Understanding and Correcting Tg Prediction Outliers in Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and computational scientists working in drug development to identify, understand, and resolve outliers in glass transition temperature (Tg) predictions from molecular dynamics...

Understanding and Correcting Tg Prediction Outliers in Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and computational scientists working in drug development to identify, understand, and resolve outliers in glass transition temperature (Tg) predictions from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. It moves from fundamental theory through practical application, troubleshooting, and validation. Readers will gain a systematic approach to diagnosing problematic Tg calculations, implementing robust protocols, and critically validating their results against experimental data and other methods to enhance the reliability of their simulations for predicting material and polymer properties in pharmaceutical formulations.

What Are Tg Outliers? Understanding the Fundamentals of Glass Transition Predictions in MD

Defining the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) in Polymers and Amorphous Solids

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Why does my Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) measurement of Tg show multiple inflection points or an unusually broad transition? A: This is a common outlier. It often indicates residual solvent or water plasticizing the sample, insufficient annealing to erase thermal history, or a sample with a broad molecular weight distribution. Ensure your protocol includes: 1) Thorough drying in a vacuum oven at a temperature below Tg for >24 hours. 2) A controlled annealing cycle: Heat to ~Tg + 30°C, hold for 5-10 min, cool at 10°C/min to ~Tg - 50°C, then re-run the measurement scan.

Q2: In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, my predicted Tg is significantly higher/lower than the experimental value. What are the primary culprits? A: Tg prediction outliers in MD typically arise from:

- Force Field Inaccuracies: The chosen force field may poorly describe torsional barriers or van der Waals interactions for your specific polymer.

- Insufficient Equilibration: The glassy state configuration was not properly equilibrated above Tg before the cooling simulation.

- Excessively High Cooling Rate: Simulation cooling rates (often 10^10 - 10^12 K/s) are orders of magnitude faster than experiment (~10 K/min), leading to an artificially high Tg. Apply a correction model or extrapolate using simulations at multiple cooling rates.

Q3: How do I resolve discrepancies between Tg values from different techniques (e.g., DSC vs. DMA)? A: Different techniques probe different manifestations of the glass transition. DMA, sensitive to mechanical relaxation, often gives a Tg 5-20°C higher than DSC, which probes heat capacity change. Define your measurement conditions clearly: Table 1: Typical Tg Variation Across Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Probing Signal | Typical Heating/Cooling Rate | Tg Relative Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat Flow | 10°C/min | Baseline |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Loss Modulus (Tan δ peak) | 1-3°C/min | +5 to +20°C |

| Dilatometry | Specific Volume | ~1°C/min | Comparable to DSC |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Specific Volume vs. T | 10^10 K/s | Often +50 to +100°C |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Tg via DSC (ASTM E1356)

Objective: To measure the glass transition temperature of an amorphous polymer film using Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of material using a microbalance. Place in a hermetically sealed aluminum crucible. Ensure an identical, empty crucible is used as a reference.

- Loading: Place both crucibles in the DSC sample chamber under a nitrogen purge (flow rate: 50 mL/min).

- Thermal History Erasure: Run a first heating cycle from 25°C to Tg+30°C at a rate of 20°C/min. Hold for 5 minutes.

- Quenching: Cool rapidly from the melt to 25°C at the maximum instrument cooling rate (e.g., 100°C/min).

- Measurement Scan: Heat from 25°C to Tg+30°C at a standard rate of 10°C/min. This second scan is used for analysis.

- Data Analysis: Using the instrument software, plot heat flow vs. temperature. Identify the glass transition as a step change in heat capacity. The Tg is typically reported as the midpoint of the transition region between the extrapolated baselines.

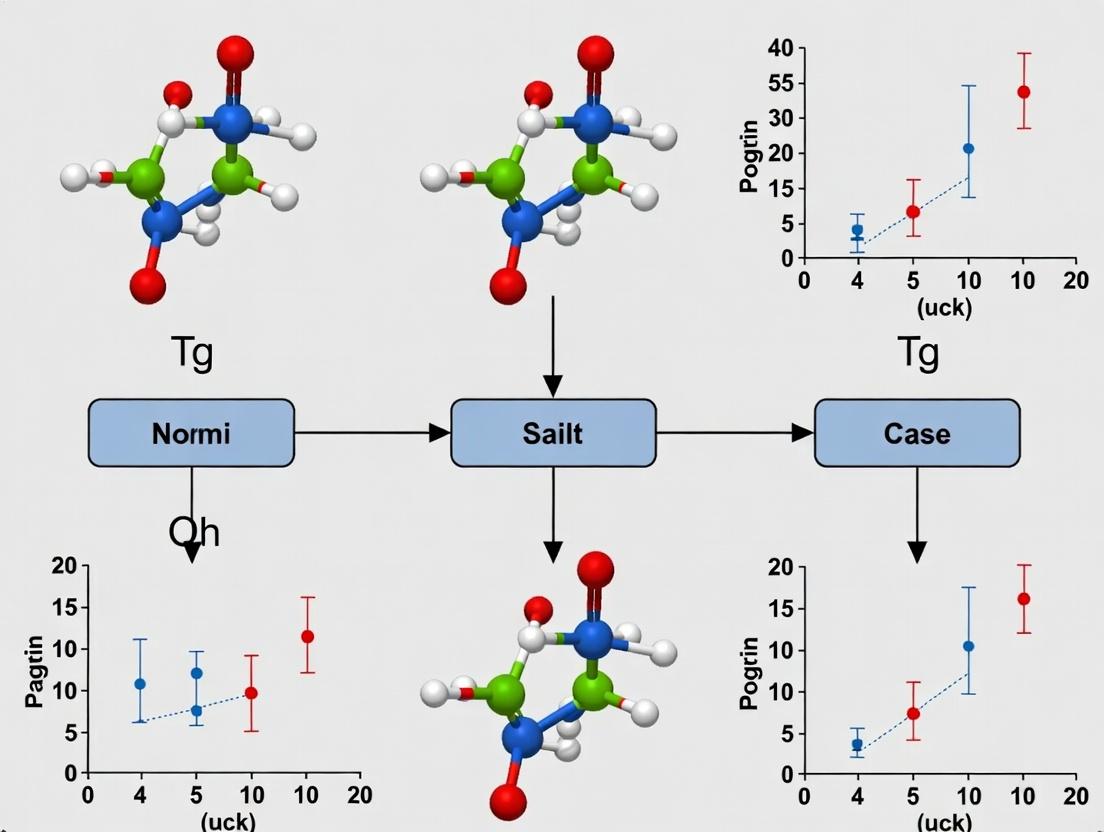

Key Diagram: MD Workflow for Tg Prediction

Title: MD Simulation Workflow for Tg Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions (Tg Determination)

Table 2: Essential Materials for Tg Experimentation

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hermetic DSC Crucibles | To contain sample, prevent solvent loss, and ensure good thermal contact. | Aluminum Tzero pans with lids (PerkinElmer). |

| High-Purity Inert Gas | Prevents oxidative degradation at high temperatures during measurement. | Nitrogen or Argon, 99.999% purity. |

| Calibration Standards | For accurate temperature and enthalpy calibration of the DSC. | Indium (Tm=156.6°C), Tin (Tm=231.9°C). |

| Microbalance | For precise sample weighing (5-20 mg range). | Analytical balance, 0.01 mg readability. |

| Vacuum Oven | For removing residual solvent and water prior to measurement. | Capable of <1 mbar and stable T control. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Platform for running Tg prediction simulations. | GROMACS, LAMMPS, Materials Studio. |

| Validated Force Field | The set of equations/parameters defining atomic interactions in MD. | OPLS-AA, PCFF+, CHARMM. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Necessary for running long, statistically significant MD simulations. | Multi-core CPUs/GPUs with high RAM. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Tg Prediction Outliers in MD Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My simulation consistently predicts a Tg that is 20-30K higher than the experimental value for my amorphous polymer. What are the most likely causes? A: This common outlier often stems from the force field or equilibration issues.

- Primary Cause (Force Field): Class II force fields (e.g., PCFF, CFF) or generic ones may overestimate cohesive energy density and chain stiffness. Solution: Switch to a force field specifically parameterized for glassy polymers or liquids (e.g., TraPPE, OPLS-AA with adjusted torsions). Validate on a small homologous system first.

- Secondary Cause (Quench Rate): The simulated cooling rate (

dT/dt) is typically >10^9 K/s, many orders of magnitude faster than experiment. Solution: While you cannot match experiment, perform a quench-rate study. Extrapolate Tg to a log-rate of ~1 K/min using the relationship:Tg = A - B * log(dT/dt). Use theAparameter as your rate-corrected prediction. - Protocol Check: Ensure volumetric or energetic data during cooling is fitted with two distinct linear regressions, not a continuous curve. The intersection point is Tg.

Q2: During the cooling run, my density-temperature plot shows high scatter/noise, making Tg determination ambiguous. How can I improve signal-to-noise? A: This indicates insufficient sampling or improper ensemble settings.

- Increase Averaging: The "property" (density or enthalpy) must be averaged over a time window that exceeds the alpha-relaxation time (

τα) near Tg. Asταgrows exponentially near Tg, your averaging window must too. A practical rule: average over the last 20-30% of each constant-temperature segment. - Adjust Ensemble: Use the NPT ensemble with a reliable barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman, Nosé-Hoover). Ensure pressure is correctly set (often 1 atm = 101.325 kPa). Anisotropic box scaling may be needed for certain phases.

- Replicate Runs: Perform 3-5 independent cooling runs from different equilibrated configurations. Plot the averaged property from all runs vs. temperature. The scatter will be significantly reduced.

Q3: How do I know if my initial amorphous cell is sufficiently equilibrated before beginning the cooling cycle? A: Inadequate initial equilibration is a major source of kinetic trapping and high Tg outliers.

- Key Metrics: Monitor:

- Energy Time Series: Potential energy must plateau.

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): Should show diffusive behavior (slope ~1 on log-log plot) for all chain segments.

- Radius of Gyration (

Rg): Must stabilize to a constant value characteristic of the chain chemistry.

- Protocol: After cell construction, run a multi-step equilibration:

- Minimization: Steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient.

- NVT Anneal: Cycle temperature (e.g., 300-500-300 K) to remove high-energy contacts.

- NPT Equilibration: Run at target starting temperature (e.g., 500 K) for a minimum time

t > 10 * τR(chain relaxation time). For many polymers, this requires >50-100 ns.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Tg Prediction is Too Low vs. Experiment

- Check 1: Force Field Repulsion/Dispersion Terms. Some force fields underestimate intermolecular interactions. Consider using a force field with explicit polarizability or Drude oscillators for polar polymers.

- Check 2: System Size. Your simulation box may be too small, suppressing long-wavelength density fluctuations critical for glass formation. Ensure box size > 2× the chain end-to-end distance.

- Check 3: Decomposition Analysis. Calculate the Tg from component-specific energy terms (van der Waals, electrostatic). If electrostatic Tg is much lower, your partial charge model may be inadequate.

Issue: Abrupt Change in Property, Not a Clear Intersection

- Check 1: Fitting Range. You may be fitting too close to the transition. Discard data points in the immediate transition region. Use only the clear high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) linear regions.

- Check 2: Phase Change. Confirm you have not accidentally crystallized your system. Monitor the radial distribution function

g(r)during cooling; a sharp, tall first peak indicates crystallization. If this occurs, your force field may over-favor ordered packing.

Table 1: Common Force Fields and Their Typical Tg Prediction Bias for Polystyrene (PS)

| Force Field | Class/Type | Typical Tg (K) for Atactic PS | Reported Bias vs. Exp. (~373 K) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCFF | Class II (CVFF-based) | 410 - 430 K | +35 to +55 K | Known to overestimate stiffness. |

| OPLS-AA | Class I (LJ + Harmonic) | 375 - 390 K | +2 to +17 K | Good balance; torsions may need scaling. |

| TraPPE-UA | United-atom, LJ | 370 - 380 K | -3 to +7 K | Excellent for hydrocarbons, lacks explicit polarizability. |

| GAFF | General AMBER | 360 - 375 K | -13 to +2 K | Variable performance; requires careful partial charge assignment. |

Table 2: Effect of Simulated Cooling Rate on Predicted Tg for a Generic Polymer Model

| Cooling Rate (K/ns) | Simulated Tg (K) | Extrapolated Tg at 1 K/min (K) | Simulation Length for 500K->200K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 312 | 285 | 3 ns |

| 10 | 328 | 289 | 30 ns |

| 1 | 345 | 293 | 300 ns |

| 0.1 | 358 | 295 | 3 µs |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tg Prediction via MD

Title: Protocol for Tg Determination via Volumetric Cooling in NPT MD.

Objective: To compute the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an amorphous polymer via molecular dynamics simulation by monitoring specific volume (V) vs. temperature (T).

Methodology:

- System Construction:

- Build an amorphous cell using a Monte Carlo packing algorithm (e.g., in Materials Studio, Packmol). Ensure a density ~10-15% below the expected rubbery state density at the starting high temperature.

- System Size: Minimum of 10 polymer chains with degree of polymerization > 40, or a box size exceeding 4×

Rg.

- Initial Equilibration (Critical):

- Minimization: Minimize energy using conjugate gradient algorithm until max force < 1.0 kcal/mol/Å.

- NVT Anneal: Heat system to 100 K above the expected Tg (e.g., 500 K). Run for 200 ps. Cycle: 500 K → 300 K → 500 K over 1 ns.

- NPT Equilibration: At the high starting temperature (500 K), equilibrate in the NPT ensemble (T = 500 K, P = 1 atm) using a Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat. Run until density plateaus and MSD shows linear diffusion. Minimum time: 50-100 ns.

- Cooling Simulation:

- Define a cooling schedule from the high T (e.g., 500 K) to low T (e.g., 200 K) in decrements of

ΔT= 10-20 K. - At each temperature

T_i, run an NPT simulation for a timet_i. Crucially,t_imust increase exponentially as T decreases (e.g., 2 ns at 500 K, 20 ns near Tg, 5 ns at 200 K). This accounts for slowing dynamics. - At each

T_i, compute the average specific volume over the last 30% oft_i. Record the average enthalpy if using energetic method.

- Define a cooling schedule from the high T (e.g., 500 K) to low T (e.g., 200 K) in decrements of

- Data Analysis:

- Plot

Vvs.T(orHvs.T). - Visually identify two linear regimes: the high-T rubbery state and the low-T glassy state.

- Perform independent linear fits to the data points in each regime. The intersection of the two regression lines is defined as

Tg. - Error Estimation: Perform 3 independent cooling runs from different equilibrated states. Report

Tgas mean ± standard deviation.

- Plot

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: MD Workflow for Tg Prediction

Title: Linear Fit Method for Tg Determination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Software for MD-based Tg Prediction

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded) for the polymer. Critical choice dictates accuracy. | OPLS-AA, TraPPE, CHARMM, GAFF. |

| Amorphous Cell Builder | Software to create realistic, initial disordered configurations of polymer chains at specified density. | Packmol, Amorphous Cell (Materials Studio), Moltemplate. |

| MD Engine | Core software that performs the numerical integration of equations of motion. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM. |

| Thermostat/Barostat | Algorithms to control temperature (T) and pressure (P) during NPT/NVT ensembles. Essential for correct dynamics. | Nosé-Hoover (T), Parrinello-Rahman (P), Berendsen (coupling). |

| Trajectory Analysis Tool | Software to analyze output trajectories: calculate density, RDF, MSD, energy. | VMD, MDAnalysis, MDTraj, in-built LAMMPS/GROMACS tools. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | MD simulations for Tg require long timescales (µs+). Parallel computing resources are essential. | Local cluster, Cloud (AWS, Azure), National supercomputing centers. |

Within the context of a broader thesis on Addressing Tg prediction outliers in molecular dynamics research, this technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers encountering aberrant glass transition temperature (Tg) predictions in their molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Outliers in Tg prediction can compromise the validity of studies in polymer science, material design, and drug development, where Tg is a critical parameter for stability and performance.

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My simulation predicts a Tg that is >50K different from the experimental value. What are the first steps I should take? A1: Immediately audit these three core components:

- Force Field Validation: Verify the force field parameters (e.g., OPLS-AA, CHARMM, GAFF) for your specific polymer or amorphous system against known benchmarks. Mismatched or poorly parameterized dihedrals are a primary culprit.

- Cooling Rate Artifact: The simulated cooling rate (typically 1-10 K/ns) is vastly faster than experiment. Extrapolate Tg by running simulations at multiple cooling rates and fitting to a logarithmic model (see Protocol 1).

- System Preparation: Ensure your initial amorphous cell is properly equilibrated. Check density convergence and potential energy stability over a lengthy NPT run prior to the cooling cycle.

Q2: What are common signs of a problematic Tg analysis during the simulation workflow? A2: Signs include:

- Non-linear Regions in Specific Volume vs. Temperature Plot: The high-T and low-T linear fits have very low R² values (<0.95), making the intersection point ambiguous.

- High Data Scatter: Excessive fluctuation in the volume or enthalpy data points, indicating insufficient averaging at each temperature step.

- Irreproducible Hysteresis: The Tg from the heating cycle differs from the cooling cycle by an anomalously large margin (>20K).

Guide 2: Correcting for Simulation Artefacts

Q3: How can I mitigate the effect of the unrealistic simulation cooling rate? A3: Implement a multi-rate protocol. Perform the cooling experiment at 3-4 different cooling rates (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 20 K/ns). Plot the observed Tg against the log of the cooling rate (log q). The linear fit can be extrapolated to experimental cooling rates (~1 K/min).

Q4: My system is large/complex, and a full multi-rate study is computationally prohibitive. Are there alternatives? A4: Yes, focus on enhancing statistical reliability at a single, slower cooling rate:

- Extend the simulation time at each temperature step (ensure properties are fully averaged).

- Replicate the experiment with 3-5 different initial configurations (different random seeds for packing) and report the mean Tg with standard deviation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the typical types of Tg outliers observed in MD studies? A: Outliers generally fall into three categories, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Common Types and Signs of Tg Prediction Outliers

| Outlier Type | Typical Sign | Potential Root Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Systematically High Tg | Predicted Tg is consistently 30-100K above experimental value across multiple runs. | Force field overestimates rotational energy barriers; Cooling rate not accounted for; System under-equilibrated (high initial stress). |

| Systematically Low Tg | Predicted Tg is consistently 20-80K below experimental value. | Force field underestimates intermolecular cohesion (e.g., vdW or electrostatic interactions); Incorrect system density. |

| Erratically Variable Tg | High run-to-run variation (>15K standard deviation) in predicted Tg for the same system. | Inadequate sampling/time averaging at each T step; Small system size amplifying finite-size effects; Poor initial configuration. |

Q: Which property (specific volume vs. enthalpy) is more reliable for Tg detection in simulation? A: Specific volume is the most common and generally robust. However, for systems with subtle conformational changes, enthalpy (total potential energy) can sometimes show a clearer transition. It is recommended to calculate both and compare the consistency of the derived Tg values.

Q: Are there specific bonded terms in the force field that most critically influence Tg prediction? A: Yes. Dihedral angle parameters governing backbone rotation are paramount. The table below lists key reagents and computational tools essential for troubleshooting.

Table 2: Research Reagent & Tool Solutions for Tg Outlier Analysis

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| GAFF2/OPLS-AA Force Fields | Standard force fields for organic molecules; validation against known benchmarks is crucial. |

| CP2K, GROMACS, LAMMPS | MD software packages with capabilities for constant pressure/temperature (NPT) cooling protocols. |

| VMD / PyMOL | Visualization software to inspect initial system packing and check for crystallization or voids. |

| Packmol / Pymatgen | Tools for building initial amorphous simulation cells with correct density and composition. |

| Python (MDAnalysis, NumPy) | For custom analysis scripts to calculate specific volume, enthalpy, and perform linear regression fits. |

| Glass Transition Benchmark Datasets | Curated experimental Tg data for common polymers (e.g., PS, PMMA) to validate simulation setup. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Cooling Rate Extrapolation Method

This protocol corrects for the inherent bias caused by ultra-fast simulation cooling rates.

- System Preparation: Build and equilibrate an amorphous system at 50-100K above the expected Tg (NPT ensemble, >1ns).

- Cooling Runs: Starting from the equilibrated high-temperature state, run 4 independent cooling simulations using a linear temperature ramp. Use rates of q = 20, 10, 5, and 1 K/ns.

- Property Calculation: For each run, calculate the specific volume (or enthalpy) averaged over the last 50% of the time at each temperature step.

- Tg Determination: For each cooling rate, plot property vs. T. Fit linear regressions to the high-T (ruby) and low-T (glass) data. Define Tg as the intersection point.

- Extrapolation: Plot the simulated Tg values against log₁₀(q). Perform a linear fit: Tg = m · log(q) + b. The y-intercept (b) approximates the Tg at an infinitely slow cooling rate, closer to experiment.

Protocol 2: Ensemble Averaging for Robust Tg Determination

This protocol improves the statistical reliability of a Tg prediction at a single cooling rate.

- Replicate Generation: Generate 5 statistically independent initial configurations (vary random seeds in packing software).

- Parallel Equilibration: Fully equilibrate each replicate system separately (NPT, target density, >2ns).

- Identical Cooling Protocol: Subject each replicate to the same cooling protocol (e.g., 5 K/ns from 500K to 200K).

- Analysis: Calculate Tg for each individual replicate using the specific volume method.

- Reporting: Report the mean Tg and the standard deviation across the 5 replicates. A large standard deviation (>10K) indicates high sensitivity to initial conditions or insufficient sampling.

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: Tg Simulation & Outlier Diagnosis Workflow

Diagram 2: Root Causes of Tg Outliers in MD Simulations

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Tg Prediction Outliers in MD Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our predicted glass transition temperature (Tg) for a polymer is consistently 20-30K higher than experimental values across multiple runs. What is the most likely primary cause? A1: This systematic positive outlier is most frequently linked to the force field. Classical force fields often overestimate cohesive energy densities and intermolecular interactions, particularly in non-bonded terms (e.g., van der Waals parameters). First, verify if your force field has been validated for Tg prediction. Consider switching to a force field specifically parameterized for condensed-phase properties or applying a correction, such as scaling down atomic charges.

Q2: When simulating the same amorphous drug formulation with different system sizes (500 vs. 10,000 molecules), we get significantly different Tg values. Which result should we trust? A2: The result from the larger system (10,000 molecules) is more reliable for bulk property prediction. Finite-size effects are a known source of variance. As a rule of thumb, the simulation box length should be at least twice the radius of gyration of your largest molecule. Use the larger system for your reported result and report the size-dependence as part of your error analysis.

Q3: We observe high variability (outliers) in Tg between simulation replicates using the same protocol. What step is most sensitive? A3: The cooling rate is the most sensitive step. MD simulations cool systems at rates orders of magnitude faster than experiments (e.g., 1 K/ns vs. 1 K/min). This can lead to poorly equilibrated glasses and high variability. Implement a stepwise cooling protocol with extended equilibration periods at each temperature, especially near the estimated Tg. While you cannot match experimental rates, using a slower, consistent simulated rate reduces replicate scatter.

Q4: How can we diagnose if an outlier Tg is due to inadequate equilibration of the melt phase before cooling? A4: Monitor the melt phase equilibration using:

- Convergence of potential energy and density over time.

- Mean squared displacement (MSD) to confirm the system has reached diffusive behavior.

- Structural metrics like radial distribution functions (RDFs) that stabilize. Insufficient melt equilibration propagates artificial order into the glass, causing Tg outliers. Extend the NPT equilibration until all metrics are stable.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Force Field-Induced Outliers

- Symptom: Consistent, directional bias (always too high/low) compared to experiment.

- Diagnosis: Compare density and enthalpy of vaporization at a reference temperature to experimental data. Large discrepancies (>5%) indicate force field issues.

- Solution: 1) Use a validated force field (see Toolkit). 2) Consider hybrid methods (e.g, machine-learned potentials) for initial screening. 3) If locked into a force field, document the bias as a systematic correction factor.

Issue: Cooling Rate Artifacts

- Symptom: High variability between replicates; Tg correlates with applied cooling rate.

- Diagnosis: Perform a "cooling rate study" (see Protocol 1).

- Solution: 1) Adopt a standardized, stepwise cooling protocol. 2) Extrapolate Tg to a "theoretical" infinitely slow cooling rate (see Table 1). 3) Always report the cooling rate used alongside Tg values.

Issue: Finite-Size Effects

- Symptom: Tg changes with the number of molecules (N) or box size (L).

- Diagnosis: Conduct a "finite-size scaling" study (see Protocol 2).

- Solution: 1) Plot Tg vs. 1/L; the y-intercept approximates the bulk value. 2) Use the largest computationally feasible system for production runs. 3. Apply periodic boundary condition corrections if available for your software.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cooling Rate Dependence Study

- Prepare System: Create a well-equilibrated, large (N>5000) melt system at T > Tg + 100K.

- Cooling Runs: Using the same melt configuration, initiate multiple independent cooling runs (NPT ensemble) at different rates (e.g., 10 K/ns, 1 K/ns, 0.1 K/ns).

- Data Collection: Record specific volume (V) or enthalpy (H) vs. Temperature (T) for each run.

- Analysis: Fit linear regressions to the liquid and glassy states of each V-T plot. The intersection defines Tg for that rate.

- Extrapolation: Plot Tg(rate) vs. log(cooling rate). Linear extrapolation to log(rate) → -∞ gives an estimated equilibrium Tg.

Protocol 2: System Size Scaling Analysis

- System Generation: Build chemically identical amorphous systems of varying sizes (e.g., N = 500, 1000, 2000, 5000, 10000 molecules).

- Consistent Protocol: Subject all systems to identical equilibration and cooling protocols (e.g., using the stepwise method from Protocol 1 at a fixed rate).

- Calculation: Calculate Tg for each system size.

- Finite-Size Plot: Plot the obtained Tg as a function of the inverse of the cubic root of the molecule count (proportional to 1/L).

- Bulk Estimation: Fit the data linearly; the y-intercept (1/L → 0) provides the estimate for the Tg of the infinite bulk system.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Cooling Rate on Predicted Tg for Amorphous Polystyrene (OPLS-AA FF)

| Cooling Rate (K/ns) | Predicted Tg (K) | Deviation from Expt. (ΔK)* |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 401 | +46 |

| 10 | 378 | +23 |

| 1 | 365 | +10 |

| 0.1 | 358 | +3 |

| Extrapolated to 0 | 355 ± 5 | ~0 |

*Experimental Tg ~ 355 K.

Table 2: Effect of System Size on Tg Prediction for a Model Polymer (Generic Data)

| Number of Chains | Atoms per Chain | Total System Size (atoms) | Predicted Tg (K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 100 | 500 | 382 |

| 10 | 100 | 1000 | 372 |

| 20 | 100 | 2000 | 365 |

| 50 | 100 | 5000 | 359 |

| 100 | 100 | 10000 | 356 |

| Bulk Estimate (Fit) | 353 ± 3 |

Diagrams

Title: Workflow for Cooling Rate Effect Analysis

Title: Diagnostic Map for Tg Outlier Sources

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Resource | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Condensed-Phase Optimized Force Fields | Parameterized for density, cohesion, and phase behavior; reduces systematic force field bias. | GAFF2, CGenFF, OPLS-AA (with validated modifications), COMPASS III. |

| Advanced Sampling Plugins | Facilitate slower effective cooling and better equilibration near Tg. | PLUMED (for metadynamics or bias-exchange), Infrequent Metadynamics. |

| Validated Tg Benchmark Datasets | Provide reference data for specific polymer/drug compounds to test force fields and protocols. | NIST’s Glass and Polymer Database, published datasets for PVP, PS, etc. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Enables larger system sizes (N > 10k atoms) and slower simulated cooling rates. | Cloud-based HPC (AWS, GCP) or national clusters; required for proper scaling studies. |

| Structure Analysis & Validation Suites | Automates checks for equilibration, density, and structural metrics. | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD/volutil, in-house scripts for MSD/RDF convergence. |

| Extrapolation & Analysis Scripts | Standardizes the analysis of V-T data and finite-size scaling. | Python/R scripts for robust linear fitting and Tg intersection finding. |

The Impact of Inaccurate Tg Predictions on Drug Stability and Formulation Design

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our molecular dynamics (MD) simulations consistently predict a Tg for our amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) that is 20-30°C higher than the experimental Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) measurement. What could be causing this overestimation? A: This common outlier often stems from force field inaccuracies. Classical force fields (e.g., GAFF, CGenFF) can overestimate intermolecular interaction strengths, particularly for hydrogen-bonding APIs and polymers. The simulated system may also be too small or the cooling rate in the simulation (often >10⁹ K/s) is vastly higher than experiment (~10 K/min), preventing proper equilibration.

Q2: When formulating a high-concentration protein therapeutic, how does an inaccurate Tg prediction affect our choice of stabilizers? A: An underestimated Tg can be catastrophic. If the predicted Tg is below the intended storage temperature (e.g., 4°C), you might incorrectly assume the formulation is in a stable, glassy state. In reality, it may be in a rubbery state, leading to rapid protein degradation via increased molecular mobility, aggregation, and chemical instability. This forces a re-evaluation of stabilizers (e.g., switching to disaccharides like trehalose over smaller polyols).

Q3: We observe phase separation in our ASD after 3 months of storage, but our MD-predicted Tg suggested good miscibility and stability. What went wrong? A: The Tg prediction likely came from a homogenous, equilibrated simulation model. In reality, nucleation and phase separation are kinetically driven processes that occur over long timescales. An accurate prediction requires not just the final Tg but an analysis of the Flory-Huggins interaction parameter (χ) from simulation trajectories and accelerated stability modeling. The Tg of the phase-separated domains will differ from the homogeneous blend.

Q4: Can machine learning (ML) models for Tg prediction be trusted for novel chemical entities in formulation design? A: ML models are powerful but context-dependent. They are reliable for interpolations within their training set (e.g., similar chemical scaffolds). For novel entities, they become extrapolative and can produce significant outliers. Always validate initial ML predictions with short, targeted MD simulations or experimental calibration using a representative subset of compounds.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Large Discrepancy Between Simulated and Experimental Tg

- Step 1: Verify Force Field Parameters. Cross-check partial atomic charges and torsion parameters for your specific API and polymer. Use quantum mechanics (QM) calculations (e.g., DFT) to derive accurate charges.

- Step 2: Check System Size and Equilibration. Ensure your simulation box contains enough molecules to be representative. Monitor density and potential energy during equilibration; they must plateau.

- Step 3: Analyze the Cooling Protocol. While you cannot match experimental rates, perform a sensitivity analysis. Simulate Tg using two different cooling rates (e.g., 1 K/ns and 10 K/ns) and extrapolate to experimental rates using the Vogel–Fulcher–Tammann relationship.

- Step 4: Validate with a Known System. Run a control simulation for a system with a known, published Tg (e.g., pure PVP) to calibrate your methodology.

Issue: Tg Prediction is Highly Variable Between Simulation Replicates

- Step 1: Increase Sampling. The glass transition is a statistical property. Run a minimum of 3-5 independent replicates starting from different initial configurations and velocities.

- Step 2: Refine the Tg Calculation Method. Do not rely on a single property. Calculate Tg concurrently from the change in slope of density, enthalpy, and mean squared displacement (MSD) vs. temperature. Use a robust fitting algorithm.

- Step 3: Ensure Proper Annealing. Before the cooling run, the system must be thoroughly annealed above the expected Tg to erase any previous history.

Table 1: Impact of Force Field Choice on Predicted Tg for Indomethacin

| Force Field | Predicted Tg (°C) | Experimental Tg (°C) | Absolute Error (°C) | Source/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF1 | 328 | 315 | +13 | Overestimates H-bond strength |

| GAFF2 | 319 | 315 | +4 | Improved torsion parameters |

| OPLS-AA | 310 | 315 | -5 | Slight underestimation |

| QM-Derived (Custom) | 316 | 315 | +1 | Best practice for novel APIs |

Table 2: Consequences of Tg Prediction Error on Formulation Stability

| Tg Prediction Error | Storage Temp. Relative to Actual Tg | Observed Stability Outcome (6 Months, Real-Time) | Corrective Formulation Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underestimation by 15°C | Storage > Actual Tg (Rubbery State) | >10% API Degradation, Crystal Growth | Increase polymer ratio, add secondary stabilizer |

| Accurate Prediction (±3°C) | Storage < Actual Tg (Glassy State) | <2% API Degradation, No Morphology Change | Proceed to clinical batch manufacturing |

| Overestimation by 10°C | Storage > Actual Tg (Unintended) | 5-8% Degradation, Phase Separation Observed | Reformulate with higher Tg polymer (e.g., PVP-VA instead of PVP) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Tg Predictions Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

- Sample Preparation: Place 3-5 mg of the amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) powder into a tared, hermetic aluminum DSC pan. Seal the pan crucially to prevent moisture loss.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- First Heat: Run a heating scan from 0°C to 20°C above the expected degradation temperature at a rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen purge (50 mL/min). This erases thermal history.

- Quench Cooling: Rapidly cool the sample to 0°C at the instrument's maximum rate (e.g., 50°C/min).

- Second Heat: Perform the analysis heating scan from 0°C to the temperature from step 3 at 10°C/min. The Tg is determined from the midpoint of the heat capacity change in this second scan using the instrument's software.

- Triplicate: Perform this protocol on three independently prepared samples.

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Tg Prediction

- System Building: Use Packmol or CHARMM-GUI to build an amorphous cell containing your API and polymer at the desired weight ratio. Ensure a minimum of 50-100 molecules total.

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the system energy using the steepest descent algorithm for 5000 steps to remove bad contacts.

- NVT & NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate first in the NVT ensemble at 500 K for 1 ns, then in the NPT ensemble at 500 K and 1 bar for 5 ns. Use a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Production Cooling Run: Using the equilibrated structure, run a simulated cooling scan. Decrease the temperature in increments of 20 K from 500 K to 200 K. At each temperature, run an NPT simulation for 2-5 ns (longer at lower T). Save trajectories every 10 ps.

- Data Analysis: For each temperature, calculate the average density and enthalpy from the last 1 ns of simulation. Plot these vs. temperature. Fit straight lines to the high-T (liquid) and low-T (glass) data. The intersection defines the simulated Tg.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Polymer (e.g., PVP-VA64) | The polymeric stabilizer in ASDs. Its chemical structure, molecular weight, and hygroscopicity directly influence the blend's Tg and miscibility. |

| Hermetic DSC Pans & Lids | Essential for experimental Tg measurement. Prevents moisture loss/uptake during heating, which can drastically alter the measured Tg. |

| Validated Force Field Parameters | Pre-derived, QM-validated parameters (charges, dihedrals) for your specific API. Critical for simulation accuracy; avoids "black box" generic parameters. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Open-source or commercial packages to perform the energy minimization, equilibration, cooling, and analysis simulations. |

| Quantum Mechanics Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Used to derive accurate electrostatic potential (ESP) charges and refine torsion parameters for novel molecules before MD simulation. |

| Stability Chamber | For validating predictions. Stores formulations at controlled T and %RH (e.g., 25°C/60%RH, 40°C/75%RH) to monitor physical stability over time. |

Best Practices: Robust Protocols for Tg Calculation and Analysis in Molecular Dynamics

This technical support center is framed within a thesis on Addressing Tg prediction outliers in molecular dynamics research. It provides troubleshooting and FAQs for the standardized simulation of glass transition temperature (Tg).

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My simulated Tg is consistently 20-30% higher than the experimental value. What are the most likely causes? A: This is a common outlier. Primary causes include:

- Force Field Inaccuracy: The chosen force field may overestimate cohesive energy density or chain rigidity. Switch to a force field specifically parameterized for glassy polymers (e.g., all-atom OPLS vs. generic CG models).

- Excessively Fast Cooling Rate: Computational limits force cooling rates (~1010–1012 K/s) far exceeding experiment (~1 K/s). This traps the system in a higher-energy state, overestimating Tg. Mitigation: Extrapolate Tg to experimental cooling rates using the relationship in Table 1.

- Insufficient Equilibration Above Tg: The melt phase is not fully relaxed. Ensure the mean squared displacement (MSD) plateaus at a value >> (chain end-to-end distance)2 before cooling begins.

Q2: During the cooling run, the density vs. temperature curve shows a sudden "jump" instead of a smooth, bilinear transition. How can I fix this? A: This indicates a first-order phase transition artifact, not a glass transition.

- Cause: The system size is too small, or the temperature decrements (dT) are too large.

- Solution: Reduce the cooling step

dT(e.g., from 20 K to 5-10 K) and increase the simulation time at each temperature. For amorphous polymers, a box size containing >3 entanglement lengths is recommended.

Q3: What is the minimum acceptable simulation time at each temperature step during the cooling stage? A: There is no universal minimum, but a robust guideline is to simulate for at least 10-20 times the longest relaxation time (τ)* of your polymer at that temperature. Since τ increases dramatically near Tg, use time-temperature superposition principles. A practical check: volume/density must reach a stable plateau at each step before proceeding to the next lower temperature. See Table 2 for protocol specifics.

Q4: How do I rigorously define Tg from the simulation data (V vs. T)? A: Avoid subjective linear fits. Use a standardized analysis:

- Fit the high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) data points with separate linear regressions.

- Use a least-squares fitting algorithm to find the intersection point of these two lines. This intersection temperature is your simulated Tg.

- Report the correlation coefficient (R²) for both fits; values below 0.98 indicate poor linear regimes and unreliable Tg.

Data Tables

Table 1: Impact of Cooling Rate on Simulated Tg for Atactic Polystyrene (Example)

| Cooling Rate (K/s) | Simulated Tg (K) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 x 1012 | 450 ± 15 | Common in standard MD. High outlier. |

| 1 x 1011 | 425 ± 10 | Achievable with longer runs. |

| 1 x 1010 | 410 ± 8 | Requires extensive computing. |

| Extrapolated to 1 (Expt.) | ~375 | Close to experimental ~373 K. |

Table 2: Standardized Protocol Summary

| Stage | Key Parameters | Success Criteria | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Equilibration (Melt) | NPT, T > Tg+100K, ~100-200 ns. | MSD > (2*Ree)²; energy & density stable. | Starting from crystalline structure. |

| 2. Cooling | NPT, dT = 5-10 K, 2-10 ns/step. | Smooth V vs. T plot; plateau at each T. | dT too large; time/step too short. |

| 3. Analysis | Bilinear fit of V vs. T; intersection. | High R² (>0.98) for both linear regimes. | Subjectively choosing fit regions. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed TgSimulation Methodology

1. System Preparation & Equilibration:

- Build an amorphous cell with sufficient chains (e.g., 10-20 chains) to avoid size effects.

- Perform energy minimization (steepest descent/conjugate gradient) until Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- Equilibrate in the NVT ensemble (e.g., 298 K, 100 ps) using a Berendsen thermostat.

- Equilibrate in the NPT ensemble (T > Tg+100K, 1 atm, 100-200 ns) using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat and Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Monitor density and radius of gyration for stability.

2. Stepwise Cooling Protocol:

- Starting from the equilibrated melt, decrease temperature by increments

dT(e.g., 10 K). - At each new temperature, run an NPT simulation for a duration sufficient for property equilibration (see Q3). Typical times range from 2 ns (high T) to 10 ns (near Tg).

- Record the average specific volume (or density) for the last 50% of the simulation at each temperature step.

- Continue cooling until well below the expected Tg (e.g., Tg - 100K).

3. Data Analysis for Tg:

- Plot specific volume (V) vs. temperature (T) for all steps.

- Visually identify the high-temperature (rubbery) and low-temperature (glassy) linear regions.

- Perform linear regressions on these two distinct data sets.

- Calculate the intersection point of the two regression lines. The temperature at this point is the simulated Tg.

Diagrams

Workflow for Simulating Glass Transition Temperature

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg Simulation |

|---|---|

| All-Atom Force Fields (e.g., GAFF2, OPLS-AA) | Provides accurate parameters for bonding and non-bonded interactions specific to organic polymers. Critical for realistic density and dynamics. |

| Coarse-Grained Force Fields (e.g., MARTINI) | Allows simulation of longer time/length scales by grouping atoms into beads. Useful for large systems but may reduce Tg accuracy. |

| Validated Polymer Libraries (e.g., PolyParGen) | Provides correct initial topology, chirality (tacticity), and molecular weight distributions for building realistic amorphous cells. |

| Advanced Thermostats (Nosé-Hoover, Langevin) | Generates correct canonical (NVT) ensemble statistics, crucial for accurate temperature control during equilibration and cooling. |

| Advanced Barostats (Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen) | Maintains correct isotropic pressure (NPT ensemble), essential for obtaining correct density and specific volume. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software (MDAnalysis, VMD) | Used to calculate key properties: mean squared displacement (MSD), radial distribution function (RDF), density, and specific volume over time. |

Choosing and Validating Force Fields for Accurate Polymer and Small Molecule Behavior

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common issues encountered when selecting and validating force fields for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, specifically within the context of a thesis on Addressing Tg prediction outliers in molecular dynamics research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My calculated glass transition temperature (Tg) for a common polymer like polystyrene is consistently 20-30K higher than the experimental value, regardless of the cooling rate I use. What is the primary culprit?

A: This is a classic force field parameterization issue. Many older, all-atom force fields (e.g., standard OPLS-AA, CHARMM27) were parameterized to reproduce liquid-state and room-temperature properties, often leading to over-stabilization of the glassy state and inflated Tg. The root cause is frequently an imbalance in torsional potential parameters or van der Waals (vdW) interactions. Switch to a force field specifically refined for polymer properties, such as OPLS-AA with CM1A/B charges and reparameterized dihedrals, or the newer TraPPE force field variants for polymers. Validation should start with density and cohesive energy density at room temperature before proceeding to Tg prediction.

Q2: When simulating small molecule organics in a polymer matrix, my results show excessive aggregation or unrealistic diffusion. What steps should I take to diagnose the problem?

A: This typically indicates a mismatch between the force fields for the two components. First, ensure cross-interaction parameters (vdW, specifically Lennard-Jones ε and σ) are compatible. Use combining rules (Lorentz-Berthelot are common) but be aware they are a major source of error. To troubleshoot:

- Check the pure-component densities of both the small molecule and polymer using their respective force fields independently.

- Calculate the Flory-Huggins χ parameter from simulation and compare to experimental solubility data.

- If mismatch persists, consider deriving cross-interaction parameters via ab initio calculations on model complexes or using a force field from a unified family (e.g., GAFF2 for both components) with careful partial charge assignment (e.g., via HF/6-31G* RESP fitting).

Q3: I am getting unphysical chain entanglements or anomalous chain dynamics during equilibration. How can I verify my equilibration protocol is sufficient?

A: Unphysical entanglements often stem from a poor initial configuration or insufficient equilibration. Follow this protocol:

- Initialization: Use a simulated polymerization or a self-avoiding random walk algorithm, not simple random placement.

- Equilibration Cascade:

- Run a long NVT simulation at high temperature (e.g., 600-1000 K) with a weak coupling thermostat to randomize chain conformations.

- Cool gradually to the target temperature under NPT conditions.

- Monitor the radius of gyration (Rg), end-to-end distance, and mean squared displacement (MSD) of chain centers of mass. These must plateau.

- For dense melts, the equilibration is complete when the chains' MSD exceeds their own mean squared radius of gyration (Rg²). Use the following table as a benchmark for plateau values:

Table 1: Key Equilibration Metrics for a Polyethylene (PE) Melt (C100H202)

| Metric | Un-Equilibrated State Value | Equilibrated State (Plateau) Value | Simulation Conditions (NPT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ~0.78 - 0.85 | 0.855 ± 0.005 | 500 K, 1 atm, TraPPE-UA |

| Rg (Å) | Drifting or non-Gaussian distribution | Stable, Gaussian distribution (~27 Å) | 500 K, 1 atm |

| MSD (Ų) | Sub-diffusive (slope <1 on log-log) | Diffusive (slope ~1) for CM motion | 500 K, 1 atm |

Experimental Protocol: Tg Determination via Specific Volume vs. Temperature

- Objective: To determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an amorphous polymer via MD simulation.

- Force Field Validation Context: This protocol is used to validate or refute a force field's ability to capture the change in thermal expansion coefficient at Tg.

- Procedure:

- System Preparation: Build an amorphous cell with ~10-20 polymer chains (degree of polymerization > 40) using Packmol or similar.

- High-T Equilibration: Run a multi-nanosecond NPT simulation at T > Tg + 100K to fully equilibrate and randomize chains. Ensure density stabilizes.

- Stepwise Cooling: Using the final configuration from step 2, initiate a series of independent NPT simulations (or a slow continuous cooling run). For highest accuracy, use 10K intervals. At each temperature, simulate for a time sufficient for the polymer melt to relax (e.g., 10-50 ns per point). The total simulation time must exceed the longest Rouse time of the chain.

- Data Collection: Record the specific volume (or density) from the equilibrated portion of each temperature simulation.

- Analysis: Plot specific volume vs. Temperature. Fit two linear regressions—one to the high-temperature (rubbery) data points and one to the low-temperature (glassy) data points. The intersection of these two lines is defined as the simulated Tg.

- Critical Note: The calculated Tg will have a strong cooling rate dependence. Extrapolation to experimental cooling rates (1-10 K/min) requires performing this protocol at multiple simulation cooling rates and extrapolating.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Force Field Validation Studies

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Force Fields: OPLS-AA/L, CGenFF, GAFF2, TraPPE | Provides the functional form and parameters (bond, angle, dihedral, non-bonded) governing interatomic interactions. Selection is critical for target properties. |

| Partial Charge Derivation: RESP, CM5, DDEC | Methods to assign atomic partial charges, crucial for electrostatic interactions. HF/6-31G* RESP is a common standard for organic molecules. |

| Ab Initio Software: Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS | Used for quantum mechanical calculations to parameterize torsions, derive charges, and calculate interaction energies for force field validation/refinement. |

| MD Engines: GROMACS, LAMMPS, OpenMM, AMBER | Core simulation software to perform energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs. |

| Analysis Suites: MDTraj, VMD, MDAnalysis, in-house scripts | For processing trajectory data to calculate properties like Rg, density, MSD, and cohesive energy density. |

| Validation Databases: NIST ThermoML, PubChem, Polyply | Experimental data repositories for density, enthalpy of vaporization, etc., used as benchmarks for force field validation. |

Diagrams

Title: Force Field Selection and Validation Workflow

Title: MD Protocol for Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Tg Prediction Outliers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my predicted Tg value change dramatically when I slightly modify the cooling rate? A: The cooling rate in MD simulations is often many orders of magnitude faster than experimental rates. A small change in simulation cooling rate (e.g., from 1 K/ns to 0.5 K/ns) can lead to large, non-linear shifts in the extrapolated Tg. This is a primary source of systematic error. Use multiple, widely spaced cooling rates (e.g., 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25 K/ns) to enable robust extrapolation to experimental rates.

Q2: My system size appears adequate, but my Tg prediction still has high uncertainty. What could be wrong? A: An "adequate" size for structural properties may be insufficient for reliable thermodynamic averaging near Tg. Ensure your system size is validated by checking for convergence of Tg with increasing number of molecules or chain lengths. For polymers, the chain length must exceed the entanglement length.

Q3: How can I determine if my simulation time is sufficient for equilibration at low temperatures? A: Insufficient equilibration below Tg is a major cause of outliers. Use the following protocol: 1) Monitor the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the backbone atoms; it should plateau. 2) Track the potential energy; it must reach a stable plateau. 3) Perform the test twice as long; key properties (density, energy) should not drift.

Q4: My Tg prediction is consistently higher than the experimental value. Which parameter should I investigate first? A: Investigate the cooling rate first. Excessively high simulation cooling rates are the most common cause of overestimated Tg. Implement a cooling rate extrapolation protocol to correct for this inherent artifact of MD timescales.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Tg Value is Not Converging with System Size Symptoms: Tg values show significant variation (>10 K difference) when the number of molecules or polymer repeat units is increased. Diagnostic Steps:

- Run a series of simulations with increasing system size (e.g., 20, 40, 80, 160 molecules).

- For each system, perform an identical cooling protocol.

- Plot Tg vs. 1/N (where N is the number of molecules or degree of polymerization). Solution: Extrapolate the Tg to the thermodynamic limit (1/N -> 0). Use the system size where the Tg change is within your desired error margin (e.g., < 2 K).

Issue: High Sensitivity to Cooling Rate Leading to Unphysical Tg Symptoms: Minor changes in the cooling schedule produce wild Tg swings, making prediction unreliable. Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify that each cooling step is long enough for equilibration. Use the MSD/energy plateau test from FAQ Q3 at multiple temperatures.

- Ensure the property used to detect Tg (density, enthalpy, etc.) is averaged over a sufficiently long production run after equilibration. Solution: Adopt a multi-rate protocol. The table below provides a standard framework.

Table 1: Effect of Simulation Parameters on Tg Prediction for a Model Amorphous Polymer (e.g., Polystyrene)

| Parameter | Typical Range in MD | Impact on Predicted Tg | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Rate | 0.1 - 100 K/ns | Increases Tg by 10-50 K per decade increase in rate. | Extrapolate using rates spanning at least 2 orders of magnitude. |

| System Size (N chains) | 1 - 100 chains | Tg decreases by 5-20 K as N increases from 1 to ~50, then plateaus. | Use N > 50 for short chains; validate via 1/N extrapolation. |

| Simulation Time per T | 0.1 - 10 ns | < 2 ns leads to poor equilibration & overestimated Tg. | Ensure MSD plateau; minimum 5-10 ns near and below Tg. |

| Total Simulation Time | 10 - 1000 ns | Shorter times increase statistical error and equilibration artifacts. | Aim for >200 ns total for a full cooling scan. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions (Computational Toolkit)

| Item | Function in Tg Prediction |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD) | Core software for performing the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. |

| All-Atom Force Field (e.g., CHARMM36, GAFF2, OPLS-AA) | Defines the potential energy function (bonded/non-bonded terms) governing interatomic interactions. Critical for accurate density and dynamics. |

| Polymer Topology Generator (e.g., polyply, CHARMM-GUI Polymer Builder) | Creates realistic, equilibrated initial configurations of amorphous polymer melts, reducing initial configuration bias. |

| Thermodynamic Analysis Tool (e.g., VMD, MDAnalysis, in-house scripts) | Used to calculate density, enthalpy, and specific volume from trajectory data for Tg determination. |

| Glass Transition Analysis Script | Custom or published script to fit the simulated data (e.g., density vs. T) with two linear regressions and identify the intersection point (Tg). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Cooling Rate Extrapolation for Tg Prediction

- Initialization: Prepare an equilibrated amorphous system at a temperature well above the expected Tg (e.g., T > Tg + 100 K).

- Cooling Schedules: Define at least four distinct cooling rates (e.g., R1=5 K/ns, R2=1 K/ns, R3=0.2 K/ns, R4=0.04 K/ns).

- Simulation: For each rate, cool the system linearly from the high temperature to a low temperature (e.g., Tg - 100 K). Use an NPT ensemble. Ensure each temperature step is held constant for a time long enough for equilibration (validate via energy/ MSD).

- Property Calculation: For each cooling run, calculate the specific volume (or enthalpy) as a function of temperature.

- Tg Determination: For each individual cooling run, fit the high-T and low-T linear regions of the property vs. T plot. The intersection defines Tg(sim, R).

- Extrapolation: Plot Tg(sim, R) vs. log(R). Fit the data points linearly. Extrapolate to the experimental cooling rate (e.g., log(R) ≈ -10 to -12 for R in K/s). The y-intercept at the experimental log(R) is the predicted Tg.

Protocol 2: System Size Convergence Test

- System Generation: Build a series of systems with identical chemistry but increasing size (e.g., 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 polymer chains, each of the same length).

- Equilibration: Equilibrate each system independently at the same high temperature using an NPT ensemble until density stabilizes. Larger systems may require longer equilibration.

- Identical Cooling Protocol: Subject each system to the same cooling protocol (e.g., 1 K/ns).

- Analysis: Calculate Tg for each system using Protocol 1, steps 4-5.

- Convergence Check: Plot Tg vs. 1/(Number of Chains). The Tg is considered converged when the value changes by less than the target uncertainty (e.g., ±2 K) with increasing system size.

Visualization of Methodologies

Diagram Title: Workflow for Cooling Rate Extrapolation to Predict Tg

Diagram Title: System Size Convergence Test Workflow for Tg

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My specific volume vs. temperature (V-T) data is too noisy, leading to poor curve fits. How can I improve data quality? A: High noise often stems from insufficient system equilibration or poor pressure control.

- Protocol: Before production runs, extend the NPT equilibration phase. Monitor the potential energy and pressure until they plateau (typically for 5-10 ns). Use a robust barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) with a time constant of 5-10 times your simulation timestep.

- Data Solution: Apply a moving average filter (window size of 5-10 data points) to the raw V-T data before fitting. Ensure your simulation replicates (n≥3) are independent (different random seeds).

Q2: How do I objectively identify the glass transition temperature (Tg) from the fitted curve, rather than visually estimating the intersection? A: Visual estimation introduces subjectivity. Use a piecewise linear regression fit.

- Protocol: Fit your V(T) data to two separate linear regressions. Use an iterative algorithm to vary the breakpoint (T) and minimize the total residual sum of squares. The breakpoint with the lowest total error is the objectively determined Tg. Statistical F-tests can confirm the significance of the two-segment model over a single line.

- Data Solution: See Table 1 for a comparison of Tg determination methods.

Q3: My MD-predicted Tg is a significant outlier compared to experimental DSC values. What are the primary causes? A: This core thesis issue typically arises from force field inaccuracies or unrealistic cooling rates.

- Protocol: Validate your force field by simulating density at room temperature against known experimental data first. If Tg is an outlier, consider using a force field with refined torsional parameters or polarizable models. Acknowledge that MD cooling rates (~10¹⁰ K/s) are vastly faster than experiment (~10⁻¹ K/s). Use the relationship

Tg = A * log(q) + Bto extrapolate to experimental rates. - Data Solution: See Table 2 for common outliers and corrective actions.

Q4: The low-temperature (glassy) region shows unexpected curvature, making linear fit difficult. A: This indicates the system may not have reached a true glassy state or has residual relaxation.

- Protocol: Increase the simulation time at each low-temperature step. The "glass" should be in a non-equilibrium, metastable state. If curvature persists, your cooling rate may still be too fast for the system size; consider a slower cooling protocol or analyze data from lower temperatures where volume change is truly linear.

Q5: Are there specific MD packages or analysis tools best suited for this protocol? A: While most major packages (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS) can perform the simulation, analysis requires custom scripts.

- Toolkit: Use

gmx energy(GROMACS) orcpptraj(AMBER) to extract specific volume data. For robust piecewise fitting, use scientific libraries likeSciPy(Python) orlmfit(Python) which offer breakpoint models.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Tg Identification Methods

| Method | Description | Advantage | Disadvantage | Susceptibility to Outlier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Intersection | Manual drawing of linear fits. | Simple, intuitive. | Highly subjective, not reproducible. | Very High |

| Piecewise Linear Regression | Algorithmic minimization of residuals for two lines. | Objective, reproducible, provides error estimates. | Assumes two distinct linear regimes. | Low (with robust fitting) |

| Derivative Analysis | Finding peak in dV/dT vs. T curve. | Single, automated point. | Amplifies data noise, requires smoothing. | Medium |

Table 2: Common Tg Outliers in MD and Corrective Actions

| Outlier Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Experiment/Action |

|---|---|---|

| Tg consistently too low | Force field underpolymer chain stiffness / barrier. | Switch to a force field with validated torsional potentials (e.g., C22/i, OPLS-AA/M). |

| Tg consistently too high | Force field overestimates intermolecular interactions. | Adjust non-bonded interaction parameters (e.g., LJ epsilon) based on ab initio data. |

| Unphysically large Tg spread between replicates | Inadequate equilibration, system too small. | Increase equilibration time, use larger system (≥10 oligomer chains). |

| Tg prediction is rate-insensitive | Cooling window too narrow or rate variation too small. | Perform simulations over a wider range of cooling rates (e.g., 0.01 to 1 K/ns) for extrapolation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Tg Prediction

- System Preparation: Build an amorphous cell of 10-20 polymer/drug molecules using PACKMOL or CHARMM-GUI.

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent algorithm for 5000 steps to remove bad contacts.

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate at 500 K for 2 ns (Berendsen thermostat) to randomize configuration.

- NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate at 500 K and 1 atm for 5 ns (Parrinello-Rahman barostat) to stabilize density.

- Cooling Run: Using NPT ensemble, cool the system linearly from 500 K to 100 K in decrements of 10-20 K. Hold at each temperature for 2-5 ns, with the final 1 ns used for production data (specific volume).

- Data Collection: Output the density (ρ) at each temperature. Calculate specific volume as V = 1/ρ.

- Analysis: Perform piecewise linear regression on V vs. T data. The breakpoint is Tg.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram Title: MD Simulation & Analysis Workflow for Tg

Diagram Title: Tg Outlier Diagnostic Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Tg Prediction Experiment |

|---|---|

| Validated Force Field (e.g., GAFF2, C36, OPLS-AA/M) | Provides the mathematical potential functions governing atomic interactions; accuracy is critical for predicting material properties like density and Tg. |

| Molecular System Builder (PACKMOL, CHARMM-GUI) | Creates initial, random configurations of the amorphous polymer or drug system for simulation. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs long-timescale (100s of ns) cooling simulations with adequate sampling in a feasible time. |

| MD Engine (GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS) | Software that performs the numerical integration of equations of motion to simulate the system's evolution over time. |

| Robust Barostat (Parrinello-Rahman, Martyna-Tobias-Klein) | Algorithm controlling pressure during NPT simulations; essential for obtaining correct density and specific volume. |

| Data Analysis Library (SciPy, NumPy, pandas) | Python libraries used to process trajectory data, perform statistical analysis, and execute the piecewise linear regression fit. |

| Visualization Tool (VMD, PyMOL) | Used to inspect the simulated system for homogeneity, artifacts, and to confirm the amorphous state. |

Automating Workflows for High-Throughput Tg Screening of Candidate Materials

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Our automated Tg calculation script returns 'NaN' for many simulations. What is the most common cause? A1: The most frequent cause is insufficient equilibration of the glassy state or a poor fit of the specific volume vs. temperature data. Ensure the cooling protocol in your MD simulation reaches a sufficiently low temperature (e.g., well below the expected Tg) and that the production run for the quenched glass is long enough to achieve stable density. Check the R² value of the linear fits to the rubbery and glassy states; a low R² for the glassy line often indicates non-equilibrium.

Q2: We observe significant Tg outliers (>50K deviation from experimental data) in a batch of polymer candidates. Where should we start troubleshooting? A2: First, verify the force field parameters. Outliers often originate from inaccurate torsion potentials or van der Waals parameters for specific functional groups. Cross-reference with the latest parameter development publications for your material class (e.g., CGenFF, OPLS-4, GAFF2). Second, inspect the simulated cooling rate. A standard 1 K/ns rate can yield a Tg 50-100K higher than experiment. While absolute match is difficult, consistency is key. Use a consistent, documented cooling rate and note that the predicted Tg is rate-dependent.

Q3: During high-throughput screening, how do we handle simulations that fail to vitrify, remaining in a supercooled liquid state? A3: Implement a pre-screening check for the slope of the specific volume vs. T curve at the lowest simulated temperature. If the slope is greater than a defined threshold (e.g., > 1.5e-4 cm³/g/K), the system may not have vitrified. The protocol should automatically flag such runs for a modified workflow, such as a slower cooling rate or a longer annealing period at the estimated Tg region before the final production run.

Q4: What is the recommended method for automating the precise Tg value from the V vs. T data, and how do we define the error bars? A4: The standard automated method is a two-line linear regression fit. The algorithm should iteratively test intersection points within a defined temperature range and select the intersection that yields the highest combined R² for both fits. Error bars should be propagated from the standard errors of the slopes and intercepts of both regression lines using established formula (see table). Bootstrapping the data points is also a robust method for error estimation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Batch-to-Batch Variability in Tg for Identical Parameters

- Symptoms: >10K standard deviation in Tg for repeat simulations of the same compound.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Initial Random Seeds: Ensure the random seed for velocity generation is different for each run. Identical seeds can produce correlated, not independent, results.

- Analyze Equilibration Metrics: Plot potential energy and density over time for all runs. High variability may indicate insufficient equilibration before the cooling protocol begins.

- Verify System Size: Small system sizes (< 50 chains) lead to larger finite-size effects. Confirm all simulations use an identical, sufficiently large number of atoms.

- Solution: Implement a protocol that logs all random seeds, mandates a minimum system size (e.g., ≥ 20,000 atoms), and includes a strict equilibration criterion (e.g., density fluctuation < 0.5% over 2 ns) before proceeding to the cooling stage.

Issue: Systematic Shift in Predicted Tg Across Entire Candidate Library

- Symptoms: All computed Tg values are consistently shifted (higher or lower) from experimental benchmarks, though the internal ranking may be preserved.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Calibrate Cooling Rate: Establish a baseline shift using a standard reference material (e.g., polystyrene). The table below provides typical offsets.

- Review Pressure Control: Check the barostat settings. An inefficient barostat can cause incorrect density, affecting Tg. Use a modern, robust barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) with appropriate relaxation times.

- Solution: Apply a consistent, empirically derived correction factor based on reference materials. Document the cooling rate and correction factor explicitly in all results. Ensure barostat coupling is appropriate for the glass transition (semi-isotropic or anisotropic may be better than isotropic for some systems).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Tg Prediction Error Analysis for Common Force Fields

| Force Field | Typical Cooling Rate (MD) | Avg. Tg Offset vs. Exp. (°C)* | Main Source of Error | Recommended for Material Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF2 | 1 K/ns | +70 to +100 | Torsions, vdW | Small organic glasses, rigid molecules |

| CGenFF | 1 K/ns | +50 to +80 | Bond/angle penalties | Pharmaceutical polymers, heterocycles |

| OPLS-4 | 1 K/ns | +40 to +70 | Bond stretching | Condensed phase organics, liquids |

| PCFF+ | 1 K/ns | +20 to +50 | Dihedrals, cross-terms | Polycarbonates, vinyl polymers |

| TraPPE | 1 K/ns | +80 to +120 | United-atom coarsening | Hydrocarbons, simple alkanes |

*Offset is positive (simulation Tg > experimental Tg). Experimental Tg values are typically measured at cooling rates ~1-10 K/min.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Automated Tg Detection Protocol

| Metric | Target Value | Purpose | Failure Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Glassy Fit) | > 0.85 | Ensures equilibrated glassy state | Flag for longer equilibration/rerun |

| R² (Rubbery Fit) | > 0.98 | Ensures linear region above Tg | Flag for shorter cooling step/check phase |

| Data Points in Fit (each line) | ≥ 8 | Ensures statistical robustness | Exclude run from batch analysis |

| Tg Error (Propagated) | < ±5 K | Ensures precision | Accept result for screening |

| Density Drift (final 1ns) | < 0.2% | Confirms stability | Accept result for analysis |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized MD Workflow for Tg Prediction Objective: To generate specific volume (V) vs. temperature (T) data for Tg determination via intersection of linear fits.

- System Building: Use Amorphous Builder (e.g., in BIOVIA, Packmol) to create a periodic cell with 50-100 polymer chains (or >20,000 atoms total).

- Equilibration (NPT):

- Run at 500 K (well above expected Tg) for 10 ns.

- Use a Langevin thermostat (damping constant 100 ps⁻¹) and a Parrinello-Rahman barostat (time constant 1000 ps).

- Confirm energy and density stability (<1% fluctuation over last 2 ns).

- Cooling Protocol (NPT):

- Cool linearly from 500 K to 200 K at a rate of 1 K/ns (or a consistent, documented rate).

- Save the system state and log density every 10 K.

- Production Runs (NPT):

- At each saved temperature (e.g., 500, 490, 480...200 K), run a 2 ns production simulation.

- Calculate the average specific volume over the final 1.5 ns of each run.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot specific volume vs. temperature.

- Perform a two-region linear fit. The Tg is the intersection point of the high-T (rubbery) and low-T (glassy) regression lines.

Protocol 2: Addressing Outliers via Torsional Parameter Validation Objective: To diagnose and correct Tg outliers by comparing torsional energy profiles to quantum mechanics (QM) data.

- QM Benchmarking:

- Select a representative dimer or trimer fragment of the outlier material.

- Perform a QM (e.g., MP2/cc-pVDZ) rotational scan for the central dihedral angle(s) in 15° increments.

- Extract relative energies.

- Force Field Validation:

- Perform the same rotational scan on the isolated fragment using the MD force field.

- Plot QM vs. MD torsional energy profiles.

- Parameter Adjustment (if applicable):

- If the phase and barrier heights are mismatched (>2 kcal/mol error), consider refining the torsional parameters (V₁, V₂, V₃) via manual fitting or using a tool like

fftk(Force Field Toolkit). - Re-run the full Tg workflow (Protocol 1) with the adjusted parameters.

- If the phase and barrier heights are mismatched (>2 kcal/mol error), consider refining the torsional parameters (V₁, V₂, V₃) via manual fitting or using a tool like

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Automated High-Throughput Tg Screening Workflow

Title: Diagnosis Pathway for Tg Prediction Outliers

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Tg Screening

| Item | Function in Workflow | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Parameterized Force Field Libraries | Provides atomic-level interaction potentials for MD simulations. | CGenFF, GAFF2, OPLS-4; choice critically impacts accuracy. |

| Validated Reference Compounds | Serves as calibration standards for cooling rate offset. | Polystyrene (Tg ~100°C), Polycarbonate (Tg ~150°C). |

| Automated Structure Builder | Generates initial, packed, amorphous simulation cells. | BIOVIA Amorphous Cell, Packmol, polyply. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Scheduler Scripts | Manages parallel execution of hundreds of independent simulations. | SLURM, PBS job arrays with dependency handling. |

| Two-Region Linear Fitting Software | Automatically calculates Tg and error from V vs. T data. | Custom Python/R script using piecewise regression. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software | Benchmarks torsional energies for force field validation/correction. | Gaussian, ORCA, used for dihedral parameter scans. |

Diagnosing and Fixing Problems: A Troubleshooting Guide for Tg Outliers

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: What are the first steps when I observe an outlier Tg value in my simulation data? A: First, verify the data integrity of the simulation run. Check the simulation log files for errors, energy minimization convergence, and successful completion of the equilibration phase. Confirm that the density of the system at the start of the glass transition analysis is within expected experimental ranges. Outliers often stem from incomplete system equilibration.

Q2: My system equilibrated, but the Tg is still an outlier. What structural properties should I check? A: Analyze the radial distribution functions (RDFs) for key atom pairs (e.g., polymer backbone atoms, hydrogen bonds). Compare them to a reference system or experimental data. A shifted or missing peak in the RDF can indicate improper force field parameterization or failed system building. Next, calculate the end-to-end distance and radius of gyration of polymer chains to confirm they are not trapped in an unrealistic conformation.

Q3: How do I determine if a force field parameter is responsible for the Tg outlier? A: Perform a sensitivity analysis. Create a small test system and systematically vary parameters like torsion potentials or van der Waals (vdW) epsilon values for key dihedrals or atom types. Run short, high-throughput simulations to observe the impact on chain stiffness and density. A significant shift in predicted Tg with minor parameter changes indicates high sensitivity and potential misparameterization.

Q4: What are the common signs of water/moisture effects causing Tg discrepancies? A: An unexpectedly low Tg can signal plasticization by residual water. Inspect the simulation construction protocol. If the system was not thoroughly dried (e.g., via long NPT equilibration at low relative humidity or explicit water removal), even small amounts of water can drastically alter dynamics. Calculate the diffusion coefficient of water molecules in your system; if it's too high or too low compared to literature, it suggests incorrect water-polymer interaction parameters.

Q5: How can I diagnose issues related to the Tg calculation method itself? A: The method for extracting Tg from volume vs. temperature (V-T) or enthalpy vs. temperature (H-T) data is critical. Ensure your cooling/heating rate is documented and consistent. Re-plot the V-T data using multiple fitting ranges for the linear regimes above and below Tg. Compare the Tg value obtained from the intersection point with values from alternative methods, like calculating the inflection point of the thermal expansion coefficient. Large variations (>10 K) between methods suggest the data range is problematic or the transition is not glass-like.

Table 1: Common Causes and Diagnostic Signatures of Tg Outliers