Thermoplastic Polymers: Properties, Biomedical Applications, and Advanced Material Design for Drug Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of thermoplastic polymers, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Thermoplastic Polymers: Properties, Biomedical Applications, and Advanced Material Design for Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of thermoplastic polymers, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores fundamental material properties, structure-property relationships, and advanced processing techniques like additive manufacturing. The scope includes specialized applications in controlled drug delivery, tissue engineering, and smart thermo-responsive systems, alongside critical discussions on material selection, troubleshooting processing challenges, and validation through standardized testing. The content synthesizes current research and future directions to guide the development of next-generation biomedical devices and therapies.

Understanding Thermoplastic Polymers: Molecular Structures and Fundamental Properties

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of thermoplastic polymers, focusing on their defining reversible thermal behavior and fundamental distinctions from thermosetting polymers. Within the broader context of advanced polymer research, this paper details the molecular mechanisms underpinning thermoplasticity, presents comparative quantitative data, and explores advanced applications driving innovation in aerospace, electronics, and biomedical fields. The content is structured to serve researchers and scientists by synthesizing current material properties, research trends, and standardized experimental protocols essential for material selection and development in high-performance applications.

Polymers are broadly classified into two categories based on their behavioral response to thermal energy: thermoplastics and thermosets. This differentiation is not merely procedural but is rooted in fundamental molecular architecture, which dictates processing methodologies, material properties, and end-of-life options, such as recyclability [1] [2].

Thermoplastics are characterized by polymer chains that are linear or slightly branched, lacking permanent covalent bonds between the chains. This structure allows them to be repeatedly softened and melted when heated and solidified upon cooling, a process that is fundamentally reversible [1] [3]. This reversibility enables recycling and remolding, making them highly versatile.

In contrast, thermosetting plastics (thermosets) undergo an irreversible chemical curing process. During this process, polymer chains form a dense, three-dimensional network of covalent bonds, known as cross-links [1] [4]. This cross-linked structure prevents thermosets from being remelted or reshaped upon reheating; instead, they will chemically degrade and char [1].

The selection between thermoplastic and thermoset materials is critical in product design, impacting everything from manufacturing costs and production rates to structural integrity, thermal performance, and environmental sustainability [1] [5].

Fundamental Mechanism of Thermoplasticity

Molecular Structure and Reversible Thermal Transitions

The defining property of thermoplastics—their reversible thermal behavior—stems directly from their molecular structure. These polymers consist of long, discrete molecular chains held together by weak secondary intermolecular forces, such as van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding [1] [3].

- Linear and Branched Chains: Unlike the permanently cross-linked networks in thermosets, the chains in thermoplastics are physically entangled but not chemically bound to each other [3] [2].

- Effect of Heat: When heat is applied, the input of thermal energy overcomes the weak secondary forces between the chains. This allows the chains to slide past one another, rendering the material soft and pliable (melted) [1].

- Reversibility: Upon cooling, the molecular motion slows, and the secondary intermolecular forces re-establish, causing the material to regain its solid-state rigidity. This heating-cooling cycle can be repeated multiple times with minimal degradation of the polymer's inherent properties, enabling reprocessing and recycling [3] [5].

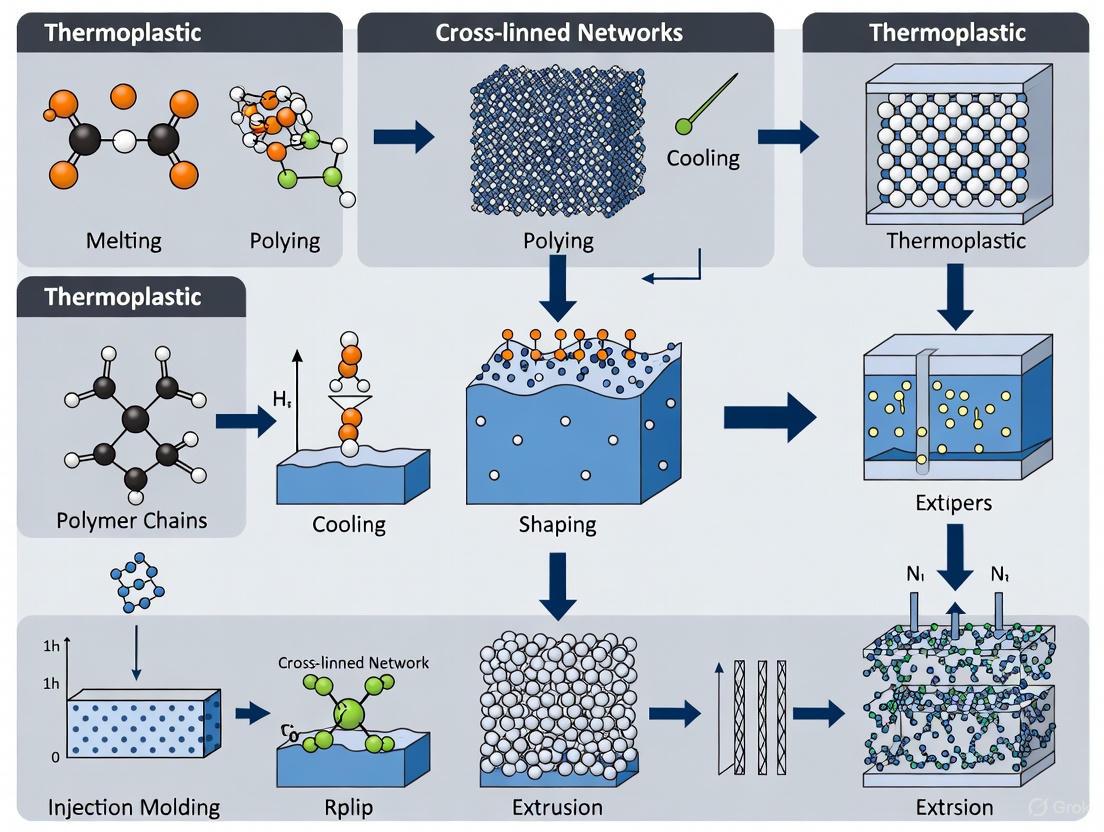

The following diagram illustrates the reversible thermal process and molecular dynamics of thermoplastics, contrasting with the irreversible curing of thermosets.

Classification of Thermoplastics

Thermoplastics are further categorized based on their structural order, which significantly influences their optical, mechanical, and thermal properties.

Amorphous Thermoplastics: These possess a randomly ordered, entangled molecular structure, lacking long-range arrangement. They do not have a sharp melting point but instead soften gradually over a wide temperature range as they pass through their glass transition temperature (Tg). This structure typically results in materials that are translucent or transparent, exhibit low shrinkage, and have poor chemical resistance. Examples include Polystyrene (PS), Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), and Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) [3] [6].

Semi-Crystalline Thermoplastics: These feature regions of highly ordered, packed molecular chains (crystallites) embedded within amorphous regions. This structure gives them a sharp melting point (Tm), higher chemical resistance, greater strength, and higher shrinkage during molding. They are typically opaque or translucent. Common examples are Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP), Polyamide (PA, Nylons), and Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) [3] [6].

Furthermore, thermoplastics are often graded by performance and cost into commodity (e.g., PE, PP, PVC), engineered (e.g., PC, POM, PA), and high-performance (e.g., PEEK, PPS, LCP) categories, each serving distinct application sectors [3] [6].

Comparative Analysis: Thermoplastics vs. Thermosets

The molecular-level differences between thermoplastics and thermosets manifest as distinct practical characteristics. The table below provides a direct comparison of their key properties.

Table 1: Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of Thermoplastics and Thermosets

| Property | Thermoplastics | Thermosets |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Linear or branched chains [4] [2] | Cross-linked, 3D network [4] [2] |

| Response to Heat | Softens/melts reversibly [1] [3] | Chars/degrades irreversibly [1] |

| Recyclability | Highly recyclable [1] [5] | Non-recyclable [1] [5] |

| Typical Melting Point (Tm) | Distinct Tm for semi-crystalline types [3] | Does not melt, degrades at high T [1] |

| Continuous Use Temperature | Generally lower | Higher (e.g., >200°C for epoxies) [1] |

| Dimensional Stability | Prone to creep over time/load [3] | Excellent, high rigidity [1] [5] |

| Chemical Resistance | Moderate to good, varies by type [3] | Superior (e.g., to fuels, solvents) [1] [7] |

| Impact Resistance | Generally high [1] [5] | Can be brittle [1] |

| Manufacturing Cost | Higher material cost, efficient processing [1] [5] | Lower material cost, longer cycle times [1] |

| Primary Processing Methods | Injection Molding, Extrusion, Thermoforming [3] [8] | Reaction Injection Molding (RIM), Resin Transfer Molding (RTM) [1] [8] |

Performance Trade-offs and Selection Criteria

The data in Table 1 highlights inherent performance trade-offs. Thermosets provide superior thermal stability, structural integrity, and chemical resistance due to their cross-linked matrix, making them indispensable for under-the-hood automotive components, electrical insulators, and aerospace composites that must withstand extreme environments [1] [2].

Thermoplastics, while generally having lower maximum service temperatures, offer unparalleled manufacturing flexibility, impact resistance, and sustainability benefits through their recyclability. The emergence of High-Performance Thermoplastics (HPTPs) like PEEK and PPS has significantly narrowed the thermal and mechanical performance gap, enabling their adoption in demanding sectors [7] [6].

Advanced Applications and Research Trends

Advanced thermoplastics are experiencing rapid growth, driven by global trends in lightweighting, electrification, and sustainability.

High-Performance Thermoplastics in Avionics and Aerospace

The aerospace industry is leveraging high-performance thermoplastics like PEEK, PEI (Ultem), and PPS to achieve significant weight reduction, which directly translates to improved fuel efficiency and lower emissions [7]. These materials are critical in next-generation aircraft, such as the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787, which are approximately 50% composite materials [7].

- Key Applications: Sensor housings, cable insulation, brackets, and bushings [7].

- Material Demands: Must maintain structural integrity under extreme thermal cycling (e.g., -55°C to +95°C), exhibit low outgassing in vacuum (per NASA ASTM E595), and resist jet fuels and hydraulic fluids [7]. PEEK, for instance, has a continuous service temperature of 260°C and a melting point of 343°C [7].

Electrification and Automotive Lightweighting

The markets for electric vehicles (EVs) and e-mobility are major drivers for engineering thermoplastics.

- EV Applications: PBT, Polyamide (Nylon), and Polycarbonate blends are central to battery housings, connectors, charging systems, and power electronics, where they provide electrical insulation, thermal management, and flame retardancy [9].

- Market Growth: The Advanced Engineering Thermoplastics (AETs) market is projected to grow from USD 13.8 billion in 2025 to USD 24.5 billion by 2032, with a strong CAGR of 7.6% [9].

Sustainability and Material Innovation

Growing environmental regulations are accelerating research into sustainable material solutions.

- Recyclability: The innate recyclability of thermoplastics positions them favorably in a circular economy model [9] [5].

- Bio-based Thermoplastics: Innovations like large-scale sugarcane-based Polylactic Acid (PLA) production are gaining market traction, reducing reliance on petrochemical feedstocks [9].

- Polymer Compatibilizers: Research is intensifying in using thermoplastic elastomer-grafted compatibilizers (e.g., MAH-g-SEBS, GMA-g-POE) to enhance the compatibility and properties of polymer blends and composites, facilitating the use of recycled content and bio-based polymers [10].

Experimental Protocols for Material Characterization

Standardized testing is crucial for validating material properties for research and qualification. Below are protocols for key experiments relevant to thermoplastic analysis.

Thermal Cycling for Avionics Components

Objective: To evaluate the dimensional stability and integrity of thermoplastic components subjected to in-flight temperature extremes [7].

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Condition test specimens at 50% relative humidity for 24 hours [7].

- Test Parameters: Program an environmental chamber to cycle between -55°C and +85°C (or up to +95°C for more severe testing). The standard transition rate is 10°C per minute to simulate rapid altitude changes [7].

- Cycling: Expose the components to a predetermined number of cycles (e.g., 50-1000 cycles).

- Post-Test Analysis: Visually and microscopically inspect for failures such as warpage, cracking, or solder joint fatigue. Measure critical dimensions to quantify dimensional stability [7].

Outgassing Measurement for Space-Grade Components

Objective: To determine the suitability of thermoplastics for vacuum (space) environments by measuring volatile content per NASA standards [7].

Methodology:

- Pre-conditioning: Weigh samples and condition at 50% relative humidity for 24 hours [7].

- Vacuum Exposure: Place samples in a vacuum chamber at 125°C for 24 hours [7].

- Measurement:

- Total Mass Loss (TML): Weigh the sample after exposure. TML must be ≤ 1.0%.

- Collected Volatile Condensable Materials (CVCM): Measure the mass of volatiles that condense on a cooled collector plate (typically 25°C). CVCM must be ≤ 0.10%. For highly sensitive optical applications, CVCM < 0.01% may be required [7].

Analysis of Polymer Blends Using Compatibilizers

Objective: To improve the interfacial compatibility and mechanical properties of immiscible polymer blends, a key area in polymer research [10].

Methodology:

- Selection: Choose an appropriate compatibilizer based on the blend components. Common compatibilizers include Maleic Anhydride-grafted-SEBS (MAH-g-SEBS) for polyolefin blends or Glycidyl Methacrylate-grafted-POE (GMA-g-POE) for blends involving reactive groups [10].

- Melt Blending: Use a twin-screw extruder to compound the base polymer matrix, dispersed phase, and compatibilizer (typically 1-5% by weight). Key parameters are screw speed, temperature profile, and feed rate [10].

- Characterization:

- Morphology: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to analyze phase dispersion and interface quality.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile and impact tests to quantify improvements in toughness and strength [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Advanced Thermoplastics Research

| Research Material / Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| PEEK (Polyetheretherketone) | High-performance matrix for extreme environments; used in sensor housings, avionics brackets for its high melting point (343°C) and chemical resistance [7]. |

| MAH-g-SEBS (Maleic Anhydride-grafted-Styrene-Ethylene-Butylene-Styrene) | Reactive compatibilizer; enhances toughness and interfacial adhesion in polyolefin blends and composites [10]. |

| PEI (Polyetherimide, Ultem) | Amorphous high-performance thermoplastic; used for lightweight structural brackets and ducting requiring high flame, smoke, and heat resistance [7]. |

| GMA-g-POE (Glycidyl Methacrylate-grafted-Polyethylene-Octene) | Reactive compatibilizer; the epoxy functional group of GMA can react with polymers like polyamide or polyester, improving blend compatibility [10]. |

| Carbon Fiber Reinforcements | Dispersed phase additive; significantly increases tensile strength, modulus, and thermal stability of thermoplastic composites [7] [6]. |

The fundamental identity of thermoplastic polymers is defined by their reversible thermal behavior, a direct consequence of their linear or branched molecular structure held by secondary intermolecular forces. This stands in stark contrast to the irreversibly cross-linked network of thermosets. This foundational difference propagates through every aspect of material performance, from the superior recyclability and manufacturing flexibility of thermoplastics to the exceptional thermal stability and structural rigidity of thermosets.

Current research and market trends indicate a growing dominance of advanced engineering and high-performance thermoplastics, driven by the critical needs for lightweighting in aerospace and automotive electrification, enhanced material sustainability, and the development of sophisticated polymer blends through compatibilizer technology. A deep understanding of the principles, properties, and characterization methods detailed in this guide is therefore essential for researchers and scientists pushing the boundaries of polymer science and its applications in modern technology.

The molecular architecture of a polymer—the way in which its chains are arranged and interconnected—serves as the fundamental determinant of its macroscopic properties and ultimate applications. For researchers focused on thermoplastic polymers, understanding the distinction between linear and cross-linked architectures is paramount, as this distinction directly dictates material processability, mechanical performance, and thermal stability [11] [12]. Linear polymers, characterized by long, chain-like molecules resembling spaghetti, are held together primarily by weaker secondary forces such as van der Waals forces or hydrogen bonding [12]. In contrast, cross-linked polymers form a three-dimensional network where polymer chains are connected via strong covalent bonds, creating a permanent, interconnected structure [11]. This foundational difference in molecular structure creates a divergence in material behavior, particularly in response to heat, which classifies polymers into two broad categories: thermoplastics (typically linear or branched) and thermosets (cross-linked or networked) [1].

Within the context of advanced materials research, the deliberate manipulation of polymer architecture provides a powerful pathway for tailoring properties to meet specific application demands. The ability to design polymers with precise control over branching, cross-link density, and network formation enables scientists to engineer materials with unprecedented combinations of strength, toughness, and environmental resistance [11] [13]. This technical guide explores the fundamental structure-property relationships in linear and cross-linked polymers, providing detailed experimental methodologies and analytical frameworks for researchers engaged in the development of next-generation polymeric materials.

Fundamental Structures and Their Characteristics

Linear Polymers

Linear polymers consist of a primary backbone of repeating monomer units without any covalent connections between different chains [12]. This relatively simple structure allows the polymer chains to pack efficiently, often resulting in semi-crystalline morphologies where ordered crystalline regions coexist with disordered amorphous domains. The absence of permanent interchain connections means that the material relies on temporary, physical entanglements and weaker intermolecular forces (e.g., van der Waals forces, dipole-dipole interactions, or hydrogen bonding) to maintain structural integrity [12]. When sufficient thermal energy is applied, these weak forces are readily overcome, allowing the chains to slide past one another and enabling the polymer to be repeatedly melted and reshaped—a defining characteristic of thermoplastic behavior [1] [14].

The physical properties of linear polymers are significantly influenced by their molecular weight and chain length. Higher molecular weights generally lead to increased chain entanglements, resulting in enhanced mechanical strength, toughness, and melt viscosity [11]. However, linear polymers exhibit a distinct limitation: they will eventually dissolve in compatible solvents or swell significantly when exposed to chemical agents, as solvent molecules can penetrate and separate the polymer chains without breaking primary covalent bonds [15]. Common examples of linear polymers prevalent in research and industrial applications include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and nylon [16] [12].

Cross-linked Polymers

Cross-linked polymers possess a fundamentally different architecture characterized by covalent bonds connecting adjacent polymer chains into a permanent three-dimensional network [11] [15]. These cross-links, often referred to as "chemical bridges," effectively transform multiple individual polymer chains into a single macromolecular network. This network structure profoundly alters the material's response to environmental stimuli compared to its linear counterparts. Unlike linear polymers, cross-linked structures cannot melt or flow upon heating because the covalent cross-links remain intact even at elevated temperatures [1] [17]. Instead of flowing, highly cross-linked polymers will typically degrade or char when exposed to excessive heat, as the thermal energy is sufficient to break the primary chains themselves before the cross-links fail [1].

The cross-link density—the number of cross-links per unit volume—serves as a critical parameter determining the final properties of the material. A low degree of cross-linking, as seen in elastomers like vulcanized rubber, restricts permanent chain slippage while still allowing for substantial chain mobility and elongation, resulting in highly elastic materials [15] [13]. As cross-link density increases, the polymer becomes more rigid, dimensionally stable, and resistant to creep, ultimately forming hard, glassy thermosets such as epoxies and phenolic resins [11] [13]. This architectural transformation renders cross-linked polymers insoluble in all solvents, though they may exhibit varying degrees of swelling depending on the cross-link density and polymer-solvent compatibility [15]. The swollen state represents an equilibrium between the elastic retraction force of the stretched network and the osmotic driving force for solvent penetration.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Linear and Cross-linked Polymers

| Property | Linear Polymers | Cross-linked Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Interchain Forces | Weak van der Waals, hydrogen bonds [12] | Strong covalent bonds [11] |

| Response to Heat | Melt upon heating, can be remolded [1] | Do not melt, degrade at high temperatures [1] |

| Solubility | Soluble in appropriate solvents [15] | Insoluble, may swell [15] |

| Primary Material Class | Thermoplastics [12] | Thermosets [1] |

| Recyclability | Recyclable and reshapable [14] | Generally non-recyclable [14] |

| Typical Examples | PE, PP, PVC, Nylon [16] | Epoxy, Vulcanized Rubber, Phenolics [11] |

Structure-Property Relationships

The relationship between molecular architecture and macroscopic properties represents a cornerstone of polymer science, enabling researchers to predict and engineer material behavior through structural design.

Mechanical Properties

The mechanical performance of polymers exhibits a strong dependence on architectural structure. Linear polymers generally demonstrate good toughness and impact resistance, but may be susceptible to creep (time-dependent deformation under load) due to chain slippage over time [11] [13]. Their mechanical properties are highly dependent on molecular weight—increasing chain length enhances mechanical strength up to a critical point where entanglement density provides sufficient load distribution across chains [11].

Cross-linked polymers exhibit markedly different mechanical behavior dictated by their network structure. The introduction of cross-links dramatically enhances tensile strength, hardness, and dimensional stability by preventing permanent chain slippage [11] [13]. The cross-link density serves as the primary regulator of mechanical behavior: low cross-link densities produce elastomeric materials capable of large, reversible deformations (e.g., rubber bands), while high cross-link densities yield rigid, glassy materials with high modulus but limited elongation (e.g., epoxy resins) [15] [13]. An important mechanical limitation of highly cross-linked systems is their tendency toward brittle fracture with reduced impact resistance, as the densely cross-linked network impedes plastic deformation mechanisms that dissipate energy [14].

Thermal Properties

Thermal behavior represents one of the most distinguishing characteristics between linear and cross-linked architectures. Linear polymers undergo several important thermal transitions. The glass transition temperature (Tg) marks the transition from a glassy to a rubbery state in amorphous regions, while the melting temperature (Tm) corresponds to the disruption of crystalline domains [11]. Above these transitions, linear polymers flow as viscous liquids, enabling thermoplastic processing techniques such as injection molding and extrusion [1].

Cross-linked polymers display fundamentally different thermal behavior due to their continuous network structure. These materials do not exhibit a true melting transition and instead maintain their structural integrity up to the thermal decomposition temperature [1] [17]. Cross-linking typically increases the glass transition temperature (Tg) by restricting chain segment mobility in the amorphous regions, with the magnitude of this increase being proportional to cross-link density [11]. This enhanced thermal stability makes cross-linked polymers indispensable for applications requiring prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures, such as automotive components, aerospace composites, and thermal insulation systems [11] [1].

Chemical Resistance

Chemical resistance varies significantly between linear and cross-linked polymer architectures. Linear polymers are generally susceptible to attack by solvents and chemicals that disrupt the secondary forces between chains, leading to dissolution or swelling depending on the polymer-solvent compatibility [15]. This susceptibility can limit their use in aggressive chemical environments.

Cross-linked polymers exhibit superior chemical resistance due to their interconnected network, which acts as a barrier against solvent penetration and chemical attack [11]. Rather than dissolving, these materials may reach an equilibrium swelling state where solvent uptake is balanced by the elastic retraction of the stretched network [15]. The degree of swelling is inversely related to cross-link density—higher cross-link densities result in less swelling. Different cross-linked systems offer specialized chemical resistance profiles; for example, vinyl ester resins demonstrate excellent resistance to acids, alkalis, and oxidizing agents, while epoxy resins show broad resistance to various chemicals including bases [11].

Table 2: Thermal and Chemical Property Comparison

| Property | Linear Polymers | Cross-linked Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Melting Behavior | Distinct melting point [1] | No melting point, degrades instead [1] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | Distinct Tg, affected by molecular weight [11] | Increased Tg, proportional to cross-link density [11] |

| Thermal Stability | Limited by melting temperature [1] | High, maintains shape until decomposition [17] |

| Solvent Resistance | Dissolves in compatible solvents [15] | Insoluble, limited swelling [15] |

| Acid/Base Resistance | Varies by polymer chemistry | Excellent, especially vinyl esters and epoxies [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Architectural Analysis

Synthesis and Cross-linking Methodologies

The experimental creation and characterization of polymer architectures requires precise control of synthesis parameters and cross-linking protocols. The following methodologies represent key approaches for generating and analyzing linear and cross-linked polymer systems.

Chemical Cross-linking Protocol

Chemical cross-linking represents the most common method for creating permanent, three-dimensional polymer networks. The following protocol describes a generalized procedure for cross-linking polyolefins using dicumyl peroxide (DCP) as a model cross-linking agent [11].

Materials Required:

- Polymer substrate (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene)

- Cross-linking agent (e.g., dicumyl peroxide, 98% purity)

- Internal mixer (e.g., Brabender Plastograph) or twin-screw extruder

- Compression molding press

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g accuracy)

Procedure:

- Formulation Preparation: Weigh predetermined quantities of polymer and DCP cross-linker (typical concentration range: 0.5-3.0 phr [parts per hundred resin]) using an analytical balance.

- Melt Blending: Feed the polymer and cross-linker mixture into an internal mixer preheated to 20-30°C above the polymer's melting point but below the peroxide decomposition temperature (e.g., 130°C for polyethylene with DCP). Mix at 60 rpm for 5-8 minutes until torque stabilization indicates uniform dispersion.

- Cross-linking Activation: Increase mixer temperature to the peroxide activation temperature (e.g., 160-180°C for DCP) for 5-10 minutes to initiate the cross-linking reaction, monitoring torque increase as evidence of network formation.

- Sheet Formation: Transfer the cross-linked material to a preheated compression mold and press at 10-15 MPa for 5-10 minutes at the cross-linking temperature, followed by cooling under pressure to room temperature.

- Post-processing: Machine the cross-linked sheets into appropriate specimens for subsequent characterization.

Key Experimental Variables:

- Cross-linker concentration (directly controls cross-link density)

- Processing temperature and time (affects cross-linking efficiency and potential degradation)

- Polymer molecular characteristics (molecular weight, branching)

Characterization Techniques

Analytical characterization provides essential data for understanding the relationship between polymer architecture and material properties.

Solvent Extraction Testing

Solvent extraction represents a straightforward, quantitative method for determining the degree of cross-linking in polymer networks by measuring the insoluble gel fraction [15].

Materials Required:

- Solvent reflux apparatus (round-bottom flask, condenser, heating mantle)

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., xylene for polyolefins, toluene for rubbers)

- Precision balance (±0.0001 g)

- Drying oven

- Stainless steel mesh cages or tea bags

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh (W₀) approximately 0.5g of cross-linked polymer and place it in a pre-weighed stainless steel mesh cage.

- Extraction: Immerse the sample in boiling solvent for 12-24 hours to extract all soluble (uncross-linked) material.

- Recovery: Remove the sample from solvent and dry in a vacuum oven at elevated temperature (e.g., 80°C) until constant weight is achieved (typically 24 hours).

- Final Weighing: Precisely determine the final weight of the dried, extracted sample (Wƒ).

- Calculation: Calculate the gel fraction (cross-linked portion) using the formula: Gel Fraction (%) = (Wƒ / W₀) × 100

Interpretation:

- Values approaching 100% indicate highly cross-linked networks

- Lower values suggest incomplete cross-linking or network defects

- Comparison across samples provides relative cross-link density assessment

Melt Flow Index (MFI) Monitoring

Melt Flow Index measurement provides an efficient method for monitoring the progression of cross-linking in polyolefin systems by tracking changes in melt processability [11].

Materials Required:

- Melt flow indexer (standard ASTM D1238 apparatus)

- Temperature control unit (±0.1°C accuracy)

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g)

- Timing device

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Preheat the MFI apparatus to the standard temperature for the polymer being tested (e.g., 190°C for polyethylene, 230°C for polypropylene).

- Sample Loading: Charge the barrel with approximately 4-5g of polymer sample.

- Equilibration: Allow the sample to thermally equilibrate for 4-5 minutes.

- Measurement: Apply the standard weight (2.16 kg for polyethylene) and collect extrudate over a timed interval (typically 2-10 minutes, depending on flow rate).

- Calculation: Weigh the extrudate and calculate the melt flow rate in g/10 min according to ASTM D1238.

Data Interpretation:

- Decreasing MFI values indicate increasing molecular weight and cross-link formation

- Drastic MFI reduction suggests extensive network formation

- Complete absence of flow may indicate high cross-link density

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dicumyl Peroxide (DCP) | Free radical generator for polyolefin cross-linking [11] | Concentration controls cross-link density; thermal decomposition characteristics critical |

| Sulfur | Traditional vulcanizing agent for rubber [11] [15] | Forms polysulfide bridges between unsaturated chains; accelerator systems often required |

| Epoxy Resins (DGEBA) | Form highly cross-linked networks with hardeners [11] | Stoichiometric balance with curing agent critical; wide range of hardeners available |

| Divinylbenzene | Cross-linking co-monomer in polymerization [13] | Provides pendant vinyl groups for network formation; used in styrenic systems |

| Toluene/Xylene | Solvents for extraction testing [15] | Polymer-specific selection; reflux conditions required for complete extraction |

Advanced Architectural Systems and Research Applications

Hybrid and Complex Architectures

Beyond simple linear and cross-linked systems, advanced polymer architectures offer enhanced property profiles and functionality. Branched polymers represent an intermediate architecture where side chains extend from the main backbone, disrupting chain packing and reducing crystallinity compared to linear analogs [13] [12]. Low-density polyethylene (LDPE), with its substantial short-chain and long-chain branching, exemplifies how branching can improve processability and flexibility while reducing density [13].

Network polymers constitute an extreme case of cross-linking where a high density of three-dimensional connections creates a continuous network structure [13] [12]. These materials, including epoxy resins and phenol-formaldehyde systems, exhibit exceptional thermal stability, mechanical strength, and chemical resistance, but are typically brittle and cannot be processed after curing [13]. Recent research focuses on controlled cross-linking methodologies that enable precise spatial and density control of cross-links, potentially allowing for optimization of both strength and toughness in the same material.

Emerging Research Directions

Contemporary research in polymer architectures explores several promising directions with significant implications for advanced applications. Supramolecular polymers utilize reversible non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, π-π stacking) to create physically cross-linked networks that can be reprocessed while maintaining thermoset-like properties [11]. These materials offer potential solutions to the recyclability challenges associated with conventional thermosets.

Stimuli-responsive networks incorporate cross-links that respond to specific environmental triggers such as pH, light, or redox conditions, enabling dynamically tunable material properties [11]. In biomedical applications, research continues on degradable cross-linked systems for drug delivery and tissue engineering, where controlled network breakdown enables predictable release profiles or scaffold remodeling [11]. Additionally, advanced characterization techniques including solid-state NMR, neutron scattering, and high-resolution rheology provide unprecedented insights into network topology and dynamics, facilitating more precise structure-property relationships.

Visualizing Architectural Transitions and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts and experimental approaches for analyzing polymer architectures, providing visual representations of the structural relationships and characterization methodologies discussed in this guide.

Polymer Architecture Transition Pathways

Polymer Cross-linking Analysis Workflow

For researchers and scientists engaged in thermoplastic polymers research, a rigorous understanding of critical thermal properties is fundamental to material selection, polymer design, and predicting product performance. These properties dictate a polymer's behavior during processing and its ultimate service conditions. Within the context of drug development, this knowledge is crucial for applications ranging from medical device housing and surgical instruments to drug delivery systems and labware, where materials must maintain structural integrity under thermal stress. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three cornerstone thermal properties: Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), Melting Point (Tm), and Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT). It is structured to serve as a technical reference, complete with comparative data tables, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource lists to support research and development activities.

Defining the Critical Thermal Properties

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) is the temperature region where an amorphous polymer transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state [18]. This transition marks the onset of long-range, coordinated molecular motion in the polymer chains, which occurs over a temperature range rather than at a single sharp point [19]. It is a second-order transition associated with a change in the heat capacity and the coefficient of thermal expansion, but without a latent heat of transition. The value of Tg profoundly influences mechanical properties such as stiffness, brittleness, and impact resistance at a given use temperature [19]. For a semi-crystalline polymer, the amorphous regions undergo this transition, while the crystalline regions remain ordered until the melting point.

Melting Point (Tm)

The Melting Point (Tm) is the temperature at which the crystalline regions of a semi-crystalline polymer melt, transforming from an ordered solid to a disordered liquid melt [19]. This is a first-order transition characterized by an endothermic peak and an associated latent heat. The Tm defines the upper limit for melt-processing techniques like injection molding and extrusion and sets the maximum service temperature for applications requiring structural integrity. It is always higher than the Tg for a given semi-crystalline polymer, with an empirical relationship often noted as ( Tm \approx 1.5 Tg ) when both are expressed in Kelvin [19].

Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT)

The Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT), also known as the Deflection Temperature Under Load (DTUL), is a pragmatic measure of a polymer's short-term resistance to deformation under a specified flexural load at elevated temperatures [20] [21]. Essentially, it is the temperature at which a standard polymer test bar deflects by 0.25 mm under a defined load in a uniformly heated fluid bath [20]. Unlike Tg and Tm, which are intrinsic material properties, HDT is a comparative index of thermal performance under load, heavily influenced by factors like polymer composition, fillers, and reinforcement [20]. It is critically important for screening materials for structural applications in elevated temperature environments, such as automotive components and electronics housing [20].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Thermal Properties

| Property | Nature of Transition | Molecular Scale Phenomenon | Primary Influence on Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Second-order transition (change in slope of property curve) | Onset of long-range coordinated motion in amorphous regions [19] [18] | Transforms from a hard/glassy to a soft/rubbery material; affects stiffness and toughness [19] |

| Melting Point (Tm) | First-order transition (endothermic peak with latent heat) | Melting of crystalline regions into an amorphous melt [19] | Loss of structural integrity; defines upper limit for melt processing [19] |

| Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT) | Empirical property measured under specific test conditions | A practical measure of stiffness retention under load and heat [20] [21] | Indicates the upper service temperature for a material under a specific mechanical load [20] |

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

The following tables provide representative data for common thermoplastics, allowing for direct comparison and initial material screening. Note that specific grades, additives, and reinforcements can significantly alter these values.

Table 2: Thermal Properties of Common Thermoplastics

| Polymer Name | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | HDT @ 1.8 MPa (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | ~105 [22] | - | 88 - 100 [20] [21] |

| Polycarbonate (PC), high heat | ~150 [19] | - | 140 - 180 [21] |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | ~143 | ~343 | 150 - 160 [21] |

| Polyetherimide (ULTEM) | ~217 | - | 190 - 200 [21] |

| Polypropylene (PP) Homopolymer | ~-20 | ~160 | 50 - 60 [21] |

| PP, 30-40% Glass Fiber | ~-20 | ~160 | 125 - 140 [21] |

| Polysulfone (PSU) | ~190 | - | 160 - 174 [21] |

Table 3: Factors Influencing Thermal Properties

| Factor | Effect on Tg | Effect on Tm | Effect on HDT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Increases with molecular weight due to chain entanglement [19] | Increases with molecular weight [19] | Generally increases |

| Chain Rigidity / Aromatic Groups | Increases significantly | Increases significantly | Increases significantly |

| Polar Groups / Hydrogen Bonding | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Crystallinity | Minor direct effect (affects amorphous phase) | Defines the transition; higher crystallinity sharpens Tm | Increases HDT [20] |

| Plasticizers | Decreases Tg by increasing free volume [19] | Little to no effect | Decreases HDT [20] |

| Fillers & Reinforcement (e.g., Glass Fiber) | Very little effect (an intrinsic property) [20] | Very little effect (an intrinsic property) [20] | Increases HDT substantially [20] [21] |

| Crosslinking | Increases Tg by restricting chain mobility [19] | Increases and broadens Tm | Increases |

Experimental Protocols for Measurement

Accurate characterization of thermal properties requires standardized methods. The following sections detail the primary experimental protocols cited in research and industry.

Measuring Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) - Principle: This technique detects changes in the heat capacity of a polymer as it undergoes the glass transition. The sample and a reference are heated at a controlled rate, and the difference in heat flow required to maintain both at the same temperature is measured [19]. - Protocol: A small sample (5-20 mg) is sealed in a crucible and placed in the DSC cell alongside an empty reference crucible. The experiment is run with a heating rate typically between 10-20°C/min under an inert nitrogen atmosphere. The glass transition appears as a step change in the heat flow curve. The Tg value is typically reported as the midpoint of this step [22] [19]. - Advantages: Requires a very small sample size, is quick and highly reproducible [22].

2. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) - Principle: DMA measures the viscoelastic response (storage modulus E', loss modulus E", and tan δ) of a material as a function of temperature, frequency, or time. The glass transition is associated with a dramatic drop in the storage modulus and a peak in the loss modulus and tan δ [22] [19]. - Protocol: A polymer bar or film of defined geometry is clamped and subjected to a small oscillating stress. The temperature is ramped, usually at 2-5°C/min. The Tg can be reported as the onset of the drop in E', the peak of E", or the peak of tan δ, with the tan delta peak typically being several degrees higher than the DSC midpoint [22]. - Advantages: Extremely sensitive to subtle molecular motions and provides mechanical context to the transition.

3. Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) - Principle: TMA monitors dimensional changes (expansion or penetration) in a sample as a function of temperature. The coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) changes significantly at the Tg [22] [19]. - Protocol: A probe rests on the sample with a small, constant force. The temperature is increased, and the probe's displacement is tracked. The Tg is determined from the intersection of the tangents drawn from the glassy and rubbery expansion regions on the thermal expansion curve [22]. - Advantages: Directly measures dimensional stability and CTE.

Measuring Melting Point (Tm)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) - Principle: As a semi-crystalline polymer heats up, its crystalline regions absorb energy (latent heat of fusion) and melt, producing a characteristic endothermic peak in the DSC curve. - Protocol: Using a similar setup to the Tg measurement, the sample is heated through its melting region. The Tm is universally reported as the extrapolated onset temperature or the peak temperature of the endothermic melting event [19]. The area under the peak corresponds to the heat of fusion, which can be used to calculate the degree of crystallinity.

Measuring Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT)

ASTM D648 / ISO 75 - Principle: This test determines the temperature at which a standard polymer test bar deflects 0.25 mm under a defined three-point bending load while the surrounding fluid bath is heated at a uniform rate [20] [21]. - Protocol: - A test bar (typically 127 mm x 13 mm x 3 mm) is placed on two supports 100 mm apart. - A specified load is applied to the midpoint of the bar edgewise. - The entire assembly is submerged in a heat-transfer fluid (usually oil), which is heated at 2°C/min. - The temperature at which the bar deflects by 0.25 mm is recorded as the HDT. - Common Loads: - 0.46 MPa (67 psi): Used for comparing softer materials or for applications with lower loads. - 1.8 MPa (264 psi): The most common load, used for comparing rigid materials and predicting maximum service temperatures under significant mechanical load [20] [21].

Diagram 1: Thermal Property Measurement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key equipment, materials, and standards essential for conducting thermal analysis in a research setting.

Table 4: Essential Materials and Equipment for Thermal Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures heat flow associated with phase transitions (Tg, Tm, crystallization) as a function of temperature [19]. | Ideal for small sample sizes (5-20 mg). Provides data on enthalpy and specific heat capacity. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) | Applies oscillating stress to measure viscoelastic properties (modulus, damping) and determine Tg with high sensitivity [22] [19]. | Multiple clamping fixtures (tension, 3-point bend, shear) are required for different sample geometries. |

| Thermomechanical Analyzer (TMA) | Measures dimensional changes (thermal expansion, softening) of a sample under a negligible load vs. temperature [22] [19]. | Crucial for measuring coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and Tg via penetration or expansion modes. |

| HDT Test Apparatus | Dedicated equipment for performing ASTM D648/ISO 75. Consists of a fluid bath, heating system, loading mechanism, and deflection measurement [20] [21]. | Requires standardized test bars. The oil bath must provide uniform heating at 2°C/min. |

| High-Purity Inert Gas (N₂) | Purging gas for DSC, TMA, and DMA instruments to prevent oxidative degradation of samples at high temperatures. | Essential for obtaining clean, reproducible data, especially for materials prone to oxidation. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Certified materials (e.g., Indium, Zinc) with known melting points and enthalpies for temperature and enthalpy calibration of DSC. | Regular calibration is mandatory for data integrity and cross-lab comparability. |

| ASTM D648 / ISO 75 Standards | Definitive test protocols for determining the Heat Deflection Temperature of plastics [20] [21]. | Must be strictly followed to ensure results are valid and comparable to published data. |

Interrelationships and Research Implications

Understanding the relationships between Tg, Tm, and HDT is critical for polymer design. For semi-crystalline polymers, the gap between Tg and Tm defines the temperature window for processing operations like thermoforming. A material's HDT is not a fundamental property but a practical one that reflects the combined influence of stiffness (modulus) and the thermal transitions (Tg and Tm) on which that modulus depends [20]. For amorphous polymers, the HDT typically occurs close to or just above the Tg, as the drastic drop in modulus in the rubbery state leads to deformation under load. For semi-crystalline polymers, the HDT can be much closer to the Tm, as the crystalline lattice maintains stiffness well above Tg.

Diagram 2: Logical Relationship from Structure to Application

In drug development, this knowledge is applied precisely. A polymer for a surgical tool must have a Tg and HDT high enough to withstand repeated sterilization cycles (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C). Conversely, a polymer for a flexible catheter may require a Tg below body temperature to remain pliable. For drug delivery systems, the Tg of the polymer matrix can control the rate of drug release. Therefore, mastering these thermal properties enables researchers to rationally design, select, and process thermoplastic polymers to meet the demanding specifications of modern pharmaceutical and medical applications.

Thermoplastic polymers represent a cornerstone of modern material science, with their utility spanning from everyday consumer goods to critical applications in the automotive, aerospace, and healthcare industries [6]. The performance of these materials in demanding environments is governed by a complex interplay of their mechanical integrity—encompassing strength, stiffness, and toughness—and their chemical resistance to solvents and other aggressive media [23] [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these characteristics is not merely academic but fundamental to the rational design of components ranging from structural parts to advanced drug delivery systems [25] [26].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanical and chemical properties of thermoplastic polymers, framed within the context of ongoing research aimed at enhancing material performance through formulation, processing, and characterization. The objective is to bridge fundamental material properties with practical experimental methodologies, offering a technical guide that supports material selection and innovation in research and development.

Fundamental Thermoplastic Polymer Properties

Mechanical Characteristics

The mechanical behavior of thermoplastics under stress is characterized by several key properties. Strength is defined as the material's resistance to external stress, while stiffness (often measured as the modulus of elasticity) quantifies its resistance to deformation. Hardness indicates resistance to localized deformation, and toughness measures the energy a material can absorb before fracture, typically assessed via impact tests like Charpy or Izod [24]. These properties are not intrinsic but are profoundly influenced by the polymer's molecular structure, degree of crystallinity, and the presence of additives or reinforcements.

The addition of fillers and reinforcements, such as glass fibers (GF) or carbon fibers (CF), is a prevalent strategy for enhancing mechanical performance. These additives improve stiffness, strength, and creep resistance, particularly in engineering thermoplastics [6] [24]. For instance, in injection-molded samples, fiber reinforcement significantly boosts tensile and flexural strength, though the effect can be more limited in extruded forms [24]. Furthermore, the emergence of thermoplastic nanocomposites (TPNCs) has demonstrated that small loadings of nanoparticle fillers can substantially improve modulus, strength, durability, and thermal stability [6].

Chemical Resistance and Solvent Interaction

Chemical resistance describes a polymer's ability to withstand chemical attack or dissolution when exposed to solvents, oils, or other aggressive environments, which is critical for ensuring the safety and long-term reliability of plastic components [23]. The compatibility between a polymer and a solvent is governed by a complex interplay of chemical factors, including molecular structure, polarity, and molecular weight.

Theoretical frameworks for predicting chemical resistance and solubility are well-established. The Hildebrand solubility parameter (δ) provides a one-dimensional measure of solubility based on cohesive energy density, embodying the "like dissolves like" principle [25] [23]. This was later expanded by Hansen into Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP), which decompose the total solubility parameter into three components accounting for dispersion forces, polar interactions, and hydrogen bonding [25] [23]. The Flory-Huggins interaction parameter (χ) offers a thermodynamic framework based on statistical mechanics, where the mixing free energy of a polymer-solvent system is expressed using χ [23]. Lower values of χ generally indicate higher compatibility.

Recent advances have seen the application of machine learning to predict chemical resistance. Data-driven models can analyze over 2,200 polymer-solvent combinations, incorporating molecular descriptors from simulations and quantum chemical calculations to achieve generalizable and interpretable classification [23]. These models have identified that polymer crystallinity and density, along with solvent polarity, are key governing factors for chemical resistance [23].

Quantitative Analysis of Mechanical Properties

The mechanical performance of thermoplastics can be quantitatively compared using standardized test methods. The following tables summarize key properties for a selection of common engineering and high-performance thermoplastics, both unfilled and reinforced.

Table 1: Tensile and Flexural Properties of Selected Thermoplastics

| Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Tensile Modulus (MPa) | Flexural Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK (Unfilled) | 100 | 170 | 3,800 | 3,900 |

| PEEK (30% CF) | 205 | 295 | 18,000 | 16,500 |

| PA 6 (Unfilled) | 80 | 110 | 3,200 | 3,000 |

| PA 6 (30% GF) | 185 | 270 | 11,000 | 10,000 |

| POM-H | 70 | 95 | 3,100 | 2,900 |

| PET | 80 | 135 | 3,500 | 3,400 |

| PI (TECASINT 4111) | 120 | 170 | 3,200 | 3,300 |

Table 2: Toughness and Hardness of Selected Thermoplastics

| Material | Impact Strength, Notched (kJ/m²) | Ball Indentation Hardness (MPa) | Compressive Strength at 2% Deformation (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK (Unfilled) | 8.5 | 130 | 45 |

| PEEK (30% CF) | 10.5 | 180 | 105 |

| PA 6 (Unfilled) | 6.0 | 110 | 35 |

| PA 6 (30% GF) | 12.0 | 165 | 95 |

| POM-H | 7.5 | 125 | 40 |

| PET | 4.5 | 135 | 50 |

| PI (TECASINT 4111) | 9.5 | 140 | 120 |

Data derived from manufacturer specifications and standardized tests on specimens machined from semi-finished products [24]. The values are indicative and can vary based on specific grade, processing conditions, and testing standards. The tables illustrate the significant enhancement in mechanical properties achievable with fiber reinforcement. For instance, adding 30% carbon fiber to PEEK more than doubles its tensile strength and increases its tensile modulus by nearly a factor of five [24]. Similarly, glass fibers substantially improve the strength and stiffness of Polyamide 6 (PA 6). Notably, fiber reinforcement often also leads to improved toughness (impact strength) and hardness [24]. For compressive strength, it is important to note that for many ductile thermoplastics, a clear break point is not observed; therefore, the strength is often reported at a defined deformation (e.g., 2%) rather than at failure [24].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Rheological Characterization for Injection Molding

Accurate rheological data is crucial for simulating and optimizing injection molding processes. A novel, cost-effective procedure using a Melt Flow Index (MFI) tester, as an alternative to expensive capillary rheometers, has been developed for this purpose [27].

Procedure:

- Material Preparation: Dry the polymer (e.g., PA6GF30) at 80°C for 6 hours to remove moisture [27].

- MFI Testing: Using an MFI instrument (e.g., XNR-400C), load approximately 5 g of polymer into the barrel, pre-heated to the test temperature (e.g., 245°C, 260°C, 275°C). After a pre-heating period, apply a dead load to the piston. Measure the mass of polymer extruded in a specific time to calculate the mass flow rate [27].

- Initial Viscosity Curve: Generate initial viscosity vs. shear rate data points from the MFI test and fit them with a viscosity model (e.g., Cross-WLF) [27].

- Simulation-Driven Optimization: Develop a finite element model of the MFI test in simulation software (e.g., Autodesk Moldflow Insight). Couple this with an optimization platform (e.g., modeFRONTIER) to iteratively adjust the Cross-WLF parameters. The objective is to minimize the discrepancy between the simulated and experimental pressure values recorded during the MFI test [27].

- Validation: Compare the optimized viscosity curves with those obtained from a conventional capillary rheometer to validate the methodology [27].

This workflow integrates numerical simulation with experimental data to refine rheological models, providing a practical and accurate characterization method for industrial processors.

Diagram 1: Rheological characterization workflow

Assessing Drug-Polymer Miscibility in Solid Dispersions

In pharmaceutical research, understanding the miscibility of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) within a polymeric matrix is vital for creating stable amorphous solid dispersions, which can enhance the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs [25].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polymer (e.g., HPMCAS) and model drugs (e.g., Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Malonic Acid) in a suitable solvent mixture (e.g., Acetone/Chloroform 3:2 v/v) [25].

- Film Casting: Cast the solution onto a plate and allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature for at least one week to ensure complete drying and form a solid film [25].

- Solubility Parameter Calculation: Calculate the Hansen and Hildebrand solubility parameters for each drug and the polymer using group contribution methods to theoretically predict miscibility. Miscibility is generally predicted if the difference in solubility parameters (δ) is not greater than 7 MPa¹/² [25].

- Thermal Analysis: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to measure the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) of the pure polymer and the drug-polymer films. A single, composition-dependent Tg indicates miscibility, while multiple Tgs suggest phase separation [25].

- Phase Separation Analysis: Identify the API saturation concentration in the polymer matrix by observing the point at which further API addition leads to crystal formation and phase separation, as detected by techniques like X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [25].

Diagram 2: Drug-polymer miscibility assessment

Electrospinning for Orally Dispersible Films

Electrospinning is a versatile technique for creating nanofiber membranes with high surface area, suitable for drug delivery applications such as orally dispersible films (ODFs) [26].

Procedure:

- Polymer Blend Preparation: Prepare solutions with varying compositions of pharmaceutically applicable polymers (e.g., HPMC, PVP, PEG) and a model drug (e.g., Meloxicam) in a suitable solvent like Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) [26].

- Pre-electrospinning Characterization: Measure the viscosity and conductivity of the polymer solutions, as these properties significantly impact fiber formation [26].

- Needleless Electrospinning: Use a needleless electrospinning setup (e.g., using a cylindrical electrode) to produce nanofibers. Key parameters include the applied high voltage, distance between electrode and collector, and the rewinding speed of the collector substrate [26].

- Post-electrospinning Characterization:

- Morphology: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to analyze fiber diameter distribution and membrane morphology [26].

- Mechanical Properties: Test the tensile strength and elongation of the formed films [26].

- Disintegration and Dissolution: Assess the disintegration time of the ODFs and the drug release profile using standardized dissolution testing [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Research and Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hypromellose Acetate Succinate (HPMCAS) | A polymer carrier used in amorphous solid dispersions to enhance drug solubility and inhibit crystallization. | Drug-polymer miscibility studies for pharmaceutical formulations [25]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) & Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymers used in blends to formulate nanofiber membranes via electrospinning; impact fiber morphology and disintegration. | Production of orally dispersible films (ODFs) for drug delivery [26]. |

| Glass Fibers (GF) / Carbon Fibers (CF) | Reinforcing fillers added to polymer matrices to significantly improve mechanical strength, stiffness, and thermal stability. | Enhancing mechanical properties of engineering thermoplastics for structural applications [6] [24] [27]. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) | A theoretical framework to predict polymer-solvent miscibility and chemical resistance based on dispersion, polar, and hydrogen-bonding forces. | Screening polymer-solvent pairs for compatibility in processing and end-use applications [25] [23]. |

| Melt Flow Index (MFI) Tester | An instrument for measuring the melt flow rate of a polymer, providing a simple and cost-effective method for rheological quality control. | Initial rheological characterization and quality assurance of thermoplastic resins [27]. |

The mechanical and chemical characteristics of thermoplastic polymers are interdependent properties that can be systematically engineered through molecular design, blending, and the incorporation of fillers. The experimental protocols outlined—from advanced rheological characterization to the preparation of drug-loaded polymeric films—provide a robust framework for research and development. The growing integration of data-driven approaches, such as machine learning for predicting chemical resistance, is poised to accelerate the discovery and rational design of next-generation polymer materials [23]. For researchers and scientists, particularly in the field of drug development, a mastery of these principles and techniques is essential for innovating and optimizing polymeric materials to meet the complex demands of both existing and emerging applications.

Thermoplastic polymers represent a cornerstone of modern material science, characterized by linear or slightly branched polymer chains that soften upon heating and harden upon cooling, a process that is fully reversible and allows for recycling [28] [29]. This fundamental thermal behavior differentiates them from thermosetting plastics, which undergo an irreversible chemical curing process forming rigid, cross-linked networks [28]. Within the broad family of thermoplastics, materials are systematically classified into three primary categories based on their performance characteristics, thermal properties, and cost: commodity plastics, engineering plastics, and high-performance thermoplastics [30].

This classification framework is not merely academic; it provides an essential structure for researchers and development professionals to navigate the selection of polymeric materials for applications ranging from simple packaging to demanding roles in aerospace and precision drug delivery. The hierarchy ascends from cost-effective, high-volume commodities to specialized polymers capable of replacing traditional materials like metals and ceramics in extreme environments [31] [29]. Understanding the properties that define each category is crucial for aligning material choice with application requirements, particularly in scientific and industrial contexts where performance cannot be compromised.

Fundamental Classifications and Distinctions

Commodity Plastics

Commodity plastics are high-volume, low-cost polymers suitable for applications where exceptional mechanical or thermal properties are not critical [32]. They are mass-produced for single-use items and disposable products but also find use in durable goods where their specific properties are adequate [32] [29].

Key Characteristics:

- Cost: Low-cost materials, prioritizing economies of scale [32] [29].

- Production Volume: Mass-produced in extremely high volumes [32].

- Performance: Selected for adequate, non-critical mechanical properties rather than superior strength or thermal resistance [32] [29].

Table 1: Common Commodity Plastics and Their Applications

| Polymer | Key Applications | Notable Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | Plastic bags, packaging film [29] | Versatility, moisture resistance [33] |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Chairs, luggage, sterile bottles [29] | Robustness, chemical stress resistance [33] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Yogurt pots, CD cases, foam packaging [29] | Rigidity, thermal insulation [33] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Pipes, fittings, building profiles [33] | Weathering resistance, electrical insulation [33] |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Beverage bottles, synthetic fibers [29] | Clarity, strength-to-weight ratio, recyclability [33] |

Engineering Plastics

Engineering plastics are defined by their enhanced mechanical and thermal properties, making them suitable for use as load-bearing components, often replacing traditional materials like metal, wood, or glass [32] [34]. They are typically produced in lower volumes than commodity plastics and at a higher cost, justified by their performance in challenging environments [32].

Key Characteristics:

- Performance: High mechanical strength, heat resistance, chemical stability, and often self-lubrication [32].

- Cost: Significantly more expensive than commodity plastics [32] [29].

- Production Volume: Produced in lower, more specialized quantities [32].

Table 2: Common Engineering Plastics and Their Applications

| Polymer | Key Applications | Notable Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Polyamide (PA / Nylon) | Gears, bearings, clothing fibers [29] | Toughness, wear resistance [34] |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | Safety helmets, bullet-proof glazing, mobile phone casings [34] [29] | High impact resistance and toughness [34] |

| Polyoxymethylene (POM / Acetal) | Springs, gears, hinges [29] | High stiffness, low friction [34] |

| Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT) | Electrical components, computer keys [29] | Good electrical properties, dimensional stability |

| Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) | Children's toys, electronic casings [29] | Good impact resistance and surface finish |

High-Performance Thermoplastics

High-performance thermoplastics (HPTPs) represent the apex of thermoplastic polymer performance, designed to withstand extreme thermal, chemical, and mechanical stresses. These materials can tolerate continuous operating temperatures often exceeding 150°C and in some cases up to 260°C, filling critical roles in advanced industries [31] [35].

Key Characteristics:

- Thermal Resistance: Continuous use temperatures significantly higher than standard engineering plastics, typically above 150°C and up to 250°C [31] [35].

- Mechanical Properties: Retain high strength, stiffness, and creep resistance at elevated temperatures [31].

- Cost: Premium materials with high raw-material and compounding costs [35].

Table 3: High-Performance Thermoplastics and Their Applications

| Polymer | Key Applications | Notable Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | Piston parts, medical implants, aerospace components [31] [29] | Continuous use to ~260°C, high mech. strength, biocompatibility [31] [35] |

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | Aerospace, medical sterilizable tools [31] | High dielectric strength, flame resistance, steam sterilizable [31] |

| Polyphenylene Sulfide (PPS) | Chemical resistant parts, tight-tolerance components [31] | Excellent chemical resistance, dimensional stability [31] |

| Polyamide-imide (PAI) | Aerospace, oil & gas components [31] | Extreme compressive & impact strength, continuous use to ~250°C [31] |

| Polyimide (PI) | Aircraft/automobile structural parts [31] | High strength, low creep, excellent sliding characteristics [31] |

Molecular Structures and Thermal Properties

The properties of thermoplastics are fundamentally governed by their molecular architecture. Two primary molecular arrangements exist: amorphous and semi-crystalline [34] [30]. This distinction profoundly influences mechanical behavior, thermal transitions, and optical properties, and it is a critical consideration for researchers selecting materials for specific experimental or application conditions.

Molecular Structure and Property Relationships in Thermoplastics

Amorphous Polymers

Amorphous polymers possess a random, entangled arrangement of polymer chains, analogous to a plate of spaghetti [34]. This lack of order means they do not have a true melting point but instead soften gradually upon heating as they pass through the glass transition temperature (Tg). Below the Tg, the material is in a hard and rigid "glassy" state; above it, it enters a soft and flexible "rubbery" state [34]. This structure allows light to pass through with less scattering, making most amorphous polymers transparent or translucent [30]. They also exhibit lower shrinkage and warpage during processing compared to semi-crystalline polymers [30].

Semi-Crystalline Polymers

Semi-crystalline polymers feature a mixed morphology with densely packed, ordered crystalline regions surrounded by disordered amorphous regions [34]. This dual structure provides a sharp melting point (Tm) corresponding to the breakdown of crystalline domains. The crystalline regions act as physical cross-links, granting superior chemical resistance, creep resistance, and fatigue endurance [34] [30]. However, these ordered regions scatter light, rendering semi-crystalline polymers naturally opaque or translucent. They also experience greater and more anisotropic shrinkage during molding due to the crystallization process [30].

Table 4: Thermal Transition Temperatures of Selected Thermoplastics

| Polymer | Type | Glass Transition (Tg) | Melting Temperature (Tm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | Semi-crystalline | -10 °C | 175 °C [34] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Amorphous | 100 °C | - [34] |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | Amorphous | 150 °C | - [34] |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Semi-crystalline | 70 °C | 265 °C [34] |

| Nylon 6 (PA6) | Semi-crystalline | 50 °C | 215 °C [34] |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | Semi-crystalline | 145 °C | 335 °C [34] |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Thermal Analysis: DSC and TGA

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is a fundamental technique for characterizing thermal transitions.

- Purpose: To measure key thermal properties including glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm), crystallization temperature (Tc), and degree of crystallinity.

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-15 mg of polymer sample (film, pellet, or powder) into a standard aluminum crucible. Ensure good thermal contact by hermetically sealing the crucible. An empty, sealed crucible is used as a reference.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Purge the DSC cell with an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen at 50 mL/min).

- Execute a heat-cool-heat cycle: equilibrate at -50°C, heat to a temperature 30°C above the polymer's expected melt point at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min), hold isothermally for 5 minutes to erase thermal history, cool back to -50°C at 10°C/min, and finally reheat to the upper temperature limit at the same rate.

- Analyze the first heating cycle for the material's "as-received" thermal history, and the second heating cycle for its intrinsic properties without processing history.

- Data Analysis: The Tg is identified as a step-change in the heat flow curve. The Tm and crystallization exotherm (Tc) are identified as peak minima/maxima. The enthalpy of fusion (ΔHf) is calculated from the area under the melting peak, and the percentage crystallinity is determined by comparing ΔHf to the theoretical ΔHf for a 100% crystalline polymer.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) assesses thermal stability and composition.

- Purpose: To determine the thermal decomposition temperature, moisture content, filler content, and ash/residue content.

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 10-20 mg of sample into a platinum or alumina TGA pan.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Purge the system with an inert gas (N2) or air, depending on whether oxidative or inert stability is being tested.

- Heat the sample from room temperature to 800°C at a constant rate of 20°C/min.

- Monitor the mass change as a function of temperature.

- Data Analysis: The onset of decomposition is typically taken as the temperature at which 5% mass loss occurs. The residual mass at a high temperature (e.g., 600°C or 800°C) indicates the inorganic filler or ash content.

Mechanical Testing

Tensile Testing (according to ASTM D638 or ISO 527) evaluates fundamental mechanical properties.

- Purpose: To measure tensile strength, elongation at break, and elastic (Young's) modulus.

- Sample Preparation: Use standard dog-bone-shaped specimens, either injection molded or machined from plaques.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Mount the specimen in the tensile tester's grips.

- Apply a constant crosshead displacement rate (e.g., 5 or 50 mm/min, depending on material ductility) until the specimen fractures.

- Use an extensometer for accurate strain measurement.

- Data Analysis: The stress-strain curve is generated. The slope of the initial linear region gives the Young's Modulus. The maximum stress is the tensile strength, and the strain at specimen failure is the elongation at break.

Impact Testing (Izod or Charpy, per ASTM D256) assesses toughness and notch sensitivity.

- Purpose: To determine the energy absorbed by a notched specimen during a high-speed impact.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare bar specimens with a standardized notch machined into them.

- Experimental Protocol: A pendulum of known mass is released from a fixed height, striking and breaking the clamped (Izod) or simply supported (Charpy) specimen. The energy absorbed is calculated from the height the pendulum reaches after breaking the specimen.

- Data Analysis: Report the impact energy in Joules or ft-lb/in of notch.

Experimental Workflow for Thermoplastic Characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Thermoplastic Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum DSC Crucibles | Hermetically sealed containers for DSC sample analysis. | Ensure lids are crimped properly to prevent vapor loss and ensure good thermal contact [34]. |

| Inert Gas (N₂) | Purging atmosphere for DSC and TGA to prevent oxidative degradation. | Essential for obtaining accurate Tm and Tg values without decomposition artifacts [34]. |

| Tensile Test Specimen Mold | Produces standardized dog-bone shapes for mechanical testing (ASTM D638). | Critical for generating reproducible and comparable tensile property data. |

| Notching Tool | Creates a standardized notch for Izod/Charpy impact tests (ASTM D256). | A precise notch geometry is vital for obtaining accurate and reproducible impact energy values. |

| Polymer Standards | Certified reference materials for instrument calibration. | Used to verify the accuracy of DSC, TGA, and other analytical equipment. |

| Solvents (e.g., DMF, CHCl₃) | Dissolving polymers for solution casting or viscosity measurements. | Select solvent based on polymer solubility; e.g., DMF for polysulfones [35]. |

Advanced Applications: Engineered Polymers in Drug Delivery

The precision afforded by high-performance and engineered thermoplastics has catalyzed revolutionary advances in drug delivery. Engineered polymers form the backbone of controlled release systems, designed to maintain plasma drug concentration within a therapeutic window for prolonged periods, unlike conventional formulations which result in sharp peaks and troughs [36]. This is achieved through various platforms, including hydrogels, nano- and micro-particles, and polymer-drug conjugates [36].

A pivotal innovation in this field is the development of "smart" or stimuli-responsive polymers. These advanced materials can be engineered to respond to specific physiological or external triggers, leading to precise, pulsatile drug release [36]. These triggers include:

- Physical: Temperature, ultrasound, light, magnetic fields [36].

- Chemical: pH, ionic strength, redox potential [36].

- Biological: Specific enzyme concentrations or biomolecules [36].

For example, thermo-sensitive polymers like PNIPAAm or Pluronic (PEO/PPO) exhibit a Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST), transitioning from a solution to a gel state at body temperature, making them ideal injectable depots for proteins or hydrophobic drugs [36]. Similarly, pH-sensitive polymers, such as those containing poly(acrylic acid) groups, can be designed to release their payload specifically in the acidic environment of a tumor or the stomach [36]. The versatility of monomer combinations allows for the tuning of polymer sensitivity within a narrow range, enabling highly accurate and programmable drug delivery systems for precision medicine applications [36].