Polymer Characterization Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern polymer characterization techniques, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Polymer Characterization Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern polymer characterization techniques, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores foundational methods, advanced applications for complex biomedical systems, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses, and a validated framework for technique selection. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance material understanding, accelerate formulation development, and ensure the reliability of polymeric materials in clinical applications.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Polymer Properties Shaping Biomedical Applications

Polymer characterization is a critical analytical branch of materials science that aims to understand the complex relationships between a polymer's structure, processing, and properties. This comprehensive analysis enables researchers to predict material performance, troubleshoot production issues, and develop new polymeric materials with tailored characteristics for specific applications across industries ranging from drug delivery systems to biodegradable packaging [1]. The fundamental parameters of interest include molecular weight, molecular structure, morphology, and thermal behavior, each of which requires specific analytical techniques for proper assessment [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the most widely used polymer characterization techniques, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate methods for their specific analytical needs.

The characterization challenge is particularly complex because most polymers are not simple, pure substances but complex mixtures containing additives, fillers, and sometimes blended polymers, all of which can significantly influence the final material properties [3]. Furthermore, polymerization reactions typically produce a distribution of molecular weights and shapes rather than uniform molecules, requiring specialized techniques that can account for this polydispersity [2]. As demands increase for better materials with specific performance characteristics, polymer analysis continues to evolve to meet the challenges of performance, safety, and sustainability [1].

Comparative Analysis of Key Characterization Techniques

Molecular Weight Determination Techniques

The molecular weight of a polymer is one of its most fundamental characteristics, influencing nearly all physical properties including mechanical strength, solubility, viscosity, and thermal behavior. Unlike small molecules, polymers exist with a distribution of molecular weights and shapes, making their characterization more complex [2]. The key parameters of interest include the number-average molecular weight (Mâ‚™), weight-average molecular weight (M_w), and polydispersity index (PDI), which describes the breadth of the molecular weight distribution.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Weight Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Typical Applications | Limitations | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)/Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Molecular weight distribution, Mâ‚™, M_w, PDI | Synthetic polymers, biopolymers, copolymers | Requires standards for relative MW; solvent dependence | Relative or absolute (with detectors) |

| Multi-angle Light Scattering (MALS) | Absolute molecular weight, radius of gyration | Polymer branching, biopolymers, complex architectures | Sensitive to dust and impurities; complex data analysis | Absolute |

| Viscometry | Intrinsic viscosity, molecular size | Quality control, polymer degradation studies | Indirect measurement; requires calibration | Relative |

| Melt Flow Rate (MFR) | Melt flow rate, melt volume rate | Polyolefins, thermoplastics processing | Limited to thermoplastics; empirical measurement | Relative |

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC), also known as size exclusion chromatography (SEC), is particularly valuable for directly determining molecular weight distribution parameters based on a polymer's hydrodynamic volume [2]. When GPC is coupled with multi-detector systems including multi-angle light scattering (MALS), viscometry, UV absorption, and differential refractometry, it enables absolute determination of molecular weight distribution independent of chromatographic separation details [2]. This multi-detector approach also provides information on branching ratio and degree of long chain branching in polymers [2].

For copolymers, molecular mass determination becomes significantly more complicated due to the differential effect of solvents on homopolymers and their impact on copolymer morphology [2]. Analysis of copolymers typically requires multiple characterization methods, with techniques like Analytical Temperature Rising Elution Fractionation (ATREF) being necessary for copolymers with short chain branching such as linear low-density polyethylene [2].

Melt flow rate (MFR) testing provides a relative measurement of polymer viscosity that correlates with molecular weight, where lower flow rates generally correspond to higher molecular weights [3]. For instance, commercial polycarbonate materials are available with melt flow rates ranging from 8 to over 30, with lower numbers indicating higher molecular weights that typically yield greater performance properties despite being more challenging to process [3].

Molecular Structure Analysis Techniques

Determining the molecular structure of polymers involves identifying common functional groups, monomer composition, and structural features such as tacticity and copolymer sequencing. The techniques used for polymer structure analysis are largely adapted from those used for characterizing unknown organic compounds but often require modifications to accommodate macromolecular systems [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Structure Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Structural Information Obtained | Sample Requirements | Quantitative Capabilities | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Functional groups, chemical bonds, additives | Solid, liquid, or film forms; minimal preparation | Semi-quantitative with calibration | Polymer identification, degradation studies |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Monomer sequence, tacticity, copolymer composition, branching | Soluble in appropriate deuterated solvents | Quantitative with proper parameters | Detailed structural elucidation |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Molecular vibrations, symmetry, crystallinity | Minimal sample preparation; non-destructive | Semi-quantitative with calibration | Complements FTIR; colored samples |

| Mass Spectrometry | Monomer mass, end groups, polymer fragmentation | Various ionization methods for polymers | Quantitative with standards | Polymer degradation mechanisms |

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy detects characteristic absorption patterns that reveal specific functional groups and additives present in a polymer system [1]. In recent studies, FTIR has been successfully employed to detect hydrogen bonding interactions in polymer blends, such as those between bio-based polybenzoxazine and polycaprolactone, where shifts in absorption peaks indicated intermolecular interactions between carbonyl groups of PCL and hydroxyl groups of PBZ [4].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides detailed insight into polymer backbone structure, tacticity, and copolymer composition [1]. Solid-state NMR has been particularly valuable for characterizing insoluble polymer systems, as demonstrated in research on bio-based benzoxazine resins where ¹³C solid-state NMR was used to confirm the chemical structure of both monomers and cured polymers [4].

Raman spectroscopy complements FTIR by identifying structural variations, especially in complex or colored samples where fluorescence might interfere with traditional IR measurements [1]. The combination of these spectroscopic techniques provides a comprehensive picture of polymer structure at the molecular level.

Morphological Characterization Techniques

Polymer morphology encompasses the arrangement of polymer chains at the microscale level, including crystalline and amorphous regions, phase separation in blends, and surface topography. These morphological features significantly influence mechanical properties, diffusion characteristics, and overall material performance [2].

Table 3: Comparison of Morphological Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Resolution Range | Primary Morphological Information | Sample Preparation Complexity | In Situ Capabilities* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | 0.5 nm - 100 μm | Surface topography, phase separation, mechanical properties | Minimal to moderate | Excellent |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | 1 nm - 1 mm | Surface morphology, fracture surfaces, filler distribution | Moderate (often requires coating) | Limited |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | 0.1 nm - 10 μm | Internal structure, crystalline domains, nanoparticle dispersion | High (ultra-thin sections required) | Limited |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | 0.1 nm - 100 nm | Crystal structure, crystallinity, crystal size | Minimal | Good |

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for studying polymer morphology due to its high spatial resolution at the nanometer-to-micrometer scale and low-destruction imaging capabilities [5]. AFM can visualize hierarchical polymer crystal structures including single crystals, spherulites, dendritic crystals, and shish-kebab crystals [5]. The technique operates in several modes, with tapping mode being especially valuable for soft polymer samples as it minimizes sample damage, while PeakForce mode enables simultaneous topography imaging and nanomechanical property mapping [5].

Recent advances in AFM technology have expanded its applications in polymer crystallization studies, including in situ monitoring of crystal growth processes and the analysis of structure-property relationships under thermal and mechanical stress [5]. Newer AFM techniques such as single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) and AFM-infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) combine topological imaging with chemical identification, enabling researchers to address fundamental questions in polymer crystallization at unprecedented resolution [5].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) remains invaluable for examining polymer morphology at micron to nanometer scales, particularly for understanding fracture surfaces and filler distribution. In studies of polystyrene-poly(methyl methacrylate) blends, SEM revealed that the degree of protrusion in phase-separated structures increased with molecular weight, forming snowman-like or Janus morphologies depending on the molecular weight and composition [6].

Thermal Analysis Techniques

Thermal analysis encompasses a range of techniques that measure polymer properties as a function of temperature, providing critical information about thermal stability, phase transitions, and curing behavior. These techniques are indispensable for determining processing conditions and predicting end-use performance [1].

Table 4: Comparison of Thermal Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Primary Measurements | Temperature Range | Sample Environment | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Tg, Tm, T_c, crystallinity, curing | -150°C to 600°C | Inert, oxidizing, or vacuum | Phase behavior, thermal history |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Thermal stability, composition, filler content | Ambient to 1000°C | Inert or oxidizing | Compositional analysis, degradation |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Viscoelastic properties, T_g, crosslink density | -150°C to 600°C | Various atmospheres | Structure-property relationships |

| Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) | Coefficient of thermal expansion, softening point | -150°C to 1000°C | Various atmospheres | Dimensional stability |

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) serves as a workhorse technique in polymer characterization, identifying thermal transitions such as melting, crystallization, and glass transitions [1] [2]. DSC is particularly valuable for determining the degree of crystallinity in semi-crystalline polymers and for studying curing processes in thermosets [2]. In polymer blend systems, DSC can detect shifts in glass transition temperatures that indicate partial miscibility between components, as demonstrated in bio-based polybenzoxazine and polycaprolactone blends where Tg values shifted depending on composition and molecular weight [4].

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) tracks weight loss due to thermal degradation or volatile release, providing information about polymer thermal stability and the effects of additives such as flame retardants [1] [2]. When combined with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) of the residual ash, TGA can provide comprehensive compositional analysis of complex polymer formulations, identifying inorganic fillers, flame retardant systems, and carbon black content [3].

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) measures the viscoelastic response of polymers under oscillatory stress, providing sensitive detection of glass transitions and secondary relaxations that may be missed by DSC [2]. DMA has been employed to study the thermal behavior of shape memory polymer systems based on bio-based polybenzoxazine and PCL, where changes in storage modulus and tan delta peaks indicated the influence of molecular weight on blend miscibility and thermomechanical properties [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Methods

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Protocol

Principle: GPC separates polymer molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume as they pass through a column packed with porous beads. Smaller molecules enter more pores and thus take longer paths through the column, while larger molecules are excluded from smaller pores and elute faster [2].

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve polymer sample in appropriate mobile phase (typically THF for synthetic polymers) at concentration of 1-2 mg/mL

- Filter solution through 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter to remove particulate matter

- Allow solution to equilibrate to room temperature before analysis

Instrument Parameters:

- Columns: Series of polystyrene-divinylbenzene columns with different pore sizes

- Mobile phase: HPLC-grade THF at flow rate of 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 35°C

- Detectors: Refractive index (RI), multi-angle light scattering (MALS), viscometer

- Injection volume: 100 μL

Data Analysis:

- Calibrate system using narrow dispersity polystyrene standards

- Determine molecular weight averages (Mâ‚™, M_w) and polydispersity index (PDI)

- For absolute molecular weights, use light scattering data with dn/dc values

- Analyze branching information from Mark-Houwink plots (log intrinsic viscosity vs log molecular weight)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Protocol

Principle: DSC measures the heat flow difference between a sample and reference as a function of temperature, detecting endothermic (melting) and exothermic (crystallization) transitions, as well as heat capacity changes at the glass transition [2].

Sample Preparation:

- Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of polymer sample using analytical balance

- Hermetically seal sample in aluminum crucible with lid

- Prepare empty reference pan identical to sample pan

Experimental Procedure:

- Equilibrate at -50°C (or 50°C below expected Tg)

- Heat from -50°C to 200°C at 10°C/min (first heating)

- Isothermal for 3 minutes to erase thermal history

- Cool from 200°C to -50°C at 10°C/min (cooling cycle)

- Heat from -50°C to 200°C at 10°C/min (second heating)

Data Analysis:

- From first heating: Identify glass transition temperature (Tg) as midpoint of heat capacity change, melting temperature (Tm), and crystallization temperature (Tc)

- From cooling cycle: Analyze crystallization behavior

- From second heating: Obtain thermal transitions free of processing history

- Calculate crystallinity using ΔHf/(ΔHf° × w), where ΔHf is experimental melting enthalpy, ΔHf° is theoretical enthalpy for 100% crystalline polymer, and w is polymer weight fraction

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Protocol for Polymer Morphology

Principle: AFM achieves nanoscale imaging by detecting interaction forces between a probe tip and sample surface, including van der Waals forces, electrostatic forces, and mechanical contact forces [5].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare smooth surface by spin-coating polymer solution (1-2% w/v) onto silicon wafer

- Alternatively, microtome thin sections (100-200 nm) from bulk samples using cryo-ultramicrotomy

- For crystalline polymers, isothermally crystallize from melt at controlled temperature

- Ensure sample surface is clean and relatively flat (irregularities preferably <1 μm)

Imaging Parameters:

- Mode: Tapping mode in air for soft polymers

- Cantilever: Silicon with resonant frequency of 200-400 kHz

- Scan rate: 0.5-1.5 Hz

- Resolution: 512 × 512 pixels

- Scan size: Typically 1 × 1 μm to 10 × 10 μm

Data Collection:

- Collect height images showing surface topography

- Acquire phase images revealing variations in material properties

- For crystalline polymers, analyze lamellar structure and crystal orientation

- Perform image analysis to determine surface roughness, domain sizes, and distribution

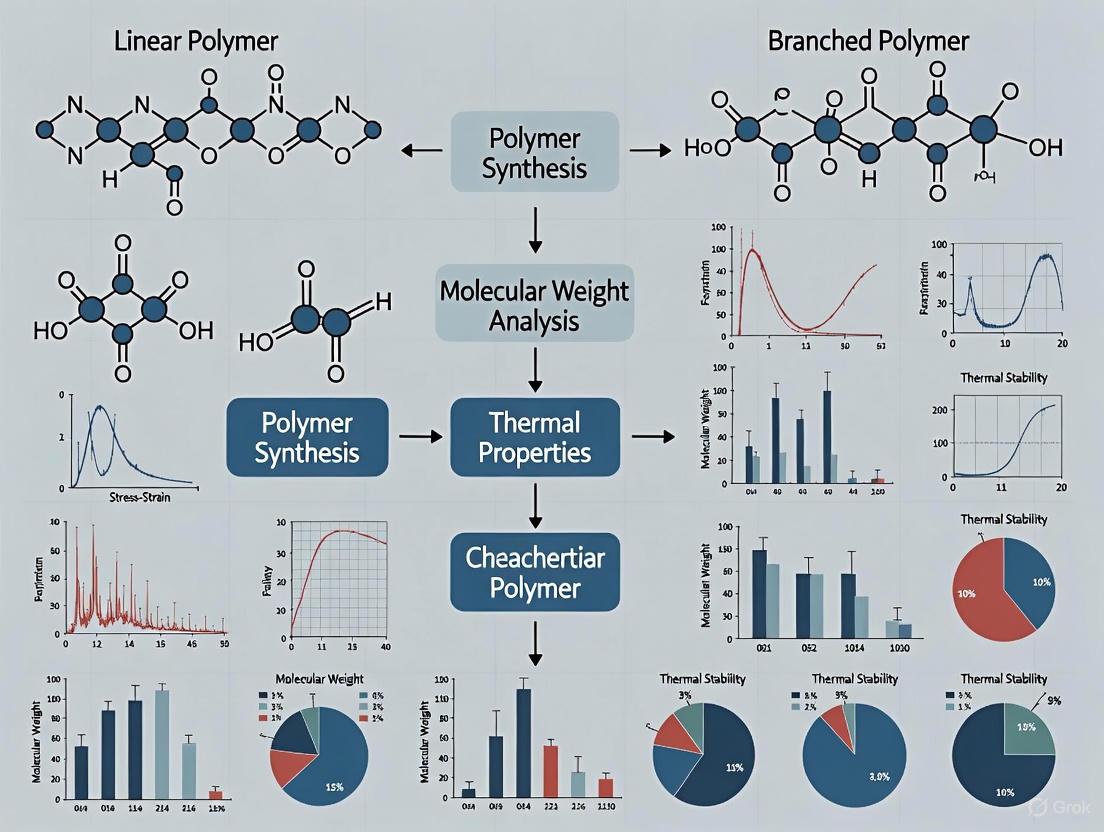

Visualization of Polymer Characterization Workflows

Polymer Characterization Technique Selection

Integrated Polymer Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Characterization

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | NMR solvent providing deuterium lock signal | Polymer structure determination by NMR | Purity, water content, chemical compatibility |

| HPLC-grade Solvents (THF, DMF, CHCl₃) | Mobile phases for chromatography | GPC/SEC, HPLC analysis of additives | Stabilizer content, water content, purity |

| Polystyrene Standards | Molecular weight calibration | GPC/SEC calibration | Narrow dispersity, certified values |

| Silicon Wafers | Atomically flat substrates | AFM sample preparation | Surface cleanliness, oxide layer |

| Conductive Coatings (Au, Pt, C) | Surface conductivity for EM | SEM sample preparation | Thickness control, uniformity |

| Ultramicrotome Knives (diamond, glass) | Thin sectioning | TEM, AFM sample preparation | Sharpness, angle adjustment |

| Calorimetry Standards (In, Zn, Ga) | Temperature and enthalpy calibration | DSC calibration | Purity, certified values |

| ATR Crystals (ZnSe, diamond, Ge) | Internal reflection element | FTIR spectroscopy | Hardness, spectral range, chemical resistance |

The comprehensive comparison of polymer characterization techniques presented in this guide demonstrates that a multi-technique approach is essential for complete polymer analysis. Each technique provides complementary information, with the most powerful insights emerging from the correlation of data across multiple analytical methods. Molecular weight determination techniques like GPC/MALS reveal the macromolecular architecture, while spectroscopic methods provide structural details at the molecular level. Morphological techniques visualize the arrangement of polymer chains at nano- to microscales, and thermal analysis connects these structural features to material performance under temperature variations.

The selection of appropriate characterization techniques must be guided by the specific information required, the nature of the polymer system, and the intended application of the data. As polymer systems continue to increase in complexity with the development of blends, composites, and bio-based alternatives, advanced characterization strategies that combine multiple techniques will become increasingly important. Furthermore, emerging technologies such as high-speed AFM, coupled spectroscopic-microscopy methods, and advanced computational data analysis promise to further enhance our understanding of structure-property relationships in polymeric materials, enabling the rational design of next-generation polymers with tailored performance characteristics.

The development and quality control of modern polymers, pharmaceuticals, and advanced materials rely heavily on robust analytical techniques for precise characterization. These methods provide critical insights into molecular structure, composition, thermal behavior, and physical morphology. Chromatographic, thermal, spectroscopic, and microscopic methods represent four foundational categories, each offering unique capabilities and applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on their operational principles, specific performance metrics, and applicability within industrial and research settings. The selection of an appropriate characterization strategy is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to establish reliable structure-property-processing relationships, optimize material performance, and accelerate discovery in fields such as polymer science and additive manufacturing [7].

The following table provides a high-level overview of the four major technique categories, highlighting their primary functions and common applications.

Table 1: Overview of Major Analytical Technique Categories

| Technique Category | Primary Function | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Methods | Separation of mixture components based on differential partitioning between mobile and stationary phases [8]. | Purification of biomolecules [8]; determining molecular weights of proteins [8]; analysis of drug compounds [9]. |

| Thermal Methods | Measurement of physical and chemical property changes as a function of temperature [10] [11]. | Determining melting points, glass transition temperatures, and thermal stability of polymers and pharmaceuticals [11]. |

| Spectroscopic Methods | Probing interactions between matter and electromagnetic radiation to determine structural and compositional information [12]. | Quantifying protein concentration [12]; ranking compound solubility [9]; studying molecular vibrations and rotations [12]. |

| Microscopic Methods | High-resolution imaging for morphological and topological analysis [13]. | Live-cell imaging [13]; surface structure analysis [13]; defect analysis in materials. |

In-Depth Technique Analysis and Performance Data

Chromatographic Methods

Chromatography encompasses a family of techniques that separate the components of a mixture for qualitative and quantitative analysis [8]. The separation is based on differential partitioning between a stationary phase and a mobile phase that carries the sample [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Chromatographic Techniques

| Technique | Separation Principle | Key Performance Metrics | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography (IEC) | Electrostatic interactions between charged molecules and an oppositely charged stationary phase [8]. | Binding capacity (mg/mL); elution pH/ionic strength [8]. | Separation of proteins, nucleotides, and other charged biomolecules [8]. |

| Gel-Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Molecular size in solution; smaller molecules enter pores and elute later [8]. | Molecular weight distribution (Ä); resolution between standards. | Determining molecular weights of proteins and synthetic polymers [8]. |

| Affinity Chromatography | Highly specific biological interactions (e.g., enzyme-substrate, antibody-antigen) [8]. | Purity yield (%); specificity; binding capacity. | Purification of enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids [8]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Various (size, charge, hydrophobicity) combined with high-pressure delivery for rapid analysis [8]. | Retention time (min); peak symmetry; plate count. | Separation and identification of amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids, and pharmaceuticals [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Aqueous Solubility Ranking via UV-Vis vs. HPLC

A comparative study evaluated rapid methods for ranking aqueous solubility using spectroscopic (UV-Vis, nephelometry) and chromatographic (HPLC) methods [9] [14].

- Sample Preparation: Compounds were pre-dissolved in DMSO and added to an aqueous solvent to achieve a final DMSO concentration of 5% (v/v). The samples were then filtered through poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) membranes [9].

- HPLC Analysis: The solubility determined by HPLC was used as the reference method for comparison [9] [14].

- UV-Vis Analysis: A 96-well UV-Vis plate reader was used in absorption mode to quantify dissolved compounds [9].

- Nephelometry Analysis: A 96-well nephelometric plate reader was used to measure light scattering, which correlates with the amount of precipitated compound [9].

- Data Correlation: The solubility rankings obtained from both UV-Vis absorption (using filtered samples) and nephelometry showed excellent agreement with HPLC results, with average correlations of 0.95 and r² = 0.97, respectively [9] [14]. This demonstrates that spectroscopic plate readers can serve as high-throughput substitutes for HPLC for solubility ranking in drug discovery [9].

Thermal Analysis Methods

Thermal analysis measures changes in material properties as a function of temperature, providing critical data on stability, composition, and phase transitions [10] [11].

Table 3: Comparison of Common Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Measurement Principle | Key Performance Metrics | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures heat flow into/out of a sample vs. reference during temperature scanning [10] [11]. | Tg, Tm, Tc (°C); ΔH (J/g); purity (%) [11]. | Melting point, crystallinity, glass transition, oxidation stability [11]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Measures mass change of a sample under controlled temperature program [10] [11]. | Onset decomposition T (°C); residual ash/ filler content (%) [11]. | Thermal stability, composition (moisture, filler, polymer content) [11]. |

| Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) | Measures dimensional changes (expansion/contraction) of a solid material under a light load [10] [11]. | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CLTE, µm/m·°C); softening point (°C) [11]. | Glass transition of highly crosslinked/filled polymers; CLTE of composites [11]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Applies oscillatory stress to measure viscoelastic properties [10] [11]. | Storage/Loss Modulus (E', E"); Tan δ; Tg (°C) [11]. | Full viscoelastic profiling; Tg detection with high sensitivity [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

The glass transition is a crucial property for polymers, and different thermal techniques can be used to measure it.

- DSC Protocol: A small sample (typically 5-10 mg) is sealed in a crucible. The sample and a reference are heated at a controlled rate (e.g., 10 °C/min). The Tg is identified as a step change in the heat flow curve, representing a change in heat capacity [11].

- TMA Protocol: A solid sample of defined geometry is placed under a minimal constant load. A probe rests on the sample, and the dimensional change is measured as the temperature is raised. The Tg is identified by a change in the slope of the expansion curve [11].

- DMA Protocol: A solid sample (e.g., in tension, bending, or compression mode) is subjected to a sinusoidal stress. The resulting strain is measured. The Tg is identified as a sharp peak in the Tan δ curve or a rapid drop in the Storage Modulus (E') [11]. DMA is recognized as the most sensitive method for detecting Tg, especially for subtle transitions [11].

Spectroscopic Methods

Spectroscopy involves the interaction of light with matter to obtain information about molecular structure, energy levels, and concentration [12].

Table 4: Comparison of Common Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Electromagnetic Region | Molecular Information | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Ultraviolet-Visible (190-800 nm) [12] | Electronic transitions of valence electrons (HOMO-LUMO) [12] | Wavelength (nm), Absorbance (AU) [12] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Ultraviolet-Visible- Near Infrared [12] | Emission from excited electronic states (relaxation) [12] | Wavelength (nm), Intensity (Counts) [12] |

| Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy | Infrared (~ 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹) [15] [12] | Molecular vibrations (stretching, bending) [12] | Wavenumber (cmâ»Â¹), % Transmittance [15] |

| Atomic Absorption (AA) Spectroscopy | Ultraviolet-Visible [15] | Electronic transitions in atoms (elemental analysis) [15] | Wavelength (nm), Absorbance (AU) [15] |

Experimental Protocol: Protein Concentration Assay via UV-Vis

UV-Vis spectroscopy is widely used for the quantitative analysis of biomolecules like proteins.

- Principle: The concentration of an absorbing species in solution is determined using the Beer-Lambert Law: A = ε c d, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹), c is concentration (M), and d is the pathlength (cm) [12].

- Procedure: A UV-Vis spectrometer with a deuterium or tungsten lamp source is used. The instrument is first zeroed with a blank solvent. The protein sample is placed in a cuvette, and the absorbance at 280 nm is measured. Aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine) in proteins absorb strongly at this wavelength [12].

- Calculation: The measured absorbance is applied to Beer's Law. The concentration is calculated using the known molar absorptivity (ε) for the specific protein or a standard curve. This method provides a rapid estimate of protein concentration, though accuracy can be affected by contaminants like nucleic acids [12].

Microscopic Methods

Microscopy provides high-resolution images for morphological and topological analysis, with techniques ranging from traditional light microscopy to advanced confocal systems [13].

Table 5: Comparison of Common Microscopic Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Key Capabilities | Ideal Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brightfield | Transmitted light passes through the sample [13]. | Basic imaging of stained or thick tissues [13]. | Histological sections (e.g., H&E stained) [13]. |

| Phase-Contrast | Converts phase shifts in light passing through a sample into brightness changes [13]. | Imaging of thin, unstained, transparent samples [13]. | Live cells in culture [13]. |

| Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) | Uses polarized light to create contrast from gradients in optical path length [13]. | High-resolution, high-contrast imaging with a pseudo-3D effect [13]. | Unstained live cells; subcellular organelles [13]. |

| Widefield Fluorescence | The entire sample is illuminated, and emitted fluorescence is captured [13]. | Multi-channel fluorescence imaging of fixed or live samples [13]. | Thin, low-scattering samples (bacteria, yeast, cell monolayers) [13]. |

| Confocal Microscopy | A pinhole is used to block out-of-focus light, creating optical sections [13]. | 3D reconstruction; imaging of thicker, more scattering samples [13]. | Tissue sections, 3D cell cultures, and highly specific structures [13]. |

Workflow and Technique Selection

The following diagram illustrates a generalized logical workflow for selecting an appropriate characterization technique based on the primary information requirement.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful characterization relies on the use of specific reagents and materials. The following table lists key items used in the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 6: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A polar aprotic solvent for pre-dissolving solid compounds for solubility studies [9]. | Used to prepare stock solutions of compounds before dilution into aqueous buffers for solubility ranking [9]. |

| PTFE Membrane Filter | A hydrophobic filter used to remove precipitated material from a solution prior to analysis [9]. | Filtration of aqueous compound solutions to ensure only dissolved analyte is measured in UV-Vis solubility assays [9]. |

| Cibacron Blue F3GA Dye | A dye-ligand used in affinity chromatography due to its structural analogy to NAD⺠[8]. | Acts as a biomimetic ligand for purifying dehydrogenases, kinases, and other NADâº-binding proteins [8]. |

| Sephadex G-type Media | A cross-linked dextran gel used as the stationary phase in size-exclusion chromatography [8]. | Used in gel-permeation chromatography to separate biomolecules and polymers based on their molecular size [8]. |

| Fluorescein | A common fluorescent dye used as a standard and tracer in fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy [12]. | Used to demonstrate Stokes shift, where its fluorescence emission is redshifted compared to its absorption spectrum [12]. |

Linking Polymer Microstructure to Macroscale Performance and Biocompatibility

The development of advanced polymers for biomedical applications—ranging from implantable devices and tissue engineering scaffolds to controlled drug delivery systems—requires a deep understanding of the intrinsic relationship between a material's microscopic structure and its macroscopic behavior. A polymer's performance, including its mechanical strength, degradation profile, and ultimately its biocompatibility, is fundamentally governed by its microstructural characteristics [16]. These characteristics include molecular weight, crystallinity, chain orientation, and the presence of specific functional groups.

Mastering the relationship between polymer microstructure and performance is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical requirement for designing safer and more effective medical devices and therapies. For instance, the hard-to-soft segment ratio in polyurethanes directly influences elasticity and histocompatibility [17], while the crystallinity of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) determines their degradation rate in physiological environments [18]. This guide provides a structured comparison of how key characterization techniques are employed to decode these structure-property-performance relationships, offering researchers a framework for selecting and evaluating polymeric materials.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Classes

Different polymer classes exhibit distinct microstructures, leading to varied performance profiles in biomedical applications. The table below summarizes key characteristics of several widely used biomedical polymers.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomedical Polymer Properties and Performance

| Polymer Class | Key Microstructural Features | Typical Mechanical Properties | Degradation Mechanism | Biocompatibility Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | Ester bonds in backbone, crystallinity tunable via processing [16]. | High strength, low flexibility; Modifiable via PCL blending [16]. | Hydrolytic cleavage of ester bonds; rate accelerated by temperature and catalysts [16]. | Generally good, but can provoke inflammatory reactions; PEG modification enhances histocompatibility [16]. |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | Aliphatic polyester, semi-crystalline [16]. | Ductile, low modulus, often blended to improve flexibility [16]. | Slow hydrolytic degradation, suitable for long-term implants [16]. | Biocompatible and bioresorbable; supports cell growth [16]. |

| PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates) | Family of polyesters; structure (e.g., PHB, PHBV) dictates properties [18]. | Brittle (PHB) to more flexible (copolymers); broad property range [18]. | Enzymatic and hydrolytic degradation; occurs in aquatic/soil environments [18]. | Excellent biocompatibility; degrades into non-toxic products [18]. |

| Polycarbonate Polyurethane (PCU) | Segmented copolymer with hard (rigid) and soft (elastic) domains [17]. | Hardness (Shore 65D-95A) and elasticity controlled by hard/soft segment ratio [17]. | High resistance to oxidative and hydrolytic degradation [17]. | Cell viability >70%; higher hard domain content promotes favorable cell adhesion and organization [17]. |

| TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane) | Segmented structure (isocyanate, polyol, chain extender); microphase separation occurs [17]. | Flexibility, toughness, and durability; properties depend on polyol type and segment ratio [17]. | Susceptibility varies by polyol type: polyester (hydrolysis), polyether (oxidation), polycarbonate (resistant) [17]. | Good biocompatibility; molecular structure resembles human tissue [17]. |

Essential Characterization Techniques and Workflows

Linking microstructure to macroscale properties requires a suite of complementary characterization techniques. The following experimental protocols are fundamental for a comprehensive polymer analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Methods

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Objective: To identify chemical functional groups and quantify phase separation in segmented polymers.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin films via solution casting or compression molding. For polyurethanes, cast films from a 20% polymer solution in dimethylacetamide at 60°C for 24 hours [17].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire spectra using a spectrometer (e.g., JASCO FTIR 4700) at a resolution of 4 cmâ»Â¹ over 16 scans [17].

- Data Analysis: Analyze specific vibration modes. For PCUs, calculate the Degree of Phase Separation (DPS) by integrating the hydrogen-bonded carbonyl peak (~1700 cmâ»Â¹) and the free carbonyl peak (~1735 cmâ»Â¹). DPS = HBI/(HBI+1), where HBI is the ratio of the two peak areas [17].

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

- Objective: To measure viscoelastic properties (storage modulus, loss modulus, tan δ) as a function of temperature and frequency.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare specimens of precise dimensions (e.g., from solution-cast sheets) [17].

- Testing Parameters: Use a tension mode clamp. Apply a fixed strain (e.g., 1%) within the linear viscoelastic region, determined by a prior strain sweep. Perform temperature ramps (e.g., -30°C to 200°C) or frequency sweeps at a constant temperature [17].

- Data Interpretation: The storage modulus indicates material stiffness. The tan δ peak corresponds to the glass transition temperature (Tg). For PCUs, storage modulus is influenced by hard domain content and increases at higher frequencies and lower temperatures [17].

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) & Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

- Objective: TGA determines thermal stability and decomposition temperatures, while DSC measures thermal transitions (Tg, melting point Tm, crystallinity).

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Place 5-10 mg of sample in an alumina crucible.

- TGA Method: Heat the sample from room temperature to 600-800°C under an inert nitrogen atmosphere. The weight loss curve reveals degradation steps [19].

- DSC Method: Use a heat-cool-reheat cycle (e.g., -30°C to 200°C at 10°C/min). The first heat erases thermal history; the second heat provides the material's intrinsic thermal properties. Crystallinity (%) is calculated from the melt enthalpy (ΔHf) relative to a 100% crystalline standard [20].

In Vitro Biocompatibility Testing

- Objective: To assess cellular response to the polymer, including cytotoxicity and cell adhesion.

- Protocol:

- Extract Preparation: Incubate sterile polymer samples in cell culture medium at 37°C for 24-72 hours to create an extract [21].

- Cell Culture: Seed relevant cell lines (e.g., Normal Human Lung Fibroblasts - NHLF) onto polymer films or in contact with extracts [17].

- Viability Assay: After 24-72 hours, assess cell viability using MTT assay, where viable cells reduce yellow MTT to purple formazan. Cell viability >70% is typically considered non-cytotoxic [17].

- Cell Morphology: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to visualize cell adhesion and morphology. Favorable surfaces promote homogeneous cell distribution and elongated morphologies [17].

Structure-Property Relationship Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for connecting characterization data to microstructure and final performance, integrating the techniques described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful polymer characterization relies on a set of core materials and instruments. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Characterization

| Item Name | Function / Role in Characterization | Specific Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Chronoflex C 65D (PCU) | Model polycarbonate polyurethane for implant applications; allows study of hard/soft segment effects [17]. | Used to correlate hard segment content with improved cell adhesion and mechanical strength [17]. |

| Carbothane AC-4095A (PCU) | Polycarbonate polyurethane with varying molecular weights; used to study the impact of molecular weight on performance [17]. | Two grades (MFI 4.3 & 7.1) compared for rheological behavior and tensile hysteresis [17]. |

| Dimethylacetamide (DMAc) | High-boiling polar solvent for preparing polymer solutions for solution-casting of test films [17]. | Used to create a 20% solution of PCU resins for casting films for DMA and tensile testing [17]. |

| Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) | A widely used biodegradable polyester; model polymer for studying hydrolysis and blending effects [16]. | PLA/PCL blends 3D-printed to tailor degradation rate and flexibility for tissue engineering [16]. |

| Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) | A common PHA; model biopolymer for studying biocompatibility and tunable degradation [18]. | Examined for degradation in marine environments and compost, showing effective decomposition [18]. |

| Waters ACQUITY APC System | Advanced Polymer Chromatography system for determining precise molecular weight and distribution [17]. | Used with tetrahydrofuran (THF) eluent to measure molecular weight of PCU resins [17]. |

| TA Instruments DMA Q800 | Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer for characterizing viscoelastic properties over temperature and time [17]. | Used in tension mode with 1% strain to measure storage modulus of PCU films [17]. |

| Discovery HR-2 Rheometer | Measures viscosity and viscoelastic properties of polymer melts or solutions under oscillatory shear [17]. | Used for viscosity frequency sweep tests of PCU resins at 200°C [17]. |

| Magl-IN-15 | Magl-IN-15|MAGL Inhibitor|For Research Use | Magl-IN-15 is a potent MAGL inhibitor for cancer, neurology, and pain research. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. |

| Cdk2-IN-23 | Cdk2-IN-23|Potent CDK2 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Cdk2-IN-23 is a potent, selective CDK2 inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The path to developing high-performance, biocompatible polymers is unequivocally guided by a rigorous understanding of microstructure-property relationships. As demonstrated, techniques like FTIR, DMA, and DSC are not standalone procedures but interconnected tools that, when used together, reveal a comprehensive picture of material behavior. The data shows that seemingly minor structural changes—a shift in the hard-to-soft segment ratio, a different copolymer composition, or a change in crystallinity—can profoundly alter mechanical performance, degradation profile, and cellular response.

Mastering these relationships enables a shift from empirical material selection to a rational design approach. This is critical for advancing biomedical applications, where safety and performance are paramount. Future work will continue to refine these characterization methodologies and integrate new computational modeling approaches to accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation polymeric materials for medicine.

Advanced Applications: Selecting and Implementing Techniques for Complex Drug Formulations

Chromatographic Methods (GPC, SGIC, 2D-LC) for Molecular Weight and Composition

Polymer characterization is a critical process in material science and pharmaceutical development, directly influencing product performance, stability, and quality. The complexity of synthetic polymers and biological macromolecules demands analytical techniques capable of resolving intricate molecular distributions. Chromatographic methods have emerged as powerful tools for deciphering these complexities, each offering unique capabilities for characterizing molecular weight and chemical composition. This guide objectively compares three prominent chromatographic techniques: Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), Solvent Gradient Interaction Chromatography (SGIC), and two-dimensional Liquid Chromatography (2D-LC). As the global 2D chromatography market expands significantly—projected to grow from USD 45.58 billion in 2024 to USD 81.29 billion by 2032—understanding the comparative strengths and applications of these techniques becomes increasingly vital for researchers and development professionals [22].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, outputs, and optimal applications of GPC, SGIC, and 2D-LC to provide a clear comparative overview.

Table 1: Comparison of Chromatographic Techniques for Polymer Characterization

| Feature | Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Solvent Gradient Interaction Chromatography (SGIC) | Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography (2D-LC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Mechanism | Size exclusion/ Hydrodynamic volume [23] | Chemical composition/ Polarity [24] | Orthogonal combination (e.g., SEC × RPLC, SCX × RPLC) [25] |

| Primary Output | Molecular weight distribution, Mn, Mw, Mz, Ä [26] | Chemical composition distribution [24] | Bivariate distribution (e.g., chemical composition vs. molar mass) [24] |

| Typical Detectors | RID, UV, Light Scattering, Viscometer [27] | IR detector (e.g., IR5, IR6) [24] | DAD, MS, IR [25] |

| Key Measurables | Molecular weight averages, dispersity, intrinsic viscosity, branching [27] | Short-chain branching frequency, comonomer content [24] | Assembly homogeneity, strand composition, charge/size variants [28] |

| Optimal Application | Polymer molecular weight and size distribution [23] | Heterogeneous polyolefins, copolymer composition [24] | Complex biopharmaceuticals (mAbs, ADCs), RNA nanoparticles [25] [28] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

GPC, also known as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), separates molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume or size in solution [23]. The experimental protocol involves several standardized steps:

- Sample Preparation: The polymer sample is dissolved in an appropriate organic solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran (THF) for synthetic polymers at room temperature, or trichlorobenzene at 130–150 °C for crystalline polyalkynes) to create a homogeneous solution. Typical concentrations range from 0.5 to 2 mg/mL. The solution is often filtered to remove dust or particulates that could damage columns or interfere with detection [23] [27].

- Column Selection: The choice of column is dictated by the polymer's molecular weight range. Columns are packed with porous gel beads (e.g., cross-linked polystyrene-divinylbenzene). For broad molecular weight distributions, multiple columns with different pore sizes may be connected in series [23] [26].

- Instrumentation and Analysis: The sample solution is injected into a mobile phase stream (eluent) delivered by a high-precision pump. The eluent carries the sample through the column, where larger molecules elute first because they are excluded from the pores, while smaller molecules penetrate the pores and elute later. A constant, pulseless flow rate (e.g., 1 mL/min) is critical for accurate calibration [23] [27].

- Detection and Calibration: The eluting sample is detected using concentration-sensitive detectors like a Differential Refractometer (DRI) or UV detector. For advanced characterization, molecular weight-sensitive detectors like a Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) detector or a viscometer can be added. A calibration curve is created using monodisperse polymer standards (e.g., narrow dispersity polystyrene) to relate retention time to molecular weight [23] [26] [27].

Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography (2D-LC)

2D-LC combines two orthogonal separation mechanisms to achieve a peak capacity that is the product of the peak capacities of each dimension, dramatically enhancing resolution for complex samples [29]. A key application is the analysis of RNA nanoparticles (RNA NPs):

- First Dimension Separation (Assembly Homogeneity): Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is employed in the first dimension under native conditions to separate fully assembled RNA NPs from partially assembled intermediates and single-strand impurities based on their hydrodynamic size. This step assesses the assembly efficiency and thermodynamic stability of the nanoparticles under physiological conditions [28].

- Modulation and Transfer: The effluent from the first dimension containing the separated fractions is systematically transferred ("heart-cutting" or comprehensive mode) to the second dimension via a switching valve equipped with a sample loop [25].

- Second Dimension Separation (Strand Composition): Ion-pairing reversed-phase (IPRP) chromatography serves as the second dimension. This step further separates the components based on hydrophobicity, identifying individual component strands and quantifying key impurities, such as antisense strands, within the peak of interest from the first dimension [28].

- Detection and Data Analysis: The eluent from the second dimension is directed to detectors such as a diode array detector (DAD) and/or a mass spectrometer (MS). The data is compiled into a contour plot, providing a two-dimensional map (e.g., SEC retention time vs. IPRP retention time) that visualizes the assembly homogeneity and strand composition uniformity [28].

Solvent Gradient Interaction Chromatography (SGIC)

SGIC separates polymers based on their chemical composition or polarity through a gradient of solvents [24]. A typical protocol for analyzing polyolefins is as follows:

- Sample Preparation and Injection: The polymer sample (e.g., a high-impact polypropylene copolymer) is dissolved in a weak solvent at high temperature (e.g., 160°C). A specific amount of this solution is injected onto the first-dimension column [24].

- First Dimension SGIC Separation: A gradient of solvents is run on an interaction chromatography column (e.g., a Hypercarb column). For example, a gradient from decanol to 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene (TCB) over 100 minutes is used. Polymers interact with the stationary phase with different strengths based on their chemical composition (e.g., isotactic polypropylene is weakly retained, while polyethylene is strongly retained) [24].

- Fraction Transfer and Second Dimension GPC: Eluting fractions from the first dimension are captured at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 minutes) and automatically transferred to a second-dimension GPC column. This isocratic GPC separation then determines the molar mass distribution of each chemical composition fraction [24].

- Detection and Bivariate Analysis: An infrared detector (e.g., IR5 or IR6) is used after the second dimension to measure the chemical composition directly (e.g., methyl frequency for ethylene-propylene copolymers). The final result is a bivariate distribution plot showing both chemical composition and molar mass, revealing the microstructure of complex materials [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful characterization relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The table below lists key components used in these chromatographic workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Chromatographic Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| IR5/IR6 Detector | Measures concentration & chemical composition (e.g., methyl content, carbonyl groups) in polyolefins online after GPC or SGIC separation [24] [27]. | High sensitivity for detecting low branch levels; IR6 specifically measures carbonyls at 1740 cmâ»Â¹ [27]. |

| Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) Detector | Determines absolute molar mass without column calibration; enables long-chain branching characterization [27]. | Coupled with a concentration detector; provides radius of gyration [27]. |

| Viscometer Detector | Measures intrinsic viscosity (IV); used with GPC for universal calibration and Mark-Houwink plots [27]. | Capillary viscometer; provides IV as a function of molar mass [27]. |

| Hypercarb Column | Porous graphite carbon stationary phase for the first dimension of SGIC; separates by chemical composition [24]. | Used with solvent gradients (e.g., decanol to TCB) at high temperatures (160°C) [24]. |

| Polystyrene Standards | Narrow dispersity standards for calibrating GPC systems to determine relative molecular weights [23]. | Dispersities (Ã) typically < 1.2 [23]. |

| Specific Eluents | Mobile phases for dissolving samples and eluting columns. | THF for room-temperature GPC; TCB/O-DCB for high-temperature GPC (160°C) [23] [24]. |

| Nlrp3-IN-33 | Nlrp3-IN-33, MF:C21H19N3O5, MW:393.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mpo-IN-6 | Mpo-IN-6, MF:C16H12N2O6, MW:328.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for a comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography (LC×LC) analysis, integrating the steps of both separation dimensions.

Figure 1: Comprehensive 2D-LC Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process where a sample is first separated by one mechanism (e.g., chemical composition), with eluting fractions automatically transferred to a second column for orthogonal separation (e.g., by molar mass), followed by detection and data synthesis into a comprehensive bivariate distribution plot [29] [24].

GPC, SGIC, and 2D-LC each occupy a distinct and complementary role in the polymer characterization toolkit. GPC remains the fundamental technique for determining molecular weight and size distributions. In contrast, SGIC provides crucial chemical composition data for complex copolymers, revealing short-chain branching and comonomer distribution. The power of 2D-LC lies in its ability to integrate these orthogonal separations, generating a comprehensive bivariate distribution that is indispensable for characterizing the most sophisticated materials, from heterogeneous polyolefins to advanced biopharmaceuticals like monoclonal antibodies and RNA nanoparticles. The choice of technique depends fundamentally on the specific analytical question—whether it concerns molecular size, chemical makeup, or the intricate relationship between the two. As polymers and biotherapeutics grow in complexity, the adoption of these multidimensional analytical strategies, particularly 2D-LC, will continue to be a critical driver of innovation and quality control in research and development.

Thermal Analysis (DSC, TGA, HyperDSC) for Stability and Transitions

Thermal analysis is a fundamental branch of materials science that investigates how material properties change with temperature. For researchers characterizing polymers and pharmaceuticals, techniques such as Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), and HyperDSC provide critical insights into thermal stability, phase transitions, and compositional integrity. These methods are indispensable for quality control, product development, and failure analysis across diverse industries [30].

While DSC and TGA are established as workhorse techniques in most analytical laboratories, HyperDSC represents a technological advancement that addresses specific sensitivity challenges. Understanding the core principles, complementary strengths, and specific applications of each method enables scientists to select the optimal analytical strategy for their material characterization challenges. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data, to inform method selection within the broader context of polymer characterization research.

Core Principles and Measurement Focus

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in what they measure. DSC focuses on energy changes, TGA on mass changes, and HyperDSC on enhancing the sensitivity and speed of DSC measurements.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measures the heat flow into or out of a sample as it is heated, cooled, or held at a constant temperature. By comparing this heat flow to an inert reference, it detects endothermic (heat-absorbing) and exothermic (heat-releasing) transitions. Its primary applications include determining melting points, crystallization behavior, glass transition temperatures (Tg), and curing reactions [31] [30]. Modern DSC instruments are highly sensitive, capable of detecting heat changes as small as 0.1 microWatts [31].

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA, in contrast, is a balance within a furnace that monitors a sample's mass change as a function of temperature or time. It is the definitive technique for assessing thermal stability, decomposition profiles, moisture content, and filler composition. TGA can detect mass losses as low as 0.1 micrograms, providing quantitative data on a material's composition [31] [32].

HyperDSC

HyperDSC is a specialized DSC technique that employs very fast scanning rates, typically in the range of 400 to 500 °C/min [33] [34]. This rapid heating substantially enhances the sensitivity of the measurement, allowing for the detection of very weak transitions that might be missed by conventional DSC. It is particularly valuable for analyzing small sample sizes, materials that recrystallize during melting, or for high-throughput screening applications [33] [34].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Feature | DSC | TGA | HyperDSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measurement | Heat Flow (mW) | Mass Change (mg) | Heat Flow at High Scan Rates |

| Key Applications | Melting, crystallization, glass transition, curing | Thermal stability, composition, moisture content | High-sensitivity Tg detection, fast screening |

| Typical Sample Size | 1–10 mg [32] [30] | 5–30 mg [32] | 1–10 mg (similar to DSC) |

| Key Question Answered | "When does the material melt, and how much energy is required?" [35] | "At what temperature does the material break down?" [35] | "What weak transitions are undetectable by standard DSC?" |

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

The choice between DSC, TGA, and HyperDSC is often dictated by the specific analytical question. The following comparative data and experimental protocols highlight their distinct performance characteristics.

Detection Capabilities for Material Properties

Different thermal properties are best probed by specific techniques. The table below summarizes the ideal applications for each method, demonstrating their complementary roles in a complete material characterization workflow [11].

Table 2: Property Detection Capabilities of Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Property | DSC | TGA | HyperDSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition (Tg) | x | x (Enhanced) | |

| Melting & Crystallinity | x | x | |

| Enthalpy Changes | x | x | |

| Specific Heat Capacity | x | ||

| Purity | x | (x) | |

| Polymorphism | x | x | |

| Thermal Stability | (x) | x | |

| Composition & Fillers | x | ||

| Moisture & Volatiles | x | ||

| Decomposition | (x) | x | |

| Oxidative Stability | x | x |

Legend: x = Ideal Technique, (x) = Can Be Used But Not Optimal

HyperDSC vs. Modulated DSC: Experimental Sensitivity Comparison

A direct comparison between HyperDSC and Modulated DSC (MDSC) demonstrates the former's superior sensitivity for detecting weak glass transitions.

- Experimental Protocol: The glass transition of Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) at various moisture contents was measured using both MDSC and HyperDSC. Subsequently, the Tg of PVP was measured in a series of powder mixtures with lactose, where PVP concentrations ranged from 5 to 50% w/w [33].

- Results and Data: The Tg temperatures measured by both techniques were consistent and aligned with theoretical values. However, the magnitude of the Tg signal was significantly larger in HyperDSC. In the mixture study, MDSC could only detect the Tg of PVP at concentrations of 40% w/w and above. In contrast, HyperDSC easily detected the Tg in all samples, including those with only 5% w/w PVP [33].

- Conclusion: HyperDSC provides a substantial increase in sensitivity, enabling the detection of amorphous phases in predominantly crystalline systems where other DSC techniques fail.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

General DSC Protocol for Polymer Characterization

A standard experimental workflow for determining a polymer's glass transition and melting point is as follows [31] [36]:

- Sample Preparation: A small sample (1-10 mg) is accurately weighed and placed in a sealed crucible. An empty, identical crucible serves as the reference.

- Instrument Calibration: The temperature and enthalpy scales are calibrated using high-purity standards like indium.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Atmosphere: Inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen) at 50 mL/min flow rate.

- Scan Rate: A moderate rate of 10°C/min is typical for standard DSC.

- Temperature Range: For most polymers, a range from -50°C to 300°C is sufficient.

- Data Analysis: The resulting thermogram is analyzed for the glass transition (a step-change in heat flow), and melting/crystallization events (peaks). The Tg is typically taken as the midpoint of the transition.

HyperDSC Protocol for Enhanced Sensitivity

The protocol for HyperDSC differs primarily in the scan rate [33] [34]:

- Sample Preparation: As above.

- Instrument Calibration: Requires calibration at the intended fast scan rate.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Atmosphere: Inert gas, often at a higher flow rate.

- Scan Rate: Very fast, e.g., 200–500 °C/min.

- Temperature Range: Set to encompass the transition of interest.

- Data Analysis: The enhanced signal-to-noise ratio makes weak transitions more visible. However, the high scan rate can slightly shift transition temperatures, which must be considered during interpretation.

TGA Protocol for Compositional Analysis

A typical TGA method to analyze a polymer composite might be [32] [30]:

- Sample Preparation: 5-20 mg of sample is placed in an open crucible.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Atmosphere: Often starts with an inert gas (Nâ‚‚) to observe decomposition, then switches to air or oxygen to burn off carbonaceous residue.

- Scan Rate: 10–20°C/min from room temperature to 800–1000°C.

- Data Analysis: The mass loss steps are quantified. The first step (up to ~150°C) often corresponds to moisture loss, the main step to polymer decomposition, and the final residue represents inert filler or ash content.

Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for researchers selecting a thermal analysis technique based on their primary analytical question.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful thermal analysis experiment relies on more than just the instrument. The following table details key materials and consumables used in these techniques.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermal Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Calibration Standards | To calibrate temperature and enthalpy response of the instrument. | Metals like Indium (melting point 156.6°C) are essential for DSC/HyperDSC calibration [31]. |

| Hermetic Sealed Crucibles | To contain the sample and withstand internal pressure during heating. | Crucial for preventing solvent evaporation in DSC and for studying volatile samples [36]. |

| Inert Gas Supply | To provide an oxygen-free environment and prevent unwanted oxidation. | High-purity Nitrogen or Argon is standard for DSC and TGA [32] [30]. |

| Reference Materials | To provide an inert baseline for differential measurements. | For DSC, an empty pan or one filled with alumina is standard [31] [36]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | For cleaning sample crucibles and instruments between runs. | Prevents cross-contamination and ensures baseline stability. |

DSC, TGA, and HyperDSC are powerful, complementary tools in the polymer and pharmaceutical scientist's arsenal. DSC excels at characterizing energy-driven phase transitions, TGA is unmatched for quantifying thermal stability and composition, and HyperDSC breaks sensitivity barriers for detecting subtle transitions and enabling high-throughput analysis.

The most effective characterization strategy often involves using these techniques in concert. For instance, TGA can first identify key decomposition temperatures, while DSC can then be used to study melting and glass transitions well below those decomposition points. When standard DSC fails to detect a weak glass transition in a complex formulation, HyperDSC provides the necessary sensitivity. By understanding their distinct principles and applications, researchers can make informed decisions to efficiently solve complex material characterization problems, ultimately driving innovation in drug development and polymer science.

Spectroscopic and Microscopic Techniques (FTIR, NMR, SEM, TEM) for Structural Elucidation

Structural elucidation lies at the heart of advancements in materials science, chemistry, and biology. Understanding the intricate relationship between a material's structure and its properties is fundamental to designing new polymers, developing pharmaceuticals, and creating advanced nanomaterials. Among the most critical techniques for this purpose are Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). These tools form the backbone of analytical characterization, enabling researchers to probe materials from the macroscopic level down to atomic resolution. FTIR and NMR provide deep insights into chemical composition, functional groups, and molecular dynamics, while SEM and TEM offer unparalleled visualization of morphological features, surface topography, and internal structures. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these four pivotal techniques, presenting their fundamental principles, comparative capabilities, experimental protocols, and practical applications to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal characterization strategy for their specific research needs.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Each technique operates on distinct physical principles, yielding complementary information about a sample's characteristics. The following table provides a structured comparison of their core attributes, typical applications, and key strengths.

Table 1: Core Attributes and Applications of Key Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Primary Information Obtained | Best For | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR [37] | Absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds, causing vibrations. | Functional groups, chemical bonding, molecular identity (molecular fingerprint). | Identifying organic compounds, polymers, and coatings; studying surface reactions. | Rapid analysis; minimal sample prep; versatile sampling modes (ATR, transmission). |

| NMR [38] | Interaction of atomic nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C) with a magnetic field and radiofrequency pulses. | Molecular structure, dynamics, composition, and quantitative concentration. | Determining 3D molecular structure in solution; studying protein folding and interactions. | Provides atomic-level detail; non-destructive; quantitative. |

| SEM [39] [40] | Scattering of a focused electron beam from a sample's surface, detecting secondary/backscattered electrons. | Surface topography, morphology, and qualitative elemental composition (with EDS). | Visualizing surface features, fractures, and particle morphology at high depth of field. | High depth of field; straightforward sample prep (for conductive samples). |

| TEM [41] [39] [40] | Transmission of a high-energy electron beam through an ultra-thin sample. | Internal structure, crystallography, nanoparticle size/shape, and atomic-scale defects. | Analyzing internal nanostructure, lattice fringes, and defects in thin films or nanoparticles. | Highest magnification (atomic resolution); detailed crystallographic information. |

A critical differentiator among these techniques is their spatial resolution and the type of information they yield. The following diagram illustrates the characteristic resolution and primary data type for each method, highlighting their respective domains of expertise.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Requirements

Proper sample preparation is paramount for obtaining reliable and high-quality data. The requirements vary significantly across the techniques, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Sample Preparation Protocols for Different Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Sample State | Key Preparation Steps | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR [37] | Solid, liquid, or gas. | For transmission: KBr pellet or thin film. For ATR: direct contact with crystal. | Samples must be IR-active; water interference must be minimized. |

| NMR [38] | Typically liquid (dissolved in deuterated solvent). | Dissolution in a deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) in a specialized NMR tube. | Sample must be soluble; high purity is required for accurate interpretation. |

| SEM [39] [40] | Solid, dry. | Mounting on a stub, followed by coating with a conductive material (e.g., gold, palladium). | Electrical conductivity is essential to prevent charging; vacuum-compatible. |

| TEM [39] [40] | Solid, ultra-thin (≤ 150 nm). | Ultrathin sectioning via microtomy; staining with heavy metals (e.g., uranyl acetate) for contrast. | Sample must be electron-transparent; preparation is complex and can induce artifacts. |

Data Interpretation Workflow

The journey from raw data to meaningful structural insights follows a systematic workflow. The diagram below outlines the general process for interpreting results from these analytical techniques.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful characterization relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogs essential items for experiments utilizing these techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Characterization Experiments

| Category | Item | Primary Function | Typical Application/Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d6) | Dissolves samples for analysis without adding interfering signals. | NMR Spectroscopy [38] |

| Conductive Coating Materials (Gold, Palladium) | Creates a thin conductive layer on non-conductive samples to prevent charging. | SEM Imaging [40] | |

| Heavy Metal Stains (e.g., Uranyl Acetate) | Enhances contrast by scattering electrons more efficiently. | TEM Imaging [40] | |

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | Forms transparent pellets for analyzing solid samples in transmission mode. | FTIR Spectroscopy [37] | |

| Calibration & Reference | Silicon Wafer | A standard sample for verifying SEM instrument performance and focus. | SEM Imaging |

| Graphite | Used for calibration and alignment of the TEM electron beam. | TEM Imaging | |

| Chemical Shift Standards (e.g., TMS) | Provides a reference point (0 ppm) for chemical shifts in NMR spectra. | NMR Spectroscopy [38] | |

| Consumables | NMR Tubes | Specialized, high-precision glass tubes designed for NMR spectrometers. | NMR Spectroscopy [38] |

| SEM Stubs | Metal mounts for securing samples within the SEM vacuum chamber. | SEM Imaging [40] | |

| TEM Grids (e.g., Copper, Nickel) | Thin, mesh-like supports that hold the sample within the TEM column. | TEM Imaging [40] |

FTIR, NMR, SEM, and TEM are powerful, complementary techniques that form the cornerstone of modern structural elucidation. FTIR excels in rapid functional group identification, NMR provides unparalleled detail on molecular structure and dynamics, SEM reveals surface morphology with great depth of field, and TEM offers the highest resolution for probing internal nanostructure. The choice of technique is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the specific research question at hand. Often, a multi-technique approach—correlating chemical identity from FTIR/NMR with morphological data from SEM/TEM—yields the most comprehensive understanding of a material's properties. As instrumentation advances, the integration of these tools, combined with automated data processing and artificial intelligence, promises to further unlock the mysteries of material structure and accelerate innovation across scientific disciplines.

The real-time monitoring of polymer and protein degradation under stress is a critical frontier in materials science and biotechnology. Understanding these dynamic processes provides invaluable insights for drug development, the creation of high-performance materials, and the preservation of cultural heritage. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern techniques enabling researchers to capture these complex events as they happen. We focus on methodologies that have moved beyond traditional endpoint analysis to offer live, data-rich feedback on degradation pathways. The subsequent sections will dissect experimental protocols, present comparative performance data, and detail the essential toolkit required to implement these advanced characterization strategies in a research setting.

Real-Time Monitoring Techniques for Polymers

Computer Vision for Frontal Polymerization

A transformative approach for monitoring thermoset polymer curing in real-time involves integrating computer vision with direct ink writing (DIW) 3D printing. This system tracks the propagation of the polymerization front—the exothermic reaction zone that transforms monomer ink into a solid thermoset. The core innovation uses a high-resolution camera (200 Hz frame rate) and a thermochromic leuco dye added to the resin formulation. This dye changes color from black to vibrant pink at a specific temperature threshold (e.g., 35°C), creating a high-contrast visual marker for the polymerization front without affecting the material's thermomechanical properties [42].

The real-time image processing workflow is automated via a Python script. The process involves edge detection to convert video frames into binary images, followed by a linear front detection algorithm within a defined region of interest. The system calculates the front velocity by tracking the front's movement relative to a fixed reference point and automatically adjusts the printer's nozzle velocity and extrusion rate to match, ensuring consistent print geometry and cure quality [42]. This method has been validated for printing freestanding structures like mechanical springs with different resin formulations, achieving consistent results despite variations in front velocity [42].

IoT Integration for In-Service Composite Monitoring

For polymer composites already in use, Internet of Things (IoT) integration enables real-time monitoring of degradation due to environmental and mechanical stress. Sensors embedded within the composite material continuously track parameters like stress, strain, temperature, and humidity [43].

The data from these sensors is transmitted wirelessly to cloud platforms for analysis. This allows for predictive maintenance and performance optimization. The synergy of IoT with machine learning (ML) is particularly powerful; ML algorithms analyze the vast datasets to identify patterns, predict long-term behavior, and flag early signs of material failure that might be missed by manual inspection [43]. This approach is gaining traction in demanding industries such as aerospace and automotive, where understanding real-time material degradation is crucial for safety and reliability [43].

Table 1: Comparison of Real-Time Polymer Monitoring Techniques.

| Monitoring Technique | Measured Parameters | Key Components | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computer Vision & DIW [42] | Polymerization front velocity, temperature, geometry | High-speed camera, thermochromic dye, Python algorithm for edge detection | In-situ curing of thermosets in 3D printing | Rapid (200 Hz), non-contact, enables automated process control, material-agnostic |