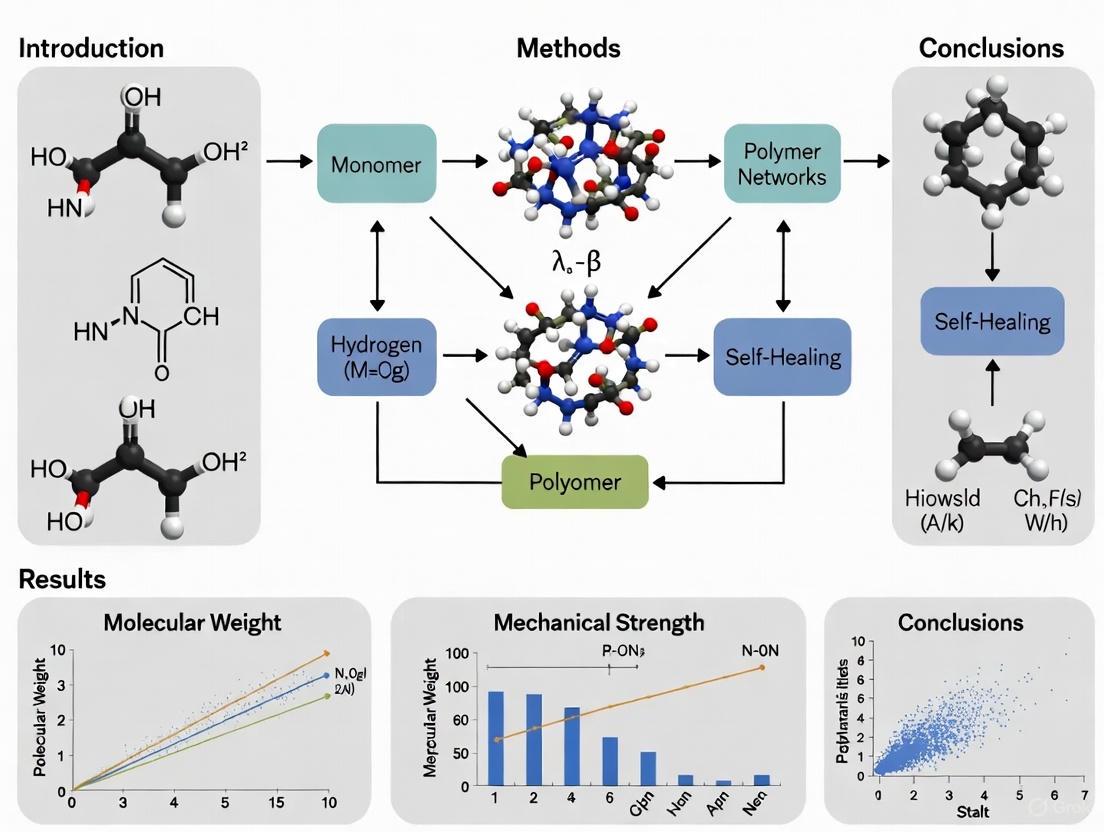

Supramolecular Polymer Design Principles: From Molecular Engineering to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of supramolecular polymer design principles, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Supramolecular Polymer Design Principles: From Molecular Engineering to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of supramolecular polymer design principles, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental non-covalent interactions governing self-assembly, including hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and host-guest chemistry. The content covers advanced fabrication methodologies for therapeutic applications, addresses critical stability and optimization challenges, and evaluates performance against conventional polymeric systems. By integrating recent advances and translational considerations, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing intelligent drug delivery platforms and personalized medicine solutions.

Molecular Blueprints: Core Principles and Driving Forces of Supramolecular Assembly

Supramolecular polymers (SPs) represent a rapidly advancing frontier in materials science, distinguished from their covalent counterparts by their reliance on directional and reversible non-covalent interactions between molecular building blocks [1] [2]. These dynamic bonds facilitate the self-assembly of complex, stimuli-responsive architectures with properties uniquely suited for biomedical applications, including drug delivery, tissue engineering, and diagnostic theranostics [1] [3] [2]. The design of these sophisticated materials is fundamentally governed by three essential non-covalent interactions: hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and host-guest chemistry. These interactions provide the foundational framework for creating functional supramolecular assemblies, enabling precise control over their structure, stability, and responsiveness to biological environments [1] [2]. This review dissects the principles, quantitative characterization, and experimental methodologies underlying these core interactions, providing a technical guide for their application in supramolecular polymer design.

Hydrogen Bonding: Directionality and Strength in Design

Fundamental Principles and Bonding Patterns

Hydrogen bonds are a principal class of supramolecular interaction, forming between a hydrogen atom bound to an electronegative donor (e.g., N, O, F) and an electronegative acceptor atom [4]. The strength and directionality of hydrogen bonds make them exceptionally powerful in dictating the assembly and final properties of supramolecular materials [1]. While single hydrogen bonds are relatively weak, their strength can be dramatically enhanced through the cooperative effect of multiple bonds, a strategy ubiquitously employed in nature and mimicked in synthetic systems [4].

Table: Hierarchy of Hydrogen Bonding Motifs in Supramolecular Polymers

| Motif Type | Representative Example | Typical Energy (kJ/mol) | Key Characteristics | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single H-bond | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydroxyl groups | 5 - 25 | Weak, dynamic; enables self-healing | Self-repairing PVA gels [4] |

| Double H-bond | N-acryloylglycinamide (NAGA) diamide | 20 - 40 | Enhanced stability & mechanical strength | High-toughness PNAGA hydrogels [5] [4] |

| Triple H-bond | Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA) | 40 - 60 | High directionality; forms columnar stacks | Triblock copolymers with 225% increased Young's modulus [4] |

| Quadruple H-bond | Ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) | 60 - 100 | Very strong, highly stable dimers | AA/BB-type supramolecular block copolymers [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

The investigation of hydrogen-bonded SPs typically involves a combination of spectroscopic, thermodynamic, and mechanical analyses.

Protocol 1: Monitoring Cooperative Supramolecular Polymerization via UV-Vis Spectroscopy This protocol is used for π-conjugated systems where H-bonding directs assembly, leading to changes in optical properties [1] [6].

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the hydrogen-bonding π-system (e.g., a porphyrin or PDI derivative) in a suitable solvent (e.g., methylcyclohexane, MCH) at a concentration of 50-100 µM. Ensure molecular dissolution by heating the solution above the elongation temperature (Te).

- Thermal Cycle: Place the solution in a temperature-controlled UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Cool the solution from the monomeric state (e.g., 363 K) to room temperature at a controlled rate (e.g., 1-10 K/min).

- Data Collection: Monitor the absorbance at a wavelength specific to the monomeric species (e.g., 515 nm for 2EH-PDI). A decrease in absorbance indicates supramolecular polymerization.

- Analysis: Plot the degree of polymerization (α) against temperature. The presence of a thermal hysteresis loop between the heating and cooling curves is a hallmark of a cooperative nucleation-elongation mechanism and pathway complexity [6].

Protocol 2: Mechanical Property Assessment of H-bonded Hydrogels This protocol evaluates the macroscopic outcome of H-bonding in bulk materials [5] [4].

- Gel Synthesis: Synthesize the polymer, such as poly-N-acryloylglycinamide (PNAGA), via free-radical polymerization in aqueous solution.

- Rheological Testing: Perform oscillatory rheology on the equilibrated hydrogel.

- Conduct a strain sweep (e.g., 0.1% - 100% strain) at a fixed frequency to determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

- Perform a frequency sweep (e.g., 0.1 - 100 rad/s) within the LVR to measure the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G''). A G' > G'' indicates solid-like gel behavior.

- Tensile Testing: Mold the gel into standardized dog-bone shapes. Use a universal testing machine to perform uniaxial tensile tests until fracture to determine elongation at break, toughness, and Young's modulus [4].

π-π Stacking: Electronic and Geometric Complementarity

Fundamentals and Energetic Landscape

π-π stacking interactions arise from the non-covalent attraction between aromatic rings, a key driver in the assembly of functional supramolecular polymers, particularly those based on π-conjugated systems like perylene diimides (PDIs) or porphyrins [1] [6]. The strength of this interaction is governed by the electron density of the π-orbitals, which can be tuned by substituents on the aromatic ring [7]. A critical design principle is the interplay between π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding; the presence of hydrogen bonds can lead to π-depletion in the aromatic ring, thereby strengthening the subsequent π-π stacking interaction [7].

Table: Representative π-Systems and Their Stacking Behavior in SPs

| π-System | Primary Interactions | Typical Morphology | Key Property | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perylene Diimide (PDI) | π-π stacking, dispersive interactions | 1D nanofibers, 2D platelets, 3D spherulites | Photostability, bright fluorescence | Living Supramolecular Polymerization (LSP) [1] [6] |

| Porphyrin Derivatives | π-π stacking, metal-ligand, H-bonding | J-aggregates, columnar stacks | Photocatalytic, electronic properties | Carrier for therapeutics [1] |

| Perylene Bisimides (PBIs) | π-π stacking (columnar) | Columnar stacks in solution | Fluorescence, electronic properties | Electronic & biological applications [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Protocol 3: Analyzing π-π Stacking via Concentration-Dependent UV-Vis Spectroscopy This method identifies the type of π-stacking (H- or J-aggregation) by spectral shifts [6].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions of the π-system (e.g., 2EH-PDI) in a non-polar solvent like MCH, with concentrations ranging from 1 µM to 100 µM.

- Spectral Acquisition: Record UV-Vis absorption spectra for each concentration at a constant temperature.

- Data Analysis: Identify the aggregation mode:

- H-aggregation: Characterized by a blueshift (hypsochromic shift) of the absorption maximum and the appearance of a higher-energy vibronic peak. This indicates a face-to-face stacking geometry.

- J-aggregation: Characterized by a sharp, redshifted (bathochromic shift) absorption band. This indicates a head-to-tail stacking geometry with exciton coupling.

Protocol 4: Pathway Complexity and Seeding Experiments This advanced protocol explores kinetic trapping and controlled assembly, often dependent on π-π interactions [6].

- Generate Dormant Monomers: Dissolve a molecule like 2EH-PDI in a solvent mixture (e.g., 90:10 MCH:DCE) and rapidly cool it from high temperature to room temperature to form a metastable, kinetically trapped monomeric state.

- Seed Preparation: Independently, prepare a solution of pre-assembled SPs (seeds) from the same or a different molecule (e.g., PE-PDI) by slow cooling.

- Activation: Add a small molar percentage (e.g., 1-5 mol%) of the seeds to the dormant monomer solution.

- Monitoring: Use UV-Vis spectroscopy or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to observe the growth of supramolecular polymers from the seeds, which can lead to controlled 1D architectures or complex heterostructures like scarf-like assemblies [6].

Diagram: Pathways in Supramolecular Polymerization. The assembly can proceed via primary nucleation-elongation to form 1D polymers, or via a secondary nucleation event, enabled by specific seeding, to form complex 3D architectures [6].

Host-Guest Chemistry: Molecular Recognition and Complexation

Core Concepts and Macrocyclic Hosts

Host-guest chemistry involves the specific binding of a guest molecule within the cavity of a host macrocycle through non-covalent interactions [8] [9] [3]. This molecular recognition is central to creating structurally well-defined and stimuli-responsive supramolecular systems. The binding affinity is quantified by the binding constant (Ka), where Ka = [HG]/([H][G]) [9]. The dynamic nature of this complexation allows for the dissociation of the host-guest linkage in response to specific stimuli present in disease microenvironments, such as pH, redox potential, or enzymes [3].

Table: Common Macrocyclic Hosts and Their Guest Partners

| Macrocyclic Host | Chemical Structure | Typical Guest Molecules | Primary Interactions | Key Applications in Theranostics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclodextrins (CDs) | Cyclic oligosaccharide with hydrophobic cavity | Hydrophobic drugs (e.g., Paclitaxel), alkyl chains | Hydrophobic, van der Waals | Drug solubility enhancement, polyrotaxanes, MRI contrast agents [3] |

| Cucurbit[n]urils | Cucurbit-shaped with polar portals and hydrophobic cavity | Cationic molecules, protonated amines | Ion-dipole, hydrophobic | Drug delivery, contrast agent platforms [3] |

| Pillar[n]arenes | Pillar-shaped with electron-rich cavity | Charged, neutral guests | π-π, CH-π, electrostatic | Stimuli-responsive drug release [3] |

| Calix[n]arenes | Basket-shaped with defined upper/lower rim | Ions, neutral molecules | Hydrogen bonding, π-π, ionic | Sensing, drug delivery [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Protocol 5: Determining Host-Guest Binding Constants via Fluorescence Titration This protocol is applicable when the complexation induces a change in the fluorescence intensity of the host or guest.

- Stock Solutions: Prepare a stock solution of the host macrocycle (e.g., a cyclodextrin) and the fluorescent guest molecule in a buffered aqueous solution.

- Titration: To a fixed concentration of the guest in a cuvette, sequentially add small aliquots of the host stock solution. Mix thoroughly and allow to equilibrate.

- Measurement: After each addition, record the fluorescence emission spectrum at a fixed excitation wavelength.

- Data Fitting: Plot the change in fluorescence intensity (e.g., at emission maximum) against the host concentration. Fit the data to a 1:1 binding model to extract the binding constant (Ka).

Protocol 6: Constructing a Polyrotaxane-Based MRI Contrast Agent This protocol outlines a supramolecular strategy to improve the performance of Gadolinium-based contrast agents [3].

- Host Modification: Covalently conjugate a Gd³⁺ chelate (e.g., DOTA or DO3A) to a cyclodextrin (CD) ring.

- Axle Threading: Mix the modified CD with a linear polymer axle (e.g., Pluronic F127) in aqueous solution. The hydrophobic segments of the axle thread through the CD cavities.

- Stoppering: Introduce bulky stopper molecules (e.g., cholesterol) to both ends of the polymer axle to prevent dethreading, forming a polyrotaxane.

- Characterization: Purify the polyrotaxane and characterize it via NMR and size-exclusion chromatography. Measure the longitudinal relaxivity (r1) at clinical field strengths (e.g., 1.5 T). The restricted motion of the Gd³⁺-loaded wheels within the polyrotaxane architecture typically results in a significant increase in r1 compared to the free chelate [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Supramolecular Polymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| N-acryloylglycinamide (NAGA) | Monomer forming double H-bond networks | Synthesis of high-strength, anti-swelling PNAGA hydrogels for tissue scaffolds [5] [4] |

| Ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) | Motif forming self-complementary quadruple H-bonds | Building block for AA/BB-type supramolecular block copolymers [1] |

| Perylene Diimide (PDI) Derivatives | π-conjugated core for stack-driven polymerization | Model system for studying nucleation-elongation & secondary nucleation [6] |

| Cyclodextrins (α, β, γ) | Macrocyclic hosts for hydrophobic guests | Improving drug solubility, constructing polyrotaxanes for drug delivery & imaging [3] |

| Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA) | Motif forming triple H-bonds & columnar stacks | Reinforcing triblock copolymers to enhance mechanical properties [4] |

Hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and host-guest chemistry are not merely isolated interactions but are often synergistically combined in sophisticated supramolecular polymer designs. The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of our understanding of their interplay, particularly under non-equilibrium conditions, to achieve spatiotemporal control over assembly and function within complex biological environments. The experimental frameworks and design principles outlined herein provide a foundation for the rational development of next-generation supramolecular materials for targeted therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Monomer Design Strategies for Directional Self-Assembly and Functional Integration

The field of supramolecular polymer science is founded on a powerful paradigm: the precise design of monomeric building blocks to dictate the structure, properties, and function of the resulting macroscopic materials. Unlike covalent polymers, supramolecular polymers are orchestrated through directional non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and host-guest complexation—that impart dynamic, reversible, and responsive characteristics [1] [10]. The inherent reversibility of these interactions allows supramolecular polymers to exhibit unique material properties, including heightened toughness, self-healing capabilities, and injectability due to shear-thinning behavior [1]. For biomedical applications, this translates to materials that can respond to physiological cues, facilitate natural body clearance without chemical breakdown, and mimic the sophisticated functions of biological systems [1] [11]. The foundational principle governing this bottom-up assembly is that the emergent properties of the supramolecular construct—its adaptability, reversibility, and tunability—are directly encoded in the chemical structure and interactive motifs of its individual molecular components [1]. This guide details the core strategies for designing these molecular blueprints to achieve controlled directional self-assembly and seamless functional integration for advanced applications.

Core Monomer Design Principles for Directional Assembly

The journey toward a functional supramolecular architecture begins with the strategic design of its monomeric units. Several key principles must be considered to ensure successful directional self-assembly into the desired one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures.

The Imperative of Directionality

The primary feature of a successful monomer is directionality. The arrangement of interactive sites on the molecular scaffold must guide the assembly pathway linearly, favoring the formation of 1D supramolecular polymers over disordered aggregates [1]. This is often achieved through a C3-symmetric core, such as Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA), which promotes the formation of helical columnar stacks through a combination of three-fold hydrogen bonding and π-stacking interactions [10]. Similarly, cyclic peptides with an alternating sequence of D- and L-amino acids adopt a flat, ring-like conformation that directs stacking through backbone hydrogen bonds, creating nanotubular structures [12].

Mastering Thermodynamics and Kinetics

Supramolecular polymerization is a process governed by a delicate balance between thermodynamics and kinetics. The design must consider the free energy landscape of the assembly process. Monomers can be designed to follow an isodesmic (non-cooperative) or a nucleation-elongation (cooperative) mechanism [1]. In aqueous systems, pathway complexity often leads to kinetically trapped states, which can be avoided by design strategies that favor thermodynamic equilibrium [11]. For instance, incorporating hydrophilic segments in Peptide Amphiphiles (PAs) manages the interplay between hydrophobic collapse (driving aggregation) and electrostatic repulsion or hydrogen bonding (guiding specific structure), enabling the formation of nanofibers with a defined β-sheet core [11].

Table 1: Key Interactions in Monomer Design and Their Functional Roles

| Interaction Type | Strength & Directionality | Role in Monomer Design | Example Motifs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | Moderate to High; Highly Directional | Creates stable, ordered structures; Stabilizes secondary structures (e.g., β-sheets) [1] [11]. | Ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) [1]; Peptide backbones [11] [12]. |

| π-π Stacking | Moderate; Directional | Drives columnar co-facial stacking of aromatic systems; Enhances electron delocalization [1] [10]. | Perylene Bisimides (PBI) [1]; Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA) [10]. |

| Host-Guest | Tunable (Low to High); Directional | Provides specific, orthogonal binding; Enables modular and stimuli-responsive assembly [1] [10]. | Cyclodextrin/Adamantane [10]; Crown ether/Ammonium ions [1]. |

| Metal-Ligand | High; Directional & Tunable | Introduects stimuli-responsiveness (redox, light); Imparts unique photophysical/electronic properties [10]. | Terpyridine/Zinc ions [10]; Porphyrin/metal coordination [1]. |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Weak; Non-directional | Major driver for assembly in water; Promotes micellization and nanofiber formation [11]. | Alkyl chains (e.g., C16 tail in PAs) [11]. |

The Role of the Aqueous Environment

Designing for biomedical applications necessitates assembly in an aqueous environment. This requires careful management of amphiphilicity. A classic strategy involves designing amphiphilic monomers that covalently link hydrophobic and hydrophilic structural units [10]. The hydrophobic segments (e.g., alkyl chains, aromatic cores) drive aggregation via the hydrophobic effect, while the hydrophilic parts (e.g., oligoethylene glycols, charged groups) ensure water solubility and can be used to modulate interaction with biological systems [11] [10]. The choice of hydrophilic group also allows for environmental responsiveness; for example, incorporating pH-sensitive amines or carboxylic acids enables control over assembly through protonation/deprotonation cycles [11].

Strategic Implementation of Non-Covalent Interactions

The strategic combination of non-covalent interactions is where monomer design transitions from concept to functional material. The following dot code and diagram illustrate the logical workflow for designing a monomer for directional self-assembly.

Hydrogen Bonding Arrays

Hydrogen bonds are prized for their high directionality and strength, making them ideal for creating stable structures. A powerful motif is the ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) group, which dimerizes with exceptionally strong and self-complementary quadruple hydrogen bonding [1]. This motif has been used to create supramolecular block copolymers by functionalizing polymer chain ends, allowing control over polymer composition and properties [1]. In peptide amphiphiles, hydrogen bonding among the peptide segments forms β-sheet secondary structures, which template the formation of long, highly ordered nanofibers central to their bioactivity [1] [11].

Aromatic Stacking and Host-Guest Chemistry

π-π stacking interactions between planar aromatic units provide a strong driving force for assembly and can facilitate charge transport. Perylene bisimides (PBIs) are a prime example, forming columnar stacks that exhibit photostability and bright fluorescence, properties valuable for both electronic and sensing applications [1]. Host-guest interactions, such as those between cyclodextrins (host) and adamantane (guest), offer a modular approach [10]. These interactions are highly specific and can be engineered to respond to stimuli like pH or temperature, making them excellent for creating drug delivery systems that release their payload under specific conditions [1] [10].

Metal-Ligand Coordination

Metal-ligand coordination bonds are highly directional and tunable, offering a route to introduce stimuli-responsiveness and unique electronic or optical properties. For instance, porphyrin molecules can self-assemble through a combination of π-π stacking and metal-ligand coordination, leading to structured supramolecular polymers with photofunctional characteristics [1]. The use of metal ions with different coordination geometries (linear, trigonal, octahedral) allows the design of complex supramolecular architectures beyond simple linear chains [10].

Advanced Design: From Homopolymers to Functional Co-Assemblies

Moving beyond homopolymers, the co-assembly of multiple monomers enables the creation of sophisticated multifunctional systems, akin to copolymers in covalent polymer science.

Sequence Control in Supramolecular Copolymers

The co-assembly of different monomers can lead to supramolecular copolymers with "blocky" or "random" sequences, which profoundly influence their dynamic behavior and final function. Recent studies using a combinatorial titration methodology on peptide amphiphiles revealed that sequence mismatch dictates nanostructure morphology [11]. Two-component systems with similar peptide sequences tend to form well-mixed copolymers with reduced internal phase separation and unique dynamics. In contrast, monomers with mismatched sequences tend to form "blocky" nanostructures that retain the dynamic characteristics of their parent homopolymers [11]. This control over the internal distribution of components is crucial for applications like multidrug delivery or creating materials with spatially segregated functions.

Integrating Bioactive Signals

A key advantage of supramolecular design is the ability to seamlessly integrate bioactive epitopes directly into the monomer structure. In peptide amphiphiles, a common design includes a hydrophobic tail, a β-sheet forming segment, and a hydrophilic bioactive sequence (e.g., RGD for cell adhesion) at the terminus [11]. Upon self-assembly, these signals are presented at high density on the nanofiber surface, effectively mimicking the natural extracellular matrix to direct cell behavior for regenerative medicine [1] [11]. This precise spatial presentation is often unattainable with traditional polymers.

Experimental Protocols for Assembly and Characterization

Validating the success of monomer design requires robust methodologies to probe the assembly process and the final architecture. The following diagram maps the key experimental workflow for characterizing aqueous supramolecular polymers.

Protocol: Combinatorial Titration for Aqueous Supramolecular Polymerization

This protocol, adapted from recent work in Nature Communications, is designed to map the assembly landscape of charged monomers (e.g., peptide amphiphiles) under thermodynamic equilibrium, avoiding kinetically trapped states [11].

Objective: To precisely induce and monitor the supramolecular polymerization of charged monomers in water by controlling pH.

Materials and Reagents:

- Monomer Stock Solution: Aqueous solution of the cationic peptide amphiphile (e.g., C₁₆V₃A₃K₃ at 20-500 µM).

- Acid Solution: Hydrochloric acid (HCl), concentration tailored to fully protonate the stock solution.

- Base Solution: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution for titration.

- Syringe Pump: For precise, low-rate addition of titrant (e.g., 0.5 mL/hour).

- Characterization Instruments: Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer, Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), NMR Spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Depolymerization: Add HCl to the monomer stock solution to fully protonate charged residues (e.g., lysine amines). This maximizes electrostatic repulsion, breaking pre-formed polymers and creating a solution of spheroidal micelles with random-coil conformations. Verify this state via CD (peak at ~195 nm) and TEM.

- Controlled Titration: Load the NaOH solution into a syringe pump. Titrate it into the acidic monomer solution at a defined, slow rate (e.g., 0.5 mL/hour). The slow rate is critical to maintain thermodynamic equilibrium.

- In Situ Monitoring: Continuously monitor the CD signal (e.g., molar ellipticity at 220 nm, θ₂₂₀ₙₘ) throughout the titration. The shift from a random coil to a β-sheet signature (negative Cotton effect at ~220 nm) indicates the formation of supramolecular polymers.

- Ex Situ Characterization: At key points in the titration (e.g., initial, transition, and final plateaus), extract aliquots for:

- TEM: To visualize the morphological transition from micelles to filamentous polymers/nanoribbons.

- SAXS: To obtain structural parameters and confirm the formation of 1D assemblies.

- NMR: To confirm the depletion of small, mobile micelles in the fully assembled state.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the CD titration curve to calculate the extent of polymerization (φ{β-sheets}), representing the molar fraction of monomers within β-sheet polymers. Plot φ{β-sheets} as a function of the [NaOH]/[Monomer] ratio and monomer concentration to construct a detailed assembly landscape.

Key Characterization Techniques and Their Information Output

A multi-technique approach is non-negotiable for a comprehensive understanding of supramolecular polymers.

Table 2: Essential Techniques for Characterizing Supramolecular Polymers

| Technique | Key Information | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Secondary structure evolution (random coil to β-sheet); Critical assembly concentration [11]. | Monitoring the real-time formation of β-sheets in peptide amphiphiles during NaOH titration [11]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Direct visualization of morphology (micelles, fibers, ribbons), size, and distribution [11]. | Confirming the presence of filamentous polymers and nanoribbons in the second plateau of the titration [11]. |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Nanoscale structural parameters (e.g., cross-sectional radius, length) in solution state [11]. | Providing quantitative data on the shape and dimensions of 1D assemblies complementary to TEM [11]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Mobility of monomers; Distinguishing assembled (NMR-silent) and disassembled (NMR-visible) species [11]. | Detecting the depletion of micelles in the fully assembled state by the absence of ¹H NMR signals [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key materials and reagents central to the design and analysis of monomers for directional self-assembly.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Supramolecular Polymer Science

| Reagent / Material | Function and Role in Monomer Design |

|---|---|

| Ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) | A self-complementary quadruple H-bonding motif used to create strong, reversible links between monomers, often as an end-group on polymer chains [1]. |

| Peptide Amphiphiles (PAs) | A class of molecules combining a hydrophobic alkyl tail with a peptide sequence. They are a versatile platform for creating bioactive nanofibers via β-sheet formation [1] [11]. |

| Cyclodextrins (CD) | Macrocyclic host molecules that form inclusion complexes with hydrophobic guests (e.g., adamantane). Used to create stimuli-responsive, modular assemblies [1] [10]. |

| Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA) | A C3-symmetric scaffold that forms columnar stacks via 3-fold H-bonding and π-stacking, serving as a classic core for 1D supramolecular polymers [10]. |

| Perylene Bisimides (PBI) | Planar, π-conjugated aromatic molecules that stack into columnar aggregates, providing electronic and optical functionalities such as fluorescence and charge transport [1]. |

| Cyclic Peptides (e.g., cyclo[-(D-Ala-L-Glu-)₂-]) | Planar cyclic structures that stack into nanotubes via backbone H-bonds. The sequence of D- and L-amino acids ensures a flat conformation [12]. |

The strategic design of monomers for directional self-assembly represents a convergence of molecular chemistry and materials science. By meticulously selecting core scaffolds and integrating specific, directional non-covalent interactions, researchers can encode the information required for monomers to spontaneously organize into complex and functional supramolecular polymers. The continued refinement of design principles—coupled with advanced experimental methodologies for probing assembly pathways—enables unprecedented control over the structure and properties of these dynamic materials. As the field progresses, the focus on functional integration, particularly for biomedical applications like targeted drug delivery and regenerative medicine, will continue to drive innovation in monomer design, pushing the boundaries of what is possible with supramolecular systems.

Thermodynamic versus Kinetic Control in Supramolecular Polymerization Pathways

Supramolecular polymers, polymeric arrays of repeating units connected by reversible non-covalent bonds, represent a rapidly advancing field bridging polymer science and supramolecular chemistry [13]. In contrast to covalent polymers, the dynamic nature of non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, host-guest interactions, and metal coordination—provides supramolecular polymers with unique characteristics such as stimulus responsiveness, self-healing capabilities, and recyclability [1] [13]. The self-assembly of monomers into these one-dimensional architectures can proceed through distinct mechanisms, but a particularly fascinating phenomenon is pathway complexity, where the same monomeric building blocks can form different supramolecular structures depending on the assembly conditions [14] [15]. This concept, systematically unraveled by Meijer and co-workers, highlights the competition between kinetics and thermodynamics in determining the final outcome of supramolecular polymerization [14].

Within the context of supramolecular polymer design principles, understanding the interplay between thermodynamic and kinetic control is paramount for developing advanced functional materials [14] [1]. The polymerization pathway taken can lead to structures with vastly different properties, morphologies, and functions, even from identical starting monomers [16] [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this interplay enables the rational design of supramolecular materials with tailored characteristics for specific biomedical applications, such as drug delivery systems, injectable hydrogels, and tissue engineering scaffolds [1]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and implications of thermodynamic versus kinetic control in supramolecular polymerization, providing a foundation for the informed design of next-generation supramolecular materials.

Fundamental Principles and Energetic Landscapes

Thermodynamic versus Kinetic Control: Conceptual Framework

In supramolecular polymerization, the final structure of the assembly is determined by the relative stability of possible aggregates and the energy barriers separating them [14] [17]. Thermodynamic control leads to the formation of the most stable aggregate, which resides at the global minimum of the free energy landscape [17]. This state represents the true equilibrium structure, unaffected by the pathway taken to reach it, and is characterized by its reversibility and self-repairing capabilities [17]. Under thermodynamic control, the system has sufficient time and mobility to explore its energy landscape and find the most favorable configuration [14].

Conversely, kinetic control results in the formation of metastable or kinetically trapped structures that reside in local minima of the free energy landscape [14] [17]. These non-equilibrium states are highly dependent on the preparation protocol, such as cooling rate, solvent processing, or order of component addition [17]. The kinetic product forms faster because it has a lower activation energy barrier for nucleation, even if it is less thermodynamically stable than other possible aggregates [14]. The system becomes trapped in this local minimum because the energy barrier to escape and reorganize into the thermodynamic product is too high to overcome under the given conditions [17].

Classification of Thermodynamic States

Supramolecular polymers can reside in four distinct thermodynamic states, each with characteristic properties and requirements [17]:

- Thermodynamic Equilibrium State (#1): The system resides in the global minimum of the free energy landscape. It does not require energy input to maintain its structure, and the final state is independent of the preparation pathway. The structures are dynamic, with monomers continuously exchanging with the solution.

- Kinetically Trapped State (#2): The system is confined in a local minimum with energy barriers much higher than kBT, preventing escape to more stable states over experimental timescales.

- Metastable State (#3): The system resides in a local minimum with moderate energy barriers (on the order of kBT), allowing slow relaxation to more stable states over time.

- Dissipative Non-Equilibrium State (#4): The system requires continuous energy input to maintain its structure. When the energy supply ceases, it relaxes to a thermodynamic or non-dissipative non-equilibrium state.

The following decision tree provides a systematic approach to identifying these states experimentally [17]:

Polymerization Mechanisms

Supramolecular polymerization follows distinct mechanisms that influence the pathway and outcome of the assembly process [14] [13]:

- Isodesmic (Step-Growth) Mechanism: Also known as the equal-K model, this mechanism involves an invariant equilibrium constant for each monomer addition step. The degree of polymerization gradually increases with monomer concentration or decreases with temperature, without a critical concentration or temperature threshold.

- Cooperative (Chain-Growth) Mechanism: This nucleation-elongation mechanism involves an initial unfavorable nucleation step followed by a favored elongation phase. It exhibits a critical concentration or temperature below which polymerization occurs, resulting in a sharp transition.

- Seeded Polymerization: A special case of chain-growth mechanism where pre-formed "seeds" initiate polymerization upon monomer addition, suppressing secondary nucleation and enabling narrow polydispersity and controlled block structures.

Table 1: Comparison of Supramolecular Polymerization Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Isodesmic Mechanism | Cooperative Mechanism | Seeded Polymerization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Constant | Constant for all steps | Different for nucleation vs. elongation | Elongation favored after seeding |

| Critical Concentration | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kinetics | Smooth progression | Sigmoidal with lag time | Controlled by seed addition |

| Polydispersity | Higher | Variable | Lower |

| Analogy | Step-growth polymerization | Chain-growth polymerization | Living polymerization |

Experimental Methodologies and Pathway Selection

Controlling Assembly Pathways

Experimental parameters play a decisive role in steering supramolecular polymerization toward kinetic or thermodynamic pathways. The following diagram illustrates key control parameters and their effects:

Key Experimental Protocols

Pathway Selection in Chiral OPV Systems

The seminal work on an oligo(p-phenylene vinylene) (OPV) derivative by Meijer and co-workers demonstrates how experimental conditions dictate pathway selection [14].

Objective: To control the helical sense (P versus M) of supramolecular polymers from chiral OPV derivative 3. Methodology:

- Prepare molecularly dissolved solution in chloroform at elevated temperature.

- Induce aggregation by either:

- Kinetic pathway: Fast temperature quench to 273 K or stopped-flow rapid injection into poor solvent (methylcyclohexane).

- Thermodynamic pathway: Slow cooling at 1 K min⁻¹ to target temperature. Key Findings: Fast cooling produces a mixture of P-type (kinetic) and M-type (thermodynamic) helices, while slow cooling exclusively yields M-type helices. The kinetic P-helix has a more stable nucleus, while the M-helix is more stable in the elongation regime. Characterization: Stopped-flow CD spectroscopy reveals an initial increase in P-helix formation at high concentrations, which sequesters monomers and increases the lag time for M-helix formation.

Control of Conglomerate versus Racemic Supramolecular Polymers

A recent study on perylene bisimide (PBI) dyes demonstrates pathway-dependent formation of conglomerate versus racemic supramolecular polymers from racemic mixtures [16].

Objective: To control homochiral versus heterochiral aggregation in racemic mixtures of (R,R)- and (S,S)-PBI. Methodology:

- Prepare racemic monomer solutions in methylcyclohexane/toluene (5:4 v/v) at cT = 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ M.

- For kinetic control:

- Cool hot solution rapidly to 298 K to form Con-Agg 1 (nanoparticles).

- Apply ultrasound to transform Con-Agg 1 to Con-Agg 2 (helical nanofibers).

- For thermodynamic control:

- Age the solution or use thermal annealing to form Rac-Agg 4 (racemic nanorods). Key Findings: Homochiral aggregation (conglomerates) occurs under kinetic control, while heterochiral aggregation (racemic compounds) is thermodynamically preferred. Characterization: UV/vis spectroscopy, CD spectroscopy, AFM, and VT-NMR provide structural and mechanistic insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Supramolecular Polymerization Pathways

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PBI Dyes | Model π-conjugated monomers for pathway complexity studies | Amide-functionalized PBIs form various aggregates depending on processing [16] |

| Chiral OPV Derivatives | Investigating helical preferences and pathway complexity | Show distinct kinetic vs thermodynamic helical preferences [14] |

| Ureidopyrimidinone Monomers | Strong quadruple hydrogen-bonding motifs | Form high molecular weight SPs with temperature-dependent viscoelasticity [13] |

| Solvent Mixtures | Tuning solvophobic interactions and aggregation pathways | MCH/toluene, CHCl₃/MCH commonly used to control solubility [14] [16] |

| Seeds/Initiators | Controlling nucleation in seeded polymerization | N-methylated monomer analogs can initiate living SP [13] |

| Chain Cappers | Controlling degree of polymerization | Monofunctional analogs terminate chain growth in isodesmic polymerization [13] |

Characterization Techniques for Pathway Analysis

Spectroscopic Methods

Multiple spectroscopic techniques provide insights into the structural and kinetic aspects of supramolecular polymerization:

- UV/vis Spectroscopy: Monitors electronic coupling between chromophores, distinguishing between different aggregation modes (H- vs J-aggregates) [16]. Time-dependent studies reveal aggregation kinetics and pathway selection.

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Essential for studying chiral aggregation, helical sense preference, and pathway complexity in chiral systems [14] [16]. Can distinguish between enantiomeric aggregates in conglomerates.

- Variable Temperature NMR (VT-NMR): Proves monomer-dimer equilibria and aggregation mechanisms by following chemical shift changes with temperature [16]. Provides information on molecular recognition and binding constants.

Microscopy and Structural Analysis

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Visualizes nanoscale morphology (spherical, fibrous, tubular) and differentiates between polymorphic structures [16]. Height measurements can provide structural information.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Reveals larger-scale structures and morphological features. Cryo-TEM preserves native solution structures [14].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Monitors size evolution and structural transitions over time, useful for studying kinetic trapping and transformation processes [14].

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Analysis

- Temperature-Dependent Studies: Van't Hoff analysis provides thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS) for the aggregation process [14].

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics: Reveals early stages of aggregation and nucleation rates, essential for understanding pathway complexity [14].

- Mathematical Modeling: Fitting experimental data to kinetic models (nucleation-elongation, isodesmic) quantifies thermodynamic and kinetic parameters [14].

Table 3: Key Characterization Techniques for Supramolecular Polymerization Pathways

| Technique | Information Obtained | Application in Pathway Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| UV/vis Spectroscopy | Chromophore coupling, aggregate structure | Distinguishes H- vs J-aggregates; monitors kinetic traces |

| CD Spectroscopy | Chirality, helical sense, absolute configuration | Identifies pathway-dependent helical preferences |

| VT-NMR | Molecular recognition, binding constants | Proves homochiral vs heterochiral aggregation |

| AFM | Nanoscale morphology, dimensions | Differentiates between nanoparticles, fibers, helices |

| TEM | Larger-scale organization, morphology | Visualizes structural transitions over time |

| DLS | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution | Monitors growth kinetics and structural evolution |

| Calorimetry | Thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS) | Determines enthalpy-driven vs entropy-driven assembly |

Implications for Biomedical Applications and Functional Materials

The control over supramolecular polymerization pathways has profound implications for the development of functional materials, particularly in biomedical applications [1]. Kinetic control enables access to metastable structures with tailored properties that may not be accessible under thermodynamic control, while thermodynamic control provides stable, robust materials with self-healing capabilities [17].

In drug delivery, pathway complexity allows for the design of carrier systems with programmed release kinetics [1] [18]. Kinetically trapped nanoparticles can be engineered to disassemble under specific physiological conditions, providing triggered release of therapeutic payloads [18]. The structural control achieved through pathway selection directly impacts drug loading efficiency, release profiles, and biological interactions [1].

Supramolecular hydrogels formed through controlled polymerization pathways exhibit tunable mechanical properties, injectability, and responsiveness to biological cues [1] [19]. These materials serve as scaffolds for tissue engineering, depots for sustained drug release, and matrices for 3D cell culture [1]. The dynamic nature of supramolecular polymers facilitates their clearance from the body without requiring chemical degradation, enhancing their biocompatibility [1].

For drug development professionals, understanding pathway complexity is crucial for ensuring the reproducibility and efficacy of supramolecular formulations [1] [18]. Minor variations in processing conditions—such as mixing rate, temperature profile, or solvent composition—can lead to different polymorphic forms with distinct biological activities and performance characteristics [14] [17]. This is particularly important in the context of regulatory approval, where consistent manufacturing processes are essential.

The study of thermodynamic versus kinetic control in supramolecular polymerization pathways has evolved from a fundamental curiosity to a essential design principle for advanced functional materials [14] [17]. Pathway complexity, once considered a complicating factor, is now recognized as a powerful tool for accessing diverse structures and functions from identical molecular building blocks [14] [15].

Future research directions include the development of predictive models for pathway selection, inspired by computational studies that elucidate the free energy landscapes of supramolecular systems [20]. The emerging field of dissipative self-assembly [17], where continuous energy input maintains systems in non-equilibrium states, offers opportunities for creating adaptive, life-like materials that respond to their environment. For biomedical applications, the integration of pathway control with biological targeting strategies will enable the development of next-generation therapeutic materials with unprecedented precision and efficacy [1] [19].

As the field continues to mature, the deliberate manipulation of thermodynamic and kinetic factors will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated supramolecular polymers with tailored properties for specific applications, from nanomedicine to optoelectronics [14] [1]. The concepts and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a foundation for researchers to harness the full potential of pathway complexity in supramolecular polymer design.

Biomimetic Design Principles Inspired by Natural Biological Systems

The field of supramolecular polymer design is increasingly turning to nature for inspiration, emulating the sophisticated principles that govern biological systems. Biomimetic design involves the conscious emulation of models, systems, and elements from nature to solve complex human challenges, particularly in creating advanced functional materials [21]. This approach has become an influential paradigm in the development of supramolecular architectures that replicate the remarkable properties found in biological structures like spider silk, nacre, and bone—materials that exhibit extraordinary mechanical properties despite being composed of weak individual building blocks [22]. In these natural materials, strength and toughness arise from nanoscale toughening mechanisms where hard and soft domains connect through both covalent bonds and weak interactions, working in synergy to transfer stress through hierarchical design [22].

Supramolecular chemistry provides the ideal foundation for biomimetic approaches because it operates on similar principles as biological systems—relying on non-covalent interactions, self-assembly, and dynamic reversibility rather than permanent covalent bonds [23] [24]. These characteristics enable the creation of materials that can respond, adapt, and reorganize in response to environmental stimuli, much like biological systems do. The integration of biomimetic and supramolecular design principles has opened new frontiers in materials engineering, demonstrating how molecular-level control can lead to functional, sustainable materials that align with ecological needs [23]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications of biomimetic design in supramolecular polymer science, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical experimental protocols.

Fundamental Biomimetic Principles in Supramolecular Systems

Hierarchical Self-Assembly

Biological materials generically exhibit hierarchical structures that enable their exceptional functional properties. They exploit self-assembly across multiple length scales through competing interactions and tailored supramolecular interactions [22]. This principle of hierarchical organization from molecular to macroscopic scales is fundamental to biomimetic design. For instance, natural systems like cellular cytoskeletons and extracellular matrices organize simple building blocks into complex, functional architectures through coordinated non-covalent interactions.

In supramolecular polymer science, this principle translates to designing systems where molecular-scale interactions propagate through multiple levels of organization. Research has demonstrated that asymmetric bile acid-based amphiphilic polymers can create hierarchical materials from nanoscale to bulk upon "switching-on" supramolecular interactions [22]. Similarly, well-defined oligomeric oligosaccharide-based molecules with end-groups capable of supramolecular hydrogen bonds can form columnar liquid crystalline phases and ultimately supramolecular polymers suitable for fiber spinning, directly mimicking natural silk-spinning processes [22].

Sacrificial Bonding and Energy Dissipation

Natural materials like bone and nacre employ sacrificial bonds and hidden lengths to dissipate energy under mechanical stress—a principle that has been successfully translated to synthetic supramolecular systems. These sacrificial bonds break before main structural bonds fracture, dissipating energy while preserving structural integrity, and can often reform after stress relaxation [22].

Experimental approaches have implemented this principle through hierarchical supramolecular cross-linking of polymers, creating biomimetic fracture energy dissipating mechanisms. In one demonstrated system, nanocomposites between multi-walled carbon nanotubes and a polymer exhibited enhanced adhesion through supramolecular interactions, allowing controlled interfacial slipping [22]. The resulting material showed slow crack propagation upon fracturing and improved defect tolerance under mechanical loading, directly mirroring the toughening mechanisms observed in natural materials [22].

Dynamic and Responsive Behavior

Biological systems maintain a delicate balance between stability and adaptability through reversible molecular interactions. This dynamic behavior allows biological structures to reorganize in response to environmental changes while maintaining structural integrity. Supramolecular polymers emulate this principle through non-covalent interactions that can assemble, disassemble, and reassemble based on environmental conditions [23].

A remarkable example of this principle is the development of supramolecular plastics that dissolve in seawater within hours. These materials, created by researchers at RIKEN and the University of Tokyo, are composed of supramolecular polymers held together by reversible salt bridges [23]. These ionic interactions provide exceptional strength under dry conditions but disintegrate when exposed to seawater ions, demonstrating how transient interactions can be programmed for specific environmental responsiveness [23].

Table 1: Key Biomimetic Principles and Their Supramolecular Implementations

| Biomimetic Principle | Natural Example | Supramolecular Implementation | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Self-Assembly | Spider silk, nacre, bone | Bile acid-based amphiphilic polymers; Oligosaccharide-based supramolecular polymers | Hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, hydrophobic interactions |

| Sacrificial Bonding | Bone, mussel threads | Supramolecular cross-linking in polymer-nanotube composites | Host-guest complexes, ionic interactions, metal coordination |

| Dynamic Responsiveness | Cellular cytoskeleton, protein folding | Seawater-degradable supramolecular plastics | Reversible salt bridges, electrostatic interactions |

| Cooperative Assembly | Prion protein assembly | Living supramolecular polymerization of porphyrins | π-π stacking, hydrophobic effects |

| Compartmentalization | Cellular organelles | Micellar nanocontainers from amphiphilic assemblies | Hydrophobic/hydrophilic segregation, electrostatic repulsion |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Biomimetic Self-Assembly Protocols

Protocol 1: Hierarchical Self-Assembly of Supramolecular Structures

This protocol describes the formation of hierarchical structures from molecular building blocks, inspired by natural self-assembly processes.

- Materials: Asymmetric star-shape derivatives of bile acids or similar amphiphilic molecules; appropriate solvent systems (e.g., aqueous buffers, organic/aqueous mixtures); temperature control system.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a 1-5 mM solution of the molecular building blocks in a suitable solvent system.

- Initiate primary assembly by applying a external stimulus such as temperature change, pH adjustment, or solvent evaporation.

- Allow secondary organization to occur through controlled equilibration over 24-48 hours.

- Characterize the resulting structures using microscopy (TEM, AFM) and scattering techniques (SAXS, DLS).

- Key Considerations: The hierarchical organization can be directed by carefully controlling the processing conditions and solvent environment. As demonstrated in research, complex amphiphilic self-assembling systems can create hierarchical materials from nanoscale to bulk upon "switching-on" supramolecular interactions [22].

Protocol 2: Preparation of Biomimetic Nanocomposites with Sacrificial Bonds

This protocol outlines the creation of nanocomposites with energy-dissipating sacrificial bonds, mimicking natural materials like bone and nacre.

- Materials: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes; polymer matrix (e.g., PMMA, PVA); supramolecular cross-linkers (e.g., host-guest molecules, hydrogen-bonding modules).

- Procedure:

- Functionalize carbon nanotubes with supramolecular recognition groups.

- Prepare polymer matrix with complementary supramolecular groups.

- Mix components under controlled shear conditions to ensure uniform dispersion.

- Process the composite through extrusion or compression molding.

- Characterize mechanical properties and fracture behavior.

- Key Considerations: The supramolecular reinforcements and hierarchical structure result in slow crack propagation upon fracturing, reminiscent of natural materials [22].

Characterization Techniques for Biomimetic Supramolecular Systems

Characterizing biomimetic supramolecular systems requires sophisticated techniques to probe multiple length scales and dynamic behaviors:

- Microscopy Techniques: Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) provide visualization of hierarchical structures at nanoscale resolution.

- Scattering Methods: Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) characterize size distributions and structural periodicities.

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Circular dichroism, NMR, and fluorescence spectroscopy reveal molecular-level interactions and conformational changes.

- Mechanical Testing: Dynamic mechanical analysis and tensile testing quantify energy dissipation and sacrificial bonding efficacy.

- Thermal Analysis: Differential scanning calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis probe thermal transitions and stability.

For biomimetic nano-drug delivery systems, characterization must verify complete encapsulation of nanoparticles, determine fundamental characteristics like morphology and particle size, and assess functionality and safety of functional proteins and nanocore drugs [25].

Advanced Biomimetic Systems and Applications

Living Supramolecular Polymerization

Inspired by biological self-replication processes, living supramolecular polymerization represents a significant advancement in biomimetic materials design. This approach mimics the far-from-equilibrium self-organization observed in natural systems, such as prion infection processes [26].

The experimental realization of living supramolecular polymerization involves an 'artificial infection' process where porphyrin-based monomers first assemble into nanoparticles, then convert into nanofibers in the presence of a pre-formed nanofiber 'seed' [26]. This process occurs through a delicate interplay of isodesmic and cooperative aggregation pathways, analogous to conventional chain-growth polymerization but based on non-covalent interactions [26].

The kinetics of this living supramolecular polymerization mirror conventional chain growth polymerization, enabling synthesis of supramolecular polymers with controlled length and narrow polydispersity [26]. This biomimetic approach provides unprecedented control over supramolecular architectures, opening possibilities for designing materials with tailored properties and functionalities.

Biomimetic Nanodelivery Systems

Biomimetic design principles have revolutionized drug delivery through the development of bio-inspired nanodelivery systems. These systems leverage natural transport mechanisms to overcome biological barriers and achieve targeted delivery.

Cell membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles represent a prominent example of this approach. These systems are constructed by encapsulating synthetic nanoparticles within biologically derived membranes, preserving the biological activity of the source cells while maintaining the physicochemical properties of the nanocarrier [25]. This biomimetic platform demonstrates exceptional biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, long circulation time, and inherent tissue targeting capabilities [25].

The preparation of these biomimetic nanodelivery systems involves three primary steps:

- Biomimetic membrane preparation through extraction of cell membranes from various cell types (red blood cells, platelets, cancer cells, etc.)

- Synthesis of drug-loaded nanoplatform cores using organic or inorganic nanomaterials

- Membrane encapsulation through co-incubation, mechanical extrusion, ultrasonication, or microfluidic electroporation [25]

These systems naturally evade immune clearance, penetrate biological barriers, and target specific tissues based on their membrane composition, demonstrating the power of biomimetic design in overcoming longstanding therapeutic challenges [25].

Table 2: Biomimetic Nanodelivery Systems and Their Applications

| System Type | Source of Biomimicry | Key Components | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles | Natural cell membranes | Polymeric nanoparticles; Cell membrane vesicles | Targeted drug delivery, Immunotherapy | Immune evasion, Natural targeting, Biocompatibility |

| Supramolecular nanocontainers | Viral capsids, Protein containers | Amphiphilic cyclodextrins, Calixarenes, Cucurbiturils | Drug solubilization, Enzymatic mimics | Tunable size, Stimuli-responsiveness, Host-guest chemistry |

| Biomimetic hydrogels | Extracellular matrix | Peptide amphiphiles, Supramolecular polymers | Tissue engineering, 3D cell culture | Mimetic mechanical properties, Cell adhesion sites, Biodegradability |

| Artificial ion channels | Cellular ion channels | Pillararenes, Crown ether derivatives | Biosensing, Controlled release | Selective transport, Gating functionality |

| Living supramolecular polymers | Prion propagation, Cytoskeleton | Porphyrin derivatives, π-conjugated molecules | Functional materials, Sensing | Self-replication, Controlled growth, Adaptability |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of biomimetic supramolecular design requires specialized reagents and materials that enable the construction of complex, functional architectures.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomimetic Supramolecular Systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biomimetic Design | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphiphilic Building Blocks | Bile acid derivatives, Peptide amphiphiles, Bolaamphiphiles | Form supramolecular assemblies mimicking lipid membranes | Structural direction, Compartmentalization, Bioactivity |

| Macrocyclic Hosts | Cyclodextrins, Calixarenes, Cucurbiturils, Pillararenes | Create molecular recognition sites and nanocavities | Host-guest chemistry, Molecular encapsulation, Catalytic sites |

| Metallosurfactants | Metal-ion containing amphiphiles | Introduce catalytic, magnetic, or optical functionalities | Redox activity, Coordination geometry, Stimuli-responsiveness |

| Stimuli-Responsive Monomers | Azobenzene derivatives, Spiropyran compounds, pH-sensitive groups | Enable dynamic, adaptive material behavior | Photo-, chemo-, or thermo-responsiveness, Reversible switching |

| Biopolymer Templates | DNA origami, Silk fibroin, Collagen mimetic peptides | Provide structural scaffolding for biomimetic organization | Precise nanostructuring, Biocompatibility, Hierarchical ordering |

| Supramolecular Cross-linkers | Guest-host pairs (e.g., adamantane-cyclodextrin), Hydrogen bonding motifs | Introduce reversible connectivity and sacrificial bonds | Dynamic bond formation, Energy dissipation, Self-healing capability |

Visualization of Biomimetic Design Workflows

Biomimetic Nanocarrier Preparation Workflow

Diagram Title: Biomimetic Nanocarrier Preparation Workflow

Hierarchical Self-Assembly Process

Diagram Title: Hierarchical Self-Assembly Process

Biomimetic design principles have fundamentally transformed supramolecular polymer science, providing powerful strategies for creating functional materials with life-like properties. By emulating nature's approaches to hierarchical organization, energy dissipation, dynamic responsiveness, and molecular recognition, researchers have developed supramolecular systems with unprecedented capabilities—from seawater-degradable plastics that address environmental challenges [23] to intelligent drug delivery systems that navigate biological barriers [25].

The future of biomimetic supramolecular design lies in advancing our understanding of dynamic, out-of-equilibrium systems that more closely mimic living processes. The emerging paradigm of living supramolecular polymerization [26] points toward materials that can grow, adapt, and self-repair with spatiotemporal control. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and predictive modeling will accelerate the design of bespoke biomimetic systems, while green chemistry approaches will ensure their sustainability and biocompatibility.

As these biomimetic strategies continue to evolve, they will enable increasingly sophisticated materials that blur the boundary between biological and synthetic systems, ultimately leading to more sustainable, adaptive, and intelligent material solutions for challenges spanning medicine, energy, and environmental science.

Engineering Functionality: Design Strategies for Advanced Therapeutic Applications

Stimuli-Responsive Architectures for Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

Stimuli-responsive architectures represent a paradigm shift in supramolecular polymer design for therapeutic applications. These advanced materials, often termed "smart" or "intelligent" polymers, are engineered to undergo precise, controlled alterations in their physicochemical properties in response to specific internal or external triggers [27] [28]. This capability enables the spatial and temporal control of drug release at targeted sites within the body, significantly enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [29]. The foundational principle of these architectures lies in their dynamic molecular design, which allows for predictable structural transformations under defined physiological or external conditions. Within the context of supramolecular polymer design, the integration of responsive elements facilitates the creation of sophisticated drug delivery systems (DDS) that mimic biological feedback mechanisms. These systems respond to pathological abnormalities—such as acidic pH, elevated enzyme concentrations, or redox potential gradients—transforming from inert carriers to active drug release platforms precisely where needed [30]. The evolution of these architectures marks a critical advancement in nanomedicine, moving beyond conventional diffusion-controlled release toward biologically informed, triggered drug delivery.

Classification of Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms

Stimuli-responsive architectures are categorized based on their triggering mechanisms, which originate either from the body's internal pathological microenvironment (internal stimuli) or from externally applied sources (external stimuli). The design of supramolecular polymers must account for the specific trigger availability, response kinetics, and biocompatibility for each application.

Internal Stimuli

Internal stimuli are biological markers or conditions unique to pathological sites. Smart architectures exploit these distinctions to achieve targeted drug release.

pH-Responsive Systems: Tumors, inflamed tissues, and intracellular compartments like endosomes and lysosomes exhibit decreased pH (acidic) compared to normal tissues and blood (pH 7.4) [29]. These systems incorporate functional groups that accept or donate protons in response to pH changes. Common designs use polymers with ionizable moieties (e.g., carboxylic acids in poly(acrylic acid) or tertiary amines in chitosan derivatives) that undergo structural changes—such as swelling, dissociation, or charge reversal—in acidic environments [27] [30]. This enables the selective release of chemotherapeutic agents within the tumor microenvironment or infected tissues.

Enzyme-Responsive Systems: Overexpression of specific enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases, phosphatases, esterases) at disease sites provides a highly specific trigger. These systems incorporate enzyme-specific cleavage sites into the polymer backbone or as linkers between the carrier and drug [29]. Upon enzymatic cleavage, the supramolecular structure degrades or undergoes a conformational change, releasing the encapsulated therapeutic agent. This approach offers high specificity due to the unique substrate requirements of different enzymes.

Redox-Responsive Systems: The significant difference in redox potential between the intracellular and extracellular compartments, primarily due to elevated glutathione (GSH) concentrations inside cells (particularly in tumor tissues), serves as a potent trigger [30]. These architectures typically contain disulfide bonds that remain stable in the extracellular environment but undergo rapid cleavage upon exposure to the reducing intracellular milieu, facilitating controlled drug release inside target cells.

External Stimuli

Externally applied stimuli provide spatiotemporal precision for drug release, allowing clinicians to control therapy with high accuracy.

Temperature-Responsive Systems: These utilize polymers with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST), such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm), which undergo a reversible phase transition from hydrophilic to hydrophobic upon heating above their LCST [28] [31]. This transition can be triggered by mild external heating of the target tissue or by the inherent fever associated with inflammation, causing polymer collapse and drug release.

Light-Responsive Systems: Functional dyes like azobenzenes, spiropyrans (SPs), and diarylethenes are chemically incorporated into polymer structures [31]. Upon irradiation with light of specific wavelengths, these chromophores undergo reversible isomerization (e.g., SPs switching to planar, highly polar merocyanines (MCs) under UV light), changing the polymer's polarity, volume, or conformation to trigger drug release. Light offers excellent spatiotemporal control but is limited by tissue penetration depth.

Magnetic and Ultrasound-Responsive Systems: These systems incorporate components (e.g., iron oxide nanoparticles, perfluoropentane) that respond to non-invasive external energy sources [29]. Under an alternating magnetic field or ultrasound irradiation, these materials generate heat, induce cavitation, or disrupt their structure, leading to controlled drug release. Ultrasound is particularly effective for penetrating deep tissues.

Table 1: Key Stimuli, Responsive Mechanisms, and Common Polymer Examples

| Stimulus Type | Specific Stimulus | Responsive Mechanism | Exemplary Polymers / Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | Acidic pH | Protonation/deprotonation; Charge reversal; Bond cleavage | Chitosan, Poly(acrylic acid), Dimethylmaleic anhydride (DA) [29] [30] |

| Enzymes (e.g., MMPs) | Cleavage of peptide linkers | Peptide-crosslinked polymers [29] | |

| Redox (High GSH) | Disulfide bond cleavage | Disulfide-crosslinked polymers, Thioketal-based polymers [30] | |

| External | Temperature (Heat) | LCST transition; Phase separation | PNIPAAm, Poly(oligo ethylene glycol) acrylates [28] [31] |

| Light (UV/Vis) | Photoisomerization; Polarity change | Azobenzenes, Spiropyrans [31] | |

| Ultrasound | Cavitation; Thermal effect | Perfluoropentane-loaded liposomes [29] | |

| Magnetic Field | Hyperthermia; Mechanical force | Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Stimuli-Responsive Systems

Synthesis and Evaluation of pH-Responsive Nanoparticles

Objective: To prepare and characterize dimethylmaleic anhydride (DA)-modified nanoparticles for pH-triggered antibiotic delivery against lung infections [29].

Materials:

- Azithromycin (AZI): Broad-spectrum macrolide antibiotic as active therapeutic.

- ε-Poly(L-lysine): Cationic biopolymer forming the nanoparticle core.

- Dimethylmaleic anhydride (DA): pH-responsive moiety that converts to a hydrophilic, charged form in acidic environments.

- Carbodiimide Crosslinker (e.g., EDC): Activates carboxylic acids for amide bond formation.

Methodology:

- Polymer Conjugation: React ε-poly(L-lysine) with DA in an anhydrous organic solvent (e.g., DMSO) under inert atmosphere. The primary amines of polylysine form amide bonds with the anhydride, introducing DA groups.

- Drug Loading: Add AZI to the DA-polylysine conjugate in aqueous buffer (pH 7.4) under stirring. Nanoparticles form via self-assembly, encapsulating AZI. Remove unencapsulated drug by dialysis or centrifugation.

- Characterization:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measure hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential at pH 7.4 and pH 6.5. A significant size decrease and zeta potential shift from negative/neutral to positive confirms charge reversal.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualize nanoparticle morphology and size before and after pH change.

- Drug Release Kinetics: Use dialysis bags submerged in buffers at pH 7.4 and pH 6.5. Sample the release medium at predetermined intervals and quantify AZI concentration via HPLC-UV to establish pH-dependent release profile.

Expected Outcome: DA-AZI nanoparticles exhibit minimal drug release at physiological pH (7.4) but rapidly disassemble and release AZI in acidic microenvironments (e.g., infection sites, pH ~6.5), enhancing biofilm penetration and antibacterial efficacy [29].

Fabrication and Testing of Light-Responsive Adhesives for Device Placement

Objective: To develop a polymer film with spiropyran (SP) side chains for light-switchable adhesion, potentially useful for securing and retrieving implantable drug delivery devices [31].

Materials:

- SP-containing Monomer (e.g., SPMA): Methacrylate monomer with spiropyran pendants.

- Photoinitiator (e.g., Irgacure 784): Cleaves upon UV light exposure to initiate polymerization.

- Inert Substrate (e.g., glass slide): Support for polymer film.

Methodology:

- Polymer Synthesis: Conduct free radical polymerization of SPMA in an appropriate solvent. Purify the resulting polymer (PSPA) via precipitation.

- Film Fabrication: Dissolve PSPA and a photoinitiator in volatile solvent. Spin-coat the solution onto a clean glass substrate. Evaporate the solvent under vacuum to form a uniform thin film.

- Adhesion Testing:

- Lap Shear Test: Sandwich the PSPA film between two glass slides to form a lap joint.

- Light Irradiation: Expose the joint to UV light (365 nm) to isomerize SP to merocyanine (MC), increasing polarity and adhesion strength. Measure the force required to shear the joint.

- Reversal: Expose the joint to visible light (525 nm) to revert MC to SP, decreasing polarity and adhesion strength. Measure the shear force again.

- Characterization:

- UV/Vis Spectroscopy: Monitor the appearance (λmax ~580 nm) and disappearance of the MC absorption band to quantify isomerization.

- Contact Angle Goniometry: Measure water contact angles on the film after UV and Vis irradiation to confirm polarity changes.

Expected Outcome: The PSPA film demonstrates reversible, light-switchable adhesion, with adhesion strength increasing under UV light due to polar MC formation and decreasing under visible light. This allows for on-demand bonding and debonding [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and characterization of stimuli-responsive architectures require a specialized set of reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery System Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| pH-Responsive Monomer | Confers sensitivity to acidic environments; enables charge reversal and structural change. | Dimethylmaleic anhydride (DA): Modifies surface charge. Neutral at pH 7.4, it converts to a negatively charged carboxylate in mildly acidic conditions (pH ~6.5), promoting nanoparticle dissociation and mucus penetration [29]. |

| Thermoresponsive Polymer | Undergoes a reversible phase transition (e.g., sol-gel) upon temperature change. | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm): Has an LCST of ~32°C. It is hydrated and expanded below the LCST but collapses and becomes hydrophobic above it, facilitating drug release in heated tissues [28] [31]. |

| Photoswitchable Dye | Acts as a molecular actuator within the polymer, changing properties upon light exposure. | Spiropyran (SP): Incorporated into polymer side chains. UV light (365 nm) switches it to a polar Merocyanine (MC) form, increasing adhesion; visible light (525 nm) switches it back [31]. |

| Crosslinking Agent | Forms covalent bonds between polymer chains, stabilizing the 3D network of a hydrogel or nanoparticle. | Carbodiimide (e.g., EDC): Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amines, used for conjugating DA to polylysine or creating enzyme-degradable peptide crosslinks [29]. |

| Biocompatible Polymer | Serves as the structural backbone of the nanocarrier; often biodegradable. | ε-Poly(L-lysine): A natural, cationic biopolymer that can be chemically modified with responsive groups and self-assembles or crosslinks to form nanoparticles [29]. |

| External Energy Absorber | Converts external energy (US, magnetic field) into heat or mechanical force for triggered release. | Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles: When incorporated into a matrix, they generate heat under an alternating magnetic field or enhance ultrasound-mediated drug release from catalytic microbubbles (MB-Pip) [29]. |

Multi-Stimuli Responsive Systems and Advanced Applications

The forefront of supramolecular polymer design involves multi-stimuli-responsive systems that integrate multiple trigger mechanisms, enhancing specificity and control for complex therapeutic scenarios. These architectures respond to a combination of internal and external stimuli, often in a sequential or cascade manner, mirroring the multifaceted nature of disease microenvironments [29] [30].

A prime example is a nanoparticle system designed for lung infection treatment, which combines ultrasound (external) and enzymatic (internal) triggers. The system consists of chlorin e6 (Ce6) and metronidazole (MNZ) incorporated into liposomes encapsulating perfluoropentane (PFP), forming PLCM NPs [29]. When subjected to ultrasound, the PLCM NPs undergo cavitation, promoting the release of Ce6 and MNZ. The simultaneous application of ultrasound and the released Ce6 (a photosensitizer) induces pore formation in the bacterial membrane, significantly enhancing the penetration and efficacy of the antibiotic MNZ. This synergistic approach demonstrates how multi-stimuli-responsive systems can overcome biological barriers like biofilms.

Furthermore, advanced material platforms like multi-stimuli-responsive liquid crystalline polymer films exemplify the complexity achievable through supramolecular design. These systems can be engineered to respond independently to temperature, humidity, light, and pH, allowing for the programming and reconfiguration of structural and fluorescent information [32]. While demonstrated for anti-counterfeiting, this principle of orthogonal stimulus control has profound implications for drug delivery, enabling the design of systems that can perform complex logic-based release operations in response to a specific sequence of pathological signals.