The Polymer Science of Stability: How Molecular Weight Governs Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) in Drug Development

This comprehensive review examines the fundamental and applied relationship between molecular weight (Mw) and glass transition temperature (Tg), a critical parameter in pharmaceutical science.

The Polymer Science of Stability: How Molecular Weight Governs Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) in Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the fundamental and applied relationship between molecular weight (Mw) and glass transition temperature (Tg), a critical parameter in pharmaceutical science. We explore the foundational theories, including free volume and kinetic models, that explain the logarithmic increase of Tg with Mw. The article details methodological approaches for measuring and manipulating Tg through Mw control in polymer excipients and amorphous solid dispersions. We address common formulation challenges, such as physical instability and crystallization, and provide optimization strategies. Finally, we compare Tg-Mw relationships across polymer classes and validate predictive models. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a actionable framework for designing stable amorphous drug products.

Understanding the Core Principle: Why Chain Length Determines Polymer Mobility and Tg

This technical guide defines three critical parameters in polymer and amorphous solid science—Molecular Weight (MW) averages, Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), and the Amorphous State—and frames them within the central research thesis: How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature? Understanding this relationship is paramount for researchers and pharmaceutical scientists designing stable amorphous solid dispersions, where Tg directly impacts physical stability, dissolution, and shelf-life.

Defining Molecular Weight Averages

For synthetic and natural polymers, molecular weight is not a single value but a distribution. Three primary averages are essential.

- Number-Average Molecular Weight (Mₙ): The total weight of all molecules divided by the total number of molecules. It is sensitive to the population of low-MW species.

- Formula: Mₙ = Σ(NᵢMᵢ) / ΣNᵢ

- Weight-Average Molecular Weight (Mw): The average molecular weight weighted by the mass of each molecule. It is more sensitive to the presence of high-MW species.

- Formula: Mw = Σ(NᵢMᵢ²) / Σ(NᵢMᵢ)

- Z-Average Molecular Weight (Mz): A higher-order average, emphasizing the very high-MW tail of the distribution.

- Formula: Mz = Σ(NᵢMᵢ³) / Σ(NᵢMᵢ²)

The ratio Mw/Mn defines the Polydispersity Index (PDI), a measure of the breadth of the MW distribution.

Table 1: Molecular Weight Averages and Their Sensitivities

| Average | Symbol | Measurement Method | Sensitivity | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number-Average | Mₙ | Osmometry, End-group analysis | Low-MW species | Relates to colligative properties (e.g., osmotic pressure) |

| Weight-Average | M_w | Static Light Scattering (SLS) | High-MW species | Relates to bulk properties (e.g., viscosity, Tg) |

| Z-Average | M_z | Sedimentation Equilibrium | Very High-MW species | Useful for characterizing extreme tails in distribution |

Defining the Amorphous State and Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

- Amorphous State: A solid state characterized by the absence of long-range molecular order (non-crystalline), where molecules are arranged randomly, akin to a frozen liquid. This state is metastable and possesses higher free energy than its crystalline counterpart, driving recrystallization.

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): The temperature range at which an amorphous material transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state upon heating. It is a kinetic transition, not a thermodynamic phase change like melting. Below Tg, molecular motions (segmental mobility) are severely restricted; above Tg, cooperative segmental motion begins.

The Fox-Flory Equation historically formalized the core thesis relationship for polymers: 1/Tg = 1/Tg,∞ - K / Mn where Tg,∞ is the Tg at infinite molecular weight and K is a constant. This establishes that Tg increases with M_n until reaching a plateau at high MW, as chain ends (which increase free volume and mobility) become less influential.

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Determining Tg via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Objective: Measure the Tg of an amorphous polymer or drug-polymer dispersion. Method:

- Sample Prep: Place 3-10 mg of sample in a sealed, pin-holed aluminum crucible.

- Equipment: Calibrate DSC for temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- Run 1 (Erase Thermal History): Heat from 25°C to ~T_g+50°C at 20°C/min. Hold for 3 min.

- Run 2 (Measurement): Cool rapidly to 25°C at 50°C/min. Reheat at a standard rate (10°C/min is common) through the Tg region to ~T_g+50°C. This second heating curve is used for analysis.

- Analysis: Tg is reported as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity (Cp) on the second heat, determined by half-height or inflection point analysis.

Protocol 2: Characterizing MW Distribution via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) Objective: Determine Mn, Mw, M_z, and PDI of a polymer. Method:

- System: Utilize a GPC system with refractive index (RI) and multi-angle light scattering (MALS) detectors.

- Columns: Use a series of polymeric columns with defined pore sizes for separation by hydrodynamic volume.

- Mobile Phase: Select an appropriate solvent (e.g., THF for many synthetic polymers, buffered aqueous for polysaccharides). Dissolve sample to ~1-5 mg/mL and filter (0.2 µm).

- Calibration: Use narrow-MW polystyrene standards (for THF) to create a retention time calibration curve, or employ the MALS detector for absolute MW determination without calibration.

- Analysis: Software integrates the chromatogram and, using calibration or MALS data, calculates Mn, Mw, M_z, and PDI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for MW-Tg Relationship Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary tool for measuring Tg. Detects heat capacity changes associated with the glass transition. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatograph (GPC/SEC) | The standard method for separating polymers by size and determining MW averages and distribution. |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) Detector | Coupled with GPC, provides absolute M_w without need for column calibration. |

| Amorphous Model Polymer (e.g., PVP, PVPVA, HPMCAS) | These polymers form stable amorphous matrices. Their well-characterized MW variants are used to establish MW-Tg trends. |

| Cryo-mill / Ball Mill | For generating amorphous solid dispersions or comminuting samples for analysis without inducing heat-based artifacts. |

| Hydration Control Setup (Desiccators, Saturated Salt Solutions) | Critical for controlling sample water content, as water is a potent plasticizer that drastically lowers Tg. |

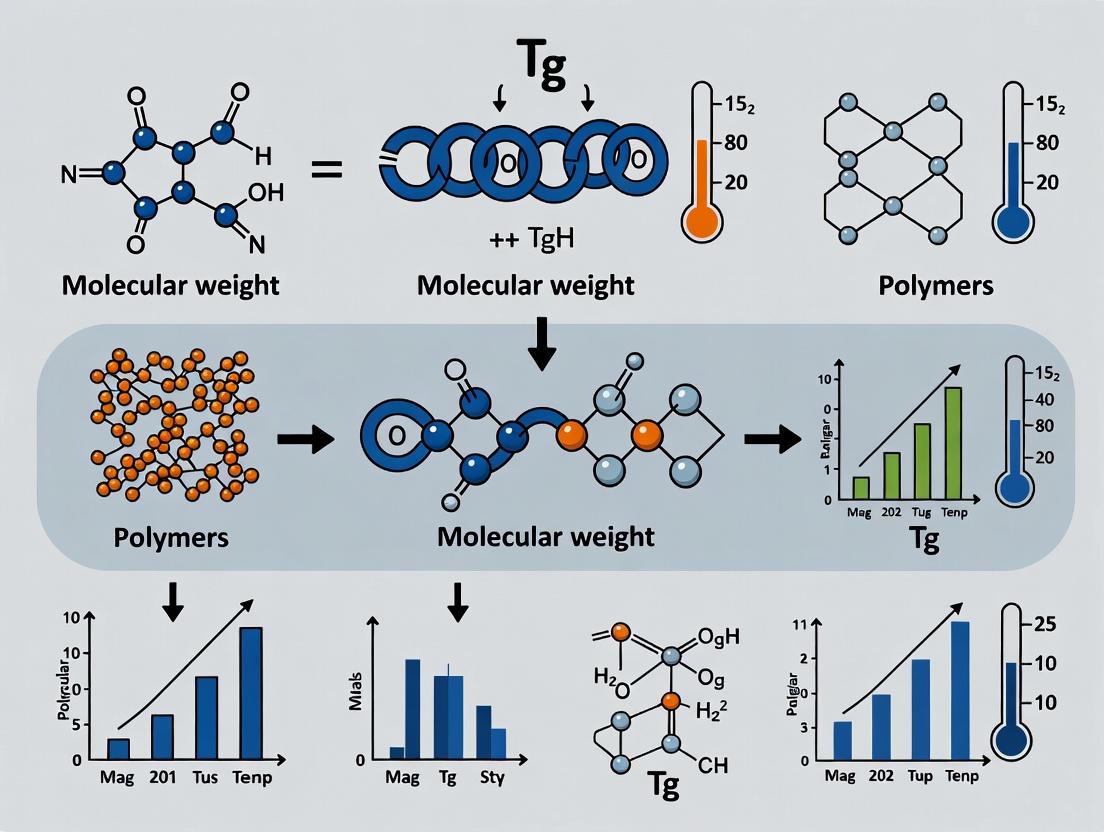

Visualizing Core Concepts and Workflows

Title: Molecular Weight Characterization and Tg Analysis Pathways

Title: MW Effect on Tg via Free Volume and Chain Ends

Framing within Molecular Weight and Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Research

The relationship between molecular weight (M) and the glass transition temperature (Tg) of amorphous polymers is a cornerstone of polymer physics. A fundamental model, derived from the Free Volume Theory, describes how Tg increases with M before plateauing at high molecular weights. This phenomenon is directly attributed to the increased concentration of chain ends in lower M polymers. Chain ends, possessing greater motional freedom and less efficient packing than mid-chain segments, introduce a disproportionate amount of "free volume." This article provides an in-depth technical guide to the core principles, experimental validation, and practical implications of this concept.

Core Theoretical Principles

The Free Volume Theory, significantly developed by Fox and Flory, posits that the glass transition occurs when the free volume (the unoccupied space between molecules) falls below a critical threshold. Chain ends are regions of disorder; their presence disrupts efficient packing of polymer chains, thereby increasing the average free volume per segment.

The quantitative relationship is given by the Fox-Flory equation:

Tg = Tg∞ - K / M

Where:

- Tg∞ is the glass transition temperature at infinite molecular weight (the plateau value).

- K is a constant related to the free volume contribution per chain end.

- M is the number-average molecular weight (Mn).

This linear inverse relationship between Tg and 1/Mn is a key prediction of the theory, with the slope K providing a direct measure of the free volume impact of chain ends.

Experimental Validation & Key Data

The Fox-Flory relationship is validated by synthesizing a series of monodisperse polymers (or carefully fractionated samples) and measuring their Tg as a function of Mn.

Table 1: Representative Tg vs. Mn Data for Polystyrene

| Number-Average Molecular Weight, Mn (g/mol) | 1/Mn (mol/g) x 10^5 | Glass Transition Temperature, Tg (°C) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3,000 | 33.33 | 60.5 | Fox & Flory, 1950 |

| 10,000 | 10.00 | 92.0 | Fox & Flory, 1950 |

| 50,000 | 2.00 | 98.5 | Fox & Flory, 1950 |

| 100,000 | 1.00 | 99.5 | Fox & Flory, 1950 |

| ∞ (plateau) | 0.00 | ~100 | Literature consensus |

Table 2: Fox-Flory Parameters for Common Polymers

| Polymer | Tg∞ (°C) | K (g·K/mol) | Key Experimental Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (atactic) | ~100 | ~1.0 x 10^5 | DSC, Dilatometry | Fox & Flory, JPS, 1950 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | ~105 | ~2.1 x 10^5 | DSC | Cowie & Toporowski, EJ Polymer, 1968 |

| Poly(vinyl acetate) | ~30 | ~3.7 x 10^5 | Dilatometry | Fox & Flory, JACS, 1948 |

| Poly(lactic acid) (PLLA) | ~58 | ~5.6 x 10^5 | DSC | Gualandi et al., Acta Biomaterialia, 2010 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Measuring Tg vs. Mn

Objective: To determine the Fox-Flory parameters (Tg∞ and K) for a given polymer system.

Materials & Reagents:

- Polymer Series: A set of 5-10 samples with well-characterized, monodisperse (PDI < 1.1) molecular weights covering a broad range (e.g., from 5 kDa to >100 kDa).

- Solvent (for film casting): High-purity, anhydrous solvent appropriate for the polymer (e.g., toluene for polystyrene, chloroform for PMMA).

- Reference Pan & Lid (for DSC): Hermetically sealed aluminum pans rated for the intended temperature range.

- Calibration Standards (for DSC): Indium, Zinc for temperature and enthalpy calibration.

Procedure:

Sample Preparation (Solution Casting):

- Dissolve each polymer sample in the chosen solvent at ~2-5% (w/v).

- Cast the solution onto a clean, level substrate (e.g., Teflon dish or glass slide) inside a controlled environment (e.g., dry box or fume hood).

- Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly over 24-48 hours, covered loosely to prevent dust contamination.

- Further dry the films under vacuum at a temperature 20-30°C above the solvent's boiling point for at least 24 hours to remove residual solvent. Confirm complete drying by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) if necessary.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Measurement:

- Calibrate the DSC instrument using high-purity indium (melting point: 156.6°C, ΔHf = 28.5 J/g).

- Precisely weigh (~5-10 mg) each dried film into a tared aluminum DSC pan. Crimp the pan with a lid to ensure good thermal contact and prevent solvent ingress/egress.

- Run a standard temperature ramp protocol (e.g., equilibrate at 0°C, heat to 150°C at 10°C/min, cool to 0°C at 20°C/min, then re-heat to 150°C at 10°C/min) under a nitrogen purge (50 mL/min).

- Analyze the second heating curve to avoid thermal history effects. Tg is typically taken as the midpoint of the heat capacity step change.

Data Analysis:

- Plot Tg (°C or K) against 1/Mn.

- Perform a linear regression on the data points. The y-intercept is Tg∞. The slope of the line is -K.

Critical Notes: Samples must be fully amorphous and dry. Residual solvent plasticizes the polymer, artificially lowering Tg and confounding results.

Visualizing the Core Concept

Molecular Weight vs. Chain End Concentration and Packing

Experimental Workflow for Fox-Flory Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Monodisperse Polymer Standards | Crucial for establishing the fundamental Tg-Mn relationship without confounding effects of broad molecular weight distribution (PDI). Commercial standards (e.g., for PS, PMMA) are available. |

| Anhydrous, Inhibitor-Free Solvents (e.g., Toluene, THF, Chloroform) | Used for sample purification, fractionation, and film casting. Anhydrous conditions prevent unwanted reactions. Inhibitor-free solvents ensure no low-Mw additives remain to affect Tg. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary instrument for measuring Tg. Must be properly calibrated for temperature and enthalpy. Modulated DSC (MDSC) can be useful for complex transitions. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)/GPC System | Equipped with multi-angle light scattering (MALS), refractive index (RI), and viscometry detectors for absolute molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and distribution (PDI) characterization. |

| High-Temperature Vacuum Oven | For complete removal of residual solvent and water from polymer films prior to Tg measurement, which is critical for accurate data. |

| Hermetic Sealing DSC Pans & Lids | Ensure no mass loss (e.g., residual solvent, plasticizer) occurs during the DSC run, which would create artifacts in the heat flow signal. |

| Inert Gas Supply (N₂ or Ar) | Provides an inert atmosphere during DSC runs to prevent oxidative degradation of the polymer at elevated temperatures. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) (Optional but recommended) | Used in tandem with DSC to confirm complete solvent removal from cast films and to determine polymer degradation temperatures. |

Implications for Drug Development & Material Science

In pharmaceutical science, the Tg of amorphous solid dispersions (a common formulation strategy for poorly soluble drugs) is a critical stability parameter. A low-Mw polymeric stabilizer (e.g., PVP, HPMCAS) will have a lower Tg than its high-Mw counterpart. According to Free Volume Theory, this formulation will have higher molecular mobility at storage temperature, potentially leading to faster drug recrystallization. Therefore, understanding and applying the Fox-Flory equation allows formulators to rationally select polymer molecular weight to optimize both processing (linked to viscosity) and long-term physical stability (linked to Tg and molecular mobility). This principle extends directly to the design of polymeric excipients, coatings, and biomedical devices where mechanical properties and dimensional stability are Tg-dependent.

This whitepaper details the kinetic perspective on the glass transition, framed within the critical thesis question: How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature (Tg)? The transition from a supercooled liquid to a rigid glass is governed by the dramatic slowdown of molecular motion as temperature decreases. This kinetic arrest is profoundly influenced by polymer chain architecture, specifically molecular weight (Mw), through two primary mechanisms: (i) the free volume effect at low Mw and (ii) the onset of chain entanglement and restricted center-of-mass motion at high Mw. Understanding the interplay between entanglement, segmental (local) motion, and the resultant macroscopic rigidity is paramount for material science and pharmaceutical development, where Tg dictates processing conditions and amorphous solid stability.

Theoretical Framework: Entanglement and Segmental Dynamics

Segmental motion, typically involving 10-20 backbone bonds, is the primary determinant of Tg. This motion requires cooperative rearrangement of neighboring segments and is intrinsically linked to free volume. At low molecular weights (below the critical entanglement molecular weight, Me), chain ends act as defects, increasing free volume and plasticizing the system. As Mw increases, the concentration of chain ends decreases, leading to a rise in Tg. Above Me, chains become physically entangled, forming a transient network. These topological constraints severely restrict long-range reptation but have a subtler, secondary effect on local segmental mobility. The plateau in Tg at high Mw signifies that segmental dynamics are now decoupled from the global chain diffusion, governed primarily by local intermolecular interactions and free volume, which become Mw-independent.

Key Quantitative Data and Relationships

The following tables summarize the core quantitative relationships governing Mw and Tg.

Table 1: Effect of Molecular Weight on Tg for Amorphous Polymers

| Polymer System | Critical Entanglement Mw (Me, g/mol) | Tg at Infinite Mw (Tg∞, °C) | Fox-Flory Equation Parameter (K, g·K/mol) | Empirical Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | ~18,000 | 100 | ~1.0 x 10^5 | Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mw |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | ~10,000 | 105-125 | ~2.0 x 10^5 | Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mw |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | ~7,000 | 85 | ~0.7 x 10^5 | Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mw |

| Pharmaceutical Polymer: PVP | ~6,000 | 175 | ~2.3 x 10^5 | Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mw |

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Probing Segmental Dynamics & Rigidity

| Technique | Measured Property | Characteristic Frequency/Timescale | Sensitivity to Mw below/above Me |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat Flow Change at Tg | 0.1 - 10 Hz (effective) | High sensitivity below Me; detects Tg plateau above Me. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Modulus (E', E'') & Tan δ | 0.1 - 100 Hz | Directly measures onset of rigidity; rubbery plateau modulus indicates entanglement density. |

| Dielectric Spectroscopy (DES) | Dielectric Loss (ε'') | 10^-3 - 10^9 Hz | Probes segmental (α-) relaxation; can detect constrained dynamics near entanglements. |

| Neutron Spin Echo (NSE) | Self-correlation Function | 10^-9 - 10^-12 s | Directly measures segmental and chain dynamics on nanometer scales. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Tg-Mw Relationship via DSC Objective: To measure the glass transition temperature of a polymer series with varying Mw and fit data to the Fox-Flory equation. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain or synthesize a homologous series of linear polymer with dispersity (Đ) < 1.2. Dry all samples thoroughly. For pharmaceuticals, prepare amorphous solid dispersions via quench cooling or spray drying.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate DSC cell temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards. Use nitrogen purge gas (50 mL/min).

- Measurement: Weigh 5-10 mg of sample into hermetic Tzero pans. Run a heat-cool-heat cycle: equilibrate at Tstart = Tg - 50°C, heat at 10°C/min to Tend = Tg + 50°C, cool at 20°C/min, then reheat at 10°C/min. The second heating curve is used for analysis.

- Data Analysis: Determine Tg as the midpoint of the heat capacity step change. Plot Tg vs. 1/Mw for the polymer series. Perform linear regression: Tg = Tg∞ - (K / Mw). The y-intercept is Tg∞, and the slope is the Fox-Flory constant K.

Protocol 2: Probing Entanglement Dynamics via DMA Objective: To characterize the viscoelastic plateau and determine the shear storage modulus (G') in the rubbery region as a function of Mw. Methodology:

- Sample Geometry: Mold or cast polymer into rectangular torsion bars or thin films for shear/ tension clamping.

- Frequency/Temperature Sweep: Perform a temperature ramp at fixed frequency (e.g., 1 Hz, 3°C/min) from Tg - 30°C to Tg + 80°C. Alternatively, perform multi-frequency isothermal steps near Tg.

- Data Analysis: Identify three regions: glassy plateau (high G'), dramatic drop at Tg (tan δ peak), and rubbery plateau (G' ~ constant). The magnitude of the rubbery plateau modulus GN^0 is related to entanglement density (νe) and Me by GN^0 = ρRT / Me, where ρ is density, R is gas constant, and T is absolute temperature in the plateau region.

Visualizations

Title: How Molecular Weight Drives Rigidity via Chain Ends and Entanglements

Title: Experimental Workflow for Tg-Mw-Entanglement Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tg-Mw Experiments

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Monodisperse Polymer Standards | Narrow Đ (<1.1) polymers (PS, PMMA) for establishing fundamental Tg-Mw-entanglement relationships. |

| Pharmaceutical Polymers (e.g., PVP, HPMCAS) | Model polymers for amorphous solid dispersion research; their Tg and drug-polymer interactions are Mw-dependent. |

| Hermetic DSC Pans & Lids | Ensure no mass loss or solvent escape during thermal analysis, critical for accurate Tg measurement. |

| Quencher (Liquid N2) | For rapid cooling of samples from melt to form amorphous glass, avoiding crystallization. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) | Instrument to apply oscillatory stress/strain and measure modulus (rigidity) and damping (tan δ) as functions of T and time. |

| Dielectric Spectroscopy Cell | Parallel plate cell for measuring dielectric permittivity and loss, probing dipolar segmental relaxations. |

| Molecular Sieves (3Å) | For drying organic solvents used in polymer purification or sample casting to remove plasticizing water. |

| Thermal Gravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | To verify sample dryness and thermal stability prior to DSC/DMA runs, preventing artifacts. |

This whitepaper examines the Fox-Flory equation as a foundational mathematical model describing the relationship between the glass transition temperature (Tg) and the molecular weight (Mw) of polymers. Framed within ongoing research into how molecular weight affects glass transition temperature, this guide provides a technical deep dive into its derivation, applicability, limitations, and contemporary experimental validation methods critical for researchers in polymer science and pharmaceutical development.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical physicochemical property defining the transition from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. In polymer science and amorphous solid dispersion formulation for drug delivery, Tg directly impacts stability, mechanical properties, and dissolution behavior. A core principle is that Tg increases with molecular weight, asymptotically approaching a limiting value (Tg∞) at high Mw. The Fox-Flory equation quantitatively describes this relationship.

Derivation and Mathematical Formalism

The Fox-Flory equation posits that the increase in Tg with Mw is due to a reduction in free volume contributed by chain ends, whose mobility is greater than that of internal chain segments.

The fundamental equation is: Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mn where:

- Tg is the glass transition temperature of the polymer sample (in K or °C).

- Tg∞ is the limiting glass transition temperature at infinite molecular weight.

- K is an empirical constant specific to the polymer system (in K·g/mol or °C·g/mol).

- Mn is the number-average molecular weight.

A related form for weight-average molecular weight (Mw) is often used, though the original derivation is based on Mn.

Experimental Validation and Key Data

Experimental validation involves synthesizing or obtaining a series of polymer fractions with narrow molecular weight distributions and precisely measuring their Tg (typically via Differential Scanning Calorimetry, DSC). A plot of Tg versus 1/Mn yields a straight line, with the y-intercept equal to Tg∞ and the slope equal to -K.

Table 1: Fox-Flory Parameters for Selected Polymers

| Polymer | Tg∞ (°C) | K (K·g/mol) | Mw Range (g/mol) Studied | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (atactic) | 100.0 | 1.8 x 10^5 | 2,000 - 500,000 | Model polymer, excipient matrix |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | 105.0 | 2.1 x 10^5 | 3,000 - 1,000,000 | Drug coating, biomedical devices |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) | 87.5 | 6.7 x 10^4 | 5,000 - 200,000 | Medical tubing, packaging |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA 50:50) | ~45.0* | Varies with LA:GA ratio* | 10,000 - 100,000 | Controlled release formulations |

| Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) | ~175.0* | 1.5 - 2.5 x 10^5* | 2,500 - 1,000,000 | Amorphous solid dispersion carrier |

Note: Values for biodegradable and pharmaceutical polymers are highly formulation-dependent and represent typical ranges from recent literature.

Table 2: Comparison of Tg Measurement Techniques for Fox-Flory Analysis

| Technique | Principle | Sample Prep | Key Advantage for Mw-Tg | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat flow difference vs. temperature | 3-10 mg sealed pan | Standard method, direct Tg measurement | Requires homogeneous, dry sample |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Viscoelastic modulus vs. temperature | Film or molded bar | Sensitive to subtle transitions | Sample geometry critical |

| Dielectric Analysis (DEA) | Dielectric permittivity vs. temperature | Film between electrodes | Probes molecular mobility directly | Data interpretation can be complex |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Determining Fox-Flory Parameters

Objective: To experimentally determine Tg∞ and K for a homopolymer series. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Polymer Fractionation & Characterization:

- Obtain or synthesize at least 5-7 polymer samples with narrow polydispersity (Đ < 1.2) spanning a wide Mw range (e.g., 5 kDa to 500 kDa).

- Precisely determine Mn and Mw for each fraction using Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with multi-angle light scattering (MALS) and refractive index (RI) detection. Calibrate using narrow Mw standards of the same polymer.

Glass Transition Measurement (by DSC):

- Weigh 5-10 mg of each polymer sample into a tared aluminum DSC pan. Hermetically seal the pan.

- Load into the DSC instrument. Run a method with the following segments: a. Equilibrate at 20°C below expected Tg. b. Heat at 10°C/min to 30°C above expected Tg (1st heating, to erase thermal history). c. Cool at 20°C/min back to start temperature. d. Heat again at 10°C/min (2nd heating) for analysis.

- Analyze the 2nd heating curve. Tg is taken as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity.

Data Analysis & Fitting:

- For each sample, plot the measured Tg (in Kelvin) against the inverse of its Mn (1/Mn).

- Perform a linear regression (y = mx + c) on the data points.

- The y-intercept (c) corresponds to Tg∞.

- The slope (m) corresponds to -K.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fox-Flory Experiments

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Narrow-Disperse Polymer Standards | Calibrants for SEC and reference materials for establishing baseline Fox-Flory curves. |

| SEC/MALS/RI System | The gold-standard suite for absolute molecular weight (Mw, Mn) and distribution (Đ) determination. |

| High-Purity DSC Calibration Standards (e.g., Indium, Tin) | Ensure temperature and enthalpy accuracy of the DSC instrument. |

| Hermetic DSC Pan & Lid (Aluminum/Tzero) | Provides an inert, sealed environment for sample during heating cycle, preventing moisture loss/degradation. |

| Inert Purge Gas (Nitrogen or Argon, 50 mL/min) | Prevents oxidative degradation of polymer samples during thermal analysis. |

| Molecular Sieves (3Å or 4Å) | Used to dry solvents for polymer synthesis/fractionation and to store hygroscopic polymer samples. |

Limitations and Modern Extensions

The classical Fox-Flory model assumes linear chains and neglects effects of branching, crosslinking, plasticization, and copolymer composition. Modern research extends it:

- Branched/Copolymers: Modified equations incorporate branching functionality or copolymer weight fractions.

- Polymer Blends & APIs: The Gordon-Taylor equation (and its Fox approximation) is often used in tandem to model Tg of polymer/drug mixtures, crucial for predicting stability of amorphous solid dispersions.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Used to computationally probe the free volume and chain-end mobility assumptions at the atomistic level.

Critical Pathways and Workflows

Title: Experimental Workflow for Fox-Flory Parameter Determination

Title: Logical Relationship from Theory to Application

The Fox-Flory equation remains an indispensable, simple yet powerful tool for understanding and predicting the Tg-Mw relationship. Within pharmaceutical development, it provides a foundational model for designing polymeric excipients with tailored thermal properties, thereby informing the stability and performance of drug products. Ongoing research integrates this classical model with more complex systems—such as copolymers, plasticized networks, and amorphous solid dispersions—ensuring its continued relevance in advanced materials and drug formulation science.

Understanding the relationship between molecular weight (MW) and the glass transition temperature (Tg) is fundamental to polymer science and the development of amorphous solid dispersions in pharmaceuticals. The broader thesis posits that Tg is not a simple linear function of MW but exhibits distinct regimes demarcated by critical thresholds. This article focuses on the Critical Molecular Weight (Mc), the pivotal point above which chain entanglements become pervasive, fundamentally altering rheological, mechanical, and thermal properties. Below Mc, properties are governed primarily by chain ends, which act as defects and increase free volume. Above Mc, the network of topological constraints (entanglements) dominates, leading to a plateau in properties like viscosity and modulus, and a markedly reduced dependence of Tg on further increases in MW.

Fundamental Principles

The Critical Molecular Weight is defined as the molecular weight at which polymer chains become long enough to form a stable, pervasive network of topological entanglements. This transition has profound implications:

- Below Mc: Tg increases linearly with MW. This is described by the Fox-Flory equation: 1/Tg = 1/Tg∞ - K/Mn, where Tg∞ is the Tg at infinite MW, K is a constant, and Mn is the number-average molecular weight. The free volume contributed by chain ends is significant.

- At Mc: The onset of entanglement-dominated behavior.

- Above Mc: Tg asymptotically approaches Tg∞. The zero-shear viscosity (η₀) scales with MW to the ~3.4 power (η₀ ∝ Mw^3.4), and the plateau modulus (GN⁰) becomes largely independent of MW.

Table 1: Critical Molecular Weight (Mc) and Related Parameters for Common Polymers

| Polymer | Mc (g/mol) | Tg∞ (°C) | K (g·K/mol) in Fox-Flory Eqn | Viscosity Exponent above Mc (η₀ ∝ Mw^α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (atactic) | ~31,000 | 100 | ~1.0 x 10^5 | 3.4 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | ~28,000 | 105 | ~1.5 x 10^5 | 3.4 |

| Poly(vinyl acetate) | ~25,000 | 32 | ~1.2 x 10^5 | 3.4-3.5 |

| Polyethylene (linear) | ~3,800 | -80 | ~2.0 x 10^5 | 3.4 |

| Poly(dimethylsiloxane) | ~24,500 | -125 | ~0.6 x 10^5 | 3.5 |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) | ~11,000 | 87 | ~0.7 x 10^5 | 3.7 |

Table 2: Property Regimes Relative to Mc

| Property | Regime Below Mc | Regime Above Mc |

|---|---|---|

| Tg Dependence | Strong inverse dependence on Mn (Fox-Flory). | Weak dependence, asymptotes to Tg∞. |

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) | η₀ ∝ Mw^1.0 (Rouse dynamics). | η₀ ∝ Mw^~3.4 (Reptation dynamics). |

| Melt Elasticity | Low, viscous flow dominates. | High, significant elastic recovery. |

| Mechanical Strength | Poor, brittle. | Good toughness and ductility. |

| Diffusion Coefficient | Higher, less restricted. | Significantly lower, restricted by mesh. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Mc

Protocol 4.1: Determining Mc via Rheology (Viscosity)

Objective: Measure zero-shear viscosity (η₀) across a series of narrowly dispersed polymer samples with varying Mw to identify the onset of the 3.4-power law.

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize or procure anionically polymerized samples with polydispersity index (Đ) < 1.1. Characterize Mw via Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC).

- Rheological Measurement: Using a rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry:

- Perform a strain sweep to identify the linear viscoelastic region.

- Perform a frequency sweep (e.g., 0.01 to 100 rad/s) at a temperature well above Tg (typically Tg + 50°C).

- Extract η₀ from the low-frequency plateau of the complex viscosity (η*) vs. angular frequency (ω) plot.

- Data Analysis: Plot log(η₀) vs. log(Mw). Fit two linear regressions—one for the low MW regime (slope ~1) and one for the high MW regime (slope ~3.4). The intersection point defines Mc.

Protocol 4.2: Determining Mc via Thermal Analysis (Tg)

Objective: Measure Tg for a series of low-MW oligomers/polymers to determine Tg∞ and Mc from the Fox-Flory relationship.

- Sample Preparation: Use the same series of narrow-dispersion samples. Ensure samples are thoroughly dried.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC):

- Heat/Cool/Heat protocol: First heat to erase thermal history, quench, then second heat for measurement.

- Use a moderate scan rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Tg is taken as the midpoint of the heat capacity transition on the second heating scan.

- Data Analysis: Plot 1/Tg (in Kelvin) vs. 1/Mn. Perform a linear fit. The y-intercept is 1/Tg∞. Extrapolate to find the MW where Tg reaches ~95-98% of Tg∞; this is operationally associated with Mc.

Visualizations

Title: Transition Between Polymer Property Regimes at Mc

Title: Experimental Workflow to Determine Critical Molecular Weight

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mc-Related Research

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Narrow-Dispersion Polymer Standards | Pre-characterized polymers with low Đ (≤1.1). Essential for establishing clean Mw-property relationships without polydispersity effects. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)/GPC System | Equipped with multi-angle light scattering (MALS) and refractive index (RI) detectors. Provides absolute molecular weight (Mw, Mn) and distribution (Đ). |

| Rotational Rheometer | Equipped with parallel plate or cone-and-plate geometry. Measures viscoelastic properties (η₀, G', G") to probe entanglement dynamics. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary tool for measuring the glass transition temperature (Tg) with high precision and sensitivity. |

| High-Purity Solvents (THF, TCB, DMF) | For SEC/GPC elution and sample preparation. Must be HPLC-grade and filtered/degassed to prevent column damage and spurious signals. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glove Box | For safe handling and preparation of moisture-sensitive or oxygen-sensitive polymer samples, especially for thermal analysis. |

| Dielectric Spectroscopy (DES) System | An alternative technique to probe segmental and chain dynamics across a wide frequency range, providing complementary data to rheology. |

Measuring and Manipulating Tg: Techniques and Strategies for Formulation Scientists

Within the context of researching how molecular weight (Mw) affects glass transition temperature (Tg), the selection of analytical technique is paramount. The Tg is a kinetic, non-equilibrium transition, and its measured value is intrinsically linked to the experimental method and timescale. This guide details three core techniques—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA), and Rheology—highlighting their principles, protocols, and unique sensitivities in elucidating the Mw-Tg relationship for polymeric materials and amorphous solid dispersions in pharmaceuticals.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC measures the heat flow difference between a sample and an inert reference as a function of temperature or time. The Tg is observed as a step change in heat capacity (ΔCp) in the thermogram.

Protocol for Tg Determination (Modulated DSC recommended):

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 5-10 mg of polymer or lyophilized API/polymer dispersion into a hermetic, Tzero aluminum pan. Seal the pan.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate for temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- Method Parameters:

- Equilibration: Hold at 20°C below expected Tg for 5 min.

- Temperature Ramp: Heat at 2-3°C/min to 30°C above expected Tg.

- Modulation (if using MDSC): Apply a sinusoidal modulation (e.g., ±0.5°C every 60 seconds) to deconvolute reversible (heat capacity) and non-reversible (enthalpic relaxation) events.

- Atmosphere: Purge with dry N₂ at 50 mL/min.

- Data Analysis: Tg is typically reported as the midpoint of the step transition in the reversing heat flow signal (MDSC) or heat flow signal (standard DSC). Onset and endpoint temperatures are also noted.

Sensitivity to Molecular Weight: DSC is highly effective for measuring the calorimetric Tg. For polymers, it directly validates the Fox-Flory relationship, where Tg increases with Mw up to a critical value, after which it plateaus. Lower Mw samples may show broader transitions and greater enthalpy relaxation peaks.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Principle: DMA applies a small sinusoidal stress (or strain) to a sample and measures the resultant strain (or stress). It quantifies the storage modulus (E' or G', elastic response), loss modulus (E'' or G'', viscous response), and tan delta (E''/E' or G''/G'). Tg is identified from peaks in E'' or tan delta.

Protocol for Tg Determination (Film/Tensile or Shear Mode):

- Sample Preparation: Prepare free-standing films of uniform thickness (0.1-1 mm) via solvent casting or compression molding. For solids, use single or dual cantilever bending clamps.

- Mounting: Secure the sample in the appropriate clamp (tension, shear, bending) ensuring good contact and uniform stress distribution.

- Method Parameters:

- Strain Amplitude: Conduct a strain sweep first to ensure measurements are within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

- Frequency: A fixed frequency of 1 Hz is standard for temperature ramps.

- Temperature Ramp: Heat at 2-3°C/min over a range spanning the glassy and rubbery states.

- Static Force: Apply a small static force to maintain sample tension.

- Data Analysis: Identify Tg from:

- Peak of Loss Modulus (E''): Often considered the most accurate reflection of the mechanical transition.

- Peak of tan delta (δ): Provides a higher signal-to-noise ratio but is frequency-dependent and occurs at a slightly higher temperature than the E'' peak.

Sensitivity to Molecular Weight: DMA is exceptionally sensitive to the onset of large-scale chain motions at Tg. It can detect subtle changes in the relaxation spectrum related to Mw distribution and chain entanglements. The plateau modulus in the rubbery region is directly related to the crosslink or entanglement density.

Rheology

Principle: Rotational rheometry, in oscillatory mode, measures the viscoelastic properties (G', G'', complex viscosity) of materials, often in the molten or soft solid state. Tg is determined from a dramatic drop in viscosity or a crossover in G' and G'' during a temperature ramp.

Protocol for Tg Determination (Oscillatory Temperature Ramp):

- Sample Preparation: For polymers or amorphous dispersions, load solid/semi-solid material onto the Peltier plate. Use parallel plate geometry (e.g., 8-20 mm diameter) with a defined gap (0.5-1.5 mm).

- Tool Conditioning: Trim excess material and apply a normal force to ensure good contact and eliminate air gaps. Allow temperature equilibration.

- Method Parameters:

- Strain/Stress Amplitude: Confirm measurement is within LVR via an amplitude sweep.

- Angular Frequency: Set to a constant value (e.g., 10 rad/s).

- Temperature Ramp: Heat at 2-3°C/min.

- Gap Auto-compensation: Enable to account for thermal expansion.

- Data Analysis: Identify the glass transition region by:

- Sharp decrease in complex viscosity (η*).

- Crossover of G' and G'' (where G' = G''), indicating a transition from solid-like to liquid-like behavior.

- Peak in tan δ (G''/G').

Sensitivity to Molecular Weight: Rheology is crucial for understanding processing. It directly measures viscosity (η), which scales with Mw to the 3.4 power above the entanglement Mw (Mᵉ). The temperature dependence of viscosity near Tg is described by the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation, parameters of which vary with Mw.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Tg Determination Methods

| Parameter | DSC | DMA | Rheology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measured Property | Heat Capacity (Cp) | Modulus (E, G) & Damping (tan δ) | Modulus (G) & Viscosity (η) |

| Typical Tg Identifier | Midpoint of ΔCp step | Peak of E'' or tan δ | Viscosity drop or G'/G'' crossover |

| Sample Form | Small solid (mg) | Film, bar, fiber | Melt, paste, soft solid |

| Information on Mw | Calorimetric Tg, breadth of transition | Segmental mobility, sub-Tg relaxations, entanglement effects | Zero-shear viscosity (η₀), flow activation energy |

| Key Mw Relationship | Fox-Flory (Tg vs. 1/Mn) | Shift in tan δ peak position & breadth with Mw distribution | η₀ ∝ Mw^3.4 (for Mw > Mᵉ) |

Table 2: Illustrative Experimental Data for Polystyrene (PS) of Different Mw

| PS Mw (kDa) | DSC Tg (°C) | DMA Tan δ Peak (°C) | Rheology G'/G'' Crossover (°C) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | ~95 | ~102 | ~108 | Low Mw, broad transition, high chain end concentration. |

| 50 | ~100 | ~106 | ~113 | Approaching entanglement Mw (Me ~35 kDa for PS). |

| 200 | ~105 | ~110 | ~118 | Entangled, plateau in Tg vs. Mw relationship evident. |

| 1000 | ~105 | ~110 | ~118 | High Mw, Tg independent of further increases. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials & Reagents for Tg Studies

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Hermetic Tzero DSC Pans & Lids | Ensure an inert, sealed environment to prevent sample degradation, oxidation, or moisture loss during heating. |

| Indium & Zinc Calibration Standards | High-purity metals with sharp, known melting points and enthalpies for accurate temperature and heat flow calibration of DSC. |

| Quartz or Alumina DMA Calibration Standards | Materials with known modulus and thermal expansion for verifying DMA clamp stiffness and temperature accuracy. |

| Silicone Oil or Grease (High-Temp) | Applied to DMA clamps/samples to ensure good thermal contact and prevent sample slippage. |

| Parallel Plate or Cone-Plate Geometries (Steel) | Standard tools for rheological analysis of polymer melts; steel ensures rigidity and good temperature conduction. |

| Solvents for Film Casting (e.g., CHCl₃, THF, DCM) | High-purity solvents for preparing homogeneous polymer films of controlled thickness for DMA testing. |

| Inert Gas Supply (N₂ or Ar) | Essential purge gas for all instruments to prevent thermal-oxidative degradation of samples during experiments. |

| Standard Reference Polymers (e.g., PS, PMMA) | Well-characterized polymers with known Tg and Mw used for method validation and cross-technique comparison. |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

Title: Integrated Tg Analysis Workflow Across Techniques

Title: Molecular Weight Impact on Tg and Material Properties

This technical guide details polymerization techniques for precise control over molecular weight (Mw) and dispersity (Đ), a critical capability for systematic studies within the broader thesis: "How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature (Tg)?" The relationship between Mw and Tg is a fundamental tenet of polymer physics. According to the Flory-Fox equation, Tg increases with Mw up to a critical point, after which it plateaus. Precise synthesis of polymers with defined Mw and narrow Đ is therefore essential to isolate and quantify the effect of Mw on Tg, disentangling it from the effects of compositional heterogeneity, branching, or broad molecular weight distributions.

Core Polymerization Techniques: Mechanisms and Control

The choice of polymerization mechanism dictates the level of control over Mw and Đ. The following table summarizes key techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Polymerization Techniques for Mw and Đ Control

| Technique | Mechanism | Control Over Mw | Typical Đ Range | Key Control Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Radical Polymerization (FRP) | Chain-growth, non-living | Low (kinetic control) | 1.5 - 2.5 (often >2.0) | Initiator concentration, monomer conversion, temperature. |

| Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) | Chain-growth, living | High | 1.05 - 1.20 | [Monomer]:[RAFT Agent]:[Initiator] ratio, conversion. |

| Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) | Chain-growth, living | High | 1.05 - 1.20 | [Monomer]:[Initiator]:[Catalyst]:[Ligand] ratio. |

| Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization (NMP) | Chain-growth, living | High | 1.10 - 1.30 | [Monomer]:[Alkoxyamine] ratio, temperature. |

| Ring-Opening Polymerization (ROP) | Step-growth or chain-growth, often living | High | 1.05 - 1.20 | [Monomer]:[Initiator] ratio, catalyst choice, time. |

| Anionic Polymerization | Chain-growth, living | Very High | 1.01 - 1.10 | Purity (exclude protic impurities), solvent, temperature. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Synthesis of Polystyrene with Targeted Mw via RAFT Polymerization Objective: Synthesize polystyrene with a target Mn of 20,000 g/mol and Đ < 1.2. Materials: Styrene (monomer), 2-Cyano-2-propyl benzodithioate (CPDB, RAFT agent), Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, initiator), Toluene (solvent). Procedure:

- Purification: Pass styrene through a basic alumina column to remove inhibitor. Recrystallize AIBN from methanol.

- Charge Reactor: In a Schlenk flask, combine styrene (10.4 g, 100 mmol), CPDB (0.135 g, 0.5 mmol), AIBN (0.0164 g, 0.1 mmol), and toluene (10 mL). The [M]:[RAFT]:[I] ratio is 200:1:0.2.

- Degassing: Seal the flask and perform three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove oxygen.

- Polymerization: Place the flask in an oil bath at 70°C with stirring. Monitor conversion by 1H NMR.

- Termination: After reaching >95% conversion (~6-8 hours), cool the flask in ice water. Expose to air to quench the reaction.

- Purification: Precipitate the polymer into cold methanol, collect by filtration, and dry in vacuo. Characterization: Analyze by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to determine Mn and Đ.

Protocol B: Synthesis of Poly(methyl methacrylate) with Targeted Mw via ATRP Objective: Synthesize PMMA with a target Mn of 50,000 g/mol and Đ < 1.2. Materials: Methyl methacrylate (MMA, monomer), Ethyl α-bromoisobutyrate (EBiB, initiator), Copper(I) bromide (CuBr, catalyst), N,N,N',N'',N''-Pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA, ligand), Anisole (solvent). Procedure:

- Purification: Pass MMA through a basic alumina column. Purify anisole by standard methods.

- Charge Reactor: In a Schlenk flask, add CuBr (0.0143 g, 0.1 mmol) and a stir bar. Seal and flush with N2. Degas MMA (10.0 g, 100 mmol), anisole (10 mL), PMDETA (0.0209 g, 0.12 mmol), and EBiB (0.0147 g, 0.075 mmol) separately by sparging with N2.

- Initiation: Using syringes, transfer the degassed liquids to the flask under N2 flow. The [M]:[I]:[Cu]:[L] ratio is ~1333:1:1.33:1.6.

- Polymerization: Stir the reaction at 60°C. Monitor kinetics by sampling aliquots.

- Termination: After reaching desired conversion, open flask to air and dilute with THF. Pass through a neutral alumina column to remove copper catalyst.

- Purification: Precipitate into hexane, collect, and dry in vacuo. Characterization: Analyze by SEC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Controlled Polymerization

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Living Polymerization Initiators (e.g., Alkoxyamines for NMP, Alkyl halides for ATRP, Organolithiums for Anionic) | Defines the starting chain end. The [Monomer]:[Initiator] ratio directly determines target Mn. Must be highly pure. |

| Chain Transfer Agents (CTAs) (e.g., Trithiocarbonates for RAFT) | Mediates equilibrium between active and dormant chains, enabling controlled growth and narrow Đ. Structure dictates control and rate. |

| Transition Metal Catalysts with Ligands (e.g., CuBr/PMDETA for ATRP) | Catalyzes reversible halogen atom transfer in ATRP. Ligand choice modulates catalyst activity and solubility. |

| Ultra-Pure, Anhydrous Monomers & Solvents | Essential for living polymerizations (especially anionic). Impurities (water, protic agents) cause chain transfer or termination, broadening Đ. |

| Degassing Equipment/Agents (Schlenk line, Freeze-Pump-Thaw, N2 sparge, Copper(I) wire) | Oxygen is a potent radical scavenger that inhibits/retards radical polymerizations (RAFT, ATRP, FRP). Removal is critical. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC/GPC) System | The primary analytical tool for measuring absolute Mn, Mw, and Đ. Requires appropriate calibration standards. |

Visualization of Techniques and Workflow

Diagram Title: Decision Logic for Polymerization Technique Selection

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow from Synthesis to Tg Analysis

Introduction The stability and performance of an Amorphous Solid Dispersion (ASD) are critically dependent on its glass transition temperature (Tg). A higher Tg relative to storage temperature reduces molecular mobility, inhibiting drug crystallization and enhancing physical stability. This guide, framed within the thesis "How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature research," provides a technical framework for designing ASDs with an optimized Tg by leveraging polymer science principles and experimental data. The core tenet is that the molecular weight (MW) of the polymeric carrier directly influences the Tg of the final ASD, which follows the Gordon-Taylor and Fox equations for polymer blends.

1. The Molecular Weight-Tg Relationship: Core Principles

For a pure polymer, the Tg increases with molecular weight up to a critical value, following the Flory-Fox equation:

1/Tg = 1/Tg(∞) - K / M_n

where Tg(∞) is the Tg at infinite molecular weight, K is a constant, and Mn is the number-average molecular weight. In an ASD, the drug acts as a plasticizer (lowering Tg) or antiplasticizer (raising Tg). The effective Tg of the binary mixture is governed by the Gordon-Taylor equation:

Tg(mix) = (w1 * Tg1 + K_GT * w2 * Tg2) / (w1 + K_GT * w2)

where w is weight fraction, and KGT is a fitting parameter often estimated as ρ1Δα2 / ρ2Δα1 (density and change in thermal expansion coefficient).

Table 1: Impact of Polymer MW and Drug Loading on ASD Tg

| Polymer Carrier | M_w (kDa) | Drug (Loading) | Measured Tg (°C) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP VA64 | ~50 | Itraconazole (30%) | ~95 | 2023 |

| HPMCAS-L | ~80 | Felodipine (25%) | ~120 | 2022 |

| PVP K12 (Low MW) | ~4 | Celecoxib (20%) | ~70 | 2023 |

| PVP K90 (High MW) | ~1,200 | Celecoxib (20%) | ~105 | 2023 |

| Soluplus | ~90 | Naproxen (30%) | ~75 | 2024 |

2. Experimental Protocols for Tg Determination and ASD Fabrication Protocol 2.1: Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) for ASD Preparation

- Preparation: Pre-blend the API and polymer carrier at the desired weight ratio (e.g., 20:80) using a turbula mixer for 15 minutes.

- Extrusion: Feed the blend into a twin-screw extruder (e.g., 11-mm co-rotating). Set temperature profile based on the polymer's Tg and degradation temperature (typically 10-30°C above polymer Tg). Screw speed: 100-200 rpm.

- Collection & Processing: Collect the extrudate, cool, and mill into a fine powder using a cryogenic mill. Store in a desiccator until analysis.

Protocol 2.2: Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (mDSC) for Tg Measurement

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 5-10 mg of ASD powder into a T-zero aluminum pan. Hermetically seal.

- mDSC Parameters: Use a calibrated mDSC. Equilibrate at 0°C. Ramp at 2°C/min to 150°C with a modulation amplitude of ±0.5°C every 60 seconds under N2 purge (50 ml/min).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the reversible heat flow signal. The Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step-change in heat capacity. Ensure absence of melting endotherms to confirm amorphous state.

3. Diagram: Workflow for Designing ASDs with Optimal Tg

Title: ASD Optimization Workflow Based on Tg

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for ASD Development

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) K12, K29/32, K90 | Polymer carriers with varying Mw (4-1,200 kDa) to study Mw-Tg relationship. |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Acetate Succinate (HPMCAS) | pH-dependent polymer, common for spray-dried ASDs. Tg varies with grade (L/M/H). |

| Soluplus (PVA-PEG graft copolymer) | Amphiphilic carrier for melt extrusion. Has a moderate inherent Tg (~70°C). |

| Itraconazole / Celecoxib | Model BCS Class II drugs with low solubility, commonly used in ASD research. |

| Modulated DSC (mDSC) | Critical instrument for accurate Tg measurement, separates reversible (Tg) from non-reversible events. |

| Twin-Screw Hot-Melt Extruder | Standard equipment for continuous manufacturing of ASDs, allows precise temperature control. |

| Cryogenic Mill | For pulverizing extrudates without inducing crystallization or heat degradation. |

| Hermetic T-zero DSC Pans | Ensures no moisture loss during Tg measurement, which can artifactually shift Tg. |

5. Advanced Design: Ternary Systems and Kinetic Stability For drugs that severely plasticize the polymer (resulting in too low a Tg), consider ternary systems:

- Add a third, high-Tg component: e.g., a second polymer or mesoporous silica.

- Use drug-polymer salt/complex: Increases interaction strength, often elevating Tg.

Stability is kinetically controlled by the difference between storage temperature (T) and Tg (T - Tg). For long-term stability, aim for

Tg - T > 50°C(the "50°C rule of thumb").

Conclusion

Designing ASDs with an optimal Tg is a deliberate exercise in applying polymer physics, where the molecular weight of the carrier is a key tunable parameter. By systematically selecting high M_w polymers, accurately measuring the blend Tg via mDSC, and ensuring a sufficient Tg - T margin, researchers can significantly enhance the physical stability of amorphous formulations, directly validating the central thesis on molecular weight's pivotal role in Tg modulation.

While the foundational relationship between molecular weight (Mw) and glass transition temperature (Tg) is a cornerstone of polymer and amorphous solid science, this whitepaper explores critical modifiers that exert influence beyond Mw control. Plasticizers and anti-plasticizers are essential tools for fine-tuning material properties, particularly in pharmaceutical formulation and polymer engineering. This guide provides a technical examination of their mechanisms, experimental characterization, and practical application within the broader research context of molecular weight effects on Tg.

The Fox-Flory equation, Tg = Tg∞ - K/Mn, describes the increase in Tg with increasing molecular weight until a plateau (Tg∞) is reached. This relationship is fundamental for polymers and amorphous APIs. However, formulators often need to adjust Tg without altering the primary polymer or API chain length. This is where low molecular weight additives—plasticizers and anti-plasticizers—become indispensable. They modify free volume and molecular mobility, thereby shifting Tg predictably.

Mechanisms of Action

Plasticizers

Plasticizers are small molecules that intercalate between polymer chains, increasing interchain distance and free volume. This reduces the intensity of intermolecular forces (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals), leading to enhanced segmental mobility and a decrease in Tg.

Primary Mechanism: Dilution of polymer-polymer contacts and increase in free volume.

Anti-plasticizers

Less common, anti-plasticizers are small, rigid molecules that can increase Tg or create a sub-Tg transition. They restrict large-scale segmental motion by occupying free volume in a specific, restrictive manner or by forming strong transient bonds with the polymer, reducing overall chain mobility.

Primary Mechanism: Specific interactions and restrictive occupation of free volume, limiting cooperative motion.

Quantitative Data and Effects

Table 1: Comparative Effects of Common Additives on Tg of Polyvinyl Acetate (PVAc)

| Additive (20 wt%) | Type | Tg of Pure Additive (°C) | ΔTg of PVAc Blend (°C) | Primary Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethyl phthalate | Plasticizer | -65 | -25 | Dipole-Dilution |

| Glycerol | Anti-plasticizer | -93 | +5 | Hydrogen Bonding |

| Triacetin | Plasticizer | -78 | -18 | Weakened Cohesion |

| Sorbitol | Anti-plasticizer | -5 | +15* | Strong H-Bond Network |

Data is representative; values vary with concentration and system. Current research highlights the concentration-dependent duality of some additives like water.

Table 2: Impact of Glycerol (Plasticizer/Anti-plasticizer) on Tg of Amorphous Sucrose

| Glycerol Concentration (wt%) | Observed Tg (°C) | ΔTg from Pure Sucrose (°C) | Dominant Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 70 | 0 | Baseline |

| 5 | 55 | -15 | Plasticizer |

| 10 | 45 | -25 | Plasticizer |

| 20 | 35 | -35 | Plasticizer |

| 30 | 40 | -30 | Anti-plasticizer* |

At high concentrations, glycerol can form its own hydrogen-bonded network, restricting sucrose mobility.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol: Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (mDSC) for Tg Measurement

Objective: To accurately measure the Tg of polymer/additive blends.

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh polymer and additive using a microbalance to prepare blends (e.g., 95/5, 90/10, 80/20 w/w). Use solvent casting or melt quenching to create homogeneous amorphous films. Dry thoroughly under vacuum.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate mDSC for heat flow and temperature using indium and sapphire standards.

- Experiment Setup: Seal 5-10 mg of sample in a Tzero pan. Use an empty Tzero pan as reference.

- Method Parameters:

- Temperature Ramp: 2°C/min.

- Modulation: ±0.5°C every 60 seconds.

- Temperature Range: Typically from 50°C below to 50°C above expected Tg.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the reversible heat flow signal. Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity.

Protocol: Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) for Viscoelastic Transitions

Objective: To probe the mechanical manifestation of Tg and sub-Tg relaxations.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare rectangular films of blend (typical dimensions: 10mm x 5mm x 0.5mm).

- Clamping: Mount sample in tensile or film clamp. Ensure uniform tension.

- Method Parameters:

- Frequency: 1 Hz (fixed frequency recommended for Tg scan).

- Strain: Set within linear viscoelastic region (determined by prior strain sweep).

- Temperature Ramp: 3°C/min.

- Range: From below sub-Tg to above Tg.

- Data Analysis: Identify Tg from the peak in the loss modulus (E'' or tan δ) curve. Anti-plasticizer effects may appear as a secondary, sub-ambient peak.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Title: Mechanism of Plasticizer vs Anti-plasticizer Action

Title: Tg Modification Study Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Tg Modification Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Modulated DSC (mDSC) | Gold standard for precise Tg measurement. Separation of reversible (Cp) and non-reversible events is critical for complex blends. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) | Measures mechanical Tg and sub-Tg relaxations. Essential for detecting anti-plasticization effects on modulus. |

| High-Purity Polymer Standards (e.g., PVAc, PVP, PVPVA) | Well-characterized model polymers for controlled studies of additive effects. |

| Common Plasticizers (e.g., Diethyl phthalate, Triacetin, PEG 400) | Small molecules with known Tg-lowering effects. Used as positive controls and model compounds. |

| Common Anti-plasticizers (e.g., Glycerol, Sorbitol, Citric Acid) | Small, polyfunctional molecules capable of increasing Tg or creating beta transitions. |

| Humidity-Controlled Vacuum Oven | For reproducible drying of hygroscopic samples (e.g., polymers, sugars) prior to analysis. |

| Tzero Hermetic DSC Pans | Minimizes mass loss during mDSC runs, crucial for volatile additives. |

| FTIR Spectrometer with ATR | Probes specific molecular interactions (e.g., H-bonding shifts) between polymer and additive. |

| Dielectric Spectrometer (DES) | Investigates molecular mobility and relaxation times over a broad frequency range. |

Understanding the role of plasticizers and anti-plasticizers is not separate from Mw-Tg research but an essential extension of it. Effective formulation requires a dual-track approach: controlling the primary Mw of the backbone polymer or API, and then fine-tuning the Tg and material performance through selective additive use. Future research focuses on predictive modeling of these effects and exploring novel, multi-functional additives that can target specific intermolecular interactions to achieve desired stability and processing profiles.

This whitepaper presents a detailed case study on utilizing high glass transition temperature (Tg) polymers to formulate poorly soluble and unstable active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). The core scientific principle underpinning this approach is the relationship between a polymer's molecular weight (MW) and its Tg, a cornerstone of polymer physics. A broader thesis investigating "How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature?" provides the essential framework. According to the Flory-Fox equation, Tg increases with molecular weight up to a critical point, after which it plateaus. For drug formulation, this is critical: a polymer with a sufficiently high Tg can create a rigid, amorphous solid dispersion, immobilizing API molecules above the storage temperature, thereby inhibiting recrystallization (enhancing stability) and maintaining supersaturation (enhancing solubility).

Theoretical Foundation: Molecular Weight and Tg

The Flory-Fox equation describes the fundamental relationship: $$Tg = T{g,\infty} - \frac{K}{Mn}$$ where (Tg) is the glass transition temperature, (T{g,\infty}) is the Tg at infinite molecular weight, (K) is a constant related to free volume, and (Mn) is the number-average molecular weight.

Table 1: Effect of Molecular Weight on Tg for Common Pharmaceutical Polymers

| Polymer | Mw (kDa) | Tg (°C) | Tg∞ (Literature, °C) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-VA64 | ~65 | 101-107 | ~130 | Solubility enhancement |

| HPMCAS-LF | ~90 | 110-120 | ~125 | Enteric, amorphous dispersion |

| Soluplus | ~118 | ~70 | ~90 (est.) | Melt extrusion, solubility |

| PVP K30 | ~50 | 160-170 | ~180 | Spray drying, binding |

| Eudragit L100 | ~135 | ~150 | ~160 (est.) | Enteric coating |

Data compiled from recent vendor specifications and research publications (2023-2024).

Experimental Protocol: Formulating a High-Tg Solid Dispersion

This protocol details the preparation and characterization of an amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) using a high-Tg polymer to enhance the solubility and stability of a model BCS Class II API (e.g., Itraconazole).

Materials and Preparation via Spray Drying

- API: Itraconazole (Poorly water-soluble model drug).

- Polymer: HPMCAS-LF (Tg ~115°C). Selected for its high Tg and ability to maintain supersaturation.

- Solvent: Acetone/Water mixture (85/15 v/v).

- Procedure:

- Dissolve Itraconazole and HPMCAS-LF at a 20:80 (w/w) drug-to-polymer ratio in the solvent system to achieve 2% (w/v) total solid concentration.

- Stir magnetically for 6 hours until a clear solution is obtained.

- Spray dry using a Buchi B-290 Mini Spray Dryer with the following parameters: Inlet temperature: 85°C, Outlet temperature: 50-55°C, Aspirator flow: 35 m³/h, Pump rate: 3 mL/min, Nozzle diameter: 0.7 mm.

- Collect the dry powder in a collection vessel and store in a desiccator over silica gel.

Critical Characterization Methods

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Confirm amorphous state and measure Tg.

- Protocol: Seal 3-5 mg of sample in a Tzero aluminum pan. Run a heat-cool-heat cycle from 0°C to 200°C at 10°C/min under N2 purge (50 mL/min). The absence of a crystalline melting endotherm and the presence of a single Tg > storage temperature indicates successful ASD formation.

- Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD): Verify lack of crystallinity.

- In Vitro Dissolution Testing:

- Protocol: Use USP Apparatus II (paddles) at 75 rpm in 900 mL of 0.01N HCl at 37°C. Introduce a sample equivalent to 50 mg of API. Withdraw samples at 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes, filter (0.45 µm), and analyze by HPLC-UV. Compare to unformulated crystalline API.

- Stability Study:

- Protocol: Store ASD powder in open glass vials under accelerated conditions (40°C/75% RH) for 1 month. Analyze samples at 0, 2, and 4 weeks by DSC and PXRD to monitor for Tg depression and physical instability (recrystallization).

Diagram Title: Workflow for Developing High-Tg Polymer ASD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for High-Tg ASD Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| High-Tg Polymers | Matrix former to create rigid amorphous phase, inhibit molecular mobility. | HPMCAS (AQOAT), PVP-VA (Kollidon VA64), Eudragit polymers |

| Spray Dryer | Key equipment for producing ASD powders via rapid solvent evaporation. | Buchi B-290/295, Yamato ADL311 |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures Tg, confirms amorphous state, and assesses miscibility. | TA Instruments Q20, Mettler Toledo DSC 3 |

| Dynamic Vapor Sorption (DVS) | Quantifies moisture uptake, which can plasticize the polymer and lower Tg. | Surface Measurement Systems DVS Intrinsic, TA Instruments Vapor Sorption Analyzer |

| Powder X-Ray Diffractometer (PXRD) | Provides definitive crystallinity/amorphicity analysis. | Rigaku MiniFlex, Bruker D8 Discover |

| Dissolution Tester | Evaluates drug release profiles and supersaturation maintenance. | Distek 2500, Agilent 708-DS |

| HPLC with UV/PDA Detector | Quantifies drug concentration in dissolution and stability samples. | Agilent 1260 Infinity II, Waters Alliance e2695 |

Results and Discussion

Table 3: Representative Experimental Data for Itraconazole-HPMCAS ASD

| Formulation | Tg (DSC, °C) | Crystalline Content (PXRD) | Dissolution @ 120 min (%) | Crystallinity after 1 mo @ 40°C/75% RH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystalline API | N/A (M.P. ~166°C) | High | 2.5 ± 0.8% | N/A |

| HPMCAS ASD | 78.5 ± 1.2 | Amorphous | 85.4 ± 3.1% | None detected |

Data is illustrative of typical results. The ~37°C gap between the ASD's Tg (78.5°C) and storage temperature (40°C) provides a significant kinetic barrier to molecular rearrangement, explaining the excellent physical stability.

The stability is governed by the difference between the storage temperature (T) and the formulation's Tg. The higher the (Tg - T), the lower the molecular mobility, as predicted by the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation. A high-Tg polymer directly contributes to a larger (Tg - T), slowing diffusion and nucleation rates exponentially.

Diagram Title: Stability Logic Chain: Mw to Tg to Stability

This case study demonstrates that the strategic selection of high-Tg polymers, whose properties are intrinsically linked to their molecular weight, is a powerful method for enhancing the solubility and stability of challenging APIs. The experimental data confirm that a sufficiently high Tg, relative to storage conditions, is a reliable predictor of long-term amorphous solid dispersion stability. This work validates the core thesis that understanding and manipulating the polymer MW-Tg relationship is fundamental to rational formulation design in advanced drug delivery.

Solving Stability Challenges: From Crystallization to Phase Separation in Low-Tg Systems

1. Introduction Within the critical research framework of How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature, a fundamental relationship emerges: the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an amorphous solid is intrinsically linked to its molecular weight (Mw). At low molecular weights, Tg increases with Mw according to the Flory-Fox equation. This relationship has profound implications for the physical stability of amorphous pharmaceutical dispersions, where low Mw and a consequently low Tg create a high-risk scenario for crystallization, phase separation, and chemical degradation. This guide details the mechanisms of this instability and provides methodologies for its identification and mitigation.

2. Core Principles: The Mw-Tg-Stability Relationship The glass transition temperature (Tg) is the temperature at which an amorphous material transitions from a brittle glassy state to a viscous rubbery state. Molecular mobility increases dramatically above Tg. The Flory-Fox equation describes the dependence of Tg on Mw for polymers:

Tg = Tg∞ - K / Mn

Where Tg∞ is the Tg at infinite molecular weight, K is a constant related to free volume, and Mn is the number average molecular weight. For low-Mw drug molecules or oligomers, this results in a significantly depressed Tg. When the storage temperature (T) approaches or exceeds this low Tg (i.e., T - Tg > 0), molecular mobility is high, driving physical instability.

3. Mechanisms of Instability

- Crystallization: Increased mobility allows drug molecules to nucleate and grow into a crystalline lattice.

- Phase Separation: In amorphous solid dispersions, increased mobility can enable phase separation of the drug from the polymer matrix.

- Chemical Degradation: Enhanced mobility facilitates interaction between reactive species.

4. Experimental Protocols for Risk Assessment

4.1. Determining Tg and Molecular Mobility

- Method: Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (mDSC)

- Protocol: Weigh 3-5 mg of sample into a T-zero pan. Hermetically seal. Run a modulation cycle (e.g., ±0.5°C every 60 seconds) with an underlying heating rate of 2°C/min from 0°C to 200°C. Analyze the reversing heat flow signal to determine Tg (midpoint).

- Key Parameter: ΔT = Storage Temperature - Tg. A ΔT > 0 indicates risk.

4.2. Accelerated Stability Testing

- Method: Isothermal Storage at Controlled Humidity

- Protocol: Place samples in open or controlled-humidity chambers (e.g., 40°C/75% RH, 30°C/65% RH). Withdraw aliquots at predetermined intervals (0, 1, 3, 6 months). Analyze for crystallinity (PXRD), homogeneity (mDSC, microscopy), and potency (HPLC).

4.3. Quantifying Crystallization Kinetics

- Method: Hot Stage Microscopy (HSM) with Image Analysis

- Protocol: Disperse a small sample on a quartz slide. Heat on a programmable hot stage at a rate of 10°C/min to a temperature 20°C above Tg and hold isothermally. Use polarized light and a camera to record nucleation and crystal growth. Analyze images to determine nucleation induction time and crystal growth rate.

5. Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Molecular Weight on Tg and Stability Outcomes

| Drug Compound | Mw (g/mol) | Measured Tg (°C) | ΔT at 25°C (°C) | Stability Outcome (40°C/75% RH, 3 mo) | Reference Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin | 357.8 | ~42 | +17 | Crystallized (>50%) | Low Mw, Low Tg |

| Itraconazole | 705.6 | ~59 | +34 | Stable Dispersion | Higher Mw, Higher Tg |

| Griseofulvin | 352.8 | ~88 | -63 | Stable Amorphous | Low Mw, High Tg |

| Sucrose | 342.3 | ~52 | +27 | Crystallized | Low Mw, Low Tg |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymer Carriers | To create amorphous solid dispersions and modulate Tg. | PVP-VA64 (Tg ~106°C), HPMCAS (Tg ~120°C), Soluplus (Tg ~70°C) |

| Desiccant | To maintain low-humidity environment during storage or handling. | Indicating silica gel, molecular sieves (3Å or 4Å) |

| Standard Reference Materials | For calibration of thermal and diffraction equipment. | Indium (mDSC cal.), Silicon powder (PXRD angle cal.) |

| Moisture-Control Saturated Salt Solutions | To generate specific constant relative humidity in stability chambers. | K2SO4 (97% RH), NaCl (75% RH), MgCl2 (33% RH) |

| Anti-Static Tools | To prevent electrostatic adhesion of low-Mw, low-Tg powders. | Ionizing air blower, antistatic trays |

6. Visualizations

6.1. Relationship Flow: Mw to Instability

6.2. Experimental Stability Workflow

7. Mitigation Strategies To counteract the instability caused by low Mw and low Tg, strategic formulation is required:

- Polymer Selection: Employ high-Tg polymers (e.g., cellulose derivatives) to elevate the overall Tg of the dispersion.

- Antiplasticizers: Incorporate small molecules that increase Tg and reduce mobility without promoting crystallization.

- Rigid Matrix Design: Utilize matrices that provide kinetic stabilization via high viscosity and specific molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) even above Tg.

- Packaging: Utilize high-barrier, desiccant-containing packaging to eliminate moisture-mediated plasticization.

8. Conclusion Within the study of molecular weight's effect on Tg, the low Mw/low Tg scenario presents a clear and present risk for amorphous drug products. A systematic approach combining predictive thermal analysis, accelerated stability protocols, and kinetic studies is essential for identifying this risk early in development. Proactive mitigation through intelligent material science and formulation design is critical to ensuring the shelf-life and efficacy of advanced amorphous drug delivery systems.

This whitepaper explores a fundamental relationship in amorphous solid dispersions and related systems: the direct link between the molecular mobility above the glass transition temperature (Tg) and the propensity for recrystallization. This discussion is framed within the broader thesis investigation of "How does molecular weight affect glass transition temperature research?" Molecular weight (MW) is a primary determinant of Tg, with higher MW polymers typically exhibiting higher Tg due to reduced chain mobility and increased entanglements. Understanding this MW-Tg relationship is critical because Tg sets the baseline for the key driver of physical instability: molecular mobility at storage temperature, quantified as (T-Tg). This guide delves into the technical principles, experimental evidence, and practical methodologies for studying this link, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for predicting and mitigating crystallization.

Theoretical Foundation: Molecular Mobility and the T-Tg Paradigm

Below Tg, molecules are trapped in a glassy, non-equilibrium state with very low mobility. As temperature increases above Tg, systems enter the "rubbery" or supercooled liquid state, where molecular mobility increases dramatically. The molecular mobility (τ) in this region is often described by the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) or Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann (VFT) equations, which are strongly dependent on (T-Tg).

[ \text{WLF: } \log aT = \frac{-C1 (T - Tg)}{C2 + (T - T_g)} ]

where (a_T) is the mobility shift factor. The core thesis is that the rate of crystallization (G) is directly proportional to this molecular mobility:

[ G \propto \frac{1}{\tau} \propto f(T - T_g) ]

Therefore, for a given storage temperature (T), a higher Tg (resulting from, for example, a higher MW polymer) leads to a lower (T-Tg), reduced molecular mobility, and consequently, lower crystallization propensity.

Quantitative Data: Key Studies and Findings

The following table summarizes seminal and recent studies illustrating the relationship between (T-Tg), molecular mobility metrics, and observed crystallization times.

Table 1: Correlation Between (T-Tg), Mobility, and Recrystallization Onset

| System (API/Polymer) | Tg of Mixture (°C) | Storage T (°C) | (T-Tg) (°C) | Mobility Metric (e.g., τₐ, D) | Time to Crystallize | Reference Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin (IMC) / PVP VA64 | 50 | 40 | -10 | β-relaxation: 10⁵ s | > 1 year | Below Tg, only local β-mobility; stability high. |

| IMC / PVP VA64 | 50 | 60 | +10 | α-relaxation: 10² s | ~ 7 days | Onset of global mobility drives crystallization. |

| Felodipine / HPMCAS | 75 | 40 | -35 | Very high τₐ | > 24 months | Large negative (T-Tg) ensures stability. |