Reactive Extrusion Processing: Advanced Methods and Biomedical Applications for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of reactive extrusion (REX), a solvent-free, continuous process that combines polymer modification or synthesis with melt processing.

Reactive Extrusion Processing: Advanced Methods and Biomedical Applications for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of reactive extrusion (REX), a solvent-free, continuous process that combines polymer modification or synthesis with melt processing. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of REX as a chemical reactor, details its methodological application in creating advanced materials like drug-delivery hydrogels, and discusses advanced troubleshooting and process optimization strategies. The content further addresses the critical validation and comparative analysis of REX-produced materials, synthesizing key takeaways to highlight the method's significant potential for enhancing efficiency, sustainability, and innovation in biomedical and clinical research.

Reactive Extrusion Fundamentals: Principles and Core Concepts for Polymer Science

Reactive Extrusion (REX) is a advanced manufacturing process that deliberately utilizes a screw extruder as a continuous chemical reactor to perform polymerization and chemical modification of polymers in a single, integrated step [1]. This technology represents a fundamental fusion of traditionally separate disciplines, combining polymer chemistry—including reactions such as polymerization, grafting, and functionalization—with the thermomechanical operations of an extruder, which handles melting, mixing, devolatilization, and shaping [2] [1]. By integrating the reactor and the processor, REX transforms the extruder from a mere processing device into a sophisticated reaction vessel capable of intense mixing and precise control over thermal and mechanical energy input [2].

The process is characterized by its continuous operation, which stands in contrast to conventional batch polymer reactions. It subjects raw materials to low thermal stress and, due to the excellent mixing properties of twin-screw systems, can handle a very broad range of viscosities, including highly viscous products that can be problematic in batch processes [3]. A key advantage is the elimination of solvents or the significant reduction in their use compared to traditional batch polymerization, leading to a more sustainable process with reduced costs and emissions [4]. The versatility of reactive extrusion allows it to be applied across a wide spectrum of the polymer industry, from the synthesis of new polymers to the modification and recycling of existing materials [4] [1].

Key Applications of Reactive Extrusion

The fusion of chemical reaction and mechanical processing enables a diverse range of applications in polymer science and biomass valorization. The table below summarizes the primary application categories and provides specific examples of each.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Reactive Extrusion

| Application Category | Specific Examples & Processes |

|---|---|

| Polymer Synthesis [3] [4] | Production of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), polyamide 6 (PA 6), and biopolyesters like polylactic acid (PLA). |

| Polymer Modification [2] [4] [1] | Grafting with maleic anhydride (e.g., PE-g-MAH, PP-g-MAH); Chain extension or branching; Controlled degradation of polypropylene, polyamides, and polyesters. |

| Reactive Blending & Compatibilization [4] | Creating polymer blends with improved properties; Formulation of thermoplastic vulcanizates (TPV). |

| Chemical Recycling [4] | Depolymerization of polyamides, polyesters, and polyurethanes for resource recovery. |

| Biomass Valorization [5] | Solvent-free depolymerization of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., sawdust) to produce platform biochemicals like acetic acid, methanol, and furanic compounds. |

Experimental Protocols in Reactive Extrusion Research

Protocol: Investigation of Processing Parameters in Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM)

This protocol outlines the methodology for studying the effects of key processing parameters on the properties of parts fabricated via Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing, based on a published study [6].

1. Objective: To understand the effects of process parameters, including extrusion rate, deposition speed, and time elapsed between layers, on the dimensional accuracy, shape fidelity, and mechanical properties of REAM-fabricated parts.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- REAM System: A robotic system comprising a 6-axis robot arm, a resin dispensing system, a passive mixing nozzle, and a heated build plate [6].

- Material: A two-part thermoset resin system, specifically a mixture of 70% Epo-Thin resin and 30% Aliphatic Polyamine curing agent by weight [6].

- Metrology Tools: Calipers for dimensional measurements.

- Mechanical Testing Equipment: Universal testing machine for tensile tests.

3. Experimental Procedure:

- System Calibration: Pre-calibrate the flow rates of the resin and catalyst pumps to ensure high accuracy and repeatability of the volumetric mixing ratio [6].

- Specimen Fabrication:

- Print standardized test specimens, such as a metrology cube and tensile testing bars (e.g., ASTM D638 Type V).

- Systematically vary the following parameters across the prints:

- Extrusion Rate (Q): The volumetric flow rate of the mixed resin.

- Deposition Speed (V): The speed of the print head.

- Time Elapsed Between Layers (Δt): The waiting time between depositing successive layers.

- Data Collection:

- Dimensional Accuracy: Measure the total height and layer width of the printed cubes from multiple edges and calculate the averages [6].

- Mechanical Properties: Perform tensile tests on the printed bars to determine the ultimate tensile strength and elastic modulus [6].

- Geometric Fidelity: Assess the ability to print overhang and bridge structures by measuring the maximum successful overhang angle and the sag of bridged structures [6].

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured height and mechanical properties as a function of the time between layers.

- Develop a material extrusion model to relate printing speed and extrudate size.

- Correlate the observed geometric fidelity with the material's curing kinetics and the selected processing parameters.

Protocol: Thermomechanical Biorefining of Biomass via Reactive Extrusion

This protocol details the use of reactive extrusion for the continuous depolymerization of lignocellulosic biomass into biochemicals [5].

1. Objective: To investigate the effects of temperature, moisture content, screw speed, and screw design on the yield and composition of biochemicals derived from sawdust.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Material: Pinus radiata sawdust, sieved to particles of less than 3 mm [5].

- Equipment: Co-rotating twin-screw extruder with modular screw design and barrel temperature control. A nitrogen purge system is used to maintain an inert atmosphere [5].

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Determine the moisture content of the sawdust. Adjust the moisture content to the target level (e.g., 50% by weight) if necessary [5].

- Screw Configuration: Design the screw profile to include specific elements, notably kneading elements, which are key for achieving good processing and reaction of the solid biomass [5].

- Parameter Variation: Conduct extrusion runs while systematically varying the following parameters:

- Temperature: Process the sawdust across a defined range (e.g., 275°C to 375°C).

- Moisture Content: Test different moisture levels.

- Screw Speed: Vary the rotation speed of the screws.

- Product Collection and Analysis: Collect the liquid effluent (liquor) produced during extrusion. Analyze the biochemical composition of the liquor using techniques such as gas chromatography to quantify yields of acetic acid, methanol, furans, and phenolic compounds [5].

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of biochemicals recovered from the sawdust in the liquid phase.

- Analyze how the concentration of specific biochemicals (e.g., furanic content, aromatic phenols) changes with the varied processing parameters.

Table 2: Key Processing Parameters and Their Investigated Ranges in Featured Studies

| Parameter | Investigated Range / Value | Process | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Between Layers | Varied | REAM [6] | Significantly affects the total height and mechanical properties of the fabricated part. |

| Nozzle Height | 3.5 mm | REAM [6] | A fixed parameter influencing layer deposition. |

| Extrusion Rate | Varied | REAM [6] | Coupled with deposition speed to control extrudate size. |

| Temperature | 275°C - 375°C | Biomass Biorefining [5] | Governs the yield and profile of biochemicals; higher temperatures increased furanic content. |

| Moisture Content | 50% (by weight) | Biomass Biorefining [5] | Instrumental in the isolation of biochemicals from sawdust. |

| Screw Speed | Varied (little to no effect) | Biomass Biorefining [5] | Had minimal impact on the biochemical composition obtained. |

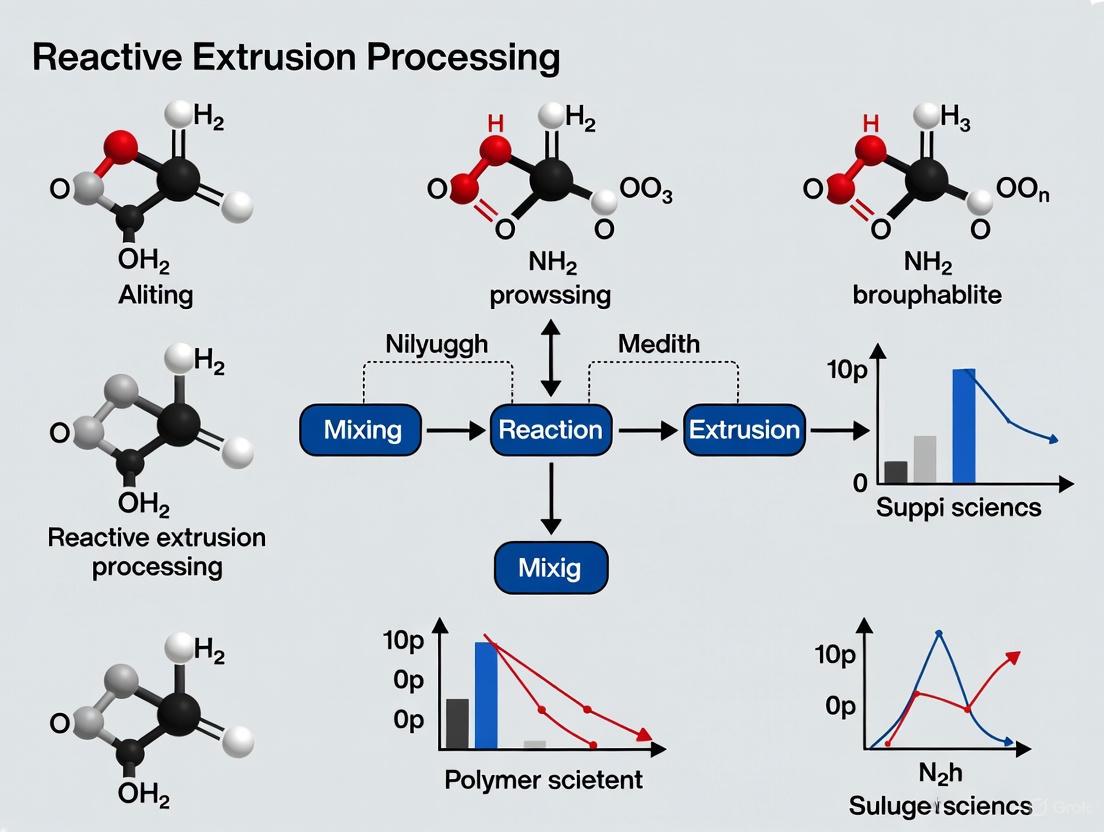

Visualization of Reactive Extrusion Workflows

Logical Workflow for a Reactive Extrusion Process

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a generalized reactive extrusion process, from parameter input to final output, highlighting the cause-and-effect relationships central to the methodology.

Experimental Workflow for Biomass Biorefining

This diagram outlines the specific experimental workflow for converting sawdust into biochemicals via reactive extrusion, as detailed in Section 3.2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing reactive extrusion experiments, the selection of appropriate materials and equipment is critical. The following table details key components of the reactive extrusion "toolkit" based on the protocols and applications discussed.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Reactive Extrusion

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder | The core reactor platform; provides superior mixing, devolatilization, and self-wiping action compared to single-screw systems. Modular screws allow for process customization [3] [2]. | ZSK twin screw extruders [3]. |

| Modular Screw Elements | Enable custom configuration of the screw to control shear, mixing, and residence time. Kneading blocks are crucial for dispersive mixing and chemical reaction efficiency [2] [5]. | Kneading elements for biomass processing [5]. |

| Reactive Monomers & Polymers | Serve as the primary feedstock for polymerization or modification reactions. | Monomers for PMMA, Polyamide 6, and TPU synthesis [3]. |

| Functionalization Agents | Chemicals used to graft new functional groups onto polymer chains, altering their properties or improving compatibility. | Maleic anhydride for grafting onto polyolefins [4] [1]. |

| Chain Extenders | Used to increase the molecular weight of polymers by reacting with their end groups. | Used to enhance the molecular weight of biopolymers like PLA [1]. |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | A renewable feedstock for biorefining. Its three main components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) break down into valuable biochemicals under thermomechanical stress [5]. | Pinus radiata sawdust [5]. |

| Two-Part Thermoset Resins | For Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM); the resin and curing agent are mixed and react exothermically during deposition [6]. | Epo-Thin resin and Aliphatic Polyamine curing agent [6]. |

| Sarsasapogenin | Sarsasapogenin | High-purity Sarsasapogenin for research. Explore its applications in neuroprotection, anti-inflammation, and diabetes studies. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

| SBE13 hydrochloride | SBE13 hydrochloride, CAS:1052532-15-6, MF:C24H28Cl2N2O4, MW:479.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Reactive extrusion (REX) is an advanced manufacturing process that transforms the extruder from a mere shaping device into a continuous chemical reactor and processor simultaneously [7]. This technology integrates chemical synthesis—such as polymerization, grafting, or compatibilization—with the mixing, melting, and shaping operations of a standard extruder, creating a single, streamlined operation [8]. The process is characterized by its solvent-free operation, continuous nature, and capacity for high-efficiency synthesis, making it particularly valuable for industries ranging from pharmaceuticals and polymers to sustainable material production [7] [9].

The fundamental principle involves introducing raw materials—monomers, polymers, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), or other reagents—into the extruder barrel, where they undergo chemical transformation under precisely controlled thermal and mechanical energy input before being extruded as finished product [2]. Twin-screw extruders, especially co-rotating designs, are the industry standard for reactive extrusion due to their superior mixing capacity, modular screw configuration, and precise control over process parameters across multiple barrel zones [7].

Core Advantages and Quantitative Benefits

The integration of reaction and processing in one apparatus provides distinct advantages over traditional batch methods. The table below summarizes the key benefits and their practical implications.

Table 1: Core Advantages of Reactive Extrusion over Traditional Batch Processes

| Advantage | Key Features | Resulting Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent-Free Operation | Eliminates volatile organic compounds (VOCs); no solvent recovery needed [7] [9]. | Reduces environmental footprint; lowers energy costs for solvent removal; enhances product purity and safety [7] [9] [10]. |

| Continuous Processing | Single-pass operation from raw material to finished product; steady-state conditions [7] [2]. | Higher productivity and throughput; superior product consistency with reduced batch-to-batch variation [7] [8]. |

| High Efficiency | Combined synthesis and processing; significantly faster reaction kinetics [8] [10]. | Drastic reduction in processing time (from hours to minutes); lower energy consumption per unit of product [9] [10]. |

The quantitative impact of these advantages is evident across various applications. The following table compiles performance data from recent research and industrial implementations.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Reactive Extrusion in Various Applications

| Application | Traditional Process | Reactive Extrusion Process | Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Synthesis (TPU) | Batch reactor: Multiple steps, separate pelletization [7] | Continuous polymerization in a single extruder [7] | Eliminates intermediate handling and reduces energy consumption via direct processing [7]. |

| Pharmaceutical HME | Solvent-based methods requiring drying and recovery [11] | Solvent-free mixing of API and polymer to form amorphous solid dispersions [11] [12] | Improves solubility/bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs; avoids solvent residues [11] [12]. |

| Synthesis of Phenolic Resins | Batch process with solvent, long reaction times [9] | Solvent-free synthesis in ~3 minutes at 150–170°C [9] | Replaces toxic formaldehyde; achieves high conversion in extremely short time [9]. |

| Mechanochemical Synthesis (Leuckart Reaction) | Batch solution: 6–25 hours at 160–185°C [10] | Solvent-free extrusion: 5–15 minutes at 100–150°C [10] | Quantitative conversion with >99% selectivity for amide synthesis [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Reactive Extrusion

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing reactive extrusion in research settings, focusing on polymer synthesis and pharmaceutical formulation.

Protocol: Continuous Polymerization of Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU)

Principle: This protocol describes the continuous synthesis of TPU via polyaddition reaction in a twin-screw extruder, where polyols, diisocyanates, and chain extenders react to form a high-performance polymer in a single pass [7].

Materials and Equipment:

- Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder: L/D ratio ≥ 44:1, with multiple independently controlled heating zones and precision feed systems [7].

- Raw Materials: Polyol (e.g., polyether or polyester diol), Diisocyanate (e.g., MDI), Chain Extender (e.g., 1,4-butanediol). All materials must be dried to water content < 0.02% [7].

- Downstream Equipment: Underwater pelletizer, cooling water bath, strand pelletizer, or drying unit [7].

Procedure:

- Extruder Setup: Configure the modular screw profile to include conveying elements, kneading blocks for mixing, and a reaction zone. Ensure tight control over the temperature profile along the barrel [7].

- Temperature Profile Establishment: Set the barrel temperatures to the following zones:

- Rear Zones (Feeding): 315–340°F (157–171°C) for initial material plasticization.

- Middle Zones (Reaction): 340–365°F (171–185°C) for polymerization progression.

- Front Zones (Metering): 360–385°F (182–196°C) for melt homogenization and stabilization [7].

- Material Feeding: Accurately meter the polyol, diisocyanate, and chain extender into the feed throat using calibrated feeders. Stoichiometric balance is critical for achieving target molecular weight [7].

- Reaction and Extrusion: Initiate the screw rotation (typical speed 100–300 rpm). The reaction occurs during the residence time within the barrel (typically 1-5 minutes). Monitor torque and pressure to ensure stable operation [7].

- Pelletization: Pass the molten extrudate through an underwater pelletizer or a water cooling bath followed by a strand pelletizer to obtain TPU pellets [7].

- Quality Control: Perform real-time monitoring of melt pressure and torque. Offline, characterize the product for properties like hardness, molecular weight, and rheological behavior [7].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and material flow for this protocol:

Protocol: Synthesis of Amorphous Solid Dispersions via Vertical Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME)

Principle: This protocol utilizes a vertical twin-screw extruder to form a molecularly homogeneous amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) of a poorly water-soluble Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) within a polymer matrix, enhancing the drug's dissolution rate and bioavailability [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- Vertical Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder: 10.5 mm screw diameter, 40:1 L/D ratio, with multiple heating/cooling zones and a top-mounted volumetric feeder [12].

- API: Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA) - model thermosensitive drug [12].

- Polymer Carriers: Soluplus, Kollidon 12 PF [12].

- Analytical Equipment: Powder X-ray Diffractometer (PXRD), Dissolution Testing Apparatus (USP II) [12].

Procedure:

- Formulation Premixing: Weigh the API and polymer carrier(s) to the desired ratio (e.g., 20-50% w/w API load). Mix in a Turbula mixer or similar for 15 minutes to ensure a homogeneous powder blend before extrusion [12].

- Vertical Extruder Setup: Configure the screw with standard conveying elements and at least two kneading zones (e.g., in barrel zones 3 and 5) to ensure adequate distributive mixing. Set the temperature profile:

- Feed Zone / Zone 1: 40°C (for stable feeding)

- Zone 2: 90°C

- Zones 3-7: 115-120°C (uniform temperature for melting and dispersion)

- Zone 8 (Die): 100°C (for controlled cooling before discharge) [12].

- Feeding and Extrusion: Feed the pre-mixed powder into the top port of the vertical extruder using a volumetric feeder. Set the main screw speed to 100 rpm and the feeding screw to 30 rpm (approximate output 300 g/h) [12].

- Collection: Collect the extrudate as strands. Cool the strands using a fixed-temperature cooling block or a conveyor belt [12].

- Characterization:

- Solid State Analysis: Use PXRD to confirm the complete conversion of the crystalline API to the amorphous state within the polymer matrix.

- Dissolution Testing: Perform in vitro dissolution tests under sink conditions (e.g., using USP Apparatus II) to demonstrate the enhanced release profile of the ASD compared to the pure crystalline API [12].

The workflow for this pharmaceutical application is outlined below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of reactive extrusion requires careful selection of materials and equipment. The following table details key components and their functions in a research context.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Reactive Extrusion Research

| Category | Item | Function & Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment | Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder | The standard reactor platform; its modular screw and barrel design allows for precise control over shear, residence time, and mixing, enabling a wide range of chemistries [7] [8]. |

| Equipment | Modular Screw Elements | Conveying, kneading, and mixing elements configured to match reaction requirements (e.g., intense kneading for dispersion, gentle conveying for degradation-sensitive materials) [7] [13]. |

| Polymeric Carriers | Soluplus | A common amphiphilic polymer used in HME to enhance the solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble APIs by forming stable amorphous solid dispersions [12]. |

| Polymeric Carriers | Kollidon VA 64 | A widely used copolymer in pharmaceutical HME that acts as a matrix former for amorphous dispersions, offering good processability and release properties [11]. |

| Monomers/Reagents | Terephthalaldehyde (TPA) & Resorcinol | Non-toxic, potentially bio-based monomers used in solvent-free synthesis of formaldehyde-free phenolic resins, demonstrating REX's application in green chemistry [9]. |

| Monomers/Reagents | Ammonium Formate | Acts as both a nitrogen source and a reducing agent in solvent-free mechanochemical synthesis (e.g., Leuckart reaction) for continuous production of amides and amines [10]. |

| Process Aids | Plasticizers (e.g., PEG, Citrates) | Reduce melt viscosity and glass transition temperature of polymer-API blends, lowering required processing temperatures and protecting thermosensitive compounds [11]. |

| Sch 38519 | Sch 38519, MF:C24H25NO8, MW:455.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Scriptaid | Scriptaid, CAS:287383-59-9, MF:C18H18N2O4, MW:326.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Reactive extrusion stands as a transformative technology that effectively marries chemical synthesis with processing efficiency. Its core advantages—solvent-free operation, continuous processing, and high efficiency—address critical needs in modern manufacturing, including sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and product quality control [7] [9]. The experimental protocols and toolkit provided herein offer a foundation for researchers to leverage this versatile platform.

The potential for REX extends beyond the examples given, showing promise in areas like reactive compatibilization of polymer blends, sustainable synthesis of vitrimers, and mechanochemical organic synthesis, all conducted in a continuous, solvent-free manner [2] [10] [13]. As the demand for greener and more efficient chemical processes grows, reactive extrusion is poised to play an increasingly pivotal role in the future of polymer, pharmaceutical, and advanced materials research.

Reactive extrusion (REX) is a continuous process that combines traditional polymer extrusion with controlled chemical reactions, serving as a highly efficient chemical reactor for polymer synthesis and modification [14]. This single-step, solvent-free operation is a cornerstone of modern polymer processing, enabling precise control over molecular architecture and final material properties [15]. The process is characterized by short residence times (typically several minutes) and is particularly suitable for fast chemical reactions, though challenges include managing high viscosities, self-heating effects, and potential thermal degradation [14].

The table below summarizes the four core chemical reactions covered in these application notes, their primary objectives, and typical reagents used.

Table 1: Overview of Core Chemical Reactions in Reactive Extrusion

| Reaction Type | Primary Objective | Exemplary Reagents & Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Grafting | Chemical modification of polymer chains to introduce functional groups or side chains. | Maleic Anhydride (MAH) grafted onto Polyethylene-Octene (POE) or Styrene Ethylene Butylene Styrene (SEBS) [16]. |

| Polymerization | In-situ synthesis of polymers from monomers within the extruder. | Epoxy/amine thermoset systems synthesized during mixing with thermoplastic polypropylene (PP) [14]. |

| Compatibilization | Enhancement of interfacial adhesion between immiscible polymer phases in blends or composites. | MAH-g-SEBS for polyolefin blends; Methylene Diphenyl Diisocyanate (MDI) for PBAT/EVOH blends [16] [17]. |

| Chain Extension | Increase in molecular weight and melt viscosity through reactions that link polymer chains. | Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) for cross-linking Polylactic Acid (PLA); MDI acting as a chain extender [18] [17]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Reactive Compatibilization of Polymer Blends using Elastomer-Grafted Agents

Application Note: The primary challenge in creating polymer blends is the inherent immiscibility of different polymers, leading to poor interfacial adhesion and weak mechanical properties. Reactive compatibilization addresses this by introducing agents that form in-situ chemical bonds at the interface, drastically improving stress transfer and material performance [16]. This protocol details the use of maleic anhydride-grafted-SEBS (MAH-g-SEBS) to compatibilize polyolefin-based blends.

Experimental Protocol:

Material Preparation:

- Polymer Blend Components: Weigh the immiscible polymer phases (e.g., Polypropylene (PP) and Polyamide (PA6)).

- Compatibilizer: Weigh the MAH-g-SEBS compatibilizer. A typical loading is between 2-10% by total weight of the blend [16].

- Pre-drying: Dry all polymer pellets and the compatibilizer in a vacuum oven at 80°C for a minimum of 12 hours to remove moisture.

Reactive Extrusion Process:

- Equipment: Employ a co-rotating twin-screw extruder, which provides superior mixing and molecular dispersion essential for complex reactive applications [15] [14].

- Temperature Profile: Set a multi-zone barrel temperature profile appropriate for the polymer matrix with the highest melting point. For a PP/PA6 blend, a profile ranging from 190°C (feed zone) to 230°C (die zone) is suitable.

- Screw Speed: Set the screw speed to 200-300 rpm to ensure adequate shear mixing and residence time for the compatibilization reaction.

- Feeding: Use separate feeders to introduce the main polymer blend components and the MAH-g-SEBS compatibilizer into the main feed hopper.

- Extrusion & Pelletization: Extrude the molten, compatibilized blend through a strand die, cool in a water bath, and pelletize.

Post-Processing & Characterization:

- Injection Molding: Mold the pelletized material into standard test specimens (e.g., tensile bars, impact specimens) using an injection molding machine.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile (ASTM D638) and impact (ASTM D256) tests. The compatibilized blend is expected to show significantly improved elongation at break and impact strength compared to the uncompatibilized blend due to enhanced interfacial adhesion [16].

- Morphological Analysis: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) on cryo-fractured surfaces to observe the reduction in dispersed phase domain size, indicating successful compatibilization.

Diagram 1: Workflow for reactive compatibilization via extrusion.

Protocol: Cross-linking and Chain Extension of PLA using Dicumyl Peroxide

Application Note: While Polylactic Acid (PLA) is a popular bio-derived polymer, its brittleness and low thermal stability limit its applications. This protocol utilizes reactive extrusion with Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) as a free-radical initiator to simultaneously cross-link PLA chains and anchor polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based plasticizers. This process enhances mechanical toughness, reduces plasticizer migration, and improves thermal stability, making PLA suitable for demanding applications like flexible packaging and high-performance materials [18].

Experimental Protocol:

Material Formulation:

- Polymer: Dry PLA pellets at 80°C for 8 hours.

- Plasticizer: Weigh PEG-based plasticizer (e.g., 15-20% by weight of PLA).

- Cross-linking Agent: Weigh Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP). A typical concentration is 0.5-1.0 parts per hundred parts of resin (phr) [18].

Reactive Extrusion Process:

- Equipment: Use a twin-screw extruder for intensive distributive mixing.

- Temperature Profile: Set a barrel temperature profile from 160°C (feed zone) to 190°C (die head). The controlled thermal decomposition of DCP (typically initiating around 170°C) is critical for generating free radicals [18].

- Screw Configuration: Employ a screw design with high-shear mixing elements to ensure uniform dispersion of the peroxide and efficient reaction.

- Feeding: Pre-mix dried PLA, PEG, and DCP in a tumbler mixer before introducing the mixture into the extruder's main feed hopper.

Post-Processing & Characterization:

- Film Casting: The extrudate can be pelletized and then cast into films using a compression molding press or a cast film line.

- Mechanical Testing: Test films for tensile properties (ASTM D882). The cross-linked PLA-PEG-DCP system (PLA-PEG-R) should exhibit a high elongation at break (e.g., >60%) while maintaining satisfactory tensile strength, a significant improvement over neat PLA (~12%) [18].

- Thermal Analysis: Use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to determine the degradation temperature. The cross-linked material shows enhanced thermal stability, with degradation temperatures increasing from ~269°C to over 330°C [18].

- Migration Testing: Measure plasticizer migration using gravimetric or chromatographic methods. The cross-linking reaction drastically reduces migration, with values dropping from 140.3 mg kgâ»Â¹ in non-cross-linked blends to 40.8 mg kgâ»Â¹ in the cross-linked system [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Data for Cross-linked PLA via Reactive Extrusion [18]

| Property | Neat PLA | PLA-PEG Blend (Non-Reactive) | PLA-PEG-R (with DCP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elongation at Break (%) | 12.0 | 61.3 | >60 (maintained) |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | Baseline | Satisfactory | Satisfactory (maintained) |

| Plasticizer Migration (mg kgâ»Â¹) | Not Applicable | 140.3 | 40.8 |

| Onset Degradation Temperature (°C) | - | 268.7 | 333.8 |

| Glass Transition Temperature, Tg (°C) | - | - | 38.3 |

Protocol: Data-Driven Modeling for Optimization of Reactive Extrusion

Application Note: The complexity of reactive extrusion, involving coupled phenomena of fluid flow, heat transfer, and reaction kinetics, makes traditional physics-based modeling challenging [14]. This protocol outlines a machine learning (ML) approach to construct a predictive model linking material and process parameters to final part properties, enabling rapid process optimization without requiring full mechanistic understanding.

Experimental Protocol:

Data Collection & Experimental Design:

- Define Input Parameters: Identify key variables: material formulations (e.g., reactant types, compatibilizer concentration), and processing parameters (e.g., screw speed, temperature profile, flow rate) [14].

- Define Output Responses: Identify Quantities of Interest (QoI): mechanical properties (tensile strength, impact strength), morphological data, and conversion rates.

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Create a structured experimental plan (e.g., Full Factorial, Central Composite Design) to efficiently explore the multi-parametric space.

Model Construction & Training:

- Data Splitting: Divide the collected dataset into training and validation subsets.

- ML Technique Selection: Employ techniques capable of operating with limited data. Sparse Proper Generalized Decomposition (sPGD) is recommended for extracting compact, non-linear models from a limited number of experiments [14].

- Model Training: Use the training data to build the input/output model. The objective is to create a reliable function:

Properties = f(Material_Formulation, Processing_Parameters).

Model Validation & Deployment:

- Validation: Test the trained model's predictions against the held-out validation data to assess its accuracy.

- Optimization: Use the validated model to run in-silico simulations and identify the optimal set of processing parameters that will yield a target property (e.g., maximum toughness).

- Verification: Conduct a final verification experiment using the model-predicted optimal parameters to confirm the outcome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Reactive Extrusion Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Reactive Extrusion | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride (MAH) | Grafting monomer; introduces polar reactive sites onto non-polar polymer backbones for enhanced compatibility [16]. | Creation of compatibilizers like MAH-g-SEBS for polyolefin/polyamide blends [16]. |

| Styrene Ethylene Butylene Styrene (SEBS) | Thermoplastic elastomer matrix for graft compatibilizers; provides toughness and compatibility with many polymers [16]. | Used as the base polymer for MAH grafting to produce an effective compatibilizer [16]. |

| Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | Free-radical initiator; generates radicals upon thermal decomposition to initiate cross-linking and grafting reactions [18]. | Cross-linking of PLA with PEG plasticizers to reduce migration and improve properties [18]. |

| Methylene Diphenyl Diisocyanate (MDI) | Multi-functional monomer; acts as both a compatibilizer and chain extender by reacting with hydroxyl and carboxyl groups [17]. | Enhancing the elasticity and compatibility of PBAT/EVOH blends [17]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Bio-based plasticizer; reduces intermolecular forces in polymers, increasing chain mobility and flexibility [18]. | Plasticization of PLA to overcome brittleness, subsequently cross-linked with DCP [18]. |

| Anhydride Maleic Grafted Polypropylene (PP-g-MA) | Compatibilizer; improves interfacial adhesion between polar and non-polar phases in a blend [14]. | Compatibilizing the interface between polypropylene (PP) and an epoxy/amine thermoset phase [14]. |

| Serotonin azidobenzamidine | Serotonin azidobenzamidine, CAS:98409-42-8, MF:C17H16N6O, MW:320.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Setomimycin | Setomimycin, CAS:69431-87-4, MF:C34H28O9, MW:580.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Key reagents and their links to core reaction types.

Application Notes

Reactive extrusion (REX) is a continuous process that uses an extruder as a chemical reactor, intensifying manufacturing by combining chemical synthesis or modification with operations like compounding and devolatilization into a single, solvent-free step [19]. The following notes detail its application across material classes.

Application Note REX-AN-01: Reactive Extrusion of Synthetic Polyolefins

Objective: To synthesize polyolefin graft copolymers, such as maleic anhydride-grafted polypropylene (PP-g-MA), for use as compatibilizers in polymer blends [20] [19].

Background and Rationale: Polyolefins are preferred substrates for REX due to their availability, low cost, and wide application [20]. Grafting polar monomers onto non-polar polyolefin backbones enhances their adhesion and compatibility with other polymers, a process efficiently accomplished via reactive extrusion [2]. The REX process for polyolefin modification offers significant advantages, including minimal solvent use, simple product isolation, short reaction times, and continuous operation [20]. A key industrial application is the "vis-breaking" or controlled rheology of recycled PP to reduce its viscosity [19].

Key Processing Parameters: Screw design and speed, reaction temperature profile, initiator concentration, and monomer feeding rate are critical. Sufficient mixing intensity and residence time are required to achieve the desired grafting levels while minimizing undesirable side reactions like polymer degradation or cross-linking [20] [2].

Application Note REX-AN-02: Reactive Compatibilization of Natural Polysaccharides

Objective: To achieve reactive compatibilization of plant polysaccharides (e.g., starch) with other biobased polymers to create advanced material systems [21].

Background and Rationale: Native plant polysaccharides, while abundant and renewable, often exhibit disadvantages such as reduced thermal stability, moisture absorption, and limited mechanical performance compared to synthetic polymers [21]. These properties hinder their direct use in advanced applications. Reactive extrusion enables the chemical modification and compatibilization of polysaccharides like starch and lignocellulosic materials with other biopolymers, facilitating the development of sustainable materials [21]. This approach has been successfully implemented in projects such as BIOBOTTLE, which focused on increasing the temperature resistance of biodegradable materials for dairy packaging [19].

Key Processing Parameters: The chemical structure of the polysaccharides and partner polymers, the selection of a compatibilizer or coupling agent, and the precise control of melt temperature and shear during extrusion are paramount for generating a homogeneous blend with improved macroscopic properties [21].

Application Note REX-AN-03: Chemical Modification of Lignin for Thermoplastic Biomaterials

Objective: To chemically modify Kraft lignin via esterification with anhydrides (e.g., succinic or maleic anhydride) using REX to produce thermoplastic materials suitable for biodegradable packaging [22] [23].

Background and Rationale: Lignin is one of the most abundant biopolymers but is underutilized in high-value applications due to its complex structure and processing difficulties [23]. Esterification of its aliphatic and aromatic hydroxyl groups alters its properties, improving miscibility with other polymers like polystyrene and enhancing thermal stability [23]. Reactive extrusion is a particularly suitable "green" method for this modification, as it is solvent-free, energy-efficient, and offers fast, continuous processing [23]. This valorization route supports the development of recyclable and biodegradable packaging, contributing to a sustainable economy [22].

Key Processing Parameters: The use of plasticizers (e.g., DMSO, glycerol) is essential to process lignin by lowering its melt viscosity and preventing excessive torque in the extruder [23]. Reaction temperature, screw speed, and the equivalent of anhydride per lignin unit are key variables controlling the extent of esterification.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Data from Reactive Extrusion Studies

| Material System | Key Measured Property | Value / Range | Influencing Parameters | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REAM Thermoset [6] | Ultimate Tensile Strength | 62 - 72 MPa | Extrusion rate, deposition speed | [6] |

| REAM Thermoset [6] | Young's Modulus | 2.4 - 2.9 GPa | Extrusion rate, deposition speed | [6] |

| REAM Thermoset [6] | Strain at Break | 3.5 - 5.5 % | Extrusion rate, deposition speed | [6] |

| Lignin Esterification [23] | Anhydride Loading | 0.1 - 0.3 eq/unit | Molar ratio to lignin phenylpropane unit | [23] |

| Lignin Esterification [23] | Extrusion Temperature | 140 °C | Optimized for plasticized lignin | [23] |

| Lignin Esterification [23] | Screw Speed | 60 rpm | Torque and SME control | [23] |

| General REX Process [19] | Residence Time | 1 - 20 minutes | Screw speed, L/D ratio, viscosity | [19] |

| General REX Process [19] | Extruder L/D Ratio | >44 up to 90 | Required for sufficient reaction time | [19] |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reactive Extrusion

| Reagent / Material | Function in Reactive Extrusion | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride (MAH) | Grafting monomer to introduce reactive functionality and polar groups onto polymer chains. | Functionalization of polyolefins (PE-g-MAH, PP-g-MAH) [19] [2]. |

| Peroxides (e.g., DCP) | Free radical initiators to start grafting reactions by generating radicals on the polymer backbone. | Free radical grafting of monomers onto polyolefins [20]. |

| Succinic Anhydride | Esterification agent for modifying hydroxyl-containing polymers like lignin. | Synthesis of lignin esters for improved thermoplasticity [23]. |

| Plasticizers (DMSO, Glycerol) | Reduce melt viscosity of biopolymers for processability in the extruder. | Enabling extrusion of Kraft lignin by preventing excessive torque [23]. |

| Compatibilizers (e.g., PP-g-MA) | Act as an interfacial agent to improve adhesion between immiscible polymer phases. | Reactive compatibilization of plant polysaccharides in polymer blends [21]. |

| Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) | Monomer containing an epoxy ring for grafting, enabling subsequent crosslinking or reaction. | Functionalization of polyolefins (PE-g-GMA) [19]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol REX-EP-01: Esterification of Kraft Lignin with Anhydrides via Reactive Extrusion

Methodology:

This protocol describes the esterification of plasticized Kraft lignin (KL) with succinic or maleic anhydride in a conical, co-rotating twin-screw extruder, adapted from [23].

Materials:

- Kraft Lignin (KL)

- Succinic Anhydride (SA) or Maleic Anhydride (MA)

- Plasticizer: DMSO, glycerol, or ethylene glycol

- Purification agents: Distilled water, sodium bicarbonate

Equipment:

- Twin-screw extruder (e.g., Minilab Rheomex CTW5) with co-rotating screws

- Mortar and pestle

- Vacuum oven

- Balance

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preparation & Plasticization:

- Mill the Kraft lignin with a mortar and pestle.

- Manually mix 7 g of milled KL with a plasticizer (e.g., 25% w/w DMSO) at room temperature until a homogeneous powder is obtained.

Reagent Addition:

- Weigh the appropriate mass of SA or MA (0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 equivalents per average lignin phenylpropane unit, M~178 g/mol) and add it to the plasticized KL. Mix thoroughly.

Reactive Extrusion:

- Pre-heat the extruder to the target temperature (e.g., 140°C).

- Set the screw speed to 60 rpm.

- Feed the KL-plasticizer-anhydride mixture into the extruder hopper.

- Operate the extruder in "direct mode" to collect the reacted extrudate.

Purification:

- Crush the cooled extrudate into a powder using a mortar and pestle.

- Wash the powder with distilled water and a sodium bicarbonate solution for 24 hours under agitation to remove free acid/anhydride residues.

- Recover the purified product via filtration and dry it in air for 24 hours, followed by drying in a vacuum oven at 60°C overnight.

Safety and Monitoring:

- Monitor torque and Specific Mechanical Energy (SME) during extrusion to ensure stable process conditions. SME can be calculated as:

SME (J/kg) = (Screw speed (rpm) × Torque (N·m) × 60) / (Feed rate (kg/h))[23]. - Handle anhydrides (SA, MA) in a fume hood as they can be irritants.

Protocol REX-EP-02: Fabrication of Structural Parts via Robotic Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM)

Methodology:

This protocol outlines the procedure for fabricating and testing mechanical specimens using a robotic REAM system, where a two-part thermoset resin is mixed, deposited, and cured in situ [6].

Materials:

- Part A: Liquid resin (e.g., Bisphenol A-epichlorohydrin epoxy resin)

- Part B: Liquid curing agent (e.g., Poly(oxypropylene) diamine)

- Release agent (e.g., for build plate)

Equipment:

- Robotic REAM system comprising:

- 6-axis robot arm

- Resin dispensing system with precision pumps

- Passive mixing nozzle

- Heated build plate

- Calipers or coordinate measuring machine (CMM)

- Universal mechanical testing machine

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System and Material Setup:

- Calibrate the pumps dispensing Parts A and B to ensure accurate and repeatable flow rates and mixing ratios.

- Apply a release agent to the heated build plate.

- Heat the build plate to the recommended temperature (e.g., 60°C).

Printing Parameters Definition:

- Define the toolpath (e.g., a raster pattern) for the robot arm.

- Set the extrusion rate and the robot's deposition speed. These parameters are interdependent and must be balanced to achieve the desired extrudate size and layer geometry.

- Set the time elapsed between the deposition of consecutive layers.

Printing and In-Situ Curing:

- Initiate the printing process. The resin and hardener are pumped, mixed in the nozzle, and deposited layer-by-layer onto the build plate.

- The exothermic cross-linking reaction cures the resin without the need for an external energy source.

Post-Processing and Metrology:

- After printing, allow the part to cool before removing it from the build plate.

- Measure the final dimensions (e.g., total height, layer width) of the printed part using calipers or a CMM and compare them to the digital model to assess dimensional accuracy.

Mechanical Testing:

- Test printed specimens (e.g., dog-bone shapes) according to ASTM D638 standard on a universal testing machine to determine ultimate tensile strength, Young's modulus, and strain at break.

Key Parameters for Investigation:

- Dimensional Accuracy: Investigate the effect of the time between layers on the total height and layer width of a printed metrology part [6].

- Mechanical Properties: Characterize the effect of extrusion rate and deposition speed on the ultimate tensile strength and Young's modulus of printed tensile specimens [6].

Diagrams and Workflows

REX Experimental Workflow

Lignin Esterification Chemistry

The Relevance of REX in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Material Design

Reactive extrusion (REX) is an emerging continuous process that integrates chemical reactions—such as polymerization, grafting, or cross-linking—with extrusion in a single, efficient step. Within pharmaceutical and biomedical material design, REX offers a solvent-free, scalable, and highly controllable method for synthesizing and engineering advanced drug delivery systems, biodegradable implants, and functional biomaterials, aligning with the principles of Green Chemistry and Process Intensification [24]. This document details specific applications, experimental protocols, and key reagents to facilitate the adoption of REX technologies in research and development.

Application Notes: REX for Advanced Biomaterials

REX has been successfully applied to enhance the properties of various polymers critical to biomedical applications. The following table summarizes key material systems and the improvements achieved through reactive extrusion.

Table 1: REX Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Material Design

| Polymer System | REX Additive/Process | Key Outcome | Relevance to Pharma/Biomedical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) [18] | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) & Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | Elongation at break (12.0% to 61.3%); Plasticizer migration (140.3 mg kgâ»Â¹ to 40.8 mg kgâ»Â¹); Thermal stability (Tdeg from 268.7°C to 333.8°C). | Flexible, safe packaging for medical devices; reduces risk of contaminant migration. |

| PLA [18] | Bio-based plasticizers (e.g., linalyl acetate) & DCP | Elongation at break by >230%; improved thermal/mechanical stability via anchoring. | Sustainable, ductile biomaterials for implantable devices. |

| Starch-Based Biopolymers [25] | Enzymatic hydrolysis (e.g., Amylase, Glucoamylase) post-REX pretreatment | Significant depolymerisation; production of functional hydrolysates, dextrins, oligosaccharides. | Controlled-release drug carriers; encapsulation matrices for APIs. |

| Starch-Based Biopolymers [26] | Phosphorylation (Sodium Trimetaphosphate/Tripolyphosphate) via REX | Production of Resistant Starch (RS) with a high Degree of Substitution (DS). | Functional food additives; potential prebiotic delivery systems for nutraceuticals. |

| Polyurethane (PU) [27] | Functional Silica Nanoparticles (e.g., SiO₂-NH₂/CH₃) in REX 3D Printing | Faster reaction kinetics; Glass transition temperature (Tg); Storage modulus; enhanced cross-linking. | 3D printed, high-strength, custom-fit medical devices and implants. |

The workflow below illustrates the logical progression from REX processing to the final biomedical application.

Biomaterial Development Workflow: The diagram outlines the transformation of raw materials into functional biomaterials via REX and their subsequent biomedical applications.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Enhancing PLA Ductility and Reducing Migration via REX

This protocol details the enhancement of Polylactic Acid (PLA) using PEG-based plasticizers and Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) as a cross-linking agent to create a flexible material with low migration risk, suitable for medical applications [18].

Table 2: Key Processing Parameters for PLA-PEG-DCP Reactive Extrusion

| Parameter | Setting / Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Extruder Type | Twin-Screw Extruder (TSE) | Preferred for superior mixing and reaction efficiency. |

| Temperature Profile | 160°C - 190°C | Gradual increase along the barrel zones. |

| Screw Speed | 100 - 200 rpm | Optimize for sufficient residence time and shear. |

| Polymer Matrix | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Dried before processing (e.g., 80°C for 4 h). |

| Plasticizer | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Molecular weight typically 400-10,000 g/mol. |

| Cross-linker | Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | Typical concentration: 0.1 - 1.0 wt%. |

| Feed Rate | 1 - 5 kg/h | Must be consistent for stable processing. |

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dry PLA pellets in a vacuum oven at ~80°C for at least 4 hours to remove moisture. Pre-mix the dried PLA pellets with the designated weight percentages of PEG plasticizer and DCP cross-linker using a tumbler mixer for 30 minutes to ensure a homogeneous pre-blend.

- REX Processing: Feed the pre-mix into the twin-screw extruder hopper using a gravimetric feeder. Set the extruder's temperature profile along the barrel zones to range from 160°C at the feed throat to 190°C at the die. Set the screw speed to 150 rpm as a starting point. The exothermic reaction will occur within the extruder barrel.

- Pelletization & Shaping: As the molten, reacted material exits the die, pass the extrudate through a water-cooling bath and into a pelletizer to form uniform granules.

- Film Preparation (Optional): For film production, the pellets can be processed by compression molding or blown film extrusion using standard equipment and settings for PLA.

Protocol: REX-Based 3D Printing of Polyurethane for Medical Devices

This protocol outlines the use of Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM) for processing polyurethane (PU), enabling the fabrication of complex, functional medical devices [27].

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Prepare two separate feed components. Feed A contains the polyol mixture (e.g., polyether polyol). Feed B contains the isocyanate (e.g., methylene diphenyl diisocyanate, MDI). Incorporate rheological modifiers (e.g., fumed silica) or functional silica nanoparticles (SiO₂-NH₂/CH₃) into one or both feeds as required to achieve the desired viscosity and printing performance.

- System Setup & Calibration: Mount the two feedstock reservoirs onto the REAM system. Connect the feeds to a static mixing nozzle via precision pumps. Calibrate the pump flow rates to ensure the correct stoichiometric ratio (typically 1:1) between the isocyanate and polyol groups is maintained during printing.

- Printing Process: Initiate the printing process. The two reactive components are pumped into the mixing nozzle where they are combined. The mixed material is then extruded and deposited layer-by-layer according to the CAD model. The exothermic reaction between the components leads to curing and solidification of the PU in situ, without the need for external energy sources.

- Post-Processing: Depending on the specific PU system, a short post-curing step at elevated temperature (e.g., 60-80°C for 1-2 hours) may be applied to ensure complete reaction and optimal mechanical properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials and their functions for conducting REX experiments in a pharmaceutical or biomedical context.

Table 3: Key Reagents for REX in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in REX Process | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biodegradable, biocompatible polymer matrix. | Primary material for implants, drug delivery systems, and medical packaging [18]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Plasticizer to improve flexibility and processability. | Increases ductility of PLA; reduces brittleness [18]. |

| Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | Free radical initiator for cross-linking. | Anchors plasticizer to polymer chain, reducing migration and enhancing stability [18]. |

| Functional Silica Nanoparticles (e.g., SiOâ‚‚-NHâ‚‚) | Reactive filler to reinforce polymer matrix. | Enhances mechanical strength and thermal properties of 3D printed polyurethane [27]. |

| Sodium Trimetaphosphate (STMP) | Cross-linking agent for starch phosphorylation. | Produces resistant starch with modified digestibility for nutraceutical carriers [26]. |

| Amylolytic Enzymes (e.g., α-Amylase) | Biocatalyst for polymer degradation. | Post-REX hydrolysis of starch to create defined oligosaccharides or molecular weight profiles [25]. |

| Polyol & Isocyanate Feeds | Reactive components for polyurethane synthesis. | In-situ formation of PU during REX or REAM for custom medical devices [27]. |

| Sipatrigine | Sipatrigine, CAS:130800-90-7, MF:C15H16Cl3N5, MW:372.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SirReal2 | SirReal2, MF:C22H20N4OS2, MW:420.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The complex interplay between REX processing parameters and final material properties is governed by underlying chemical and physical principles, as shown in the following mechanistic diagram.

REX Mechanistic Principles: This diagram depicts how reactive extrusion inputs drive various chemical reactions to tailor final material properties.

REX Methodologies and Applications in Drug Delivery and Biomaterials

Reactive extrusion (REX) is a continuous processing technology that combines traditional extrusion with chemical reactions, serving as an efficient chemical reactor for polymer synthesis and modification. Within the context of biopolymer research, REX offers a solvent-free, continuous, and economically viable platform for producing and modifying sustainable materials. The process leverages the thermomechanical energy of the extruder to facilitate reactions such as polymerization, grafting, compatibilization, and depolymerization, significantly reducing reaction times from hours to mere minutes [1] [5]. For researchers focused on sustainable materials, REX enables the valorization of biomass like lignin and starch, the enhancement of biopolymer properties like Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), and the creation of wholly green composites for applications ranging from packaging to biomedical devices [28] [5] [29]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for key REX processes involving biopolymers, functional additives, and lignin.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from recent research on reactive extrusion of biopolymers and biomass, providing a reference for parameter selection and expected outcomes.

Table 1: Key Processing Parameters and Outcomes in Biomass/Biopolymer Reactive Extrusion

| Process Focus | Temperature Profile (°C) | Screw Speed (rpm) | Residence Time | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sawdust Depolymerization | 275 - 375 | 100 - 200 | < 2 minutes | 6.5-7.5% biochemical yield in liquid phase | [5] |

| Starch Esterification (CA/TA) | 100 (all zones) | 60 | 2-3 minutes | Degree of Substitution: 0.023 - 0.365 | [30] |

| PLA Melt Blending | 170 - 230 (Typical range) | Varies | Minutes | Standard processing range for PLA composites | [31] [29] |

Table 2: Material Property Changes via Reactive Extrusion and Compounding

| Material System | Additive/Modifier | Key Property Change | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Lignin Nanoparticles (10%) | Tensile Strength: Decreased ~82% (untreated lignin) | [29] |

| PLA | Maleic Anhydride (REX) | Improved tensile strength, impact resistance, thermal stability | [1] |

| Cassava Starch | 20% Citric Acid (REX) | Water Holding Capacity: Increased to 870% | [30] |

| Kraft Lignin + PVA | TOFA & Citric Acid (REX) | Tensile Strength: 8.7 MPa; Tensile Modulus: 59.3 MPa | [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Reactive Extrusion Processes

Protocol: Reactive Extrusion of Sawdust for Biochemical Production

This protocol describes a continuous, solvent-free method for the thermomechanical depolymerization of Pinus radiata sawdust to produce a biochemical-rich liquor, adapted from [5].

- Objective: To continuously produce oligomeric and monomeric biochemicals (e.g., acetic acid, methanol, furanics, phenolic compounds) from lignocellulosic biomass.

- Materials:

- Feedstock: Pinus radiata sawdust, sieved to < 3 mm particle size.

- Moisture Content Adjustment: Deionized water.

- Process Gas: High-purity nitrogen.

- Equipment:

- Co-rotating twin-screw extruder (e.g., with L/D ratio of 40).

- Screw configurations with kneading elements.

- Nitrogen purge system for inert atmosphere.

- Liquid separation system (cyclone/condenser) at the die exit.

- Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Adjust the moisture content of the sieved sawdust to 50% (w/w) by adding deionized water and mixing thoroughly.

- Extruder Setup:

- Set barrel temperature profile to achieve a reaction zone temperature between 325°C and 375°C.

- Configure the screw with kneading elements to ensure high shear and efficient mixing.

- Purge the barrel with nitrogen to maintain an inert atmosphere and prevent oxidation.

- Processing:

- Feed the prepared sawdust into the extruder at a consistent feed rate.

- Set screw speed between 100-200 rpm (note: speed has minimal effect on composition).

- Maintain processing until steady state is achieved.

- Product Collection:

- Collect the hot vapor-liquid mixture exiting the die.

- Separate the liquid phase (biochemical-rich liquor) using a cyclone or condenser system.

- The solid residue (primarily cellulose) is expelled separately.

- Analysis:

- Liquor Analysis: Characterize using GC-MS for organic acids (acetic acid), furans, and phenolic compounds.

- Solid Residue Analysis: Use TGA, XRD, or SEM to determine morphological and chemical changes.

Protocol: Citric Acid Crosslinking of Starch Hydrogels via Reactive Extrusion

This protocol outlines the production of esterified and crosslinked starch hydrogels using food-grade organic acids, based on [30].

- Objective: To synthesize crosslinked starch hydrogels with enhanced water retention capacity using citric acid (CA) as a crosslinker.

- Materials:

- Biopolymer: Cassava starch.

- Crosslinkers: Citric acid (CA) or Tartaric acid (TA), analytical grade.

- Plasticizer: Glycerol (optional, for enhanced processing).

- Solvent: Deionized water.

- Equipment:

- Single or twin-screw extruder (L/D ratio of 40).

- Oven for drying (45°C).

- Grinder and sieve (80-mesh).

- Procedure:

- Premix Preparation:

- Dissolve citric acid in distilled water to achieve concentrations of 2.5 - 20.0% (g acid/100 g starch).

- Mix the CA solution with native cassava starch to a final moisture content of 32% (w/w).

- Seal the mixture in plastic bags and equilibrate for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Reactive Extrusion:

- Set all extruder barrel zones to 100°C.

- Set screw speed to 60 rpm.

- Feed the premixed material into the extruder.

- Collect the extruded strands.

- Post-Processing:

- Air-dry the extrudates at 45°C to a constant weight.

- Grind the dried material and wash three times with absolute ethanol to remove unreacted acid.

- Dry again at 45°C, grind, and sieve through an 80-mesh sieve.

- Premix Preparation:

- Analysis:

- Degree of Substitution (DS): Determine by titration [30].

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Confirm ester bond formation by identifying the carbonyl (C=O) stretch peak at ~1730 cmâ»Â¹.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Assess changes in crystallinity.

- Water Holding Capacity (WHC): Measure the swelling capacity in water.

Protocol: Enhancing PLA Performance via Reactive Extrusion and Lignin Compatibilization

This protocol describes the use of REX and compatibilization strategies to incorporate lignin into PLA, creating composites with improved sustainability and functionality [28] [1] [29].

- Objective: To manufacture PLA/lignin composites with enhanced UV barrier, antioxidant properties, and reduced cost, while mitigating inherent brittleness.

- Materials:

- Matrix Polymer: Polylactic acid (PLA) resin.

- Reinforcement/Filler: Lignin (Kraft, Organosolv, or lignin nanoparticles).

- Compatibilizers/Modifiers: Maleic anhydride, plasticizers (e.g., PEG), or pre-modified lignin (e.g., TOFA-esterified lignin [32]).

- Equipment:

- Twin-screw extruder (co-rotating preferred).

- Injection molding machine or hot press.

- Standard mechanical testing equipment (tensile tester, impact tester).

- Procedure:

- Pre-Drying: Dry PLA and lignin in an oven (e.g., 60°C for PLA, 105°C for lignin) for at least 4 hours to remove moisture.

- Premixing: Pre-mix PLA, lignin (typical loadings 5-15 wt%), and compatibilizer (e.g., 2-5 wt%) in a tumbler mixer.

- Reactive Extrusion:

- Set extruder temperature profile according to PLA's processing window (170-230°C).

- Configure screw design for high shear mixing (incorporating kneading blocks).

- Feed the premix into the extruder.

- Collect, water-cool, and pelletize the extruded strand.

- Specimen Preparation: Injection mold or compression mold the pellets into standard test specimens (e.g., ASTM dog-bone tensile bars).

- Analysis:

- Mechanical Testing: Tensile strength, modulus, and elongation at break.

- Thermal Analysis (TGA/DSC): Determine thermal stability, glass transition temperature (Tg), and crystallization behavior.

- Spectroscopy (FTIR): Investigate potential chemical interactions between PLA and lignin.

- Morphology (SEM): Assess lignin dispersion and interfacial adhesion within the PLA matrix.

Process Visualization and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow and chemical pathways for key reactive extrusion processes described in the protocols.

Diagram 1: Reactive Extrusion Workflow for Biopolymer and Biomass Processing

Diagram 2: Biomass Conversion and Composite Synthesis Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Reactive Extrusion Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Reactive Extrusion | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Primary matrix biopolymer; provides compostable backbone for composites. | Manufacturing of biodegradable packaging, 3D printing filaments [28] [31]. |

| Kraft Lignin / Organosolv Lignin | Multifunctional bio-based filler; provides UV barrier, antioxidant properties, and reinforcement. | Reducing cost and enhancing functionality of PLA composites [28] [29] [32]. |

| Citric Acid (CA) | Eco-friendly crosslinking and esterifying agent for hydroxyl-rich biopolymers. | Production of starch hydrogels with high water retention [30]. |

| Maleic Anhydride | Compatibilizer; grafts onto polymer chains to improve interfacial adhesion in blends. | Enhancing mechanical properties of PLA composites via reactive extrusion [1]. |

| Tall Oil Fatty Acid (TOFA) | Modifying agent for lignin; introduces long hydrophobic chains via esterification. | Improving compatibility and flexibility of lignin in polymer matrices [32]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Water-soluble polymer matrix; can be crosslinked to form biodegradable films and composites. | Creating synergistic biocomposites with modified lignin [32]. |

| Glycerol | Plasticizer; reduces intermolecular forces, increases flexibility and processability. | Plasticizing starch or other biopolymers during extrusion [32]. |

| Sisomicin | Sisomicin, CAS:32385-11-8, MF:C19H37N5O7, MW:447.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sitravatinib | Sitravatinib, CAS:1123837-84-2, MF:C33H29F2N5O4S, MW:629.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Reactive extrusion (REX) integrates chemical synthesis and material processing within a single, continuous operation, typically in a twin-screw extruder. This process represents a significant advancement in polymer manufacturing, pharmaceutical production, and material science, offering enhanced efficiency, superior product uniformity, and reduced environmental impact compared to traditional batch methods [33] [8]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for executing a reactive extrusion process, framed within research on reactive processing methods. It is structured to guide researchers and drug development professionals through the critical stages from feedstock preparation to final shaping and devolatilization, complete with quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools.

The reactive extrusion process is a continuous sequence of events where material is simultaneously conveyed, mixed, reacted, and formed. Figure 1 illustrates the logical flow of this entire process, from the initial handling of raw materials to the final product stage.

Figure 1. Logical workflow of the reactive extrusion process.

Stage 1: Feedstock Preparation

Objective

To prepare and characterize all raw materials—including polymers, monomers, reagents, and additives—to ensure they meet the specific physical and chemical requirements for a successful reactive extrusion process.

Detailed Protocol

Material Selection and Characterization:

- Polymers/Monomers: Select based on the target molecular structure and properties of the final product. For polymer blending or functionalization, common choices include poly(ethylene-co-acrylic acid) (PEAA) or polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [33] [34].

- Reactive Agents: Choose agents appropriate for the intended reaction (e.g., chain extension, grafting, cross-linking). Pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) is an effective chain extender for PET, while Oxone can be used for solid-state oxidation reactions [33] [34].

- Additives: Incorporate fillers (e.g., short carbon fibers for reinforcement [35]), viscosity modifiers, or stabilizers as required by the application.

Pre-mixing and Pre-treatment:

- Dry Blending: For multi-component formulations, pre-mix solid powders and granules in a tumbler or high-speed mixer to achieve an initial homogeneity. This reduces the mixing burden inside the extruder.

- Drying: Many polymers, such as PET, are hygroscopic and must be dried before processing to prevent hydrolysis, which degrades molecular weight. Use a desiccant dryer at a specified temperature and time (e.g., 120-160°C for 3-5 hours for PET) to achieve a moisture content below 50 ppm [34].

- Fiber Pre-dispersion: For composite materials, short fibers can be pre-mixed with the resin in a specified weight ratio (e.g., 1:9 fibers to resin) [35]. Note that intense mixing will degrade fiber length, so a balance between dispersion and fiber integrity must be found.

Key Parameters & Data

Table 1. Common Feedstock Materials and Their Properties

| Material Category | Example | Key Property / Target | Relevance to REX |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Resin | EPON 8111 Epoxy | Low viscosity, fast gel time (~60 s) [35] | Enables shape retention post-deposition. |

| Chain Extender | Pyromellitic Dianhydride (PMDA) | Rebuilds polymer chains; added at ~1% concentration [34] | Increases melt viscosity for processing degraded/recycled polymers. |

| Solid Oxidant | Oxone | Stable solid peroxygen for solvent-free reactions [33] | Enables green oxidative transformations (e.g., quinone formation). |

| Reinforcement | Chopped Carbon Fibers | ~7µm diameter, initial length up to 3 mm [35] | Enhances mechanical properties like strength and stiffness. |

| Viscosity Modifier | Fumed Silica | High static viscosity, shear yield strength [35] | Imparts shape stability upon deposition for additive manufacturing. |

Stage 2: Feeding and Conveying

Objective

To accurately and consistently meter prepared feedstocks into the extruder inlet at a predetermined ratio and rate, initiating the material's transport along the barrel.

Detailed Protocol

Equipment Setup:

- Utilize volumetric or gravimetric (loss-in-weight) feeders. Gravimetric feeders are preferred for their higher accuracy, especially with minor additive components.

- For multi-stream reactive systems (e.g., resin and hardener), use separate feeders for each component that converge at the extruder throat or at an intermediate feed port [35] [8].

Process Execution:

- Calibrate each feeder for the specific material it will handle, accounting for bulk density and flowability.

- Set the feed rate (kg/hr) for each component according to the formulated recipe. The total feed rate is a primary determinant of the material's residence time inside the extruder.

- Initiate feeding, monitoring feeder performance continuously to ensure stable and consistent mass flow.

Stage 3: Mixing and Reaction

Objective

To homogenize the various components thoroughly and provide the necessary mechanical energy and thermal environment to initiate and complete the desired chemical reaction.

Detailed Protocol

Extruder Configuration:

- Screw Design: Configure the twin screws with a sequence of conveying, mixing, and kneading elements. Kneading blocks are crucial for generating high shear to disperse fillers and initiate mechanochemical reactions [33] [8].

- Barrel Temperature Profile: Set a precise temperature profile along the barrel zones. The temperature must be controlled to favor reaction kinetics without degrading the material. For example, PET chain extension typically occurs between 270-290°C [34].

Process Monitoring and Control:

- Screw Speed: Adjust the screw speed (RPM) to control the shear rate and mixing intensity. Higher speeds generally improve mixing but reduce residence time and can degrade shear-sensitive materials (e.g., breaking carbon fibers) [35].

- Residence Time: Ensure the average residence time (typically seconds to minutes) is sufficient for the reaction to reach the desired conversion. This is influenced by screw speed, screw design, and feed rate.

- Torque Monitoring: Monitor the motor torque, as a significant increase can indicate a viscosity rise due to cross-linking or chain extension, while a drop may signal polymer degradation.

Key Parameters & Data

Table 2. Critical Reaction Parameters and Their Effects

| Parameter | Typical Range / Example | Impact on Process & Product | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw Speed | 40 - 400 RPM | Higher speed = more shear, better mixing, shorter residence time, potential fiber breakage [35] [33]. | Directly controls mechanical energy input. |

| Reaction Temp. | 90°C (Oxone reaction) to 290°C (PET) [33] [34] | Governs reaction rate and conversion; prevents premature curing or degradation. | Must be optimized for specific reaction chemistry. |

| Residence Time | A few seconds to minutes [33] | Must be longer than the reaction initiation time for high conversion. | Determines time available for reaction completion. |

| Viscosity Change | PET: 150 Pa·s to >350 Pa·s with 1% PMDA [34] | Direct in-line indicator of reaction progress (e.g., chain extension). | Confirms effectiveness of reactive extrusion. |

Stage 4: Devolatilization

Objective

To remove volatile by-products, residual solvents, moisture, or unreacted monomers from the polymer melt before it exits the extruder, ensuring the quality and stability of the final product.

Detailed Protocol

Vent Port Configuration:

- Open one or more vent ports along the extruder barrel in zones where the melt is fully formed but the reaction is largely complete.

- Apply a vacuum to these ports (typically 25-29 in Hg) to actively draw out volatiles. Multiple vent stages can be used for more thorough removal [36].

Process Execution:

- The melt seal formed by the screw elements before the vent port prevents pressure loss and ensures the vacuum is effectively applied to the melt.

- The intense mixing in the devolatilization zone creates surface renewal, exposing fresh melt to the vacuum and enhancing removal efficiency [36].

- The extracted volatiles are condensed and collected for disposal or recovery.

Stage 5: Shaping and Final Product

Objective

To pressurize the devolatilized and reacted melt and force it through a die to impart the final shape, followed by cooling to solidify the product.

Detailed Protocol

Melt Pumping:

- The final screw sections and a gear pump (if equipped) build pressure to push the melt through the die.

- A gear pump provides precise and pulsation-free flow, which is critical for maintaining consistent product dimensions (e.g., in film production [34]).

Die Design and Cooling:

- The die is selected based on the desired product form: sheet die for film, strand die for pellets, profile die for specific shapes.

- Immediately after the die, the product is cooled using calibrated rolls (for film), a water bath (for strands), or air knives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Materials for Reactive Extrusion Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Reactive Extrusion | Research Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pyromellitic Dianhydride (PMDA) | Chain extender; reacts with end groups of polymers like PET to increase molecular weight and melt viscosity [34]. | Recycling and upcycling of thermoplastics; viscosity restoration of degraded PET [34]. |

| Oxone | Solid oxidant; enables solvent-free mechanochemical oxidation reactions within the extruder [33]. | Green synthesis of quinones from lignin-derived aromatics; oxidative degradation of contaminants [33]. |

| Short Carbon Fibers | Reinforcement filler; enhances mechanical properties (stiffness, strength) of the composite material [35]. | Manufacturing of high-performance thermosetting and thermoplastic composites via additive manufacturing or compounding [35]. |

| Fumed Silica | Rheological modifier; imparts shear yield strength and shape stability to the extrudate [35]. | Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM) to prevent sagging and maintain print resolution [35]. |

| Epoxy Resin/Hardener | Highly reactive thermosetting system; gels and cures rapidly after mixing and deposition [35]. | Studying REAM processes for composites, focusing on inter-layer bonding and cure kinetics [35]. |

| SJ-172550 | SJ-172550, CAS:431979-47-4, MF:C22H21ClN2O5, MW:428.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SP-Chymostatin B | SP-Chymostatin B, CAS:70857-49-7, MF:C30H41N7O6, MW:595.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Visualization: Active Mixing REAM System

For Reactive Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (REAM) with high-viscosity feedstocks, an active mixer is often essential. Figure 2 details the components of such a system, which decouples mixing efficacy from extrusion rate.

Figure 2. Schematic of an active mixing REAM system for high-viscosity composites.

Reactive extrusion (REx) is an emerging green processing technology that shows significant promise for the efficient and sustainable production of biomaterials. Within the context of a broader thesis on reactive extrusion processing methods, this application note highlights its specific utility in fabricating pH-sensitive polysaccharide and lignin hydrogels for advanced drug delivery applications. REx offers a continuous, solvent-free process that combines thermomechanical energy to disintegrate native biopolymer structures while simultaneously facilitating chemical reactions, such as esterification and cross-linking, in a single step with typical reaction times of only 2-3 minutes [30]. This method presents a commercially viable alternative to traditional batch synthesis, minimizing effluent generation and reducing excessive reagent use [30].