Novel Polymer Materials: From Sustainable Discovery to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in novel polymer materials, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Novel Polymer Materials: From Sustainable Discovery to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

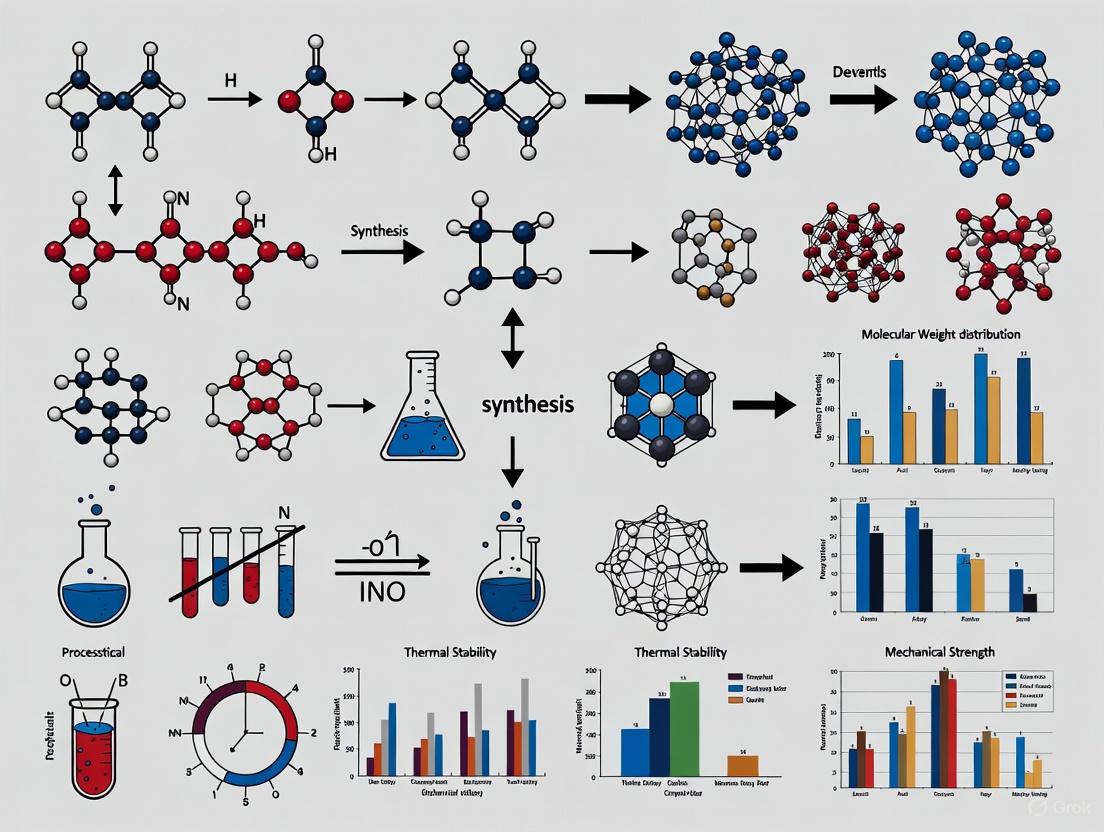

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in novel polymer materials, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational chemistry of emerging polymers, including sustainable alternatives, multilayer 3D structures, and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs). The scope extends to advanced synthesis methodologies, characterization techniques, and direct applications in controlled drug delivery, biomedical devices, and intelligent systems. The content also addresses key challenges in optimization and scalability, while offering comparative analyses of material performance to validate their potential in revolutionizing biomedical research and clinical applications.

Exploring the Next Generation: The Chemistry and Types of Novel Polymers

The field of polymer science is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the dual imperatives of environmental sustainability and advanced functionality. Novel polymer materials are no longer defined solely by their mechanical properties or cost-effectiveness but by their lifecycle impact and intelligent, adaptive behaviors. This evolution frames a new research paradigm where materials are designed from their inception for circularity, smart responsiveness, and application-specific performance. The integration of sustainability goals with cutting-edge polymer chemistry and processing techniques is paving the way for next-generation materials capable of addressing some of the most pressing global challenges in healthcare, energy, and environmental management [1] [2].

This whitepaper delineates the core principles and methodologies defining this new class of polymers. It explores the scientific foundation of sustainable feedstocks and end-of-life solutions, the engineering of polymers that respond dynamically to environmental stimuli, and the sophisticated characterization techniques required to understand their complex structures and behaviors. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this document provides a technical framework for the discovery and development of advanced polymeric materials, complete with experimental protocols, analytical tools, and data presentation standards essential for rigorous research in this rapidly advancing field.

The Pillars of Sustainable Polymer Design

Sustainable polymer design is built upon a multi-faceted strategy that encompasses the entire lifecycle of the material, from its origin to its ultimate fate. This approach is critical for reducing the environmental footprint of polymeric materials while maintaining the performance required for modern applications.

Bio-based and Renewable Feedstocks

The shift from petroleum-based monomers to feedstocks derived from biomass—such as plants, algae, and waste biological matter—represents a cornerstone of sustainable polymer science. These renewable raw materials not only decrease reliance on fossil fuels but can also offer novel chemical structures that lead to unique material properties. The challenge lies in developing efficient catalytic and metabolic pathways for the conversion of complex biomolecules into polymerizable monomers without incurring prohibitive energy costs or environmental damage [2].

Recyclability and Circular Economy Integration

Designing for circularity is paramount. This involves creating polymers that can be efficiently broken down and repurposed after use. Key strategies include:

- Mechanical Recycling: The physical reprocessing of plastics, which requires materials that can withstand multiple processing cycles without significant degradation of properties.

- Chemical Recycling: The depolymerization of plastics back to their monomers or other valuable chemicals, allowing for the production of new polymers of virgin quality. Innovative processes, such as the solid dielectric heatable coating for expanded polypropylene (ePP) that is reversible in hot water, exemplify this approach by enabling the recycling of complex welded components [2].

- Biodegradability: For applications where recycling is not feasible, designing polymers that can safely biodegrade in specific environments (e.g., industrial composting, marine environments) without leaving behind persistent microplastics or toxic residues [1].

The research highlights the importance of not demonizing traditional, fuel-based polymers but instead improving their circularity, as they remain essential for many high-performance applications in medicine, energy, and engineering [2].

Smart and Functional Polymer Systems

Smart polymers are engineered to exhibit significant, predetermined changes in their properties in response to subtle environmental stimuli. This responsiveness enables sophisticated functions for advanced technologies.

Table 1: Classes of Smart Polymers and Their Applications

| Stimulus | Polymer Class Example | Mechanism of Action | Potential Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) | Chain collapse/expansion at Lower/Upper Critical Solution Temperature (LCST/UCST) | Switchable filtration devices, drug delivery [3] |

| pH | Polyacids/Polybases | Protonation/Deprotonation alters chain charge & solubility | Oral drug delivery (responsive to gut pH) |

| Light | Azobenzene-containing polymers | Photo-isomerization induces mechanical stress | Optical data storage, micro-actuators |

| Chemical/Biomolecule | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Selective binding to tailored cavities | Sensors, selective extraction (e.g., PGA from urine) [2] |

A prime example of advanced functionality is the development of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs). As demonstrated by Jamoussi et al., a novel MIP for phenyl glyoxylic acid (PGA) was synthesized using a central statistical design. The MIP showed exceptional selectivity and affinity, with recoveries of 97.32% to 99.06% from urine samples and the potential for at least three reuses without significant performance loss [2]. This showcases the potential of smart polymers for precise chemical recognition and separation.

Furthermore, the modification of traditional materials with smart chemistry can yield significant improvements. The functionalization of historical violin varnishes with the cross-linking agent GLYMO resulted in enhanced durability, greater photostability, and improved scratch resistance, demonstrating the potential for smart modifications to preserve cultural heritage [2].

Essential Characterization Techniques for Novel Polymers

A thorough understanding of a polymer's chemical structure, morphology, and properties is critical for both research and development. Characterization is typically approached in tiers, from basic identification to deep de-formulation.

Table 2: Tiered Polymer Characterization Techniques

| Tier | Technique | Key Information Obtained | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier I | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Chemical functional groups, polymer type | Rapid identification of a generic polymer family (e.g., PP, PA) [4] |

| Tier II | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Glass transition (Tg), melting point (Tm), crystallinity | Determining processing temperatures and thermal stability. |

| Tier III | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Precolymer backbone structure, tacticity, copolymer composition | Deconstructing complex molecules like thermoplastic urethanes [4] |

| Tier III | Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and dispersity (Đ) | Relating molecular weight distribution to processability and mechanical performance [4] |

| Tier III | Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS, LC/MS) | Identification of low-concentration additives (e.g., antioxidants, slip agents) | Reverse-engineering a polymer's additive package at ppm levels [4] |

| Surface | Contact Angle Goniometry | Critical surface tension, surface free energy, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity | Predicting adhesion, coating, and biocompatibility [5] |

Tier III analysis is particularly crucial for understanding advanced and smart polymers, as it reveals the additives and subtle structural features that dictate their specialized performance. Techniques like NMR can construct the backbone structure, while GPC provides an exact measurement of molecular weight and distribution, which affects both processability and final mechanical properties [4]. For smart polymers, whose function often depends on specific interactions at the molecular level, this depth of analysis is indispensable.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Design of Experiments (DoE) for Polymerization Optimization

The conventional "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach to experimentation is inefficient and can fail to reveal critical interactions between process variables. Design of Experiments (DoE) is a powerful statistical method that systematically explores the entire experimental space to build predictive models and identify optimal conditions with minimal resource expenditure [3].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of a DoE-based optimization for a polymerization process, such as the RAFT polymerization of methacrylamide (MAAm) detailed in the search results [3].

Protocol: Optimizing a Thermally Initiated RAFT Polymerization using DoE [3]

- 1. Objective Definition: Define the target properties of the polymer. For a RAFT polymerization, this typically includes high monomer conversion, target molecular weight (Mn, th), and low dispersity (Đ).

- 2. Factor and Range Selection: Identify the numerical factors to be investigated and their high/low levels. For RAFT of MAAm, this includes:

- Factor A: Reaction Temperature (T)

- Factor B: Reaction Time (t)

- Factor C: Monomer-to-RAFT agent ratio (RM)

- Factor D: Initiator-to-RAFT agent ratio (RI)

- Factor E: Solids content in solvent (ws)

- 3. Experimental Design: Select an appropriate design, such as a Face-Centered Central Composite Design (FC-CCD), which efficiently explores the factor space and allows for the modeling of quadratic effects.

- 4. Polymerization Execution: Conduct all polymerizations as per the experimental design matrix.

- Materials: Methacrylamide (MAAm), RAFT agent (e.g., CTCA), thermal initiator (e.g., ACVA), solvent (e.g., water), and an internal standard for NMR (e.g., DMF).

- Procedure: a. Dissolve MAAm and CTCA in the solvent. b. Add the initiator (ACVA) via a stock solution. c. Add internal standard DMF. d. Homogenize the mixture and purge with N2 for 10 min. e. Stir the reaction vessel at the target temperature for the specified time. f. Quench the polymerization by rapid cooling and exposure to air. g. Sample for 1H NMR analysis to determine monomer conversion. h. Precipitate the polymer into ice-cold acetone, filter, and dry in vacuo.

- 5. Data Analysis and Modeling: Analyze the responses (conversion, Mn, Đ) for each experiment. Use statistical software to perform regression analysis and build a Response Surface Model for each output. The model will generate equations that predict the outcomes based on the factor levels.

- 6. Validation: Run additional experiments at the optimal conditions predicted by the model to validate its accuracy.

Protocol for Polymer Blend Compatibilization

Immiscible polymer blends require compatibilizers to improve interfacial adhesion and achieve desired properties.

- Objective: To enhance the properties of a 50/50 immiscible blend of isotactic Polypropylene (iPP) and Polyamide 6 (PA6).

- Materials: iPP, PA6, and interfacial agents like succinic anhydride-grafted atactic polypropylene (aPP-SASA or aPP-SFSA).

- Procedure:

- Dry both iPP and PA6 pellets thoroughly to prevent hydrolysis during processing.

- Pre-mix the iPP and PA6 pellets at a 50/50 ratio by weight.

- Add the interfacial agent (e.g., 2-5 wt% of the total blend).

- Compound the mixture using a twin-screw extruder or an internal mixer under controlled temperature and shear conditions.

- Injection mold the compounded material into test specimens under confined flow conditions.

- Analysis: Characterize the compatibilized blend using:

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): To observe shifts in the tan δ peaks, indicating improved interfacial adhesion [2].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): To analyze the morphology and reduction in domain size of the dispersed phase.

- Wide-Angle/Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS/SAXS): To investigate crystal morphology and confirm the absence of co-crystallization [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for research in novel polymer synthesis and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Polymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT/MADIX Agents | Mediate Controlled Radical Polymerization, enabling precise control over Mn and Đ. | Synthesis of well-defined block copolymers and smart materials like UCST polymers [3]. |

| Functional Monomers | Provide stimuli-responsiveness or specific chemical handles for post-polymerization. | Synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) for sensor applications [2]. |

| Cross-linking Agents | Increase network density, improving mechanical strength and chemical resistance. | Enhancing the durability of traditional varnishes (e.g., with GLYMO) [2]. |

| Interfacial Agents | Act as compatibilizers in immiscible polymer blends, reducing interfacial tension. | Stabilizing the morphology of iPP/PA6 blends for improved performance [2]. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters | Predict polymer solubility, swelling, and compatibility with solvents/other polymers. | Used in data tables to guide solvent selection for processing and analysis [5]. |

Data Presentation and Standardization

Effective communication of polymer research data requires clear and consistent presentation, especially for quantitative results.

Table 4: Key Quantitative Data from Cited Research

| Polymer System | Key Parameter | Reported Value | Experimental Condition | Characterization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMAAm (RAFT) | Monomer Conversion | 42.7% | RM=350, T=80°C, t=260 min | 1H NMR [3] |

| PMAAm (RAFT) | Theoretical Mn (Mn, th) | 12.8 kDa | RM=350, T=80°C, t=260 min | Calculation [3] |

| PMAAm (RAFT) | Apparent Mn | 6.2 kDa | RM=350, T=80°C, t=260 min | GPC [3] |

| PMAAm (RAFT) | Dispersity (Đ) | 1.0 (Target) | RM=350, T=80°C, t=260 min | GPC [3] |

| MIP for PGA | Analyte Recovery | 97.32 - 99.06% | Optimized MISPE conditions | HPLC [2] |

| MIP for PGA | Reusability Cycles | 3 | -- | HPLC [2] |

| iPP/PA6 Blend | Interfacial Agent | 2-5 wt% | 50/50 iPP/PA6 blend | DMA, WAXS/SAXS [2] |

For surface property characterization, data should be presented as the arithmetic mean with standard deviation and the number of data points (n) clearly indicated, as this accounts for variance across different methodologies and laboratories [5]. This practice is essential for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of research data, which is the bedrock of scientific advancement in polymer science.

The global plastics industry faces a pivotal challenge: reconciling the indispensable utility of polymers with their escalating environmental impact. Sustainable polymers—encompassing biobased, biodegradable, and recyclable solutions—represent a paradigm shift toward mitigating this impact. Framed within the context of novel polymer research, this transition is not merely a substitution of feedstocks but a fundamental reimagining of material design, functionality, and end-of-life. The drive for sustainability is catalyzed by the urgent need to defossilize the materials sector; approximately two-thirds of the total carbon footprint of plastics originates from the fossil carbon embedded within the polymer itself [6]. Without intervention, the embedded carbon from plastics production could reach three gigatonnes of CO₂ by 2050, profoundly impacting the remaining global carbon budget [6]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the current state, discovery methodologies, and applications of sustainable polymers, serving researchers and scientists dedicated to pioneering the next generation of materials.

Technical Foundations of Sustainable Polymers

Definitions and Key Concepts

- Biobased Polymers: Polymers derived from renewable biological resources, such as biomass. Their key identifier is the renewable carbon content, measurable via standards like ASTM D6866 [7]. It is critical to note that "biobased" does not inherently imply "biodegradable."

- Biodegradable Polymers: Materials capable of being broken down by microorganisms into natural byproducts like water, carbon dioxide, and biomass. This process depends on chemical structure more than the raw material source and occurs through specific biological and abiotic mechanisms [8] [7].

- Circular Economy: An industrial system that is restorative by design, aiming to eliminate waste and keep materials in continuous loops of use. For polymers, this integrates renewable feedstocks, design for recyclability, and effective end-of-life management to create closed-loop systems [9].

Mechanisms of Polymer Biodegradation

Biodegradation is a complex process influenced by polymer structure and environmental conditions. The primary mechanism occurs in three sequential stages [7] [10]:

- Biodeterioration: Abiotic environmental factors (heat, moisture, UV light) compromise the polymer's physical and chemical integrity, increasing surface area for microbial attack.

- Biofragmentation: Microorganisms secrete extracellular enzymes that cleave polymer chains into lower molecular weight fragments and oligomers.

- Assimilation: Microbial cells uptake these fragments and metabolize them for energy, producing final byproducts such as CO₂, H₂O, and CH₄.

The rate and extent of degradation are governed by factors including chemical composition, molecular weight, crystallinity, and environmental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, microbial consortia) [8] [7]. The diagram below illustrates this sequential process.

Major Classes of Sustainable Polymers: A Comparative Analysis

Sustainable polymers are categorized by their origin and biodegradability, each with distinct properties, trade-offs, and applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Sustainable Polymers [8] [11] [7]

| Polymer | Type (Bio-based/ Biodegradable) | Key Properties | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | Bio-based, Biodegradable | High strength, stiffness, clarity | Renewable sourcing, compostable | Brittleness, low heat resistance | Packaging, textiles, 3D printing |

| PHA (Polyhydroxy-alkanoates) | Bio-based, Biodegradable | Biocompatibility, versatile properties | Marine biodegradable, high biocompatibility | High production cost, complex processing | Biomedical, agriculture, packaging |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | Synthetic, Biodegradable | Low melting point, high elasticity | Easy to process, good blend compatibility | Low mechanical strength | Drug delivery, compost bags |

| Cellulose Derivatives (CA, CMC) | Bio-based, Biodegradable | Excellent film-forming, gas barrier | Abundant feedstock, good barrier properties | Moisture sensitivity | Films, coatings, encapsulation |

| Starch Composites | Bio-based, Biodegradable | Low cost, readily available | Low cost, highly biodegradable | Poor mechanical, high water permeability | Loose-fill packaging, bags |

Market Landscape and Growth Trajectory

The sustainable polymer market is experiencing dynamic growth, significantly outpacing the conventional polymer market. Current data and projections illustrate this trend.

Table 2: Global Market Overview and Projections for Bio-based Polymers [11] [12]

| Metric | Current Status (2024-2025) | Projection (2035) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Production Volume | ~4.2 million tonnes | 25-30 million tonnes | 13-15% |

| % of Total Polymer Production | ~1% | 4-5% | - |

| USA Market Value | USD 2.3 billion | USD 5.5 billion | 9.0% |

| Leading Application (by share) | Packaging (62%) | - | - |

| Fastest-growing Regional Market | - | - | West USA (10.4% CAGR) |

Advanced Discovery Methodologies for Novel Polymers

The discovery of new polymer materials is being revolutionized by high-throughput and computational approaches that dramatically accelerate the exploration of a vast chemical design space.

Autonomous Discovery Workflows

A cutting-edge approach involves closed-loop systems that integrate algorithmic design with robotic experimentation. As demonstrated by MIT researchers, one such platform can identify, mix, and test up to 700 polymer blends per day [13]. The workflow employs a genetic algorithm that treats polymer blend compositions as digital chromosomes, iteratively improving them based on experimental feedback. This method has proven particularly effective for optimizing properties like thermal stability for enzymes, where the best-performing blends often outperform their individual components [13]. The process is illustrated below.

AI and Machine Learning in Polymer Informatics

Beyond physical experimentation, in silico screening is becoming a powerful tool. Machine learning (ML) models, particularly feed-forward neural networks, are trained on existing polymer data to predict key properties such as thermal stability and dielectric performance before synthesis [14]. This approach allows for the high-throughput virtual screening of thousands of potential structures, prioritizing the most promising candidates for laboratory validation. The goal of these digital tools is to navigate the immense chemical space of potential polymers, a task that is "impossible in reasonable time with conventional methods" [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Sustainable Polymer Research

| Item | Function in R&D | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A benchmark biopolymer; often used as a base resin for blending and composite formation. | Packaging, 3D printing, biodegradation studies [8] [10]. |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Model bio-polyester for studying microbial production and true biodegradability in various environments. | Marine biodegradation, biomedical implants [8] [11]. |

| Chitosan (CN) | A natural biopolymer used to impart antimicrobial properties and improve film barrier performance. | Active food packaging, wound dressings [7] [10]. |

| Starch (SC) | A low-cost, renewable filler or matrix component for creating biodegradable composites. | Disposable packaging, agricultural films [7] [10]. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | A water-soluble cellulose derivative used for its film-forming and thickening capabilities. | Edible coatings, hydrogel matrices [7] [10]. |

| Compatibilizers | Chemicals added to improve adhesion between immiscible polymer phases in a blend. | Essential for creating high-performance PLA/starch or PLA/PHA blends [8] [7]. |

| Organic Peroxides | Free-radical initiators used to crosslink polymer chains, enhancing thermal and mechanical properties. | Improving heat resistance of biopolymers like PLA [7]. |

Applications and Performance in Key Sectors

Sustainable Packaging

Packaging is the largest application segment for sustainable polymers, accounting for approximately 62% of demand in the USA [12]. The primary drivers include regulatory pressure on single-use plastics and brand sustainability commitments. Biopolymers like PLA and PHA are used in rigid containers, flexible films, and coatings. A major research focus is overcoming inherent limitations such as inferior gas barrier properties and moisture sensitivity compared to conventional plastics like PET and PP [10] [6]. Strategies to enhance performance include:

- Nanocomposites: Reinforcing polymers with nano-sized clays or cellulose nanocrystals to improve barrier and mechanical properties.

- Multilayer Structures: Combining layers of different biopolymers to achieve a collective performance that a single material cannot, while maintaining overall compostability [9] [10].

Biomedical and Electronics Applications

The biocompatibility and controlled degradability of certain polymers make them ideal for advanced applications.

- Biomedical: PHAs and PLAs are used for resorbable sutures, drug delivery vehicles, and tissue engineering scaffolds [8] [7]. Their degradation rates can be tuned via molecular weight and crystallinity.

- Green Electronics: Research is exploring biodegradable polymers for transient electronics, triboelectric nanogenerators, and as dielectric materials in supercapacitors [8] [14]. For instance, machine learning has recently accelerated the discovery of polysulfates as excellent heat-resistant dielectric polymers for energy storage [14].

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant progress, several scientific and technical hurdles remain.

- Performance-Cost Trade-off: Balancing the mechanical/barrier properties and production cost of biopolymers to compete with incumbents [10] [6].

- Controlled Degradation: Ensuring predictable degradation rates under specific real-world conditions (e.g., marine, soil, industrial compost) remains a challenge [8] [7].

- End-of-Life Management: Confusion around terms like "biodegradable" and "compostable" leads to contamination in recycling streams. A clear regulatory framework and improved waste infrastructure are critical [10] [6].

- Scalable Production: Transitioning from lab-scale synthesis to cost-effective industrial manufacturing for novel polymers like PEF and PHAs [11].

Future research needs to focus on:

- AI-Driven Material Design: Fully leveraging machine learning for the inverse design of polymers with predefined properties [8] [15].

- Novel Feedstocks: Utilizing non-food biomass, CO₂, and waste streams as carbon sources for polymer production to enhance sustainability and reduce land-use impact [11] [6].

- Advanced Recycling: Developing chemical and enzymatic recycling pathways to handle biodegradable polymers and create a true circular economy [9].

The rise of sustainable polymers is an integral component of the global strategy to defossilize the materials sector and establish a circular economy. The field is rapidly evolving, driven by multidisciplinary research that combines traditional polymer science with breakthroughs in biotechnology, robotic automation, and artificial intelligence. While challenges in performance, cost, and end-of-life management persist, the convergence of technological innovation, regulatory support, and shifting market dynamics is creating unprecedented momentum. For researchers and scientists, this landscape offers a fertile ground for discovery, with the potential to develop novel polymer materials that meet the highest technical standards while aligning with the imperative of environmental sustainability.

The convergence of advanced polymer science and functional material design has catalyzed the emergence of multilayer three-dimensional (3D) polymers with controlled chiral properties. These architectures represent a paradigm shift in polymer materials research, moving beyond traditional linear polymers to complex 3D networks with precisely engineered interfaces and functionality gradients. Chirality, the geometric property of molecular non-superimposability on mirror images, plays a critical role in determining optical, mechanical, and biological interactions in polymeric systems [16]. The hierarchical emergence of chirality—from molecular building blocks to supramolecular assemblies—enables unprecedented control over material properties including optical activity, mechanical response, and molecular recognition capabilities [16].

This technical guide examines recent breakthroughs in the synthesis, characterization, and application of multilayer 3D chiral polymers, with particular emphasis on their implications for pharmaceutical development and advanced material systems. The integration of chiral control within multilayer 3D architectures establishes a foundation for next-generation smart materials with applications spanning drug separation membranes, optoelectronics, and biomedical devices [17] [18] [19].

Fundamental Chirality Concepts in Polymer Science

Hierarchical Chirality Manifestations

Chirality in polymeric systems manifests across multiple structural hierarchies, each contributing distinct functional attributes:

Central Chirality: Originates from stereogenic centers within monomeric building blocks, typically carbon atoms with four different substituents [16] [20]. This atomic-level asymmetry forms the foundation for higher-order chiral structures.

Backbone/Helical Chirality: Emerges from the constrained conformation of polymer main chains, forming helical structures with preferred handedness [16]. This secondary chirality directly influences macromolecular properties including optical activity and mechanical anisotropy.

Supramolecular Chirality: Arises from the organized self-assembly of multiple polymer chains into higher-order structures with chiral morphology [16]. This level of organization enables advanced functions such as chiral recognition and enantioselective transport.

Table 1: Hierarchical Manifestations of Chirality in Polymeric Systems

| Chirality Level | Structural Origin | Key Characterization Techniques | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Chirality | Stereogenic centers in monomers | Chiral HPLC, Optical Polarimetry | Determines fundamental interactions with biological systems |

| Backbone/Helical Chirality | Polymer chain conformation | Circular Dichroism (CD), VCD | Controls optical properties and mechanical anisotropy |

| Supramolecular Chirality | Chain assembly morphology | AFM-IR, Cryo-EM, Scanning Electron Microscopy | Enables chiral recognition and selective transport |

Pharmaceutical Significance of Chirality

The biological activity of chiral compounds exhibits profound stereodependence, where enantiomers can demonstrate dramatically different pharmacological profiles [21] [20]. This principle underpins regulatory preferences for single-enantiomer drugs, with approximately 40% of pharmaceuticals possessing chiral characteristics [18] [20]. Tragic historical examples, most notably thalidomide—where one enantiomer provided therapeutic effect while its mirror image caused severe birth defects—highlight the critical importance of chiral control in drug development [21] [20]. Beyond pharmacology, chiral polymers enable advanced separation technologies essential for producing enantiopure pharmaceuticals at industrial scales [18].

Synthesis of Multilayer 3D Chiral Polymers

Synthetic Approaches and Methodologies

Recent advances have established robust methodologies for constructing multilayer 3D polymers with controlled chirality:

Suzuki Cross-Coupling Polymerization: A pioneering approach utilizes 1,3,5-tris(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzene coupled with 1,8-dibromonaphthalene derivatives via 1,3,5-position coupling to generate multilayered 3D architectures [17]. This method enables precise spatial control over polymer growth, forming well-defined 3D networks rather than linear chains.

Chiral SuFEx Click Chemistry: Sulfur Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx) polymerization represents an emerging sustainable approach for creating chiral polymers with controlled stereochemistry [16]. This click-chemistry method facilitates the efficient assembly of chiral building blocks into high-molecular-weight polymers while maintaining enantiopurity.

Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Advanced fabrication techniques enable the direct printing of metal-polymer heterogeneous architectures with integrated functionality [22]. Methods such as Electrical Field-assisted Heterogeneous Material Printing (EF-HMP) allow precise metal patterning on polymer substrates at room temperature, creating composite structures with tailored properties [22].

Experimental Protocol: Suzuki Cross-Coupling Polymerization

Materials and Equipment:

- 1,3,5-Tris(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzene (316.8 mg, 0.8 mmol)

- 1,8-Dibromonaphthalene (228.8 mg, 0.8 mmol) or derivatives

- Palladium catalyst (Pd[S-BINAP]Cl₂, 32 mg, 0.04 mmol)

- Potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃, 439 mg, 3.2 mmol)

- Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 10 mL)

- Degassed water (2 mL)

- Schlenk line or argon/vacuum manifold

- Heated oil bath with temperature control

Procedure:

- Charge an oven-dried 50 mL round-bottom flask with boronic ester monomer, dibromonaphthalene monomer, palladium catalyst, and potassium carbonate under inert atmosphere.

- Add anhydrous THF and degassed water to the reaction vessel.

- Degas the reaction mixture via freeze-pump-thaw cycling (3 cycles) or argon purging.

- Heat the reaction at 88°C for 96 hours with continuous stirring.

- Cool the mixture to room temperature and precipitate into acidified methanol (HCl/MeOH).

- Isolate the polymer via Buchner funnel filtration, followed by sequential washing with methanol and water.

- Dry the resulting solid under vacuum to constant weight, yielding dark green polymeric product [17] [19].

Key Considerations:

- Strict exclusion of oxygen and moisture is critical for achieving high molecular weights.

- Chiral reaction conditions can be introduced through chiral ligands or chiral monomers to impart helicity to the polymer backbone.

- Molecular weight control can be achieved through monomer stoichiometry adjustments and reaction time optimization.

Table 2: Characterization Data for Synthesized Multilayer 3D Polymers

| Polymer | Yield (%) | Mw (Da) | Mn (Da) | PDI | [α]D²⁰ (in THF) | Reaction Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 54 | 10,168 | 9,867 | 1.030 | — | Achiral |

| 4 | 35 | 7,781 | 7,325 | 1.062 | -4° (c=0.1) | Chiral |

| 5 | 35 | 8,183 | 5,520 | 1.482 | — | Achiral |

| 6 | 41 | 5,235 | 4,153 | 1.261 | -5° (c=0.1) | Chiral |

Characterization Techniques for Chiral Polymers

Bulk Characterization Methods

Comprehensive characterization of multilayer 3D chiral polymers requires multi-modal analytical approaches:

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): Determines molecular weight distributions and polydispersity indices (PDI). Typical instrumentation includes TOSOH EcoSEC HLC-8420 GPC system with refractive index and UV detectors, using polystyrene standards for calibration [17] [19].

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Probes chiral organization at molecular and supramolecular levels through differential absorption of left and right circularly polarized light. CD provides critical information about helical secondary structures and their stability under varying environmental conditions [17] [16].

Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD): Extends CD principles to infrared region, enabling characterization of chiral structures through their vibrational transitions. VCD offers enhanced sensitivity to local stereochemical environments [16].

Chiral High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (Chiral-HPLC): The primary analytical method for determining enantiomeric purity and monitoring chiral inversion processes. This technique is essential for quality control in pharmaceutical applications [20].

Single-Molecule and Nanoscale Characterization

Advanced techniques now enable characterization at previously inaccessible length scales:

Atomic Force Microscopy with Infrared Spectroscopy (AFM-IR): Combines topographical imaging with chemical analysis at nanoscale resolution. Recent developments in acoustical-mechanical suppressed AFM-IR achieve single-chain sensitivity on non-metallic surfaces, enabling correlation between morphology and chemical structure [16].

Photothermal Infrared Nanospectroscopy: Allows chemical-structural analysis of individual polymer chains by detecting local thermal expansion induced by infrared absorption. This method has been crucial for identifying the hierarchical emergence of chirality from monomers to supramolecular assemblies [16].

Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Provides high-resolution (sub-nanometer) imaging of helical polymer structures under native conditions, though limited by computational reconstruction requirements and sampling constraints [16].

Pharmaceutical and Separation Applications

Chiral Separation Membranes

Solid chiral membranes represent a transformative technology for enantiomeric separation in pharmaceutical manufacturing:

Membrane Fabrication Methods:

- Direct Membrane Formation: Creating freestanding chiral polymeric films through solution casting or in-situ polymerization [18].

- Substrate Modification: Functionalizing existing membrane supports with chiral selectors through surface immobilization or grafting [18].

- Molecular Imprinting: Generating specific chiral recognition sites within polymer matrices complementary to target enantiomer geometry [18].

Separation Mechanisms:

- Direct Blocking: Selective exclusion of one enantiomer based on size and stereochemical compatibility [18].

- Promoted Transport: Facilitated diffusion of the preferred enantiomer through specific chiral interactions [18].

- Delayed Transport: Differential retardation of one enantiomer due to stronger interactions with chiral selectors [18].

Material Platforms:

- Cyclodextrin-Based Membranes: Utilize naturally chiral cyclodextrin cavities for enantioselective inclusion complex formation [18].

- Chiral Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs): Engineered crystalline porous materials with predetermined chirality for high-resolution separations [18].

- Biomimetic Polymer Membranes: Incorporate biological chiral selectors such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) or cellulose derivatives [18].

Drug Development Applications

The intersection of chiral polymers and pharmaceuticals manifests in several critical applications:

Enantiopure Drug Synthesis: Multilayer 3D chiral polymers serve as heterogeneous catalysts or reusable platforms for asymmetric synthesis, enabling efficient production of single-enantiomer pharmaceuticals [21] [20].

Drug Delivery Systems: Chiral polymer architectures provide platforms for controlled drug release with enantioselective delivery capabilities, potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects [21].

Analytical Separation Media: Chiral stationary phases based on multilayer 3D polymers offer enhanced resolution for analytical and preparative separation of enantiomers during drug development and quality control [18] [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chiral Polymer Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boronic Ester Monomers | Suzuki coupling precursors for 2D/3D polymer growth | 1,3,5-Tris(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzene | Key for 1,3,5-position coupling to create multilayered architectures [17] |

| Dihalo Aromatic Monomers | Cross-coupling partners in Suzuki polymerization | 1,8-Dibromonaphthalene, 1,8-Dibromo-2,7-dimethoxynaphthalene | Planar structures promote π-π stacking and ordered assembly [17] [19] |

| Chiral Ligands/Catalysts | Impart and control helicity in polymer backbones | Pd[S-BINAP]Cl₂, Chiral phosphines | Critical for achieving enantioselective polymerization [19] [16] |

| Chiral Selectors | Create enantioselective recognition sites | Cyclodextrins, BSA, Amino acids | Essential for fabricating chiral separation membranes [18] |

| Chiral HPLC Columns | Analyze enantiomeric purity | Cyclodextrin-based, Protein-based, Pirkle-type | Required for quality control of chiral polymers and separation efficiency [20] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of multilayer 3D chiral polymers continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions:

Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Advanced printing techniques enable the fabrication of heterogenous metal-polymer components with integrated functionalities [22]. Methods such as Electrical Field-assisted Heterogeneous Material Printing (EF-HMP) allow precise metal patterning on polymer substrates at room temperature, opening possibilities for chiral electronic devices and sensors [22].

Single-Molecule Characterization: Ultra-sensitive techniques like AFM-IR now enable chemical-structural analysis of individual polymer chains, providing unprecedented insights into the hierarchical emergence of chirality [16]. This capability is crucial for establishing definitive structure-property relationships in chiral polymer systems.

Sustainable Chiral Polymers: Emerging environmentally friendly polymerization methods, such as SuFEx click chemistry, offer sustainable routes to chiral polymers with controlled stereochemistry [16]. These approaches align with growing emphasis on green chemistry principles in materials research.

Advanced Separation Membranes: Continued innovation in chiral membrane technology addresses key challenges in pharmaceutical manufacturing, particularly through development of composite materials with enhanced selectivity and flux characteristics [18].

The integration of chiral control within multilayer 3D polymer architectures represents a frontier in advanced materials research with profound implications for pharmaceutical development, separation science, and functional materials design. As characterization techniques approach single-molecule resolution and synthetic methods achieve unprecedented stereochemical precision, this field promises to enable new generations of smart materials with tailored chiral functionality.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) as Biomimetic Recognition Platforms

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) represent a class of synthetic, biomimetic materials designed with specific recognition sites for target molecules, artificially created through a polymerization process in the presence of a molecular template [23] [24]. These polymers effectively mimic natural molecular recognition mechanisms, such as antibody-antigen interactions, offering a versatile and robust alternative to biological recognition elements [25] [26]. The growing demand for early and precise disease diagnosis, coupled with the need for reliable environmental monitoring, has positioned MIPs as a transformative solution in modern precision medicine and analytical science [25]. Their significance in the broader context of novel polymer materials research lies in their customizability, stability, and cost-effectiveness, providing a platform technology for diverse applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental remediation [27].

The fundamental principle behind molecular imprinting involves forming a polymer matrix around a target template molecule. Subsequent removal of this template leaves behind cavities that are complementary in shape, size, and functional group orientation, enabling the polymer to selectively rebind the target molecule [28]. This "lock and key" mechanism, first postulated by Emil Fischer, allows MIPs to recognize target molecules with high sensitivity and specificity, making them highly promising for numerous applications [23]. As research progresses, advancements in polymerization techniques, computational design, and sustainable materials are further enhancing the performance and scope of MIPs, solidifying their role as a critical component in the next generation of smart polymeric materials [29] [27].

Fundamental Principles and Synthesis of MIPs

Core Components and Molecular Recognition

The creation of a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer requires a precise combination of several key components, each playing a critical role in the formation of effective recognition sites. The process begins with a template molecule, which is the target analyte or a structurally similar analogue whose molecular features are to be imprinted [28]. Functional monomers are chosen for their ability to interact with the template via covalent, non-covalent, or semi-covalent bonds, forming a complex before polymerization [23]. The most common non-covalent interactions include hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects [28]. A cross-linker is incorporated to stabilize the template-monomer complex, impart mechanical stability to the polymer matrix, and create a rigid, porous three-dimensional structure that preserves the binding cavities after template removal [23]. The reaction is carried out in a porogenic solvent, which governs the porosity of the polymer and facilitates the diffusion of the template and other reagents. Finally, an initiator is used to start the polymerization reaction, which can be triggered by heat or light [23] [28].

The synthesis protocol follows a logical sequence, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Polymerization Methods

Various polymerization techniques are employed to synthesize MIPs, each conferring distinct morphological characteristics and suited for different applications [23].

- Bulk Polymerization: This is a conventional method where the template, functional monomers, cross-linker, initiator, and porogen are mixed in a solvent and polymerized via thermal or photo-initiation. The resulting monolithic polymer block is then ground, sieved, and the template is extracted. While simple, this method is time-consuming and produces irregularly shaped particles [23].

- Precipitation Polymerization: In this method, the monomer and initiator are dissolved in a solvent without stabilizers, leading to the precipitation of spherical MIPs as the polymer chains grow and become insoluble. This technique yields uniform, spherical particles in the nanometer to micrometer range [23].

- Suspension Polymerization: This is a one-step radical polymerization process where the pre-polymerization mixture (dispersed phase) is suspended as droplets in a continuous aqueous phase, often stabilized by a suspending agent like polyvinyl alcohol. It results in spherical MIP beads and allows control over particle size and porosity through the amount of porogen used [23].

- Emulsion Polymerization: This technique involves radical polymerization within micelles formed in an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion system. A key difference from suspension polymerization is the use of a water-soluble initiator, which must diffuse into the micelles to initiate the reaction. Emulsion polymerization typically produces spherical nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 10 to 100 nm [23].

Table 1: Common Reagents for MIP Synthesis [23]

| Component Type | Example Reagents |

|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Methacrylic acid (MAA), 4-Vinylpyridine, Acrylamide, N-Vinylimidazole |

| Cross-linkers | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), Divinyl benzene, N,N'-Methylenebis(acrylamide) |

| Initiators | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), Ammonium persulfate, Benzoyl peroxide |

| Porogenic Solvents | Acetonitrile, Toluene, Chloroform |

Computational Design and Rational Development

The traditional trial-and-error approach to MIP development is increasingly being supplanted by rational design strategies leveraging computational chemistry. This shift addresses the challenge of optimizing the numerous components and parameters involved in the imprinting process, which otherwise demands substantial resources [30]. Computational modeling now plays a pivotal role in predicting the behavior of the pre-polymerization mixture and selecting optimal components for a highly efficient MIP [30].

Quantum Chemical (QC) Calculations and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

Quantum Chemical (QC) Calculations are used at the initial stage to screen functional monomers and predict their interaction with the template molecule. By optimizing the geometries of the template and monomers and performing natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis, researchers can calculate the binding energy (∆Ebind) of different template-monomer complexes [30]. For instance, a study on sulfadimethoxine (SDM) found that carboxylic acid monomers like trifluoromethylacrylic acid (TFMAA) formed complexes with a high binding energy of -91.63 kJ/mol, indicating a stable pre-polymerization complex [30]. QC calculations help identify the most probable binding sites and the strongest-interacting monomers before any experimental work begins.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations build upon QC data by modeling the dynamic behavior of the entire pre-polymerization system in an explicit solvent. MD simulations can reveal how many monomer molecules can effectively bind to a single template and analyze hydrogen bond formation from perspectives such as hydrogen bond occupancy and radial distribution function (RDF) [30]. Recent research has defined quantitative parameters from MD simulations to evaluate imprinting efficiency:

- Effective Binding Number (EBN): The number of monomer molecules effectively bound to the template.

- Maximum Hydrogen Bond Number (HBNMax): The maximum number of hydrogen bonds formed between the template and monomers [30]. Higher values of EBN and HBNMax indicate a higher effective binding efficiency, guiding the selection of the optimal template-to-monomer ratio. For example, for SDM, MD simulations suggested that only two monomer molecules could bind to one template molecule, leading to an experimentally validated optimal molar ratio of 1:3 [30].

The synergy between computational and experimental methods is key to modern MIP development, as shown in the following logical flow.

Advanced MIP Formats and Applications

MIPs in Sensing and Clinical Diagnostics

The application of MIPs in sensing, particularly for clinical biomarker detection, has seen remarkable growth from 2021 to 2025 [25]. MIP-based sensors enhance the sensitivity and specificity of typical optical and electrochemical platforms by providing precise binding to analytes of choice in complex biological samples like serum, urine, and blood [25] [23]. They are employed in the detection of a wide array of clinically relevant targets:

- Cancer Biomarkers: Detection of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA), Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP), Cancer Antigen 15-3 (CA15-3), and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER-2) [26].

- Cardiac Biomarkers: Monitoring of Cardiac Troponin I (cTnI) for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) for heart failure [26].

- Neurodegenerative Disease Biomarkers: Detection of proteins associated with Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [26].

- Viruses and Proteins: Development of sensors for direct detection of hepatitis C virus envelope protein and SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [25] [26].

A significant advancement in this area is the use of epitope imprinting for large biomolecules like proteins. Instead of imprinting the whole protein, which is costly and can lead to conformational issues, this method uses a short, characteristic peptide fragment (epitope) of the protein as the template [24]. This approach creates binding sites that selectively recognize the entire protein, offering improved binding affinity, specificity, and ease of template removal compared to whole-protein imprinting [24].

MIPs in Environmental Remediation and Other Fields

MIPs play a substantial role in addressing environmental hazards and chemical contaminants. Their high selectivity makes them ideal for the extraction and sensing of various pollutants in water [28] [27]:

- Pesticides: Malathion, chlorpyrifos, diazinon, and carbamates.

- Heavy Metals: Lead (Pb(II)) and zinc (Zn(II)) ions, often using ion-imprinted polymers (IIPs), a subset of MIPs [27]. One Pb(II)-IIP exhibited an adsorption capacity of 41.83 mg·g⁻¹ [27].

- Pharmaceutical Pollutants: Antibiotics, analgesics, hormones, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) like estradiol [27]. A composite nanofiber MIP for 17β-estradiol showed a fast binding capacity of 160.05 µg·g⁻¹ [27].

- Other Pollutants: Dyes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Beyond sensing and environmental cleanup, MIPs are extensively used in chromatographic separation as stationary phases for the selective separation of enantiomers and other chemically similar compounds [28]. They are also explored in drug delivery systems for the controlled release of therapeutics [23] [28] and in catalysis, where they create tailored active sites that mimic enzymatic catalysis [29].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Sustainable and Biomass-Based MIPs

A prominent trend in MIP research is the move toward sustainability through the development of biomass-based MIPs (bio-based MIPs) [29]. These polymers are derived from biological resources and are characterized by their environmentally friendly properties, low cost, and abundant active functional groups. Bio-based MIPs are mainly categorized into:

- Biomass-derived carbon-based MIPs

- Polysaccharide-based MIPs (e.g., using chitosan, cellulose) [29].

The design strategies for these green MIPs emphasize computational modelling, controlled morphology, and stimuli-responsive design. Their applications are rapidly expanding into food analysis, biomedicine, environmental remediation, and catalysis, contributing to the creation of greener and more sustainable analytical methods [29].

Commercialization Challenges and Outlook

Despite a marked increase in scientific publications and proven potential in academic research, the commercialization of MIP-based sensors and devices remains limited [31]. Key challenges that need to be addressed to bridge this gap include:

- Classification and Standardization: There is ongoing debate and confusion in the literature regarding the classification of MIPs as chemosensors or biosensors, which needs resolution [31].

- Performance in Complex Media: Enhancing the performance and reliability of MIPs in real-world, complex samples like blood or wastewater is crucial.

- Scalability and Reproducibility: Developing manufacturing processes that ensure large-scale production with consistent quality is essential for commercial viability.

- Collaboration: Future progress hinges on more robust collaboration between academia and industry to translate laboratory innovations into marketable products [31].

The future research direction will likely focus on integrating MIPs with other advanced nanomaterials like graphene and carbon nanotubes to improve sensitivity, further leveraging computational tools for rational design, and expanding the library of templates for new and emerging analytes [27] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for MIP Research and Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in MIP Development | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Interact with template to form pre-polymerization complex; define chemical complementarity of binding sites. | Methacrylic acid (MAA; for H-bonding/basic groups), 4-Vinylpyridine (for acidic templates), Acrylamide (for polar templates) [23] [30]. |

| Cross-linkers | Stabilize the polymer matrix; create rigid structure to preserve binding cavities after template removal. | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA; common for methacrylate polymers), Divinyl benzene (for styrene-based systems) [23]. |

| Initiators | Generate free radicals to initiate the polymerization reaction. | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN; thermal initiator), Ammonium persulfate (APS; often used with TEMED for redox initiation) [23]. |

| Porogenic Solvents | Dissolve all components and create pore structure during polymerization; control morphology. | Acetonitrile (common for non-covalent imprinting), Toluene. Choice affects porosity and surface area [23] [30]. |

| Computational Software | Model pre-polymerization mixtures; predict optimal monomers/template ratios; calculate binding energies. | QC software (Gaussian), MD simulation packages (GROMACS). Used to define parameters like EBN and HBNMax [30]. |

Key Drivers and Global Market Trends in Polymer Innovation

The field of polymer science is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by the dual engines of sustainability demands and advanced manufacturing technologies. The global polymers market, poised to grow from approximately $685 billion in 2025 to over $1.1 trillion by 2035, reflects this dynamism, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 5.1% [32]. Innovation is no longer confined to traditional material properties but is increasingly defined by smart, responsive behaviors and data-driven discovery. Researchers are developing polymers that are not only high-performing but also capable of self-healing, shape-shifting, and adapting to environmental stimuli [33]. Concurrently, methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) and machine learning are revolutionizing research workflows, accelerating the design of novel polymers for applications ranging from drug delivery to energy storage [34] [35]. This whitepaper examines the key drivers, market trends, and cutting-edge experimental methodologies that are framing the discovery of novel polymer materials within a broader thesis context.

The polymer industry's growth is underpinned by its critical role in diverse sectors, with regional variations and material segments evolving at different paces.

Market Size and Projections

Table 1: Global Polymers Market Size and Growth Projections (2025-2035)

| Year | Market Size (USD Billion) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 685.0 [32] | Base year for projection. |

| 2030 | 879.3 [32] | Contributing 44.2% of total decade-long growth. |

| 2035 | 1,126.5 [32] | Total growth of 64.2% from 2025; CAGR of 5.1%. |

Table 2: Alternative Market Size Projections (2024-2034) [36]

| Year | Market Size (USD Billion) | CAGR |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 796.53 | - |

| 2034 | 1,351.59 | 5.43% |

Primary Market Drivers

- Sustainability and the Circular Economy: Regulatory pressure and environmental responsibility are pushing manufacturers toward bio-based polymers, biodegradable materials, and advanced recycling technologies [37] [32] [36]. This includes the development of polymers from biomass and the creation of chemical recycling methods for a closed-loop system.

- Demand from Key Industries:

- Packaging: The dominant application segment, accounting for approximately 35% of polymer consumption in 2025, is fueled by e-commerce expansion and the need for protective, lightweight materials [32] [36].

- Automotive and Transportation: The industry's shift toward lightweighting to improve fuel efficiency and reduce emissions is a significant driver for high-performance polymers [32].

- Medical Devices: This segment is experiencing the fastest growth, driven by demand for high-performance, biocompatible polymers used in surgical instruments, implants, and drug delivery systems [36].

- Advanced Manufacturing and Digitalization: The integration of Industry 4.0 technologies—including AI, robotics, and IoT—is enhancing production efficiency, enabling predictive maintenance, and facilitating rapid customization [37]. Furthermore, data-driven polymer design using machine learning is shortening the traditional 15-25 year development cycle for new materials [35].

- Supply Chain Resilience: Recent global disruptions have accelerated a push toward reshoring and regionalizing supply chains. This trend benefits manufacturers who can provide reliable, locally-produced polymer components, particularly for critical sectors like healthcare [37].

Emerging Trends in Polymer Innovation

Beyond market forces, scientific breakthroughs are defining the next generation of polymeric materials.

Responsive and "Smart" Materials

These materials are engineered to sense and react to external stimuli, opening new frontiers in robotics and medicine:

- Shape-Morphing Polymers: Researchers have developed bistable polymer structures, akin to "Chinese lanterns," that can snap between distinct 3D shapes. These structures store and release energy, making them suitable for soft robotics applications like grippers that can capture small objects or control fluid flow [33].

- Self-Healing Composites: Inspired by human skin, new thermoplastics are being reinforced with 3D-printed healing agents. When damage occurs, embedded heating layers can be activated to melt the healing agent, flowing into cracks and microstructures. This process has been demonstrated to be effective for at least 100 repair cycles, significantly enhancing material lifetime [33].

- Energy-Generating Textiles: Exploratory research involves modifying textiles with amphiphiles to generate electricity from friction. Proof-of-concept tests have shown the ability to generate up to 300 volts from a small piece of material, potentially powering wearable electronics while improving wearer comfort [33].

Sustainable and Functional Polymers

- CO2-Utilizing Coordination Polymers: A novel development involves highly porous coordination polymers (MOFs) that adsorb carbon dioxide and simultaneously act as green catalysts. The adsorbed CO2 reacts with epoxides (which can be derived from biomass) to produce valuable organic carbonates, used in electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries and as green solvents. This process achieves 100% atomic efficiency, representing a waste-free method for CO2 utilization [38].

- Chemically Recyclable Polymers: Research efforts are increasingly focused on designing polymers with built-in chemical "recycling points." This allows the materials to be efficiently broken down into their constituent monomers after use, enabling true chemical recycling and reducing plastic waste [39].

Data-Driven Polymer Design

The traditional trial-and-error approach to polymer development is being supplanted by informatics. The central challenge is the astronomically large combinatorial sequence space of polymers; for example, a simple AB copolymer with 50 units has over 10^15 possible sequences [35]. Data-driven methods address this via:

- Polymer Featurization: Representing polymer structures in machine-readable numerical formats, such as SMILES strings or other molecular fingerprints, is the foundational step for any computational analysis [35].

- Machine Learning (ML) and Prediction Models: ML models are trained on existing experimental or simulation data to predict polymer properties, dramatically accelerating the screening of new candidate materials [35].

- High-Throughput Simulations: Molecular simulation packages (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS for classical mechanics; VASP for quantum chemistry) are used to rapidly generate large volumes of property data for training these ML models [35].

Experimental Protocols in Modern Polymer Research

To illustrate the evolution of research methodologies, this section details two key experimental approaches: the statistical optimization of polymerizations and the fabrication of novel functional materials.

Protocol 1: Optimizing a RAFT Polymerization Using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Objective: To systematically optimize a thermally initiated Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) polymerization of methacrylamide (MAAm) to achieve target molecular weights and low dispersity (Ð), moving beyond the inefficient "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach [34].

Background: RAFT polymerization is a versatile controlled radical technique for synthesizing complex polymer architectures. Key factors influencing the outcome include temperature, time, and reactant concentrations [34].

Methodology:

Factor Selection: Identify the numeric factors to be optimized. In this case:

- Reaction Temperature (T)

- Reaction Time (t)

- Monomer-to-RAFT agent ratio (R~M~) - primarily controls molecular weight.

- RAFT agent-to-Initiator ratio (R~I~) - impacts initiator efficiency and livingness.

- Total monomer concentration (w~s~) - the weight fraction of solids in the solvent.

Experimental Design: A Face-Centered Central Composite Design (FC-CCD) is employed under the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) framework. This design efficiently explores the multi-dimensional factor space and models nonlinear responses and factor interactions.

Polymerization Procedure:

- Formulation: Precisely weigh MAAm, the RAFT agent (e.g., CTCA), and solvent (e.g., water) into a reaction vial. The masses are calculated based on the designed R~M~ and w~s~ values.

- Initiator Addition: Add the thermal initiator (e.g., ACVA) using a micropipette from a stock solution to achieve the desired R~I~. Add an internal standard (e.g., DMF) for subsequent conversion analysis via ^1^H NMR spectroscopy.

- Reaction Execution: Homogenize the mixture, purge with N₂ to remove oxygen, and place the sealed vial in a pre-heated thermal block for the designated time and temperature.

- Analysis: Terminate the reaction and analyze monomer conversion via ^1^H NMR. Determine the molecular weight and dispersity of the purified polymer using Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC).

Data Modeling and Optimization: The experimental data for responses (conversion, M~n~, Ð) are fitted to mathematical models. These prediction equations allow researchers to identify the optimal combination of factor levels for any desired synthetic outcome without further exhaustive experimentation [34].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of CO2-Utilizing Coordination Polymers

Objective: To fabricate a highly porous coordination polymer capable of adsorbing CO₂ and subsequently catalyzing its conversion into cyclic organic carbonates [38].

Background: This protocol describes the synthesis of a functional metal-organic framework (MOF) material that contributes to a circular carbon economy.

Methodology:

Synthesis of the Coordination Polymer:

- Reagents: 1,4-Naphthalenedicarboxylic acid, 4-aminotriazole (or 5-aminotetrazole), and aluminum ion clusters.

- Procedure: Combine the reagents in a suitable solvent system. The synthesis is described as simple, environmentally safe, and low-cost, resulting in highly porous crystalline structures with a specific surface area of 400–700 m²/g [38].

CO2 Adsorption:

- The synthesized polymer, in powder or compressed pellet form, is exposed to a stream of air or flue gas (e.g., from industrial production or power plants).

- The material strongly adsorbs CO₂ into its porous structure, analogous to a water sponge.

Catalytic Conversion of CO2:

- Reactor Setup: Transfer the CO₂-loaded polymer catalyst to a chemical reactor.

- Reaction: Introduce an epoxide (e.g., ethylene oxide, or biomass-derived epoxides like limonene oxide) into the reactor.

- The polymer acts as a highly selective catalyst, facilitating the reaction between the adsorbed CO₂ and the epoxide to form a cyclic organic carbonate.

- Conditions: The reaction proceeds with 100% atom efficiency and does not require toxic substances [38].

Catalyst Recovery and Reuse: After the reaction, the polymer catalyst can be easily recovered via filtration or centrifugation. It demonstrates stability up to 400°C and can be reused multiple times without losing its catalytic properties [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Polymer Research

| Item | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agents (e.g., CTCA) | Mediate controlled radical polymerization, enabling precise control over molecular weight and architecture. | Synthesis of block copolymers for smart materials like nanocarriers [34]. |

| Functional Monomers (e.g., Methacrylamide) | Building blocks for polymers with specific properties, such as Upper Critical Solution Temperature (UCST) behavior. | Creating "smart" responsive polymers [34]. |

| Thermal Initiators (e.g., ACVA) | Decompose upon heating to generate free radicals, initiating the polymerization reaction. | Thermally initiated RAFT polymerizations [34]. |

| Coordination Polymer Linkers (e.g., 1,4-Naphthalenedicarboxylic acid) | Organic molecules that connect metal clusters to form porous Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). | Fabrication of CO2-adsorbing and catalytic polymers [38]. |

| Epoxides (e.g., Limonene Oxide) | Reactive cyclic ethers that act as substrates for reactions with CO₂. | Production of cyclic organic carbonates using captured CO2 [38]. |

| Liquid Metal Droplets (e.g., Eutectic Gallium-Indium) | Conductive, self-healing materials for creating self-assembling electronic patterns. | Research into self-assembling electronic devices and circuits [33]. |

| Ferromagnetic Elastomers | Rubber-like materials filled with magnetic particles, enabling remote actuation. | Development of soft actuators for origami robots in biomedical applications [33]. |

| Healing Agent (Thermoplastic) | A material that flows upon heating to repair damage in a composite matrix. | Components of self-healing composites for extended product lifecycles [33]. |

Synthesis and Implementation: Techniques and Drug Delivery Applications

The discovery of novel polymer materials is pivotal for advancing numerous technological and biomedical fields. Within this research domain, two advanced synthesis methods—Pickering emulsion and controlled radical polymerization (CRP)—have emerged as powerful and versatile techniques. Pickering emulsion utilizes solid particles to create stabilized emulsions with exceptional stability and biocompatibility, making it highly suitable for applications like biocatalysis and drug delivery [40]. Concurrently, controlled radical polymerization techniques provide unprecedented command over polymer architecture, molecular weight, and functionality, enabling the synthesis of sophisticated polymer nanostructures for targeted therapeutic applications [41]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on these two methodologies, detailing their fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and characterization techniques, framed within the context of novel polymer material discovery for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Controlled Radical Polymerization (CRP) for Polymer Nanostructures

Principles and Design Considerations

Controlled radical polymerization represents a suite of techniques that allow for the precise synthesis of polymers with well-defined nanostructures, including star polymers, polymer brushes, and hyperbranched polymers [41]. These methods, such as Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) and Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) polymerization, provide superior control over nanoscale size, morphology, and composition compared to traditional free-radical polymerization. This precision is critical for designing drug delivery systems, as the physical properties of the nanoparticle carrier—including its size, surface charge, and architecture—directly influence its pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and therapeutic efficacy [41].

A primary design goal for anticancer drug delivery vehicles is to leverage the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, a form of passive targeting that exploits the leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage of solid tumors [41]. To utilize the EPR effect effectively, carriers must maintain a plasma concentration for over six hours, which requires a size above the renal clearance threshold (typically >40 kDa or >5 nm in diameter) and the ability to avoid the reticuloendothelial system (RES) [41]. Key design parameters include:

- Size: Vehicles smaller than approximately 50 nm in diameter demonstrate the most effective tumor penetration, while larger vehicles are often restricted to the perivascular space [41].

- Surface Charge: Neutral or slightly negatively charged particles typically exhibit improved tumor penetration compared to cationic counterparts, which interact more strongly with the anionic cell membranes and extracellular matrix [41].

- Stealth Properties: Modification with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) at high grafting density (creating a "brush" conformation) is a common strategy to reduce opsonization and prolong circulation half-life [41].

Active targeting through ligands such as folate, transferrin, or antibodies can further improve tumor accumulation. The selection of these ligands requires careful consideration of their binding affinity, size, ease of synthesis and conjugation, and ability to mediate receptor-mediated endocytosis [41].

Quantitative Comparison of CRP Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major CRP techniques and one related metal-catalyzed method for synthesizing polymer nanostructures.

Table 1: Controlled Polymerization Techniques for Advanced Polymer Architectures

| Polymerization Technique | Full Name | Key Features | Common Initiators/Catalysts | Typical Polymer Architectures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATRP | Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization | Uses a halogen atom transfer mechanism with a metal catalyst (e.g., Cu complexes); excellent control over MW and PDI. | Alkyl halides, Cu(I)/Ligand complexes | Block copolymers, star polymers, polymer brushes |

| RAFT | Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer | Employs chain-transfer agents (thiocarbonylthio compounds); versatile for a wide range of monomers. | Thiocarbonylthio compounds (e.g., dithioesters) | Block copolymers, hyperbranched polymers, micelles |

| ROMP | Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization | Not a radical process; based on metal-catalyzed alkene metathesis; suitable for strained cyclic olefins. | Ruthenium carbene complexes (e.g., Grubbs' catalyst) | Macrocyclic polymers, functionalized polymers |

| NMP | Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization | Uses a stable nitroxide radical as a controlling agent; simple system without metal catalyst. | Alkoxyamines (e.g., TEMPO-based compounds) | Block copolymers, graft copolymers |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of a Drug-Loaded Star Polymer via ATRP

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a star-shaped polymer nanoparticle for drug delivery, incorporating a hydrophobic core for drug encapsulation and a PEG shell for stealth properties.

Materials:

- Monomer: Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (PEGMA, 1.0 g).

- Crosslinker: Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 0.1 g).

- Initiator: Ethyl α-bromoisobutyrate (EBiB, 5.0 mg).

- Catalyst: Copper(I) bromide (CuBr, 3.0 mg).

- Ligand: N,N,N',N'',N''-Pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA, 7.0 µL).

- Solvent: Anisole (5 mL).

- Drug Model: A hydrophobic anticancer drug (e.g., Paclitaxel, 50 mg).

Procedure:

- Schlenk Line Setup: Conduct all steps under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) using a Schlenk line or glovebox to prevent catalyst deactivation by oxygen.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: In a Schlenk tube, dissolve the PEGMA monomer, EGDMA crosslinker, EBiB initiator, and the drug model in anisole. Seal the tube with a rubber septum.

- Degassing: Degas the solution by performing at least three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Catalyst Addition: In a separate vial, combine CuBr and PMDETA ligand with a small amount of anisole to form the catalyst complex. Degass this catalyst solution briefly.

- Polymerization Initiation: Using a gas-tight syringe, transfer the catalyst solution to the main Schlenk tube under a positive pressure of inert gas. Place the reaction vessel in an oil bath pre-heated to 70°C and stir vigorously.

- Reaction Monitoring: Allow the polymerization to proceed for 6-8 hours. Monitor monomer conversion by periodically sampling the reaction mixture and analyzing it via ( ^1H ) NMR spectroscopy or gel permeation chromatography (GPC).

- Reaction Termination: After the desired conversion is reached, stop the reaction by rapidly cooling the Schlenk tube in an ice bath and exposing the contents to air.

- Purification: Pass the crude mixture through a neutral alumina column to remove the copper catalyst. Precipitate the purified star polymer into cold diethyl ether or hexane. Isolate the polymer by filtration or centrifugation.

- Drying: Dry the final product under vacuum overnight to obtain a solid powder. The drug loading can be determined using techniques such as UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC.

Characterization Data for Polymer Nanostructures

After synthesis, the resulting polymer nanostructures must be thoroughly characterized to confirm their suitability for drug delivery applications.

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for Polymer Nanostructures

| Characterization Technique | Parameter Measured | Target Value/Outcome for Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Molecular weight (MW) and dispersity (Đ) | Đ < 1.3 indicates good control; MW tailored for >40 kDa to avoid renal clearance [41]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter, size distribution | Size < 50 nm for optimal tumor penetration [41]; low polydispersity index (PDI). |