Optimizing Polymer Extrusion: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Process Control for Enhanced Product Quality

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing polymer extrusion processes, a critical manufacturing step for biomedical devices and drug delivery systems.

Optimizing Polymer Extrusion: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Process Control for Enhanced Product Quality

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing polymer extrusion processes, a critical manufacturing step for biomedical devices and drug delivery systems. It explores the fundamental principles of single and twin-screw extrusion, details advanced methodological approaches including statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) and computational modeling, and offers practical troubleshooting for common defects like melt fracture and sharkskin. A comparative analysis of optimization and validation techniques demonstrates how to achieve superior product consistency, energy efficiency, and controlled release properties essential for clinical applications.

Core Principles of Polymer Extrusion: Understanding the Machinery and Material Science

Extrusion technology is a cornerstone of modern polymer processing, serving as a critical tool for researchers and scientists in material science and pharmaceutical development. This continuous process transforms raw polymeric materials into structured products through melting, mixing, and shaping operations. The selection of appropriate extrusion equipment—specifically single-screw or twin-screw extruders—directly influences critical research outcomes including drug bioavailability in solid dispersions, composite material properties, and process scalability. Within research contexts, extrusion has evolved from a simple shaping technology to a sophisticated platform for reaction engineering, nanomaterial production, and advanced drug delivery system fabrication. This technical guide provides a comparative analysis of extruder mechanisms and applications, supplemented with troubleshooting and methodological support for research scientists optimizing polymer-based processes, particularly in pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Single-Screw Extruder Mechanism

The single-screw extruder operates on a relatively straightforward principle of drag-induced flow and viscous dissipation. The system consists of a single rotating screw enclosed within a stationary barrel. The process progresses through three distinct functional zones that correspond to the physical state transformation of the processed material:

- Feed Zone: Solid polymer pellets or powders are introduced via a hopper and conveyed forward through the rotating motion of deep-flight screw channels. The primary function is steady solids transport through friction between the material and barrel wall [1].

- Compression (Transition) Zone: The screw channel depth progressively decreases, compacting the solid polymer bed and increasing internal pressure. This generates intense shear heat through viscous dissipation while barrel heaters initiate melting, transforming solids into a continuous melt phase [2] [3].

- Metering Zone: With uniform shallow flights, this section generates maximum pressure to pump the homogenized melt through downstream dies. It ensures stable flow output and final temperature regulation before material exit [1].

The dominant conveying mechanism relies on drag flow, where friction at the rotating barrel wall pushes material forward. This is counteracted by pressure flow backflow caused by die resistance, with the net flow determining output rate [4]. The process is primarily governed by screw geometry, barrel temperature profiles, and screw rotational speed.

Twin-Screw Extruder Mechanism

Twin-screw extruders employ two parallel screws that rotate within a barrel, creating significantly more complex processing dynamics. The specific mechanism varies considerably based on screw configuration:

- Co-rotating Intermeshing: Most common in research applications, where screws rotate similarly and fully intermesh. This creates a self-wiping action that prevents material buildup and enables intensive distributive mixing. Material follows a figure-eight path around both screws, ensuring regular reorientation and homogeneous treatment [4] [5].

- Counter-rotating Intermeshing: Screws rotate toward each other, creating intense compression at the screw intermesh similar to a gear pump. This configuration provides positive conveying and is preferred for heat-sensitive materials requiring controlled shear [2].

Unlike single-screw systems, twin-screw extruders feature modular construction with specialized screw elements that can be arranged on shafts to customize processing functions:

- Conveying Elements: Transport material forward with minimal mixing.

- Kneading Blocks: Offset discs that generate high shear for dispersive mixing and intensive melting.

- Specialty Elements: Reverse pitch, mixing gears, and other configurations that enhance distributive mixing or create processing restrictions [4] [5].

This modularity enables researchers to create specific thermal and shear histories tailored to material requirements, making twin-screw extruders ideal for complex compounding, reactive extrusion, and pharmaceutical formulation.

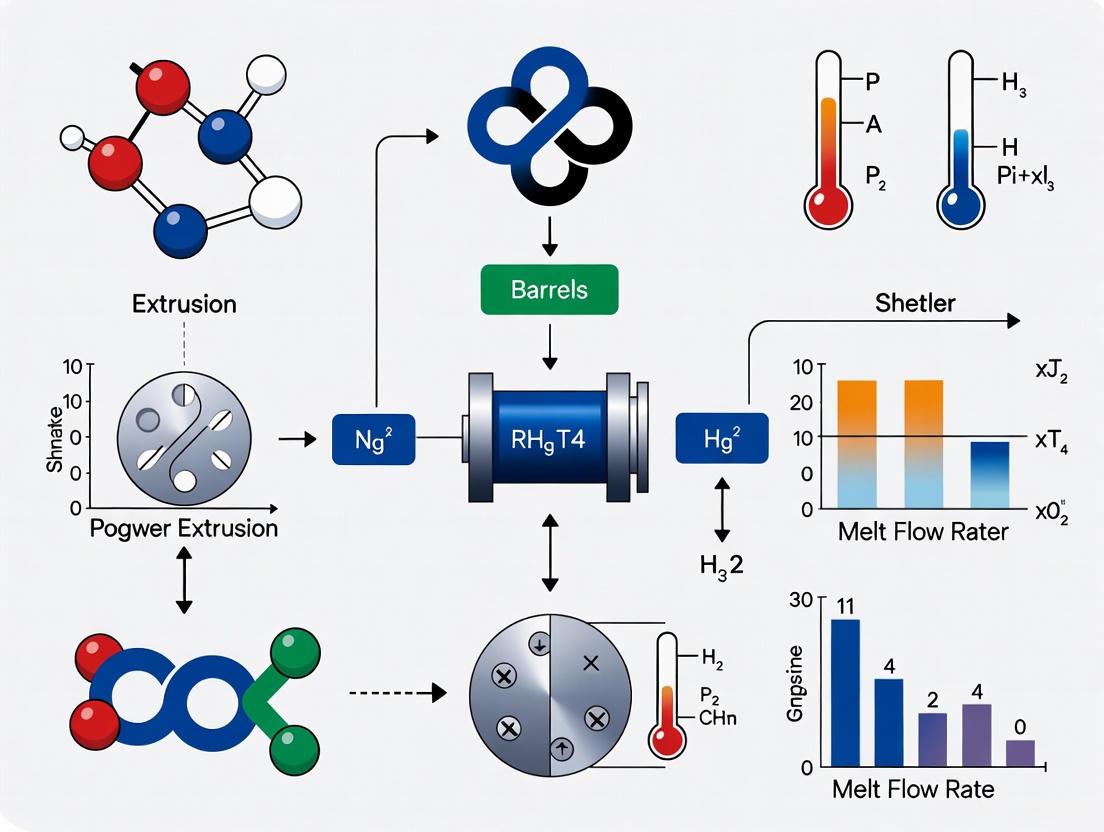

Comparative Visualization of Operating Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental differences in material flow patterns between single-screw and twin-screw extruder configurations.

Diagram 1: Comparative material flow paths in single-screw versus twin-screw extruders. Note the additional processing zones available in modular twin-screw systems.

Performance Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The selection between single-screw and twin-screw extruders requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters. The following table summarizes key quantitative and qualitative differences based on established extrusion principles and research applications.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of single-screw and twin-screw extruder characteristics

| Performance Parameter | Single-Screw Extruder | Twin-Screw Extruder |

|---|---|---|

| Mixing Efficiency | Limited, primarily distributive mixing | Excellent, both distributive & dispersive mixing [4] |

| Typical Shear Rate | Moderate to high | Precisely controllable (low to high) [2] |

| Residence Time Distribution | Relatively narrow | Broader, tunable via screw configuration [5] |

| Energy Consumption (per kg output) | Lower | Higher [6] |

| Feed Capability | Limited to pellets and uniform powders | Excellent for powders, pellets, liquids, and additives [2] |

| Pressure Generation | High, up to 400-450 bar [1] | Moderate, typically <200 bar |

| Self-Cleaning Capability | Poor | Excellent (co-rotating designs) [4] |

| Devolatilization Capability | Limited | Excellent, multiple venting ports possible [2] |

| Capital Cost | Lower | Significantly higher [6] [7] |

| Operational Flexibility | Low | High (modular screw/barrel design) [2] |

| Typical Applications | Simple melting, shaping, pipes, sheets [2] [3] | Compounding, reactive extrusion, pharmaceuticals, food [2] [5] |

Selection Guidelines for Research Applications

The choice between extruder types should be driven by material properties, process requirements, and research objectives. The following decision workflow provides a systematic approach for researchers:

Diagram 2: Decision workflow for extruder selection based on research requirements and material characteristics.

Additional selection considerations for specialized research scenarios:

- Pharmaceutical Hot Melt Extrusion: Twin-screw extruders are overwhelmingly preferred due to their superior mixing for API-polymer dispersion, precise temperature control, and ability to handle varied feedstocks [4] [5].

- Polymer Nanocomposites: Twin-screw configurations provide the intensive dispersive mixing needed to exfoliate nanofillers within polymer matrices.

- Reactive Extrusion: Twin-screw extruders enable controlled reaction environments through specialized sequencing of mixing, reaction, and devolatilization zones [2].

- Biopolymer Processing: Counter-rotating twin-screw designs offer the gentle yet consistent shear needed for temperature-sensitive biopolymers.

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Material Feeding and Handling Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting guide for common extrusion feeding problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent feed rate | Irregular particle size, bridging, poor flow | Install bridge breakers, optimize particle size distribution [8] | Use pre-blended materials, maintain consistent feedstock |

| Powder feed instability | Low bulk density, air entrapment | Use side-stuffer feeders, implement deaeration techniques | Optimize screw design for powder handling |

| Liquid additive dispersion | Poor distributive mixing, incorrect injection | Optimize injection port location, use liquid feeder calibration | Employ distributive mixing elements post-injection |

| API/polymer segregation | Density/size differences, electrostatic effects | Optimize pre-mixing, consider masterbatch approach | Use compatibilizers, control laboratory humidity |

Product Quality and Process Stability Challenges

Problem: Gel Formation in Final Product

- Symptoms: Small, crosslinked polymer particles causing visual defects and potential weak points [8].

- Mechanism: Polymer degradation due to localized overheating, oxidative crosslinking, or contaminated regrind.

- Solutions:

- Review thermal stability of formulation components

- Implement optimized screw design to minimize high-shear regions

- Incorporate stabilizers or antioxidants for vulnerable polymers

- Regular purging with high-quality purging compounds [8]

Problem: Inconsistent API Dispersion in Pharmaceutical Formulations

- Symptoms: Variable drug content, unpredictable release profiles, poor batch reproducibility.

- Mechanism: Inadequate distributive mixing for low-dose formulations or insufficient dispersive mixing for cohesive APIs.

- Solutions:

- Optimize screw configuration with appropriate distributive (kneading blocks) and dispersive (mixing gears) elements [4]

- Consider multi-stage feeding for sensitive components

- Validate mixing efficiency with tracer studies

Problem: Material Degradation

- Symptoms: Discoloration, gas formation, odor, reduced molecular weight.

- Mechanism: Excessive residence time, inappropriate temperature settings, or excessive shear.

- Solutions:

- Optimize temperature profile to minimize peak temperatures

- Modify screw design to reduce high-shear regions

- Implement inert gas purging for oxygen-sensitive materials

Problem: Unstable Melt Pressure and Output

- Symptoms: Fluctuating motor load, variable product dimensions, surging.

- Mechanism: Inconsistent feeding, irregular melting, or poor screw design.

- Solutions:

- Ensure consistent feedstock temperature and composition

- Verify screw design appropriateness for material

- Implement closed-loop control systems for critical parameters

Experimental Protocols for Research Extrusion

Protocol for Systematic Screw Configuration Optimization

Objective: Methodically determine optimal screw configuration for new polymer-compound or pharmaceutical formulation.

Materials:

- Twin-screw extruder with modular barrel and screw elements

- Baseline screw configuration (typically 40-60% conveying, 20-30% kneading, 10-20% mixing)

- Material formulation components

Methodology:

- Establish baseline performance with standard screw configuration at mid-range temperature profile

- Vary distributive mixing intensity by adjusting number and stagger angle of kneading blocks

- Modify dispersive mixing elements by implementing blister rings or tight-clearance mixing sections

- Optimize residence time distribution through reverse-conveying elements and filled-section length

- Validate configuration through replicate runs and comprehensive product characterization

Evaluation Metrics:

- Mixing efficiency (coefficient of variation in component distribution)

- Specific mechanical energy input

- Melt temperature uniformity

- Process stability (pressure and torque fluctuations)

Protocol for Scale-up from Research to Pilot Scale

Objective: Establish predictive methodology for transferring extrusion processes from laboratory to production scale.

Materials:

- Laboratory-scale twin-screw extruder (typically 16-27mm diameter)

- Pilot/production-scale extruder (typically 40-70mm diameter)

- Representative material batch

Methodology:

- Characterize key dimensionless numbers at both scales:

- Specific mechanical energy (SME)

- Fill factor along extruder length

- Shear rate distribution in key sections

- Maintain constant thermal history by matching:

- Maximum shear stress experienced by material

- Residence time above critical temperatures

- Validate scale-up criteria through:

- Equivalent product morphology and properties

- Consistent chemical conversion (for reactive extrusion)

- Comparable mixing efficiency

Troubleshooting Scale-up Issues:

- Incomplete melting at larger scale: Increase compression zone intensity

- Excessive temperature rise: Modify screw design to reduce specific energy input

- Altered reaction kinetics: Adjust temperature profile and residence time

Critical Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for polymer extrusion research

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Carriers | EVA, PLA, PCL, HPMC, Soluplus [4] | Matrix former for solid dispersions | Pre-dry hygroscopic polymers, monitor MW distribution |

| Plasticizers | Triethyl citrate, PEG, Dibutyl sebacate | Process aid, modifier for drug release | Verify compatibility, assess migration potential |

| Stabilizers | BHT, Vitamin E, Irgafos 168 | Prevent oxidative degradation during processing | Optimize concentration to avoid interactions |

| Processing Aids | Tale, silica, metal stearates | Enhance feed flow, reduce adhesion | Monitor potential impact on dissolution |

| Purging Compounds | Specialty polyolefin blends [8] | Equipment cleaning between formulations | Select appropriate cleaning temperature |

Analytical Techniques for Extrudate Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of extruded materials is essential for research validation:

- Thermal Analysis: DSC for melting behavior, glass transition, and compatibility assessment

- Rheological Characterization: Melt flow index, capillary, and oscillatory rheometry for processability prediction

- Morphological Analysis: SEM, TEM, and XRD for phase distribution, crystal structure, and filler dispersion

- Spectroscopic Analysis: FTIR and NIR for chemical structure, degradation monitoring, and composition verification

- Dissolution Testing: USP apparatus for drug release profiling from pharmaceutical formulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanical difference between single-screw and twin-screw extruders? A: Single-screw extruders rely primarily on friction between the material and barrel wall for forward transport, creating drag-induced flow. Twin-screw extruders utilize positive displacement with the two intermeshing screws mechanically conveying material forward, enabling more precise control and superior mixing capabilities [2] [1].

Q2: When is a twin-screw extruder absolutely necessary for pharmaceutical research? A: Twin-screw extruders are essential when processing heat-sensitive APIs, formulating solid dispersions requiring homogeneous API distribution, handling multiple components with significantly different physical properties, conducting reactive extrusion, or when precise control over shear and thermal history is critical for product performance [4] [5].

Q3: Can single-screw extruders provide adequate mixing for polymer nanocomposites? A: Generally no. The limited mixing capability of single-screw extruders is insufficient for exfoliating and dispersing nanoscale fillers (clay, graphene, etc.) within polymer matrices. Twin-screw extruders with appropriately configured high-shear zones are necessary to achieve the required nanoscale dispersion and corresponding property enhancements [2].

Q4: How do I determine the appropriate screw configuration for a new formulation? A: Begin with a baseline configuration (approximately 40% conveying, 30% kneading, 20% mixing, 10% special elements). Conduct trials while monitoring process parameters (torque, pressure, temperature) and product characteristics. Systematically adjust kneading block sequences for distributive mixing and incorporate high-shear elements for dispersive mixing requirements while monitoring specific mechanical energy input [4].

Q5: What are the key scale-up considerations when moving from research to production extruders? A: Critical scale-up factors include maintaining constant specific mechanical energy (SME), matching shear rate profiles in key sections, preserving equivalent residence time distribution, and ensuring thermal history similarity. Geometrical similarity alone is insufficient; focus on maintaining consistent thermo-mechanical environment rather than identical screw geometry [5].

Q6: How can I prevent API degradation during hot melt extrusion? A: Implement multiple strategies: (1) optimize processing temperature to minimum effective level, (2) use plasticizers to reduce viscosity and processing temperature, (3) configure screws to minimize high-shear regions, (4) employ inert gas purging to eliminate oxidative degradation, and (5) incorporate appropriate stabilizers compatible with your formulation [4] [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Extrusion Defects and Solutions

This guide addresses common challenges in polymer extrusion, providing researchers with targeted solutions to maintain process integrity and data quality.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Extrusion Defects

| Defect Phenomenon | Root Cause | Impact on Research & Product Quality | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melt Fracture [9] [10] | Turbulent flow in die; Low melt temperature; High molecular weight polymer [10]. | Random fractures/roughness on extrudate; Inconsistent product dimensions and mechanical properties [9]. | Streamline die geometry; Increase melt temperature; Use lower MW polymer; Increase die land length [9] [10]. |

| Sharkskin/Alligator Hide [9] [10] | Tensile stress at die exit causing surface rupture; High extrusion speed; Low die temperature; High modulus resin [10]. | Rough surface with lines perpendicular to flow; Compromised surface aesthetics and potential failure initiation sites [9]. | Increase die temperature; Reduce extrusion speed; Use polymer with broader molecular weight distribution; Employ processing aids [9] [10]. |

| Surging (Unstable Output) [9] [10] | Irregular solids conveying; Feed bridging; Mismatch between screw design and material bulk density; Contamination [10]. | Cyclical variation in extrudate thickness; Inconsistent data from experiments; Poor product uniformity [9]. | Ensure free filament flow; Check for hopper bridging; Use cram feeder for fluffy materials; Optimize screw design for material [11] [10]. |

| Under-Extrusion [11] | Nozzle clog; Filament feed issues; Incorrect temperature; Excessive retraction settings [11]. | Gaps in extrudate; Weak, crumbly prints; Poor layer adhesion [11]. | Clear nozzle clog; Ensure filament spool rotates freely; Increase print temperature; Reduce retraction distance [11]. |

| Polymer Degradation [10] | Excessive heat for extrusion speed; Material trapped in extruder (long residence time) [10]. | Discoloration; Odor; Reduced mechanical properties; Carbonized specks in extrudate [10]. | Reduce heat profile or increase screw speed; Improve flow path in die/barrel; Implement thorough purging procedures [10]. |

| Poor Mixing [10] | Extruder speed too high; Insufficient back pressure; Inadequate screw design [10]. | Streaks or unmixed particles in extrudate; Inhomogeneous material properties [10]. | Reduce screw speed; Increase back pressure (finer screens); Use mixing screws or static mixers; Pre-mix materials [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: What is the functional purpose of the different zones in a single-screw extruder? [9] [12] The screw is strategically designed in zones to progressively transition the polymer from solid to a homogeneous melt:

- Feed Zone (Solids Conveying): This first zone preheats the polymer pellets (via conduction from the barrel) and conveys them forward. The screw channel depth is constant here [9] [12].

- Compression Zone (Melting/Transition): The screw channel depth progressively decreases, compressing the polymer. This action dissipates air gaps between granules, improves heat transfer, and accommodates density change as the polymer melts. Most melting occurs here due to a combination of conductive heating from the barrel and intense shear heating [9] [12].

- Metering Zone (Melt Conveying): The channel depth is constant again. Its primary function is to homogenize the melt to a uniform temperature and composition and to pump it at a constant rate against the resistance of the screen pack and die [9] [12].

- Die Zone: While not part of the screw, this final zone houses the breaker plate and screen pack, which filter contaminants and create essential back pressure for uniform melting. The die itself shapes the polymer melt [9].

Q2: Why is melt temperature management critical, and how can low temperatures impact my results? [13] Managing melt temperature is fundamental to process stability and material integrity. A low melt temperature can lead to:

- Incomplete Melting: Polymers may not fully melt, leading to poor mixing and potential degradation of unmaterial [13].

- Reduced Extrusion Rate: Lower temperatures decrease production efficiency and throughput [13].

- Poor Product Quality: Inadequate plasticization results in poor product gloss, inferior mechanical properties, and surface defects [13]. Causes include improper barrel temperature settings, low screw speed (reducing shear heating), and inadequate screw design for the polymer [13].

Q3: What advanced computational methods are emerging for extrusion die optimization? Recent research focuses on automating die design using High-Performance Computing (HPC). These frameworks couple simulation codes (e.g., OpenFOAM for non-isothermal, non-Newtonian flow) with optimization libraries (e.g., Dakota) [14]. They automatically test hundreds of parameterized die geometries to find an optimal solution that ensures balanced flow distribution at the die outlet, significantly reducing traditional design time and material waste from trial-and-error [14].

Experimental Protocols for Process Optimization

Protocol 1: Establishing an Optimal Barrel Temperature Profile

Objective: To determine a barrel temperature profile that ensures a homogeneous melt while minimizing polymer degradation and energy consumption.

Methodology: [15]

- Start with the Die: Set the die and adapter temperature to the resin manufacturer's recommended melt temperature.

- Set the Feed Throat: Cool the feed throat to between 110°F and 120°F (43-49°C) to prevent bridging while slightly preheating the material.

- Configure Zone 1 (Feed Section): Set this zone to a high temperature (e.g., 300-400°F / 149-204°C for polyolefins) to maximize the barrel-pellet friction and solids conveying.

- Configure Zone 2 (First Intermediate): Set this zone 125-175°F (52-79°C) higher than Zone 1 to input significant energy to the polymer, aiding melting without over-relying on mechanical shear.

- Configure Final Zones (Metering Section): Set the barrel zone(s) immediately before the die 10-25°F (5-14°C) below the target melt temperature. This allows for final viscous shear heating to bring the polymer to the exact desired temperature and prevents overheating.

Table 2: Example Temperature Profile for a Barrier Screw (Guideline)

| Extruder Section | Set Temperature Relative to Target Melt Temp (Tm) | Functional Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Feed Throat | Cooled to ~110-120°F (43-49°C) | Prevents bridging; initiates pre-heating. |

| Zone 1 (Feed) | Significantly below Tm (e.g., 300-400°F) | Maximizes friction for efficient solids conveying. |

| Zone 2 (Transition) | Intermediate value between Zone 1 and Tm | Adds thermal energy to assist melting. |

| Final Barrel Zones | 10-25°F (5-14°C) below Tm | Relies on viscous shear for final heating; prevents degradation. |

| Die & Adapter | At Target Melt Temp (Tm) | Maintains homogeneous melt for consistent flow and shaping. |

Protocol 2: Computational Flow Balancing for Die Design

Objective: To utilize an HPC-driven optimization framework to automatically design a profile extrusion die with a perfectly balanced flow distribution at the outlet.

Methodology: [14]

- CAD Parameterization: Create a parameterized 3D model of the die flow channel in CAD software (e.g., Onshape, Fusion 360), defining key geometrical features as variables.

- Define Objective Function: The core of the optimization is an objective function that quantifies flow imbalance. The outlet cross-section is subdivided into Elemental Sections (ES) and Intersection Sections (IS). The function is calculated as:

- ( F{\text{obj}} = \frac{\sum{(F{\text{obj},i} \times A{\text{trg},i})}}{\sum{A{\text{trg},i}}} )

- Where the individual section objective ( F{\text{obj},i} = \frac{(Qi / Q{\text{trg},i}) - 1}{\max(Qi / Q_{\text{trg},i}, 1)} )

- Here, ( Qi ) is the actual flow rate in section

i, and ( Q{\text{trg},i} ) is the target flow rate for that section [14].

- HPC-Driven Optimization: A software framework (e.g., coupling Dakota and OpenFOAM) automatically launches hundreds of simulations on an HPC cluster, each with a different geometrical variant. It iteratively adjusts the parameters to minimize the global objective function (( F_{\text{obj}} )).

- Convergence Criterion: The simulation uses an objective function-controlled convergence, stopping calculations once the function value stabilizes, which can reduce calculation time by up to 50% compared to traditional residual-based convergence [14].

Process Visualization and Workflows

HPC-Based Die Optimization Logic

Extruder Functional Zones and Material Transition

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Extrusion Research

| Item Name | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Resins & Additives | Base material for extrusion; modifiers for rheology, stability, and properties. | Studying process-property relationships; developing new polymer blends and composites [13]. |

| Screen Pack / Breaker Plate | Filters contaminants; creates back pressure crucial for melt homogenization. | Essential for maintaining process consistency and ensuring the purity of the extrudate in experimental runs [9] [12]. |

| Specialized Extrusion Screws | Engineered screws (e.g., barrier, mixing) for specific melting and mixing actions. | Investigating melting efficiency; optimizing mixing for nanocomposites or immiscible blends [13] [15]. |

| OpenFOAM & Dakota | Open-source computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and optimization software. | Implementing HPC-based die design frameworks; simulating non-Newtonian melt flow; automating geometry optimization [14]. |

| Parameterized CAD Models | Digital models of dies and flow channels with variable geometric parameters. | Serving as the digital twin for simulation-driven design and optimization studies [14]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the massive computational power required for iterative simulation-optimization loops. | Enabling the automatic testing of hundreds of die geometries within a feasible timeframe (e.g., one day) [14]. |

Within the broader research on optimizing polymer extrusion processes, understanding the intrinsic relationship between material rheology and behavior is paramount for defining operational windows. This technical support center addresses the specific, practical challenges researchers and scientists face during experiments, particularly when working with advanced materials like highly filled polymers. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides are designed to diagnose common issues rooted in rheological properties, offering data-driven methodologies and protocols to refine process parameters and ensure experimental reproducibility.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my highly filled polymer composite (>50% vol. filler) exhibit excessive surface tearing or shark-skin upon exiting the die?

This is a common defect in highly filled systems, often attributed to wall slip and plug flow behavior. At high filler loadings, the material's viscosity increases significantly, and the melt may begin to slip at the die wall rather than maintaining a steady, adherent flow. This slip-stick phenomenon can cause surface tearing [16]. To mitigate this:

- Investigate Slip Characteristics: Perform a thorough rheological analysis using a capillary rheometer with the Mooney correction to quantify the slip velocity as a function of shear stress [16].

- Adjust Process Conditions: Increasing the shear rate or implementing die cooling has been shown to produce smoother profiles in some wood polymer composites [16].

- Review Material Composition: Ensure chemical compatibility between the filler and polymer binder. Poor compatibility can lead to dewetting at the interface, exacerbating void formation and surface defects [17].

FAQ 2: My composite feedstock has unpredictable porosity after extrusion or additive manufacturing. What are the potential causes?

Process-induced porosity is a significant challenge that degrades mechanical properties and can lead to part failure [17]. The causes are often multifactorial:

- Particle-Binder Interface: Poor chemical compatibility between the filler particles and the polymer matrix can lead to dewetting and interfacial void formation. Surface functionalization of the particles can improve dispersion and compatibility [17].

- Trapped Air: High-viscosity feeds can trap air during mixing or the feeding process. Degassing or using ram-fed extruders can help minimize this [17].

- Transport Phenomena: In additive manufacturing, improper nozzle geometry or tool path can create voids between deposited layers. Inadequate bonding between layers is also a concern [17].

- Gaseous Byproducts: If your polymer binder involves a curing reaction, gaseous byproducts may be formed, creating voids within the structure [17].

FAQ 3: How can I accurately determine the molar mass of a polymer melt using rheology?

The zero-shear viscosity of a polymer melt is directly proportional to its average molar mass [18]. This can be determined through oscillatory rheometry.

- Experimental Protocol: Perform a frequency sweep test at a constant temperature and strain within the linear viscoelastic region.

- Data Analysis: The zero-shear viscosity (η₀) is identified as the plateau in complex viscosity (|η*|) at low angular frequencies. For a qualitative picture of average molar mass, the crossover point of the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G") curves can also be analyzed [18]. This method does not require solvents and has no limits on molar mass distribution determination [18].

FAQ 4: What is the "pot life" of a reactive polymer system like polyurethane, and how can I measure it rheologically?

For two-component reactive systems like polyurethane, the pot life is the period during which the mixed resin remains processable (e.g., can be injected into a mold) [18].

- Measurement Protocol: Use an oscillatory rheometer with a parallel-plate measuring system to monitor the curing process.

- Procedure: Mix the isocyanate and polyol components, load the sample, and run an oscillation test with a constant low strain (e.g., 0.05%). The point at which the complex viscosity increases dramatically, indicating the sol-gel transition, defines the end of the pot life and the beginning of the curing process [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Correcting Flow Instabilities in Extrusion

This guide addresses common extrusion defects linked to material rheology.

Problem: Melt Fracture (Unstable, wavy extrudate).

- Root Cause: Excessive shear stress at the die wall.

- Solutions:

- Increase Die Temperature: This lowers the melt viscosity, thereby reducing shear stress.

- Reduce Extrusion Speed: Lowering the screw speed decreases the shear rate.

- Modify Die Geometry: Use a die with a longer land length or a larger diameter to reduce the shear rate.

- Use a Processing Aid: Incorporate additives like fluoropolymers to promote wall slip.

Problem: Surging (Unstable, cyclical output pressure and throughput).

- Root Cause: Unstable solids conveying or melting in the extruder, often severe with highly filled polymers that have high bulk density and different melting mechanisms [16].

- Solutions:

- Check Feed Stock: Ensure consistent feedstock form (pellet size, powder density).

- Adjust Barrel Temperature Profile: A poorly set profile can cause unstable melting.

- Review Screw Design: Standard screws may be inadequate. A screw designed specifically for composites may be necessary.

Guide: Optimizing Additive Manufacturing of Highly Filled Polymers

This guide focuses on challenges specific to material extrusion (e.g., Fused Filament Fabrication, Direct Ink Writing) of composites.

Problem: Poor Interlayer Adhesion.

- Root Cause: Inadequate bonding and sintering between layers, potentially due to reduced molecular mobility near interfaces and high viscosity from fillers [17].

- Solutions:

- Increase Nozzle Temperature: Enhances polymer chain diffusion between layers.

- Optimize Print Speed: A slower speed allows more time for heat transfer and polymer interdiffusion.

- Reduce Layer Height: Increases contact pressure between layers.

Problem: Nozzle Clogging.

- Root Cause: Particle agglomeration or the filler content exceeding the maximum packing fraction for the given nozzle diameter.

- Solutions:

- Improve Particle Dispersion: Use surface modifiers or compatibilizers to break up agglomerates [17].

- Use a Larger Nozzle Diameter: Reduces the probability of a particle jamming the orifice.

- Filter the Feedstock: Remove large agglomerates before processing.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Rheological Properties of a Wood-Polymer Composite (50% Wood Filler in PP)

The following table summarizes the viscous and slip flow properties determined for a specific composite, illustrating key rheological behaviors [16].

Table 1: Rheological and Slip Properties of a PP/Wood Composite

| Property | Value / Description | Measurement Conditions & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Behavior | Pseudoplastic (Shear-thinning) | Viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate [16]. |

| Viscosity Range | ~1000 to ~10000 Pa·s | Shear rate range of 1 to 1000 s⁻¹ at 180-200°C [16]. |

| Temperature Effect | Moderate decrease with temperature | Not as significant as the effect of shear rate [16]. |

| Yield Stress | Present | Material does not flow until a critical stress is applied [16]. |

| Wall Slip | Present, two-regime behavior | Weak slip at low shear stress, followed by a sharp increase in slip velocity at high shear stress [16]. |

| Mooney Analysis | Used to quantify slip velocity | Slip velocity is plotted versus shear stress [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining True Viscosity and Slip Effects with a Capillary Rheometer

This protocol is essential for accurately characterizing highly filled polymers, which often exhibit wall slip.

Objective: To determine the true shear viscosity of a polymer composite while accounting for non-Newtonian flow and wall slip effects. Materials: Capillary rheometer, multiple capillaries with the same diameter but different L/D ratios (e.g., 0/1, 10/1, 20/1, 40/1) [16]. Procedure:

- Conditioning: Dry the material according to manufacturer specifications to prevent hydrolysis.

- Loading: Fill the rheometer barrel with material and allow it to thermally equilibrate.

- Testing: Force the material through each capillary at a set of constant piston speeds (which correspond to apparent shear rates). Record the pressure drop for each capillary.

- Data Analysis:

- Apply Bagley Correction: Use data from capillaries with different L/D ratios to correct for entrance pressure losses and calculate the true wall shear stress [16].

- Apply Rabinowitsch Correction: Correct the apparent shear rate to account for the non-parabolic velocity profile in non-Newtonian fluids, yielding the true shear rate [16].

- Apply Mooney Correction: Using data from capillaries of the same L/D but different diameters, analyze the flow rate as a function of diameter to calculate the slip velocity at the wall [16].

The final true viscosity is calculated as (Bagley-corrected shear stress) / (Rabinowitsch- and Mooney-corrected shear rate).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for troubleshooting a polymer process problem, starting from the observed defect and moving through systematic rheological investigation to a solution.

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting workflow for polymer processing defects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for Polymer Process Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Capillary Rheometer | Measures viscosity at high shear rates and identifies wall slip effects. | Essential for simulating extrusion conditions and applying Bagley, Rabinowitsch, and Mooney corrections [16]. |

| Oscillatory Rheometer | Characterizes viscoelastic properties (G', G"), zero-shear viscosity, and curing kinetics. | Determines molar mass, glass transition temperature (Tg), and pot life of reactive systems [18]. |

| Polymer Binders (PP, HDPE, PU) | Act as the continuous matrix that binds functional fillers. | Selection depends on application (e.g., PP for automotive, HDPE for building profiles) [18] [16]. |

| Surface Modifiers / Coupling Agents | Improve compatibility between hydrophobic polymers and hydrophilic fillers. | Reduces interfacial voids and improves dispersion, mitigating process-induced porosity [17]. |

| Highly Filled Feedstock | Model material for studying process challenges like high viscosity and slip. | Wood polymer composites (50% filler) or ceramic feeds (>50% vol. particles) are common model systems [17] [16]. |

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the fundamental rheological characterization of a new polymer composite material.

Diagram 2: Rheological characterization workflow for polymer composites.

Energy Dynamics and Key Performance Indicators in Extrusion Systems

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Extrusion Issues

Uneven Mixing and Poor Dispersion

- Problem: Inconsistent mixing and poor dispersion of fillers or additives lead to variations in final product quality and compromised performance.

- Causes: Improper screw configuration, insufficient barrel temperature, or incorrect feeding rates. [19]

- Solutions:

- Re-evaluate and optimize the screw configuration, particularly the kneading block arrangement. [19]

- Increase the intensity of mixing sections and adjust barrel temperature zones to improve homogenization. [19]

- Modify feed rates to ensure a consistent and optimal material flow. [19]

- Utilize Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to simulate and fine-tune screw designs before physical production runs. [19]

Overheating and Material Degradation

- Problem: Excessive heat causes degradation of sensitive polymers, leading to discoloration, loss of mechanical properties, or foul odors. [19]

- Causes: High barrel temperatures, excessive shear from the screw, or insufficient cooling. [19]

- Solutions:

Melt Fracture

- Problem: The polymer melt exits the die with a rough, irregular surface, compromising product appearance and potentially its mechanical properties. [19]

- Causes: Excessive extrusion speeds or high melt viscosity. [19]

- Solutions:

Surging

- Problem: Fluctuations in melt pressure cause inconsistency in product dimensions and properties. [19]

- Causes: Irregular feed rates, improper screw design, or unstable material flow in the barrel. [19]

- Solutions:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the importance of temperature control in extrusion? A: Temperature control is crucial for maintaining material properties. Fluctuations can lead to products that do not meet quality standards, causing issues like degradation or poor dimensional stability. Precise temperature regulation is necessary throughout the extrusion process to ensure optimal melting, mixing, and flow of the polymer. [20]

Q2: How does pressure management affect the extrusion process? A: Pressure management involves continuous monitoring and adjustments to prevent defects and ensure smooth material flow. Effective pressure control significantly reduces issues like material deterioration and inconsistent output, which are critical for maintaining product quality and operational efficiency. [20]

Q3: Why is speed regulation important in extrusion? A: Speed regulation affects how the material cools and solidifies during shaping, which directly impacts the quality of the final product. Adjusting the speed can lead to improved results in the shaping process by influencing crystallization, orientation, and surface finish. [20]

Q4: What role does die geometry play in energy efficiency? A: Die geometry has a significant impact on energy consumption. Research shows that conical and arc-shaped dies can conserve up to 15% of energy compared to flat dies by improving material flow and reducing deformation forces. Optimizing die design is therefore a key strategy for enhancing sustainability. [21]

Experimental Protocols for Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Protocol for Assessing Energy Efficiency

- Objective: To quantify energy consumption and identify savings through die geometry optimization. [21]

- Methodology:

- Simulation: Use Finite Element Method (FEM) software (e.g., QFORM) to simulate the forward extrusion process. Model different die geometries (flat, conical, arc-shaped) and analyze deformation forces, stress distribution, and energy losses. [21]

- Experimental Validation: Conduct physical extrusion experiments using lead or a model material. Utilize dies of varying geometries and measure the peak extrusion force and total energy consumption. [21]

- Data Modeling: Employ Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to predict process energy based on experimental data. Develop and validate a regression model to forecast peak extrusion force in relation to elongation parameters. [21]

- Key Metrics: Peak extrusion force (kN), total energy consumption per unit (kJ/kg).

Protocol for Monitoring Operational KPIs

- Objective: To track and improve the operational efficiency of an extrusion plant. [22]

- Methodology:

- Data Collection: Gather historical data on production rates, defect rates, material usage, and energy consumption. [20] [22]

- Procedure Audit: Systematically review each stage of the extrusion process, from material preparation to final product inspection, checking for inconsistencies in temperature, pressure, and speed. [20]

- KPI Calculation: Consistently measure and record the following core KPIs: [22]

- Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE)

- Material Yield Rate

- Energy Consumption per Unit of Production

- Customer Rejection Rate

Data Presentation

Energy Consumption by Die Geometry

This table summarizes findings from research on the impact of die geometry on energy dynamics during extrusion. [21]

| Die Geometry | Relative Energy Consumption | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Flat Die | Baseline | Higher deformation forces, less efficient material flow. |

| Conical Die | Up to 15% lower | Improved material flow, reduced forces. |

| Arc-Shaped Die | Up to 15% lower | Smooth material transition, minimal energy loss. |

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Extrusion Plants

This table outlines vital KPIs for monitoring and optimizing extrusion process performance. [22]

| KPI | Target Benchmark | Description & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) | 85% | Composite metric measuring availability, performance, and quality. Critical for productivity. [22] |

| Material Yield Rate | > 98% | Ratio of sellable product to raw material used. Directly impacts material costs and waste. [22] |

| Energy Consumption per Unit | 0.3-0.5 kWh/kg | Energy required to produce a unit mass. Key for cost control and sustainability. [22] |

| Customer Rejection Rate | < 0.5% | Percentage of products rejected due to quality defects. Reflects process stability and quality. [22] |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Extrusion Troubleshooting Logic

KPI Monitoring Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Extrusion Experiments

| Material/Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Lead (High Purity) | A model material for physical simulation of extrusion processes due to its softness and low recrystallization temperature, allowing for the study of plastic flow and deformation mechanics at room temperature. [21] |

| Polymer Composites (PAHT-CF, PPA-CF) | High-performance carbon fiber-reinforced polymers used to study the extrusion of materials with enhanced strength, stiffness, and thermal resistance, particularly for high-value applications like aerospace. [23] |

| ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) | A widely used, cost-effective thermoplastic for benchmarking extrusion parameters and studying the behavior of amorphous polymers under various processing conditions. [23] [24] |

| Fluoropolymer Processing Aids | Additives used to reduce melt fracture and die build-up by forming a low-friction layer, enabling the study of melt flow stabilization and surface finish improvement. [19] |

Advanced Methodologies for Process Optimization: From DoE to AI-Driven Modeling

Leveraging Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Parameter Optimization

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize polymer extrusion processes and other complex systems. RSM is a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques used to model and optimize processes where multiple input variables (factors) influence one or more output responses [25]. Originally introduced by Box and Wilson in 1951, it has become indispensable in engineering, manufacturing, and pharmaceutical development for efficiently determining optimal operational conditions [25] [26].

The following guides address common experimental challenges, provide step-by-step protocols, and detail essential research tools to ensure robust and reliable optimization in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core objective of using RSM in process optimization like polymer extrusion?

The primary objective is to find the optimal factor settings that maximize or minimize a response variable through systematic experimentation and modeling [25] [27]. For polymer extrusion, this could mean optimizing the wall temperature profile of a die to achieve a uniform exit velocity distribution of the polymer melt, thereby improving product quality and process efficiency [28].

Q2: When should I use a Central Composite Design (CCD) versus a Box-Behnken Design (BBD)?

Both are used for fitting second-order (quadratic) models, but they have different structures and applications. A Central Composite Design (CCD) extends a factorial design by adding center points and axial (star) points, allowing it to cover a broader experimental region and estimate curvature effectively [29] [30]. A Box-Behnken Design (BBD) is a spherical design that lacks corner points and uses fewer runs than a CCD for the same number of factors, making it efficient when experimenting at the extreme corners (factorial points) is impractical or expensive [30].

Q3: My model has a high R² value, but the Lack-of-Fit test is significant. What does this mean, and what should I do?

A high R² indicates your model explains most of the variation in the data, but a significant Lack-of-Fit test suggests the model may not adequately capture the underlying relationship between factors and the response [31]. This could be due to missing higher-order terms (e.g., cubic effects) or the need for a transformation of your response data [31]. You should:

- Investigate residuals: Plot residuals against predicted values and each factor to identify patterns [31].

- Consider model augmentation: Your model might require additional terms. Using stepwise regression to explore adding third-order terms can be beneficial [31].

- Evaluate practical significance: Sometimes, the lack-of-fit is statistically significant but small enough that the model remains useful for your practical objectives [31].

Q4: How do I handle multiple responses, like optimizing for both yield and purity?

When dealing with multiple, potentially conflicting responses, use a Desirability Function approach [30] [27]. This method transforms each response into an individual desirability value (between 0 and 1) and then combines them into a single overall desirability function, which is subsequently optimized.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate Model or Significant Lack-of-Fit

Problem: After analyzing your experimental data, the regression model shows a significant lack-of-fit, indicating the model does not properly represent the process.

Solution:

- Check for missing terms: Your model might be missing important interaction or quadratic terms. Ensure you are using a design capable of estimating a second-order model (e.g., CCD or BBD) [25] [30].

- Analyze residual plots: Save residuals from your analysis and plot them against each factor and the predicted values. Visible patterns in these plots (e.g., a funnel shape) indicate model inadequacy and may suggest the need for a response transformation [31].

- Consider higher-order terms: For complex systems, a second-order polynomial might be insufficient. Explore adding select third-order terms if your design and data allow, using techniques like forward stepwise regression [31].

Issue 2: Difficulty in Locating the Optimal Point

Problem: The optimization analysis does not converge to a clear optimum, or the suggested optimum is at the edge of your experimental region.

Solution:

- Expand the experimental region: If the optimum lies on a boundary, your current factor ranges may not include the true optimum. Consider augmenting your design with new experiments in the direction of improvement [27].

- Use the method of steepest ascent/descent: To sequentially move toward the optimum region, especially when starting from a point far from optimum [30] [27].

- Verify constraints: Ensure all practical constraints (e.g., physical, safety, or economic limits) are correctly specified in your optimization setup [27].

Issue 3: Unreliable Replication and High Pure Error

Problem: Replicated experimental runs show high variability, leading to a large "pure error" estimate in your analysis and potentially masking significant effects.

Solution:

- Standardize experimental procedures: Ensure that all process steps and measurement techniques are tightly controlled and consistent across all runs [31].

- Investigate replicates: Closely examine the replicated runs to identify any assignable causes for the high variation [31].

- Account for hard-to-change factors: If your process has factors that are difficult or expensive to change randomly (e.g., oven temperature in polymer extrusion), use a split-plot design structure to improve efficiency and reflect the true nature of the experimentation [27].

Experimental Protocol: RSM for Polymer Extrusion Die Optimization

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying RSM to optimize the wall temperature profile in a polymer extrusion die, a process critical for achieving uniform product quality [28].

Define the Problem and Responses

- Objective: Achieve a uniform average velocity across the die exit.

- Response Variable: Measure of flow uniformity (e.g., standard deviation of velocity at the die exit).

- Constraint: Limit the pressure drop within the die to a specified maximum [28].

Select Factors and Ranges

- Factors: Identify sections of the die wall where temperature can be independently controlled.

- Ranges: Define a feasible temperature range for each section based on material properties and equipment limits.

Choose an Experimental Design

- Recommended Design: Central Composite Design (CCD) is highly suitable [28] [30].

- Justification: CCD efficiently estimates the quadratic model needed to capture potential curvature in the response surface, which is common in thermal processes.

Conduct Experiments and Numerical Simulations

- Run the experiments as per the design matrix. For extrusion die design, this often involves using Finite Element Method (FEM) simulations to evaluate the objective function (flow uniformity) and constraint (pressure drop) for each experimental run [28].

Model Fitting and Analysis

- Fit a second-order polynomial model to the data using regression analysis.

- Perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to check the significance of the model and its terms.

- Validate the model using diagnostic plots (residuals vs. predicted, normal probability plot).

Optimization and Validation

- Use an optimization algorithm (e.g., Sequential Quadratic Programming - SQP) to find the temperature profile that maximizes flow uniformity while respecting the pressure drop constraint [28].

- Perform a confirmation run (via FEM or physical experiment) at the predicted optimal settings to validate the model's accuracy.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

The table below lists key computational and statistical tools essential for conducting a successful RSM study in a research context.

Table: Essential Toolkit for RSM-Based Process Optimization

| Tool/Solution | Function in RSM Research |

|---|---|

Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, R, Python with statsmodels) |

Used for designing experiments, performing regression analysis, ANOVA, model validation, and generating optimization plots [31]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Acts as a virtual experiment platform to evaluate responses (e.g., flow uniformity, temperature) for each experimental run in the design, reducing the need for costly physical prototypes [28]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | An experimental design structure that allows efficient estimation of a quadratic model, crucial for locating optima [29] [30]. |

| Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) | A robust numerical optimization algorithm used to find the best factor settings by maximizing or minimizing the fitted response model, often handling constraints effectively [28]. |

| Desirability Functions | A multi-response optimization technique that combines several responses into a single metric to find operating conditions that balance all objectives [30] [27]. |

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for Screw and Die Design

FAQs: Simulation and Analysis for Extrusion

1. How can FEA and CFD improve the design of an extrusion die? Using FEA and CFD allows for virtual testing and optimization of die designs before fabrication, significantly reducing the need for costly physical prototypes and trial-and-error approaches [32]. For instance, a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model can compute pressure, temperature, velocity, and viscosity distributions of the polymer melt (e.g., HDPE) within the die to ensure a uniform flow exit [32]. Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI) analysis, a type of Finite Element Analysis (FEA), can be used to verify that critical die components, like spider legs, can withstand the operational pressures without failure [32].

2. What are common CFD and FEA software packages used in this field? Researchers and engineers utilize a range of software. COMSOL Multiphysics is effective for solving FSI problems in spider die design [32]. The ANSYS suite, including Polyflow and Fluent, is used for simulating pressure profiles and mixing in twin-screw extruders [33] [34]. SOLIDWORKS Simulation also offers integrated CFD and FEA capabilities for design analysis [35].

3. What are the key steps in a CFD simulation workflow? The CFD process is generally structured in three main stages [36]:

- Preprocessing: This involves creating the die or screw geometry, generating a mesh (discretizing the domain into small cells), and defining fluid properties and boundary conditions (e.g., inlet flow rate, wall temperatures) [36].

- Solving: The CFD solver iteratively computes the governing equations (e.g., Navier-Stokes) for fluid flow and heat transfer within the defined domain [36].

- Postprocessing: In this stage, results such as pressure contours, temperature distributions, and velocity vectors are analyzed and visualized to interpret the simulation's outcomes [36].

4. How is meshing crucial for FEA and CFD, and what are best practices? Meshing discretizes a continuous geometry into small elements, and its quality directly impacts the simulation's accuracy, convergence, and speed [37].

- For Structural FEA (stress analysis): A finer mesh is needed, with a recommended element edge length of ≤ 1/5 of the circumference of the smallest fillet or hole to capture stress concentrations accurately [37].

- For CFD fluid analysis: To properly resolve flow dynamics, a recommended edge length of ≤ 1/7 of the relevant wall thickness is advised [37]. A growth rate between 1.2 and 1.5 for the mesh ensures smooth transitions between fine and coarse areas and is an industry standard for both FEA and CFD [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Mixing and Dispersion in Twin-Screw Extrusion

Issue: Inconsistent mixing of fillers, additives, or nanocomposites (e.g., layered silicates in polypropylene), leading to non-uniform product quality [38] [33].

| Possible Cause | Solution & Methodology |

|---|---|

| Incorrect screw configuration | Re-evaluate and optimize the screw design. Replace backward-conveying elements with mixing or kneading elements to enhance distributive mixing. Use CFD simulations (e.g., Ansys Polyflow) to analyze the mixing index and dissipative energy input along the screw length before physical trials [33]. |

| Insufficient shear energy | Adjust processing parameters to increase shear. The exfoliation of nanoparticles like layered silicates is highly dependent on shear energy from shearing and elongation flow. Optimize screw speed and mass flow rate to achieve the required dispersive mixing without causing material degradation [33]. |

Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Simulation: Model the proposed screw geometry in a CFD package to simulate pressure profiles and mixing indices [33].

- Compounding: Process the polymer nanocomposite (e.g., 90 wt% PP, 5 wt% compatibilizer, 5 wt% nanoclay) using a twin-screw extruder like a Leistritz ZSE 27 MAXX 44D [33].

- Characterization: Perform SAXS (Small-Angle X-ray Scattering) measurements on the final extrudate to quantitatively assess the degree of nanoclay exfoliation and distribution within the polymer matrix [33].

Problem 2: Die Flow Imbalance and Pressure-Related Failures

Issue: Non-uniform velocity at the die exit, leading to product dimensional instability, or structural failure of die components under high pressure [32].

Solution & Methodology:

- CFD Analysis for Flow Balancing: Develop a non-Newtonian CFD model (using software like COMSOL) to simulate the polymer flow through the die. The Carreau-Yasuda model can be used to describe the viscosity's dependence on shear rate and temperature. The goal is to achieve a balanced velocity profile at the die exit by iteratively modifying the die's internal geometry [32].

- FEA for Structural Integrity: Conduct a stress analysis on critical die parts, such as spider legs. Using FSI analysis, apply the pressure loads obtained from the CFD simulation to the solid die structure. This verifies if components machined from materials like tool steel (IMPAX) will survive the maximum expected operating pressure [32].

Die Design and Validation Workflow

Problem 3: Overheating and Material Degradation

Issue: Polymer discoloration, foul odors, or loss of mechanical properties due to excessive heat, often caused by high barrel temperatures or excessive shear in the extruder [38].

| Possible Cause | Solution & Methodology |

|---|---|

| Excessive screw speed / shear | Lower the screw speed (RPM) to reduce shear heating. For twin-screw extruders, modify the screw configuration to use less intensive mixing elements in sections where degradation is occurring [38]. |

| Insufficient cooling or high barrel temperatures | Carefully monitor and adjust the temperature setpoints across all barrel zones. Implement or enhance external cooling systems to manage the process temperature for heat-sensitive materials [38]. |

Data Tables

Table 1: Optimized Process Parameters for Polypropylene/Nanoclay Composite Extrusion

| Parameter | Standard Screw | Optimized Screw | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw Speed | Variable | Optimized for dispersion | Critical for shear energy input [33] |

| Max Pressure Peak | ~40 bar | Reduced to ~10 bar | 75% reduction, indicates smoother processing [33] |

| Dissipative Energy | Baseline | 25% reduction | Lower energy input via screw redesign [33] |

| Key Screw Element | Backward conveying | Mixing/Kneading | Improved residence time and filling [33] |

Table 2: Mesh Quality Guidelines for Simulation

| Analysis Type | Recommended Element Edge Length | Growth Rate | Key Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural FEA (Stress) | ≤ 1/5 fillet circumference [37] | 1.2 - 1.5 [37] | Capture stress concentrations |

| CFD (Fluid Flow) | ≤ 1/7 wall thickness [37] | 1.2 - 1.5 [37] | Resolve boundary layer flow |

| Thermal FEA | Equal to wall thickness [37] | 1.2 - 1.5 [37] | Model temperature gradients |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | A common polymer melt for validating die flow and pressure drop simulations [32]. | Spider die design for pipe extrusion [32]. |

| Polypropylene (PP) & Nanoclay Composite | Model material system for studying the dispersion of nanoparticles under shear. | Optimizing twin-screw extrusion for enhanced composite properties [33]. |

| Carreau-Yasuda Model | A mathematical model that describes the shear-thinning viscosity of polymer melts as a function of shear rate and temperature [32]. | Essential input parameter for accurate non-Newtonian CFD simulations [32]. |

| SAXS (Small-Angle X-ray Scattering) | An analytical technique used to characterize the nanoscale structure and degree of exfoliation of layered silicates within a polymer matrix [33]. | Quantitative validation of mixing efficiency in nanocomposite extrusion [33]. |

| Tool Steel (IMPAX) | A common material for fabricating the body of extrusion dies due to its strength and durability under high pressure and temperature [32]. | Used in the physical manufacture of the spider die after virtual validation [32]. |

Parameter-Performance Relationship in Extrusion

The Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Neural Networks in Complex System Modeling

Technical Support Center: AI for Polymer Extrusion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What type of neural network is best for modeling the nonlinear relationships in polymer extrusion? Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and their variants, such as Graph Convolutional Networks, are highly effective for modeling polymer extrusion processes. They excel at capturing the complex, interconnected relationships between process parameters (e.g., temperature, screw speed) and material properties [39] [40]. Invertible Neural Networks (INNs) are also particularly valuable for inverse problems, such as determining the optimal process parameters needed to achieve a specific material property or flow rate [41].

FAQ 2: How can we overcome the challenge of limited and high-cost experimental data in polymer research? Synthetic data generation is a powerful strategy to overcome data scarcity. For instance, creating synthetic SEM-like images with known fiber orientation tensors to train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) has been successfully demonstrated [42]. Furthermore, employing active learning or Bayesian optimization can guide experimental design, ensuring that the most informative data points are collected, thereby reducing the total number of experiments required [43] [44].

FAQ 3: Our deep learning models for extrusion prediction are "black boxes." How can we improve their interpretability? To enhance interpretability, you can apply mechanistic interpretability techniques that aim to reverse-engineer a model's computations. Training sparse models, where most network weights are zero, can force the network to learn simpler, more disentangled circuits that are easier to understand [45]. Alternatively, using models that provide inherent attention mechanisms, like Graph Attention Networks (GATs), can help visualize which input features (e.g., specific process parameters) the model deems most important [46].

FAQ 4: How can we integrate known physical laws into AI models to make them more reliable? Physics-Informed Machine Learning (PIML) and hybrid frameworks explicitly incorporate physical equations into the model's architecture or loss function [42]. Another approach is to use architectures like Interpolating Neural Networks (INNs), which blend numerical analysis methods (e.g., finite element shape functions) with deep learning, ensuring solutions adhere to physical constraints [47].

FAQ 5: We need to optimize multiple, often conflicting, properties (e.g., strength vs. cost). What AI method is suitable? Multi-objective optimization algorithms, such as Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective Optimization (TS-EMO), are designed for these scenarios. These algorithms can efficiently explore the parameter space and identify the Pareto front, which represents the optimal trade-offs between competing objectives [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inaccurate Flow Rate Predictions in Variable Material Printing

- Issue: The predictive model for flow rate in a screw-based material extrusion (S-MEX) process performs poorly when the material composition changes.

- Solution: Implement an Invertible Neural Network (INN).

- Methodology: An INN can learn the bidirectional relationship between process parameters and outcomes. It performs both forward prediction (e.g., predicting flow rate from screw speed and material composition) and inverse optimization (e.g., determining the required screw speed for a target flow rate) [41].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Collect a dataset of flow rate measurements across different screw speeds and material compositions (e.g., 0–40 wt% short carbon fiber reinforced PEEK).

- Model Setup: Construct an INN with input nodes for screw speed and material composition, and output nodes for flow rate.

- Training: Train the model using a loss function that minimizes the error in both the forward (flow rate prediction) and inverse (parameter estimation) directions.

- Validation: Validate the model's accuracy on a holdout dataset. Reported accuracies for INNs in this application can reach up to 0.852 for forward prediction and 0.877 for inverse optimization [41].

- Expected Outcome: A model that maintains consistent flow rate predictions during variable material printing, improving linewidth accuracy and reducing surface roughness [41].

Problem 2: Poor Characterization of Fiber Orientation in Composite Extrusion

- Issue: Traditional methods for analyzing fiber orientation from micrographs are too slow and costly for rapid process feedback.

- Solution: Use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) trained on synthetic images.

- Methodology: Generate a large, annotated dataset of synthetic SEM-like images with known fiber orientation tensors. Use this dataset to train a CNN to predict orientation tensors directly from real micrographs [42].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthetic Data Generation: Develop a Python algorithm to create binary images of fibers with controlled orientations, lengths, and overlaps. Generate a large dataset (e.g., 40,000 images) with corresponding orientation tensor values.

- CNN Architecture: Design a CNN with convolutional layers for feature extraction, followed by fully connected layers for regression to the orientation tensor components.

- Training & Validation: Train the CNN on the synthetic dataset and validate its predictions against orientation tensors calculated from traditional methods on real experimental images. This approach has achieved high accuracy (R² ≈ 0.989) [42].

- Expected Outcome: A rapid, automated, and accurate system for quantifying fiber orientation, enabling better prediction of anisotropic mechanical properties.

Problem 3: High Computational Cost of High-Resolution Process Simulation

- Issue: Traditional finite element method (FEM) simulations for processes like laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) at sub-10-micrometer resolution are computationally prohibitive.

- Solution: Employ an Interpolating Neural Network (INN) as a surrogate model.

- Methodology: INNs unify interpolation theory and tensor decomposition with neural networks. They discretize the input domain into a mesh and use message passing to create interpretable, adaptive interpolation functions [47].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Domain Discretization: Discretize the input domain (e.g., part geometry and process parameters) into a mesh.

- INN Construction: Construct the INN using interpolation functions (e.g., FEM-like shape functions) as activation functions.

- Model Training/Calibration: Train the INN on a limited set of high-fidelity simulation or experimental data to optimize the nodal values and coordinates.

- Simulation: Use the trained INN to predict system behavior (e.g., heat transfer) at high resolution. This method has been shown to be 5-8 orders of magnitude faster than competing ML models for achieving sub-10-micrometer resolution [47].

- Expected Outcome: Drastically reduced simulation times, enabling part-scale high-resolution modeling for online control and optimization.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Models in Polymer Research

| AI Model | Application | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invertible Neural Network (INN) | Flow rate prediction & inverse process optimization in S-MEX | Forward Prediction Accuracy | 0.852 | [41] |

| Inverse Optimization Accuracy | 0.877 | [41] | ||

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Fiber orientation tensor prediction from micrographs | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | ~0.989 | [42] |

| Interpolating Neural Network (INN) | High-resolution heat transfer simulation for L-PBF | Speedup vs. competing ML models | 5-8 orders of magnitude faster | [47] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Prediction of polymer properties | Generalization and feature extraction on complex structures | Effectively maps structure-property relationships | [43] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Polymer Extrusion Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Short Carbon Fiber Reinforced PEEK (SCF/PEEK) | A high-performance composite material used to develop and validate variable material printing models, such as those based on INNs [41]. |

| ABS with 20% Short Glass Fibers | A widely used composite for developing deep learning-based fiber orientation analysis methods, providing enhanced mechanical properties [42]. |

| Python-based Synthetic Image Generator | Algorithmic tool to create large datasets of synthetic SEM-like images with predefined fiber orientations for training CNNs, overcoming data scarcity [42]. |

| BigSMILES Notation | A standardized line notation for capturing polymer structures, including repeating units and branching, essential for creating consistent molecular descriptors for ML models [44]. |

| Chromatographic Response Function (CRF) | A scoring function, often a bottleneck in automation, used to guide ML algorithms in the optimization of analytical methods like liquid chromatography for polymers [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Polymer Synthesis using a Closed-Loop AI System This protocol outlines the use of AI for automated polymer synthesis and analysis [44].

- Setup: Integrate a flow chemistry reactor with inline analytical instruments (e.g., NMR, Size-Exclusion Chromatography).

- Parameter Definition: Define the adjustable synthesis variables (e.g., temperature, residence time, monomer composition) and the target properties (e.g., monomer conversion, molar mass dispersity).

- AI Model Integration: Employ a multi-objective optimization algorithm like TS-EMO. After each reaction, the algorithm uses the analytical data (e.g., from SEC and NMR) to predict the next best set of parameters to approach the Pareto optimum of the objectives.

- Iteration: The loop of synthesis, analysis, and AI-guided parameter suggestion continues automatically until convergence is achieved, efficiently exploring the high-dimensional parameter space.

Protocol 2: Developing a Deep Learning Model for Fiber Orientation Analysis This protocol details the steps for creating a CNN-based fiber orientation analyzer [42].

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate composite samples (e.g., ABS with 20% short glass fibers) using the MEX-LFAM process.

- Image Acquisition: Obtain polished cross-section images of the samples using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

- Synthetic Dataset Generation: Use a Python algorithm to generate a large dataset of synthetic SEM-like images with known, controlled fiber orientation tensors.

- Model Training: Train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) on the synthetic dataset to regress the fiber orientation tensor components directly from the input images.

- Validation: Validate the trained model's predictions against orientation tensors calculated from real SEM images using conventional methods.

Workflow Visualization

AI-Driven Polymer Analysis Workflow

Closed-Loop Polymer Optimization

Innovations in Screw Design for Enhanced Mixing and Energy Efficiency

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Common Extrusion Issues

Q1: My process is suffering from uneven mixing and poor dispersion of additives. What screw design factors should I investigate?

A: Uneven mixing is often related to insufficient distributive or dispersive mixing elements in your screw design.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your screw configuration. For dispersive mixing (splitting components), ensure the screw has elements that induce elongational flow, which is crucial for breaking up droplets in polymer blends. For distributive mixing (spreading components), the screw should have sections that efficiently redistribute the melt without excessive shear [48]. Modern optimization tools using genetic algorithms can help design mixing elements that balance these two functions while considering material-specific properties [48].

Q2: I am experiencing material degradation, evidenced by discoloration and a foul odor. How can my screw design be contributing to this?

A: Material degradation is typically caused by excessive heat or shear.

- Solution: Lower the barrel zone temperatures and reduce the screw speed. Furthermore, consider modifying the screw design itself. A lower compression ratio can reduce shear-induced heating. Implementing mixing sections designed for lower pressure drops and incorporating a screw with a shorter length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio can reduce the material's residence time in the barrel, minimizing the risk of thermal degradation [49] [19] [50].

Q3: My extrusion process has high and unstable energy consumption. Are there screw designs that can improve energy efficiency?