Strategies for Improving Polymer Blend Compatibility: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing polymer blend compatibility, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Strategies for Improving Polymer Blend Compatibility: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing polymer blend compatibility, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the fundamental principles governing polymer miscibility, details advanced methodological approaches including compatibilizer use and autonomous discovery platforms, and addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimization. The content also covers rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of blend performance, with a specific focus on applications in biomedical materials, drug delivery systems, and sustainable polymer design.

Understanding Polymer Blend Fundamentals: Miscibility, Morphology, and Interfacial Phenomena

FAQ: Fundamental Terminology

What is the core difference between a polymer blend and a polymer alloy?

A polymer blend is a mixture of two or more polymers or copolymers. A polymer alloy is a specific subclass of polymer blends; it is an immiscible but compatible blend where the interface and morphology have been modified, typically through compatibilization, to create a material with uniform physical properties and enhanced performance [1] [2] [3].

Are the terms "blend" and "alloy" interchangeable?

While often used interchangeably in general discussion, they are technically distinct. A blend can be either miscible or immiscible. An alloy is specifically an immiscible blend that has been compatibilized to create a stable, heterogeneous mixture with controlled morphology [1] [2].

Why is compatibilization critical for creating polymer alloys?

Compatibilization addresses the inherent weaknesses of immiscible polymer blends, which include poor interfacial adhesion and thermodynamic instability. Compatibilizers, often block or graft copolymers, act like surfactants at the interface between the two polymer phases. This action reduces interfacial tension, prevents phase separation, decreases dispersed phase particle size, and significantly improves mechanical properties, transforming an immiscible blend into a usable alloy [1] [4].

Experimental Protocol: Compatibilization of Immiscible Blends

The following protocol outlines a standard method for creating and evaluating a compatibilized polymer alloy via melt blending, a common industrial and lab-scale technique.

Objective: To convert an immiscible polymer blend into a compatibilized polymer alloy and characterize the resulting morphology and properties.

Materials:

- Polymer A (e.g., Polypropylene, PP)

- Polymer B (e.g., Polyamide, PA)

- Compatibilizer (e.g., Maleic Anhydride grafted PP (PP-g-MA))

- Solvent (if using solution blending method, not covered here)

Equipment:

- Twin-screw extruder (for melt blending)

- Injection moulding or compression press

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC)

- Universal Testing Machine

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Procedure:

- Pre-mixing: Pre-dry all polymer pellets to remove moisture. Manually mix pellets of Polymer A, Polymer B, and the compatibilizer in the desired weight ratios (e.g., 70/30/5 for PP/PA/PP-g-MA).

- Melt Blending: Feed the pre-mixed material into a twin-screw extruder. Set the temperature profile to appropriate ranges for the polymer components (e.g., 180-220°C for PP/PA systems) and set the screw speed to ensure sufficient shear and mixing.

- Pelletizing: Upon extrusion, cool the strand in a water bath and pelletize the resulting material for subsequent testing.

- Specimen Preparation: Use an injection moulding machine or compression press to form the pellets into standard test specimens (e.g., tensile bars, impact test pieces).

- Characterization:

- Thermal Analysis (DSC): Run a DSC cycle from -50°C to 250°C. A compatibilized alloy will still show distinct glass transition temperatures (Tg) for each polymer phase, confirming immiscibility, but the Tg values may shift slightly.

- Morphological Analysis (SEM): Fracture the test specimen and etch away the dispersed phase (if possible). Observe the fracture surface under SEM. A well-compatibilized alloy will show fine, uniform dispersion of one phase within the other and no signs of de-lamination, indicating strong interfacial adhesion [1].

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile and impact tests. Successful compatibilization is confirmed by a marked improvement in properties like impact strength and elongation at break compared to the uncompatibilized blend [1].

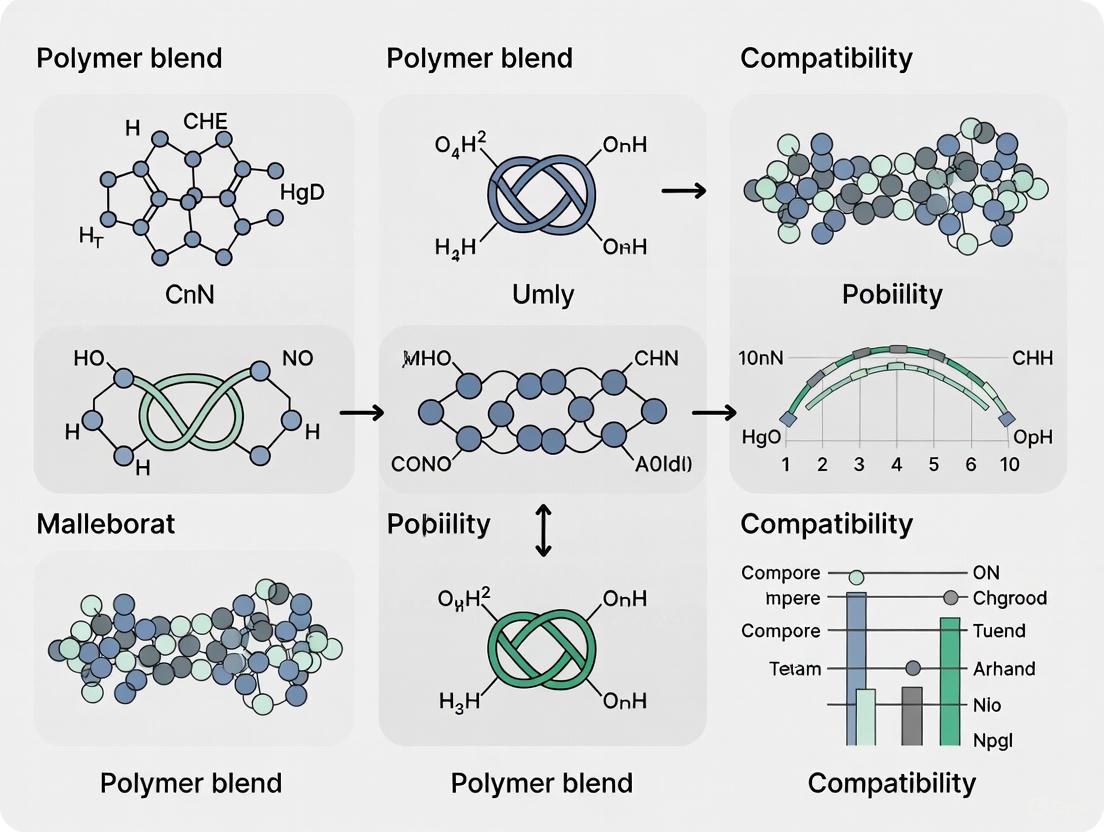

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from an immiscible blend to a characterized polymer alloy.

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Materials for Alloying

The table below lists essential reagents and materials used in polymer blend and alloy research.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Block or Graft Copolymers (e.g., PS-b-PMMA, PP-g-MA) | Acts as a compatibilizer. One block is miscible with one polymer phase, the other block with the second phase, reducing interfacial tension and stabilizing morphology [1]. |

| Maleic Anhydride (MA) | A common monomer used to graft onto polyolefins (e.g., creating PP-g-MA) to create reactive compatibilizers that can chemically bond with polymers like polyamide [1] [5]. |

| Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | A free-radical initiator used to promote grafting reactions during melt blending, such as the grafting of maleic anhydride onto a polymer chain [5]. |

| Joncryl (Chain Extender) | A commercial epoxy-functionalized polymer additive used as a compatibilizer and to control melt viscosity during processing of blends like PLA/PBAT [5]. |

| Hypromellose Acetate Succinate (HPMCAS) / Povidone (PVP) | Polymer pairs used in pharmaceutical research to create polymer alloys for amorphous solid dispersions, enhancing drug loading and dissolution [4]. |

The following table summarizes key characteristics that differentiate simple blends from compatibilized alloys, based on experimental observations.

| Characteristic | Immiscible Polymer Blend | Compatibilized Polymer Alloy |

|---|---|---|

| Miscibility | Immiscible, heterogeneous | Immiscible but compatible, heterogeneous |

| Interfacial Adhesion | Weak | Strong (modified interface) |

| Phase Stability | Thermodynamically unstable, phases coalesce | Stabilized morphology, resistant to coalescence [1] |

| Dispersed Phase Size | Large, uneven domains | Fine, uniformly dispersed domains [1] |

| Mechanical Properties | Poor (e.g., brittle, low impact strength) | Enhanced (e.g., high impact strength, ductility) [1] [6] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | Shows distinct Tg of parent polymers | Shows distinct but potentially shifted Tg values |

This guide is part of a broader thesis on improving polymer blend compatibility research. Precise terminology is the foundation for replicable experiments and clear scientific communication.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase separation or haziness in blend | Immiscibility due to differing chemical structures, polarity, or thermal characteristics [7] | Visual inspection, microscopy, multiple glass transition temperatures (Tg) in DSC [1] [8] | Incorporate a compatibilizer (block or graft copolymer) [7] [9]; Optimize processing parameters (temperature, shear rate) [7] |

| Poor mechanical performance (brittleness, low strength) | Weak interfacial adhesion between phases [1] | Mechanical testing (tensile, impact); Analysis of Tg [1] | Use reactive compatibilizers to form chemical bonds at interface [9]; Employ nanoparticles (silica, clay) as compatibilizing agents [9] |

| Optical defects (cloudiness) | Phase separation causing light scattering [7] | Optical microscopy, light scattering measurements [10] | Select polymers with closer chemical affinity [7]; Utilize miscible polymer pairs (e.g., PPO/PS) [8] |

| Property instability during processing/storage | Thermodynamically unstable, coalescing morphology [1] | Thermal analysis (DSC), aging studies, rheology [1] [11] | Stabilize morphology with compatibilizers [1]; Control cooling rates to influence crystallization [7] |

| Drug recrystallization in Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASD) | Supersaturation, amorphous-amorphous phase separation (AAPS) [12] | DSC, PXRD [12] [11] | Select optimal polymeric carrier using predictive tools (e.g., COSMO-SAC) [12]; Utilize polymers with protective effect (e.g., Soluplus) [13] |

Advanced Diagnostic Table for Polymer Compatibility

| Analytical Technique | Measures / Detects | Interpretation of Results for Miscibility |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | A single, composition-dependent Tg indicates miscibility; two distinct Tgs indicate immiscibility [1] [8]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Crystalline form, crystalline domain size (CDSz) | Presence of drug crystalline peaks in CSDs confirms crystalline state; peak broadening indicates reduced crystalline size [11]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic radius (RH) | Shifts in RH with blend composition indicate polymer-polymer interactions and can identify phase separation points [10]. |

| Rheology | Zero-shear viscosity (η0), equilibrium compliance (Je0) | Deviation from linear mixing rules indicates specific interactions; thermo-rheological complexity suggests miscible but heterogeneous blends [14]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface morphology, crystalline size | Observation of rough surfaces and reduced crystalline size in CSDs correlates with enhanced dissolution rates [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between "miscible," "immiscible," and "compatible" polymer blends?

- Miscible Blends: Form a single, homogeneous phase at the molecular level. They exhibit one glass transition temperature (Tg) that varies with composition [8].

- Immiscible Blends: Form multi-phase structures with separated domains. They exhibit multiple Tgs corresponding to the pure components and often require compatibilization [1] [8].

- Compatible Blends: A sub-category of immiscible blends. While they remain multi-phase, they exhibit macroscopically uniform physical properties and sufficient interfacial adhesion due to specific interactions, making them useful for commercial applications [8].

Q2: Why are most polymer pairs inherently immiscible?

The driving force for mixing is the Gibbs free energy of mixing (ΔGm = ΔHm - TΔSm). Polymers have long chains, leading to a very small gain in mixing entropy (ΔSm). Therefore, for ΔGm to be negative (spontaneous mixing), the enthalpy term (ΔHm) must be negative and significant, which typically requires strong specific interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) between the different polymers. This favorable enthalpic interaction is rare, making immiscibility the rule rather than the exception [14].

Q3: What are the primary functions of a compatibilizer in an immiscible blend?

Compatibilizers, often block or graft copolymers, act like "molecular surfactants" at the interface between two immiscible polymer phases. Their key functions are [7] [1] [9]:

- Reduce Interfacial Tension: This promotes finer dispersion of one phase within the other during mixing.

- Stabilize Morphology: They prevent the dispersed phase from coalescing into larger domains after processing, "freezing in" a metastable morphology.

- Improve Interfacial Adhesion: By having segments compatible with both phases, they act as molecular bridges, enhancing stress transfer and thus improving mechanical properties like toughness.

Q4: How can I quickly screen for drug-polymer compatibility in pharmaceutical amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs)?

Beyond traditional trial-and-error, modern computational tools offer efficient screening. The COSMO-SAC (Conductor-like Screening Model-Segment Activity Coefficient) model is a promising, first-principles method. It relies on quantum-mechanically derived σ-profiles of the drug and polymer molecules to predict thermodynamic compatibility (solubility and miscibility) without requiring experimental data for parameter fitting. This allows for the rational selection of optimal polymeric carriers to inhibit recrystallization and enhance drug bioavailability [12].

Q5: Our polymer blend has good properties directly after processing but deteriorates over time. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of thermodynamic instability. The high shear during processing (e.g., extrusion) can temporarily create a fine, dispersed morphology. However, once the shear is removed, the system begins to move toward its equilibrium state of gross phase separation through a process called coalescence. The blend is immiscible and lacks adequate kinetic stabilization. To solve this, you need to compatibilize the blend to create a metastable morphology that is resistant to coalescence over time [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Polymer-Polymer Compatibility via Hydrodynamic Radius

Principle: This method uses Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to monitor changes in the hydrodynamic radius (RH) of polymers in a common solvent as their blend ratio is varied. Shifts in RH indicate inter-polymer interactions, helping to identify compatibility windows and phase separation points [10].

Materials:

- Polymers A and B (e.g., Polystyrene and Polymethyl methacrylate)

- Common solvent (e.g., Benzene, Toluene)

- Digital refractometer

- Ostwald viscometer or rotational rheometer

- Dynamic Light Scattering apparatus with a correlator

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a master stock solution of each polymer (e.g., 4% w/v) in the common solvent.

- Blend Series: Create a series of polymer blends covering the entire composition range (e.g., 100/0, 80/20, 50/50, 20/80, 0/100 of Polymer A/Polymer B) while keeping the total polymer concentration constant.

- Dust Removal: Filter each solution through a 0.2 μm filter directly into a clean light scattering cell.

- DLS Measurement: Perform dynamic light scattering measurements on each blend composition at a fixed angle (e.g., 90° or 108°).

- Viscosity Measurement: In parallel, measure the viscosity of each blend solution at different shear rates using a capillary or rotational viscometer.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the hydrodynamic radius (RH) for each blend composition from the DLS data.

- Plot RH and intrinsic viscosity ([η]) against the blend composition.

Interpretation: A smooth, monotonic change in RH and [η] with composition suggests some level of compatibility or stable interactions. A pronounced maximum or minimum, or a sharp discontinuity in the plot, often indicates a point of phase separation or significant change in polymer conformation due to antagonistic interactions [10].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Drug-Polymer Compatibility and Humidity Stability for CSDs

Principle: This protocol simulates thermal processing and aging to evaluate the stability of Crystalline Solid Dispersions (CSDs) under humidity stress. It correlates changes in dissolution behavior with microstructure (crystalline size, crystallinity, surface composition) and drug-polymer compatibility [11].

Materials:

- Model drug (e.g., Bifonazole - BFZ)

- Polymeric carriers (e.g., Poloxamer 188, Poloxamer 407, PEG 8000)

- Spray dryer

- HPLC system with validated method

- Stability chambers with humidity control

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Powder X-ray Diffractometer (PXRD)

- Intrinsic Dissolution Rate (IDR) apparatus

Procedure:

- CSD Preparation: Prepare CSDs using spray drying. For example, dissolve BFZ and a polymer carrier (e.g., Poloxamer 188) in a suitable solvent and process through the spray dryer to form a solid dispersion [11].

- Initial Characterization:

- Surface Morphology: Use SEM to examine the crystalline size and surface morphology of the raw drug and the washed CSD particles.

- Crystalline Form: Use PXRD to confirm the drug remains crystalline and calculate the crystalline domain size (CDSz) using the Scherrer equation.

- Baseline Dissolution: Determine the Intrinsic Dissolution Rate (IDR) of the freshly prepared CSD.

- Stability Stress Test:

- Place samples of each CSD formulation in a stability chamber set at 25°C and 75% relative humidity (RH) for a predetermined period (e.g., 1-3 months) [11].

- Post-Stability Characterization:

- Re-measure the IDR and compare it to the baseline.

- Re-analyze the microstructure using SEM and PXRD to detect changes in crystalline size, crystallinity, and surface drug distribution.

Interpretation:

- A smaller change in IDR after humidity exposure indicates better stability.

- Stronger drug-polymer compatibility (e.g., in CSD-P407 systems) results in lower drug mobility, leading to more uniform drug distribution on the CSD surface and superior stability against humidity-induced changes [11].

- Polymers with a protective effect (like Soluplus for metoprolol) can delay drug decomposition, while incompatible pairs (like Paracetamol/PVA) show clear signs of thermal instability and decomposition [13].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Compatibilization Pathways for Immiscible Polymers

This diagram illustrates the primary strategies for compatibilizing immiscible polymer blends, moving from the initial problem to the implemented solution and final outcome.

Polymer Blend Miscibility Decision Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps and analytical techniques used to determine the miscibility of a polymer blend and guide subsequent development actions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Compatibilizers (Premade) | Reduce interfacial tension, stabilize morphology, improve adhesion [7] [1]. | Block/Graft Copolymers: Segments must be miscible with respective blend components (e.g., PS-b-PMMA for PS/PMMA blends). Effectiveness limited by migration kinetics to interface [9]. |

| Reactive Compatibilizers | Form in-situ covalent bonds at interface during processing, creating graft copolymers [9]. | Relies on chemical reactions (e.g., between anhydride and amine groups). Effectiveness depends on choice of reactive groups and catalysts. Can be more effective than premade compatibilizers [9]. |

| Nanoparticle Additives | Can act as compatibilizing agents by locating at the interface, acting as physical barriers to coalescence [9]. | Includes silica, carbon, or clay nanoparticles. Mechanism is complex and area of ongoing research. Can worsen properties if not properly dispersed [9]. |

| Common Solvents | Medium for solution blending and characterization techniques (DLS, viscosity) [10]. | Must be a solvent for all polymer components (e.g., Benzene for PS/PMMA). Residual solvent can plasticize blend and affect properties. |

| Model Drugs & Polymers (Pharma) | Used in screening and developing Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) and Crystalline Solid Dispersions (CSDs) [12] [11]. | Drugs: Bifonazole (BFZ), Metoprolol, Paracetamol. Polymers: Poloxamers (P188, P407), PEG, Soluplus, PVA. Compatibility is critical for stability and performance [13] [11]. |

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What are the primary intermolecular forces that govern polymer blend compatibility?

The compatibility of polymer blends is primarily governed by three key intermolecular forces, listed here from strongest to weakest:

- Hydrogen Bonding: This is a strong dipole-dipole attraction that occurs when a hydrogen atom is bonded to a highly electronegative atom (N, O, or F) and is attracted to a lone pair on another electronegative atom. [15] [16] It is directional and can significantly improve blend miscibility by providing strong, specific interactions between different polymer chains. [17]

- Dipole-Dipole Interactions: These are electrostatic forces between the positive end of one permanent molecular dipole and the negative end of another. [18] [19] While weaker than hydrogen bonds, these Keesom interactions help align polymer chains and increase attraction, improving compatibility between polar polymers. [16]

- Ionic Forces: These are the strongest non-covalent interactions, occurring between fully charged cationic and anionic sites, often referred to as ion pairing or salt bridges. [15] [16] The association is essentially electrostatic and can be a powerful driver for compatibility in polymer systems containing ionic groups. [16]

Q2: What is the practical difference between a miscible blend and a compatible blend?

In polymer science, "miscible" and "compatible" have distinct technical meanings:

- Miscible Blend: This is a homogeneous, single-phase mixture at the molecular level. Miscible blends are typically optically transparent and exhibit a single glass transition temperature (Tg) that is composition-dependent. [1] An example is the blend of poly(phenylene ether) (PPE) and polystyrene (PS). [1]

- Compatible Blend: This is an immiscible, multi-phase blend where the different polymers are not mixed at the molecular level. However, through strategies like compatibilization, the interfacial tension between the phases is reduced, and the interfacial adhesion is strengthened. [1] This results in a stable morphology, finer dispersion of phases, and good mechanical properties. Most high-performance commercial polymer blends are actually compatibilized immiscible blends. [1]

Q3: How can I experimentally determine which intermolecular forces are active in my polymer blend?

Researchers use a suite of characterization techniques to probe intermolecular interactions, as demonstrated in studies on blends like polyethersulfone/polyetherimide (PES/PEI): [17]

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Can detect shifts in absorption peaks for functional groups (e.g., C=O, O-H, S=O) that indicate the formation of hydrogen bonds or other dipole-dipole interactions. [17]

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measures the glass transition temperature (Tg). A single, composition-dependent Tg suggests miscibility, while two distinct Tg values indicate immiscibility. Shifts in Tg can also signal intermolecular interactions. [1] [17]

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Reveals surface chemical composition and can identify changes in the electronic state of elements involved in specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonding. [17]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Phase Separation and Poor Mechanical Properties

- Symptoms: The blended material is opaque, has a coarse texture, delaminates easily, or exhibits brittle fracture.

- Underlying Cause: The polymer blend is immiscible with weak interfacial adhesion, leading to large domain sizes and poor stress transfer between phases. [1]

- Solutions:

- Incorporation of a Compatibilizer: Add a block or graft copolymer where one block is miscible with one polymer phase and the other block is miscible with the other phase. This acts as a molecular "stitcher" at the interface, reducing interfacial tension and stabilizing the morphology. [1]

- Reactive Compatibilization: Functionalize the base polymers with reactive groups (e.g., anhydride, epoxy) that can form covalent bonds in-situ during melt blending, creating a graft copolymer at the interface. [1] [20]

- Optimize Processing Parameters: Adjust melt temperature, shear rate, and mixing time during processing to control the dispersion and size of the phase-separated domains.

Problem 2: Void Formation and Dewetting in Highly Filled Blends or Composites

- Symptoms: Microscopic or macroscopic voids, bubbles, or cracks within the material, especially near filler particles.

- Underlying Cause: Poor chemical compatibility (wetting) between the polymer matrix and the filler particle surface, leading to dewetting under stress or during processing. [21] This can be due to a mismatch in polarity or surface energy.

- Solutions:

- Surface Functionalization of Fillers: Treat the filler particles with coupling agents or surfactants to modify their surface chemistry, improving adhesion with the polymer matrix. [21] For example, introducing functional groups that can form hydrogen or ionic bonds with the polymer.

- Use of a Coupling Agent: Introduce a chemical agent that has one end compatible with the polymer and another end that can bond to the filler surface. [21]

- Process Optimization: Adjust processing conditions to minimize air entrapment and ensure complete wetting of the filler by the polymer melt. [21]

Quantitative Data on Intermolecular Forces

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the intermolecular forces relevant to polymer blend compatibility.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Intermolecular Forces in Polymer Blends

| Force Type | Relative Strength | Origin | Key Functional Groups/Components | Impact on Blend Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Forces | Strongest | Attraction between fully charged cations and anions. [15] | Polymers with ionic groups, salt bridges. [16] | Can dramatically increase blend cohesion and thermal stability. [15] |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Strong | H atom covalently bonded to N, O, or F attracted to a lone pair on another N, O, or F. [15] [16] | -OH, -NH, -COOH, C=O, S=O, etc. [17] | Greatly enhances miscibility, mechanical strength, and can be used to construct controllable blends. [17] |

| Dipole-Dipole | Moderate | Attraction between partial charges on permanent molecular dipoles. [18] [19] | C-Cl, C=O (in some contexts), C≡N. [19] | Improves alignment and attraction between polar polymer chains, aiding compatibility. |

| London Dispersion | Weakest | Attraction from instantaneous, temporary dipoles due to electron cloud fluctuations. [15] [19] | Present in all atoms and molecules; strength increases with molecular weight/surface area. [15] | The default attractive force in non-polar polymers; contributes to background cohesion. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Compatibility via Solution Blending and DSC/FTIR Analysis

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study PES/PEI blend membranes. [17]

1. Aim: To prepare a polymer blend via solution blending and characterize its compatibility and intermolecular interactions through thermal and spectroscopic analysis.

2. Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Polymer A (e.g., PES) | Primary blend component, contains hydrogen bond acceptor groups (sulfone group). [17] |

| Polymer B (e.g., PEI) | Secondary blend component, contains groups capable of interaction (e.g., for hydrogen bonding). [17] |

| Solvent (e.g., DMAc) | A common solvent to dissolve both polymers for homogeneous solution blending. [17] |

| Non-solvent (e.g., Water) | Used as a coagulation bath to precipitate the polymer blend during phase inversion. [17] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | To measure the glass transition temperature(s) (Tg) and determine blend miscibility. [17] |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR) | To identify functional groups and detect shifts in absorption peaks that indicate specific interactions. [17] |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Solution Preparation. Dry the polymer pellets thoroughly. Dissolve predetermined weight ratios of Polymer A and Polymer B in a common solvent (e.g., DMAc). Stir the mixture mechanically for several hours (e.g., 12 hours) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 60°C) until a homogeneous, bubble-free solution is obtained. [17]

- Step 2: Blend Formation. Pour the solution into a petri dish or use a spin coater to create thin films. Alternatively, for hollow fiber membranes, use a spinneret to extrude the solution into a non-solvent (water) coagulation bath. [17] Allow the solvent to evaporate or the precipitate to form fully.

- Step 3: Washing and Drying. Wash the resulting blend films or fibers repeatedly with deionized water to remove residual solvent. Dry the samples completely in a vacuum oven at a moderate temperature before characterization. [17]

- Step 4: Characterization.

- DSC Analysis: Seal ~8 mg of the dried blend in an aluminum pan. Run a heat-cool-heat cycle from room temperature to above the expected Tg (e.g., 400°C) at a standard rate (e.g., 10°C/min) under a nitrogen atmosphere. Analyze the second heating curve for the number and position of Tg transitions. [17]

- FTIR Analysis: Place a small piece of the blend film on the ATR crystal. Collect spectra in the range of 4000 cm⁻¹ to 600 cm⁻¹. Compare the spectra of the blend to those of the pure polymers, paying close attention to the shifts in peaks associated with functional groups like C=O, O-H, or S=O. [17]

4. Data Interpretation:

- DSC: A single, sharp Tg that lies between the Tg values of the pure components suggests a miscible blend. Two distinct Tg values indicate phase separation. [1]

- FTIR: A shift in the absorption peak of a functional group (e.g., a shift to a lower wavenumber for the C=O stretch) is strong evidence of a specific intermolecular interaction, such as hydrogen bonding. [17]

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Intermolecular Forces Hierarchy

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Blend Analysis

Fundamental Concepts FAQ

What is the glass transition temperature (Tg) and why is it critical for polymer blends?

The glass transition (Tg) is the temperature range where a polymer transitions from a hard, glassy state to a softer, rubbery state. This is not a single point but a temperature range heavily influenced by factors like polymer crystallinity, crosslinking, and plasticizers [22]. In polymer blend research, determining the Tg is vital for quality control, predicting product performance, and informing processing conditions. For blends, the presence of a single Tg often indicates good miscibility, while multiple distinct Tgs suggest a phase-separated, immiscible system. Therefore, accurate Tg measurement is a cornerstone for assessing blend compatibility [22] [20].

How does morphological analysis complement Tg data in compatibility research?

Morphological analysis directly visualizes the blend's structure. Most biopolymer pairs, for instance, are intrinsically immiscible, leading to phase separation and poor properties [20]. While Tg data can suggest miscibility, microscopy techniques (e.g., SEM, TEM) reveal the size, shape, and distribution of these phases. Effective compatibilization improves interfacial adhesion and refines the phase morphology, which in turn enhances mechanical properties. This synergy between thermal analysis (Tg) and morphological observation is essential for developing optimized polymer blends [20].

Measurement Techniques FAQ

What are the primary methods for measuring Tg via Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)?

DMA measures Tg by applying a small-amplitude oscillation to a sample while ramping temperature and monitoring the dynamic moduli. There are three common ways to determine Tg from DMA data [22]:

- Onset of Storage Modulus (E' or G' Drop): This is the temperature at which the material begins to soften significantly and is typically the lowest Tg value. It indicates the upper useable temperature for a load-bearing material [22].

- Peak of Loss Modulus (E" or G" Peak): This peak corresponds to the temperature where energy dissipation is maximized, indicating large-scale cooperative motion of polymer chains [22].

- Peak of Tan(δ): Tan(δ) is the ratio of the loss modulus to the storage modulus. Its peak identifies the temperature where the material has its most viscous response [22].

The following table summarizes these methods:

Table: Primary Methods for Determining Tg from DMA/Rheology Data

| Analysis Method | Measured Parameter | Physical Significance | Reported Tg Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset Method | The onset of the drop in Storage Modulus (E' or G') | Temperature where mechanical strength begins to decrease; useful for load-bearing applications. | Typically the lowest |

| Loss Modulus Peak | The peak temperature of the Loss Modulus (E" or G") | Temperature of maximum energy dissipation, related to large-scale polymer chain motion. | Intermediate |

| Tan(δ) Peak | The peak temperature of Tan(δ) | Temperature where the material exhibits its most viscous response to deformation. | Typically the highest |

How do I choose between DSC and DMA for Tg characterization?

While both techniques measure Tg, DMA and rheological methods are generally more sensitive to the glass transition than Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [22]. A transition that is difficult to detect via DSC may be easily analyzed with DMA. DMA provides direct measurement of mechanical property changes (modulus) associated with the transition, whereas DSC measures the heat flow change. For compatibility research, DMA's sensitivity makes it excellent for detecting subtle transitions in blends, even when the DSC signal is weak or broad.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Tg via DMA Temperature Ramp

This protocol outlines the key steps for determining the glass transition temperature of a polymer blend using a Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare specimens of specific dimensions suitable for the DMA clamp system (e.g., torsion, dual cantilever, or three-point bend). For rheometry, prepare disks for parallel-plate geometry.

- Ensure the sample surface is smooth and flat for uniform clamping and stress distribution.

Instrument Setup:

- Install the appropriate clamps and calibrate the instrument according to manufacturer guidelines.

- Carefully mount the specimen, ensuring good contact and a known, pre-tightened torque or normal force.

- Select a temperature control environment (e.g., forced convection oven) and ensure the temperature sensor is correctly positioned.

Method Definition:

- Deformation Mode: Select the appropriate mode (torsion, tension, bending for DMA; shear for rheology).

- Oscillation Frequency: Select a frequency (e.g., 1 Hz). Note that the measured Tg will increase with increasing frequency.

- Strain/Stress Amplitude: Set a small amplitude within the linear viscoelastic region to ensure the material's structure is not damaged.

- Temperature Profile:

- Equilibrate at a starting temperature well below the expected Tg.

- Ramp the temperature at a constant rate (e.g., 2°C/min) to a final temperature well above the Tg. Validation Note: The ramp rate must be validated to avoid thermal lag. Compare results from a ramp with a temperature sweep (equilibrating at each temperature) to ensure data fidelity, especially for larger or more insulating samples [22].

Data Collection:

- Monitor and record storage modulus (E' or G'), loss modulus (E" or G"), and tan(δ) as functions of temperature.

Data Analysis:

- Use the instrument's software to identify the Tg using the three methods described above.

- For the onset method, tangents are drawn to the glassy plateau and the transition region of the storage modulus; their intersection is the onset Tg [22].

- For the loss modulus and tan(δ) methods, simply identify the temperature at the peak maximum [22].

The workflow for this experiment and subsequent analysis is outlined below:

Diagram 1: DMA/Rheology Experimental Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Broad or Indistinct Tan(δ) and Loss Modulus Peaks

- Potential Cause 1: Inherently broad transition due to material heterogeneity. Polymer blends, especially immiscible or poorly compatibilized ones, can have broad and overlapped transitions.

- Solution: Deconvolute the peaks if possible. Correlate with morphological analysis (e.g., SEM) to confirm phase separation. Reconsider the blend formulation and apply compatibilization strategies [20].

- Potential Cause 2: The presence of plasticizers, additives, or low molecular weight fractions can broaden the transition.

- Solution: Review the material formulation. Consider using a more sensitive technique like DMA over DSC, as it may better resolve the transition [22].

- Potential Cause 3: Excessive heating rate causing thermal lag.

- Solution: Reduce the temperature ramp rate (e.g., from 5°C/min to 2°C/min) and compare the results to an isothermal temperature sweep to validate that thermal lag is minimized [22].

Problem: Inconsistent Tg Values Between replicate Experiments

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent sample preparation leading to variations in sample dimensions, surface contact, or thermal history.

- Solution: Standardize the sample preparation protocol (molding, cutting) and ensure identical dimensions and clamping torque/force for all samples.

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect temperature calibration or significant thermal lag.

- Solution: Calibrate the temperature sensor. For larger or insulating samples, use a slower ramp rate or switch to a temperature sweep mode with equilibration steps to ensure the sample is at the set temperature [22].

- Potential Cause 3: The analysis method for the onset Tg is subjective.

- Solution: If using the storage modulus onset, ensure the same mathematical method (e.g., manual tangent vs. inflection point) is used consistently across all experiments. For better reproducibility, consider reporting the peak tan(δ) or loss modulus temperature alongside the onset [22].

The logical process for diagnosing measurement issues is as follows:

Diagram 2: Tg Measurement Troubleshooting Logic Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and reagents used in polymer blend compatibility research, particularly for modifying phase behavior and morphology.

Table: Essential Materials for Polymer Blend Compatibilization Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Rationale | Example in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Block or Graft Copolymers | Non-reactive compatibilizer; acts as a molecular "stitch" at the interface of immiscible polymer phases, reducing interfacial tension and stabilizing morphology [20]. | Used to compatibilize PLA/PBAT blends, improving ductility and impact resistance [20]. |

| Reactive Compatibilizers | Chemicals that form covalent bonds with the polymer chains in-situ during melt blending, creating a graft or block copolymer at the interface. Often more effective than non-reactive methods [20]. | Anhydride-functionalized polymers reacting with the amine end group of polyamides. |

| Aminated Polymers | A specific type of reactive compatibilizer where the amine group can react with functional groups (e.g., anhydride, epoxy) on another polymer chain [23]. | Used in reactive blending of immiscible polymers like polyamide and polyolefins. |

| Saturated Phospholipids (e.g., DPPC, DSPC) | Used in liposomal or biomaterial blends to create more rigid, stable structures with higher phase transition temperatures (Tm), minimizing permeability and drug leakage [24]. | Creating stable liposomal nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery [24]. |

| Unsaturated Phospholipids | Imparts fluidity and flexibility to lipid bilayers in biomaterial blends, leading to enhanced permeability and lower phase transition temperatures [24]. | Formulating flexible liposomes for enhanced fusion or release properties [24]. |

| Functional Nanoparticles | Compatibilizes blends by localizing at the polymer-polymer interface, preventing droplet coalescence. Can also impart additional functionality like barrier or flame-retardant properties [20]. | Silica nanoparticles used to compatibilize PLA/elastomer blends, simultaneously improving toughness and modulus [20]. |

This technical support center addresses the frequent experimental challenges of interfacial tension and phase separation instability encountered in polymer blend research. Designed for researchers and scientists, the following guides and FAQs provide targeted troubleshooting to improve the compatibility and final properties of polymer blends, directly supporting advanced research and drug development applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary thermodynamic drivers of phase separation in polymer blends?

Phase separation occurs due to a combination of entropic and enthalpic factors. The Flory-Huggins theory describes the free energy of mixing (ΔFmix) as ΔFmix = kT[(ΦA/NA)lnΦA + (ΦB/NB)lnΦB + χΦAΦB], where Φ is volume fraction, N is degree of polymerization, and χ is the Flory interaction parameter [25]. The entropic contribution (the first two terms) becomes less favorable as polymer chain length (N) increases. The enthalpic contribution, driven by the χ parameter, is unfavorable when χ is positive. Phase separation begins when the second derivative of ΔF_mix with respect to composition becomes negative, making the system unstable. This often occurs via spinodal decomposition, leading to co-continuous phases [25].

FAQ 2: How does polydispersity affect the interfacial tension of a polymer blend?

Polydispersity can significantly lower interfacial tension. Lower molecular weight fractions within a polydisperse polymer are less fractionated between the two phases and can accumulate at the interface [26]. This excess of small polymer molecules partially displaces solvent (e.g., water) at the interface, reducing the interfacial tension. One study on aqueous dextran/gelatin systems showed that adding 20 kDa dextran to a blend of 70 kDa dextran and 100 kDa gelatin consistently lowered the interfacial tension compared to the system with only the larger dextran [26].

FAQ 3: Can diffusion processes during an experiment alter measured interfacial tension values?

Yes, diffusion can cause transient effects that interfere with measurements. In immiscible blends like polyisobutylene/polydimethylsiloxane, a drop of one polymer in another may shrink due to diffusion. This shrinkage can be accompanied by a measurable increase in interfacial tension over time until a plateau is reached. This effect is attributed to the selective migration of polymer chains, which enriches the drop in higher molar mass material and increases its viscosity [27].

FAQ 4: What strategies can improve compatibility without synthesizing new compatibilizers?

Several in-situ strategies leverage the intrinsic properties of the blend components:

- Chemical Interactions: Promoting transreactions, hydrolytic reactions, or hydrogen bonding between the blend components [28].

- Physical Interactions: Utilizing the ability of components to form co-crystals or transcrystalline layers at the interface [28].

- Reversibly Crosslinked Networks: Using vitrimers (reversibly crosslinked polymers) can aid compatibilization. The crosslinkers' size and interaction with the base polymer are crucial. Chemically incompatible crosslinkers tend to segregate to interfaces, reducing interfacial tension and improving blend compatibility [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Uncontrolled Phase Separation Morphology

Issue: The phase-separated structure is random or coarsely structured, leading to poor mechanical properties or performance.

Solution: Implement methods to direct the morphology.

- Periodic Irradiation: For photoreactive blends, applying periodic light exposure can control the width of the spinodal patterns during phase separation [25].

- Holographic Patterning: Using holographic polymerization can direct the phase-separated structure to replicate the holographic interference pattern [25].

- Non-linear Optical Patterns: Non-linear optical patterns formed in photopolymer systems can template the organization of blends to match the light pattern [25].

Experimental Protocol: Controlling Morphology with Light

- Prepare Blend: Create a homogeneous mixture of photoreactive monomers/polymers and a liquid crystal or other immiscible component.

- Design Light Pattern: Define the desired final morphology using a holographic setup, photomask, or a system capable of generating non-linear optical patterns.

- Induce Phase Separation: Initiate polymerization using a UV light source. The light pattern will induce a spatially controlled reaction rate, directing the phase separation process via Polymerization-Induced Phase Separation (PIPS).

- Analyze Morphology: Use microscopy (e.g., SEM, AFM) to characterize the resulting periodic or patterned structure.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this protocol:

Problem 2: Inconsistent Interfacial Tension Measurements

Issue: Measured interfacial tension values are not reproducible or show time-dependent drift.

Solution: Control experimental variables related to polymer composition and measurement environment.

- Account for Polydispersity: Characterize the molar mass distribution of your polymers. Be aware that low molar mass fractions can lower the measured interfacial tension [26].

- Allow System Equilibrium: After creating a sample for measurement (e.g., a drop in a matrix), allow sufficient time for diffusion processes to equilibrate, especially if the polymers have a nonzero mutual solubility [27].

- Standardize Method: Use a consistent and well-understood measurement technique, such as the analysis of the interfacial profile near a vertical wall to determine the capillary length [26].

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Interfacial Tension via Capillary Length

- Phase Separation: Prepare the polymer blend and allow it to phase-separate completely. Centrifuge if necessary to obtain two clear, distinct phases [26].

- Density Measurement: Precisely measure the mass density of each isolated phase using an oscillating U-tube density meter [26].

- Form Interface: In a cuvette, carefully layer the isolated top phase onto the isolated bottom phase to create a sharp, clean interface [26].

- Image Profile: Place the cuvette in a rotated microscope with a horizontal optical path. Capture a high-resolution image of the meniscus of the interface where it contacts the vertical wall of the cuvette [26].

- Fit Data: Extract the interfacial profile coordinates (distance from wall

x, elevationz) from the image. Fit the profile to the equation:z = h [1 - ln(sec(x/h) + tan(x/h))], wherehis the capillary length [26]. - Calculate: Compute the interfacial tension

γusing the fitted capillary lengthhand the measured density differenceΔρwith the formula:γ = (Δρ * g * h^2)/2, wheregis gravitational acceleration [26].

Problem 3: Component Immiscibility Leading to Poor Properties

Issue: Blend components are highly immiscible, resulting in weak interfaces and delamination.

Solution:

- Use Compatibilizers: Introduce a third component, such as a block copolymer, that is miscible with both blend phases. This locates at the interface and reduces interfacial tension, stabilizing the blend morphology [28].

- Promote Specific Interactions: Select polymer pairs capable of forming favorable interactions like hydrogen bonding or that can undergo transreactions at the interface to create in-situ compatibilizers [28].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Interfacial Tension in Aqueous Polymer Systems

Data on the effect of polydispersity on interfacial tension (γ) in aqueous dextran/gelatin systems. Tie-line length is a measure of the difference in polymer concentration between the coexisting phases [26].

| System Composition (Dextran/Gelatin) | Tie-Line Length (Mass Fraction) | Interfacial Tension γ (μN/m) | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70 kDa Dextran / 100 kDa Gelatin | 0.135 | ~12 | Capillary length / Wall profile |

| 70 kDa Dextran / 100 kDa Gelatin | 0.155 | ~17 | Capillary length / Wall profile |

| 70 kDa + 20 kDa Dextran / 100 kDa Gelatin | 0.135 | ~9 | Capillary length / Wall profile |

| 70 kDa + 20 kDa Dextran / 100 kDa Gelatin | 0.155 | ~12 | Capillary length / Wall profile |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Phase Separation Mechanisms

A comparison of the two primary pathways for phase separation in polymer blends [25].

| Characteristic | Nucleation and Growth | Spinodal Decomposition |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Occurs in metastable region | Occurs in unstable region |

| Energy Barrier | Has a free energy barrier | No free energy barrier |

| Initial Morphology | Discrete spherical domains | Interconnected co-continuous domains |

| Process Dynamics | Domain size increases, number decreases | Wavelength of composition fluctuation is initially constant, then grows |

| Common in PIPS | Less common | More common |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Blend Experiments

Essential materials and their functions for studying phase separation and interfacial tension.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyisoprene (PI) & Poly(4-ethylstyrene) (PSt) | Model unentangled polymers with different mobilities and dielectric properties for studying dynamics [30]. | Studying time-dependent friction coefficients during phase separation [30]. |

| Dextran & Gelatin | Model polymers for creating aqueous two-phase systems (water-in-water emulsions) with low interfacial tension [26]. | Investigating the effect of polydispersity on interfacial tension without oil phases [26]. |

| Vitrimers / Reversible Crosslinkers | Crosslinkers that undergo bond exchange; can segregate to interfaces to reduce tension and compatibilize blends [29]. | Improving compatibility in immiscible polymer blends without synthesizing new block copolymers [29]. |

| Flory-Huggins Interaction Parameter (χ) | A dimensionless parameter quantifying the enthalpic interaction energy between different polymer segments [25]. | Predicting blend miscibility and the onset of phase separation via thermodynamic models [25]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental thermodynamic process leading to phase separation, as described by the Flory-Huggins theory:

Advanced Compatibilization Techniques and Their Real-World Applications

Theoretical Foundations: How Compatibilizers Work

What is the fundamental role of a compatibilizer in polymer blends?

Compatibilizers are additives that mediate interactions between otherwise immiscible polymers. Their primary function is to reduce interfacial tension between different polymer phases and stabilize the blend morphology against coalescence during processing and use. This is necessary because most commercially available polymers are intrinsically immiscible due to unfavorable thermodynamic interactions, leading to phase separation and weak interfacial adhesion [28] [31]. Without compatibilization, these immiscible blends exhibit poor mechanical properties and structural instability.

Through what molecular mechanisms do compatibilizers operate?

Compatibilizers function through several distinct mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Interfacial Localization: Compatibilizers typically position themselves at the interface between immiscible polymer phases. This reduces the interfacial energy, leading to finer dispersion of the minor phase and stabilized morphology [31] [20].

- Chemical Bridging: Reactive compatibilizers form covalent bonds with both polymer phases during melt blending. For instance, in poly(L-lactide) (PLA) blends with engineering polymers, compatibilizers containing reactive groups (e.g., anhydride, epoxy) can chemically link to polymer chain ends, creating in-situ copolymers that act as molecular bridges [31].

- Physical Interactions: Non-reactive compatibilizers, such as block or graft copolymers, rely on physical interactions including hydrogen bonding, polar interactions, or chain entanglement. Each block of the copolymer is designed to be miscible with one of the blend components [28] [20].

- Steric Stabilization: Compatibilizers prevent the coalescence of dispersed droplets in the matrix through steric hindrance, which is particularly important during melt processing where shear forces are present [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

How do I diagnose insufficient compatibilization in my polymer blend?

Several characterization techniques can reveal insufficient compatibilization:

- Morphological Analysis: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of cryo-fractured surfaces shows coarse, phase-separated structures with large domains (typically >10 µm) and poor interfacial adhesion (holes, debonding) [31] [32].

- Thermal Analysis: Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) or Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) reveals distinct glass transition temperatures (Tg) for each polymer phase with minimal shift, indicating limited molecular-level interaction [32].

- Mechanical Performance: Poor ductility (low strain at break), brittle failure, and unsatisfactory impact strength in notched Izod tests are key indicators [31] [20].

- Dielectric Analysis: Thermally Stimulated Discharge (TSD) measurements show multiple relaxation peaks corresponding to each immiscible phase, as demonstrated in PVC/TPU blend studies [32].

Why does my compatibilized blend still exhibit poor mechanical properties despite fine morphology?

This common issue, where morphology appears optimized but properties don't improve, typically stems from:

- Insufficient Interfacial Adhesion: A fine dispersion alone is inadequate without strong interfacial bonding to transfer stress between phases. This occurs when the compatibilizer is present at the interface but lacks specific interactions (chemical or physical) with one or both phases [31] [20].

- Wrong Compatibilizer Architecture: The molecular weight of block copolymer compatibilizers might be too high or too low relative to the blend components, preventing proper chain entanglement or interfacial packing [28].

- Degradation During Processing: Excessive shear or temperature during melt blending (e.g., twin-screw extrusion) can degrade the compatibilizer or matrix polymers, particularly with biopolymers like PLA [31].

- Inadequate Compatibilizer Concentration: The interface may be partially saturated, leaving uncompatibilized regions that become failure initiation points [31].

What strategies can improve compatibility in biopolymer blends like PLA?

Biopolymers present specific compatibility challenges. Effective strategies include:

- Reactive Compatibilization: This is particularly effective for PLA blends. Incorporating reactive functionalities (e.g., glycidyl methacrylate, maleic anhydride, or isocyanates) that react with PLA's end groups during processing creates in-situ graft copolymers that significantly enhance interfacial adhesion [31] [20].

- Nanoparticle Compatibilizers: Adding nanoparticles (e.g., cellulose nanocrystals, silica, clays) that localize at the interface can physically compatibilize blends while potentially adding functionality like improved barrier properties or flame retardance [20].

- Plasticizer Addition: For brittle biopolymers like PLA, incorporating bio-based plasticizers (e.g., citrate esters, oligo(lactic acid)) can improve blend processability and interfacial diffusion, aiding compatibilization [31].

- Multi-component Systems: Combining PLA with flexible biopolymers like poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) in properly compatibilized systems can balance stiffness and toughness [20].

Quantitative Data: Compatibilizer Performance

Table 1: Performance Outcomes of Different Compatibilization Strategies in Selected Polymer Blends

| Polymer Blend System | Compatibilizer/Strategy | Key Performance Improvement | Optimal Loading | Testing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/PC | Transreaction | Improved impact strength and elongation at break | - | Tensile testing, Izod impact [31] |

| PLA/PBT | Organoclay nanoparticles | Enhanced thermal resistance (HDT) and tensile modulus | 1-3 wt% | DMA, TGA, tensile testing [31] |

| PVC/TPU | Bio-plasticizer (glycerol diacetate monolaurate) | Single relaxation peak in TSD; more homogeneous morphology; enhanced tensile properties | 50 php (with 20 php TPU) | TSD, DMA, SEM, mechanical testing [32] |

| PLA/PBAT | Reactive epoxy-functionalized chain extender | Major simultaneous improvements in elongation, strength, and impact resistance | 0.2-0.8 wt% | Tensile testing, impact testing [20] |

| General Automotive Polymers | HALS/benzotriazole UV stabilizers | Extended service life by up to 3000 h in accelerated weathering without modulus loss | - | Accelerated weathering tester [33] |

Table 2: Bio-based Additives as Potential Compatibilizers or Co-Additives

| Additive Name | Base Polymer | Function | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxidized Sunflower Oil (ESO) | PVC, PLA | Plasticizer | Reduces migration rates by 30-40% vs. phthalates | [33] |

| Acetylated-Fatty Acid Methyl Ester-Citric Acid Ester (AC-FAME-CAE) | PVC films | Plasticizer | Improved mechanical properties vs. traditional plasticizers | [32] |

| Glycerol diacetate monolaurate | PVC/TPU blends | Bio-plasticizer/Compatibilizer aid | Enhances flexibility and phase homogeneity; sourced from waste cooking oil | [32] |

| Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) | Various biopolymer blends | Nanoparticle Compatibilizer | Biobased, improves barrier properties and stiffness | [20] |

| Triethyl Citrate | PLA | Plasticizer | Improves ductility and impact strength (>10-20% concentration) | [31] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: Reactive Compatibilization of PLA/Engineering Polymer Blends

This protocol outlines the compatibilization of PLA with engineering polymers (e.g., PC, PET, PBT) via reactive extrusion, adapted from recent research [31].

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymers: PLA (e.g., Ingeo 3052D), engineering polymer (e.g., PC, PET, PBT)

- Reactive compatibilizer: Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-based copolymer, maleic anhydride (MA)-grafted polymer, or multifunctional epoxy compound (e.g., Joncryl ADR)

- Twin-screw extruder (co-rotating, L/D ≥ 40)

- Injection molding machine

- Standard characterization equipment (DSC, DMA, SEM, tensile tester)

Procedure:

- Pre-drying: Dry PLA and engineering polymer pellets in a vacuum oven at 80°C for at least 8 hours to prevent hydrolysis-induced degradation.

- Dry-blending: Manually pre-mix the dried pellets with the reactive compatibilizer (typically 0.2-2.0 wt%) in a bag.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the dry blend into a twin-screw extruder with a temperature profile ranging from 190°C (feed zone) to 230°C (die), depending on the engineering polymer's melting point. Use a screw speed of 200-300 rpm and a feed rate to achieve full screw capacity without surge.

- Strand Pelletizing: Cool the extruded strands in a water bath and pelletize.

- Injection Molding: Dry the pellets again and injection mold into standard test specimens (e.g., ASTM tensile bars, impact disks) using appropriate molding parameters.

- Characterization:

- Morphology: Analyze cryo-fractured and etched surfaces via SEM.

- Thermal Properties: Determine Tg and Tm by DSC.

- Mechanical Properties: Perform tensile (ASTM D638) and Izod impact (ASTM D256) tests.

- Rheology: Measure complex viscosity to assess reaction-induced chain extension/branching.

Protocol: Assessing Compatibility via Thermally Stimulated Discharge (TSD)

TSD is a sensitive technique for probing molecular mobility and blend compatibility, particularly effective for polar polymers like PVC/TPU blends [32].

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer blend samples (compression molded sheets, ~0.5 mm thickness)

- TSCII instrument (SETARAM) or equivalent

- Sputter coater for gold coating

- Helium gas and liquid nitrogen

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Compression mold blend sheets at appropriate temperature and pressure. Cut disk-shaped samples (diameter: 26 mm).

- Gold Coating: Sputter-coat samples with a thin gold layer (4-8 nm) under low-pressure argon to ensure conductive, gap-free surfaces and minimize partial discharge noise.

- Sample Mounting: Mount gold-coated sample in the TSD instrument's sealed chamber.

- Polarization: Evacuate and flush the chamber with helium. Heat the sample to polarization temperature (e.g., 120°C for PVC/TPU) and apply a polarizing electric field for a set time (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Freezing: Cool the sample to -120°C at a controlled rate (5°C/min) under continued field application, then remove the field.

- Depolarization: Heat the sample at a constant rate (5°C/min) while measuring the depolarization current.

- Data Analysis: Plot depolarization current versus temperature. A single, broadened relaxation peak suggests good compatibility, while multiple distinct peaks indicate phase separation.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Compatibilization Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiments | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Compatibilizers | Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-grafted polymers, Maleic anhydride (MA)-grafted polyolefins, Multifunctional epoxies | Form in-situ copolymers during melt blending; create covalent bonds across interface | PLA/engineering polymer blends; Polyolefin blends |

| Block Copolymers | PS-b-PMMA, PEO-b-PP, Custom-synthesized blocks | Physically compatibilize through segment entanglement; reduce interfacial tension | Model immiscible blends; industrial polymer pairs |

| Bio-based Plasticizers | Epoxidized soybean oil (ESBO), Citrate esters (e.g., triethyl citrate), Glycerol diacetate monolaurate | Increase molecular mobility; improve processability; aid dispersion | PVC blends; Brittle biopolymer formulations |

| Nanoparticles | Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), Organically modified clay, Silica nanoparticles | Localize at interface; provide physical barrier against coalescence; reinforce interface | Biopolymer blends; High-performance composites |

| Stabilizers | Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers (HALS), Benzotriazole UV absorbers | Prevent compatibilizer/polymer degradation during processing and service | All systems, especially for automotive/outdoor applications |

Visual Workflows: Experimental and Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Multifunctional role of compatibilizers in polymer blends

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for compatibilizer evaluation

Compatibilizer FAQ: Solving Key Research Challenges

What is a compatibilizer and how does it work?

A compatibilizer is a substance added to polymer blends to improve the compatibility between different polymers or between a polymer and an inorganic filler [34]. It acts as a polymeric surfactant, locating itself at the interface between the immiscible components [35]. Compatibilizers have a chemical structure that is compatible with at least one, and preferably both, of the primary phases in the blend [36]. They work by reducing interfacial tension, promoting finer phase dispersion, stabilizing the morphology against processing conditions, and enabling better stress transfer between phases, which improves mechanical properties [35] [37].

Reactive compatibilizers contain functional groups that can chemically react with the components of the mixture, forming covalent bonds. Examples include maleic anhydride, epoxy groups (e.g., glycidyl methacrylate), and carboxylic acid groups [35].

Non-reactive compatibilizers rely on intermediate polarity and physical interactions (Van der Waals forces) to improve adhesion between phases. These are often ethylene copolymers with acrylates (EMA, EEA, EBA) or terpolymers containing carbon monoxide and/or vinyl acetate [35].

Which compatibilizer should I use for blending polyolefins with polar polymers?

For blending polyolefins (PP, PE) with polar polymers like PET or PA, maleic anhydride-grafted polyolefins are highly effective. The anhydride groups react with hydroxyl or amine groups on the polar polymer, while the polyolefin backbone associates with the polyolefin phase [36] [37].

- PP-g-MA (Maleic Anhydride-grafted Polypropylene) is particularly effective for PP-based blends with polymers like PET [37].

- PE-g-MA is the preferred choice for polyethylene-based systems.

- Dosage typically ranges from 2-4% by weight, though optimization is required for each specific system [36].

How can I improve adhesion between polymers and inorganic fillers?

Silane and titanate coupling agents are specifically designed for polymer-filler compatibility [35].

- Silanes require active hydroxyl groups on the filler surface and are effective with silicate-type fillers, metal oxides, and hydroxides (e.g., glass fiber, mica, ATH). They are less effective with carbonates like calcium carbonate [35].

- Titanates overcome many silane limitations and can also couple to carbonates, carbon black, and other fillers that don't respond to silanes. They don't require water to react and provide processing benefits like plasticizing effects [35].

What are the common causes of optical defects in transparent recycled blends?

Optical defects like haze and yellowing in recycled polymer blends arise from several mechanisms [37]:

- Phase separation between immiscible polymers creates interfaces with different refractive indices that scatter light.

- Particle contamination in recycled feedstock introduces light-scattering sites.

- Chemical degradation from repeated processing, causing oxidation products that absorb light and cause yellowing.

- Crystallinity changes, where large spherulites in semicrystalline polymers (like PP) scatter light and increase haze.

Solutions include using appropriate compatibilizers to reduce phase size, melt filtration to remove contaminants, stabilizers to prevent degradation, and processing controls to manage crystallinity [37].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Phase Separation During Melt Processing

Issue: Visible phase separation occurs during extrusion or injection molding, leading to poor mechanical properties.

Solutions:

- Increase compatibilizer dosage within the 2-8% range, but avoid over-use which can impact other properties [36].

- Verify compatibilizer chemistry matches your polymer systems. For example, use PP-g-MA for PP blends, not PE-g-MA [36].

- Optimize processing parameters: Increase mixing time or screw speed to improve dispersion; adjust temperatures to ensure proper melting without degradation [36].

- Consider alternative compatibilizer: If maleic anhydride types aren't working, trial epoxy-functionalized (GMA) or other reactive types [36].

Problem: Degradation of Mechanical Properties

Issue: The blended material shows reduced impact strength or tensile properties compared to virgin polymer.

Solutions:

- Evaluate compatibilizer effectiveness: Poor interfacial adhesion fails to transfer stress. Try different compatibilizer chemistries or higher loading levels [36] [35].

- Check for over-processing: Excessive heat or shear during processing can degrade polymer chains. Reduce processing temperature or residence time [36].

- Verify filler treatment: When using filled systems, ensure coupling agents are properly applied to filler surfaces before incorporation [35].

- Assess morphology: Use microscopy to check phase size and distribution - finer, more uniform dispersion typically improves mechanical properties [37].

Problem: Poor Storage Stability in Modified Asphalt Binders

Issue: Phase separation occurs in recycled plastic-modified asphalt binders during high-temperature storage.

Solutions:

- Incorporated chemical compatibilizers such as maleic anhydride, polyphosphoric acid, or reactive polymers that enhance compatibility between plastic and asphalt [38].

- Maleic anhydride enhances polarity and reduces plastic crystallinity, improving compatibility [38].

- Clay minerals like organic montmorillonite support chemical bonding between asphalt binder and polymer [38].

- Optimize plastic type and content: Different plastics (LDPE, HDPE, PP, PS, PET) have varying compatibility with asphalt [38].

Commercial Compatibilizer Types and Vendors

Table 1: Common Compatibilizer Chemistries and Applications

| Compatibilizer Type | Reactive Groups | Recommended Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride (MA) [36] [34] | Maleic anhydride | Polyolefin blends with PA, PET; Wood-plastic composites | Highly reactive with hydroxyl and amine groups; Widely available |

| Epoxy-functionalized [36] [34] | Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) | PC blends, PET alloys | Broad reactivity with various functional groups; Good thermal stability |

| Carboxylic Acid [34] | Carboxylic acid | Polar polymer blends | Reacts with epoxy and hydroxyl groups |

| Oxazoline [34] | Oxazoline | Various polymer blends | Reacts with carboxylic acids; Good hydrolysis resistance |

| Silane-based [35] | Alkoxy silanes | Polymer-filler composites | Effective with silicate fillers and glass fiber; Improves moisture resistance |

| Titanate-based [35] | Neoalkoxy titanates | Polymer-filler composites | Works with carbonates and carbon black; No water required for reaction |

Table 2: Leading Compatibilizer Vendors and Specialties

| Vendor | Product Specialties | Key Strengths | Sustainability Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow [39] | Broad range for various polymers | Extensive product lines; Global support | Medium |

| Arkema [39] | Specialty compatibilizers | Innovative formulations; High-performance | Medium |

| Evonik [39] | Advanced formulations | Sustainability focus; Technical expertise | High |

| Clariant [39] | Eco-friendly compatibilizers | Environmental compliance; Engineering plastics | High |

| LG Chem [39] | Recyclability enhancers | Sustainable solutions; Innovation | High |

| SK [34] | Various compatibilizers | Market presence in Asia | Medium |

| Eastman [34] [39] | Specialty compatibilizers | Mechanical property enhancement | Medium |

| ExxonMobil [34] | Polyolefin-based | Strong in olefin polymers | Medium |

Experimental Protocols for Compatibilizer Evaluation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Compatibilizer Efficiency in Polymer Blends

Objective: Determine the effectiveness of different compatibilizers in immiscible polymer blends.

Materials:

- Base polymers (e.g., PP and PET)

- Candidate compatibilizers (e.g., PP-g-MA, PE-g-MA, epoxy-functionalized)

- Solvents for extraction tests

- Standard additives (stabilizers, antioxidants)

Methodology:

- Pre-dry polymers and compatibilizers to remove moisture (e.g., 80°C under vacuum for 12 hours).

- Prepare blends using twin-screw extruder with:

- Control blend (no compatibilizer)

- Test blends with 2%, 5%, and 8% compatibilizer loading

- Maintain consistent processing parameters (temperature profile, screw speed, feed rate) across all runs.

- Collect extrudate, water-quench, and pelletize.

- Prepare test specimens by injection molding.

Characterization:

- Mechanical testing: Tensile strength, elongation at break, impact strength (ASTM D638, D256)

- Morphological analysis: SEM of cryo-fractured surfaces to examine phase size and distribution

- Thermal analysis: DSC to determine thermal transitions and crystallinity

- Rheological testing: Melt flow index or dynamic rheology to assess processability

Protocol 2: Testing Storage Stability of Modified Asphalt Binders

Objective: Evaluate the effectiveness of compatibilizers in preventing phase separation in plastic-modified asphalt.

Materials:

- Base asphalt binder

- Recycled plastic (e.g., HDPE, PP, PET)

- Chemical compatibilizers (e.g., maleic anhydride, polyphosphoric acid, clay minerals)

- High-shear mixer

- Aluminum tubes for storage stability test

Methodology:

- Heat base asphalt to become fluid (typically 150-180°C).

- Incorporate plastic modifier (typically 4-8% by weight) using high-shear mixer at 4000-5000 rpm for 30-60 minutes.

- Add compatibilizer (0.5-3% by weight) during mixing.

- Pour homogeneous modified binder into aluminum tubes; seal ends.

- Vertical storage in oven at 163°C for 48 hours (simulating hot storage).

- Quickly remove and horizontally freeze at -20°C for 4 hours.

- Section into equal thirds (top, middle, bottom).

- Test each section for softening point (ASTM D36) and viscosity.

Interpretation:

- Good stability: Minimal difference in softening point (<2-3°C) between top and bottom sections.

- Poor stability: Significant difference in properties between top and bottom sections indicates phase separation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Compatibilizer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PP-g-MA [36] [37] | Reactive compatibilizer for polypropylene blends | Varying graft levels (0.5-2.0% MA) available; Higher graft levels typically more reactive |

| PE-g-MA [36] | Reactive compatibilizer for polyethylene blends | Essential for PE-based blends with polar polymers |

| Epoxy-functionalized polymers [36] [34] | Broad-spectrum compatibilizer | GMA-based types most common; React with carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine groups |

| Aminosilanes [35] | Coupling agent for fillers in polar polymers | Especially effective in polyamides and polycarbonates |

| Methacrylate silanes [35] | Coupling agent for unsaturated polyesters | Improve filler-matrix adhesion in thermosets |

| Organotitanates [35] | Coupling agent for carbonate fillers | Effective where silanes fail (CaCO₃, BaSO₄); Also act as catalysts |

| Polyphosphoric acid [38] | Compatibilizer for asphalt modification | Enhances high-temperature rheological properties |

| Clay minerals [38] | Nanocomposite compatibilizer | Organic montmorillonite promotes bonding in various systems |

Compatibilizer Selection Workflow

Polymer Blend Optimization Process

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using melt blending over other methods for industrial applications? Melt blending is environmentally benign due to the absence of organic solvents and is highly compatible with current industrial processes like extrusion and injection molding, making it ideal for large-scale production of polymer composites [40].

Q2: Why is compatibilization critical in polymer blends, and how is it achieved? Polymer components often have differing chemical natures, leading to thermodynamically driven phase separation (dephasing) and weak interfaces. Compatibilization addresses this, typically by adding a third component (a compatibilizer) or by leveraging the components' ability to participate in chemical interactions, such as transreactions, hydrogen bonding, or the formation of co-crystals [28].

Q3: My polymer blend after melt processing has poor mechanical properties. What could be the cause? This is often a symptom of poor compatibility between the blended polymers, resulting in significant phase separation. To enhance compatibility, consider incorporating a reactive compatibilizer. For instance, in PLA/PBAT blends, adding a dual epoxy-functional compatibilizer like Polypropylene glycol diglycidyl ether (PPGDGE) can create chemical "bridges" at the interface, reducing phase separation and significantly improving mechanical performance [41].

Q4: How can I prevent the degradation of my polymer or heat-sensitive additives during melt blending? Thermal degradation can occur if the processing temperature significantly exceeds the polymer's melting point. Carefully set and control the processing temperature. If degradation persists for heat-sensitive materials, consider alternative methods like solution blending, which operates at lower temperatures, though it introduces the challenge of solvent removal [40] [42] [43].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Filler Aggregation | High shear forces during melt blending causing filler damage or re-aggregation. | Optimize shear conditions: use low to medium-shear blending. Pre-treat fillers (e.g., grafting) to improve dispersion [40]. |

| Poor Interfacial Compatibility | Differing solubility parameters or polarity between polymer components [44]. | Use a compatibilizer. Select based on principles like comparable solubility parameter (Δδ < 0.2) or similar polarity [44] [41]. |

| Phase Separation in Blends | Immiscibility of polymers, leading to dephasing (e.g., in PLA/PBAT blends) [41]. | Introduce a reactive compatibilizer (e.g., epoxy-based) to chemically link the phases and reduce interfacial tension [41]. |

| Polymer Degradation | Processing temperature is too high [42]. | Precisely control temperature during melt blending to minimize thermal degradation [42]. |