Polymer Synthesis and Mechanisms: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamentals of polymer synthesis and polymerization mechanisms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Polymer Synthesis and Mechanisms: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamentals of polymer synthesis and polymerization mechanisms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the core principles of step-growth and chain-growth polymerization, delves into advanced methodological applications including controlled radical polymerization (CRP) techniques like ATRP and RAFT, and addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for process control. The content further covers essential validation and comparative analysis methods for characterizing polymer properties and performance. By synthesizing information across these four intents, this article serves as a foundational resource for the design and development of novel polymeric materials for targeted biomedical applications such as drug delivery and tissue engineering.

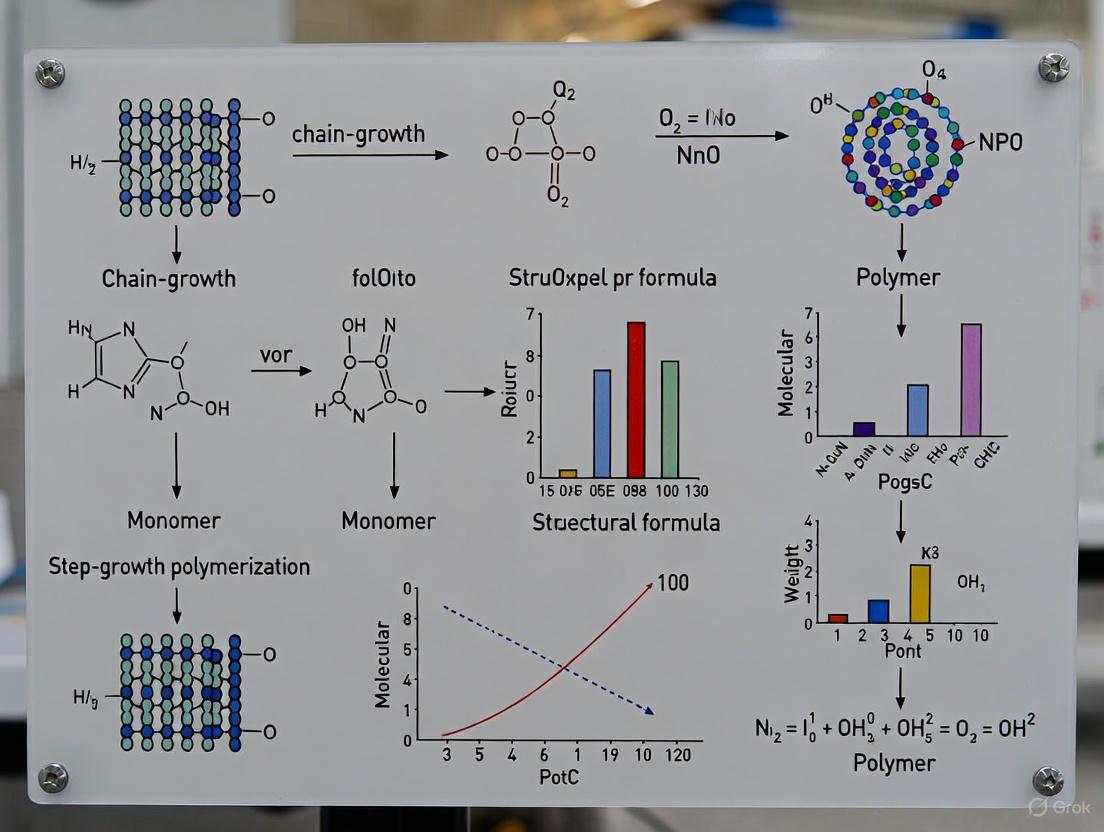

Core Principles of Polymerization: Understanding Step-Growth and Chain-Growth Mechanisms

Polymerization mechanisms represent the foundational processes in polymer creation, determining how monomeric subunits link to form long-chain macromolecules [1]. Within the broader context of polymer synthesis and mechanisms research, a precise understanding of these pathways is paramount for controlling polymer properties and designing novel materials with tailored characteristics for applications ranging from industrial plastics to advanced drug delivery systems [1] [2]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core polymerization mechanisms, classifying them into distinct pathways, summarizing key kinetic data, detailing experimental protocols, and visualizing the logical relationships that underpin modern polymer synthesis research. The ability to manipulate the polymerization process—controlling molecular weight, architecture, and final material properties—is a central thesis in the ongoing advancement of polymer science.

Core Polymerization Mechanisms

The synthesis of polymers from monomers is primarily governed by two mechanistic pathways: step-growth and chain-growth polymerization. These mechanisms differ fundamentally in their initiation, propagation, and the point at which high molecular weight polymers are formed [1] [2].

Step-Growth Polymerization

Step-growth polymerization involves reactions between bifunctional or multifunctional monomers, such as diols and diamines [1]. In this process, monomers first form dimers, trimers, and longer oligomers through the reaction of their functional groups. A critical characteristic of step-growth polymerization is that high molecular weight polymers only form at very high monomer conversions, typically exceeding 98% [1]. This mechanism is the basis for producing important condensation polymers like polyesters and polyamides (e.g., nylon 6,6), where the polymerization reaction is often accompanied by the loss of a small molecule, such as water or gas [2]. Polycondensation reactions tend to be slower than chain-growth processes and often require heating, which can sometimes result in lower molecular weight polymers [2].

Chain-Growth Polymerization

Chain-growth polymerization occurs with unsaturated monomers containing double or triple bonds, such as ethylene, styrene, and vinyl chloride [1]. This process is initiated by an active center, which can be a free radical, cation, anion, or coordination catalyst [2]. Unlike step-growth, monomers in a chain-growth mechanism add sequentially to the growing chain one at a time, and high molecular weight polymers form rapidly, even at low monomer conversions [1]. The mechanism consists of three key steps: initiation (creation of the active center), propagation (sequential monomer addition), and termination (deactivation of the active center) [2]. A significant subclass is living polymerization, which occurs without termination or chain transfer reactions, allowing for the synthesis of well-defined architectures like block copolymers [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Step-Growth and Chain-Growth Polymerization Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Step-Growth Polymerization | Chain-Growth Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Reaction between functional groups (e.g., -OH and -COOH) [1] | Addition of monomer to an active chain center (radical, ion) [1] |

| Monomer Type | Bifunctional or multifunctional monomers [1] | Unsaturated monomers (e.g., vinyl groups) [1] |

| High Molecular Weight Formation | At high conversion (>98%) [1] | At low conversion [1] |

| Polymer Examples | Polyesters, polyamides, polyurethanes [1] | Polyethylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride [1] |

| Kinetics | Slower polycondensation [2] | Fast sequential addition [2] |

Quantitative Kinetics and Copolymerization

The kinetic profile of a polymerization reaction is a critical factor in determining the structure and properties of the resulting polymer. Quantitative kinetic data enables researchers to predict copolymer structures and design experiments for specific architectural outcomes.

Free Radical Polymerization Kinetics

Free radical polymerization, a common chain-growth method, follows a distinct three-step sequence with characteristic kinetics [1]:

- Initiation: An initiator (e.g., peroxides, azo compounds) decomposes thermally or photolytically to generate free radicals, which then attack the first monomer molecule [1] [2].

- Propagation: The radical center at the chain end successively adds large numbers of monomer molecules, with each addition creating a new reactive center in a fast, chain-propelling reaction [2].

- Termination: The active center is neutralized, typically through combination (two growing chains coupling) or disproportionation (hydrogen transfer forming two dead chains) [1].

Copolymerization and Reactivity Ratios

Copolymerization, the polymerization of two or more different monomers, expands the versatility of polymeric materials. The distribution of monomers along the chain—the copolymer sequence—is governed by the relative reactivity of the monomers, expressed as reactivity ratios [3]. The different types of copolymerization reactions include [1]:

- Random Copolymerization: Monomers are incorporated in a statistically random sequence along the polymer chain.

- Alternating Copolymerization: Two monomers alternate regularly along the polymer backbone.

- Block Copolymerization: Two or more homopolymer segments are connected by covalent bonds, typically achieved via living polymerization.

- Graft Copolymerization: Branches of one polymer are attached to the backbone of another polymer.

Recent quantitative studies on Kumada Catalyst-Transfer Polymerisation (KCTP) of polythiophenes have highlighted the critical impact of monomer structure on reactivity. The following table summarizes key kinetic parameters for this system, demonstrating how structural similarity and steric hindrance influence reactivity [3].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for Kumada Catalyst-Transfer Copolymerization (KCTP) of 3-Hexylthiophene with Comonomers [3]

| Comonomer (with 3-Hexylthiophene) | Structural Similarity | Relative Reactivity | Predicted/Experimental Copolymer Structure in Batch |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Dodecylthiophene (3DDT) | High | Nearly equivalent | Random Copolymer |

| 3-(6-Bromo)hexylthiophene (3BrHT) | High | Nearly equivalent | Random Copolymer |

| 3-(2-Ethylhexyl)thiophene (3EHT) | Lower (branched side chain) | Less reactive | Gradient Copolymer |

| 3-(4-Octylphenyl)thiophene (3OPT) | Low (bulky phenyl group) | Homopolymerization fails in copolymerization | Chain Polymerization not maintained |

Experimental Protocols in Polymerization Research

Providing detailed, reproducible methodologies is essential for advancing research in polymer synthesis. The following protocols are adapted from recent literature.

Protocol: Homopolymerization Kinetics via NMR

Objective: To monitor the homopolymerization kinetics of a thiophene monomer (e.g., 3-Hexylthiophene) via ( ^1 \text{H} )-NMR spectroscopy [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Acid-washed and oven-dried 50 mL round bottom flask

- Schlenk line for inert (N(_2)) atmosphere operation

- Anhydrous Tetrahydrofuran (THF)

- 2-Bromo-3-hexyl-5-iodothiophene (3HT) monomer

- Isopropylmagnesium chloride (i-PrMgCl, 2.0 M in THF)

- Ni(dppp)Cl(_2) catalyst

- 1,3,5-Trimethoxybenzene (TMB) as an internal reference

- NMR tube and Deuterated chloroform (CDCl(_3))

Procedure:

- Monomer Preparation: Charge 3HT monomer (1 mmol, 0.373 g) and TMB (0.1 mmol, 16.8 mg) into the reaction flask under a N(_2) environment. Degas the mixture in vacuo for 30 minutes.

- Solvent Addition: Add anhydrous THF (10 mL) to dissolve the solid mixture.

- Monomer Activation: Cool the solution to 0°C and stir for 5 minutes. Add i-PrMgCl solution (0.95 mmol, 0.475 mL) dropwise. Allow the mixture to return to room temperature and react for one hour.

- Initiation: Take a time-zero aliquot (0.1 mL) before adding Ni(dppp)Cl(_2) catalyst (0.0167 mmol, 9.03 mg) directly to the mixture as a solid.

- Polymerization and Sampling: Allow the polymerization to proceed at room temperature. At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 min), extract aliquots (0.1 mL) from the reaction mixture.

- Quenching and Sample Preparation: Immediately quench each aliquot with 5 M HCl (1 mL). Extract the polymer with chloroform, dry the organic layer over anhydrous Na(2)SO(4), and remove the solvent in vacuo. Redissolve the residual polymer in d-CHCl(_3) for ( ^1 \text{H} )-NMR characterization.

- Data Analysis: Estimate the degree of polymerization (DP) by comparing the integrated signals of the polymer to the internal reference (TMB) using established methods [3].

Protocol: Copolymerization Kinetics via GC-MS

Objective: To determine the reactivity ratios in the copolymerization of 3HT and 3DDT via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Multiple 50 mL acid-washed, oven-dried round bottom flasks

- Anhydrous THF

- 3HT and comonomer (e.g., 3DDT)

- Isopropylmagnesium chloride (i-PrMgCl, 2.0 M in THF)

- Ni(dppp)Cl(_2) catalyst

- Tetradecane (TDC) as an internal standard for GC-MS

Procedure:

- Separate Monomer Solutions: Dissolve 3HT (1 mmol) and 3DDT (1 mmol) in separate flasks in anhydrous THF (10 mL each) after degassing.

- Monomer Mixture Preparation: In a separate flask, charge TDC (0.192 mmol, 50 μL). Combine different volume ratios of the 3HT and 3DDT stock solutions to this flask, ensuring the total volume is 2.5 mL.

- Activation and Initiation: Cool the combined monomer solution to 0°C, add i-PrMgCl (0.238 mmol, 0.119 mL), and stir for one hour at room temperature. Extract a time-zero aliquot. Initiate polymerization by adding Ni(dppp)Cl(_2) (0.00208 mmol, 1.13 mg).

- Short-Term Sampling: Extract aliquots at very short time intervals (e.g., 1 min and 2.5 min) to monitor initial monomer consumption.

- Quenching and Analysis: Quench the entire reaction after a short period (e.g., 3 min) with 5 M HCl. Dilute all aliquots in MeOH for GC-MS analysis to determine remaining monomer concentrations.

- Data Analysis: Calculate reactivity ratios by adapting the Mayo-Lewis equation to the kinetic data from the initial low-conversion time points [3].

Visualization of Polymerization Mechanisms and Workflows

Polymerization Mechanism Decision Logic

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for classifying the major polymerization mechanisms based on the reaction characteristics, helping researchers identify the operative pathway.

Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Studies

This diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for conducting homopolymerization and copolymerization kinetic studies, from monomer preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and their specific functions in polymerization reactions, particularly for the synthesis of conjugated polymers via KCTP and other mechanisms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kumada Catalyst-Transfer Polymerization (KCTP)

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Polymerization | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalyst (e.g., Ni(dppp)Cl₂) | Initiates and propagates the polymer chain via a catalyst-transfer mechanism, providing control over the polymerization [3]. | The bidentate phosphine ligand (dppp) is crucial for the chain-growth mechanism in KCTP. |

| Grignard Reagent (e.g., i-PrMgCl) | Activates the bromo/iodo-thiophene monomer by generating the organomagnesium species for transmetalation with the catalyst [3]. | Must be handled under strict anhydrous and oxygen-free conditions. |

| 2-Bromo-3-hexyl-5-iodothiophene (3HT) | The prototypical monomer for synthesizing the model conjugated polymer P3HT via KCTP [3]. | The halogen atoms (Br, I) are the leaving groups for oxidative addition to the catalyst. |

| Anhydrous Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Serves as the solvent for the polymerization, ensuring stability of the organometallic intermediates and the active catalyst [3]. | Essential to maintain reaction integrity; often purified using solvent drying systems. |

| Free Radical Initiators (e.g., Peroxides, Azo Compounds) | Thermally or photolytically decompose to generate free radicals that initiate radical chain-growth polymerization [1] [2]. | The half-life of the initiator at the reaction temperature determines the rate of initiation. |

| Ziegler-Natta Catalysts (e.g., TiCl₄ / AlEt₃) | Coordination catalysts that provide stereochemical control during the polymerization of α-olefins like propylene [2]. | Enable the production of stereoregular, unbranched, high molecular weight polyolefins. |

Step-growth polymerization represents a foundational class of chemical reactions that enable the synthesis of a wide array of commercially significant polymers, including polyesters, polyamides (nylons), polyurethanes, and polycarbonates. Unlike chain-growth processes, step-growth polymerization proceeds through the stepwise reaction of multifunctional monomers, where the growth of polymer chains occurs through reactions between monomers, oligomers, and polymers of any size [4]. This mechanism stands in stark contrast to chain-growth polymerization, where monomers only add to active chain ends [5].

The historical development of step-growth polymerization is marked by seminal contributions from pioneering scientists. Wallace Carothers, working at DuPont in the 1930s, developed both the theoretical framework and practical syntheses for numerous step-growth polymers, most notably the first synthetic polyesters and nylons [4]. Carothers developed mathematical equations to describe the behavior of step-growth polymerization systems, which remain known as the Carothers equations today [4]. Collaborating with physical chemist Paul Flory, they expanded these theories to encompass kinetics, stoichiometry, and molecular weight distribution [4]. Flory's subsequent work, culminating in his 1953 publication "Principles of Polymer Chemistry," formalized the distinction between step-growth and chain-growth polymerization mechanisms and provided a comprehensive statistical treatment of polymer molecular weight distributions [4] [6].

Mechanism and Characteristics of Step-Growth Polymerization

Fundamental Mechanism

Step-growth polymerization proceeds through the gradual buildup of polymer chains via reactions between functional groups on monomers or growing chains [7]. The process typically involves bifunctional monomers containing reactive end groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, amine, or isocyanate moieties [7]. These functional groups participate in nucleophilic addition or substitution reactions, forming covalent bonds that link monomer units together. A distinctive feature of many step-growth polymerizations is the elimination of small molecules like water, HCl, or alcohols as byproducts, classifying these specific reactions as condensation polymerizations [8] [5].

The mechanism progresses through clearly defined stages. Initially, monomers react with each other to form dimers. These dimers can then react with other monomers to form trimers, with other dimers to form tetramers, or with any other oligomeric species present in the reaction mixture [5]. This random reaction between species of any size continues throughout the polymerization process. Consequently, in the early stages of reaction, the mixture contains primarily unreacted monomers and low molecular weight oligomers, with high molecular weight polymers emerging only at high extents of conversion [4] [7].

Figure 1: The step-growth polymerization mechanism proceeds through random reactions between molecules of all sizes, with high molecular weight polymers only forming at high conversion.

Comparative Analysis with Chain-Growth Polymerization

Step-growth and chain-growth polymerization mechanisms differ fundamentally in their reaction pathways, monomer consumption profiles, and molecular weight development, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Step-Growth and Chain-Growth Polymerization

| Characteristic | Step-Growth Polymerization | Chain-Growth Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Profile | Growth throughout matrix by reactions between any molecular species [4] | Growth by addition of monomer only at one end or both ends of active chains [4] |

| Monomer Consumption | Rapid loss of monomer early in the reaction [4] | Some monomer remains even at long reaction times [4] |

| Reaction Steps | Similar steps repeated throughout reaction process [4] | Different steps operate at different stages (initiation, propagation, termination) [4] |

| Molecular Weight Increase | Average molecular weight increases slowly at low conversion and high extents of reaction are required to obtain high chain length [4] | Molar mass of backbone chain increases rapidly at early stage and remains approximately the same throughout the polymerization [4] |

| Chain End Activity | Ends remain active throughout reaction (no termination step) [4] [9] | Chains not active after termination [4] |

| Initiator Requirement | No initiator necessary [4] | Initiator required [4] |

It is crucial to recognize that the step-growth/chain-growth classification system is based on reaction mechanism and is distinct from the addition/condensation classification system, which is based on whether byproducts are formed [4] [5]. While many step-growth polymerizations are also condensation reactions (e.g., polyesterification), there are important exceptions. Polyurethane formation, for instance, proceeds via step-growth mechanism but without elimination of byproducts, making it an addition step-growth polymerization [4] [5].

Kinetics and Mathematical Modeling

Kinetic Models for Polyesterification

The kinetics of step-growth polymerization can be effectively illustrated using polyesterification as a model system. The reaction between carboxylic acid and alcohol groups to form ester linkages can proceed with or without an external catalyst, leading to distinct kinetic profiles.

For self-catalyzed polyesterification (where the carboxylic acid group serves as both reactant and catalyst), the reaction follows third-order kinetics [4]:

$$ \text{-d[COOH]/dt} = k[\text{COOH}]^2[\text{OH}] $$

If [COOH] = [OH] = C, this simplifies to:

$$ \text{-dC/dt} = kC^3 $$

Integration and substitution using the Carothers equation yields:

$$ \frac{1}{(1-p)^2} = 2kt[\text{COOH}]^2 + 1 = X_n^2 $$

For externally catalyzed polyesterification, the reaction follows second-order kinetics [4]:

$$ \text{-d[COOH]/dt} = k[\text{COOH}][\text{OH}] $$

With [COOH] = [OH] = C, this becomes:

$$ \text{-dC/dt} = kC^2 $$

Integration gives:

$$ \frac{1}{1-p} = 1 + [\text{COOH}]kt = X_n $$

These kinetic expressions reveal a crucial practical implication: for an externally catalyzed system, the number average degree of polymerization (Xₙ) grows proportionally with time, whereas for a self-catalyzed system, Xₙ grows only with the square root of time [4]. This explains why industrial processes typically employ catalysts to achieve high molecular weights in practical timeframes.

Carothers Equation and Molecular Weight Control

The Carothers equation provides a fundamental relationship between the extent of reaction and the degree of polymerization in step-growth systems [7]. For a stoichiometrically balanced system of bifunctional monomers:

$$ X_n = \frac{1}{1-p} $$

where p is the extent of reaction (the fraction of functional groups that have reacted) and Xₙ is the number average degree of polymerization [10]. This equation predicts that very high conversions are necessary to achieve high molecular weights. For example, to reach Xₙ = 100, a conversion of 99% (p = 0.99) is required [10].

In practice, molecular weight is often controlled through intentional stoichiometric imbalance or the addition of monofunctional chain terminators [7]. For a non-stoichiometric system with a molar ratio r = Nₐ/Nᴃ < 1 (where Nₐ and Nᴃ represent the number of functional groups A and B, respectively), the Carothers equation becomes:

$$ X_n = \frac{1 + r}{1 + r - 2rp} $$

For quantitative reactions (p → 1), this simplifies to:

$$ X_n \approx \frac{1 + r}{1 - r} $$

Table 2: Relationship Between Stoichiometric Imbalance and Degree of Polymerization at Complete Conversion (p = 1)

| Molar Ratio (r) | Degree of Polymerization (Xₙ) |

|---|---|

| 1.000 | ∞ |

| 0.999 | 2000 |

| 0.990 | 200 |

| 0.950 | 40 |

| 0.900 | 20 |

These relationships enable precise control over the final molecular weight of the polymer, which is crucial for tailoring material properties to specific applications [7].

Molecular Weight Distribution

The molecular weight distribution in linear step-growth polymers was first derived by Flory using a statistical approach. For a system at extent of reaction p, the mole fraction of x-mers (chains containing x monomer units) is given by:

$$ P(x) = p^{x-1}(1-p) $$

This is known as the Flory distribution or the "most probable distribution" [10]. The number fraction distribution and weight fraction distribution provide insights into the polydispersity of the resulting polymer. The weight fraction distribution is given by:

$$ W_x = xp^{x-1}(1-p)^2 $$

For step-growth polymers, the polydispersity index (PDI = Mw/Mn) approaches 2 as the reaction approaches completion (p → 1) [10]. This characteristic broad molecular weight distribution has important implications for the processing and mechanical properties of the resulting materials.

Important Classes of Step-Growth Polymers

Polyesters

Polyesters are synthesized by the reaction of dicarboxylic acids (or derivatives) with diols, forming ester linkages in the polymer backbone [8] [7]. A commercially paramount example is poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), produced from terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol, which exhibits excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and barrier properties [7]. PET finds extensive application in fibers for textiles, packaging materials (especially beverage bottles), and engineering plastics for automotive and electronic components [7].

The polyesterification reaction typically requires high temperatures and catalysts to achieve high molecular weights. Metal alkoxides (e.g., titanium alkoxides) and antimony compounds are commonly employed as catalysts in industrial processes [7]. The properties of polyesters can be tuned through monomer selection; aromatic dicarboxylic acids like terephthalic acid impart rigidity and higher melting points, while aliphatic diols like ethylene glycol provide chain flexibility [8].

Polyamides (Nylons)

Polyamides, commonly known as nylons, are formed by the reaction of diamines with dicarboxylic acids (or derivatives) or through the self-condensation of amino acids [8]. These polymers feature amide linkages (-CONH-) in their backbone, which facilitate strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding, resulting in high strength, wear resistance, and good thermal properties [8] [7].

Nylon 6,6 (synthesized from hexamethylenediamine and adipic acid) and Nylon 6 (from ε-caprolactam) represent the most commercially significant polyamides [8]. Applications span fibers for textiles and industrial uses (ropes, tire cords), engineering plastics for automotive and consumer goods, and films for food packaging [7]. The "nylon rope trick" demonstration showcases the rapid formation of polyamide from interfacial polymerization between adipoyl chloride and hexamethylenediamine [10].

Polyurethanes and Other Step-Growth Polymers

Polyurethanes are produced by the reaction of diisocyanates with diols without the elimination of small molecules, making them addition step-growth polymers [4] [5]. This versatility enables the production of materials with vastly different properties, including flexible and rigid foams for insulation and cushioning, elastomers for automotive parts and footwear, and coatings and adhesives for various industries [7].

Other important classes of step-growth polymers include:

- Polycarbonates: Transparent, high-impact materials with good thermal and oxidative stability, used in engineering applications, automotive components, and medical devices [4].

- Polyureas: Feature high glass transition temperatures and good resistance to greases, oils, and solvents, finding application in truck bed liners and bridge coatings [4].

- Epoxy resins: Formed through step-growth mechanisms, used as adhesives and in composite materials [8].

Table 3: Characteristic Properties of Selected Step-Growth Polymers

| Polymer | Key Monomers | Typical Applications | Notable Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene terephthalate) | Terephthalic acid, Ethylene glycol | Fibers, packaging bottles, films | Good mechanical properties to ~175°C, good solvent resistance [4] |

| Nylon 6,6 | Hexamethylenediamine, Adipic acid | Fibers, engineering plastics, films | Good balance of strength, elasticity, abrasion resistance [4] |

| Polycarbonate | Bisphenol A, Phosgene | Transparent panels, electronic components | Brilliant transparency, glass-like rigidity, self-extinguishing [4] |

| Polyurethane | Diisocyanate, Diol | Foams, elastomers, coatings | Good abrasion resistance, hardness, elasticity [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Synthesis Procedure for Polyesterification

A typical laboratory-scale synthesis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) illustrates core principles and techniques common to many step-growth polymerizations [11] [7].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Terephthalic acid (or dimethyl terephthalate) and ethylene glycol in stoichiometric balance

- Catalyst: Metal acetate (e.g., antimony trioxide, titanium alkoxide) at 0.01-0.05 mol%

- Nitrogen purge system for inert atmosphere

- Reactor vessel with mechanical stirring, temperature control, and distillation apparatus

- Vacuum system for later stages of polymerization

Procedure:

- Esterification/Transesterification Stage: Charge monomers and catalyst to the reactor under nitrogen atmosphere. Heat gradually to 150-200°C while stirring. For dicarboxylic acids, water distills off; for dimethyl ester derivatives, methanol is eliminated. Continue until theoretical amount of condensate is collected.

- Polycondensation Stage: Increase temperature to 250-280°C. Apply gradually increasing vacuum (final pressure < 1 mmHg) to remove ethylene glycol condensate and drive the equilibrium toward higher molecular weight.

- Termination: When desired molecular weight is achieved (often monitored by melt viscosity or stirrer torque), apply carbon dioxide purge and discharge the polymer under pressure.

Critical Parameters:

- Precise stoichiometric balance is essential for high molecular weight

- Oxygen exclusion prevents oxidative degradation at high temperatures

- Efficient removal of condensate is crucial for achieving high conversion

- Temperature control balances reaction rate against thermal degradation

Figure 2: A two-stage experimental workflow for polyester synthesis, showing temperature and pressure conditions critical for achieving high molecular weight.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Step-Growth Polymerization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bifunctional Monomers | Polymer building blocks | Diacids (terephthalic, adipic), diols (ethylene glycol, BPA), diamines (hexamethylenediamine) [7] |

| Multifunctional Monomers | Introduce branching/crosslinking | Glycerol, trimethylolpropane (functionality >2) [7] |

| Catalysts | Accelerate reaction rate | Metal salts (titanium alkoxides for polyesters), acids (p-toluenesulfonic acid for polyamides) [7] |

| Solvents | Control viscosity, heat transfer | High-boiling solvents (diphenyl ether) for solution polymerization; often melt polymerization preferred [7] |

| Stabilizers | Prevent degradation | Antioxidants (phosphites), thermal stabilizers during high-temperature processing [7] |

| Chain Terminators | Control molecular weight | Monofunctional acids, alcohols, or amines; precise control of end groups [7] |

Step-growth polymerization remains a vital synthetic methodology for producing polymers with diverse structures and properties. The fundamental understanding of its mechanisms and kinetics, pioneered by Carothers and Flory, continues to provide the foundation for ongoing research and development. Current trends in the field focus on enhancing sustainability through the use of bio-derived monomers, developing novel reaction pathways such as click chemistry for step-growth polymerization, and creating advanced materials with tailored architectures and functionalities [9].

The integration of step-growth polymerization with other polymerization mechanisms in multi-mechanism approaches represents another frontier in polymer science [12]. These strategies, including one-pot sequential and simultaneous polymerizations, enable the synthesis of complex macromolecular structures with precise control over composition and functionality [12]. As research continues to advance the traditional families of step-growth polymers with novel synthetic strategies and unique processing scenarios, these materials will continue to enable future technologies across biomedical, electronic, and sustainable applications.

Chain-growth polymerization is a fundamental class of polymerization mechanisms central to modern polymer synthesis, wherein the growth of a polymer chain occurs exclusively at its reactive chain end [13]. This process enables the formation of high-molecular-weight polymers early in the reaction, distinguishing it from step-growth mechanisms. The chain-growth paradigm encompasses three principal pathways—radical, cationic, and anionic—each characterized by distinct reactive intermediates and mechanistic profiles [13]. Within the broader context of polymer synthesis research, understanding these pathways provides the foundational knowledge necessary to design polymers with precise architectural and property specifications. This technical guide delineates the core mechanisms, kinetics, and experimental methodologies governing these polymerization pathways, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting and implementing appropriate synthetic strategies.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Chain-Growth Polymerization

Chain-growth polymerization proceeds through a sequence of elementary reactions: initiation, propagation, and termination [13] [14]. The process commences when an initiator species generates an active center, which adds to a monomer molecule, creating a new active site. This propagation phase involves the rapid, successive addition of monomer units to the active chain end, resulting in polymer chain elongation [14]. The specific nature of the active center—whether a radical, carbocation, or carbanion—defines the polymerization type and dictates the requisite monomer structures, initiators, and reaction conditions [13].

A critical distinction among the pathways lies in their termination mechanisms. In radical polymerization, termination is typically bimolecular, occurring through radical combination or disproportionation [14]. In contrast, ionic polymerizations (cationic and anionic) often involve chain transfer as a primary termination pathway or, in the case of living anionic systems, may lack formal termination altogether [15]. The reactivity of the propagating species directly influences the polymerization kinetics, with cationic systems generally exhibiting the highest propagation rates, followed by anionic and radical systems [16]. The following table provides a comparative overview of the three primary chain-growth polymerization mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Chain-Growth Polymerization Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Radical Polymerization | Cationic Polymerization | Anionic Polymerization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Center | Free Radical [13] | Carbocation (Carbenium ion) [13] [17] | Carbanion [13] [18] |

| Typical Initiators | Peroxides, Azo compounds [13] [14] | Lewis Acids (e.g., AlCl₃, BF₃) with co-initiators (e.g., H₂O), strong protic acids [13] [17] [19] | Alkyllithium compounds (e.g., BuLi), alkali metals, metal amides [13] [15] |

| Suitable Monomers | Ethylene, styrene, vinyl chloride, (meth)acrylates [13] [14] | Isobutylene, vinyl ethers, styrene, monomers with electron-donating groups [13] [17] [19] | Styrene, dienes, (meth)acrylates, monomers with electron-withdrawing groups [13] [18] [15] |

| Termination Mechanism | Combination, Disproportionation [14] | Combination with counterion, proton transfer to monomer [17] [19] | Reaction with electrophile (intentional or impurity); often none in living systems [15] |

| Susceptibility to Impurities | Low (tolerant to water) [16] | Very High [17] | Very High [15] |

| Typical Reaction Time | ~1 hour [16] | ~1 second [16] | ~1 minute [16] |

Radical Polymerization

Mechanism and Kinetics

Radical polymerization employs a neutral free radical as the active propagating species [14]. The mechanism unfolds in distinct stages. Initiation involves two steps: first, the homolytic decomposition of an initiator molecule (e.g., a peroxide or azo compound) to generate primary radicals; second, the addition of these primary radicals to a monomer molecule to form the first propagating radical [14] [16]. Propagation consists of the sequential addition of thousands of monomer molecules to the propagating radical, rapidly building the polymer chain [14]. The process concludes with Termination, which occurs primarily through bimolecular reactions between two propagating radicals, either by combination (coupling) or disproportionation (hydrogen atom transfer) [14] [16]. A competing process, Chain Transfer, involves the transfer of the radical active center from the growing polymer chain to another molecule (e.g., solvent, monomer, or a specialized chain-transfer agent), terminating the original chain but potentially initiating a new one [14].

The kinetics of radical polymerization are complex due to the bimolecular termination step. The rate of polymerization is proportional to the monomer concentration and the square root of the initiator concentration [14]. The number-average degree of polymerization (DP̄ₙ) similarly depends on these concentrations and is inversely affected by the efficiency of the initiator and the rate of chain transfer reactions [14].

Experimental Protocol: Typical Radical Polymerization of Styrene

Objective: To synthesize polystyrene via free radical polymerization using azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) as the thermal initiator.

Materials:

- Monomer: Styrene (inhibitor removed by passing through a column of basic alumina)

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN)

- Solvent: Toluene (anhydrous, optional for bulk polymerization)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a Schlenk flask or a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, charge styrene (10.0 g, 96.1 mmol) and toluene (10 mL, if performing solution polymerization). Add AIBN (0.164 g, 1.0 mmol, ~1 mol% relative to monomer). Seal the flask with a rubber septum.

- Deoxygenation: Sparge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 20-30 minutes to eliminate dissolved oxygen, a potent radical inhibitor [14].

- Polymerization: Submerge the flask in a thermostated oil bath pre-heated to 60-70 °C with continuous stirring. The reaction will typically proceed for 6-12 hours.

- Termination & Work-up: After the reaction time, remove the flask from the oil bath and cool it to room temperature. Precipitate the polymer by slowly dripping the reaction mixture into a large excess of vigorously stirred methanol (≈200 mL). Filter the resulting white, fibrous precipitate.

- Purification: Re-dissolve the crude polymer in a minimal amount of toluene and re-precipitate into methanol. Filter the purified polymer and dry it under vacuum at 40-50 °C until constant weight is achieved.

Characterization: The molecular weight and dispersity (Đ) of the resulting polystyrene can be determined by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC). The structure can be confirmed by ¹H NMR spectroscopy.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Radical Polymerization

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Initiators | Generates primary radicals upon heating to initiate chain growth [14] [16]. | AIBN: Decomposes around 60-70°C; yields neutral cyanopropyl radicals. Benzoyl Peroxide (BPO): Common peroxide initiator. |

| Radical Inhibitors | Scavenges stray radicals to prevent uncontrolled polymerization during monomer storage/purification [16]. | Hydroquinone, BHT (Butylated Hydroxytoluene): Added in trace amounts (10-500 ppm) to monomers for stabilization. |

| Chain Transfer Agents (CTAs) | Controls molecular weight and can introduce end-group functionality by terminating a growing chain and initiating a new one [14]. | Thiols (e.g., Dodecanethiol), Halocarbons (e.g., CCl₄): RAFT Agents: Specialized CTAs for Reversible Addition-Fragmentation chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization, enabling living character [16]. |

Cationic Polymerization

Mechanism and Kinetics

Cationic polymerization employs a carbocation (carbenium ion) as the active propagating species [17] [19]. This mechanism demands monomers with electron-donating substituents that can stabilize the positive charge on the carbocation intermediate, such as isobutylene, alkyl vinyl ethers, and styrene [13] [19]. Initiation typically requires a strong electrophilic initiator. While strong protic acids can be used, Lewis acids (e.g., AlCl₃, BF₃, TiCl₄) in combination with a co-initiator (e.g., water, known as a "proton source") are far more common and effective [17] [19]. The initiator-coinitiator complex generates the initial carbocation. Propagation proceeds via the electrophilic attack of the carbocationic chain end on the π-bond of the monomer [17]. The Termination mechanism in cationic polymerization is distinct from radical processes; it often occurs unimolecularly via rearrangement or fragmentation of the growing ion pair, rather than through bimolecular collision [19]. Chain Transfer is a dominant chain-breaking event, frequently involving proton transfer back to the monomer, which terminates the growing chain but generates a new initiator capable of starting a new chain [17] [19].

The kinetics of cationic polymerization are exceptionally fast and are highly sensitive to reaction conditions. The rate of propagation is strongly influenced by the polarity of the solvent and the nature of the counterion, as these factors control the equilibrium between less reactive tight ion pairs and more reactive solvent-separated or free ions [19]. Low temperatures (e.g., -70 to -100 °C) are often employed to suppress transfer and termination reactions, thereby favoring the formation of high molecular weight polymers [19].

Experimental Protocol: Cationic Polymerization of Isobutylene

Objective: To synthesize polyisobutylene using a BF₃/H₂O initiating system at low temperature.

Materials:

- Monomer: Isobutylene (condensed)

- Initiator/Co-initiator: Boron trifluoride (BF₃) gas, Water (H₂O)

- Solvent: Hexane/Methyl Chloride mixture (dried and deoxygenated)

- Quenching Agent: Pre-chilled methanol

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Assemble a reactor (e.g., a multi-necked flask) equipped with a mechanical stirrer, thermocouple, and gas inlet/outlet. Evacuate the flask and flush with dry nitrogen. Cool the entire reactor to the desired reaction temperature (e.g., -70 °C) using a dry ice/isopropanol bath.

- Charging: Under a nitrogen atmosphere, add the dry solvent mixture. Introduce a precisely measured, trace amount of water (the co-initiator) into the solvent.

- Monomer Addition: Condense the required amount of isobutylene into the cooled reactor.

- Initiation: Begin vigorous stirring and bubble a slow, controlled stream of BF₃ gas through the reaction mixture. The polymerization is immediate and highly exothermic.

- Polymerization: Maintain the temperature at -70 °C for 15-60 minutes while the reaction proceeds.

- Termination: Quench the polymerization by adding a large volume of cold methanol. The polymer will precipitate.

- Work-up: Isolate the polymer by filtration or decantation. Wash the polymer thoroughly with methanol and dry under vacuum until constant weight.

Characterization: The molecular weight can be determined by GPC, and the microstructure (e.g., exo-olefin end groups from chain transfer) can be analyzed by ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectroscopy.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cationic Polymerization

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lewis Acids | Acts as a co-initiator; activates a proton source to generate the initiating carbocation [17] [19]. | AlCl₃, BF₃, TiCl₄: Highly moisture-sensitive. Require scrupulously anhydrous conditions except for the deliberate co-initiator. |

| Co-initiators | Provides the proton (H⁺) that initiates the chain growth [19]. | Water (H₂O): Used in trace amounts. Protic Acids (e.g., triflic acid): Can also be used directly. |

| Solvents | Medium that influences the ion pair equilibrium and propagation rate [19]. | Halogenated Solvents (e.g., CH₂Cl₂), Hexane: Polar solvents like CH₂Cl₂ favor separated ion pairs, increasing rate and molecular weight. |

Anionic Polymerization

Mechanism and Kinetics

Anionic polymerization utilizes a carbanion as the active propagating species [18] [15]. This mechanism is favored for monomers bearing electron-withdrawing substituents (e.g., nitrile, ester, phenyl groups) that stabilize the negative charge of the carbanion, such as styrene, 1,3-dienes, and (meth)acrylates [13] [15]. Initiation involves the nucleophilic attack of an anionic initiator on the monomer. The strength of the initiator (e.g., n-butyllithium, sodium naphthalenide) must be matched to the monomer's reactivity [15]. Propagation proceeds through the successive nucleophilic addition of the carbanionic chain end to monomer molecules [18].

A defining feature of anionic polymerization is its potential for a Living character. Under ideal conditions (i.e., the absence of terminating agents like water, oxygen, or CO₂), the chain ends remain active indefinitely after the monomer is consumed [15]. This allows for the synthesis of polymers with precisely controlled molecular weights, narrow molecular weight distributions (approaching a Poisson distribution), and complex architectures like block copolymers through sequential monomer addition [15]. Termination is not an inherent step in the mechanism but occurs only upon intentional introduction of a terminating agent (e.g., an electrophile like water or alcohol) or through spontaneous side reactions over time [15].

The kinetics of living anionic polymerization are often first-order with respect to monomer concentration, and the number-average degree of polymerization (DP̄ₙ) is simply given by the mole ratio of monomer consumed to initiator used [15].

Experimental Protocol: Living Anionic Polymerization of Styrene

Objective: To synthesize polystyrene with controlled molecular weight and narrow dispersity using n-butyllithium as the initiator.

Materials:

- Monomer: Styrene (purified and distilled from CaH₂)

- Initiator: n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi, solution in hexanes, accurately titrated)

- Solvent: Cyclohexane or Benzene (highly purified, dried over sodium/benzophenone ketyl)

- Terminating Agent: Degassed methanol

Procedure:

- Apparatus Preparation: Use a glass reactor system (e.g., a Schlenk line or a sealed reactor under high-vacuum techniques) to ensure absolute exclusion of air and moisture. All glassware must be flamedried under vacuum.

- Solvent/Monomer Transfer: Under an inert atmosphere, transfer the dry solvent and purified styrene into the reactor.

- Initiator Addition: With efficient stirring, add the titrated n-BuLi solution via syringe. An immediate and persistent color change (often orange/red due to the styryl anion) indicates the formation of the living polymer.

- Polymerization: Allow the reaction to proceed at room temperature. The polymerization is typically complete within minutes to an hour.

- Sampling (Optional): A small aliquot can be withdrawn under inert conditions to determine the molecular weight before termination.

- Termination/End-functionalization: Introduce a large excess of degassed methanol to quench the living carbanions, yielding dead polymer. Alternatively, to introduce a specific end-group, add a terminal electrophile (e.g., CO₂ for a carboxylic acid end group, ethylene oxide for a hydroxyl end group).

- Work-up: Precipitate the polymer into methanol, isolate by filtration, and dry under vacuum.

Characterization: GPC will show a narrow molecular weight distribution (Đ ~ 1.01-1.05). ¹H NMR can be used to confirm the structure and, in some cases, the end-group functionality.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Anionic Polymerization

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Organolithium Initiators | Highly nucleophilic initiator for less reactive monomers like styrene and dienes [15]. | n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi): Must be accurately titrated before use. |

| Electron Transfer Initiators | Generates a radical anion that initiates polymerization for certain monomers [15]. | Sodium Naphthalenide: Forms a dark green solution; produces a difunctional living polymer. |

| Solvents | Aprotic and non-polar solvents are essential to prevent chain transfer or termination [15]. | Benzene, Cyclohexane, Tetrahydrofuran (THF): THF solvates the ions, affecting reactivity and polymer microstructure. |

| End-capping Agents | Electrophiles used to deliberately terminate the living chain and introduce functional end-groups [15]. | Ethylene Oxide: Yields a primary alcohol chain end. CO₂: Yields a carboxylic acid chain end. |

Polymers serve as the foundational building blocks for a vast array of materials, from everyday plastics to advanced biomedical systems. Their properties and applications are fundamentally governed by their architectural design at the molecular level. Within polymer synthesis and polymerization mechanisms research, understanding the distinctions between homopolymers, copolymers, and network structures is crucial for tailoring materials with precise performance characteristics. Homopolymers, consisting of a single repeating monomer unit, provide simplicity and predictable properties, while copolymers, comprising two or more distinct monomers, enable sophisticated customization of material behavior [20] [21]. Network structures, formed through extensive crosslinking, create complex three-dimensional architectures that underpin advanced functional materials including hydrogels and elastomers [22].

The strategic design of polymer architecture represents a cornerstone of materials science, allowing researchers to manipulate mechanical strength, thermal stability, chemical resistance, and functional behavior through controlled synthesis techniques. This technical guide examines these fundamental polymer architectures within the context of polymerization research, providing a structured comparison of their properties, synthesis methodologies, and applications tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in advanced material design.

Homopolymers: Structural Simplicity and Functional Consistency

Definition and Fundamental Characteristics

Homopolymers are polymers composed of identical repeating monomer units throughout their entire molecular structure [20] [21]. This architectural uniformity results from the polymerization of a single monomer variant, creating chains with consistent chemical composition and regular structural patterns. Common examples include polyvinyl chloride (PVC) constructed from vinyl chloride monomers, polyethylene derived from ethylene, and polypropylene formed from propylene units [20] [23]. The structural homogeneity of homopolymers translates to predictable and consistent bulk properties, making them particularly suitable for applications requiring reliability and ease of processing.

The mechanical behavior of homopolymers is characterized by high tensile strength, substantial stiffness, and significant hardness, attributes that arise from their ability to form crystalline regions with minimal structural disruption [20]. These materials demonstrate excellent short-term creep resistance and increased wear resistance compared to their copolymer counterparts. However, this structural simplicity also imposes certain limitations, including poor ultraviolet resistance, limited acid and alkali resistance, and reduced thermo-oxidative stability [20].

Synthesis Methodologies: Homopolymerization

Homopolymerization follows relatively straightforward synthetic protocols due to the involvement of only a single monomer species. The process typically employs standard polymerization techniques including free-radical polymerization, ionic polymerization, or coordination polymerization, depending on the monomer reactivity and desired molecular weight distribution [24]. For instance, polyethylene is produced through the polymerization of ethylene monomers alone, resulting in a material characterized by strength and resistance to acidic and alkaline environments [21].

Experimental Protocol: Basic Homopolymer Synthesis via Free-Radical Polymerization

- Reagents: Pure monomer (e.g., styrene, methyl methacrylate), initiator (e.g., azobisisobutyronitrile, AIBN), and appropriate solvent if needed.

- Procedure:

- Purify the monomer to remove inhibitors using standard purification techniques (e.g., passing through an inhibitor removal column).

- Charge the reactor with the monomer and solvent (for solution polymerization), then degas the mixture by purging with inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 20-30 minutes.

- Add the initiator to the reaction mixture while maintaining the inert atmosphere.

- Heat the reaction to the initiation temperature (typically 60-80°C for AIBN) with constant stirring.

- Maintain the reaction for a predetermined time (typically 4-24 hours) to achieve desired conversion.

- Terminate the polymerization by rapid cooling and exposure to air.

- Precipitate the polymer into a non-solvent, filter, and dry under vacuum until constant weight.

- Characterization: Molecular weight and distribution via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC); chemical structure confirmation via Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [24].

Copolymers: Architectural Diversity and Tailored Performance

Definition and Classification Framework

Copolymers represent a more architecturally sophisticated class of polymers formed by incorporating two or more distinct monomer units within the same macromolecular chain [20] [21]. This architectural diversity enables precise tuning of material properties by adjusting monomer type, ratio, and sequential arrangement along the polymer backbone. Copolymers are systematically classified based on their monomer sequencing patterns:

- Alternating Copolymers: Feature a regular alternating sequence of two different monomer units (A-B-A-B-A-B) [20].

- Block Copolymers: Contain extended sequences of identical monomers (blocks) connected together (A-A-A-A-B-B-B-B) [20] [24]. These can be diblock, triblock, or multiblock architectures.

- Statistical Copolymers: Exhibit random or statistically distributed monomer sequences following predictable patterns [20].

- Graft Copolymers: Comprise a main chain of one monomer with side chains of a different monomer attached at various points [20].

The compositional versatility of copolymers facilitates the engineering of materials with balanced property profiles, such as combining the rigidity of one monomer with the flexibility of another to achieve specific mechanical performance targets [21].

Synthesis Methodologies: Controlled Copolymerization

Advanced synthetic techniques are required to achieve precise control over copolymer architecture and composition. Living polymerization methods have revolutionized copolymer synthesis by enabling exceptional control over molecular weight, distribution, and chain architecture [24].

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Block Copolymers via RAFT Polymerization

- Reagents: Two or more purified monomers, RAFT chain transfer agent (CTA), initiator (e.g., AIBA or ACVA), and appropriate solvent.

- Procedure:

- Synthesize the first polymer block (Macro-CTA):

- Add Monomer A, CTA, initiator, and solvent to a reaction vessel.

- Degas the mixture via freeze-pump-thaw cycles (3 cycles minimum) or nitrogen purging.

- React at specific temperature (e.g., 60-70°C) for a predetermined time to achieve high conversion while maintaining living characteristics.

- Recover the Macro-CTA by precipitation and purification.

- Chain extension with Monomer B:

- Dissolve the purified Macro-CTA in fresh solvent.

- Add Monomer B and initiator to the solution.

- Degas the mixture thoroughly.

- React at appropriate temperature to form the diblock copolymer (PEG-b-PAA).

- Precipitate the final block copolymer, filter, and dry under vacuum [25].

- Synthesize the first polymer block (Macro-CTA):

- Characterization: Confirm block structure and composition using ( ^1H ) NMR; determine molecular weight and dispersity (Ð) via GPC; analyze self-assembly behavior using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [25] [24].

Network Structures: Complexity Through Crosslinking

Definition and Structural Hierarchy

Network structures represent the most architecturally complex polymer systems, characterized by extensive crosslinking between polymer chains to form three-dimensional matrices [22]. These structures can be derived from either homopolymers or copolymers and are classified based on their crosslinking mechanism (chemical or physical), origin of polymers (natural, synthetic, or hybrid), and structural architecture. When synthesized in nanoparticle form, these crosslinked networks are termed nanogels (NGs, 1-1000 nm) or microgels (MGs, 0.1-100 μm), which swell in solvent while maintaining structural integrity [22].

The crosslinking density fundamentally determines the network's physical properties, including swelling capacity, mechanical strength, and responsiveness to environmental stimuli. Natural polymer networks often utilize chitosan, alginate, or gelatin to achieve biocompatibility and biodegradability, while synthetic networks employ polymers like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) for enhanced control over physicochemical properties [22].

Synthesis Methodologies: Fabricating Three-Dimensional Architectures

Network synthesis employs distinct strategies depending on the desired application and material requirements. Chemical crosslinking creates permanent covalent bonds, while physical crosslinking utilizes reversible interactions such as hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions.

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of Hybrid Copolymeric Hydrogels

- Reagents: Functional monomers (e.g., bis(2-(methacryloyloxy) ethyl) phosphate - BMEP, acrylamide - AAm), natural polymer (e.g., tragacanth gum), crosslinker (e.g., MBAA), initiator (e.g., ammonium persulfate - APS), accelerator (e.g., tetramethylethylenediamine - TEMED).

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the natural polymer (tragacanth gum) in deionized water with stirring until fully hydrated.

- Add the synthetic monomers (BMEP and AAm) and crosslinker to the natural polymer solution with continuous stirring.

- Degas the mixture by bubbling with nitrogen for 15-20 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Add the initiator (APS) and accelerator (TEMED) to trigger free-radical polymerization and crosslinking.

- Pour the reaction mixture into molds and maintain at room temperature or elevated temperature (e.g., 37°C) for 2-24 hours to complete gelation.

- Wash the resulting hydrogels extensively with deionized water to remove unreacted components.

- Characterize the swelling behavior, mechanical properties, and drug release profiles [26].

- Characterization: Confirm chemical structure via FTIR and ( ^{13}C ) NMR; analyze thermal stability via TGA-DSC; examine morphology and porosity using FESEM; evaluate drug release kinetics using UV-Vis spectroscopy [26] [22].

Comparative Analysis: Properties, Performance, and Applications

Quantitative Property Comparison

The architectural differences between homopolymers, copolymers, and network structures manifest in distinct mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Generic Homopolymer, Copolymer, and Network Structures

| Property | Homopolymer (Generic) | Copolymer (Generic) | Network Structure (Hydrogel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.9 g/cm³ [20] | 0.9 g/cm³ [20] | Highly dependent on water content [22] |

| Tensile Strength | 69 MPa [20] | 60 MPa [20] | Typically 0.1 - 5 MPa (highly variable) [22] |

| Tensile Modulus | 1,600 N/mm² [20] | 950 N/mm² [20] | 0.01 - 1 MPa (highly variable) [22] |

| Impact Resistance | Lower [21] [23] | Higher [21] [23] | Not typically characterized |

| Crystallinity | Higher [23] | Lower [23] | Amorphous [22] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | Single, distinct Tg | Can exhibit multiple Tgs | Broad transition [22] |

| Solubility | Dissolves in compatible solvents | Tunable solubility [27] | Swells but does not dissolve [22] |

Application Domains by Architecture Type

The structural characteristics of each polymer architecture direct them toward specific application domains:

Homopolymer Applications: Utilize their uniformity for packaging materials, automotive components, piping systems, textiles, and consumer goods where consistent mechanical properties and processing ease are paramount [20] [21]. Their high tensile strength makes them suitable for gears, bearings, and structural components [20].

Copolymer Applications: Leverage their customizable properties for advanced engineering applications including medical devices, flexible packaging, drug delivery systems, hoses, textiles, and impact-resistant components [20] [21] [22]. Block copolymers specifically enable technologies in nanomedicine, electronic devices, optical elements, and catalytic systems through their self-assembly capabilities [24].

Network Structure Applications: Exploit their three-dimensional structure and responsiveness for biomedical applications including hydrogel wound dressings, drug delivery platforms, tissue engineering scaffolds, biosensing, and regenerative medicine [26] [22]. Their ability to absorb significant amounts of biological fluids while maintaining structural integrity makes them ideal for biological applications.

Architectural Influence on Material Functionality

Structure-Property Relationships Visualized

The fundamental relationship between polymer architecture and material properties can be visualized through the following conceptual framework:

Architecture-Property Relationships in Polymers

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Advanced polymer research requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to specific architectural targets as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Polymer Architecture Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Chain Transfer Agent | Controls molecular weight and enables living polymerization for block copolymers [25] [24] | Block copolymer synthesis |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Biocompatible polymer block providing stealth properties and solubility [25] [22] | Double hydrophilic block copolymers (DHBCs) |

| Acrylic Acid (AA) Monomer | Provides carboxylic acid functional groups for complexation and pH responsiveness [25] | Functional block in copolymers |

| Vinylphosphonic Acid (VPA) | Offers stronger acid functionality for enhanced metal ion binding [25] | Modification of complexation behavior |

| FeCl₃·6H₂O | Source of Fe(III) ions for forming hybrid polyionic complexes (HPICs) [25] | Metallopolymer network formation |

| N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) | Temperature-responsive monomer for smart hydrogels [22] | Stimuli-responsive networks |

| Methylenebis(acrylamide) (MBAA) | Crosslinking agent for creating network structures [22] | Hydrogel fabrication |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Free-radical initiator for vinyl polymerization [24] | General polymerization reactions |

The strategic design of polymer architecture—from simple homopolymer chains to complex copolymer sequences and three-dimensional networks—represents a fundamental dimension of polymer science research. Homopolymers provide structural predictability and mechanical strength, copolymers enable property customization through monomer selection and sequencing, and network structures create multifunctional platforms for advanced biomedical and technological applications. As polymerization methodologies continue to evolve, particularly in living and controlled polymerization techniques, researchers gain increasingly precise tools for architectural control at the nanoscale level. This architectural precision, in turn, enables the development of next-generation materials with tailored properties for specific applications across drug delivery, advanced manufacturing, energy technologies, and biomedical engineering. The continuing synergy between synthetic chemistry, material characterization, and application engineering will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated polymer architectures with enhanced functionality and performance.

In the field of polymer science, the relationship between a polymer's structure and its properties is foundational. While chemical composition is a primary determinant, the physical and mechanical properties of polymers—critical for applications ranging from drug delivery to high-strength materials—are profoundly influenced by three key molecular characteristics: molecular weight, dispersity, and tacticity. These parameters are not inherent to the monomer units but are a direct consequence of the polymerization process and mechanism employed. Within the broader context of fundamentals of polymer synthesis and polymerization mechanisms research, controlling these properties represents a central challenge and goal. Advances in catalytic systems and polymerization strategies, such as reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) and single-site catalysis, have enabled unprecedented precision in tailoring molecular weight distributions, dispersity, and stereochemical structure, thereby allowing for the design of polymers with bespoke performance characteristics [28] [12] [29]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core properties, their interrelationships with synthesis mechanisms, and the methodologies for their characterization and control.

Fundamental Property Definitions and Significance

Molecular Weight and Its Averages

The molecular weight (MW) of a polymer is not a single value but a distribution, as any synthetic polymer sample contains chains of varying lengths. Therefore, different average values are used to characterize the sample.

- Number-Average Molecular Weight ((Mn)): The total weight of all polymer molecules divided by the total number of molecules. It is sensitive to the presence of smaller molecules and is calculated by (Mn = \frac{\sum Ni Mi}{\sum Ni}), where (Ni) is the number of moles of chains with molecular weight (M_i).

- Weight-Average Molecular Weight ((Mw)): The sum of the products of the weight of each fraction and its molecular weight, divided by the total weight of all polymers. It is more sensitive to the presence of higher molecular weight molecules and is calculated by (Mw = \frac{\sum Ni Mi^2}{\sum Ni Mi}).

- Significance: Molecular weight directly influences a vast array of properties. Ultra-high molecular weight (UHMW) polymers ((M_n \geq 10^6) g/mol), for instance, are crucial for developing high-performance materials with superior toughness and wear resistance. However, their synthesis is often complicated by extremely high solution viscosities, necessitating specialized techniques like polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) to manage processability [28]. Conversely, lower molecular weights may be desired for applications requiring lower viscosity or easier processing.

Dispersity (Đ)

Dispersity (Đ), also known as the polydispersity index (PDI), quantifies the breadth of the molecular weight distribution.

- Definition: It is defined as the ratio of the weight-average molecular weight to the number-average molecular weight ((Đ = Mw / Mn)).

- Interpretation: A Đ value of 1.0 indicates a perfectly monodisperse sample where all chains are of identical length. Values greater than 1.0 indicate a distribution of chain lengths. "Low dispersity" (e.g., Đ < 1.20) is often synonymous with well-controlled polymerizations like RDRP, while "high dispersity" (Đ > 1.50) is typical for conventional free radical polymerization [30].

- Impact: Dispersity affects material properties such as mechanical strength, melt viscosity, and self-assembly behavior. Precise control over Đ is essential for tuning these properties. For example, a simplified blending method allows for unparalleled precision in achieving target dispersity values by mixing only two polymers (one of high Đ and one of low Đ), enabling access to any intermediate dispersity value to the nearest 0.01 [30].

Tacticity

Tacticity describes the stereochemical arrangement of pendant groups along the polymer backbone.

- Definition: It refers to the chiral configuration of consecutive stereocenters in the main chain.

- Types:

- Isotactic: All pendant groups are on the same side of the polymer backbone.

- Syndiotactic: Pendant groups alternate regularly from one side to the other.

- Atactic: Pendant groups are arranged randomly.

- Impact: Tacticity profoundly influences crystallinity, thermal properties, and mechanical performance. For instance, highly syndiotactic polypropylene (sPP) exhibits distinct elastic properties and a higher melting point compared to its atactic counterpart. The rational design of single-site catalysts, such as ansa-zirconocenes, allows for the equilibrious modulation of activity, molecular weight, and syndiotacticity, even at industrial-relevant temperatures [29].

Table 1: Summary of Key Polymer Properties and Their Influence

| Property | Definition | Key Influencing Factors | Impact on Material Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Average mass of polymer chains | Polymerization mechanism, monomer concentration, catalyst/initiator efficiency, chain transfer agents | Tensile strength, melt viscosity, toughness, processability |

| Dispersity (Đ) | Breadth of molecular weight distribution ((Mw/Mn)) | Control of polymerization (e.g., RDRP vs. free radical), blending | Mechanical strength, melting range, self-assembly, rheology |

| Tacticity | Stereochemical arrangement of pendant groups | Catalyst stereoselectivity, polymerization temperature | Crystallinity, melting point, solubility, stiffness |

Advanced Control and Synthesis Methodologies

Controlling Molecular Weight and Dispersity

The evolution of controlled polymerization mechanisms has been pivotal in advancing the synthesis of polymers with tailored molecular weights and dispersities.

- Reversible-Deactivation Radical Polymerization (RDRP): Techniques such as atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) and reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization have revolutionized the field by providing exceptional control over (M_n) and enabling the synthesis of low-dispersity polymers (Đ < 1.3) [28] [12]. These methods operate by establishing a dynamic equilibrium between active propagating chains and dormant species, minimizing irreversible chain termination.

- Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly (PISA): For synthesizing ultra-high molecular weight (UHMW) polymers, traditional homogeneous methods lead to prohibitively high viscosities. PISA is a powerful heterogeneous methodology that leverages in-situ self-assembly during chain extension. For example, chain-extending a poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) macroiniferter with N-acryloylmorpholine in aqueous salt solution causes the growing block to become insoluble and self-assemble into nanoparticles. This confines the high molecular weight chains within discrete particles, maintaining a free-flowing dispersion (viscosity < 6 Pa·s) despite the high molecular weight ((M_n > 10^6) g/mol) and concentration of the polymer [28].

- Precision Blending: A remarkably straightforward yet precise method for controlling dispersity involves the blending of two polymers of comparable peak molecular weight but vastly different dispersities (e.g., one with Đ ≈ 1.08 and another with Đ ≈ 1.84). The dispersity of the mixture (Đmix) follows a linear relationship: Đmix = ĐP1 + Wt%P2(ĐP2 - ĐP1). This allows for the preparation of polymers with dispersity values accurate to within 0.01 of the target, a level of precision difficult to achieve through direct synthesis alone [30].

Controlling Tacticity

The control over polymer tacticity is primarily achieved through the use of stereoselective catalysts.

- Single-Site Catalysts (SSCs): These catalysts, such as metallocenes, feature a single, well-defined coordination site for monomer insertion, ensuring uniform stereochemical control. Recent research focuses on the rational design of these catalysts to optimize multiple polymerization outcomes simultaneously. For instance, a gradient modulation strategy applied to cyclopentadienyl-fluorenyl (ansa-zirconocenes) has successfully achieved an equilibrious modulation of activity, molecular weight, and syndiotacticity for propylene polymerization. One specific Zr catalyst (Zr2) demonstrated high activity (up to 4.5 × 107 g/(mol·h)), high molecular weight (up to 60.2 × 104 g/mol), and high syndiotacticity (up to 87.1%) at industrially relevant temperatures (30-50°C) [29]. This remote modulation of the catalyst structure, rather than direct steric hindrance around the metal center, is key to this balanced performance.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical progression and key decision points in selecting synthesis strategies to target specific polymer properties.

Characterization Techniques

Verifying the targeted polymer properties requires a suite of analytical techniques. A multi-technique approach is standard practice in polymer characterization [31] [32].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) or Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): This is the primary technique for determining the molecular weight distribution, from which (Mn), (Mw), and dispersity (Đ) are calculated. It separates polymer molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume in solution [31] [30].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR, particularly (^1)H and (^{13})C NMR, is the definitive method for determining polymer tacticity. It can distinguish between the subtle differences in the local chemical environment of protons or carbons resulting from different stereochemical sequences (e.g., meso (m) or racemo (r) diads) [31] [32].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): DSC measures thermal transitions such as glass transition temperature ((Tg)) and melting point ((Tm)). Since tacticity and molecular weight significantly influence crystallinity and these thermal properties, DSC provides indirect but crucial evidence of stereochemical control [32] [33].

Table 2: Essential Polymer Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Property Measured | Principle | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Molecular Weight ((Mn), (Mw)), Dispersity (Đ) | Separation by hydrodynamic size in solution | Tracking molecular weight evolution during PISA [28] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Tacticity, Chemical Composition, End-group | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei in a magnetic field | Quantifying syndiotacticity ([rrrr]) of sPP [29] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Thermal Transitions (Tg, Tm) | Heat flow difference between sample and reference | Relating sPP's elastic properties to its syndiotacticity and MW [29] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Protocol: UHMW Polymer Synthesis via Aqueous Dispersion PISA

This methodology outlines the synthesis of UHMW double-hydrophilic block copolymers (DHBCs) while avoiding high-viscosity solutions [28].

- Macroiniferter Synthesis: Synthesize a poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (PDMA) macroiniferter via photoiniferter polymerization (365 nm light). Purify and characterize via SEC to confirm well-controlled molecular weight and low dispersity (e.g., PDMA of 30.5 kg mol(^{-1}), Đ < 1.3).

- PISA Chain Extension:

- Reaction Mixture: Dissolve the PDMA macroiniferter and N-acryloylmorpholine (NAM) monomer in a 0.5 M aqueous solution of (NH(4))(2)SO(4) to achieve a solids content of 20% w/w. The kosmotropic salt is critical for inducing salt-sensitivity in the growing PNAM block.

- Polymerization: Purge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (e.g., N(2)) to remove oxygen. Irradiate with 365 nm UV light (3.5 mW cm(^{-2})) under stirring.

- In-situ Assembly: As the PNAM block grows, it will reach a critical degree of polymerization where it becomes sufficiently solvophobic in the salt solution. This triggers self-assembly into polymeric nanoparticles, observed as a transition from a transparent solution to a turbid, blue-tinged but free-flowing dispersion.

- Product Retrieval: To recover the molecularly dissolved UHMW DHBC, simply dilute the nanoparticle dispersion with water. This lowers the (NH(4))(2)SO(_4) concentration, resolubilizing the PNAM blocks and yielding a highly viscous solution of the UHMW polymer.

Protocol: Precision Tuning of Dispersity by Blending

This protocol describes a simplified method to achieve polymers with precisely targeted dispersity values [30].

- Synthesis of Parent Polymers: Synthesize two polymers of the same monomer (e.g., poly(methyl acrylate)) and similar peak molecular weight ((M_p)) but with drastically different dispersities. For instance, use photoATRP with a high catalyst concentration to produce a low-Đ polymer (P1, Đ ≈ 1.08) and with a very low catalyst concentration to produce a high-Đ polymer (P2, Đ ≈ 1.84). Purify both polymers rigorously.

- Preparation of Stock Solutions: Prepare stock solutions (~1 mg/mL) of each purified polymer in the SEC eluent to minimize weighing errors.

- Blending Calculation: Use the linear equation Đmix = ĐP1 + Wt%P2(ĐP2 - ĐP1) to calculate the volume of each stock solution needed to achieve the target dispersity.

- Mixing and Validation: Combine the calculated volumes of the two stock solutions in a vial and mix thoroughly. Analyze the final mixture by SEC to confirm the experimental dispersity matches the predicted value (typically within 0.01).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Advanced Polymer Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Photoiniferter | Mediates controlled radical polymerization under UV light, enabling high chain-end fidelity for UHMW polymers. | Poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (PDMA) macroiniferter [28]. |

| Kosmotropic Salt | Induces phase separation of otherwise soluble polymers in aqueous solution, enabling PISA. | Ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄) [28]. |

| Single-Site Catalyst | Provides a uniform active site for stereospecific monomer insertion, controlling polymer tacticity. | Substituted cyclopentadienyl-fluorenyl ansa-zirconocenes (e.g., Zr2) [29]. |