Polymer Melt Flow Fundamentals: Understanding Viscoelastic Behavior and Defect Formation in Pharmaceutical Processing

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymer melt flow behavior, linking fundamental rheological principles to practical defect formation in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes like hot-melt extrusion and injection molding.

Polymer Melt Flow Fundamentals: Understanding Viscoelastic Behavior and Defect Formation in Pharmaceutical Processing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymer melt flow behavior, linking fundamental rheological principles to practical defect formation in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes like hot-melt extrusion and injection molding. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the viscoelastic nature of polymer melts, details advanced characterization methodologies, presents systematic troubleshooting for common processing defects, and evaluates computational models against experimental validation. The content synthesizes foundational science with applied strategies for optimizing product quality and process robustness in polymeric drug delivery system development.

The Viscoelastic Nature of Polymer Melts: From Chain Dynamics to Flow Instabilities

Within the broader thesis on Basic principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation research, polymer melt rheology serves as the fundamental discipline connecting the molecular architecture of polymers to their macroscopic processing behavior and the ultimate quality of finished products. This guide details the core principles, experimental techniques, and quantitative relationships that define this critical bridge, with a focus on implications for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in polymeric drug delivery systems, device manufacturing, and formulation science.

Molecular Parameters Influencing Melt Rheology

The flow behavior of a polymer melt is governed by its molecular structure. Key parameters are summarized below.

Table 1: Molecular Parameters and Their Rheological Influence

| Molecular Parameter | Definition | Primary Rheological Impact | Typical Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (Mw) | Average mass of polymer chains. | Directly affects zero-shear viscosity (η₀ ∝ Mw^3.4 above critical Mw). | Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) |

| Molecular Weight Distribution (Đ = Mw/Mn) | Polydispersity index. | Broad Đ increases shear-thinning, alters elasticity, impacts melt strength. | Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) |

| Chain Architecture | Linear, long-chain branched (LCB), star, comb. | LCB enhances melt strength, elasticity, and elongational viscosity; modifies shear-thinning. | Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) |

| Chain Entanglement Density | Number of topological constraints per chain. | Determines plateau modulus (G_N^0), affects relaxation spectrum. | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) / Rheology |

| Thermodynamic State (T - Tg) | Distance from glass transition temperature. | Governs segmental mobility; viscosity follows Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation. | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) |

Core Rheological Properties and Measurements

Fundamental Properties

- Shear Viscosity (η): Resistance to steady shearing flow. Exhibits Newtonian plateau at low shear rates and shear-thinning at high rates.

- Elastic Moduli (G', G''): Storage modulus (G') measures elastic energy storage; loss modulus (G'') measures viscous energy dissipation. Obtained from oscillatory shear tests.

- Relaxation Spectrum: Characterizes the time-dependent relaxation of polymer chains after deformation.

- Elongational Viscosity (η_E): Resistance to extensional flow, critical for processes like film blowing and fiber spinning.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) for Linear Viscoelasticity

- Objective: To characterize the linear viscoelastic (LVE) properties without disrupting the microstructure.

- Apparatus: Strain-controlled or stress-controlled rotational rheometer with parallel plate or cone-and-plate geometry.

- Procedure:

- Load a polymer melt sample onto the pre-heated rheometer platen (typical gap: 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Conduct a strain (or stress) sweep at a fixed frequency (e.g., 1 Hz) to determine the LVE region where moduli are independent of strain amplitude.

- Perform a frequency sweep (e.g., 0.01 to 100 rad/s) within the LVE region at a constant temperature (isothermal).

- Apply time-temperature superposition (TTS) using master curves if applicable, shifting data from multiple temperatures to a reference temperature (T_ref).

- Key Outputs: G'(ω), G''(ω), complex viscosity η*(ω), master curves, plateau modulus (G_N^0), crossover frequency (related to average relaxation time).

Protocol 2: Capillary Rheometry for High-Shear Viscosity

- Objective: To measure apparent shear viscosity under high shear rates relevant to processing (e.g., extrusion, injection molding).

- Apparatus: Capillary rheometer with a reservoir, piston, and a die of known length (L) and diameter (D).

- Procedure:

- Pre-heat the barrel and die to the target temperature.

- Load polymer pellets or pre-formed plugs into the barrel.

- Drive the piston at a constant speed to extrude the melt through the capillary die.

- Record pressure drop (ΔP) across the die and the volumetric flow rate (Q).

- Repeat for multiple piston speeds.

- Apply Bagley correction (for entrance pressure loss) using dies of different L/D ratios and Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch correction (for non-parabolic velocity profile in non-Newtonian fluids).

- Key Outputs: Apparent shear rate (γ̇app), true shear stress (τw), true shear rate (γ̇_w), and true viscosity (η) as a function of shear rate.

Protocol 3: Uniaxial Extensional Rheometry

- Objective: To measure transient and steady elongational viscosity.

- Apparatus: Sentmanat Extensional Rheometer (SER) fixture on a rotational rheometer or dedicated extensional rheometer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a rectangular polymer sample.

- Mount the sample ends onto two rotating drums held at a constant temperature.

- Initiate test by rotating drums in opposite directions, imposing a constant Hencky strain rate (ε̇).

- Measure the force (F(t)) required to maintain this extension and the sample dimensions.

- Calculate transient extensional viscosity: ηE+(t) = σE(t) / ε̇, where σ_E is the tensile stress.

- Key Outputs: Transient elongational viscosity growth curve, strain-hardening ratio.

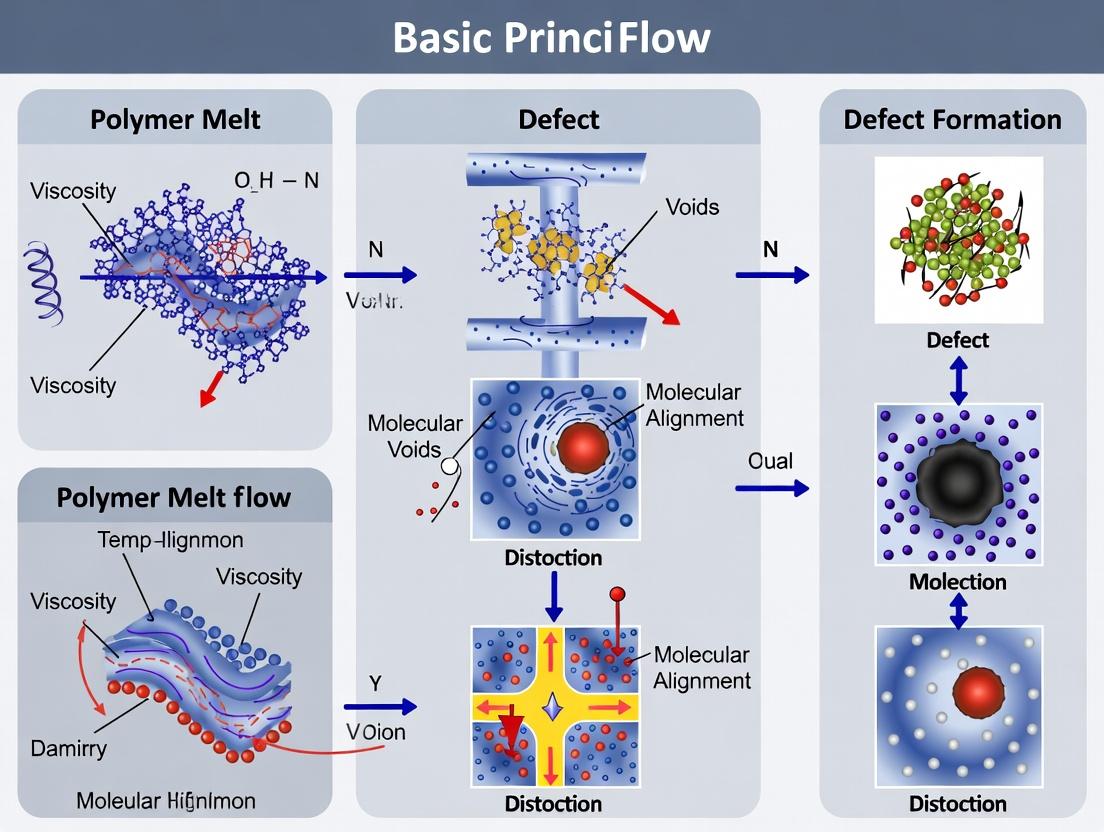

Linking Rheology to Processing and Defect Formation

Flow instabilities and defects in final products originate from specific rheological responses.

Table 2: Rheological Origins of Common Processing Defects

| Defect | Typical Process | Primary Rheological Cause | Molecular/Structural Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melt Fracture (Sharkskin) | Extrusion, Blow Molding | High wall shear stress (> critical τ_c) causing slip-stick instability. | High molecular weight, narrow MWD, low chain entanglement slippage. |

| Gross Melt Fracture | Extrusion | Cohesive failure due to excessive elastic energy storage and recoil at the die entrance. | High melt elasticity (G'), long relaxation times, presence of long-chain branching. |

| Die Swell (Extrudate Swell) | Extrusion, Injection Molding | Recovery of elastic (reversible) deformation upon exiting the confinement of a die. | High first normal stress difference (N₁), long relaxation times, increased LCB. |

| Draw Resonance | Fiber Spinning, Film Casting | Instability in elongational flow leading to periodic thickness variation. | Inadequate strain hardening in extensional viscosity, specific molecular weight distribution. |

| Bubbles/Voids | Injection Molding, Hot-Melt Extrusion | Trapped volatiles or decompression; related to elongational and shear viscosity. | Low melt strength, inappropriate viscosity at processing temperature. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Melt Rheology Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Standards | Calibrate molecular weight (MW) and dispersity (Đ) via GPC. Provide reference materials for rheological models. | NIST-traceable linear polystyrene or polyethylene standards are common. |

| Thermal Stabilizers | Prevent oxidative degradation during high-temperature rheological testing. | E.g., Irganox 1010; added at low concentrations (0.1-0.5 wt%). |

| Rheometer Calibration Fluids | Verify torque, normal force, and displacement transducers on rotational rheometers. | Newtonian silicone oils of certified viscosity across a temperature range. |

| Release Agents | Ensure clean sample ejection from molds and rheometer fixtures, preventing sample tearing. | Non-silicone, non-transferring sprays (e.g., based on fluorocarbons) for high-temp use. |

| Geometry-Specific Tools | For sample loading and trimming (e.g., parallel plate trimmer, capillary die cleaners). | Maintain precise sample geometry, crucial for data accuracy. |

| Inert Gas Supply (N₂ or Ar) | Creates an inert atmosphere in the rheometer environmental chamber during testing. | Essential for testing polyolefins and other degradation-sensitive polymers at high temperatures. |

Advanced Constitutive Modeling

To quantitatively bridge molecular structure and flow, advanced constitutive models are employed. These integrate molecular parameters into continuum-level stress predictions.

- Generalized Newtonian Fluid (GNF): Models viscosity as a function of shear rate (e.g., Power Law, Carreau-Yasuda models). Does not capture elasticity.

- Linear Viscoelastic Models: Maxwell and Kelvin-Voigt models describe small-deformation behavior using relaxation spectra.

- Non-Linear Differential Models: Giesekus, Phan-Thien-Tanner (PTT) models introduce parameters related to molecular orientation and stretch, providing predictions for both shear and extensional flows.

- Molecular-Inspired Models: The Pom-Pom model and its derivatives explicitly account for polymer backbone stretch and branch point withdrawal, making them powerful for modeling long-chain branched polymers.

The selection of an appropriate model, parameterized with accurate experimental data from the protocols outlined, enables the simulation and prediction of complex processing flows and the anticipation of defect formation windows, closing the loop from molecular design to robust manufacturing.

Abstract This technical guide details four key viscoelastic phenomena governing polymer melt flow, framed within a thesis on fundamental flow behavior and its causal link to processing defects. Understanding these phenomena is critical for researchers in material science and pharmaceutical development, where precise control over product morphology (e.g., in film coating, fiber spinning, or tablet extrusion) is paramount. The interplay between viscous dissipation and elastic energy storage dictates final product dimensions, surface quality, and structural integrity.

Polymer melts are non-Newtonian, viscoelastic fluids. Their flow behavior cannot be described by viscosity alone but requires an understanding of time-dependent elastic responses. These responses arise from the entanglement and relaxation of long-chain molecules under deformation. The four phenomena under discussion—Shear Thinning, Elastic Recovery, Die Swell, and Normal Stresses—are macroscopic manifestations of this molecular architecture and govern defect formation such as melt fracture, sharkskin, and dimensional instability.

Shear Thinning (Pseudoplasticity)

Shear thinning describes the decrease in apparent viscosity with increasing shear rate, a critical factor for energy-efficient processing.

Molecular Mechanism: At rest, polymer chains are highly entangled, leading to high zero-shear viscosity (η₀). Under shear, chains align and disentangle in the flow direction, reducing resistance to flow.

Quantitative Modeling: The power-law (Ostwald-de Waele) model is commonly used: τ = K * (γ̇)^n where τ is shear stress, K is the consistency index, γ̇ is shear rate, and n is the power-law index (n < 1 for shear thinning).

Table 1: Power-Law Parameters for Common Polymer Melts

| Polymer | Temperature (°C) | K (Pa·sⁿ) | n | Applicable Shear Rate Range (s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | 180 | 1.2e4 | 0.40 | 10¹ - 10⁴ |

| HDPE | 200 | 7.5e3 | 0.55 | 10¹ - 10³ |

| Polypropylene | 230 | 8.0e3 | 0.45 | 10¹ - 10⁴ |

| Polystyrene | 200 | 2.5e4 | 0.30 | 10¹ - 10³ |

Experimental Protocol: Capillary Rheometry

- Setup: Load polymer pellets into the barrel of a capillary rheometer. Equip with a die of specific length (L) and diameter (D). Set precise temperature control.

- Conditioning: Allow thermal equilibrium for 10-15 minutes.

- Shearing: Use a piston to extrude the melt at a series of controlled piston speeds (v).

- Data Collection: Record pressure drop (ΔP) across the die and volumetric flow rate (Q).

- Calculation: Calculate apparent shear rate (32Q/(πD³)) and wall shear stress (ΔP*D/(4L)). Correct for entrance effects (Bagley correction) and non-parabolic velocity profile (Rabinowitsch correction).

- Analysis: Plot log(τ) vs. log(γ̇) to determine K and n.

Elastic Recovery and Die Swell (Extrudate Swell)

Elastic recovery is the partial reversal of deformation upon stress removal. Die swell is its most observable consequence, where the extrudate diameter exceeds the die diameter.

Molecular Mechanism: Deformation stores elastic energy in stretched polymer chains. Upon exiting the die (stress removal), this stored energy drives chain relaxation and recoil, causing radial expansion.

Key Factors: Die swell ratio (B = Dextrudate / Ddie) increases with:

- Increasing shear rate (γ̇).

- Decreasing temperature.

- Increasing molecular weight and polydispersity.

- Longer die length (up to a plateau, as some stress relaxes within the die).

Table 2: Typical Die Swell Ratios Under Processing Conditions

| Polymer | Die L/D Ratio | Shear Rate (s⁻¹) | Temperature (°C) | Typical Swell Ratio (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | 10 | 100 | 180 | 1.6 - 1.9 |

| HDPE | 20 | 100 | 200 | 1.4 - 1.6 |

| PDMS (Silicone) | 10 | 50 | 25 | 1.1 - 1.3 |

Experimental Protocol: Extrudate Swell Measurement

- Extrusion: Use a capillary rheometer with a flat-entry die.

- Collection: Extrude a strand at constant shear rate onto a moving belt or into a temperature-controlled oil bath to freeze the morphology.

- Measurement: After complete cooling, use a laser micrometer or precision calipers to measure the extrudate diameter at multiple points.

- Analysis: Calculate the average swell ratio (B). Correlate with shear stress and capillary L/D ratio.

Diagram Title: Mechanism of Polymer Die Swell

Normal Stress Differences

In viscoelastic flows, shear induces unequal normal stresses perpendicular to the flow direction. The first (N₁) and second (N₂) normal stress differences are defined as: N₁ = τ₁₁ - τ₂₂, N₂ = τ₂₂ - τ₃₃ where direction 1 is flow, 2 is velocity gradient, and 3 is neutral. N₁ is typically large and positive, driving many viscoelastic effects.

Manifestations: N₁ is responsible for rod-climbing (Weissenberg effect), curved free surfaces, and secondary flows in non-circular channels.

Experimental Protocol: Cone-and-Plate Rheometry for N₁

- Setup: Place a small sample between a flat plate and a low-angle cone (< 5°) on a rotational rheometer. Ensure gap truncation is correct.

- Temperature: Equilibrate at test temperature.

- Steady Shear: Apply a constant rotational speed (Ω) to achieve desired shear rate (γ̇ = Ω/θ, where θ is cone angle).

- Measurement: The rheometer measures the total normal force (Fz) on the plate. For a cone-and-plate geometry, the first normal stress difference is calculated as: N₁ = 2 * Fz / (π * R²), where R is the plate radius.

- Shear Rate Sweep: Repeat across a range of shear rates to build function N₁(γ̇).

Table 3: First Normal Stress Difference (N₁) Data

| Polymer | Shear Rate (s⁻¹) | Temperature (°C) | N₁ (kPa) | N₁ / Shear Stress Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene | 0.1 | 200 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Polystyrene | 1.0 | 200 | 8.0 | 2.5 |

| Polyisobutylene | 1.0 | 50 | 12.0 | 3.0 |

Link to Processing Defects

- Melt Fracture/Sharkskin: Caused by excessive shear stress at the die wall combined with elastic recovery, leading to surface or gross distortion. Correlates with a critical wall shear stress and N₁.

- Draw Resonance: In fiber spinning, caused by unstable interaction between viscous draw-down, elastic recovery, and cooling.

- Poor Dimensional Tolerance: Directly linked to uncontrolled and non-uniform die swell.

Diagram Title: Flow-Induced Defect Formation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Experimental Materials for Polymer Melt Rheology

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| Capillary Rheometer | Emulates processing conditions (high shear). Measures shear viscosity, die swell, and detects flow instabilities via pressure oscillations. |

| Rotational Rheometer (with cone-and-plate/parallel plate fixtures) | Precisely measures linear/non-linear viscoelastic properties, including N₁ in steady shear and dynamic moduli (G', G'') in oscillatory tests. |

| Strain-Controlled Elongational Rheometer (e.g., SER fixture) | Characterizes extensional viscosity and strain-hardening, critical for understanding processes like film blowing and fiber spinning. |

| Standard Reference Fluids (e.g., NIST Polyethylene, PDMS) | Calibrate equipment and validate experimental protocols. Ensure data reproducibility across labs. |

| High-Temperature Thermal Oxidative Stabilizer (e.g., Irganox, Ultranox) | Added to polymer samples to prevent degradation during prolonged testing at high temperatures, ensuring property measurement reflects intrinsic behavior. |

| Laser Micrometer / High-Speed Camera | Accurately measure transient die swell and extrudate dimensions or visualize surface defect formation in real-time. |

| Precision-Machined Dies (varying L/D, entrance angles) | Study the effects of die geometry on shear history, pressure drop, and the onset of elastic-driven defects. |

Within the study of Basic principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation, understanding the role of Molecular Weight (MW) and Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) is paramount. These parameters are the fundamental architectural variables dictating the viscoelastic response of a polymer melt during processing. They directly govern chain entanglement density, relaxation dynamics, and ultimately, the manifestation of flow-related defects in final products, a critical concern for researchers in material science and drug development formulating polymeric delivery systems.

Core Principles: MW & MWD Governing Rheology

Molecular Weight (MW)

The average size of polymer chains. Key averages include:

- Number-Average Molecular Weight (Mₙ): Sensitive to the total number of molecules.

- Weight-Average Molecular Weight (Mw): Sensitive to the weight fraction of larger molecules. The ratio Mw/Mₙ defines the polydispersity index (PDI).

Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD)

The statistical spread of chain lengths within a sample. A broad MWD indicates a wide range of chain lengths, while a narrow MWD indicates more uniform chains.

Governing Melt Viscosity (η₀)

The zero-shear viscosity (η₀) exhibits a distinct dependence on Mw, characterized by a critical molecular weight (Mc) for entanglement.

- Below Mc: η₀ ∝ Mw¹.0

- Above Mc: η₀ ∝ Mw^(3.4-3.6) for most linear polymers.

MWD influences the shear-thinning behavior: broader distributions show earlier onset and more gradual shear thinning.

Governing Melt Elasticity

Elastic effects (die swell, melt fracture, recoil) are primarily governed by the longest chains in the distribution. These chains have longer relaxation times (τmax ∝ Mw^3.4) and store elastic energy under deformation. A broader MWD, with a "tail" of very high MW chains, disproportionately increases elasticity and can exacerbate processing defects.

Table 1: Effect of M_w and MWD on Key Melt Properties

| Polymer Property | Primary Governor | Functional Relationship | Typical Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) | Weight-Avg MW (M_w) | η₀ ∝ Mw^(3.4) for Mw > M_c | Capillary or Rotational Rheometry |

| Shear-Thinning Onset | MWD Breadth (PDI) | Broader MWD → lower critical shear rate | Steady Shear Rheometry |

| Primary Normal Stress Difference (N₁) | High-MW Tail of MWD | N₁ ∝ (Mz / Mw)^α | Cone-and-Plate Rheometry |

| Relaxation Time Spectrum | M_w and full MWD | τmax ∝ Mw^3.4; MWD broadens spectrum | Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) |

| Melt Fracture Critical Shear Rate | High-MW Tail (M_z) | Broad MWD lowers critical shear rate for instability | Capillary Rheometry with visual/die pressure analysis |

Table 2: Common Polymer Characterization Techniques for MW & MWD

| Technique | Measures | Information Obtained | Applicable MW Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) | Mn, Mw, M_z, PDI | Full MWD curve relative to standards | ~500 - 10⁷ Da |

| Melt Flow Index (MFI) | Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) | Single-point flow index inversely related to M_w | Empirical, process-related |

| Intrinsic Viscosity [η] | Viscosity-average Mw (Mv) | Polymer-solvent interaction & chain size | ~10³ - 10⁷ Da |

| Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) | Absolute M_w, Radius of Gyration | Absolute MW without standards, size info | ~10³ - 10⁸ Da |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining MW-Melt Viscosity Relationship via Capillary Rheometry

Objective: To establish the power-law relationship between M_w and zero-shear viscosity (η₀). Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain or synthesize a series of linear polymer homologs (e.g., polystyrene) with varying, well-characterized M_w but narrow and similar MWDs (PDI < 1.2). Dry samples thoroughly.

- Rheometry: Load sample into barrel of capillary rheometer pre-heated to test temperature (e.g., 200°C). Allow thermal equilibrium (5-10 min).

- Shear Rate Sweep: Apply a series of controlled piston speeds to extrude melt through a long capillary die (L/D ≥ 30). Record pressure drop (ΔP) across the die and volumetric flow rate (Q) at each speed.

- Data Analysis (Bagley & Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch Corrections):

- Bagley Correction: Perform runs with at least two dies of identical diameter but different lengths. Plot pressure drop vs. L/D at constant shear rate; extrapolate to zero length to correct for entrance pressure losses.

- Shear Stress: Calculate true wall shear stress (τw) from corrected ΔP.

- Shear Rate Correction: Correct the apparent shear rate (4Q/πR³) for the non-parabolic velocity profile of a non-Newtonian fluid using the Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch equation.

- Viscosity: Compute true viscosity (η) = τw / (corrected shear rate).

- Zero-Shear Determination: Plot η vs. corrected shear rate on a log-log scale. Identify the plateau region at low shear rates; the plateau value is η₀.

- Correlation: Plot log(η₀) vs. log(Mw) for the sample series. Fit data; the slope below Mc is ~1.0, and above M_c is ~3.4-3.6.

Protocol: Assessing MWD Impact on Elasticity via Die Swell Measurement

Objective: To correlate the high-MW tail of the distribution with elastic recovery (die swell). Materials: Polymer samples with similar Mw but varying Mw (different PDI). Capillary rheometer equipped with a short die (L/D ≈ 0). Procedure:

- Characterization: Precisely determine the full MWD (Mn, Mw, M_z) for each sample using GPC-MALS.

- Extrusion: Under identical temperature and a constant, low shear rate (to minimize viscous heating), extrude each polymer through a short capillary die.

- Measurement: Allow the extrudate to cool and solidify. Precisely measure the diameter of the extrudate (D_extrudate) at multiple points.

- Calculation: Calculate the die swell ratio, B = Dextrudate / Ddie.

- Correlation: Plot B against Mz (the z-average MW, sensitive to the high-MW tail) and against PDI (Mw/Mn). Typically, B shows a stronger correlation with Mz, demonstrating the disproportionate effect of the longest chains on elasticity.

Visualization Diagrams

Title: How MW and MWD Govern Flow and Defects

Title: Experimental Flow for MW-Viscosity Law

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Key Consideration for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow MWD Polymer Standards | Calibrate GPC/SEC; create model systems to isolate MW effects from MWD effects. | Must match polymer chemistry (e.g., PS, PEG, PMMA). PDI < 1.1 is ideal. |

| High-Temperature GPC/SEC Columns | Separate polymer chains by hydrodynamic volume in solvents like THF or DMF at elevated temps (e.g., for polyolefins). | Column pore size must match target MW range. Requires high-boiling, stable solvents. |

| Capillary Rheometer with Dual-Die Set | Enables accurate Bagley correction for true shear stress by using dies of same diameter, different lengths. | Dies must be precisely machined. Long L/D (e.g., 30:1) minimizes correction magnitude. |

| Cone-and-Plate Rheometer | Measures linear viscoelastic properties (G', G'') and N₁ under homogeneous shear, ideal for melt elasticity studies. | Gap setting is critical; cone angle must be small (<4°). Requires precise temperature control. |

| Melt Flow Indexer | Provides a quick, single-point MFR value per ASTM D1238. Correlates roughly with M_w for quality control. | Not a fundamental measurement; highly sensitive to test conditions (temp, load). |

| Thermal Stabilizers/Antioxidants | Prevent oxidative degradation of polymer melts during prolonged rheological testing at high temperatures. | Must be compatible and not plasticize the polymer. Common: Irganox, BHT. |

| High-Purity, Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., THF, TCB) | For GPC/SEC and sample preparation. Water or impurities affect chromatography and can cause chain hydrolysis/scission during melt testing. | Use with appropriate stabilizers (e.g., BHT in TCB). Degas before use. |

| Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) Detector | Coupled with GPC for absolute MW measurement without relying on column calibration standards. | Provides Mw, Rg, and detects aggregation. Requires precise concentration and dn/dc value. |

Understanding the flow behavior of polymer melts is foundational to controlling processes like injection molding, extrusion, and film formation, where defects such as warpage, sink marks, and residual stresses originate. A central thesis in this field posits that the temperature and pressure dependence of viscoelastic properties is not governed by simple Arrhenius kinetics but by changes in the free volume—the unoccupied space between polymer chains enabling molecular motion. The Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation quantitatively describes this relationship, providing a critical framework for predicting material behavior across processing conditions. This guide explores the fundamental principles, experimental validation, and practical application of free volume theory and the WLF equation in polymer melt research relevant to material scientists and pharmaceutical developers working with polymeric excipients and drug delivery systems.

Theoretical Foundations: Free Volume and Time-Temperature Superposition

The segmental mobility of polymer chains, which dictates viscosity and relaxation times, is primarily controlled by the available free volume (f). As temperature increases, free volume expands, facilitating easier chain movement. The Doolittle equation empirically relates viscosity (η) to free volume:

[ \eta = A \exp\left(\frac{B}{f}\right) ]

where A and B are material constants. The fractional free volume f is often expressed as:

[ f = fg + \alphaf (T - T_g) ]

where ( fg ) is the fractional free volume at the glass transition temperature ( Tg ), and ( \alpha_f ) is the thermal expansion coefficient of the free volume.

The WLF equation is a direct consequence of this free volume model. It describes the shift factor (( a_T )) used in time-temperature superposition (TTS):

[ \log{10}(aT) = \frac{-C1 (T - T{ref})}{C2 + (T - T{ref})} ]

where ( T{ref} ) is a reference temperature (often ( Tg )), and ( C1 ) and ( C2 ) are empirical constants theoretically related to free volume parameters: ( C1 = B/(2.303 f{ref}) ) and ( C2 = f{ref}/\alpha_f ).

Pressure dependence enters because applied pressure reduces free volume, effectively increasing the viscosity and glass transition temperature. A combined pressure-temperature shift factor can be formulated.

Key Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Determining WLF Constants via Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Objective: To obtain the shift factors (( aT )) and calculate WLF constants ( C1 ) and ( C_2 ).

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer discs or rectangular films of specified dimensions (e.g., 1mm thickness).

- Frequency Sweep: Using a parallel plate or torsion rheometer, perform small-amplitude oscillatory shear tests over a range of angular frequencies (e.g., 0.1 to 100 rad/s) at a fixed strain within the linear viscoelastic region.

- Temperature Ramp: Repeat the frequency sweep at multiple temperatures (e.g., ( Tg + 10^\circ)C to ( Tg + 100^\circ)C).

- Master Curve Construction: Select a reference temperature ( T_{ref} ). Horizontally shift the storage (( G' )) and loss (( G'' )) modulus curves along the logarithmic frequency axis to create a single master curve.

- Shift Factor Analysis: Plot ( \log(aT) ) versus ( (T - T{ref}) ). Fit the WLF equation to the data using non-linear regression to extract ( C1 ) and ( C2 ).

Measuring Pressure-Dependent Viscosity Using a Capillary Rheometer

Objective: To quantify the effect of pressure on melt viscosity and free volume.

Protocol:

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a high-pressure capillary rheometer equipped with a pressure transducer at the die entrance.

- Isothermal Tests: At a fixed temperature, extrude the polymer melt through a die of known length and diameter at various piston speeds (shear rates).

- Pressure Variation: Conduct tests at the same temperature but under different applied back-pressures.

- Data Calculation: Correct for pressure drop (Bagley correction) and non-Newtonian flow (Rabinowitsch correction). Calculate apparent viscosity at each pressure condition.

- Model Fitting: Fit data to a modified viscosity model incorporating pressure, such as ( \eta(P) = \eta_0 \exp(\beta P) ), where ( \beta ) is the pressure coefficient.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Typical WLF Constants and Free Volume Parameters for Common Polymers

| Polymer | ( T_g ) (°C) | ( T_{ref} ) (°C) | ( C_1 ) | ( C_2 ) (°C) | ( f_{ref} ) | ( \alpha_f ) (10^-4 /°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | 100 | 100 | 13.7 | 50.0 | 0.032 | 6.4 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | 105 | 105 | 17.5 | 52.0 | 0.025 | 4.8 |

| Polyisobutylene (PIB) | -70 | -70 | 16.6 | 104 | 0.026 | 2.5 |

| Polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) | 30 | 30 | 15.0 | 52.5 | 0.029 | 5.5 |

| Universal Constants | - | - | ~17.4 | ~51.6 | ~0.025 | ~4.8 |

Note: "Universal" constants are approximate averages; material-specific measurement is critical.

Table 2: Pressure Coefficient of Viscosity (( \beta )) at ( T_g + 50^\circ)C

| Polymer | Pressure Coefficient, ( \beta ) (GPa^-1) | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 30 - 40 | Capillary Rheometry |

| Polypropylene (PP) | 15 - 25 | Slit Die Rheometry |

| Polyethylene (HDPE) | 10 - 18 | Falling Cylinder Viscometer |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | 5 - 10 | High-Pressure Rotational Rheometer |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Free Volume & WLF Relationship Logic

Diagram 2: DMA Protocol for WLF Constants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Free Volume & WLF Experiments

| Item/Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Polymer Resins (e.g., NIST standard reference materials) | Provide a baseline with known molecular weight, dispersity, and thermal history to validate experimental methods and data analysis. |

| Quenching Bath (Liquid Nitrogen or Dry Ice/Methanol) | Rapidly cools molded samples to create a reproducible, amorphous state with minimal thermal history for consistent DMA testing. |

| Inert Atmosphere (Nitrogen or Argon Gas) | Prevents oxidative degradation of the polymer melt during high-temperature rheological testing, ensuring data reflects pure thermal/pressure effects. |

| High-Temperature Silicone Oil or Graphite Lubricant | Used in capillary rheometry to minimize friction between piston and barrel, ensuring applied pressure translates fully to the melt. |

| Standard Viscoelastic Reference Fluid (e.g., Polydimethylsiloxane) | Used for calibration and validation of rheometer fixtures (parallel plates, cones) and transducer accuracy before polymer testing. |

| Pressure-Sensitive Calibration Kits (Deadweight testers) | Calibrates pressure transducers in capillary/slit dies to ensure accurate measurement of the pressure coefficient of viscosity (β). |

| Thermal Analysis Standards (e.g., Indium, Tin for DSC) | Calibrates temperature sensors in DSC and DMA to accurately determine Tg, a critical parameter for selecting WLF reference temperature. |

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to four critical flow defects in polymer processing: sharkskin, melt fracture, voids, and splay. These phenomena are framed within the foundational thesis that polymer melt flow behavior is governed by intrinsic viscoelastic and thermodynamic limits. Exceeding these limits—whether of shear stress, tensile stress, stretch rate, or volatility—manifests predictably as specific defects. Understanding this limit-based framework is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with polymeric excipients, hot-melt extrusions, or advanced drug delivery systems, as it enables defect prevention through process design rather than mere post-hoc troubleshooting.

Defect Characterization, Causes, and Limits

The following table summarizes the quantitative parameters, core mechanisms, and exceeded limits associated with each defect, based on current literature.

Table 1: Characterization of Key Polymer Melt Flow Defects

| Defect | Key Exceeded Limit | Typical Critical Value / Onset Range | Primary Mechanism | Common Materials Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharkskin | Critical Wall Shear Stress | 0.1 - 0.4 MPa | Cyclic stick-slip at die exit; surface rupture due to high tensile recoil. | Linear polyethylenes (LLDPE, HDPE), polypropylenes. |

| Melt Fracture | Critical Shear Stress (for gross) / Critical Shear Rate (for onset) | 0.1 - 0.4 MPa (stress) | Cohesive instability within the melt; severe distortion of extrudate shape. | Most polymer melts, especially at high molecular weights. |

| Voids | Volatile Partial Pressure > Local Hydrostatic Pressure | Material/process dependent | Volatile expansion (moisture, residual solvent) or cavitation under negative pressure. | Hygroscopic polymers (e.g., PLA, PVA), resins with residual monomers. |

| Splay | Material-Thermal Decomposition Limit | Polymer-specific (e.g., ~280°C for PVC) | Volatilization of moisture or decomposition products at the melt front during injection molding. | Polymers with moisture, lubricants, or low thermal stability (e.g., PVC, certain polyamides). |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Investigation

Capillary Rheometry for Sharkskin & Melt Fracture

- Objective: Quantify the critical shear stress and shear rate for the onset of surface and gross melt fracture.

- Protocol:

- Instrument: Equip a capillary rheometer with a series of dies having the same diameter but various L/D ratios (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 30).

- Conditioning: Dry polymer pellets thoroughly (≥4 hrs at 80°C under vacuum). Load the rheometer barrel and equilibrate at the target processing temperature (e.g., 180°C for PE).

- Bagley Correction: Perform experiments at constant piston speed. Plot pressure drop vs. L/D for each shear rate. Extrapolate to zero L/D to determine the entrance pressure drop (∆P_entrance), correcting the wall shear stress.

- Onset Detection: Systematically increase the apparent shear rate (via piston speed). Visually inspect (high-speed camera) and measure extrudate surface roughness via laser profilometry. Plot true wall shear stress vs. shear rate.

- Analysis: Identify the point where the flow curve deviates from linearity (onset of sharkskin) and where stress plateaus or oscillates (onset of gross melt fracture). Record the corresponding critical shear stress.

Thermogravimetric-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (TGA-GC/MS) for Splay & Voids

- Objective: Identify volatile species responsible for splay and void formation and link them to processing temperatures.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Divide the polymer/resin into two batches: one "as-received" and one thoroughly dried (e.g., 24 hrs in a desiccated oven at 80°C).

- TGA-GC/MS Coupling: Connect a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) effluent line to a GC/MS via a heated transfer line.

- Volatile Evolution Profile: Heat samples in the TGA from 30°C to 300°C at 10°C/min under inert gas (N₂). The evolved gases are transferred in real-time to the GC/MS for separation and identification.

- Correlation Analysis: Match identified volatiles (water, plasticizers, oligomers) to the specific temperature ranges of their evolution. Correlate major evolution peaks with the processing temperature window and observed defect severity in molded parts.

Visualizing the Defect Formation Pathways

Diagram 1: Pathway from Exceeded Limits to Defect Manifestation (89 chars)

Diagram 2: Workflow for Critical Shear Stress Determination (99 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Polymer Flow Defect Research

| Item / Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Capillary Rheometer | The primary instrument for applying controlled shear and extensional flows, simulating processing conditions to measure viscosity and detect defect onset. |

| Series of Capillary Dies (varying L/D) | Enables Bagley correction for true wall shear stress calculation by separating entrance/exit effects from fully-developed flow. |

| High-Speed Camera (≥ 1000 fps) | Captures the real-time onset and development of extrudate distortions (sharkskin, fracture) at the die exit. |

| Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope or Profilometer | Quantitatively measures surface topology and roughness (Ra, Rz) of extrudates to objectively classify sharkskin severity. |

| TGA-GC/MS Coupled System | Identifies and quantifies trace volatile components (moisture, additives, degradation products) that lead to splay and voids. |

| In-line Pressure Transducers | Mounted along the barrel and die to measure pressure gradients and detect instabilities associated with defect formation. |

| Well-Characterized Polymer Standards (NIST SRM) | Reference materials with known molecular weight and dispersity to calibrate rheological measurements and validate experimental setups. |

| High-Vacuum Drying Oven | Essential for removing moisture, a primary source of volatiles, to establish a baseline "dry" state for controlled experiments. |

| Process Viscometer (In-line Rheometer) | For real-time viscosity monitoring during actual processing (e.g., extrusion), linking lab-scale rheology to production-scale defect formation. |

Characterization and Modeling of Melt Flow for Pharmaceutical Process Design

Within the context of fundamental research on polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation, rheometry is indispensable. The selection of an appropriate rheometric technique—capillary, rotational, or oscillatory shear—directly dictates the quality and applicability of the viscoelastic data acquired. This guide details the core principles, experimental protocols, and data interpretation strategies for these three essential techniques, providing a framework for researchers investigating phenomena such as sharkskin, melt fracture, and phase separation in polymer systems and complex drug formulations.

Core Techniques and Principles

Capillary Rheometry

Capillary rheometry subjects a polymer melt to a controlled, pressure-driven flow through a die of known dimensions, simulating processing conditions like extrusion and injection molding. It is critical for studying high-shear-rate behavior and flow instabilities.

Experimental Protocol:

- Instrument Setup: Select a barrel diameter, capillary die (length L and radius R), and entrance angle (typically 180° or 90°). Common L/D ratios are 10:1 to 40:1. Preheat the barrel and die to the target melt temperature (e.g., 200°C for polyolefins).

- Sample Loading: Pack pre-weighed polymer pellets or powder into the barrel manually or via a specialized loading tool to minimize air entrapment.

- Purging & Conditioning: Apply a low piston speed to purge the system and allow the sample to thermally equilibrate for a standardized period (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Steady-Shear Sweep: Program a series of piston speeds (or pressures). At each step, after a stabilization period, record the steady-state pressure drop (ΔP) and piston force.

- Bagley and Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch Corrections: Perform separate tests with at least two dies of identical diameter but different lengths (L) to determine the Bagley end correction. Apply the Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch equation to correct the wall shear rate for non-Newtonian behavior.

- Data Calculation:

- Apparent Shear Stress: τapp = (ΔP * R) / (2L)

- Apparent Shear Rate: γ̇app = (4Q) / (πR³)

- Corrected values (τw, γ̇w) are derived from the above corrections.

Rotational Rheometry (Steady Shear)

Rotational rheometry uses a motor to apply a controlled torque/rotation to a geometry containing the sample, generating a simple shear flow. It is ideal for characterizing viscosity over a medium shear rate range and yielding behavior.

Experimental Protocol (Parallel Plate or Cone-Plate):

- Geometry Selection & Loading: Select a geometry (e.g., 25 mm diameter parallel plates with 1 mm gap, or a 40 mm cone with 1° angle and 50 μm truncation). Pre-heat the geometry. Load the sample (melt or pre-formed disk) onto the center of the bottom plate.

- Gap Setting & Trimming: Lower the upper geometry to the measuring gap. Trim excess material from the periphery with a heated spatula.

- Normal Force Relaxation: Allow the sample to thermally equilibrate and the normal force to relax to a near-zero baseline (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- Steady Rate Sweep: Program a logarithmic sweep of rotational speeds (e.g., from 0.01 to 100 s⁻¹). At each shear rate step, measure the resulting steady-state torque (M) and normal force (N).

- Data Calculation:

- Shear Stress: τ = (2M) / (πR³) [for parallel plate]

- Shear Rate: γ̇ = (Ω * R) / (h) [for parallel plate, where Ω is angular speed, R radius, h gap]

- Viscosity: η = τ / γ̇

Oscillatory Shear Analysis

Oscillatory analysis applies a small-amplitude, sinusoidal deformation to characterize the linear viscoelastic (LVE) region, probing the material's structure without causing significant disruption.

Experimental Protocol (Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear - SAOS):

- Sample Loading & Gap Setting: Follow the same loading and trimming procedure as for rotational steady shear (Step 1-3 above).

- Strain (or Stress) Amplitude Sweep: At a fixed angular frequency (e.g., ω = 10 rad/s), perform a sweep of increasing oscillatory strain amplitude (γ₀). Determine the critical strain (γ_c) where the storage modulus (G') deviates from its constant plateau value, defining the limit of the LVE region.

- Frequency Sweep: Within the LVE region (at a fixed γ₀ < γ_c), perform a logarithmic sweep of angular frequencies (e.g., 0.01 to 100 rad/s). Record G' (storage modulus), G'' (loss modulus), and complex viscosity η* as functions of frequency.

- Data Interpretation: The frequency sweep provides a "mechanical spectrum" revealing relaxation times, plateau modulus (related to molecular weight between entanglements), and crossover points (G' = G''), which relate to melt transition or gel point behavior.

Table 1: Comparative Scope of Essential Rheometric Techniques

| Technique | Typical Shear Rate Range (s⁻¹) | Key Measurables | Primary Application in Defect Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary | 10⁰ - 10⁶ | Wall shear stress (τw), Apparent viscosity (ηapp), Extrudate swell ratio, Flow curve | High-rate processing defects (melt fracture, sharkskin), Die-swell prediction, Slip analysis |

| Rotational (Steady) | 10⁻³ - 10³ | Shear viscosity (η), Yield stress (τ_y), Normal stress differences (N₁) | Low/medium shear viscosity mapping, Yield behavior of filled systems, Shear thinning index |

| Oscillatory (SAOS) | (Frequency: 10⁻² - 10² rad/s) | Storage/Loss Moduli (G', G''), Complex viscosity (η*), Tan δ, Relaxation spectrum | Molecular structure/entanglements, Thermal transitions, Gelation/curing kinetics, Blend morphology |

Table 2: Representative Data for Common Polymer Melt (e.g., Polypropylene at 200°C)

| Technique | Test Condition | Measured Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary | L/D=20 die, γ̇_w = 1000 s⁻¹ | τ_w = 1.2 x 10⁵ Pa, η = 120 Pa·s | Viscosity under extrusion-like conditions |

| Rotational Steady | Parallel plate, γ̇ = 1 s⁻¹ | η = 1500 Pa·s | Zero-shear viscosity plateau region |

| Oscillatory | ω = 1 rad/s (in LVE) | G' = 500 Pa, G'' = 2000 Pa, η* = 2100 Pa·s | Predominantly viscous liquid behavior (G'' > G') |

Visualizing Rheological Analysis Workflows

Title: SAOS Protocol for Linear Viscoelasticity

Title: Linking Rheometry Data to Flow Defect Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Polymer Melt Rheology

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Fluids (e.g., NIST-traceable silicone oils) | Instrument calibration and validation of shear viscosity and normal force measurements. |

| Inert Purge Gas (e.g., Nitrogen, high-purity) | Prevents oxidative degradation of polymer samples during high-temperature tests in rotational and capillary rheometers. |

| Thermal Stability Package (e.g., Antioxidants like Irganox 1010) | Added to polymer samples to minimize chain scission or crosslinking during extended testing, ensuring data reflects flow properties, not degradation. |

| Release Agents (e.g., Silicone spray, PTFE film) | Applied to tooling (e.g., parallel plates) to aid in sample removal, especially for adhesive melts or cured systems. |

| Geometry Cleaning Solvents (e.g., Xylene, DMF, specialized piranha solution) | Essential for complete removal of residual polymer between tests to prevent contamination and ensure accurate gap setting. Choice depends on polymer solubility. |

| Sample Preparation Aids (e.g., Compression molding press, pelletizer) | Produces uniform, bubble-free disks for rotational rheometry, ensuring reproducible loading and thermal contact. |

1. Introduction: The Rheological Triad in Polymer Processing

Within the broader research on basic principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation, three rheological parameters stand as fundamental pillars: zero-shear viscosity (η₀), relaxation time (λ), and flow activation energy (Eₐ). These parameters govern the polymer's response to stress, dictating its flow into molds, orientation during extension, and ultimate dimensional stability. Incorrect characterization can lead to severe processing defects—such as sharkskin, melt fracture, warpage, and residual stresses—which are critical failure points in industries ranging from medical device manufacturing to pharmaceutical drug delivery systems. This technical guide details the practical experimental determination of these key parameters, providing researchers with robust protocols for predictive material science.

2. Experimental Determination of Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀)

Zero-shear viscosity is the constant viscosity plateau exhibited by a polymer melt at very low shear rates, reflecting the undisturbed equilibrium entanglement network. It is a direct indicator of molecular weight (Mw) for linear polymers.

Protocol: Steady Shear Rate Sweep using Rotational Rheometry

- Equipment: Strain-controlled rotational rheometer with parallel-plate or cone-and-plate geometry. An environmental test chamber for temperature control is mandatory.

- Sample Preparation: Compression-mold a disc of polymer melt approximately 1-2 mm thick and 25 mm in diameter. Ensure no air bubbles are present.

- Procedure:

- Equilibrate the sample at the test temperature (e.g., 180°C, 200°C, 220°C) for 5 minutes to erase thermal history.

- Apply a low-amplitude oscillatory strain (within the linear viscoelastic region) to verify sample stability and adhesion.

- Perform a steady shear rate sweep from a very low rate (e.g., 0.001 s⁻¹) to a higher rate (e.g., 10 s⁻¹), using a logarithmic progression.

- Record the steady-state shear stress (τ) at each shear rate (˙γ).

- Data Analysis: Plot viscosity (η = τ/˙γ) versus shear rate on a log-log scale. Fit the data in the low-shear-rate region to a Carreau-Yasuda or Cross model to extract the zero-shear viscosity plateau value (η₀). The low-shear-rate Newtonian plateau must be observed for a valid measurement.

3. Experimental Determination of Relaxation Time (λ)

The relaxation time characterizes the time scale for polymer chains to relax from a deformed state. It is crucial for understanding elastic effects like die swell.

Protocol: Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) Frequency Sweep

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel-plate geometry.

- Sample Preparation: As per Section 2.

- Procedure:

- At a fixed temperature within the linear viscoelastic regime (confirmed via an amplitude sweep), perform a frequency (ω) sweep from high frequency (e.g., 100 rad/s) to low frequency (e.g., 0.01 rad/s).

- Record the storage modulus (G'), loss modulus (G''), and complex viscosity (η*).

- Data Analysis:

- Crossover Method: Identify the frequency (ωc) where G' = G''. The relaxation time is estimated as λcrossover = 1/ωc.

- Cole-Cole Plot Method: Plot η'' (loss viscosity) vs η' (storage viscosity). Fit the data to a model (e.g., Maxwell) to obtain a discrete or spectrum of relaxation times.

- Maxwell Model Approximation: For a single relaxation time, λmaxwell = η₀ / GN, where GN is the plateau modulus, often approximated from the G' plateau at high frequency.

4. Experimental Determination of Flow Activation Energy (Eₐ)

Flow activation energy quantifies the temperature dependence of viscosity, reflecting the energy barrier for segmental motion. It is vital for predicting flow behavior across processing temperatures.

Protocol: Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS)

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with precise temperature control.

- Sample Preparation: As per Section 2.

- Procedure:

- Perform SAOS frequency sweeps (as in Section 3) at multiple temperatures (typically spanning a 30-50°C range above the polymer's Tg or Tm).

- Ensure data at each temperature captures the terminal and transition zones.

- Data Analysis:

- Choose a reference temperature (Tref).

- Horizontally (aT) and vertically (bT) shift the modulus curves at other temperatures to superpose them onto the master curve at Tref.

- The horizontal shift factors (aT) follow the Arrhenius or Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation.

- For temperatures sufficiently above Tg (typically T > Tg + 100°C), fit the aT data to the Arrhenius equation: aT = exp[Eₐ/R * (1/T - 1/Tref)], where R is the gas constant.

- Plot ln(a_T) vs. 1/T. The slope of the linear region is Eₐ/R, from which Eₐ is calculated.

5. Tabulated Data Summary

Table 1: Representative Rheological Parameters for Common Polymers (at reference temperature T_ref)

| Polymer | Zero-Shear Viscosity, η₀ (Pa·s) | Relaxation Time, λ (s) | Flow Activation Energy, Eₐ (kJ/mol) | Measurement Temp. (T_ref) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | 5.0 x 10³ | 1.2 | 48 | 190°C |

| HDPE | 2.5 x 10⁴ | 4.5 | 29 | 190°C |

| PP | 8.0 x 10³ | 2.1 | 41 | 200°C |

| PS | 1.0 x 10⁵ | 15.0 | 92 | 180°C |

| PC | 3.5 x 10⁴ | 8.7 | 165 | 280°C |

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols Summary

| Parameter | Core Experiment | Critical Control Variables | Primary Analytical Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| η₀ | Steady Shear Sweep | Very low shear rates, thermal equilibrium, gap setting | Carreau-Yasuda, Cross |

| λ | SAOS Frequency Sweep | Linear Viscoelastic strain, full frequency range | Crossover, Maxwell, Cole-Cole |

| Eₐ | Multi-Temp. SAOS (TTS) | Thermal stability, broad temperature range | Arrhenius Equation |

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Strain-Controlled Rotational Rheometer | Primary instrument for applying precise deformation and measuring stress response in shear. |

| Parallel-Plate Geometry (8-25 mm) | Standard fixture for polymer melts; easy sample loading and gap adjustment to accommodate thermal expansion. |

| Cone-and-Plate Geometry | Provides homogeneous shear rate; ideal for absolute viscosity measurements but sensitive to sample loading and gap precision. |

| Environmental Test Chamber (Oven) | Enables precise, stable, and uniform temperature control for temperature-dependent studies and TTS. |

| Inert Gas (Nitrogen) Purge System | Prevents oxidative degradation of polymer samples during high-temperature testing. |

| Compression Molding Press | Used to prepare uniform, bubble-free disc-shaped samples from pellets or powder. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., NIST Polyisobutylene) | Used for rheometer calibration and validation of experimental protocols. |

| Silicone Oil or Graphite Paste | Applied to sample edges to prevent drying and suppress edge fracture during testing. |

7. Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for Determining Rheological Parameters

Diagram Title: Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS) Method for Eₐ

Applying the Cox-Merz Rule and Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS) for Extended Predictions

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on Basic principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation research, details the synergistic application of two foundational rheological principles. Understanding the viscoelastic flow of polymer melts is critical for predicting processing behavior and minimizing defects like sharkskin, melt fracture, or inhomogeneities in final products, including pharmaceutical polymeric carriers and drug-eluting implants. The Cox-Merz Rule and Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS) provide powerful, efficient frameworks for extending the predictive range of rheological data, enabling researchers to model material behavior across timescales and conditions not easily accessible via direct experimentation.

Foundational Principles

The Cox-Merz Rule

The Cox-Merz rule is an empirical correlation stating that the shear-rate dependence of the steady-state viscosity, η(γ̇), is equal to the frequency dependence of the complex viscosity, |η(ω)|, when the shear rate and angular frequency are numerically equal. [ \eta(\dot{\gamma}) = |\eta^(\omega)| \quad \text{for} \quad \dot{\gamma} = \omega ] This allows the prediction of steady, non-linear shear flow behavior (relevant to extrusion, molding) from small-amplitude oscillatory shear measurements (non-destructive, easy to perform).

Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS) Principle

TTS, or the method of reduced variables, exploits the thermorheological simplicity of many polymers. It posits that the effect of temperature on viscoelastic properties (like relaxation time) is equivalent to a horizontal shift along the logarithmic time or frequency axis. Master curves are constructed by shifting data from multiple temperatures to a single reference temperature (T₀). [ aT = \frac{\eta0(T)}{\eta0(T0)} \approx \frac{\tau(T)}{\tau(T0)} ] [ \log(\omega{red}) = \log(\omega) + \log(aT) ] Where (aT) is the temperature shift factor, often modeled by the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) or Arrhenius equations.

Synergistic Application for Extended Predictions

Combining these rules enables the prediction of viscosity over an exceptionally broad range of effective shear rates. Oscillatory frequency sweep data at multiple temperatures are shifted via TTS to create a broad-frequency master curve of complex viscosity. The Cox-Merz rule then allows this master curve to be interpreted as a steady-shear viscosity master curve over an equivalently broad range of shear rates, far exceeding the practical limits of a rotational rheometer.

Table 1: Typical Shift Factor (a_T) Values for Common Polymer Types (Reference T₀ = 200°C)

| Polymer Type | WLF Constant C1 | WLF Constant C2 | Activation Energy Ea (kJ/mol) | Applicable Temp Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (atactic) | 8.86 | 101.6 | 200-250 | 150-250 |

| Polypropylene | 4.52 | 150.5 | 40-50 | 180-240 |

| Polyethylene (HDPE) | 3.65 | 135.7 | 25-35 | 160-220 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | 12.5 | 95.0 | 250-300 | 150-220 |

| PLGA (50:50) | 15.2 | 110.0 | 80-100 | 37-100 |

Table 2: Validity Limits of the Cox-Merz Rule for Various Systems

| Material System | Typically Valid? | Deviations Observed At/In | Key Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear, Flexible Homopolymers | Yes | Very high γ̇/ω | Homogeneous melt state |

| Highly Branched Polymers | Moderate | Moderate rates | Branching relaxation dynamics |

| Polydisperse Melts | Yes | --- | Broad MWD often improves fit |

| Polymer Blends | No/Conditional | Low & high rates | Phase-separated structures |

| Filled Systems / Composites | Often No | All rates | Particle network, yield stress |

| Concentrated Solutions | Conditional | High concentrations | Solvent-polymer interactions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a TTS-Cox-Merz Master Curve

Objective: Generate a steady-shear viscosity prediction spanning 10^-3 to 10^6 s^-1. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry polymer pellets/vacuum-dry to remove moisture. Melt-press or load into rheometer with environmental control.

- Temperature Ramp (Optional): Perform a temperature sweep in oscillatory mode (ω = 10 rad/s, γ = 1%) to identify the stable melt region and degradation temperature.

- Frequency Sweeps at Multiple Temperatures:

- Set parallel plate geometry (e.g., 25 mm diameter, 1 mm gap).

- For each target temperature (T = T₀, T₀±10°C, T₀±20°C...), equilibrate for 5 min.

- Perform an oscillatory frequency sweep from 0.01 to 100 rad/s at a constant strain within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

- Record G'(ω), G''(ω), and |η*(ω)|.

- TTS Master Curve Construction:

- Choose a reference temperature T₀ (often near the middle of the tested range).

- Plot log(|η*|) vs. log(ω) for all temperatures.

- Horizontally shift (log(aT)) data from each temperature onto the T₀ data set to create a smooth master curve. Vertical shifts (bT) are sometimes minimal for viscosity.

- Fit the WLF equation to the obtained log(a_T) vs. (T-T₀) data.

- Cox-Merz Application:

- Relabel the x-axis of the master curve from log(ωred) to log(γ̇eff).

- The curve is now a prediction of steady-shear viscosity η(γ̇) over the extended reduced frequency range.

- Validation (Critical): Perform actual steady-shear rate sweeps at T₀ over the instrument's achievable range (e.g., 0.01 to 100 s^-1). Overlay data onto the predicted master curve to validate the superposition.

Protocol: Assessing Cox-Merz Validity

Objective: Test empirical rule applicability for a new material. Procedure:

- Oscillatory Test: As per Step 3 above at a single temperature.

- Steady-Shear Test: On the same sample and geometry, perform a steady shear rate sweep from low to high rates, ensuring steady-state at each point.

- Direct Comparison: Plot η(γ̇) and |η*(ω)| on the same log-log axes. Agreement confirms validity. Discrepancies indicate structural changes under shear (e.g., alignment, breakup).

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: TTS and Cox-Merz Application Workflow (88 chars)

Diagram 2: Logical Relationship Between TTS and Cox-Merz (73 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for TTS & Cox-Merz Experiments

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Stress- or Strain-Controlled Rheometer | Core instrument for applying controlled shear/deformation and measuring stress response. Requires precise temperature control (±0.1°C). |

| Parallel Plate or Cone-and-Plate Geometry | Standard geometries for polymer melts. Plates offer easy loading/cleaning; cones provide homogeneous shear. |

| Environmental Test Chamber (ETC) | Encloses geometry to provide inert atmosphere (N₂) to prevent oxidation and ensure precise temperature uniformity. |

| Polymer Pellets/Powder (e.g., PLGA, PEO) | Test material. Must be characterized for molecular weight, dispersity, and thermal history. |

| Vacuum Oven | For pre-drying hygroscopic polymers (e.g., polyesters) to remove moisture that plasticizes and alters flow. |

| Standard Reference Material (e.g., NIST 1490) | Used for calibration and validation of rheometer torque and inertia. |

| Silicone Oil or Grease | Applied to sample edge to prevent moisture uptake and suppress sample drying/degradation during test. |

| WLF/Arrhenius Fitting Software | For calculating shift factors (a_T) and building master curves (often built into rheometer software). |

| High-Temperature Thermal Paste | Improves thermal contact between Peltier plate and geometry for faster equilibration. |

The foundational principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation research establish a critical framework for advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing. This guide, situated within that context, posits that successful Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) and injection molding of amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) hinge on the rigorous integration of two key rheological datasets: shear-viscosity curves and time-temperature-stability maps. Defects like phase separation, degradation, and incomplete mixing are direct consequences of processing outside a material's defined "processing window." This document provides a technical protocol for defining this window, thereby linking core polymer science to robust, scalable pharmaceutical production.

Foundational Principles: Viscosity and Stability

Rheology: The Shear Viscosity Curve

Viscosity (η) as a function of shear rate (γ̇) dictates the flow resistance and mixing efficiency during processing. Most polymer-excipient systems used in HME are shear-thinning, described by the power-law model: η = K * γ̇^(n-1), where K is the consistency index and n is the power-law index (n < 1 for shear-thinning).

Table 1: Typical Power-Law Parameters for Common HME Polymers

| Polymer/System | Temperature (°C) | Consistency Index, K (Pa·sⁿ) | Power-Law Index, n | Applicable Shear Rate Range (s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMCAS (LG) | 150 | 8500 | 0.45 | 10 - 1000 |

| PVP VA64 | 140 | 3200 | 0.55 | 10 - 1000 |

| Soluplus | 130 | 5200 | 0.50 | 10 - 1000 |

| Copovidone | 150 | 2800 | 0.60 | 10 - 1000 |

Physical Stability: The Time-Temperature-Transformation (TTT) Map

The stability map defines the boundaries of the amorphous system's single-phase state. Key boundaries include the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), the degradation temperature (Tdeg), and the crystallization onset time (τ_cryst) at a given temperature.

Table 2: Critical Stability Parameters for Model ASD Formulations

| ASD Formulation (20% Drug Load) | Tg (°C) | Tdeg (Onset, °C) | τ_cryst at T > Tg+50°C (min) | Recommended Max Processing Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itraconazole / HPMCAS | 105 | 220 | 8.5 | 5 |

| Ritonavir / PVP VA64 | 85 | 190 | 4.2 | 3 |

| Celecoxib / Soluplus | 72 | 230 | >15 | 10 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Generating Shear Viscosity Curves via Capillary Rheometry

Objective: To measure apparent viscosity across a range of shear rates relevant to HME (1-1000 s⁻¹). Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit. Method:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-dry physical mixture of API and polymer.

- Rheometer Setup: Equip with a cylindrical die (L/D = 20:1 to 30:1). Apply Bagley and Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch corrections.

- Conditioning: Load sample, allow to equilibrate at test temperature (e.g., 130°C, 150°C, 170°C) for 5 min under minimal pressure.

- Measurement: Apply piston to extrude material at a series of controlled speeds. Record pressure drop (ΔP) across the die for each speed.

- Data Calculation: Calculate apparent shear rate (32Q/πD³) and wall shear stress (ΔP D/(4L)). Derive apparent viscosity.

- Model Fitting: Fit corrected data to the power-law model at each temperature.

Protocol B: Constructing Stability Maps via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) & Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Objective: To define Tg, Tdeg, and isothermal crystallization kinetics. Method:

- Tg & Tdeg Determination: Using a sealed Tzero pan, run a modulated DSC (mDSC) scan from 25°C to 250°C at 3°C/min. Tg is identified from the reversible heat flow step. Run a parallel TGA experiment under nitrogen at 10°C/min to determine onset of degradation (typically >1% mass loss).

- Crystallization Kinetics (Isothermal): a. Heat sample 30°C above its predicted melting point to erase thermal history. b. Quench rapidly (>50°C/min) to a target isothermal temperature (Tiso) above Tg (e.g., Tg+20°C, Tg+50°C). c. Hold at Tiso and monitor heat flow for exothermic crystallization events. d. Record the time to crystallization onset (τcryst). Repeat for multiple Tiso points.

- Map Construction: Plot Tg line, Tdeg line, and iso-τ_cryst contours (e.g., 1-min, 5-min, 10-min crystallization onset) on a Temperature vs. Log(Time) graph.

Protocol C: Defining the Integrated Processing Window

Objective: To superimpose rheological and stability data to identify optimal processing parameters. Method:

- Plot Axes: Create a master plot with Temperature (T) on the y-axis and Log(Shear Rate) or Log(Residence Time) on the x-axis.

- Overlay Viscosity Contours: Plot iso-viscosity lines (e.g., 100 Pa·s, 1000 Pa·s, 5000 Pa·s) using data from Protocol A.

- Overlay Stability Boundaries: Plot the following from Protocol B:

- Lower bound: Tg (process must be >Tg for flow).

- Upper bound: Minimum of Tdeg and temperature at which τ_cryst < intended residence time.

- Right bound: Maximum allowable residence time from stability map.

- Identify Window: The operable processing window is the region bounded by: T > Tg, T < (Tdeg & T_cryst-limit), viscosity between 100-10,000 Pa·s (pumpable but not too fluid), and residence time less than the stability limit.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Processing Window Design

Diagram 2: Integrated Processing Window Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Viscosity & Stability Mapping Experiments

| Item & Typical Supplier Example | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Capillary Rheometer (e.g., Malvern Rosand RH7, Gottfert Rheograph) | Applies controlled shear rates at high temperature to measure pressure drop and calculate apparent viscosity. |

| Twin-Screw Melt Extruder (Bench-top, e.g., Thermo Fisher Process 11, Leistritz Nano-16) | Provides real-world shear and thermal history for validating processing windows. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC, e.g., TA Instruments Q2000, Mettler Toledo DSC 3) | Measures glass transition (Tg), melting points, and isothermal crystallization kinetics. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA, e.g., TA Instruments Q50, Netzsch TG 209) | Determines thermal decomposition temperature (Tdeg) and moisture content. |

| Standard Capillary Dies (L/D=20:1, 30:1; 1mm diameter) | For capillary rheometry; different L/D ratios allow for Bagley correction. |

| Hermetic/Secaled Tzero DSC pans (e.g., TA Instruments) | Prevents sample evaporation during high-temperature DSC runs, ensuring accurate Tg and stability data. |

| Model Polymer Systems (e.g., HPMCAS (AQOAT), PVP VA64, Soluplus from BASF) | Well-characterized carriers with known rheological and stability profiles for method development. |

| Model APIs (e.g., Itraconazole, Ritonavir, Celecoxib) | Poorly soluble compounds commonly used in ASD research to test formulation stability. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glove Box (for sample loading) | Prevents moisture uptake by hygroscopic polymers during sample preparation for sensitive measurements. |

Application to HME and Molding Processes

The derived processing window directly informs equipment parameters:

- HME: Barrel temperature profile must fall within the window's temperature bounds. Screw speed (which impacts shear rate and residence time) must be chosen to keep the material within the viscosity contours and left of the maximum time boundary.

- Injection Molding: Melt temperature and mold temperature are constrained by the window. Hold time and injection speed must be balanced to prevent crystallization (time boundary) while ensuring complete cavity fill (viscosity-dependent flow).

Validating the window involves processing at a point within it and at points near its boundaries, followed by analytical characterization (e.g., XRD, DSC, dissolution) to confirm the absence or presence of predicted defects like crystallization or degradation. This closed-loop process solidifies the fundamental link between polymer melt flow behavior, stability, and final product quality.

The formulation of Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) is a critical strategy for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. The success of an ASD hinges on the judicious selection of a polymeric carrier and the precise optimization of manufacturing parameters. This case study is framed within a broader thesis investigating the basic principles of polymer melt flow behavior and defect formation. Understanding these principles—such as viscosity, shear thinning, elastic recovery, and thermal degradation—is paramount for selecting appropriate polymers and processing conditions to manufacture stable, defect-free ASD formulations via hot-melt extrusion (HME) or similar thermo-mechanical methods.

Core Polymer Selection Criteria for ASD

Polymer selection is the foundational step. The ideal polymer must achieve dual objectives: forming a stable, supersaturated solution of the drug and exhibiting favorable melt processing behavior.

Key Selection Parameters:

- Drug-Polymer Miscibility & Interaction: Governs physical stability and prevents recrystallization. Assessed via Hansen Solubility Parameters, Flory-Huggins interaction parameter (χ), and spectroscopic methods.

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): The polymer's Tg, and the resultant Tg of the drug-polymer blend, dictates the processing temperature and long-term physical stability at storage conditions.

- Melt Rheology: Directly tied to the thesis core. A polymer's viscosity (η) as a function of temperature and shear rate determines processability, required torque, and mixing efficiency. Ideal polymers for HME show significant shear thinning.

- Hydrophilicity & Drug Release: Affords dissolution rate enhancement.

- Chemical Stability: Must resist degradation at processing temperatures.

Table 1: Common ASD Polymers and Their Key Properties

| Polymer (Abbreviation) | Chemical Nature | Typical Tg (°C) | Key Rheological/Melt Behavior | Primary Selection Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Amorphous, hydrophilic | ~150-180 | Low melt viscosity; prone to thermal degradation if not plasticized. | High solubilizing capacity, good for spray drying. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone-vinyl acetate copolymer (PVP-VA) | Amorphous, hydrophilic | ~105-110 | Broad processing window, good thermoplasticity. | Excellent balance of processability (lower Tg than PVP) and drug stabilization. |

| Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) | Amorphous, hydrophilic | ~150-180 (varies) | High melt viscosity; requires plasticizer/co-processant for HME. | Robust precipitation inhibition, common in commercial products. |

| Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate (HPMC-AS) | Amorphous, pH-dependent | ~115-135 (grades) | Better thermoplasticity than HPMC; LF grade is optimal for HME. | Superior drug stabilization and pH-triggered release. |

| Soluplus | Polyvinyl caprolactam–polyvinyl acetate–PEG graft copolymer | ~70 | Excellent thermoplasticity, broad HME processing window. | Specifically designed for HME; good bioavailability enhancement. |

Linking Melt Flow Behavior to Parameter Selection & Defect Formation

The principles of polymer melt flow are directly applied to parameter optimization. Key defects in ASD manufacturing (e.g., poor dispersion, degradation, porosity) originate from misunderstood rheology.

Table 2: Critical Processing Parameters, Rheological Basis, and Associated Defects

| Processing Parameter | Rheological Principle & Impact | Optimized Outcome | Potential Defect if Misapplied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Temperature (T) | Must be > Tg of blend to induce flow. Follows Arrhenius-type η(T) relationship. High T lowers η but risks degradation. | Sufficient molecular mobility for mixing without degradation. | Drug/Polymer Degradation (excessive T), High Torque/Stalling (insufficient T). |

| Screw Speed (RPM) / Shear Rate (γ̇) | Most polymers are shear-thinning: η decreases as γ̇ increases. Higher RPM increases shear, improving mixing but also shear heating. | Homogeneous drug distribution via distributive/dispersive mixing. | Incomplete Dispersion (low shear), Thermal Degradation (excessive shear heating). |

| Feed Rate (Q) | Interacts with screw speed to determine specific mechanical energy (SME) and residence time distribution (RTD). | Controlled RTD for consistent product quality. | Poor Content Uniformity (fluctuating RTD), Degradation (long RTD). |

| Screw Configuration | Governs the balance of conveying, mixing, and shear stress. Kneading blocks induce dispersive mixing. | Designed shear profile for the specific drug-polymer system. | Agglomerates (insufficient mixing), Fragile Particle Breakdown (excessive shear). |

Diagram 1: Parameter-flow-defect interrelationship. (Max width: 760px)

Experimental Protocols for Selection & Characterization

Protocol 1: Determination of Drug-Polymer Miscibility (via Tg Measurement)

Objective: Predict physical stability of the ASD. Method: Prepare small-scale binary mixtures (e.g., 10-30% drug in polymer) by solvent evaporation. Analyze using Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (mDSC). Procedure:

- Hermetically seal 5-10 mg samples in Tzero pans.

- Run mDSC from -20°C to 200°C (above Tg of both components) at 2°C/min with a modulation amplitude of ±0.5°C every 60 seconds.

- Analyze the reversing heat flow signal. A single, composition-dependent Tg intermediate between the drug and polymer Tg values indicates miscibility. Two distinct Tgs suggest phase separation.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Melt Rheology for Processability

Objective: Guide HME parameter selection (temperature, screw speed). Method: Use a parallel-plate or capillary rheometer on pure polymer or polymer-plasticizer blends. Procedure:

- Condition polymer pellets/ powder at relevant humidity.

- Perform a temperature sweep (e.g., 120-180°C) at constant frequency to identify the temperature range where complex viscosity (η*) falls within an extrudable range (typically 100-10,000 Pa·s).

- Perform a frequency sweep (simulating shear rate) at the target processing temperature to characterize shear-thinning behavior (power-law index, n).

Protocol 3: Small-Scale HME Feasibility and Stability Study

Objective: Screen multiple polymers and drug loads. Method: Use a micro-compounder or twin-screw extruder (TSE) with small batch capability. Procedure:

- Pre-blend drug and polymer at desired ratio (e.g., 10:90).

- Set TSE zones based on rheology data (start ~20°C above blend Tg). Use a modest screw speed (e.g., 100 RPM) and feed rate.

- Collect extrudate, observe visually for clarity/opacity, and mill.

- Store milled extrudates under accelerated conditions (40°C/75% RH) in open and closed containers. Analyze by X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) and DSC at time points (0, 1, 2, 4 weeks) to monitor recrystallization.