Harnessing NLP for Polymer Data Extraction: Transforming Materials Science and Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative potential of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in automating the extraction of polymer data from scientific literature, addressing a critical bottleneck in materials informatics.

Harnessing NLP for Polymer Data Extraction: Transforming Materials Science and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in automating the extraction of polymer data from scientific literature, addressing a critical bottleneck in materials informatics. We examine the foundational challenges of data scarcity in polymer science and present advanced NLP methodologies, including domain-specific language models like MaterialsBERT, which has been used to extract over 300,000 property records from 130,000 abstracts. The content provides a comprehensive analysis of troubleshooting common implementation hurdles, such as data quality and model interpretability, and offers validation frameworks for assessing extraction accuracy. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes technical insights with practical applications, highlighting how NLP-driven data pipelines can accelerate discovery in biomedical and clinical research by unlocking chemistry-structure-property relationships from vast text corpora.

The Polymer Data Challenge: Why NLP is Revolutionizing Materials Discovery

The Growing Data Crisis in Polymer Science

The field of polymer science is experiencing a rapid acceleration in data generation, yet a substantial amount of historical and newly published data remains trapped in unstructured formats within scientific journal articles [1]. This creates a critical bottleneck for modern materials informatics, which relies on the availability of structured, machine-readable datasets to advance discovery [1] [2]. The core of the data crisis lies in the fact that while computational and experimental workflows systematically generate new data, an immense body of knowledge is locked in published literature as unstructured prose, impeding immediate reuse by data-driven methods [2]. One study highlights the magnitude of this problem, noting that a corpus of approximately 2.4 million materials science journal articles yielded 681,000 polymer-related documents containing over 23 million paragraphs, from which automated extraction pipelines successfully identified over one million property records for just 24 targeted properties [1]. This demonstrates both the vast potential and the significant challenge of liberating trapped polymer data.

NLP and LLM-Driven Solutions for Data Liberation

Foundational Technologies

The application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) to polymer science literature seeks to automatically extract materials insights, properties, and synthesis data from text [1]. Foundational to this process is Named Entity Recognition (NER), which identifies key entities such as materials, characterization methods, or properties [1]. Transformer-based architectures like BERT have demonstrated superior performance in this domain, leading to the development of domain-specific models such as MaterialsBERT, which is derived from PubMedBERT and fine-tuned for materials science tasks [1].

More recently, general-purpose LLMs like GPT, LlaMa, and Gemini have shown remarkable robustness in handling various NLP tasks, including high-performance text classification, NER, and extractive question-answering, even with limited datasets [1] [2]. Their key advantage lies in the semi-supervised pre-training on vast scientific corpora, which grants them a foundational comprehension of language semantics and contextual understanding, enabling them to perform in-domain tasks with no (zero-shot) or only a few task-specific examples (few-shots) [1].

Comparative Performance of Extraction Models

Table 1: Comparison of model performance and costs for polymer data extraction.

| Model | Primary Strength | Reported Performance / Accuracy | Key Limitation / Cost Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT [1] | Effective for NER; superior on materials-specific datasets. | Successfully extracted >300,000 records from ~130,000 abstracts. | Struggles with complex entity relationships across long text spans. |

| GPT-3.5 & GPT-4.1 [1] [2] | High extraction accuracy and versatility. | F1 ~0.91 for thermoelectric properties; used to extract >1 million polymer records [2]. | High computational cost and API fees [1]. |

| GPT-4.1 Mini [2] | Balanced performance and cost. | Nearly comparable to larger GPT models. | Slightly reduced accuracy. |

| Llama-2-7B-Chat [1] [3] | Open-source; enables fine-tuning for specific tasks. | Achieved 91.1% accuracy for injection molding parameters with fine-tuning [3]. | Requires fine-tuning for optimal performance; computational overhead for training. |

Application Notes & Protocols: An LLM-Driven Extraction Pipeline

This protocol details an automated pipeline for extracting polymer property data from scientific literature, leveraging a hybrid approach of heuristic filtering, NER, and LLMs to optimize for both accuracy and computational cost [1].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Corpus Assembly: Begin by assembling a corpus of full-text journal articles from authorized publisher portals (e.g., Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, American Chemical Society, Royal Society of Chemistry) using Crossref indexing and APIs for bulk downloading [1] [2].

- Polymer Document Identification: Identify polymer-related documents within the corpus by searching for key terms (e.g., "poly") in article titles and abstracts. This filtering can reduce a multi-million article corpus to a focused subset of several hundred thousand documents for processing [1].

- Text Unit Segmentation: Treat individual paragraphs as the fundamental text units for processing. This granular approach helps isolate discrete pieces of information [1].

- Text Cleaning (Optional but Recommended): For more complex workflows, preprocess the full text by removing non-relevant sections such as "Conclusion" and "References" which typically do not contain property information. Use rule-based scripts with regular expressions to retain only sentences likely to contain target properties, thereby increasing token efficiency for subsequent LLM processing [2].

Two-Stage Paragraph Filtering

To avoid unnecessary and costly LLM prompts, a two-stage filtering mechanism is employed to identify paragraphs with a high probability of containing extractable data [1].

- Stage 1: Heuristic Filter: Pass each paragraph through property-specific heuristic filters. These filters use manually curated lists of target polymer properties and their co-referents (e.g., "Tg" for "glass transition temperature") to detect relevant paragraphs. Only a fraction of paragraphs (e.g., ~11%) are expected to pass this initial filter [1].

- Stage 2: NER Filter: Apply a NER model (e.g., MaterialsBERT) to the remaining paragraphs to confirm the presence of all necessary named entities:

material name,property name,numerical value, andunit. The absence of any of these entities indicates an incomplete record. This stage further refines the dataset to the most promising paragraphs (e.g., ~3% of the original total) [1].

Information Extraction with LLMs

- Model Selection: Choose an LLM based on the trade-off between required accuracy and available budget (refer to Table 1). For high-throughput, cost-sensitive applications, GPT-4.1 Mini or a finely-tuned open-source model like Llama 2 may be optimal [2].

- Prompt Engineering: Design precise prompts for the LLM to perform structured data extraction. Use few-shot learning by providing clear examples of input text and the desired structured output (e.g., in JSON format) within the prompt to guide the model [1]. The prompt should instruct the model to identify the polymer material, the property, its numerical value, and its units.

- Structured Output Parsing: Execute the LLM calls on the filtered paragraphs. The output should be a structured data record (e.g., a JSON object). Implement automated scripts to parse these outputs and aggregate them into a master database [3] [2].

- Multi-Agent Workflows (Advanced): For complex extractions involving multiple data types (e.g., thermoelectric and structural properties), consider an agentic workflow using a framework like LangGraph. This involves specialized agents (e.g., Material Candidate Finder, Property Extractor) working in concert, with dynamic routing and conditional branching for robust, high-quality data extraction [2].

Data Validation and Publication

- Benchmarking: Manually curate a gold-standard test set from a subset of papers. Use this to benchmark the performance (precision, recall, F1-score) of your chosen extraction pipeline [2].

- Data Normalization: Normalize extracted units and material names to a standard nomenclature to ensure consistency across the dataset (e.g., converting "°C" to "C", "MPa" to "GPa") [2].

- Public Dissemination: Make the extracted data publicly available via an interactive web platform or data repository to support broader scientific community efforts [1] [2].

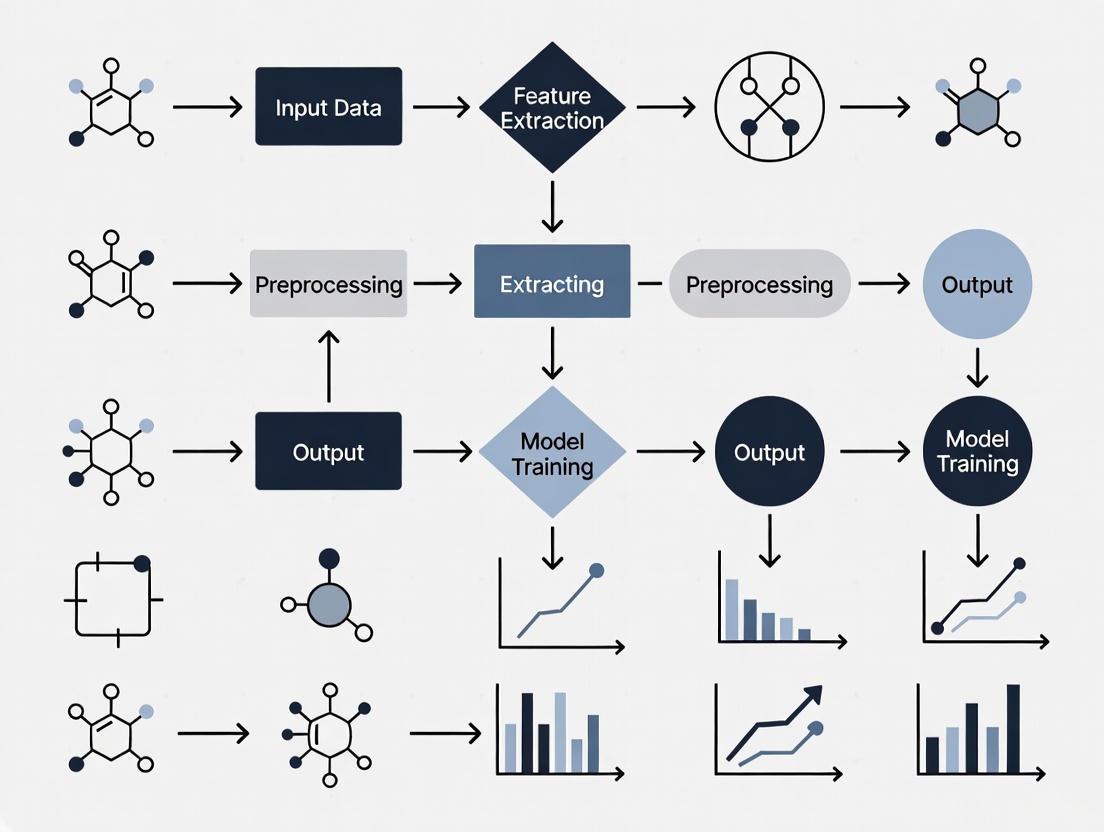

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from data acquisition to publication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and models for polymer data extraction.

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT Model [1] | A domain-specific NER model fine-tuned on materials science text. | Accurately identifies and tags key entities (materials, properties, values) in text during the NER filtering stage. |

| GPT / LlaMa LLMs [1] [3] | General-purpose large language models capable of understanding and generating text. | The core engine for relationship extraction and structuring of data from filtered paragraphs based on prompts. |

| QLoRA Fine-Tuning [3] | An efficient fine-tuning method that reduces computational overhead. | Adapts open-source LLMs (e.g., LlaMa-2) for highly specific tasks like extracting injection molding parameters with minimal data. |

| LangGraph Framework [2] | A library for building stateful, multi-actor applications with LLMs. | Orchestrates complex, multi-agent extraction workflows where different specialized LLM agents handle sub-tasks. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker [4] | An online tool to verify color contrast ratios against WCAG guidelines. | Ensures that any data visualizations or diagrams created from the extracted data meet accessibility standards. |

| Regular Expression Patterns [1] [2] | Sequences of characters defining a search pattern. | Forms the basis of heuristic filters to initially sift through millions of paragraphs for property-related content. |

| Saussureamine C | Saussureamine C, MF:C19H26N2O5, MW:362.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SC75741 | SC75741, MF:C29H23N7O2S2, MW:565.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The growing data crisis in polymer science, characterized by vast quantities of information remaining locked in unstructured literature, is now being addressed through sophisticated NLP and LLM-driven pipelines. The protocols outlined here provide a roadmap for researchers to systematically liberate this data, transforming it into a structured, accessible format that fuels materials informatics and accelerates the discovery of next-generation polymers.

The overwhelming majority of materials knowledge is published as scientific literature, creating a significant obstacle to large-scale analysis due to its unstructured and highly heterogeneous format [5]. Natural Language Processing (NLP), a domain of artificial intelligence, provides the methodological foundation for transforming this textual data into structured, actionable knowledge by enabling machines to understand, interpret, and generate human language [6] [7]. For materials researchers, NLP technologies offer powerful capabilities to automatically construct large-scale materials datasets from published literature, thereby accelerating materials discovery and data-driven research [8].

The application of NLP to materials science represents a paradigm shift in how researchers extract and utilize information. Where traditional manual literature review is time-consuming and limits the efficiency of large-scale data accumulation, automated information extraction pipelines can process hundreds of thousands of documents in days rather than years [8] [9]. This primer examines the core NLP technologies, presents detailed application protocols for polymer data extraction, and provides practical implementation frameworks tailored specifically for materials researchers.

Core NLP Concepts and Technologies

Fundamental NLP Components

NLP encompasses a range of technical components that work together to transform unstructured text into structured data. For materials science applications, several core concepts are particularly relevant:

- Tokenization: The process of separating strings of text into individual words or phrases (tokens) for further processing [6]

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identification and classification of key entities in text, such as material names, properties, values, and synthesis parameters [6] [7]

- Part-of-Speech Tagging: Assignment of grammatical categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives) to tokens to understand syntactic structure [7]

- Relationship Extraction: Classification of relationships between extracted entities, such as associating a property value with a specific material [8]

- Sentiment Analysis: Determination of emotional tone or attitude in text, though in materials science this often adapts to classify statements about material performance or characteristics [6]

Evolution of NLP Approaches

NLP methodologies have evolved through distinct phases, from early rule-based systems to contemporary deep learning approaches:

Rule-based systems initially relied on predefined linguistic rules and patterns to process and analyze text, using handcrafted rules to interpret text features [7]. These systems were limited to narrow domains and required significant expert input.

Statistical methods employed mathematical models to analyze and predict text based on word frequency and distribution, using techniques like Hidden Markov Models for sequence prediction tasks [7].

Machine learning approaches applied algorithms that learn from labeled data to make predictions or classify text based on features, enabling more adaptable systems [7].

Deep learning and transformer architectures now represent the state-of-the-art, with models that automatically learn features from data and capture complex contextual relationships [8] [7]. The transformer architecture, characterized by the attention mechanism, has become the fundamental building block for large language models (LLMs) that demonstrate remarkable capabilities in materials information extraction [8].

NLP Applications in Materials Research

Polymer Data Extraction Applications

NLP techniques have demonstrated particular utility in polymer informatics, where they address critical data scarcity challenges:

Table 1: Representative Polymer Data Extraction Applications

| Application Focus | Scale | Key Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| General polymer property extraction from abstracts | ~130,000 abstracts | ~300,000 material property records extracted in 60 hours | [9] |

| Full-text polymer property extraction | ~681,000 articles | Over 1 million records for 24 properties across 106,000 unique polymers | [1] |

| Polymer nanocomposite synthesis parameter retrieval | Not specified | Successful extraction of synthesis conditions and parameters | [10] |

| Structured knowledge extraction from PNC literature | Not specified | Framed as NER and relationship extraction task with seq2seq models | [10] |

Materials Discovery and Design

Beyond simple data extraction, NLP enables more sophisticated materials discovery applications. Word embeddings—dense, low-dimensional vector representations of words—allow materials science knowledge to be encoded in ways that capture semantic relationships [8]. These representations enable materials similarity calculations that can assist in new materials discovery by identifying analogies and patterns not immediately apparent through manual literature review [8].

Language models fine-tuned on materials science corpora have been employed for property prediction tasks, including glass transition temperature prediction for polymers [9]. More recently, the emergence of prompt-based approaches with large language models (LLMs) offers a novel pathway to materials information extraction that complements traditional NLP pipelines [8].

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Data Extraction

Protocol 1: NER-Based Pipeline for Polymer Property Extraction

This protocol outlines the methodology for extracting polymer property data using a specialized Named Entity Recognition model, MaterialsBERT, applied to scientific abstracts [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for NER-Based Extraction Pipeline

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Text Corpus | Source materials literature | 2.4 million materials science abstracts [9] |

| Domain-Specific Language Model | Encodes materials science terminology | MaterialsBERT (trained on 2.4 million abstracts) [9] |

| Annotation Framework | Creates labeled data for model training | Prodigy annotation tool with 750 annotated abstracts [9] |

| Named Entity Recognition Model | Identifies and classifies material entities | BERT-based encoder with linear classification layer [9] |

| Entity Ontology | Defines target entity types | 8 entity types: POLYMER, PROPERTYNAME, PROPERTYVALUE, etc. [9] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Corpus Collection and Preprocessing

- Assemble a corpus of materials science abstracts (2.4 million abstracts in the reference implementation)

- Filter for polymer-relevant content using keyword searches (e.g., "poly")

- Further filter abstracts containing numeric information likely to represent property values [9]

Annotation and Ontology Development

- Define an entity ontology specific to materials science, including: POLYMER, POLYMERCLASS, PROPERTYNAME, PROPERTYVALUE, MONOMER, ORGANICMATERIAL, INORGANICMATERIAL, MATERIALAMOUNT

- Manually annotate 750 abstracts using the Prodigy annotation tool

- Split annotated data into training (85%), validation (5%), and test sets (10%) [9]

Model Training and Optimization

- Initialize with MaterialsBERT encoder (pre-trained on materials science abstracts)

- Add a linear classification layer with softmax activation for entity type prediction

- Use cross-entropy loss with dropout regularization (probability = 0.2)

- Train with sequence length limit of 512 tokens, truncating longer sequences [9]

Inference and Data Extraction

- Apply trained NER model to polymer-relevant abstracts

- Implement heuristic rules to combine entity predictions into structured property records

- Export extracted data in structured format (e.g., JSON, database) [9]

Validation and Quality Assessment

- Evaluate model performance on held-out test set

- Measure inter-annotator agreement for training data (reported Fleiss Kappa = 0.885)

- Manually verify sample extractions for accuracy [9]

Protocol 2: LLM-Based Pipeline for Full-Text Extraction

This protocol describes a framework for extracting polymer-property data from full-text journal articles using large language models, capable of processing millions of paragraphs with high precision [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for LLM-Based Extraction Pipeline

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Text Corpus | Comprehensive source data | 2.4 million journal articles from 11 publishers [1] |

| LLM for Information Extraction | Primary extraction engine | GPT-3.5 or LlaMa 2 [1] |

| Heuristic Filter | Initial relevance filtering | Property-specific keyword matching [1] |

| NER Filter | Verification of extractable records | MaterialsBERT-based entity detection [1] |

| Cost Optimization Framework | Manages computational expense | Two-stage filtering to reduce LLM calls [1] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Corpus Assembly and Preparation

- Collect full-text articles from multiple publishers (Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, etc.)

- Identify polymer-relevant documents through keyword search in titles and abstracts ("poly")

- Process documents at paragraph level (23.3 million paragraphs from 681,000 articles) [1]

Two-Stage Filtering System

- Apply property-specific heuristic filters to identify paragraphs mentioning target properties

- Utilize NER filter to verify presence of required entities (material, property, value, unit)

- This two-stage process reduced processing volume from 23.3M to 716,000 paragraphs (~3%) [1]

LLM Configuration and Prompt Engineering

- Select appropriate LLM (GPT-3.5 or LlaMa 2 in the reference implementation)

- Implement few-shot learning with task-specific examples

- Design prompts to extract structured property records from filtered paragraphs [1]

Structured Data Extraction and Validation

- Process filtered paragraphs through LLM to extract property records in structured format

- Implement consistency checks across extractions

- Resolve conflicting or ambiguous extractions through consensus mechanisms [1]

Performance and Cost Optimization

- Monitor extraction quality across different property types

- Optimize prompt strategies to maximize information yield per LLM call

- Balance computational cost against data quality requirements [1]

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Assessment of Extraction Approaches

Table 4: Performance Comparison of NLP Extraction Methods

| Metric | NER-Based Pipeline (Abstracts) | LLM-Based Pipeline (Full-Text) |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Scale | ~130,000 abstracts | ~681,000 full-text articles |

| Extraction Output | ~300,000 property records | >1 million property records |

| Properties Covered | Multiple property types | 24 specific properties |

| Processing Time | 60 hours | Not specified |

| Key Innovation | MaterialsBERT domain adaptation | Two-stage filtering with LLM extraction |

| Primary Advantage | Computational efficiency | Comprehensive full-text coverage |

| Limitations | Restricted to abstracts | Higher computational cost |

The comparative analysis reveals complementary strengths between traditional NER-based approaches and emerging LLM-based methods. NER pipelines offer computational efficiency and domain specificity, while LLM approaches provide broader coverage and greater flexibility [1] [9]. The two-stage filtering system implemented in the LLM pipeline proved particularly effective, reducing the number of paragraphs requiring expensive LLM processing from 23.3 million to approximately 716,000 (3% of the original corpus) while maintaining comprehensive coverage of extractable data [1].

Implementation Toolkit for Materials Researchers

NLP Tools and Frameworks

Table 5: NLP Tools for Materials Science Applications

| Tool | Type | Materials Science Applications |

|---|---|---|

| spaCy | Open-source library | Fast NLP pipelines for entity recognition and dependency parsing [11] |

| Hugging Face Transformers | Model repository | Access to pretrained models (BERT, GPT) for materials text [11] |

| MaterialsBERT | Domain-specific model | NER for materials science texts [9] |

| ChemDataExtractor | Domain-specific toolkit | Extraction of chemical information from scientific literature [9] |

| Stanford CoreNLP | Java-based toolkit | Linguistic analysis of materials science texts [11] |

| Sch 13835 | Sch 13835, CAS:150519-34-9, MF:C15H10ClNO4S, MW:335.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sch 29482 | Sch 29482, CAS:77646-83-4, MF:C10H13NO4S2, MW:275.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of NLP pipelines for materials research requires attention to several practical considerations:

Data Quality and Preprocessing: The quality of extracted data heavily depends on proper text preprocessing, including cleaning, tokenization, and normalization. Materials science texts present particular challenges with specialized terminology, non-standard nomenclature, and ambiguous abbreviations [1].

Domain Adaptation: General-purpose NLP models typically underperform on materials science texts due to domain-specific terminology. Effective implementation requires domain adaptation through continued pretraining on scientific corpora (as with MaterialsBERT) or fine-tuning on annotated materials science datasets [8] [9].

Computational Resource Management: LLM-based approaches offer powerful extraction capabilities but require significant computational resources. Implementation strategies should include filtering mechanisms to reduce unnecessary LLM calls and cost-benefit analysis of extraction precision requirements [1].

Integration with Materials Informatics Workflows: Extracted data should be formatted for seamless integration with downstream materials informatics applications, including property prediction models, materials discovery frameworks, and data visualization platforms [8] [9].

Future Directions and Challenges

The application of NLP in materials science continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges shaping future development:

Multimodal AI Systems: Next-generation systems are incorporating multimodal capabilities that process not only text but also figures, tables, and molecular structures from scientific literature [6].

Domain-Specialized LLMs: There is growing development of materials-specialized LLMs trained specifically for polymer science, metallurgy, ceramics, and other subdomains to improve accuracy and relevance compared to general-purpose models [6].

Autonomous Research Systems: NLP technologies are increasingly integrated into autonomous research systems that combine literature analysis with experimental planning and execution [8].

Persistent Challenges: Significant challenges remain in handling the complexity of materials science nomenclature, ensuring extraction accuracy, mitigating LLM "hallucinations," and managing computational costs [1] [6]. Additionally, the extraction of synthesis parameters and processing-structure-property relationships presents more complex challenges than simple property extraction [8].

As NLP technologies continue to mature, their integration into materials research workflows promises to accelerate discovery cycles, enhance data-driven materials design, and ultimately transform how researchers extract knowledge from the vast and growing materials science literature.

Key Polymer Data Types Locked in Unstructured Text

The field of polymer science is experiencing rapid growth, with the number of published materials science papers increasing at a compounded annual rate of 6% [9]. This ever-expanding volume of literature contains a wealth of quantitative and qualitative material property information locked away in natural language that is not machine-readable [9]. This data scarcity in materials informatics impedes the training of property predictors, which traditionally requires painstaking manual curation of data from literature [9]. The emerging field of polymer informatics addresses this challenge by leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to enable data-driven research, moving beyond traditional intuition- and trial-and-error-based methods [12]. Natural language processing (NLP) presents a transformative opportunity to automatically extract this locked information, infer complex chemistry-structure-property relationships, and accelerate the discovery of novel polymers with tailored characteristics for specific applications.

Key Polymer Data Types and Extraction Ontology

To systematically extract information from polymer literature, a defined ontology is required. The following table summarizes key entity types used in a general-purpose polymer data extraction pipeline, which can capture the essential chemistry-structure-property relationships from scientific text [9].

Table 1: Key Polymer Data Types for NLP Extraction

| Entity Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| POLYMER | Specific named polymer entities | "polyethylene", "polymethacrylamide" |

| POLYMER_CLASS | Categories or families of polymers | "polyimide", "polynorbornene" |

| PROPERTY_NAME | Name of a measured or discussed property | "glass transition temperature", "ionic conductivity" |

| PROPERTY_VALUE | Numerical value and units associated with a property | "8.3 J ccâ»Â¹", "180 °C" |

| MONOMER | Building block or repeating unit of a polymer | "methacrylamide" |

| ORGANIC_MATERIAL | Other named organic substances in the system | "CTCA" (RAFT agent) |

| INORGANIC_MATERIAL | Named inorganic substances in the system | "lithium salt" |

| MATERIAL_AMOUNT | Quantity of a material used in a formulation | "5 wt%" |

This ontology forms the foundation for named entity recognition (NER) models, enabling the identification and categorization of critical information snippets from unstructured text [9]. The inter-annotator agreement for this ontology, with a Fleiss Kappa of 0.885, indicates good homogeneity and reliability for training machine learning models [9].

Experimental Protocol: Building a Polymer NLP Pipeline

This protocol details the steps for creating a natural language processing pipeline to extract structured polymer property data from scientific literature abstracts, based on the methodology established by Shetty et al. [9].

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer NLP

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Corpus of Text | Raw textual data for model training and processing. | 2.4 million materials science abstracts [9]. |

| Annotation Tool | Software for manual labeling of entity types in text. | Prodigy (https://prodi.gy) [9]. |

| Pre-trained Language Model | Base model for transfer learning and contextual embeddings. | PubMedBERT, SciBERT, or general BERT [9]. |

| Polymer-specific Language Model | Domain-adapted model for superior performance. | MaterialsBERT (trained on 2.4M materials science abstracts) [9]. |

| Computational Framework | Library for implementing neural network models. | PyTorch or TensorFlow. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Corpus Collection and Pre-processing: Begin with a large corpus of materials science abstracts. Filter for polymer-relevant content using keyword searches (e.g., "poly") and regular expressions to identify abstracts containing numerical data likely to represent property values [9].

- Annotation and Training Set Creation: Manually annotate a subset of abstracts (e.g., 750) using the defined ontology (Table 1). This process is ideally performed by multiple domain experts to ensure consistency. Split the annotated data into training (85%), validation (5%), and test (10%) sets [9].

- Model Architecture and Training:

- Encoder: Use a BERT-based model (e.g., MaterialsBERT) to convert input text tokens into context-aware vector embeddings [9].

- Classifier: Feed the generated token representations into a linear layer connected to a softmax non-linearity. This layer predicts the probability of each entity type for every input token [9].

- Training: Train the model using a cross-entropy loss function to learn the correct entity type labels. Use dropout (e.g., probability of 0.2) in the linear layer to prevent overfitting [9].

- Inference and Data Record Creation: Apply the trained NER model to the entire corpus of polymer abstracts. Use heuristic rules to combine the model's predictions (e.g., linking a PROPERTYVALUE to its corresponding PROPERTYNAME and POLYMER) to form complete material property records [9].

- Validation and Analysis: Manually review a sample of the extracted data to validate accuracy. The extracted dataset can then be used for analysis, trend identification, or as training data for property prediction models [9].

Figure 1: Polymer Data Extraction NLP Pipeline

Application Examples and Extracted Data Insights

The following table presents quantitative data extracted using the described NLP pipeline, showcasing its ability to recover non-trivial insights across diverse polymer applications [12] [9].

Table 3: Experimentally Derived Polymer Property Data from NLP Extraction

| Polymer/System | Application | Key Property Extracted | Property Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PONB-2Me5Cl (Polymer) | Energy Storage Dielectrics | Energy Density @ 200°C | 8.3 J ccâ»Â¹ | [12] |

| Polymer Electrolyte Formulations | Li-Ion Batteries | Ionic Conductivity | High-conductivity candidates identified from 20k screenings | [12] |

| Doped Conjugated Polymers | Electronics | Electrical Conductivity | ~25 to 100 S/cm (Classification) | [12] |

| Polymer Membranes | Fluid Separation | Mixture Separation Precision | High precision forecast for crude oils | [12] |

| Polyesters & Polycarbonates | Biodegradable Polymers | Biodegradability Prediction Accuracy | >82% | [12] |

Advanced Model Architecture: From NER to Relation Extraction

The core of the extraction pipeline is a sophisticated neural model that builds upon the transformer architecture. The following diagram details the components involved in processing text to identify and classify polymer data entities.

Figure 2: NER Model Architecture for Polymer Data

Future Outlook and Emerging Techniques

The field of polymer informatics is rapidly evolving beyond basic NER. New deep learning frameworks are being developed to better capture the unique complexities of polymer chemistry. For instance, the PerioGT framework introduces a periodicity-aware deep learning approach that constructs a chemical knowledge-driven periodicity prior during pre-training and incorporates it into the model through contrastive learning [13]. This addresses a key limitation of existing methods that often simplify polymers into single repeating units, thereby neglecting their inherent periodicity and limiting model generalizability [13]. PerioGT has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on 16 downstream tasks and successfully identified two polymers with potent antimicrobial properties in wet-lab experiments, highlighting the real-world potential of these advanced NLP and AI methods [13]. The integration of such sophisticated models will further enhance the accuracy and scope of data extraction, pushing the boundaries of data-driven polymer discovery.

The Shift from Manual Curation to Automated Extraction

The field of polymer science is experiencing rapid growth, with published literature expanding at a compounded annual rate of 6% [9]. This ever-increasing volume of scientific publications has made the traditional method of manual data curation a significant bottleneck. Manually inferring chemistry-structure-property relationships from literature is not only time-consuming but also prone to inconsistencies, creating a data scarcity that stifles machine learning (ML) applications and delays the discovery of next-generation energy materials [14] [9]. The shift from manual curation to automated extraction using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) is therefore critical to unlocking the vast amount of structured data trapped in unstructured text, thereby accelerating materials discovery and innovation.

Quantitative Comparison: Manual vs. Automated Extraction

The advantages of automated data extraction systems over manual methods are substantial and measurable. The table below summarizes a direct comparison in the context of clinical data, which mirrors the efficiencies found in scientific data extraction, demonstrating dramatic improvements in processing time and resource utilization [15].

| Parameter | Manual Review | LLM-Based Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Time | 7 months (5 physicians) | 12 days (2 physicians) |

| Physician Hours | 1025 hours | 96 hours |

| Resource Reduction | Baseline | 91% reduction in hours |

| Accuracy | Baseline for comparison | 90.8% |

| Cost per Case | Labor-intensive | ~US $0.15 (API cost) |

| Key Advantage | Human judgment | Efficiency, scalability, consistency |

In polymer science, the scale of automation is even more profound. One study processed ~130,000 abstracts in just 60 hours, obtaining approximately 300,000 material property records [9]. A more extensive effort on full-text articles utilized a corpus of 2.4 million materials science journal articles, identifying 681,000 polymer-related documents and extracting over one million property records for over 106,000 unique polymers [1]. This demonstrates the unparalleled scalability of automated pipelines.

Experimental Protocols for Automated Extraction

Implementing an effective automated data extraction pipeline requires a structured methodology. The following protocols detail two proven approaches.

Protocol A: LLM-Based Processing Pipeline

This protocol leverages the powerful reasoning capabilities of large language models like GPT-3.5 or Claude 3.5 Sonnet for direct data extraction and structuring [1] [15].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Document Retrieval & Pre-processing: Assemble a corpus of full-text journal articles or abstracts. Identify polymer-relevant documents by searching for domain-specific terms (e.g., "poly") in titles and abstracts [1].

- Two-Stage Text Filtering: To optimize costs and efficiency, a dual-stage filter is applied to the text paragraphs:

- Heuristic Filter: Pass each paragraph through property-specific filters using manually curated keywords and co-referents to identify texts relevant to target properties (e.g., "glass transition", "Young's modulus"). This typically reduces the text volume to ~11% of the original [1].

- NER Filter: Apply a Named Entity Recognition (NER) model, such as MaterialsBERT, to the remaining paragraphs to confirm the presence of all necessary entities (e.g.,

POLYMER,PROPERTY_NAME,PROPERTY_VALUE,UNIT). This further refines the dataset to ~3% of the original paragraphs, ensuring they contain complete, extractable records [1].

- LLM Prompting & Data Structuring: Feed the filtered paragraphs into an LLM using a carefully designed prompt. The prompt should be developed iteratively over multiple phases (e.g., initial framework, rule refinement, edge-case handling) with sample data to instruct the model on how to extract and structure the required factors into a predefined format like CSV [15] [1].

- Data Validation & Integration: A stratified random sample of the LLM outputs should be validated by domain experts to assess accuracy. The final structured data is then integrated into a searchable database or used for downstream ML tasks [15] [9].

Protocol B: Specialized NER Model Pipeline

This protocol involves training or utilizing a domain-specific BERT model, which is highly effective for large-scale, general-purpose property extraction [9].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Corpus Creation: Gather a large collection of materials science abstracts or full-text articles (e.g., 2.4 million papers) [9] [1].

- Ontology Definition & Annotation: Define an ontology of entity types relevant to polymer science (e.g.,

POLYMER,PROPERTY_NAME,PROPERTY_VALUE,MONOMER). Domain experts then annotate a subset of documents (e.g., 750 abstracts) using this ontology to create a labeled training dataset [9]. - Model Training: Train a NER model using a BERT-based architecture. A model like MaterialsBERT, which is pre-trained on millions of materials science abstracts, is fine-tuned on the annotated dataset. This model learns to tag tokens in the text with the correct entity labels from the ontology [9].

- Inference & Relation Extraction: Apply the trained NER model to the entire unlabeled corpus. Use heuristic rules and dependency parsing to combine the predicted entities and establish relationships between them, forming complete material-property-value records [9].

- Data Output & Analysis: The extracted data is made available in a structured format and can be analyzed for specific applications, such as identifying trends in polymer solar cells or fuel cells, or for training property prediction models [9].

The following table catalogues the key computational tools and data sources that form the foundation of modern, automated polymer data extraction workflows.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Function in Automated Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT [1] [9] | Domain-Specific Language Model | A BERT model pre-trained on materials science text; excels at Named Entity Recognition (NER) for identifying materials and properties. |

| GPT-3.5 / LlaMa 2 [1] | General-Purpose LLM | Used for direct information extraction and structuring from text via API calls, leveraging few-shot learning. |

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet [15] | General-Purpose LLM | An alternative LLM used for curating and structuring data from pre-extracted, deidentified clinical data sheets. |

| Polymer Scholar [1] [9] | Public Data Repository | A web-based interface hosting millions of automatically extracted polymer-property records for the research community. |

| Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW) [15] | Structured Data Source | An integrated data platform that provides pre-extracted, deidentified clinical data for subsequent LLM processing. |

The shift from manual curation to automated extraction is no longer a future prospect but an ongoing transformation in polymer and materials research. Methodologies leveraging both specialized NER models like MaterialsBERT and powerful general-purpose LLMs have proven their ability to process millions of documents with remarkable efficiency and accuracy. This paradigm shift addresses the critical data scarcity problem, enabling the creation of large-scale, structured datasets. These datasets are indispensable for training robust machine learning models, uncovering non-trivial insights from existing literature, and ultimately accelerating the design and discovery of novel polymer materials for energy and other advanced technologies.

The exponential growth of published materials science literature presents a significant bottleneck for research, with the number of papers increasing at a compounded annual rate of 6% [9]. Within this domain, polymer science faces unique informatics challenges due to non-standard nomenclature, complex material representations, and the unstructured nature of data trapped in scientific texts [9] [1]. Natural language processing (NLP) offers promising solutions to automatically extract structured polymer-property data from published literature, enabling large-scale data analysis and accelerating materials discovery [9] [1] [8]. This application note examines the specific challenges in polymer data extraction and details experimental protocols for overcoming them, framed within the broader context of NLP for polymer informatics.

Domain-Specific Challenges in Polymer Data Extraction

Polymer Name Variations and Normalization

Polymer nomenclature presents unique challenges distinct from small molecules or inorganic materials. Polymers exhibit non-trivial variations in naming conventions, including commonly used names, acronyms, synonyms, and historical terms [9] [1]. For instance, the polymer poly(methyl methacrylate) might be referred to as PMMA, acrylic glass, or perspex across different publications. This variability necessitates robust normalization techniques to identify all name variations referring to the same polymer entity.

Unlike small organic molecules, polymer names cannot typically be converted to standardized representations like SMILES strings without additional structural inference from figures or supplementary information [9]. This limitation complicates the training of property-predictor machine learning models that require structured input representations.

Property Normalization and Relationship Extraction

Material property information in scientific literature exhibits substantial variability in expression, units, and measurement contexts. Different authors may report the same property using different terminology, units, or numerical formats. For example, glass transition temperature might be referred to as "Tg," "glass transition temperature," or "glass transition point" across different abstracts [9].

Establishing accurate relationships between extracted entities (polymers, properties, values, and conditions) presents additional challenges, particularly when information spans multiple sentences or includes comparative statements [1]. Traditional named entity recognition (NER) systems can identify individual entities but struggle with connecting these entities into meaningful property records without additional relationship extraction capabilities.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Performance comparison of NLP approaches for polymer data extraction

| Method | Data Source | Records Extracted | Processing Time | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT (NER) | 130,000 abstracts | ~300,000 [9] | 60 hours [9] | Cost-effective; materials-specific training |

| LLM-based (GPT-3.5) | 681,000 full-text articles | >1,000,000 [1] | Not specified | Superior relationship extraction; handles complex contexts |

| Manual Curation (PoLyInfo) | Various sources | ~492,000 [16] | Many years [16] | High precision; expert validation |

Table 2: Property prediction performance using extracted polymer data

| Property | Best Model | R² Value | Impact of Textual Modality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Uni-Poly | ~0.90 [17] | Minimal improvement |

| Thermal Decomposition Temperature (Td) | Uni-Poly | 0.70-0.80 [17] | ~1.6-3.9% R² improvement [17] |

| Density (De) | Uni-Poly | 0.70-0.80 [17] | ~1.6-3.9% R² improvement [17] |

| Electrical Resistivity (Er) | Uni-Poly | 0.40-0.60 [17] | ~1.6-3.9% R² improvement [17] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Uni-Poly | 0.40-0.60 [17] | ~1.6-3.9% R² improvement [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Named Entity Recognition with MaterialsBERT

Objective: To extract polymer-related entities from scientific abstracts using a domain-specific language model.

Materials and Methods:

- Corpus: 2.4 million materials science abstracts [9]

- Annotation Tool: Prodigy

- Annotation Guidelines: 8 entity types (POLYMER, POLYMERCLASS, PROPERTYVALUE, PROPERTYNAME, MONOMER, ORGANICMATERIAL, INORGANICMATERIAL, MATERIALAMOUNT) [9]

- Training Data: 750 manually annotated abstracts (85% training, 5% validation, 10% testing) [9]

- Model Architecture: BERT-based encoder with linear layer and softmax non-linearity [9]

- Training Parameters: Cross-entropy loss, dropout probability of 0.2, sequence length limit of 512 tokens [9]

Procedure:

- Filter polymer-relevant abstracts using keyword "poly" and regular expressions for numeric information [9]

- Pre-annotate abstracts using entity dictionaries to accelerate manual annotation [9]

- Conduct three rounds of annotation with guideline refinement between rounds [9]

- Train MaterialsBERT model using transfer learning from PubMedBERT [9]

- Evaluate model performance using standard NER metrics on test set [9]

LLM-Based Data Extraction from Full-Text Articles

Objective: To extract polymer-property records from full-text journal articles using large language models.

Materials and Methods:

- Corpus: 2.4 million materials science journal articles from 11 publishers [1]

- LLM Models: GPT-3.5 and LlaMa 2 [1]

- Target Properties: 24 polymer properties including thermal, optical, mechanical, and transport properties [1]

- Filtering System: Two-stage approach (heuristic filter + NER filter) [1]

Procedure:

- Identify polymer-related documents (681,000) by searching for "poly" in titles and abstracts [1]

- Divide articles into paragraphs (23.3 million total) [1]

- Apply property-specific heuristic filters to identify relevant paragraphs (~2.6 million) [1]

- Apply NER filter to confirm presence of complete extractable records (~716,000 paragraphs) [1]

- Process filtered paragraphs through LLMs with appropriate prompting strategies [1]

- Validate extracted records and format into structured database [1]

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Polymer data extraction workflow from full-text articles

Diagram 2: Named entity recognition model architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential resources for polymer data extraction research

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT | Language Model | Domain-specific NER for materials science [9] | Publicly available |

| Polymer Scholar | Data Platform | Explore extracted polymer property data [9] [1] | polymerscholar.org |

| Poly-Caption | Dataset | Textual descriptions of polymers for multi-modal learning [17] | Generated via knowledge-enhanced prompting |

| PoLyInfo | Database | Manually curated polymer data for validation [16] | Public database |

| Uni-Poly | Framework | Multi-modal polymer representation learning [17] | Research implementation |

| Schisanhenol | Schisanhenol, CAS:69363-14-0, MF:C23H30O6, MW:402.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Schisantherin B | Schisantherin B, CAS:58546-55-7, MF:C28H34O9, MW:514.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The challenges of polymer name variations and property normalization represent significant but addressable bottlenecks in polymer informatics. The integration of domain-specific NER models like MaterialsBERT with the emergent capabilities of large language models creates a powerful paradigm for unlocking the vast knowledge repository contained in polymer literature [9] [1]. The experimental protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these approaches, while the quantitative performance analyses offer realistic expectations for extraction outcomes. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate polymer discovery and design by creating large-scale, structured datasets amenable to machine learning and data-driven materials development.

Building NLP Pipelines for Polymer Informatics: From BERT to Applications

Architecture of a General-Purpose Polymer Data Extraction Pipeline

The exponential growth of polymer science literature presents a significant challenge for researchers seeking to extract structured property data from vast quantities of unstructured text. Natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs) have emerged as transformative technologies to address this challenge, enabling the automated construction of large-scale materials databases [8]. This application note details the architecture of a general-purpose pipeline for extracting polymer-property data from scientific literature, framing the methodology within broader research on NLP for polymer informatics. The described pipeline processes a corpus of 2.4 million materials science articles to identify polymer-related content and extract structured property records [1], providing researchers with a scalable solution for materials data acquisition.

The polymer data extraction pipeline employs a modular architecture that combines rule-based filtering with advanced machine learning models to identify, process, and structure polymer-property information from full-text journal articles. The overall workflow, illustrated in Figure 1, processes individual paragraphs as text units to maximize contextual understanding and relationship detection between material entities and their properties [1].

Figure 1. General Architecture of Polymer Data Extraction Pipeline. The pipeline processes millions of journal articles through sequential filtering stages to identify polymer-property relationships and output structured data [1].

Pipeline Components and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Polymer Filtering

The initial stage involves assembling a comprehensive corpus of materials science literature and filtering for polymer-relevant content. The corpus construction utilizes authorized downloads from 11 major publishers, including Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, American Chemical Society, and the Royal Society of Chemistry [1].

Table 1: Data Acquisition and Initial Filtering Statistics

| Processing Stage | Scale | Filtering Method | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Corpus | 2.4 million articles | Crossref indexing | Full document collection |

| Polymer Filtering | 681,000 articles | 'poly' string search in title/abstract | Polymer-related documents |

| Paragraph Processing | 23.3 million paragraphs | Text unit segmentation | Processable text units |

Experimental Protocol: Corpus Assembly and Polymer Filtering

- Data Collection: Access full-text articles through publisher APIs with appropriate authentication and licensing.

- Text Extraction: Convert articles from PDF/XML formats to plain text, preserving paragraph structure.

- Polymer Filtering: Apply string-based filtering using the term 'poly' in titles and abstracts to identify polymer-relevant documents.

- Paragraph Segmentation: Process each document into discrete paragraphs, treating each as an independent text unit for downstream processing.

Two-Stage Text Filtering System

The pipeline implements a dual-stage filtering approach to identify paragraphs containing extractable polymer-property data while minimizing computational costs associated with processing irrelevant text [1].

Figure 2. Two-Stage Paragraph Filtering System. The heuristic filter identifies property-relevant text, while the NER filter confirms the presence of complete, extractable records [1].

Experimental Protocol: Heuristic Filtering

- Property List Definition: Identify 24 target polymer properties based on significance and downstream application needs (Table 2).

- Keyword Dictionary Creation: Manually curate property-specific keywords and co-referents through literature review.

- Paragraph Scoring: Implement regular expressions to flag paragraphs containing property mentions.

- Result Compilation: Collect approximately 2.6 million paragraphs (11% of original) that pass heuristic filters.

Experimental Protocol: Named Entity Recognition (NER) Filtering

- Entity Definition: Configure the NER model to detect four critical entity types: material name, property name, property value, and unit.

- Model Application: Process heuristic-filtered paragraphs through MaterialsBERT to identify paragraphs containing all required entities.

- Completeness Verification: Select only paragraphs with complete entity sets (all four entity types present) for downstream extraction.

- Output Generation: Produce a refined set of approximately 716,000 paragraphs (3% of original) with verified extractable records.

Data Extraction Models and Methodologies

The pipeline employs multiple natural language processing models for data extraction, each with distinct strengths and optimization characteristics [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Data Extraction Models

| Model | Architecture | Parameters | Extraction Quantity | Quality Metrics | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT | Transformer-based NER | ~110M (base) | ~300K records from abstracts | F1: 0.885 (PolymerAbstracts) | Lower inference cost |

| GPT-3.5 | Generative LLM | 175B | >1M records from full-text | High precision with few-shot learning | Significant API costs |

| LlaMa 2 | Open-source LLM | 7B-70B | Comparable to GPT-3.5 | Competitive with commercial LLMs | High hardware requirements |

Experimental Protocol: MaterialsBERT Implementation

- Model Selection: Utilize MaterialsBERT, a BERT-based model pre-trained on 2.4 million materials science abstracts [9].

- Fine-Tuning: Adapt the base model using the PolymerAbstracts dataset (750 annotated abstracts) for polymer-specific entity recognition.

- Entity Annotation: Implement an 8-class ontology: POLYMER, POLYMERCLASS, PROPERTYVALUE, PROPERTYNAME, MONOMER, ORGANICMATERIAL, INORGANICMATERIAL, MATERIALAMOUNT.

- Training Configuration: Use cross-entropy loss, dropout (p=0.2), and sequence truncation at 512 tokens.

- Inference: Process filtered paragraphs to extract structured property records.

Experimental Protocol: LLM-Based Extraction (GPT-3.5/LlaMa 2)

- Prompt Engineering: Design few-shot learning prompts with task-specific examples to guide extraction.

- API Integration: Configure API calls with appropriate parameters (temperature, max_tokens) for structured output.

- Output Parsing: Implement post-processing to convert LLM responses to structured format.

- Cost Optimization: Batch process paragraphs and implement caching to reduce API calls.

Target Polymer Properties

The pipeline is configured to extract 24 key polymer properties selected for their significance in materials informatics and application relevance [1].

Table 3: Target Polymer Properties for Extraction

| Property Category | Specific Properties | Application Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Properties | Glass transition temperature, Melting point, Thermal stability | Polymer processing, application temperature range |

| Mechanical Properties | Tensile strength, Elastic modulus, Toughness | Structural applications, material selection |

| Optical Properties | Refractive index, Bandgap, Transparency | Dielectric aging, breakdown, optoelectronics |

| Transport Properties | Gas permeability, Ionic conductivity | Filtering, distillation, energy applications |

| Solution Properties | Intrinsic viscosity, Solubility parameters | Solution processing, formulation design |

Successful implementation of the polymer data extraction pipeline requires specific computational resources and software tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Language Models | MaterialsBERT, GPT-3.5, LlaMa 2 | Core extraction capabilities for text understanding |

| Computational Framework | Python, PyTorch/TensorFlow | Model implementation and training |

| Data Processing | SpaCy, NLTK, Pandas | Text preprocessing and data manipulation |

| Orchestration | Apache Airflow, Prefect | Workflow management and scheduling |

| Data Storage | Data warehouses (BigQuery), Data lakes (S3) | Structured and unstructured data storage |

| Annotation Tools | Prodigy, Label Studio | Manual annotation for model training |

This application note has detailed the architecture and implementation protocols for a general-purpose polymer data extraction pipeline that successfully processes millions of scientific articles to construct structured polymer-property databases. The modular design, combining heuristic filtering with advanced NLP models, demonstrates the feasibility of large-scale automated data extraction from materials science literature. The pipeline has been validated through the extraction of over one million property records for more than 106,000 unique polymers, creating a valuable resource for materials informatics and accelerating polymer discovery and design. The methodologies described provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing similar data extraction capabilities in their own polymer informatics research.

The ever-increasing number of materials science articles, growing at a rate of 6% compounded annually, makes it increasingly challenging to infer chemistry-structure-property relations from literature manually [9]. This data scarcity in materials informatics stems from quantitative material property information being "locked away" in publications written in natural language that is not machine-readable [9]. To address this challenge, researchers have developed MaterialsBERT, a domain-specific language model trained on millions of materials science abstracts to enable automated data extraction from scientific literature [9].

MaterialsBERT represents a specialized adaptation of the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture, pre-trained specifically on materials science text corpora [9]. Unlike general-purpose language models, MaterialsBERT understands materials-specific notations, jargons, and the complex nomenclature system used in polymer science, including commonly used names, acronyms, synonyms, and historical terms [1]. This domain specialization enables superior performance in natural language processing (NLP) tasks specific to materials science, particularly for polymer data extraction.

Table: Comparison of Domain-Specific BERT Models for Scientific Applications

| Model Name | Base Architecture | Training Corpus | Primary Domain | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT | PubMedBERT | 2.4M materials science abstracts [9] | Materials Science (Polymers) | Property extraction, NER, relation classification |

| MatSciBERT | SciBERT | ~285M words from materials papers [18] | Materials Science (General) | NER, abstract classification, relation classification |

| BioBERT | BERT-base | Biomedical corpora [9] | Biomedical | Biomedical text mining |

| ChemBERT | BERT-base | Chemical literature [9] | Chemistry | Chemical entity recognition |

Model Architecture and Training Methodology

Base Architecture and Pre-training

MaterialsBERT builds upon the transformer-based BERT architecture, which has become the de facto solution for numerous NLP tasks [9]. The model embodies the transfer learning paradigm where a language model is pre-trained on massive corpora of unlabeled text using unsupervised objectives, then reused for specific NLP tasks. The resulting BERT encoder generates token embeddings for input text that are conditioned on all other input tokens, making them context-aware [9].

For MaterialsBERT, researchers initialized the model with PubMedBERT weights and continued pre-training on 2.4 million materials science abstracts [9]. This domain-adaptive pre-training approach follows methodologies established by models like BioBERT and FinBERT, where the base BERT model undergoes additional training on domain-specific text [18]. The vocabulary overlap between the materials science corpus and SciBERT vocabulary was approximately 53.64%, justifying the use of SciBERT as the foundation model [18].

Named Entity Recognition Architecture

The NER architecture employing MaterialsBERT uses a BERT-based encoder to generate representations for tokens in the input text [9]. These representations serve as inputs to a linear layer connected to a softmax non-linearity that predicts the probability of the entity type for each token. During training, the cross-entropy loss optimizes the entity type predictions, with the highest probability label selected as the predicted entity type during inference [9].

The model uses a dropout probability of 0.2 in the linear layer to prevent overfitting [9]. Since most abstracts fall within the BERT model's input sequence limit of 512 tokens, sequences exceeding this length are truncated as per standard practice [9].

Experimental Protocols and Annotation Framework

Corpus Construction and Annotation

The development of MaterialsBERT involved creating a specialized annotation framework tailored to polymer science. Researchers filtered a corpus of 2.4 million materials science papers to obtain polymer-relevant abstracts containing the string 'poly' and numeric information using regular expressions [9]. From this corpus, 750 abstracts were selected for manual annotation using a carefully designed ontology.

Table: Annotation Ontology for Polymer Data Extraction

| Entity Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| POLYMER | Specific polymer names | "polyethylene", "PMMA" |

| POLYMER_CLASS | Categories or classes of polymers | "polyester", "nylon" |

| PROPERTY_VALUE | Numerical property values | "125", "0.45" |

| PROPERTY_NAME | Names of material properties | "glass transition temperature", "tensile strength" |

| MONOMER | Monomer units constituting polymers | "ethylene", "styrene" |

| ORGANIC_MATERIAL | Organic compounds and materials | "solvents", "additives" |

| INORGANIC_MATERIAL | Inorganic compounds and materials | "silica", "metal oxides" |

| MATERIAL_AMOUNT | Quantities of materials | "2 grams", "5 mol%" |

Annotation was performed by three domain experts using the Prodigy annotation tool over three iterative rounds [9]. With each round, annotation guidelines were refined, and previous abstracts were re-annotated using the updated guidelines. To assess inter-annotator agreement, 10 abstracts were annotated by all annotators, yielding a Fleiss Kappa of 0.885 and pairwise Cohen's Kappa values of (0.906, 0.864, 0.887), indicating strong annotation consistency [9].

The annotated dataset, termed PolymerAbstracts, was split into 85% for training, 5% for validation, and 10% for testing [9]. Prior to manual annotation, researchers automatically pre-annotated abstracts using entity dictionaries to expedite the annotation process [9].

Model Training and Evaluation

The training protocol for the NER model involved using the annotated PolymerAbstracts dataset with MaterialsBERT as the encoder. The model was trained to predict entity types for each token in the input sequence, with the cross-entropy loss function optimizing the predictions [9].

Evaluation compared MaterialsBERT against multiple baseline encoders across five named entity recognition datasets [9]. The training and evaluation settings remained identical across all encoders tested for each dataset to ensure fair comparison. MaterialsBERT demonstrated superior performance, outperforming other baseline models in three out of five NER datasets [9].

Data Extraction Pipeline and Implementation

End-to-End Extraction Workflow

The complete data extraction pipeline utilizing MaterialsBERT processes polymer literature through a multi-stage workflow [9] [1]. This pipeline begins with corpus collection, proceeds through text processing and entity recognition, and culminates in structured data output.

Full-Text Extraction with Hybrid Filtering

Recent advancements have extended MaterialsBERT to full-text article processing using a hybrid filtering approach [1]. This system processes 23.3 million paragraphs from 681,000 polymer-related articles through a dual-stage filtering mechanism:

Heuristic Filter: Applies property-specific patterns to identify paragraphs mentioning target polymer properties or co-referents, reducing the corpus from 23.3 million to approximately 2.6 million paragraphs (~11%) [1]

NER Filter: Utilizes MaterialsBERT to identify paragraphs containing all necessary named entities (material name, property name, property value, unit), further refining the corpus to about 716,000 paragraphs (~3%) containing complete extractable records [1]

This filtering strategy enables efficient processing of full-text articles while maintaining high-quality data extraction. The pipeline successfully extracted over one million records corresponding to 24 properties of more than 106,000 unique polymers from full-text journal articles [1].

Performance Analysis and Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The MaterialsBERT-based extraction pipeline demonstrated exceptional efficiency and scalability in processing polymer literature [9]. In benchmark tests, the system needed only 60 hours to extract approximately 300,000 material property records from about 130,000 abstracts [9] [19]. This extraction rate significantly surpasses manual curation efforts, as evidenced by comparison with the PoLyInfo database, which contains over 492,000 material property records manually curated over many years [19].

Table: Data Extraction Performance Comparison

| Extraction Method | Records Extracted | Source Documents | Processing Time | Primary Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT (Abstracts) | ~300,000 [9] | ~130,000 abstracts [9] | 60 hours [9] | Multiple polymer properties |

| MaterialsBERT (Full-Text) | >1,000,000 [1] | ~681,000 articles [1] | Not specified | 24 targeted properties |

| Manual Curation (PoLyInfo) | ~492,000 [19] | Not specified | Many years [19] | Multiple polymer properties |

Comparison with LLM-Based Approaches

Recent studies have compared MaterialsBERT performance against large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3.5 and LlaMa 2 for polymer data extraction [1]. While LLMs offer competitive performance, MaterialsBERT provides a more computationally efficient solution for large-scale extraction tasks. Researchers evaluated these models across four critical performance categories: quantity, quality, time, and cost of data extraction [1].

The hybrid approach combining MaterialsBERT with LLMs represents the state-of-the-art, where MaterialsBERT serves as an effective filter to identify relevant paragraphs, reducing unnecessary LLM prompting and optimizing computational costs [1]. This combined approach leverages the precision of MaterialsBERT for entity recognition with the relationship extraction capabilities of LLMs.

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing MaterialsBERT for polymer data extraction requires specific computational "reagents" and resources. The following table details the essential components and their functions in the research workflow.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for MaterialsBERT Implementation

| Component | Type | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT Model | Pre-trained Language Model | Token embedding and entity recognition | Available from original research; based on PubMedBERT architecture [9] |

| PolymerAbstracts Dataset | Annotated Training Data | Model fine-tuning and evaluation | 750 manually annotated abstracts with 8 entity types [9] |

| Prodigy Annotation Tool | Software | Manual annotation of training data | Commercial tool; alternatives include BRAT or Doccano [9] |

| SciBERT Tokenizer | Text Processing | Vocabulary tokenization | Uses SciBERT vocabulary with 53.64% overlap to materials science corpus [18] |

| Polymer Scholar Platform | Database Interface | Data exploration and access | Web-based interface (polymerscholar.org) for accessing extracted data [9] |

| Full-Text Article Corpus | Data Source | Primary extraction material | 2.4 million materials science articles from multiple publishers [1] |

Applications and Impact

The data extracted through MaterialsBERT-powered pipelines has enabled diverse applications across polymer science. Researchers have analyzed the extracted data for applications including fuel cells, supercapacitors, and polymer solar cells, recovering non-trivial insights [9]. The structured data has also been used to train machine learning predictors for key properties like glass transition temperature [9].

The Polymer Scholar platform (polymerscholar.org) provides accessible exploration of extracted material property data, allowing researchers to locate material property information through keyword searches rather than manual literature review [9] [19]. This capability significantly accelerates materials research workflows and facilitates data-driven materials discovery.

Beyond immediate data extraction, the long-term vision for MaterialsBERT applications includes using the extracted data to train predictive models that can forecast material properties, ultimately enabling an extraordinary pace of materials discovery [19]. This pipeline represents a critical component in the emerging paradigm of data-driven materials science, where historical knowledge locked in literature becomes actionable for guiding future research directions.

The exponential growth of polymer science literature presents a significant challenge for researchers seeking to infer chemistry-structure-property relationships from published studies. Named Entity Recognition (NER) has emerged as a critical natural language processing (NLP) technique for automatically extracting and structuring polymer information from unstructured scientific text. This process involves identifying and classifying key entities—such as polymer names, property values, and material classes—into predefined categories to build machine-readable knowledge bases [9].

The development of specialized NER systems for polymer science addresses domain-specific challenges, including the expansive chemical design space of polymers and the prevalence of non-standard nomenclature featuring acronyms, synonyms, and historical terms [1]. Unlike small molecules, polymer names often cannot be directly converted to standardized representations like SMILES strings, requiring more sophisticated information extraction approaches [20]. This application note details the ontologies, methodologies, and practical protocols for implementing NER systems tailored to polymer science, enabling researchers to efficiently transform unstructured literature into structured, analyzable data.

Polymer NER Ontologies and Entity Definitions

Core Entity Types for Polymer Science

A well-defined ontology is fundamental to effective NER in specialized domains. The PolyNERE ontology and similar frameworks define entity types specifically designed to capture essential information from polymer literature [21]. These ontologies typically include the following core entity types:

Table 1: Core Entity Types in Polymer NER Ontologies

| Entity Type | Description | Example Phrases | Total Occurrences in PolymerAbstracts |

|---|---|---|---|

| POLYMER | Material entities that are polymers | "polyethylene", "PMMA", "nylon-6" | 7,364 |

| PROPERTY_NAME | Material property being described | "glass transition temperature", "tensile strength", "bandgap" | 4,535 |

| PROPERTY_VALUE | Numeric value and its unit corresponding to a material property | "165 °C", "45 MPa", "3.2 eV" | 5,800 |

| POLYMER_CLASS | Broad terms for classes of polymers | "polyolefins", "polyesters", "thermoplastics" | 1,476 |

| MONOMER | Repeat units for a POLYMER entity | "ethylene", "styrene", "methyl methacrylate" | 2,074 |

| INORGANIC_MATERIAL | Inorganic additives in polymer formulations | "silica nanoparticles", "montmorillonite clay" | 1,272 |

| ORGANIC_MATERIAL | Organic materials that are not polymers (plasticizers, cross-linkers) | "dioctyl phthalate", "dicumyl peroxide" | 914 |

| MATERIAL_AMOUNT | Amount of a particular material in a formulation | "30 wt%", "5 phr" | 1,143 |

This structured ontology enables the capture of complex polymer systems and their characteristics, facilitating the extraction of meaningful relationships between chemical structures, processing conditions, and resulting properties [20] [9]. The "OTHER" category serves as a default for tokens not belonging to these specific classes, representing 147,115 occurrences in the annotated PolymerAbstracts dataset [20].

Specialized NER Frameworks

The PolyNERE framework represents a recent advancement in polymer NER, featuring a novel ontology with multiple entity types, relation categories, and support for various NER settings [21]. This resource includes a high-quality NER and relation extraction corpus comprising 750 polymer abstracts annotated using their customized ontology. Distinctive features include the ability to assert entities and relations at different levels and providing supporting evidence to facilitate reasoning in relation extraction tasks [21].

Quantitative Performance Analysis of Polymer NER Methods

Comparison of Extraction Approaches

Recent research has evaluated multiple approaches for polymer data extraction, ranging from specialized NER models to general-purpose large language models (LLMs). The performance characteristics of these methods vary significantly across different metrics:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Polymer Data Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Data Source | Extraction Scale | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT (NER) | Abstracts | ~300,000 records from ~130,000 abstracts in 60 hours [20] | Superior to baseline models in 3/5 NER datasets [20] | Challenging entity relationships across extended passages [1] |

| GPT-3.5 & LlaMa 2 (LLM) | Full-text articles | >1 million records from 681,000 articles [1] | Effective for NER, classification, QA with limited datasets [1] | Significant computational costs and monetary expenses [1] |

| Hybrid Pipeline (NER + LLM) | Full-text paragraphs | 716,000 relevant paragraphs from 23.3 million total [1] | Extracted 24 properties for 106,000 unique polymers [1] | Requires careful filtering to optimize costs [1] |

Scale of Extracted Polymer Data