The Future of Regeneration: A 2024 Guide to 3D Printed Biopolymer Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and methodologies in 3D printing for fabricating biopolymer scaffolds for tissue engineering.

The Future of Regeneration: A 2024 Guide to 3D Printed Biopolymer Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and methodologies in 3D printing for fabricating biopolymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Targeted at researchers and biomedical professionals, it explores the foundational principles of scaffold design and biomaterial selection, details cutting-edge fabrication techniques like extrusion-based and light-based printing, and addresses critical challenges in resolution, mechanical properties, and biofunctionalization. It further examines rigorous validation protocols, including in vitro and in vivo assessments, and compares leading biopolymers like alginate, gelatin, PCL, and novel composites. The synthesis offers a roadmap for translating lab innovation into clinically viable tissue constructs.

Building the Blueprint: Core Principles and Material Selection for 3D Bioprinted Scaffolds

Application Notes

The convergence of 3D printing (additive manufacturing) and biopolymer science has created a paradigm shift in tissue engineering (TE). The central challenge is the rational design of scaffolds that precisely replicate the native tissue's extracellular matrix (ECM). This requires a holistic optimization of three interdependent pillars: Porosity, Mechanics, and Bioactivity. Failure to balance this triad leads to poor cell infiltration, mechanical failure, or insufficient biological integration. The following application notes contextualize this triad within a 3D bioprinting framework.

Porosity & Architecture

Porosity is not merely a percentage; it is a multi-faceted architectural feature defining a scaffold's capacity to support tissue ingrowth and vascularization.

- Total Porosity (70-90%): Essential for high cell loading and nutrient/waste diffusion. Below 60%, diffusion limitations become critical; above 95%, mechanical integrity is often compromised.

- Pore Size & Interconnectivity: Pore size dictates specific tissue responses. Bone regeneration typically requires >300 µm pores for vascularization, while neocartilage formation may utilize 150-250 µm pores. 100% interconnectivity is a non-negotiable target to prevent cell entrapment and necrotic cores.

- 3D Printing Control: Extrusion-based printing allows direct programming of strand distance (spacing) and layer height to dictate pore geometry. Melt Electrowriting (MEW) can produce ultrafine fibers to create microporosity within larger printed macro-pores.

Table 1: Target Porosity and Pore Size for Key Tissues

| Target Tissue | Optimal Total Porosity (%) | Optimal Pore Size Range (µm) | Critical Architectural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancellous Bone | 70-90% | 300-600 µm | High interconnectivity, tortuous paths. |

| Articular Cartilage | 60-80% | 150-250 µm | Layered structure, graded porosity. |

| Skin (Dermal Layer) | 80-95% | 200-400 µm | Highly interconnected, thin fibrous walls. |

| Nerve Guidance | 70-85% | 50-150 µm (micro), >500 µm (macro) | Aligned, directional channels. |

| Vascular Networks | >90% | 500-1000 µm (channels) | Prefabricated, perfusable lumens. |

Mechanical Properties

Scaffold mechanics must match the native tissue's modulus and strength to provide structural support and transmit appropriate mechanobiological cues.

- Young's Modulus: The stiffness of the scaffold. Mismatch (e.g., a too-stiff scaffold in soft tissue) can cause stress shielding and hinder regeneration.

- Degradation Rate: Must be coupled with the rate of new tissue formation. Fast-degrading polymers (e.g., PLGA) may lose integrity before tissue matures, while slow-degrading ones (e.g., PCL) may cause chronic inflammation.

- Viscoelasticity: Native tissues (especially cartilage, skin) are viscoelastic. Advanced biopolymer blends and hydrogel designs are incorporating this property.

Table 2: Target Mechanical Properties for Key Tissues

| Target Tissue | Approximate Young's Modulus (MPa) | Desired Degradation Time | Key Mechanical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancellous Bone | 50-500 MPa | 6-18 months | High compressive strength (>2 MPa). |

| Articular Cartilage | 0.5-1.5 MPa | 3-12 months | High compressive & shear strength, lubricity. |

| Skin (Dermis) | 0.1-0.8 MPa | 2-8 weeks | Flexibility, tensile strength. |

| Cardiac Muscle | 0.01-0.5 MPa | 1-6 months | Elasticity, cyclic fatigue resistance. |

| Brain Tissue | 0.001-0.01 MPa | 2-12 weeks | Ultra-soft, viscoelastic. |

Bioactivity

Bioactivity bridges the synthetic scaffold and biological environment, guiding cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and ECM production.

- Surface Chemistry: Intrinsic bioactivity of polymers (e.g., collagen, gelatin) vs. modified polymers (e.g., RGD-peptide grafted PCL).

- Controlled Release: Scaffolds as delivery vehicles for growth factors (e.g., BMP-2, VEGF) or drugs (antibiotics, anti-inflammatories) via encapsulation or surface tethering.

- Dynamic Signaling: Incorporation of enzyme-cleavable or stimuli-responsive peptides to mimic the dynamic nature of the ECM.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Design & 3D Printing of a Graded Porosity Scaffold

Objective: To fabricate a cylindrical PLA scaffold with radially graded porosity for bone-cartilage interface engineering. Materials: Medical-grade PLA filament, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printer, slicing software (e.g., Ultimaker Cura), isopropanol. Procedure:

- Design: Create a cylindrical model (Ø10mm x 5mm) in CAD software.

- Grading Strategy: In the slicing software, divide the model into three radial zones:

- Zone 1 (Center, Ø0-3mm): Set infill density to 80%, rectilinear pattern.

- Zone 2 (Middle, Ø3-7mm): Set infill density to 70%, gyroid pattern.

- Zone 3 (Outer, Ø7-10mm): Set infill density to 60%, gyroid pattern.

- Maintain a constant layer height (0.15mm) and nozzle temperature (210°C).

- Print: Execute the print on a clean build plate.

- Post-Processing: Carefully remove support structures (if any). Clean the scaffold via sonication in isopropanol for 5 minutes and air dry under a laminar flow hood.

- Sterilization: Sterilize via immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes, followed by UV exposure on each side for 15 minutes.

Protocol 2: Mechanical Compression Testing of a Hydrated Scaffold

Objective: To determine the compressive modulus of a 3D-printed hydrogel scaffold under physiologically relevant (hydrated) conditions. Materials: Printed hydrogel scaffold (e.g., gelatin methacryloyl), universal mechanical tester equipped with a 50N load cell, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), calipers. Procedure:

- Hydration: Soak the scaffold in PBS at 37°C for 24 hours to reach equilibrium swelling.

- Measurement: Gently blot the scaffold dry and measure its diameter and height using calipers.

- Setup: Place the scaffold centrally on the lower plate of the mechanical tester. Submerge the setup in a PBS bath at 37°C.

- Pre-load: Apply a small pre-load (0.01N) to ensure full contact.

- Test: Perform uniaxial compression at a constant strain rate of 1% per second until 60% strain is reached.

- Analysis: From the resulting stress-strain curve, calculate the compressive modulus as the slope of the initial linear elastic region (typically 5-15% strain). Report the average of n=5 samples.

Protocol 3: Assessment of Bioactivity via Cell Seeding and Differentiation

Objective: To evaluate the osteogenic bioactivity of a BMP-2 functionalized scaffold using human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Materials: PCL/BMP-2 scaffold, control PCL scaffold, hMSCs, osteogenic medium (OM: DMEM, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone), basal growth medium (GM), Alizarin Red S stain, cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Procedure:

- Seeding: Sterilize scaffolds (70% EtOH, UV). Pre-wet with medium. Seed hMSCs at a density of 50,000 cells/scaffold using the droplet method. Incubate for 2 hours, then add medium.

- Culture: Maintain half of the scaffolds from each group in OM and the other half in GM. Change medium every 3 days.

- Analysis (Day 21):

- Alizarin Red Staining: Fix scaffolds in 4% PFA, wash, incubate with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2) for 20 mins. Wash extensively. Image for mineralized nodule formation.

- Quantification: Elute stain with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride, measure absorbance at 562 nm.

- Expected Outcome: Significant increase in mineralization (absorbance) only in the BMP-2 functionalized scaffolds cultured in OM, confirming synergistic scaffold bioactivity and biochemical cues.

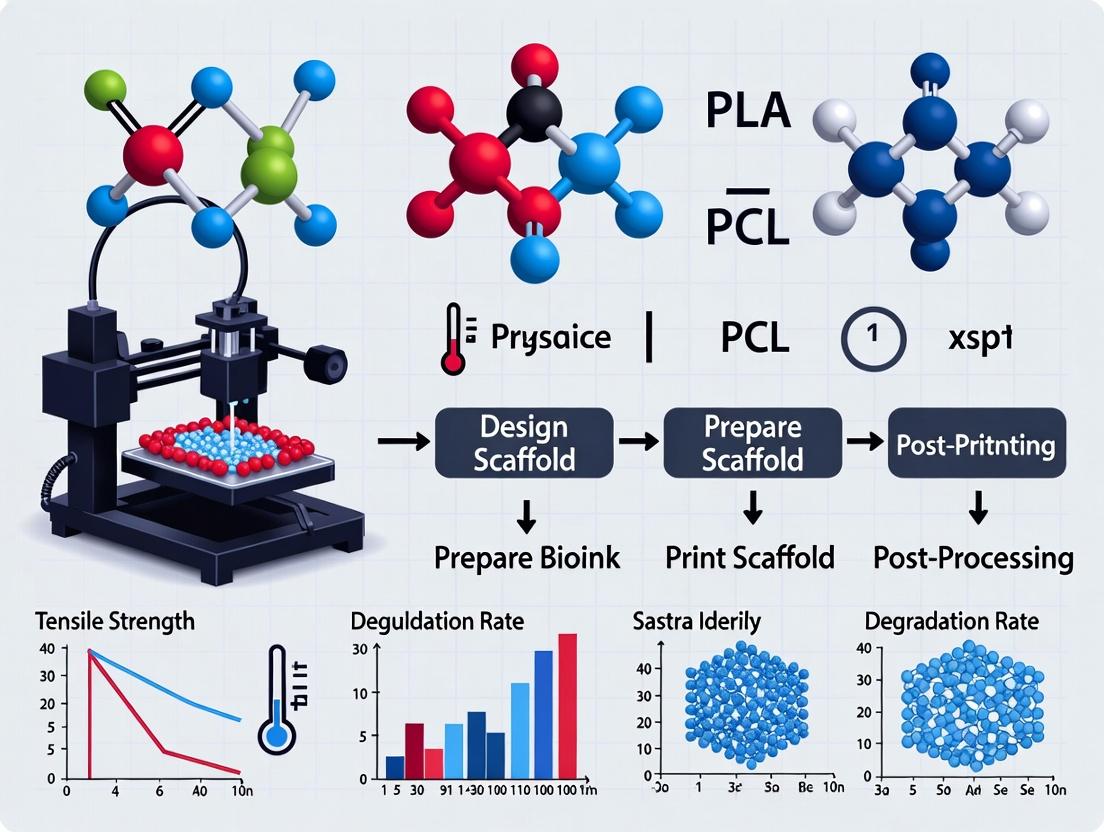

Visualizations

Triad of Scaffold Design for Tissue Regeneration

BMP-2 Induced Osteogenic Signaling Pathway

Scaffold Fabrication and Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Biopolymer Scaffold R&D

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-Grade Biopolymers | Raw material for scaffold fabrication. Defines base degradability & mechanics. | PCL (Polycaprolactone): Slow-degrading, thermoplastic for FDM. GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl): Photocrosslinkable, bioactive hydrogel resin. PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)): Tunable degradation rate. |

| Bioactive Peptides | Conjugated to polymers to impart specific cell-signaling functions. | RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp): Promotes integrin-mediated cell adhesion. IKVAV: Promotes neural cell adhesion and neurite outgrowth. |

| Growth Factors | Incorporated to guide stem cell differentiation and tissue formation. | rhBMP-2 (Recombinant Human): Potent osteoinductive factor. VEGF: Induces angiogenesis within scaffolds. Use carrier proteins (e.g., BSA) for stable encapsulation. |

| Photocrosslinkers | Initiate polymerization of light-sensitive bioinks (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA). | LAP (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate): Biocompatible, visible-light (405 nm) photoinitiator. Irgacure 2959: UV (365 nm) photoinitiator. |

| Live/Dead Viability Assay | Standard kit for quantifying cell viability and distribution within 3D scaffolds. | Calcein AM (live/green) & Ethidium homodimer-1 (dead/red). Critical for assessing printing biocompatibility and seeding efficiency. |

| AlamarBlue / MTT Assay | Colorimetric or fluorescent assays to measure metabolic activity, indicating cell proliferation within scaffolds over time. | Requires establishing a standard curve. Data normalized to scaffold volume/mass. |

| PCR Primers & RNA Kits | To analyze cell differentiation by measuring tissue-specific gene expression (e.g., RUNX2, COL2A1, TNNT2). | RNA extraction from cells on 3D scaffolds is challenging; use kits optimized for fibrous/cartilaginous tissues. |

| Micro-CT Contrast Agent | Stains soft biopolymer scaffolds for high-resolution 3D architectural analysis. | Phosphotungstic acid (PTA) or Iodine. Allows quantification of porosity, pore size, and interconnectivity. |

| Enzymatic Degradation Buffer | Simulates hydrolytic or enzymatic degradation of scaffolds for in vitro degradation studies. | PBS (pH 7.4): For hydrolytic degradation. Collagenase or Lysozyme solutions: For enzyme-mediated degradation. |

This document, framed within a thesis on 3D printing for tissue engineering, provides application notes and detailed protocols for key biopolymers. The strategic selection of materials—natural, synthetic, or hybrid—dictates the scaffold's printability, mechanical integrity, bioactivity, and degradation profile, ultimately guiding cellular fate and tissue regeneration.

| Biopolymer Category | Material | Key Properties (2024 Perspective) | Prime Tissue Engineering Applications | Optimal 3D Printing Method (2024) | Typical Crosslinking Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Alginate | Rapid ionic gelation; low cell adhesion; high biocompatibility. | Cartilage, wound dressings, drug delivery capsules. | Extrusion (ionic crosslinking bath). | Ionic (Ca²⁺, Ba²⁺). |

| Natural | Gelatin/GelMA | RGD sequences for cell adhesion; thermoresponsive. | Bone, vascular, skin regeneration. | Extrusion (cooled plate), DLP. | Photo (UV/LAP). |

| Natural | Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | CD44 receptor targeting; high hydration; regulates inflammation. | Neural, cartilage, dermal regeneration. | Extrusion, DLP. | Photo (e.g., methacrylation). |

| Synthetic | Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | High mechanical strength; slow degradation (>2 years); hydrophobic. | Load-bearing bone, cranial implants. | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), melt extrusion. | Thermal fusion. |

| Synthetic | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Tunable degradation (weeks–months); FDA-approved. | Bone, controlled drug delivery scaffolds. | Extrusion (solvent-based). | Solvent evaporation. |

| Hybrid | Alginate-Gelatin | Combines alginate's structure with gelatin's bioactivity. | Modular tissue constructs, bioprinting. | Co-extrusion, composite bioink. | Dual: Ionic + Thermal/Photo. |

| Hybrid | PCL-GelMA | PCL provides mechanical framework; GelMA enables cell encapsulation. | Osteochondral, vascular grafts. | Sequential printing: FDM PCL + extrusion GelMA. | Thermal + Photo. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: 3D Bioprinting of a GelMA-HA Composite Hydrogel for Chondrogenesis

Objective: To fabricate a cell-laden, photocrosslinkable hydrogel scaffold supporting mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) chondrogenic differentiation.

The Scientist's Toolkit:

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| GelMA (Methacrylated Gelatin) | Provides photocrosslinkable, bioactive backbone with RGD sites. |

| HA-MA (Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid) | Enhances water retention, provides CD44 binding sites for MSCs. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Cytocompatible photoinitiator for visible/UV light crosslinking. |

| Human Bone Marrow MSCs | Primary cells with chondrogenic potential. |

| Chondrogenic Medium | Contains TGF-β3, ascorbate, dexamethasone to drive differentiation. |

| Sterile PBS (pH 7.4) | For dilution and washing. |

| Bioprinter (Extrusion-based) | For precise deposition of bioink. |

| 405 nm LED Crosslinking System | For rapid, controlled photopolymerization post-printing. |

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation:

- Dissolve LAP in PBS at 0.25% (w/v) to create stock solution. Sterile filter (0.22 µm).

- Prepare 7% (w/v) GelMA and 1% (w/v) HA-MA in the LAP/PBS solution. Gently mix at 37°C until fully dissolved. Avoid bubbles.

- Centrifuge the bioink at 300 x g for 5 minutes to remove bubbles.

- Keep bioink at 37°C until printing.

Cell Preparation and Encapsulation:

- Trypsinize, count, and pellet MSCs. Resuspend pellet in a small volume of bioink to achieve a final density of 5-10 x 10⁶ cells/mL.

- Gently mix the cell-bioink suspension. Keep on ice or at 15°C to prevent premature gelation.

3D Printing Process:

- Load bioink into a sterile, temperature-controlled (18-22°C) syringe fitted with a conical nozzle (22-27G).

- Set printing parameters: Pressure 15-25 kPa, speed 5-10 mm/s, layer height 80% of nozzle diameter.

- Print scaffold (e.g., 10x10x2 mm grid) onto a substrate.

- Immediately after each layer, expose to 405 nm light (5-10 mW/cm² for 15-30 seconds) for partial crosslinking.

Post-Printing and Culture:

- After final layer, perform a final crosslinking (60 seconds) for full structural integrity.

- Transfer scaffold to cell culture plate, wash with PBS, and immerse in chondrogenic medium.

- Culture for up to 28 days, changing medium every 2-3 days. Assess viability (Live/Dead), glycosaminoglycan content (DMMB assay), and collagen II expression (immunohistochemistry).

GelMA-HA Bioprinting Workflow

Protocol: Fabrication of a Dual-Scaffold PCL-PLGA Hybrid for Controlled Drug Release

Objective: To create a mechanically robust, drug-eluting scaffold via sequential 3D printing of PCL and PLGA layers.

Procedure:

- PCL Framework Printing (FDM):

- Load PCL filament into FDM printer. Set nozzle temperature to 85-95°C, bed to 45°C.

- Print a porous macro-scaffold (e.g., 0/90° laydown pattern, 300 µm strand, 500 µm pore) at 5-10 mm/s.

Drug-Loaded PLGA Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve PLGA (50:50 LA:GA) in DMSO or ethyl acetate at 20% (w/v).

- Add model drug (e.g., Dexamethasone or BMP-2) at 1-5% (w/w polymer). Sonicate to mix.

PLGA Coating/Drug Integration:

- Option A (Coating): Dip the printed PCL scaffold into the PLGA-drug solution. Withdraw slowly.

- Option B (Precision Deposition): Use a secondary extrusion system to print PLGA-drug solution directly into PCL pores.

- Dry scaffold in vacuum desiccator for 48 hours to remove all solvent.

Characterization & Release Study:

- Analyze morphology via SEM.

- Perform in vitro drug release in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C under gentle agitation. Sample supernatant at predetermined times and analyze via HPLC/UV-Vis. Replace with fresh PBS.

PCL-PLGA Hybrid Fabrication Process

Signaling Pathways in Scaffold-Mediated Tissue Regeneration

Scaffold-Cue Activated Signaling Pathways

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing of biopolymer scaffolds for tissue engineering, the precise formulation and characterization of bioinks is paramount. A bioink is not merely a cell-laden hydrogel; it is a sophisticated material system whose rheological behavior, crosslinking kinetics, and post-printing stability dictate the structural and biological fidelity of the final construct. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for assessing these fundamental properties, enabling researchers to develop bioinks that meet the stringent criteria for printability and biological function.

Rheological Characterization of Bioinks

Rheology governs extrusion, shape fidelity, and cell viability during bioprinting. Key parameters include viscosity, shear-thinning behavior, yield stress, and viscoelastic moduli (G' and G'').

Table 1: Target Rheological Properties for Extrusion-Based Bioprinting

| Parameter | Ideal Range/Value | Rationale | Common Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-shear viscosity | > 10 Pa·s | Prevents nozzle dripping and maintains pre-print structure. | Steady-shear flow ramp (0.01 - 1 s⁻¹). |

| Shear-thinning index (n) | n < 1 (Power-law model) | Viscosity decreases under shear for smooth extrusion, recovers after deposition. | Power-law fit to flow curve. |

| Apparent viscosity at printing shear rate | 10 - 100 Pa·s | Balances extrusion force and cell viability. | Measured at shear rate relevant to nozzle (e.g., 10 - 100 s⁻¹). |

| Yield stress (τ₀) | 50 - 500 Pa | Provides shape retention post-deposition. | Herschel-Bulkley model fit or amplitude sweep. |

| Storage Modulus (G') post-crosslinking | > 500 Pa | Ensures mechanical integrity of the final scaffold. | Oscillatory time sweep post-gelation. |

| Loss factor (tan δ = G''/G') | < 0.5 (post-gelation) | Indicates solid-like, elastic dominant behavior. | Oscillatory frequency sweep. |

Protocol 2.1: Comprehensive Rheological Assessment

Objective: To measure the flow behavior, viscoelasticity, and gelation kinetics of a candidate bioink.

Materials:

- Rheometer (cone-plate or parallel plate geometry, Peltier temperature control).

- Bioink sample (≥ 500 µL).

- Crosslinking agent (if applicable).

- Solvent trap or humid chamber to prevent drying.

Procedure:

- Loading: Pre-cool the plate to 4°C. Load the bioink onto the center of the lower plate. Bring the measuring geometry (e.g., 25 mm cone, 0.5° angle) to the prescribed gap (e.g., 0.1 mm). Trim excess material.

- Amplitude Sweep: At a constant frequency (1 Hz), perform an oscillatory strain sweep from 0.1% to 100% strain. Determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) where G' and G'' are strain-independent.

- Flow Curve: Perform a steady shear rate sweep from 0.01 s⁻¹ to 100 s⁻¹, then back down. Record viscosity. Fit data to Herschel-Bulkley model: τ = τ₀ + K * (γ̇)^n.

- Gelation Kinetics: Initiate a time sweep at 1 Hz and a strain within the LVR (e.g., 1%). Immediately after starting measurement, introduce the crosslinking trigger (e.g., mix in UV initiator, change temperature to 37°C, add ionic crosslinker via pipette at edge of geometry). Monitor G' and G'' until plateau.

- Frequency Sweep: After gelation, perform a frequency sweep from 0.1 to 100 Hz at constant LVR strain.

Crosslinking Mechanisms

Crosslinking transforms a viscous bioink into a stable hydrogel. Mechanisms can be physical (reversible) or chemical (permanent).

Table 2: Common Bioink Crosslinking Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Trigger | Example Polymers | Key Advantages | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic | Divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) | Alginate, Gellan Gum | Fast, mild, cytocompatible. | Can be slow to diffuse; chelation can cause instability. |

| Thermal | Temperature shift (↑ or ↓) | Gelatin, Matrigel, Pluronic F127, Agarose | Physiologic for some (collagen). | Low mechanical strength; potential cell settling during gelation. |

| Photo- chemical | UV/Visible Light (λ = 365-405 nm) | GelMA, PEGDA, Hyaluronic Acid Methacrylate | Spatiotemporal control, good mechanics. | Photoinitiator cytotoxicity; UV damage to cells. |

| Enzymatic | Enzyme + Co-factor | Fibrin (Thrombin+Fibrinogen), Tyramine-substituted polymers (HRP+H₂O₂) | High specificity, physiologic mimicry. | Reaction kinetics can be complex; enzyme cost. |

| pH / Supramolecular | pH change or self-assembly | Chitosan (pH), Peptide amphiphiles | Reversible, can mimic ECM dynamics. | Sensitive to environmental conditions. |

Protocol 3.1: In-situ Rheological Monitoring of UV Crosslinking

Objective: To quantify the gelation kinetics and final modulus of a photo-crosslinkable bioink (e.g., 5% w/v GelMA).

Materials:

- Rheometer with UV-curing accessory (light guide, 365 nm LED/lamp).

- GelMA bioink with 0.5% w/v Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoinitiator.

- Quartz or disposable transparent bottom plate.

Procedure:

- Setup: Install the UV-transparent bottom plate and light guide. Set rheometer temperature to 25°C.

- Loading: Load the GelMA-LAP bioink onto the plate. Use a 20 mm parallel plate geometry with a 0.5 mm gap.

- Pre-Cure Measurement: Perform an amplitude sweep to determine the LVR. Set a time-sweep measurement at 1 Hz, 2% strain (within LVR).

- Curing: Start the time sweep. After 30 seconds of baseline measurement, initiate UV exposure at a defined intensity (e.g., 5 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds via the rheometer software trigger.

- Post-Cure: Continue the time sweep for 10 minutes after UV turns off to monitor modulus plateau. Record the gelation time (crossover of G' and G'') and final plateau storage modulus (G').

Printability Assessment Criteria

Printability is a multi-faceted metric encompassing fidelity, resolution, and cell viability.

Protocol 4.1: Quantitative Printability Assessment via Grid Structure

Objective: To evaluate shape fidelity, filament uniformity, and pore uniformity of a printed bioink.

Materials:

- Extrusion bioprinter.

- Bioink in sterile cartridge.

- Printing substrate (e.g., Petri dish, glass slide).

- Calipers or microscope with image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Procedure:

- Design: Design a 10 mm x 10 mm single-layer grid with a 2 mm center-to-center filament spacing.

- Printing: Print the grid under standardized conditions (pressure, speed, nozzle gauge—e.g., 22G, 410 µm).

- Imaging: Allow initial gelation (if needed), then acquire a top-down image under a microscope or scanner.

- Analysis:

- Filament Diameter: Measure diameter at 10 points per filament. Calculate average and coefficient of variation (CV).

- Pore Area: Measure the area of 5 central pores. Calculate average and CV.

- Shape Fidelity: Compare printed pore area (Aprinted) to designed pore area (Adesign = 4 mm²). Fidelity = (Aprinted / Adesign) * 100%.

- Scoring: A printable ink typically exhibits filament diameter CV < 15%, pore area CV < 20%, and shape fidelity > 85%.

Protocol 4.2: Post-Printing Cell Viability Assessment (Live/Dead Assay)

Objective: To determine the immediate and 24-hour post-printing viability of encapsulated cells.

Materials:

- Bioink with encapsulated cells (e.g., 1x10⁶ cells/mL NIH/3T3 fibroblasts).

- Sterile culture medium.

- Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (e.g., Calcein AM / Ethidium homodimer-1).

- Confocal microscope or fluorescence plate reader.

Procedure:

- Printing: Print a simple structure (e.g., a 3-layer lattice) into a sterile well plate.

- Crosslink: Apply the appropriate crosslinking method (e.g., UV, CaCl₂ spray) per the bioink's requirements.

- Culture: Add pre-warmed culture medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Staining: At timepoints T=1h and T=24h post-print: a. Aspirate medium. b. Incubate with Live/Dead stain (e.g., 2 µM Calcein AM, 4 µM EthD-1 in PBS) for 30-45 minutes at 37°C. c. Gently rinse with PBS.

- Imaging & Quantification: Acquure z-stack images via confocal microscopy. Use image analysis software to count live (green) and dead (red) cells in multiple fields of view. Calculate viability: % Viability = (Live cells / Total cells) * 100.

Visualization

Bioink Development & Assessment Workflow

Photo-Crosslinking Mechanism Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Bioink Development & Analysis

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Alginate | Provides ionic crosslinking backbone; low endotoxin critical for cell culture. | Pronova UP MVG (Novamatrix). |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Combines RGD motifs of gelatin with controllable photo-crosslinking. | GelMA Kit (Advanced BioMatrix). |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Cytocompatible, water-soluble photoinitiator for UV/blue light crosslinking. | LAP (Sigma-Aldrich, 900889). |

| Recombinant Human Thrombin | Enzyme for enzymatic crosslinking of fibrin-based bioinks; high purity. | Factor IIa (Enzyme Research Labs). |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Ionic crosslinker for alginate; sterile, tunable concentration (e.g., 100-500 mM). | Prepared in-house, 0.22 µm filtered. |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Dual-fluorescence stain for immediate quantification of cell viability post-print. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, L3224. |

| Rheometer with UV & Temp Control | For comprehensive rheological characterization and in-situ gelation studies. | Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (TA Instruments). |

| Sterile Bioprinting Nozzles | Disposable, cell-friendly nozzles to maintain sterility and reduce shear stress. | 22G-30G conical nozzles (CELLINK). |

| Basement Membrane Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | Thermo-reversible, ECM-rich hydrogel for co-printing or support baths. | Corning Matrigel, 356231. |

Application Notes

Biomimetic scaffold design leverages nature's evolutionary solutions to create synthetic extracellular matrices (ECMs) that guide tissue regeneration. The integration of computational modeling allows for the prediction of scaffold behavior in silico before physical fabrication, optimizing design parameters for specific tissue engineering applications. This approach is critical for advancing the 3D printing of biopolymers like alginate, chitosan, gelatin-methacryloyl (GelMA), and polycaprolactone (PCL), where mechanical properties, pore architecture, and bioactivity must be precisely controlled.

Core Application Principles:

- Hierarchical Structure Imitation: Computational tools (e.g., finite element analysis, FEA) are used to model and replicate the multi-scale porosity found in natural bone, cartilage, or vasculature.

- Dynamic Mechanical Cues: Models simulate mechanical stimuli (e.g., fluid shear stress in perfusion bioreactors) to design scaffolds that promote mechanotransduction pathways in seeded cells.

- Predictive Degradation & Nutrient Diffusion: Computational models forecast scaffold degradation kinetics and nutrient/waste diffusion profiles to match tissue ingrowth rates.

Key Quantitative Benchmarks: Table 1: Target Scaffold Properties for Specific Tissues Based on Biomimetic Design

| Tissue Target | Ideal Porosity (%) | Average Pore Size (µm) | Compressive Modulus (kPa or MPa) | Primary Biomimetic Feature | Modeling Tool Commonly Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancellous Bone | 70-90 | 300-600 | 0.1-2 MPa | Trabecular lattice structure | Topology optimization, FEA |

| Articular Cartilage | 60-80 | 100-300 | 100-1000 kPa | Zonal composition & stratification | Multiphysics simulation |

| Skin | 80-95 | 50-250 | 2-50 kPa | Random fibrous mesh (collagen mimic) | Agent-based modeling |

| Liver | 85-95 | 200-400 | 1-10 kPa | Lobule-like hexagonal unit cells | CFD for perfusion analysis |

| Nerve Guide | 70-85 | 50-150 (axial channels) | 0.5-5 kPa | Aligned topographical guidance | Diffusion-reaction modeling |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Design & FEA of a Biomimetic Trabecular Bone Scaffold

Objective: To design and mechanically simulate a 3D-printable scaffold mimicking human trabecular bone architecture.

Materials & Software:

- Micro-CT scan data of human cancellous bone (public repository, e.g., NIH NLM).

- Image processing software (ImageJ, 3D Slicer).

- CAD/Mesh generation software (Autodesk Fusion 360, Blender, nTopology).

- FEA software (ANSYS, COMSOL, or open-source FEBio).

- Stereolithography (SLA) or Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printer.

- Biopolymer resin or filament (e.g., PCL or PLA for proof-of-concept).

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition & Segmentation:

- Import micro-CT DICOM files into 3D Slicer.

- Apply a threshold filter to segment bone tissue from void space.

- Generate a 3D surface mesh (STL file) of the bone microstructure.

Design Translation & Optimization:

- Import the STL into CAD software. Scale the model to desired dimensions (e.g., 10x10x10 mm).

- Apply a periodic tessellation or unit cell replication to create a scaffold from the bone microstructure pattern.

- Use topology optimization module (if available) to minimize material while maintaining a stiffness target (e.g., 1 MPa).

- Export the final scaffold design as an STL for printing and a finer mesh (e.g., INP, XML) for FEA.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA):

- Import the scaffold mesh into FEA software. Assign material properties (e.g., PCL: E ≈ 350 MPa, ν ≈ 0.3).

- Apply a fixed constraint to the bottom surface and a distributed compressive load (e.g., 10 N) to the top surface.

- Mesh the model with tetrahedral elements and run a static structural analysis.

- Analyze results: von Mises stress distribution, displacement, and effective compressive modulus.

- Iterate the CAD design if stress concentrations exceed material yield strength or if modulus deviates >15% from target.

3D Printing & Validation (Proof-of-Concept):

- Slice the optimized STL using printer-specific software (e.g., Chitubox for SLA, Cura for FDM).

- Print the scaffold using PCL (FDM, nozzle: 110°C, bed: 60°C) or a biocompatible resin (SLA).

- Perform micro-CT on the printed scaffold to compare pore size/porosity to the digital model.

- Conduct mechanical compression testing (ASTM D695) to validate FEA-predicted modulus.

Protocol 2: Modeling & 3D Printing of a Graded Zonal Cartilage Scaffold

Objective: To fabricate a GelMA-based scaffold with zonal variations in density and stiffness mimicking articular cartilage.

Materials & Software:

- Gelatin-methacryloyl (GelMA, 5-20% w/v).

- Photoinitiator (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate, LAP).

- Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D bioprinter.

- Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, SIMPLE algorithm in OpenFOAM).

- Rheometer.

Procedure:

- Computational Zonal Design:

- Design a rectangular scaffold (e.g., 5x5x3 mm) in CAD. Partition it into three horizontal zones (superficial, middle, deep).

- Assign progressively lower porosity (higher density) from the superficial (90%) to deep zone (70%).

- Generate three corresponding STL files with differing internal lattice densities (e.g., gyroid lattice with varying unit cell sizes).

CFD for Perfusion Prediction:

- Import each zonal scaffold STL into CFD software as a fluid domain (porous media).

- Apply a steady-state fluid flow (culture media, μ=0.89 cP) across the scaffold with an inlet velocity of 100 µm/s.

- Simulate and record the wall shear stress (WSS) distribution within each zone. Optimize lattice densities to achieve a WSS gradient (e.g., 1-5 mPa) suitable for chondrocyte culture.

Bioink Preparation & Printing:

- Prepare three separate GelMA bioinks: 5% w/v (superficial zone), 10% w/v (middle zone), 15% w/v (deep zone). Dissolve in PBS with 0.25% w/v LAP.

- Load bioinks into separate syringes. Using a multi-material DLP or extrusion printer, print the scaffold layer-by-layer, changing bioinks at predetermined z-heights according to the CAD model.

- Crosslink each layer with 405 nm blue light (10-20 mW/cm² for 30-60 seconds).

Validation:

- Use confocal microscopy (after staining) to confirm zonal structure.

- Perform oscillatory rheometry on cylindrical samples of each pure bioink to confirm a gradient in storage modulus (G').

- Seed with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) and culture in chondrogenic medium. Analyze zone-specific gene expression (COL2A1, ACAN, PRG4) via qPCR after 21 days.

Signaling Pathways in Biomimetic Scaffold-Cell Interaction

Diagram 1: Key mechano-chemical signaling pathways activated by biomimetic scaffolds.

Experimental Workflow for Integrated Design

Diagram 2: Biomimetic design and modeling workflow for scaffold fabrication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomimetic Scaffold Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl) | Photo-crosslinkable hydrogel mimicking natural ECM; allows cell encapsulation and DLP printing. | Advanced BioMatrix GelMA Kit (Degree of substitution: ~70%). |

| LAP Photoinitiator | Biocompatible initiator for rapid UV/blue light crosslinking of hydrogels (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA). | Sigma-Aldrich, Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate. |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | Biodegradable, thermoplastic polyester for FDM printing; provides mechanical strength for bone scaffolds. | Polysciences, Medical Grade, Mn 45,000-60,000. |

| RGD Peptide | Cell-adhesive motif (Arg-Gly-Asp) conjugated to scaffolds to enhance integrin-mediated cell attachment. | Peptides International, Cyclo(RGDfK). |

| Recombinant Human TGF-β3 | Growth factor for chondrogenic differentiation; can be physically absorbed or covalently bound to scaffold. | PeproTech, Carrier-Free, >97% purity. |

| Alginate (High G-content) | Ionic-crosslinkable biopolymer for extrusion bioprinting; forms gentle gels for cell delivery. | NovaMatrix Pronova SLG100 (G-content >60%). |

| FEBio Studio | Open-source FEA software specifically for biomechanics and biomaterials. | febio.org. |

| Human MSCs | Primary cells for evaluating osteogenic and chondrogenic potential of scaffolds in vitro. | Lonza, Poietics Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. |

| Micro-CT System | Non-destructive 3D imaging for analyzing scaffold porosity, pore size, and mineralized tissue formation. | Bruker SkyScan 1272 (resolution < 5µm). |

From Digital Model to Biological Construct: Cutting-Edge 3D Printing Techniques and Tissue-Specific Applications

Application Notes

Within the thesis on 3D printing of biopolymer scaffolds for tissue engineering, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Direct Ink Writing (DIW) emerge as fundamental, accessible, and versatile extrusion techniques. FDM, utilizing thermoplastic biopolymers, is prized for its mechanical robustness and geometric fidelity, making it suitable for hard tissue models and sacrificial molds. DIW, printing with shear-thinning bioinks, is the cornerstone for cell-laden constructs and soft hydrogel matrices, enabling high cell viability and biological functionality. The choice between methodologies hinges on the target tissue's mechanical requirements, biological objectives, and material constraints.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of FDM and DIW Bioprinting

| Parameter | FDM (Thermoplastic) | DIW (Hydrogel Bioink) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | 50 - 400 µm | 100 - 500 µm |

| Print Temperature | 70 - 250 °C (nozzle) | 4 - 37 °C (stage/nozzle) |

| Cell Incorporation | Post-printing seeding only | Direct encapsulation possible |

| Typical Viability | N/A (acellular printing) | 70% - 95% (cell-laden) |

| Key Mechanical Property | High stiffness (MPa to GPa range) | Low stiffness (Pa to kPa range) |

| Common Biomaterials | PCL, PLA, PLGA | Alginate, GelMA, Collagen, Fibrin |

| Critical Printing Parameter | Nozzle temperature, layer height | Pressure, speed, rheology (viscosity, yield stress) |

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes for Representative Scaffolds (Recent Studies)

| Biopolymer | Method | Key Outcome Metric | Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | FDM | Compressive Modulus | 15 - 85 MPa | Bone tissue engineering |

| PLA/PEG Blend | FDM | Porosity | 60 - 75% | Osteochondral scaffolds |

| Alginate/GelMA | DIW | Cell Viability (Day 1) | 92 ± 3% | Cartilage bioprinting |

| Silk Fibroin | DIW | Shear Storage Modulus (G') | 12.5 kPa | Soft tissue constructs |

| Collagen I | DIW | Gelation Time (37°C) | 5 - 15 min | Dermal models |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FDM Printing of PCL Lattice Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering

Objective: To fabricate a porous, mechanically stable PCL scaffold for subsequent cell seeding and osteogenic studies.

Materials:

- PCL filament (3 mm diameter, Mw ~50,000)

- Commercial or custom FDM bioprinter

- Heated build plate

- Sterile 70% ethanol

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Design & Slicing: Design a 10x10x3 mm 3D lattice (e.g., 0/90° lay-down pattern, pore size 500 µm) using CAD software. Export as STL. Import into slicing software (e.g., Ultimaker Cura). Set layer height to 200 µm, nozzle diameter to 400 µm, nozzle temperature to 85°C, and build plate temperature to 45°C. Generate G-code.

- Printer Setup: Load PCL filament. Allow nozzle and bed to reach set temperatures. Perform standard purging and priming.

- Sterilization: Wipe the build plate with 70% ethanol and allow to dry.

- Printing: Initiate print. Monitor first layer adhesion.

- Post-processing: After completion, carefully remove the scaffold. For cell culture, sterilize by immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes, followed by three 15-minute washes in sterile PBS under UV light. Place in culture medium for preconditioning before cell seeding.

Protocol 2: DIW of Cell-Laden Alginate/GelMA Bioink for Soft Tissue Constructs

Objective: To bioprint a living construct with high post-print viability for soft tissue modeling.

Materials:

- Bioink: 3% (w/v) Alginate, 5% (w/v) GelMA, 0.5% LAP photoinitiator.

- Cell type (e.g., NIH/3T3 fibroblasts) at 80% confluency.

- DIW bioprinter (pneumatic or mechanical extrusion).

- Crosslinking solution: 100 mM CaCl₂ in PBS.

- UV light source (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²).

- Sterile printing cartridges and nozzles (22G-27G).

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation: Sterilize alginate and GelMA solutions by filtration (0.22 µm). Mix to final concentrations. Add LAP and mix thoroughly. Keep at 37°C until use.

- Cell Harvest & Encapsulation: Trypsinize cells, centrifuge, and resuspend in a small volume of bioink to achieve a final density of 5-10 x 10⁶ cells/mL. Gently mix without introducing bubbles. Keep on ice or at room temperature to prevent premature gelation.

- Printer Setup: Load cell-laden bioink into a sterile cartridge. Attach a conical nozzle (e.g., 25G, ~250 µm inner diameter). Mount onto the printer. Set stage temperature to 15-20°C.

- Printing Parameters: Optimize pressure (typically 15-30 kPa) and speed (5-15 mm/s) for continuous filament formation. Print a 15x15 mm grid structure (2-5 layers).

- Dual Crosslinking: Immediately after deposition, spray or mist with CaCl₂ solution for ionic crosslinking of alginate (30-60 s). Subsequently, expose the entire construct to UV light (365 nm, 30-60 seconds) for covalent crosslinking of GelMA.

- Post-print Culture: Gently transfer constructs to a 6-well plate, wash with warm PBS, and add complete culture medium. Assess viability via Live/Dead assay at 24 hours.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Extrusion Bioprinting Research

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) Filament | FDM thermoplastic for hard, biodegradable scaffolds. | Molecular weight affects viscosity & degradation rate. |

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl) | Photo-crosslinkable DIW bioink backbone. | Degree of functionalization controls mechanics & cell adhesion. |

| Alginate, High G-Content | DIW bioink for ionic gelation; provides shape fidelity. | Purification level impacts cytocompatibility. |

| LAP Photoinitiator | Initiates GelMA crosslinking under UV (365-405 nm). | Low cytotoxicity and efficient at low concentrations (~0.25%). |

| Sterile CaCl₂ Solution (100mM) | Ionic crosslinker for alginate; induces rapid gelation. | Concentration affects gelation speed and final stiffness. |

| Rheology Modifiers (e.g., nanoclay, methylcellulose) | Modifies bioink viscoelasticity for printability. | Must be cytocompatible and not interfere with crosslinking. |

| Cell-Ready PBS | For bioink dilution, washing, and reagent preparation. | Must be calcium/magnesium-free if used with alginate before crosslinking. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Tester | Quantifies storage/loss moduli (G', G'') of bioinks. | Critical for determining shear-thinning and recovery behavior. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing of biopolymer scaffolds for tissue engineering, this document details the application of vat photopolymerization techniques—specifically Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP). These light-based methods offer superior resolution and surface finish, enabling the fabrication of scaffolds with precise architectural features that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM). This precision is critical for controlling cell-material interactions, guiding tissue regeneration, and advancing drug screening platforms.

Comparative Analysis: SLA vs. DLP for Biopolymer Scaffolds

The fundamental difference lies in the light source and patterning mechanism. SLA uses a single UV laser point to scan and cure each layer, while DLP projects a single UV image of an entire layer at once via a digital micromirror device (DMD). The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of SLA and DLP for Biopolymer Fabrication

| Parameter | Stereolithography (SLA) | Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Significance for Tissue Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | UV Laser (e.g., 355 nm, 405 nm) | UV LED Projector (e.g., 385 nm, 405 nm) | Wavelength dictates photoinitiator selection & cytocompatibility. |

| Typical XY Resolution | 25 - 150 µm | 10 - 50 µm | DLP offers finer features, beneficial for small-diameter vascular channels. |

| Layer Thickness (Z) | 10 - 100 µm | 10 - 50 µm | Thinner layers improve vertical feature resolution & surface finish. |

| Print Speed | Slower (point-by-point scanning) | Faster (full-layer projection) | DLP throughput is higher, advantageous for high-throughput scaffold production. |

| Common Biopolymers | Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA), Hyaluronic acid (HAMA), PEGDA | Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA), Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), Methacrylated silk fibroin | Materials require functionalization with photoreactive groups (e.g., acrylates, methacrylates). |

| Critical Energy (Ec) | 25 - 150 mJ/cm² (material dependent) | 25 - 150 mJ/cm² (material dependent) | Minimum energy required for gelation; key for protocol optimization. |

Application Notes

Material Selection & Bioink Formulation

The core requirement is a photocrosslinkable biopolymer "resin." GelMA is predominant due to its inherent bioactivity and tunable mechanical properties. A typical formulation includes:

- Photopolymer: GelMA (5-15% w/v).

- Photoinitiator: Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) (0.1-0.5% w/v) is preferred over Irgacure 2959 due to better water solubility and curing efficiency at 405 nm.

- Light Absorber: Optional addition of tartrazine (e.g., 0.05% w/v) to control penetration depth and improve XY resolution.

Design for Light-Based Printing

- Support Structures: Necessary for overhangs >45° in SLA; often less critical in DLP with a bottom-up orientation.

- Pixel Calibration (DLP): Essential to account for optical distortion and ensure dimensional accuracy. A calibration grid print is recommended.

- Exposure Optimization: A critical print parameter determined by the "working curve" (penetration depth, Dp, vs. exposure energy).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Curing Parameters via Working Curve

Objective: To establish the relationship between UV exposure energy and cured layer thickness for a new bioink formulation.

Materials:

- Photocurable bioink (e.g., 10% GelMA, 0.25% LAP).

- SLA or DLP printer with calibrated light source.

- Glass slides or printing substrate.

- Micrometer or profilometer.

Method:

- Sample Exposure: Dispense a small pool of bioink onto a substrate. Expose to a single UV light pattern (e.g., a rectangle) with varying exposure times (e.g., 1, 2, 5, 10, 15 s). Keep light intensity constant.

- Washing: Gently rinse uncured material with warm PBS.

- Measurement: Measure the thickness of each cured rectangle using a micrometer.

- Calculation: Calculate exposure energy (E) for each time (t): E = I * t, where I is irradiance (mW/cm²). Measure irradiance with a radiometer.

- Model Fitting: Plot cured depth (Cd) vs. ln(Exposure Energy, E). Fit data to the Jacobs Working Curve equation: Cd = Dp * ln(E / Ec).

- Dp (Penetration Depth): Slope, indicates depth at which irradiance drops to 1/e. Higher Dp means deeper curing.

- Ec (Critical Energy): X-intercept, minimum energy for gelation.

Table 2: Example Working Curve Data for 10% GelMA / 0.25% LAP at 405 nm

| Exposure Time (s) | Exposure Energy, E (mJ/cm²) | Cured Depth, Cd (µm) | ln(E) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 40 | 85 | 3.69 |

| 5 | 100 | 175 | 4.61 |

| 10 | 200 | 285 | 5.30 |

| 15 | 300 | 360 | 5.70 |

| Calculated Dp | ~200 µm | ||

| Calculated Ec | ~25 mJ/cm² |

Protocol: SLA/DLP Printing of a Lattice Scaffold for Cell Seeding

Objective: To fabricate a high-resolution 3D porous scaffold for subsequent in vitro cell culture studies.

Pre-Print:

- Design: Create a 3D model (e.g., .STL) of a gyroid or rectangular lattice with pore size 300-500 µm and strut diameter of 150-200 µm.

- Bioink Preparation: Synthesize and functionalize polymer (e.g., GelMA). Dissolve in PBS with LAP at 37°C. Sterile filter (0.22 µm).

- Printer Setup: Sterilize resin vat and build platform with 70% ethanol and UV light. Calibrate build platform.

Printing (DLP Bottom-Up Example):

- Parameters: Set layer thickness (e.g., 50 µm). Calculate layer exposure time (t): t = (Ec + (layer thickness / Dp)) / I. Using Table 2 data and I=20 mW/cm²: t = (25 + (50/200)) / 20 = ~1.4 seconds per layer.

- Print: Initiate print. The build platform lowers into the bioink, the DMD projects the first layer image for the calculated t, the platform lifts to allow resin recoat, and the cycle repeats.

Post-Print:

- Retrieval: Carefully remove scaffold from the build plate.

- Washing: Rinse in sterile PBS to remove uncured precursor.

- Post-Curing: Optional exposure to a broad-spectrum UV light to ensure complete crosslinking.

- Characterization: Image via SEM/micro-CT. Perform mechanical testing (compressive modulus).

- Cell Seeding: Sterilize scaffolds in antibiotic solution. Seed with cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells) at a density of 1-5 million cells/mL scaffold volume via pipette or vacuum seeding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SLA/DLP Bioprinting

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | Gold-standard photocurable bioink; provides RGD motifs for cell adhesion and tunable degradability. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Highly efficient, water-soluble photoinitiator activated by 405 nm light; enables rapid gelation at low concentrations. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Bio-inert, synthetic polymer used to create precise hydrogels; modulus easily tuned by weight % or molecular weight. |

| Digital Micromirror Device (DLP) Evaluation Kit | Allows researchers to modify and calibrate DLP projection parameters for custom printer builds. |

| UV Radiometer | Critical for measuring irradiance (mW/cm²) at the build plane to accurately calculate exposure energy. |

| Silicone-coated Release Liner (for bottom-up DLP) | Creates a non-stick, oxygen-permeable inhibition layer at the vat bottom, preventing adhesion and facilitating resin recoating. |

Visualized Workflows & Pathways

SLA and DLP Bioprinting Workflow

Exposure Energy Effects on Scaffold Properties

This application note, framed within a thesis on 3D biopolymer printing, details protocols for fabricating and characterizing scaffolds for three distinct regenerative targets. The convergence of biomaterial science and additive manufacturing enables the creation of spatially defined, bioactive constructs that mimic native tissue microenvironments.

Table 1: Key Biomaterial Properties for Target Tissues

| Tissue Type | Ideal Scaffold Modulus (MPa) | Target Porosity (%) | Degradation Time (Weeks) | Key Bioactive Cues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | 50 - 2000 | 70 - 90 | 8 - 52 | Ca²⁺/PO₄³⁻, BMP-2, RGD peptide |

| Cartilage | 0.1 - 1 | 60 - 80 | 12 - 104 | TGF-β3, HA, Chondroitin Sulfate |

| Vascular | 0.5 - 5 (compliant) | 75 - 85 | 8 - 16 (temporary) | VEGF, PDGF, SDF-1α |

Table 2: Common Biopolymers & Composite Formulations

| Biopolymer Base | Crosslinking Method | Bioink Concentration (w/v%) | Key Additive (for Composite) | Print Fidelity Score* (1-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Ionic (CaCl₂) | 3 - 5% | Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) | 3 |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo (UV, LAP) | 5 - 15% | Hyaluronic Acid Methacrylate | 4 |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Thermal | N/A (melt) | Tricalcium Phosphate (TCP) | 5 |

| Fibrin | Enzymatic (Thrombin) | 10 - 20 mg/mL | Heparin (for GF binding) | 2 |

*Score: 1=Poor, 5=Excellent shape fidelity & resolution.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Extrusion 3D Printing of GelMA-nHA Composite for Bone

Objective: Fabricate an osteogenic, mechanically robust scaffold. Materials:

- GelMA (Degree of substitution >70%)

- Photoinitiator LAP (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate)

- Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) powder (<200 nm)

- Sterile PBS, Bioprinter (extrusion-based), 405 nm UV light source.

Method:

- Bioink Preparation: Dissolve GelMA at 10% w/v in PBS at 37°C. Add LAP to 0.25% w/v. Gradually incorporate nHA at 5% w/v of total polymer weight under vigorous stirring. Centrifuge (2000 x g, 5 min) to degas.

- Printing: Load ink into a sterile cartridge. Use a 22G nozzle (410 μm). Set printing parameters: Pressure = 25-30 kPa, Speed = 8 mm/s, Bed Temp = 15°C. Print a 0/90° lattice (10x10x2 mm).

- Crosslinking: Immediately post-print, irradiate with 405 nm UV light (5 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds per layer.

- Post-Processing: Wash scaffolds 3x in PBS. Store in cell culture medium at 37°C for 24 hrs before mechanical testing or seeding.

Protocol 3.2: Digital Light Processing (DLP) of Alginate-Diacrylate for Cartilage

Objective: Create high-resolution, chondro-permissive scaffolds with encapsulated cells. Materials:

- Sodium Alginate, Methacrylic anhydride

- Photoinitiator (VA-086), Chondroitin sulfate

- Primary chondrocytes, DLP Bioprinter, Digital micromirror device (DMD) projector.

Method:

- Synthesis of Alginate-Diacrylate (AlgDA): React 2% w/v alginate with 0.5 mL methacrylic anhydride per gram of alginate in deionized water, pH 8-9, 4°C for 24h. Purify via dialysis and lyophilize.

- Cell-laden Bioink: Dissolve AlgDA at 3% w/v and chondroitin sulfate at 1% w/v in DMEM. Add VA-086 (0.1% w/v). Gently mix with chondrocytes (20x10⁶ cells/mL).

- DLP Printing: Load resin into vat. Project a series of 2D slice images (50 μm layer thickness, 10s exposure per layer at 405 nm, 15 mW/cm²) to cure the full 3D construct.

- Ionic Reinforcement: Post-print, submerge scaffolds in 100 mM CaCl₂ solution for 5 min to provide secondary ionic crosslinking. Rinse and culture in chondrogenic medium.

Protocol 3.3: Coaxial Printing of PCL-GelMA Core-Sheath for Vasculature

Objective: Fabricate a perfusable, endothelialized tubular construct. Materials:

- PCL pellets (Mn 45,000), GelMA (as in 3.1)

- Coaxial printhead (inner: 25G, outer: 21G), Heated extrusion system.

- HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells).

Method:

- Material Prep: Melt PCL at 90°C in a separate printer cartridge. Prepare cell-laden GelMA (7.5% w/v with 0.15% LAP and 5x10⁶ HUVECs/mL) as in 3.1.

- Coaxial Printing: Mount coaxial nozzle. Set PCL (core) to 95°C, pressure 80 kPa, speed 5 mm/s. Set GelMA (sheath) to 25°C, pressure 40 kPa. Print a tubular spiral (ID=2 mm, height=10 mm).

- Simultaneous Crosslinking: Use a focused UV spot (365 nm, 10 mW/cm²) directed at the point of deposition to instantly photopolymerize the GelMA sheath.

- Maturation: Transfer construct to bioreactor, perfuse with EGM-2 medium at 5 mL/min, 1 Hz pulsatile flow for 7 days to promote endothelial monolayer formation.

Signaling Pathways & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram Title: BMP & Integrin Signaling in Bone Regeneration

Diagram Title: Workflow for 3D Bioprinted Cartilage Scaffolds

Diagram Title: Perfusion & VEGF Drive Vascular Maturation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biopolymer Scaffold Fabrication

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Supplier/Cat. #* |

|---|---|---|

| GelMA (High DoS) | Gold-standard photocrosslinkable hydrogel; provides cell-adhesive motifs and tunable mechanics. | Advanced BioMatrix, 5010-DS-050 |

| LAP Photoinitiator | Biocompatible, water-soluble photoinitiator for visible light crosslinking (405 nm). | Sigma-Aldrich, 900889 |

| Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) | Mineral component of bone; enhances osteoconductivity and compressive modulus of composites. | Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials, 1006 |

| Alginate Diacrylate (AlgDA) | Combines alginate's gentle ionic gelation with controllable covalent photocrosslinking for high-resolution prints. | Prepared in-lab per Protocol 3.2 |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Biodegradable, thermoplastic polyester for melt extrusion; provides long-term structural support. | Sigma-Aldrich, 440744 |

| Recombinant Human TGF-β3 | Key inductive growth factor for chondrogenesis in cartilage scaffolds. | PeproTech, 100-36E |

| Recombinant Human VEGF₁₆₅ | Critical factor for endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and vascular tube formation. | R&D Systems, 293-VE-050 |

| Dynamic Perfusion Bioreactor | Provides physiological shear stress to vascular constructs, enhancing endothelial cell maturation. | Instron (Bose) ElectroForce, or custom systems. |

*Supplier examples are for reference; equivalents are available.

Application Notes

Multi-Material Printing for Biomimetic Scaffolds

Application: Fabrication of osteochondral tissue scaffolds. Multi-material extrusion printing allows for the deposition of distinct bioinks, each tailored to the chondral (cartilage) and subchondral (bone) regions, mimicking the native zonal composition and graded mechanical properties. Key Data: The table below summarizes print parameters and outcomes for a representative osteochondral construct.

Table 1: Print Parameters & Outcomes for a Dual-Material Osteochondral Scaffold

| Region | Biopolymer Composite | Nozzle Temp (°C) | Print Pressure (kPa) | Layer Height (µm) | Post-Print Modulus (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chondral | 4% Alginate / 3% Hyaluronic Acid / Chondrocytes | 22 (cold) | 25 | 150 | 12 ± 3 |

| Osseous | 5% GelMA / 10% β-TCP / MSCs | 28 | 35 | 200 | 850 ± 120 |

Protocol: Multi-Material Printing of Graded Osteochondral Scaffold

- Bioink Preparation: Prepare chondral and osseous bioinks as per Table 1. Sterilize materials via 0.22 µm filtration (polymers) or UV irradiation (ceramics). Mix cells at a density of 10x10^6 cells/mL into the respective pre-gel solutions just before printing.

- Printer Setup: Configure a dual-extrusion bioprinter with temperature-controlled printheads. Load bioinks into separate sterile syringes fitted with conical nozzles (25G for chondral, 22G for osseous).

- Print Path Programming: Design a cylindrical scaffold (Ø10mm x 4mm) with a defined interface. Program a 0/90° laydown pattern. For the lower 2mm, assign the osseous bioink; for the upper 2mm, assign the chondral bioink.

- Print Execution: Maintain stage at 15°C. Print the osseous layers first. Pause at the interface, purge nozzles with sterile PBS if needed, and switch to the chondral bioink to complete the construct.

- Crosslinking: Post-print, immerse scaffold in 2% CaCl₂ solution (for alginate) for 5 min, then expose to 405 nm light (5 mW/cm², 60 sec) for GelMA crosslinking.

- Culture: Transfer to chondrogenic medium for the upper half and osteogenic medium for the lower half in a biphasic culture system.

Embedded Printing for Complex Vasculature

Application: Creation of free-form, perfusable vascular networks within a bulk soft matrix. Embedded 3D printing (FRESH, SWIFT, or suspension printing) enables the deposition of fugitive or crosslinkable inks within a supportive yield-stress hydrogel bath, preventing collapse during printing. Key Data: Parameters for printing a perfusable endothelialized network.

Table 2: Parameters for Embedded Printing of a Perfusable Network

| Component | Material | Print Speed (mm/s) | Pressure (kPa) | Fiber Diameter (µm) | Post-Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fugitive Ink | 4% Carbowax (PEG) + 0.5% Laponite | 8 | 45 | 250 | 4°C chilling to solidify |

| Support Bath | 1.5% Microgelated Alginate / 2% Gelatin | N/A | N/A | N/A | 37°C liquefaction for removal |

| Matrix Ink | 5% Fibrinogen / Collagen I | 6 | 30 | N/A | Thrombin crosslink |

Protocol: Embedded Printing of a Perfusable Vascular Channel

- Support Bath Synthesis: Prepare a yield-stress bath by mixing microgelated alginate particles with gelatin. Pour into a printing chamber and equilibrate to 15°C.

- Fugitive Ink Deposition: Load fugitive ink into a cooled syringe (4°C). Print a branching network design within the support bath. The bath's shear-thinning property allows nozzle movement and immediate self-healing to support the printed structure.

- Matrix Casting: Gently infiltrate the pre-cooled matrix ink (fibrinogen/collagen) around the printed fugitive network using a pipette, avoiding direct disruption.

- Crosslinking & Removal: Raise temperature to 37°C to melt the gelatin in the bath and liquefy the periphery. Gently wash away the support bath with warm PBS. Add thrombin solution (2 U/mL) to crosslink the fibrin matrix. Lower temperature to 4°C to solidify the fugitive ink.

- Channel Evacuation: Apply gentle vacuum or pressure-driven flow of cold PBS to evacuate the liquefied fugitive ink, leaving behind patent, interconnected channels.

- Endothelialization: Inject a suspension of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs, 5x10^6 cells/mL) into the channels and allow for adhesion under rotational culture (2 rpm, 30 min).

4D Shape-Morphing Scaffolds for Dynamic Structures

Application: Self-rolling tubular constructs for neural guide conduits. 4D printing involves designing 2D or 3D constructs with anisotropic, stimuli-responsive materials that evolve into a pre-programmed 4D shape (space + time) under a specific trigger (e.g., hydration, temperature). Key Data: Design and actuation parameters for a self-rolling bilayer tube.

Table 3: Design & Actuation of a 4D Bilayer Neural Conduit

| Layer | Biopolymer | Crosslink Density | Print Speed (mm/s) | Swelling Ratio (Hydration) | Trigger | Actuation Time (min) | Final Curvature (mm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | 8% GelMA | Low (0.1% Photoinitiator) | 10 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 37°C PBS | 15 ± 2 | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| Passive | 8% GelMA | High (0.3% Photoinitiator) | 8 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Protocol: 4D Printing of a Self-Rolling Tubular Conduit

- Anisotropic Bioink Design: Prepare two batches of GelMA bioink. For the active, high-swelling layer, use a low concentration of photoinitiator (LAP, 0.1% w/v). For the passive, restrictive layer, use a high concentration (0.3% w/v).

- 2D Pattern Printing: Print a flat, rectangular bilayer construct (20mm x 5mm) onto a hydrophobic substrate. First, print the passive layer. Immediately print the active layer directly on top. Use 405 nm light (15 mW/cm², 30 sec per layer) for crosslinking.

- 4D Activation Mechanism: Upon immersion in 37°C PBS, the active layer hydrates and swells significantly more than the passive layer. This differential swelling strain generates a bending moment.

- Shape Morphing: The imposed strain causes the flat bilayer sheet to progressively bend, rolling around the long axis to form a tubular conduit. The final diameter is dictated by the width of the sheet and the differential swelling ratio.

- Validation & Cell Seeding: Measure the kinetics of rolling and final tube diameter. Seed Schwann cells or neural progenitors into the lumen after morphing is complete.

Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for Multi-Material Osteochondral Scaffold

Diagram 2: Embedded Printing of Vascular Network

Diagram 3: 4D Shape-Morphing Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Bioprinting

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | A photo-crosslinkable, cell-adhesive hydrogel workhorse. Used for multi-material and 4D printing due to tunable mechanical properties. |

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Rapid ionic crosslinking (with Ca²⁺) allows for structural fidelity in multi-material prints and is used in support bath formulations. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (Methacrylated) | Provides bioactive cues for chondrogenesis; used in chondral bioinks. Modifiable for crosslinking. |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Microparticles | Osteoconductive filler for osseous bioinks, enhancing mechanical stiffness and bioactivity. |

| Laponite RD Nanoclay | Rheological modifier to impart shear-thinning and yield-stress properties for embedded printing support baths and bioink reinforcement. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) with Pluronic F127 | A fugitive (sacrificial) ink for embedded printing of channels; liquefies upon cooling for easy removal. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A biocompatible photoinitiator for visible light (405 nm) crosslinking of methacrylated polymers (GelMA, Hyaluronic Acid). |

| Microgelated Alginate Particles | Key component of granular support baths for embedded printing, providing a yield-stress, self-healing environment. |

Overcoming Fabrication Hurdles: Strategies for Optimizing Print Fidelity, Mechanics, and Cellular Response

Nozzle Clogging in Biopolymer Extrusion

Application Notes: Nozzle clogging is a predominant failure mode when printing viscous, particle-filled, or thermosensitive biopolymer inks (e.g., alginate, chitosan, collagen, PLGA). Clogging results from premature crosslinking, thermal degradation, particle aggregation, or improper rheological management.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 1: Common Biopolymers, Their Clogging Risks, and Mitigation Parameters

| Biopolymer | Typical Concentration | Key Clogging Risk Factor | Recommended Nozzle Diameter (µm) | Critical Printing Temperature | Viscosity Range (Pa·s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 2-4% (w/v) | Ionic crosslinking at tip | 200-600 | 20-25°C (Ambient) | 10-200 |

| Chitosan | 2-3% (w/v) in weak acid | High viscosity, shear-thinning | 400-800 | 20-37°C | 50-500 |

| PLGA | 10-30% (w/v) in solvent | Solvent evaporation at tip | 150-400 | 20-25°C (Ambient) | 200-2000 |

| Collagen Type I | 5-10 mg/mL | Thermal gelation (> 20°C) | 250-500 | 4-10°C (Cold plate) | 1-50 |

| Silk Fibroin | 15-30% (w/v) | β-sheet crystallization | 100-300 | 20-25°C | 100-1000 |

Experimental Protocol: Protocol for Assessing and Preventing Nozzle Clogging

- Ink Rheological Characterization:

- Using a cone-and-plate rheometer, perform a shear rate sweep (0.1 to 100 s⁻¹) at the printing temperature to confirm shear-thinning behavior.

- Conduct a time sweep at constant shear rate (10 s⁻¹) for 30 minutes to monitor viscosity stability.

- Nozzle Health Assessment:

- Before printing, extrude ink into a weigh boat for 60 seconds at the target pressure/flow rate. Weigh the extrudate. Repeat thrice. A >15% decrease in mass indicates incipient clogging.

- Inspect the extruded filament under a stereomicroscope for consistent diameter and surface smoothness.

- Preventive Nozzle Priming and Cleaning:

- For aqueous biopolymers: Prime the nozzle/system with a 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 solution, followed by a rinse with sterile PBS or deionized water.

- For solvent-based biopolymers (PLGA): Prime with the matching pure solvent (e.g., DMSO, Hexafluoroisopropanol).

- Between prints, implement a stringent cleaning protocol: physical clearing with a precision wire (e.g., 70µm diameter for a 200µm nozzle), followed by sonic bath in appropriate solvent/cleaner for 5 minutes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Clogging Mitigation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Sterile, Low-Protein-Binding Filters (e.g., 5-40 µm) | Pre-filtration of ink to remove aggregates before loading into the print cartridge. |

| Rheology Modifiers (e.g., Glycerol, Laponite RD) | Adjust ink viscoelastic properties to enhance shear-thinning and reduce post-extrusion swelling. |

| Crosslinking Modulators (e.g., Ca-EDTA for alginate) | For ionic crosslinkers, use chelators to delay gelation until after extrusion. |

| Temperature-Controlled Print Bed/Nozzle Sleeve | Maintains ink below its gelation or degradation temperature throughout the fluid path. |

| Precision Nozzle Cleaning Kit (Wires, Brushes) | For physical removal of cured material from the nozzle lumen. |

Title: Workflow for Biopolymer Nozzle Clogging Prevention

Layer Delamination in Scaffold Fabrication

Application Notes: Layer delamination (poor interlayer adhesion) compromises scaffold structural integrity and pore interconnectivity. For biopolymers, causes include insufficient binding chemistry, rapid drying/solidification, and inadequate surface energy between layers.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 2: Strategies to Enhance Interlayer Adhesion for Common Biopolymers

| Biopolymer | Primary Solidification Mechanism | Adhesion-Promoting Strategy | Quantitative Improvement in Bond Strength | Key Parameter for Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Ionic (Ca²⁺) Crosslinking | Partial-Dry Layer Printing | Bond strength increase up to 300% | Layer Drying Time (5-15 sec) |

| Chitosan | Solvent Evaporation / pH Shift | Solvent Vapor Exposure | Interlayer diffusion depth increased by 50µm | NH₄OH Vapor Exposure Time |

| PLGA | Solvent Evaporation / Sintering | Chloroform Vapor Smoothing | Tensile strength increase of 200% | Vapor Exposure Duration (10-30s) |

| Collagen | Thermal Gelation / pH Neutralization | Controlled Humidity (>95% RH) | Prevents premature drying, improves fusion | Chamber Humidity & Temperature |

| Silk Fibroin | Alcohol-Induced Crystallization | Methanol Vapor Post-Processing | Creates unified β-sheet network across layers | Methanol Exposure (10-60 min) |

Experimental Protocol: Protocol for Quantifying and Preventing Layer Delamination

- Scaffold Printing for Tensile Test:

- Print a standardized rectangular scaffold (e.g., 20 x 5 x 3 mm, 0/90° laydown pattern).

- Use identical process parameters except for the variable under test (e.g., layer drying time, humidity).

- Uniaxial Tensile Testing:

- Mount scaffold ends on a micro-tensile tester (e.g., Instron 5943 with a 10N load cell).

- Apply tension at a constant strain rate (e.g., 1 mm/min) until failure.

- Record stress-strain curve. Note failure mode: interlayer (delamination) vs. intra-layer.

- Interlayer Fusion Quality Assessment:

- Soak scaffold in PBS for 24h at 37°C.

- Perform micro-CT scan at <10µm resolution.

- Use image analysis (e.g., ImageJ) to measure pore connectivity and identify delamination gaps at layer interfaces.

- Adhesion-Promoting Protocol (Example - Alginate):

- Print first layer. Expose to gentle air flow (or controlled RH) for a precise time (e.g., 8 seconds) to create a partially dry, tacky surface.

- Immediately print the subsequent layer. The wet filament from the nozzle will partially re-dissolve the surface, creating molecular entanglement upon final crosslinking.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Layer Adhesion

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Humidity & Temperature-Controlled Print Chamber | Prevents rapid evaporation/drying, allowing molecular diffusion between layers. |

| Crosslinking Agent Nebulizer (e.g., CaCl₂ mist for alginate) | Provides a fine mist for gradual, uniform crosslinking throughout the depth of the print. |

| Solvent Vapor System (e.g., Ethanol, Chloroform) | Temporarily softens the surface of a previously printed layer to enable fusion with the new layer. |

| Plasma Treatment Device (Low-pressure) | Increases surface energy of a cooled/stable layer to improve wettability by the next ink layer. |

| Adhesive Sacrificial Support Hydrogels (e.g., Carbopol) | Provides temporary mechanical support to overhanging layers during printing and slow crosslinking. |

Title: Root Cause and Solutions for Layer Delamination

Dimensional Inaccuracy in Scaffold Printing

Application Notes: Dimensional inaccuracy (shrinking, swelling, warping) critically affects scaffold pore size, strut thickness, and overall architecture, directly influencing cell seeding and tissue ingrowth. Causes include material shrinkage post-processing, mechanical compliance of soft inks, and printer kinematic errors.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 3: Post-Processing Dimensional Change in Biopolymer Scaffolds

| Biopolymer | Typical Post-Process | Measured Linear Shrinkage (%) | Swelling in PBS (37°C) after 24h (%) | Compensatory Scale Factor (CAD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 100mM CaCl₂, 10 min | 5-15% | +20 to +40% | 1.10 - 1.18 |

| Chitosan | NH₄OH Vapor, 30 min | 8-12% | +10 to +25% | 1.09 - 1.14 |

| PLGA | Vacuum Dry, 24h | 20-35% (due to solvent loss) | Negligible (<2%) | 1.25 - 1.54 |

| Collagen | 37°C, 95% RH, 30 min | 10-20% (during gelation) | +50 to +200% (Hydrogel) | 1.12 - 1.25 |

| Silk Fibroin | 90% Methanol, 1hr | 5-10% | +5 to +15% | 1.05 - 1.11 |

Experimental Protocol: Protocol for Calibrating and Validating Dimensional Accuracy

- Printer Kinematic Calibration:

- Print a single-layer calibration pattern (e.g., a 20 x 20 mm grid of 100 µm lines).

- Measure actual line distances and nozzle travel using a calibrated optical microscope or laser micrometer.

- Calculate and input X, Y, and E-step (extrusion) correction factors into printer firmware.

- Material-Specific Shrinkage Compensation:

- Design and print a benchmark scaffold (e.g., 10x10x2 mm with 300 µm pores).

- Process it through the standard post-processing protocol (crosslinking, drying, etc.).

- Measure the final, stable dimensions (after 24h in PBS if applicable) using micro-CT or high-resolution calipers.

- Compute the linear scaling factor in X, Y, and Z (Final Dimension / Designed Dimension).

- Apply the inverse of this factor to the original CAD model before subsequent prints.

- In-Process Dimensional Monitoring:

- Integrate a laser line scanner or confocal displacement sensor into the printer gantry.

- Scan the top surface of every 5th layer during printing.

- Compare the measured height and feature placement to the G-code command. Implement real-time adjustment or flag significant deviations (>5%).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Dimensional Fidelity

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Dimensionality-Stable Support Bath (e.g., FRESH, Carbopol) | Enables printing of low-viscosity inks into a support medium that minimizes deformation under gravity. |

| Graded Crosslinking Agents (e.g., Ba²⁺ for alginate) | Use of slower-diffusing or stronger crosslinkers can reduce anisotropic shrinkage. |

| Plasticizers (e.g., Glycerol, PEG) | Incorporated into ink formulation to reduce internal stresses and shrinkage during solvent evaporation. |

| Calibrated Micro-CT Imaging System | For non-destructive, high-resolution 3D measurement of internal and external scaffold geometry post-print. |

| Sintering Oven with Programmable Ramp | For synthetic polymers like PCL, controlled thermal sintering reduces warping and improves accuracy. |

Title: Dimensional Accuracy Calibration and Validation Workflow

Context: This document details practical protocols for tuning the mechanical performance of 3D-printed biopolymer scaffolds, a critical requirement for matching the native tissue environment in regenerative medicine. The strategies are framed within a doctoral thesis focusing on developing osteochondral scaffolds.

1. Protocol: Optimization of Genipin Crosslinking for Chitosan-Gelatin Scaffolds

Objective: To systematically determine the optimal genipin concentration for crosslinking 3D-printed chitosan-gelatin scaffolds, maximizing compressive modulus while maintaining cytocompatibility.

Materials:

- 3D-printed chitosan (4% w/v) - gelatin (8% w/v) scaffold (10 mm diameter x 5 mm height).

- Genipin (≥98% purity) stock solution (1% w/v in DMSO).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100% v/v).

- Mechanical tester (e.g., Instron 5944) with 100 N load cell.

- Microplate reader for MTT assay.

Procedure:

- Prepare crosslinking solutions of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0 mM genipin in PBS.

- Immerse scaffolds (n=5 per group) in each solution for 24 hours at 37°C in the dark.

- Rinse scaffolds thoroughly with PBS to remove unreacted genipin.

- Lyophilize scaffolds for 24 hours.

- Compressive Testing: Rehydrate scaffolds in PBS for 1 hour. Perform uniaxial compression test at a strain rate of 1 mm/min. Record the compressive modulus from the linear elastic region (typically 5-15% strain).

- Cytocompatibility (MTT Assay): Seed human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) at 20,000 cells/scaffold onto crosslinked and rinsed scaffolds. Culture for 72 hours. Add MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL) and incubate for 4 hours. Dissolve formazan crystals in DMSO and measure absorbance at 570 nm.

Quantitative Data Summary:

Table 1: Effect of Genipin Crosslinking on Scaffold Properties

| Genipin Concentration (mM) | Compressive Modulus (kPa) | MTT Metabolic Activity (% vs 0 mM Control) | Crosslinking Density (µmol/cm³)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 (Control) | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 100.0 ± 8.2 | 0.0 |

| 0.1 | 28.4 ± 3.1 | 98.5 ± 7.1 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

| 0.3 | 55.7 ± 6.5 | 102.3 ± 6.5 | 12.8 ± 1.4 |

| 0.5 | 89.2 ± 9.3 | 95.1 ± 5.9 | 21.5 ± 2.1 |

| 0.7 | 115.6 ± 12.1 | 88.4 ± 4.7 | 28.9 ± 2.8 |

| 1.0 | 135.8 ± 15.7 | 72.1 ± 6.3 | 35.4 ± 3.5 |

*Calculated via ninhydrin assay.

2. Protocol: Melt Electrowriting (MEW) of PCL Microfibers for Reinforcement

Objective: To fabricate Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) microfiber meshes via MEW for use as reinforcing networks within soft biopolymer matrices.