Polymer Structure and Morphology: Fundamentals, Characterization, and Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery

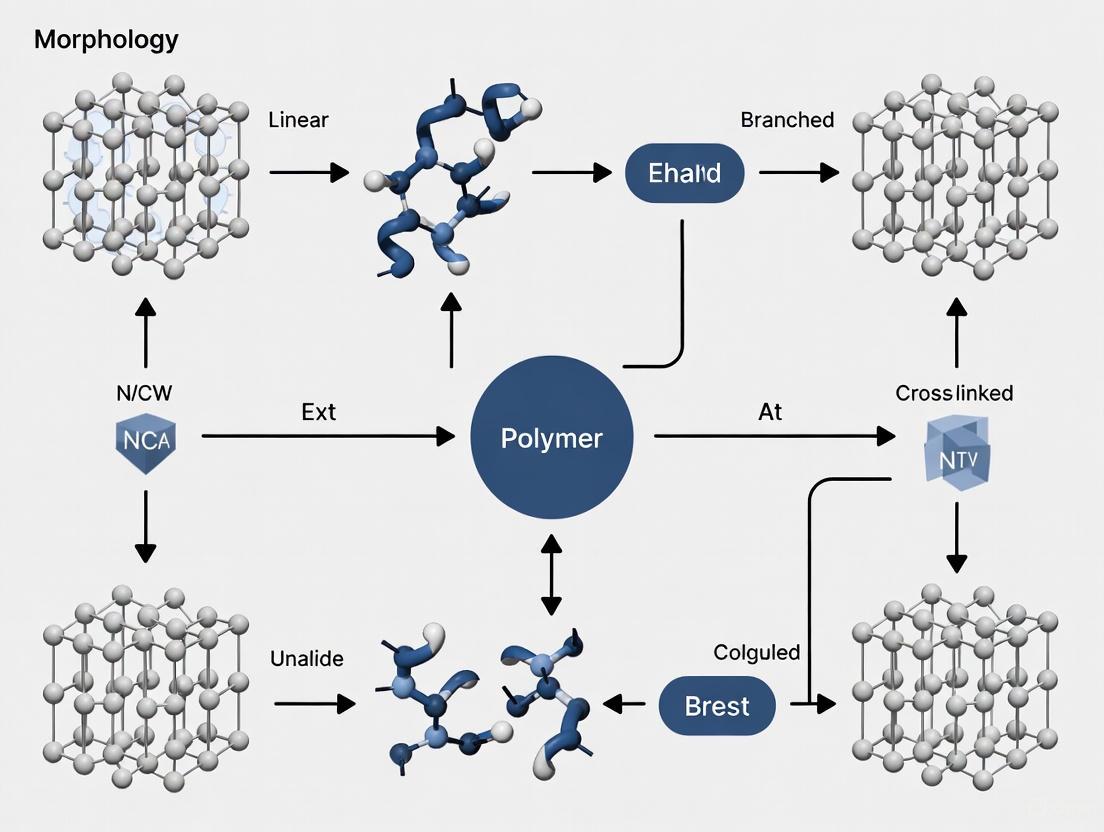

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of polymer structure and morphology, detailing their profound influence on the physical, mechanical, and biological properties of polymeric materials.

Polymer Structure and Morphology: Fundamentals, Characterization, and Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of polymer structure and morphology, detailing their profound influence on the physical, mechanical, and biological properties of polymeric materials. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges fundamental concepts with cutting-edge applications. The scope spans from the foundational principles of chain arrangement and crystallinity to advanced characterization methodologies, strategic optimization for troubleshooting, and comparative validation of material performance. Special emphasis is placed on the role of morphology in designing smart polymeric drug delivery systems, biodegradable implants, and other advanced biomedical technologies, offering a holistic resource for material selection and innovation in the pharmaceutical and biomedical fields.

The Blueprint of Polymers: Understanding Structure-Property Relationships from Chains to Crystals

Polymer morphology is a physical phenomenon that focuses on the study of the structures and relationships of polymers on a large scale [1]. This discipline is fundamentally concerned with the arrangement of polymer molecules, which can be classified as amorphous, crystalline, or semi-crystalline [1]. Most practical polymers exhibit a semi-crystalline structure, consisting of small crystalline regions (crystallites) surrounded by amorphous domains [1]. The study of polymer morphology encompasses an interdisciplinary approach ranging from the nanolevel (polymer structure, conformation, crystallinity) to the macrolevel (surface morphology of final products, fibers, foils, blends, and composites) [1].

Understanding polymer morphology is crucial because it directly influences a wide range of material properties, including mechanical strength, thermal stability, chemical resistance, degradation behavior, and electrical characteristics [2] [1]. The morphology of a polymer is not merely a theoretical concept but a practical determinant of material performance across industries including packaging, biomedical devices, automotive, aerospace, and electronics [1] [3]. The arrangement of molecules on a large scale ultimately governs how polymers will behave in specific applications, making morphological control and analysis essential aspects of polymer science and engineering.

Structural Hierarchy and Classification

Fundamental Morphological Types

The arrangement of polymer chains gives rise to three primary morphological classifications, each with distinct structural characteristics and material properties. Amorphous polymers exhibit a random arrangement of molecular chains without long-range order, resulting in materials that are typically transparent and exhibit gradual softening upon heating [1]. Common examples include polystyrene (PS), polycarbonate (PC), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [1]. These materials lack a definitive melting point and are characterized by their glass transition temperature (Tg).

In contrast, crystalline polymers possess highly ordered regions where polymer chains are arranged in regular patterns [1]. These materials include polyethylenes (PE), polypropylenes (PP), polyamides (PA), and poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) [1]. Crystalline regions contribute to enhanced mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and thermal stability, though they typically reduce optical clarity.

Most commercially important polymers are semi-crystalline, featuring a combination of crystalline domains (crystallites) dispersed within an amorphous matrix [1]. This dual-phase structure creates materials with balanced properties, leveraging the strength of crystalline regions while maintaining some flexibility from amorphous areas. The relative proportion of crystalline to amorphous regions (degree of crystallinity) significantly influences material performance.

Multi-Scale Structural Organization

Polymer morphology extends across multiple scales of organization, from molecular arrangement to macroscopic structure. At the most fundamental level, molecular architecture (tacticity, branching, crosslinking) influences chain packing and mobility [1]. These molecular features give rise to characteristic superstructures, with spherulites representing the most commonly observed morphological form in crystalline and semi-crystalline polymers [2].

Spherulites are spherical polycrystalline aggregates that develop from crystalline growth originating from a central nucleus, producing characteristic Maltese cross patterns under polarized light [2]. These structures represent an intermediate scale of organization between molecular arrangement and bulk material properties. Prior to full spherulite development, polymers may form sheaf-like precursors known as axialites or hedrites [2].

At the macroscopic level, processing conditions further influence morphology through the development of orientation, skin-core effects in molded parts, and the distribution of fillers or reinforcing agents [1]. This hierarchical organization across scales means that polymer properties are intrinsically determined by structural features spanning from monomer structure to aggregated structures [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Polymer Morphological Types and Their Characteristics

| Morphological Type | Structural Features | Example Polymers | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous | Random chain arrangement, no long-range order | PS, PC, PMMA, ABS | Transparent, gradual softening, isotropic |

| Crystalline | Regular chain packing, long-range order | PE, PP, PA, PTFE | Opaque, sharp melting point, strong, chemical resistant |

| Semi-Crystalline | Crystallites embedded in amorphous matrix | PBT, POM, PEEK | Combination of strength and flexibility, often opaque |

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Microscopy and Imaging Methods

A diverse array of characterization techniques enables comprehensive analysis of polymer morphology across multiple length scales. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provides high-resolution imaging of surface topography and is particularly valuable for examining fracture surfaces, filler distribution, and phase separation in polymer blends [4] [1]. For example, SEM imaging has been effectively employed to analyze the morphology of PLA/PCL blends with nano-silica, revealing how increasing PCL content reduces the size of spherical PCL elements and how silica addition leads to more granular structures [4].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) offers superior resolution for examining internal structure and fine morphological details, including crystalline lamellae and domain sizes in nanostructured polymers [1]. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides three-dimensional surface topography with nanometer-scale resolution without requiring conductive coatings, making it ideal for studying surface morphology, phase separation, and mechanical properties at the nanoscale [1]. Optical microscopy, particularly when used with polarized light, remains invaluable for examining spherulitic structures and larger-scale morphological features [2] [1].

Scattering and Diffraction Techniques

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is a fundamental tool for investigating crystalline structure and monitoring changes in crystallinity during polymer processing or degradation [2]. XRD analysis can detect the appearance of crystallinity in initially amorphous polymers, as demonstrated in studies of PLA100 during degradation where diffraction peaks emerged after 18 weeks and became more intense over time, with crystallinity reaching 50% after 110 weeks [2]. Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) provides information on crystal structure and orientation, while small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) characterizes larger-scale structures such as lamellar thickness and long periods.

Neutron scattering techniques, including Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS), have been particularly valuable for studying polymer morphology in solutions, melts, and thin films [2]. The ability to manipulate contrast through selective deuteration makes neutron scattering powerful for investigating phase behavior in blends and block copolymers [2].

Thermal and Spectroscopic Analysis

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is widely used to study thermal transitions including glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm), and crystallization behavior [1]. These thermal properties are intimately connected to polymer morphology, as the degree of crystallinity and crystal perfection directly influence melting behavior and transition temperatures [1]. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) provides information about viscoelastic properties and phase behavior through measurements of storage and loss moduli as functions of temperature and frequency [1].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, particularly in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode, offers insights into chemical structure, crystallinity, and intermolecular interactions [4]. For instance, FTIR-ATR analysis has demonstrated that SiO₂ nanoparticles influence the structure ordering of PLA in blends with PCL [4]. These techniques are often combined with microscopy methods to correlate morphological features with molecular-level interactions and thermal behavior.

Quantitative Analysis of Polymer Blends: A Case Study

Experimental Protocol for Morphological Analysis

Recent research on PLA/PCL blends with nano-silica provides an exemplary case study in comprehensive morphological characterization [4]. The experimental methodology encompasses sample preparation, morphological imaging, surface analysis, and spectroscopic characterization:

Sample Preparation: Blends were produced with varying concentrations of PLA (Ingeo 3251D), PCL (Capa 6800), and fumed silica nanoparticles (Aerosil200) [4]. The PLA/PCL ratios studied included 100/0, 90/10, 80/20, 70/30, 60/50, and 50/50, with silica additions of 1 wt.% and 3 wt.% [4]. Samples were typically prepared using melt blending techniques such as extrusion, followed by compression molding or injection molding to create test specimens [4].

SEM Imaging and EDS Mapping: Samples were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy to examine phase morphology and distribution of blend components [4]. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) mapping provided elemental distribution data, particularly for silicon from nano-silica [4]. This approach revealed that in PLA/PCL blends without PCL, SiO₂ formed clusters with silicon concentration reaching up to ten times the nominal concentration [4]. With 3% SiO₂ added to PCL-containing blends, the structure became more granular, with Si protrusions showing 29.25% Si in PLA/PCL 90/10 blends and 10.61% in PLA/PCL 70/30 blends [4].

Surface Characterization: Water contact angle measurements were performed to determine surface free energy and adhesion parameters [4]. Results demonstrated that the addition of SiO₂ nanoparticles increased the contact angle of water, making the surface more hydrophobic [4].

FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy: Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflection mode was used to analyze chemical structure and interactions [4]. This analysis showed that SiO₂ nanoparticles influenced the structure ordering of PLA in blends with equal portions of PLA and PCL [4].

Key Findings and Data Analysis

The quantitative morphological analysis revealed significant insights into blend behavior and component interactions. The reduction in spherical PCL element size with increasing PCL content indicated improved interfacial interactions between blend components [4]. EDS mapping confirmed the affinity of SiO₂ to be encapsulated by PCL, explaining the compatibilizing effect of nanoparticles in the blend system [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Morphological Data from PLA/PCL/SiO₂ Blend Study [4]

| Blend Composition | SiO₂ Content (wt.%) | Key Morphological Observations | Quantitative Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/PCL 100/0 | 1-3 | SiO₂ clusters formation | Si concentration up to 10× nominal |

| PLA/PCL 90/10 | 3 | Granular structure with Si protrusions | 29.25% Si at protrusion sites |

| PLA/PCL 70/30 | 3 | Reduced spherical elements, improved interface | 10.61% Si at protrusion sites |

| All PCL-containing | 1-3 | Increased hydrophobicity | Higher water contact angle |

Advanced Topics and Recent Developments

Computational Approaches and Multimodal Representation

Recent advances in computational methods have revolutionized the study and prediction of polymer morphology-property relationships. The Uni-Poly framework represents a novel approach that integrates diverse data modalities to achieve a comprehensive and unified representation of polymers [3]. This framework encompasses all commonly used structural formats, including SMILES, 2D graphs, 3D geometries, and fingerprints, while additionally incorporating domain-specific textual descriptions to enrich representation [3].

Experimental results demonstrate that Uni-Poly outperforms single-modality and other multi-modality baselines across various property prediction tasks [3]. For glass transition temperature (Tg) prediction, the framework achieved an R² value of approximately 0.9, while thermal decomposition temperature (Td) and density (De) showed R² values of 0.7-0.8 [3]. The integration of textual descriptions provided complementary information that structural representations alone could not capture, particularly for challenging properties like melting temperature (Tm), where Uni-Poly demonstrated a 5.1% increase in R² compared to the best baseline [3].

Current Research Directions

Contemporary research in polymer morphology spans diverse areas, with significant focus on sustainable and functional materials. Current investigations include the development of bio-based and biodegradable polymers with controlled morphology [5], polymer composites and nanocomposites with tailored interfacial properties [6] [5], and functional polymers for advanced applications in biomedical devices, electronics, and energy storage [7] [3].

Recent studies have explored porous PBAT monoliths fabricated via thermally induced phase separation (TIPS), where annealing treatment significantly enhanced elasticity by improving defective crystals formed during phase separation [7]. Other investigations have focused on controlling the phase structure of cured epoxy resins through the introduction of imide groups, which improved compatibility and resulted in smaller phase-separated structures [7].

The emerging understanding of multiple hydrogen bonds as tools to enhance mechanical and mechanoresponsive properties represents another advanced direction [7]. Research in this area categorizes hydrogen-bonding motifs into "rigid" and "flexible" types, with flexible H-bonds (such as aliphatic diols) providing multiple conformationally diverse binding modes that enable efficient energy dissipation and network recovery under strain [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Morphological Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Morphological Analysis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PLA (Ingeo 3251D) | Biodegradable polymer matrix | Primary component in blend morphology studies [4] |

| PCL (Capa 6800) | Flexible, biodegradable polymer | Blend component to modify rigidity and toughness [4] |

| Fumed Silica (Aerosil200) | Nanoparticulate filler | Compatibilizer and morphology modifier in polymer blends [4] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) | Porosity modifier and compatibilizer | Induces phase separation and porous structure formation [7] |

| MPC Polymers | Bioinspired polymer with phosphorylcholine groups | Biomimetic surfaces for medical devices [7] |

| Thionoester-containing monomers | Degradable linkage incorporation | Enhancing PLA degradability through main-chain scission [7] |

| Reactive oligomers with imide groups | Compatibility enhancer | Controlling phase separation in epoxy blends [7] |

Polymer morphology, defined as the arrangement of molecules on a large scale, represents a critical determinant of material properties and performance across applications ranging from packaging to advanced medical devices. The interdisciplinary study of morphology encompasses techniques from molecular-level spectroscopy to macroscopic mechanical testing, with recent computational advances enabling more comprehensive structure-property predictions. Current research continues to expand our understanding of morphological control in sustainable polymers, nanocomposites, and functional materials, driving innovation in polymer science and technology. The quantitative relationship between processing conditions, resulting morphology, and final properties remains a fundamental focus of ongoing research, with significant implications for material design and development.

The physical and mechanical properties of polymeric materials are fundamentally governed by their internal microstructure and morphology. The arrangement of polymer chains into amorphous (disordered), crystalline (ordered), or semi-crystalline (mixed) phases directly determines critical performance characteristics including optical clarity, thermal stability, mechanical strength, and chemical resistance [8]. Understanding these structural classifications is essential for researchers and scientists across diverse fields, from drug delivery system development to advanced materials engineering, as it enables the rational design of polymers tailored for specific applications [9].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of amorphous, crystalline, and semi-crystalline polymer structures, detailing their defining characteristics, property relationships, and the advanced analytical techniques required for their characterization. The content is framed within the context of ongoing polymer morphology research, highlighting the critical structure-property relationships that guide material selection and development in scientific and industrial contexts.

Fundamental Structural Classifications

Amorphous Polymers

Amorphous polymers are characterized by a randomly ordered molecular structure lacking long-range arrangement, often described as having a "cooked spaghetti"-like morphology with entangled and disorganized chains [8] [10]. This structural disorder results in several distinctive properties. Unlike their crystalline counterparts, amorphous polymers do not possess a sharp melting point (T_m) but instead undergo a gradual softening process as temperature increases, transitioning through a glass transition temperature (T_g) where the material changes from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery one [8] [11].

The random molecular arrangement in amorphous polymers allows light to pass through with minimal scattering, typically resulting in transparent or translucent materials [8]. This optical property makes them invaluable for applications requiring visibility or light transmission, such as polycarbonate (PC) safety glass and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) acrylic replacements [12]. Their isotropic molecular structure leads to uniform shrinkage during cooling processes, providing better dimensional stability and reduced warping compared to semi-crystalline polymers [8] [10]. Additionally, the disordered chains can move more freely, granting amorphous polymers superior impact resistance and flexibility, though this comes at the expense of lower mechanical strength, stiffness, and wear resistance [12] [11].

Crystalline and Semi-Crystalline Polymers

Fully crystalline polymers are rare in practice due to the entangled nature of long polymer chains. Most ordered polymers are more accurately described as semi-crystalline, consisting of a mixture of organized crystalline regions and disordered amorphous areas [8]. These materials exhibit a highly ordered molecular structure where polymer chains are arranged in a tightly packed, organized manner with strong intermolecular forces [12] [10].

This structural organization imparts distinctive characteristics, most notably a sharp, well-defined melting point (T_m) where the material transitions rapidly from solid to liquid state [8] [11]. The crystalline regions scatter light efficiently, rendering semi-crystalline polymers typically opaque or translucent [8]. The tight molecular packing creates materials with superior mechanical strength, stiffness, and excellent resistance to wear and abrasion, making them suitable for structural applications and moving parts [12]. Furthermore, the organized structure provides enhanced chemical resistance as the dense packing impedes solvent penetration [8] [10].

A significant processing consideration is their anisotropic flow and shrinkage behavior, where shrinkage is greater in the direction transverse to flow than along it, potentially leading to dimensional instability in molded parts [8] [12].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Amorphous and Semi-Crystalline Polymers

| Property | Amorphous Polymers | Semi-Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, disordered [8] | Organized, ordered regions [8] |

| Melting Point | No sharp melting point; softens gradually [8] | Sharp, well-defined melting point (T_m) [8] |

| Optical Clarity | Often transparent or translucent [8] | Typically opaque or translucent [8] |

| Mechanical Properties | Good impact strength, lower stiffness [12] | High stiffness, strength, poor impact resistance [12] |

| Chemical Resistance | Moderate [8] | Excellent [8] [10] |

| Shrinkage & Dimensional Stability | Low, isotropic shrinkage; good stability [8] [10] | High, anisotropic shrinkage; can lead to warpage [8] [12] |

| Wear Resistance | Poor [10] | Excellent [12] |

Table 2: Characteristic Thermal Transitions of Common Polymers

| Polymer | Type | Glass Transition (T_g) |

Melting Point (T_m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate (PC) | Amorphous | ~150 °C [12] | None [11] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Amorphous | ~100 °C [8] | None |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Amorphous | ~85 °C [11] | None |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Semi-Crystalline | ~70-80 °C [12] | ~265 °C [12] |

| Polyamide (Nylon 66) | Semi-Crystalline | ~70 °C [11] | ~265 °C [11] |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Semi-Crystalline | ~-10 °C | ~160-175 °C [12] |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | Semi-Crystalline | ~143 °C [11] | ~343 °C [11] |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive polymer analysis requires a multifaceted approach, as no single technique can fully characterize complex polymer systems. Researchers typically employ complementary methodologies to obtain chemical, molecular, and bulk property data [9] [13].

Chromatographic and Spectroscopic Techniques

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) / Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) separates polymer molecules in solution according to their hydrodynamic volume or size, providing information on molecular weight distribution (MWD), a critical parameter influencing processability, mechanical strength, and morphological behavior [9]. The polymer sample is dissolved in a solvent and passed through a column packed with porous gel beads; smaller molecules penetrate the pores more readily and elute later, while larger molecules elute first [9].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy is indispensable for determining polymer microstructure, identifying functional groups, measuring copolymer composition, and investigating tacticity [9]. Advanced NMR methods like diffusion NMR can provide further insights into polymer dynamics and structure [9].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy identifies chemical functional groups and bonds within a polymer based on their characteristic vibrational energies, serving as a first-choice technique for classifying polymeric materials (e.g., polyamide, polyester) [9] [14]. Raman Spectroscopy offers complementary information to FTIR, particularly sensitive to symmetric vibrations and carbon backbone structures [9].

Mass Spectrometry (MS), especially when coupled with chromatographic systems like GC-MS or LC-MS, enables precise determination of molecular weight, identification of polymer additives, and analysis of residual monomers [9] [14]. Pyrolysis-GC-MS is particularly valuable for characterizing complex polymer systems and microplastics [15].

Thermal Analysis Techniques

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) measures heat flow into or out of a sample as a function of temperature or time, providing critical data on thermal transitions including glass transition temperature (T_g), melting point (T_m), crystallization temperature (T_c), and degree of crystallinity [9]. This information is vital for understanding a polymer's thermal stability and processing conditions.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) monitors changes in a sample's mass as it is heated, providing information on thermal decomposition temperatures, compositional analysis (polymer, filler, and reinforcement content), and thermal stability [9].

Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA) applies a periodic oscillating force to a sample to measure viscoelastic properties (storage modulus, loss modulus, and tan delta) as a function of temperature, time, or frequency. This technique is highly sensitive to T_g and other molecular relaxation processes [9].

Diagram Title: Polymer Characterization Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Determining Glass Transition and Melting Points via DSC

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of polymer sample into an aluminum crucible and seal hermetically. An empty crucible serves as reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using indium or other suitable standards.

- Temperature Program: Equilibrate at -50°C, then heat at a constant rate (typically 10°C/min) to a temperature above the expected melting or degradation point under nitrogen purge gas.

- Data Analysis: Identify the glass transition (

T_g) as a step change in heat capacity in the thermogram. Determine the melting point (T_m) from the endothermic peak temperature, and calculate crystallinity from the melting enthalpy relative to a 100% crystalline standard [9].

Protocol 2: Molecular Weight Distribution via SEC/GPC

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the polymer in an appropriate eluent (e.g., THF, DMF, chloroform) at a concentration of 1-2 mg/mL and filter through a 0.45 μm filter.

- System Setup: Equilibrate the SEC system with degassed eluent at a constant flow rate (typically 1.0 mL/min) through columns with appropriate pore sizes.

- Calibration: Create a calibration curve using narrow dispersity polystyrene or polymethyl methacrylate standards.

- Analysis: Inject the sample solution and detect using refractive index or light scattering detectors. Analyze the chromatogram to determine number-average molecular weight (

M_n), weight-average molecular weight (M_w), and polydispersity index (PDI) [9].

Protocol 3: Chemical Structure Identification via FTIR

- Sample Preparation: For solid polymers, use compression molding to create a thin film, or prepare a KBr pellet containing finely ground polymer. Liquid samples can be analyzed between NaCl plates.

- Background Scan: Collect a background spectrum of the atmosphere or pure KBr pellet.

- Data Acquisition: Place the sample in the FTIR spectrometer and collect spectra over a range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution.

- Interpretation: Identify characteristic absorption bands (e.g., C=O stretch at ~1700 cm⁻¹, C-H stretch at ~2900 cm⁻¹) and compare to reference spectra for polymer identification [9] [14].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy to avoid interference from proton signals [9] | Required for preparing polymer samples for NMR analysis; chemically inert |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Standards | Calibration of SEC/GPC systems for accurate molecular weight determination [9] | Narrow dispersity polymers (e.g., polystyrene, PMMA) with known molecular weights |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for FTIR sample preparation of solid polymers [14] | Infrared transparent; forms pellets under pressure for transmission FTIR |

| Inert Purge Gas (e.g., Nitrogen, 50 mL/min) | Creates inert atmosphere in thermal analysis instruments to prevent oxidative degradation [9] | High-purity grade; essential for TGA and DSC analyses at elevated temperatures |

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., THF, DMF, Chloroform) | Mobile phases for SEC/GPC; sample dissolution for various techniques [9] | HPLC grade; filtered and degassed prior to SEC/GPC use |

The classification of polymers into amorphous, crystalline, and semi-crystalline structures provides a fundamental framework for understanding and predicting material behavior. As this whitepaper has detailed, each structural class possesses distinct characteristics that directly influence optical, thermal, mechanical, and chemical properties. The rigorous characterization of these materials requires a comprehensive analytical approach, integrating data from chromatographic, spectroscopic, and thermal techniques to build a complete morphological picture.

Current research trends continue to advance this field, focusing on the development of biodegradable polymers, stimuli-responsive "smart" polymers for healthcare applications, and advanced composites with enhanced performance characteristics [16]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in polymer design and characterization is further accelerating the discovery of novel materials with tailored properties [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of polymer structure-property relationships remains essential for innovating next-generation materials that meet evolving technical and sustainability challenges across diverse scientific and industrial domains.

In polymer science, the relationship between structure and properties is foundational. The macroscopic behavior of a polymeric material—its mechanical strength, thermal stability, degradation profile, and functionality in applications like drug delivery—is dictated by its molecular-level architecture. Within the broader context of polymer structure and morphology research, three key intrinsic structural parameters serve as primary levers for controlling material performance: molecular weight, branching, and crosslinking. Understanding and characterizing these parameters is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for researchers and scientists designing advanced materials for targeted applications, including pharmaceutical development. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these parameters, detailing their specific effects, the experimental techniques for their characterization, and their critical roles in material design, supported by contemporary research data and methodologies.

Molecular Weight and Molecular Weight Distribution

Definition and Significance

Molecular weight (MW) and its distribution are fundamental characteristics of any polymer system. Unlike small molecules, polymers are polydisperse, consisting of chains with varying lengths. Therefore, the molecular weight distribution (MWD) becomes as critical as the average molecular weight itself. The MWD governs chain entanglement density, relaxation kinetics, and segmental mobility, which in turn dictate processability and final properties such as tensile strength, crystallinity, and thermal stability [17]. In synthetic polymer materials, which inherently exhibit MWD, polymer chains of various lengths coexist and synergistically create distinct crystalline structures and complex crystallization behaviors [17].

Impact on Material Properties

The effects of molecular weight are pervasive and multifaceted, influencing both kinetic and thermodynamic aspects of polymer behavior.

- Crystallization and Morphology: Molecular weight plays a critical role in polymer crystallization, governing processes from nucleation to growth. The breadth and shape of the MWD curve determine the proportion of high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) components, which exhibit distinct behaviors. HMW components have high entanglement density and slow relaxation kinetics, whereas LMW components possess high chain segment mobility [17]. This leads to molecular segregation during crystallization, where different MW fractions separate, resulting in complex crystalline textures. For instance, in poly(ethylene oxide) blends, this can result in composite structures with thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior surrounded by thicker lamellae at the periphery [17].

- Mechanical and Transport Properties: Molecular weight directly impacts key performance metrics. As demonstrated in studies on ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) membranes, increasing polymer MW significantly enhances mechanical strength and alters transport characteristics. The data in Table 1 illustrates these effects.

Table 1: Effect of UHMWPE Molecular Weight on Membrane Properties [18]

| Molecular Weight (×10⁶ g mol⁻¹) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Mean Pore Size (nm) | Permeance (L m⁻² h⁻¹ bar⁻¹) | Rejection of Blue Dextran (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 5.0 | 50 | 107 | 72 |

| 3.0 | 11.5 | 35 | 52 | 89 |

| 5.5 | 17.8 | 25 | 17 | 98 |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) / Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): This is the primary technique for determining molecular weight distribution. It separates polymer molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume as they pass through a column packed with a porous medium. Smaller molecules penetrate pores more deeply and elute later, while larger molecules elute first. The protocol involves: (1) dissolving the polymer sample in an appropriate solvent (e.g., THF) at a specific concentration; (2) filtering the solution to remove any particulate matter; (3) injecting the sample into the GPC system; (4) eluting the sample with the solvent at a controlled flow rate; and (5) detecting the eluted fractions using detectors such as refractive index (RI), light scattering (LS), and viscometry. Multi-detector setups provide absolute molecular weights, distribution (dispersity, ĐM), and information on branching density [19] [13].

- Viscosity Measurements: This method involves measuring the intrinsic viscosity of a polymer solution, which relates to the polymer's molecular weight through the Mark-Houwink-Sakurada equation. It provides a viscosity-average molecular weight (Mv) and offers insights into chain dimension and branching [19].

- Mass Spectrometry: Advanced mass spectrometry techniques, particularly MALDI-TOF (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight), are used to determine the absolute molecular weight of polymer samples and analyze end-group functionality, especially for polymers with lower dispersity [13].

Branching

Definition and Architectural Diversity

Branching refers to the presence of side chains extending from the main polymer backbone, fundamentally altering the architecture from a simple linear chain. The complexity of branching can range from short side chains to sophisticated miktoarm star polymers (also known as heteroarm star polymers), which are a class of star polymers with asymmetric branching where at least three chemically different strands originate from a shared core [20] [21]. These are denoted as A(x)B(y)C(_z), where A, B, and C represent different polymeric chains [20].

Impact on Material Properties

Branching profoundly influences a polymer's physical properties and its performance in applications, particularly drug delivery.

- Micellization and Drug Delivery: Miktoarm star polymers self-assemble in aqueous media into micelles with a distinct core-corona structure. Their branched architecture confers significant advantages over linear diblock copolymers, including very low critical micelle concentrations (CMCs), smaller micelle sizes, and a high capacity for drug encapsulation. Low CMCs are crucial for drug delivery as they ensure micellar stability upon immense dilution in the bloodstream, leading to longer circulation times [20]. The tunability of the arms allows for the incorporation of stimulus-responsive units (e.g., to pH or temperature) and targeting moieties.

- Crystallization: Branching disrupts chain packing and regular arrangement, thereby affecting crystallization kinetics and crystal perfection. The presence of branch points can reduce the overall degree of crystallinity, lower the melting temperature, and modify the crystal morphology, which in turn influences mechanical properties and degradation behavior.

Table 2: Properties of Select Miktoarm Star Polymer Formulations for Drug Delivery [20]

| Polymeric Arms | Architecture | Stimulus | Cargo | Loading Capacity (%) | Key Finding/Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG, PCL, P2VP | ABC | pH | Nile Red | N/A | Demonstrated multi-functionality and stimulus-responsiveness. |

| PEG, PLLA | AB₂ | - | Doxorubicin | N/A | High encapsulation efficiency (72%). |

| PEG, PCL | A₂B₂ | - | Ibuprofen | 7.3–20.3 | Tunable loading capacity based on architecture. |

| PCL, PEG | AB₃ | - | Curcumin | 11.4–13.3 | Effective loading of hydrophobic drugs. |

| PEG, PHis | AB₂ | pH | 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein | 0.92–1.42 µL mg⁻¹ | Controlled release triggered by pH change. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

- Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS): This technique is essential for characterizing branched polymers. While SEC separates by hydrodynamic volume, MALS detects the absolute molecular weight and root-mean-square radius. By comparing the molecular weight from MALS with the hydrodynamic volume from SEC, one can obtain the contraction factor (g'), which quantifies the degree of branching relative to a linear analog [19] [13].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR, particularly (^{1})H and (^{13})C NMR, is a powerful tool for identifying branching points and quantifying branch length and frequency by analyzing characteristic chemical shifts of branch points and end groups [19] [13].

- Melt Rheology: The viscoelastic behavior of branched polymers differs significantly from their linear counterparts. Analyzing the storage and loss moduli as a function of frequency provides insights into branching topology, as branched polymers typically exhibit higher elastic moduli at low frequencies due to long relaxation times.

Crosslinking

Definition and Classifications

Crosslinking involves the formation of permanent or reversible bonds between polymer chains, creating a three-dimensional network. This can be achieved through:

- Covalent Crosslinking: Strong, permanent bonds (e.g., in vulcanized rubber or epoxy resins).

- Physical Crosslinking: Reversible bonds based on supramolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, or ionic bonds [22]. These dynamic bonds can reassemble in response to stimuli, making them attractive for self-healing materials and controlled release.

Impact on Material Properties

The nature and density of crosslinks profoundly define a polymer network's mechanical profile.

- The Covalent Crosslinking Conflict: In covalently crosslinked networks, a fundamental conflict exists between modulus and fatigue threshold. As the number of monomers between two crosslinks ((n)) decreases, the modulus ((E)) increases ((E \sim n^{-1})), but the fatigue threshold ((G{th})), which resists crack growth under cyclic loads, decreases ((G{th} \sim n^{1/2})) [22].

- Physical Crosslinking and Hysteresis: Polymers crosslinked by physical bonds often suffer from large hysteresis. The physical bonds unzip when the network is stretched but do not rezip fast enough upon unloading, leading to significant energy loss and a difference between loading and unloading curves. While this can confer high toughness under monotonic stretch, it does not enhance the fatigue threshold and can lower the modulus over cyclic stretching [22].

- Advanced Network Design: Recent innovations have focused on reconciling these trade-offs. A 2025 study demonstrated a network of unusually long polymer chains crosslinked by domains of physical bonds (e.g., PEG and PAAc complexed via hydrogen bonds and aggregated into domains via hydrophobic interactions). This design achieves high modulus, high fatigue threshold, and low hysteresis simultaneously. Under moderate stress, the chains in the domains slip negligibly, making the domains function as hard particles, yielding high modulus and low hysteresis. Under high stress at a crack tip, the chains slip within the domains but do not pull out, enabling high tension transmission and a high fatigue threshold [22].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

- Swelling Experiments: The equilibrium degree of swelling in a good solvent is a direct measure of crosslink density. The Flory-Rehner equation can be applied to calculate the average molecular weight between crosslinks ((Mc)) from the swelling ratio. The protocol involves: (1) weighing a dry polymer network ((Wd)); (2) immersing it in solvent until equilibrium swelling is reached; (3) weighing the swollen network ((W_s)); and (4) calculating the mass or volume swelling ratio [22].

- Rheology to Determine Gel Point: For dynamically crosslinking systems, rheology can identify the gel point by monitoring the evolution of storage ((G')) and loss ((G'')) moduli during crosslinking. The point where (G') surpasses (G'') indicates the formation of a solid-like network.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy can identify and monitor the formation of specific crosslinking bonds, such as hydrogen bonds in PEG-PAAc complexes, by observing shifts in characteristic absorption bands (e.g., C=O and O-H stretches) [22].

- Mechanical Testing: Uniaxial tensile tests and cyclic loading tests are performed to measure modulus, strength, elongation at break, and hysteresis (the area between loading and unloading curves). Fatigue threshold is determined using pure-shear tensile specimens with a precut crack to measure the energy required for crack propagation under cyclic loading [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Hydrophilic, biocompatible polymer arm; forms complexes and physical domains. | Used in miktoarm stars (AB₂ architecture) and in hydrogels crosslinked with PAAc [20] [22]. |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Biodegradable, hydrophobic polymer arm for drug encapsulation. | Core-forming block in miktoarm star micelles (e.g., AB₂, ABC) [20]. |

| Poly(acrylic acid) (PAAc) | Forms physical crosslinks via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic aggregation. | Partner polymer with PEG to create high-strength, low-hysteresis hydrogels [22]. |

| Irgacure 2959 | Photoinitiator for radical polymerization. | UV-initiated polymerization of AAc monomers in the presence of PEG [22]. |

| Decalin | High-boiling-point solvent for controlled swelling and phase separation. | Swelling agent for the preparation of UHMWPE membranes [18]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | Solvents for NMR analysis. | Used for determining polymer structure, branching, and composition via NMR spectroscopy [19] [13]. |

Visualizing Relationships and Workflows

Polymer Architecture and Property Relationships

The following diagram summarizes the core relationships between the three key structural parameters and the resulting polymer properties.

Diagram 1: Influence of structural parameters on polymer properties.

Workflow for Fabricating a Physically Crosslinked Hydrogel

This diagram outlines a specific experimental protocol for creating a hydrogel crosslinked by domains of physical bonds, as described in recent literature [22].

Diagram 2: Fabrication of a physically crosslinked hydrogel.

Polymer morphology, the study of the arrangement and organization of polymer chains, is a foundational concept in materials science that governs the macroscopic behavior of polymeric materials [1]. This physical phenomenon describes the internal structure of polymers on a large scale, classifying them as amorphous, crystalline, or most commonly, semi-crystalline [1] [23]. The specific arrangement of polymer chains into ordered crystalline domains or disordered amorphous regions arises from a complex interplay of molecular structure, processing conditions, and thermal history [24]. Understanding this relationship between nanoscale organization and macroscopic properties is essential for researchers and scientists across diverse fields, from pharmaceutical development to advanced manufacturing, who seek to tailor material performance for specific applications.

In semi-crystalline polymers, which represent the most common morphological organization, crystalline regions (crystallites) form when polymer chains fold into ordered, three-dimensional lattices [24] [25]. These crystallites are dispersed within and interconnected by amorphous regions, where the chains adopt random, disordered configurations reminiscent of a tangled mass [24] [26]. This dual-phase architecture creates a composite material whose properties are determined by the relative proportion, arrangement, and interaction of these two distinct regions. The degree of crystallinity—the percentage of crystalline material within a polymer—typically ranges from 10% to 80% for most thermoplastics, though some specialized polymers can reach up to 95% crystallinity [25] [23]. Even in highly crystalline polymers, complete crystallinity is rarely achieved due to the structural constraints of long-chain molecules, making all crystalline polymers more accurately described as semi-crystalline [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Crystalline and Amorphous Polymer Regions

| Characteristic | Crystalline Regions | Amorphous Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Arrangement | Ordered, repeating 3D lattices; folded chain lamellae [24] [26] | Random, disordered chains; entangled mass [24] [26] |

| Chain Packing Density | High density [25] | Low density [25] |

| Thermal Transitions | Sharp melting point (Tm) [26] | Glass transition temperature (Tg) range [26] |

| Optical Properties | Opaque (scatter light) [25] | Transparent [25] |

| Representative Examples | Polyethylene, nylon, polypropylene [24] | Polystyrene, polycarbonate, PMMA [24] |

The balance between crystalline and amorphous regions constitutes what materials scientists term the crystallinity imperative—the governing principle that the morphological structure of a polymer dictates its mechanical, thermal, optical, and chemical properties. This relationship between structure and function enables the strategic design of materials with precisely tuned characteristics for applications ranging from drug delivery systems to structural aerospace components [25] [1]. Contemporary research continues to explore novel methods for controlling polymer morphology, including multi-temperature 3D printing from single formulations [27] and the development of advanced crystalline-amorphous nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties [28].

Structural Fundamentals and Molecular Organization

Crystalline Domains: Architecture and Formation

In crystalline polymer regions, molecular chains organize into highly ordered structures through a process of folding and stacking into lamellae [26]. These lamellar crystals represent the fundamental architectural units of crystalline domains, typically measuring between 10-50 nanometers in thickness [24]. The formation of these ordered structures occurs through a two-stage process of nucleation followed by crystal growth [24]. During nucleation, individual polymer chains or small bundles of chains initiate the formation of crystalline structures, either spontaneously within the polymer melt (homogeneous nucleation) or at interfaces or impurities (heterogeneous nucleation) [24]. Following nucleation, crystal growth proceeds through chain folding, where extended polymer segments align and fold back on themselves to form orderly stacks [24].

The resulting crystalline domains function as physical crosslinks within the polymer matrix, creating a reinforcing network that significantly enhances mechanical properties [25]. The close molecular packing within these crystalline regions results in higher density compared to amorphous regions, a property often exploited to determine crystallinity through density measurements [25]. This dense, ordered packing also creates a more tortuous path for penetrant molecules, conferring superior chemical resistance to semi-crystalline polymers by reducing permeability to aggressive chemicals [25].

Several molecular and processing factors influence the tendency of polymers to form crystalline structures [23]. These include:

- Regular and symmetrical linear chains that facilitate efficient packing

- Strong intermolecular forces between chains that stabilize crystalline formations

- Slow cooling rates from the melt that allow sufficient time for chain organization

- Low degree of polymerization that reduces chain entanglement

- Small and regular pendant groups that minimize steric hindrance to packing

In semi-crystalline polymers, these crystalline domains do not exist as isolated islands but are interconnected through tie molecules that traverse amorphous regions, creating a continuous network that distributes mechanical stress throughout the material [24]. This structural feature is critical for achieving optimal mechanical performance in semi-crystalline polymers.

Amorphous Regions: Structure and Role

Amorphous regions in polymers consist of randomly coiled and entangled chains that lack long-range order [26]. These disordered domains resemble a tangled mass of spaghetti, with chain positions following quasi-random distributions throughout the material [26]. Unlike their crystalline counterparts, amorphous regions demonstrate no sharp phase transition upon heating but instead undergo a gradual softening over a temperature range known as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [24] [26]. Below Tg, the amorphous regions exist in a rigid, glassy state where molecular motion is restricted to short-range vibrations [26]. Above Tg, these regions transition to a flexible, rubbery state where chain segments gain sufficient mobility for large-scale motion [26].

The amorphous phase plays several critical roles in polymer performance:

- Impact Modification: Amorphous regions contribute significantly to impact resistance and toughness by allowing energy dissipation through chain motion and segmental rotation [24].

- Solvent Interaction: The more open structure of amorphous regions makes them more susceptible to solvent penetration and plasticization compared to dense crystalline domains [25].

- Thermal Response: The glass transition temperature (Tg) primarily reflects molecular mobility within amorphous regions and dictates the upper use temperature for amorphous polymers [26].

In semi-crystalline polymers, amorphous regions provide flexibility and ductility to the material, while the crystalline domains impart strength and rigidity [24]. The proportion and distribution of these amorphous regions significantly influence mechanical behavior, with higher amorphous content generally correlating with increased elongation at break and impact resistance at the expense of reduced stiffness and strength [24].

Semi-Crystalline Architecture: The Hybrid System

Most thermoplastics exhibit a semi-crystalline structure that combines both crystalline and amorphous regions within a single material [23]. In this architectural hierarchy, lamellar crystals organize into larger superstructures called spherulites—spherical semicrystalline regions with radial symmetry that typically range from 1 to 100 micrometers in diameter [24]. Spherulitic growth begins from a central nucleus and expands outward, with lamellar crystals radiating from the center while being separated by amorphous regions [24]. The size and distribution of these spherulites significantly impact optical and mechanical properties, with larger spherulites often leading to increased brittleness [24].

Table 2: Property Comparison Between Semi-Crystalline and Amorphous Polymers

| Property | Semi-Crystalline Polymers | Amorphous Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Strength | High strength and stiffness [25] | Lower strength and stiffness [25] |

| Thermal Behavior | Well-defined melting point (Tm); maintains properties above Tg [25] [26] | Gradual softening over Tg range; no true melting point [25] [26] |

| Chemical Resistance | Good resistance due to dense packing [25] | Poor resistance [25] |

| Optical Clarity | Opaque (unless crystallites are smaller than light wavelength) [25] | Transparent [25] |

| Formability | Poor formability [25] | Good formability [25] |

| Fatigue & Wear Resistance | Good resistance [25] | Poor resistance [25] |

| Adhesion Properties | Difficult to bond with adhesives [25] | Bonds well using adhesives [25] |

The semi-crystalline architecture creates a natural composite material where crystalline domains act as reinforcing elements within an amorphous matrix [25]. This structure enables unique combinations of properties—for example, semi-crystalline polymers like PEEK maintain mechanical strength above their glass transition temperature due to the persistent crystalline reinforcement, while amorphous polymers would soften significantly [25]. The degree of crystallinity in these systems depends on both intrinsic factors (molecular structure, tacticity, chain flexibility) and processing parameters (cooling rate, annealing history) [24] [25].

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Experimental Protocols for Crystallinity Measurement

Accurate quantification of crystallinity is essential for understanding structure-property relationships in polymers. Several complementary techniques are employed, each with specific protocols, advantages, and limitations.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) measures thermal transitions associated with crystalline and amorphous regions by monitoring the heat flow into or out of a sample as it is subjected to a controlled temperature program [24] [29]. The standard experimental protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 3-10 mg of polymer and seal in a standard aluminum crucible. An empty reference pan is used for baseline correction.

- Temperature Program: Typically involves heating from room temperature to approximately 30°C above the expected melting point at a controlled rate (commonly 10°C/min under nitrogen atmosphere).

- Data Analysis: The melting endotherm is integrated to determine the heat of fusion (ΔHf). The percentage crystallinity is calculated by comparing this value to the theoretical heat of fusion for a 100% crystalline polymer (e.g., 290 J/g for polyethylene) [29].

DSC directly measures the glass transition temperature (Tg) of amorphous regions and the melting temperature (Tm) of crystalline domains, providing information about both phases in a single experiment [24] [29]. However, its limitations include potential overlap of thermal events and difficulty in measuring Tg in highly crystalline samples [29].

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) probes the atomic-scale order within crystalline regions by measuring diffraction patterns resulting from X-ray scattering [24] [29]. The standard protocol includes:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare powdered samples with consistent particle size (ideally <50 μm) to minimize preferred orientation effects. Flat plate specimens may be used for films or molded samples.

- Instrument Parameters: Typically use Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) with operating voltage of 40 kV and current of 40 mA. Data collection from 5° to 40° 2θ with step size of 0.02° and counting time of 1-2 seconds per step.

- Data Analysis: The crystalline fraction is determined by deconvoluting the diffraction pattern into crystalline peaks and an amorphous halo, then calculating the ratio of crystalline peak areas to the total scattered intensity [29].

PXRD is particularly valuable for identifying crystal structure, preferred orientation, and quantifying crystallinity in systems where DSC methods may be compromised by overlapping thermal events [29]. It remains relatively robust for determining crystalline-amorphous ratios in drug-polymer systems without other excipients [29].

Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (SSNMR) spectroscopy provides quantitative information about local molecular environments and dynamics through analysis of nuclear spin interactions in the solid state [29]. Key experimental considerations:

- Sample Preparation: Pack 50-100 mg of powdered material into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor. Particle size consistency improves spectral resolution.

- Acquisition Parameters: Use cross-polarization (CP) with magic-angle spinning (MAS) typically at 10-15 kHz for enhanced sensitivity and resolution. Specific pulse sequences (e.g., TOPP) may be employed to suppress background signals.

- Data Analysis: Crystallinity is quantified by deconvoluting spectra into crystalline and amorphous components based on chemical shift differences or relaxation behavior [29].

SSNMR excels at detecting subtle changes in crystal quality with different processing conditions and can explain failures of DSC methods in certain systems [29]. It provides both quantitative crystallinity information and insights into molecular-level structural variations [29].

Table 3: Comparison of Crystallinity Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Primary Measurement | Sample Requirements | Information Obtained | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat flow during thermal transitions [29] | 3-10 mg; powder or small section [29] | Tg, Tm, heat of fusion, crystallinity % [24] [29] | Limited at high drug loading; single polymorph systems [29] |

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | X-ray scattering intensity vs. angle [29] | Powder or flat plate; particle size <50 μm [29] | Crystal structure, preferred orientation, crystallinity % [24] [29] | Limited to systems without other excipients [29] |

| Solid-State NMR (SSNMR) | Nuclear spin interactions in solids [29] | 50-100 mg powder in MAS rotor [29] | Local molecular environments, crystal quality, crystallinity % [29] | Lower throughput; requires specialized expertise [29] |

Complementary Morphological Characterization

Beyond crystallinity quantification, several additional techniques provide crucial information about polymer morphology at different length scales:

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) probes the viscoelastic properties of polymers by applying oscillatory deformation while varying temperature [24]. This technique is exceptionally sensitive to glass transitions and secondary relaxations, often detecting transitions that may be missed by DSC. DMA provides quantitative information about storage modulus, loss modulus, and damping behavior, all of which are influenced by the crystalline-amorphous structure [24].

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) reveals surface topography and phase structures at high magnification, typically from nanometer to micrometer scale [24] [1]. For polymer characterization, samples often require coating with conductive materials (gold, carbon) to prevent charging. SEM is particularly valuable for examining spherulitic structures, phase separation in blends, and fracture surfaces.

Polarized Light Microscopy visualizes birefringence patterns in semi-crystalline polymers, enabling direct observation of spherulite size, distribution, and morphology [24]. This technique is nondestructive and requires thin film samples (typically 1-20 μm thickness) placed between cross-polarizers. The characteristic Maltese cross patterns observed in spherulites provide information about crystal orientation and perfection.

Material Properties and Performance Relationships

Mechanical Behavior: The Strength-Ductility Balance

The mechanical properties of polymers are profoundly influenced by their crystalline-amorphous architecture, particularly the balance between strength and ductility. Crystalline regions contribute primarily to strength, stiffness, and yield stress through their dense, ordered structure that efficiently bears applied loads and restricts chain mobility [24] [25]. In contrast, amorphous regions govern ductility, toughness, and impact resistance by allowing segmental motion and energy dissipation mechanisms [24]. This fundamental relationship creates a natural trade-off where increasing crystallinity typically enhances strength but reduces ductility [24].

Above the glass transition temperature (Tg), amorphous regions transition from a rigid, glassy state to a flexible, rubbery state, resulting in significant softening of amorphous polymers [26]. However, in semi-crystalline polymers, the crystalline domains maintain their structural integrity above Tg, acting as reinforcing physical crosslinks that preserve mechanical properties at elevated temperatures [25]. This unique characteristic enables the use of semi-crystalline polymers like PEEK in high-temperature applications where amorphous polymers would soften excessively [25].

The spatial arrangement of crystalline and amorphous regions significantly influences deformation mechanisms. In semi-crystalline polymers under mechanical stress, crystalline lamellae may undergo lamellar separation, chain slip, or crystal fragmentation processes, while amorphous regions experience chain alignment and orientation [24]. The tie molecules connecting crystalline domains through amorphous regions play a critical role in stress transfer between phases, enhancing overall mechanical integrity [24]. When these interphase connections are insufficient, amorphous regions between crystallites can become sites for void formation and crack initiation, leading to brittle failure [24].

Advanced materials design has exploited the crystalline-amorphous interface to achieve exceptional mechanical properties. Recent research on TiZr-based alloys with three-dimensional bicontinuous crystalline-amorphous nanoarchitectures (3D-BCANs) has demonstrated simultaneous high yield strength (~1.80 GPa) and large uniform ductility (~7.0%) [28]. In these nanocomposites, the amorphous phase imposes extra strain hardening to crystalline domains while crystalline domains prevent premature shear localization in amorphous phases, creating a synergetic deformation mechanism that overcomes traditional strength-ductility trade-offs [28].

Thermal and Chemical Properties

The thermal behavior of polymers is directly governed by their morphological structure. Crystalline regions melt at a specific melting temperature (Tm), reflecting the energy required to disrupt the orderly packed chains [26]. This transition is first-order and characterized by an abrupt change in properties. Amorphous regions, lacking long-range order, do not exhibit a true melting point but instead undergo a glass transition temperature (Tg), a second-order transition where the material changes from a glassy to rubbery state [26]. The breadth of the glass transition range reflects the distribution of molecular environments within the amorphous phase.

The degree of crystallinity significantly influences thermal expansion, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity. Crystalline regions typically exhibit lower thermal expansion coefficients and higher thermal conductivity compared to amorphous regions due to their ordered structure and stronger intermolecular interactions [25]. These differences can create internal stresses in processed parts with variable crystallinity, potentially leading to dimensional instability or warpage.

Chemical resistance represents another critical property differential between crystalline and amorphous regions. The dense packing in crystalline domains creates a tortuous path for penetrant molecules, resulting in lower permeability to liquids, gases, and chemical agents [25]. This property makes semi-crystalline polymers like PEEK particularly valuable for applications requiring resistance to aggressive chemicals, such as in the oil and gas industry for sealing systems and pump components [25]. Amorphous regions, with their more open structure, are more susceptible to solvent penetration, plasticization, and environmental stress cracking [25].

The relationship between morphology and chemical stability is particularly important in pharmaceutical applications, where the crystallinity of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) directly impacts dissolution behavior and shelf life [29]. Even small amounts of crystallinity in predominantly amorphous systems can significantly alter bioavailability and stability, necessitating precise characterization and control [29].

Advanced Applications and Research Frontiers

Research Reagent Solutions for Crystallinity Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Polymer Crystallinity Investigations

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Crystalline Monomers | Enable precise control over molecular alignment and crystallinity through phase behavior [27] | BPLC (smectic X phase monomer) [27] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Create polymer networks that fix morphological structure; influence crystallinity development [27] | Trifunctional thiol crosslinker [27] |

| Nucleating Agents | Promote heterogeneous nucleation; increase crystallization rate and control crystal size [24] | Organic (sorbitol derivatives); Inorganic (talc, silica) [24] |

| Photoinitiators | Initiate photopolymerization in vat-based 3D printing; enable spatial control of curing [27] | Radical photoinitiators (e.g., for acrylate systems) [27] |

| Metallic Glass Precursors | Create amorphous-crystalline nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties [28] | TiZrCuBe alloys for melt spinning [28] |

Emerging Technologies and Applications

Multi-Material 3D Printing represents a cutting-edge application of crystallinity control, where a single monomer formulation can produce either semi-crystalline or amorphous structures through simple adjustments in printing temperature and light intensity [27]. This approach utilizes liquid crystalline (LC) monomers that form highly stable LC phases with trifunctional thiol crosslinkers [27]. By printing at moderately high temperature (80°C), the liquid crystalline state becomes trapped in the network, creating stiff, opaque semi-crystalline regions, while printing at higher temperature (>95°C) produces largely amorphous polymer networks from the formulation's isotropic state [27]. This technology enables pixel-to-pixel resolution of material properties within single printed parts, with applications in shape memory devices, chemical data storage, and encryption systems [27].

Liquid Crystalline Elastomers (LCEs) constitute another advanced material class where crystallinity control enables unique functionality. Recent research has developed LCEs that can undergo multiple phase transitions with temperature changes, allowing complex, bidirectional shape deformability that resembles natural movements [30]. These materials transition through distinct phases as temperature changes, with molecules shifting and self-assembling into different configurations that enable twisting, tilting, shrinking, and expansion [30]. This multi-phase behavior creates potential applications in soft robotics, artificial muscles, controlled drug delivery systems, and biosensor devices [30].

Crystalline-Amorphous Nanoarchitectures represent a biomimetic approach to materials design, creating composite structures that overcome traditional property trade-offs. The development of three-dimensional bicontinuous crystalline-amorphous nanoarchitectures (3D-BCANs) has demonstrated exceptional strength-ductility combinations in TiZr-based alloys [28]. These materials feature micrometer-size equiaxed grains composed of nano-sized metastable crystalline phases and amorphous phases arranged in 3D-networked nano-bands [28]. Unlike conventional composites where phases are separated, the 3D interconnected structure in BCANs enforces strong interaction between crystalline and amorphous domains, preventing localized deformation and enabling synergistic strengthening mechanisms [28].

Pharmaceutical Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) leverage crystallinity control to enhance drug bioavailability. In these systems, active pharmaceutical ingredients are dispersed in amorphous polymer matrices to improve dissolution characteristics of poorly soluble compounds [29]. The quantitative measurement and control of crystallinity in ASDs is critical for stability and performance, with techniques like PXRD and SSNMR providing essential characterization data when traditional DSC methods prove insufficient [29]. The ability to accurately quantify crystallinity in these complex multi-component systems directly impacts drug development timelines and formulation success rates.

The crystallinity imperative—the governing principle that crystalline domains and amorphous regions dictate material behavior—remains a cornerstone of polymer science and engineering. The precise arrangement of polymer chains into ordered and disordered structures creates a architectural framework that determines mechanical, thermal, optical, and chemical properties. As characterization techniques advance, our ability to quantify and control this morphological organization continues to improve, enabling more sophisticated material design across diverse applications from pharmaceuticals to advanced manufacturing.

Contemporary research demonstrates that the traditional boundaries between crystalline and amorphous materials are becoming increasingly blurred through the development of multi-phase systems, nanoarchitectured composites, and spatially controlled morphologies. The emerging capabilities to manipulate crystallinity at multiple length scales—from molecular ordering to macroscopic domain structure—herald a new era of materials design where the crystalline-amorphous interface becomes a tunable parameter rather than a fixed characteristic. This paradigm shift promises to unlock new generations of polymers with previously unattainable property combinations, further reinforcing the fundamental importance of the crystallinity imperative in advanced materials research.

The performance of polymeric materials in biomedical applications is fundamentally governed by their structure at the molecular level. The dichotomy between crystalline and amorphous phases represents a critical design parameter for researchers and scientists developing materials for drug development, medical devices, and tissue engineering. Crystalline polymers exhibit regions where molecular chains are arranged in a highly ordered, repeating pattern, while amorphous polymers feature chains arranged in a random, haphazard manner [31] [11]. This structural distinction directly dictates a material's mechanical properties, degradation kinetics, bioavailability, and ultimately, its biocompatibility and functionality within a biological system [32]. Within the context of polymer structure and morphology research, understanding this relationship is paramount for the rational design of next-generation biomedical polymers that actively promote specific biological activities rather than merely coexisting with host tissues [32].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of how crystalline and amorphous polymers are utilized across the biomedical field. It synthesizes current research and development, presenting structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions to serve as a foundational resource for professionals engaged in the design and formulation of polymer-based biomedical products.

Fundamental Structural and Property Relationships

The atomic-level structure of a polymer—whether the chains are packed into ordered crystalline regions or exist in a disordered amorphous state—creates a cascade of effects that determine its macroscopic properties.

Crystalline polymers are characterized by a regular, repeating atomic structure that extends over large distances. This order results in higher density, greater mechanical strength, and superior chemical resistance due to tight molecular packing. A defining feature of crystalline polymers is their sharp melting point (Tm), as the ordered structure requires significant energy to break down simultaneously [31] [12] [11]. However, this rigidity often comes at the cost of reduced impact resistance.

Amorphous polymers, in contrast, lack long-range order. Their molecular chains are arranged randomly, akin to a bowl of cooked spaghetti. This structure typically results in materials that are more flexible, exhibit better impact resistance, and soften gradually over a temperature range rather than possessing a distinct melting point. This softening occurs at the glass transition temperature (Tg), below which the material is hard and glassy, and above which it becomes rubbery [12] [11]. This lack of order often allows for greater transparency.

Most thermoplastics are semi-crystalline, containing a mixture of both crystalline and amorphous regions. The ratio of these phases can be tailored during synthesis and processing to achieve a specific balance of properties [12].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Crystalline and Amorphous Polymers.

| Property | Crystalline Polymers | Amorphous Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Structure | Repeating, ordered structure [31] | Random, disordered chains [31] [12] |

| Melting Point | Sharp, distinct melting point (Tm) [11] |

No sharp melting point; softens over a range [12] |

| Density | Higher due to tight packing [31] [11] | Lower [31] |

| Mechanical Properties | Superior strength, stiffness, durability [12] [11] | Flexible, higher impact resistance [12] |

| Chemical Resistance | Excellent [11] | Generally more prone to chemical attack [12] |

| Optical Properties | Often opaque [11] | Often transparent [12] |

Material Selection for Specific Biomedical Applications

The selection of a crystalline or amorphous polymer is driven by the demanding requirements of the target biomedical application. The following section and table outline prominent polymers and their real-world uses.

Crystalline and Semi-Crystalline Polymers

- Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK): Known for its high strength, toughness, and radiolucency (translucency to X-rays), PEEK is a gold standard for orthopaedic implants such as spinal fusion cages and bone screws. Its high melting point (~343°C) and excellent chemical resistance ensure stability in the biological environment [32] [11].

- Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE): Valued for its exceptional impact resistance and high strength-to-weight ratio, UHMWPE is extensively used in load-bearing joint replacements, particularly as the articulating surface in knee and hip implants [32] [12] [11].

- Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and Poly(glycolic acid) (PGA): These biodegradable polyesters are workhorses in applications like resorbable sutures, bone screws, and scaffolds for tissue engineering. Their crystallinity can be tuned to control the degradation rate and mechanical integrity in vivo [32].

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE): With its renowned chemical inertness and low friction, PTFE (and its expanded form, Gore-Tex) is used in vascular grafts and ligament repair [32] [11].

Amorphous Polymers

- Polymeric Hydrogels: While often based on crosslinked networks, many hydrogels used in tissue engineering and drug delivery exhibit amorphous characteristics. Natural polymers like chitosan and hyaluronic acid form amorphous matrices that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), promoting cell adhesion and proliferation [32] [33].

- Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs): This is a key application for amorphous polymers in drug development. To enhance the solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs, the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is molecularly dispersed within an amorphous polymer matrix. While synthetic polymers like PVP are common, there is a growing shift towards natural polymers (e.g., chitosan, alginate) for ASDs due to their improved biocompatibility and sustainability [34].

- Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA): A rigid, transparent amorphous polymer used as a bone cement in orthopaedic surgery and in hard contact lenses [12].

- Liquid Crystalline Elastomers (LCEs): A special class of stimuli-responsive materials that combine the molecular order of liquid crystals with the elastic properties of amorphous elastomers. These "shape-changing" polymers can be actuated by heat or light, making them promising candidates for soft robotics, artificial muscles, and controlled drug delivery systems [30] [33].

Table 2: Biomedical Applications of Selected Crystalline and Amorphous Polymers.

| Polymer | Type | Key Properties | Specific Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|