Optimizing Twin-Screw Extrusion Parameters for Advanced Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on optimizing twin-screw extruder (TSE) parameters.

Optimizing Twin-Screw Extrusion Parameters for Advanced Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on optimizing twin-screw extruder (TSE) parameters. It covers foundational principles of TSE operation and screw design, explores advanced methodological approaches for processing sensitive formulations, details evidence-based troubleshooting for common issues like overheating and poor mixing, and validates strategies using computational modeling and performance metrics. The content synthesizes current industry knowledge and research to equip scientists with practical strategies for enhancing process efficiency, product quality, and scalability in the development of solid dispersions, nanocomposites, and other advanced drug delivery systems.

Core Principles of Twin-Screw Extrusion and Screw Design for Pharmaceutical Processing

Understanding Co-rotating vs. Counter-rotating TSE Configurations and Their Applications

Twin-screw extruders (TSEs) are fundamental processing tools in pharmaceutical, chemical, and materials research. Their core function is to transport, mix, shear, and heat viscous materials in a continuous process. A critical design choice is the rotation direction of the twin screws, which defines two primary configurations: co-rotating and counter-rotating. Each configuration possesses distinct operating principles, leading to different performance characteristics and optimal application areas. Within the context of thesis research aimed at optimizing TSE parameters, understanding this fundamental distinction is the first step in designing effective experiments and correctly interpreting results. This guide provides a structured, technical support framework to help researchers navigate this choice and troubleshoot common issues.

Comparative Analysis: Co-rotating vs. Counter-rotating

The following table summarizes the core differences between co-rotating and counter-rotating twin-screw extruders, providing a quick reference for selection and troubleshooting.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Co-rotating and Counter-rotating TSEs

| Characteristic | Co-rotating TSE | Counter-rotating TSE |

|---|---|---|

| Rotation Direction | Both screws rotate in the same direction (clockwise or counter-clockwise) [1]. | Screws rotate in opposite directions (typically inward or outward) [1]. |

| Primary Material Transport | Material is transferred back and forth between screws in a figure-"8" pattern, creating an axially open system [2]. | Material is conveyed in closed, C-shaped chambers, acting like a positive-displacement pump [2]. |

| Mixing Mechanism & Efficiency | Excellent distributive mixing due to high material exchange between screws; V-shaped regions enable layer renewal [2]. | Good dispersive mixing; calendering effect in the nip region between screws squeezes particles [2]. |

| Shear & Energy Input | High shear rates and uniform energy input; suitable for compounding [2]. | Lower, less uniform shear; can generate high local pressure and heat in the intermeshing zone [2]. |

| Self-Cleaning Action | Excellent; screw crests tangentially wipe the flanks of the other screw with high relative velocity [2]. | Good; a calender-like roll-off motion occurs, but with lower relative velocity [2]. |

| Typical Operating Speed | High (e.g., 300 RPM or more) [2]. | Lower, to avoid excessive screw wear and pressure forces [2]. |

| Pressure Build-Up | Moderate; relies on die pressure to fill the screws. Often only the final section is fully filled [2]. | High; inherent positive-pumping action generates significant pressure [2]. |

| Common Research Applications | Compounding APIs with polymers, producing solid dispersions, blending immiscible polymers, devolatilization [1] [3] [2]. | Processing heat-sensitive or shear-sensitive materials, direct extrusion of profiles, PVC processing [2]. |

To aid in the initial selection process for an experiment, use the following decision flowchart.

Essential Research Toolkit

Successful experimentation with a TSE requires more than just the extruder itself. The table below lists key reagents, materials, and components referenced in experimental protocols, along with their critical functions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in TSE Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices (e.g., UHMWPE, HDPE, PP) | Act as the primary carrier or binder for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) or other additives. Their melt flow index (MFI) and compatibility are critical for processability [3]. |

| Compatibilizers (e.g., HDPE-g-SMA) | Chemical agents used to improve the adhesion and dispersion between immiscible phases, such as a hydrophobic API and a hydrophilic polymer, stabilizing the blend [3]. |

| API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) | The therapeutic compound being incorporated into a solid dispersion or composite matrix. Its particle size, melting point, and thermal stability are key parameters. |

| Screw Elements (Conveying, Kneading, Mixing) | Modular components that define the screw's action. Configurations are built from these to achieve specific sequences of feeding, melting, mixing, and pressurization [1]. |

| Twin-Screw Extruder (Modular) | The core apparatus. Its modularity allows for custom screw configuration, multiple feed ports, and venting zones, enabling complex processing sequences [1]. |

| Sortin1 | Sortin1|Vacuolar Trafficking Probe |

| Sotagliflozin | Sotagliflozin, CAS:1018899-04-1, MF:C21H25ClO5S, MW:424.9 g/mol |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Taguchi Optimization of TSE Parameters

The following section provides a detailed, citable methodology for systematically optimizing TSE processing parameters, a common objective in thesis research. This protocol is adapted from literature applying the Taguchi method to optimize a polymer composite for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) [3].

1. Experimental Objective: To determine the optimal set of TSE compounding parameters that yield a composite material with superior mechanical properties (e.g., tensile strength).

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Primary Materials: As required by your formulation (e.g., UHMWPE powder, 17 wt.% HDPE-g-SMA compatibilizer, 12 wt.% Polypropylene (PP)) [3].

- Equipment: Modular co-rotating twin-screw extruder, granulator, tensile tester.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Identify Control Factors and Levels. Select the key TSE process parameters you wish to optimize and define a minimum of two levels (values) for each.

- Example Factors: Screw speed (RPM), barrel temperature profile (e.g., Zone 1-5 °C), feed rate (kg/h).

- Step 2: Select an Orthogonal Array (OA). Choose a standard Taguchi OA (e.g., L9) that can accommodate the number of your control factors and their levels. This drastically reduces the number of experimental runs needed compared to a full factorial design.

- Step 3: Conduct Experimental Runs. Run the TSE according to the parameter combinations defined by the orthogonal array. Collect the resulting extrudate, pelletize, and, if necessary, form into test specimens via compression molding or a secondary process like FDM [3].

- Step 4: Measure Response Variable. Test the specimens according to the property of interest (e.g., perform tensile tests according to ASTM D638 to obtain Ultimate Tensile Strength).

- Step 5: Data Analysis (Signal-to-Noise Ratio). Calculate the Signal-to-Noise (S/N) ratio for each experimental run. For a "larger-is-better" quality characteristic like tensile strength, the S/N ratio is calculated as:

S/N = -10 * log10( Σ(1/y²) / n )whereyis the measured response (tensile strength) for each replicate andnis the number of replicates. - Step 6: Determine Optimal Factor Levels. Plot the average S/N ratio for each factor at its different levels. The level that yields the highest average S/N ratio is the optimal setting for that factor.

- Step 7: Confirmation Experiment. Conduct a final experimental run using the predicted optimal combination of factor levels to verify the improvement in the response variable.

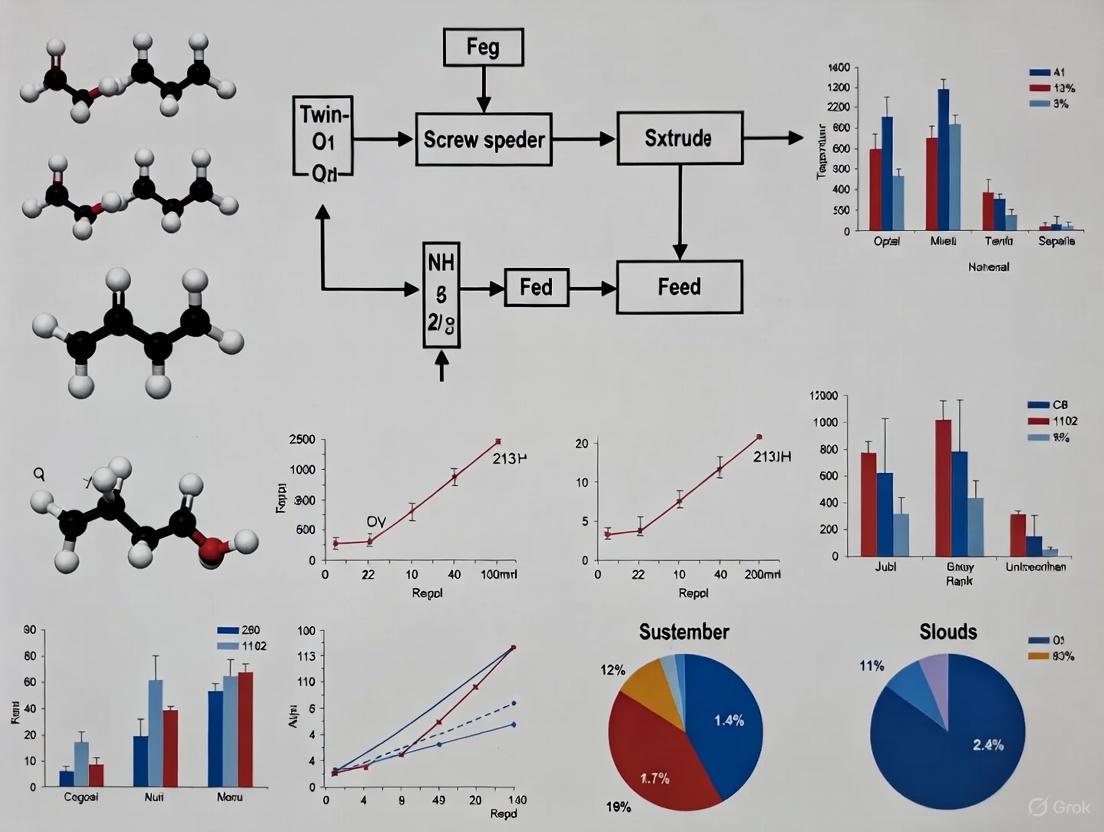

The workflow for this experimental design is visualized below.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I definitively choose a co-rotating TSE for my research? A1: A co-rotating TSE is the preferred choice when your primary goal involves intensive mixing. This includes applications like compounding APIs into polymers at high concentrations, creating homogeneous solid dispersions, blending immiscible polymers, and devolatilization (removing solvents or monomers) [2]. Its superior distributive mixing and self-wiping action make it versatile for most R&D applications where homogeneity is key.

Q2: My heat-sensitive API is degrading during extrusion. What configuration is more suitable and why? A2: A counter-rotating TSE is often better suited for heat-sensitive materials. Although it can generate high local pressure, its closed C-chamber conveyance typically results in a narrower residence time distribution and less intense overall shear heating compared to a co-rotating TSE running at high speeds. This reduces the risk of thermal degradation [2]. Furthermore, you can experiment with lower screw speeds in a counter-rotating setup, which further minimizes shear-induced heat.

Q3: What does the "self-cleaning" property of a TSE mean, and which configuration performs better? A3: Self-cleaning refers to the screws' ability to prevent material from adhering to the screw root and stagnating, which can lead to degradation and contamination. Both configurations are self-cleaning, but through different mechanisms. Co-rotating screws are generally more effective; one screw's crest wipes the flank of the other with a high, constant relative velocity, efficiently scraping off material. Counter-rotating screws use a calender-like roll-off motion, which is effective but has a lower relative velocity [2].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common TSE Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Mixing / Inhomogeneity |

|

|

| Material Degradation / Burning |

|

|

| Inconsistent Feed / Surging |

|

|

| Low Output Pressure / Unable to Form Strand |

|

|

Core Functions of Screw Elements

In twin-screw extrusion, screw elements are modular components assembled on the screw shaft to perform specific functions. Their primary roles are to convey material, and to achieve dispersive and distributive mixing, which are critical for creating a homogeneous product in pharmaceutical applications such as hot-melt extrusion for enhancing drug solubility [4] [5].

The table below summarizes the key functions and applications of the primary screw elements:

| Element Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Common Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conveying Elements | Transporting material along the barrel [4]. | Forward-pitched for efficient transport; reverse-pitched to create backflow and increase residence time [4]. | Initial material feeding and transport; controlling pressure and fill levels in different zones [5]. |

| Kneading Blocks | Dispersive Mixing: Breaking down particles and agglomerates (e.g., pigment clusters) through high shear [4]. | Staggered discs mounted at various angles; neutral blocks provide highest shear [4]. | Creating amorphous solid dispersions to improve API solubility; homogenizing polymer blends [4] [5]. |

| Gear Mixers | Distributive Mixing: Splitting and recombining material streams for uniform blending without high shear [4]. | Intermeshing teeth that minimize shear forces. | Blending heat-sensitive materials like PVC or biopolymers; ensuring uniform API distribution [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Mixing or Poor Homogeneity

Issue: The final product shows uneven distribution of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or excipients.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect Screw Configuration | Reconfigure the screw profile to include more or different mixing elements. Use kneading blocks for dispersive mixing and gear mixers for distributive mixing [4]. |

| Suboptimal Process Parameters | Adjust the screw speed (RPM) and feed rate. Higher screw speeds generally increase shear and mixing efficiency, but may degrade sensitive materials [4] [5]. |

| Inadequate Residence Time | Incorporate reverse-conveying elements or neutral kneading blocks to increase material backflow and extend residence time for more thorough mixing [4]. |

Problem: Material Degradation

Issue: The heat-sensitive API or polymer shows signs of thermal degradation.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessive Shear Heating | Reduce screw speed to lower mechanical shear. Replace high-shear kneading blocks with low-shear distributive mixers like gear mixers [4]. |

| Incorrect Barrel Temperature Profile | Optimize the temperature settings across the barrel zones to ensure the material is processed within its safe thermal range [5]. |

| Excessively Long Residence Time | Use forward-conveying elements to reduce backflow and lower the overall time the material spends in the extruder [4]. |

Problem: Unstable Extrusion Process

Issue: The process experiences pressure fluctuations, surging, or inconsistent output.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent Feed Rate | Ensure a consistent and controlled flow of material by using precision feeders like loss-in-weight feeders [5]. |

| Worn Screw Elements | Regularly inspect and replace worn screw elements, especially when processing abrasive compounds, to maintain consistent performance [5]. |

| Improper Pressure Buildup | Balance the screw configuration to ensure smooth pressure generation. Use a combination of forward and reverse elements to manage the melt pressure before the die [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the fundamental difference between single-screw and twin-screw extruders? A: Single-screw extruders primarily convey material and have limited mixing capability. Twin-screw extruders, with two intermeshing screws, provide superior mixing, kneading, and self-cleaning action, offering much better control over shear, residence time, and temperature, which is crucial for complex pharmaceutical formulations [5] [6].

Q: How does screw design affect the mixing capabilities of a twin-screw extruder? A: The screw design, specifically the arrangement of conveying, kneading, and mixing elements, directly determines the balance between dispersive and distributive mixing, the shear intensity, and the residence time of the material. A well-designed screw profile is tailored to the specific material properties and desired final product characteristics [4] [5].

Q: What is "residence time" and why is it important? A: Residence time is the duration that the material remains inside the extruder. It is critical for ensuring complete melting, homogenization, and any required chemical reactions. Precise control over residence time helps prevent the degradation of heat-sensitive APIs [4] [5].

Q: What is the role of kneading blocks and how are they configured? A: Kneading blocks are essential for applying shear to the material. They are configured at different stagger angles (forward, neutral, or reverse) to control the intensity of shear and the degree of backflow, which influences mixing and residence time [4].

Q: How can the extrusion process be optimized for a new formulation? A: Optimization involves a systematic approach: 1) Understand the material properties (viscosity, thermal stability); 2) Design a screw profile that targets the required mixing type; 3) Define key process parameters (temperature profile, screw speed, feed rate); and 4) Use modeling and iterative testing to refine the setup [5] [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Characterizing Screw Element Performance for Newtonian and Shear-Thinning Fluids

This methodology is based on a framework for determining specific screw parameters to enable in-silico screw optimization [7].

Objective: To characterize the pressure and power generation of individual conveying and kneading elements using both Newtonian and shear-thinning model materials.

Materials and Equipment:

- Test Rig: A custom-made extruder setup capable of measuring pressure and torque.

- Model Materials: Newtonian fluid (e.g., silicon oil) and a shear-thinning fluid (e.g., silicon rubber).

- Data Acquisition System: To record pressure, volume flow, torque, and screw speed.

Methodology:

- Element Testing: For each screw element (e.g., conveying elements, kneading blocks), conduct experiments where the volume flow (( \dot{V} )) is varied at a constant screw speed (( n )).

- Data Collection: Record the pressure gradient (( \Delta p )) and power (( P )) for each set of conditions.

- Parameter Calculation: Calculate the following dimensionless numbers for Newtonian fluids [7]:

- Dimensionless Volume Flow: ( \dot{V}^* = \frac{\dot{V}}{n \cdot d^3} )

- Dimensionless Pressure: ( \Delta p^* = \frac{\Delta p \cdot d}{l \cdot n \cdot \eta} )

- Dimensionless Power: ( P^* = \frac{M \cdot 2 \cdot \pi \cdot n}{l \cdot n^2 \cdot d^2 \cdot \eta} )

Where ( d ) is the barrel diameter, ( l ) is the length of the screw element, and ( \eta ) is the viscosity.

- Screw Parameters: The behavior is modeled using geometry-specific parameters ( A1, A2, A3 ) (for pressure) and ( B1, B2, B3 ) (for power), which are derived from the experimental data [7].

Expected Outcome: A set of characterized screw parameters that allow for the prediction of element performance under various process conditions, forming the basis for mechanistic 1D modeling.

Quantitative Data from Experimental Characterization

The table below provides an example of the screw parameters that can be determined experimentally for 1D modeling, as demonstrated in recent research [7].

| Screw Parameter | Description | Role in Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Dimensionless inherent throughput (at Δp*=0) [7]. | Defines the maximum possible conveying capacity of the screw element under drag flow. |

| A2 | Maximal dimensionless pressure build-up (at VË™*=0) [7]. | Defines the maximum pressure generation capability of the element when the outlet is closed. |

| A3 | Screw-specific correlation factor for shear rate in shear-thinning fluids [7]. | Captures the effect of screw geometry on the shear rate for pressure characteristics. |

| B1 | The turbine point where energy transfer changes direction [7]. | Classifies the power consumption behavior between pressure flow and drag flow. |

| B2 | Dimensionless power input for a closed die (at VË™*=0) [7]. | Defines the power consumption under maximum pressure conditions. |

| B3 | Parameter capturing shear-thinning effects on power, independent of throughput [7]. | Quantifies how screw geometry influences the shear rate for power characteristics in shear-thinning fluids. |

Process Visualization

Twin-Screw Configuration Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for configuring a twin-screw profile based on processing goals.

Experimental Workflow for Screw Characterization

This diagram outlines the experimental workflow for characterizing screw elements, a key step in research and optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and software used in advanced extrusion research, particularly for mechanistic modeling and process characterization.

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Newtonian Calibration Fluid (e.g., Silicon Oil) | Serves as a reference material with constant viscosity to characterize the baseline geometric parameters (A1, A2, B1, B2) of screw elements without the complicating effects of shear-thinning [7]. |

| Shear-Thinning Model Fluid (e.g., Silicon Rubber) | Used to study and model the behavior of complex, non-Newtonian materials, enabling the determination of additional screw parameters (A3, B3) that account for shear-rate dependence [7]. |

| Custom Test Rig with Data Acquisition | A modular extruder setup instrumented with pressure transducers and torque sensors to collect high-fidelity data for screw element characterization under controlled conditions [7]. |

| 1D Modeling Software (e.g., Ludovic) | Mechanistic software that uses characterized screw parameters to rapidly simulate the entire extrusion process (pressure, temperature, fill level) along the screw axis, enabling in-silico optimization [7]. |

| Carreau-Arrhenius Viscosity Model | A mathematical model used to describe the viscosity of shear-thinning materials as a function of both shear rate and temperature, which is essential for accurate process simulation [7]. |

| SP4206 | SP4206, MF:C30H37Cl2N7O6, MW:662.6 g/mol |

| Spinorphin | Spinorphin, CAS:137201-62-8, MF:C45H64N8O10, MW:877.0 g/mol |

How Kneading Block Geometry Governs Distributive and Dispersive Mixing Mechanisms

FAQs: Understanding Kneading Block Fundamentals

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between how a kneading block facilitates distributive and dispersive mixing?

Dispersive mixing involves the breaking apart of agglomerates or droplets by applying high shear and elongational stresses, effectively reducing the size of the minor component. Distributive mixing, in contrast, involves the spatial re-arrangement and homogenization of components without necessarily reducing their size, achieved by repeatedly dividing and reorienting the melt [8]. The geometry of a kneading block directly controls the balance between these mechanisms by governing the local shear rates, residence times, and the reorientation of the material flow [9].

Q2: How does the stagger angle of kneading discs influence mixing performance?

The stagger angle is a primary geometric factor controlling the trade-off between dispersive and distributive mixing. The table below summarizes the general effects of different stagger angles based on numerical simulations [9] [10]:

Table 1: Influence of Kneading Block Stagger Angle on Mixing Performance

| Stagger Angle | Mixing Characteristic | Shear Rate | Residence Time | Pressure Build | Primary Mixing Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward (e.g., +45°) | Conveying, gentle mixing | Moderate | Lower | Low | Distributive |

| Neutral (90°) | Balanced mixing | High | Moderate | High | Both Dispersive & Distributive |

| Reverse (e.g., -45°) | High restriction, aggressive mixing | Very High | Longer | Very High | Dispersive |

Q3: Besides stagger angle, what other geometric parameters are critical for kneading block design?

Other key parameters include:

- Number of Discs: A higher number of discs in a block generally increases the total shear and residence time, enhancing mixing completeness but at the cost of higher mechanical energy input and pressure drop [9].

- Disc Width: Narrower discs can create higher localized shear rates, which is beneficial for dispersive mixing, while wider discs may promote more distributive mixing [9] [10].

- Tip Clearance: The gap between the disc tip and the barrel wall influences leakage flow, which affects shear rates and mixing efficiency. A smaller clearance typically increases shear and dispersive mixing [10].

Q4: What advanced simulation techniques are used to analyze and optimize kneading block geometry?

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is the standard tool. Key methods include:

- 3D Finite Element Method (FEM): Software like POLYFLOW (Ansys) is used to solve the complex, non-Newtonian, and non-isothermal flow within the extruder, providing detailed velocity, pressure, and stress fields [11] [9] [12].

- Particle Tracking: By releasing virtual tracer particles in the simulated flow field, researchers can calculate metrics like Residence Time Distribution (RTD) and shear history to quantitatively evaluate mixing performance [11] [8].

- Mapping Method: This technique allows for the quantitative comparison and optimization of different screw layouts by providing volumetric mixing data, avoiding the need for exhaustive and costly experimental trials [11].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Issues and Solutions

Problem 1: Poor Dispersion of Fillers or Nanocomposites

Symptoms: Agglomerates in the final product, lower-than-expected mechanical properties (e.g., tensile strength), or inconsistent particle exfoliation as measured by SAXS [12].

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

- Confirm Screw Configuration: Verify that the kneading block setup is designed for dispersive mixing. A configuration with neutral (90°) stagger angles is often most effective [13] [9].

- Optimize Processing Conditions: Experimentally, a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach should be used. Key parameters to vary are screw speed and feed rate. Research shows that shear energy, not just diffusion time, is critical for exfoliating layered silicates like nanoclay [12].

- Validate with CFD: Use CFD simulation to identify regions of high shear stress and ensure the material is subjected to sufficient dispersive energy. Simulations can predict pressure profiles and dissipative energy input, allowing for optimization before physical trials [12].

Problem 2: Inadequate Distributive Mixing (Uneven Color or Additive Distribution)

Symptoms: Streaking, uneven color, or variable additive concentration in the extrudate.

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

- Re-evaluate Kneading Block Geometry: For better distributive mixing, consider using kneading blocks with a forward stagger angle (e.g., +45°). These geometries promote more reorientation and dividing of the melt stream with a lower risk of overheating [9].

- Implement On-Line Monitoring: To diagnose the issue in real-time, use an on-line optical monitoring system. As demonstrated in recent studies, this involves:

- Incorporating sampling devices along the barrel.

- Injecting a small amount of an immiscible polymer tracer (e.g., PA6 in a PS matrix).

- Measuring the turbidity and birefringence of the melt at various axial positions.

- Generating Residence Time Distribution (RTD) curves. The variance of the RTD curve can be used as an indicator of distributive mixing efficiency [8].

- Adjust Process Parameters: Increasing the screw speed can sometimes improve distributive mixing by increasing the number of reorientations, but be mindful of the corresponding reduction in residence time [13].

Problem 3: Overheating and Material Degradation in the Mixing Zone

Symptoms: Discoloration, black specs, foul odor, or a loss of mechanical properties in the final product.

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

- Check Kneading Block Intensity: Overly aggressive kneading blocks (e.g., reverse stagger) generate excessive shear heat. For heat-sensitive materials, switch to a less restrictive configuration [13] [14].

- Calibrate Temperature Settings: Use the polymer's thermal stability data to set maximum barrel temperature limits. Account for the additional shear-induced heat (viscous dissipation), which can cause the melt temperature to significantly exceed the set barrel temperature [13] [14].

- Verify Cooling System Efficiency: Ensure that the barrel cooling system is functioning correctly. For highly sensitive formulations, implementing or enhancing external cooling may be necessary to remove excess heat [13] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Quantifying Mixing Performance via On-Line Optical Monitoring

This protocol, adapted from recent research, allows for direct measurement of mixing kinetics along the screw axis [8].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for On-Line Optical Monitoring

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix (e.g., Polystyrene - PS) | Provides the continuous phase for the tracer. It is amorphous and has measurable flow birefringence. |

| Immiscible Polymer Tracer (e.g., Polyamide 6 - PA6) | Acts as a dispersed phase for creating turbidity. Its thermodynamic immiscibility is required for light scattering. |

| Optical Sampling Device | A modified barrel segment with slit dies and optical windows to laterally detour and test the melt. |

| Optical Detector | Measures normalized turbidity (for dispersion) and birefringence (for flow-induced orientation). |

Workflow:

- Setup: Modify a barrel segment to incorporate multiple sampling devices equipped with optical windows and detectors.

- Baseline: Process the base polymer (e.g., PS) until steady-state extrusion is reached.

- Tracer Introduction: Pulse a small amount of tracer material (e.g., PA6) into the feed.

- On-Line Measurement: Upon opening each sampling device, material is detoured and its turbidity and birefringence are measured simultaneously.

- Data Analysis: Construct RTD curves from the turbidity data at each axial location. The parameter K (area under the RTD curve) is used as an indicator of dispersive mixing, while the variance of the RTD curve assesses distributive mixing [8].

The following workflow outlines the experimental and simulation approaches for analyzing kneading block performance:

Protocol 2: CFD-Based Screw Design Optimization

This protocol uses simulation to reduce the need for extensive physical trials [11] [12].

Workflow:

- Geometry Creation: Create a 3D model of the proposed kneading block geometries (varying stagger angle, disc width, number of discs).

- Mesh Generation: Use a robust meshing technique like the Mesh Superposition Technique to handle the complex moving geometries efficiently [9].

- Define Material Model: Input accurate rheological data for the polymer (e.g., using a Bird-Carreau model) as a user-defined function in the CFD software (e.g., POLYFLOW) [12].

- Run Simulation: Solve the governing flow equations to obtain pressure profiles, velocity fields, and temperature distributions.

- Post-Processing: Use particle tracking to calculate mixing indices. Evaluate parameters such as shear rate distribution, residence time, and flux-weighted intensity of segregation to quantitatively compare different screw designs [11].

Performance Optimization Data

The following table consolidates quantitative findings from parametric studies to guide initial kneading block selection [9] [12] [10].

Table 3: Quantitative Guide to Kneading Block Geometry Performance

| Geometry Parameter | Configuration | Mixing Performance | Impact on Pressure & Energy | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stagger Angle | Reverse (-45°) | High dispersive mixing; Elongational flow. | High pressure drop; High mechanical energy input. | Breaking agglomerates; Dispersing fillers. |

| Neutral (90°) | Balanced dispersive/distributive; High shear. | Moderate-High pressure; High energy. | General-purpose compounding. | |

| Forward (+45°) | High distributive mixing; Conveying. | Low pressure build; Lower energy. | Blending; Color masterbatch. | |

| Number of Discs | 5 discs | Good compromise; Homogeneous distribution. | Lower pressure and energy consumption. | Distributive mixing dominance. |

| 10 discs | Enhanced dispersive mixing; Longer residence time. | ~25% higher dissipative energy [12]. | Difficult dispersive tasks. | |

| Tip Design | Pitched Tip | Improved distributive mixing; Enhanced inter-material exchange. | Slight reduction in pressure. | Blending immiscible polymers. |

FAQs on Key Process Parameters

What are the four key process parameters in twin-screw extrusion?

The four key process parameters in twin-screw extrusion are Screw Speed (RPM), Feed Rate, Barrel Temperature, and Residence Time. These parameters interdependently control the shear energy, material throughput, thermal stability, and the duration of mixing within the extruder, ultimately determining the quality and consistency of the final product [5] [16].

How does screw speed influence the extrusion process?

Screw speed directly controls the shear energy and mechanical energy input into the material. Higher screw speeds increase the shear forces, which enhances mixing but also raises the melt temperature through dissipative heating. This can be beneficial for mixing but risks degrading heat-sensitive materials if not carefully controlled [16] [12]. The screw speed also has an inverse, though relatively minor, relationship with the material's residence time in the extruder [16].

Why is the feed rate a critical parameter?

The feed rate determines the throughput and the degree of fill in the extruder screws. It has a significant impact on residence time; a higher feed rate reduces the average residence time and narrows the residence time distribution. An inconsistent feed rate is a primary cause of process surging, leading to variations in melt pressure and inconsistent product quality [13] [16].

What is the role of barrel temperature profiles?

Barrel temperature zones are meticulously controlled to facilitate melting, convey the material, and prevent degradation. Insufficient temperature can lead to poor mixing and high torque, while excessive temperature can cause thermal degradation of the polymer or active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), resulting in discoloration or loss of efficacy [13] [5].

How is residence time defined and controlled?

Residence time refers to the duration the material spends inside the extruder. It is controlled by the combination of screw speed, feed rate, and screw design. A longer residence time can allow for more complete mixing or chemical reactions but increases the risk of thermal degradation for sensitive components [5] [16]. Optimizing residence time is also a critical factor during scale-up to ensure process consistency [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Mixing and Dispersion

Issue: Inconsistent mixing and poor dispersion of fillers or APIs, leading to variations in product quality.

- Potential Causes:

- Incorrect screw configuration with insufficient mixing elements.

- Low barrel temperature in melting zones.

- Feed rate too high for the given screw speed, reducing residence time.

- Solutions:

- Re-evaluate and modify the screw configuration, particularly the number and angle of kneading blocks, to increase mixing intensity [13].

- Adjust barrel temperature zones to ensure complete melting and optimal viscosity for mixing [13].

- Optimize the ratio of feed rate to screw speed to ensure an adequate residence time for homogenization [16].

Problem 2: Material Degradation

Issue: Discoloration, foul odor, or reduced mechanical properties in the final product indicating thermal or shear degradation.

- Potential Causes:

- Excessive barrel temperature settings.

- Screw speed too high, generating excessive shear heat.

- Residence time too long for a heat-sensitive material.

- Solutions:

Problem 3: Process Surging

Issue: Fluctuations in melt pressure and product output, leading to dimensional inconsistencies.

- Potential Causes:

- Irregular feed rates due to feeder calibration or material bridging.

- Improper screw design that does not support stable material flow.

- Solutions:

Table 1: The Influence of Key Parameters on Process Outcomes

| Parameter | Directly Influences | Typical Impact on Melt Temperature | Impact on Residence Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw Speed | Shear Energy, Mechanical Energy Input | Increases significantly with higher speed [16] | Minor decrease with higher speed [16] |

| Feed Rate | Throughput, Degree of Fill | Minor influence | Major decrease with higher feed rate [16] |

| Barrel Temperature | Heat Transfer, Melt Viscosity | Direct correlation | Minor influence |

| Screw Design | Shear Intensity, Mixing Efficiency | Varies with element type (e.g., kneading blocks increase it) | Varies with element type (e.g., backward elements increase it) |

Table 2: Example Scale-Up Parameters from Lab to Production This table illustrates the adjustment of parameters when scaling up from a lab-scale (11 mm) to a larger pilot-scale (16 mm) extruder to maintain similar process conditions, based on a case study [16].

| Parameter | Lab-Scale Extruder (11 mm) | Initial Scale-Up (16 mm) | Adjusted Scale-Up (16 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 1.0 kg/h | 3.0 kg/h (theoretical) | 2.5 kg/h (adjusted) |

| Screw Speed | 200 rpm | 200 rpm | 200 rpm |

| Specific Energy | 559 kJ/kg | Much lower than target | 566 kJ/kg (matched to lab) |

| Residence Time | ~55 seconds | Much lower than target | ~55 seconds (matched to lab) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Residence Time Distribution (RTD)

Objective: To characterize the time distribution a material experiences within the extruder, which is critical for assessing mixing performance and degradation risk.

- Setup: Operate the extruder at the desired screw speed, feed rate, and temperature profile until a stable process is achieved.

- Tracer Injection: Introduce a small, sharp pulse of a tracer material (e.g., a colored pigment) into the feed stream at time zero.

- Sample Collection: At the die exit, collect small samples of the extrudate at very short, regular time intervals (e.g., every few seconds).

- Analysis: Analyze the tracer concentration in each sample (e.g., by color intensity measurement). Plot the concentration against time to obtain the Residence Time Distribution curve.

- Calculation: The mean of the distribution is the average residence time. The width of the curve indicates the mixing efficiency—a narrower curve suggests a more uniform residence time [16].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Screw Configuration for a Shear-Sensitive API

Objective: To design a screw configuration that minimizes degradation while ensuring adequate mixing for a heat-sensitive formulation.

- Baseline: Start with a standard screw configuration that includes aggressive kneading blocks.

- Process and Analyze: Process the formulation and measure the specific mechanical energy (SME) input and analyze the API for chemical stability (e.g., via HPLC).

- Modify Configuration: If degradation is observed, replace aggressive kneading blocks with milder mixing elements (e.g., toothed combing mixers) or increase the number of conveying elements to reduce residence time.

- Re-test and Compare: Process the formulation with the new configuration and compare the SME and API stability against the baseline. The goal is to find a configuration that provides sufficient mixing with the lowest possible SME and no API degradation [5] [12].

Parameter Interaction Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and feedback loops between the four key process parameters and critical outcome variables like shear energy and residence time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Extrusion Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder | The primary research equipment for continuous mixing and processing. | Lab-scale models (e.g., 11-18 mm screw diameter) are ideal for R&D with throughputs from 50 g/h to 10 kg/h [17]. |

| Gravimetric Feeder | Precisely meters solid raw materials (API, polymers, excipients) by weight for consistent feeding. | Critical for maintaining a stable feed rate and preventing process surging [13] [17]. |

| Modular Screw Elements | Allow for custom screw configurations to manipulate shear, mixing, and residence time. | Includes conveying elements, kneading blocks, and specialized mixing elements [13] [16]. |

| Polymer/Excipient Carrier | Acts as the matrix for incorporating the API. | Common examples include copolymers (e.g., Eudragit) for solid dispersions or lipids for heat-sensitive APIs [5] [17]. |

| Processing Aids | Additives used to modify the processability of the formulation. | Fluoropolymers can be used to reduce die buildup and melt fracture [13]. |

| CFD Modeling Software | Enables in-silico simulation and optimization of screw design and process parameters before physical trials. | Tools like Ansys Polyflow can predict pressure profiles and mixing index [13] [12]. |

| Spirapril | Spirapril, CAS:83647-97-6, MF:C22H30N2O5S2, MW:466.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| tc-e 5001 | tc-e 5001, MF:C20H19N5O3S, MW:409.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Impact of OD/ID Ratio and Screw Profile on Shear, Heat Transfer, and Mixing Efficiency

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the OD/ID ratio in a twin-screw extruder and why is it a critical design parameter? The OD/ID ratio is the ratio of the screw's Outside Diameter (OD) to its Inside Diameter (ID) [18]. This ratio is a fundamental design parameter as it simultaneously dictates the extruder's free volume (impacting throughput) and the size of the screw shaft (which determines the torque available for processing) [18] [19]. A higher OD/ID ratio (e.g., 1.76) results in deeper flight channels, providing more free volume and lower average shear rates, which is beneficial for high-volume feeding and gentle processing. A lower OD/ID ratio (e.g., 1.55) means a larger shaft diameter, providing higher torque and greater shear, suitable for demanding mixing applications [20] [19].

How do OD/ID ratio and screw profile specifically influence final product quality? The combined effect of the OD/ID ratio and screw profile directly controls the shear stress and thermal history experienced by the material, which are critical determinants of final product quality [21] [19]. An inappropriate combination can lead to product degradation (from excessive shear or temperature), incomplete mixing (from insufficient shear), or poor venting (from inadequate melt sealing). For instance, an aggressive screw profile paired with a low OD/ID ratio can generate excessive melt temperatures, leading to thermal degradation evidenced by smoking and discoloration [19]. Conversely, a gentle profile with a high OD/ID ratio might not provide enough dispersive mixing to break down agglomerates, resulting in an inhomogeneous product [21].

Table 1: Impact of OD/ID Ratio on Extruder Performance

| OD/ID Ratio | Free Volume | Torque Capacity | Shear Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.55 | Medium | High | High Shear | High-torque, high-speed compounding (e.g., alloys, masterbatches) [20]. |

| 1.66 | High | Moderate | Lower Shear, Milder Mixing | Lower specific energy input, resulting in lower melt temperatures [19]. |

| 1.76 | High | Low | Low Shear, Low Energy Input | Highly filled compounds, reactive extrusion, and devolatilization [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Melt Temperature and Product Degradation

- Observed Symptoms: Discoloration (yellowing/burning), smoking, gas formation, and a reduction in molecular weight of the polymer.

- Primary Causes: Excessive specific mechanical energy (SME) input into the material, caused by overly high screw speed or an incorrect screw profile and OD/ID ratio combination.

- Corrective Actions:

- Screw Profile: Transition from an aggressive melting zone (using neutral/wide kneading blocks and reverse elements) to an extended melting zone (using narrow-disk kneading blocks). Experiments show this can reduce melt temperature by 10°C to 30°C or more [19].

- OD/ID Ratio: If possible, select an extruder with a higher OD/ID ratio (e.g., 1.66/1 or 1.76/1). These geometries provide deeper flight screws that impart lower average shear and lower specific energy input (kWh/kg), naturally resulting in a lower melt temperature at the same throughput [20] [19].

- Process Parameters: Reduce screw speed (RPM) and optimize barrel temperature profiles to rely more on conductive heating and less on mechanical shear.

Problem: Inadequate Mixing (Dispersive or Distributive)

- Observed Symptoms: Unbroken filler agglomerates, uneven color distribution, or inconsistent API/excipient dispersion, leading to variable product performance.

- Primary Causes: Insufficient shear stress for dispersive mixing or insufficient interfacial renewal for distributive mixing.

- Corrective Actions:

- For Dispersive Mixing: Introduce or increase the number of wide kneading blocks (KBW) and reverse elements. These elements create restrictive zones that generate the high local shear stresses necessary to break apart agglomerates [21].

- For Distributive Mixing: Incorporate toothed mixing elements or narrow kneading blocks (KP). These elements primarily divide and recombine the melt stream, ensuring a homogeneous mixture without applying intense shear [21].

- OD/ID Ratio: A lower OD/ID ratio (e.g., 1.55) provides higher torque, which is often necessary to drive the high-shear elements required for effective dispersive mixing [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for troubleshooting these common extrusion issues, linking symptoms to their root causes and appropriate corrective strategies.

Figure 1: Troubleshooting Logic for Common Extrusion Issues

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Quantifying the Impact of OD/ID Ratio on Melt Temperature

1. Objective: To experimentally determine the relationship between the OD/ID ratio of a twin-screw extruder and the resulting polymer melt temperature at different throughputs.

2. Materials & Equipment:

- Extruders: Two twin-screw extruders with different OD/ID ratios (e.g., 1.5/1 and 1.66/1) but compatible gearboxes and screw diameters [19].

- Polymer Resin: Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) powder with a known Melt Flow Index (MFI 12) [19].

- Feeding System: Gravimetric feeder for consistent and controlled feeding.

- Temperature Measurement: Flushed and immersed melt temperature probes for accurate readings [19].

- Die: A low-pressure discharge die to minimize the effect of pressure on melt temperature [19].

3. Methodology:

- Fixed Parameters: Maintain a constant barrel temperature profile and screw speed (e.g., 400 RPM) across all experiments.

- Variable Parameter: Gradually increase the throughput (kg/h) for each extruder until a feed restriction is encountered or the machine's torque limit (e.g., 85%) is reached [19].

- Data Collection: At each throughput setting, record the screw speed, torque, and the stabilized melt temperature from both probes.

4. Expected Outcome: The extruder with the higher OD/ID ratio (1.66/1) will achieve a higher maximum throughput and will exhibit a lower melt temperature at equivalent throughputs due to its larger free volume and lower specific energy input [19].

Protocol: Evaluating Screw Profile Aggressiveness on Melt Temperature

1. Objective: To isolate and compare the thermal impact of "aggressive" versus "extended" melting zone screw configurations.

2. Materials & Equipment:

- Extruder: A single twin-screw extruder (e.g., ZSE-27 MAXX with 1.66/1 OD/ID ratio) [19].

- Polymer Resin: Polypropylene (PP) pellet resin (e.g., 2 MFI) [19].

- Screw Configurations:

- Diagnostic Equipment: Immersion melt temperature probe.

3. Methodology:

- Use a single set of kneading blocks after the melting zone in both configurations to isolate the effect of the melting zone itself.

- Process the resin with both screw profiles at multiple screw speeds (e.g., 200, 400, 600 RPM).

- For each test, optimize the barrel temperature profile and record the melt temperature once the process stabilizes.

4. Expected Outcome: The aggressive melting zone design will consistently result in significantly higher melt temperatures (e.g., 10°C to 30°C higher) compared to the extended design, due to the higher shear stress input [19].

Table 2: Screw Element Functions and Selection Guide

| Screw Element Type | Primary Function | Shear Effect | Pressure Build-Up | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conveying (SE 30/30) | Forward transport of material | Low | Low | Feeding solids and conveying melt [21]. |

| Kneading Block, Wide (KBW) | Dispersive Mixing | High (+++) | Medium | Breaking down filler/API agglomerates [21]. |

| Kneading Block, Narrow (KP) | Distributive Mixing | Medium (++) | Low to Medium | Blending polymers or APIs homogeneously [21]. |

| Reverse Element (SE 20/20 L) | Creates backflow and restriction | Very High | High (++) | Sealing sections for venting or enhancing mixing [21]. |

| Toothed Mixing Element (Z) | Distributive Mixing | Low (0) | Low | Efficiently blending solid and liquid ingredients [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Modular Co-rotating TSE | The primary research platform. Allows for flexible configuration of screw profiles and barrel length (L/D) to test various parameters [20] [22]. |

| Screw Element Kit | A collection of conveying, kneading, mixing, and reverse elements. Essential for building and testing custom screw profiles to optimize shear and mixing [21]. |

| Nickel Alloy Screws/Barrels | Specialized components offering exceptional wear resistance and corrosion protection. Critical for processing abrasive filled compounds or corrosive APIs without contaminating the product [23]. |

| Gravimetric Feeder | Provides precise and consistent feeding of raw materials (polymer, API, excipients). Essential for maintaining a stable process and achieving accurate formulation ratios [22]. |

| Melt Temperature Probe | A critical sensor for direct measurement of polymer melt temperature. An immersion probe is recommended for higher accuracy over a flushed probe [19]. |

| Vacuum Venting System | Used for devolatilization to remove moisture, air, solvents, or reaction by-products from the melt, thereby improving final product quality [20] [24]. |

| Teglarinad Chloride | Teglarinad Chloride, CAS:432037-57-5, MF:C30H43Cl2N5O8, MW:672.6 g/mol |

| Tegobuvir | Tegobuvir|HCV NS5B Polymerase Inhibitor|Research Use |

The following workflow diagram maps out the key stages and decision points in a systematic approach to optimizing twin-screw extrusion parameters for a research project.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Parameter Optimization

Advanced Methodologies for Process Parameter Optimization and Pharmaceutical Application

Systematic Optimization of Temperature Profiles for Heat-Sensitive APIs and Polymers

Troubleshooting Guides

How can I prevent thermal degradation of a heat-sensitive API during extrusion?

Problem: The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) shows signs of chemical breakdown, such as discoloration, loss of potency, or the formation of degradation by-products during the twin-screw extrusion process.

Solutions:

- Optimize Thermal Profile: Implement a gently rising or constant temperature profile along the extruder barrel. Avoid temperature peaks that can cause local overheating. The die temperature should be set close to the polymer's recommended processing temperature [25].

- Reduce Mechanical Shear: Lower the screw speed to reduce shear-induced heat. For very sensitive compounds, consider using a screw profile designed for gentle mixing (e.g., with wide-pitched elements and mild kneading blocks) to minimize dissipative heating [26].

- Employ a Twin-Stage Extruder: Utilize a system that decouples mixing from extrusion. A common configuration is a high-speed co-rotating twin-screw mixer (which operates at near-zero pressure) coupled with a low-speed single-screw extruder. This prevents the combination of high shear and high pressure that leads to overheating [27].

- Improve Cooling: Ensure the effectiveness of barrel cooling systems. For critical applications, consider specialized pelletizing methods like water-ring or underwater pelletizing, which provide immediate and rapid cooling of the extrudate, quenching heat instantly [27].

What should I do if I encounter uneven mixing or poor dispersion of the API in the polymer matrix?

Problem: The final extrudate shows inconsistent API distribution, leading to areas of high and low concentration, which compromises product quality and performance.

Solutions:

- Re-evaluate Screw Configuration: Increase mixing intensity by incorporating more or different kneading blocks in the screw design. The position and staggering angle of these blocks significantly impact distributive and dispersive mixing [26].

- Adjust Temperature Zones: Ensure the temperature in the melting and mixing zones is sufficiently high to lower the polymer's viscosity, which facilitates better blending and incorporation of the API [25] [26].

- Optimize Feed Rate: Use a starve-fed system and ensure a consistent feed rate. Inconsistent feeding can lead to surging and fill-level variations, which directly cause uneven mixing. Employ properly calibrated loss-in-weight feeders for precision [26].

Why is there melt fracture or surface imperfection on the extrudate?

Problem: The extrudate exiting the die has a rough, sharkskin-like, or irregular surface.

Solutions:

- Adjust Process Parameters: Reduce the screw speed to lower the shear stress and flow rate through the die. Simultaneously, increase the die temperature to reduce the melt viscosity [26].

- Modify Die Design: Increase the die land length or the die orifice diameter to reduce the shear rate at the wall. Using a die with a higher flow capacity can eliminate the instability causing melt fracture [26].

- Use Processing Aids: Incorporate additives, such as fluoropolymer-based processing aids, which can form a lubricating layer at the die wall, reducing shear stress and promoting smooth flow [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the fundamental types of temperature profiles in an extruder, and when should I use each?

There are three primary temperature profile configurations, each suited for different material systems and goals [25]:

| Profile Type | Description | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Rising Profile | Temperature increases steadily from the feed zone to the die. | A common, general-purpose profile; good for crystalline polymers as it provides gradual melting. |

| Constant Profile | A uniform temperature is maintained across all barrel zones. | Useful for maintaining a uniform melt temperature and for shear-sensitive materials. |

| Peak Profile | Temperature rises to a maximum in the middle zones then decreases towards the die. | Can be used to maximize mixing in the compression zone while preventing degradation at the die. |

For heat-sensitive APIs and polymers, a constant or gently rising profile is often recommended to avoid sharp thermal shocks. The "peak" profile should be used with caution, as the high-temperature zone can degrade sensitive compounds [25].

How does a twin-screw extruder's configuration impact heat management for sensitive materials?

The design of the twin-screw extruder offers several levers for managing thermal input:

- Co-rotating vs. Counter-rotating: Co-rotating twin-screw extruders are most common in pharmaceuticals and offer high mixing efficiency. Counter-rotating extruders can provide positive displacement pumping and are often used for heat-sensitive materials like PVC, as they can generate lower shear in the intermeshing region [28].

- Screw Geometry: Conical twin-screw extruders create a natural compression zone that can enhance melting efficiency at lower mechanical energy input. Modular parallel screws allow for custom configuration of mixing and conveying elements to optimize shear and residence time [29].

- Starve Feeding: Unlike flood-fed single-screw extruders, TSEs are typically starve-fed. This means the screw channels are only partially filled in the initial sections, giving the operator direct control over the residence time and shear history by adjusting the feed rate [28] [30].

What are the best practices for setting the initial temperature profile?

The initial parameterization should be based on material properties and systematic reasoning [25]:

- Feed Zone: Set the temperature significantly below the polymer's softening point to prevent premature melting and bridging. For many polymers, this is between 20°C and 60°C [25].

- Zone 1 (First Heating Zone): Set the temperature slightly above the melting point (for semi-crystalline polymers) or glass transition temperature (for amorphous polymers) to initiate melting and maximize the use of motor power for friction-based melting [25].

- Intermediate Zones (Zone 2 to n-1): Interpolate the temperatures between Zone 1 and the Die Zone, following one of the three standard profiles (rising, constant, or peak) [25].

- Die Zone (Zone n): Set to the manufacturer's recommended processing temperature. A general rule of thumb is 50–75°C above the melting point for semi-crystalline polymers or 100°C above the glass transition temperature for amorphous polymers [25].

Table: Initial Temperature Setting Guidelines Based on Polymer Type

| Polymer Type | Key Temperature Reference | Feed Zone Temp. | Die Zone Temp. (Rule of Thumb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Crystalline | Melting Temperature (Tm) | ~20-60°C | Tm + (50-75°C) |

| Amorphous | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | ~20-60°C | Tg + ~100°C |

What experimental protocols can I use to systematically optimize the temperature profile?

Protocol: Methodical Zone Optimization

Objective: To identify the optimal set temperature for each barrel zone that ensures complete melting and mixing while minimizing the thermal degradation of a heat-sensitive API.

- Baseline Establishment: Start with an initial profile based on the polymer's thermal properties (e.g., a constant profile at the recommended processing temperature) [25].

- Throughput and Stability Check: Set a conservative screw speed and feed rate. Run the process and observe the motor torque, melt pressure, and extrudate appearance. The process should be stable without surging.

- Zone-by-Zone Adjustment (One-Factor-at-a-Time):

- Feed Zone: If bridging occurs, decrease the temperature. If the motor torque is excessively high, a slight increase may help in some cases [25].

- Melting Zone (Typ. Zone 1/2): Gradually increase the temperature in small increments (e.g., 5°C). Observe the effect on motor torque. A significant drop in torque indicates improved melting. Stop when torque stabilizes.

- Mixing Zones: Adjust temperatures to achieve a homogeneous melt. Use a slightly higher temperature if dispersion is poor, but monitor closely for degradation.

- Die Zone: Adjust to achieve the desired melt strength and extrudate shape. A temperature that is too low may cause high die pressure and melt fracture, while one that is too high may cause bubbling or degradation.

- Validation: Once a candidate profile is identified, run the process for an extended period (e.g., 30-60 minutes). Collect samples at regular intervals for analysis (e.g., HPLC for API potency, DSC for solid state, dissolution testing). The process is optimized when the quality attributes are consistent and within specification over time [31].

The workflow for this systematic optimization is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and technologies crucial for developing and optimizing extrusion processes for heat-sensitive compounds.

Table: Key Materials and Technologies for Processing Heat-Sensitive APIs and Polymers

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) / Copovidone | Commonly used hydrophilic carriers for forming solid dispersions. They effectively inhibit recrystallization of the amorphous API and enhance dissolution kinetics. |

| PEG 6000 - 8000 (Polyethylene Glycol) | A low-melting-point polymer that acts as a plasticizer and processing aid, reducing the melt viscosity of the formulation and allowing for lower processing temperatures. |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | A cellulose-based polymer used for controlled-release formulations. It requires careful temperature control during extrusion due to its thermal sensitivity. |

| Twin-Stage Extruder | A specialized system combining a high-speed mixer with a low-speed extruder. It is essential for decoupling high-shear mixing from pressurized extrusion, drastically reducing thermal degradation risk [27]. |

| Water-Ring / Underwater Pelletizer | A pelletizing system where the extrudate is cut and immediately quenched in a water ring or directly underwater. This rapid cooling is critical for preserving the morphology of heat-sensitive melts [27]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Tools like near-infrared (NIR) or Raman spectroscopy probes placed inline after the die. They enable real-time monitoring of API concentration and potential degradation, facilitating immediate feedback and control [32]. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT, Vitamin E) | Additives that inhibit the oxidative degradation of both the polymer and the API, which can be accelerated by elevated temperatures during processing. |

| Telatinib | Telatinib, CAS:332012-40-5, MF:C20H16ClN5O3, MW:409.8 g/mol |

| Temephos | Temephos, CAS:3383-96-8, MF:C16H20O6P2S3, MW:466.5 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Decline in Product Quality

Observed Symptoms: Finished products may show surface defects like black spots or bubbles, color variation, dimensional fluctuations, or reduced mechanical properties such as insufficient tensile strength. These issues persist even when the extruder motor is functioning properly and the material formulation is unchanged [33].

Cause Analysis:

- Low-Performance Nozzles: Injection nozzles with poor atomization can cause local aggregation or poor dispersion of liquid additives, reducing formulation consistency [33].

- Incorrect Nozzle Positioning: Misplaced nozzles can result in localized overheating (causing carbonization) or insufficient heating (leading to incomplete melting) [33].

- Poor Nozzle Sealing: Aging or damaged seals can introduce impurities or air, forming surface bubbles in the final product [33].

Recommended Solutions:

- Use High-Quality Nozzles: Implement high-precision, patented liquid injection nozzles calibrated for precise spray angle and position to ensure full coverage of the melt flow path [33].

- Enhance Atomization: Utilize nozzles with atomized particle size ≤ 50 μm to significantly improve additive dispersion and product uniformity [33].

- Preventative Maintenance: Regularly inspect and replace aging nozzle seals to prevent contamination and air ingress [33].

Problem: Gel Formation

Observed Symptoms: Presence of gel-like substances in the final product, resulting in an uneven and undesirable texture that compromises product quality [15].

Cause Analysis:

- Material Degradation: Overheating or excessive shear can cause the polymer to degrade, forming gels [15].

- Suboptimal Formulation: Specific components within the material formulation may be prone to gel formation under certain processing conditions [15].

Recommended Solutions:

- Review Material Formulation: Regularly audit and adjust the material formulation to identify and eliminate components that promote gel formation [15].

- Optimize Processing Conditions: Maintain optimal barrel temperatures and screw speeds to prevent the thermal or shear-induced degradation that leads to gels forming on the screw and barrel [15].

Problem: Uneven Mixing and Poor Dispersion

Observed Symptoms: Inconsistent mixing and poor dispersion of fillers or liquid additives lead to variations in final product quality and compromised performance [26].

Cause Analysis:

- Improper Screw Configuration: The current arrangement of screw elements, particularly kneading blocks, is not providing adequate distributive or dispersive mixing [26].

- Incorrect Process Parameters: Insufficient barrel temperature or inaccurate feeding rates can prevent homogeneous integration of the liquid phase [26].

Recommended Solutions:

- Re-evaluate Screw Design: Optimize the screw configuration, especially the number, angle, and stagger of kneading blocks, to increase mixing intensity as required by the material's rheology [26].

- Adjust Process Parameters: Fine-tune barrel temperature zones and liquid feed rates to ensure the polymer is in the correct state for incorporation [26].

- Leverage Simulation: Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to simulate and fine-tune screw designs and process parameters before conducting physical experiments, saving time and resources [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor for achieving uniform dispersion of a liquid additive in a polymer melt? The most critical factor is ensuring high-precision atomization of the liquid phase. Using nozzles that produce an atomized particle size of ≤ 50 μm is essential for creating fine, evenly distributed droplets that can be homogenized into the melt, preventing localized aggregation and ensuring formulation consistency [33].

Q2: How can I optimize screw configuration for high-liquid phase formulations? Optimization involves strategically using mixing and kneading elements. Research indicates that replacing backward-conveying elements with forward-conveying mixing elements can reduce dissipative energy input by ~25% and lower pressure peaks (e.g., from 40 bar to 10 bar), which enhances residence time and filling efficiency for better liquid incorporation [12]. The specific arrangement should be tailored to the material's rheology, often with the aid of CFD simulations [26] [12].

Q3: What are the common signs of a failing liquid injection system? Key indicators include:

- Surface Defects: Bubbles, black spots (carbonized material), or gels in the extrudate [33] [15].

- Inconsistent Product: Variations in color, dimensions, or mechanical properties like tensile strength [33].

- Visible Leaks or Poor Sealing: Around the injection nozzle, which can introduce air or contaminants [33].

Q4: How does screw speed affect the incorporation of liquid additives? Screw speed directly influences shear energy and residence time. Higher screw speeds increase shear, which can improve the exfoliation of nanoscale additives but also raises the melt temperature, risking degradation. Conversely, lower speeds may provide longer residence time for diffusion but can reduce dispersive mixing power. An optimal balance must be found for each specific formulation [12].

Data Presentation: Key Process Parameters and Outcomes

The following table summarizes quantitative data related to the optimization of liquid and melt injection processes in twin-screw extrusion, as established in research.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters and Performance Outcomes

| Parameter | Standard Configuration | Optimized Configuration | Impact on Process/Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Additive Atomization | Not Specified | ≤ 50 μm particle size [33] | Drastically improved dispersion uniformity and product consistency [33]. |

| Pressure Peak | 40 bar | 10 bar [12] | Smoother flow, reduced mechanical stress, and lower risk of degradation [12]. |

| Dissipative Energy Input | Baseline | ~25% reduction [12] | Lower thermal load on the melt, beneficial for heat-sensitive materials [12]. |

| Screw Element Type | Backward Conveying | Forward Mixing/Kneading [12] | Enhanced residence time and filling efficiency for better liquid incorporation [12]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Verification of Mixing Efficiency via Screw Pull-Out

Objective: To experimentally verify the presence of starved (unfilled) zones and assess the distributive mixing performance of a specific screw configuration for a high-liquid phase formulation.

Materials:

- Twin-screw extruder (e.g., Leistritz ZSE 27 MAXX)

- Target polymer and liquid additive formulation

- Tools for screw pull-out

Methodology:

- CFD Simulation: Prior to the experiment, use a CFD simulation package (e.g., Ansys Polyflow) to model the pressure profile and mixing index along the length of the proposed screw design. Identify simulation-predicted zones of zero pressure, which indicate starved regions [12].

- Extrusion Run: Process the target formulation using the screw configuration of interest. Record key parameters: screw speed, temperature profiles, mass flow rate, and liquid injection rate.

- Screw Pull-Out: After achieving steady state, quickly stop the extruder and purge the barrel. Carefully pull the screw set out of the barrel while the material is still warm [12].

- Visual Analysis: Inspect the screw elements for the distribution and coating of the material.

- Filled Zones: Will be fully coated with a uniform layer of the compound.

- Starved Zones: Will appear partially empty or poorly coated, confirming the CFD simulation predictions [12].

- Validation: Correlate the physical observations from the pull-out with the simulated pressure and mixing index profiles to validate the screw design [12].

Protocol: Optimizing Nozzle Performance for Product Quality

Objective: To systematically eliminate product quality defects (bubbles, black spots, poor dispersion) originating from the liquid injection system.

Materials:

- High-precision liquid injection nozzle (atomization ≤ 50 μm)

- Compatible, high-quality nozzle seals

- Calibration tools for spray angle and position

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Run the extrusion process with the current nozzle and document the specific defects observed (e.g., count of black spots per unit area, measure of color variation).

- Nozzle Inspection and Replacement:

- Inspect the existing nozzle and seals for wear, damage, or clogging.

- Replace with a high-precision, patented nozzle designed for optimal atomization [33].

- Ensure new, high-quality seals are installed.

- Calibration:

- Precisely calibrate the nozzle's spray angle and positional alignment to ensure the injected liquid fully covers the polymer melt flow path within the barrel without impinging on the screw or barrel wall [33].

- Process Validation:

- Run the extrusion process with the optimized nozzle setup under identical conditions to the baseline.

- Quantitatively compare the finished product for the previously observed defects to measure improvement [33].

Process Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving issues related to high-liquid phase formulations in twin-screw extrusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Equipment Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for Liquid Injection Experiments

| Item | Function/Explanation | Critical Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Liquid Injection Nozzle | Introduces the liquid phase (additive, plasticizer) into the polymer melt in the barrel. | Atomization precision ≤ 50 μm for uniform dispersion; requires calibration of spray angle/position [33]. |

| Wear-Resistant Screw Elements | The screws, particularly kneading blocks, convey, melt, and mix the formulation. | Made from wear-resistant materials (e.g., nitrided and polished) to withstand abrasive fillers and maintain clearance [33] [26]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Models flow, pressure, and mixing in the extruder to optimize screw design and process parameters virtually. | Allows parameter variation without physical experiments; e.g., Ansys Polyflow package [12]. |

| Gravimetric Feeder | Precisely meters the solid polymer and/or filler feedstock into the extruder. | Ensures a consistent and accurate feed rate, which is critical for maintaining stable pressure and mixing [26]. |

| Purging Compound | Cleans the extruder barrel and screw between runs to prevent cross-contamination and material degradation build-up. | High-quality compound (e.g., Asaclean) maintains system cleanliness and prevents defects like gels [15]. |

| TS-021 | TS-021, MF:C17H24FN3O5S, MW:401.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TT01001 | TT01001, CAS:1022367-69-6, MF:C15H19Cl2N3O2S, MW:376.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Optimizing Screw Speed and Feed Rate to Control Shear and Residence Time Distribution

FAQs on Shear, Residence Time, and Process Control

1. How do screw speed and feed rate independently affect Residence Time Distribution (RTD)? Screw speed and feed rate are two primary operating variables that significantly impact RTD, which describes the range of time material spends inside the extruder [34]. Their effects can be summarized as follows:

- Feed Rate: This has a considerable influence on RTD. A larger feed rate (throughput) reduces both the average residence time and the width of the residence time distribution [16]. Essentially, pushing more material through the system flushes it out faster and with less variation in dwell times.

- Screw Speed: The screw speed has a relatively smaller, but still notable, influence on residence time [16]. While increasing screw speed can slightly shorten the average residence time, its effect is less pronounced than that of the feed rate.

The following table synthesizes experimental data on how these parameters affect key process outcomes:

Table 1: Effects of Screw Speed and Feed Rate on Extrusion Process Parameters

| Parameter | Effect on Average Residence Time | Effect on Residence Time Distribution Width | Effect on Melt Temperature | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Rate | Decrease [16] | Decrease (Narrows) [16] | Relatively smaller influence compared to screw speed [16] | Data from pharmaceutical and polymer compounding studies [35] [16]. |

| Screw Speed | Slight Decrease [16] | Variable (depends on configuration) | Increase (Higher mechanical energy input) [16] | Higher screw speeds provide more mechanical energy, resulting in a greater melt temperature [16]. |

2. What is the interaction between screw speed and feed rate, and how is it quantified? The interaction between screw speed and feed rate is captured by the Specific Feed Load (SFL), a dimensionless ratio that symbolizes the load inside the extruder. For a given material and screw configuration, it is defined as:

SFL = á¹ / (n Ï d³) [35]

Where:

- á¹ = Mass flow rate (feed rate)

- n = Screw speed

- Ï = Material density

- d = Barrel diameter

Maintaining a constant SFL while scaling up a process ensures that the fundamental flow conditions and degree of fill in the extruder are preserved, which helps in achieving consistent shear and mixing performance [35].

3. How does screw design influence shear and mixing? The screw configuration is a critical factor that can override the effects of basic operating parameters. Screw elements are modular and can be arranged to achieve specific processing objectives [7] [5].

- Conveying Elements: These elements primarily transport material forward with minimal mixing.

- Kneading Blocks: These elements introduce high shear and intensive mixing. They can be staggered at different angles to promote either dispersive mixing (breaking down particles) or distributive mixing (homogenizing components) [5].

- Reverse Conveying Elements: These elements create a deliberate obstruction to flow, increasing the filled length of the screw, the pressure build-up, and the residence time. This enhances mixing and energy input [16].

4. What are the best practices for scaling up processes while maintaining RTD and shear conditions? Scale-up from a laboratory-scale extruder to a larger production machine is a common challenge. The primary goal is to maintain similar thermal and shear histories. A recommended approach includes:

- Maintain Geometric Similarity: Use the same or similar screw configuration (sequence of elements) on the larger machine [16].

- Consistent SFL and Screw Speed: Start by using the same SFL and screw speed as the laboratory trial [16].

- Monitor Residence Time and Specific Energy: The residence time and specific energy input (SEI) are critical parameters for scale-up. Measure these on the larger machine and adjust the feed rate to match the SEI and residence time observed at the smaller scale, as the theoretical scale-up factor might require adjustment [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Excessive Shear Leading to Product Degradation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical degradation or unwanted physicochemical transformation of the API [36]. | Screw speed too high. Incorrect screw configuration (excessive use of kneading blocks). Barrel temperature profile set too high. | Reduce screw speed to lower mechanical energy input [16]. Modify screw design: Replace some kneading blocks with conveying or low-shear mixing elements [5]. Optimize temperature profile: Lower barrel temperatures, especially in the melting and mixing zones. |