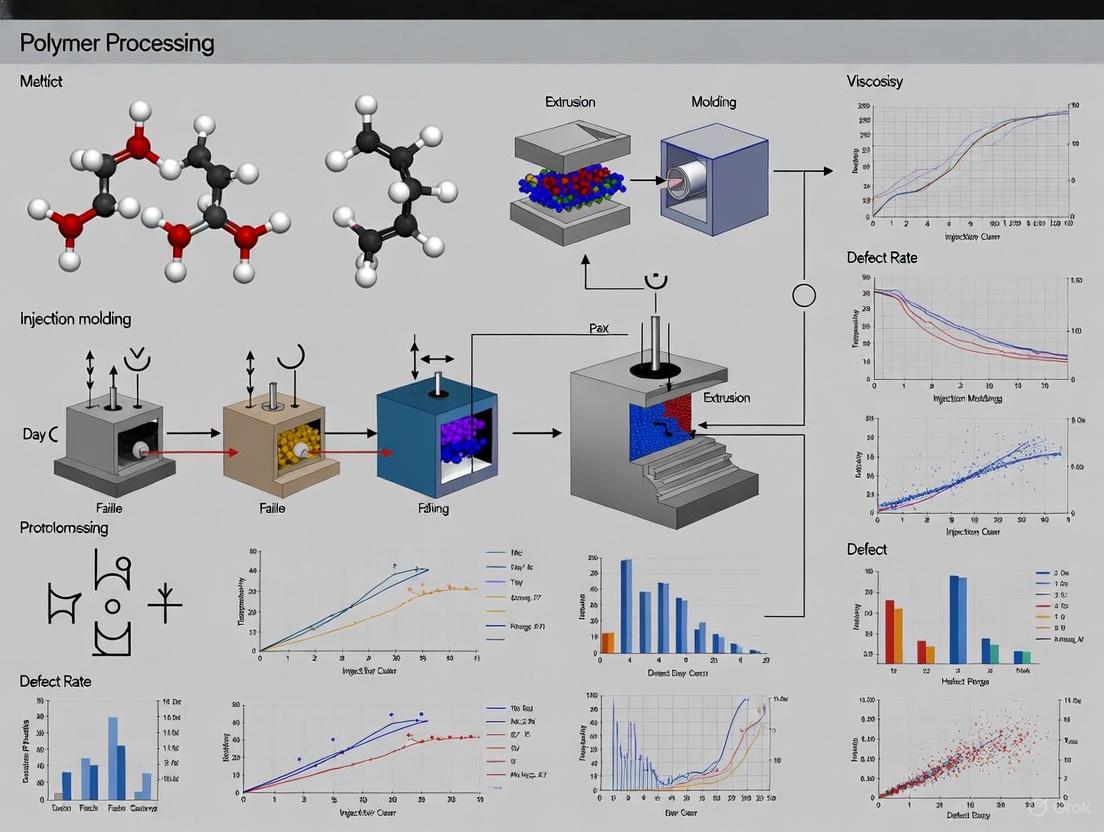

Solving Polymer Processing Defects: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address polymer processing defects.

Solving Polymer Processing Defects: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address polymer processing defects. It covers the fundamental science behind common defects, advanced analytical methodologies for root cause analysis, AI-driven optimization techniques for troubleshooting, and robust validation protocols. By integrating foundational knowledge with cutting-edge optimization and validation strategies, this guide aims to enhance process efficiency, ensure product quality, and support the development of reliable biomedical polymer products, from drug delivery systems to medical devices.

Understanding the Root Causes of Polymer Processing Defects

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is polymer melt rheology and why is it critical in processing? Polymer melt rheology is the study of how polymer materials deform and flow under applied forces. Polymer melts are viscoelastic, meaning they exhibit both viscous (liquid-like) and elastic (solid-like) behaviors [1]. Understanding rheology is critical because it directly determines a material's processability, influencing factors like flow resistance, heat generation, and the final product's dimensional stability and mechanical properties [1] [2]. The viscous characteristics are often described by viscosity, which changes with shear rate (a phenomenon known as shear thinning), while the elastic characteristics can lead to phenomena like die swell [1].

Q2: How does molecular structure affect a polymer's flow and final properties? The molecular structure of a polymer is a fundamental dictator of its rheological behavior.

- Molecular Weight (Mw) and Distribution (MWD): Higher molecular weights generally lead to higher melt viscosity. Above a critical molecular weight where chains begin to entangle, the zero-shear viscosity (η₀) is proportional to Mw to the power of ~3.4 [1]. The Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) affects how sharply the viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate (shear thinning); polymers with a broader MWD tend to thin more at lower shear rates [1] [2].

- Long-Chain Branching (LCB): The presence of long-chain branches significantly increases a polymer's melt elasticity and its resistance to extensional flow (a property known as strain hardening) [1]. This is crucial for processes like blow molding and film blowing.

Q3: What is the "shark-skin effect" and what causes it? The shark-skin effect is a specific type of melt fracture and surface defect where the extruded product develops a regular, fine, rippled surface that resembles shark skin [3] [4]. It is a flow instability caused when the molten polymer is subjected to high shear stress as it exits the die [3]. This defect is directly related to the material's rheological properties and can be exacerbated by high extrusion speeds, poor die design, or the use of high molecular weight polymers [3] [4].

Q4: My medical device component has visible flow lines. What are these likely to be? The visible lines are most likely weld lines (also known as knit lines) [5]. These form when two or more flow fronts of molten polymer meet and do not fuse together perfectly within the mold cavity. This often happens when the flow splits around a core, pin, or other obstacle in the mold. While sometimes only a cosmetic issue, weld lines can also create structural weaknesses in the part [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Defects and Solutions

Defect: Melt Fracture (Including Shark-Skin)

| Aspect | Description & Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Surface roughness ranging from fine ripples (sharkskin) to severe irregular distortions [3]. | |

| Primary Causes | High extrusion rates, poor die design (sharp transitions), high molecular weight polymers, inadequate temperature control [3]. | • Reduce extrusion rate to lower shear stress [3].• Optimize die temperature to lower viscosity [3].• Improve die design for smoother flow (e.g., longer land length, gradual transitions) [3].• Consider switching to a polymer with a lower molecular weight or narrower MWD [3] [2].• Use processing aids (e.g., fluoropolymer additives) to reduce surface friction [3]. |

Defect: Weld Lines

| Aspect | Description & Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | A visible line or seam on the surface where separate flow fronts met [5]. | |

| Primary Causes | Molten plastic flowing around obstacles (e.g., pins, cores) in the mold cavity and failing to fuse fully upon meeting [5]. | • Modify part design to alter flow paths and avoid flow obstacles [5].• Increase melt and/or mold temperature to keep polymer fluid for longer, promoting better fusion [5].• Optimize gate placement to change the location where flow fronts meet [5].• Adjust injection speed and pressure to ensure robust flow front merging [5]. |

Defect: Sink Marks

| Aspect | Description & Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Surface depressions or indentations, often in thicker sections of the part [5]. | |

| Primary Causes | Differential cooling, where the outer surface solidifies while the inner material is still cooling and contracting, pulling the surface inward [5]. | • Optimize part design for uniform wall thickness [5].• Increase injection pressure and hold time to pack more material into the cavity during cooling [5].• Adjust mold temperature to allow for a more uniform cooling rate [5].• Consider using a material with a filler (e.g., glass-filled nylon) to reduce shrinkage [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Rheological Analysis

Protocol 1: Oscillatory Frequency Sweep for Viscosity Profile

Purpose: To characterize the shear rate-dependent viscosity and viscoelastic properties of a polymer melt, providing data that can be linked to molecular structure (Mw, MWD, LCB) [2].

Methodology:

- Instrument Setup: Use a rotational shear rheometer equipped with parallel plate geometry and precise temperature control (e.g., electric heating hood) [2].

- Specimen Preparation: Place polymer pellets directly between the pre-heated plates of the rheometer. Melt the pellets to form a disk-shaped specimen with a consistent gap (e.g., 0.75 mm) [2].

- Test Parameters:

- Mode: Small-amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS).

- Strain: A low, fixed strain (e.g., 0.1%) to ensure measurements are within the linear viscoelastic region [2].

- Frequency Range: Typically from 100 to 0.1 rad/s, collecting multiple data points per frequency decade [2].

- Temperature: Set to a standard processing temperature (e.g., 190°C for polyolefins) [2].

- Data Interpretation: Apply the Cox-Merz rule, which equates complex viscosity (|η*|) versus angular frequency (ω) to steady-state shear viscosity versus shear rate [1] [2]. Analyze the zero-shear viscosity plateau for molecular weight and the slope of the shear-thinning region for molecular weight distribution [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Melt Flow Index (MFI) Measurement

Purpose: To provide a single-point assessment of a polymer's flowability under specific conditions, widely used for quality control [6] [2].

Methodology:

- Instrument Setup: Use a Melt Flow Indexer conforming to ASTM D1238 or ISO 1133 standards [6].

- Specimen Preparation: Load the polymer resin (in pellet or powder form) into the barrel of the apparatus.

- Test Parameters:

- Procedure: The piston is charged with the specified weight after a pre-heating period. The extrudate is cut at timed intervals, and the output is measured [6].

- Data Interpretation: The Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) is reported in grams per 10 minutes. A high MFR indicates low viscosity and high flowability, and vice versa [6] [2].

Viscosity Profiles of LLDPE Samples with Identical MFI

The table below demonstrates why single-point MFI measurements can be insufficient, as three LLDPE samples with nearly identical MFI and average molecular weight (Mw) showed significantly different viscosity profiles under a range of shear conditions [2].

| Sample | MFI (g/10 min) | Mw (kg/mol) | MWD | Zero-Shear Viscosity (Pa·s) | Viscosity at ~100 rad/s (Pa·s) | Key Rheological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLDPE #1 | 0.920 | 106 | Medium | Did not plateau (very high) | ~500 | Continuous shear thinning, wider MWD [2] |

| LLDPE #2 | 0.916 | 106 | Medium | Did not plateau (very high) | ~400 | Most shear-thinning, widest apparent MWD [2] |

| LLDPE #3 | 0.918 | 106 | Narrow | ~20,000 | ~1,800 | Clear Newtonian plateau, narrowest MWD [2] |

Data adapted from [2], comparing three LLDPE samples. The viscosity values are approximate, extracted from the provided rheology curves.

Common Defects and Their Rheological Roots

| Defect | Typical Appearance | Primary Rheological & Process Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Melt Fracture | Rough, distorted surface (sharkskin, washboard) [3] | High shear stress, viscoelastic instability, high molecular weight [3] |

| Weld Lines | Visible seam on the part surface [5] | Incomplete fusion of polymer flow fronts, low melt temperature [5] |

| Sink Marks | Surface depressions, often in thick sections [5] | Excessive volumetric shrinkage after cooling, insufficient packing pressure [5] |

| Splay (Silver Streaks) | Light or white streaks on the surface [5] | Moisture in the resin or polymer degradation from excessive shear heat [5] |

Research Workflow: From Rheology to Defect Solution

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for using rheological analysis to diagnose and solve polymer processing defects.

Workflow for Defect Resolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational Rheometer | Measures viscous and elastic properties (G', G") of polymer melts under oscillatory or steady shear [2]. | Performing frequency sweeps to build a full viscosity profile and determine molecular weight distribution [2]. |

| Capillary Rheometer | Measures apparent viscosity at high shear rates, simulating conditions in extrusion or injection molding [1]. | Studying shear thinning behavior and detecting flow instabilities like melt fracture at process-relevant rates [1]. |

| Melt Flow Indexer | Provides a quick, single-point measurement of polymer flow under a specified load and temperature [6]. | Quality control checks to ensure batch-to-batch consistency of raw polymer resins [6]. |

| Processing Additives | Chemical additives that modify interfacial or bulk properties to improve processing [3]. | Fluoropolymer-based processing aids are used to reduce surface friction and eliminate sharkskin defects [3]. |

| Nanofillers (e.g., Graphene Nanoplatelets) | Reinforce the polymer matrix and can alter its rheological behavior [4]. | Adding GNPs to ABS to increase stiffness and modulus, but requiring process optimization to manage increased viscosity [4]. |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides for researchers addressing critical defects in biomedical polymer processing. Effective management of sharkskin, voids, and warpage is essential for manufacturing devices and components with the required structural integrity, dimensional accuracy, and surface quality. The following FAQs, grounded in current research, offer detailed methodologies and solutions to support your experimental work.

Troubleshooting FAQ

What causes sharkskin defect in extrusion, and how can it be eliminated?

Sharkskin, or surface melt fracture, is a surface defect where the extrudate develops a rough, wavy, or rippled appearance, resembling shark skin. This is particularly detrimental in biomedical applications like catheter tubing or film for sterile packaging, where smooth surfaces are critical [7].

- Primary Cause: The defect arises from instabilities at the polymer-die wall interface. As the polymer melt exits the die, it experiences a sudden pressure drop and rapid velocity increase. If the melt adheres strongly to the die wall (high wall shear stress), the surface layer undergoes excessive stretching, leading to periodic rupturing and tearing [7].

- Typical Conditions: Sharkskin occurs when shear stress exceeds a critical limit (often ~0.1–0.3 MPa), particularly with high extrusion speeds, and in high-viscosity or linear polymers like LLDPE and PP [7].

Experimental Protocol: Mitigating Sharkskin with PFAS-Free Processing Aids

- Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of sustainable, fluorine-free polymer processing aids (PPAs) in eliminating sharkskin during the extrusion of polyolefins.

- Materials:

- Base polymer (e.g., medical-grade PP or LLDPE).

- PFAS-free PPA (e.g., SILIMER series or equivalent).

- Methodology:

- Preparation: Dry-blend the base polymer with the recommended concentration of PPA (e.g., 0.5-1.0% by weight).

- Extrusion: Process the mixture using a single or twin-screw extruder fitted with a capillary die.

- Analysis:

- Visual Inspection: Examine the surface of the extrudate for roughness using optical microscopy or laser scanning.

- Shear Stress Monitoring: Record pressure data upstream of the die to calculate the wall shear stress. Note the critical shear rate at which sharkskin appears with and without the PPA.

- Throughput Measurement: Measure the extrusion rate to quantify any increase in throughput facilitated by the PPA.

- Expected Outcome: The PPA migrates to the die wall, reducing surface energy and facilitating polymer slip. This results in a smoother extrudate surface, allows for a higher critical shear rate before defect onset, and increases output [7].

Why do voids form in molded biomedical components, and how can they be prevented?

Voids are empty pockets or spaces inside a molded part that can severely compromise structural strength and lead to unexpected failure, a critical concern for load-bearing implants or surgical instruments [8].

- Primary Cause: Voids are primarily caused by material shrinkage during cooling or improper venting that traps air. Inadequate packing pressure can also prevent the material from fully occupying the mold cavity [8]. In plant fiber-reinforced composites, voids form due to mechanical air entrapment, moisture, and poor resin impregnation into the fibrous structure [9].

- Identification: While not always visible externally, voids can be detected non-destructively using techniques like ultrasonic C-scan, which reveals internal defects through color mapping [9].

Experimental Protocol: Minimizing Voids via Hot Press Curing Optimization

- Objective: To determine the optimal curing pressure and temperature to minimize void content in a fiber-reinforced polymer composite laminate.

- Materials:

- Reinforcement (e.g., unidirectional flax fabric, glass fiber mat).

- Thermoset resin (e.g., Epoxy 618 based on bisphenol-A).

- Curing and accelerating agents (e.g., MeTHPA, DMP-30).

- Methodology:

- Layup: Stack pre-impregnated plies in a mold.

- Curing: Process the laminate in a hot press. Systematically vary the curing pressure (e.g., 1, 2, 3 bar), curing temperature (e.g., 100°C, 120°C, 140°C), and time.

- Analysis:

- Void Content: Use optical microscopy on cross-sectional samples to quantify void content, shape, and distribution.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform short beam shear (ILSS) and tensile tests on specimens with different void contents.

- Expected Outcome: Higher curing pressures generally reduce void content and shift void shape from elongated to more spherical. A strong inverse correlation between void content and mechanical properties like interlaminar shear strength (ILSS) is typically observed [9].

What are the root causes of warpage in molded parts, and how is it corrected?

Warpage is the distortion of a part from its intended shape due to non-uniform shrinkage, leading to catastrophic failure to meet dimensional tolerances in precision components [10] [11].

- Primary Cause: Warpage results from anisotropic (non-uniform) shrinkage, which creates internal residual stresses that are relieved upon ejection from the mold [11]. In thermoforming, warpage is caused by the relaxation of unevenly distributed residual (frozen-in) stresses accumulated during the forming process [10].

- Three Main Factors:

- Orientation Effects: Differential shrinkage between the flow and cross-flow directions due to molecular or fiber orientation.

- Area Shrinkage: Variation in shrinkage throughout the part, often influenced by wall thickness and distance from the gate.

- Differential Cooling: Different cooling rates on the two sides of the mold create a stress gradient through the part's thickness [11].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected causes of warpage and the primary strategies to address them.

Experimental Protocol: Predicting and Solving Warpage via Simulation

- Objective: To use injection molding simulation software to identify the root cause of warpage in a part and test solutions virtually.

- Materials:

- CAD model of the part and mold.

- Injection molding simulation software (e.g., Moldflow, Moldex3D).

- Material database for the polymer in use.

- Methodology:

- Baseline Simulation: Run a full filling, packing, and warpage analysis using initial process parameters.

- Result Decomposition: Use the software's tool to break down the total displacement vector into components driven by orientation, cooling, and area shrinkage.

- Iterative Optimization: Based on the dominant factor, modify the design (e.g., gate location, wall thickness, cooling channels) or process parameters (e.g., packing pressure, mold temperature) and re-run the simulation.

- Expected Outcome: The simulation pinpoints the primary cause of warpage, allowing for effective corrective actions—such as redesigning the cooling layout for uniform temperature or altering the gate position to change flow orientation—without costly physical trials [11].

Quantitative Data for Biomedical Polymer Processing

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from research to aid in material selection and process setup.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Common Biomedical Polymers vs. Human Tissues

| Material Class | Material Type | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Tissue | Cortical Bone | 100.0–150.0 | 10.0–30.0 |

| Soft Tissue | Tendon | 46.0–100.0 | 0.4–1.5 |

| Polymer | Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) | 40.0–80.0 | 2.0–5.0 |

| Polymer | Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | 90.0–140.0 | 3.0–8.0 |

| Polymer | Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) | 50.0–100.0 | 2.0–3.0 |

| Polymer | Polycaprolactone (PCL) | 10.0–40.0 | 0.1–1.0 |

| Polymer | Silicone Rubber (SR) | 5.0–20.0 | 0.008–0.5 |

Data compiled from PMC research on polymers for biomedical applications [12].

Table 2: Defect-Specific Critical Parameters and Thresholds

| Defect | Critical Parameter | Typical Threshold | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharkskin | Wall Shear Stress | 0.1 - 0.3 MPa | High extrusion speed, high-viscosity polymers (e.g., PP, LLDPE) [7] |

| Voids | Curing Pressure | > 2 bar (for FFRC) | Moisture, resin viscosity, fiber architecture [9] |

| Voids | Porosity (on ILSS) | ~8% reduction per 1% porosity | Void shape and distribution [9] |

| Warpage | Cooling Temperature Gradient | Minimize difference between mold halves | Mold design, cooling line placement [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PFAS-Free PPA | Reduces sharkskin by migrating to die wall, lowering friction and facilitating slip. | SILIMER series additives in polyolefin extrusion for medical films and tubes [7]. |

| Medical-Grade PLA | A biodegradable polymer with good biocompatibility and strength for AM. | Optimal polymer for biomedical additive manufacturing (e.g., 3D printed surgical guides) [13]. |

| Epoxy Resin 618 | A bisphenol-A based thermoset resin for creating composite structures. | Matrix material for fabricating flax fiber reinforced composite laminates [9]. |

| RESOMER (PGA, PLA, PLGA) | Commercially available bioresorbable polymers. | Used for 3D printing tissue engineering scaffolds and drug delivery systems [12]. |

| Simulation Software | Predicts material flow, cooling, shrinkage, and warpage in molding processes. | Virtual troubleshooting of warpage in injection-molded component design [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Processing Defects and Solutions

| Defect Symptom | Possible Material-Related Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Shots (Incomplete mold filling) [14] | Melt viscosity too high (MFI too low) [15] [16] | 1. Measure MFI of the material [15].2. Check processing temperature against material supplier's recommendations [17]. | 1. Increase mold/melt temperature [14].2. Select a polymer grade with a higher MFI for the process [15] [18]. |

| Flash (Excess material at edges) [14] | Melt viscosity too low (MFI too high) [16] | 1. Verify MFI of incoming material batch [16].2. Check for thermal degradation (overheating) [17]. | 1. Lower melt temperature and injection pressure [14].2. Use a polymer grade with a lower MFI (higher viscosity) [19]. |

| Weld Lines (Weak lines where flows meet) [14] | Broad MWD or low MFI causing poor polymer inter-diffusion [20] | 1. Analyze MWD of the polymer [20].2. Inspect part at weld lines for weakness. | 1. Increase melt temperature and injection speed [14].2. Select a material with a narrower MWD for more uniform flow [20]. |

| Sink Marks (Surface depressions) [14] | Broad MWD leading to non-uniform shrinkage [20] | 1. Check holding pressure and time.2. Review MWD data from material supplier. | 1. Increase packing pressure and time [14].2. Optimize cooling time.3. Consider a polymer with a narrower MWD [20]. |

| Brittleness (Loss of mechanical properties) [17] | Polymer degradation causing molecular weight reduction (MWD shift to lower weights) [17] | 1. Perform MFI test on molded part; higher than spec indicates degradation [17].2. Check for excessive moisture (hydrolysis) or overheating (thermal degradation) [17]. | 1. Ensure resin is dried to manufacturer's specifications [17].2. Optimize barrel temperature profile and reduce residence time [17]. |

| Flow Lines (Surface patterns) [14] | Inconsistent melt flow due to broad MWD [20] | 1. Visual inspection of defect pattern.2. Analyze MWD for high proportion of low molecular weight chains. | 1. Increase melt and mold temperature [14].2. Increase injection speed.3. Use a material with a narrower MWD [20]. |

Material Selection Guide: Matching MFI to Processing Techniques

| Processing Method | Typical MFI Range (g/10 min) | Rationale | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection Molding [19] | 10 - 30 (High MFI) [19] | Easy flow fills complex, thin-walled molds quickly [15] [19]. | Dumb bells, intricate components [15]. |

| Extrusion [19] | ~1 (Low MFI) [19] | Higher melt strength maintains shape of the extrudate [15] [19]. | Pipes, sheets, monofilament fibers [15]. |

| Blow Molding [19] | 0.2 - 0.8 (Low MFI) [19] | Prevents parison sagging and allows for controlled inflation [15]. | Bottles, containers [15]. |

| Fiber Spinning [15] | 3.6 - 10 (Medium MFI) | Balances flow through fine spinnerets with melt strength for fiber formation [15]. | Monofilament (3.6), multifilament (10.0) [15]. |

| Thermoforming | Medium to High | Sheet must be pliable for forming but not sag excessively during heating. | Packaging, trays [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between a polymer's molecular weight, its MFI, and its mechanical properties?

Molecular weight (MW) and MFI have an inverse relationship [15] [19] [16]. A high MW means long, entangled chains that resist flow, resulting in a low MFI (high viscosity) [16]. These long chains contribute to superior mechanical properties like high tensile strength, impact resistance, and environmental stress-crack resistance [15] [19]. Conversely, a low MW polymer has a high MFI, flows easily, but generally has lower mechanical strength [15] [18].

Q2: How does Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) influence polymer processing and final part performance?

MWD defines the range of polymer chain lengths present [20].

- Narrow MWD: Chains are of similar length, leading to consistent and predictable flow behavior (e.g., sharp melting point, uniform viscosity). This is often desirable for processes like extrusion to ensure a smooth surface finish [20].

- Broad MWD: Contains a mix of short and long chains. The short chains can act as an internal lubricant, improving processability, while the long chains provide mechanical strength and toughness by forming entanglements [20]. However, a broad MWD can lead to inconsistent flow and non-uniform shrinkage, potentially causing defects like warping [20].

Q3: Why can two polymer grades with the same MFI value behave differently in my processing equipment?

MFI is a single-point measurement taken at low shear rates and specific temperature and pressure defined by a standard (e.g., ASTM D1238) [15] [19]. It does not fully characterize the polymer's behavior under the high shear rates and complex flow fields encountered in actual processing (e.g., injection molding) [15]. Two materials with the same MFI can have different molecular weight distributions or levels of long-chain branching, which will cause their viscosity to respond differently to changes in shear rate [15].

Q4: I am seeing random, localized cosmetic defects in my molded parts. Could this be related to material degradation?

Yes. Severe, overall degradation turns parts brittle and discolored [17]. However, a milder process condition (e.g., slightly excessive melt temperature or marginal drying) may cause only a small fraction of polymer chains to degrade [17]. This shifts the MWD slightly, pushing a minority of chains below a critical molecular weight threshold. These few degraded chains can cause sporadic, localized defects (e.g., splay, weak spots) that appear randomly and are difficult to trace, as most of the material appears fine [17].

Q5: How does the molecular weight of a polymer affect the long-term stability of articles like membranes?

Research on polybenzimidazole (PBI) membranes for solvent filtration shows that molecular weight is critical for long-term stability [22]. Under continuous pressure in aggressive solvents like DMF, membranes made from a standard MW polymer (~27,000 g/mol) suffered a gradual decline in performance (compaction) despite crosslinking [22]. In contrast, membranes made from a high MW PBI (~60,000 g/mol) with similar crosslinking showed constant performance. The higher MW provides greater chain entanglement and interchain interactions, resisting rearrangement and compaction over time [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Melt Flow Index (MFI)

Objective: To determine the melt mass-flow rate (MFR) of a thermoplastic polymer according to standardized methods [15].

Principle: The MFR is the mass of polymer extruded through a specific die in 10 minutes under a prescribed temperature and load [15] [19].

Standards: ASTM D1238 / ISO 1133 [15] [19]

Key Reagents and Equipment:

- Melt Flow Indexer: Consists of a heated barrel, a calibrated die, a piston, and weight stacks [15].

- Analytical Balance: Accurate to at least 0.001 g.

- Thermometer: To calibrate and verify barrel temperature.

- Polymer Sample: Typically 4-5 grams of pellets or powder [18].

- Cleaning Tools: Brass brush and cleaning cloth for purging the barrel.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Based on the polymer type, select the standard temperature and load (e.g., 190°C/2.16 kg for polyethylene; 230°C/2.16 kg for polypropylene) [15]. Pre-heat the barrel to the set temperature.

- Loading: Charge the polymer sample into the barrel via a funnel. After 4-5 minutes (pre-heat time), compact the melt with the piston to purge any air.

- Extrusion: Place the specified weight on the piston. After a pre-set time, cut the extruded strand flush with the die.

- Collection & Weighing: Collect and time the extrusion for a standardized period. Weigh the collected extrudate.

- Calculation: The MFR is calculated as: MFR = (Weight of extrudate in grams / time in seconds) × 600 and is reported in g/10 min [15].

Protocol 2: Investigating the Effect of MWD on Crystallization via Simulation

Objective: To use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to elucidate how molecular weight distribution affects the nucleation and crystallization kinetics of a model polymer like polyethylene [23].

Principle: Coarse-grained MD simulations can model polymer chains with specific microstructures (MW, short-chain branching) to observe crystallization behavior at the molecular level, which is challenging to study precisely with experiments alone [23].

Key Reagents and Solutions (In-silico):

- Simulation Software: A molecular dynamics package (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS).

- Force Field: A coarse-grained potential (e.g., Martini) for computational efficiency.

- Polymer Models: Precisely defined trimodal or bimodal PE systems with varying MW components and short-chain branching (SCB) characteristics [23].

Methodology:

- System Construction: Build initial simulation boxes containing a mix of polymer chains representing different molecular weight components (e.g., Low MW, Medium MW, High MW). Define SCB content and distribution (e.g., on medium or long backbones) [23].

- Equilibration: Run the simulation in the melt state at high temperature to achieve an equilibrated, amorphous starting structure.

- Crystallization Run: Quench the system to a temperature below its melting point and run the simulation to observe spontaneous nucleation and crystal growth.

- Analysis:

- Crystallinity: Track the evolution of crystallinity over time using an order parameter.

- Nucleation Rate: Calculate the rate of formation of stable crystal nuclei.

- Morphology: Analyze the final crystal structure (lamellar thickness, tie chains).

Property-Process-Performance Relationships

The core challenge in polymer processing lies in balancing molecular weight (MW), molecular weight distribution (MWD), and Melt Flow Index (MFI) to achieve optimal performance. This diagram visualizes the logical flow from material properties to processing outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Polymer Grades with Controlled MWD | Essential for systematic studies. Includes unimodal, bimodal, and trimodal distributions (e.g., trimodal PE) to isolate the effect of MWD on crystallization and properties [23]. |

| Flow Modifiers / Additives | Peroxide-based additives can increase MFI, while chain extenders can decrease it (increase MW). Used to tailor MFI/MW for specific processes or to simulate degradation/repair (e.g., in recycling studies) [15] [18]. |

| Melt Flow Indexer | The core apparatus for measuring MFI/MFR according to ASTM D1238 or ISO 1133. Used for quality control and to infer relative average molecular weight [15] [19]. |

| Hygroscopic Polymers (e.g., PET, PBT, PLA) | Model materials for studying hydrolysis degradation. Require precise drying before processing to prevent molecular weight breakdown and erratic MFI values [15] [17]. |

| Crosslinking Agents (e.g., Dibromo-p-xylene) | Used to create polymer networks (e.g., for membranes). Studying crosslinking extent and its interaction with initial polymer MW is key for long-term stability in harsh environments [22]. |

| Fillers (Reinforcing & Non-Reinforcing) | Glass fibers, talc, etc. Used to study how fillers interact with polymers of different MFI and how they affect the overall flow and composite properties [15]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | A digital tool to model polymer chains with precise microstructures (MW, MWD, branching). Allows investigation of crystallization, entanglement, and chain dynamics at the molecular level, complementing experimental work [23]. |

Thermal Degradation and Its Consequences for Product Integrity

Thermal degradation is an irreversible process that alters the molecular structure of materials, leading to significant changes in their physical, chemical, and mechanical properties. For researchers and scientists working with polymers and pharmaceuticals, understanding thermal degradation is crucial for developing stable formulations, optimizing processing parameters, and ensuring product safety and efficacy. This technical support center provides practical guidance for identifying, analyzing, and mitigating thermal degradation issues in research and development settings, framed within the broader context of solving polymer processing defects.

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts

1. What is thermal degradation and how does it differ from other degradation types? Thermal degradation refers to the molecular deterioration of materials when exposed to elevated temperatures. Unlike hydrolytic degradation (caused by water) or photodegradation (caused by light), thermal degradation specifically results from heat exposure, which can break polymer chains, alter crystalline structures, and generate degradation products. This process becomes particularly problematic during high-temperature processing such as injection molding, where temperatures can cause polymer chains to break into carbon residues, manifesting as black specks in final products [24].

2. Why does thermal degradation significantly impact product performance? Thermal degradation reduces molecular weight by shortening polymer chains through scission events, directly degrading the material's performance properties. In polymers, this manifests as reduced tensile strength, discoloration, embrittlement, and the generation of low molecular weight species that can migrate or leach out. In pharmaceuticals, degradation can compromise drug safety and efficacy by generating potentially harmful degradation products [25] [26].

3. What are the most common indicators of thermal degradation during processing? Visual indicators include black specks, discoloration, material lumps, crust formation, or gels in final products. Performance indicators include reduced viscosity, odor changes, and diminished mechanical properties. In severe cases, products may exhibit cracking or complete mechanical failure [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Thermal Degradation Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Thermal Degradation Defects and Mitigation Strategies

| Defect Type | Possible Causes | Detection Methods | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Specks/Specks | Overheating, long residence time, dead spots in flow path, contamination | Visual inspection, microscopy, FTIR | Reduce melt temperature, clean equipment, optimize flow path design, use appropriate purge compounds [24] |

| Discoloration | Oxidation, polymer chain scission, additive degradation | Colorimetry, UV-Vis spectroscopy | Implement antioxidant packages, optimize processing temperature, reduce oxygen exposure [24] [26] |

| Reduced Molecular Weight | Chain scission during processing | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Py-GC-MS | Lower processing temperature, reduce mechanical shear, adjust residence time [26] |

| Formation of Degradation Products | Side reactions during processing or storage | LC-MS, Py-GC-MS, EGA-MS | Modify formulation, improve storage conditions, implement stabilizers [25] [26] |

Quantitative Data on Polymer Degradation

Table 2: Degradation Product Formation in Artificially Aged Microplastics

| Polymer Type | Extractable Fraction After Aging | Key Degradation Products Identified | Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | Significant (up to 18%) | Long chain alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids | EGA-MS, Py-GC-MS, SEC [26] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Moderate | Benzoic acid, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, cross-linking observed | EGA-MS, Py-GC-MS, SEC [26] |

| Polyethylene (LDPE/HDPE) | Significant (up to 18%) | Long chain alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, hydroxy acids | EGA-MS, Py-GC-MS, SEC [26] |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Low (highest stability) | Minimal low molecular weight species | EGA-MS, Py-GC-MS, SEC [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Studies

Forced Degradation Studies for Pharmaceutical Products

Forced degradation, also known as stress testing, involves intentionally degrading drug substances and products under conditions more severe than accelerated conditions to identify likely degradation products, establish degradation pathways, and validate stability-indicating analytical methods [25].

Recommended Conditions:

- Hydrolytic Degradation: Expose to 0.1M HCl and 0.1M NaOH at 40°C and 60°C, sampling at 1, 3, and 5 days

- Oxidative Degradation: Treat with 3% H₂O₂ at 25°C and 60°C, sampling at 1, 3, and 5 days

- Thermal Degradation: Store samples at 60°C, 60°C/75% RH, 80°C, and 80°C/75% RH, sampling at 1, 3, and 5 days

- Photolytic Degradation: Expose to 1× and 3× ICH light conditions [25]

Acceptable Degradation Limits: 5-20% degradation is generally acceptable for validation of chromatographic assays, with 10% considered optimal for small pharmaceutical molecules [25].

Artificial Aging Protocol for Polymer Studies

Materials Preparation:

- Obtain polymer micropowders (size range 500-850μm)

- Use reference polymers including PP, PS, PET, LDPE, and HDPE

Aging Procedure:

- Place approximately 200mg aliquots of each polymer in a solar-box system equipped with a Xenon-arc lamp and outdoor filter

- Set conditions to: temperature 40°C, irradiance 750 W/m², relative humidity ~60%

- Age samples for 4 weeks, collecting aliquots at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks

- Store collected samples in sealed glass vials at -20°C until analysis [26]

Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract ~150mg of each aged polymer with 30mL solvent (MeOH for PS, DCM for other polymers) using Soxhlet apparatus for 6 hours

- Concentrate extracts using rotary evaporation

- Analyze both extracts and residues using EGA-MS, Py-GC-MS, and SEC

- Perform derivatization with HMDS for Py-GC-MS analysis of polar degradation products [26]

Visualization of Methodologies

Polymer Degradation Analysis Workflow

Thermal Degradation Pathways and Consequences

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Extraction solvent for degraded fractions of PP, PET, LDPE, HDPE | Selective recovery of low molecular weight degradation products from aged polymers [26] |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Extraction solvent for degraded PS fractions | Selective recovery of low molecular weight degradation products from aged polystyrene [26] |

| Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) | Derivatizing agent for Py-GC-MS analysis | Enhances detection of high polarity, low-volatility degradation products through silylation [26] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (3% H₂O₂) | Oxidative stress agent | Forced degradation studies to simulate oxidative degradation pathways [25] |

| Acid/Base Solutions (0.1M HCl/NaOH) | Hydrolytic stress agents | Forced degradation studies to simulate hydrolytic degradation pathways [25] |

| Reference Polymer Micropowders | Controlled substrate for degradation studies | PP, PS, PET, LDPE, HDPE with defined particle size (500-850μm) for reproducible aging studies [26] |

Advanced Technical Notes

Structural Defects in Polymerization

Recent research using high-resolution molecular imaging techniques has revealed that thermal degradation during polymer synthesis can introduce specific structural defects. In conjugated polymers produced via aldol condensation, approximately 9% of monomer linkages may contain kinks identified as cis-defects in double bond linkages, rather than the expected trans configurations. These structural imperfections significantly impact material performance in electronic applications [27].

Analytical Technique Selection Guide

- Evolved Gas Analysis-Mass Spectrometry (EGA-MS): Ideal for initial screening of thermal degradation behavior and determining optimal pyrolysis temperature ranges [26]

- Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS): Provides detailed molecular information about degradation products through controlled thermal decomposition [28] [26]

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Essential for monitoring changes in molecular weight distribution resulting from chain scission or cross-linking [26]

- X-ray Diffraction Methods: Useful for determining solid-state structures of thermal degradation products, particularly for pharmaceutical compounds [28]

This technical support resource will be periodically updated with additional case studies and emerging research findings. For specific technical inquiries not addressed here, please consult the referenced literature or contact our technical specialists for customized assistance.

The Role of Additives and Fillers in Processability

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Defects and Solutions

The table below summarizes frequent processing issues related to additives and fillers, their root causes, and evidence-based solutions for researchers.

| Defect & Description | Root Causes | Proven Solutions & Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Dispersion [29] [30]White streaks, speckling, or rough film surface indicating uneven filler distribution. | • Inadequate shear mixing [29]• Agglomerated filler particles [29]• Filler-resin incompatibility [30] | • Use high-shear mixers or twin-screw extruders [29] [31].• Select fillers with fine particle size and surface treatments to improve compatibility [30].• Adjust processing temperature; a higher profile can improve dispersion in some systems [30]. |

| Moisture-Related Defects [29] [30] [32]Bubbles, blisters, or "splay" (silver streaks) within or on the polymer. | • Hygroscopic fillers absorbing ambient moisture [29]• Inadequate pre-drying of raw materials [30] | • Pre-dry fillers and polymer at 80–100°C for 2-4 hours before processing [29].• Store raw materials in sealed, dry containers with desiccants [29].• Add moisture-absorbing additives to the compound [30]. |

| Reduced Mechanical Strength [29] [31]Low tensile strength, poor elongation, or increased brittleness. | • Excessive filler loading [29]• Poor interfacial adhesion between filler and matrix [29]• Filler type unsuitable for the polymer matrix [31] | • Optimize filler loading; start with low ratios (e.g., 10-20%) and increase gradually [29].• Ensure carrier resin compatibility; match the masterbatch's carrier resin to the base polymer [29].• Use surface-modified fillers to enhance bonding with the polymer matrix [31]. |

| Warping & Dimensional Instability [29] [32]Part distortion after ejection from the mold. | • Non-uniform cooling [32]• Inhomogeneous shrinkage due to filler shape (e.g., fibers vs. beads) [32]• Overloading filler beyond recommended ratios [29] | • Optimize mold cooling design for uniform heat removal [32].• Select isotropic fillers like glass beads over anisotropic ones like glass fibers to promote uniform shrinkage [32].• Adhere to recommended filler loadings (typically 5-40%) and validate with prototyping [29]. |

| Thermal Degradation (Burns) [32]Brown or black marks on the part, often with a burnt odor. | • Overly high processing temperatures [32]• Trapped, compressed air (diesel effect) [32]• Polymer degradation from excessive shear [33] | • Clean mold vents and ejector pins to allow trapped air to escape [32].• Lower melt temperature and reduce injection speed to minimize shear heating [33] [32].• Incorporate thermal stabilizers to protect the polymer during processing [34]. |

Experimental Protocols for Processability Research

Protocol 1: Evaluating Filler Dispersion and Morphology

This methodology is critical for establishing a cause-effect relationship between processing parameters, filler dispersion, and final composite properties [31].

1. Sample Preparation (Melt Compounding):

- Equipment: Twin-screw extruder (e.g., Haake MiniLab).

- Procedure: Pre-mix the polymer (e.g., Polycarbonate) and filler (e.g., silica, graphene) at predetermined weight percentages (e.g., 0.5%, 1%, 3%). Process the mixture using the extruder with tightly controlled parameters: temperature (e.g., 200°C, 250°C) and screw speed (e.g., 50 rpm, 100 rpm). Collect the extrudate for analysis [31].

2. Dispersion Analysis (Scanning Electron Microscopy - SEM):

- Objective: To visually confirm the degree of filler dispersion and identify agglomerates.

- Procedure: Prepare cryo-fractured samples to expose the internal morphology. Sputter-coat with a conductive layer (e.g., gold). Image using SEM at various magnifications. Well-dispersed composites will show isolated particles, while poor dispersion will show large agglomerates [31].

3. Structural Confirmation (Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering - WAXS):

- Objective: To complement SEM data and confirm filler distribution at the molecular level.

- Procedure: Subject the composite samples to WAXS analysis. A single, broad halo indicates a well-dispersed system without separate phases, whereas distinct crystalline peaks suggest filler agglomeration [31].

Protocol 2: Rheological and Mechanical Property Characterization

This protocol quantifies how fillers influence processability (flow) and the resulting mechanical performance of the composite.

1. Rheological Testing:

- Objective: To determine the effect of fillers on melt viscosity and flow behavior (MFR/MVR).

- Equipment: Capillary rheometer or Melt Flow Indexer (MFI).

- Procedure: Follow ASTM D1238 (MFR) or equivalent. Test samples under standard temperature/piston load conditions (e.g., 190°C / 2.16 kg for PE). Record the mass (MFR) or volume (MVR) of polymer extruded over 10 minutes. Increased filler content typically increases viscosity and reduces MFR [29] [31].

2. Mechanical Testing:

- Objective: To quantify the impact of fillers on stiffness, strength, and elasticity.

- Equipment: Universal Testing Machine (UTM).

- Procedure:

- Tensile Test (ASTM D638): Measure Young's Modulus, Tensile Strength, and Elongation at Break. Fillers like silica can significantly increase the modulus of amorphous polymers [31].

- Impact Test (ASTM D256): Determine the Izod or Charpy Notched Impact Strength. High filler loading often reduces impact strength, indicating increased brittleness [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential materials used in polymer composite research and their primary functions.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Processability Research |

|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate (CaCO₃) | A common mineral filler used to reduce material costs and improve stiffness. Its particle size and coating are critical for studying dispersion and its effect on mechanical properties like impact strength [29] [30]. |

| Fumed Silica / Silica Nanoparticles | Used to modify rheological properties and increase melt viscosity. Ideal for investigating the reinforcement of amorphous polymers and the impact of nano-fillers on Young's Modulus and thermal stability [31]. |

| Graphene & Expandable Graphite | Multifunctional additives for studying the enhancement of thermal conductivity, electrical properties, and flame retardancy. Research focuses on their dispersion and its effect on creating conductive polymer composites (CPCs) [35] [31]. |

| Plasticizers (e.g., Phthalate Esters) | Used to investigate improvements in polymer flexibility and rheology. Studies focus on how they reduce intermolecular forces, lower glass transition temperature (Tg), and improve flow during processing [34]. |

| Thermal Stabilizers & Anti-Oxidants | Essential reagents for research into preventing thermal and oxidative degradation during high-temperature processing (e.g., in twin-screw extrusion). They protect the polymer matrix, extending its processable life [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the ideal filler loading percentage for my application? There is no universal value. The optimal loading depends on the polymer, filler type, and desired properties. Research typically begins with low loadings (10-20%) and incrementally increases, while monitoring mechanical and rheological properties. Exceeding 40% often leads to brittleness and processing issues unless the formulation is specially engineered [29].

Q2: How do fillers impact the recyclability of polymers? Fillers can complicate recycling. They change the melting point and reduce the strength and purity of the recycled resin, often limiting its use to lower-value applications (downcycling) or leading to rejection. This poses a significant challenge for the circular economy and is an active area of research [36].

Q3: Can I use the same filler masterbatch for different base polymers (e.g., PP and PE)? It is not recommended. Using a filler with a carrier resin that does not match your base polymer (e.g., a PE-based filler in PP) leads to poor interfacial adhesion, uneven flow, and surface defects. Always match the carrier resin to the base polymer for optimal performance [29].

Q4: What are the key parameters to monitor during the compounding of filled polymers? Critical parameters include:

- Energy Consumption: Increases with filler content and can vary by polymer type [31].

- Melt Flow Rate (MFR): Indicates changes in melt viscosity [29] [30].

- Melt Temperature: Must be controlled to prevent degradation of the polymer or filler [32].

- Screw Speed & Torque: Directly related to dispersion quality and mechanical energy input [31].

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Defect Detection and Material Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Melt Flow Index (MFI) and Capillary Rheometry?

The Melt Flow Index (MFI), or Melt Flow Rate (MFR), is a single-point measurement that determines the flow of a polymer melt under specific, low-shear conditions (typically between 7 and 36 s⁻¹), expressed as the mass in grams extruded in 10 minutes [37] [38]. In contrast, a capillary rheometer measures the shear viscosity across a wide range of shear rates (from low to over 1000 s⁻¹) and temperatures, providing a comprehensive flow curve [37] [39]. While MFI is a simple, quick test ideal for quality control, capillary rheometry offers a detailed understanding of a polymer's behavior under the high-shear conditions typical of industrial processing like injection molding [37].

Q2: Why might two polymer batches with the same MFI value process differently in our injection molding machine?

An identical MFI value only guarantees similar flow behavior at a single, low shear rate [37] [39]. The processing issues you encounter likely arise from differences in the materials' shear-thinning behavior at the high shear rates experienced during injection molding. Two batches can have the same MFI but different molecular weight distributions or additive packages, leading to significantly different viscosities at high shear rates [39]. A capillary rheometer can detect this by revealing the full viscosity curve, which MFI cannot [37] [39].

Q3: How critical is cleaning for maintaining accurate Melt Flow Index results?

Cleaning is paramount for repeatable and accurate MFI results [40] [41]. Residue from previous tests can degrade, harden, and cause friction—leading to an underestimation of the MFI—or liquefy and act as a lubricant, causing an overestimation [40]. It is recommended to clean the barrel, piston, and die thoroughly after every test [40] [41]. The barrel's internal surface should be visually inspected to ensure it is as smooth as a mirror, free of any contamination [40] [41].

Q4: What does the Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) tell us about a polymer?

The Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) is the quotient of MFR or MVR values measured with different weights (e.g., MFR@5kg / MFR@2.16kg) [41]. It is a measure of a polymer's shear-thinning behavior and, consequently, its molecular weight distribution [41]. A higher FRR indicates a greater sensitivity to shear (more shear-thinning) and typically a broader molecular weight distribution. The FRR provides more insight into the material's processing behavior than a single-point MFI measurement [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Melt Flow Index Testing

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Repeatability | Inconsistent sample mass or filling technique [41]. | Always use the same, correctly weighed sample mass. Fill the barrel in multiple portions, compacting between each [41]. |

| Incomplete or improper cleaning between tests [40] [41]. | Perform a thorough visual cleaning after every test. Use manufacturer-recommended, non-abrasive tools to avoid damaging the barrel [40] [41]. | |

| Moisture in the polymer sample [38]. | Pre-dry hygroscopic materials (e.g., PET, PC, PA) according to the material supplier's recommendations before testing. | |

| Unexpectedly Low MFI | Material residue causing friction in the barrel or die [40]. | Disassemble and clean all components meticulously. For stubborn residues, pyrolysis at high temperature (e.g., 550°C) may be necessary [41]. |

| Barrel or piston damage from corrosive materials [41]. | Inspect for damage. Use corrosion-resistant steel for testing materials like fluoropolymers [41]. | |

| Unexpectedly High MFI | Degraded material due to excessive temperature or residence time [41]. | Verify and calibrate the set temperature. Do not leave material in the barrel longer than necessary. |

| Lubricating additives from a previous test [41]. | Perform a "dummy" test to flush out residual lubricants before the official measurement series. | |

| First Measurement is an Outlier | Residual additives or contaminants on instrument surfaces from previous tests [41]. | The first measurement may flush out contaminants. Ensure consistent cleaning. Consider discarding the first result and using the second and third measurements [41]. |

Capillary Rheometry

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy or Erratic Viscosity Data | Air bubbles trapped in the polymer melt [41]. | Ensure proper and bubble-free filling of the rheometer barrel. Pre-compact the material adequately [41]. |

| Instability in the temperature profile of the barrel. | Allow sufficient time for temperature equilibration. Check and calibrate the temperature sensors. | |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Tests | Polymer degradation during the test at high temperatures and shear rates. | Use an inert gas purge (e.g., Nitrogen) to prevent oxidative degradation. Minimize the total residence time in the barrel. |

| Inconsistency in sample preparation (drying, pellet size). | Standardize the sample preparation protocol, especially drying time and temperature. | |

| Bagley or Rabinowitsch Correction Errors | Incorrect selection or use of the orifice (zero-length) die. | Ensure the orifice die is used correctly for the Bagley correction and that the data analysis procedure is properly applied [37]. |

Connecting Rheology to Polymer Processing Defects

Understanding rheological data is key to diagnosing and solving injection molding defects. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from material analysis to defect resolution.

The table below links key rheological properties to common processing defects and proposed solutions, providing a direct actionable guide for researchers.

| Rheological Property / Behavior | Related Processing Defects | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Viscosity at Processing Shear Rates | Flash (thin plastic seepage along mold lines) [42]. | Increase clamp force; reduce injection speed/pressure; select material with higher viscosity (lower MFR) [42] [43]. |

| High Viscosity at Processing Shear Rates | Short shots (incomplete filling) [42] [43]; Weld/Knit Lines (weak seams where flow fronts meet) [42] [43]. | Increase melt temperature, injection speed, and pressure; optimize gate and runner design; select material with lower viscosity (higher MFR) [42] [43]. |

| Excessive Shear Thinning (High FRR) | Jetting (snake-like surface lines) [42] [43]; Potential for molecular orientation and weak spots. | Modify gate design (use fan gates); reduce injection speed; increase mold temperature [42] [43]. |

| Material Sensitive to Prolonged Heat | Burn marks (dark discoloration) [42] [43]; Degradation, causing bubbles or splay marks [43]. | Reduce melt temperature and barrel residence time; ensure proper drying of resin; improve mold venting to allow gases to escape [42] [43]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

The following table details key materials and equipment essential for experiments in this field.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Melt Flow Indexer (Plastometer) | The standard instrument for determining Melt Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume Rate (MVR) according to ASTM D1238 and ISO 1133. Used for quick quality control checks [40] [38]. |

| Capillary Rheometer | Advanced instrument that measures shear viscosity over a wide range of shear rates and temperatures. Provides comprehensive data for process simulation and fundamental material understanding [37] [39]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Polymers with known and certified MFI/MVR values. Critical for instrument calibration, method validation, and monitoring the consistency of results over time [40] [44]. |

| Corrosion-Resistant Barrel & Piston Sets | Specialized tooling made from high-grade steel (e.g., Hastelloy) for testing corrosive polymers, such as fluoropolymers, which can release acids that damage standard steel components [41]. |

| Go/No-Go Gauges | Precision tools for preventative maintenance. Used to check the inner diameter of the die and the outer diameter of the piston to ensure they remain within the tolerances specified by testing standards [40]. |

| Integrated or Automated Cleaning Systems | Devices and tools designed specifically for the MFI tester to facilitate thorough and non-damaging cleaning of the barrel, piston, and die, eliminating a major source of experimental error [40] [41]. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Melt Flow Index (MFI) Test according to ASTM D1238 / ISO 1133

Objective: To determine the mass (MFR) or volume (MVR) of polymer extruded through a specified die under prescribed conditions of temperature, load, and piston position.

- Apparatus Preparation: Pre-heat the melt flow indexer to the standard temperature specified for the polymer (e.g., 190°C for PE, 230°C for PP). Ensure the barrel, piston, and die are meticulously clean and mirror-smooth [40] [41].

- Sample Loading: Weigh the appropriate mass of polymer pellets (e.g., 4-5g for PE). After the pre-heat period, load the material into the barrel in several portions. After each portion, use a packing rod to compact the material firmly to eliminate air bubbles [41].

- Melting & Pre-compaction: Allow the material to melt for the specified time (e.g., 5 minutes per ISO 1133, 7 minutes per ASTM D1238). In the final minute, push the piston down to ensure the die is filled with melt. At the end of the melting time, the piston should be in a slightly raised position [41].

- Application of Load: Place the specified weight (e.g., 2.16 kg) onto the piston.

- Measurement & Cutting:

- For MFR: As the piston descends, use a clean knife to cut the extruded strand at fixed time intervals once the piston reaches the marked test range. Weigh the collected strand segments accurately [41] [38].

- For MVR: An instrumented machine automatically records the piston displacement over time in the standard test range (typically 50 mm to 20 mm before the die) and calculates the volume flow rate [41] [38].

- Calculation & Reporting: Calculate MFR (g/10 min) by normalizing the mass collected to a 10-minute period. Report the test conditions (temperature, load, die size) alongside the result [38].

Protocol 2: Multi-Weight Measurement for Flow Rate Ratio (FRR)

Objective: To determine the shear-thinning behavior of a polymer by measuring its MFR or MVR with multiple weights from a single barrel filling.

- Initial Steps: Follow steps 1-4 of the standard MFI test, starting with the smallest weight.

- Automatic Weight Sequencing: Modern automated melt indexers (e.g., Göttfert mi40) allow pre-programming of a sequence of weights. The machine automatically adds the next weight once a stable flow is established for the previous weight [41].

- Data Collection: The instrument measures the MVR for each weight within the standard measuring range (e.g., 50-20 mm before the capillary) [41].

- Calculation: The FRR is calculated by forming a quotient from the results of two different weights (e.g., MFR@5kg / MFR@2.16kg). This ratio is a measure of the material's sensitivity to shear and its molecular weight distribution [41].

Protocol 3: Viscosity Curve Measurement via Capillary Rheometry

Objective: To characterize the shear viscosity of a polymer melt over a wide range of shear rates relevant to processing.

- Apparatus Setup: Install a capillary die with a specific length (L) and diameter (D) and a matching "zero-length" orifice die for Bagley correction. Set the desired temperature profile in the barrel [37].

- Sample Loading & Packing: Fill the pre-heated barrel with a weighed sample of polymer. Use a plunger to pack the material thoroughly to eliminate air pockets.

- Pre-conditioning: Allow the sample to thermally equilibrate for a predetermined time to ensure a uniform melt temperature.

- Testing Sequence: Program the rheometer to perform a series of piston speed steps (or a continuous speed ramp). Each speed corresponds to a different apparent shear rate.

- Data Collection: At each piston speed, the machine measures the pressure drop (ΔP) across the capillary die. The pressure drop across the orifice die is also measured simultaneously to correct for entrance pressure losses (Bagley correction) [37].

- Data Analysis: The software calculates the apparent shear rate, corrects the wall shear stress using the Bagley correction, and further applies the Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch correction to account for the non-parabolic flow profile of non-Newtonian fluids. The final output is a graph of shear viscosity versus shear stress or shear rate [37].

In polymer processing research, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy are indispensable techniques for molecular-level analysis. Both methods provide unique "molecular fingerprints" that are crucial for characterizing materials, identifying contaminants, and understanding polymer degradation mechanisms [45]. For researchers and scientists investigating polymer processing defects, these spectroscopic tools offer non-destructive, label-free analysis capabilities that can reveal critical information about chemical composition, crystallinity, and structural changes during thermal processing or environmental exposure.

The complementary nature of FTIR and Raman spectroscopy makes them particularly powerful when used together. FTIR is preferred for organic analysis of materials such as plastics and polymers, with extensive libraries containing over 300,000 reference spectra for identification [45]. Raman spectroscopy excels at analyzing possible inorganic materials such as metal oxides and ceramics and provides unique capabilities for carbon analysis, including characterizing C-C bonding (sp2 vs sp3) in various carbon allotropes such as graphite, diamond, graphene, and diamond-like carbon films [45]. This combined approach enables comprehensive characterization of polymer systems, from bulk composition to surface effects that often contribute to processing defects and product failure.

Technical Comparison: FTIR vs. Raman for Polymer Analysis

The selection between FTIR and Raman spectroscopy depends on specific analytical needs, sample properties, and the nature of the information required. The table below summarizes key technical considerations for polymer defect analysis:

| Parameter | FTIR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Analysis Spot Size | ~50-100 microns [45] | ~1-2 microns [45] |

| Library References | >300,000 spectra [45] | ~55,000 spectra [45] |

| Strength for Material Type | Excellent for organics, plastics, polymers [45] | Better for inorganics, metal oxides, ceramics [45] |

| Carbon Analysis | Limited capability | Excellent for C-C bonding (sp2 vs sp3), graphite, graphene, DLC [45] |

| Water Compatibility | Challenging due to strong water absorption [46] | Excellent, suitable for aqueous environments [47] |

| Mapping Capability | Standard | Advanced 2D mapping and depth profiling [45] |

| Primary Selection Guide | Bulk organic composition, functional groups | Inorganic fillers, carbon structures, surface heterogeneity |

For polymer processing defect investigation, Raman's smaller analysis size enables identification of microscopic contaminants or inhomogeneities, while FTIR's extensive libraries facilitate rapid identification of unknown organic materials. Raman's unique capability for carbon characterization is particularly valuable for analyzing carbon-filled polymers or investigating diamond-like carbon coatings in medical devices [45].

FTIR Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Frequently Encountered FTIR Issues

FTIR users often encounter specific, solvable problems that affect spectral quality and data interpretation. The following table outlines common FTIR issues and their practical solutions:

| Problem | Observed Symptom | Root Cause | Solution | Relevance to Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument Vibration | Noisy spectra, strange peaks, distorted baselines [48] | Physical disturbances from pumps or lab activity [48] | Isolate instrument from vibrations; ensure stable mounting [48] | Prevents false interpretation of polymer degradation signatures |

| Dirty ATR Crystal | Negative absorbance peaks [48] [49] | Contaminated crystal during background collection [49] | Clean crystal thoroughly and collect fresh background [48] | Ensures accurate surface analysis of polymer films |

| Surface vs. Bulk Effects | Different spectra from surface vs. interior [48] | Surface oxidation, plasticizer migration, additives [48] [49] | Analyze both surface and freshly cut interior [48] | Identifies surface oxidation or additive migration defects |

| Incorrect Data Processing | Distorted peaks, saturated appearance [48] | Using absorbance instead of Kubelka-Munk for diffuse reflection [48] [49] | Process diffuse reflection data in Kubelka-Munk units [48] | Correctly interprets filled polymer or composite spectra |

FTIR Experimental Protocol for Polymer Surface/Bulk Analysis

Purpose: To identify whether observed chemical differences represent true bulk composition or are limited to surface effects—common in polymer oxidation or additive migration defects.

Materials:

- FTIR spectrometer with ATR accessory

- Sharp blade or microtome for cross-sectioning

- Solvent (e.g., methanol) for cleaning

- Mounting equipment for small samples

Procedure:

- Place the polymer sample as-received on the ATR crystal

- Collect FTIR spectrum of the surface (typically 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 32 scans)

- Remove the sample and carefully cut through the surface to expose the interior

- Place the freshly exposed interior surface on the ATR crystal

- Collect FTIR spectrum of the bulk material using identical parameters

- Compare key peak ratios (e.g., carbonyl index at ~1710 cm⁻¹, methylene deformations at ~1460 cm⁻¹) between surface and bulk spectra [48] [49]

Interpretation: Significant differences in oxidation peaks (carbonyl) or additive signatures between surface and bulk spectra indicate surface-specific phenomena that may explain processing defects such as environmental stress cracking or reduced adhesion.

Raman Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Frequently Encountered Raman Issues

Raman spectroscopy, while powerful, presents distinct challenges that can compromise data quality. The following table addresses common Raman artifacts and their mitigation strategies:

| Problem | Observed Symptom | Root Cause | Solution | Relevance to Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Interference | High background, obscured Raman signals [47] [46] | Natural sample emissions overwhelming weak Raman signals [46] | Use longer wavelength lasers (785nm, 1064nm); time-gated detection [47] [46] | Critical for analyzing fluorescent polymers or additives |

| Laser-Induced Sample Damage | Spectral changes during measurement, burning [47] | Excessive laser power density exceeding sample threshold [47] | Reduce laser power; use defocused beam; implement cooling [47] | Prevents thermal degradation of heat-sensitive polymers |

| Cosmic Rays | Sharp, intense spikes in spectrum [47] | High-energy radiation interacting with detector [47] | Use cosmic ray filters; collect multiple spectra with averaging [47] | Eliminates false peaks misinterpreted as crystal defects |

| Calibration Drift | Incorrect peak positions, shifting spectra [47] | Instrumental variations, temperature fluctuations [47] | Regular calibration with standard references (e.g., silicon) [47] | Ensures accurate polymer identification and quantification |

Raman Experimental Protocol for Polymer Degradation Monitoring

Purpose: To characterize conformational changes and crystallinity development during thermal exposure or degradation—essential for understanding polymer embrittlement and failure mechanisms.

Materials:

- Raman spectrometer (532nm or 785nm laser recommended)

- Temperature-controlled stage for in situ analysis

- Reference standards for calibration

- Thin polymer films or microtomed sections

Procedure:

- Calibrate Raman spectrometer using silicon reference (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹)

- Mount pristine polymer sample and collect initial spectrum

- For thermal exposure studies: place sample in oven at controlled temperature (e.g., 110°C for HDPE [50])

- Remove at predetermined intervals and collect Raman spectra

- Focus on key spectral regions: C-C stretching (1060-1150 cm⁻¹), CH₂ twisting (1300-1350 cm⁻¹), C=C stretching (1650-1660 cm⁻¹) [50]

- Monitor changes in peak intensity ratios related to crystallinity and conformational ordering

Interpretation: Increasing intensity of crystalline bands and decreasing amorphous signals indicate structural reorganization. In HDPE, the growth of trans sequences correlates with embrittlement and loss of mechanical properties [50]. For recyclability assessment, track these changes to determine degradation extent and potential for reuse.

Advanced Techniques and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

The following table outlines essential materials and their functions in spectroscopic analysis of polymers:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (diamond, ZnSe, Ge) | Internal reflection element for surface measurement [49] | Polymer surface oxidation analysis |

| Silicon Wafer Reference | Spectral calibration standard (520.7 cm⁻¹ peak) [47] | Daily Raman instrument calibration |

| Optical Antioxidants (e.g., BHT) | Prevents thermal degradation during measurement [50] | High-temperature polymer analysis |

| Xylene/Methanol | Solvent system for polymer purification [50] | Remove additives/interferences before analysis |

| Kubelka-Munk Transformation | Corrects diffuse reflectance data [48] [49] | Accurate analysis of filled polymers and composites |

Mapping and Depth Profiling for Defect Analysis

Raman mapping provides powerful capabilities for characterizing heterogeneity in polymer systems. The technique enables 2D mapping to study material distribution and depth profiling to investigate composition changes as a function of depth [45]. This is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications to determine homogeneous distribution of active and inactive ingredients in polymer-based drug delivery systems [45].

Experimental Considerations:

- Spatial resolution: ~1μm lateral, depending on laser wavelength and objective

- Mapping time: Varies with area size and resolution (typically hours for detailed maps)

- Data analysis: Multivariate methods (PCA) often required for interpreting complex maps

For polymer processing defects, mapping can reveal filler distribution inhomogeneity, phase separation in blends, or contamination localization that causes mechanical failure.

Workflow Visualization for Defect Investigation

The following diagram illustrates the systematic approach for investigating polymer processing defects using FTIR and Raman spectroscopy:

Systematic Approach for Polymer Defect Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I see negative peaks in my FTIR-ATR spectrum, and how do I fix this? Negative peaks typically indicate that the ATR element was dirty when the background spectrum was collected [48] [49]. The solution is to clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with an appropriate solvent, collect a fresh background spectrum, and then re-analyze your sample.

Q2: My Raman spectrum shows an extremely high fluorescent background that obscures the signal. What are my options? Fluorescence interference is a common challenge in Raman spectroscopy [47] [46]. Several approaches can mitigate this: (1) Use a longer wavelength laser (785nm or 1064nm instead of 532nm) to reduce fluorescence excitation; (2) Employ time-gated Raman spectroscopy to separate Raman signals from longer-lived fluorescence; (3) Use mathematical background subtraction algorithms if the fluorescence is relatively uniform [47].

Q3: When analyzing plastic materials, I get different spectra from the surface versus a freshly cut interior. Which represents the true material? Both represent "true" but different information about your material. Polymer surfaces often have different chemistry due to oxidation, additive migration, or processing effects [48] [49]. The interior typically represents the bulk composition. For complete characterization, analyze both surfaces and consider using ATR with different penetration depths to profile surface versus bulk chemistry.

Q4: How can I distinguish between one-dimensional and zero-dimensional defects in carbon-based polymers using Raman spectroscopy? Raman spectroscopy can distinguish defect dimensionality through two measurement parameters: defect-induced activation of forbidden Raman modes and defect-induced confinement of phonons [51]. Zero-dimensional defects (vacancies, substitutional atoms) and one-dimensional defects (grain boundaries, dislocations) have strikingly different spectroscopic signatures that affect these parameters differently [51].

Q5: What is the minimum level of adulteration or contamination I can detect in polymer systems using these techniques? Detection limits depend on the specific contaminant and matrix, but Raman spectroscopy has demonstrated detection of adulterants at levels as low as 5% in complex organic systems [46]. With advanced techniques such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), detection limits can extend to under 1% for certain compounds [46].

Q6: My diffuse reflection FTIR spectra look saturated and distorted. What processing method should I use? Diffuse reflection spectra should be processed in Kubelka-Munk units rather than absorbance [48] [49]. Converting to Kubelka-Munk units will correct the distorted, saturated appearance and provide a spectrum that can be properly interpreted.

Troubleshooting Guides

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Troubleshooting

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Causes | Solutions & Verification Methods | Related Polymer Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large endothermic start-up hook | Heat capacity mismatch between sample and reference pans; Heat transfer from cooling system at subambient temperatures [52]. | Use reference pans 0–10% heavier than sample pan using aluminum foil; Start experiment 50°C below the event of interest; Use dry nitrogen purge through cell base [52]. | Glass transition (Tg) detection, initial thermal state. |

| Unexpected transition at 0°C | Water condensation in sample or purge gas, acting as a plasticizer [52]. | Store hygroscopic samples in a desiccator; Use a drying tube for purge gas; Weigh sample before and after run to check for weight loss [52]. | Tg, melting point, sample composition. |

| Apparent 'melting' at Tg | Relaxation of internal stresses from processing or thermal history [52]. | Anneal sample by heating 25°C above Tg followed by quench cooling [52]. | Structural integrity, thermal history, degree of cure. |