MWCNT nanocomposites can be synthesized via the in-situ polymerization of ε-caprolactam [34].

- Control Reaction Conditions: Maintain constant stirring and temperature throughout the reaction to ensure uniform heat and mass transfer and to prevent local gelation or agglomeration.

- Terminate and Recover: Once polymerization is complete, the resulting nanocomposite can be recovered as a solid block, which may be pelletized or powdered for subsequent processing steps like compression molding or extrusion.

Application Notes

In situ polymerization is widely used to create high-performance nanocomposites. A notable example is the synthesis of nylon 6/MWCNT nanocomposites, which exhibit an enhanced storage modulus and glass transition temperature [34]. This method is also pivotal in the intercalation method for creating polymer/clay nanocomposites, where the silicate layers must often be organically modified to be miscible with the monomer [5]. Furthermore, it enables the "in situ generation" of metal nanoparticles (e.g., silver, gold) directly on and within polymeric materials, which is highly valuable for creating textiles with strong, durable antimicrobial properties [34]. Researchers must carefully control parameters such as initiator concentration, temperature, and the presence of surface modifiers to manage the polymer's molecular weight and final properties.

Melt Blending

Melt blending, also known as melt compounding, is a versatile and industrially favored method for fabricating polymer nanocomposites. It involves the physical mixing of nanofillers with a molten polymer matrix under high shear forces, typically in an extruder or internal mixer [5] [35]. The process relies on elevated temperatures (above the polymer's melting or glass transition temperature) and mechanical shear to break apart nanofiller agglomerates and distribute them throughout the polymer melt [5]. The primary advantages of this method are its solvent-free nature, compatibility with standard industrial equipment like twin-screw extruders, and high throughput [5] [34]. It is particularly suitable for thermoplastics. A significant limitation, however, is the exposure of both the polymer and nanofiller to high temperatures, which can lead to thermal degradation. Furthermore, achieving exfoliation or a nanoscale dispersion can be more challenging compared to in-situ methods, as the high viscosity of polymer melts can resist the separation of nanofiller aggregates [5].

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer in pellet or powder form (e.g., Polyamide 12 - PA12, Isotactic Polypropylene - iPP, Polylactic acid - PLA)

- Nanofiller (e.g., Graphene, Organoclay, functionalized CNTs)

- Twin-screw extruder or internal mixer (e.g., Haake Rheomix)

- Granulator and injection molding machine (optional)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Dry Materials: Pre-dry the polymer pellets and nanofiller (if hygroscopic) in an oven to remove moisture, which can cause defects during processing.

- Pre-mix (Optional): Manually tumble-blend the polymer pellets with the nanofiller to create a rough premix, or use a masterbatch approach for better handling.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the mixture into a twin-screw extruder. The extruder zones should be set to a temperature profile that ensures complete melting of the polymer without degradation. High shear forces generated by the rotating screws are responsible for distributive and dispersive mixing.

- Example Parameters: For PET/clay nanocomposites, processing can be done at 265°C under a nitrogen atmosphere [34].

- Extrude and Pelletize: The homogenized melt is extruded through a die, cooled in a water bath, and pelletized into composite granules.

- Form Final Product: The pellets can be used to fabricate test specimens or final products using techniques like injection molding or compression molding.

Application Notes

Melt blending is extensively used in industries for the large-scale production of nanocomposites. For instance, well-dispersed, electrically conductive PA12/graphene nanocomposites with a low percolation threshold of 0.3 vol% have been prepared by melt mixing at 220°C [34]. Similarly, organoclay has been melt-compounded with a blend of iPP and PEO to impart optical transparency [34]. A key to success in melt blending is the use of functionalized nanofillers. For example, the use of hydroxyl-functionalized CNTs (MWCNT-OH) in PLA composites for melt mixing improves affinity with the polymer matrix, leading to better dispersion and enhanced electrical and mechanical properties [36].

Comparative Analysis of Fabrication Methods

The choice of fabrication method significantly impacts the final structure, properties, cost, and suitability of the polymer nanocomposite for specific applications. The following table provides a direct comparison of the three core methods.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of solution casting, in situ polymerization, and melt blending

| Feature | Solution Casting | In Situ Polymerization | Melt Blending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Dissolving polymer and dispersing filler in a solvent, then evaporating the solvent [35] | Polymerizing monomers in the presence of nanofillers [34] | Mixing nanofillers with a molten polymer under high shear [5] |

| Filler Dispersion | Good, but prone to re-agglomeration during drying [34] | Typically excellent; strong interfacial adhesion [34] | Good to moderate; depends highly on shear force and compatibility [5] |

| Process Complexity | Relatively simple, but time-consuming | Complex; requires control over chemical reactions [34] | Industrially robust and efficient [5] |