Machine Learning for Polymer Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) applications in polymer property prediction, a field revolutionizing materials science and drug development.

Machine Learning for Polymer Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) applications in polymer property prediction, a field revolutionizing materials science and drug development. It covers foundational concepts, including the unique challenges of polymer representation and data scarcity. The guide delves into methodological approaches, from classical algorithms to advanced deep learning, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting common issues like data quality and model generalization. Through a comparative analysis of techniques and validation metrics, it equips researchers and scientists with the knowledge to build reliable ML models, accelerate material discovery, and optimize polymer design for biomedical applications.

The Foundation: Core Concepts and Challenges in Polymer Informatics

Why Machine Learning for Polymers? Moving Beyond Trial-and-Error

The development of novel polymer materials has traditionally relied on empirical approaches characterized by rational design based on prior knowledge and intuition, followed by iterative, trial-and-error testing and redesign. This process results in exceptionally long development cycles, complicated by a design space with high dimensionality [1]. The unique multilevel, multiscale structural characteristics of polymers—combined with the high number of variables in both synthesis and processing—create virtually limitless structural possibilities and design potential [2]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative solution to these challenges, enabling researchers to extract patterns from complex data, identify key drivers of functionality, and make accurate predictions about new polymer systems without exhaustive experimentation.

ML-Driven Predictive Performance in Polymer Science

Substantial quantitative evidence demonstrates ML's capability to predict key polymer properties, thereby reducing experimental workload. The experimental results from the unified multimodal framework Uni-Poly, which integrates diverse data modalities including SMILES, 2D graphs, 3D geometries, fingerprints, and textual descriptions, showcase this predictive power across several critical properties [3].

Table 1: Performance of Uni-Poly Framework in Predicting Polymer Properties

| Property | Description | Prediction Performance (R²) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Temperature at which polymer transitions from hard/glassy to soft/rubbery state | ~0.90 | Best-predicted property, strong correlation with structure [3] |

| Thermal Decomposition Temperature (Td) | Temperature of onset of polymer decomposition | 0.70-0.80 | Strong predictive capability for thermal stability [3] |

| Density (De) | Mass per unit volume | 0.70-0.80 | Accurate prediction of physical properties [3] |

| Electrical Resistivity (Er) | Resistance to electrical current flow | 0.40-0.60 | Challenging property, benefits from multimodal data [3] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Temperature at which crystalline regions melt | 0.40-0.60 | Most improved with multimodal approach (+5.1% R²) [3] |

The integration of multiple data modalities proves particularly valuable, with Uni-Poly consistently outperforming all single-modality baselines across evaluated properties, achieving at least a 1.1% improvement in R² across various tasks [3]. This demonstrates that combining structural representations with domain-specific knowledge captures complementary information that neither approach can capture alone.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing ML for Polymer Property Prediction

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for developing and implementing an ML pipeline for polymer property prediction.

Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Data Source Identification: Determine whether to use mined data (from published studies/databases) or data collected in-house. For polymer science, relevant databases may include Polymer Genome, AFLOW library, Materials Project, or Citrine Informatics [1].

- Data Quality Assessment: Perform initial data investigation using methods like

.describe()and.info()in Python to identify missing values, spurious data, and outliers [1]. - Data Cleaning: Address missing or NaN values, and eliminate observations containing obviously incorrect data to ensure dataset integrity [1].

- Data Representation: Convert polymer structures into machine-readable formats. Common representations include:

- SMILES: Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System for sequential representation [3]

- Molecular Fingerprints: Fixed-length bit vectors encoding structural information [3]

- 2D Graph Representations: Graphs where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [3]

- 3D Geometries: Spatial atomic coordinates capturing molecular conformation [3]

Model Selection and Training

- Algorithm Choice: Select appropriate ML algorithms based on data quantity and problem type. For smaller datasets (50-300 samples), random forests, support vector machines, or Bayesian methods often perform well [1].

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset into training, validation, and test sets using an 80/10/10 or 70/15/15 split to enable robust performance evaluation.

- Feature Scaling: Normalize or standardize input features to ensure consistent scaling across variables, improving model convergence and performance.

- Model Training: Train the selected ML model on the training dataset, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning to optimize model architecture and learning parameters.

- Active Learning Implementation (Optional): For optimal experimental design, use ensemble or statistical ML methods that return uncertainty values alongside predictions. Initialize new experiments targeting regions of feature space with high uncertainty to maximize information gain [1].

Model Validation and Analysis

- Performance Evaluation: Assess model performance on the held-out test set using metrics relevant to the prediction task (e.g., R², Mean Absolute Error, Root Mean Square Error).

- Feature Importance Analysis: Conduct explainable AI analysis to identify which structural features or chemical substructures most significantly influence the target property, providing novel physicochemical insights [2].

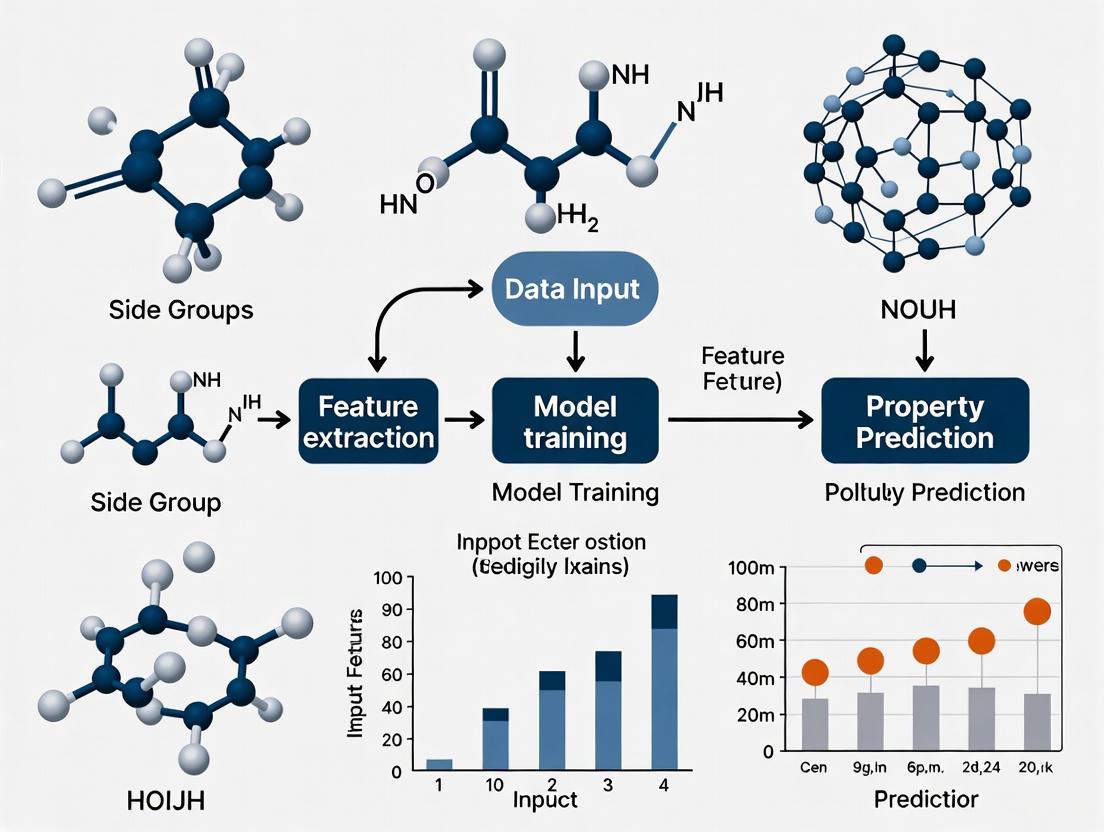

Workflow Visualization: ML-Driven Polymer Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) paradigm, which couples high-throughput experimentation with ML to accelerate the discovery and development of novel polymer materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ML for polymer research requires specific computational tools and data resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Polymer Science

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Genome | Web-based ML Platform | Predicts polymer properties and generates in silico datasets [1] | Rapid screening of polymer candidates prior to synthesis |

| Uni-Poly Framework | Multimodal Representation | Integrates SMILES, graphs, 3D geometries, fingerprints, and text [3] | Unified polymer representation for enhanced property prediction |

| AFLOW Library | Materials Database | Provides curated data on material properties for mining [1] | Training data for ML models predicting thermal properties |

| Python Scikit-learn | ML Library | Offers algorithms for regression, classification, and data preprocessing [1] | Implementing random forest models for structure-property mapping |

| Active Learning Pipeline | Experimental Strategy | Uses uncertainty quantification to guide next experiments [1] | Efficient exploration of polymer chemical space with focused experiments |

| Poly-Caption Dataset | Textual Knowledge | Provides domain-specific polymer descriptions generated by LLMs [3] | Enhancing predictions with application context and domain knowledge |

| Terpendole C | Terpendole C, MF:C32H41NO5, MW:519.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Terpendole E | Terpendole E, MF:C28H39NO3, MW:437.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Machine learning represents a paradigm shift in polymer science, moving the field beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches toward a data-driven future. By leveraging ML algorithms, researchers can now navigate the complex, high-dimensional design space of polymers with unprecedented efficiency, extracting meaningful structure-property relationships and accelerating the discovery of novel materials with tailored characteristics. The integration of multimodal data representations, combined with active learning strategies, creates a powerful framework for polymer informatics that promises to significantly shorten development cycles and open new frontiers in polymer design for applications ranging from biomedicine to advanced manufacturing.

Application Note: Navigating the Core Challenges in Polymer Informatics

The application of machine learning (ML) to polymer property prediction represents a paradigm shift in materials science, accelerating the design of polymers for applications ranging from drug delivery to aerospace. However, this data-driven revolution faces three fundamental hurdles: the vast design space of possible polymer compositions and structures, the challenge of finding meaningful representation for these complex molecules, and the pervasive issue of data scarcity for many key properties. This note details these challenges and presents validated, cutting-edge protocols to overcome them.

The immense combinatorial possibilities of monomers, sequences, and processing conditions create a design space that is impossible to explore exhaustively through experiments alone [4] [5]. Furthermore, representing a polymer's complex structure in a way that a machine learning model can understand—capturing features from atomic composition to chain architecture—is a non-trivial task [6] [5]. Finally, high-quality, annotated experimental data for properties like glass transition temperature or Flory-Huggins parameters are often scarce, creating a significant bottleneck for training accurate and generalizable models [7] [8] [6].

The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of these challenges and the quantitative performance of modern solutions, followed by structured protocols for implementation.

Quantitative Analysis of ML Performance in Polymer Property Prediction

The table below summarizes the performance of various advanced ML architectures in overcoming these fundamental hurdles, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance of Machine Learning Models in Polymer Informatics

| Model Architecture | Primary Application / Challenge Addressed | Key Features / Representation | Reported Performance (R²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Predicting mechanical properties of natural fiber composites (Non-linear relationships) | Processes tabular data (fiber type, matrix, treatment); captures complex synergies | Up to 0.89 on composite mechanical properties | [9] [10] |

| Ensemble of Experts (EE) | Predicting Tg and χ parameter (Data scarcity) | Uses pre-trained "experts" to generate molecular fingerprints from tokenized SMILES | Significantly outperforms standard ANNs in data-scarce regimes | [7] |

| Quantum-Transformer Hybrid (PolyQT) | General property prediction (Data sparsity) | Fuses Quantum Neural Networks with Transformer encoder; uses SMILES strings | ~0.90 on various property datasets (e.g., Dielectric Constant) | [8] |

| Large Language Model (LLaMA-3-8B) | Predicting thermal properties (Leveraging linguistic representation) | Fine-tuned on canonical SMILES strings; eliminates need for handcrafted fingerprints | Close to, but does not surpass, traditional fingerprinting methods | [6] |

| Hybrid CNN-MLP Model | Predicting stiffness of carbon fiber composites (Microstructure representation) | Trained on microstructure images and two-point statistics | >0.96 on stiffness tensor prediction | [9] |

Table 2: Key Resources for Polymer Informatics Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES Strings | A line notation for representing molecular structures using ASCII strings, enabling the use of NLP techniques. | Used as the primary input for Transformer models (polyBERT), LLMs, and the Ensemble of Experts system [7] [8] [6]. |

| Polymer Tokenizer | Converts a polymer's SMILES string into a sequence of tokens (e.g., atoms, bonds, asterisks for repeat units) that can be processed by a model. | Critical for the PolyQT model and polyBERT to interpret polymer-specific structures from SMILES [8]. |

| Polymer Genome Fingerprints | Hand-crafted numerical representations that capture a polymer's features at atomic, block, and chain levels. | Serves as a benchmark representation for traditional ML models, providing multi-scale structural information [6]. |

| Graph-Based Representations | Represents a polymer as a molecular graph where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. | Used by models like polyGNN to learn polymer embeddings that balance prediction speed and accuracy [6]. |

| Optuna | A hyperparameter optimization framework used to automatically search for the best model configuration. | Employed to find the optimal DNN architecture (number of layers, neurons, learning rate) for predicting composite properties [9]. |

| Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) | A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that significantly reduces computational overhead for large models. | Used to fine-tune the LLaMA-3-8B model on polymer property data without the need for full retraining [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing an Ensemble of Experts for Data-Scarce Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for employing an Ensemble of Experts (EE) to predict polymer properties, such as glass transition temperature (Tg), when labeled data is severely limited [7].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Expert Model Pre-Training

- Input: Assemble large, high-quality datasets for physical properties that are related to, but distinct from, the ultimate target property (e.g., various thermodynamic parameters).

- Action: Train multiple independent Artificial Neural Network (ANN) "experts" on these large datasets. Each expert learns to predict a specific property from a polymer's structural representation.

- Output: A collection of pre-trained expert models.

Fingerprint Generation

- Input: The polymer structures for the data-scarce target task, represented as tokenized SMILES strings.

- Action: Pass each polymer's tokenized representation through the ensemble of pre-trained experts. The activations from a hidden layer of these networks are concatenated to form a dense, informative "molecular fingerprint."

- Output: A database of fingerprint vectors for all polymers in the target dataset.

Target Predictor Training

- Input: The limited labeled dataset for the target property (e.g., Tg), coupled with the generated fingerprint vectors as input features.

- Action: Train a small, final predictor (e.g., a ridge regression model or a small ANN) using the fingerprints as inputs and the scarce target labels as outputs.

- Output: A final model capable of accurate predictions for the target property, leveraging knowledge transferred from the experts.

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning Large Language Models for Polymer Property Prediction

This protocol describes the process of adapting general-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) to predict polymer properties directly from their SMILES string representation [6].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Curation and Canonicalization

- Input: A curated dataset of polymer SMILES strings and their associated property values (e.g., Tg, Tm, Td).

- Action: Standardize all SMILES strings to a canonical form to ensure consistent representation, as a single polymer can have multiple valid SMILES strings.

- Output: A clean, canonicalized dataset.

Instruction Prompt Engineering

- Input: The canonicalized dataset.

- Action: Transform each data point into an instruction-following format for the LLM. The optimal prompt structure found in recent research is:

User: If the SMILES of a polymer is <SMILES>, what is its <property>? Assistant: smiles: <SMILES>, <property>: <value> <unit>

- Output: An instruction-formatted training dataset.

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

- Input: The instruction-formatted dataset and a pre-trained LLM (e.g., LLaMA-3-8B).

- Action: Fine-tune the LLM using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA freezes the pre-trained model weights and injects trainable rank-decomposition matrices into the transformer layers, dramatically reducing the number of parameters that need to be updated.

- Output: A fine-tuned LLM specialized in polymer property prediction.

Validation and Inference

- Input: A held-out test set of polymers.

- Action: Evaluate the fine-tuned model by providing the SMILES string in the established prompt format. The model will generate a text response containing the predicted property value and unit.

- Output: Quantitative performance metrics (MAE, R²) and a deployable predictive model.

Protocol 3: Building a Quantum-Transformer Hybrid Model for Sparse Data

This protocol outlines the procedure for constructing a novel Polymer Quantum-Transformer Hybrid Model (PolyQT) designed to enhance prediction accuracy and generalization when dealing with sparse polymer datasets [8].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Tokenization

- Input: Polymer structures as SMILES strings.

- Action: Use a polymer-specific tokenizer to break down the SMILES string into a sequence of fundamental tokens (e.g., atoms, bonds, asterisks for repetition).

- Output: A tokenized sequence ready for the transformer.

Feature Extraction via Transformer

- Input: The tokenized sequence.

- Action: Process the sequence through a Transformer encoder (e.g., similar to polyBERT). The self-attention mechanism within the transformer captures the complex contextual relationships between tokens in the polymer sequence.

- Output: A dense, context-aware feature vector representing the polymer.

Quantum-Enhanced Processing

- Input: The feature vector from the transformer.

- Action: Map the classical feature vector into a quantum state and process it through a Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC), which acts as the Quantum Neural Network (QNN). The quantum entanglement and superposition properties of the QNN are theorized to capture highly complex, non-linear relationships in the data that are difficult for classical models to learn.

- Output: A quantum-processed feature representation.

Property Prediction

- Input: The output from the QNN.

- Action: The final output is measured from the quantum circuit and used to generate the property prediction.

- Output: A predicted value for the target polymer property.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into polymer science has revolutionized the process of property prediction and material design, fundamentally shifting from traditional trial-and-error approaches to data-driven virtual screening [11]. Central to this paradigm is the creation of effective machine-readable polymer representations, which serve as the critical input features for training robust predictive models [12]. The quality and appropriateness of these representations significantly influence model performance, generalizability, and interpretability [13] [3]. Unlike small molecules, polymers present unique representational challenges due to their stochastic nature, repeating monomeric structures, and sensitivity to multi-scale features including molecular weight, branching, and chain entanglement [13] [3]. This application note provides a comprehensive technical overview of the three predominant polymer representation schemes—SMILES, BigSMILES, and molecular fingerprints—within the context of ML for polymer property prediction. We detail experimental protocols for generating and converting between these representations, present quantitative performance comparisons, and visualize key workflows to equip researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these approaches in their polymer informatics pipelines.

Polymer Representation Schemes: Technical Foundations

SMILES Strings for Polymers

The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) provides a linear, string-based representation of molecular structures using ASCII characters to denote atoms, bonds, branches, and ring closures [14]. For polymers, the polymer-SMILES convention extends standard SMILES by explicitly marking connection points between monomers with the special token [*] [13]. This allows the representation of repeating monomer units while maintaining the syntactic rules of the SMILES format. A key consideration for ML applications is the non-uniqueness of SMILES strings; a single molecule can generate multiple valid SMILES representations through different atom traversal orders. To address this, canonicalization algorithms produce a standardized SMILES string for each molecule, ensuring consistency in representation [14]. However, data augmentation strategies in ML sometimes deliberately leverage non-canonical SMILES. For instance, using Chem.MolToSmiles(..., canonical=False, doRandom=True, isomericSmiles=True) can generate multiple SMILES strings per molecule, effectively expanding training datasets tenfold [15].

Table 1: SMILES String Examples and Applications in Polymer ML

| Polymer Type | SMILES Example | ML Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Homopolymer | "O=C(NCc1cc(OC)c(O)cc1)CCCC/C=C/C(C)C" |

Basic monomer structure input for property prediction [16] [13] |

| Polymer with Connection Points | "C([*])C([*])CC" |

Explicitly marks bonding sites for polymerization [17] |

| Augmented SMILES (Non-canonical) | "CC(O)C([*])" and "C([*])C(C)O" |

Data augmentation to improve model robustness [15] |

BigSMILES: Representing Stochastic Polymer Structures

BigSMILES is a structurally based line notation designed specifically to address the fundamental limitation of deterministic representations when applied to polymers: their intrinsic stochastic nature [17] [18]. A polymer is typically an ensemble of distinct molecular structures rather than a single, well-defined entity. BigSMILES introduces two key syntactic extensions over SMILES to handle this stochasticity: stochastic objects and bonding descriptors [17].

Stochastic Objects: Encapsulated within curly braces { }, a stochastic object acts as a proxy atom within a SMILES string, representing an ensemble of polymeric fragments. Its internal structure defines the constituent repeat units and end groups [17]. For example, a stochastic object for poly(ethylene-butene) reads: {[][$]CC[$],[$]CC(CC)[$][]}.

Bonding Descriptors: These specify how repeat units connect and are placed on atoms that form bonds with other units. Two primary types exist [17]:

- AA-type (

$): Atoms with$descriptors can connect to any other atom with a$descriptor. Ideal for vinyl polymers (e.g.,[$]-CC-[$]). - AB-type (

<,>): Atoms with<can only connect to atoms with>, enforcing specific connectivity as in polycondensation polymers like nylon-6,6:{[][<]C(=O)CCCCC(=O)[<],[>]NCCCCCCN[>][]}.

Table 2: BigSMILES Syntax and Components

| Component | Syntax | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Object | {repeat_units; end_groups} |

Defines ensemble of polymeric structures [17] | {[][$]CC[$],[$]CC(CC)[$][]} |

| AA-type Descriptor | [$] |

Allows connection to any atom with [$] [17] |

[$]CC[$] (Ethylene unit) |

| AB-type Descriptor | [<] and [>] |

Enforces specific pairwise connectivity [17] | [<]C(=O)CCCCC(=O)[<] (Diacid) |

| Terminal Descriptor | [] |

Indicates an uncapped end of the polymer chain [17] | {[]...repeat_units...[]} |

Molecular Fingerprints: Numerical Representation for Machine Learning

Molecular fingerprints are fixed-length bit vectors that numerically encode the presence or absence of specific molecular substructures or features [12] [14]. They are a cornerstone of traditional cheminformatics and remain highly competitive in modern ML pipelines for polymer property prediction [15] [11]. Their primary advantage is providing a direct, machine-readable numerical input that captures essential structural information.

Different fingerprint algorithms focus on different aspects of molecular structure, making them suitable for different predictive tasks. Common types used in polymer informatics include [15] [14]:

- Circular Fingerprints (ECFP/FCFP): Enumerate circular atom environments up to a specified radius, excellent for capturing local atom neighborhoods [14].

- Path-based Fingerprints (RDKit, Daylight): Encode linear and branched subgraphs of specified path lengths [14].

- Topological Torsion: Encodes sequences of four bonded atoms, capturing local torsional environments [14].

- Atom Pairs: Encode pairs of atoms and their topological distance [14].

- Predefined Keys (MACCS): Use a fixed dictionary of SMARTS patterns to test for specific functional groups [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Converting SMILES to Molecular Fingerprints using RDKit

This protocol converts a list of polymer-SMILES strings into RDK fingerprints, a common preprocessing step for training ML models [16] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- RDKit: An open-source cheminformatics library used for molecule manipulation and fingerprint generation [16].

- List of SMILES Strings: Input data representing polymer monomers or repeating units.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Import RDKit Dependencies

- Define SMILES List

- Convert SMILES to Mol Objects

Note: Validate

molobjects are notNoneto ensure successful parsing. - Generate Fingerprints

Note:

RDKFingerprintgenerates a topological fingerprint. Alternatively, useGetMorganFingerprintAsBitVect(mol, radius=2, nBits=2048)for a circular ECFP-type fingerprint [15] [19].

The resulting fps object is a list of ExplicitBitVect objects ready for use with scikit-learn or other ML libraries.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Multimodal Polymer Property Prediction Workflow

Advanced polymer ML models, such as the winning solution from the NeurIPS Open Polymer Challenge, often integrate multiple representation modalities [15] [3]. This protocol outlines a multi-stage pipeline for property prediction.

Workflow Diagram 1: Multimodal Polymer Property Prediction. This workflow integrates diverse data representations and model types to enhance predictive accuracy [15] [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Input: Collect or generate canonical polymer-SMILES strings [15].

- Feature Generation: Use RDKit to compute an extensive set of features for tabular models [15]:

- 2D/Graph Descriptors: All RDKit-supported molecular descriptors.

- Fingerprints: Morgan, Atom Pair, Topological Torsion, MACCS keys.

- Structural Features: Backbone/sidechain features, Gasteiger charge statistics, element composition [15].

- Data Augmentation: For sequence-based models (e.g., BERT), augment data by generating 10 non-canonical SMILES per molecule using

Chem.MolToSmiles(..., canonical=False, doRandom=True)[15].

Model Training and Selection

- Tabular Models: Employ AutoGluon or similar frameworks to train ensembles on the feature-engineered data. Optuna can be used for hyperparameter tuning and feature selection [15].

- Sequence-Based Models: Fine-tune a BERT model (e.g., ModernBERT, polyBERT) on the (augmented) SMILES data. Use a differentiated learning rate (backbone LR one magnitude lower than the regression head) to prevent overfitting [15].

- 3D Models: For 3D geometric data, use models like Uni-Mol-2. Generate 3D conformers for your SMILES strings using RDKit's ETKDG method [15].

Ensemble Prediction and Validation

- Inference: Generate 50 predictions per SMILES string for sequence models by leveraging different augmented views. Use the median as the final prediction to aggregate results [15].

- Ensembling: Combine predictions from tabular, BERT, and 3D models (e.g., via weighted averaging or stacking) to produce the final property prediction [15] [3].

- Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation and benchmark against single-modality baselines to ensure the ensemble provides a performance lift [15].

Performance Comparison and Application Scenarios

Quantitative Performance of Representation Modalities

The predictive performance of different polymer representations varies significantly across target properties, as demonstrated by unified multimodal frameworks like Uni-Poly [3].

Table 3: Performance Comparison (R²) of Representation Modalities on Various Properties [3]

| Property | Morgan Fingerprint | ChemBERTa (SMILES) | Uni-Mol (3D) | Uni-Poly (Multimodal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.85 | ~0.90 |

| Thermal Decomposition Temp (Td) | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.72 | ~0.79 |

| Density (De) | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.73 | ~0.77 |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.45 | ~0.56 |

| Electrical Resistivity (Er) | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.46 | ~0.47 |

Application Scenarios and Selection Guidelines

Workflow Diagram 2: Polymer Representation Selection Guide. A decision tree for selecting the most appropriate polymer representation based on the chemical system, data context, and project goals.

- BigSMILES Applications: Utilize BigSMILES when representing stochastic polymers, such as copolymers with random sequences, polymers with branching, or complex polymer architectures where connectivity is not deterministic [17] [18]. This representation is crucial for accurately encoding the ensemble nature of these materials, though ML models directly consuming BigSMILES are still an area of active development.

- SMILES String Applications: Canonical SMILES are ideal for sequence-based models like transformers (e.g., ChemBERTa, polyBERT) [13] [15]. They are also the standard input for generating other representations like fingerprints, graphs, and 3D conformers. Use non-canonical SMILES for data augmentation to improve model robustness [15].

- Fingerprint Applications: Fingerprints are most effective for traditional ML models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) and in scenarios with limited data, where their fixed-length, information-dense nature helps prevent overfitting [15] [11]. They excel at similarity searches and are easily integrated as features in tabular data pipelines. The winning solution in the NeurIPS Open Polymer Challenge relied heavily on extensive fingerprint and molecular descriptor feature engineering [15].

- Multimodal Applications: For the highest predictive accuracy across diverse properties, a multimodal approach is superior [3]. Integrate SMILES (for sequence models), graphs (for GNNs), fingerprints (for tabular models), and 3D geometries to capture complementary structural information. The Uni-Poly framework demonstrated that this approach consistently outperforms single-modality models [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Key Software Tools and Their Functions in Polymer Informatics

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecule manipulation, fingerprint & descriptor calculation [16] [15] | Converting SMILES to fingerprints (Protocol 1) |

| RDKFingerprint | Algorithm | Generates topological fingerprints from molecular structures [16] | Creating input vectors for ML models |

| Morgan Fingerprint (ECFP) | Algorithm | Generates circular fingerprints capturing atom environments [14] [19] | Similarity searching, QSAR modeling |

| AutoGluon | ML Framework | Automated machine learning for tabular data [15] | Training ensemble models on fingerprint/descriptor data |

| ModernBERT / polyBERT | Pre-trained Language Model | Fine-tunable transformer for sequence data [15] | Property prediction from (augmented) SMILES strings |

| Uni-Mol | 3D Deep Learning Model | Property prediction from 3D molecular geometries [15] [3] | Incorporating conformational information |

| BigSMILES | Line Notation | Represents stochastic polymer structures [17] [18] | Encoding copolymers and complex polymer ensembles |

| Thiethylperazine | Thiethylperazine|CAS 1420-55-9|For Research | Bench Chemicals | |

| Ticlatone | Ticlatone, CAS:70-10-0, MF:C7H4ClNOS, MW:185.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic selection and implementation of polymer representations—from the foundational SMILES and specialized BigSMILES to the numerically ready molecular fingerprints—form the cornerstone of successful machine learning applications in polymer science. As evidenced by leading research and competition-winning solutions, no single representation is universally superior; rather, their effectiveness is context-dependent [15] [3] [11]. Fingerprints remain powerful and computationally efficient for traditional ML models, especially with limited data. SMILES strings unlock the potential of modern deep learning architectures like transformers, particularly when augmented for robustness. BigSMILES addresses the critical challenge of representing stochasticity, essential for many real-world polymers. The most cutting-edge approaches, however, leverage multimodal frameworks that integrate these representations to capture complementary chemical information, consistently achieving state-of-the-art predictive performance [13] [3]. By adhering to the detailed protocols and guidelines provided in this application note, researchers can effectively navigate the polymer representation landscape, accelerating the discovery and design of novel polymeric materials with tailored properties.

Within the paradigm of machine learning (ML) for polymer research, the accurate prediction of key properties such as glass transition temperature (Tg), thermal conductivity, and density is paramount for accelerating the development of advanced materials. These properties fundamentally dictate a polymer's performance in applications ranging from flexible electronics and drug delivery systems to high-performance composites. Traditional methods for determining these properties rely heavily on resource-intensive experimental cycles or computationally expensive simulations. This document outlines structured protocols and application notes, framed within a broader thesis on ML-driven polymer informatics, to equip researchers with methodologies for building robust predictive models. The integration of ML not only accelerates virtual screening but also provides deeper insights into the complex process-structure-property relationships that govern polymer behavior.

Protocol: Predicting Thermal Conductivity of Liquid Crystalline Polymers

Background and Objective

The thermal conductivity of polymers is a critical property for heat management in next-generation electronics. Liquid crystalline polymers (LCPs) are a promising class of materials for this purpose, as their spontaneously oriented molecular chains can lead to higher thermal conductivity by reducing phonon scattering. However, their molecular design has historically been empirical. This protocol describes an ML-based classifier to identify polyimide chemical structures with a high probability of forming liquid crystalline phases, thereby facilitating the discovery of polymers with high thermal conductivity [20].

Experimental Workflow and Materials

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| PoLyInfo Database | A curated polymer property database used as the source for labeled and unlabeled polymer data [20]. |

| ZINC Database | A database of commercially available chemical compounds used to build a virtual library of molecular fragments [20]. |

| XenonPy & RadonPy | Python libraries used for calculating polymer descriptors, including RDKit and GAFF2 force field parameters [20]. |

| Tetracarboxylic Dianhydride & Diamine Monomers | The core building blocks for the de novo synthesis of the predicted polyimides [20]. |

Diagram 1: LCP discovery workflow.

Data Curation and Model Training Protocol

- Data Sourcing: Compile a dataset from the PoLyInfo database. The positive set (P) consists of 951 known liquid crystalline polymers. The unlabeled set (U) consists of 3,597 polymers with no recorded liquid crystallinity [20].

- Descriptor Calculation: For each polymer repeating unit, generate a 397-dimensional feature vector. This is a concatenation of:

- A 207-dimensional vector of RDKit descriptors.

- A 190-dimensional vector of quantitative descriptors from GAFF2 force field parameters, calculated using the RadonPy library. To account for periodicity, descriptors are computed on a decamer structure [20].

- Model Training and PU Learning: Train a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network as a binary classifier. Apply a Positive and Unlabeled (PU) learning algorithm to calibrate the classification probability, accounting for the lack of confirmed negative examples. Use Optuna for hyperparameter optimization, focusing on the number and width of hidden layers to minimize the validation F1 score [20].

- Virtual Screening: Decompose polyimide structures into symmetric building blocks (A-E). Use fragments from the ZINC database to generate a virtual library of 115,536 polyimides. Apply the trained classifier to this library and filter candidates based on a high median liquid crystal transition probability and low standard deviation [20].

Key Results and Performance

The trained MLP classifier demonstrated high performance in predicting liquid crystalline behavior, enabling the discovery of new polymers. The thermal conductivity of synthesized candidates was experimentally validated [20].

Table 1: Performance of the LCP Classifier and Discovered Properties

| Metric | Value / Result |

|---|---|

| Average Classification Accuracy | > 96% |

| Mean Recall | 0.92 |

| Mean Precision | 0.90 |

| Number of Candidates Filtered | 10,825 (from 115,536) |

| Experimentally Measured Thermal Conductivity | 0.722 - 1.26 W mâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹ |

Protocol: Predicting Mechanical Properties and Density of Natural Fiber Composites

Background and Objective

Predicting the mechanical properties and density of natural fiber composites is complex due to nonlinear interactions between fiber, matrix, surface treatments, and processing parameters. This protocol utilizes a Deep Neural Network (DNN) to accurately predict properties like tensile strength, modulus, and density, thereby reducing the need for extensive experimental testing [9] [10].

Experimental Workflow and Materials

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Natural Fibers (Flax, Cotton, Sisal, Hemp) | Reinforcement materials with densities ~1.48-1.54 g/cm³, used at 30 wt.% [9] [10]. |

| Polymer Matrices (PLA, PP, Epoxy Resin) | The continuous phase into which fibers are incorporated [9] [10]. |

| Surface Treatments (Untreated, Alkaline, Silane) | Chemical treatments applied to fibers to modify interface chemistry and improve adhesion [9] [10]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling Technique | A data augmentation method used to expand the original dataset of 180 samples to 1500 samples [9] [10]. |

Diagram 2: Composite property prediction.

Data Generation and Model Training Protocol

- Sample Preparation and Testing:

- Incorporate four natural fibers (flax, cotton, sisal, hemp) at 30 wt.% into three polymer matrices (PLA, PP, epoxy).

- Apply three surface treatments (untreated, alkaline, silane). Fabricate samples via twin-screw extrusion followed by injection molding (for PLA and PP) or casting (for epoxy).

- Measure mechanical properties (tensile strength, Young's modulus, elongation at break, impact toughness) according to ASTM standards. Determine density using Archimedes' method [9] [10].

- Data Preprocessing: The original dataset of 180 experimental samples is augmented to 1,500 samples using bootstrap resampling. Categorical variables (fiber type, matrix, treatment) are one-hot encoded. Continuous input features are standardized [9] [10].

- DNN Architecture and Training:

- Optimal Architecture: Four hidden layers with 128, 64, 32, and 16 neurons, respectively.

- Activation & Regularization: ReLU activation function and a 20% dropout rate to prevent overfitting.

- Optimizer: AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 10â»Â³ and a batch size of 64.

- The model hyperparameters are optimized using the Optuna framework [9] [10].

Key Results and Performance

The DNN model demonstrated superior performance in predicting the mechanical properties of natural fiber composites compared to other regression models, effectively capturing the complex, nonlinear interactions in the system [9] [10].

Table 2: DNN Model Performance for Composite Property Prediction

| Model | R² Value | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Up to 0.89 | Baseline (9-12% lower than gradient boosting) |

| Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | - | 9-12% higher than DNN |

| Random Forest | - | - |

| Linear Regression | - | - |

Protocol: Predicting Electron Density for Property Inference

Background and Objective

Electron density is the fundamental variable determining a material's ground-state properties. This protocol uses Machine Learning to directly predict the electron density of medium- and high-entropy alloys, from which other physical properties like energy can be inferred, enabling rapid exploration of composition spaces without repeatedly solving complex DFT calculations [21].

Methodological Workflow

- Descriptor Formulation: Employ easy-to-optimize, body-attached-frame descriptors that respect physical symmetries (e.g., translation, rotation). A key advantage is that the descriptor vector size remains nearly constant even as alloy complexity increases [21].

- Data-Efficient Learning with Active Learning:

- Use Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs), which provide native uncertainty quantification for each prediction.

- Implement Bayesian Active Learning (AL), where the model iteratively queries for new data points where its prediction uncertainty is highest. This strategy minimizes the amount of required training data [21].

- Training and Validation: The model is trained to map the developed descriptors to the electron density. Its performance is validated by comparing ML-predicted electron densities and inferred energies against reference DFT calculations across the composition space [21].

Key Results and Performance

The proposed framework showed high accuracy and generalizability while significantly reducing the computational cost of data generation.

Table 3: Efficiency Gains from Bayesian Active Learning

| Alloy System | Reduction in Training Data Points vs. Strategic Tessellation |

|---|---|

| Ternary (SiGeSn) | Factor of 2.5 |

| Quaternary (CrFeCoNi) | Factor of 1.7 |

Methodologies in Action: Building and Implementing Predictive ML Models

The design and development of new polymers with tailored properties is a complex, multi-dimensional challenge. Traditional experimental approaches, often reliant on trial-and-error, are struggling to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space of potential polymer structures. In this context, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool, accelerating materials discovery by establishing robust structure-property relationships from available data. The selection of an appropriate ML algorithm is critical for prediction accuracy and experimental applicability. This guide details three pivotal algorithms—Random Forest, XGBoost, and Neural Networks—within the context of polymer property prediction, providing researchers with the protocols and insights needed to deploy them effectively.

The performance of different ML algorithms can vary significantly depending on the polymer property being predicted, the dataset size, and the molecular representation. The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics from recent polymer informatics studies, providing a benchmark for algorithm selection.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms in Polymer Property Prediction

| Algorithm | Polymer System / Property | Performance Metrics | Key Advantage | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Vitrimer Glass Transition Temp. (Tg) | Part of an ensemble model that outperformed individual models. | Handles diverse feature representations effectively. | [11] |

| XGBoost | Natural Fiber Composite Mechanical Properties | Competitive performance, but outperformed by DNNs. | Powerful, scalable gradient boosting. | [9] |

| Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) | Homopolymer Density Prediction | MAE = 0.0497 g/cm³, R² = 0.8097 (Superior to RF, NN, and XGBoost) | Directly learns from molecular graph structure. | [22] |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Natural Fiber Composite Mechanical Properties | R² up to 0.89, 9-12% MAE reduction vs. gradient boosting | Captures complex nonlinear synergies between parameters. | [9] |

| Ensemble (Model Averaging) | Vitrimer Glass Transition Temp. (Tg) | Outperformed all seven individual benchmarked models. | Improves accuracy and robustness by reducing model variance. | [11] |

Algorithm Fundamentals and Application Protocols

Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that constructs a multitude of decision trees during training. It operates by aggregating the predictions of numerous de-correlated trees, which reduces overfitting and enhances generalization compared to a single decision tree.

Detailed Protocol for Polymer Property Prediction (e.g., Glass Transition Temperature Tg)

- Feature Representation: Convert polymer repeating units into machine-readable features. Common representations include:

- Molecular Descriptors: Use libraries like RDKit or Mordred to compute numerical descriptors representing topological, geometric, and electronic structures [11].

- Fingerprints: Generate binary vectors (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) that indicate the presence or absence of specific molecular substructures [11].

- Model Training:

- Implement the Random Forest regressor using a library such as Scikit-learn.

- Key hyperparameters to optimize via cross-validation include:

n_estimators: The number of trees in the forest (e.g., 100 to 1000).max_depth: The maximum depth of each tree.min_samples_split: The minimum number of samples required to split an internal node.max_features: The number of features to consider when looking for the best split.

- Validation and Interpretation:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation to assess model performance on unseen data.

- Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the model by quantifying the contribution of each input feature (e.g., specific functional groups) to the predicted property [22].

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting)

XGBoost is a highly efficient and scalable implementation of gradient boosted decision trees. It builds trees sequentially, where each new tree learns to correct the errors made by the previous ones, often leading to state-of-the-art results on structured data.

Detailed Protocol for Predicting Composite Mechanical Properties

- Data Preparation and Augmentation:

- Assemble a dataset containing features such as fiber type (e.g., flax, hemp), matrix polymer (e.g., PLA, PP), surface treatment (e.g., alkaline, silane), and processing parameters [9].

- For small experimental datasets (e.g., 180 samples), employ bootstrap-based data augmentation to create a larger, more robust training set (e.g., 1500 samples) [9].

- Preprocess categorical variables using one-hot encoding.

- Model Training and Optimization:

- Utilize the XGBoost library.

- The model is trained by iteratively adding decision trees to minimize a regularized objective function:

L(θ) = ∑ᵢ ℓ(yᵢ, ŷᵢ) + ∑ₜ Ω(hₜ), whereℓis a differentiable loss function (e.g., mean squared error) andΩis a regularization term that penalizes model complexity [23]. - Optimize key hyperparameters such as

learning_rate(η),max_depth, andsubsampleusing frameworks like Optuna [9].

- Performance Benchmarking:

- Compare the performance (R², MAE) of XGBoost against other models like linear regression, Random Forest, and DNNs to contextualize its predictive capability [9].

Neural Networks

Neural Networks, particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and specialized architectures like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), excel at identifying complex, nonlinear patterns in high-dimensional data, making them suitable for intricate polymer systems.

Detailed Protocol for DNNs and GNNs

- Architecture Selection:

- For tabular data (e.g., fiber, matrix, processing parameters), use a feedforward DNN. A successful architecture for composite prediction featured four hidden layers (128, 64, 32, 16 neurons) with ReLU activation, 20% dropout for regularization, and the AdamW optimizer [9].

- For data directly derived from molecular structure, use a Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN). A Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) is particularly effective for feature extraction from molecular graphs, as it avoids "node neighborhood explosion" and captures long-range interactions [22].

- Training Configuration:

- For the DNN, use a batch size of 64 and a learning rate of 10â»Â³, determined via hyperparameter optimization [9].

- The loss function is typically Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression tasks.

- Advanced Variants:

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Integrate physical laws (e.g., governed by PDEs) directly into the loss function:

L = L_data + λL_physics + μL_BC. This ensures model predictions adhere to known physics, improving accuracy and data efficiency [24]. - Contrastive Learning (PolyCL): A self-supervised approach for learning robust polymer representations without property labels. It works by pulling together representations of the same polymer under different "augmentations" while pushing apart representations of different polymers [13].

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Integrate physical laws (e.g., governed by PDEs) directly into the loss function:

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated machine learning and experimental workflow for polymer property prediction and validation, from data preparation to model deployment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists essential computational "reagents" and datasets used in machine learning-driven polymer research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML in Polymer Science

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use Case | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit / Mordred Descriptors | Software libraries for calculating quantitative molecular descriptors from chemical structures. | Feature representation for Random Forest and XGBoost models. | [11] |

| Polymer-SMILES | A string-based representation of polymers that marks connection points between monomers with "[*]". | Input for sequence-based models like LSTM and polyBERT. | [13] |

| PoLyInfo Database | A large, publicly available database of polymer properties. | Source of experimental data for training and benchmarking models (e.g., density prediction). | [22] |

| Molecular Graph | Representation of a polymer where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. | Native input structure for Graph Neural Networks (GCNNs). | [22] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic method to explain the output of any ML model. | Interpreting model predictions and identifying impactful functional groups. | [22] |

| MD-Generated Dataset | Data on polymer properties generated via Molecular Dynamics simulations. | Training ML models when experimental data is scarce (e.g., for vitrimers). | [11] |

| Optuna | A hyperparameter optimization framework. | Automating the search for the best model architecture (e.g., DNN layers, neurons). | [9] |

| Tilivapram | Tilivapram, CAS:166741-91-9, MF:C16H15Cl2N3O4, MW:384.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Timcodar | Timcodar, CAS:179033-51-3, MF:C43H45ClN4O6, MW:749.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The selection of feature descriptors to encode a dataset is one of the most critical decisions in polymer informatics, fundamentally shaping a machine learning model's interpretation of training data and its predictive performance [12]. Unlike small molecules, polymeric macromolecules present unique representation challenges due to their sensitivity to properties like molecular weight, degree of polymerization, copolymer structure, branching, and topology [12]. This application note details practical methodologies for engineering effective polymer features using RDKit, molecular descriptors, and fingerprints, framed within the broader context of machine learning for polymer property prediction.

Several established classes of data representations are applicable to polymeric biomaterial machine learning frameworks [12]. The choice of representation involves a critical trade-off between computational efficiency, information content, and applicability to different polymer classes. The table below summarizes the four most popular classes.

Table 1: Popular Classes of Macromolecular Representations for Machine Learning

| Representation Class | Description | Key Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain-Specific Descriptors [12] | Numeric encoding of specific polymer properties (e.g., molecular weight, % cationic monomer, pKa). | High interpretability; grounded in domain knowledge; can incorporate analytical data. | Requires expert curation; may not generalize beyond specific polymer classes or properties. |

| Molecular Fingerprints [12] [25] | Fixed-length bit vectors indicating the presence or absence of specific molecular substructures or patterns. | Fast computation; standardized; suitable for similarity searches and QSAR modeling. | Fixed format limits end-to-end learning; potential for bit collisions; may miss complex features [25]. |

| String Descriptors (e.g., SMILES) [26] [27] | Text-based string representations of the polymer's chemical structure. | Human-readable; compact; compatible with NLP-based models (e.g., Transformers). | A single polymer can have multiple valid SMILES strings; spatial relationships can be ambiguous. |

| Graph Representations [3] | Atoms represented as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph structure. | Naturally captures topological and connectivity information; powerful for deep learning. | Computationally intensive; requires defining initial node/edge features. |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Generation

Protocol 1: Generating RDKit Molecular Objects and SMILES Strings

This protocol outlines the process for loading chemical data and converting it into RDKit molecule objects and SMILES strings, which serve as the foundational step for many subsequent feature generation techniques [26].

Workflow Diagram: From Dataset to Molecular Representation

Detailed Methodology:

- Dataset Loading: Utilize the

load_zinc15function from DeepChem's MoleculeNet to access the ZINC15 database, which contains millions of commercially available chemicals, including potential monomers [26]. - Featurization: Apply the

RawFeaturizerduring the loading process. Settingsmiles=Truefor this featurizer will directly load the data as SMILES strings. The default setting returns RDKit molecule objects, which are powerful data structures for storing and processing chemical parameters [26]. - Data Extraction: Use a utility function to extract the training, validation, and testing datasets from the loaded object. The training dataset is an iterable containing the molecular data [26].

- Molecular Object Creation: Iterate through the training set using the

.itersamples()method. Each iteration returns a sample where the feature matrix (xi) is an RDKit molecule object [26]. - SMILES Conversion: Convert the obtained RDKit molecule object into a canonical SMILES string using RDKit's

Chem.MolToSmiles()function [26].

Protocol 2: Creating Molecular Fingerprints with RDKit

Molecular fingerprints are a cornerstone of chemical informatics. This protocol describes generating the MACCS keys fingerprint, a common substructure-based fingerprint, using RDKit.

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Start with a canonical SMILES string or an RDKit molecule object, obtained via Protocol 1.

- Fingerprint Generation: Use the

rdMolDescriptors.GetMACCSKeysFingerprint()function from RDKit to generate the fingerprint. This function returns a bit vector of length 167, where each bit signifies the presence or absence of a predefined molecular substructure [25]. - Application in ML: The resulting bit vector can be used directly as a feature vector for training classical machine learning models, such as the Random Forest and XGBoost models used for predicting polymer gas permeability [25].

Protocol 3: Utilizing Domain-Specific Analytical Descriptors

For many biomaterial interaction tasks, domain-specific descriptors derived from experimental or simulation data are most effective [12].

Detailed Methodology:

- Descriptor Selection: Select a set of multivariate descriptors relevant to the target property. For example, for predicting gene editing efficiency of polymers, descriptors may include polyplex radius, polymer % cationic monomer (from NMR), molecular weight, pKa, hydrophobicity, and charge density [12].

- Data Compilation: Compile these descriptors through experimental characterization (e.g., NMR, mass spectrometry) or high-throughput physics-based simulations (e.g., coarse-grained molecular dynamics) [12].

- Feature Vector Construction: Assemble the numeric values into a feature vector. This process often relies heavily on domain (a priori) knowledge to ensure the selected features are physically relevant to the problem [12].

- Feature Engineering: Apply transformations such as scaling to improve learning speed and prevent numerical overflow, or use techniques like principal component analysis for information compression [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key software and computational tools required for implementing the feature engineering protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Polymer Feature Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [26] [25] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Core platform for handling chemical data, converting SMILES to mol objects, calculating fingerprints, and generating molecular descriptors. |

| DeepChem [26] | Open-Source Deep Learning Library | Provides high-level functions for loading molecular datasets (e.g., via MoleculeNet) and includes various featurizers for machine learning. |

| ZINC15 Database [26] | Chemical Database | A resource containing millions of commercially available chemical compounds, useful for sourcing monomer structures and properties. |

| Scikit-learn [25] | Open-Source ML Library | Used for data preprocessing, model training, and feature importance analysis (e.g., permutation importance). |

| polyBERT [27] | Chemical Language Model | A BERT-based model trained on polymer SMILES strings to generate machine-learned fingerprints, offering an alternative to handcrafted fingerprints. |

| Tioconazole | Tioconazole | Tioconazole is a broad-spectrum imidazole antifungal for research. It disrupts cell membranes and shows promising anti-TB activity. For Research Use Only. |

| Tipepidine | Tipepidine, CAS:5169-78-8, MF:C15H17NS2, MW:275.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced and Emerging Representation Techniques

Learned Representations: polyBERT and Graph Neural Networks

Moving beyond handcrafted features, learned representations directly generate fingerprints from data.

- Chemical Language Models (e.g., polyBERT): Models like polyBERT treat polymer SMILES (PSMILES) strings as a chemical language [27]. They are pre-trained on millions of hypothetical PSMILES strings in an unsupervised manner to learn the underlying linguistic rules of polymer chemistry. The model's internal state for a given polymer serves as a powerful, machine-crafted fingerprint that can then be mapped to various properties via multitask learning [27].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs represent polymers as graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [3]. These networks learn features by passing messages between nodes, naturally capturing the topological structure of the molecule. Multitask GNNs have been shown to outperform predictions based on conventional handcrafted fingerprints in many cases [3].

Multimodal Fusion: The Uni-Poly Framework

No single representation is optimal for all properties. The Uni-Poly framework integrates multiple data modalities—including SMILES, 2D graphs, 3D geometries, fingerprints, and textual descriptions generated by large language models—into a unified polymer representation [3]. This approach has been demonstrated to outperform all single-modality baselines across various property prediction tasks, as textual descriptions can provide complementary domain knowledge that structural representations alone cannot capture [3].

Logical Relationship of Multimodal Polymer Representation

Application in Predictive Modeling

The ultimate test of feature engineering is performance in predictive tasks. The following table summarizes results from recent studies that applied different representation schemes to predict key polymer properties.

Table 3: Performance of Different Representations on Property Prediction Tasks

| Target Property | Representation Scheme | Model | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Permeability | MACCS Keys Fingerprint | Random Forest / XGBoost | Model fitted, top features identified via SHAP/Permutation. | [25] |

| Multiple Properties (36) | polyBERT Fingerprint | Multitask Deep Neural Network | Outstrips handcrafted fingerprint speed by 2 orders of magnitude while preserving accuracy. | [27] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | Unified Multimodal (Uni-Poly) | Multimodal Framework | R² ~0.9, outperforming all single-modality baselines. | [3] |

| Solubility (Binary) | Molecular Descriptors | Random Forest | 82% accuracy for homopolymers, 92% for copolymers. | [28] |

The rational design of polymers is crucial for advancements in fields ranging from drug delivery to sustainable energy. Traditional experimental methods for evaluating polymer properties are often time-consuming and resource-intensive. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to accelerate this process, with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformer-based models (BERT) establishing themselves as two of the most advanced architectures for polymer property prediction [2]. These models learn directly from structural representations of polymers, thereby uncovering complex structure-property relationships that are difficult to capture with manual descriptors.

GNNs operate directly on the molecular graph of a polymer, where atoms are represented as nodes and chemical bonds as edges [29] [30]. This explicit topological encoding allows GNNs to capture local chemical environments effectively. In parallel, Transformer models, such as those based on the BERT architecture, treat polymer structures as sequences (e.g., using SMILES strings or other line notations) and leverage self-attention mechanisms to learn from vast amounts of unlabeled data [31] [32]. The core of this article details the application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these architectures, providing a practical guide for researchers and scientists in drug development and materials science.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the reported performance of various GNN and Transformer architectures on key polymer property prediction tasks, providing a benchmark for model selection and expectation.

Table 1: Performance of Transformer-based Models on Polymer Property Prediction

| Model Name | Key Architectural Features | Reported Performance (RMSE/MAE/R²) | Properties Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| TransPolymer [31] | RoBERTa architecture, chemically-aware tokenizer, pretrained via MLM | State-of-the-art on 10 benchmarks; specifics not quantified in abstract | Electron affinity, ionization energy, OPV power conversion efficiency, etc. |

| PolyBERT [33] [32] | BERT-like, chemical linguist, multitask learning | Two orders of magnitude faster than manual fingerprints; high accuracy [32] | General polymer properties |

| PolyQT [8] | Hybrid Quantum-Transformer | Outperformed TransPolymer, GNNs, and Random Forests on multiple properties [8] | Glass transition temperature (Tg), Density, etc. |

Table 2: Performance of Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models

| Model Name | Key Architectural Features | Reported Performance (RMSE/MAE/R²) | Properties Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-supervised GNN [34] | Ensemble node-, edge-, & graph-level pre-training | RMSE reduced by 28.39% (electron affinity) and 19.09% (ionization potential) vs. supervised baseline [34] | Electron affinity, Ionization potential |

| PolymerGNN [29] | Multitask GNN, GAT + GraphSAGE layers, separate acid/glycol inputs | R²: 0.8624 (Tg), 0.7067 (IV) with Kernel Ridge Regression baseline [29] | Glass transition temperature (Tg), Inherent Viscosity (IV) |

| Segmented GNN [30] | Message passing based on unsupervised functional group segmentation | Improved predictive accuracy and more chemically interpretable explanations [30] | Molecular properties (Mutagenicity, ESOL) |

Table 3: Performance of Multimodal and Ensemble Models

| Model Name | Key Architectural Features | Reported Performance (RMSE/MAE/R²) | Properties Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uni-Poly [3] | Fusion of SMILES, 2D graphs, 3D geometries, fingerprints, and text | R²: ~0.9 (Tg), 1.1% to 5.1% R² improvement over best baseline [3] | Tg, Thermal decomposition, Density, etc. |

| PolyRecommender [33] | Two-stage: PolyBERT retrieval + Multimodal (MMoE) ranking | Outperformed single-modality baselines [33] | Tg, Tm, Band gap |

| Multi-View Ensemble [35] | Ensemble of Tabular, GNN, 3D, and Language models | Private MAE: 0.082 (9th out of 2,241 teams in OPP challenge) [35] | Tg, Crystallization temperature, Density, etc. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Self-Supervised Pre-training for GNNs

This protocol is adapted from the ensemble self-supervised learning method that significantly reduces data requirements for predicting electronic properties [34].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Polymer Graph Representation: Software to generate graphs incorporating monomer combinations, stochastic chain architecture, and stoichiometry [34].

- GNN Architecture: A tailored GNN capable of processing the aforementioned polymer graphs.

- Pre-training Dataset: A large corpus of unlabeled polymer structures.

2. Procedure 1. Graph Representation: Convert polymer structures into graph representations that capture essential features. 2. Pre-training: Pre-train the GNN using an ensemble of self-supervised tasks: * Node- and Edge-Level Pre-training: Recover masked node or edge attributes. * Graph-Level Pre-training: Learn by contrasting different views of the same graph. 3. Model Transfer: Transfer all layers of the pre-trained GNN to a downstream supervised learning task. 4. Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the model on a small, labeled dataset for the target property (e.g., electron affinity).

3. Workflow Diagram

Protocol 2: Fine-tuning a Transformer Language Model (TransPolymer)

This protocol outlines the procedure for leveraging the TransPolymer framework, a Transformer model designed specifically for polymer sequences [31].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Polymer Tokenizer: A chemically-aware tokenizer that can parse polymer SMILES and additional descriptors (e.g., degree of polymerization).

- Pre-trained TransPolymer Model: A Transformer encoder (e.g., RoBERTa) pre-trained on a large unlabeled polymer dataset (e.g., PI1M) using Masked Language Modeling (MLM).

- Task-Specific Datasets: Curated, labeled datasets for the target properties (e.g., glass transition temperature, electrolyte conductivity).

2. Procedure 1. Sequence Generation: Represent each polymer as a sequence incorporating the SMILES of its repeating units and relevant polymer descriptors. 2. Tokenization: Process the polymer sequences using the chemical-aware tokenizer to convert them into token IDs. 3. Model Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained TransPolymer model on the labeled dataset. It is crucial to fine-tune both the Transformer encoder layers and the task-specific regression/classification head. 4. Data Augmentation (Optional): Apply data augmentation to the polymer sequences during training to improve model robustness and performance.

3. Workflow Diagram

Protocol 3: Implementing a Multimodal Fusion Model (PolyRecommender)

This protocol describes the methodology for a two-stage multimodal system that combines the strengths of language and graph representations [33].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Language Model Embedding: A fine-tuned PolyBERT model for generating language embeddings from polymer SMILES.

- Graph Model Embedding: A trained Graph Neural Network (e.g., D-MPNN) for generating graph embeddings from molecular topology.

- Fusion Architecture: A model for fusing embeddings (e.g., Multi-gate Mixture-of-Experts (MMoE)).

2. Procedure

1. Embedding Generation:

* Generate language embeddings (z_lang) for all polymers in the database using the fine-tuned PolyBERT model.

* Generate graph embeddings (z_graph) for all polymers using the trained GNN.

2. Candidate Retrieval (Stage 1): Given a query polymer, use cosine similarity of its language embedding against the database to retrieve the top 100 candidate polymers.

3. Multimodal Ranking (Stage 2): For the retrieved candidates, fuse their language and graph embeddings using the MMoE fusion strategy.

4. Property Prediction & Ranking: Use the fused multimodal representation to predict target properties and rank the candidates accordingly.

3. Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This section lists essential computational tools and data resources used in the protocols and studies cited above.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Polymer Informatics

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [35] | Software | Open-source cheminformatics used to compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints). |

| PolyInfo Database [33] [8] | Database | A key source of experimental polymer data for training and benchmarking models. |

| D-MPNN [33] | Model | A Graph Neural Network architecture designed for molecular graphs, used to generate structural embeddings. |

| Chemically-Aware Tokenizer [31] | Algorithm | Converts polymer SMILES and descriptors into tokens that a Transformer model can process. |

| Multi-gate Mixture-of-Experts (MMoE) [33] | Model Architecture | A fusion strategy that learns to balance input from different modalities (e.g., language and graph) for different prediction tasks. |

| Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [33] | Technique | A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method for large language models like PolyBERT. |

| Tobramycin | Tobramycin Reagent | |

| Tolfenpyrad | Tolfenpyrad (CAS 129558-76-5)|High Purity | Tolfenpyrad is a pyrazole insecticide for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The integration of GNNs and Transformer models represents a paradigm shift in polymer informatics. As demonstrated by the protocols and performance data, these architectures address critical challenges such as data scarcity through self-supervision and enhance predictive accuracy by capturing complementary chemical information. The emerging trend of multimodal fusion, which combines language and graph representations, consistently outperforms single-modality approaches, offering a more holistic and powerful framework for the discovery and design of next-generation polymers [33] [3] [35].

Polymer informatics has emerged as a critical field, leveraging data-driven approaches to accelerate the discovery and design of novel polymer materials. The immense diversity of the polymer chemical space makes traditional experimental methods time-consuming and resource-intensive [3]. Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful alternative, enabling the prediction of key properties from molecular structures and thus guiding rational material design [36]. However, the success of such ML projects hinges on a systematic and structured methodology. The Cross-Industry Standard Process for Data Mining (CRISP-DM) provides a robust, proven framework for executing data science projects, ensuring they are well-defined, manageable, and aligned with business objectives [37]. This application note details the implementation of an end-to-end pipeline based on the CRISP-DM methodology, tailored specifically for polymer property prediction, providing researchers with a structured protocol for their informatics endeavors.

The CRISP-DM Methodology: A Six-Phase Approach

CRISP-DM is a cyclical process comprising six phases that guide a project from initial business understanding to final deployment. Its structured nature promotes clear communication, manages risks, and improves the efficiency and effectiveness of data science initiatives [37]. The following sections and corresponding workflow diagram delineate each phase within the context of polymer informatics.

CRISP-DM Workflow for Polymer Informatics - The process flow and iterative nature of the six CRISP-DM phases, adapted for polymer property prediction.

Phase 1: Business Understanding

This foundational phase focuses on deeply understanding the project's objectives from a domain perspective. For polymer informatics, this translates to defining the target material properties and their operational constraints.

- Determine Business Objectives: Clearly articulate the material design goal. A generic objective like "find a good polymer" is insufficient. Instead, a specific objective would be: "Design a chemically recyclable alternative to polystyrene (PS) for food containers" [36].

- Assess Situation: Identify available resources, constraints, and risks. This includes available computational resources, data sources, and time limitations.

- Determine Data Mining Goals: Translate business objectives into specific, measurable technical targets. For the PS alternative, this could involve predicting properties to meet the following screening criteria [36]:

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) > 373 K

- Tensile Strength at Break (σb) > 39 MPa

- Young's Modulus (E) > 2 GPa

- Enthalpy of Polymerization (ΔH) between -10 and -20 kJ/mol

- Produce Project Plan: Develop a detailed plan outlining the technologies, tools, and timeline for each subsequent phase [38].

Phase 2: Data Understanding

This phase involves the collection and initial exploration of the data that will be used to achieve the project goals.

- Collect Initial Data: Identify and acquire relevant data. For polymer informatics, key data includes polymer representations (e.g., SMILES strings, BigSMILES) and associated experimental or computational property data from sources like the NeurIPS Open Polymer Prediction 2025 dataset [39] or other curated databases [6].

- Describe Data: Examine the dataset's surface properties, including the number of records, types of features (e.g., structural, thermal, mechanical), and data formats.

- Explore Data: Use data visualization and statistical analysis to uncover initial patterns, trends, and relationships. For instance, one might explore the distribution of Tg values across different polymer families.

- Verify Data Quality: Check for common data issues such as missing values, inconsistencies in units, or outliers that could skew model performance [38].

Phase 3: Data Preparation

Often the most time-consuming phase, data preparation transforms raw data into a high-quality dataset suitable for modeling. It is estimated to consume up to 80% of a project's time [38].

- Select Data: Decide which datasets and attributes are relevant for the specific modeling task.