Mastering Injection Molding Process Parameters: A Scientific Guide for Biomedical Device Development

This guide provides a comprehensive examination of injection molding process parameters, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering Injection Molding Process Parameters: A Scientific Guide for Biomedical Device Development

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive examination of injection molding process parameters, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational science behind key parameters, advanced methodologies for process control, systematic troubleshooting for common defects in medical parts, and rigorous validation frameworks essential for regulatory compliance. By integrating scientific principles with practical application, this article serves as a critical resource for developing robust, repeatable manufacturing processes for biomedical and clinical components.

The Science of Injection Molding: Core Parameters and Material Interactions for Medical Plastics

Injection molding is a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, enabling the mass production of complex plastic parts with precision and efficiency [1]. For researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development where component reliability is paramount, a deep understanding of the injection molding process is crucial. This document frames the critical process parameters—temperature, pressure, speed, and cooling time—within a rigorous, research-oriented context. The process is cyclical, encompassing several key stages: clamping, injection, dwelling (or packing), cooling, and ejection [1]. Each stage requires precise control of parameters to ensure consistent part quality, and mastering these stages is fundamental to successful plastic injection molding [1]. The following sections provide detailed application notes and experimental protocols for defining, optimizing, and controlling these essential variables.

Critical Process Parameters: Definitions and Interrelationships

The quality and consistency of injection-molded parts are governed by a complex, non-linear interplay of several process parameters [2]. According to the fundamental P-V-T (Pressure-Volume-Temperature) relationship, the specific volume of a polymer changes with pressure and temperature, and this final specific volume after cooling directly affects critical product qualities such as dimensional accuracy, weight, and mechanical properties [2]. Therefore, a scientific approach to parameter setting is essential for stabilizing product weight and quality. The filling and packing stages have been identified as having a particularly significant impact on the final product quality [2].

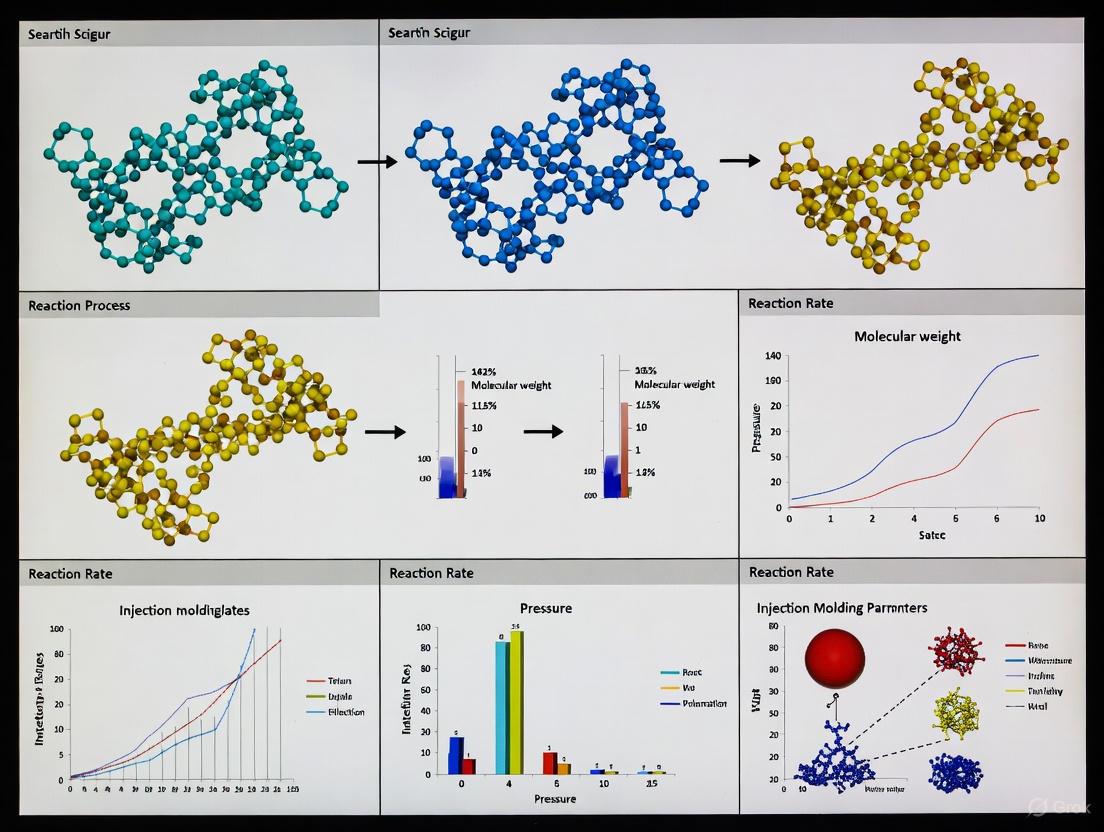

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships and interactions between the four critical process parameters and their collective impact on final product quality.

Quantitative Data and Parameter Ranges

Temperature Parameters for Common Polymers

Temperature control is multifaceted, involving both the molten plastic and the mold itself. Proper control is essential for melting the plastic uniformly and affects the part’s crystallinity, shrinkage, and cycle time [3]. The table below summarizes standard temperature ranges for various polymers, as found in the literature. These values serve as a critical baseline for experimental design.

Table 1: Typical Temperature Parameters for Polymer Processing

| Material | Barrel Temperature (°C) | Mold Temperature (°C) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | 180-250 [4] | 10-60 [5], 40-60 [4] | High fluidity; mold temperature can be kept low to prevent stress cracking [4]. |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 210-240 [4] | 10-80 [5], 40-90 [4] | General-purpose polymer with a broad processing window. |

| ABS | 210-240 [1] [4] | 50-80 [5] [4] | Requires adequate mold temperature for high surface gloss and strength [5]. |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 280-320 [4] | 80-120 [5] [4] | High mold temperature reduces internal stress and tendency for stress cracking [5]. |

| Polyamide 66 (PA66) | 250-310 (for PA6) [4] | 40-120 [5], 40-90 (for PA6) [4] | Crystalline material; high mold temperature facilitates crystallization process [5]. |

| PMMA | 220-270 [4] | 40-90 [5], 30-40 [4] | Amorphous polymer; sensitive to thermal history. |

| POM | 210-230 [4] | 60-120 [5], 60-80 [4] | Crystalline polymer; low mold temperature is favorable for dimensional stability [5]. |

| PE | 180-250 [4] | 50-70 [4] | High fluidity; similar to PP, lower mold temperatures are often used. |

Pressure and Speed Parameter Framework

Injection pressure and speed are highly interactive parameters [6]. Injection pressure must be high enough to overcome the flow resistance of the molten plastic but not so high that it causes excessive stress on the mold or material [1]. The following table outlines the core functions, impacts, and calculation methods for these parameters.

Table 2: Injection Pressure and Speed Parameters

| Parameter | Function & Definition | Impact on Quality | Calculation & Setup Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection Pressure | Overcomes melt viscosity and flow resistance to fill the cavity [1] [6]. | Inadequate pressure causes short shots; excessive pressure causes flash, high residual stress, and damage to the material or mold [1] [6]. | Pi = P * A / Ao where Pi is injection pressure, P is pump pressure, A is the effective area of the injection cylinder, and Ao is the cross-sectional area of the screw [6]. |

| Packing Pressure | Compensates for material shrinkage during cooling after the initial filling stage [1]. | Prevents sink marks and voids; insufficient pressure leads to higher shrinkage and dimensional inaccuracy [1] [2]. | Optimized based on nozzle or cavity pressure profile to stabilize product weight; often a percentage of injection pressure [2]. |

| Injection Speed | The rate at which molten plastic is injected into the mold [3]. | Affects molecular orientation, density, and appearance; too slow can cause flow lines or short shots; too fast can cause jetting or air traps [3] [6]. | Set via multi-stage injection profiling to ensure a constant melt-front velocity and to address specific geometric challenges [6]. |

| Back Pressure | Pressure maintained on the screw during recovery to compact and homogenize the melt [3]. | Ensures consistent melt density and color dispersion; prevents voids. | Typically set as a low percentage of the injection pressure and adjusted to achieve a stable screw recovery time. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Optimization

This section provides detailed methodologies for establishing and optimizing critical process parameters, with a focus on data-driven, research-grade techniques.

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of V/P Switchover and Injection Speed

Objective: To determine the optimal injection speed profile and the precise switchover point from injection velocity control to packing pressure control (V/P) to minimize part weight variation and defects.

Background: The V/P switchover point and injection speed are crucial for ensuring the cavity is properly filled and packed without over-pressurization [6] [2]. An optimized procedure reduces variability in product weight to below 0.1% [2].

Materials and Equipment:

- Injection molding machine

- Nozzle pressure sensor

- Mold with a representative cavity

- Polymer resin (e.g., Polypropylene)

- Data acquisition system

Methodology:

- Initial Setup: Set a constant, medium injection speed and a preliminary, late V/P switchover point. Set packing pressure and time to a low value to isolate the filling phase.

- Injection Speed Optimization:

- Conduct a series of shots, incrementally increasing the injection speed.

- Use the nozzle pressure sensor to record the pressure profile for each shot.

- Analysis: The optimal injection speed is identified at the point where the pressure difference during the injection stage is minimized, and the pressure integral is smallest, indicating stable and efficient filling [2].

- V/P Switchover Optimization:

- Using the optimized injection speed, conduct a series of shots while progressively moving the V/P switchover point to an earlier screw position.

- Analysis: The optimal V/P switchover point corresponds to the screw position just as the cavity is ~95-98% full. This is identified on the nozzle pressure profile as the point immediately before a sharp, exponential rise in pressure occurs, signaling the end of filling [2].

- Validation: Conduct a short production run (30-50 shots) using the optimized parameters. Measure part weight and dimensions. The process is considered optimized when the coefficient of variation in part weight is minimized [2].

Protocol 2: Determination of Minimum Cooling Time

Objective: To establish the minimum required cooling time that ensures sufficient part solidification for ejection without introducing warpage or dimensional instability.

Background: Cooling time can constitute 50-70% of the total cycle time, making it a primary target for optimization [7] [8]. However, insufficient cooling leads to ejection failures and warping.

Materials and Equipment:

- Injection molding machine

- Mold instrumented with thermocouples (if available)

- Polymer resin

- Dimensional measurement tools (e.g., CMM, calipers)

- Timer or cycle monitor

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Set the cooling time to a known, safe value that produces a dimensionally stable part. Record this time and the resulting part dimensions.

- Iterative Reduction:

- Gradually decrease the cooling time in small increments (e.g., 1-2 seconds).

- At each new setting, allow the process to stabilize for 5-10 cycles.

- Eject a part and immediately assess it for:

- Dimensional Stability: Measure critical dimensions after the part has fully cooled to ambient temperature.

- Warpage: Use a flatness gauge or optical comparator to check for distortion.

- Ejectability: Note any sticking, drag marks, or deformation during ejection.

- Endpoint Determination: The minimum cooling time is reached just before the onset of any warpage, significant dimensional deviation from the baseline, or ejectability issues. It is the point where the part is sufficiently rigid to be demolded without distortion [7] [8].

- Design of Experiments (DoE): For a more robust optimization, a DoE can be employed, factoring in mold temperature and packing pressure alongside cooling time, with part dimensions and warpage as responses.

Protocol 3: Evaluation of Mold Temperature on Part Properties

Objective: To quantify the effects of mold temperature on part appearance, crystallinity, shrinkage, and internal stress.

Background: Mold temperature is a primary consideration in mold design and process control, significantly impacting the final product's mechanical, aesthetic, and dimensional properties [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Injection molding machine with mold temperature controller

- Mold

- Polymer resin (e.g., a semi-crystalline material like PP and an amorphous material like PC)

- Gloss meter, polariscope (for stress visualization), and dimensional measurement tools.

Methodology:

- Parameter Setting: Define a matrix of mold temperatures for testing. For example, test the lower, middle, and upper ends of the recommended range for the material (see Table 1).

- Production and Data Collection: For each mold temperature setting, produce a minimum of 10 stabilized parts. For each set, evaluate:

- Appearance: Measure surface gloss with a gloss meter. Visually inspect for flow lines or record clarity for transparent materials [5].

- Dimensional Stability: Measure a critical dimension and calculate the molding shrinkage.

- Internal Stress: For transparent materials like PC or PMMA, use a polariscope to visualize and qualitatively assess the level of residual stress [5].

- Data Analysis: Plot mold temperature against each response variable (gloss, shrinkage, stress). The results will show a correlation between higher mold temperatures and higher surface gloss, more consistent shrinkage for crystalline materials, and reduced internal stress for amorphous materials like PC [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

For researchers aiming to replicate and build upon the protocols outlined, the following tools are essential for data collection and process analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Equipment for Process Parameter Analysis

| Tool / Equipment | Function in Research | Typical Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Pressure Sensor | Measures the pressure history of the melt at the nozzle, which is highly correlated with product weight and filling behavior [2]. | Central to Protocol 1 for optimizing V/P switchover and injection speed. |

| Cavity Pressure Sensor | Directly measures the pressure inside the mold cavity, providing the most direct correlation with part-forming conditions [2]. | Can be used in Protocols 1 & 2 for high-precision optimization and as a quality index. |

| Tie-bar Strain Gauge | Measures the elongation of the machine's tie-bars, which is correlated with the actual clamping force and cavity pressure [2]. | Provides a non-invasive method for monitoring process stability and product weight variation [2]. |

| Data Acquisition System | A high-speed system for collecting sensor data at frequencies of 1000 Hz or more, necessary for capturing transient process events [2]. | Required for all sensor-based protocols to capture accurate pressure and position profiles. |

| Mold Flow Simulation Software | Virtual prototyping tool that predicts melt flow, cooling, and warpage, allowing for preliminary optimization before physical trials [9] [8]. | Used in the design phase to predict filling patterns and identify potential cooling issues. |

| Thermal Imaging Camera | Identifies surface temperature variations and hot spots on the mold, indicating uneven cooling [8]. | Used in Protocol 2 and for cooling system validation to ensure uniform heat removal. |

This document has detailed the critical process parameters in injection molding—temperature, pressure, speed, and cooling time—within a rigorous research framework. The provided application notes, quantitative data tables, and detailed experimental protocols offer a foundation for scientific inquiry and process optimization. As the industry evolves, the integration of advanced sensors, real-time adaptive control systems, and AI-driven data analysis is set to further enhance the precision and repeatability of the injection molding process [9] [2] [10]. For researchers and scientists, mastering these fundamental parameters is the first step toward innovating and ensuring the reliability of molded components, especially in critical applications like drug delivery systems and medical devices.

Injection molding process parameters research is increasingly focused on two distinct classes of materials: bioplastics, driven by sustainability mandates, and high-performance polymers, demanded by advanced engineering applications. Understanding their distinct behaviors under process conditions is critical for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise control over part properties, from medical implants to diagnostic device housings. These materials respond differently to thermal and shear stresses during processing, necessitating tailored parameter strategies to achieve optimal mechanical properties, dimensional stability, and biocompatibility. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for characterizing and optimizing the injection molding of these advanced material systems within a research framework.

Material Properties and Comparative Analysis

Bioplastics are defined as bio-based polymers, biodegradable polymers, or both, but not all bio-based plastics are biodegradable [11]. Common types include Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), a thermoplastic biodegradable polyester produced through the polymerization of bio-derived monomers (e.g., corn, potato, sugarcane), and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), aliphatic bioplastics synthesized naturally by bacteria through the fermentation of lipids and sugar [12]. Their primary challenges during processing include susceptibility to thermal degradation, hydrophilic nature leading to moisture uptake, and often narrower processing windows compared to conventional polymers [12] [11]. The molecular bonds in bioplastics, while similar in structure to petroleum-based plastics, are often more susceptible to breakdown by water, heat, and the sun, which can be an advantage for end-of-life disposal but a challenge during processing [13].

High-performance polymers such as Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) and Polyetherimide (PEI) are essential for applications requiring exceptional strength, thermal resistance, and in the case of medical applications, biocompatibility [14] [15]. These materials are characterized by high melting temperatures, excellent mechanical properties retention at elevated temperatures, and inherent resistance to a wide range of chemicals. Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) is another specialized high-performance material noted for its use in micro-molding applications, allowing for parts as small as 0.03g with tolerances of ±5μm [15].

Quantitative Material Properties Comparison

The table below summarizes key properties of prevalent bioplastics and high-performance polymers, providing a baseline for process parameter selection.

Table 1: Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Bioplastics and High-Performance Polymers

| Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Heat Resistance (HDT, °C) | Impact Resistance | Key Processing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA [12] [11] | Moderate (30-60) | Low (50-60) | Brittle | Low melt strength; sensitive to shear and thermal history. |

| PHA [12] | Varies by type | Moderate (~100) | Varies by type | Narrow processing window; requires precise temperature control. |

| PEEK [15] | High (90-100) | Very High (>250) | Good | Requires high processing temperatures (>350°C); low melt viscosity. |

| PEI [15] | High (105) | Very High (>200) | Good | High melt temperature; hygroscopic - requires thorough drying. |

| LCP [15] | High (120-180) | Very High (>250) | Fair | Highly anisotropic shrinkage; low viscosity at high temperatures. |

Table 2: Characteristic Injection Molding Parameters for Profiled Materials

| Material | Barrel Temperature Profile (°C) | Mold Temperature (°C) | Injection Pressure (MPa) | Drying Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA [12] [11] | 160-180 | 20-40 | 60-80 | 2-4 hrs at 70-80°C |

| PHA [12] | 150-170 | 30-50 | 60-90 | 2-3 hrs at 70-80°C |

| PEEK [15] | 350-400 | 160-180 | 80-120 | 3-5 hrs at 150°C |

| PEI [15] | 340-380 | 140-160 | 80-130 | 4-6 hrs at 150°C |

| LCP [15] | 280-350 | 80-110 | 70-100 | 2-4 hrs at 120-150°C |

Experimental Protocols for Process Parameter Optimization

Protocol: Systematic Optimization of Injection Molding Parameters

Objective: To establish a data-driven methodology for determining the optimal set of injection molding process parameters that minimize cycle time while ensuring part quality compliance.

Background: Traditional parameter adjustment relies heavily on operator experience, leading to inconsistencies and suboptimal energy consumption [16]. This protocol uses an Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) algorithm integrated with machine learning models to systematically navigate the parameter space.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the iterative optimization workflow.

Materials and Equipment:

- Injection molding machine with data acquisition capability.

- Precision measuring instruments (e.g., CMM, optical microscope, tensile tester).

- Computing environment with Python/R and libraries for SVM, XGBoost, and PSO.

Procedure:

- Parameter Vector Definition: Define the process parameter vector (X) to be optimized. Key parameters often include [16]:

- Barrel temperature (

Bt1...Bt8for multiple zones) - Nozzle temperature (

Nt) - Injection pressure (

Ipr) - Injection speed (

Is) - Holding pressure (

Hp) and time (Ht) - Cooling time (

Ct)

- Barrel temperature (

- Constraint Model Development (SVM):

- Collect a dataset of molded parts with known parameter sets (X) and a binary quality label

Q(X)(1=qualified, 0=unqualified) [16]. - Qualify can be defined by measurable attributes (e.g., short shots, flash, warpage, dimensional accuracy).

- Train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to model the complex, non-linear relationship

Q(X). This model acts as a constraint validator in the optimization loop.

- Collect a dataset of molded parts with known parameter sets (X) and a binary quality label

- Fitness Model Development (XGBoost):

- Using the same dataset, record the cycle time

f(X)for each successful run. - Train an eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) regression model to predict cycle time

f(X)based on the input parameters. This model serves as the objective function to be minimized.

- Using the same dataset, record the cycle time

- IPSO Optimization Execution:

- Initialization: Initialize a population of particles, each representing a random set of process parameters within feasible bounds [16].

- Iteration:

a. SVM Validation: For each particle's parameter set, use the pre-trained SVM model to predict if the quality constraint

Q(X)=1is satisfied [16]. b. Fitness Evaluation: For particles that pass the SVM check, use the pre-trained XGBoost model to predict the cycle timef(X), which is the fitness value [16]. c. Particle Update: Using the Improved PSO algorithm, update each particle's velocity and position based on its personal best and the swarm's global best. The "improvement" involves dynamic inertia weight and adaptive acceleration coefficients to prevent premature convergence [16]. - Termination: Repeat the iteration until convergence (e.g., no significant improvement in global best fitness for a set number of iterations) or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

- Validation: Physically run the optimized parameter set on the injection molding machine and verify that the part quality is acceptable and the cycle time reduction is achieved.

Protocol: Characterizing the Effect of Crosslink Density on Mechanical Properties

Objective: To investigate the relationship between the crosslink density of a polymer network (e.g., in elastomers like EPDM or thermosets) and the resulting mechanical properties of the molded part.

Background: Crosslink density is a key factor shaping the mechanical behavior of polymers, defined as the density of chains connecting two infinite parts of the polymer network [17]. It significantly impacts properties like modulus, hysteresis, and hardness. For EPDM, the temperature gradient during vulcanization influences the density and distribution of crosslinks, thereby affecting the final product's performance [18].

Workflow: The experimental and computational workflow for this analysis is outlined below.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer resin (e.g., EPDM with curing agents).

- Injection molding machine with precise temperature control for the barrel and mold.

- Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) or Tensile Tester.

- Molecular Dynamics simulation software (e.g., LAMMPS, Materials Studio) with a validated force field (e.g., COMPASS) [18].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a series of samples by varying the key curing parameters during injection molding, specifically the mold temperature and curing time, while keeping other parameters constant.

- The elevated temperature and pressure in the mold facilitate the crosslinking (vulcanization) reaction [18].

- Computational Analysis (Molecular Dynamics):

- Model Construction: Build an atomistic model of the polymer system (e.g., 10 chains with 500 monomers each for EPDM) in an amorphous cell with periodic boundary conditions [18].

- Crosslinking Simulation: Simulate the crosslinking process using a multi-step methodology that periodically increases the cut-off reaction radius to form crosslinks between chains [18].

- Property Calculation: From the simulated crosslinked network, calculate the crosslink density. Subsequently, use the same model to simulate stress-strain behavior to derive mechanical properties [18].

- Experimental Validation:

- Crosslink Density Measurement: Experimentally, crosslink density can be determined from the equilibrium swelling method or, more precisely, from the rubbery storage modulus (

G') measured by DMA, using the theory of rubber elasticity [17] [18]. - Mechanical Testing: Perform uniaxial tensile tests or DMA on the fabricated samples to obtain stress-strain curves, Young's Modulus, and elongation at break.

- Crosslink Density Measurement: Experimentally, crosslink density can be determined from the equilibrium swelling method or, more precisely, from the rubbery storage modulus (

- Data Correlation:

- Plot experimental mechanical properties (e.g., Tensile Modulus, Hardness) against the calculated crosslink density (from both simulation and experiment).

- A strong positive correlation between crosslink density and modulus/stiffness is expected, as predicted by the Miller-Macosko and Flory-Stockmayer models, though these models often overpredict density due to intramolecular cyclization [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Injection Molding Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) [12] [11] | A model bioplastic for prototyping sustainable packaging and disposable items. Requires careful control of melt temperature and cooling rate to manage crystallinity and brittleness. |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) [12] | A family of bioplastics with tunable properties. Used for studying the effect of microbial strain and carbon source on processability and performance in biomedical applications. |

| Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) [14] [15] | High-performance polymer for demanding R&D in automotive, aerospace, and medical implants. Essential for studies on high-temperature stability, chemical resistance, and sterilization compatibility. |

| Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) [15] | Critical for research into micro-injection molding and miniaturized components for electronics and microfluidics. Used to study highly anisotropic shrinkage and fiber orientation. |

| Thermoplastic Starch (TPS) [12] | A bioplastic made by plasticizing starch (e.g., with glycerol). Used in research on modifying native biomaterials for injection molding and studying the impact of plasticizer type/content. |

| Crosslinking Agents (e.g., Peroxides) | Used to induce chemical crosslinks in elastomers (e.g., EPDM) and some thermosets within the mold. Key for studying the kinetics of vulcanization and its effect on network formation and final properties [18]. |

| COMPASS Force Field [18] | A parameterized interatomic potential for molecular dynamics simulations. It is used to model and predict the behavior of complex amorphous polymer systems during and after the crosslinking process. |

Application Notes for Researchers

Processing Bioplastics

- Drying is Critical: Bioplastics like PLA are highly hygroscopic. Inadequate drying leads to molecular weight degradation via hydrolysis during processing, severely compromising mechanical properties [12] [11]. Strict adherence to drying protocols is non-negotiable.

- Managing Thermal Stability: Bioplastics often have a narrow window between the melting temperature and the decomposition temperature. Minimizing residence time in the barrel and avoiding excessive temperatures are essential to prevent degradation [11]. Using thermal stabilizers specific to the bioplastic is a common research approach.

- Crystallization Control: The properties of semi-crystalline bioplastics (like PLA) are heavily influenced by their degree of crystallinity, which is controlled by melt temperature, mold temperature, and cooling rate. A heated mold is often required to achieve sufficient crystallinity and avoid premature embrittlement.

Processing High-Performance Polymers

- High-Temperature Processing: Materials like PEEK and PEI require processing temperatures significantly above 300°C [15]. This necessitates specialized equipment with high-temperature barrels, nozzles, and thermal stability in the screw and barrel materials to prevent degradation.

- Crystallization Management: Similar to some bioplastics, the mechanical properties of PEEK are tied to its crystallinity. Achieving an optimal crystalline morphology requires precise control over melt temperature and, crucially, a high mold temperature (often >160°C) to control the cooling rate [15].

- Handling Low Melt Viscosity: Some polymers like LCP have very low melt viscosity, which, while beneficial for filling thin walls, can lead to flashing in molds with even minimal wear or insufficient clamping force. Research-grade molds must be built to high precision standards [15].

Injection molding is a complex manufacturing process where mastering the physics of mold filling is essential for producing high-quality parts. At the heart of this process lies fluid dynamics—the study of fluids in motion—which governs how molten polymers flow into mold cavities [19]. The behavior of polymer melts during injection is characterized by their rheological properties, primarily viscosity and shear sensitivity, which directly impact filling patterns, part dimensions, mechanical properties, and surface finish.

Understanding these properties is particularly crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who require precision and consistency in medical components, where minute variations can affect device performance and regulatory compliance. The flow dynamics of molten plastics differ significantly from Newtonian fluids like water or oil; instead, they exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, meaning their viscosity changes under different flow conditions [19]. This application note examines the fundamental principles of viscosity, shear rate, and flow dynamics within the context of injection molding process parameter research, providing structured experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for advanced manufacturing research.

Theoretical Foundations

Viscosity Fundamentals

Viscosity is defined as a fluid's internal resistance to flow [19] [20]. In practical terms, it represents the amount of friction that exists within the material as it flows. A higher viscosity indicates greater resistance, requiring more pressure to inject the material into a mold [20]. Molten polymers used in injection molding are typically pseudo-plastic non-Newtonian fluids, meaning their viscosity decreases as the flow rate (shear rate) increases [21].

This behavior can be visualized by comparing a simple chain necklace to one with large beads. The plain chain (low viscosity) flows easily down a drain, while the beaded necklace (high viscosity) encounters more resistance [20]. In production environments, viscosity variations between material lots or due to polymer degradation can significantly impact process stability and part quality, often leading to defects such as short shots, sink marks, or flash [20].

Shear Rate Physics

Shear rate is defined as the rate of change in velocity at which adjacent layers of fluid move relative to each other, typically measured in inverse seconds (s⁻¹) [22]. Mathematically, it is expressed as the velocity gradient (ΔV) divided by the distance between flow layers (Δy) [23]. In injection molding, shear rates can reach extremely high values between 1,000 to 10,000 s⁻¹, and even up to 60,000 s⁻¹ in specialized testing, due to the rapid flow of material through narrow channels and gates [23] [21].

The relationship between shear rate and viscosity is fundamental to injection molding processing. As shear rate increases, the entangled polymer chains align in the direction of flow, reducing internal friction and consequently lowering viscosity—a phenomenon known as shear thinning [19]. This principle is leveraged in process optimization to enhance mold filling without excessive pressure requirements.

Table 1: Shear Rate Ranges in Different Processing Environments

| Processing Environment | Typical Shear Rate Range (s⁻¹) | Contextual Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mud Tank (Drilling) | ~0 | Almost zero shear [23] |

| Annular Flow | 0–100 | Low shear environment [23] |

| Extrusion Processes | 100–500 | Moderate shear [23] |

| Drillpipe Interior | ~1,000 | High shear [23] |

| Injection Molding | 1,000–10,000 | Very high shear [23] |

| Bit Nozzles (Drilling) | Up to 100,000 | Extreme shear [23] |

| Rheometer Testing | Up to 60,000 | Experimental high shear [21] |

Interplay of Processing Parameters

The viscosity of molten polymers during injection molding is simultaneously influenced by temperature, pressure, and shear rate, with temperature and shear rate being the most dominant factors [23]. This complex interaction creates a dynamic flow environment where viscosity constantly changes as the material flows through different geometrical features of the mold and undergoes cooling [19].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships and workflow for analyzing these key parameters in an injection molding process:

Quantitative Analysis and Data Presentation

Viscosity Measurement Methods

Researchers can employ several methodologies to quantify polymer viscosity under processing conditions. The melt flow index (MFI) test represents one of the most common approaches, measuring how much plastic is extruded through a small orifice under specified temperature and load conditions over a fixed time period [20]. Materials with lower viscosities produce higher MFI values—for example, a "16 melt" material flows more easily than a "12 melt" material [20].

For more sophisticated analysis, capillary rheometry provides detailed viscosity profiles across a range of shear rates, though this method may involve extended thermal residence times that potentially affect material stability [21]. The injection molding rheometer (IMR) addresses this limitation by utilizing an actual injection molding machine to prepare samples with thermal and shear histories nearly identical to production conditions, enabling viscosity measurement at shear rates up to 60,000 s⁻¹ [21].

An advanced alternative involves viscosity identification via temperature measurement using specialized instrumentation like the Thermo-Rheo Annular Cell (TRAC). This method correlates temperature variations caused by viscous dissipation with melt viscosity, offering potential for in-line monitoring [24].

Experimental Viscosity Data

Comprehensive material characterization establishes baseline expectations for viscosity behavior under different processing conditions. The following table presents representative viscosity values for polyethylene across varying shear rates, illustrating the dramatic shear-thinning effect typical of injection molding polymers:

Table 2: Polyethylene Viscosity versus Shear Rate at Constant Temperature

| Shear Rate (s⁻¹) | Viscosity (Pa·s) | Process Context |

|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 40,000 | Very slow flow |

| 1 | 10,000 | Low shear processing |

| 10 | 4,000 | Moderate shear |

| 100 | 1,000 | High shear |

| 1,000 | 500 | Injection molding range |

| 10,000 | 100 | High-speed injection molding |

Data adapted from [23]

For process monitoring, researchers can calculate effective viscosity using machine parameters during injection molding operations. The simplified formula Effective Viscosity = Fill Time (s) × Pressure at Transfer (PSIp) provides a practical metric for tracking viscosity shifts between cycles and material lots [19] [20]. This calculated value represents the "work" required to flow the material and serves as a valuable indicator of process stability and material consistency.

Experimental Protocols

In-Line Viscosity Monitoring Using Annular Measurement Cell

Purpose: To implement real-time viscosity monitoring during injection molding cycles using temperature and pressure measurements for detection of material variations and degradation.

Equipment and Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Thermo-Rheo Annular Cell (TRAC) | Measures temperature and pressure variations during polymer flow; central axis thermocouples detect viscous dissipation [24]. |

| Type K Thermocouples | Temperature sensing at multiple radial positions with fast response time [24]. |

| Pressure Sensors (e.g., KISTLER 6159A) | Measure pressure drop across the flow path for complementary rheological data [24]. |

| Polymer Materials (PP, PS) | Test substrates with known rheological properties for method validation [24]. |

| Injection Molding Machine | Standard production equipment with programmable plasticization and injection settings [24]. |

Procedure:

- Instrument Configuration: Install the TRAC device inline with the injection molding machine nozzle or barrel. Connect thermocouples (T₁-T₄ on central axis; T₅-T₈ on outer wall) and pressure sensors (P₁, P₂) to data acquisition system [24].

- Process Parameter Setup: Program the injection molding machine for successive air shot cycles with the following parameters:

- Plasticization at 60 rpm screw rotation speed

- Back pressure: 2 bar

- 10-second pause before each air shot

- Injection at 10 mm/s screw translation speed over 112 mm travel

- Setpoint temperature: 195°C [24]

- Baseline Data Collection: Conduct multiple air shot cycles with pure polymer resin (e.g., polypropylene) to establish temperature and pressure baseline curves.

- Material Variation Testing: Introduce controlled material variations (e.g., polystyrene impurity in polypropylene) while maintaining identical process parameters.

- Data Acquisition: Record temperature measurements from central axis thermocouples during each air shot. Note characteristic temperature curve shapes and magnitudes.

- Viscosity Identification: Apply inverse characterization method based on viscous dissipation phenomenon. Use temperature data with appropriate flow models to calculate viscosity values [24].

- Data Analysis: Correlate temperature curve variations with material changes. Statistically analyze the sensitivity of the method for detecting specific viscosity shifts.

Interpretation: Temperature increases measured on the central axis of the TRAC device indicate higher viscous dissipation, which correlates directly with increased melt viscosity. A variation of just 1-2°C in the temperature curve can signify meaningful changes in polymer composition or degradation state [24].

Process Optimization Using Improved Particle Swarm Algorithm

Purpose: To systematically identify optimal injection molding parameters that minimize cycle time while maintaining product quality standards using computational intelligence methods.

Equipment and Reagents:

- Injection molding machine with programmable controller

- Plastic material (granulate form)

- Quality measurement instruments (dimensional, visual, mechanical)

- Computing system with MATLAB/Python for algorithm implementation

- Data acquisition system for process parameter logging

Procedure:

- Parameter Selection: Identify critical process parameters for optimization: barrel temperature (Bt₁...Bt₈), nozzle temperature (Nt), injection pressure (Ipr), injection speed (Is), holding pressure (Hp), holding time (Ht), cooling time (Ct), and switch-over position (Sop) [16].

- Experimental Design: Conduct initial design of experiments (DOE) to generate training data covering parameter space. Record both process parameters and resulting quality metrics for each trial.

- Model Development:

- Train Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification model to predict product quality (qualified/unqualified) from process parameters [16].

- Develop XGBoost regression model to predict injection cycle time from process parameters [16].

- Validate model performance (target: accuracy >0.92 for SVM, R² >0.93 for XGBoost) [16].

- Algorithm Implementation:

- Optimization Execution: Run IPSO algorithm to identify parameter sets that minimize cycle time while satisfying quality constraints.

- Verification: Conduct physical verification trials using optimized parameters and compare results with predictions.

Interpretation: The IPSO algorithm systematically explores the parameter space while maintaining quality constraints, typically achieving cycle time reductions of approximately 9.4% while ensuring product qualification [16]. This methodology provides a data-driven approach to process optimization that transcends experiential methods.

The following workflow diagrams the complete experimental optimization process from parameter identification through verification:

Research Implications and Future Directions

The physics of mold filling presents ongoing research challenges with significant implications for advanced manufacturing. Current investigations focus on real-time viscosity monitoring through indirect methods like temperature and pressure analysis, potentially enabling closed-loop process control without expensive rheological instrumentation [24]. The integration of machine learning algorithms with traditional process optimization represents another promising direction, allowing more efficient navigation of complex parameter spaces while accommodating multiple constraints [16].

For the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, these advancements hold particular significance. The ability to precisely monitor and control viscosity and flow dynamics during injection molding of drug delivery components or implantable devices ensures consistent wall thicknesses, dimensional stability, and mechanical properties—critical factors in regulatory compliance and patient safety. Furthermore, as material science advances with developing biodegradable polymers and advanced composites, understanding their unique rheological behavior becomes essential for successful process implementation [9].

Future research will likely focus on enhanced sensor technologies with reduced intrusiveness, improved digital twin simulations that accurately predict flow behavior under varying conditions, and standardized methodologies for correlating rheological measurements with final part properties across different material systems.

Injection molding is a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, essential for producing components across industries from medical devices to automotive parts. A thorough understanding of the thermodynamic principles governing polymer cooling and solidification is paramount for achieving superior dimensional accuracy. This application note details the intrinsic relationship between crystallization behavior during cooling and the resultant shrinkage and dimensional changes in molded parts. Framed within broader research on injection molding process parameters, this document provides researchers with both the theoretical foundation and practical experimental protocols to precisely control these critical phenomena, thereby minimizing defects and ensuring part quality.

Theoretical Foundation: Thermodynamics of Polymer Cooling

Shrinkage in injection-molded parts is an inevitable consequence of the thermodynamic behavior of polymers as they transition from a viscous melt to a solid state [25]. The fundamental driver is thermal contraction; as the polymer cools, the reduction in molecular kinetic energy causes the chains to pack more closely together. For semi-crystalline materials, this effect is compounded by the process of crystallization, where molecular chains align into ordered, densely packed regions [26] [25].

- Molecular Orientation and Shrinkage Anisotropy: During injection, polymer chains are subjected to shear and extensional forces, causing them to uncoil and align in the direction of flow. Upon flow cessation, amorphous chains relax towards a random coil configuration, pulling the material inwards and resulting in higher shrinkage parallel to the flow direction [25]. In contrast, semi-crystalline materials maintain their flow-induced orientation during cooling and recrystallize. This results in the formation of crystalline regions that occupy a smaller specific volume, leading to significantly greater shrinkage in the direction perpendicular to flow [25] [27].

- The Role of Fiber Reinforcement: The introduction of fibers, such as glass fibers, drastically alters this shrinkage behavior. The fibers themselves are dimensionally stable with temperature changes and act to restrain shrinkage in the direction of their orientation. This leads to anisotropic shrinkage, where shrinkage is reduced in the parallel direction and can be increased in the transverse direction [25] [27]. The final fiber orientation, which is a function of mold geometry, gate location, and processing parameters, is therefore a critical determinant of the part's final dimensions [27].

Key Factors Influencing Crystallization and Shrinkage

The following factors have been identified as critical in controlling the crystallization behavior and resultant shrinkage of injection-molded components.

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Crystallization and Shrinkage

| Factor | Impact on Crystallization & Shrinkage | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Material Type | Semi-crystalline polymers (e.g., Polypropylene, HDPE) exhibit higher shrinkage than amorphous polymers (e.g., ABS, Polycarbonate) [25]. | Crystallization increases density and volumetric contraction. Amorphous polymers lack long-range order, leading to less shrinkage [25]. |

| Fiber Fillers | Significantly reduces shrinkage in the direction of fiber orientation; can increase transverse shrinkage [25] [27]. | Fibers provide dimensional stability along their length, restricting polymer contraction [27]. |

| Wall Thickness | Thicker walls cool slower, allowing more time for crystal growth, leading to higher crystallinity and shrinkage [25]. | Non-uniform wall thickness creates differential cooling rates and crystallinity, causing uneven shrinkage and warpage [25]. |

| Cooling Time | A primary factor, accounting for 28.78% of influence on warpage in PET preforms [28]. Insufficient cooling leads to ejection defects; excessive cooling reduces crystallinity [26]. | Governs the time available for molecular reorganization and crystal formation before part ejection [26] [25]. |

| Packing Pressure | Increased pressure compresses melt, allowing material compensation into the cavity to counteract shrinkage [26] [25]. | Higher pressure packs more molecules into the mold cavity, directly reducing volumetric shrinkage [26]. |

| Melt Temperature | Higher temperatures increase the cooling range, potentially leading to greater thermal contraction, but can also influence crystallization kinetics [26]. | Affects polymer viscosity and the relaxation time of molecular chains, impacting orientation and final crystallinity [26] [25]. |

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Experimental designs, particularly Taguchi L27 orthogonal arrays and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), are routinely employed to quantify the effect of process parameters on dimensional outcomes.

Table 2: Quantitative Shrinkage and Warpage Data from Experimental Studies

| Study Focus | Material | Key Parameters | Optimized Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight & Warpage Reduction | 45g PET Preform | Cooling time, cycle time, melting temp., injection time, molding temp. | Warpage reduced by 4.75% (0.1905 mm); Weight reduced by 2.05% (42.37 g). Cooling time was most significant factor (28.78%) [28]. | [28] |

| Thin-Wall Shrinkage Analysis | Short Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer | Packing pressure, melt temperature, injection speed, mold temperature | Shrinkage is highly anisotropic. In-flow shrinkage is primarily controlled by packing pressure, while cross-flow shrinkage is dominated by mold temperature [27]. | [27] |

| Multi-Criteria Optimization | Recycled Polypropylene | Part thickness, flow leader thickness, packing pressure/pressure, etc. | Methodology demonstrated feasibility of a 27% weight reduction by combining non-standard process parameters with a non-uniform thickness distribution [29]. | [29] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Shrinkage in Thin-Wall Molded Parts

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for investigating the impact of key process parameters on the shrinkage of fiber-reinforced, thin-wall plastic parts, based on established experimental designs [27].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for Shrinkage Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Injection Molding Machine | For part production. A Sumitomo 180-ton machine or equivalent is recommended [26]. |

| Test Mold | A mold producing a square plaque (e.g., 10 mm side, 350 μm thickness) with a single gate to control flow direction [27]. |

| Material | Short glass fiber-reinforced thermoplastic (e.g., Polypropylene for automotive applications) [26] [27]. |

| Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) | For high-precision dimensional analysis (e.g., Werth Video-Check IP 400) [27]. |

| Micro Computed Tomography (μ-CT) | For non-destructive, 3D analysis of internal fiber orientation and distribution [27]. |

Procedure

Step 1: Experimental Design

- Utilize a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, such as a Taguchi L27 orthogonal array [28].

- Select the following as control factors and assign levels:

- The response variables are:

- Linear shrinkage parallel to the melt flow direction.

- Linear shrinkage perpendicular to the melt flow direction.

- Fiber orientation tensor (from μ-CT).

Step 2: Part Production and Conditioning

- Produce a minimum of three replicates for each run in the experimental plan.

- Condition all molded parts at room temperature for 48 hours before measurement to allow for stress relaxation and dimensional stabilization [27].

Step 3: Dimensional Measurement

- Using the CMM, measure the dimensions of the molded plaque.

- Calculate linear shrinkage (%) in both flow and transverse directions using Fischer's definition: Shrinkage = [(Mold Dimension at Room Temp - Part Dimension at Room Temp) / Mold Dimension at Room Temp] * 100 [27].

Step 4: Fiber Orientation Analysis

- Perform μ-CT scanning on representative samples from key experimental runs.

- Reconstruct 3D models and use analysis software to calculate the fiber orientation tensor (e.g., the main component,

a₁₁), which quantifies the degree of alignment in the flow direction [27].

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the shrinkage and orientation data to determine the statistical significance of each process parameter and their interactions [28] [27].

- Identify the optimal parameter settings that minimize anisotropic shrinkage and ensure dimensional accuracy.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the experimental protocol.

Advanced Predictive Methodologies

Moving beyond traditional trial-and-error, advanced simulation and machine learning techniques are now critical for predicting and controlling shrinkage.

6.1 Simulation-Assisted Design Software tools like Autodesk Moldflow allow engineers to perform mold flow analysis and visualize expected shrinkage based on the part's material, design, and processing conditions [25]. This enables virtual optimization before physical tooling is created, saving time and cost. The use of digital twins—virtual replicas of the physical process—further allows for real-time monitoring and analysis [9].

6.2 Machine Learning for Multi-Output Prediction Recent research demonstrates the superiority of Back Propagation Neural Networks (BPNN) for correlating a wide set of input parameters (e.g., geometry and process settings) with multiple quality outputs (e.g., dimensions, weight, volumetric shrinkage) simultaneously [29]. These models can predict complex, non-linear behavior and compensatory effects between parameters, accelerating the design optimization process by up to 1000 times compared to running sequential simulations [29].

Controlling the thermodynamics of cooling and crystallization is fundamental to mastering dimensional accuracy in injection molding. The interplay between material composition, part geometry, and process parameters dictates the final shrinkage behavior, often in an anisotropic manner. By employing structured experimental protocols, such as the detailed DoE for thin-wall parts, and leveraging advanced predictive tools like BPNN, researchers can systematically identify optimal process windows. This scientific approach moves the industry from reactive problem-solving to proactive, precision manufacturing, ensuring that high-quality, dimensionally stable parts can be produced efficiently and reliably.

Injection molding is a highly complex, non-linear manufacturing process where final product quality is governed by the intricate interplay of numerous process variables [30]. The fundamental challenge for researchers and process scientists lies in this systemic interdependence: adjusting a single parameter inevitably creates cascading effects throughout the entire process, influencing part quality, dimensional stability, mechanical properties, and production efficiency [31] [32]. The process can be conceptualized through the P-V-T (Pressure-Volume-Temperature) relationship, a fundamental thermodynamic principle stating that the specific volume of a polymer is dependent on both pressure and temperature [30]. This relationship is the scientific bedrock explaining why changes to thermal parameters (e.g., melt and mold temperature) directly influence pressure requirements and, consequently, final part dimensions and weight [30]. Mastering these interactions is not merely an empirical exercise but requires a scientific, data-driven methodology to move from a traditional trial-and-error approach to a predictable, controlled manufacturing process [26] [32].

Foundational Concepts of Parameter Interaction

The interdependence of injection molding parameters can be analyzed through their collective impact on three core physical phenomena: polymer rheology, heat transfer, and thermodynamic state changes.

- Polymer Rheology: The flow behavior of a molten polymer is influenced by its viscosity, which is simultaneously affected by temperature, pressure, and shear rate. For instance, injection speed directly determines the shear rate, which can cause viscous heating, thereby reducing the melt viscosity and altering the filling pattern [31]. This means a change in speed cannot be evaluated without considering the concurrent melt temperature.

- Heat Transfer: The entire cycle is a continuous heat removal process. The mold temperature sets the initial boundary condition for cooling, directly affecting the cooling rate, which in turn dictates the required cooling time [31]. An increase in mold temperature can improve surface finish and crystallinity but may necessitate a longer cooling time to ensure proper solidification before ejection, thus impacting the overall cycle time [3] [31].

- Thermodynamic State Changes (P-V-T): As the polymer transitions from a melt to a solid, its specific volume changes. The packing pressure is applied to compensate for volumetric shrinkage by forcing more material into the cavity after filling [30]. The effectiveness of this packing phase, however, is contingent upon the melt temperature; if the melt is too cool, the gate will solidify prematurely, making the application of packing pressure futile [31].

Quantitative Analysis of Parameter Interactions

The following tables summarize the primary and secondary effects of adjusting key process parameters, based on experimental and industry research.

Table 1: Primary and Secondary Effects of Thermal Parameter Adjustments

| Parameter | Primary Effect | Key Interdependencies & Secondary Effects |

|---|---|---|

Melt Temperature (T_m) |

Governs polymer viscosity and flowability [3] [31]. | ↑ T_m → ↓ Viscosity → Can allow for ↓ Injection Pressure [31]. ↑ T_m → ↑ Cooling load & potential degradation → Requires optimized Cooling Time [31] [32]. |

Mold Temperature (T_w) |

Controls cooling rate and surface finish [3] [31]. | ↑ T_w → ↓ Cooling rate → Prevents premature freeze-off, improving Packing Pressure efficacy [31]. ↑ T_w → ↑ Cycle time → Impacts production efficiency [3]. |

Cooling Time (t_cool) |

Determines part solidification before ejection [3]. | ↑ t_cool → Ensures dimensional stability but ↓ throughput [31]. Inadequate t_cool → Ejection of soft parts → Causes warpage [31]. |

Table 2: Primary and Secondary Effects of Pressure and Speed Adjustments

| Parameter | Primary Effect | Key Interdependencies & Secondary Effects |

|---|---|---|

Injection Speed (V_inj) |

Controls fill pattern and shear heating [31]. | ↑ V_inj → ↑ Shear heating → ↓ Viscosity, can help fill thin sections [31]. Excessive V_inj → Air entrapment → Burn marks [31]. Directly impacts weld line strength [31]. |

Packing Pressure (P_pack) |

Compensates for volumetric shrinkage [30]. | ↑ P_pack → ↑ Part density & weight, minimizes sink marks and voids [31]. Excessive P_pack → ↑ Residual stress → Warpage after ejection [31]. Effectiveness is limited by gate seal time, a function of Cooling [31]. |

| Holding Pressure | Maintains pressure after gate freeze to control shrinkage [31]. | Works in sequence after packing. Prevents backflow and maintains dimensional stability as the part cools. Insufficient holding → Dimensional inaccuracy [31]. |

Table 3: Multi-Parameter Optimization for Conflicting Quality Objectives [33] This table demonstrates the trade-offs required when optimizing for multiple, competing quality targets.

| Optimal Parameter Set | Volumetric Shrinkage | Surface Roughness | Implied Parameter Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1: Minimize Shrinkage | 1.9314 mm³ (Min) | 0.55956 µm (Max) | High Packing Pressure, potentially lower Mold Temp [33]. |

| Set 2: Minimize Roughness | 3.9286 mm³ (Max) | 0.20557 µm (Min) | High Mold Temperature, potentially lower Packing Pressure [33]. |

| Set 3: Compromise | 2.2348 mm³ | 0.28246 µm | Balanced settings of Packing Pressure, Mold Temp, and Melt Temp [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Parameter Interdependence

Protocol 1: Developing a Process Window for a New Material/Mold Combination

This protocol provides a systematic, industrially-relevant method to define the operational boundaries (process window) for a stable process [26].

1. Identify and Tier Key Variables:

- Primary Control Variables: Mold Temperature (T_w), Melt Temperature (T_m), Packing Pressure (P_pack). These form the axes of the process window [26].

- Secondary Control Variables: Injection Screw Speed, Packing Time (t_pack), Cooling Time (t_cool). These are delimited and then held constant during primary variable testing [26].

- Tertiary Control Variables: Shot Size, Clamping Force. These are determined by part volume and machine capability and held constant [26].

2. Define Performance Measures (PM): - Establish quantitative criteria for "acceptable" parts. Common PMs include: absence of defects (short shots, flash, sink marks), critical dimensions, weight, and mechanical properties [26].

3. Delimit Secondary Variables:

- Conduct a series of experiments (e.g., using Design of Experiments, DOE) to find the robust setting for each secondary variable.

- Example for Packing Time: Inject a short shot and gradually increase packing time until part weight stabilizes, indicating the gate has frozen. Set t_pack just beyond this point [31].

4. Construct the Process Window:

- Using the fixed secondary and tertiary variables, experimentally map the boundaries of the primary variables.

- Methodology: For a fixed T_m, vary T_w and P_pack to find the combination that produces acceptable parts. The process window is the envelope of T_w and P_pack values that yield parts meeting all PMs. The center of this window offers the most robust setting, buffering against normal process variations [26].

5. Verification and Documentation: - Run a confirmation trial at the center-point of the process window. - Document all parameters and resulting part quality data for future reference and as a new case in a Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) system [34].

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Optimization for Minimizing Shrinkage and Surface Roughness

This protocol employs advanced statistical and optimization techniques to find the optimal parameter set for competing objectives [33].

1. Experimental Design and Data Collection: - Select Input Parameters: Choose the seven key parameters with the most impact: packing pressure, mold temperature, cooling time, injection speed, injection pressure, melt temperature, and packing time [33]. - Generate Test Matrix: Use a structured design like Central Composite Design (CCD) to efficiently define the combination of parameter values for experimental trials [33]. - Conduct Experiments & Measure Outputs: For each parameter combination, produce parts and measure the two quality objectives: Volumetric Shrinkage and Surface Roughness [33].

2. Surrogate Model Construction: - Use the experimental data to build mathematical models (surrogates) that predict shrinkage and roughness as a function of the seven input parameters. The Kriging technique is well-suited for this purpose [33].

3. Formulate and Solve the Multi-Objective Optimization: - The optimization problem is defined as: Minimize [Shrinkage(Model), Roughness(Model)]. - This is solved using a pattern search algorithm, which generates a set of optimal solutions known as a Pareto front [33].

4. Pareto Front Analysis: - The Pareto front visually illustrates the trade-off between the two objectives. Each point on the front represents a parameter set where one objective cannot be improved without worsening the other. - Engineers can select the parameter set that offers the best compromise for a specific application, as demonstrated in Table 3 [33].

Visualizing Parameter Interactions and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, map the complex logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this article.

Diagram 1: Parameter Interaction Pathways. This map illustrates how adjustments to one primary parameter (yellow) propagate through intermediate material properties (green) to affect final part qualities (red).

Diagram 2: Multi-Objective Optimization Workflow. This chart outlines the systematic protocol for optimizing parameters for conflicting quality targets, from experimental design to final parameter selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Nozzle Pressure Sensor | Directly measures hydraulic pressure in the nozzle. The pressure profile (peak pressure, integral) serves as a key quality index for building surrogate models and adaptive control systems [30]. |

| Tie-bar Strain Gauge | A non-invasive sensor that measures clamping force elongation. The clamping force difference value is highly correlated with product weight, enabling real-time monitoring and control [30]. |

| Cavity Pressure Sensor | Installed within the mold cavity to provide the most direct measurement of the pressure the polymer experiences. Used to define peak cavity pressure and pressure integral as quality indices [30]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures the thermal properties of polymers, including crystallinity and melting point. Critical for understanding how process parameters affect material structure [26]. |

| High-Sampling-Rate Controller | Enables precise control of servo-hydraulic systems. A sampling frequency of ≥1000 Hz is necessary for accurate screw position control during V/P switchover and rapid adaptive adjustments [30]. |

| Digital Twin (Moldflow Simulation) | CAE software (e.g., Moldflow, Moldex3D) used to simulate the molding process. Allows for virtual DOE and optimization, predicting defects like warpage and shrinkage before physical trials [34] [35] [32]. |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) Software | Statistical software used to create efficient experimental matrices (e.g., Taguchi, Central Composite Design) and perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to identify significant parameters [33] [35]. |

| Polypropylene (PP) & Polyethylene (HDPE) | Common semicrystalline and commodity polymers, respectively. Their sensitivity to process conditions makes them ideal model materials for fundamental process studies [26] [33]. |

Advanced Process Control: Implementing AI, IoT, and Scientific Molding for Precision Manufacturing

Scientific Molding represents a paradigm shift from traditional, experience-based injection molding to a data-driven methodology that systematically controls, documents, and optimizes process parameters. This approach decouples the injection molding cycle into distinct, independently controlled phases to minimize process variation and ensure repeatability. By leveraging principles of material science, design of experiments (DOE), and real-time process monitoring, Scientific Molding provides a robust framework for achieving superior part quality, reducing scrap, and enhancing production efficiency. This document outlines the core principles, quantitative parameter guidance, and detailed experimental protocols essential for researchers developing robust and transferable injection molding processes.

Core Principles of Scientific Molding

Scientific Molding is founded on several key principles that differentiate it from traditional, trial-and-error methods.

Decoupled Molding: This foundational concept separates the injection molding process into three distinct stages: First Stage Filling (performed under controlled velocity to 95-99% of cavity volume), Second Stage Packing (conducted under controlled pressure to compensate for material shrinkage), and Holding/Cooling (where the part solidifies and the machine recovers) [36] [37]. This separation allows for precise, independent control of each phase, isolating variables and reducing variations that cause defects [37].

Data-Driven Process Control: The methodology relies on comprehensive data collection from sensors and monitoring systems that track parameters such as temperature, pressure, and flow rate in real-time [37] [38]. This data is critical for establishing cause-and-effect relationships between process parameters and part quality, enabling evidence-based process optimization and troubleshooting [36] [37].

Machine-Independent Process Development: A core objective is to establish a process based on the behavior of the plastic material within the mold, rather than on specific machine settings [36] [37]. This ensures that a validated process can be reliably transferred between different molding machines with minimal variation, a crucial capability for multi-site manufacturing and validation [36].

Quantitative Process Parameters and Data

Successful process development hinges on establishing and controlling key parameters. The table below summarizes critical Controllable Process Variables (CPVs) and their impact on performance measures, synthesizing data from experimental studies.

Table 1: Key Controllable Process Variables and Their Effects

| Process Variable | Tier | Typical/Range | Primary Impact on Performance Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mold Temperature (°C) | Primary | 26.7 – 48.9 [26] | Affects crystallinity, surface finish, and warpage; must be balanced with cycle time [26]. |

| Melt Temperature (°C) | Primary | Material Dependent | Influences viscosity and flow length; too low causes short shots, too high risks degradation [26]. |

| Packing Pressure (MPa) | Primary | Machine: ~2.07 (Cavity: ~41.37) [26] | Compensates for volumetric shrinkage; prevents short shots and sinks; excessive pressure causes flash [26]. |

| Cooling Time (s) | Secondary | Varies by part geometry | Most significant factor for cycle time and warpage (28.78% contribution per ANOVA) [28]. |

| Packing Time (s) | Secondary | Until gate freeze-off | Must be sufficient to prevent backflow and control weight/shrinkage; optimized via DOE [26]. |

| Injection Speed | Secondary | Varies by material and part | Affects shear heating and fiber orientation; high speed can trap air (venting required) [38]. |

The following table provides an example of quantitative outcomes achievable through structured optimization of these parameters.

Table 2: Example Optimization Results for a PET Preform [28]

| Performance Measure | Initial Value | Optimized Value | Percent Improvement | Key Contributing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warpage | 0.2000 mm | 0.1905 mm | 4.75% | Cooling Time [28] |

| Part Weight | 43.25 g | 42.37 g | 2.05% | Optimized Packing Profile [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Process Development

Establishing the Process Window

A fundamental protocol in Scientific Molding is the empirical development of a process window—an operational envelope where CPVs produce acceptable parts [26].

Objective: To delineate the boundaries of key CPVs (e.g., melt temperature, packing pressure) that yield parts conforming to specified quality standards [26]. Materials: Injection molding machine, mold, thermoplastic material (e.g., Polypropylene), measurement instruments (e.g., Instron for mechanical properties, DSC for crystallinity) [26].

Procedure:

- Variable Identification: Classify CPVs into primary (mold temperature, melt temperature, packing pressure), secondary (injection speed, packing time, cooling time), and tertiary (clamping force, shot size) tiers. Focus experimentation on primary variables [26].

- Baseline Setting: Establish fixed, optimal values for secondary and tertiary variables through preliminary screening. For example, set injection speed to avoid visual defects and determine the minimum packing time to achieve part weight consistency [26].

- Boundary Exploration:

- Systematically vary one primary CPV (e.g., melt temperature) while holding others constant.

- Identify the lower limit (e.g., where short shots occur) and the upper limit (e.g., where flash or material degradation occurs) for that variable.

- Repeat this process for all other primary CPVs.

- Window Definition: The combination of all stable operating ranges for the primary CPVs defines the multi-dimensional process window. Operating near the center of this window provides maximum robustness against normal process variations [26].

Design of Experiments (DOE) for Optimization

DOE provides a structured, statistical framework for modeling complex interactions between multiple variables and identifying a global optimum, rather than just a stable window [39].

Objective: To model the relationship between multiple input variables (factors) and key output responses (e.g., warpage, weight) and determine the factor settings that produce the optimal response [40] [39]. Materials: Injection molding machine, calibrated sensors, statistical software (e.g., Minitab).

Procedure:

- Plan (Step 1): Define the objective (e.g., "minimize warpage and part weight"). Select the factors to study (e.g., cooling time, melt temperature, packing pressure) and their high/low levels. Determine the responses to measure (e.g., warpage in mm, weight in g) [39].

- Select Orthogonal Array (Step 2): Choose an experimental design, such as a Taguchi L27 orthogonal array, which allows for efficient testing of multiple factors with a minimal number of experimental runs [28] [39].

- Conduct (Step 3): Execute the experimental runs as specified by the design matrix. Randomize the run order to minimize the impact of confounding variables. Ensure strict adherence to the set parameters for each run and document any deviations [39].

- Analyze (Step 4): Measure all responses for each experimental run. Analyze the data using statistical methods like Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine the significance and percentage contribution of each factor. Utilize signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios to find factor levels that minimize variability [28] [39].

- Confirm (Step 5): Using the optimal factor levels predicted by the model, run a confirmation experiment. Verify that the results fall within predicted confidence intervals, thereby validating the model [39].

Diagram 1: The Five-Stage DOE Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The implementation of Scientific Molding relies on a suite of specialized tools and materials for data collection, analysis, and process control.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Scientific Molding Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| In-Mold Sensors (Pressure/Temperature) | Provide real-time data on conditions within the mold cavity, essential for machine-independent process development and documentation [37] [38]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Used to analyze DOE data, perform ANOVA, and create predictive models for process optimization and robustness validation [40] [39]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Characterizes the thermal properties of the polymer (e.g., melting point, crystallinity), which are critical for setting temperature parameters [26]. |

| Dual Column Load Frame (e.g., INSTRON) | Measures mechanical properties (tensile, flexural) of molded samples to quantitatively link process parameters to part performance [26]. |

| Process Simulation Software (e.g., Moldex3D) | Enables virtual DoE and mold flow analysis to predict fill patterns, cooling efficiency, and potential defects before physical tooling is made [26] [40]. |

| Standardized Test Mold | A mold that produces tensile, flexural, and impact test bars (per ASTM standards) for consistent and comparable material and process characterization [26]. |

Visualization of the Scientific Molding Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision-making process inherent in the Scientific Molding methodology, from initial setup to continuous monitoring.

Diagram 2: Scientific Molding Logic Flow.

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Parameter Optimization and Cycle Time Reduction

The injection molding industry faces persistent challenges in maintaining consistent product quality and optimizing production efficiency, with traditional methods often leading to significant material waste and financial losses. Research indicates that approximately 8-12% of injection molded parts fail quality checks, contributing to an estimated annual global loss of over $20 billion due to defects [41]. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) technologies represents a paradigm shift, enabling data-driven approaches for predictive parameter optimization and substantial cycle time reduction. This transformation is critical for advancing manufacturing precision in high-stakes sectors including medical devices, automotive components, and consumer electronics, where dimensional stability and production throughput are paramount [41] [9].

This document provides structured application notes and experimental protocols for researchers implementing AI-driven methodologies within injection molding processes. It establishes a framework for leveraging sensor data, machine learning algorithms, and digital twin technologies to achieve autonomous process optimization, with particular emphasis on predictive quality control and cycle time minimization within academic and industrial research contexts.

AI and ML Technologies in Injection Molding

The application of AI and ML in injection molding centers on several core technological frameworks that enable predictive optimization and real-time process control.

Core Machine Learning Frameworks

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): Multi-layered computational models that learn complex, non-linear relationships between process parameters (e.g., melt temperature, injection speed, holding pressure) and critical quality outcomes (e.g., part weight, dimensions, sink marks) [42]. ANNs excel at mapping high-dimensional input spaces to output predictions, facilitating robust quality prediction.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): An ML paradigm where an autonomous agent learns optimal control policies through trial-and-error interactions with the injection molding environment [42]. RL algorithms dynamically adjust process parameters to maximize a reward function, typically designed to minimize defects and cycle times while maximizing resource efficiency.

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): A powerful tree-based ensemble algorithm effective for tabular data analysis, capable of processing high-frequency, multi-variable time-series data from IoT sensors to predict product quality and recommend parameter adjustments [43]. XGBoost offers advantages in parallel computing, handling sparse data, and managing complex feature relationships.