Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) as a Key Design Parameter: Mastering Morphological Stability in Organic Semiconductors

This article provides a comprehensive review of the critical role glass transition temperature (Tg) plays in determining the morphological and operational stability of organic semiconductors.

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) as a Key Design Parameter: Mastering Morphological Stability in Organic Semiconductors

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the critical role glass transition temperature (Tg) plays in determining the morphological and operational stability of organic semiconductors. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and development professionals, we first establish the foundational link between Tg, molecular dynamics, and thin-film microstructure. We then explore practical methodologies for Tg measurement and control through molecular engineering, polymer design, and blending strategies. The article addresses common stability failures and offers troubleshooting frameworks for optimizing device longevity. Finally, we compare and validate different stability assessment techniques, correlating accelerated aging tests with real-world performance. This synthesis provides a clear roadmap for designing next-generation, stable organic electronic materials for biomedical sensors, implantable devices, and clinical diagnostics.

The Physics of Stability: Understanding Tg, Molecular Mobility, and Morphological Degradation

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Section

Q1: Why does my organic semiconductor (OSC) film performance degrade over time, even in inert atmospheres? A: This is a classic symptom of thermodynamic morphological instability. Even without oxygen or moisture, low glass transition temperature (Tg) materials undergo gradual molecular relaxation and crystallization, disrupting the optimized nanoscale phase separation and charge percolation pathways established during deposition. This is a bulk material issue, not solely an interfacial one.

Q2: During thermal annealing, my high-efficiency blend film becomes less uniform. What went wrong? A: Excessive or poorly controlled thermal annealing likely caused over-aggregation or destabilization of the metastable morphology. The annealing temperature probably exceeded the blend's effective Tg, allowing excessive molecular mobility that drives phase separation beyond the optimal length scale. Refer to the Thermal Annealing Protocol below for precise control.

Q3: My new OSC polymer has high performance but very low operational stability. How can I diagnose if Tg is the culprit? A: Perform a two-step test:

- Measure the Tg using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). See the protocol in the Experimental Protocols section.

- Conduct an accelerated aging test at a temperature just below and just above the measured Tg (e.g., Tg ± 15°C). Monitor hole/electron mobility over time. A stark drop in stability above Tg confirms its role. Quantitative data from recent studies is summarized in Table 1.

Q4: Can I improve morphological stability just by changing the processing solvent? A: Solvent choice primarily affects kinetics of morphology formation during drying (e.g., via boiling point, vapor pressure). It sets the initial morphology. However, long-term thermodynamic stability against dewetting or crystallization under operational stress (heat, light) is predominantly governed by the material's intrinsic properties, with Tg being a key metric. A good solvent can give a good starting point, but cannot overcome fundamentally unstable thermodynamics in a low-Tg material.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

- Objective: Accurately measure the Tg of a novel organic semiconductor material or blend.

- Materials: DSC instrument, hermetic aluminum pans and lids, microbalance, nitrogen gas supply, sample material (1-5 mg).

- Methodology:

- Preparation: Pre-dry the sample material under vacuum. Pre-treat pans and lids by heating to 500°C to remove organic contaminants.

- Loading: Precisely weigh 1-5 mg of sample into an aluminum pan. Crimp the lid hermetically using a sample press. Prepare an empty reference pan.

- Instrument Setup: Load pans into the DSC. Purge the cell with dry nitrogen (50 mL/min flow rate). Set a temperature program: Equilibrate at 25°C, then heat to 250°C at 20°C/min (1st heating, to erase thermal history), cool to 25°C at 20°C/min, then heat again to 250°C at 10°C/min (2nd heating, for measurement).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the second heating curve. Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step-change in heat capacity. Report the onset, midpoint, and endpoint temperatures.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Thermal Aging Test for Morphological Stability

- Objective: Quantify the degradation kinetics of OSC device performance under thermal stress.

- Materials: Complete OSC devices (e.g., OLEDs, OPVs), environmental chamber or hotplate with temperature control, probe station, semiconductor parameter analyzer.

- Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Characterize the initial performance of all devices (e.g., J-V curves, efficiency, mobility via SCLC or FET measurements).

- Aging: Place devices on a temperature-controlled hotplate or in an oven in an inert atmosphere (N2 glovebox). Set the aging temperature (Taging). Critical temperatures are: Taging < Tg (stable region), Tg < Taging < Tg+50°C (accelerated aging region).

- Monitoring: At defined time intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 6, 24, 96, 168 hours), remove samples, allow to cool to room temperature, and re-measure key performance parameters.

- Analysis: Plot normalized performance parameter (e.g., PCE, μh) vs. aging time. Fit the decay to a model (e.g., stretched exponential) to extract degradation rate constants.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Polymer Tg on Device Thermal Stability

| Polymer Donor | Tg (°C) | Acceptor | Initial PCE (%) | Aging Condition (Temp, Time) | PCE Retention (%) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT | ~12 | PCBM | 3.5 | 80°C, 24h | < 50% | Low Tg leads to rapid cold crystallization & phase separation. |

| PBDB-T | ~165 | ITIC | 9.5 | 85°C, 500h | > 95% | High Tg "locks" the morphology, enabling excellent thermal stability. |

| PM6 | ~205 | Y6 | 15.5 | 85°C, 300h | ~90% | Very high Tg suppresses molecular diffusion, stabilizing the blend. |

| PTQ10 | ~185 | IDIC | 12.5 | 120°C, 100h | > 80% | High-Tg polymer maintains nanoscale domains under severe heat stress. |

Note: Data is synthesized from recent literature (2021-2023).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg/Morphology Research |

|---|---|

| High-Tg Polymer Donors (e.g., PM6, D18) | Provide the high backbone rigidity necessary to elevate Tg and resist thermally induced deformation. |

| Cross-linkable Additives (e.g., P3HT-azide) | Can be blended into the active layer and subsequently activated (by heat/light) to form a stabilizing network, artificially raising the effective Tg. |

| Thermal Stabilizers (e.g., TRIS-NAs) | Radical scavengers that may slow degradation pathways linked to morphology changes initiated by chemical reactions. |

| High-Boiling Point Processing Solvents (e.g., o-DCB, CB) | Allow slower drying kinetics, facilitating the formation of a more thermodynamically favorable and stable initial morphology. |

| Solvent Additives (e.g., DIO, CN) | Modulate aggregation and phase separation during film formation to achieve an optimized initial nanostructure. |

| Encapsulation Epoxy/Glass Lid | Creates an inert microenvironment, isolating the device from oxygen/moisture to isolate purely morphological instability. |

Visualizations

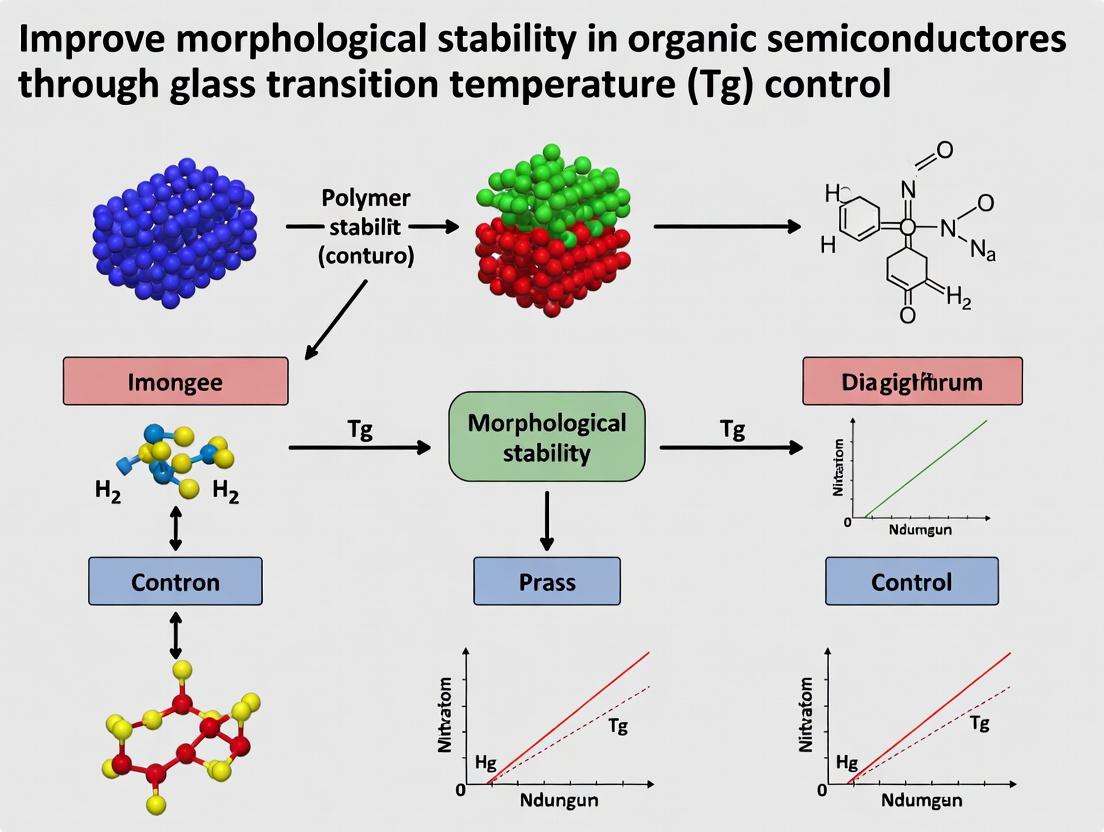

Title: Morphological Degradation Pathways in Low-Tg OSCs

Title: Tg Control Research Workflow

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My measured Tg for the same polymer batch varies significantly between DSC runs. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent Tg values in Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) are often due to sample preparation or instrument parameters.

- Check 1: Sample History. Ensure identical thermal history for all samples. Anneal samples above Tg for a set time (e.g., 10 min) followed by a controlled quench (e.g., in liquid N₂) to erase prior thermal memory.

- Check 2: Sample Mass & Pan. Use consistent, small sample masses (3-10 mg) in hermetically sealed pans to prevent solvent/plasticizer loss, which artificially lowers Tg.

- Check 3: DSC Scan Rate. Higher rates shift Tg to higher temperatures. Use a standardized rate (typically 10°C/min) for comparison. Use the table below for correction.

| Scan Rate (°C/min) | Approximate Tg Shift (Relative to 10°C/min) |

|---|---|

| 5 | -1 to -3°C |

| 10 | Reference |

| 20 | +2 to +4°C |

| 40 | +5 to +8°C |

Q2: My organic semiconductor film cracks or dewets when thermally annealed. How can Tg guide a solution? A: This is a core morphological stability issue. Cracking/dewetting occurs when annealing temperature (T_ann) exceeds the film's Tg, causing viscous flow.

- Diagnosis: Determine the Tg of your semiconductor:amorphous matrix blend via DSC.

- Protocol: To prevent instability, set your process T_ann to be below the measured Tg of the final film. If your device operation requires annealing above this Tg, you must modify the material.

- Solution (Thesis Context): Intentionally blend your semiconductor with a high-Tg polymer (e.g., polystyrene, T_g ~100°C) or a cross-linkable additive to elevate the composite film's effective Tg, freezing the desired morphology.

Q3: How do I accurately determine Tg from a DSC thermogram that shows a very subtle step change? A: Use standardized half-height or midpoint analysis protocols.

- Protocol:

- Obtain a flat baseline before and after the transition in your heat flow curve.

- Draw a tangent line along the flat baseline before the transition.

- Draw a second tangent line along the flat baseline after the transition.

- The Tg is reported as the midpoint temperature (where the curve is halfway between the two tangents) or the onset temperature (intersection of the first tangent with the curve's inflection tangent).

Q4: In drug development, why does the Tg of an amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) matter for shelf life? A: Tg is the primary indicator of physical stability. Below Tg, molecular mobility is low, inhibiting crystallization of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

- Rule of Thumb: Store the ASD at least 50°C below its Tg (T - T_g < -50°C) for long-term stability. Moisture absorption acts as a plasticizer, lowering Tg. Always measure Tg under dry conditions and use moisture-barrier packaging.

Q5: What is the most reliable method to measure Tg for thin films (<200 nm) where DSC lacks sensitivity? A: Use Spectroscopic Ellipsometry or Variable Angle Spectroscopic Ellipsometry (VASE) to measure the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE).

- Experimental Protocol:

- Deposit film on a silicon wafer substrate.

- Mount in a temperature-controlled stage within the ellipsometer.

- Heat the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 3-5°C/min) while measuring film thickness.

- Plot thickness vs. temperature. The CTE changes at Tg. The intersection of two linear fits (for glassy and rubbery states) defines the Tg with high precision for thin films.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Reagent/Material | Function in Tg Control Research |

|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | High-Tg (~100°C) polymeric additive used to rigidify blends and elevate composite Tg, stabilizing morphology. |

| 4,4'-bis(N-carbazolyl)-1,1'-biphenyl (CBP) | Common small-molecule organic semiconductor host; its low intrinsic Tg highlights need for blending/stabilization. |

| Divinyltetramethyldisiloxane-bis(benzocyclobutene) (BCB) | Cross-linkable additive. Upon heating, it forms a rigid network, dramatically increasing effective Tg post-cure. |

| Chlorobenzene / Toluene | Common solvents for organic semiconductors. Residual solvent plasticizes films, lowering Tg; rigorous vacuum drying is essential. |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | Medium-Tg (~105°C) polymer used as a gate dielectric or blending agent; its Tg provides a benchmark for thermal process windows. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Key instrument for bulk Tg measurement. Requires calibration with indium and zinc standards. |

Experimental Workflow: Enhancing Morphological Stability via Tg Engineering

Signaling Pathway: Molecular Mobility vs. Temperature at Tg

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: In our bulk heterojunction organic solar cell, we observe rapid phase segregation and a drop in PCE after thermal annealing at 110°C. What is the likely cause and how can we diagnose it? A: This is a classic symptom of annealing above the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the donor or acceptor material. Above Tg, molecular diffusion increases exponentially, leading to destabilization of the optimized nanomorphology.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Measure Tg: Perform Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) on your pristine donor and acceptor materials. Use a heating rate of 10 °C/min under N₂ purge. The midpoint of the transition in the second heat cycle is the operational Tg.

- Correlate with Annealing Temp: Compare your annealing temperature (110°C) to the measured Tg values.

- Characterize Morphology: Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in tapping mode to compare the surface morphology of devices annealed below and above the identified Tg. Coarsened features indicate excessive diffusion.

Q2: We synthesized a novel polymer with high Tg, but device performance is poor. How do we balance high Tg for stability with sufficient molecular mobility for processing and crystallization? A: High Tg alone is insufficient. You must engineer kinetic stability while allowing for controlled crystallization during initial processing.

- Solution Protocol:

- Use Processing Additives: Introduce a high-boiling-point solvent additive (e.g., 1-Chloronaphthalene) during film casting. This plasticizes the blend (temporarily lowers effective Tg) to enable molecular organization.

- Controlled Post-Solvent Annealing: After spin-coating, place the wet film in a covered Petri dish with a few drops of a solvent (e.g., THF, CS₂) for 1-5 minutes. This provides mobility for crystallization before the film vitrifies.

- Thermal Anneal Below Tg: Perform a final thermal anneal at a temperature 10-15°C below the measured Tg of the blend to relax stresses without enabling large-scale diffusion.

Q3: How do we accurately measure the Tg of a thin film (∼100 nm) instead of a bulk powder? A: Bulk DSC may not reflect thin-film Tg. Use spectroscopic or ellipsometric methods.

- Experimental Protocol: Spectroscopic Ellipsometry for Tg.

- Sample Prep: Prepare your organic semiconductor thin film on a silicon wafer substrate.

- Temperature Stage: Mount the sample in an ellipsometer with a controlled heating stage (inert atmosphere recommended).

- Data Collection: Heat the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 3-5 °C/min). Monitor the film thickness (or refractive index) as a function of temperature.

- Analysis: Plot thickness vs. temperature. The Tg is identified as the temperature at which the thermal expansion coefficient shows a discrete change (a clear kink in the plot), indicating the onset of large-scale segmental motion.

Q4: Our drug-polymer amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) is crystallizing during storage. How does Tg predict this, and how can we inhibit it? A: Crystallization occurs when storage temperature (T) exceeds the Tg of the ASD, enabling drug molecule diffusion and nucleation. The goal is to maximize Tg relative to storage conditions.

- Stabilization Protocol:

- Calculate/Measure Tg of ASD: Use the Gordon-Taylor equation for initial screening:

Tg(mix) = (w1Tg1 + K w2Tg2) / (w1 + K w2), where w is weight fraction and K is a fitting constant. Confirm with DSC. - Formulation Strategy: Select a polymer excipient (e.g., PVP-VA, HPMCAS) with a high Tg and that exhibits strong specific interactions (hydrogen bonds) with the API. This increases the Tg of the blend and reduces molecular mobility.

- Storage Rule: Ensure storage temperature is at least 50°C below the measured Tg of the ASD (the "Tg - 50" rule for long-term stability).

- Calculate/Measure Tg of ASD: Use the Gordon-Taylor equation for initial screening:

Table 1: Tg and Device Stability Metrics for Common Organic Semiconductor Materials

| Material | Tg (°C) [DSC] | Degradation Onset Temp (°C) [ISOS-D-2] | Recommended Max Processing Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT (rr-P3HT) | ~12 | 80 | 70 |

| PTB7 | 97 | 135 | 85 |

| PM6 (Donor Polymer) | 185 | >150 | 140 |

| ITIC (Non-fullerene Acceptor) | 149 | 130 | 120 |

| Y6 (Non-fullerene Acceptor) | 205 | >150 | 150 |

| PS (Insulating Reference) | ~100 | N/A | N/A |

Table 2: Impact of Tg on Diffusion Coefficient (D) in Model Polymer Films

| System (Film) | Tg (°C) | D at Tg+10°C (cm²/s) | D at Tg+50°C (cm²/s) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | 100 | 10⁻²⁰ | 10⁻¹⁶ | Fluorescence Recovery |

| PVK | 227 | 10⁻²⁵ | 10⁻²⁰ | Secondary Ion Mass Spec |

| Rule: | For T > Tg, log D ≈ A - (B/(T-Tg)) | (Vogel–Fulcher–Tammann Behavior) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg/Stability Research |

|---|---|

| High-Tg Polymer Matrices (e.g., Polyimide, PVK) | Used as stabilizing hosts or interlayers to physically suppress diffusion in blends. |

| Plasticizing Solvent Additives (e.g., DPE, CN) | Temporarily increase free volume during processing to aid ordering, then evaporate to restore high Tg. |

| Crosslinkable Precursors (e.g., TFB with azide groups) | Materials that can be processed from solution and then photo/thermally crosslinked to form an insoluble, high-Tg network. |

| Hydrogen-Bonding Additives (e.g., BP-4-VBP) | Small molecules that can selectively H-bond to polymer/API, reducing segmental mobility and raising blend Tg. |

| Fluorescent Molecular Probes (e.g., Nile Red) | Embedded in films; their mobility, measured via fluorescence quenching or recovery, directly probes local Tg and diffusion. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Tg-Guided Stability Optimization Workflow

The Direct Link: Tg, Diffusion, and Stability

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our bulk heterojunction (BHJ) organic solar cell shows a rapid drop in PCE within 100 hours of thermal aging at 80°C. Visual inspection shows haziness. What is the likely mechanism and how can we confirm it? A: The haziness strongly indicates crystallization of the polymer donor or small-molecule acceptor. This coarse phase separation destroys the nanoscale interpenetrating network. To confirm:

- Perform Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (GIWAXS) to detect increased crystalline coherence length and sharper diffraction peaks.

- Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in tapping mode to observe the formation of large (>100 nm) crystalline domains.

- Troubleshooting: Increase the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the active layer components. Select a polymer donor with a Tg above your device's operating temperature (e.g., >85°C). Incorporating a compatible high-Tg additive (like an insulating polymer) can suppress molecular mobility.

Q2: After solution processing and annealing, our organic photovoltaic (OPV) blend film shows excellent initial performance but degrades under continuous illumination. EQE data suggests a change in charge generation profile. What mechanism should we suspect? A: This points to vertical stratification or photo-induced phase separation. An initially optimal vertical composition gradient can degrade, leading to enrichment of one component at an electrode interface, blocking charge extraction.

- Confirm using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) depth profiling or Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy (GDOES). Compare fresh vs. light-soaked samples.

- Troubleshooting: Optimize solvent selection and drying kinetics. A slower drying process (e.g., using a higher boiling point solvent) can promote a more stable vertical distribution. Implement a solvent vapor annealing step to "lock in" a favorable morphology.

Q3: In our polymer:fullerene blend, we observe the formation of micrometer-sized, dark droplets under optical microscopy after shelf storage. What is this and how do we prevent it? A: This is macroscopic phase separation due to thermodynamic instability. The blend is likely metastable and undergoes Ostwald ripening or coalescence over time.

- Confirm by optical microscopy with UV excitation to check for fluorescence quenching in droplet regions.

- Troubleshooting: This is a core issue addressed by Tg control research. Modify the polymer side chains to increase backbone rigidity and raise Tg. Alternatively, use a cross-linkable fullerene derivative (e.g., PCBM with vinyl groups) to create a thermally stable, frozen network upon mild heating.

Q4: How can we quantitatively compare the morphological stability of different novel acceptor materials (e.g., Y-series vs. fullerene derivatives) under heat stress? A: Develop an accelerated aging test coupled with quantitative morphological metrics. See the protocol below.

Experimental Protocol: Accelerated Thermal Aging & Morphological Stability Quantification

Objective: To rank the intrinsic thermal stability of organic semiconductor blends by monitoring the evolution of domain size and purity under stress.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table.

Procedure:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate standard OPV devices (e.g., ITO/PEDOT:PSS/Active Layer/ZnO/Ag) using your candidate blends (e.g., PM6:Y6, PM6:PC71BM).

- Isothermal Aging: Place unpackaged devices on a hotplate in a nitrogen glovebox. Age sets of devices at a controlled temperature (e.g., 80°C, 100°C, 120°C).

- Timed Sampling: Remove devices at log-spaced time intervals (1h, 6h, 24h, 100h).

- Characterization:

- Electrical: Measure J-V characteristics to track PCE, FF, Jsc decay.

- Morphological: Perform Resonant Soft X-ray Scattering (R-SoXS) on aged active layers to quantify the domain size and relative domain purity. Extract the power spectral density and integrated scattering intensity.

- Data Fitting: Fit the decay of normalized PCE and domain purity over time to an Avrami equation to extract a degradation rate constant (k) and nucleation mechanism parameter (n).

Quantitative Data Summary:

Table 1: Degradation Rate Constants (k) for Various Blends at 80°C Aging

| Active Layer Blend | Initial PCE (%) | PCE after 100h (%) | Degradation Rate Constant k (h⁻ⁿ) | Avrami Exponent n | Dominant Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB7:PC71BM | 8.5 | 5.1 | 0.015 | ~1 (linear) | Crystallization & Vertical Stratification |

| PM6:Y6 | 16.2 | 15.0 | 0.003 | ~2 | Moderate Phase Separation |

| PM6:Y6 (with High-Tg Additive) | 15.8 | 15.3 | 0.001 | <1 | Suppressed |

Table 2: R-SoXS Morphological Metrics Before/After Aging (120°C, 24h)

| Blend | Condition | Median Domain Size (nm) | Integrated Scattering Intensity (a.u.) | Inferred Domain Purity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM6:ITIC | Fresh | 25 | 100 | High |

| PM6:ITIC | Aged | 42 | 65 | Lower |

| PM6:IDIC (High Tg) | Fresh | 28 | 105 | High |

| PM6:IDIC (High Tg) | Aged | 29 | 98 | High |

Diagrams

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Morphological Stability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| High-Tg Polymer Donor (e.g., D18) | Backbone rigidity suppresses chain diffusion, inhibiting crystallization and phase separation. | D18 (1-Material) |

| High-Tg Small Molecule Acceptor (e.g., IDIC) | Fused-ring core with bulky side groups elevates Tg, freezing morphology. | Y6-O-C18 (Solenne) |

| Cross-linkable Fullerene Derivative (e.g., V-PCBM) | Forms covalent network upon thermal/UV treatment, permanently locking morphology. | [60]V-PCBM (Nano-C) |

| High-Boiling Point Solvent Additive (e.g., DIO) | Modulates drying kinetics to optimize vertical phase distribution and suppress stratification. | 1,8-Diiodooctane (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Polymeric Stabilizing Additive (e.g., PS) | Insulating, high-Tg polymer that increases blend viscosity and Tg without disrupting electronic structure. | Polystyrene (Mw > 100k) (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Graphene Oxide Nanoplatelets | 2D physical barrier that impedes the diffusion and aggregation of organic molecules. | Dispersion in water/ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Metastable Morphology in Organic Semiconductors

This support center provides targeted guidance for researchers working on controlling glass transition temperature (Tg) to trap desirable metastable morphologies in organic semiconductors and related organic electronic materials, within the broader thesis goal of improving morphological stability.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During solvent annealing, my thin film crystallizes into the thermodynamically stable polymorph instead of the desired metastable one. How can I trap the metastable morphology? A: This indicates that the processing conditions provided sufficient molecular mobility to overcome kinetic traps. To trap the metastable phase:

- Control Solvent Vapor Pressure: Use a lower solvent vapor pressure or a weaker solvent to slow down the rate of crystallization, allowing finer control.

- Lower Processing Temperature: Perform the annealing at a temperature well below the Tg of the blend or the metastable phase itself, if known. This reduces chain mobility.

- Utilize a High-Tg Polymer Matrix: Blend your semiconductor with a high-Tg polymer (e.g., polystyrene). The rigid matrix can physically impede reorganization.

- Rapid Quenching: After annealing, rapidly remove the solvent source and, if possible, cool the substrate to "freeze" the structure before it can reorganize.

Q2: My device performance degrades over time as the film morphology changes. How can I assess if this is due to a low Tg? A: Perform an accelerated stability test coupled with thermal analysis.

- Protocol: Accelerated Aging & XRD/GIWAXS Monitoring:

- Prepare identical thin-film devices.

- Place them on a hot plate at a target temperature (e.g., 70°C, 90°C, 110°C) in an inert environment.

- Remove samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 72 hours).

- Use Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (GIWAXS) or XRD to monitor changes in crystalline packing and phase purity.

- Perform device I-V characterization on each aged sample.

- Correlate with DSC Data: Measure the Tg of your active layer blend using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). If device degradation onset temperatures correlate with or are above the measured Tg, it confirms that surpassing Tg is enabling detrimental reorganization.

Q3: How do I choose an effective high-Tg additive or polymer blend component for morphological stabilization? A: The additive must be compatible enough to mix but not so compatible that it plasticizes the semiconductor.

- Check for Miscibility: Use spectroscopic ellipsometry to check for a single, composition-dependent Tg in the blend, indicating miscibility.

- Avoid Plasticization: If the blend Tg is lower than that of the pure semiconductor, the additive is a plasticizer and is harmful for stability.

- Target an Elevated Tg: Select additives and blending ratios that yield a blend Tg above your target operational temperature (e.g., >80°C for normal operation, >120°C for processing stability).

Q4: In a donor-acceptor blend, which component's Tg is more critical for stabilizing the bulk heterojunction morphology? A: The Tg of the dominant, continuous phase typically governs stability. However, in an interpenetrating network, the lower Tg component is the weak link.

- Experimental Protocol: Local Tg Mapping via AFM-based Nanothermal Analysis:

- Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to identify distinct phases in your blend morphology.

- Employ a specialized thermal probe (nano-TA) to locally heat a specific domain (e.g., a polymer-rich region or an acceptor aggregate).

- Measure the local softening point as a function of temperature. This provides an estimate of the Tg of individual phases within the nanoscale morphology, identifying the stability-limiting component.

Data Presentation: Key Material Properties for Morphology Control

Table 1: Selected Organic Semiconductors and Common Additives with their Tg and Role

| Material Name | Class | Tg (°C) | Function in Morphology Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT | Donor Polymer | ~10-15 | Model low-Tg polymer; prone to crystallization & reorganization. |

| PTB7 | Donor Polymer | ~85 | Higher Tg than P3HT; offers better intrinsic thermal stability. |

| PS (Polystyrene) | Insulating Polymer | ~100 | High-Tg matrix additive to immobilize morphology. |

| PC71BM | Fullerene Acceptor | ~130 | High Tg; its diffusion often limits blend stability. |

| ITIC | Non-Fullerene Acceptor | ~170 | Very high Tg; can enhance thermal stability of blends. |

| DIO | Processing Additive | N/A | Solvent additive; controls kinetics of phase separation during drying. |

Table 2: Impact of Processing Temperature Relative to Tg on Outcome

| Processing Condition | Thermodynamic Drive | Kinetic Outcome | Trapped Morphology? |

|---|---|---|---|

| T process << Tg | Favors stable state | Extremely slow dynamics | Metastable or amorphous; very stable. |

| T process ≈ Tg | Favors stable state | Moderate dynamics | Metastable possible with precise control. |

| T process > Tg | Favors stable state | Fast dynamics | Stable phase; difficult to trap metastable. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Blend Tg via Modulated DSC Objective: Accurately measure the glass transition temperature of a donor:acceptor blend film.

- Sample Prep: Cast a uniform film (~5-10 mg solid) onto a Teflon sheet. Carefully peel and place multiple film layers into a standard aluminum DSC pan.

- Method: Use a modulated DSC program. Equilibrate at 30°C. Ramp at 3°C/min with a modulation amplitude of ±0.5°C every 60 seconds to 180°C.

- Analysis: In the reversing heat flow signal, identify the step transition. The midpoint of the step is reported as Tg.

Protocol: Solvent Vapor Annealing for Metastable Phase Trapping Objective: Achieve a metastable crystalline polymorph in a small-molecule organic semiconductor.

- Setup: Place the as-cast thin film in a sealed, temperature-controlled chamber with a reservoir of solvent (e.g., THF, chloroform).

- Control: Use a mass flow controller or needle valve to introduce a carrier gas (N2) saturated with solvent vapor. Monitor chamber temperature (Tchamber) precisely.

- Critical Step: Ensure Tchamber < Tg of the forming phase. This may require prior estimation.

- Annealing: Expose film for a controlled duration (minutes to hours).

- Quenching: Rapidly purge the chamber with dry N2 and cool the substrate to room temperature. Characterize immediately with in-situ or ex-situ GIWAXS.

Visualizations

Title: Kinetic Trapping of Morphology via Tg Control

Title: Experimental Workflow for Morphology Stabilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg/Morphology Research |

|---|---|

| High-Tg Polymer Additives (e.g., PS, PMMA) | Increases the blend's overall Tg, acting as a rigid matrix to suppress molecular diffusion. |

| Solvents with Different Boiling Points (e.g., CF, CB, o-Xylene) | Controls drying kinetics; high BP solvents allow slower drying, enabling more thermodynamic control. |

| Solvent Additives (e.g., DIO, CN, 1-Chloronaphthalene) | Selectively solubilizes one component to tune the kinetics of phase separation during film formation. |

| Cross-linkable Precursors | Can be polymerized or cross-linked after film formation to permanently "lock" the morphology. |

| Thermal Stabilizers (e.g., Radical Scavengers) | Prevents thermally-induced chemical degradation that can accompany morphological changes at high T. |

| Thick Glass Substrates / Hot Plates with PID Control | Ensures precise and uniform temperature control during annealing and stability testing. |

Strategic Tg Engineering: Molecular Design, Polymerization, and Blending Techniques

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My synthesized high-Tg conjugated polymer shows excellent thermal stability in TGA but still undergoes detrimental morphological changes in operational device stress tests. What could be the issue?

A: The thermal decomposition temperature (from TGA) and the glass transition temperature (Tg) are distinct. A high decomposition temperature does not guarantee a high Tg. Morphological instability under operation (e.g., at 70-85°C) is dictated by Tg. If your device operating temperature exceeds the material's actual Tg, molecular relaxation occurs despite thermal stability.

- Solution: Precisely measure Tg using modulated DSC (mDSC) to detect subtle transitions. Ensure your target Tg is at least 50°C above the intended maximum operating temperature of the device.

Q2: When I incorporate rigid, bulky side chains to boost Tg, my organic semiconductor's charge carrier mobility plummets. How can I balance these properties?

A: This is a classic trade-off. Excessive steric hindrance from bulky side chains can disrupt π-π stacking and backbone planarity, reducing electronic coupling.

- Solution: Implement a "linker" strategy. Use flexible spacers (e.g., alkyl chains) to connect the bulky side-group to the conjugated backbone. This decouples the morphological stabilizing function of the side chain from the electronic transport pathway. Alternatively, use side chains that can promote intermolecular non-covalent interactions (S···N, F···H) to enhance both order and Tg.

Q3: I am designing a high-Tg small molecule for OLEDs. Should I focus on increasing molecular weight or introducing specific chemical modifications?

A: For small molecules, molecular weight increase has a limit before processability suffers. Chemical design is paramount.

- Solution: Focus on:

- Asymmetric & Non-Planar Core Design: Replace symmetric, planar cores with twisted, asymmetric ones (e.g., spirobifluorene, tetrahedral carbon) to inhibit crystallization and pack into a high-Tg glass.

- Star-Shaped Architectures: Create branched, dendritic structures that frustrate efficient packing.

- High Dimensionality: Integrate 2D/3D structural elements (e.g., triptycene) that introduce internal free volume and rigidity.

Q4: My high-Tg polymer film becomes brittle and cracks, leading to device failure. How can I improve mechanical robustness without sacrificing Tg?

A: High crosslinking density or excessive rigidity can lead to brittleness.

- Solution: Integrate dynamic covalent bonds or supramolecular motifs (e.g., hydrogen bonding arrays, metal-ligand coordination) that provide a "self-healing" capability. These reversible bonds can dissipate mechanical stress while maintaining a high effective Tg. Alternatively, design block copolymers with a high-Tg rigid block and a flexible, ductile block.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) via Modulated DSC

Objective: To accurately determine the glass transition temperature of a conjugated polymer or small molecule film. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cast a uniform film (~5-10 mg solid) from a filtered solution onto a Teflon substrate. Dry thoroughly under vacuum at 80°C for 24 hours to remove residual solvent.

- Encapsulation: Precisely weigh the scraped film (5-10 mg) in a hermetic Tzero aluminum pan. Seal the pan with a Tzero lid using a press.

- mDSC Calibration: Calibrate the instrument for temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- Method Setup: Create a method with a modulated heating program:

- Equilibration: 0°C.

- Ramp: Heat to 250°C at 3°C/min with a modulation amplitude of ±0.5°C every 60 seconds.

- Purge Gas: Nitrogen at 50 mL/min.

- Run Experiment: Load the sample and an empty reference pan. Execute the method.

- Data Analysis: In the analysis software, separate the reversing heat flow signal. Identify the Tg as the midpoint of the step transition in the reversing heat flow curve, not the total heat flow.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Structural Modifications on Tg and Mobility of Representative Conjugated Polymers

| Polymer Core Structure | Side Chain / Modification | Reported Tg (°C) | Hole Mobility (cm²/Vs) | Key Trade-off / Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDTFT (Donor-Acceptor) | Linear 2-Decyltetradecyl | ~85 | 0.85 | Baseline, low Tg |

| PDTFT (Donor-Acceptor) | Branched 2-Octyldodecyl + Polystyrene Block | ~135 | 0.45 | Tg ↑, Mobility ↓ due to block |

| P3HT (Donor) | Grafted Cross-linkable Oxetane Group | >200 (after UV) | 0.02 | Tg ↑↑, Mobility ↓↓, High stability |

| P(NDI2OD-T2) (Acceptor) | Hybrid Alkyl-PEG Side Chain | ~175 | 0.55 (e⁻) | High Tg maintained, mobility preserved |

Table 2: High-Tg Small Molecule Design Strategies and Outcomes

| Molecule Class | Core Architecture | Tg (°C) | Application (Performance) | Morphological Stability (85°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trispiro | Three Spiro Centers | 167 | OLED (EQE: 8.2%) | >1000 hours (LT95) |

| Star-shaped | Tetrahedral Boron Core | 145 | OPV (PCE: 7.1%) | Stable, no dewetting |

| Dendritic | Carbazole Dendrons | 210 | OLET (Mobility: 0.01) | Excellent, but mobility low |

| Linear Asymmetric | Twisted Triptycene Core | 122 | OFET (Mobility: 0.4) | Stable for 500h |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: High-Tg Molecular Design Logic Flow

Diagram 2: mDSC Workflow for Tg Measurement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Hermetic Tzero Pans & Lids (Aluminum) | Prevents sample sublimation/decomposition and ensures uniform thermal contact during mDSC. Essential for volatile materials. |

| Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimeter (mDSC) | Separates reversible (Tg) from non-reversible (enthalpy relaxation, evaporation) thermal events, giving a clearer Tg signal. |

| Anhydrous, Degassed Solvents (e.g., Toluene, Chloroform) | For film casting. Prevents side reactions (e.g., with water) that could alter polymer molecular weight or end-groups, affecting Tg. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glovebox | For sample preparation and encapsulation. Prevents oxidation of sensitive conjugated materials during processing. |

| Polystyrene or Indium Standards | For precise calibration of the mDSC temperature and heat capacity scale, ensuring accurate Tg reporting. |

| Crosslinker Additives (e.g., photo-active, thermal) | Used to post-process films to create a crosslinked network, dramatically increasing effective Tg after film formation. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Synthesis & Processing Issues

Q1: My polymer with long, branched alkyl side chains exhibits excellent solubility but excessively low glass transition temperature (Tg), leading to morphological instability during thermal annealing. How can I increase Tg without sacrificing too much solubility? A1: This is a classic trade-off. Consider these strategies:

- Introduce rigid side-chain linkers: Replace flexible alkyl spacers (e.g., -C6H12-) with semi-rigid linkers like thiophene or phenyl rings between the backbone and the solubilizing end-group. This restricts side-chain mobility, increasing Tg.

- Incorporate hydrogen-bonding groups: Add mild H-bonding moieties (e.g., ester, amide) within the side chain. This introduces intermolecular interactions that raise Tg, but use sparingly to avoid catastrophic loss of solubility.

- Employ asymmetric/bulky side chains: Use bulkier, asymmetric end-groups (e.g., 2-octyldodecyl) instead of linear n-alkyl chains. This can disrupt crystalline packing enough for solubility while maintaining a higher Tg than highly symmetric, crystallizing side chains.

Q2: During device fabrication, my high-Tg material forms poor-quality, non-uniform films from chlorinated solvents. What processing adjustments can improve film morphology? A2: Poor film formation in high-Tg materials often stems from overly rapid solvent evaporation and insufficient chain mobility.

- Solvent Engineering: Switch to a higher-boiling-point solvent (e.g., from chloroform to o-dichlorobenzene) or use a solvent mixture (e.g., chloroform + 5% o-xylene). This allows more time for molecular reorganization.

- Pre- & Post-Processing Temperature: Ensure your substrate is heated to a temperature just below the material's Tg during spin-coating (e.g., 80°C for a Tg of 100°C). Follow with a slow, controlled thermal annealing step, ramping from room temperature to just above Tg, holding, then cooling slowly.

- Additive Use: Incorporate a high-boiling-point additive (e.g., 1,8-diiodooctane at 1-3% v/v) to modulate drying dynamics and promote phase separation.

Q3: My side-chain engineered polymer shows promising thermal stability (high Tg) but its charge carrier mobility has dropped significantly compared to the reference material. What could be the cause? A3: Reduced mobility often indicates disrupted π-π stacking due to suboptimal side-chain engineering.

- Check Side-Chain Bulk/Position: Excessively bulky side chains or those attached too close to the conjugated backbone can create a steric barrier, pushing backbones apart and increasing π-π stacking distance. Consider moving the attachment point or using linear alkyl segments proximal to the backbone.

- Analyze Packing Mode: Use GIWAXS to determine if the packing has shifted from a favorable "face-on" to a "edge-on" orientation relative to the substrate, which is less beneficial for vertical charge transport in many devices.

- Investigate Crystallinity: A very high Tg sometimes correlates with excessive amorphous character. Aim for a balance—sufficient rigidity for stability but some capacity for self-organization. Introducing planar backbones can help compensate.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Optimum Annealing Temperature Relative to Tg

Objective: To establish a thermal annealing protocol that optimizes morphology without inducing destabilization in a new side-chain engineered semiconductor.

Materials:

- Thin-film samples of the polymer on desired substrates.

- Hotplate or oven with precise temperature control (±1°C).

- Glovebox or inert atmosphere environment (N2 or Ar).

- Characterization tools: AFM, GIWAXS, FET or OPV device testing setup.

Methodology:

- Tg Determination: First, determine the material's Tg via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). Use a slow heating/cooling rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Tg is identified as the midpoint of the heat capacity transition.

- Annealing Matrix: Prepare multiple identical film samples. Anneal each at a different temperature (Ta) for a fixed time (e.g., 10 minutes). Suggested Ta: Tg - 40°C, Tg - 20°C, Tg, Tg + 10°C, Tg + 20°C, Tg + 40°C.

- Inert Atmosphere: Perform all annealing in an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation.

- Morphological Analysis: Use AFM to assess film roughness and domain formation. Use GIWAXS to quantify crystalline coherence length and π-π stacking distance.

- Device Performance: Integrate films into devices (e.g., OFETs or OPVs) and measure key performance parameters (mobility, PCE).

- Stability Test: Subject the optimized device to extended heating (e.g., 100 hours) at a temperature slightly below its Tg and monitor performance decay.

Quantitative Data Summary: Common Side-Chain Modifications and Their Effects

Table 1: Impact of Side-Chain Modifications on Key Parameters

| Side-Chain Type | Example Structure | Solubility | Tg Trend | π-π Stacking Distance | Typical Mobility Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Alkyl (C8-C12) | n-Octyl, n-Decyl | High | Low | Medium (~3.6-3.8 Å) | Baseline (High) |

| Branched Alkyl (Asym.) | 2-Ethylhexyl, 2-Octyldodecyl | Very High | Very Low | Often Increases | Moderate Decrease |

| Oligo(Ethylene Glycol) | -O-(CH2-CH2-O)n-CH3 | High | Variable (can be higher) | Increases | Significant Decrease |

| Hybrid w/ Aromatic Spacer | -C6H4-C6H13 | Moderate | High | Can Decrease (~3.5 Å) | Maintained or Improved |

| Siloxane-Terminated | -C6-Si(CH3)3 | High | Medium-High | Variable | Moderate |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms and Solutions

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Suggested Experimental Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Solubility | Side chains too short/rigid; Excessive backbone planarity | Synthesize copolymer with solubilizing comonomer; Increase alkyl chain length. |

| Low Tg (< 100°C) | Excessively flexible, long alkyl side chains | Introduce cyclic/aromatic elements into side chain; Use cross-linkable groups. |

| Low Crystallinity | Side chains too bulky or irregular | Simplify side chain to linear or symmetrically branched; Use solvent vapor annealing. |

| High Mobility but Poor Stability | Tg too low for application temperature | Implement side-chain strategy from FAQ A1 to raise Tg while preserving packing. |

| Film Dewetting | High Tg material + low boiling solvent | Use solvent engineering (see Protocol); Increase substrate temperature during casting. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| o-Dichlorobenzene (ODCB) | High-boiling-point (180°C) solvent for processing high-Tg materials; promotes better film formation. |

| 1,8-Diiodooctane (DIO) | High-boiling-point additive (332°C) used in OPV processing to control donor:acceptor phase separation dynamics. |

| Anisole | Aromatic, medium-boiling-point (154°C) solvent, greener alternative to chlorobenzene for scale-up. |

| Polystyrene (PS) Standards | Used for GPC calibration to determine molecular weight (Mn, Mw), a critical factor influencing Tg and morphology. |

| Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl3) / 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane-d2 (TCE-d2) | NMR solvents for characterizing side-chain incorporation and polymer purity. TCE-d2 is essential for high-temperature NMR of rigid polymers. |

| Silane-based Self-Assembled Monolayers (e.g., OTS, HMDS) | Substrate treatments to modify surface energy, critically influencing thin-film crystallization and orientation. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Kit | Hermetic aluminum pans and lids for accurate Tg measurement, preventing solvent loss/decomposition. |

Visualization: Experimental Workflow for Side-Chain Engineering Iteration

Diagram Title: Side-Chain Engineering Development & Testing Cycle

Visualization: Key Trade-Offs in Side-Chain Engineering

Diagram Title: The Core Triad of Side-Chain Engineering

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During the synthesis of a ladder-type polymer, I observe significant insolubility in common organic solvents, halting my progress. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A1: This is a common issue in backbone rigidification. The primary cause is excessive planarization and strong intermolecular π-π stacking, which reduces solvent accessibility.

Solutions:

- Incorporate Solubilizing Side Chains: Introduce or elongate alkyl (e.g., branched 2-decyltetradecyl) or alkoxy side chains before the final cyclization/ladderization step.

- Optimize Cyclization Conditions: Ensure your cyclization reaction (e.g., Friedel-Crafts, lactonization) is fully complete. Partial cyclization can lead to cross-linked, insoluble networks. Use high-temperature NMR or MALDI-TOF to confirm complete reaction.

- Fractionate the Product: Use sequential Soxhlet extraction with solvents of increasing polarity (hexane, toluene, chloroform, o-dichlorobenzene) to isolate the soluble fraction with the desired molecular weight.

Q2: My fused-ring core small molecule exhibits a lower-than-expected glass transition temperature (Tg) despite a rigid structure. How can I enhance Tg for improved morphological stability?

A2: Tg depends on both backbone rigidity and intermolecular interactions.

Diagnosis and Protocol:

- Measure Tg Correctly: Use a slow heating rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min) on a DSC (Differential Scanning Calorimeter) to avoid missing the transition. Use the second heating cycle to erase thermal history.

- Enhance Intermolecular Forces: Introduce polar functional groups (e.g., cyano, fluorine) or heteroatoms (e.g., nitrogen in aza-cores) that can promote dipole-dipole interactions or hydrogen bonding without compromising planarity.

- Increase Molecular Weight: For polymeric systems, ensure high molecular weight (Mn > 30 kDa). For small molecules, consider strategic dimerization or oligomerization to reduce molecular mobility.

Q3: I am seeing batch-to-batch variation in the field-effect transistor (FET) performance of my fused-ring semiconductor. What experimental parameters in synthesis and processing are most critical to control?

A3: Reproducibility hinges on precise control of synthesis purity and thin-film processing.

Critical Controls:

- Synthesis: Purify all starting materials (e.g., via recrystallization or sublimation for core building blocks). Use an inert atmosphere (N2 or Ar glovebox) for moisture/oxygen-sensitive metal-catalyzed coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Stille).

- Purification: For final compounds, use train sublimation (for small molecules) or sequential precipitation/fractionation (for polymers) to achieve >99.5% purity. Monitor by HPLC.

- Processing: Standardize solution concentration, solvent boiling point, spin-coat speed, and, most critically, post-deposition annealing temperature and time. Use a calibrated hotplate in a nitrogen environment.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Model Ladder-Type Polymer via Friedel-Crafts Alkylation

- Objective: To synthesize a diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP)-based ladder polymer.

- Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table.

- Steps:

- Dissolve the linear DPP precursor polymer (100 mg) in dry 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (10 mL) in a flame-dried Schlenk flask.

- Add a catalytic amount of trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFSA) (10 µL) via syringe under argon.

- Stir the reaction mixture at 120°C for 24 hours.

- Cool to room temperature and precipitate the polymer into a 10:1 mixture of methanol and hydrochloric acid (200 mL).

- Collect the solid via filtration and subject it to sequential Soxhlet extraction (methanol, acetone, hexane, chloroform).

- The chloroform fraction is concentrated, precipitated in methanol, and dried under vacuum to yield the ladder polymer.

Protocol 2: Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

- Objective: Accurately measure Tg of a fused-ring core semiconductor.

- Instrument: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

- Steps:

- Accurately weigh 3-5 mg of sample into a hermetic aluminum DSC pan and seal it.

- Load the pan into the DSC. Run a heat/cool/heat cycle under N2 flow (50 mL/min).

- First Heat: Ramp from 25°C to 350°C at 20°C/min (to erase thermal history).

- Cool: Ramp from 350°C to 25°C at 50°C/min.

- Second Heat (Analysis Cycle): Ramp from 25°C to 350°C at 10°C/min.

- Analyze the second heating curve. Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step transition in the heat flow curve.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Backbone Rigidification on Thermal and Electronic Properties

| Material Class | Example Core | Tg (°C) | Hole Mobility (cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Synthetic Yield Key Challenge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Conjugated Polymer | PBTTT | ~150 | 0.5 - 0.8 | Moderate | Crystallinity control |

| Ladder-Type Polymer | Ladder-PPP | >300 | 0.1 - 0.3 | Low | Solubility, defect-free synthesis |

| Fused-Ring Small Molecule | DNTT | ~100 | 2.0 - 5.0 (single crystal) | High | Purification, thin-film uniformity |

| Fused-Ring Oligomer | 6T | ~180 | 0.5 - 1.5 | Moderate | Molecular weight distribution |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Rigidification Strategies | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Trifluoromethanesulfonic Acid (TFSA) | Strong Brønsted acid catalyst for intramolecular Friedel-Crafts cyclization (ladderization). | Handle with extreme care in a fume hood. Must be anhydrous. |

| 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane | High-boiling, non-coordinating solvent for high-temperature polymer cyclization reactions. | Classified as toxic; requires proper waste disposal. |

| 2-Decyltetradecyl Bromide | Source of long, branched alkyl side chain for imparting solubility to rigid backbones. | Used in alkylation reactions before ladderization. |

| Palladium Tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) | Catalyst for Suzuki or Stille cross-coupling to build fused-ring cores and precursors. | Sensitive to air; store under inert atmosphere. |

| Chlorobenzene / o-Dichlorobenzene | High-boiling point processing solvents for spin-coating rigid semiconductors. | Promotes ordered thin-film morphology during slow drying. |

| Train Sublimation Apparatus | Purification method for fused-ring small molecules to achieve ultra-high purity (>99.9%). | Critical for removing charge-trapping impurities. |

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for Developing Morphologically Stable OSC

Diagram 2: Relationship between Structure, Tg, and Stability

The Role of Molecular Weight and Polydispersity in Determining Bulk Tg

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my measured bulk Tg deviate significantly from literature values for the same polymer?

- Answer: This is often due to uncontrolled molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and polydispersity index (PDI). Literature values typically reference a specific, narrow molecular weight fraction. If your polymer batch has a lower Mn than expected, the Tg will be lower due to increased chain-end mobility. A high PDI (>1.5) means your sample contains both low and high molecular weight chains, leading to a broadened and less distinct Tg transition as measured by DSC. To resolve this, characterize your material using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) to confirm Mn and PDI before Tg analysis.

FAQ 2: My DSC thermogram shows a very broad glass transition, making Tg assignment difficult. What is the cause and solution?

- Answer: A broad Tg transition is a classic symptom of high polydispersity. A wide distribution of chain lengths results in a distribution of segmental mobilities, smearing the transition. To obtain a clearer Tg:

- Fractionate your polymer sample using preparatory GPC or solvent/non-solvent techniques.

- Analyze fractions separately by DSC. You should observe sharper transitions in lower PDI fractions.

- Ensure your DSC heating rate is appropriate (typically 10 °C/min) and that the sample is properly annealed to remove thermal history.

FAQ 3: How do I experimentally isolate the effect of molecular weight from the effect of polydispersity on Tg?

- Answer: You must create or obtain a series of polymer samples with controlled characteristics.

- Synthesize or source a series of samples with near-identical chemical structure but varying, monodisperse molecular weights (PDI < 1.1). This allows you to establish the fundamental Mn-Tg relationship.

- Blend polymers intentionally. Create binary blends of a high-Mn and a low-Mn fraction of the same polymer to systematically vary PDI while keeping weight-average molecular weight (Mw) constant. Measuring Tg of these blends reveals the pure polydispersity effect.

FAQ 4: For organic semiconductor thin films, the measured Tg often differs from the bulk polymer Tg. Why?

- Answer: Thin film confinement and substrate interactions can alter chain mobility. However, the underlying principles still apply: the molecular weight and dispersity of your semiconductor polymer are foundational. A low-Mn polymer will always have a lower intrinsic Tg, making it more susceptible to morphological instability (e.g., phase separation, crystallization) at device operating temperatures. Always report the bulk Tg (from a thick, free-standing film or powder) as the material property baseline, then investigate thin-film deviations.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Molecular Weight Dependence of Tg (Fox-Flory Relationship) Objective: To establish the relationship between number-average molecular weight (Mn) and bulk Tg for a homologous polymer series. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Method:

- Obtain or synthesize at least 5 polymer samples with varying, monodisperse Mn (PDI < 1.2) and identical chemical structure.

- Determine the exact Mn and PDI for each sample using GPC/SEC calibrated with appropriate standards.

- For each sample, prepare a bulk specimen (~5-10 mg) for Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

- Run DSC using a standard protocol: equilibrate at 50°C below expected Tg, heat at 10°C/min to 50°C above Tg, cool at 20°C/min, and re-heat at 10°C/min. Record data from the second heat.

- Determine the midpoint Tg for each sample from the second heat cycle.

- Plot Tg (y-axis) vs. 1/Mn (x-axis). Fit the data to the Fox-Flory equation: Tg = Tg∞ - K/Mn, where Tg∞ is the infinite molecular weight Tg and K is a constant.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Effect of Polydispersity on Tg Transition Breadth Objective: To correlate the width of the glass transition (ΔTg) with the Polydispersity Index (PDI). Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Method:

- Obtain a parent polymer with high PDI (>2.0).

- Fractionate this polymer using preparatory-scale GPC or solvent/non-solvent fractionation to collect at least 4 fractions with varying, narrower PDI.

- Characterize the Mn, Mw, and PDI of each fraction using analytical GPC.

- Analyze each fraction by DSC using the protocol described in Protocol 1.

- For each DSC thermogram, determine the onset (Tg,onset) and offset (Tg,offset) temperatures of the glass transition step. Calculate ΔTg = Tg,offset - Tg,onset.

- Plot ΔTg (y-axis) vs. PDI (x-axis) for all fractions. Expect a positive correlation.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Example Data for Molecular Weight Dependence of Tg in a Model Polymer (e.g., PS)

| Sample ID | Mn (g/mol) | PDI (Đ) | Bulk Tg (°C) [Midpoint] | Tg,onset (°C) | Tg,offset (°C) | ΔTg (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS-Low | 3,500 | 1.08 | 65.2 | 61.0 | 69.5 | 8.5 |

| PS-Med | 25,000 | 1.05 | 98.7 | 96.0 | 101.5 | 5.5 |

| PS-High | 150,000 | 1.03 | 104.1 | 102.5 | 105.8 | 3.3 |

| PS-Broad | 75,000 | 2.40 | 100.3 | 92.5 | 108.0 | 15.5 |

Table 2: Key Parameters from Fox-Flory Analysis of Hypothetical Data

| Polymer System | Tg∞ (°C) | K (g·K/mol) | R² of Fit | Relevance to OSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (Model) | 105.0 | 1.5 x 10⁵ | 0.998 | Fundamental model |

| P3HT (Semiconductor) | 85.0* | 2.8 x 10⁵* | N/A | Directly impacts blend stability |

| PTAA (Semiconductor) | 120.0* | 3.0 x 10⁵* | N/A | High Tg desired for thermal stability |

*Representative values from literature; actual values vary by synthesis.

Diagrams

Title: How Molecular Properties Dictate Bulk Tg and Morphological Stability

Title: Experimental Workflow for Tg-MW-PDI Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Narrow Dispersity Polymer Standards | Calibrate GPC/SEC for accurate Mn, Mw, PDI determination. Essential for quantitative comparison. |

| Anhydrous, Inhibitor-Free Solvents (e.g., TCB, Chloroform) | For GPC analysis and sample preparation. Water or stabilizers can affect polymer solution properties and Tg. |

| Hermetic DSC Pans (Tzero recommended) | Ensure no solvent loss or oxidative degradation during Tg measurement, which can artificially broaden or shift the transition. |

| Calibration Standards (Indium, Zinc) | Calibrate DSC temperature and enthalpy scales before measurement for accurate, reproducible Tg values. |

| Preparatory GPC Columns or Fractionation Glassware | To isolate polymer fractions of specific molecular weight ranges, enabling the study of isolated PDI effects. |

| Thermal Analysis Software (e.g., TA Universal, Pyris) | For accurate determination of Tg midpoint, onset, and offset from DSC thermograms using consistent algorithms. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges encountered when using high glass transition temperature (Tg) matrices to stabilize active components, such as organic semiconductor molecules or amorphous solid dispersion-based drug formulations. The content is framed within the thesis research on Improving morphological stability in organic semiconductors through Tg control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: During hot-melt extrusion blending of our API with a high-Tg polymer, we observe uneven dispersion and potential degradation. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: Uneven dispersion often results from a mismatch between the processing temperature (Tprocess), the Tg of the blend, and the degradation temperature (Tdeg) of the active component.

- Cause 1: Tprocess is set below the effective Tg of the blend, preventing adequate molecular mixing.

- Solution: Calculate or measure the Tg of the blend using the Gordon-Taylor equation. Ensure Tprocess > Tg,blend + 50°C for sufficient polymer chain mobility.

- Cause 2: Tprocess is too close to the Tdeg of the API.

- Solution: Incorporate a plasticizer (e.g., TPGS, triacetin) to lower the blend Tg, allowing a lower Tprocess. Always perform TGA/DSC on individual components first.

Q2: Our stabilized film shows excellent initial performance, but the active component crystallizes after 4 weeks of storage at 25°C/60%RH. Is the high-Tg matrix failing?

A: Not necessarily. Crystallization indicates that the storage temperature (Tstorage) is above the kinetic Tg of the formulation, allowing molecular mobility over time.

- Investigation Step 1: Measure the Tg of the aged film via DSC. Compare it to the initial Tg. A decrease suggests phase separation or moisture absorption (which plasticizes the matrix).

- Investigation Step 2: Check the

T<sub>storage</sub> / T<sub>g</sub>ratio. For long-term stability, this ratio should typically be < 0.95. If Tg is 70°C (343K), then Tstorage should be below ~50°C. - Solution: Increase the Tg of the matrix further by choosing a polymer with higher intrinsic Tg (e.g., from polyvinylpyrrolidone [PVP, Tg~150°C] to polyacrylates like Eudragit RL [Tg>200°C]) or by adding an antiplasticizing agent.

Q3: We aim to stabilize a small-molecule organic semiconductor. How do we select a high-Tg matrix based on quantifiable parameters?

A: Selection is based on compatibility and thermodynamic/kinetic parameters. Use the following table to compare common matrices.

| Matrix Material | Typical Tg (°C) | Relevant Solubility Parameter (δ, MPa¹/²) | Key Functional Group for Interaction | Typical Load Capacity (wt% API) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | 95 - 105 | 18.5 - 19.0 | Aromatic ring (π-π stacking) | 10-30% |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | 105 - 120 | 18.5 - 19.5 | Carbonyl (dipole-dipole) | 20-40% |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K30) | ~150 | 23.0 - 25.0 | Lactam group (H-bond acceptor) | 25-50% |

| Poly(vinylcarbazole) (PVK) | ~225 | 20.5 - 21.5 | Carbazole (π-π, hole transport) | 15-35% |

| SU-8 Epoxy Polymer | >200 | 20.0 - 22.0 | Epoxy, aromatic (cross-linked) | 5-20% |

Selection Protocol: 1) Calculate or obtain the Hansen solubility parameter (δD, δP, δH) of your active component. 2) Choose a matrix with a similar total δ for better miscibility. 3) Verify by casting a thin film from a common solvent and analyzing by AFM/PLM for homogeneity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal Blending Ratio via Film Casting and Stability Testing

Objective: To find the minimum polymer content required to completely suppress crystallization of the active component under accelerated conditions.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table below. Method:

- Prepare co-dissolved solutions of the active component and high-Tg polymer in a common anhydrous solvent (e.g., toluene, chloroform) at varying weight ratios (e.g., 90:10, 70:30, 50:50 API:Polymer).

- Cast films onto cleaned glass or Si/SiO2 substrates using a spin-coater (e.g., 1000 rpm for 60 sec).

- Anneal films on a hotplate at Tanneal = Tg,blend + 10°C for 1 hour to remove solvent and equilibrate.

- Characterize initial state using polarized optical microscopy (POM) and UV-Vis/PL spectroscopy.

- Subject films to accelerated aging: 60°C in a controlled atmosphere oven for 24-72 hours.

- Re-characterize using POM and spectroscopy. The lowest polymer content sample that shows no birefringence (crystals) and no spectral shift is the optimal ratio.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Blend Homogeneity and Phase Stability via Modulated DSC (mDSC)

Objective: To detect a single, composition-dependent Tg and the absence of melting endotherms, confirming a homogeneous amorphous blend.

Method:

- Prepare bulk blended samples via solvent evaporation or mini-compounder.

- Load 5-10 mg of sample into a hermetically sealed DSC pan.

- Run mDSC method: Equilibrate at 0°C, modulate ±0.5°C every 60 sec, heat at 2°C/min to 250°C (or above polymer Tg).

- Analyze the reversing heat flow signal. A single, broadened Tg step that shifts with composition confirms a miscible blend. Multiple Tgs indicate phase separation.

- The non-reversing heat flow signal should show no sharp melting endotherm of the crystalline API.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Stabilized Blend Development Workflow (77 chars)

Diagram 2: Stability Decision Based on Tg & Storage T (58 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK) | A high-Tg (>200°C) hole-transport polymer. Used as a matrix for organic semiconductor stabilization via π-π interactions with aromatic actives. |

| DMSO-d⁶ / Chloroform-d | Deuterated solvents for NMR studies to investigate specific intermolecular interactions (e.g., H-bonding) between API and polymer. |

| Diphenylanthracene (DPA) | A model fluorescent active component for proof-of-concept studies in morphological stabilization and energy transfer. |

| Triethyl Citrate | A common plasticizer. Used in small amounts to fine-tune the blend Tg and processability without compromising stability. |

| Molecular Sieves (3Å) | Used to keep solvents and glovebox atmospheres anhydrous, preventing moisture-induced plasticization during processing. |

| Hot-Stage Polarized Optical Microscope | Essential for real-time observation of crystal nucleation and growth in thin films under controlled temperature. |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D) | Used to study real-time thin film swelling, moisture uptake, and viscoelastic changes under different RH conditions. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in Tapping Mode | Provides nanoscale topographic and phase-contrast images to detect early-stage phase separation before bulk crystallization. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: After applying a thermal crosslinking treatment, my organic semiconductor film shows a drastic drop in charge carrier mobility. What went wrong? A: This is often due to excessive crosslinking density or degradation of the semiconducting core. Overly dense networks can distort the π-conjugated system, disrupting charge transport pathways.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the crosslinking agent concentration and thermal budget (time/temperature). Reduce by 20% increments.

- Analyze film morphology via AFM for excessive roughness or pinholes indicating phase separation.

- Use FTIR or XPS to confirm complete reaction of crosslinking groups and check for unintended side reactions with the semiconductor backbone.

Q2: My crosslinked film exhibits poor adhesion and delaminates from the ITO/glass substrate during solvent annealing. How can I improve adhesion? A: Delamination indicates weak interfacial bonding between the crosslinked network and the substrate.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Surface Pre-treatment: Implement a rigorous substrate cleaning protocol (UV-Ozone, oxygen plasma) to increase surface energy.

- Use an Adhesion Promoter: Apply a self-assembled monolayer (e.g., hexamethyldisilazane for oxide surfaces or a trichlorosilane-based primer) before film deposition.

- Modify Crosslinker Chemistry: Incorporate a small fraction (1-5 mol%) of a crosslinker with polar or silane anchoring groups to promote substrate bonding.

Q3: I observe inconsistent film quality and crosslinking efficiency between different batches. How can I improve reproducibility? A: Inconsistency typically stems from environmental variables or reagent instability.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Control Atmosphere: Perform all spin-coating and crosslinking steps in a controlled, dry nitrogen or argon glovebox (<0.1 ppm O₂, <0.1 ppm H₂O).

- Standardize Solution Age: Note the shelf-life of your crosslinking agent solution. Prepare fresh solutions or establish a validated "use-by" time.

- Calibrate Equipment: Ensure hotplates are calibrated for temperature uniformity and spin-coaters for precise rpm.

Q4: The chosen crosslinking chemistry reacts prematurely during solution processing, causing nozzle clogging in inkjet printing. How can I prevent this? A: This indicates poor orthogonality between the semiconductor and crosslinker under processing conditions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Switch to Photo-crosslinking: Replace thermal crosslinkers with photo-activated ones (e.g., benzophenone, azide derivatives). Process in the dark until the post-deposition UV exposure step.

- Use a Latent Catalyst: Employ a thermally activated catalyst (e.g., thermoacid generators) that remains inert until a specific post-printing bake temperature is reached.

- Optimize Ink Formulation: Increase solvent polarity to stabilize the reactive components temporarily.

Experimental Protocol: Photo-initiated Crosslinking of a Polymeric Semiconductor for Morphology Locking

Objective: To lock the morphology of a PBTTT-based film post-deposition using a UV-initiated crosslinking strategy, within the context of enhancing morphological stability via increased network Tg.

Materials:

- Semiconductor: Poly(2,5-bis(3-tetradecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene) (PBTTT)

- Crosslinker: 1,6-Bis(trimethoxysilyl)hexane (BTMSH)

- Photo-initiator: (2-Benzyl-2-dimethylamino-1-(4-morpholinophenyl)butanone-1) (Irgacure 369)

- Solvent: Anhydrous chlorobenzene

- Substrate: PEDOT:PSS/ITO-coated glass.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a 10 mg/mL solution of PBTTT in chlorobenzene. Separately, prepare a 50 mg/mL solution of BTMSH and 5 mg/mL of Irgacure 369 in chlorobenzene. Mix the solutions to achieve a final blend with a PBTTT:BTMSH:Irgacure weight ratio of 100:20:2. Stir in the dark for 12 hours.

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the blended solution onto pre-cleaned (UV-Ozone, 20 min) substrates at 1500 rpm for 60s in a nitrogen glovebox.

- Solvent Annealing: Immediately transfer the wet film to a Petri dish with a few drops of chlorobenzene solvent. Cover and let it anneal in saturated vapor for 5 minutes to develop optimal morphology.

- Morphology Locking: Transfer the film to a UV chamber (λ=365 nm, 15 mW/cm²). Irradiate under N₂ atmosphere for 5 minutes to initiate the sol-gel condensation of BTMSH, creating a siloxane network around the PBTTT domains.

- Post-Cure: Bake the film on a hotplate at 100°C for 30 minutes to complete the crosslinking reaction.

- Validation: Perform AFM to confirm morphology preservation before/after washing with a strong solvent (e.g., chloroform). Use FTIR to monitor the disappearance of Si-OCH₃ peaks (~2840 cm⁻¹).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Crosslinking Strategies on Film Stability and Device Performance

| Crosslinking System | Tg of Network (°C) | Mobility Pre-Wash (cm²/V·s) | Mobility Post-Wash (cm²/V·s) | Morphology Retention (AFM RMS) | Optimal Processing Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Benzocyclobutene | ~220 | 0.45 | 0.42 | >95% | 210 |

| UV-Activated Azide | ~180 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 98% | 80 |

| Sol-Gel Siloxane (BTMSH) | >250 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 99% | 100 |

| No Crosslink (Control) | ~80 | 0.50 | <0.01 | <10% | N/A |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Crosslinking Failures

| Observed Problem | Potential Chemical Cause | Recommended Diagnostic | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Film Insolubility Too Low | Incomplete crosslink reaction | FTIR for residual reactive groups | Increase initiator dose or UV/thermal budget |

| Excessive Dark Current in OPD | Trapped photo-acid/radical | XPS for elemental impurities | Longer post-cure bake or UV flood without crosslinker |

| Poor Vertical Charge Transport | Overly dense horizontal network | GISAXS for nanoscale anisotropy | Reduce crosslinker concentration by 50% |

Diagrams

Title: Morphology Locking Experimental Workflow

Title: Crosslinking for Morphology Stabilization Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function & Rationale | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Crosslinker:1,8-Bis(9,9-dioctyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)pyrene benzocyclobutene (BP-BCB) | Forms a robust, insulating network via thermally-activated [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition. Minimally disrupts adjacent semiconductor ordering. | Requires high processing temp (>200°C). Not suitable for low-Tg semiconductors. |

| Photo-Crosslinker:4,4'-Diazidostilbene-2,2'-disulfonic acid disodium salt | UV-triggered nitrene insertion reacts with C-H bonds. Enables low-temperature morphology locking orthogonal to thermal processes. | Potential for side reactions; requires careful control of UV dose. |

| Sol-Gel Crosslinker:1,6-Bis(trimethoxysilyl)hexane (BTMSH) | Undergoes hydrolysis/condensation to form a siloxane (Si-O-Si) network. Excellent for mechanical stability and high Tg. | Sensitive to ambient moisture during solution storage. Requires acid/base or photo-initiation. |

| Photo-Acid Generator (PAG):Diphenyliodonium hexafluorophosphate | Upon UV exposure, generates strong acid catalyzing condensation reactions (e.g., of siloxanes or epoxies). Enables spatial patterning. | Residual acid can degrade device performance; requires neutralization step. |

| Adhesion Promoter:(3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Forms covalent bonds with oxide substrates and organic films. Improves interfacial adhesion of crosslinked networks. | Must be applied as a thin monolayer; excess leads to poor film quality. |

Diagnosing and Solving Stability Failures: A Tg-Centric Troubleshooting Guide

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During my thin-film deposition, I observe unexpected crystallization or dewetting. How do I determine if this is due to operational error (e.g., spin speed) or thermal stress from the substrate? A: First, systematically isolate variables.

- Operational Check: Repeat the spin-coating process at your standard condition (e.g., 1500 rpm for 60s). Then, perform an identical run varying only one parameter: a) Spin Speed (±300 rpm), b) Acceleration (slower/faster), c) Solvent Batch. If the defect pattern changes, the mode is operational.

- Thermal Check: Measure the substrate temperature before and immediately after deposition with an infrared thermometer. Preheat substrates to your target temperature (e.g., 25°C, 50°C, 80°C) on a hotplate, transfer, and coat within 5 seconds. If morphology stabilizes at a specific pre-heat temperature matching the material's Tg, the failure is thermal stress-induced.

- Protocol - Film Morphology Comparison:

- Materials: AFM or optical microscope with surface analysis software.

- Method: Image three areas per sample (center, edge1, edge2). Calculate the RMS roughness (Rq) and dewetted area percentage.

- Analysis: Compare the data across your variable tests (see Table 1).

Q2: My organic semiconductor device performance degrades rapidly during electrical testing. Is this an ambient-induced failure (O₂/H₂O) or an operational Joule heating effect? A: This requires a controlled environment test.

- Ambient Isolation: Encapsulate one set of devices immediately after fabrication with a UV-curable epoxy in a nitrogen glovebox (<0.1 ppm O₂/H₂O). Keep a parallel set unencapsulated in ambient lab air (40-60% RH).

- Operational (Joule Heating) Test: Perform current-density-voltage (J-V) characterization using a pulsed measurement protocol (pulse width 1ms, duty cycle 0.1%) versus standard DC sweeping. The pulsed method minimizes self-heating.

- Protocol - Stability Measurement:

- Materials: Semiconductor parameter analyzer, environmental probe station, glovebox integration.