From Trial-and-Error to AI-Driven Design: A Paradigm Shift in Polymer Science for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional experience-driven methods and modern AI-driven approaches in polymer design, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

From Trial-and-Error to AI-Driven Design: A Paradigm Shift in Polymer Science for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional experience-driven methods and modern AI-driven approaches in polymer design, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It explores the foundational principles of both paradigms, details cutting-edge AI methodologies like machine learning and deep learning for property prediction and synthesis optimization, and analyzes key challenges such as data scarcity and model interpretability. Through validation case studies on biodegradable polymers and drug delivery systems, the article demonstrates the superior efficiency and precision of AI, concluding with future directions for integrating these technologies to accelerate the development of next-generation biomedical polymers.

The Polymer Design Paradigm Shift: From Intuition to Algorithm

For over a century, the development of new polymer materials has relied predominantly on experience-driven methodologies often characterized as "trial-and-error" approaches [1]. This traditional paradigm has been anchored in researcher intuition, iterative laboratory experimentation, and gradual refinement of formulations based on observed outcomes. While this approach has yielded many commercially successful polymers that underpin modern society—from commodity plastics to specialized biomaterials—it operates within significant constraints that limit both efficiency and exploratory potential [1] [2]. The fundamental principle governing traditional polymer design involves making incremental adjustments to known chemical structures and processing conditions based on prior knowledge, then synthesizing and testing these variants through physical experiments. This methodology has been described as inherently low-throughput and resource-intensive, often requiring substantial investments of time, expertise, and laboratory resources [3].

The persistence of traditional approaches stems in part from the complex nature of polymer systems, which exhibit multidimensional characteristics including compositional polydispersity, sequence randomness, hierarchical multi-level structures, and strong coupling between processing conditions and final properties [1]. These complexities create nonlinear structure-property relationships that are often difficult to predict using intuitive approaches alone. Nevertheless, until recent advances in computational power and data science, the polymer community had limited alternatives to these established methodologies, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where conventional approaches became deeply institutionalized within materials research and development [1]. Understanding both the operational principles and inherent limitations of these traditional methods provides essential context for evaluating the transformative potential of emerging data-driven paradigms in polymer science.

Core Principles of Traditional Polymer Design

Experience-Driven Iteration

The traditional polymer design process operates primarily through cumulative expert knowledge transferred across research generations and refined through repeated laboratory practice. Unlike systematic approaches that leverage computational prediction, traditional methodologies depend heavily on chemical intuition and anecdotal successes [1] [2]. Researchers typically begin with known polymer systems that exhibit desirable characteristics, then make incremental modifications to their chemical structures or synthesis parameters based on analogical reasoning and heuristic rules-of-thumb. This approach functions as an informal optimization process where each experimental outcome informs subsequent iterations, creating a slowly evolving knowledge base specific to individual research groups or industrial laboratories [3].

The experiential nature of this paradigm manifests most clearly in its reliance on qualitative structure-property relationships rather than quantitative predictive models. For example, the understanding that aromatic structures enhance thermal stability or that flexible spacers improve toughness has been derived empirically through decades of observation rather than through systematic computational analysis [4]. This knowledge, while valuable, remains fragmented and often proprietary, creating significant barriers to rapid innovation and cross-disciplinary application. Furthermore, the heuristic nature of these design rules limits their transferability across different polymer classes or application domains, requiring re-calibration through additional experimentation when exploring new chemical spaces [1].

Sequential Experimentation Workflow

The traditional research paradigm follows a linear, sequential workflow characterized by discrete, disconnected phases of design, synthesis, and characterization [1] [3]. Unlike integrated approaches where feedback loops rapidly inform subsequent iterations, traditional methodologies typically involve prolonged cycles between hypothesis formulation and experimental validation. The workflow begins with molecular structure design based on literature precedents and researcher intuition, proceeds to small-scale synthesis using standard polymerization techniques, and culminates in comprehensive characterization of the resulting material's properties [3]. Each completed cycle may require weeks or months of laboratory work before yielding actionable insights for the next iteration.

This segmented approach creates fundamental inefficiencies in both time and resource allocation. The extended feedback timeline between conceptual design and experimental validation severely limits the number of design iterations feasible within typical research funding cycles [1]. Additionally, the sequential nature of the process discourages high-risk exploration of unconventional chemical spaces, as failed experiments represent substantial sunk costs with limited compensatory knowledge gains. The workflow's inherent structure thus reinforces conservative design tendencies and prioritizes incremental improvements over transformative innovation [2].

Table 1: Characteristics of Traditional Polymer Design Workflows

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Impact on Research Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Design Process | Based on chemical intuition and literature precedents | Limited exploration of unknown chemical spaces |

| Experiment Scale | Small batches with comprehensive characterization | Low throughput with high cost per data point |

| Optimization Method | One-factor-at-a-time variations | Inefficient navigation of multi-parameter spaces |

| Knowledge Transfer | Experiential and often undocumented | Slow cumulative progress with repeated errors |

| Resource Allocation | Concentrated on few promising candidates | High opportunity cost from unexplored alternatives |

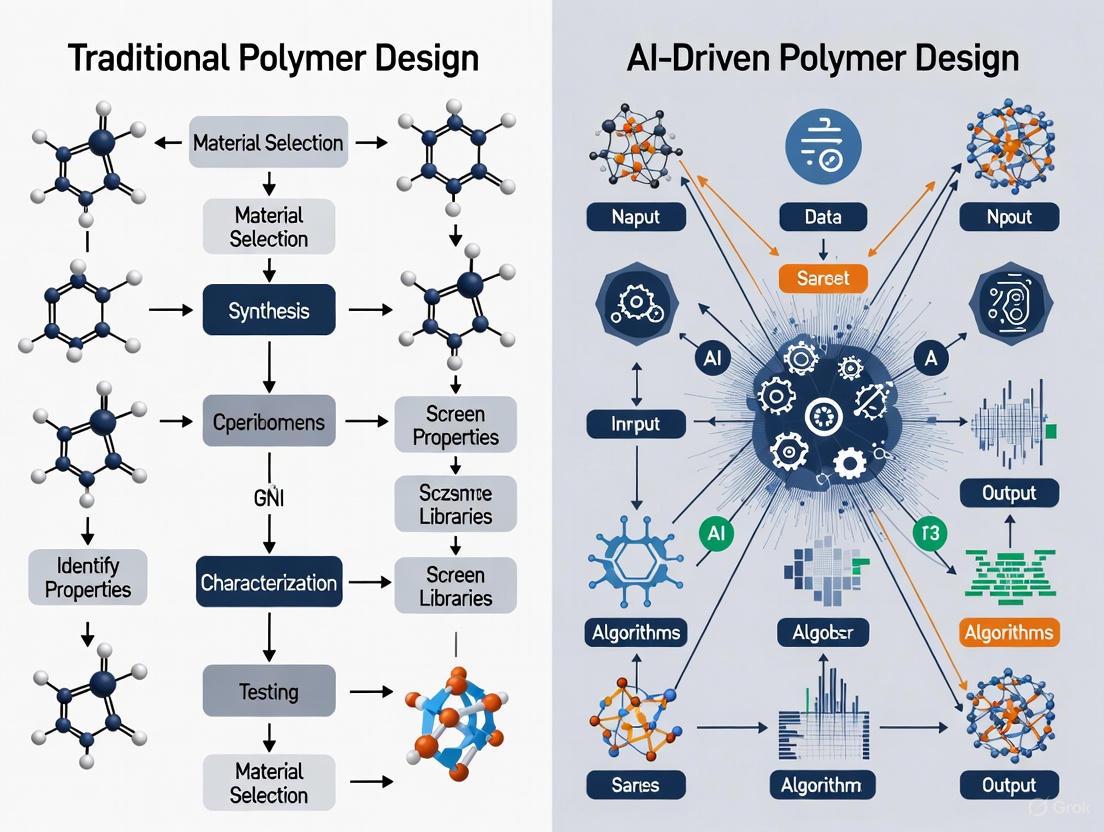

Diagram 1: Traditional polymer design follows a linear, sequential workflow with limited feedback integration.

Limited Exploration of Chemical Space

The trial-and-error paradigm fundamentally constrains the explorable chemical universe due to practical limitations on laboratory throughput. Where computational methods can virtually screen thousands or millions of candidate structures, traditional approaches typically investigate dozens to hundreds of variants over extended timeframes [4] [5]. This restricted exploration capability becomes particularly problematic when designing polymers that require balancing multiple competing properties, such as high modulus and high toughness, or thermal stability and processability [4] [6]. The combinatorial nature of polymer design—with variations possible in monomer selection, sequence, molecular weight, and architecture—creates a search space of astronomical proportions that cannot be adequately navigated through serial experimentation alone [7].

The incomplete mapping of structure-property relationships under traditional methodologies represents a critical limitation with far-reaching consequences. Without systematic exploration of chemical space, researchers inevitably develop biases toward familiar structural motifs and established synthesis pathways, potentially overlooking superior solutions residing in unexplored regions [2]. This constrained exploration manifests clearly in the commercial polymer landscape, where the "diversity in commercial polymers used in medicine is stunningly low" despite the virtually infinite structural possibilities [2]. The failure to discover more optimal materials through traditional approaches underscores the fundamental limitations of human intuition when navigating high-dimensional design spaces without computational guidance.

Key Limitations and Bottlenecks

Temporal and Resource Constraints

The traditional polymer development pipeline typically spans 10-15 years from initial concept to commercial deployment, with the research and discovery phase alone often consuming several years of this timeline [1] [7]. This extended development cycle stems primarily from the low-throughput nature of experimental polymer science, where each design iteration requires substantial investments in synthesis, processing, and characterization. The sequential nature of traditional workflows further exacerbates these temporal inefficiencies, as researchers must complete full characterization cycles before initiating subsequent design iterations [3]. The resulting development timeline creates significant economic barriers to innovation, particularly for applications with rapidly evolving market requirements or emerging sustainability mandates.

The resource intensity of traditional methodologies extends beyond temporal considerations to encompass substantial financial and human capital investments. Establishing and maintaining polymer synthesis capabilities requires specialized equipment, controlled environments, and expert personnel, creating high fixed costs that must be distributed across relatively few experimental iterations [2]. Characterization of polymer properties—particularly mechanical, thermal, and biological performance—demands sophisticated analytical instrumentation and technically skilled operators, further increasing the marginal cost of each data point [8]. These resource requirements inevitably privilege incremental development over exploratory research, as the economic risks of investigating radically novel chemistries become prohibitive without reliable predictive guidance.

Multi-Property Optimization Challenges

Polymer materials for advanced applications must typically satisfy multiple performance requirements simultaneously, creating complex optimization landscapes with inherent trade-offs between competing objectives [4] [6]. Traditional trial-and-error approaches struggle immensely with these multi-property optimization challenges due to the nonlinear relationships between molecular structure, processing conditions, and final material properties. For example, achieving simultaneous improvements in stiffness, strength, and toughness has represented a persistent challenge in polyimide design, as enhancements in one property typically come at the expense of others [4]. Similarly, designing anion exchange membranes that balance high ionic conductivity with dimensional stability and mechanical strength presents fundamental trade-offs that are difficult to navigate through intuition alone [5].

The conflicting property requirements inherent in many polymer applications create optimization problems that exceed human cognitive capabilities, particularly when more than two or three objectives must be considered simultaneously. Traditional approaches typically address these challenges through sequential optimization strategies—first improving one property, then attempting to recover losses in others—but this method often converges to local optima rather than globally superior solutions [6]. The inability to efficiently navigate these complex trade-offs represents a fundamental limitation of traditional design methodologies, particularly for advanced applications in energy, healthcare, and electronics where performance requirements continue to escalate [4] [5].

Table 2: Representative Property Trade-offs in Traditional Polymer Design

| Polymer Class | Conflicting Properties | Traditional Resolution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimides | High modulus vs. high toughness [4] | Sequential adjustment of aromatic content and flexible linkages |

| Anion Exchange Membranes | High ionic conductivity vs. low swelling ratio [5] | Compromise through moderate ion exchange capacity |

| Thermosetting Polymers | Low hygroscopicity vs. high modulus [6] | Empirical balancing of crosslink density and hydrophobicity |

| Biomedical Polymers | Degradation rate vs. mechanical integrity [2] | Copolymerization with unpredictable outcomes |

| Polymer Dielectrics | High permittivity vs. low loss tangent [7] | Trial-and-error modification of polar groups |

Data Scarcity and Knowledge Fragmentation

The traditional polymer research paradigm generates fragmented, non-standardized data that resist systematic aggregation and analysis [2] [8]. Unlike fields such as protein science where centralized databases provide comprehensive structure-property relationships, polymer science has historically lacked equivalent infrastructure for curating and sharing experimental results [2]. This data scarcity stems from multiple factors, including proprietary restrictions, inconsistent characterization protocols, and the absence of standardized polymer representation formats [8]. The resulting information fragmentation severely limits cumulative knowledge building, as insights gained from individual research projects remain isolated within specific laboratories or publications without integration into unified predictive frameworks.

The limited data availability under traditional approaches creates a self-reinforcing cycle where the absence of comprehensive datasets impedes the development of accurate predictive models, which in turn perpetuates reliance on inefficient experimental screening [2]. This problem is particularly acute for properties requiring specialized characterization techniques or extended testing timelines, such as long-term degradation profiles or in vivo biological responses [2]. Even when data generation accelerates through high-throughput experimentation, the value of these investments remains suboptimal without standardized formats for data representation, storage, and retrieval [8]. The transition toward FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles represents a critical prerequisite for overcoming these historical limitations, but implementation remains incomplete across the polymer research community [2].

Case Studies: Traditional Approaches in Practice

Polyimide Film Development

The development of high-performance polyimide films illustrates both the capabilities and limitations of traditional design methodologies. Polyimides represent essential materials for aerospace, electronics, and display technologies due to their exceptional thermal stability and mechanical properties [4]. Traditional approaches to optimizing polyimide films have relied heavily on structural analogy, where researchers modify known high-performing structures through substitution of dianhydride or diamine monomers [4]. This method has successfully produced several commercial polyimides but struggles with the systematic balancing of competing mechanical properties—particularly the optimization of both high modulus and high toughness simultaneously.

The recent integration of machine learning into polyimide development has highlighted the suboptimal outcomes produced through traditional approaches. When researchers applied Gaussian process regression models to screen over 1,700 potential polyimide structures, they identified a previously unexplored formulation (PPI-TB) that demonstrated superior balanced properties compared to traditionally developed benchmarks [4]. This case study demonstrates how traditional methodologies, while capable of producing functional materials, often fail to discover globally optimal solutions due to limited exploration of chemical space and reliance on established structural motifs. The demonstrated superiority of the ML-identified formulation suggests that traditional approaches had prematurely converged on local optima within the vast polyimide design space.

Thermosetting Polymer Design

The discovery of thermosetting polymers with optimal combinations of low hygroscopicity, low thermal expansivity, and high modulus represents another domain where traditional design principles encounter fundamental limitations [6]. The intrinsic conflicts between these properties create a complex optimization landscape that resists intuitive navigation. Traditional approaches have addressed these challenges through copolymerization strategies and empirical adjustment of crosslinking density, but these methods typically achieve compromise rather than optimal solutions [6]. The inability to efficiently balance multiple competing properties has constrained the development of advanced thermosets for microelectronics and other precision applications where dimensional stability under varying environmental conditions is critical.

The limitations of traditional methodologies become particularly evident when considering the resource investments required for comprehensive experimental screening. A systematic investigation of thermosetting polycyanurates would require synthesizing and characterizing hundreds of candidates to adequately explore compositional variations—a prohibitively expensive and time-consuming undertaking under traditional research paradigms [6]. This practical constraint forces researchers to make early decisions about which compositional pathways to pursue, potentially eliminating promising regions of chemical space based on incomplete information. The application of multi-fidelity machine learning to this challenge demonstrates how data-driven approaches can achieve more comprehensive exploration with dramatically reduced experimental effort [6].

Biomedical Polymer Innovation

The development of polymeric biomaterials for drug delivery, tissue engineering, and medical devices highlights the particularly severe limitations of traditional methodologies in complex biological environments [2] [3]. The trial-and-error synthesis approach prevalent in biomedical polymer research faces extraordinary challenges due to the nonlinear relationships between polymer structure and biological responses [2]. Properties such as degradation time, drug release profiles, and biocompatibility depend on multiple interacting factors including molecular weight, composition, architecture, and processing history, creating high-dimensional design spaces that defy intuitive navigation.

The consequences of these methodological limitations are evident in the commercial biomedical polymer landscape, where "the diversity in commercial polymers used in medicine is stunningly low" despite decades of research investment [2]. Traditional approaches have struggled to establish quantitative structure-property relationships for biologically relevant characteristics, as the required datasets would necessitate thousands of controlled experiments with standardized characterization protocols [2]. This data scarcity problem is compounded by the specialized expertise required for polymer synthesis and the limited throughput of biological assays, creating a fundamental bottleneck that has impeded innovation in polymeric biomaterials [3]. The emergence of automated synthesis platforms and high-throughput screening methodologies represents a promising transition toward data-driven design, but the field remains predominantly anchored in traditional paradigms [3].

Experimental Methodologies in Traditional Polymer Research

Synthesis and Characterization Techniques

Traditional polymer design relies on established synthesis methodologies including controlled living radical polymerization (CLRP), ring-opening polymerization (ROP), and various polycondensation techniques [3]. These methods typically require specialized conditions such as inert atmospheres, moisture-free environments, and precise temperature control, creating significant technical barriers to high-throughput experimentation [3]. The characterization arsenal in traditional polymer science encompasses techniques such as size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) for molecular weight distribution, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for structural verification, thermal analysis for transition temperatures, and mechanical testing for performance properties [8]. While these methods provide essential data, their implementation typically involves manual operation, extended analysis times, and limited parallelization capabilities.

The protocol standardization across different research groups presents a persistent challenge in traditional polymer science, as minor variations in synthesis conditions, purification methods, or characterization parameters can significantly influence reported properties [8]. This methodological variability complicates the direct comparison of results across different studies and impedes the aggregation of data for structure-property modeling. Furthermore, many traditional characterization techniques require substantial sample quantities—particularly for mechanical testing—creating an inherent trade-off between comprehensive property evaluation and minimal material usage [2]. These methodological constraints reinforce the low-throughput nature of traditional polymer design and highlight the need for integrated approaches that combine rapid synthesis, automated characterization, and standardized data reporting.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Instruments in Traditional Polymer Design

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerization Techniques | Ring-opening polymerization (ROP), Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [3] | Controlled synthesis of polymers with specific architectures |

| Characterization Instruments | Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [8] | Determination of molecular weight and structural verification |

| Thermal Analysis | Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) | Measurement of transition temperatures and thermal stability |

| Mechanical Testing | Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), Universal testing systems | Evaluation of modulus, strength, and viscoelastic properties |

| Specialized Reagents | Air-sensitive catalysts, Anhydrous solvents [3] | Enabling controlled polymerization in inert environments |

Data Collection and Analysis Practices

Traditional polymer research typically generates fragmented datasets with inconsistent structure-property associations, as data collection focuses predominantly on confirming hypotheses rather than building comprehensive predictive models [8]. Experimental results often remain embedded in laboratory notebooks or isolated publications without standardized formats for polymer representation or property reporting [2]. The absence of universal polymer identifiers analogous to SMILES strings for small molecules further complicates data integration across different research initiatives [8]. These limitations have collectively impeded the development of robust quantitative structure-property relationships that could accelerate the design of future materials.

The analytical methodologies employed in traditional polymer science typically emphasize individual candidate characterization rather than comparative analysis across chemical spaces. Researchers traditionally prioritize comprehensive investigation of promising leads rather than systematic mapping of structure-property landscapes, creating knowledge gaps between well-studied structural motifs and unexplored regions of chemical space [1]. This focus on depth over breadth, while valuable for understanding specific material systems, creates fundamental limitations when attempting to extract general design principles applicable across diverse polymer classes. The transition toward data-driven methodologies addresses these limitations through balanced attention to both comprehensive characterization and systematic exploration of chemical diversity [7].

Diagram 2: Key limitations of traditional polymer design methodologies create fundamental constraints on innovation efficiency.

The traditional trial-and-error approach to polymer design has produced numerous successful materials that underpin modern technologies, but its fundamental limitations in efficiency, optimization capability, and exploratory power have become increasingly evident [1] [2]. The experience-driven nature of traditional methodologies, while valuable for incremental improvements, struggles with the combinatorial complexity of polymer chemical space and the multi-objective optimization challenges inherent in advanced applications [4] [6]. These limitations manifest concretely in extended development timelines, suboptimal material performance, and persistent gaps in structure-property understanding [7].

The emerging paradigm of data-driven polymer design addresses these limitations through integrated workflows that combine computational prediction, automated synthesis, and high-throughput characterization [3] [8]. This approach leverages machine learning algorithms to extract patterns from existing data, generate novel candidate structures, and prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental validation [1] [7]. The demonstrated successes of data-driven methodologies in designing polyimides with balanced mechanical properties, thermosets with optimal property combinations, and anion exchange membranes with conflicting characteristics highlight the transformative potential of this paradigm shift [4] [6] [5]. While traditional approaches will continue to play important roles in polymer science, particularly in validation and application development, their dominance as discovery engines is rapidly giving way to more efficient, comprehensive, and predictive data-driven methodologies.

The field of polymer science is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from intuition-driven, trial-and-error methodologies to a new era of data-driven discovery powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). This paradigm shift, central to the field of Materials Informatics, leverages computational intelligence to navigate the immense combinatorial complexity of polymer systems, thereby accelerating the design of novel materials with tailored properties [9]. Traditional polymer research has long relied on empirical approaches, which are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and limited in their ability to explore vast chemical spaces comprehensively. In contrast, AI-driven approaches utilize algorithms to extract meaningful patterns from data, enabling the prediction of polymer properties, the optimization of synthesis pathways, and the discovery of new materials with unprecedented efficiency [10] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two research paradigms, detailing their core concepts, methodologies, and performance, with a specific focus on applications for researchers and scientists in polymer and drug development.

Core Concepts: Traditional vs. AI-Driven Research

Understanding the fundamental differences between traditional and AI-driven research is crucial for appreciating the scope of this scientific evolution.

The Traditional Polymer Research Paradigm

The traditional approach is largely based on empirical experimentation and established physical principles.

- Methodology: It follows a sequential cycle of hypothesis, experimentation (e.g., polymerization, purification, characterization), and analysis. The design of new polymers often depends on a researcher's expertise and intuition.

- Computational Role: Traditional computational methods, such as Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Density Functional Theory (DFT), are used to simulate polymer behaviors based on explicit physical equations. These methods provide valuable insights but are computationally expensive and often limited to small-scale or simplified systems [9].

- Key Limitation: The process is inherently slow, with low throughput. Exploring a wide range of potential monomers, compositions, and processing conditions is often impractical due to time and cost constraints [11].

The AI-Driven Materials Informatics Paradigm

AI-driven research is a data-centric approach that uses statistical models to learn the complex relationships between a polymer's structure, its processing history, and its final properties.

- Methodology: This paradigm relies on creating ML models trained on existing experimental, computational, or literature data. Once trained, these models can predict the properties of new, unsynthesized polymers or optimize for a desired set of characteristics [10] [12].

- Key Machine Learning Techniques:

- Supervised Learning: Used for predicting continuous properties (e.g., glass transition temperature, tensile strength) through regression or categorical outcomes (e.g., biodegradable vs. non-biodegradable) through classification [9].

- Boosting Methods: Ensemble techniques like Gradient Boosting and XGBoost are particularly effective for tackling high-dimensional and complex problems in polymer science, offering robust predictive capabilities for structure-property relationships [13].

- Deep Learning: Utilizes neural networks for highly complex, non-linear problems, such as predicting polymer phase transitions from complex data sets [9].

- Key Advantage: AI models can screen millions of potential structures in silico in a fraction of the time it would take to synthesize and test them, dramatically accelerating the discovery pipeline [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables summarize quantitative and qualitative comparisons between traditional and AI-driven research methodologies, synthesized from current literature and case studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Research Efficiency

| Performance Metric | Traditional Research | AI-Driven Research | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Time Reduction | Baseline | Up to 5x faster product development [12] | AI-guided platforms reduce iterative cycles by leveraging data modeling [12]. |

| Reduction in Experiments | Baseline | Up to 70% fewer experiments [12] | ML models prioritize high-probability candidates, minimizing lab resource use [12]. |

| Property Prediction Speed | Hours/Days (for MD/DFT simulations) | Seconds/Minutes (for ML inference) | ML predicts properties like glass transition temperature (Tg) almost instantly vs. computationally intensive simulations [9]. |

| Data Integration Time | Manual, slow curation | 60x faster capture of scattered data [12] | Automated data unification from diverse sources (LIMS, ELN) into a central knowledge base [12]. |

Table 2: Qualitative Comparison of Research Capabilities

| Capability Aspect | Traditional Research | AI-Driven Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Researcher intuition & empirical knowledge | Data-driven patterns & predictive algorithms |

| Exploration Capacity | Limited by practical constraints on experimentation | Capable of exploring vast, multi-dimensional design spaces [11] |

| Handling Complexity | Struggles with highly non-linear structure-property relationships | Excels at modeling complex, non-linear relationships [13] |

| Optimization Approach | Sequential, one-factor-at-a-time often used | Multi-objective optimization (e.g., performance, cost, sustainability) is inherent [14] [12] |

| Interpretability | High; based on established physical principles | Can be a "black box"; requires techniques like SHAP analysis for insight [9] [13] |

Experimental Protocols in AI-Driven Polymer Research

The application of AI in polymer science follows a structured, iterative workflow. Below is a detailed protocol for a typical project aiming to predict a target polymer property (e.g., glass transition temperature, Tg) using a supervised learning approach.

Protocol 1: Predictive Modeling for Polymer Properties

Objective: To build a machine learning model that accurately predicts the glass transition temperature (Tg) of a polymer based on its chemical structure and/or monomer composition.

Methodology:

- Data Curation and Feature Engineering

- Data Collection: Assemble a dataset of known polymers and their corresponding Tg values from experimental databases or literature. The dataset must include the polymer's chemical structure (e.g., SMILES notation) [9].

- Data Cleaning: Address missing values, outliers, and ensure consistency in measurement units and conditions.

- Feature Generation: Transform chemical structures into machine-readable numerical descriptors (features). This can include:

- Molecular Descriptors: Molecular weight, fractional polar surface area, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, etc. [15].

- Fingerprints: Binary vectors representing the presence or absence of specific chemical substructures.

- Polymer-Specific Features: Degree of polymerization, tacticity, cross-link density (if available) [9].

- Dataset Splitting: Randomly split the curated dataset into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) for model building and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20-30%) for final evaluation.

Model Selection and Training

- Algorithm Selection: Choose one or more ML algorithms suitable for regression tasks. Common choices include:

- Model Training: The training set (features and target Tg values) is used to fit the selected model(s). The algorithm learns the mathematical relationship between the input features and the target variable.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use techniques like cross-validation on the training set to optimize the model's hyperparameters, maximizing predictive performance.

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Performance Evaluation: Apply the trained model to the hold-out test set (unseen during training) to assess its generalization ability. Key metrics include Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (R²).

- Model Interpretation: Employ interpretability tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to understand which chemical features most strongly influence the model's predictions of Tg, transforming the "black box" into actionable chemical insights [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and iterative feedback loop of this protocol, highlighting the role of AI and human expertise.

Protocol 2: Autonomous Formulation Optimization

Objective: To autonomously discover a polymer formulation that meets multiple target criteria (e.g., high tensile strength, specific degradation rate, low cost) with minimal experimental cycles.

Methodology:

- Define Objective and Constraints: Specify the target properties and their desired ranges or optima. Define constraints such as allowable monomers and cost limits.

- Initial Design of Experiments (DoE): Use an algorithm (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to create a small, diverse set of initial formulations for experimental testing. This provides the first data points for the AI model.

- Active Learning Loop:

- Model Training: Train a multi-output ML model on all accumulated data to predict all target properties from the formulation inputs.

- Candidate Proposal: The AI model proposes the next most informative formulations to test. This is often done using acquisition functions (e.g., in Bayesian Optimization) that balance exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of promising areas.

- Experimental Validation: The proposed formulations are synthesized and characterized, ideally using automated, high-throughput systems [11] [9].

- Data Augmentation: The new experimental results are added to the training dataset.

- Convergence: The cycle repeats until a formulation meets all target criteria or the experimental budget is exhausted, resulting in a drastically reduced number of required experiments [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Solutions for AI-Driven Research

The "reagents" in AI-driven research are computational and data resources. The following table details the essential components of a modern materials informatics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagents" for AI-Driven Polymer Science

| Tool Category / "Reagent" | Function & Explanation | Example Tools / Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Data Management Platform | Serves as a centralized "Knowledge Center" to connect, ingest, and harmonize scattered data from internal and external sources, enabling cross-departmental collaboration. | MaterialsZone [12] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Core engines for building predictive models from data. Boosting methods are particularly noted for their performance in polymer property prediction. | XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM [13] |

| Chemical Descriptors | Translate molecular and polymer structures into a numerical format that ML models can process, acting as the fundamental input features. | Molecular fingerprints, topological indices, polymer-specific descriptors [15] [9] |

| Automated Experimentation | High-throughput robotic systems that physically execute synthesis and characterization tasks, providing the rapid, high-quality data needed to feed and validate AI models. | Self-driving laboratories [11] [9] |

| Cloud-Based AI Services | Provide access to pre-trained models and scalable computing power, lowering the barrier to entry by reducing the need for local, specialized hardware. | Various AI-guided SaaS platforms [12] [11] |

The comparison between traditional and AI-driven polymer research reveals a clear and compelling trend: the integration of AI and machine learning is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental leap forward. While traditional methods retain their value for deep mechanistic understanding and validation, AI-driven Materials Informatics offers unparalleled advantages in speed, efficiency, and the ability to navigate complexity. By enabling the prediction of properties and optimization of formulations with significantly fewer experiments, AI empowers researchers to focus their efforts on creative design and validation. The future of polymer science, particularly in fast-moving fields like drug delivery and sustainable materials, lies in the synergistic combination of domain expertise with data-driven AI tools. This convergence is paving the way for accelerated innovation, from the discovery of new polymer-based therapeutics to the design of advanced sustainable materials.

The field of polymer science is undergoing a foundational shift, moving from long-standing experience-driven methodologies to emerging data-driven predictive modeling approaches [1] [9]. For decades, the development of new polymers relied heavily on researcher intuition, empirical observation, and iterative trial-and-error experiments. While this traditional approach has yielded many successful materials, it is often a time-consuming and resource-intensive process, typically spanning over a decade from initial concept to commercial application [1] [16].

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has established a new paradigm. Predictive modeling uses computational power to identify complex patterns within vast datasets, enabling the prediction of polymer properties and the optimization of formulations and synthesis processes without solely depending on physical experiments [17] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two philosophies, contextualized for researchers and scientists engaged in polymer and material design.

Philosophical and Methodological Comparison

The core difference between these philosophies lies in their starting point and operational mechanism. The traditional approach is fundamentally reactive and knowledge-based, relying on accumulated expert intuition to guide sequential experiments. In contrast, the AI-driven approach is proactive and data-based, using models to predict outcomes and suggest optimal experimental paths.

Table 1: Contrasting Core Philosophies and Workflows

| Feature | Experience-Driven Approach | Predictive Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Intuition, empirical observation, & established chemical principles [9] [19] | Data-driven pattern recognition & statistical learning [1] [17] |

| Primary Workflow | Sequential trial-and-error experimentation [16] | High-throughput in-silico screening & targeted validation [1] [19] |

| Knowledge Foundation | Deep domain expertise & historical data [9] | Large-scale datasets & algorithm training [1] [18] |

| Design Strategy | Incremental modification of known structures [19] | Inverse design from target properties [1] [20] |

| Key Limitation | High cost & time consumption; limited exploration of chemical space [17] [16] | Dependence on data quality/quantity & model interpretability [1] [9] |

Visualizing Research Workflows

The distinct processes of each philosophy are illustrated in the following workflow diagrams.

Diagram 1: The traditional experience-driven research workflow is a sequential, iterative cycle heavily reliant on expert intuition and physical experimentation.

Diagram 2: The AI-driven predictive modeling workflow uses computational screening to prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental validation, creating a continuous learning loop.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Case Study: Designing Novel Polymer Dielectrics

A 2024 study provided a direct comparison by using AI to discover high-temperature dielectric polymers for energy storage. The researchers defined target properties—high glass transition temperature (Tg) and high dielectric strength—and applied a predictive modeling framework [19].

Predictive Modeling Protocol:

- Data Curation: Gathered a large dataset of polymer structures and their associated properties from existing databases and literature.

- Model Training: Trained machine learning models (including graph neural networks) to map chemical structures to the target properties.

- Virtual Screening: The trained models screened a vast virtual library of chemically feasible polymers, including polynorbornene and polyimide families.

- Synthesis & Validation: Top-ranked candidates were synthesized and their properties experimentally characterized [19].

Comparative Outcome: The AI-driven approach discovered a new polymer, PONB-2Me5Cl, which demonstrated an energy density of 8.3 J cc⁻¹ at 200°C. This performance outperformed existing commercial alternatives that were developed through more traditional, incremental methods [19].

Case Study: Predicting Mechanical Properties of Composites

A 2025 study on natural fiber polymer composites compared the accuracy of different modeling approaches for predicting mechanical properties like tensile strength and modulus.

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Generation: 180 experimental samples were prepared using four natural fibers (flax, cotton, sisal, hemp) incorporated at 30 wt.% into three polymer matrices (PLA, PP, epoxy).

- Model Training: Several regression models—Linear, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Deep Neural Networks (DNN)—were trained on the dataset, which was augmented to 1500 samples using bootstrap technique.

- Model Architecture: The best DNN model was optimized with four hidden layers (128-64-32-16 neurons), ReLU activation, and dropout to prevent overfitting.

- Validation: Model predictions were compared against experimentally measured mechanical properties [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Modeling Techniques

| Modeling Technique | Key Advantage | Reported Performance (R²) | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Heuristics | Leverages deep domain knowledge & intuition | Not quantitatively defined; guides initial trials | Success varies significantly with researcher experience [9] |

| Linear Regression | Simple, interpretable, fast computation | Lower accuracy (implied by comparison) | Fails to capture complex nonlinear interactions [21] |

| Random Forest / Gradient Boosting | Good accuracy with structured data, more interpretable than DNNs | High accuracy | Performance plateau on highly complex datasets [21] |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Captures complex nonlinear & synergistic relationships | R² up to 0.89; MAE 9-12% lower than other ML models [21] | "Black-box" nature; requires large data & computational power [1] [21] |

The study concluded that the DNN's superior performance was driven by its ability to capture nonlinear synergies between fiber-matrix interactions, surface treatments, and processing parameters [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The transition to AI-driven methods introduces new tools to the polymer scientist's repertoire, complementing traditional laboratory materials.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for Polymer Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Role | Relevance across Paradigms |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices (PLA, PP, Epoxy) | Base material for composite formation; determines fundamental chemical & thermal stability. | Core to both paradigms. Essential for physical validation in AI-driven approach [21]. |

| Natural/Synthetic Fibers & Fillers | Reinforcement agents to enhance mechanical properties like tensile strength and modulus. | Core to both paradigms. Key variables in composite design [21]. |

| Molecular Descriptors & Fingerprints | Numerical representations of chemical structures (e.g., SMILES strings) enabling machine readability [1]. | Critical for Predictive Modeling. Serves as primary input for ML models [1] [22]. |

| High-Quality Curated Databases (PolyInfo, Materials Project) | Provide the large, structured datasets of polymer structures and properties needed for training ML models [1] [16]. | Critical for Predictive Modeling. Foundation of data-driven discovery [1] [19]. |

| Surface Treatment Agents (Alkaline, Silane) | Modify fiber-matrix interface to improve adhesion and composite mechanical performance [21]. | Core to both paradigms. Experimentally tested; their effect is a key parameter for ML models to learn [21]. |

This comparison demonstrates that experience-driven and predictive modeling approaches are not mutually exclusive but are increasingly complementary. The traditional paradigm offers deep mechanistic understanding and validation, while the AI-driven paradigm provides unprecedented speed and exploration breadth in navigating the complex polymer design space [9] [16].

The most effective future for polymer research lies in a hybrid strategy. In this integrated framework, AI handles high-throughput screening and identifies promising candidates from a vast space, while researchers' expertise guides the experimental design, interprets results in a physicochemical context, and performs final validation [1] [20]. This synergy accelerates the discovery of novel polymers—from dielectrics and electrolytes to biodegradable materials—while ensuring robust and scientifically sound outcomes.

The Growing Imperative for AI in Complex Biomedical Polymer Applications

The development of polymers for biomedical applications—such as drug delivery systems, implants, and tissue engineering scaffolds—represents one of the most challenging frontiers in material science. Traditional polymer design has relied heavily on researcher intuition, empirical observation, and sequential trial-and-error experimentation. This conventional approach, while productive, faces significant limitations in navigating the vast compositional and structural landscape of polymeric materials. The emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) now offers a transformative pathway to accelerate the discovery and optimization of biomedical polymers. This guide objectively compares these two research paradigms, examining their methodological frameworks, performance metrics, and practical applications to highlight the growing imperative for AI-driven approaches in meeting complex biomedical challenges.

Methodological Comparison: Traditional vs. AI-Driven Research

Core Workflows and Fundamental Differences

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between the traditional and AI-driven research workflows in biomedical polymer development.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Traditional vs. AI-Driven Polymer Research Approaches

| Performance Metric | Traditional Approach | AI-Driven Approach | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | Months to years for single material optimization [23] [2] | Days to weeks for screening thousands of candidates [23] [24] | 10-100x acceleration in initial discovery phase [23] |

| Experimental Throughput | Typically 1-20 unique structures per study [2] | High-throughput screening of 11 million+ candidates computationally [5] | >6 orders of magnitude increase in candidate screening capacity [5] |

| Data Utilization | Relies on limited, manually curated datasets | Leverages large, diverse datasets from multiple sources | Enables pattern recognition across broader chemical space [24] |

| Success Rate Prediction | Based on researcher experience and intuition | Quantitative probability scores from ML models | Objectively prioritizes most promising candidates [24] |

| Multi-property Optimization | Sequential optimization of properties, often leading to trade-offs | Simultaneous optimization of conflicting properties (e.g., conductivity vs. swelling) [5] | Balances competing design requirements more effectively |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

AI-Driven Design of Fluorine-Free Polymer Membranes

Experimental Context: The development of anion exchange membranes (AEMs) for fuel cells exemplifies the challenge of balancing conflicting properties: high hydroxide ion conductivity versus limited water uptake and swelling ratio. Traditional approaches have struggled to design fluorine-free polymers that meet all requirements simultaneously [5].

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Researchers compiled experimental data from literature on AEM properties including ion conductivity, water uptake, and swelling ratio [5].

- Model Training: Machine learning models were trained to predict key AEM properties based on chemical structure and theoretical ion exchange capacity [5].

- Virtual Screening: The trained models screened over 11 million hypothetical copolymer candidates [5].

- Validation: Promising candidates identified through computational screening were prioritized for synthesis and experimental validation [5].

Results: The AI-driven approach identified more than 400 fluorine-free copolymer candidates with predicted hydroxide conductivity >100 mS/cm, water uptake below 35 wt%, and swelling ratio below 50% - performance metrics that meet U.S. Department of Energy targets for AEMs [5].

Table 2: Experimental Results from AI-Driven AEM Design Study

| Design Parameter | Traditional Fluorinated AEM (Nafion) | AI-Identified Fluorine-Free Candidates | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxide Conductivity | >100 mS/cm (Proton conductivity) | >100 mS/cm (Predicted) | Comparable performance achieved without fluorine |

| Water Uptake | Variable, often requires optimization | <35 wt% (Predicted) | Superior control of hydration |

| Swelling Ratio | Can exceed 50% at high hydration | <50% (Predicted) | Improved mechanical stability |

| Environmental Impact | Contains persistent fluorinated compounds | Fluorine-free structures | Reduced environmental concerns |

Biodegradable Polymer Discovery

Experimental Context: Developing biodegradable polymers with tailored degradation profiles presents a formidable challenge due to the complex relationship between chemical structure and degradation behavior [19].

Methodology:

- High-Throughput Synthesis: Researchers created a diverse library of 642 polyesters and polycarbonates using automated synthesis techniques [19].

- Rapid Testing: A high-throughput clear-zone assay was employed to rapidly assess biodegradability across the library [19].

- Machine Learning: Predictive models were trained on the resulting data, achieving over 82% accuracy in predicting biodegradability based on chemical features [19].

- Feature Identification: The models identified key structural features influencing biodegradability, such as aliphatic chain length and presence of ether groups [19].

Results: This integrated approach established quantitative structure-property relationships for polymer biodegradability, enabling rational design of environmentally friendly polymers with predictable degradation profiles [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for AI-Driven Polymer Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Research | Traditional vs. AI Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Databases (CRIPT, Polymer Genome) | Provide structured data for ML training; contain polymer structures and properties [2] [19] | In AI workflows, these are essential for model training; less utilized in traditional approaches |

| BigSMILES Strings | Machine-readable representation of polymer structures [2] | Critical for AI: encodes chemical information for computational screening; not used in traditional research |

| Theoretical Ion Exchange Capacity (IEC) | Calculated from polymer structure; predicts ion exchange potential [5] | In AI: enables property prediction before synthesis; in traditional: less accurate empirical measurement |

| High-Throughput Synthesis Platforms | Automated systems for parallel polymer synthesis [3] | AI: generates training data & validates predictions; Traditional: used for limited library synthesis |

| Molecular Descriptors | Quantitative representations of chemical features (e.g., chain length, functional groups) [24] | AI: fundamental model inputs; Traditional: rarely used systematically |

| Active Learning Algorithms | Selects most informative experiments to perform next [24] [3] | AI: optimizes experimental design; Traditional: relies on researcher intuition for next experiments |

Technical Implementation and Protocols

Detailed Experimental Protocol: AI-Driven Polymer Discovery

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive technical workflow for implementing an AI-driven polymer discovery pipeline, from data preparation to experimental validation.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Gather historical data on polymer structures and properties from literature, databases (e.g., CRIPT, Polymer Genome), and experimental records [2] [19].

- Standardize polymer representation using BigSMILES or other machine-readable formats to ensure consistency [2].

- Address data sparsity issues through transfer learning from related properties or simulated data [2].

Feature Engineering and Model Selection:

- Compute molecular descriptors including composition, molecular mass, chain architecture, and functional groups [24].

- Select appropriate ML algorithms based on dataset size and problem type: Random Forests for small datasets, Neural Networks for large, complex datasets [9].

- Divide data into training, validation, and test sets using stratified sampling to ensure representative property distributions.

Virtual Screening and Candidate Selection:

- Apply trained models to screen virtual polymer libraries containing millions of candidates [5].

- Use multi-property optimization algorithms to identify candidates that balance potentially conflicting requirements (e.g., conductivity vs. swelling) [5].

- Apply heuristic filters based on synthetic feasibility, cost, and sustainability considerations.

Experimental Validation and Active Learning:

- Synthesize top-ranked candidates using high-throughput automated platforms [3].

- Characterize key properties using rapid screening assays (e.g., clear-zone tests for biodegradability) [19].

- Feed experimental results back into ML models to refine predictions and guide subsequent design-test cycles [3].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that AI-driven approaches to biomedical polymer design offer substantial advantages over traditional methods in throughput, efficiency, and ability to navigate complex design spaces. The empirical data shows that AI methodologies can screen millions of virtual candidates computationally, identifying promising structures for targeted synthesis and validation. This paradigm reduces development timelines from years to weeks or months while simultaneously balancing multiple, often competing, property requirements.

Nevertheless, the most effective polymer discovery pipelines integrate AI capabilities with traditional polymer expertise and experimental validation. AI serves not to replace researchers, but to augment their intuition with data-driven insights, enabling more informed decision-making throughout the design process. As polymer informatics continues to mature, the scientific community must address remaining challenges including data standardization, model interpretability, and integration of domain knowledge. The growing imperative for AI in complex biomedical polymer applications is clear—these technologies provide the sophisticated tools necessary to meet increasingly demanding biomedical challenges that exceed the capabilities of traditional approaches alone.

AI in Action: Methodologies and Breakthrough Applications in Polymer Science

The field of polymer design is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from reliance on traditional, labor-intensive methods to the adoption of sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) driven approaches. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these paradigms, focusing on the key AI tools—from machine learning to generative models—that are accelerating the discovery and development of novel polymers and composites. We will objectively compare their performance against traditional methods and detail the experimental protocols that validate their efficacy.

The traditional process of developing new polymers and composites has historically been a painstaking endeavor. Traditional polymer design relies heavily on iterative, trial-and-error laboratory experiments, guided by chemist intuition and empirical knowledge. This process involves manually synthesizing and characterizing countless formulations, a method that is often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and limited in its ability to explore the vast chemical space. Techniques like Finite Element Analysis (FEA) provide computational support but can struggle with the full complexity of composite behaviors [18].

In contrast, AI-driven polymer design leverages data-driven methods to predict, optimize, and even invent new materials in silico before they are ever synthesized in a lab. This paradigm utilizes a suite of AI tools:

- Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning: These models analyze historical and experimental data to predict material properties and optimize manufacturing processes [18].

- Generative Models: A subset of AI capable of creating novel molecular structures or composite formulations based on desired target properties, a process known as inverse design [25] [26].

This shift is not merely a change in speed but a fundamental reimagining of the research workflow, enabling the discovery of materials with previously unattainable performance characteristics.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

The following tables summarize quantitative data from recent studies, comparing the outcomes of AI-driven approaches with traditional methods or established baselines in polymer science and drug discovery, a related field that often shares AI methodologies.

Table 1: Performance of AI-Generated Materials in Experimental Validation

| Material Class / Application | AI Model / Approach | Key Experimental Result | Traditional Method Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective Cooling Paint | AI-optimized formulation [23] | Reduced surface temperatures by up to 20°C under direct sunlight [23] | Conventional paints |

| Ring-Opening Polymerization | Regression Transformer (fine-tuned with CMDL) [25] | Successful experimental validation of AI-generated catalysts and polymers [25] | Time-consuming manual catalyst discovery |

| PLK1 Kinase Inhibitors (Drug Discovery) | TransPharmer (Generative Model) [26] | IIP0943 compound showed potency of 5.1 nM and high selectivity [26] | Known PLK1 inhibitor (4.8 nM) |

Table 2: Performance of AI Models in Generative Tasks

| AI Model / Algorithm | Application in Material/Drug Design | Reported Performance / Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Regression Transformer (CMDL) | Generative design of polymers and catalysts [25] | Preserves key functional groups; enables actionable experimental output [25] |

| TransPharmer | Pharmacophore-informed generative model for drug discovery [26] | Excels in scaffold hopping; generates structurally novel, highly active ligands [26] |

| Supervised Learning (SVMs, Neural Networks) | Predicting mechanical properties of composites [18] | Accurately predicts tensile strength, Young's modulus; reduces need for physical testing [18] |

| Materials Informatics | Virtual screening of polymer formulations [23] | Reduces discovery time from months to days [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of AI-driven discoveries, rigorous experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key areas.

AI-Driven Material Discovery and Validation

This protocol outlines the process for using generative models to design new polymers and then experimentally validating their performance, as demonstrated in research on ring-opening polymerization [25].

Data Representation and Model Training:

- Domain-Specific Language (CMDL): Historical experimental data is represented using the Chemical Markdown Language (CMDL). This flexible format captures polymer structures as graphs, where nodes are structural elements (e.g., end groups, repeat units) and edges represent covalent bonds [25].

- Model Fine-Tuning: A Regression Transformer (RT) model, a type of generative AI, is fine-tuned on the dataset encoded in CMDL. This teaches the model the complex relationships between chemical structures and their properties in the context of polymer science [25].

Generative Design:

- Researchers specify desired properties or constraints (e.g., a specific monomer or catalyst family).

- The fine-tuned RT model generates novel, plausible candidate structures (e.g., new catalysts or polymer chains) that are predicted to meet the target criteria [25].

Experimental Validation:

- The AI-generated designs are synthesized and tested in a wet lab.

- Key performance metrics are measured, such as catalytic activity, polymer molecular weight, or thermal properties.

- The experimentally measured properties are compared against the model's predictions to validate the AI's accuracy and refine the model for future cycles [25].

Predictive Modeling for Composite Properties

This methodology is commonly used with supervised machine learning to predict the properties of polymer composites, thus reducing the need for extensive physical testing [18].

Dataset Curation:

- A labeled dataset is assembled from historical experimental records. Input features (

X) include material composition (e.g., fiber volume fraction, filler type, resin properties) and processing parameters. Output labels (Y) are the corresponding measured properties (e.g., tensile strength, Young's modulus, thermal conductivity) [18].

- A labeled dataset is assembled from historical experimental records. Input features (

Model Selection and Training:

- Various supervised learning algorithms are trained on the dataset. Common choices include:

- Support Vector Machines (SVM)

- Random Forests

- Deep Neural Networks [18]

- The dataset is typically split into training, validation, and test sets to ensure the model can generalize to unseen data.

- Various supervised learning algorithms are trained on the dataset. Common choices include:

Prediction and Verification:

- For a new, untested composite formulation, its features are input into the trained model.

- The model outputs a prediction of its properties.

- A subset of these predictions is selected for physical testing to verify the model's accuracy and reliability [18].

Workflow Visualization: Traditional vs. AI-Driven Research

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and fundamental differences between the traditional and AI-driven polymer research workflows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details essential computational and experimental tools that form the backbone of modern, AI-driven polymer and materials research.

Table 3: Essential Tools for AI-Driven Polymer Research

| Tool / Solution Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Markdown Language (CMDL) | Domain-Specific Language | Provides a flexible, extensible syntax for representing polymer structures and experimental data, enabling the use of historical data in AI pipelines [25]. |

| Regression Transformer (RT) | Generative AI Model | A model capable of inverse design, predicting molecular structures based on desired properties, and fine-tuned for specific chemical domains like polymerization [25]. |

| Supervised Learning Algorithms (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) | Machine Learning Model | Trained on labeled datasets to predict key composite properties (tensile strength, thermal conductivity) from composition and processing parameters, reducing physical testing [18]. |

| Pharmacophore Fingerprints | Molecular Representation | An abstract representation of molecular features essential for bioactivity. Used in generative models like TransPharmer to guide the creation of novel, active drug-like molecules [26]. |

| Polymer Graph Representation | Data Model | Deconstructs a polymer into a graph of nodes (end groups, repeat units) and edges (bonds), allowing for the computation of properties and integration with ML [25]. |

The field of polymer science is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving away from intuition-based, trial-and-error methods toward a new era of data-driven, predictive design. For decades, the discovery and development of new polymers relied heavily on experimental iterations, where chemists would synthesize materials, test their properties, and refine formulations through a slow, resource-intensive process that could take years. [23] This traditional approach is now being challenged and supplemented by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies that can accurately forecast mechanical, thermal, and degradation profiles before a single material is synthesized in the lab. [27] This comparison guide examines the capabilities, methodologies, and performance of these competing research paradigms—traditional experimental methods versus AI-driven polymer design—providing researchers and scientists with an objective analysis of their respective strengths, limitations, and practical applications in modern polymer research and drug development.

Traditional Polymer Design: Established Methods and Limitations

Core Methodological Approach

Traditional polymer design follows a linear, experimental path that begins with molecular structure conception based on chemical intuition and known structure-property relationships. The process typically involves synthesizing candidate polymers through established chemical reactions, followed by extensive property characterization and performance testing. This iterative cycle of "design-synthesize-test-analyze" continues until a material meets the target specifications. [23] [28] The approach relies heavily on researcher expertise, published literature, and incremental improvements to existing polymer systems. For example, developing a new paint or polymer formulation has traditionally been a painstaking process where chemists mix compounds, test properties, refine formulations, and repeat this cycle—sometimes for years—before achieving satisfactory results. [23]

Key Experimental Protocols and Techniques

Synthesis and Processing: Traditional methods employ well-established techniques like injection molding for mass-producing polymer parts with intricate geometries, and extrusion for creating pipes, films, and profiles. These processes require precise temperature control to avoid polymer degradation and ensure uniform material properties. [29]

Property Characterization: Standardized testing protocols include Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for thermal properties (glass transition temperature, melting temperature), mechanical testing for tensile strength and elongation at break, and permeability measurements for barrier properties using specialized instrumentation. [30]

Performance Validation: Long-term stability and degradation studies involve subjecting materials to accelerated aging conditions and monitoring property changes over extended periods, often requiring weeks or months to generate reliable data. [5]

Limitations and Challenges

The traditional approach faces significant limitations, including high resource consumption, extended development timelines, and limited exploration of chemical space. With countless possible monomer combinations and processing variables, conventional methods can only practically evaluate a tiny fraction of potential polymers. [23] This constraint often results in incremental innovations rather than breakthrough discoveries. Additionally, the lack of adaptability in traditional polymers—their fixed properties that do not change in response to environmental stimuli—restricts their applications in dynamic fields requiring responsive materials. [28]

AI-Driven Polymer Design: The New Frontier

Fundamental Workflow and Mechanism

AI-driven polymer design represents a radical departure from traditional methods, employing data-driven algorithms to predict material properties and performance virtually. The core of this approach lies in machine learning models trained on existing polymer databases, experimental data, and computational results. [9] [19] These models learn complex relationships between chemical structures, processing parameters, and resulting properties, enabling accurate predictions for novel polymer designs. The workflow typically involves several key stages: data curation and preprocessing, feature engineering (descriptors for composition, process, microstructure), model training and validation, virtual screening of candidate materials, and finally, experimental validation of the most promising candidates. [31] [30]

Key Machine Learning Techniques in Polymer Science

Supervised Learning: Used for classification (e.g., distinguishing between biodegradable and non-biodegradable polymers) and regression tasks (e.g., predicting continuous values like glass transition temperature). Models learn from labeled datasets where each input is associated with a known output. [9]

Deep Learning: Utilizes neural networks with multiple hidden layers to handle highly complex, nonlinear problems in polymer characterization and property prediction. Specific architectures include Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNNs) for structured data and Graph Neural Networks for molecular structures. [9] [27]

Multi-Task Learning: Improves prediction accuracy by jointly learning correlated properties, allowing information fusion from different data sources and enhancing model performance, especially with limited data. [30]

Inverse Design: Flips the traditional discovery process by starting with desired material properties and working backward to propose candidate chemistries using generative models or optimization algorithms. [27]

Experimental Validation of AI Predictions

Despite their computational nature, AI-driven approaches ultimately require experimental validation to confirm predictive accuracy. For example, in a study focused on chemically recyclable polymers for food packaging, researchers used AI screening to identify poly(-dioxanone) (poly-PDO) as a promising candidate. Subsequent experimental validation confirmed that poly-PDO exhibited strong water barrier performance (10^-10.7 cm³STP·cm/(cm²·s·cmHg)), thermal properties consistent with predictions (glass transition temperature of 257 K, melting temperature of 378 K), and excellent chemical recyclability with approximately 95% monomer recovery. [30] This validation process demonstrates the real-world applicability of AI-driven predictions and their potential to accelerate sustainable polymer development.

Direct Comparison: Methodologies and Performance Metrics

Property Prediction Accuracy

Table 1: Comparison of Prediction Capabilities for Key Polymer Properties

| Property Type | Traditional Methods | AI-Driven Approaches | Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Properties | Experimental measurement via DSC; requires synthesis first | Prediction before synthesis; ML models achieve DFT-level accuracy | AI predictions for glass transition temperature within 5 K of experimental values [30] |

| Mechanical Properties | Physical testing of synthesized samples | ML models predict strength, elasticity from structure | Neural networks predict formation energy with MAE ~0.064 eV/atom, outperforming DFT [27] |

| Barrier Properties | Direct permeability measurement | Prediction based on molecular structure and simulations | AI predicted water vapor permeability within 0.2 log units of experimental measurements [30] |

| Degradation Profiles | Long-term stability studies | ML models trained on biodegradation datasets | Predictive models for biodegradability with >82% accuracy [19] |

| Development Timeline | Months to years | Days to weeks | AI can reduce discovery time from years to days [23] |

Experimental Workflows and Resource Requirements

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Research Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Polymer Design | AI-Driven Polymer Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Experiment-based, guided by intuition and experience | Data-driven, guided by predictive algorithms and virtual screening |

| Exploration Capacity | Limited by synthesis and testing capacity | Can screen millions of candidates virtually (e.g., 7.4 million polymers screened [30]) |

| Resource Intensity | High (lab equipment, materials, personnel time) | Lower (computational resources, data curation) |

| Key Techniques | Injection molding, extrusion, DSC, tensile testing, permeability measurement | Machine learning (Random Forests, Neural Networks), molecular dynamics, virtual screening |

| Innovation Potential | Incremental improvements based on existing knowledge | Breakthrough discoveries through identification of non-obvious candidates |

| Adaptability | Fixed properties; limited responsiveness | Enables design of smart polymers that respond to environmental stimuli [28] |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Laboratory Infrastructure for Traditional Methods

Injection Molding Equipment: For mass-producing polymer parts with intricate geometries and tight tolerances, particularly suited for high-performance polymers like PEEK and PPS that require precise temperature control. [29]

Extrusion Systems: Used for producing pipes, films, and profiles from high-performance polymers, requiring advanced die design and process control to maintain uniform material properties. [29]

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Essential for thermal characterization, measuring glass transition temperature, melting temperature, and other thermal properties critical for polymer performance. [30]

Tensile Testing Equipment: For determining mechanical properties including tensile strength, elongation at break, and elastic modulus. [30]

Permeability Measurement Instruments: Specialized equipment for quantifying gas and water vapor transmission rates through polymer films, crucial for packaging applications. [30]

Computational Tools for AI-Driven Research

Polymer Informatics Platforms: Software like PolymRize provides standardized tools for molecular and polymer informatics, enabling virtual forward synthesis and property prediction. [30]

Machine Learning Frameworks: Platforms supporting algorithms like Random Forest, Neural Networks, and Support Vector Machines for property prediction and inverse design. [31]

Simulation Software: Tools such as ANSYS and COMSOL for stress and performance modeling, allowing integration of AI outputs into simulation workflows. [31]

High-Throughput Computing Resources: Infrastructure for running molecular dynamics (MD), Monte Carlo (MC), and density functional theory (DFT) calculations to generate training data for ML models. [30]

Visualization of Research Workflows

Traditional Polymer Development Process

AI-Driven Polymer Design Workflow