Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Polymer Design: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores the pivotal role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the design and optimization of advanced polymer materials.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Polymer Design: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the pivotal role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the design and optimization of advanced polymer materials. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article systematically covers foundational principles, methodological approaches, optimization strategies, and validation techniques. It highlights how MD simulations provide atomic-scale insights into polymer behavior, enable prediction of structure-property relationships, and accelerate the development of polymers for biomedical applications including drug delivery systems, bioconjugates, and engineered tissues. By integrating recent advances in coarse-grained modeling, machine learning integration, and multiscale approaches, this resource demonstrates how computational methods are transforming polymer design paradigms while reducing experimental burden.

Fundamental Principles: How Molecular Dynamics Reveals Polymer Behavior at Atomic Scale

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. The trajectories of atoms and molecules are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [1]. This method is fundamentally applied in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of complex systems that are impossible to determine through analytical methods alone [1]. For researchers in polymer design, MD serves as a powerful in silico microscope, enabling the observation of polymer-oil interactions, the prediction of the impact of polymer wettability changes on recovery efficiency, and the systematic optimization of polymer properties for specific application environments [2].

The core components of any MD simulation consist of three essential elements: a force field that describes the potential energy of the system as a function of particle coordinates; a choice of statistical ensemble that defines the thermodynamic conditions of the simulation; and an integration algorithm that solves the equations of motion to propagate the system through time [1]. The careful selection and implementation of these components are critical for generating physically meaningful and statistically valid results. For the simulation of polymers in particular, such as those used in enhanced oil recovery, this framework allows scientists to probe the stability and rheological properties of polymers under high-temperature and high-salinity conditions, thereby guiding the design of novel materials like biopolymers and nanoparticle-enhanced polymers [2].

Force Fields: The Energy Landscape Foundation

Mathematical Formulation and Components

A force field refers to the combination of a mathematical formula and associated parameters that describe the energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates [3]. The total potential energy (( U_{\text{total}} )) in a typical classical, pairwise additive force field is a sum of several contributions, generally categorized as bonded and non-bonded interactions [4]. The canonical form is expressed in the equation below, which is central to molecular mechanics calculations:

The first three terms represent bonded interactions: bond stretching (harmonic potential), angle bending (harmonic potential), and torsional rotations (periodic potential). The final term describes non-bonded interactions, which include van der Waals forces (typically modeled by the Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law) [4] [5]. The Lennard-Jones potential, one of the most frequently used intermolecular potentials, is particularly important for describing repulsive and dispersive forces [1]. The accurate calculation of non-bonded interactions, especially long-range electrostatics, is paramount for charged macromolecules and is often handled using sophisticated methods like the Particle Mesh Ewald technique to avoid artifacts from simple truncation [4].

Classification and Selection of Force Fields

Force fields can be broadly classified based on their representation of the system and their treatment of electronic polarization. The choice of force field is a critical decision that depends on the specific system under study and the desired balance between accuracy and computational efficiency [5].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Dynamics Force Fields

| Force Field Type | Description | Common Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical (Classical) | Parameterized using experimental data and quantum mechanical calculations; typically non-polarizable. | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS-AA [3] [5] | Proteins, nucleic acids, organic molecules [4] [3] |

| Polarizable | Incorporate effects of induced dipoles and electronic polarization for more accurate electrostatics. | AMOEBA, Drude oscillator [5] | Ionic liquids, polarizable environments [5] |

| Reactive | Describe formation and breaking of chemical bonds. | ReaxFF, AIREBO [5] | Chemical reactions, bond breaking/formation [5] |

| Coarse-Grained | Reduce detail by grouping atoms into larger interaction sites; enable larger spatial and temporal scales. | MARTINI, ELBA [5] | Lipid membranes, large protein assemblies, polymer systems [2] [5] |

For polymer design research, particularly for oil-displacement polymers, the selection is crucial. All-atom force fields like OPLS-AA or CHARMM are often used for detailed studies of specific polymer-solvent interactions [2] [3]. However, to simulate the large-scale behavior of polymers at interfaces or in complex formulations, coarse-grained force fields like MARTINI are increasingly employed, as they allow access to longer timescales and larger system sizes relevant to macroscopic properties [2] [5].

Statistical Ensembles: Controlling Thermodynamic State

In molecular dynamics, the statistical ensemble defines the thermodynamic macrostate of the system and is conserved by the equations of motion and the application of thermostat and barostat algorithms. The most common ensembles used in MD simulations include:

- NVE (Microcanonical Ensemble): The system is isolated with constant Number of particles (N), constant Volume (V), and constant total Energy (E). This is the natural ensemble produced by Newton's equations of motion without modification.

- NVT (Canonical Ensemble): The system has constant Number of particles (N), constant Volume (V), and constant Temperature (T). Temperature is controlled using thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, velocity rescaling).

- NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble): The system has constant Number of particles (N), constant Pressure (P), and constant Temperature (T). This is the most common ensemble for simulating experimental conditions, requiring both a thermostat and a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

For systems that obey the ergodic hypothesis, the time averages of a single MD simulation correspond to the ensemble averages, allowing for the determination of macroscopic thermodynamic properties from the simulation [1]. The choice of ensemble directly impacts the properties that can be calculated. For example, polymer design for oil displacement often requires simulations in the NPT ensemble to model the behavior of polymers under specific reservoir pressure and temperature conditions [2].

Integration Algorithms: Propagating the System Through Time

Fundamental Algorithms and Their Characteristics

Integration algorithms are numerical methods for solving the coupled differential equations of motion (Newton's equations) for all particles in the system. These algorithms update particle positions and velocities over discrete timesteps (∆t). The stability and accuracy of the simulation are highly dependent on the choice of both the algorithm and the timestep [1]. Common timesteps for classical MD are on the order of 1-2 femtoseconds (10â»Â¹âµ s), often extended by constraining the bonds to hydrogen atoms using algorithms like SHAKE [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Integration Algorithms in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Mechanism | Key Properties | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | Updates positions using current positions, previous positions, and acceleration. | Time-reversible, symplectic. | Simple, good long-term energy conservation [1] [5]. | Limited accuracy; velocities not directly calculated [5]. |

| Velocity Verlet | Explicitly calculates positions and velocities at the same time point. | Time-reversible, symplectic. | Better energy conservation; velocities are directly available [5]. | Slightly more complex than basic Verlet. |

| Leapfrog | Updates positions and velocities at interleaved time points. | Time-reversible, symplectic. | Computationally efficient, good energy conservation [5]. | Positions and velocities not synchronized. |

| Multiple Timestep (RESPA) | Uses different timesteps for different interaction types (e.g., fast-bonded vs. slow-nonbonded). | Improves computational efficiency. | Allows larger effective timesteps, faster simulations [5]. | Requires careful tuning of timestep sizes for stability [5]. |

Workflow for Integration and Force Calculation

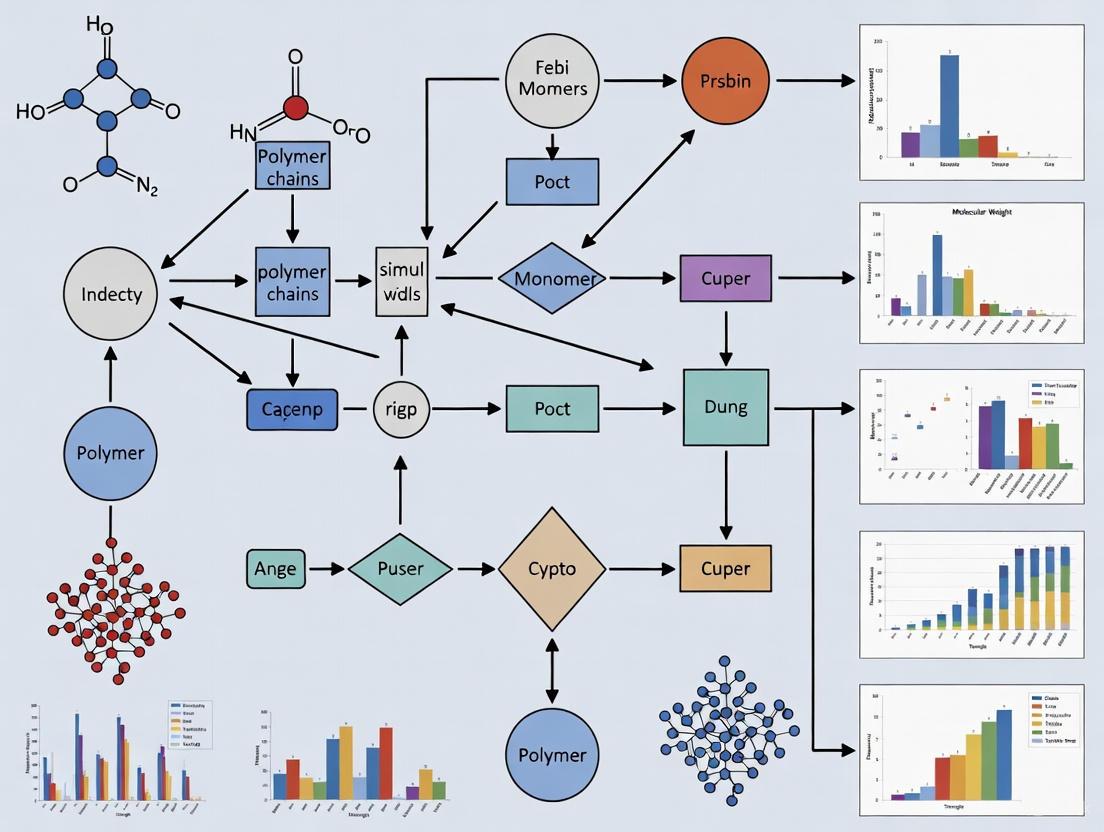

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and continuous cycle between the force field, the force calculation, and the integration algorithm within an MD simulation.

Application Notes and Protocols for Polymer Design

Protocol: Simulating Polymer-Oil Interactions for EOR

This protocol outlines the key steps for using molecular dynamics to study the interaction between oil-displacement polymers and crude oil components at the atomic scale, a critical process for enhancing oil recovery (EOR) [2].

System Construction

- Polymer Modeling: Build an all-atom or coarse-grained model of the polymer (e.g., Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide (HPAM) or a novel biopolymer) using a tool like Avogadro or CHARMM-GUI. For coarse-grained models, use a mapping procedure specific to the force field (e.g., MARTINI).

- Oil Model: Create a representative model of the reservoir oil. This can be a simple hydrocarbon like n-decane or a more complex mixture of alkanes and aromatics.

- Solvation and Ions: Solvate the polymer and oil in a water box using an appropriate water model (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P for all-atom; the corresponding coarse-grained water for MARTINI). Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to match the salinity of the target reservoir.

Simulation Setup

- Force Field Selection: Apply a suitable force field. For all-atom simulations, OPLS-AA or CHARMM are common choices. For coarse-grained studies aiming for larger scales, use MARTINI [2] [5].

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization (e.g., via steepest descent or conjugate gradient method) to remove any steric clashes and bad contacts in the initial configuration, typically for 5,000-50,000 steps.

- Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100-500 ps while holding the temperature constant (e.g., 300 K or the reservoir temperature) using a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover).

- NPT Equilibration: Further equilibrate the system for 100-500 ps while holding both temperature and pressure constant (e.g., 1 bar or reservoir pressure) using a thermostat and a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

Production Run

- Run a long-term simulation in the NPT ensemble for a duration sufficient to observe the phenomena of interest (nanoseconds to microseconds, depending on the system and model resolution). Use a time-reversible and symplectic integrator like Velocity Verlet with a timestep of 1-2 fs (all-atom) or 10-20 fs (coarse-grained).

- Employ periodic boundary conditions in all three dimensions.

- For long-range electrostatics, use the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [4]. For non-bonded interactions, apply a cutoff (e.g., 1.0-1.2 nm).

Analysis

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Analyze the g(r) between polymer functional groups and oil molecules to quantify their interaction strength and preferred binding sites.

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): Calculate the MSD of oil molecules to study diffusivity changes in the presence of the polymer.

- Interfacial Properties: Measure the interfacial tension between the aqueous polymer solution and the oil phase.

- Polymer Conformation: Monitor the radius of gyration and end-to-end distance of the polymer to understand its conformation at the interface.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for MD in Polymer Design

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields (CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA) | Provide parameter sets for simulating polymers, proteins, and other organic molecules. | Simulating hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) and its interactions [3]. |

| Coarse-Grained Force Fields (MARTINI) | Enable simulation of larger systems and longer timescales by grouping atoms into beads. | Studying large-scale polymer aggregation or polymer-membrane interactions [5]. |

| Water Models (SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) | Explicitly represent water molecules in the simulation box. | Solvating polymer-oil systems to model aqueous reservoir conditions [4]. |

| MD Software Packages (GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, LAMMPS) | Software suites that perform the numerical integration, force calculation, and analysis. | Running production simulations; GROMACS is noted for its efficiency and scalability [4]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (Replica Exchange, Metadynamics) | Accelerate the sampling of conformational space and rare events. | Studying polymer folding or the crossing of high energy barriers at oil-water interfaces [6]. |

| Tribenoside | Tribenoside Research Chemical|CAS 10310-32-4 | High-purity Tribenoside for vascular and inflammation research. This product, CAS 10310-32-4, is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Samandarone | Samandarone, CAS:467-52-7, MF:C19H29NO2, MW:303.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool in polymer science, providing atomic-scale resolution into the properties and behaviors that govern polymer performance. For researchers and scientists engaged in polymer design, particularly for advanced applications in drug development and high-performance materials, MD offers critical insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally. This application note details protocols and methodologies for investigating three fundamental polymer properties—glass transition, chain dynamics, and conformational analysis—within the broader context of molecular dynamics simulations for polymer design research. By integrating these computational approaches, researchers can establish robust structure-property relationships essential for rational polymer design, potentially accelerating development cycles for polymeric therapeutics and advanced materials.

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Analysis

Theoretical Background and Significance

The glass transition temperature (Tg) marks the critical transition where a polymer changes from a rigid, glassy state to a flexible, rubbery state. This property fundamentally governs polymer processing, mechanical behavior, and application temperature ranges. For polymer electrolytes in energy storage devices, Tg dictates the onset of segmental motion within polymer chains, which leads to increased chain mobility and facilitates coupled ion transport as understood through free volume theory [7]. In MD simulations, Tg is determined by monitoring the change in polymer density during cooling, where the transition manifests as a distinct slope change in the density versus temperature profile [7].

Computational Protocols

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Initial Configuration: Build polymer system using tools like GroPoB or the Amorphous Cell module in Materials Studio [7] [8].

- Energy Minimization: Employ steepest descent algorithm to eliminate high-energy atomic clashes [7].

- Equilibration Steps:

- Conduct NVT (constant number, volume, and temperature) ensemble simulation at elevated temperature (e.g., 400 K) for 10 ns to stabilize temperature [7].

- Perform NPT (constant number, pressure, and temperature) ensemble simulation with temperature cycling (e.g., 400 K to 1000 K and back to 400 K) for 10 ns to ensure complete amorphousness [7].

- Execute final NPT run at target temperature (e.g., 400 K) for 10 ns to stabilize density [7].

Annealing Methods for Tg Determination Two primary annealing approaches have been established for Tg determination:

Stepwise Cooling Protocol [7]:

- Run multiple NPT simulations from high to low temperature range (e.g., 540 K to 40 K) with defined step size (e.g., 20 K).

- At each temperature, perform 2 ns equilibration followed by 2 ns production run.

- Total simulation time: approximately 100 ns.

Continuous Cooling Protocol [7]:

- Conduct single NPT simulation from high to low temperature (e.g., 540 K to 40 K) at specific cooling rates.

- Cooling rates typically range from 5 K/ns to 5000 K/ns, with slower rates (5-50 K/ns) providing better agreement with experimental data.

- To assess thermal history effects, follow initial cooling with heating and second cooling simulation.

Table 1: Comparison of Annealing Methods for Tg Determination

| Parameter | Stepwise Cooling | Continuous Cooling |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Higher (~100 ns) | Variable (0.1-100 ns) |

| Cooling Rate Control | Discrete steps | Continuous range |

| Density Profile | Smooth, defined transitions | Rate-dependent |

| Recommended Use | High-precision studies | Screening multiple systems |

Data Analysis Methods

- Bilinear Fitting: Plot specific volume or density against temperature; fit separate regression lines to high-temperature (rubbery) and low-temperature (glassy) regions; Tg is the intersection point [7].

- Slope-Temperature Analysis: Calculate the slope from linear regression of densities within a moving temperature window (e.g., [T, T+50 K]); Tg corresponds to the transition point where slope changes significantly [7]. This method reduces human bias in selecting fitting ranges.

Critical Parameters and Validation

MD simulations consistently overestimate experimental Tg values by approximately 80-120 K, primarily due to extremely fast cooling rates (10^9 K/s in MD versus 10^-2-10^-1 K/s in experiments) and force field limitations [7]. Researchers should utilize normalized temperatures (T - Tg) when comparing simulation results with experimental data [7]. Validation through experimental comparison is essential, with reported Tg values for PEO systems ranging from 250-320 K depending on molecular weight and force field used [7].

Polymer Chain Dynamics

Segmental Motion and Relaxation

Chain dynamics encompass the molecular motions of polymer chains, ranging from local segmental movements to whole-chain relaxations. These dynamics fundamentally influence polymer processing, mechanical properties, and performance in applications such as drug delivery systems. MD simulations enable direct investigation of these motions across multiple time and length scales. At solid-melt interfaces, chain dynamics are significantly altered, with studies showing that all relaxation processes of chains located within a couple of radii of gyration from the surface are considerably slowed down [9].

Analysis Methods for Chain Dynamics

Mean Square Displacement (MSD) MSD analysis quantifies molecular mobility and diffusion coefficients through the relationship: MSD(τ) = ⟨|r(t+τ) - r(t)|²⟩, where r(t) is position at time t, and τ is time lag [8]. For polymer electrolytes, MSD helps understand ionic conductivity mechanisms by tracing polymer segmental motion and ion transport coupling [7].

Radius of Gyration (Rg) Rg measures chain compactness and conformation defined as: Rg² = (1/N)Σᵢ|rᵢ - rcm|², where N is number of atoms, rᵢ is atom position, and rcm is center of mass [10]. This parameter helps understand chain folding, swelling, and conformational changes in response to environmental stimuli.

Local Radius of Gyration For adsorbed polymer chains, the local radius of gyration serves as a segmental-scale structural descriptor to quantify conformational changes under mechanical strain, revealing distinct modes including tail elongation, loop-to-tail transition, and chain desorption [10].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Analyzing Polymer Chain Dynamics

| Metric | Definition | Information Obtained | Application Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Square Displacement (MSD) | ⟨ | r(t+τ) - r(t) | ²⟩ | Chain mobility, diffusion coefficients | Ion transport in polymer electrolytes [7] |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | √[(1/N)Σᵢ | rᵢ - r_cm | ²] | Chain compactness, conformation | Thermosensitive gelation [11] |

| Local Rg | Rg calculated for specific segments | Segmental conformational changes | Polymer-metal adhesion [10] |

Conformational Analysis

Chain Conformations at Interfaces

Conformational analysis examines the spatial arrangement of polymer chains, which directly influences material properties and performance. At polymer-solid interfaces, chains adopt distinct conformations characterized by three segment sequences: trains (segments directly adsorbed), loops (segments bridging between adsorption points), and tails (free ends) [10]. MD simulations reveal that these interfacial conformations respond differently to mechanical strain compared to bulk chains, significantly impacting adhesion strength in polymer-metal composites [10].

Advanced Conformational Characterization

Local Conformational Descriptors The introduction of segmental-scale structural descriptors, such as the local radius of gyration, enables quantitative analysis of conformational changes in adsorbed chains under deformation. This approach has revealed three distinct conformational modes in polyamide-alumina interfaces under tensile strain: tail elongation, loop-to-tail transition, and chain desorption [10].

Radial Distribution Function (RDF) RDF analysis, denoted as g(r), quantifies the probability of finding atom pairs at specific distances, revealing short-range ordering and intermolecular interactions [8] [11]. In thermosensitive MPC-g-MC hydrogels, RDF of oxygen atoms around -OH groups demonstrated reduced hydration shells with increasing temperature, confirming the role of hydrophobic interactions in gelation [11].

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) SASA measures surface area accessible to solvent molecules, helping quantify hydrophobic interactions during temperature-induced transitions. In MPC-g-MC hydrogel studies, hydrophobic SASA decreased more significantly than hydrophilic SASA during heating, identifying hydrophobic interactions as the major thermodynamic driver of gelation [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Polymer MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | OPLS, GAFF, COMPASS II, TraPPE-UA, pcff+ | Define mathematical forms and parameters governing intermolecular interactions | OPLS-AA for PEO/LiTFSI systems [7] |

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, LAMMPS, Materials Studio | Perform energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD simulations | GROMACS for hydrogel studies [11] |

| Analysis Tools | Built-in trajectory analysis, VMD, MDTraj | Calculate properties (RDF, MSD, Rg), visualize trajectories | Hydrogen bonding analysis in hydrogels [11] |

| System Building | GroPoB, Amorphous Cell | Construct initial polymer configurations | GroPoB for polymer electrolytes [7] |

Workflow Visualization

MD simulations provide powerful methodologies for investigating fundamental polymer properties including glass transition, chain dynamics, and conformational changes. The protocols detailed in this application note establish robust frameworks for extracting critical design parameters essential for advanced polymer development. As MD capabilities continue to advance through integration with machine learning approaches and enhanced computing power, these simulation techniques will play increasingly pivotal roles in rational polymer design for pharmaceutical applications and advanced materials engineering.

The design of advanced polymeric materials is fundamentally governed by the complex relationship between their molecular architecture and their resulting macroscopic behavior. A polymeric structure, composed of multiple simpler chemical units called monomers, sees its properties—from microstructures to physical and mechanical behaviors—governed by the chemical structure of these monomers and their specific arrangements [12] [13]. Understanding the sequence-structure-property relationships is therefore critical for tailoring materials with superior performance for applications in energy, environmental conservation, and biomedicine [12] [14].

However, a significant challenge persists in bridging the vast gap between the atomic scale, where monomers interact, and the macroscopic scale, where material properties are observed. Traditional design approaches are often hampered by the immense complexity of the chemical space, as well as prohibitive costs and time requirements [12] [13]. For instance, a polymer chain of just 30 units composed of two monomer types can have over 500 million possible sequences, making exhaustive experimental investigation impossible [12]. Fortunately, the integration of computational methods, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, with emerging machine learning (ML) techniques, provides a powerful platform to overcome these bottlenecks, enabling the prediction and inverse design of polymers with targeted properties [12] [13].

Computational Framework: Bridging the Scale Divide

The Role of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a computational microscope, allowing researchers to observe and quantify the behavior of polymer chains at resolutions that are often difficult to achieve experimentally. MD has demonstrated robustness in capturing essential physical and mechanical properties of polymers, including glass transition temperature, viscosity, dynamics and relaxation, phase separation, crystallization, and mechanical properties like Young’s modulus and yield strength [13].

Table 1: Key Properties Accessible via Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Property Category | Specific Examples | Relevance to Macroscopic Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Properties | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Determines service temperature and processing conditions. |

| Mechanical Properties | Young's Modulus, Yield Strength | Predicts material stiffness, strength, and durability. |

| Dynamic Properties | Viscosity, Relaxation Dynamics | Informs processability and long-term stability. |

| Morphological Properties | Phase Separation, Crystallization | Controls optical, barrier, and mechanical properties. |

Among different MD techniques, coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) is particularly valuable for bridging scales. CGMD reduces computational cost and complexity by grouping multiple atoms into a single "bead" or interaction site, thereby simplifying the chemical space while maintaining sufficient modeling accuracy [12] [13]. This approach allows simulations to access longer time and length scales, which are crucial for observing polymer chain folding, self-assembly, and other mesoscale phenomena that directly influence macroscopic material behavior [12].

Integration with Machine Learning

While powerful, MD simulations alone can be computationally prohibitive for exploring vast polymer design spaces. The integration of machine learning with CGMD has emerged as a transformative strategy [12]. In this hybrid approach:

- CGMD simulations are leveraged to generate high-quality training datasets for specific polymer systems.

- ML-based surrogate models are then developed to learn the complex relationships between monomer sequence, chain configuration, and functional properties from this data [12] [13].

This computational hybridization establishes reliable sequence-functional behavior relationships and guides the selection of optimal polymer chain candidates from a virtually limitless chemical space, all with a fraction of the computational cost and time of traditional simulation-only approaches [12]. Key applications of this integration fall into three areas: polymeric configuration characterization, feed-forward property prediction, and inverse molecular design [12].

Application Notes: From Theory to Practice

Understanding and Designing Sequence-Defined Polymers

The development of synthetic sequence-defined polymers offers enormous opportunities for materials design with tailored microstructure and mechanical properties [12] [13]. Monomer sequence dictates critical chain-level properties such as polymer configurations, radius of gyration, and self-assembly behaviors through inter- and intra-molecular interactions [13]. The CGMD/ML integration allows researchers to answer fundamental questions, such as to what extent chain sequence influences mechanical properties and how monomer sequence scales to the chain length scale [13].

Case Study: Microstructure-Engineered Polymers for Sustainability

Engineering polymer microstructures—including chain length distribution, regio-/stereoregularity, monomer sequence, and chain architecture—provides a powerful toolbox for designing materials for energy and environmental applications [14].

Table 2: Impact of Polymer Microstructure on Material Function

| Microstructural Feature | Application Example | Structure-Function Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Length Distribution (Dispersity, Ä) | Antifouling surfaces [14], Membrane modification [14] | High dispersity (Ä = 1.95) PAA brushes form thicker films in response to pH, enabling more efficient bacterial detachment [14]. Polydisperse graft copolymer side chains enhance hydration and lubrication in nanofiltration membranes [14]. |

| Regioregularity (RR) | Conjugated Polymers for Photovoltaics [14] | High RR P3HT (e.g., 95.2%) enables more ordered chain packing, leading to significantly larger short-circuit current density and higher power conversion efficiency in solar cells compared to lower RR (90.7%) [14]. |

| Monomer Sequence | Self-assembly, Phase Separation [12] | Controlled monomer sequences in block copolymers can lead to desired phase separation or crystallization of microstructure, dictating final material properties [12]. |

For instance, in conjugated polymers like poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), the regioregularity—defined by the fraction of head-to-tail linkages—profoundly influences chain packing and optoelectronic properties [14]. High RR P3HTs undergo more ordered chain packing to form microcrystalline lamellae that promote stronger intra- and interplane orbital coupling and charge transfer [14]. This microstructure-property relationship directly impacts the performance of bulk heterojunction solar cells, where blends containing P3HT of 95.2% RR displayed twice the short-circuit current density and three times the power conversion efficiency compared to blends with 90.7% RR P3HTs [14].

Experimental Protocols

A Streamlined Workflow for All-Atomistic MD Simulation of Polymers

Accurate modeling of amorphous polymers, including porous organic polymers (POPs), requires careful parameterization and system setup. The following protocol, implemented in the PolyPal Python package, provides a streamlined workflow for all-atomistic MD simulations [15].

Force Field Parametrization

- Objective: Generate accurate, molecule-specific force field parameters, particularly for nonstandard monomers common in POPs (e.g., triptycene) [15].

- Procedure:

- Oligomer Construction: Build an oligomer of the target polymer that is large enough to account for dispersion effects across monomer units, flexible dihedrals between monomers, and potential stereochemistry. The oligomer should not be excessively long to avoid prohibitive computational cost for Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations [15].

- Quantum Mechanical Calculation: Use a quantum chemistry package (e.g., ORCA or Gaussian) to generate QM data for the oligomer [15].

- Force Field Generation: Utilize Q-Force to derive all-atomistic force field parameters from the QM data. Q-Force employs a fragmentation scheme to partition the oligomer into chemically meaningful smaller fragments, reducing the cost of computing potential energy scans for flexible dihedrals while retaining the nonbonding parameters of established transferable force fields (e.g., OPLS, GROMOS) [15].

Polymer Chain Assembly and System Preparation

- Objective: Create polymer chains of defined composition and length and prepare them for simulation [15].

- Procedure:

- Monomer Input: Using the force field generated from the oligomer, define the monomer building blocks in Assemble! [15].

- Chain Generation: In Assemble!, specify the desired polymer composition and chain length. The program uses virtual "hooks" connected to the terminal atoms of molecular subunits to arrange the monomer sequence. It checks for atomic clashes during chain buildup, perturbing dihedral angles iteratively until clashes are resolved, resulting in a locally relaxed polymer chain [15].

- Partial Charge Calculation: Calculate partial charges for the polymer chains using the ASCII method [15].

- System Packing: Pack the generated polymer chains into a simulation box using a MD simulation package like GROMACS [15].

Simulation Execution

- Objective: Equilibrate and run production simulations to study polymer properties.

- Procedure:

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the energy of the packed system to remove any residual steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Perform equilibration runs in appropriate ensembles (e.g., NPT, NVT) to relax the density and structure of the system. This may include annealing cycles to properly sample the configuration space [15].

- Production Simulation: Run a longer production simulation under the desired conditions (temperature, pressure) to collect trajectory data for analysis [15].

Protocol for Scale-Bridging Pyrolysis Modeling

For processes involving chemical reactions, such as pyrolysis, a scale-bridging approach using reactive force fields is required.

Pyrolysis Kinetics with ReaxFF-MD

- Objective: Elucidate the pyrolysis kinetics of a crosslinked polymer (e.g., phenolic formaldehyde resin) [16].

- Procedure:

- System Setup: Construct a model of the crosslinked polymer network.

- Reactive Simulation: Perform MD simulations using a reactive force field (ReaxFF) potential, which allows for bond breaking and formation.

- Thermal Decomposition Analysis: Heat the system incrementally (e.g., from 300 K to 2500 K) and monitor the decomposition products. Pyrolysis initiation temperature (∼500 K for phenolic resin) and the sequence of chemical events (e.g., removal of -OH groups and H atoms releasing H2O, followed by C-ring fragmentation) can be identified [16].

- Kinetic Parameter Extraction: Calculate pyrolysis rates from the MD simulations, which can be used to develop a larger-scale thermal material response model for predicting performance under operational conditions (e.g., heat shielding) [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Simulation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [15] | Molecular Dynamics Engine | High-performance MD simulation | Free, open-source, highly optimized for CPU/GPU. |

| LAMMPS [15] | Molecular Dynamics Engine | Large-scale atomic/molecular simulator | Open-source, highly versatile, supports many force fields. |

| ORCA [15] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Electronic structure calculations | Generates QM data for force field parametrization. |

| Q-Force [15] | Force Field Generator | Derives molecule-specific FF parameters | Uses fragmentation to reduce QM computation cost. |

| Assemble! [15] | Polymer Builder | Constructs polymer chains of defined sequence | Uses "hooks" to connect monomers, checks for clashes. |

| PolyPal [15] | Python Package | Streamlines workflow between different programs | Bridges Q-Force, Assemble!, and GROMACS/LAMMPS. |

| ReaxFF [16] | Reactive Force Field | Models chemical reactions in MD | Enables simulation of bond breaking/formation (e.g., pyrolysis). |

| Sapienic acid | Sapienic Acid|16:1Δ6 Fatty Acid|Research Use | Bench Chemicals | |

| Saquayamycin D | Saquayamycin D, CAS:99260-71-6, MF:C43H50O16, MW:822.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of multi-scale molecular dynamics simulations—from all-atomistic to coarse-grained models—with machine learning algorithms represents a paradigm shift in polymer materials design. This computational framework successfully bridges the traditional divide between monomer-level interactions and macroscopic material behavior, enabling the establishment of critical sequence-structure-property relationships. As methodologies for force field parametrization, system assembly, and simulation continue to be streamlined into accessible workflows and software packages, the barrier to performing predictive modeling for complex polymer systems is significantly lowered. This advancement paves the way for the rapid, rational design of next-generation polymers with tailored properties for sustainability, energy conversion, and advanced technological applications, accelerating the journey from molecular insight to functional material.

Within the broader scope of a thesis on molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for advanced polymer design, this application note addresses the critical foundation of any reliable simulation: the correct setup of environmental controls. The accurate parameterization of temperature, pressure, and the subsequent analysis of density is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental determinant of the physical realism of the simulation outcomes. These parameters directly control polymer phenomena under investigation, from the glass transition and thermal expansion to mechanical response and gas diffusion properties. This document provides detailed protocols for establishing these controls, with a specific focus on achieving experimental concordance in polymer systems.

Fundamental Ensemble Controls

Temperature Coupling Algorithms

Maintaining a stable and accurate temperature is critical for simulating the thermodynamic states of polymers. The choice of thermostat significantly influences the quality of the generated trajectory.

- Berendsen Thermostat: Recommended for the equilibration phase of polymer systems due to its strong coupling to a heat bath, which provides rapid relaxation to the target temperature. A damping constant of 100 fs is typically effective for achieving thermal stability [17].

- Nosé-Hoover Langevin Thermostat: Ideal for the production phase of simulations, as it correctly generates a canonical (NVT) ensemble. It provides a more physically realistic representation of temperature fluctuations compared to the Berendsen thermostat [18].

The simulated annealing procedure, used for finding low-energy configurations or calculating properties like the glass transition temperature (Tg), requires a defined temperature program. This involves a series of linear temperature ramps and plateaus. For instance, a robust protocol heats the system from 298.15 K to 598.15 K in 25 K increments, with each step consisting of a 30,000-step heating period followed by a 10,000-step sampling period at the plateau temperature, before cooling back to the initial temperature [17].

Pressure Coupling Algorithms

Isotropic pressure control is essential for simulating realistic densities and volumes of polymer systems, especially under the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble.

- Berendsen Barostat: Effective during equilibration for its ability to efficiently scale the simulation box dimensions to reach the desired pressure. A damping constant of 500 fs is commonly used to maintain a pressure of 1 atm [17].

- Parrinello-Rahman Barostat: Preferred during production runs because it generates a correct isothermal-isobaric ensemble, allowing for legitimate fluctuations in the box size [19].

Core Application: Determining the Glass Transition Temperature

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical property dictating a polymer's application temperature range. Molecular dynamics simulation allows for its calculation from the change in the temperature-density relationship.

Protocol for Tg Calculation via Density Analysis

The following workflow outlines the primary method for determining Tg from the specific volume versus temperature profile obtained from an annealing simulation [17] [7].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Construct an amorphous polymer cell using a tool like

GroPoB[7]. - Perform energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm.

- Equilibrate the system in the NVT ensemble at 400 K for 10 ns to stabilize the temperature.

- Further equilibrate in the NPT ensemble with a temperature cycle (e.g., 400 K → 1000 K → 400 K over 10 ns) to ensure complete amorphization and erase historical memory of the initial configuration.

- Conduct a final 10 ns NPT run at the starting temperature of the annealing cycle (e.g., 400 K) to stabilize the density [7].

- Construct an amorphous polymer cell using a tool like

Annealing Simulation: Two primary methods are employed, each with distinct advantages.

- Method A: Stepwise Cooling: Run sequential NPT simulations from a high (e.g., 540 K) to a low temperature (e.g., 40 K) with a step size of 20 K. At each temperature, perform a 2 ns equilibration followed by a 2 ns production run to sample the density. This method, while computationally intensive, provides well-equilibrated data points [7].

- Method B: Continuous Cooling: Run a single, continuous NPT simulation from high to low temperature. The cooling rate must be chosen carefully, as it significantly impacts the result. Slower cooling rates (e.g., 5-50 K/ns) yield densities and Tg values closer to those from stepwise cooling and experimental results. Faster rates (e.g., 5000 K/ns) can lead to unrealistic densities and an overestimation of Tg [7].

Data Analysis for Tg:

- Extract the average density from the production phase at each temperature.

- Plot density (or specific volume) as a function of temperature.

- Perform two linear regressions: one through the data points in the high-temperature (rubbery) region and another through the points in the low-temperature (glassy) region.

- The glass transition temperature, Tg, is defined as the intersection point of these two fitted lines [17].

Table 1: Impact of Simulation Parameters on Calculated Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

| Parameter | Effect on Simulated Tg | Recommendation for Realistic Results |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling Rate | Faster rates lead to higher Tg due to non-equilibrium conditions [7]. | Use slow cooling (e.g., 5-50 K/ns) or stepwise annealing [7]. |

| Molecular Weight | Tg increases with molecular weight, plateauing above a threshold [19]. | Use a chain length above the critical molecular weight (e.g., ~11,240 g/mol for PEO) [19]. |

| Force Field | Different force fields have varying parameterizations for bonded and non-bonded interactions. | Select a force field validated for polymers (e.g., COMPASS, OPLS-AA) [7] [20]. |

| Presence of Salt | Adding ions (e.g., LiTFSI) can increase Tg by 20-30 K by restricting chain motion [7]. | Account for this plasticizing effect in polymer electrolyte simulations. |

Advanced Considerations for Property Calculation

Thermal and Mechanical Properties

Beyond Tg, the protocols described enable the calculation of other key properties.

- Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE): The slope of the specific volume vs. temperature plot in the rubbery and glassy states corresponds to the CTE of the polymer in those regimes [19].

- Thermo-Mechanical Properties: By analyzing stress-strain relationships from simulated deformation, properties like Young's modulus can be derived. Simulations of crosslinked epoxies, for example, show that higher crosslinking degrees enhance the overall mechanical properties [21].

Diffusion and Sorption Properties

For applications like gas separation membranes or packaging, simulating the diffusion of small molecules in polymers is essential.

- Free Volume Analysis: The Fractional Free Volume (FFV) is a key metric. Under tensile strain, the FFV and pore size distribution in polymers like 6FDA-durene polyimide change, directly impacting gas diffusivity and selectivity [22].

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): The diffusion coefficient (D) of a penetrant gas (e.g., H2O, O2, H2) can be calculated from the slope of its MSD over time using the Einstein relation. Studies on polypropylene show that clustering of polar molecules like H2O and H2O2 can significantly reduce their diffusion coefficients [20].

Table 2: Key Analysis Methods for Polymer Properties from MD Simulations

| Target Property | Simulation Analysis Method | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Intersection of linear fits to density-temperature data from annealing [17] [7]. | Optimizing epoxy resin reliability in electrical insulators [21]. |

| Thermal Expansion | Slope of specific volume vs. temperature plot [19]. | Predicting dimensional stability of components under thermal cycling. |

| Mechanical Properties | Stress-strain response from simulated uniaxial deformation [22]. | Screening polyimide membranes for mechanical robustness under strain [22]. |

| Gas Diffusion Coefficient | Slope of mean squared displacement (MSD) vs. time [20]. | Designing polypropylene for food packaging with low oxygen permeability [20]. |

| Sorption Loading | Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations [20]. | Predicting saturation concentration of H2O in polypropylene [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists essential software and computational resources used in the protocols cited in this document.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions - Key Software for Polymer MD

| Software / Resource | Function | Relevance to Polymer Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| AMS/ReaxFF [17] | Molecular dynamics software with reactive force fields. | Used for simulating cross-linking reactions and calculating Tg from density profiles. |

| GROMACS [23] | High-performance MD simulation package. | Widely used for biomolecular and polymer simulations due to its high efficiency and rich analysis tools. |

| LAMMPS [24] | Classical molecular dynamics simulator. | Highly versatile for a wide range of materials, including polymers, metals, and soft matter, with extensive force field support. |

| Materials Studio [21] [20] | Modeling and simulation environment. | Provides a comprehensive GUI for model building (e.g., amorphous cell), simulation setup, and analysis of polymer systems. |

| COMPASS Force Field [20] | Atomistic force field. | Optimized for condensed-phase applications, providing accurate predictions of structural, vibrational, and thermophysical properties for polymers. |

| GroPoB [7] | Protocol/GitHub repository. | A step-by-step guide and tools for building initial configurations and input files for polymer electrolyte systems. |

| Saringosterol | Saringosterol, CAS:6901-60-6, MF:C29H48O2, MW:428.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sarmentosin | Sarmentosin, CAS:71933-54-5, MF:C11H17NO7, MW:275.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram synthesizes the logical relationships between the controlled simulation parameters, the analyzed properties, and the resulting polymer performance characteristics, as established by the cited research.

Advanced Simulation Methods and Their Applications in Polymer Design and Biomedical Innovation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable tools in computational biology and materials science, enabling the study of molecular systems at atomic resolution. All-atom molecular dynamics (AAMD) simulations provide high accuracy by explicitly representing every atom, making them particularly adept at capturing detailed interfacial interactions [25]. However, the computational expense of AAMD limits the accessible temporal and spatial scales. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) addresses this limitation by simplifying molecular structures into representative beads, reducing the number of degrees of freedom and computational cost, thereby extending simulation capabilities from picoseconds to microseconds and from nanometers to micrometers [26] [25]. This application note examines the balance between accuracy and computational efficiency in AAMD and CGMD, providing structured comparisons, detailed protocols, and practical guidance for researchers engaged in polymer design and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of MD Approaches

The choice between AAMD and CGMD involves trade-offs between resolution, computational demand, and the specific research questions being addressed. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of All-Atom and Coarse-Grained MD

| Feature | All-Atom MD (AAMD) | Coarse-Grained MD (CGMD) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic detail (individual atoms) | Reduced detail (groups of atoms as single beads) [27] |

| Temporal Scale | Picoseconds to nanoseconds [28] | Nanoseconds to microseconds, even milliseconds [25] [29] |

| Computational Cost | High | Significantly lower [27] |

| Primary Strength | High accuracy for local interactions and specific binding | Studying large-scale dynamics and collective behavior [30] [26] |

| Key Limitation | Computationally prohibitive for large/long systems | Loss of atomic detail; potential need for re-parametrization [25] |

| Typical Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS [31] | MARTINI, SIRAH, AICG2+ [30] [27] [32] |

Beyond these fundamental characteristics, the performance and output of these methods can be quantified. The following table compares key performance metrics and typical application outputs, providing a concrete basis for selection.

Table 2: Performance and Output Comparison

| Aspect | All-Atom MD (AAMD) | Coarse-Grained MD (CGMD) |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Speed | ~8.5 ns/day on an 8-core CPU [33] | Orders of magnitude faster than AAMD [27] |

| System Size Limit | Realistically up to millions of atoms | Viruses, chromatin, large polymer assemblies [32] |

| Representative Output | Atomic-level trajectories, ligand binding poses, interaction energies | Large-scale conformational changes, self-assembly pathways, free energy landscapes |

| Property Reproduction | Density, atomic RMSD, binding free energies | Density, radius of gyration (Rg), large-scale dynamics [27] [25] |

Methodological Workflows

A successful MD study requires a structured workflow, from system preparation to analysis. The general pathways for AAMD and CGMD share similarities but involve distinct steps and considerations.

All-Atom MD Protocol for Protein-Ligand Systems

This protocol provides a detailed workflow for setting up and running an all-atom molecular dynamics simulation to study the interactions of a peripheral membrane protein with a model lipid bilayer, adaptable for various protein-ligand systems [31].

Initial System Setup and Parameterization

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the initial atomic coordinates from a database like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Use a tool like PDBFixer to add missing atoms, protonate the structure (add hydrogens), and correct for any missing residues [33].

- Force Field Assignment: Apply a well-validated all-atom force field. For proteins and nucleic acids, AMBER or CHARMM force fields are standard. For small molecules (e.g., ligands), use the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) or its successor GAFF2 to generate parameters [31] [33].

- Solvation: Place the molecular system in a solvent box (e.g., a rectangular or cubic box) using a water model such as TIP3P. The box size should provide sufficient padding (e.g., 1.0 to 1.5 nm) between the solute and the box edges to avoid periodicity artifacts [31] [33].

- Neutralization and Ion Concentration: Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's net charge. Further ions can be added to achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) [31].

Simulation Execution

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization step to remove any bad steric clashes and relieve residual strain in the initial structure. This is typically done using a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm for a few thousand steps.

- Equilibration: a. Restrained Equilibration (NVT): Perform the first equilibration in the canonical (NVT) ensemble, applying positional restraints on the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand. This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute. b. Unrestrained Equilibration (NPT): Conduct a second equilibration in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble without restraints, allowing the entire system to reach the correct density and temperature (e.g., 303 K) and pressure (1 atm) [31] [33].

- Production Simulation: Run the final, unrestrained production simulation in the NPT ensemble. This generates the trajectory used for analysis. The length of this simulation depends on the biological process under investigation, but modern studies often range from hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds [28].

Analysis

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the production trajectory to compute properties of interest. Common metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies residue-wise flexibility.

- Binding Free Energy: Calculated using methods like MMPBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area), which requires ~15 minutes per calculation in a typical setup [33].

Coarse-Grained MD Protocol for Biomolecules

This protocol outlines the steps for conducting coarse-grained simulations using the GROMACS software package, which is widely used for its high performance and extensive analysis tools [27].

System Construction and Force Field Selection

- CG Mapping: Convert the all-atom structure to a coarse-grained representation. The mapping scheme is defined by the chosen force field. For example, in the SIRAH force field, the protein backbone and side chains may have different resolutions, while the MARTINI force field typically maps 2-5 heavy atoms onto a single CG bead [30] [27].

- Topology Generation: Create the system topology using the chosen CG force field (e.g., MARTINI, SIRAH, ELBA, or CGenFF). This defines the bonded (bonds, angles) and non-bonded (van der Waals, electrostatic) interactions between CG beads [27]. Automated web servers like the CGMD Platform can assist in preparing input files [34].

- Solvation: Solvate the system with CG water models, which are simplified representations of explicit water, or use an implicit solvent model to further speed up calculations [32].

Simulation and Analysis

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Similar to AAMD, the CG system must be energy-minimized and equilibrated under NVT and NPT conditions to ensure stability before production runs.

- Production Simulation: Run the production CGMD simulation. The integration time step can often be increased (e.g., 20-40 fs) compared to AAMD (1-2 fs) due to the smoother energy landscape. This, combined with the reduced number of particles, allows for microsecond-scale simulations [27].

- Analysis of CG Trajectories: Analyze the trajectory using GROMACS tools or other software. Key analyses include:

- Backmapping (Optional): For a higher-resolution view of specific conformations, the CG trajectory can be "backmapped" to reconstruct an all-atom model. This allows for detailed analysis of interactions that are lost at the CG level [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential software, force fields, and resources required for implementing the protocols described in this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Server | Input Generator for MD | Provides a graphical interface for building complex systems (e.g., membranes, polymers) for various simulation packages [31] |

| GROMACS | Software Package | MD Simulation Engine | Highly optimized for performance on CPUs and GPUs; extensive support for both AA and CG force fields [27] |

| CGMD Platform | Web Server | CG Simulation Preparation & Analysis | Integrated servers for preparing, running, and analyzing CG simulations with Martini and SIRAH force fields [34] |

| MARTINI | Force Field | Coarse-Grained | Top-down approach; calibrated against thermodynamic data; generalizable for many biomolecules and materials [27] [25] |

| SIRAH | Force Field | Coarse-Grained | Used for nucleosome dynamics studies; employs a hybrid-resolution approach for different molecular parts [30] [27] |

| GENESIS-CG-tool | Toolbox | Input File Generator | Generates GROMACS-style input files for residue-level CG models of proteins and nucleic acids in a unified format [32] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Optimization Method | Force Field Refinement | Machine learning approach to refine CG force field parameters (e.g., Martini3) for specialized applications [25] |

| (S)-Azelastine | (S)-Azelastine, CAS:143228-85-7, MF:C22H24ClN3O, MW:381.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Scaff10-8 | Scaff10-8, MF:C22H18O6, MW:378.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic selection between All-Atom and Coarse-Grained MD simulations is pivotal for the success of research projects in polymer design and drug development. AAMD remains the gold standard for probing atomic-level interactions, such as specific ligand binding, where high resolution is non-negotiable. In contrast, CGMD is the method of choice for investigating large-scale phenomena—such as polymer self-assembly, chromatin folding, and membrane remodeling—over biologically relevant time and length scales. The emerging trend of multi-scale modeling, which integrates both approaches, is particularly powerful. For instance, one can use CGMD to simulate a large-scale event and then "backmap" the result to an all-atom representation for detailed analysis [28] [34]. Furthermore, machine learning methods like Bayesian Optimization are now being employed to refine CG force fields, enhancing their accuracy for specific polymer classes without sacrificing computational efficiency [25]. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each method and leveraging the protocols and tools outlined in this document, researchers can effectively harness the power of molecular dynamics to drive innovation in their fields.

Polymer bioconjugates represent a transformative class of biomaterials that integrate the functional specificity of biomolecules with the versatility of synthetic polymers. These hybrids leverage the biological activity, targeting capability, and catalytic functions of proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids, while polymers enhance stability, solubility, pharmacokinetics, and introduce stimulus-responsiveness. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational microscope, enabling researchers to probe the structure, dynamics, and interfacial interactions of polymer bioconjugates at atomic and mesoscopic scales. This protocol details the integrated application of atomistic and coarse-grained MD simulations for the rational design of polymer bioconjugates, specifically focusing on reduction-sensitive systems for intracellular drug delivery and protein-polymer conjugates synthesized via controlled radical polymerization. We provide comprehensive methodologies for model construction, simulation parameterization, and property prediction, supported by experimental validation techniques. The insights derived from these computational approaches accelerate the development of sophisticated bioconjugates for targeted therapeutic applications, reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming empirical screening.

The rational design of polymer bioconjugates for biomedical applications requires a fundamental understanding of the structure-property-function relationships that govern their performance in physiological environments. Molecular dynamics simulations provide a critical bridge between molecular structure and macroscopic behavior by simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. For polymer bioconjugates, this computational approach enables researchers to predict conformational dynamics, thermodynamic stability, and interaction patterns with biological components before undertaking complex synthetic procedures.

The design process typically involves multi-scale modeling strategies. Atomistic simulations provide detailed insights into specific intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, and van der Waals contacts at the bioconjugate interface. These simulations employ force fields like GAFF (General Amber Force Field) which have demonstrated success in reproducing liquid crystal phase transition temperatures and phase structures, making them suitable for complex polymeric systems [35]. For larger systems and longer timescales, coarse-grained (CG) models group multiple atoms into single interaction beads, dramatically reducing computational cost while maintaining essential physical characteristics. The integration of machine learning with CG molecular dynamics (CGMD) has further enhanced predictive capabilities by establishing monomer sequence-functional behavior relationships and enabling inverse design in undiscovered chemical space [12].

Table 1: Key MD Simulation Parameters for Polymer Bioconjugate Studies

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Typical Values/Ranges | Performance Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Parameters | Simulation Time Step | 1-2 femtoseconds (fs) [36] | Affects numerical stability; shorter steps increase accuracy but computational cost |

| Total Simulation Duration | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Determines observation of relevant biomolecular processes | |

| Ensemble Conditions | Temperature Control | 300-400K for biological systems [35] | Maintains physiological relevance or specific experimental conditions |

| Pressure Control | 1 bar (isotropic or anisotropic barostat) [35] | Ensures appropriate system density and periodic boundary conditions | |

| Force Field Selection | Atomistic Resolution | GAFF, AMBER, CHARMM [35] | Determines accuracy of intermolecular interaction modeling |

| Coarse-Grained Resolution | MARTINI, SDK, other custom force fields [12] | Balances computational efficiency with physical accuracy | |

| System Composition | Solvation Models | Explicit water (SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) | Critical for modeling hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions |

| Ion Concentration | Physiological salt conditions (0.15M NaCl) | Affects electrostatic screening and biomolecular stability |

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Fundamentals

Basic Principles and Force Fields

Molecular dynamics simulations operate on the fundamental principle of numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles. The core of any MD simulation is the force field - a mathematical expression comprising various energy terms that describe the potential energy of the system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. The total potential energy typically includes bonded terms (bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations) and non-bonded terms (van der Waals interactions described by Lennard-Jones potentials and electrostatic interactions described by Coulomb's law) [36].

For polymer bioconjugate systems, the selection of appropriate force field parameters is critical. The General Amber Force Field (GAFF) has shown particular utility for organic molecules and polymeric systems, with demonstrated ability to reproduce density and enthalpy of vaporization accurately [35]. Parameterization typically involves geometry optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of density functional theory (DFT) with atomic charges determined using the RESP method to ensure accurate electrostatic interactions [35].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Conventional MD simulations may struggle to access biologically relevant timescales for certain processes in polymer bioconjugates, such as large conformational changes or protein unfolding events. Enhanced sampling techniques address this limitation by modifying the underlying energy landscape or by running multiple simulations in parallel. Key methods include metadynamics and variationally enhanced sampling, which provide effective means for more precise potential energy calculations and simulations over longer timescales [36].

These techniques are particularly valuable for studying processes like the environmental responsiveness of reduction-sensitive bioconjugates, which contain disulfide linkages that remain stable in extracellular fluids but undergo rapid degradation in the reductive environment of intracellular compartments such as the cytoplasm and cell nucleus [37]. Enhanced sampling allows researchers to simulate these transition states and quantify the kinetic parameters governing stimulus-responsive behavior.

Application Notes: Reduction-Sensitive Bioconjugates

Design Rationale and Mechanisms

Reduction-sensitive biodegradable polymers and conjugates have emerged as particularly promising platforms for intracellular delivery of therapeutic agents. The design rationale typically involves incorporation of disulfide linkages in the main chain, at the side chain, or within cross-linkers [37]. These systems exploit the significant redox potential gradient between extracellular and intracellular milieus, with glutathione (GSH) concentrations approximately 100-1000 times higher in the cytoplasm than in extracellular fluids or circulation.

MD simulations enable researchers to model the structural dynamics of these reduction-sensitive systems under various redox conditions. By applying different redox potentials in simulations, researchers can predict degradation profiles, cargo release kinetics, and structural reorganization upon disulfide cleavage. These insights guide the strategic placement of disulfide linkages to optimize stability during circulation while ensuring rapid release upon reaching target intracellular compartments.

Simulation Protocol for Reductive Environment Modeling

System Setup:

- Initial Structure Preparation: Construct the polymer bioconjugate with disulfide linkages using molecular building tools. For atomistic simulations, ensure proper parameterization of sulfur-sulfur bonds and adjacent atoms.

- Solvation: Embed the bioconjugate in an explicit solvent box with appropriate dimensions (typically 1.0-1.5 nm padding around the solute). Use TIP3P or SPC water models.

- Ion Placement: Add ions to achieve physiological salt concentration (0.15M NaCl). Include specific counterions to neutralize system charge.

- Reductive Environment: To simulate intracellular conditions, incorporate glutathione molecules at appropriate concentrations (typically 1-10mM) [37].

Simulation Parameters:

- Force Field: Use GAFF or CHARMM for organic polymer components and standard protein force fields for biological segments.

- Temperature Coupling: Maintain 310K using Nosé-Hoover or Berendsen thermostats.

- Pressure Coupling: Use isotropic Parrinello-Rahman barostat at 1 bar.

- Electrostatics: Employ Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatic interactions.

- Constraint Algorithms: Apply LINCS or SHAKE algorithms to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

- Simulation Duration: Run production simulations for 100-500ns, depending on system size and observed dynamics.

Analysis Metrics:

- Distance Monitoring: Track sulfur-sulfur distances in disulfide bonds to identify cleavage events.

- Radius of Gyration: Measure polymer compaction or expansion upon reductive degradation.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area: Calculate exposure of hydrophobic domains during structural rearrangement.

- Interaction Energies: Quantize interactions between polymer components and therapeutic cargo during release process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Bioconjugate Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Bioconjugate Development | Simulation Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Radical Polymerization Agents | ATRP initiators, RAFT agents, CuBr₂/Me₆TREN [38] | Enable "grafting from" bioconjugate synthesis with controlled molecular weight and dispersity | MD parameters: bonding forces, repulsive forces, electrostatic forces [36] |

| Biomacroinitiators | BSA-Br, HSA-Br, enzyme-Br conjugates [38] | Provide protein platforms for polymer growth while maintaining biological function | Coarse-grained bead representation in MD; parameterization of protein-polymer interfaces |

| Stimulus-Responsive Monomers | Disulfide-containing monomers, pH-sensitive monomers | Confer environment-responsive degradation or structural changes | Enhanced sampling simulations of chemical transitions; free energy calculations |

| Characterization Standards | SEC standards, PAGE markers, NMR reference compounds | Enable accurate determination of bioconjugate structure and purity | Validation of simulation results against experimental hydrodynamic properties and structural data |

Application Notes: Protein-Polymer Bioconjugates

Synthesis Methodologies and Simulation Correlates

Protein-polymer bioconjugates are typically synthesized via "grafting to" or "grafting from" approaches. The "grafting to" method involves pre-synthesized polymers with end-group functionality that are conjugated to proteins, while "grafting from" approaches utilize immobilized initiators on protein surfaces to grow polymers directly from the biomacromolecule [38]. Recent advances in oxygen-tolerant photoinduced controlled radical polymerization have enabled quantitative yields of protein-polymer conjugates within 2 hours without damaging protein secondary structure [38].

MD simulations play a crucial role in optimizing these conjugation strategies by predicting:

- Accessibility of conjugation sites on protein surfaces

- Steric effects of growing polymer chains on protein structure and function

- Solvent accessibility changes upon polymer conjugation

- Thermodynamic stability of the resulting bioconjugates

For example, simulations of bovine serum albumin (BSA) conjugated with polystyrene via ATRP initiators have revealed how polymer grafting affects protein dynamics and surface properties [38]. These insights help guide the selection of conjugation sites that minimize disruption to biologically active regions while maximizing the beneficial effects of polymer attachment.

Protocol for Protein-Polymer Interface Modeling

System Construction:

- Initial Protein Structure: Obtain high-resolution crystal structure from Protein Data Bank or generate homology model.

- Polymer Attachment: Covalently link polymer chains to specified residues (typically cysteine, lysine, or tyrosine) using molecular editing tools.

- Solvation: Place the bioconjugate in a water box with dimensions ensuring minimal periodicity artifacts.

- Neutralization: Add appropriate counterions to neutralize system charge.

- Equilibration: Gradually relax the system through energy minimization and stepped equilibration.

Simulation Approach:

- Enhanced Sampling: For large conformational changes, employ metadynamics or replica exchange MD to improve sampling efficiency.

- Multiple Trajectories: Run parallel simulations with different initial velocities to improve statistical significance.

- Time Scales: Allocate sufficient simulation time (typically 100ns-1μs) to capture relevant protein and polymer dynamics.

Analysis Framework:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Monitor structural stability of protein core during simulation.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identify regions of increased flexibility upon polymer conjugation.

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Track preservation of α-helices and β-sheets using DSSP or similar algorithms.

- Contact Map Analysis: Quantify interfacial contacts between polymer and protein domains.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area: Calculate changes in protein surface exposure upon polymer attachment.

Advanced Integration with Machine Learning

The integration of machine learning with molecular dynamics simulations has created powerful new paradigms for polymer bioconjugate design. ML algorithms can identify complex patterns in high-dimensional simulation data that are difficult to discern through conventional analysis. Specifically, ML approaches enable:

Feed-forward property prediction: Establishing quantitative structure-property relationships between bioconjugate sequence/structure and functional behaviors such as drug release profiles, targeting efficiency, and biocompatibility [12].

Inverse design: Generating novel bioconjugate structures with desired properties by searching vast chemical space efficiently. For a polymer chain composed of thirty monomers of two types, the possibilities exceed 500 million configurations [12], making exhaustive simulation impossible but tractable through ML-guided exploration.

Accelerated sampling: Using ML-derived collective variables to enhance sampling of rare events, such as protein unfolding or polymer phase transitions.

Force field development: Employing neural networks to develop more accurate potential energy surfaces from quantum mechanical calculations.

The combination of CGMD and ML is particularly powerful for establishing monomer sequence-functional behavior relationships and guiding the design of sequence-specific polymers with superior properties [12]. This approach has been successfully applied to optimize polymeric configuration characterization, predict self-assembly behavior, and design biomaterials with tailored drug release profiles.

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Validation Techniques

Computational predictions require experimental validation to confirm their biological relevance. Key validation methods for polymer bioconjugates include:

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Determines hydrodynamic volume and molecular weight distribution, validating simulation predictions of bioconjugate size and shape [38].

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE): Assesses biomacromolecule mobility shifts upon polymer conjugation, corroborating simulation predictions of changes in hydrodynamic properties [38].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Confirms successful conjugation and provides information on local chemical environments, validating atomic-level interaction patterns observed in simulations.

Scattering Techniques (SAXS, SANS): Provide structural information on solution conformation and assembly states, offering direct comparison with simulation-derived structural models.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Monitors environmental responsiveness and cargo release, validating predicted stimulus-responsive behavior.

Therapeutic Implementation Case Study

A compelling example of computationally-guided bioconjugate development is the creation of fluorescent tumor-targeted polymer-bioconjugates for theranostic applications. Researchers have developed biotin-functionalized polymer bioconjugates (PFBT-B) that exhibit inherent fluorescence and tumor targeting capabilities [39]. These conjugates served as cytocompatible coatings for magnetite nanoparticles, enabling simultaneous magnetic hyperthermia, drug delivery, and fluorescence imaging.

MD simulations contributed to this development by:

- Predicting the optimal spacer length between targeting moieties and the polymer backbone

- Modeling the interaction between polymer coatings and nanoparticle surfaces

- Simulating pH-dependent drug release profiles that matched experimental observations (~6.64 μg drug/μg PFBT-B loading capacity with accelerated release in acidic environments) [39]

- Predicting preferential localization in cancer cells versus normal cells, later validated through cell studies

This integrated computational-experimental approach resulted in a multifunctional platform that successfully combined diagnostic capabilities with therapeutic intervention, demonstrating the power of rational design in advanced bioconjugate development.