Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of glass transition temperature (Tg) and its critical role in pharmaceutical development.

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of glass transition temperature (Tg) and its critical role in pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental principles of Tg in amorphous solid dispersions, details practical methodologies for its measurement, and addresses common challenges in stabilization. It further explores advanced predictive computational models and compares Tg behaviors across various Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and excipients. The synthesis of this information aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance the kinetic stability and solubility of amorphous drug formulations.

Understanding Tg: From Molecular Fundamentals to Pharmaceutical Significance

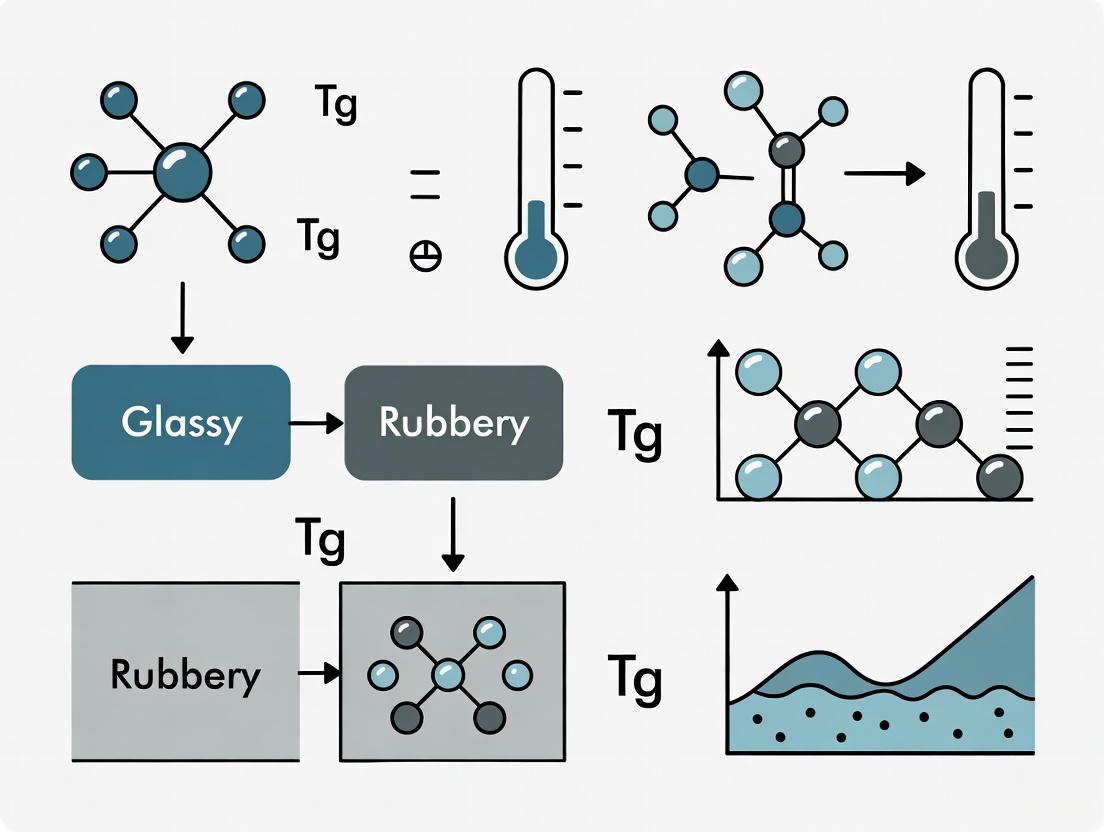

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials (or in amorphous regions within semicrystalline materials) from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rubbery state as the temperature is increased [1]. An amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition is called a glass. The reverse transition, achieved by supercooling a viscous liquid into the glass state, is called vitrification [1].

Unlike first-order phase transitions such as melting or crystallization, the glass transition is not a transition between thermodynamic equilibrium states [1] [2]. It is primarily a dynamic phenomenon where time and temperature are interchangeable quantities to some extent, as expressed in the time–temperature superposition principle [1]. The question of whether some phase transition underlies the glass transition remains a matter of ongoing research [1].

This in-depth technical guide explores the glass transition as a complex phenomenon extending beyond a single temperature point, framing it within current research on glass transition temperature explanation and its critical applications in material science and pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Principles and Characteristics

Molecular Origins of the Glass Transition

At the molecular level, the glass transition temperature corresponds to the temperature at which the largest openings between the vibrating elements in the liquid matrix become smaller than the smallest cross-sections of the elements or parts of them when the temperature is decreasing [1]. As a result of the fluctuating input of thermal energy into the liquid matrix, temporary cavities ("free volume") are created between the elements, the number and size of which depend on the temperature [1].

The glass transition occurs when molecular motions become frozen in on the timescale of observation. For polymers, conformational changes of segments, typically consisting of 10–20 main-chain atoms, become infinitely slow below the glass transition temperature [1]. In a partially crystalline polymer, the glass transition occurs only in the amorphous parts of the material [1].

Key Distinctions from Melting

The glass-transition temperature (Tg) of a material is always lower than the melting temperature (Tm) of the crystalline state of the material, if one exists, because the glass is a higher energy state than the corresponding crystal [1]. The transition comprises a smooth increase in the viscosity of a material by as much as 17 orders of magnitude within a temperature range of 500 K without any pronounced change in material structure [1]. This contrasts sharply with the freezing or crystallization transition, which is a first-order phase transition involving discontinuities in thermodynamic and dynamic properties such as volume, energy, and viscosity [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Glass Transition and Melting Processes

| Characteristic | Glass Transition | Melting Transition |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Classification | Second-order transition features, but not considered true thermodynamic transition | First-order phase transition (Ehrenfest classification) |

| Structural Changes | No long-range order change; gradual change in molecular mobility | Fundamental change from ordered crystalline to disordered liquid state |

| Viscosity Change | Smooth change over ~17 orders of magnitude | Abrupt change at specific temperature |

| Enthalpy/Volume | Continuous change with a step in thermal expansion coefficient and heat capacity | Discontinuous change at transition temperature |

| History Dependence | Strongly dependent on thermal history and cooling/heating rates | Largely independent of thermal history |

Experimental Determination of Tg

Measurement Techniques and Protocols

Multiple experimental techniques exist for measuring the glass transition temperature, each probing different aspects of the transition and often yielding different numeric results. At best, values of Tg for a given substance agree within a few kelvins [1].

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: Measures heat flow differences between sample and reference as a function of temperature, detecting changes in heat capacity at Tg [3].

Standard Protocol:

- Sample preparation: 5-20 mg of material in hermetically sealed pans

- Cooling: Typically at 10 K/min to below Tg

- Heating: At same rate (typically 10 K/min) through transition region

- Tg determination: Midpoint of the step change in heat flow curve [1]

Data Interpretation: The glass transition is identified as a step change in the heat flow curve, with Tg typically taken as the midpoint temperature of this transition [1]. DSC detects the calorimetric Tg associated with changes in enthalpy and heat capacity.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Principle: Applies oscillatory stress to sample and measures mechanical response, detecting changes in viscoelastic properties at Tg [3].

Standard Protocol:

- Sample geometry: Dependent on measurement mode (tension, compression, bending)

- Frequency: Typically 1 Hz (influences measured Tg value)

- Heating rate: 3-5 K/min through transition region

- Tg determination: Peak in tan δ curve or onset of storage modulus drop

Data Interpretation: DMA detects the mechanical Tg associated with changes in molecular mobility affecting mechanical properties. The mechanical Tg often differs from calorimetric Tg due to different underlying phenomena being measured [3].

Dilatometry (Thermal Expansion)

Principle: Measures dimensional changes as a function of temperature, detecting changes in thermal expansion coefficient at Tg.

Standard Protocol:

- Heating rates: 3-5 K/min (5.4–9.0 °F/min) are common [1]

- Tg determination: Temperature at intersection of regression lines for glassy and rubbery states [1]

Discrepancies Between Measurement Techniques

Different operational definitions of Tg yield different numeric results due to the intrinsic nature of the glass transition as a kinetic phenomenon. The mechanical glass transition temperature from DMA often differs from the calorimetric Tg from DSC because they probe different aspects of the transition [3]. For biopolymer systems, the network glass transition temperature derived from mechanical measurements reflects structural relaxation supporting network formation, while calorimetric Tg reflects heat capacity considerations [3].

Factors Influencing Glass Transition Temperature

Molecular and Structural Factors

Multiple molecular factors significantly influence the glass transition temperature of polymeric materials:

Chain Length: Each chain end has associated free volume. Polymers with shorter chains have more chain ends per unit volume, resulting in more free volume and lower Tg [2]. The relationship follows: Tg = [1/Tg,∞ + K/Mw]⁻¹, where Tg,∞ is Tg at infinite molecular weight and Mw is weight average molecular weight [4].

Chain Flexibility: Polymers with flexible backbones have lower Tg due to lower activation energy for conformational changes [2].

Side Groups: Larger side groups hinder bond rotation, increasing Tg. Polar groups (Cl, CN, OH) have the strongest effect [2].

Cross-linking: Cross-linking reduces chain mobility, increasing Tg. It also affects macroscopic viscosity by preventing chains from sliding past each other [2].

Plasticizers: Small molecules (typically esters) increase chain mobility by spacing out chains, reducing Tg [2].

Material-Specific Tg Values

Table 2: Glass Transition Temperatures of Common Polymers and Materials

| Material | Tg (°C) | Tg (°F) | Application State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tire Rubber | -70 | -94 | Used above Tg (rubbery state) [1] |

| Polypropylene (atactic) | -20 | -4 | Semi-crystalline, used above Tg [1] [5] |

| Poly(vinyl acetate) (PVAc) | 30 | 86 | Amorphous polymer [1] |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | 80 | 176 | Amorphous, used below Tg [1] |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 145 | 293 | Amorphous, used below Tg (glassy state) [5] |

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | 210 | 410 | Amorphous, high-performance thermoplastic [5] |

| 49% DMSO (aqueous) | -131 | -204 | Cryopreservation solution [6] |

| 63% Sucrose (aqueous) | -82 | -116 | Food/biopolymer system [6] |

Advanced Theoretical Frameworks

Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Approaches

The formation of glasses can be understood from both kinetic and thermodynamic perspectives:

Kinetic Approach

From a kinetic perspective, glass formation occurs when a liquid is cooled too rapidly for crystals to form. The cooling rate must be fast enough to avoid the crystal region in time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagrams [2]. This approach explains why Tg depends on cooling rate - slower cooling allows more time for structural relaxation, resulting in a higher density glass and lower Tg [1] [2].

Thermodynamic Approach

The thermodynamic approach considers the temperature dependence of thermodynamic properties like enthalpy and entropy. If a supercooled liquid could be followed without crystallizing, its entropy would eventually become less than that of the corresponding crystal at the Kauzmann temperature (TK) [2]. This paradox is avoided because the liquid undergoes the glass transition before reaching TK [2].

Free Volume Theory

The free volume theory posits that molecular transport occurs when voids between molecules exceed a critical size. The glass transition occurs when the free volume decreases to a critical value where molecular rearrangements become impossible on experimental timescales [1] [2].

Tg in Applied Research and Industrial Applications

Cryopreservation and Vitrification

In cryopreservation by vitrification, Tg plays a critical role in preventing thermal stress cracking. Recent research demonstrates that solutions with higher glass transition temperatures experience lower thermal stress and reduced cracking when thermally cycled to and from liquid nitrogen temperatures [6]. This relationship stems from the inverse relationship between Tg and thermal expansion coefficient - higher Tg solutions have lower thermal expansion coefficients, reducing thermally induced stresses [6].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Glass Transition Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Composition | Application/Function | Typical Tg Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO Solution | 49 wt% DMSO in water | Common cryoprotectant for vitrification | -131°C [6] |

| Glycerol Solution | 79 wt% Glycerol in water | Cryoprotectant with intermediate Tg | -102°C [6] |

| Xylitol Solution | 65 wt% Xylitol in water | Sugar alcohol for elevated Tg systems | -87°C [6] |

| Sucrose Solution | 63 wt% Sucrose in water | High Tg cryoprotectant | -82°C [6] |

| κ-Carrageenan/Glucose Syrup | Biopolymer/co-solute matrix | Model for structural relaxation studies | Variable (method-dependent) [3] |

| Gelatin/Polydextrose | Crosslinked protein matrix | Model for network Tg studies | Variable (method-dependent) [3] |

Pharmaceutical and Food Science Applications

In pharmaceutical formulation and food science, Tg determines storage stability, crystallization tendency, and molecular mobility. Below Tg, molecular mobility is severely restricted, potentially preserving unstable compounds [3]. Research has shown that the oxidation rates of omega fatty acids in condensed biopolymer matrices are controlled by their mechanical glass transition temperature, with oxidation kinetics following a sigmoidal model that correlates with structural relaxation processes [3].

The glass transition is a complex phenomenon that extends far beyond a single temperature point. Its definition encompasses kinetic, thermodynamic, and mechanical perspectives, each providing unique insights into material behavior. The dependence of measured Tg on experimental methodology, thermal history, and material composition underscores the need for researchers to carefully consider context when applying glass transition concepts.

Ongoing research continues to reveal new dimensions of the glass transition, particularly in complex biological and pharmaceutical systems where the relationship between molecular mobility, structural relaxation, and stability remains a vibrant area of investigation. The recognition that mechanical and calorimetric glass transitions provide complementary rather than identical information has opened new avenues for controlling material properties in applications ranging from organ cryopreservation to stabilized nutraceutical delivery systems.

As research progresses, the fundamental understanding of the glass transition continues to evolve, driving innovations in material design and processing across diverse scientific and industrial domains.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a fundamental physicochemical parameter that marks the critical temperature at which an amorphous polymer undergoes a transformation from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. This transition is not a phase change but a kinetic phenomenon, characterized by the onset of cooperative segmental motion of polymer chains as thermal energy overcomes the energy barriers for molecular rotation and translation [7] [8]. Below Tg, the chains are frozen in a disordered, solid state, with only limited local vibrations. Above Tg, sufficient energy is available for chains to exhibit large-scale conformational changes, leading to viscoelastic behavior. Understanding and characterizing this "molecular dance" is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals, as it governs key material properties including mechanical modulus, diffusion rates, structural stability, and ultimately, the performance and shelf-life of polymeric materials and their composites [9] [10].

This whitepaper situates itself within the broader context of glass transition research, which seeks to move from phenomenological description to quantitative prediction and control. Recent advances, particularly in machine learning (ML) and high-throughput molecular simulation, are revolutionizing this field. These data-driven approaches are uncovering intricate quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPRs), enabling the rational design of polymers with precisely tailored Tg values for specific applications, from high-temperature composites to controlled-release drug delivery systems [7] [8] [10].

Molecular Mechanisms of Chain Mobility

At the heart of the glass transition lies the concept of chain mobility. The transition from a glass to a rubber is fundamentally a dramatic increase in the freedom of motion of the polymer backbone and side chains.

The Role of Molecular Structure

A polymer's chemical structure directly dictates the energy landscape for chain motion. A key structural descriptor identified through machine learning is the number of rotatable bonds. A higher number of such bonds within the polymer backbone or side chains increases conformational flexibility, leading to a lower Tg, as less thermal energy is required to initiate segmental motion [7]. Conversely, rigid structures, particularly aromatic rings and fused cyclic systems, dramatically reduce chain mobility and elevate Tg. Polyimides (PIs), for instance, owe their high Tg and excellent thermal stability to the presence of rigid, aromatic imide rings and the formation of intramolecular and intermolecular charge-transfer complexes [7] [8].

The influence of side-chain dynamics on bulk properties has been vividly demonstrated in stimuli-responsive polymers. Research on polymethacrylates with pendant triethanolamine borate (TEAB) units reveals that the reversible conversion between a rigid, cage-shaped TEAB and a flexible, open-chain triethanolamine (TEA) can induce a massive Tg shift of up to 166 °C. This work highlights that modulating the conformational flexibility of individual side chains is a potent strategy for controlling macroscopic polymer chain mobility and thermal properties [11].

Aggregation Structure and Dynamics

In complex polymer systems such as semiconducting polymers, the relationship between chain motion and performance is multifaceted. Studies on intrinsically stretchable semiconducting polymers have revealed a distinct decoupling of responsibilities within the aggregation structure: side-chain dynamics predominantly govern the material's stretchability and glass transition behavior, while effectively aggregated backbones are primarily responsible for maintaining efficient charge transport pathways. This insight underscores that the "molecular dance" is not uniform across all parts of a complex polymer architecture [12].

Research Methodologies: From Simulation to Machine Learning

The prediction and measurement of Tg leverage a multi-faceted toolkit, ranging from atomistic simulations that model physical behavior to data-driven models that uncover statistical patterns.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations provide an atomic-level view of polymer behavior across temperatures. The canonical method involves simulating a density-temperature curve during a cooling process; Tg is identified as the point where this curve shows a distinct change in slope [13]. A significant advancement is the ensemble-based MD approach, which runs multiple replicas (an ensemble) of the simulation concurrently at different temperatures, rather than sequentially. This methodology drastically reduces the computational wall-clock time from days to a few hours while maintaining accuracy and providing a robust estimate of uncertainty. Studies recommend ensembles of at least ten replicas to achieve 95% confidence intervals for Tg of less than 20 K [13].

For complex or poorly characterized systems, Machine-Learning Molecular Dynamics (MLMD) has emerged as a powerful tool. In MLMD, a machine-learned potential (MLP) is trained on a high-quality dataset from quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory). This MLP can then be used to run accurate MD simulations at a fraction of the computational cost of direct quantum simulation. This approach has proven highly effective for modeling the structure and glass transition of complex inorganic glasses, such as calcium aluminosilicate systems, where traditional classical MD struggles [14].

Machine Learning (ML) for Tg Prediction

ML-based QSPR modeling bypasses direct simulation by establishing a statistical link between a polymer's chemical structure (represented by molecular descriptors) and its Tg. The standard workflow, as applied to a dataset of over 900 homopolymers [10] and 1261 polyimides [7] [8], involves:

- Data Curation: Assembling a large, high-quality dataset of polymer structures and their experimental Tg values.

- Descriptor Generation: Converting chemical structures into a numerical representation (e.g., using SMILES strings and RDKit) to calculate molecular descriptors that encode topological, electronic, and geometric features.

- Model Training & Validation: Training multiple ML algorithms (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Categorical Boosting, Random Forest) on a subset of the data and rigorously validating their predictive performance on a held-out test set.

The interpretability of these models is enhanced using techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which quantifies the contribution of each molecular descriptor to the predicted Tg, thereby providing insights for molecular design [7] [8].

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors and Their Impact on Glass Transition Temperature

| Descriptor | Description | Impact on Tg | Molecular Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NumRotatableBonds [7] | Number of rotatable bonds in the repeating unit. | Negative | More rotatable bonds increase chain flexibility, lowering the Tg. |

| Electronic Effect Indices [10] | Descriptors encoding the electronic environment of atoms. | Positive | Electron-withdrawing groups can increase intermolecular forces or chain rigidity, raising Tg. |

| Topological Descriptors [10] | Describe the molecular branching and connectivity. | Variable | Complex branching can restrict chain mobility (increasing Tg) or inhibit packing (decreasing Tg). |

| Aromatic Ring Count [8] | Number of aromatic rings in the repeating unit. | Positive | Aromatic rings impart significant rigidity to the polymer backbone, elevating Tg. |

Quantitative Data Synthesis

The performance of modern Tg prediction methodologies can be compared across several studies, revealing a trend where larger, more diverse datasets lead to more robust and accurate models.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Tg Prediction Methodologies from Recent Studies

| Methodology | Polymer System | Dataset Size | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Boosting (ML) | Polyimides (PIs) | 1261 | R² (test) = 0.895, MAE = 18.58 °C, RMSE = 23.06 °C | [7] [8] |

| Support Vector Machine (ML) | Homopolymers | 902 | R² (training) = 0.813, R² (test) = 0.770, RMSE = 0.062 (log units) | [10] |

| Ensemble MD Simulation | Cross-linked Epoxy Resins | 6 (systems) | Agreement with experiment; 95% CI < 20 K with N>=10 replicas | [13] |

| All-Atom MD Validation | Polyimides (PIs) | 8 (structures) | Lowest prediction deviation from ML: ~6.75% | [7] [8] |

| Graph CNN (ML) | Polymers (Various) | 600 | R² = 0.88, MAE = 22.5 K | [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Tg Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a predictive ML model for Tg, as detailed in recent large-scale studies [7] [8] [10].

- Dataset Construction: Collect and curate a dataset of polymer structures and their corresponding experimentally measured Tg values from literature and public databases. Prefer data measured via consistent methods (e.g., Differential Scanning Calorimetry - DSC) to minimize error.

- Structure Standardization and Featurization:

- Represent each polymer's repeating unit using a Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) string.

- Use a cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit) to compute a wide array (e.g., 200+) of molecular descriptors from the SMILES strings. These can include topological, constitutional, and electronic descriptors.

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection methods (e.g., genetic algorithms, correlation analysis) to eliminate redundant or non-informative descriptors and reduce the feature set to a critical subset (e.g., 15-20 descriptors) that maximizes predictive power.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Split the dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and a test set (20-30%).

- Train multiple ML algorithms (e.g., Categorical Boosting, Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, Artificial Neural Networks) on the training set using the selected descriptors as input and Tg as the output.

- Tune the hyperparameters of each algorithm via cross-validation on the training set.

- Evaluate the final performance of each model on the untouched test set using metrics like R², MAE, and RMSE.

- Model Interpretation: Apply model interpretation techniques like SHAP analysis to the best-performing model to identify which molecular descriptors have the greatest influence on Tg and the direction of their effect.

Protocol 2: Ensemble Molecular Dynamics for Tg Determination

This protocol describes the ensemble-based MD approach for calculating Tg with quantified uncertainty [13].

- System Preparation: Build an atomistic model of the cross-linked polymer network or amorphous polymer cell using a tool like PACKMOL. Assign force field parameters (e.g., PCFF, CVFF, GAFF).

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization and equilibration in the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble at a high temperature (e.g., 500 K) well above the expected Tg to ensure a relaxed, melt-like state.

- Ensemble Generation: Generate N independent replicas (N ≥ 10 is recommended) of the fully equilibrated system.

- Concurrent Cooling Simulation:

- For each replica, assign a different target temperature from a range that spans the glassy and rubbery states (e.g., from 500 K to 300 K).

- Run NPT simulations for all replicas concurrently (in parallel) for a defined burn-in period (e.g., 4 ns) followed by a production run (e.g., 2 ns).

- For each replica, record the average density during the production run.

- Data Analysis:

- For each temperature, calculate the average density and standard deviation across the N replicas.

- Plot the average density versus temperature.

- Fit two separate straight lines through the data points in the rubbery (high-temperature) and glassy (low-temperature) regions.

- The glass transition temperature (Tg) is defined as the intersection point of these two linear fits.

- The 95% confidence interval for Tg can be determined based on the standard deviations and the number of replicas.

Visualizing the Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and workflows of the key methodologies discussed.

Machine Learning Prediction Workflow

Ensemble Molecular Dynamics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Glass Transition Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | The primary experimental technique for measuring Tg by detecting changes in heat capacity. | [7] [11] |

| RDKit Software Package | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to compute molecular descriptors from SMILES strings for ML model input. | [7] [8] [10] |

| Triethanolamine Borate (TEAB) Monomers | Functional monomers used to synthesize polymers with chemically switchable side chains, enabling large, reversible modulation of Tg. | [11] |

| Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) Algorithm | A high-performance, open-source ML algorithm particularly effective for building accurate QSPR models with structured data. | [7] [8] |

| LAMMPS (MD Simulator) | A widely used, open-source molecular dynamics simulator capable of performing the ensemble-based simulations for Tg calculation. | [13] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of any ML model, crucial for interpreting which structural features affect Tg. | [7] [8] |

Why Tg is a Cornerstone for Amorphous Pharmaceutical Stability

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a fundamental property that dictates the physical stability, performance, and shelf-life of amorphous pharmaceutical dosage forms. For poorly water-soluble drugs, amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) have emerged as a transformative strategy to enhance bioavailability, with their kinetic stability rooted in the principles of the glassy state. This whitepaper elucidates the pivotal role of Tg through the lens of thermodynamic, kinetic, and environmental factors. We detail advanced experimental protocols for characterizing Tg and its implications, supported by quantitative data and predictive modeling. Framed within ongoing research on glass transition temperature, this guide provides drug development professionals with a foundational understanding and practical toolkit for leveraging Tg to engineer robust, stable amorphous formulations.

The persistent challenge of poor water solubility has driven the pharmaceutical industry to increasingly adopt amorphous formulations. Unlike their crystalline counterparts, amorphous materials lack long-range molecular order, which confers a higher energy state and a significant solubility advantage [15] [16]. This metastable state, however, is inherently susceptible to recrystallization over time or under stress, compromising solubility, dissolution rate, and ultimately, product efficacy and safety [17] [16].

Amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs), where the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is molecularly dispersed within a polymer matrix, have become a cornerstone technology to stabilize the amorphous form. From 2012 to 2023, the U.S. FDA approved 48 ASD-based formulations, signaling a paradigm shift in the pharmaceutical domain [15]. The stability of these systems is not accidental but is engineered through a deep understanding of material science, at the heart of which lies the glass transition temperature (Tg).

The Tg is the critical temperature at which an amorphous material transitions from a brittle, glassy state to a rubbery, supercooled liquid. This transition is accompanied by significant changes in thermodynamic properties such as enthalpy, volume, and entropy, and a dramatic increase in molecular mobility [15] [17]. This whitepaper positions Tg as the cornerstone of amorphous pharmaceutical stability, exploring its theoretical basis, its role in stabilization mechanisms, and the advanced experimental and computational methods used to harness its power in modern drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of Glass Transition Temperature

Defining the Glassy and Rubbery States

Below the Tg, an amorphous material exists in a glassy state. Molecular motions are largely restricted to vibrational and short-range movements, resulting in high viscosity (typically >10^12 Pa·s) and low molecular mobility. In this state, the material is kinetically trapped, and the driving force for crystallization is suppressed, leading to superior physical stability [15] [17].

Upon heating above the Tg, the material transitions to a rubbery state. This is characterized by a rapid increase in molecular mobility, as cooperative motions of entire molecular chains become possible. The system's viscosity drops precipitously, and the configurational entropy increases, making nucleation and crystal growth thermodynamically and kinetically favorable [17]. The relationship between molecular mobility and physical stability is thus intrinsically tied to the Tg, making it a key predictor of shelf life.

The Thermodynamic and Kinetic Basis of Tg

The instability of the amorphous form originates from its higher Gibbs free energy compared to the crystalline state. The difference in free energy provides the thermodynamic driving force for crystallization. The Tg acts as a kinetic barrier to this process; below Tg, the immense viscosity leads to arrested molecular motion, effectively preventing the molecular reorganization required for crystallization over pharmaceutically relevant timescales [16].

The reduced glass transition temperature (Trg = Tg/Tm, where Tm is the melting point in Kelvin) is a useful parameter for determining the glass-forming ability (GFA) of a system. Systems with a higher Trg are generally more stable and less prone to crystallization. Poor glass formers, characterized by low viscosity and high molecular mobility even at room temperature, are prone to crystallization and require higher polymer-to-drug ratios for stabilization, which can limit drug loading [15].

Tg as the Primary Predictor of Physical Stability

Molecular Mobility and Crystallization Tendency

The propensity for an amorphous drug to crystallize is directly linked to its molecular mobility, which is a strong function of the temperature relative to its Tg. A comprehensive study involving 52 drug compounds demonstrated this relationship unequivocally [17].

Table 1: Physical Stability of Amorphous Drugs in Relation to Tg and Glass-Forming Ability (GFA)

| GFA Class | Definition | Stability at T < Tg | Stability at T > Tg | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class II | Crystallizes upon reheating the amorphous material | All compounds remained stable (0/18 crystallized) | Majority crystallized (14/18 crystallized) | High risk of crystallization if stored above Tg |

| Class III | Remains amorphous upon reheating | All compounds remained stable (0/34 crystallized) | Nearly all remained stable (33/34 remained amorphous) | High inherent stability, even above Tg |

This data confirms that storage below Tg is a sufficient condition for the stability of both Class II and Class III compounds. However, storage above Tg is perilous for most Class II compounds, as the increased molecular mobility readily facilitates crystallization. The inherent crystallization tendency, encapsulated by the GFA classification, is therefore a critical determinant of a formulation's stability profile [17].

The Role of Polymers and the Gordon-Taylor Equation

In ASDs, polymers are not inert carriers but active stabilizers. They primarily function by increasing the overall Tg of the dispersion, thereby reducing molecular mobility at storage conditions. A polymer with a high Tg acts as an anti-plasticizer, raising the system's Tg and enhancing its kinetic stability [15].

The Tg of a binary mixture, such as an ASD, can be predicted using the Gordon-Taylor equation, which helps in pre-formulation screening:

Tg,mix = (w1Tg1 + Kw2Tg2) / (w1 + Kw2)

Where w1 and w2 are the weight fractions of components 1 and 2, Tg1 and Tg2 are their respective glass transition temperatures, and K is a fitting constant often related to the strength of molecular interactions [18].

Furthermore, specific drug-polymer interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and ionic interactions, can provide an additional stabilizing effect beyond mere mobility reduction. These interactions improve miscibility and can further inhibit nucleation and crystal growth [15] [18]. The following diagram illustrates the core relationship between Tg, molecular mobility, and stability.

Diagram 1: The relationship between storage temperature, Tg, molecular mobility, and crystallization risk in Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs).

Quantitative Stability Data and Tg

The stability of an ASD is not a simple binary outcome but a complex function of drug loading, storage conditions, and the properties of the polymer. Thermodynamic modeling, such as the Flory-Huggins theory and PC-SAFT, allows for the construction of phase diagrams to identify stable and metastable zones.

For instance, a case study on Ibuprofen (IBU) with various polymers demonstrated how Tg and solubility predictions guide formulation. While all polymers were predicted to be miscible with IBU, phase diagrams revealed that HPMCAS-based ASDs could only maintain stability at very low drug loadings (<5% w/w) at room temperature. In contrast, polymers like KOL17PF and KOLVA64 allowed for higher, pharmaceutically relevant drug loadings (>10% w/w) to reside in a metastable zone, making them superior candidates [18].

Table 2: Impact of Polymer Selection on Ibuprofen ASD Stability (Theoretical Predictions)

| Polymer | Predicted Miscibility | Stable Drug Loading at 25°C | Metastable Drug Loading at 25°C | Suitability for IBU ASD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KOL17PF | Miscible | N/A | >10% w/w | High |

| KOLVA64 | Miscible | N/A | >10% w/w | High |

| Eudragit EPO | Miscible (Borderline) | N/A | >10% w/w | Moderate |

| HPMCAS | Miscible (Borderline) | <5% w/w | 5-10% w/w | Low |

These models highlight that a high Tg polymer alone is insufficient; strong drug-polymer interactions and high miscibility are equally critical to achieving a stable, high-drug-load ASD.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and characterization of stable ASDs rely on a specific toolkit of materials and analytical techniques.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for ASD Research and Development

| Category | Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymers | HPMCAS, PVP-VA64 (KOLVA64), Eudragit EPO, HPMC | Industry-standard carriers that elevate Tg and inhibit crystallization via anti-plasticization and molecular interactions. |

| Characterization Instruments | Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary tool for experimental determination of Tg and melting point depression. |

| Powder X-ray Diffractometer (PXRD) | Confirms the amorphous state of the ASD and monitors for recrystallization during stability studies. | |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR) | Probes drug-polymer interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) that contribute to stability. | |

| Computational Tools | PC-SAFT / Flory-Huggins Models | Thermodynamic models for predicting API-polymer solubility, miscibility, and phase diagrams. |

| Molecular Modeling & Machine Learning | In silico tools for predicting Tg, interaction parameters, and stability, reducing experimental burden. |

Experimental Protocols for Tg Characterization

Determining Tg via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC measures the heat flow into or out of a sample as a function of temperature. The glass transition appears as a step change in the heat capacity (Cp) of the material.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Place 3-5 mg of the finely powdered ASD or pure API into a standard aluminum DSC pan. Crimp the pan hermetically to maintain a dry environment, especially for hygroscopic materials.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using high-purity standards such as indium and zinc.

- Method Setup:

- Equilibration: Hold at 20°C below the expected Tg for 5 min.

- Heating Scan: Heat the sample at a controlled rate (typically 10°C/min) to a temperature well above the expected Tg but below the melting point to avoid thermal degradation.

- Atmosphere: Use a dry nitrogen purge gas (50 mL/min) throughout the experiment.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the resulting thermogram. The Tg is conventionally reported as the midpoint of the step transition in the heat flow curve [15] [18].

Investigating Miscibility via Melting Point Depression (MPD)

Principle: Based on Flory-Huggins theory, the melting point (Tm) of a crystalline API will depress when mixed with a miscible polymer. The extent of depression quantifies the strength of API-polymer interactions and allows for the calculation of the interaction parameter (χ).

Protocol:

- Preparation of Physical Mixtures: Create intimate physical mixtures of the crystalline API with the polymer at varying low drug loadings (e.g., 5%, 10%, 20% w/w).

- DSC Analysis: Run DSC on each physical mixture using the same parameters as for Tg analysis, but ensure the scan range includes the API's melting endotherm.

- Measurement: Record the end-set melting temperature of the API in each mixture. This provides a more consistent value for MPD analysis than the onset or peak temperature [18].

- Modeling:

- Construct a plot of API melting temperature versus polymer volume fraction.

- Fit the data using the Flory-Huggins equation or more advanced models like PC-SAFT to determine the interaction parameter (χ).

- A negative or low positive χ value indicates favorable mixing and miscibility [18].

The workflow for this integrated characterization is summarized below.

Diagram 2: An integrated experimental workflow for characterizing ASD stability using DSC and thermodynamic modeling.

Advanced Formulation Strategies and Future Directions

Leveraging Tg in Formulation Design

Understanding Tg enables sophisticated formulation strategies. For instance, co-milling a drug with excipients like croscarmellose sodium can induce amorphization. Research shows this is particularly effective for good glass formers (Class III) with a high intrinsic Tg, which form more stable amorphous phases under mechanical stress compared to low-Tg drugs [19]. Furthermore, ternary amorphous solid dispersions (TASDs) incorporating a second drug or surfactant can achieve high drug loading and exceptional stability. A TASD of curcumin and resveratrol with Eudragit EPO demonstrated a single, elevated Tg and remained physically stable for 12 months at room temperature, highlighting how multi-component interactions can optimize the glassy matrix [20].

The Future: Predictive Modeling and Digital Design

The field is rapidly moving from empirical testing to a predictive, digital-design approach. Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are being leveraged to predict Tg, drug-polymer miscibility, and physical stability from molecular structures, drastically reducing development timelines [16]. Support vector machine (SVM) algorithms have successfully classified the physical stability of amorphous drugs above Tg based on molecular features, identifying that aromaticity and π-π interactions can reduce inherent stability [17]. The integration of these computational tools with high-throughput experimentation is paving the way for Quality by Digital Design (QbDD), ensuring the development of robust and stable amorphous pharmaceuticals [16] [18].

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is undeniably a cornerstone of amorphous pharmaceutical stability. It serves as a critical indicator of molecular mobility, a predictor of crystallization risk, and a primary target for formulation design. Through the strategic selection of high-Tg polymers and the engineering of specific drug-polymer interactions, formulators can kinetically stabilize the amorphous state, unlocking the bioavailability benefits of poorly soluble drugs. As advanced characterization techniques and predictive computational models continue to evolve, the fundamental understanding of Tg will remain central to the rational design and successful commercialization of amorphous drug products.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a fundamental property of amorphous polymers, marking the temperature at which a material transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. This transition profoundly influences a polymer's mechanical properties, stability, and application potential [21]. In pharmaceutical development, the Tg of polymer excipients and active amorphous solid dispersions is critical for predicting product stability, dissolution behavior, and shelf life. Plasticization, the process of adding a low-molecular-weight substance to a polymer to increase its chain mobility and flexibility, is a primary mechanism for Tg reduction. When the plasticizer is water or ambient moisture, this effect becomes a critical consideration for the handling, performance, and long-term stability of pharmaceutical formulations [21] [22].

The free volume theory provides the dominant explanation for this phenomenon. Above the Tg, polymers possess increased free volume, allowing chain segments to move. Plasticizers, including water, increase this free volume and facilitate polymer chain mobility, thereby lowering the temperature at which the glass-to-rubber transition occurs [23]. This effect is particularly consequential for hydrophilic polymers used in drug delivery systems, as they can absorb significant amounts of moisture from the environment, leading to unpredictable Tg depression and potential failure. This whitepaper explores the mechanisms, quantitative impacts, and experimental analysis of water-induced Tg depression, providing a framework for controlling this effect in pharmaceutical research.

Theoretical Foundations of Plasticization

Mechanisms of Water as a Plasticizer

Water acts as an effective external plasticizer for hydrophilic polymers. Its small molecular size and polar nature allow it to penetrate the polymer matrix and interact with polymer chains through several mechanisms. A key mechanism is the disruption of polymer-polymer hydrogen bonding. Many pharmaceutical polymers, such as polysaccharides and proteins, possess functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH) that form intermolecular hydrogen bonds, creating a rigid network. Water molecules, with their strong hydrogen-bonding capacity, can insert themselves between polymer chains, breaking these polymer-polymer interactions and replacing them with polymer-water hydrogen bonds [22]. This disruption reduces the overall cohesive energy density of the polymer system, allowing chains to move more freely at lower temperatures.

Furthermore, water molecules increase the free volume within the polymer matrix. According to the free volume theory, the small solvent molecules create space between polymer chains, providing room for chain segments to wiggle and slide past one another. This increase in molecular mobility directly translates to a lower Tg [23]. The effectiveness of water as a plasticizer is therefore a function of its compatibility with the polymer (governed by polarity and hydrophilicity) and its concentration within the matrix. The following diagram illustrates the atomistic mechanism of this process.

Internal vs. External Plasticization

It is crucial to distinguish between internal and external plasticization, as their implications for product stability differ significantly. Internal plasticization involves chemically modifying the polymer backbone or side chains to increase flexibility, for example, by copolymerizing a rigid monomer with a flexible comonomer. This method permanently incorporates the flexible units into the polymer structure, making the Tg reduction stable and non-migratory [21].

In contrast, external plasticization relies on the physical addition of a small molecule, such as water, to the polymer matrix. While highly effective, this approach is inherently less stable. The plasticizer can leach out or migrate over time due to changes in environmental conditions, such as temperature and relative humidity. This volatility can lead to an unstable Tg and, consequently, unpredictable material properties during the shelf life of a pharmaceutical product [21]. For water-sensitive formulations, this necessitates rigorous controlled storage and packaging.

Quantitative Analysis of Tg Reduction by Water

Tg Depression by Various Plasticizers

The extent of Tg depression is highly dependent on the specific polymer-plasticizer system. The following table summarizes the effect of different plasticizers, including water and polyols, on the Tg of various polymer matrices, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Tg Depression by Water and Other Plasticizers in Different Polymer Systems

| Polymer System | Plasticizer | Plasticizer Concentration | Resulting Tg (°C) | Tg Depression (ΔTg) | Reference/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose Acetate Succinate (HPMCAS) | Water | Varying Concentration | Measured Reduction | Quantified Agreement | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation [21] |

| β-Cyclodextrin | Water | Varying Concentration | Predicted by Empirical Equations | Quantified Rate | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation [21] |

| Curdlan (CL) Films | Glycerol (GLY) | 10% of dry matter | Not Specified | Significant (Most effective plasticizer) | DSC & Tensile Testing [22] |

| Curdlan (CL) Films | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | 10% of dry matter | Not Specified | Significant (Increased water sensitivity) | DSC & Tensile Testing [22] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) | 30-40 wt% | Drastic Reduction | Baseline for comparison | MD Simulation [23] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Diheptyl Succinate (DHS) | Modeled | Comparable to DEHP | Promising non-toxic alternative | MD Simulation [23] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Dibutyl Sebacate (DBS) | Modeled | Comparable to DEHP | Promising non-toxic alternative | MD Simulation [23] |

The Relationship Between Plasticizer Properties and Effectiveness

The efficiency of a plasticizer is not uniform; it depends on its molecular properties. Key factors include:

- Molecular Weight: Lower molecular weight plasticizers like glycerol (92 g/mol) and ethylene glycol (62 g/mol) are often more effective at reducing Tg on a per-mass basis than higher molecular weight counterparts like sorbitol (182 g/mol) due to their greater mobility and ability to separate polymer chains [22].

- Polarity and Hydrogen Bonding: The number of hydrophilic groups (e.g., -OH) per molecule determines a plasticizer's compatibility with hydrophilic polymers. Glycerol, with three hydroxyl groups, showed superior compatibility and plasticizing effect in curdlan films compared to other polyols [22].

- Molecular Structure: Branching and the balance between polar (cohesive) and non-polar (spacer) groups influence how a plasticizer interacts with the polymer chain. Longer aliphatic chains in molecules like diheptyl succinate (DHS) act as spacers, introducing more free volume and enhancing plasticization [23].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Tg

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Protocol

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is the gold standard for the direct experimental determination of Tg. The following protocol, adapted from standardized methods, ensures accurate and reproducible results [24].

Objective: To determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) of a polymer sample using DSC.

Materials and Equipment:

- DSC instrument (e.g., Mettler Toledo DSC-1)

- Analytical balance (precision to 0.01 mg)

- Aluminum crucibles with lids (e.g., 40 µL volume)

- Sample press

- Nitrogen gas supply (for inert atmosphere)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-dry the polymer sample if necessary to establish a baseline moisture content. Precisely weigh 4-8 mg of the sample using an analytical balance.

- Loading: Place the weighed sample into an aluminum crucible and hermetically seal it using a press. Prepare an identical empty crucible as the reference.

- First Heating Cycle (Heat History Erasure):

- Place the sample and reference crucibles in the DSC furnace.

- Purge the system with nitrogen gas (e.g., 50 mL/min flow rate).

- Quench the sample by rapidly cooling it to -90°C (or a suitable temperature below the expected Tg).

- Hold at -90°C for 5 minutes for thermal equilibration.

- Heat the sample from -90°C to 100°C at a constant rate of 2°C/min.

- This first cycle erases the thermal history of the polymer.

- Second Heating Cycle (Tg Measurement):

- After the first cycle, cool the sample back to -90°C at a controlled rate.

- Reheat the sample from -90°C to 100°C at the same constant rate of 2°C/min. This second heating curve is used for the Tg analysis.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the instrument's software to plot the heat flow (W/g) against temperature.

- Identify the Tg as the midpoint of the step transition in the heat flow curve using the tangent method. The software typically places one tangent on the flat baseline before the transition and another on the flat baseline after the transition, with the Tg taken as the midpoint of the bend between these tangents.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Complementary Thermal Analysis Techniques

While DSC is primary for Tg, other techniques provide complementary information:

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Measures mass change as a function of temperature. It is crucial for determining the volatile content, including water, in a polymer sample. This information is essential for correlating the exact moisture content with the observed Tg [25].

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): Applies a oscillatory stress to the sample and measures the strain response. DMA is highly sensitive to the glass transition, which appears as a sharp drop in the storage modulus (E') and a peak in the loss modulus (E'' or tan δ). It is particularly useful for characterizing thin films [22].

- Thermogravimetry-Mass Spectrometry (TG-MS): Couples TGA with a mass spectrometer to identify and quantify the evolved gases, including water vapor, during thermal decomposition. This is invaluable for understanding decomposition pathways and confirming the loss of moisture at specific temperatures [26].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Acronym | Measurement Principle | Primary Application in Tg Analysis | Quantitative Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry | DSC | Heat flow difference between sample and reference | Direct measurement of Tg and other thermal transitions | Yes (Heat in Joules) |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis | TGA | Mass change of the sample under heating | Determines sample's water/volatile content pre-Tg analysis | Yes (Mass in mg/%) |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis | DMA | Mechanical response (modulus & damping) to oscillatory force | Highly sensitive detection of Tg, especially in films | Yes (Modulus in Pa) |

| Differential Thermal Analysis | DTA | Temperature difference between sample and reference | Identifies thermal events (e.g., Tg) | No (Qualitative) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Plasticization and Tg Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Polyol Plasticizers (Glycerol, Sorbitol, Xylitol, PEG) | Low molecular weight, hydrophilic molecules used to study external plasticization effects. Their multiple hydroxyl groups facilitate hydrogen bonding with polymers. | Systematically comparing plasticizer efficiency in biopolymer films like curdlan [22]. |

| Bio-based Plasticizer Candidates (Diheptyl Succinate - DHS, Dibutyl Sebacate - DBS) | Potential non-toxic alternatives to phthalates. Their structure (ester groups, aliphatic chains) is designed for compatibility and reduced leaching. | In silico (MD simulation) and experimental evaluation of performance in PVC and other polymers [23]. |

| Hydrophilic Polymer Matrices (Curdlan, HPMCAS, β-Cyclodextrin) | Model polymers that are susceptible to water plasticization. Used as the base material for studying moisture-polymer interactions. | Investigating water uptake, Tg depression, and changes in mechanical properties [21] [22]. |

| Aluminum Crucibles | Standard containers for holding solid samples in DSC and TGA. Their high thermal conductivity ensures rapid heat transfer. | Encapsulating polymer samples for Tg measurement via DSC [24]. |

| Inert Carrier Gas (Nitrogen, Helium) | Creates an inert atmosphere during thermal analysis to prevent oxidative degradation of the sample. | Purging the DSC/TGA furnace during Tg and decomposition analysis [26] [24]. |

Implications and Strategic Control in Pharmaceutical Development

The plasticizing effect of water has profound implications for pharmaceutical development. For amorphous solid dispersions, which are often used to enhance the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs, a depression of Tg below the storage temperature can lead to devitrification (crystallization of the drug). This crystallization can drastically reduce dissolution rate and bioavailability. Similarly, the physical stability of lyophilized (freeze-dried) products, which rely on a high Tg to remain stable in the glassy state, can be compromised by moisture uptake during storage.

To mitigate these risks, strategic approaches are essential:

- Formulation Optimization: Selecting polymer excipients with inherently high Tg or low hygroscopicity.

- Robust Packaging: Using moisture-barrier primary packaging (e.g, cold-form blister packs, glass vials with appropriate closures) to control the storage microenvironment.

- Process Control: Implementing rigorous drying steps and controlling humidity during manufacturing.

- Predictive Modeling: Utilizing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to predict the Tg of polymer-water systems before extensive experimental work, accelerating the development cycle [21] [23].

Water is a potent and ubiquitous plasticizer that can dramatically lower the glass transition temperature of hydrophilic polymers. This effect, driven by the disruption of polymer-polymer interactions and an increase in free volume, poses a significant challenge to the stability of pharmaceutical formulations. A comprehensive understanding of the quantitative relationships, coupled with robust experimental characterization using DSC, TGA, and other thermal techniques, is paramount. By integrating this knowledge with strategic formulation and packaging design, scientists can effectively control the plasticizing effect of moisture, ensuring the development of stable and efficacious drug products.

In the field of lyophilization, also known as freeze-drying, the glass transition temperature of the maximally freeze-concentrated solution (Tg') stands as a fundamental physicochemical parameter that dictates process design and product stability. Lyophilization is an essential manufacturing process for improving the long-term stability of labile drugs, particularly therapeutic proteins, with approximately 50% of marketed biopharmaceuticals utilizing this approach [27]. The process consists of three critical steps: freezing, primary drying, and secondary drying [27] [28]. Within this framework, Tg' represents the temperature at which the amorphous concentrated solute phase, formed during ice crystallization, undergoes a transition from a rigid glass to a viscous rubbery state [29]. This transition profoundly influences the lyophilization cycle design and ultimately determines the stability, efficacy, and quality of the final lyophilized product.

Understanding Tg' is particularly crucial for pharmaceutical scientists developing lyophilized biopharmaceuticals because it establishes the critical temperature limit during primary drying. Exceeding this temperature risks structural collapse of the product, potentially compromising key quality attributes including stability, reconstitution time, and residual moisture content [29]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations of Tg', details experimental methodologies for its determination, provides quantitative data for common pharmaceutical excipients, and establishes its practical significance within the broader context of glass transition temperature research for lyophilized product development.

Theoretical Foundations of Tg'

The Freezing Process and Cryoconcentration

The lyophilization process begins with the freezing step, during which a liquid formulation is cooled until ice nucleation occurs, followed by ice crystal growth. This process results in the physical separation of pure ice crystals from a matrix of concentrated solutes [27]. As freezing progresses, the solution becomes increasingly concentrated in a process known as cryoconcentration until it reaches a state referred to as the "maximally freeze-concentrated solution." In this state, the concentrated solute phase no longer allows further ice formation due to its extremely high viscosity [27] [29]. The temperature at which this maximally freeze-concentrated solute phase undergoes a glass transition is defined as Tg', while the corresponding solute concentration is designated as Cg' [29].

The Significance of the Glassy State

Below Tg', the maximally freeze-concentrated solute exists in an amorphous glassy state characterized by extremely high viscosity (approximately 10^13 poise), which effectively immobilizes molecules within a rigid matrix [30]. This molecular immobilization drastically reduces diffusion-limited degradation pathways, thereby preserving the stability of biopharmaceuticals during storage. The glassy state inhibits chemical degradation reactions and physical changes, making it essential for maintaining the stability of labile therapeutic proteins during storage [27]. The transition from this glassy state to a rubbery state above Tg' represents a critical boundary for process design, as the increased molecular mobility in the rubbery state can lead to collapse during drying and increased degradation rates during storage [29].

Distinction Between Tg' and Collapse Temperature (Tc)

It is crucial to distinguish Tg' from the collapse temperature (Tc), though these parameters are closely related. Tg' is a well-defined thermodynamic transition point of the maximally freeze-concentrated solute phase, while Tc represents the practical temperature at which macroscopic structural collapse occurs in the product during primary drying [29]. For most amorphous formulations with low solute concentrations (<50 mg/mL), Tc typically lies within 1-2°C of Tg'. However, for high-concentration protein formulations (≥50 mg/mL), a significant difference of 5°C or more between Tc and Tg' is often observed [29]. This distinction becomes critically important for process optimization, as primary drying can sometimes be conducted above Tg' but below Tc without adversely affecting product quality, potentially reducing primary drying time by approximately 13% per 1°C increase in product temperature [29].

Experimental Determination of Tg'

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry serves as the primary technique for experimental determination of Tg'. The methodology involves several carefully controlled steps to ensure accurate and reproducible results [31].

Sample Preparation

- Prepare the candidate formulation solution in the desired buffer system.

- Dialyze protein solutions if necessary to remove low molecular weight contaminants using membranes with appropriate molecular weight cut-offs (typically 12-14 kDa) [31].

- Load 3-5 mg of the solution into a hermetically sealed DSC pan, using an empty pan as reference.

Thermal Cycling Protocol

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the sample at 20°C for 2 minutes [31].

- Freezing Phase: Cool the sample to -50°C at a controlled rate of 1°C/min to simulate freezing conditions in lyophilization [31].

- Isothermal Hold: Maintain the sample at -50°C for 30 seconds to ensure complete thermal equilibrium [31].

- Heating Phase: Heat the sample to 30°C at a rate of 10°C/min while monitoring heat flow [31].

Data Analysis

- Analyze the resulting thermogram using appropriate software (e.g., Universal Analysis software for TA Instruments) [31].

- Identify Tg' as the onset temperature of the change in heat capacity during the heating phase, which appears as a step change in the baseline signal [29].

- For complex systems exhibiting multiple thermal events, the lower transition typically corresponds to Tg" (attributed to glass transition in a less concentrated frozen solution), while the higher transition represents Tg' [32].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for Tg' determination using DSC:

Freeze-Dry Microscopy (FDM)

Freeze-Dry Microscopy complements DSC by providing direct visualization of structural collapse and determining the collapse temperature (Tc), which is closely related to Tg' [29].

Methodology

- Place a small sample volume (typically a few microliters) on a temperature-controlled stage.

- Freeze the sample and apply vacuum to simulate primary drying conditions.

- Gradually increase temperature while monitoring the sample structure via microscopy.

- Record the temperature at which the frozen matrix loses its microscopic structure and collapses as Tc.

Recent advancements including optical coherence tomography freeze-dry microscopy enable Tc determination directly in vials, which may provide more relevant data than traditional FDM for cycle development [29].

Quantitative Tg' Data for Pharmaceutical Systems

The Tg' value varies significantly depending on the composition of the formulation. Disaccharides generally exhibit higher Tg' values compared to monomeric sugars, and the presence of crystalline components or proteins further influences this critical parameter.

Tg' Values of Common Lyophilization Excipients

Table 1: Glass Transition Temperatures (Tg') of Common Pharmaceutical Excipients in Maximally Freeze-Concentrated Solutions

| Excipient | Tg' (°C) | Concentration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | -82 [6] | 63 wt% | Common lyoprotectant |

| Sucrose | -32 [32] | Not specified | Varies with measurement method |

| DMSO | -131 [6] | 49 wt% | Common cryoprotectant |

| Glycerol | -102 [6] | 79 wt% | Plasticizer, lowers Tg' |

| Xylitol | -87 [6] | 65 wt% | Sugar alcohol |

| Mannitol | Crystalline | N/A | Forms crystalline phase, no Tg' |

Tg' in Protein Formulations

Table 2: Tg' and Tc Values in Model Protein Formulations [29]

| Protein | Formulation Type | Protein Concentration (mg/mL) | Tg' (°C) | Tc (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAb A | Amorphous-only | 25 | -27.5 | -25.5 |

| mAb A | Amorphous-only | 50 | -23.5 | -18.5 |

| Pro B | Amorphous-crystalline | 2.5 | -33.5 | -31.5 |

| Pro B | Amorphous-crystalline | 25 | -31.5 | -26.5 |

The data demonstrates that Tg' increases with protein concentration in amorphous systems and that partially crystalline systems (containing components like mannitol or glycine) exhibit different Tg' profiles compared to purely amorphous systems [29].

Practical Applications in Lyophilization Cycle Development

Role in Primary Drying Design

The Tg' parameter directly informs the development of the primary drying phase, which is typically the longest segment of the lyophilization cycle [28] [29]. During primary drying, the product temperature must be maintained below Tg' (or Tc for high-concentration formulations) to prevent structural collapse of the product cake [29]. Modern approaches to cycle optimization focus on operating as close as possible to this temperature limit without exceeding it, thereby maximizing sublimation rates while maintaining product quality.

Controlled Ice Nucleation

The random nature of ice nucleation presents a significant challenge to process consistency, as it creates variability in ice crystal size and morphology, subsequently affecting drying rates and product homogeneity [27] [28]. Controlled ice nucleation techniques address this challenge by actively initiating ice formation at a defined temperature, promoting the formation of larger ice crystals and resulting in a more consistent pore structure with lower resistance to vapor flow during primary drying [28]. This approach enhances inter-vial consistency and can reduce primary drying times, demonstrating the interconnection between freezing behavior and the Tg'-defined design space.

Single-Step Drying and Tg'

Recent advancements in lyophilization technology have explored single-step drying approaches, where primary and secondary drying are combined into one continuous step [29]. This methodology can potentially reduce overall cycle times from several days to a single day, offering significant manufacturing efficiencies. The successful implementation of single-step drying relies on precise control of product temperature relative to Tg' and Tc, particularly for high-concentration protein formulations where the difference between these parameters is more pronounced [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Tg' Research and Lyophilization Development

| Item | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DSC Instrument | Thermal analysis to determine Tg' | TA Instruments Q2000 [31] |

| Freeze-Dry Microscope | Direct visualization of collapse events | Optical coherence tomography systems [29] |

| Lyoprotectants | Stabilize proteins during drying and storage | Sucrose, Trehalose [31] |

| Cryoprotectants | Protect against freezing-induced stresses | DMSO, Glycerol [6] |

| Crystalline Bulking Agents | Provide structural support and eutectic crystallization | Mannitol, Glycine [29] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain pH during freezing and drying | Potassium Phosphate, Histidine [31] |

| Bench-top Lyophilizer | Small-scale process development | Virtis Bench Top Lyophilizer [31] |

Thermal Transitions in Frozen Systems

The thermal behavior of frozen aqueous systems is complex, often involving multiple transitions that researchers must carefully interpret. As shown in the diagram below, frozen systems can exhibit two distinct thermal events: Tg" (the glass transition of a less concentrated freeze-concentrated solution) and Tg' (the glass transition of the maximally freeze-concentrated solution) [32]. Some interpretations also include the ice melting/dissolution onset in this complex thermal profile.

Tg' remains an indispensable parameter in the development and optimization of lyophilization cycles for biopharmaceutical products. Its critical role in defining the maximum allowable product temperature during primary drying establishes the fundamental boundary conditions for process design. As the biopharmaceutical landscape continues to evolve with increasingly complex therapeutic modalities, the precise determination and application of Tg' will maintain its vital importance in ensuring the production of stable, efficacious, and high-quality lyophilized products. Furthermore, ongoing research into the relationships between Tg', Tc, and collapse phenomena continues to enable more efficient lyophilization processes, such as single-step drying and aggressive primary drying approaches, that reduce manufacturing costs while maintaining product quality.

Measuring Tg in Practice: Techniques and Formulation Strategies

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) stands as the predominant thermoanalytical technique for detecting and characterizing the glass transition temperature (Tg) in polymeric, pharmaceutical, and advanced material systems. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of DSC methodologies for Tg detection, detailing underlying principles, standardized experimental protocols, and critical interpretation guidelines. Within the broader context of glass transition research, DSC offers unparalleled capability for quantifying the reversible heat capacity change that demarcates the glassy-to-rubbery transition, providing essential data for material selection, formulation stability, and performance prediction in drug development and material science applications.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is a thermoanalytical technique that measures the difference in heat flow between a sample and an inert reference as they undergo a controlled temperature program [33]. The fundamental principle underpinning DSC is the monitoring of heat flow required to maintain the sample and reference at identical temperatures throughout the heating or cooling process [34]. When a thermal event occurs in the sample—such as the glass transition—the instrument quantifies the differential energy input needed to maintain thermal equilibrium, providing direct calorimetric measurement of transition energies [35].

The glass transition temperature (Tg) represents a critical physicochemical parameter where amorphous materials transition from a rigid glassy state to a more flexible, rubbery state [36]. This second-order transition manifests in DSC as a characteristic step change in the baseline heat flow due to an alteration in the sample's heat capacity (Cp) [34] [36]. Unlike first-order transitions such as melting or crystallization that produce distinct peaks, the glass transition represents a change in the material's molecular mobility without a formal phase change [34]. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurate Tg determination provides crucial insights into material stability, processing conditions, and end-use performance, particularly for polymeric excipients, protein formulations, and solid dispersions [37] [38].

DSC Technology and Measurement Principles

Fundamental DSC Operating Principles

DSC instruments operate primarily under two distinct measurement principles, both capable of Tg detection but employing different technical approaches:

Heat-Flux DSC: This system employs a single furnace that simultaneously heats both the sample and reference crucibles, which are positioned on a thermoelectric disk [33] [39]. The temperature difference (ΔT) between the sample and reference is measured and converted to heat flow using the thermal equivalent of Ohm's law (q = ΔT/R), where R represents the thermal resistance of the measuring system [37] [39]. Heat-flux DSC designs offer benefits including simple design, good baseline stability, and robustness across various atmospheric conditions [39].

Power-Compensated DSC: This configuration utilizes separate, individually controlled furnaces for the sample and reference [33] [34]. The system actively maintains both furnaces at identical temperatures by supplying differential power to the two heaters, and directly measures this power difference as the heat flow signal [34] [37]. This design allows for rapid heating and cooling rates and can provide enhanced sensitivity for certain applications.

Table 1: Comparison of DSC Measurement Principles

| Feature | Heat-Flux DSC | Power-Compensated DSC |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Measures temperature difference between sample and reference | Measures power difference to maintain equal temperatures |

| Furnace Configuration | Single shared furnace | Separate furnaces for sample and reference |

| Key Advantage | Simpler design, good baseline stability | Faster response time, high sensitivity |

| Typical Applications | Routine quality control, polymer analysis | High-resolution studies, pharmaceutical applications |

Advanced DSC Techniques

Several specialized DSC methodologies have been developed to enhance Tg detection and interpretation:

Temperature-Modulated DSC (TMDSC): This technique superimposes a sinusoidal temperature oscillation onto the conventional linear heating ramp, enabling the separation of reversible and non-reversing thermal events [34]. For glass transition analysis, this allows distinguishing the reversible heat capacity change (associated with Tg) from overlapping non-reversing events such as relaxation endotherms or evaporation effects [34].

High-Pressure DSC: Systems capable of operating under elevated pressures (up to 150 bar) facilitate the study of pressure-dependent Tg behavior, particularly relevant for polymers and materials processing under non-ambient conditions [39].

Fast-Scan DSC: Employing micromachined sensors, this technique achieves ultrahigh scanning rates (up to 10⁶ K/s) with exceptional heat capacity resolution (<1 nJ/K), enabling the study of rapid phase transitions and thermally labile compounds [34].

Tg Detection by DSC: Mechanisms and Signature

The Molecular Basis of Glass Transition

The glass transition represents a kinetic phenomenon where polymer chains or molecular segments gain sufficient mobility to undergo coordinated molecular motion as temperature increases [40]. Below Tg, molecular motions are restricted to vibrations and short-range rotations, with backbone segments frozen in place. As temperature approaches Tg, the free volume increases sufficiently to permit segmental rearrangement, leading to the characteristic softening observed as the material transitions from a glassy to rubbery state [40]. This increased molecular mobility requires additional energy input, manifesting as an increase in the heat capacity (Cp) of the material [34] [36].

Characteristic DSC Signature of Tg

In a DSC thermogram, the glass transition appears as a step change in the baseline heat flow direction rather than a distinct peak [36]. The transition is characterized by three key temperature points:

- Onset Temperature (Tg-onset): The initial deviation from the baseline, indicating the beginning of the glass transition process.

- Midpoint Temperature (Tg-mid): The temperature at which half of the heat capacity change has occurred, typically reported as the standard Tg value.

- Endpoint Temperature (Tg-end): The point where the baseline stabilizes again, completing the transition.

For conjugated polymers and semicrystalline materials, the Tg signature in conventional DSC can be suppressed due to rigid backbones and limited amorphous regions, sometimes necessitating complementary techniques like dynamic mechanical analysis for unambiguous identification [40].

The following diagram illustrates the characteristic DSC curve for Tg detection and its interpretation:

Experimental Protocols for Tg Detection

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining accurate and reproducible Tg measurements:

Sample Mass and Pan Selection: Optimal sample masses typically range from 5-20 mg, depending on the expected transition strength [34]. Hermetically sealed aluminum crucibles are standard for most applications, providing good thermal contact while preventing solvent loss. For high-pressure measurements or volatile samples, high-pressure stainless steel crucibles are recommended [34] [39].

Sample Form Considerations:

- Powders: Finely ground powders ensure uniform heat transfer and representative sampling. Particle size should be consistent across comparative studies.

- Solid Films: Uniform thickness films provide excellent thermal contact with the crucible base.

- Liquids/Solutions: Hermetic sealing is essential to prevent evaporation artifacts during heating [34].