From Atom to Glass: Advanced Forcefield Parameterization for Accurate Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Predictions in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for computational researchers on the critical role of forcefield parameter optimization for simulating the glass transition temperature (Tg) of amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) and...

From Atom to Glass: Advanced Forcefield Parameterization for Accurate Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Predictions in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for computational researchers on the critical role of forcefield parameter optimization for simulating the glass transition temperature (Tg) of amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) and other pharmaceutical materials. We explore the foundational theory linking molecular interactions to Tg, detail cutting-edge parameterization and simulation methodologies, address common pitfalls in calibration and convergence, and establish robust validation frameworks against experimental data. By synthesizing these four intents, this guide aims to enhance the predictive power of molecular dynamics simulations for rational drug formulation and stability assessment.

The Science Behind Tg: Understanding the Link Between Molecular Interactions and the Glass Transition

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My simulated Tg value is consistently 20-30K higher than the experimental DSC data. What forcefield parameters are most likely the cause?

A: This common discrepancy often originates from inaccuracies in torsional potential parameters or van der Waals (vdW) interactions. Focus on:

- Torsional Dihedral Parameters: The energy barriers for intramolecular rotation are frequently overestimated in generic forcefields (e.g., GAFF). Use quantum mechanical (QM) calculations to refine dihedral parameters for your specific drug molecule's rotatable bonds.

- vdW *ε (well-depth) Parameters:* Overly strong non-bonded interactions can artificially increase Tg. Consider systematic scaling of ε for specific atom types (like aromatic carbons or heteroatoms) and validate against QM-derived interaction energies for molecular dimers.

- Protocol for Parameter Refinement:

- QM Target Data Generation: Perform DFT calculations (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) to obtain torsion energy profiles for all key dihedrals and interaction energies for molecular dimer conformations.

- Forcefield Optimization: Use a parameter optimization tool (e.g.,

foyerorparmed) to adjust dihedral coefficients and vdW parameters to minimize the difference between forcefield and QM energies. - Validation Simulation: Run a new Tg simulation (see protocol below) with the refined parameters.

Q2: During cooling rate simulations, my amorphous system crystallizes before reaching Tg. How can I prevent this?

A: Unphysical crystallization indicates that the forcefield may over-stabilize the crystalline form or that the simulated cooling rate is still too slow.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Increase the Cooling Rate: While experimentally unrealistic, simulate a faster quench (e.g., 100 K/ns instead of 10 K/ns) to bypass the crystallization event. The goal is to obtain an amorphous glass for analysis.

- Check Crystal Structure Stability: Simulate the known crystal structure (from CSD) at 300K. If it does not melt or distort, your vdW or electrostatic parameters may be too strong, over-stabilizing the lattice. Consider refining partial charges via the RESP method.

- Amorphization Protocol: Start from a high-temperature (e.g., 500K) molten state, then use a very fast quench (500 K/ns) to 300K to generate your initial amorphous configuration.

Q3: How do I accurately calculate Tg from my molecular dynamics (MD) simulation trajectory, and why do different properties yield different values?

A: Tg is identified by a change in the slope of a temperature-dependent property. The variance arises from different properties' sensitivity to dynamical vs. volumetric transitions.

- Recommended Protocol:

- Simulation Run: Start with an equilibrated amorphous system at high temperature (e.g., 50K above expected Tg).

- Cooling Stage: Use the NPT ensemble (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman barostat) to cool the system in stages (e.g., 10-20K decrements). Equilibrate for 2-5 ns at each temperature, then produce a 5-10 ns production run.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the following for each temperature:

- Specific Volume (or Density)

- Enthalpy (H = U + PV)

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) or diffusion coefficient.

- Fitting: Plot property vs. T. Fit linear regressions to the high-T (ruby state) and low-T (glassy state) data. Tg is the intersection point.

Table 1: Tg Values from Different Simulation Properties

| System (Model API) | Cooling Rate (K/ns) | Tg from Specific Volume (K) | Tg from Enthalpy (K) | Tg from Diffusion Crossover (K) | Experimental DSC (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin (GAFF) | 10 | 328 | 331 | 319 | 315 |

| Felodipine (GAFF2) | 20 | 302 | 305 | 291 | 297 |

| Indomethacin (Refined FF) | 10 | 317 | 319 | 312 | 315 |

Q4: What is the most reliable experimental protocol to validate my simulated Tg?

A: Use Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (mDSC).

- Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare 3-5 mg of the amorphous drug. Generate it via melt-quenching (heat 20K above melting point, cool in liquid N₂) or spray drying.

- mDSC Run: Load sample in a hermetic Tzero pan. Perform a heat-cool-heat cycle under N₂ purge.

- Method:

- Equilibration at 0°C.

- First Heat: 0°C to 150°C at 2°C/min, modulation ±0.5°C every 60s.

- Cooling: 150°C to 0°C at 5°C/min (unmodulated).

- Second Heat: Identical to first heat.

- Analysis: Analyze the reversing heat flow signal from the second heating ramp. Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step transition. This minimizes confounding effects from enthalpy relaxation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Tg Simulation & Validation

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity API (>99%) | Essential for both experimental DSC and for building accurate simulation models without impurity effects. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, LAMMPS) | Engine for running the cooling simulations. GROMACS is recommended for its efficiency in temperature equilibration. |

| Forcefield Parameterization Tool (foyer, parmed) | Used to apply or refine forcefield parameters (dihedrals, vdW) for the drug molecule. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (Gaussian, ORCA) | Generates target data (torsion scans, dimer energies) for forcefield refinement. |

| Modulated DSC (mDSC) Instrument | Gold-standard for experimental Tg measurement, separates reversing heat flow from kinetic events. |

| Hermetic Aluminum DSC Pans | Prevents sample dehydration or degradation during the mDSC scan, crucial for accurate Tg. |

| Spray Dryer (e.g., Buchi Mini B-290) | Alternative method to produce amorphous solid dispersions for stability and solubility experiments. |

| Vapor Sorption Analyzer (DVS Intrinsic) | Measures moisture-induced Tg depression (plasticization), a key stability factor to simulate. |

Visualizations

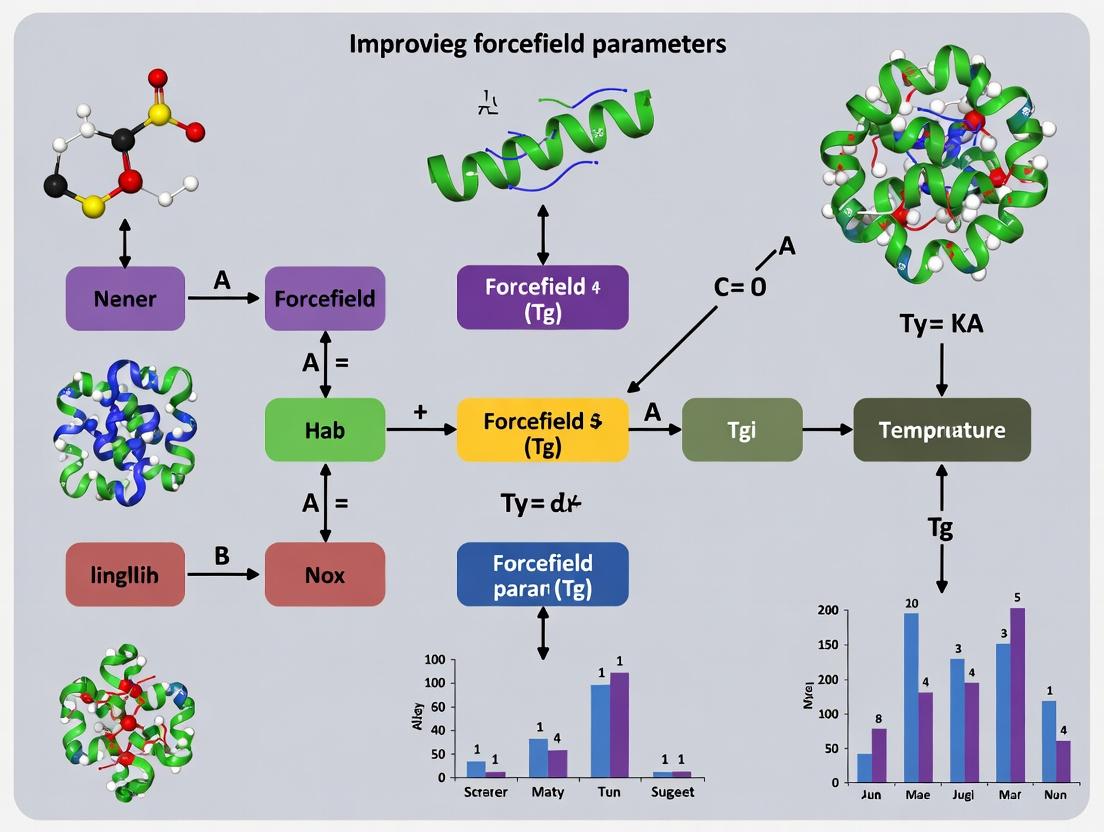

Tg Simulation & Forcefield Refinement Workflow

Tg Definition & Link to Product Performance

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulated Tg is consistently lower/higher than experimental Tg.

- Possible Cause: Inadequate torsional parameters for backbone or sidechain dihedrals, leading to under/over estimation of energy barriers to rotation.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform a dihedral parameter scan using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations on representative fragments.

- Compare the QM energy profile with the forcefield energy profile for the same dihedral.

- Refit the torsional parameters (V1, V2, V3 phases) to match the QM energy barrier heights and minima.

- Re-run the Tg simulation protocol with the refined parameters.

- Validation: Calculate the backbone dihedral angle distributions (Ramachandran plots) before and after parameter refinement to ensure they match ab initio MD or crystal structure data.

Issue 2: Density of the amorphous cell is incorrect, affecting volumetric properties.

- Possible Cause: Incorrect Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters (sigma, epsilon) for van der Waals interactions, or unbalanced partial atomic charges.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Calculate the cohesive energy density (CED) from simulation and compare to experimental estimates.

- Perform liquid-state property simulations (e.g., density, enthalpy of vaporization) for small molecule analogs of polymer repeat units or the system of interest.

- Iteratively adjust LJ parameters (prioritizing epsilon) to match target liquid densities and enthalpies of vaporization within a 5% error margin.

- Re-evaluate partial charges using a consistent method (e.g., RESP fitting) at an appropriate QM theory level.

- Validation: Run a new NPT ensemble simulation for the bulk system and compare the final density trajectory average to the experimental value.

Issue 3: System dynamics are too fast/slow, evidenced by incorrect diffusion coefficients or relaxation times.

- Possible Cause: Friction or inertial effects are off due to improper coupling to a thermostat/barostat, but more fundamentally, the overall energy landscape is scaled incorrectly due to forcefield limitations.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify thermostat/barostat coupling constants (taut, taup) are set appropriately for the system size (typically 0.1-1.0 ps).

- Calculate the mean squared displacement (MSD) of backbone or center-of-mass atoms. If dynamics are uniformly skewed, the issue is likely fundamental forcefield parameters.

- Benchmark short-time dynamical properties (e.g., dielectric relaxation) against experimental data.

- Consider if the non-bonded interaction cut-off is handled correctly (with long-range corrections) to avoid artifacts.

- Validation: Compare the simulated viscosity (from Green-Kubo relation or Einstein relation) or diffusion constant to experimental NMR or light scattering data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most sensitive forcefield parameter for Tg prediction in polymers? A1: Torsional (dihedral) parameters are often the most sensitive for Tg prediction. Tg is linked to segmental mobility, which is governed by the energy barriers to internal rotation. Inaccurate dihedral potentials directly skew the temperature dependence of dynamics.

Q2: How much deviation between simulated and experimental Tg is considered acceptable? A2: There is no universal standard, but a common benchmark in recent literature is to aim for a deviation within ±10-20 K. However, the goal should be systematic improvement to minimize this error, as it indicates the forcefield's ability to capture the true energy landscape.

Q3: Should I refit all parameters or just a specific set? A3: Start with a targeted approach. Refit torsional parameters for the rotatable bonds most critical to glass formation first. Then, if necessary, adjust LJ parameters for key atom types to correct volumetric properties. A full reparameterization is a major undertaking requiring extensive QM and liquid-state data.

Q4: What is the minimum simulation time and system size needed for a reliable Tg estimate? A4: This is system-dependent. As a rule of thumb, use >100 repeat units for linear polymers and simulate for at least 50-100 ns of production MD after equilibration. The cooling rate in the simulation is also critical; typical computational rates are 0.1-1 K/ns, much faster than experiment.

Q5: How do I choose the right QM method for parameter refitting? A5: Use a method that balances accuracy and cost. For organic molecules and polymers, DFT methods like B3LYP with a 6-31G(d) basis set are a common starting point. Higher-level methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T)) can be used for validation on smaller fragments.

Table 1: Common Forcefield Parameter Deficiencies and Their Impact on Tg Simulations

| Deficiency | Affected Property | Typical Symptom in Tg Simulation | Primary Correction Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Torsional Barriers | Segmental Dynamics | Tg too low, dynamics too fast | QM-guided dihedral refitting |

| Strong Torsional Barriers | Segmental Dynamics | Tg too high, dynamics too slow | QM-guided dihedral refitting |

| Underestimated LJ Attraction (epsilon) | Cohesive Energy Density | Density too low, Tg often too low | Match to liquid density & ΔHvap |

| Overestimated LJ Attraction (epsilon) | Cohesive Energy Density | Density too high, Tg often too high | Match to liquid density & ΔHvap |

| Incorrect Partial Charges | Intermolecular Interactions | Erroneous dielectric response, skewed polarity | Consistent charge derivation (e.g., RESP) |

Table 2: Benchmarking Data for Polystyrene Tg Simulation (Example)

| Forcefield | Simulated Tg (K) | Experimental Tg (K) | Error (K) | Density at 300K (g/cm³) | Ref Cooling Rate (K/ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF (Original) | 325 ± 5 | 373 | -48 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 1.0 |

| OPLS-AA | 370 ± 7 | 373 | -3 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 1.0 |

| Refined TraPPE | 375 ± 5 | 373 | +2 | 1.05 ± 0.01 | 1.0 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: QM-Driven Torsional Parameter Refinement

- Fragment Selection: Isolate a molecular fragment containing the rotatable bond of interest (e.g., a dimer for a polymer backbone dihedral).

- QM Geometry Optimization: Optimize the fragment geometry at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.

- QM Energy Scan: Perform a relaxed potential energy surface scan by rotating the dihedral angle in 10-15° increments. At each step, re-optimize all other degrees of freedom.

- Energy Fitting: Fit the classical forcefield dihedral equation (V1[1+cos(φ)] + V2[1-cos(2φ)] + V3[1+cos(3φ)]...) to the QM energy profile using a least-squares fitting procedure.

- Validation: Test the new parameters on a small oligomer in the gas phase to ensure they reproduce the QM conformational preferences.

Protocol 2: Tg Determination via Cooling Simulation

- System Preparation: Build an amorphous cell with at least 100 chains, each with sufficient degree of polymerization (e.g., 50-100 monomers). Use periodic boundary conditions.

- Equilibration: Perform a multi-step equilibration:

- Energy minimization (steepest descent, conjugate gradient).

- NVT equilibration at high temperature (e.g., 500 K) for 1-5 ns.

- NPT equilibration at high temperature for 5-10 ns to stabilize density.

- Production Cooling: Using the NPT ensemble, cool the system linearly from high temperature to low temperature (e.g., 500 K to 200 K) at a constant rate (e.g., 0.5 K/ns). Save trajectory frames frequently.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the specific volume (or density) for each temperature from the trajectory. Fit the high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) data with linear regressions. The intersection point of the two lines defines the simulated Tg.

Visualization: Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Tg Forcefield Refinement Workflow

Dihedral Energy Barrier Impact on Dynamics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg/Forcefield Research |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS) | Performs ab initio or DFT calculations to generate target data (energy scans, partial charges, dipole moments) for forcefield parameterization. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS, AMBER, OpenMM) | Simulates the cooling, equilibration, and production runs for Tg calculation and property prediction using classical forcefields. |

| Forcefield Parameterization Tool (e.g., ForceBalance, Paramecium, ffTK) | Assists in the systematic optimization of forcefield parameters to match quantum mechanical and experimental target data. |

| Polymer Builder & Amorphous Cell Generator (e.g., PACKMOL, Moltemplate, Materials Studio) | Creates realistic initial configurations of bulk polymer systems for simulation, ensuring proper chain packing and periodicity. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite (e.g., MDAnalysis, VMD, MDTraj) | Analyzes simulation outputs to calculate key properties: density, radius of gyration, mean squared displacement (MSD), dihedral distributions, and volumetric temperature dependence for Tg. |

| Benchmark Experimental Data (e.g., NIST TRC Data, Polymer Handbook) | Provides reliable experimental Tg, density, and thermodynamic data for specific polymers, serving as the essential ground truth for forcefield validation and refinement. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My simulated glass transition temperature (Tg) for a polymer is consistently 20-30K lower than the experimental value. Which force field parameters should I prioritize for refinement?

- Answer: A systematically low Tg often points to an underestimation of backbone torsional energy barriers or insufficient van der Waals (vdW) repulsion, allowing chains to collapse too easily. Prioritize:

- Torsional Dihedrals: Use quantum mechanics (QM) scans of model compounds (e.g., dimer or trimer) to recalibrate the dihedral parameters (V1, V2, V3) for the polymer backbone. Increasing these barriers raises the energy cost for segmental rotation.

- Van der Waals (vdW) Repulsion: Check the Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters for key atom types. Slightly increasing the repulsive term (ε or σ) for backbone atoms can reduce excess free volume and raise Tg. Validate against QM-calculated conformational energies and crystal structures if available.

FAQ 2: During API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) dissolution simulation, I observe unrealistic aggregation or premature crystallization. What non-bonded interaction could be the culprit?

- Answer: This is typically a sign of inaccurate electrostatic or vdW interactions between API molecules and solvent (often water).

- Electrostatics: Ensure partial atomic charges (e.g., from RESP/HF/6-31G* or similar) accurately represent the molecular electrostatic potential (ESP) of the API. Incorrect charges distort solute-solvent hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions. Consider using a polarizable force field or adjusting charge scaling if using a fixed-charge model.

- vdW Cross-Terms: The combination rules (e.g., Lorentz-Berthelot) for API-water vW interactions may be inadequate. Use QM dimer interaction energies (e.g., from SAPT) to refine specific LJ cross-term parameters (σij, εij).

FAQ 3: How can I systematically parameterize a new torsion angle for a specific functional group in my API?

- Answer: Follow this QM-to-MM protocol:

- Model Compound Selection: Choose a small molecule fragment containing the torsion of interest, with capped terminals (e.g., methyl groups) to isolate the effect.

- QM Conformational Scan: Perform a relaxed potential energy surface (PES) scan by rotating the dihedral in 10-15° increments at a high theory level (e.g., B3LYP/6-311+G or MP2/cc-pVTZ). Include geometry optimization at each step.

- MM Parameter Fitting: In your simulation software (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, GROMACS), set up an identical torsion scan using initial force field guesses.

- Optimization: Iteratively adjust the torsional force constants (Vn) and phase shifts (γ) in the MM potential energy function (E_tors = Σ [Vn/2] [1 + cos(nφ - γ)]) to minimize the RMSD between the QM and MM PES curves.

FAQ 4: When simulating polymer-drug blends, the components phase separate too rapidly or not at all. How do I diagnose the issue?

- Answer: This indicates a mismatch in the cohesive energy density, driven by vdW and electrostatic interactions.

- Check Mixing Enthalpy: Calculate the enthalpy of mixing (ΔHmix) from short simulations. A large, unrealistic positive value suggests overly repulsive cross-interactions.

- Refine Cross-interaction vdW Parameters: Use the experimental blend morphology (homogeneous vs. phase-separated) as a target. Adjust the LJ cross-term parameters (εij) between key polymer and API atom types using a free energy perturbation (FEP) or iterative Boltzmann inversion (IBI) approach to match observed miscibility.

- Verify Electrostatic Complementarity: Ensure the charge distributions on the polymer and API allow for favorable intermolecular interactions (e.g., H-bonding, dipole alignment) if expected.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Force Field Parameter Deficiencies and Their Impact on Tg Prediction

| Deficiency | Typical Effect on Simulated Tg | Primary Correction Method | Target Accuracy (vs. Expt.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underestimated Backbone Torsional Barrier | Tg too Low (>15K error) | QM PES Scan Refinement of V1, V2, V3 | ±5 K |

| Overly Lennard-Jones Attractive vdW | Tg too Low | Increase repulsive ε/σ for backbone atoms; match QM dimer profiles | ±5 K |

| Inaccurate Partial Atomic Charges | Unpredictable Tg shift | Re-derive charges to fit QM ESP (e.g., RESP) | ±10 K |

| Incorrect Bond/Angle Stiffness | Affects thermal expansion | Refine via QM vibrational frequencies | ±7 K |

Table 2: Recommended QM Methods for Parameterization Input Data

| Target Interaction | Recommended QM Level | Primary Output for Fitting | Validation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torsional PES | B3LYP-D3/6-311+G(d,p) or MP2/cc-pVTZ | Dihedral Energy Profile | RMSD < 0.5 kcal/mol |

| Non-bonded Dimer | ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP or SAPT2+/aug-cc-pVTZ | Interaction Energy vs. Distance | RMSD < 0.3 kcal/mol |

| Electrostatic Potential | HF/6-31G* (for RESP) | Grid-Based ESP | R^2 > 0.99 |

| Crystal/Lattice | PBE-D3(BJ) | Unit Cell Parameters, Cohesive Energy | Density error < 2% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: QM-Driven Torsional Parameter Refinement for a Polymer Backbone

- Model Preparation: Construct a chemical dimer of the polymer repeat unit, capping the terminal bonds with methyl groups (or other appropriate capping atoms).

- QM Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize the geometry of the model compound at the HF/6-31G* level to obtain a stable starting conformation.

- PES Scan: Perform a relaxed rotational scan for the central dihedral angle of interest. Use the B3LYP-D3/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Constrain the target dihedral in 15° increments from 0° to 360°, allowing all other coordinates to relax at each step.

- Energy Processing: Extract the single-point energy at each step. Reference all energies to the global minimum (set to 0 kcal/mol).

- MM Scan Setup: Recreate the identical model compound in your molecular dynamics suite. Apply the initial force field parameters.

- Fitting: Using a scripting tool (e.g.,

parmedorcharmm), perform a least-squares fitting of the torsional force constants (Vn) in the MM equation to minimize the difference between the QM and MM energy profiles. The phase shifts (γ) are typically fixed at 0° or 180°.

Protocol B: Validating vdW Parameters via Crystal Structure Prediction

- System Selection: Choose a small molecule API or polymer repeat unit with a known, stable crystal structure from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD).

- Force Field Assignment: Apply the candidate force field parameters to the molecule.

- Crystal Simulation: Build the experimental crystal unit cell in the simulation software. Run a short (100 ps) NPT equilibration at the experimental temperature and pressure (e.g., 298 K, 1 atm).

- Data Collection: Over a subsequent 1 ns NPT production run, calculate the average unit cell parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) and density.

- Analysis: Compare simulated and experimental density and cell lengths. A robust parameter set should reproduce the experimental density within 1-2% and cell lengths within 3-5%. Significant deviations, especially systematic contraction/expansion, indicate need for vdW (and possibly electrostatic) recalibration.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for Tg Force Field Parameter Improvement

Diagram 2: Key Interactions Governing Polymer & API Behavior

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Force Field Parameterization

| Item | Function/Description | Example Software/Package |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Performs electronic structure calculations to generate target data (PES, ESP, dimer energies). | Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4, GAMESS |

| Force Field Development Suite | Fits MM parameters to QM data and manages parameter files. | ForceFieldKit (FFTK), parmed, fftool, CHARMM/OpenMM |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Runs simulations with new parameters to test against macroscopic observables. | GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM |

| Automation & Scripting Tool | Automates repetitive tasks like batch simulations, data extraction, and fitting. | Python (MDAnalysis, mdtraj), Bash, Jupyter Notebooks |

| Validation Database | Provides experimental reference data for crystal structures, densities, and thermodynamic properties. | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), NIST ThermoML, PubChem |

| Visualization Software | Inspects molecular conformations, interactions, and simulation trajectories. | VMD, PyMol, ChimeraX |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: My simulated Tg is consistently 20-50K lower than the experimental value, regardless of the cooling rate I use. Which forcefield parameter is most likely the culprit? Answer: This systematic under-prediction is a well-documented issue, often traced to torsional parameters. Bonded terms, specifically the dihedral potentials governing backbone rotations, are the primary suspect. The energy barriers for rotations are frequently overestimated, making the polymer chains too flexible. You should first perform a torsional potential energy scan on your polymer's key dihedral angles using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations and compare the profiles to those produced by your forcefield. Refitting the dihedral parameters (specifically the k and n terms) to match the QM scan is the recommended correction. GAFF and early OPLS versions are particularly prone to this.

FAQ 2: During the density equilibration step before the cooling cycle, my amorphous cell collapses or shows unrealistic density fluctuations. What protocol adjustments can stabilize this phase? Answer: Unstable pre-cool equilibration typically indicates issues with the initial structure or the equilibration protocol. Follow this adjusted workflow:

- Initial Packing: Use a higher target density (e.g., +10-15%) than the expected final density to compensate for initial relaxation.

- Staged Minimization: Perform energy minimization in stages: first with only bonded terms, then with van der Waals (vdW), and finally with full electrostatics.

- Gentled NPT Equilibration: Use a stepwise, gentle NPT equilibration:

- 100 ps at high pressure (e.g., 1000 bar) and your simulation temperature (Tg + 100K).

- 100 ps at 500 bar.

- 500 ps at 1 bar, using a semi-isotropic pressure coupling for bulk systems.

- Thermostat/Barostat Choice: For CHARMM/CGenFF, use the Nosé-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat. For GAFF/OPLS, the Berendsen barostat (for equilibration only) followed by the Parrinello-Rahman barostat for production can be more stable.

FAQ 3: I observe "glass" formation at unexpectedly high temperatures during simulation, leading to an overestimation of Tg. Could this be a forcefield artifact related to nonbonded interactions? Answer: Yes, this is commonly an artifact of overly attractive nonbonded van der Waals (vdW) interactions, specifically the Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters. Overly deep LJ wells increase inter-chain cohesion, reducing chain mobility prematurely and artificially raising Tg. This is a known challenge in some older OPLS-AA parameter sets for certain polymers. To troubleshoot:

- Check the LJ 1-4 scaling rules. Different forcefields apply different scaling factors (e.g., OPLS uses 0.5, GAFF uses 0.5 for LJ but 0.8333 for electrostatic 1-4 interactions). Inconsistency here can cause rigidity.

- Consider using a modified vdW cutoff (e.g., 1.2-1.4 nm) with long-range dispersion corrections (e.g., energy and pressure tail corrections) to better account for long-range interactions. Disabling these corrections can sometimes lead to artificially high cohesion.

FAQ 4: How do I properly handle partial charge assignment for a novel drug-like molecule when using CGenFF or GAFF for Tg prediction of a polymer/drug composite? Answer: Accurate partial charges are critical for mixed systems. Follow this protocol:

- For CGenFF: Use the CGenFF program (server or standalone) to obtain initial charges. It provides a penalty score; aim for penalties < 50 for most atoms, and < 20 for key functional groups. For any penalty > 50, you must perform QM-based charge fitting (e.g., using the HF/6-31G* level) to refine the parameters, then submit them for incorporation into the stream file.

- For GAFF: Use the Antechamber suite with the AM1-BCC charge model (

antechamber -c bcc) as the standard. For higher accuracy, especially for conjugated systems, consider deriving restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) charges from an HF/6-31G* calculation usingresporMultiwfn. - Validation: Always calculate the dipole moment of your molecule from the QM optimization and compare it to the dipole moment derived from the assigned partial charges in the forcefield. A deviation > 20% warrants re-evaluation.

Table 1: Benchmarking Key Forcefields for Tg Prediction of Polystyrene (PS)

| Forcefield | Predicted Tg (K) | Experimental Ref (K) | Deviation (K) | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF2 | 340 - 360 | ~373 | -13 to -33 | Automated for organic molecules; good for blends. | Underestimates barriers; LJ parameters not polymer-optimized. |

| OPLS-AA | 390 - 410 | ~373 | +17 to +37 | Excellent for liquids & pure organics; validated. | Can overestimate cohesion; torsions may need refitting for polymers. |

| CHARMM36 | 365 - 380 | ~373 | -8 to +7 | Balanced bonded/nonbonded terms; robust for biopolymers. | Parameterization limited for many synthetic polymers. |

| CGenFF | 370 - 385 | ~373 | -3 to +12 | Consistent with CHARMM; good for drug-like molecules. | Similar polymer limitations as CHARMM; requires careful charge assignment. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function in Tg Simulation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Builder (e.g., Packmol) | Creates initial amorphous polymer cells with correct density and chain packing. | Ensure no overlapping atoms and periodic boundary continuity. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (Gaussian, ORCA) | Provides reference data for torsional scans & RESP charges for parameter derivation/validation. | Level of theory (e.g., HF/6-31G*) must match forcefield development. |

| MD Engine (GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS, OpenMM) | Performs the molecular dynamics simulation (equilibration, cooling, production). | Must support the specific forcefield format and all required algorithms. |

| VMD / PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualization of trajectories to check for structural anomalies, phase separation, or collapse. | Critical for qualitative validation before quantitative analysis. |

| Python/MATLAB with MD Analysis Libs (MDAnalysis, MDTraj) | For trajectory analysis: density vs. T, mean squared displacement (MSD), radial distribution function (g(r)). | Custom scripts are often needed for precise Tg calculation from V-T data. |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Tg Prediction via MD Simulation

- System Construction: Build an amorphous cell containing 10-20 polymer chains (degree of polymerization ~20-40) using packing software. For blends, ensure the correct mass/volume ratio.

- Parameterization: Assign forcefield parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals, LJ, charges). For non-standard molecules, derive/validate parameters via QM as per FAQ 4.

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient algorithms until force tolerance < 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- Stepwise Equilibration:

- NVT: Equilibrate for 1 ns at high temperature (e.g., 500 K) using a V-rescale thermostat.

- NPT: Equilibrate for 2-5 ns at 1 bar and the same high temperature using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Cooling Run: Using the equilibrated structure, run NPT simulations at successively lower temperatures (e.g., from 500 K to 200 K in 20-30 K increments). Simulate for 5-10 ns at each temperature to ensure equilibration (monitor density/time).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the average density for the last 2-3 ns at each temperature. Plot Density vs. Temperature. Fit two straight lines to the high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) data. The intersection point is the simulated Tg.

Visualization: Workflow for Forcefield Benchmarking & Tg Prediction

Diagram Title: Tg Prediction and Forcefield Refinement Workflow

Visualization: Forcefield Parameter Influence on Tg

Diagram Title: How Forcefield Parameters Influence Simulated Tg

A Step-by-Step Guide to Parameter Optimization for Enhanced Tg Simulation Accuracy

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQ 1: My QM geometry optimization fails to converge. What are the most common causes and solutions?

- Q: The optimization stops with "Maximum number of steps exceeded" or "Convergence failure."

- A: This is a frequent issue. Follow this protocol:

- Check Initial Geometry: Ensure your starting structure is reasonable (no unrealistic bond lengths/angles). Use a molecular builder or crystal structure.

- Method/Basis Set: The level of theory may be insufficient. Start with a robust method like B3LYP/6-31G(d) for organics. Increase basis set quality gradually.

- Step Size & Algorithm: Reduce the step size in the optimization routine. Switch optimization algorithms (e.g., from Berny to GEDIIS).

- Solvent Model: For charged or polar molecules, include an implicit solvent model (e.g., IEFPCM for water) from the start.

- Flat Potential Surfaces: For flexible molecules, consider performing a conformational search first, then optimize the lowest energy conformers.

FAQ 2: After deriving RESP charges, my MD simulation becomes unstable, with atoms flying apart. Why?

- Q: The simulation crashes with "Bond/Angle too large" errors shortly after energy minimization or dynamics start.

- A: This often indicates a charge derivation or parameter assignment issue.

- Charge Sum Validation: Ensure the sum of RESP charges for a neutral molecule is 0.000 ± 0.005. For ions, check the net charge.

- Missing Parameters: The derived charges may be assigned to atom types that lack bonded (bond, angle, dihedral) parameters in your chosen force field (e.g., GAFF2). Use tools like

antechamberandparmchk2to generate and inspect missing parameters. - Charge Restraint Strength: If you used strong restraints during RESP fitting to preserve symmetry or target values, the charges may be unnatural. Re-fit with weaker restraints (e.g., 0.0001 a.u.).

- Solvent Topology Mismatch: Verify that the water model used in MD (e.g., TIP3P) is compatible with the force field used for your solute.

FAQ 3: How do I validate the derived force field parameters before running long MD simulations for Tg prediction?

- Q: What are key validation calculations to ensure parameters are accurate and transferable?

- A: Implement this validation protocol:

- QM vs. MM Conformational Energy Comparison: Perform a relaxed potential energy surface scan for key dihedrals (e.g., rotatable bonds) at the QM level. Repeat the scan using the new MM parameters. Compare the profiles quantitatively (see Table 1).

- Liquid Property Simulation: For small molecule solvents, run a short (1-5 ns) NPT simulation to calculate density and enthalpy of vaporization. Compare to experimental values.

- Minimized Structure Comparison: Compare the MM-minimized structure (using new parameters) with the QM-optimized geometry. Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD).

Table 1: Sample QM vs. MM Dihedral Scan Validation Data for a Toluene Derivative

| Dihedral Angle (Center Atoms) | QM Energy Barrier (kcal/mol) | MM Energy Barrier (kcal/mol) | Difference (Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-C-C-C (Alkyl Chain) | 3.1 | 2.9 | +0.2 |

| C-C-O-C (Ether Linkage) | 10.5 | 11.2 | -0.7 |

| Ph-O-C (Aryl-Ether) | 2.0 | 1.8 | +0.2 |

Experimental Protocol: QM to MM Parameter Derivation for a Novel Monomer

- QM Geometry Optimization: Use Gaussian/GAMESS/ORCA. Method: B3LYP/6-31G(d). Implicit solvent: IEFPCM (solvent=water). Optimize to tight convergence criteria.

- Frequency Calculation: At the same level of theory to confirm a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and obtain the Hessian.

- Electrostatic Potential (ESP) Calculation: Generate a high-quality ESP grid around the optimized molecule (e.g., using

Pop=MKorPop=ESPkeywords). - Charge Derivation: Use

antechamber(in AmberTools) orrespprogram. Input: QM log file. Perform a two-stage RESP fit with weak hyperbolic restraints (e.g., 0.0005 a.u.). - Bonded Parameter Assignment: Use

antechamberto assign GAFF2 atom types and generate a preliminary file. Useparmchk2to identify/generate missing force constants (bonds, angles, dihedrals) based on QM data. - Topology File Assembly: Combine the charge file and parameter file into a full topology file (e.g.,

.prmtopfor AMBER,.itpfor GROMACS) usingtleaporpdb2gmx. - Validation: Execute QM vs. MM conformational scans and liquid property tests as described in FAQ 3.

Workflow Diagram: From QM to MD for Tg Prediction

Title: Full QM to MD Workflow for Force Field Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software & Computational Tools for the Workflow

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian / ORCA / GAMESS | Quantum Chemistry Software | Perform QM calculations (optimization, frequency, ESP). |

| Antechamber / RESP | Parameterization Tool | Derive RESP charges and assign GAFF atom types. |

| Parmchk2 / MATCH | Parameterization Tool | Generate missing bonded parameters for force fields. |

| tLEaP (AmberTools) | MD Preprocessing | Assemble system topology, solvate, add ions. |

| GROMACS / OpenMM / NAMD | MD Engine | Run high-performance classical molecular dynamics simulations. |

| CP2K / VASP (for QM/MM) | Advanced QM/MM | Perform ab initio MD or QM/MM simulations for validation. |

| MDAnalysis / cpptraj | Analysis Library | Analyze MD trajectories (density, RMSD, energy plots). |

| Molten Salt Tg Database | Reference Data | Experimental Tg values for validation (e.g., NIST). |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During Quantum Mechanics (QM) data fitting, my derived partial charges result in unrealistic electrostatic potentials. What could be the cause and how do I resolve it? A: This often stems from an improper balance between fitting to the electrostatic potential (ESP) and maintaining molecular symmetry. Implement a restrained ESP (RESP) fitting protocol. Use a two-stage fit with hyperbolic restraint for heavy atoms and a weaker restraint for hydrogens. Ensure your QM calculation (e.g., at the HF/6-31G* level) uses a dense grid for the ESP map.

Q2: My simulated liquid density plateaus at a value 5-10% lower than the experimental target at 298 K, even after adjusting Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters. What steps should I take? A: First, verify your simulation protocol: Ensure an NPT ensemble with a reliable barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) is used, with a production run of at least 20 ns. If the protocol is correct, systematically adjust LJ parameters. Increase the atom's sigma (σ) parameter incrementally by 0.01 Å, as density is more sensitive to σ than epsilon (ε). Re-simulate and compare. See Table 1 for sensitivity analysis.

Q3: The calculated heat of vaporization (ΔHvap) is consistently overestimated across a series of analogous compounds. Which parameter set should be prioritized for adjustment? A: Overestimation of ΔHvap indicates insufficient intermolecular attraction in the liquid phase, often due to understated LJ well depth (ε) or insufficiently negative partial charges. Prioritize scaling the ε parameters for non-polar groups by up to 5%. For polar molecules, re-evaluate the charge derivation strategy. Ensure your QM reference data (for charges) and experimental ΔHvap are both at the same temperature (typically 298 K).

Q4: How do I manage parameter conflicts when fitting to multiple target properties (density & ΔHvap) simultaneously? A: Adopt a hierarchical, iterative optimization loop. First, obtain initial charges from QM. Then, optimize LJ parameters against liquid density alone. With the new LJ set, recalculate ΔHvap. If a discrepancy remains, make minimal, chemically-justifiable adjustments to charges (e.g., scaling within ±0.05 e) and iterate. Use a weighted objective function in automated fitting scripts to balance the influence of each property.

Q5: After parameter derivation, my Tg simulation trend across a polymer series does not match experiment. Where could the error be? A: Tg is sensitive to torsional barriers and non-bonded interactions. Ensure the torsional potentials around rotatable bonds are derived from high-level QM scans (e.g., MP2/cc-pVTZ) and are not over-fitted to single-molecule data. Cross-validate your final parameters by simulating a dimer or trimer to check for reasonable interaction energies and geometries not included in the original fit.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Sensitivity of Target Properties to Force Field Parameters

| Parameter Adjusted | Primary Effect on Density | Primary Effect on ΔHvap | Recommended Adjustment Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| LJ Sigma (σ) | High Sensitivity | Moderate Sensitivity | ± 0.01 - 0.02 Å |

| LJ Epsilon (ε) | Moderate Sensitivity | High Sensitivity | ± 1 - 3% |

| Partial Charge (q) | Low Sensitivity | Very High Sensitivity | ± 0.02 - 0.05 e |

| Torsional Barrier (Vn) | Negligible | Negligible (for small molecules) | Use QM scan data directly |

Table 2: Example Optimization Results for a Model Compound (e.g., Ethylbenzene)

| Iteration | σ_CH3 (Å) | ε_CH3 (kJ/mol) | qCaryl (e) | Sim. Density (g/cm³) | Sim. ΔHvap (kJ/mol) | Exp. Density (g/cm³) | Exp. ΔHvap (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (GAFF) | 3.40 | 0.46 | -0.12 | 0.855 | 39.5 | 0.867 | 42.6 |

| After LJ Fit | 3.48 | 0.45 | -0.12 | 0.866 | 41.8 | 0.867 | 42.6 |

| After Charge Refinement | 3.48 | 0.45 | -0.145 | 0.867 | 42.5 | 0.867 | 42.6 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Deriving Partial Charges from QM Electrostatic Potential

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecule's geometry at the HF/6-31G* theory level using Gaussian, ORCA, or similar software.

- ESP Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure to generate the electrostatic potential on a Connolly surface (e.g., using the

pop=espkeyword in Gaussian). - Charge Fitting: Use the RESP or AM1-BCC method (via

antechamberin AmberTools orsqmin Open Babel) to fit atomic charges, restraining symmetric atoms to equivalence. - Validation: Plot the QM-derived ESP versus the ESP generated by the fitted charges; the R² should be >0.95.

Protocol B: Iterative Refinement of LJ Parameters Using Liquid Simulations

- Initial Setup: Build a cubic box containing 100-200 molecules using Packmol. Assign initial parameters (e.g., from GAFF).

- Equilibration: Run a 5 ns NPT simulation at 298 K and 1 bar using a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostat (Parrinello-Rahman).

- Production: Run a 20 ns NPT simulation, logging the density every 1 ps.

- Analysis: Calculate the average density over the last 15 ns. Compare to experimental value.

- Adjustment & Loop: Adjust σ for the atom contributing to the largest van der Waals volume by +0.01 Å if density is low (or vice versa). Return to Step 2. Iterate until within ±0.5% of experimental density.

Protocol C: Calculating Heat of Vaporization from Molecular Dynamics

- Liquid Phase Energy: From the final NPT liquid simulation (Protocol B), calculate the average potential energy per molecule (

E_liquid) from the last 15 ns of trajectory, excluding kinetic energy terms. - Gas Phase Energy: Simulate a single, isolated molecule in a large box. Run a 1 ns NVT simulation at 298 K. Calculate the average potential energy per molecule (

E_gas). - Compute ΔHvap: Apply the formula: ΔHvap = -(

E_liquid-E_gas) + RT, where R is the gas constant and T is 298 K. TheRTterm accounts for the PV work difference. - Error Calculation: Compare to the experimental ΔHvap. A systematic error >2 kJ/mol suggests a need for re-parameterization of non-bonded interactions.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Force Field Parameter Derivation Workflow

Title: Resolving Multi-Property Parameter Conflicts

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Derivation

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4) | Performs ab initio or DFT calculations to generate reference data (geometries, electrostatic potentials, torsional scans) for force field fitting. |

| Force Field Parameterization Tools (e.g., antechamber/AmberTools, fftk, LigParGen) | Automates the fitting of charges (RESP, AM1-BCC) and assists in generating initial LJ parameters from atom types. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, OpenMM, LAMMPS) | Simulates bulk liquid and gas phase systems to compute target properties (density, ΔHvap) for iterative parameter optimization. |

| System Builder (e.g., Packmol, PACKMOL-Memgen) | Creates initial simulation boxes with correct numbers of molecules and periodic boundary conditions for liquid simulations. |

| Analysis Scripts (Custom Python/MATLAB for ΔHvap, density) | Extracts and averages thermodynamic properties from simulation trajectories; crucial for calculating objective function values. |

| Experimental Data Repository (NIST ThermoML, DIPPR) | Provides reliable, peer-reviewed experimental data for liquid densities and enthalpies of vaporization as fitting benchmarks. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Training Failure of a Neural Network Potential (NNP)

- Symptoms: Loss function plateaus or diverges during training; poor energy/force predictions on validation set.

- Diagnosis: Check data quality, network architecture, and learning rate.

- Resolution: Ensure training data spans the relevant configurational space. Reduce learning rate or implement learning rate schedulers. Use a more suitable network architecture (e.g., shift from Behler-Parrinello to equivariant network for complex systems).

Issue 2: Automated Parameterization Tool Produces Unphysical Parameters

- Symptoms: Simulation instability (crashes), unrealistic bond lengths/angles, or grossly inaccurate property predictions (e.g., density).

- Diagnosis: Target property weights in the objective function may be imbalanced or reference data may be inconsistent.

- Resolution: Re-expertise the training set of quantum mechanics (QM) data for outliers. Adjust weights in the optimization function to prioritize critical properties like conformational energies. Implement parameter boundaries based on chemical intuition.

Issue 3: Poor Transferability of ML Potentials

- Symptoms: Potential works well for training data regimes but fails catastrophically for new molecular species or phases.

- Diagnosis: The MLP model lacks essential physical constraints and was trained on a narrow dataset.

- Resolution: Incorporate physical constraints (e.g., long-range electrostatics, dispersion corrections). Use active learning or adversarial sampling to iteratively expand the training dataset to cover new regions of interest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose between a classical force field and an ML potential for my Tg simulation? A: The choice depends on system size, time scale, and required accuracy. Use the decision table below.

Q2: My automated parameterization run is computationally expensive. How can I optimize it? A: Employ a multi-stage optimization: first optimize bonded parameters against simple QM data (torsion scans), then optimize partial charges and non-bonded terms against condensed-phase properties. Use efficient sampling algorithms and parallel computing.

Q3: How can I validate my newly parameterized force field before running long Tg simulations? A: Always run a battery of short validation simulations. Compare results to benchmark data as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Parameterization Approaches for Polymer Tg Simulation

| Approach | Typical System Size | Time Scale | Tg Prediction Error (vs. Exp.) | Key Software/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF (GAFF) | 10^3 - 10^4 atoms | ~100 ns | 15-50 K | AMBER, GROMACS, LAMMPS |

| Classical FF (Optimized) | 10^3 - 10^4 atoms | ~100 ns | 5-20 K | ForceBalance, ParAMS, ffparaim |

| ML Potential (ANI, GAP) | 10^2 - 10^3 atoms | ~10 ns | 5-15 K | ASE, LAMMPS, QUIP |

| ML Potential (NequIP, MACE) | 10^2 - 10^3 atoms | ~10 ns | <10 K* | nequip, mace, allegro |

*Preliminary research; requires extensive training data.

Table 2: Essential Validation Suite for New Force Fields

| Property to Validate | Simulation Protocol | Target Accuracy | Purpose for Tg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformational Energies | Gas-phase DFT scans of dihedrals | < 1 kcal/mol | Correct chain flexibility |

| Density (Amorphous) | NPT ensemble, 300K, 100+ atoms | < 2% deviation | Reproduces packing |

| Cohesive Energy Density | NVT ensemble, calculation from energy | < 10% deviation | Affects thermal expansion |

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Cooling at 1-10 K/ns, >50 atoms | < 20 K deviation | Primary metric |

Experimental Protocol: Iterative Force Field Optimization for Tg

- Initial Data Generation: Perform DFT (e.g., ωB97X-D/6-31G*) calculations on representative molecular fragments to obtain target data: conformational energies, partial charges (via RESP), and torsional profiles.

- Automated Parameterization: Use a tool like

ForceBalance. Define an objective function weighting the QM data (step 1) and experimental densities/Tg values from literature. - Validation Simulation: Parameterize a small amorphous polymer cell (e.g., 20 chains, 50 monomers each). Run a fast cooling simulation (e.g., 500 K to 100 K at 10 K/ns) in LAMMPS or GROMACS to get a preliminary Tg.

- Iteration: If validation fails, adjust weights in the objective function or add more specific QM data (e.g., non-covalent interactions) and return to step 2.

- Production Tg Simulation: Using the optimized parameters, run a larger system with slower cooling rates (1-5 K/ns) with multiple replicates to obtain a statistically robust Tg value.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: MLP Development & Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Force Field Optimization Thesis Context

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Tg Research |

|---|---|---|

ForceBalance |

Software | Optimizes classical FF parameters against QM & exp. data via systematic least-squares. |

PARAMS (AMS) |

Software | Allows gradient-based optimization of FF parameters within the Amsterdam Modeling Suite. |

ANI-2x Potentials |

ML Potential | Provides accurate, ready-to-use ML potentials for organic molecules containing H,C,N,O. |

NequIP / MACE |

ML Potential Framework | Trains equivariant graph NN potentials with high data efficiency & accuracy. |

LAMMPS |

MD Engine | Performs production molecular dynamics simulations, compatible with many FF/MLP formats. |

Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) |

Python Library | Glue code for workflows: setting up calculations, training MLPs, and analyzing results. |

GPUMD |

MD Engine | Highly efficient MD engine designed specifically for machine-learned potentials. |

LibTorch |

Library | PyTorch C++ API; essential for deploying trained MLP models in MD codes like LAMMPS. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my simulated Tg values for PVP deviate significantly from experimental DSC data, even with widely used forcefields like GAFF or CHARMM? A: This is a central challenge in the field. The deviation often stems from inaccurate torsional potential parameters for the polymer backbone and side groups, and from insufficient representation of hydrogen bonding. The forcefield may not capture the specific conformational energetics of the pyrrolidone ring. Within the thesis context, this highlights the need for targeted reparameterization of dihedral terms and partial charges using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations on dimer or trimer fragments to improve agreement with experimental Tg.

Q2: During the cooling/heating cycle in MD, how do I determine when the system has reached equilibrium at each temperature step for Tg calculation? A: You must monitor both energy and density. A protocol is as follows: After a temperature change, run an NPT simulation until the system's potential energy and density plateau. Calculate the rolling average over the last 100-200 ps of the step. The system is equilibrated when the slope of this rolling average is statistically indistinguishable from zero (e.g., via linear regression). Insufficient equilibration is a major source of error in the specific heat or density vs. temperature plot.

Q3: My simulations of API-polymer dispersions show spontaneous phase separation, even for systems known to be miscible. What forcefield issue does this indicate? A: This typically indicates that the non-bonded interaction parameters (Lennard-Jones and Coulombic) between the API and polymer are too repulsive or not attractive enough. The forcefield likely overestimates the like-like interactions (API-API, polymer-polymer) over the unlike (API-polymer) interactions. This directly motivates the thesis work: improving cross-interaction parameters, often via fitting to QM-calculated interaction energies of model complexes or experimental mixing enthalpy data.

Q4: What is the recommended method to extract Tg from simulation data, and why does my V-T curve show two distinct kinks? A: The standard method is to perform a dual linear regression fit to the specific volume vs. temperature data from an NPT cooling simulation. The intersection point of the high-T (ruby/glassy) and low-T (glassy) linear fits defines Tg. Two distinct kinks often suggest:

- Insufficient system size or simulation time: The polymer chains are not fully relaxed.

- Poor equilibration: The system was not equilibrated properly at temperatures near the true Tg.

- Crystallization: For semi-crystalline polymers, the high-T kink may represent the melting point (Tm).

Q5: How can I validate my improved forcefield parameters beyond just matching a single experimental Tg value? A: A robust validation within the thesis should include comparison to multiple experimental observables. These can include:

- The density and thermal expansion coefficient at multiple temperatures.

- Radial distribution functions (RDFs) for key atom pairs (e.g., H-bond donors/acceptors).

- Chain conformation statistics (e.g., end-to-end distance, radius of gyration).

- Cohesive energy density.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Noise in Specific Volume vs. Temperature Data

- Possible Cause 1: Simulation time per temperature step is too short.

- Solution: Increase production run time at each temperature step (aim for >1-2 ns after equilibration). Use longer averaging windows.

- Possible Cause 2: System size is too small (short polymer chains, few chains).

- Solution: Increase the number of polymer chains and/or chain length to better represent bulk behavior. Monitor volume fluctuations relative to total volume.

Issue: Simulated Tg has an Unphysical Dependence on Cooling/Heating Rate

- Possible Cause: The simulation cooling/heating rate is far too high compared to experiment (typically 10^10 – 10^12 K/s in MD vs. 10 K/min in DSC).

- Solution: While a rate dependence is intrinsic to MD, you must ensure results are consistent across a small range of simulated rates. Perform simulations at 2-3 different cooling rates (e.g., 0.5, 1, and 2 K/ns) and extrapolate Tg to an "infinitely slow" rate using a logarithmic fit, if necessary for precise comparison.

Issue: Polymer Chain Collapses or Forms Unrealistic Conformations During Initial Packing

- Possible Cause: Poor initial configuration and/or overly aggressive energy minimization.

- Solution: Use a multi-step packing and equilibration protocol:

- Generate initial chains with a self-avoiding random walk.

- Use a simulated annealing cycle (e.g., heat to 1000 K and slowly cool) in a large box with low density to "melt" and randomize chains.

- Gradually compress the box to the target density using slow NPT steps with high pressure coupling time constants.

- Perform final, gentle energy minimization.

Data Tables

Table 1: Representative Experimental vs. Simulated Tg Values for Common Polymers

| Polymer | Common Forcefield | Typical Simulated Tg (K) | Typical Experimental Tg (K) | Common Deviation (K) | Primary Parameter Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP K30 | GAFF/GAFF2 | 420-450 | 435-445 | ±15 | Torsions (backbone, ring), Partial Charges |

| HPMC (DS~1.8) | CHARMM36 | 450-480 | 430-450 | +20 to +30 | Dihedrals (glycosidic linkage), Van der Waals (methoxy) |

| PVPVA64 | OPLS-AA | 360-380 | 375-385 | ±10 | Cross-interaction (VP/VA), Bonded terms |

Table 2: Key MD Simulation Parameters for Tg Calculation

| Parameter | Recommended Value/Range | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling/Heating Rate | 0.5 - 2 K/ns | Balance between computational cost and approximating quasi-equilibrium. |

| Temperature Steps | 5 - 10 K | Fine enough to accurately locate the intersection point. |

| Ensemble | NPT (Anisotropic) | Allows volume fluctuation to calculate density/specific volume. |

| Pressure | 1 atm (Berendsen/Parrinello-Rahman) | Standard condition for experimental comparison. |

| Production Run per Step | 2-5 ns (after equilibration) | Ensures sufficient sampling for averaging density/energy. |

| Thermostat/Barostat | Nosé-Hoover / Parrinello-Rahman | Robust, production-grade algorithms. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard MD Workflow for Tg Simulation of an Amorphous Polymer

- System Building: Construct a single polymer chain of target DP (e.g., 30-40 monomers) using a monomer library. Replicate chains to achieve target density (e.g., ~1.2 g/cm³ initial guess) in a 3D periodic box.

- Initial Minimization & Relaxation: Perform steepest descent minimization (5000 steps). Then, run a short NVT simulation (100 ps) at 700 K to randomize chains.

- Density Equilibration: Run a multi-step NPT simulation at 500 K (above expected Tg) for 5-10 ns, allowing the box dimensions to adjust to the equilibrium density.

- Cooling Cycle: Using the equilibrated structure from step 3 as the starting point, run sequential NPT simulations, decreasing the temperature in steps (e.g., from 500 K to 300 K in 10 K steps).

- Data Collection: At each temperature step, discard the first 1-2 ns for equilibration, then collect specific volume (or density) and potential energy every 10 ps for at least 2-3 ns.

- Analysis: Plot specific volume vs. temperature. Perform bilinear fit. The intersection is the simulated Tg.

Protocol 2: Parameterization of Improved Torsional Potentials for Thesis Research

- QM Target Data Generation: Select key dihedral angles in the polymer (e.g., backbone φ/ψ, sidechain χ). For each, perform a relaxed potential energy surface (PES) scan at the DFT level (e.g., B3LYP/6-311G) on a dimer model system.

- Forcefield Parameter Optimization: In the forcefield (e.g., GAFF), the torsional potential is typically V(φ) = Σ (kn/2) [1 + cos(nφ - δn)]. Use a least-squares fitting algorithm to optimize the Fourier coefficients (kn, δn) to reproduce the QM PES.

- Validation in Small Molecule Crystal Simulation: Apply the new parameters to simulate the crystal cell of a related small molecule (e.g., N-vinylpyrrolidone crystal for PVP). Compare simulated cell parameters and sublimation enthalpy with experimental data.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Tg Simulation & Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Forcefield Improvement Thesis Research Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Tg Simulation Research |

|---|---|

| Polymer/API Molecular Structure Files (e.g., .mol, .pdb) | The atomic starting point for building simulation systems. Accuracy is critical. |

| Forcefield Parameter Files (e.g., .frcmod, .str, .itp) | Define all bonded and non-bonded interaction potentials for the system. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Used to generate target data (PES scans, interaction energies) for forcefield parameterization. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS) | Core software for performing the energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD runs. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools (VMD, MDAnalysis, in-house scripts) | Used to process MD output, calculate properties (density, RDFs), and visualize results. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential computational resource for running long, multi-step MD simulations with large systems. |

Diagnosing and Solving Common Tg Simulation Errors: A Troubleshooting Handbook

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the primary indicators that my Tg simulation is producing unreliable results?

Answer: Three primary red flags indicate unreliable Tg simulation results:

- Systematic Tg Deviation: The simulated glass transition temperature (Tg) consistently deviates by more than 20-30 K from robust experimental benchmarks for a well-parameterized system.

- Unphysical Densities: The simulated density of the amorphous phase at 298 K falls outside the physically plausible range for organic glasses (typically 1.1 - 1.4 g/cm³ for most pharmaceuticals and polymers).

- Poor Energy Equilibration: The potential energy and temperature time series during the constant-temperature (NVT) phases show high variance, drift, or fail to reach a stable plateau, indicating the system is not equilibrated prior to the cooling ramp.

FAQ 2: How do I systematically diagnose the root cause of a systematic Tg deviation?

Answer: Follow this diagnostic workflow:

Step 1: Benchmarking & Validation

- Action: Compare your simulated Tg against at least two independent experimental datasets obtained via DSC. Use a slow, standard cooling rate (e.g., 1 K/ns) for initial comparison.

- Protocol: Simulate a cooling ramp from 50 K above the experimental Tg to 50 K below it. Use the specific heat (Cv) or density vs. temperature curve to identify the inflection point as Tg.

Step 2: Intermolecular Interaction Analysis

- Action: Calculate radial distribution functions (RDFs) for key atom pairs (e.g., carbonyl O...H-N) and compare them to known structural data or ab-initio molecular dynamics results.

- Protocol: Perform a 10 ns NPT simulation at 298 K. Use

gmx rdf(GROMACS) or equivalent to compute RDFs. Peaks at incorrect distances indicate flawed non-bonded (van der Waals or Coulomb) parameters.

Step 3: Torsional Parameter Interrogation

- Action: Isolate and test the dihedral parameters for key rotatable bonds.

- Protocol: Conduct a series of constrained gas-phase single-molecule simulations, rotating the dihedral angle and plotting the energy profile. Compare this profile to high-level quantum mechanical (QM) scans (e.g., at the MP2/cc-pVTZ level).

Tg Deviation Diagnostic Workflow

FAQ 3: My simulation box shows an unphysical density (<1.0 or >1.5 g/cm³) at room temperature. What should I check first?

Answer: Unphysical densities typically originate from incorrect Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters. Follow this protocol:

- Check LJ Combination Rules: Verify that the simulation engine is applying the correct combination rules (e.g., geometric mean for σ, arithmetic mean for ε) as intended by your force field. Mismatches here are a common error.

- Pressure Equilibration: Ensure the NPT equilibration phase was sufficiently long. Monitor pressure and density time series; they must be stable and fluctuate around the target pressure.

- Validate Atomic Partial Charges: Use a RESP or CHELPG fitting protocol from QM electron density to assign charges. Incorrect net charge or charge distribution can cause catastrophic density errors.

Table 1: Plausible Density Ranges for Common Amorphous Systems

| System Class | Typical Density Range at 298 K (g/cm³) | Red Flag Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Organics (APIs) | 1.15 - 1.35 | <1.05 or >1.45 |

| Polymer Glasses (e.g., PVP, PSA) | 1.05 - 1.30 | <0.95 or >1.40 |

| Amorphous Inorganics (e.g., a-SiO₂) | 2.00 - 2.20 | <1.90 or >2.30 |

FAQ 4: How can I distinguish between poor equilibration and a fundamentally unstable force field?

Answer: Conduct a stepwise stability test.

Protocol: Sequential Stability Analysis

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent/conjugate gradient until Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- NVT Equilibration: Run at target temperature (T) for a minimum of 100 ps. Monitor temperature and potential energy (U). They must stabilize.

- NPT Equilibration: Run at target T and 1 bar for a minimum of 1-5 ns. Monitor density, pressure, and U. These must fluctuate around a stable mean.

- Prolonged NVT Production: Run a 10 ns NVT simulation. Calculate the rolling average of U over 100 ps windows.

Interpretation:

- Poor Equilibration: U/T in steps 2 & 3 shows a directional drift. Fix by extending equilibration time or using better thermostat/barostat coupling (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Unstable Force Field: U in step 4 shows a sudden, catastrophic divergence, or the molecule dissociates. This indicates a critical parameter error (e.g., bonded or 1-4 interaction terms).

Equilibration vs. Instability Check

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Force Field Refinement & Tg Validation

| Item / Solution | Function & Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality DSC Data | Experimental benchmark for Tg. Provides absolute target for validation. | Use multiple cooling rates & extrapolate to 0 K/s. Ensure sample is fully amorphous. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Generates target data for parameterization: torsional scans, dipole moments, electrostatic potential. | Use high-level theory (MP2, CCSD(T)) and large basis sets for final ref parameters. |

| Force Field Parameterization Suite (e.g., MATCH, fftk, GAAMP) | Automates derivation of bonded & non-bonded parameters from QM and exp. data. | Ensure it respects the functional form of your target MD engine (e.g., CHARMM, OPLS, GAFF). |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS) | Performs the cooling simulations to compute Tg. | Critical to use consistent versions and settings for reproducibility. |

| Trajectory Analysis Toolkit (MDTraj, VMD, MDAnalysis) | Calculates RDFs, densities, energy time series, and identifies Tg from simulation data. | Automate analysis pipelines for consistency across multiple simulations. |

| Lennard-Jones Parameter Database (e.g., CGenFF, SwissSidechain) | Provides initial guesses for van der Waals parameters of novel moieties. | Always validate via RDF and density checks; these are often starting points for refinement. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Deviation in Polymer Simulations

Issue: Simulated Tg values are consistently 20-30 K lower than experimental DSC measurements when using a standard forcefield (e.g., GAFF2).

Root Cause Analysis: The discrepancy often stems from inadequately calibrated non-bonded (Lennard-Jones) and torsional parameters. Underestimated dispersion (epsilon) or incorrect torsional barriers around rotatable bonds can lead to excessive chain mobility.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Isolate the Problem: Run a short dynamics of a single, short polymer chain (e.g., 10-mer) in vacuum. Calculate the torsional energy profile for a central dihedral. Compare it to a high-level QM (MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ or DFT-D3) scan for the same dihedral in a model compound.

- Torsional Refit: If barriers differ by >1 kcal/mol, refit the torsional parameters (k_n, phase, periodicity) to match the QM profile. Use a least-squares fitting procedure.

- Bulk Property Calibration: After torsional adjustment, create an amorphous cell with ~20 chains. Perform a cooling protocol (e.g., from 500 K to 200 K at 1 K/ps). Plot specific volume vs. T.

- Adjust Lennard-Jones (LJ): If the simulated Tg remains low, systematically scale the epsilon (ε) parameters for key atom types (e.g., backbone carbons, ether oxygens) by a factor (e.g., 1.05-1.15). Re-run the cooling protocol. Incremental scaling is critical.

- Validation: Validate the final parameters against additional experimental data (density, cohesive energy density).

Guide 2: Handling Unphysical Crystal Formation During Amorphous Cell Generation

Issue: During the equilibration of an amorphous drug-polymer blend, the system rapidly crystallizes, indicating an over-stabilization of crystalline packing.

Root Cause Analysis: The LJ parameters (specifically the ratio of ε and the atomic radius σ) may favor the crystalline lattice geometry too strongly over disordered states.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Check Sigma (σ): Compare the LJ σ values for the problematic moieties (e.g., an aromatic drug molecule) with values from high-quality crystal structures (CSD) or ab initio calculated van der Waals radii. An overly large σ can cause excessive, non-specific packing.

- Systematic Scaling: Reduce the ε parameter for the key aromatic carbon (CA) and polar hydrogen (H) types in the drug molecule by 5-10%. This reduces overly favorable intermolecular interactions.

- Alternative Protocol: Use a much higher starting temperature (e.g., 800 K) for the initial melt and annealing cycle before the production cooling run. This provides more kinetic energy to overcome false minima.

- Apply REST2: If parameter adjustment alone fails, employ Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST2) during the equilibration phase to enhance conformational sampling and prevent trapping in crystalline basins.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which should I calibrate first: torsional profiles or LJ parameters? A: Always start with torsional profiles. Intramolecular barriers dictate chain stiffness and conformational populations, which are primary drivers of Tg. LJ parameter calibration should follow to fine-tune intermolecular packing and cohesion.

Q2: How significant does a QM torsional barrier error need to be to warrant re-parameterization? A: A deviation >1 kcal/mol at any point in the rotational profile is considered significant for Tg prediction. Errors of 2-3 kcal/mol will lead to major shifts in conformational entropy and drastically affect computed material properties.

Q3: Can I scale all LJ epsilon parameters uniformly? A: This is not recommended. Uniform scaling distorts carefully parameterized interactions (e.g., with water). Target scaling should be applied selectively to the atom types most directly involved in the problematic intermolecular interactions (e.g., polymer backbone or specific drug functional groups).

Q4: What is the most reliable experimental reference for Tg calibration in simulations? A: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) at a standard cooling rate (e.g., 10 K/min) is the benchmark. The simulated Tg should be determined from the intersection of linear fits in the specific volume vs. temperature plot, mimicking the DSC analysis protocol.

Q5: How do I know if my simulated density is acceptable after parameter adjustment? A: The simulated density at 298 K should be within 1-2% of the experimental crystalline or amorphous density. Larger deviations indicate underlying issues with the LJ σ parameters or overall force balance.

Table 1: Effect of Parameter Scaling on Simulated Tg of Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)

| Parameter Set | ε Scale Factor (Backbone C/O) | Torsional Barrier Adjustment (kcal/mol) | Simulated Tg (K) | Experimental Tg (K) | Density Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF2 (Unmodified) | 1.00 | 0.0 | 315 ± 5 | 343 | -3.1 |

| Set A (Torsion Only) | 1.00 | +1.2 (C-O-C-C) | 328 ± 4 | 343 | -2.8 |

| Set B (LJ Only) | 1.12 | 0.0 | 332 ± 6 | 343 | -1.5 |

| Set C (Combined) | 1.08 | +1.0 (C-O-C-C) | 341 ± 3 | 343 | -0.7 |

Table 2: Key QM vs. MM Torsional Barrier Comparisons for Acetophenone (Model System)

| Dihedral Angle | QM Barrier (MP2) (kcal/mol) | Initial MM Barrier (GAFF2) (kcal/mol) | Deviation | Refitted MM Barrier (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C(C=O)-Cphenyl-Cphenyl-H | 4.8 | 3.1 | -1.7 | 4.7 |

| C=O-Cphenyl-Cphenyl-C=O | 6.5 | 5.9 | -0.6 | 6.4 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantum Mechanical (QM) Torsional Scan for Parameterization

- Model Compound Selection: Choose a small molecule fragment that accurately represents the rotatable bond of interest in the polymer or drug (e.g., dimethyl ether for a PEO backbone).

- Geometry Optimization: At the HF/6-31G* level, optimize the geometry of the model compound.

- Potential Energy Surface Scan: Constrain the target dihedral angle and perform a single-point energy calculation at 15-degree intervals over a 360-degree rotation. Use a high-level method with dispersion correction (e.g., B3LYP-D3/6-311+G or MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ).

- Energy Fitting: Subtract the minimum energy from the scan. Fit the resulting relative energy profile using a standard periodic function: E = Σ k_n [1 + cos(nφ - δ)].

Protocol 2: Simulated Tg Determination via Cooling Protocol

- System Preparation: Build an amorphous cell containing at least 10-20 polymer chains (or 100+ drug molecules) using PACKMOL or similar tools, targeting experimental density ±10%.

- Equilibration: Minimize energy. Then run NPT dynamics at 500 K (well above expected Tg) for 5-10 ns until density and energy plateau.

- Production Cooling: Using the equilibrated structure, run a stepwise cooling simulation in NPT ensemble. Decrease temperature by 10 K every 1 ns (or 0.5 ns), from 500 K to 200 K. Maintain pressure at 1 atm.

- Data Analysis: For the last 500 ps at each temperature, calculate the average specific volume. Plot specific volume vs. temperature. Fit two linear regression lines to the high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) data points. The intersection point is the simulated Tg.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Tg Parameter Calibration Workflow

Diagram 2: QM-Driven Torsional Parameterization Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Forcefield Calibration Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Ab Initio Software | Performs QM calculations for target molecules to generate reference torsional energy profiles and electron densities. | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Simulates the behavior of the system with the proposed parameters. | GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS, OpenMM. |

| Forcefield Parameterization Tool | Aids in translating QM data into bonded parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals). | Forcefield Toolkit (ffTK) in VMD, Paratool. |

| Amorphous Cell Builder | Generates initial disordered configurations of polymer melts or drug formulations for simulation. | PACKMOL, Molten Salt Generator (MSG), Polymatic. |

| Property Analysis Scripts | Automates calculation of Tg (from V vs. T), density, radial distribution functions, etc. | Custom Python/MATLAB scripts, MDANSE, VMD plugins. |

| Experimental DSC Data | Provides the critical ground-truth glass transition temperature for calibration target. | Must be for the specific material (MW, dispersity) being simulated. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Source for experimental crystallographic data to validate LJ σ parameters and molecular geometry. | Used to check bond lengths, angles, and intermolecular contacts. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My simulated glass transition temperature (Tg) is consistently 20-30% higher than the experimental value. What are the primary protocol-related factors to check?