Validating Machine Learning Models in Polymer Science: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

The application of machine learning (ML) is transforming the discovery and development of polymeric materials for biomedical applications, from drug delivery systems to implantable devices.

Validating Machine Learning Models in Polymer Science: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

The application of machine learning (ML) is transforming the discovery and development of polymeric materials for biomedical applications, from drug delivery systems to implantable devices. However, the unique, stochastic nature of polymers and frequent data scarcity present significant challenges for creating reliable models. This article provides a comprehensive framework for the rigorous validation of ML models in polymer science. It covers foundational concepts, specialized methodological approaches, solutions for common pitfalls, and comparative analysis of validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide empowers scientists and drug development professionals to build, evaluate, and trust ML models that accelerate the creation of next-generation polymer-based therapies.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Unique Challenges for ML in Polymer Science

The Indispensable Role of Validation in Polymer Science

In the field of polymer science, where research is often characterized by high-dimensional data, complex variables from synthesis conditions to chain configurations, and traditionally inefficient trial-and-error approaches, machine learning (ML) offers transformative potential [1] [2]. However, the reliability of any ML-driven discovery hinges entirely on one critical step: rigorous model validation. Model validation is the process of assessing a model's performance on unseen data to ensure its predictions are robust, reliable, and generalizable, rather than being artifacts of the specific sample data used for training [3] [4].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, proper validation is not merely a technicality; it is a fundamental safeguard. It builds confidence in a model's capacity to interpret new data accurately, helps identify the most suitable model and parameters for a given task, and is essential for detecting and rectifying potential issues like overfitting early in the development process [4]. In sensitive domains like healthcare and material science, where predictions can influence significant decisions, the margin for error is minimal. An unvalidated model can lead to inadequate performance, questionable robustness, and an inability to handle stress scenarios, ultimately producing untrustworthy outputs that can misdirect research and development [4]. Consequently, the time and resources invested in model validation often surpass those spent on the initial model development itself, making it a business and scientific imperative [4].

Core Principles and Methods of ML Model Validation

Understanding the Basics of Validation

At its core, model validation serves to estimate how a machine learning model will perform on future, unseen data. This process is crucial for preventing overfitting (where a model learns the training data too well, including its noise, and fails to generalize) and underfitting (where a model is too simple to capture the underlying trend) [5] [6]. A reliable validation strategy provides a realistic performance estimate, guides model selection and improvement, and ultimately builds stakeholder confidence in the model's predictions [5].

Essential Validation Techniques

The choice of validation technique is highly dependent on the size and nature of the available dataset. The following table summarizes the recommended procedures for different data scenarios, particularly relevant to polymer science where dataset sizes can vary greatly.

Table 1: Validation Strategies Based on Dataset Size

| Dataset Size | Recommended Validation Procedure | Generalized Error Estimation | Statistical Comparison of Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large & Fast Models | Divide into test set and multiple disjoined training sets. Train each model on each training set [7]. | Average score on the separate test set [7]. | Two-sided paired t-test based on test set scores [7]. |

| Medium Size | Divide into test and training parts. Apply k-fold cross-validation to the training part [7]. | Average score on the test set [7]. | Corrected paired t-test or McNemar's test [7]. |

| Small Dataset | K-fold cross-validation or repeated k-fold cross-validation on the entire dataset [6] [7]. | Average model scores on the validation sets [7]. | Corrected paired t-test [7]. |

| Tiny (<300 samples) | Leave-P-Out (LPO) or Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation; Bootstrapping [7]. | Average scores on the left-out samples (LOO/LPO) or on the full dataset (Bootstrapping) [7]. | Sign-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test [7]. |

The most common validation methodologies include:

Hold-out Methods: These are the most basic approaches, involving splitting the data into separate sets.

- Train-Test Split: The data is randomly split into a training set (e.g., 80%) and a test set (e.g., 20%). The model is trained on the former and evaluated on the latter [3]. Its simplicity is a advantage, but the results can be highly dependent on a single random split, especially with small datasets.

- Train-Validation-Test Split: The data is divided into three parts. The training set is for model fitting, the validation set is for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and the test set is for the final, unbiased evaluation of the chosen model [3]. This prevents information from the test set leaking into the model building process.

Resampling Methods: These methods make more efficient use of limited data.

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is randomly shuffled and split into k equal-sized groups (folds). The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining one fold for validation. The final performance is the average of the k validation scores [6]. This provides a more robust performance estimate than a single train-test split.

- Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation: An enhancement of k-fold that ensures each fold has approximately the same proportion of the target variable's classes as the complete dataset. This is particularly important for imbalanced datasets, a common challenge in scientific research [6] [7].

- Bootstrap: This method involves drawing random samples from the dataset with replacement to create a training set. The samples not selected (out-of-bag samples) are then used for validation [6]. It is especially useful for very small datasets.

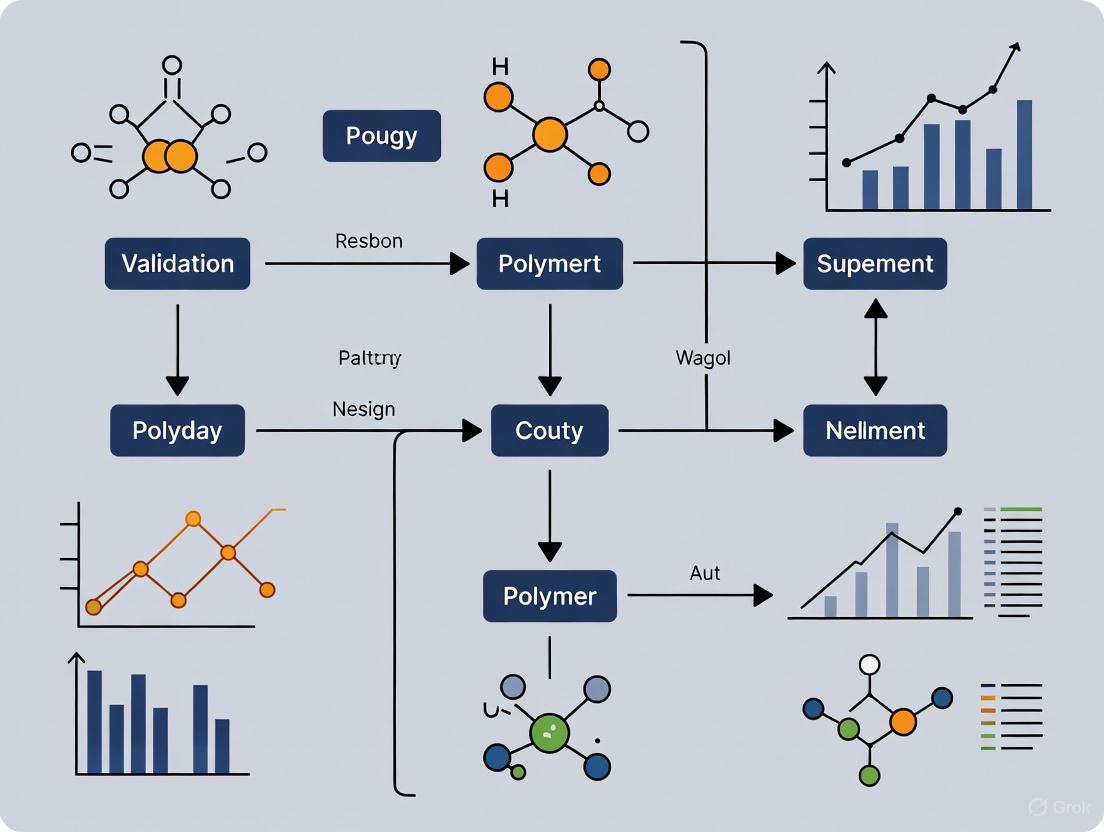

Figure 1: A typical ML workflow in polymer informatics, highlighting the central and iterative role of model validation.

Advanced Validation Frameworks for Scientific Research

Addressing the Small-Data Challenge with Simulation

A persistent challenge in scientific ML, particularly in fields like medicine and polymer science with rare materials or complex syntheses, is the limited size and heterogeneity of available datasets [8]. Traditional validation on a single, small dataset may not capture the complexity of the underlying data-generating process, leading to models that generalize poorly.

To address this, advanced frameworks like SimCalibration have been developed. This meta-simulation approach uses structural learners (SLs) to infer an approximated data-generating process from limited observational data [8]. It then generates large-scale synthetic datasets for systematic benchmarking of ML methods. This allows researchers to stress-test and select the most robust ML method in a controlled simulation environment before deploying it in costly real-world experiments, thereby reducing the risk of poor generalization [8].

Monitoring Models in Production

Validation does not end once a model is deployed. In production, models are susceptible to performance degradation due to drift [9]. Continuous monitoring is essential to maintain model reliability.

- Data Drift: Occurs when the statistical properties of the input data change over time, potentially reducing prediction accuracy as the model encounters data different from its training set [9].

- Concept Drift: Happens when the underlying relationship between the model's inputs and outputs changes, meaning the original "ground truth" the model learned is no longer valid [9].

Monitoring for these drifts using metrics like Jensen-Shannon divergence or Population Stability Index (PSI), and setting up alerts for significant changes, is a critical part of the ongoing validation lifecycle, ensuring the model remains accurate and trustworthy in a dynamic real-world environment [9].

Experimental Protocols and Comparative Analysis

A Protocol for Validating Polymer Property Predictors

When using ML to predict polymer properties—a common application in polymer informatics—a rigorous validation protocol is essential. The following provides a detailed methodology suitable for a scientific publication.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Informatics

| Item / Solution | Function in ML Workflow | Example Tools / Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Databases | Provides structured, experimental data for model training and testing; the foundation of any data-driven project. | PolyInfo, PubChem, internal datasets [2]. |

| Data Preprocessor | Cleans raw data, handles missing values, and normalizes/standardizes features to prepare data for algorithms. | Scikit-learn (Python), Pandas (Python) [2]. |

| Feature Selector | Identifies the most relevant input variables (e.g., molecular descriptors, processing parameters) to improve model efficiency and interpretability. | Scikit-learn, RFE (Recursive Feature Elimination) [2]. |

| ML Algorithm Suite | A collection of algorithms for training models on the prepared data. | Scikit-learn (for LR, SVM, RF, etc.), TensorFlow/PyTorch (for ANN) [2]. |

| Validation Framework | Implements cross-validation, hold-out methods, and statistical tests to evaluate model performance and compare candidates. | Scikit-learn, MLR3 (R), custom simulation frameworks [8] [3]. |

Objective: To compare the performance of multiple ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Artificial Neural Networks) for predicting a specific polymer property (e.g., glass transition temperature, Tg) and select the most robust one.

Methodology:

- Data Collection & Curation: Compile a dataset of polymers with known Tg values and associated molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, chain rigidity, functional groups) from a trusted database like PolyInfo [2]. The dataset should be as large and high-quality as possible.

- Data Preprocessing: Clean the data by removing entries with significant missing values. Standardize or normalize all feature descriptors to ensure they are on a comparable scale, which is crucial for many ML algorithms [2].

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection methods (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) to identify the subset of molecular descriptors that have the most significant influence on Tg. This simplifies the model and can enhance its generalization ability [2].

- Model Training & Validation:

- Implement the models to be compared (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, ANN).

- Given the typical dataset sizes in polymer science, employ a 10-fold stratified cross-validation protocol on the entire dataset [7]. This means the data is split into 10 folds, and the model is trained and validated 10 times, each time with a different fold held out as the validation set.

- For algorithms that require hyperparameter tuning (e.g., ANN, SVM), use a nested cross-validation approach. In the outer loop, the data is split into training and validation folds. In the inner loop, the training fold is further split to optimize the hyperparameters. This prevents optimistic bias in the performance estimate [7].

- Performance Evaluation & Model Selection: Calculate performance metrics for each model and each fold. Common metrics for regression tasks like property prediction include Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R² score [9]. Compare the average performance across all folds to select the best model. Use a corrected paired t-test on the validation scores from the cross-validation folds to determine if the performance difference between the top models is statistically significant [7].

Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance

The following table summarizes hypothetical experimental data, as might be presented in a polymer informatics study, to illustrate how different models can be compared based on a rigorous validation protocol.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of ML Models for Predicting Polymer Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

| Machine Learning Model | Average RMSE (10-Fold CV) (°C) | Average R² (10-Fold CV) | Key Advantages | Limitations / Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression (LR) | 18.5 | 0.72 | High interpretability, fast training, low computational cost. | Assumes linear relationship, may underfit complex data. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 12.1 | 0.85 | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; good for non-linear relationships. | Performance sensitive to hyperparameters; slower training. |

| Random Forest (RF) | 10.8 | 0.88 | Handles non-linearity well; robust to outliers and overfitting. | Lower interpretability ("black box"); moderate computational cost. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 9.5 | 0.91 | High capacity for learning complex, non-linear relationships. | High computational cost; requires large data; prone to overfitting. |

Note: The data in this table is illustrative. Actual results will vary based on the specific dataset and experimental setup.

For the scientific community, particularly researchers in polymer science and drug development, rigorous ML model validation is not an optional postscript but a foundational component of credible, reproducible research. The journey from raw data to a reliable predictive model necessitates a careful, methodical approach to validation—selecting the right strategy for the dataset size, employing resampling techniques like cross-validation to maximize data utility, leveraging advanced frameworks like simulation for small-data scenarios, and continuously monitoring models post-deployment. By systematically comparing models using structured protocols and quantitative metrics, as demonstrated in this guide, scientists can move beyond opaque "black boxes" and build ML solutions that are truly robust, trustworthy, and capable of accelerating the discovery of the next generation of advanced polymers and therapeutic agents.

The application of machine learning (ML) in materials science has revolutionized the discovery and design of inorganic crystals and small molecules. However, the stochastic structures and hierarchical morphologies of polymers present a unique set of challenges that hinder the direct application of standard ML models and validation protocols [10]. Unlike small molecules or crystalline materials with well-defined, repeatable atomic arrangements, polymers are macromolecular architectures characterized by an inherent statistical distribution in their structure and properties [11]. This structural complexity means that a polymer sample is not a single, unique entity but a collection of chains with variations in molecular weight, sequence, and three-dimensional arrangement [12].

This guide objectively compares the foundational differences between polymers and other material classes, framing them within the critical context of validating ML models for polymer research. We will dissect the specific challenges, provide experimental and computational data that highlight these disparities, and detail the methodologies required to build robust, trustworthy ML tools for polymer science and drug development.

Fundamental Structural Divergences: Polymers vs. Other Materials

The core of the challenge lies in the fundamental structural differences between polymers and other materials. A comparative analysis of these differences is essential for understanding why off-the-shelf ML solutions often fail.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Material Structures and their ML Implications.

| Material Class | Structural Characteristics | Machine Readability | Key ML Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules | Defined atomic composition, fixed molecular weight, single, deterministic structure [10]. | High. Easily represented by SMILES strings, molecular graphs, or fingerprints [13]. | Minimal. Structure is easily digitized, and property prediction is relatively straightforward. |

| Crystalline Inorganic Materials | Periodic, repeating atomic lattice in 3D space. Defined unit cell [10]. | High. Accurately described by unit cell parameters, space groups, and atomic coordinates. | Moderate. Focus is on predicting stability and properties from a defined crystal structure. |

| Polymers | Stochastic Structures: Distribution of chain lengths (molecular weights), sequences (in copolymers), and branching [11] [10].Hierarchical Morphologies: Properties emerge from structures across multiple scales (atomic, chain, supramolecular, morphological) [14].Process-Dependent Morphology: Final structure is influenced by synthesis and processing history [11]. | Low. No single representation captures molecular weight, dispersity, branching, tacticity, and chain packing [10]. | High. Difficult to create a definitive digital fingerprint. Models struggle to link a simplified representation (e.g., repeat unit) to complex, process-dependent bulk properties. |

A striking example of this structural dichotomy is polyethylene. While its monomeric repeat unit is simple (-CHâ‚‚-), its bulk properties can vary dramatically based on its macromolecular architecture. High-density polyethylene (HDPE), with its linear chains, is rigid and strong, while low-density polyethylene (LDPE), containing extensive chain branching, is flexible and tough [10]. Communicating this architectural information quantitatively to an ML model is a non-trivial challenge that is absent in the study of most other material classes.

Quantitative Experimental Evidence of Structural Complexity

The impact of polymer structural complexity is quantifiable. The following experimental and simulation data illustrate how multi-scale structures directly influence measurable properties, creating a validation nightmare for ML models trained solely on chemical composition.

The Combinatorial Space of Polymer Sequences

The design space for polymers is astronomically large. A linear copolymer with just two types of monomers (A and B) and a chain length of 50 has a sequence space of 2^49 (over 10^15) possible unique polymers [13]. Exploring this space experimentally or computationally is intractable, and ML models must be designed to navigate this complexity efficiently.

Table 2: Experimental Data Showcasing Process-Dependent Property Variation.

| Polymer System | Experimental Variable | Key Measured Property | Result & Impact | Experimental Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [15] | Monomer-to-Template Ratio; Monomer Type (AA vs. MAA) | Binding Energy (ΔEbind), Effective Binding Number (EBN) | Optimal ratio found at 1:3; Carboxylic acid monomers (e.g., TFMAA, ΔEbind = -91.63 kJ/mol) outperformed ester monomers. | QC/MD Simulation: Quantum chemical calculations (B3LYP/6-31G(d)) for binding energy and bond analysis. Molecular Dynamics simulations in explicit solvent to calculate EBN and hydrogen bond occupancy. Experimental Validation: Synthesis via SI-SARA ATRP and adsorption tests to confirm imprinting efficiency. |

| Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells (PEFCs) [16] | Startup Temperature & Current Density; Initial Membrane Water Content (λ) | Cell Voltage Evolution; Shutdown Time | Lower current density extends operation time; Higher initial water content leads to earlier shutdown due to ice blocking pores. | Pseudo-Isothermal Cold Start Test: Cell with large thermal mass to maintain subzero temperature. 3-D Multiphase Model: Transient model simulating ice formation, water/heat transport, and electrochemical reaction, validated against voltage evolution data. |

| General Polymer Classes | Synthesis & Processing Conditions (e.g., cooling rate, shear) | Degree of Crystallinity; Glass Transition Temperature (Tg); Tensile Strength | Mechanical and thermal properties are not intrinsic to chemistry but are determined by the processing-induced hierarchical morphology [14]. | Standardized ASTM Testing: DSC for Tg and crystallinity; Tensile testing for mechanical properties. Metadata on processing history is critical for reproducibility. |

Data Scarcity and Model Validation

ML models typically improve with more data, but the polymer field is plagued by a lack of large, standardized, and high-quality databases [11] [10]. Existing databases like PoLyInfo and PI1M are significant advancements, but they often lack the crucial metadata on processing history and molecular weight distributions necessary to fully capture the structure-property relationship [12]. This data scarcity makes it difficult to train models that can extrapolate reliably and underscores the need for robust uncertainty quantification in any polymer ML pipeline [11].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Polymer ML Models

Given the challenges outlined, validating an ML model for polymer science requires a rigorous, multi-pronged experimental approach. The following protocols are essential for generating reliable data and building trust in model predictions.

Protocol 1: Computational Screening of Molecular Interactions

Objective: To quantitatively predict the efficacy of a polymer-template interaction at the molecular level before synthesis [15].

- System Setup: Define the pre-polymerization system, including the template molecule, functional monomer(s), crosslinker, and solvent (e.g., acetonitrile).

- Quantum Chemical (QC) Calculations:

- Use software like Gaussian [13] at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level to optimize the geometry of all components.

- Perform Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis to determine atomic charges and identify potential hydrogen bonding sites.

- Calculate the binding energy (ΔEbind) for various template-monomer complexes in a 1:1 ratio.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- Use packages like GROMACS or LAMMPS [13] to simulate a box containing the template, multiple monomers, crosslinker, and explicit solvent molecules.

- Run the simulation for a sufficient time to achieve equilibrium.

- Analyze trajectories to calculate quantitative parameters like Effective Binding Number (EBN) and Maximum Hydrogen Bond Number (HBNMax) to evaluate binding efficiency.

- Validation: Synthesize the top candidate polymers (e.g., via SI-SARA ATRP [15]) and perform adsorption tests to compare experimental binding capacity with computational predictions.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Process-Dependent Morphology

Objective: To empirically link processing conditions to the resulting hierarchical structure and macroscopic properties.

- Controlled Synthesis & Processing: Synthesize the same polymer chemistry (e.g., polyethylene) using different catalysts and processing conditions (e.g., extrusion rate, cooling temperature) to create variants like HDPE and LDPE [10].

- Multi-Scale Characterization:

- Molecular Level: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to measure molecular weight and dispersity (Ã).

- Supramolecular Level: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to quantify crystallinity and Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS) to analyze crystal structure.

- Morphological Level: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) or Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to visualize phase separation, spherulite size, or other microstructural features [14].

- Property Measurement: Conduct standardized mechanical (tensile, impact) and thermal tests on the processed samples.

- Metadata Documentation: Crucially, record all processing parameters (temperature, pressure, shear rates, etc.) as essential metadata for the ML dataset [11].

Visualization of Hierarchical Complexity and ML Workflow

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, encapsulate the core concepts of polymer hierarchy and the corresponding ML validation workflow.

The Structural Hierarchy of Polymers

This diagram illustrates the multi-scale nature of polymer structures, which gives rise to their complex properties.

ML Validation Workflow for Polymer Informatics

This diagram outlines a robust ML pipeline that incorporates polymer-specific challenges, including data collection, featurization, and model validation.

Success in polymer informatics relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools designed to handle structural complexity.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Polymer Informatics Research.

| Tool Category | Specific Tool / Resource | Function in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Simulation Software | LAMMPS [13], GROMACS [13], Gaussian [13] | Performs Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Quantum Chemical (QC) calculations to simulate polymer behavior at different scales and predict interaction energies. |

| Polymer Databases | PoLyInfo [12], PI1M [12], Khazana [12] | Provides curated datasets of polymer structures and properties for training and benchmarking machine learning models. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [17] | Model architectures suited for learning from graph-based polymer representations or spectral/image data. |

| Featurization & Descriptors | SMILES Strings [13], One-Hot Encoding [13], Polymer Genome [13] | Converts polymer chemical structures into machine-readable numerical representations (fingerprints). |

| Experimental Synthesis | SI-SARA ATRP [15], High-Throughput Robotics [10] | Enables controlled and automated synthesis of polymer libraries for rapid data generation and model validation. |

| Characterization Techniques | GPC, DSC, SEM, AFM | Measures molecular weight, thermal properties, and morphological features essential for ground-truth data. |

The stochastic structures and hierarchical morphologies of polymers are not merely academic curiosities; they are fundamental characteristics that dictate material performance and create significant obstacles for computational design. Successfully validating machine learning models in polymer science requires a paradigm shift from treating polymers as simple, deterministic chemicals to acknowledging them as complex, process-dependent systems. This entails the rigorous generation of multi-scale data, the development of sophisticated featurization methods that capture architectural information, and the implementation of validation protocols that explicitly test for extrapolation and physical plausibility. By embracing this complexity, the field can build reliable ML tools that accelerate the discovery of next-generation polymers for drug delivery, energy storage, and advanced manufacturing.

In polymer science, the traditional research paradigm, reliant on intuition and trial-and-error, struggles to navigate the vast molecular design space. The emergence of data-driven approaches, particularly machine learning (ML), promises to accelerate the discovery of polymers with tailored properties. However, the effectiveness of these models is critically dependent on the quality and quantity of data available for training and validation. This guide objectively compares the performance of different ML strategies and tools designed to overcome the pervasive challenges of data scarcity and inconsistent data formats in polymer informatics.

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Data Scarcity

To address the limited availability of labeled polymer data, researchers have developed sophisticated training frameworks and data representation methods. The protocols below detail two prominent approaches.

Multi-task Auxiliary Learning Framework

This methodology leverages data from multiple related prediction tasks to improve performance on a primary, data-scarce task. The underlying principle is that learning across auxiliary tasks forces the model to develop more robust and generalizable representations.

- Primary Objective: To improve prediction accuracy for a target polymer property (e.g., glass transition temperature,

Tg) where experimental data is limited. - Compiled Dataset: A large dataset of polymers labeled with various properties obtained from molecular simulations and wet-lab experiments is required [18].

- Model Training:

- The model, typically a neural network, is trained simultaneously on the primary target task and several auxiliary tasks (e.g., predicting density,

Ï, or molecular weight). - The model's shared layers learn a unified representation of polymer structures that is informative for all tasks.

- Task-specific output layers then make individual property predictions.

- The model, typically a neural network, is trained simultaneously on the primary target task and several auxiliary tasks (e.g., predicting density,

- Outcome: This approach has been shown to enhance model performance and generalization for the target task by mitigating overfitting, which is common when training on small datasets [18].

Periodicity-Aware Pre-training (PerioGT)

This protocol addresses data scarcity by incorporating the inherent structural periodicity of polymers into a deep learning model through self-supervised pre-training.

- Primary Objective: To construct a foundational model for polymers that generalizes effectively across diverse downstream prediction tasks.

- Pre-training Phase:

- A chemical knowledge-driven periodicity prior is integrated into a graph neural network model. This prior explicitly informs the model that polymers are composed of repeating units.

- Contrastive learning is employed, where the model learns to identify whether two augmented views of a polymer graph originate from the same molecule. A graph augmentation strategy that integrates additional conditions via virtual nodes is used to model complex chemical interactions [19].

- Fine-tuning Phase: The pre-trained model is subsequently adapted to specific downstream tasks (e.g., property prediction). Periodicity prompts are learned during this phase based on the prior established in pre-training [19].

- Outcome: This framework has achieved state-of-the-art performance on 16 diverse downstream tasks. Its effectiveness was validated through wet-lab experiments that identified two polymers with potent antimicrobial properties [19].

Objective Performance Comparison of ML Strategies

The following table summarizes the performance of various ML approaches as reported in recent polymer informatics literature. It provides a direct comparison of their effectiveness in mitigating data challenges.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Strategies in Polymer Informatics

| ML Strategy / Tool | Reported Performance / Outcome | Key Advantage for Data Scarcity | Polymer Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-task Learning [18] | Improved prediction accuracy for target properties with limited data. | Leverages data from related tasks; reduces overfitting. | Varies (e.g., SMILES strings, molecular graphs). |

| Periodicity-Aware Model (PerioGT) [19] | State-of-the-art performance on 16 downstream tasks. | Self-supervised pre-training captures fundamental polymer chemistry. | Periodic graphs incorporating repeating units. |

| Chemistry-Informed ML for Polymer Electrolytes [20] | Enhanced prediction accuracy for ionic conductivity by incorporating the Arrhenius equation. | Integrates physical laws, reducing reliance on massive datasets. | Not specified. |

| Polymer Genome [20] | Rapid prediction of various polymer properties using trained models. | An established platform that aggregates data and models for immediate use. | Chemical structure and composition data. |

| Explainable ML for Conjugated Polymers [20] | Classification model achieved 100% accuracy; regression model achieved R² of 0.984. | Accelerates the measurement process by 89%, optimizing data collection. | Spectral data (absorbance spectra). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational "reagents" required to implement the ML strategies discussed.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Informatics

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Data Scarcity & Formats |

|---|---|---|

| PerioGT Code & Checkpoints [19] | Provides the model architecture and pre-trained weights for the periodicity-aware framework. | Offers a pre-built solution that bypasses the need for training a model from scratch on a small dataset. |

| Polymer Genome Platform [20] | A data-powered polymer informatics platform for property predictions. | Provides access to pre-trained models and standardized data, mitigating challenges of in-house data collection. |

| PI1M Dataset [19] | A benchmark database containing one million polymers for pre-training and transfer learning. | A large, centralized dataset that can be used to bootstrap models for specific tasks with less data. |

| Multi-task Training Framework [18] | A supervised training framework that uses auxiliary tasks. | A methodological approach that maximizes the utility of existing, multi-faceted datasets. |

| Sulfaperin | Sulfaperin Reference Standard|CAS 599-88-2 | Sulfaperin is a sulfonamide antibiotic for research, notably in quorum sensing studies. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tebufenpyrad | Tebufenpyrad|Acaricide for Agricultural Research | Tebufenpyrad is a METI acaricide for controlling mites in crop research. This product is for professional Research Use Only. Not for personal use. |

Visualizing the Multi-task Learning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the multi-task auxiliary learning protocol, showing how a single model architecture learns from multiple data sources to improve predictions on a target task.

Discussion and Comparative Outlook

The comparative analysis reveals that no single solution exists for the data challenges in polymer informatics. The choice of strategy depends on the specific research context. Periodicity-aware models like PerioGT offer a powerful, general-purpose solution by fundamentally encoding polymer chemistry, making them highly generalizable across tasks [19]. In contrast, multi-task learning provides a flexible framework that can be applied even with smaller, multi-property datasets to prevent overfitting [18].

Tools like Polymer Genome offer an accessible entry point for researchers who may lack the computational resources to develop models from scratch [20]. Meanwhile, the most significant performance gains often come from hybrid approaches that integrate physical laws or domain knowledge (e.g., Arrhenius equation, periodicity) directly into the ML model, creating a more data-efficient learning process [19] [20]. As the field evolves, the consolidation of these advanced strategies with open, large-scale databases will be critical for developing robust and universally applicable ML models for polymer science.

In the field of polymer science research, particularly in pharmaceutical formulation development, the accurate prediction of material properties and drug release profiles is paramount. Machine learning (ML) models offer powerful tools to accelerate the design of polymeric drug delivery systems (PDDS), such as amorphous solid dispersions, matrix tablets, and 3D-printed dosage forms [21]. However, the reliability of these predictions hinges on robust validation methodologies. Proper validation ensures that models can generalize beyond the specific experimental data used for training, providing trustworthy predictions for new formulations. This guide explores the core concepts of model validation—from resampling techniques like cross-validation and bootstrapping to performance metrics—within the context of polymer science applications. We objectively compare these methods and provide experimental protocols to help researchers select the most appropriate validation strategies for their specific challenges, such as predicting drug solubility in polymers or estimating activity coefficients from molecular descriptors [22].

Core Validation Methods: Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping

Cross-Validation

Cross-validation is a resampling technique that systematically partitions the dataset into complementary subsets to validate model performance on unseen data [23]. The primary goal is to provide a reliable estimate of how a model will perform in practice when deployed for predicting properties of new polymer formulations.

Key Types of Cross-Validation:

- k-Fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is randomly shuffled and divided into k equal-sized folds (typically k=5 or k=10). The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold. This process is repeated k times, with each fold serving as the validation set exactly once. The final performance metric is the average of the k validation scores [23] [6].

- Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation: This variant maintains the same class distribution in each fold as in the complete dataset, which is particularly important for imbalanced datasets commonly encountered in pharmaceutical research where certain polymer-drug combinations may be underrepresented [23] [6].

- Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV): A special case of k-fold cross-validation where k equals the number of data points. Each data point is used once as a validation set while the remaining points form the training set. While computationally expensive, LOOCV provides an almost unbiased estimate of model performance [23].

Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that involves drawing random samples from the original dataset with replacement to create multiple bootstrap datasets [23] [24]. This method is particularly valuable for estimating the variability of performance metrics and is especially useful with smaller datasets common in experimental polymer science.

Key Bootstrapping Process:

- Bootstrap Sample Creation: Randomly select n samples from the original dataset of size n with replacement to form a bootstrap sample. This process is repeated B times (typically 100-500 iterations) to create multiple bootstrap datasets [23].

- Out-of-Bag (OOB) Evaluation: For each bootstrap sample, the model is trained and then evaluated on the data points not included in that sample (the OOB samples). The OOB error provides an estimate of model performance [23] [24].

- Optimism Bootstrap: A specialized approach that estimates overfitting by comparing performance on bootstrap samples versus the original dataset. This method calculates the "optimism" of the model and subtracts it from the apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected estimate [25].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences

Table 1: Fundamental differences between cross-validation and bootstrapping

| Aspect | Cross-Validation | Bootstrapping |

|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | Splits data into mutually exclusive subsets | Samples with replacement from original data |

| Sample Structure | No overlap between training and test sets in iterations | Samples contain duplicate instances; some points omitted |

| Primary Goal | Estimate predictive performance on unseen data | Estimate variability and stability of performance metrics |

| Bias-Variance Trade-off | Generally lower variance with adequate folds | Can provide lower bias by using full dataset samples |

| Computational Intensity | Less intensive for smaller k values | More intensive with large numbers of bootstrap samples |

| Ideal Dataset Size | Works well with medium to large datasets | Particularly effective with smaller datasets |

Methodological Workflows

Cross-Validation Workflow:

Bootstrapping Workflow:

Performance Metrics for Model Evaluation

Core Classification Metrics

In polymer science research, classification tasks might include identifying successful polymer-drug combinations or categorizing formulation performance. The following metrics derived from confusion matrices provide nuanced insights beyond simple accuracy [26] [27].

Confusion Matrix Fundamentals:

- True Positive (TP): Correctly predicted positive cases (e.g., correctly identifying a polymer with desired release properties)

- True Negative (TN): Correctly predicted negative cases (e.g., correctly identifying an incompatible polymer-drug combination)

- False Positive (FP): Incorrectly predicted positive cases (Type I error)

- False Negative (FN): Incorrectly predicted negative cases (Type II error) [27] [28]

Table 2: Key classification metrics and their applications in polymer science

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Polymer Science Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) | Overall correctness across both classes | Preliminary screening when class distribution is balanced |

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP) | Proportion of positive predictions that are correct | Critical when false positives are costly (e.g., pursuing ineffective formulations) |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP+FN) | Proportion of actual positives correctly identified | Essential when missing a positive case is costly (e.g., overlooking a promising polymer) |

| F1 Score | 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | Balanced measure for imbalanced datasets common in formulation research |

| False Positive Rate | FP/(FP+TN) | Proportion of actual negatives incorrectly flagged | Important when resources are wasted on false leads |

Regression Metrics for Predictive Modeling

Many polymer science applications involve continuous outcomes, such as predicting drug solubility in polymers [22] or release profiles [21]. For these regression tasks, different metrics are required:

- R² (Coefficient of Determination): Measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. In pharmaceutical formulation research, values above 0.9 are often targeted [22].

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): The average of squared differences between predicted and actual values. Useful for penalizing large errors more heavily.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The average of absolute differences between predicted and actual values. More interpretable as it represents average error in the original units.

Metric Selection Guidance

The choice of evaluation metric should align with both the technical requirements of the model and the practical consequences of different types of errors in the research context [26] [28]:

- Prioritize Recall when false negatives have severe consequences, such as missing a highly effective polymer-excipient combination that could significantly enhance drug bioavailability.

- Prioritize Precision when false positives are problematic, such as incorrectly predicting that a formulation will achieve target release profiles, leading to wasted experimental resources.

- Use F1 Score when seeking a balance between precision and recall, particularly with imbalanced datasets where one class of formulations is rare but important.

- R² and MAE are most appropriate for continuous outcomes like predicting solubility values or release kinetics, where the magnitude of error directly impacts formulation decisions [22].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation Protocols

Protocol 1: k-Fold Cross-Validation for Drug Release Prediction

- Dataset Preparation: Compile experimental data including polymer characteristics, drug properties, and measured release profiles. Preprocess by removing outliers using Cook's distance (threshold: 4/(n-p-1)) and apply Min-Max scaling to normalize features [22].

- Model Training: For each of the k folds, train the model on k-1 subsets. In polymer informatics, this may involve Decision Trees, K-Nearest Neighbors, or Neural Networks, potentially enhanced with ensemble methods like AdaBoost [22].

- Validation: Evaluate the model on the held-out fold, recording performance metrics (e.g., R², MSE) for drug release prediction.

- Iteration and Aggregation: Repeat the process k times, ensuring each fold serves as the validation set once. Calculate the mean and standard deviation of performance metrics across all folds.

Protocol 2: Bootstrapping for Solubility Prediction Uncertainty

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: From the original dataset of n polymer-drug pairs, draw B bootstrap samples (typically B=200-500) by random sampling with replacement [23] [25].

- Model Training and OOB Evaluation: For each bootstrap sample, train a predictive model (e.g., for drug solubility in polymers) and evaluate it on the out-of-bag samples not included in that bootstrap sample [24].

- Performance Calculation: Compute the performance metric of interest for each bootstrap iteration.

- Bias Correction (Optimism Bootstrap): Calculate the optimism by comparing bootstrap performance with original dataset performance. Subtract this optimism from the apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected estimate [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational and data resources for ML validation in polymer science

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing | Cook's Distance, Min-Max Scaling | Identifies outliers and normalizes feature ranges | Preparing molecular descriptor data for solubility prediction [22] |

| Feature Selection | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Selects most relevant molecular descriptors | Reducing 24 input features to key predictors for drug solubility [22] |

| Base Algorithms | Decision Trees, K-Nearest Neighbors, MLP | Foundation models for predictive tasks | Predicting drug solubility in polymers [22] |

| Ensemble Methods | AdaBoost | Combines multiple weak learners to improve performance | Enhancing decision tree performance for solubility prediction (ADA-DT) [22] |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | Harmony Search (HS) Algorithm | Optimizes model parameters for maximum accuracy | Fine-tuning KNN parameters for activity coefficient prediction [22] |

| Validation Frameworks | Neptune.ai, Dataiku DSS | Tracks experiments and compares model performance | Comparing multiple formulations across different validation strategies [6] [29] |

Comparative Performance in Polymer Science Applications

Experimental Comparisons

Recent research in pharmaceutical informatics provides empirical evidence for the performance of different validation approaches in polymer science contexts:

Drug Solubility Prediction Study: A comprehensive study predicting drug solubility in polymers utilizing over 12,000 data rows with 24 input features demonstrated the effectiveness of ensemble methods with robust validation [22]. The ADA-DT (AdaBoost with Decision Tree) model achieved exceptional performance with an R² score of 0.9738 on the test set, with MSE of 5.4270E-04 and MAE of 2.10921E-02 for drug solubility prediction. For activity coefficient (gamma) prediction, the ADA-KNN model outperformed others with an R² value of 0.9545, MSE of 4.5908E-03, and MAE of 1.42730E-02 [22].

Validation Method Comparisons: Expert analyses indicate that 10-fold cross-validation repeated 100 times and the Efron-Gong optimism bootstrap generally provide comparable validation accuracy when properly implemented [25]. The bootstrap method has the advantage of officially validating models with the full sample size N, while cross-validation typically uses 9N/10 samples for training. For extreme cases where the number of features exceeds the number of samples (N < p), repeated cross-validation may be more reliable [25].

Decision Framework for Polymer Researchers

Selecting the appropriate validation strategy depends on multiple factors specific to the research context:

Table 4: Guidelines for selecting validation methods in polymer science research

| Research Scenario | Recommended Validation | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small datasets (<100 samples) | Bootstrapping (200+ iterations) | Maximizes use of limited data; provides uncertainty estimates | More effective for small datasets where splitting might not be feasible [23] |

| Feature selection optimization | Nested cross-validation | Prevents overfitting by keeping test data completely separate | Essential when feature selection is part of model building [6] |

| Uncertainty quantification | Bootstrapping with OOB estimation | Directly estimates variability of performance metrics | Provides an estimate of the variability of the performance metrics [23] |

| Computational efficiency needed | 5- or 10-fold cross-validation | Reasonable balance between bias and variance with lower computation | Less computationally intensive than large bootstrap iterations [23] |

| High-dimensional data (p ≈ N or p > N) | Repeated cross-validation | More stable with limited samples and many features | Works even in extreme cases where N < p unlike the bootstrap [25] |

Robust validation is fundamental to developing reliable machine learning models for polymer science and pharmaceutical formulation. Cross-validation and bootstrapping offer complementary approaches for estimating model performance, each with distinct advantages depending on dataset characteristics, computational resources, and research goals. Performance metrics must be selected based on the specific consequences of different error types in the application context, with classification metrics like precision, recall, and F1 score providing more nuanced insights than accuracy alone for decision-making in formulation development.

Experimental evidence from pharmaceutical informatics demonstrates that ensemble methods combined with appropriate validation strategies can achieve high predictive accuracy for complex properties like drug solubility in polymers. By implementing the protocols and guidelines presented in this comparison, researchers in polymer science can make informed decisions about validation methodologies, leading to more trustworthy predictive models that accelerate the development of advanced drug delivery systems and polymeric materials.

Polymers are integral to countless applications, from everyday materials to advanced technologies in drug delivery and medical devices [1]. However, the polymer chemical space is so vast that identifying application-specific candidates presents unprecedented challenges as well as opportunities [30]. The traditional trial-and-error approach to polymer development is notoriously time-consuming and resource-intensive [31]. Polymer informatics has emerged as a data-driven solution to this challenge, leveraging machine learning (ML) algorithms to create surrogate models that can make instantaneous predictions of polymer properties, thereby accelerating the discovery and design process [32].

The core challenge in polymer informatics lies in establishing accurate quantitative relationships between polymer structures and their properties—a complex task given the multi-level, multi-scale structural characteristics of polymeric materials [1]. This comprehensive guide examines the complete polymer informatics pipeline, comparing the performance of leading fingerprinting methodologies—traditional handcrafted fingerprints, transformer-based models, and graph neural networks—to provide researchers with objective data for selecting appropriate tools for their specific research contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Fingerprinting Methodologies

Fundamental Fingerprinting Approaches

The initial and most critical step in any polymer informatics pipeline is converting polymer chemical structures into numerical representations known as fingerprints, features, or descriptors [30]. These representations enable machine learning algorithms to process and learn from chemical structures. Three primary approaches have emerged:

Handcrafted Fingerprints: Traditional cheminformatics tools that numerically encode key chemical and structural features of polymers using expert-derived rules [30]. Examples include Polymer Genome (PG) fingerprints that represent polymers at three hierarchical levels—atomic, block, and chain—capturing structural details across multiple length scales [33].

Transformer-Based Models: Approaches that treat polymer structures as a chemical language, using natural language processing techniques to learn representations directly from Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings [30] [34]. The polyBERT model exemplifies this approach, using a DeBERTa-based architecture trained on millions of polymer SMILES strings [30].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Methods that represent polymers as molecular graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, to encode immediate and extended connectivities between atoms [30]. Models like polyGNN and PolyID use message-passing neural networks to learn polymer representations directly from graph structures [35].

Performance Benchmarking

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Polymer Fingerprinting Methods

| Method | Representation | Accuracy (MAE) | Speed | Data Efficiency | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handcrafted (PG) | Hierarchical fingerprints | Moderate | Baseline | High | Moderate |

| polyBERT | Chemical language (SMILES) | High | 100x faster than handcrafted [30] | Requires large datasets | Limited |

| polyGNN | Molecular graph | High [30] | Fast (GPU-accelerated) | Moderate | Moderate via attention |

| LLaMA-3-8B | SMILES via fine-tuning | Approaches traditional methods [33] | Slow inference | Low with fine-tuning | Limited |

| PolyID | Molecular graph with message passing | Tg MAE: 19.8-26.4°C [35] | Moderate | High with domain validity | High via bond importance |

Table 2: Specialized Capabilities Across Polymer Informatics Methods

| Method | Multi-task Learning | Uncertainty Quantification | Synthesizability Assessment | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handcrafted (PG) | Supported [33] | Limited | Limited | Extensive historical data |

| polyBERT | Excellent [30] | Limited | Limited | Computational validation |

| polyGNN | Supported [30] | Moderate | Limited | Partial experimental validation |

| POINT2 Framework | Extensive | Advanced (aleatoric & epistemic) | Template-based polymerization | Benchmark datasets |

| PolyID | Multi-output | Domain validity method | Limited | Extensive experimental (22 polymers) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

polyBERT Training and Validation Protocol

The polyBERT framework implements a comprehensive training pipeline with the following experimental protocol [30]:

Data Curation: Generated 100 million hypothetical polymers using the Breaking Retrosynthetically Interesting Chemical Substructures (BRICS) method to decompose 13,766 synthesized polymers into 4,424 unique chemical fragments, followed by enumerative composition.

Canonicalization: Developed and applied the canonicalize_psmiles Python package to standardize polymer SMILES representations, ensuring consistent input formatting.

Model Architecture: Implemented a DeBERTa-based encoder-only transformer model (as implemented in Huggingface's Transformer Python library) with a supplementary three-stage preprocessing unit for PSMILES strings.

Training Regimen: Unsupervised pretraining on 100 million hypothetical PSMILES strings, followed by supervised multitask learning on a dataset containing 28,061 homopolymer and 7,456 copolymer data points across 29 distinct properties.

Validation: Benchmarking against state-of-the-art handcrafted Polymer Genome fingerprinting using both accuracy metrics and computational speed measurements.

polyGNN and Graph-Based Methodologies

Graph-based approaches employ distinctly different experimental protocols [30]:

Graph Representation: Polymers are represented as molecular graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. For polymers, special edges are introduced between heavy boundary atoms to incorporate the recurrent topology of polymer chains.

Architecture: Implementation of graph convolutional networks or message-passing neural networks that learn polymer embeddings through neighborhood aggregation functions.

Training: Typically trained end-to-end, with latent space representations learned under supervision with polymer properties, making the representations property-dependent.

Large Language Model Fine-tuning Protocol

Recent approaches have fine-tuned general-purpose LLMs using specific protocols [33]:

Data Preparation: Curated dataset of 11,740 experimental thermal property values converted to instruction-tuning format. Systematic prompt optimization to determine effective prompt structure.

Canonicalization: Standardized SMILES representations to address non-uniqueness issues.

Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning: Employed Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) to approximate large pre-trained weight matrices with smaller, trainable matrices, reducing computational overhead.

Hyperparameter Optimization: Comprehensive tuning of rank, scaling factor, number of epochs, and softmax temperature.

The Polymer Informatics Workflow: From Data to Deployment

The complete polymer informatics pipeline encompasses multiple stages from problem identification to production models, each with specific considerations and methodological choices.

Polymer Informatics Workflow

Performance Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Comparative Performance Metrics

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate polymer informatics method depends on specific research constraints and objectives:

For High-Throughput Screening: polyBERT's remarkable speed (two orders of magnitude faster than handcrafted methods) makes it ideal for screening massive polymer spaces [30] [34].

For Data-Limited Scenarios: Handcrafted fingerprints or GNNs demonstrate superior performance when labeled training data is scarce [31].

For Multi-Property Prediction: polyBERT's multitask learning capability effectively harnesses inherent correlations in multi-fidelity and multi-property datasets [30].

For Experimental Validation: PolyID's domain-of-validity method and experimental validation protocol provide greater confidence for synthesis prioritization [35].

For Novel Polymer Discovery: GNNs and polyBERT show better generalization to new polymer chemical classes compared to handcrafted fingerprints [30].

Table 3: Essential Tools for Polymer Informatics Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical operations & fingerprint generation | Open source |

| canonicalize_psmiles | Python Package | Standardizes polymer SMILES representations [30] | Research implementation |

| Huggingface Transformers | NLP Library | Transformer model implementations [30] | Open source |

| POINT2 Database | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized evaluation & benchmarking [31] | Academic use |

| Polymer Genome | Web Platform | Handcrafted fingerprinting & property prediction [33] | Web access |

| CRIPT | Data Platform | Community resource for polymer data sharing [36] | Emerging platform |

| BRICS | Fragmentation Method | Decomposes polymers into chemical fragments [30] | RDKit implementation |

The polymer informatics pipeline has evolved from reliance on handcrafted fingerprints to fully machine-driven approaches that offer unprecedented speed and accuracy. Our comparative analysis demonstrates that transformer-based models like polyBERT currently provide the best balance of speed and accuracy for high-throughput screening, while graph-based approaches like polyGNN and PolyID offer strong performance with greater interpretability.

The future of polymer informatics lies in addressing current challenges around data scarcity, uncertainty quantification, and synthesizability assessment. Frameworks like POINT2 that integrate prediction accuracy, uncertainty quantification, ML interpretability, and synthesizability assessment represent the next evolution in robust, automated polymer discovery [31]. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, they will dramatically accelerate the design and development of novel polymers for applications ranging from drug delivery to sustainable materials.

For researchers implementing these pipelines, selection should be guided by specific project needs: polyBERT for high-speed screening of large chemical spaces, GNNs for complex structure-property relationships, and handcrafted fingerprints for data-limited scenarios. As the field matures, the integration of these approaches with experimental validation will be crucial for realizing the full potential of polymer informatics in accelerating materials discovery.

Proven Techniques and Real-World Applications: Building and Validating Polymer ML Models

In the field of polymer science research, the reliability of machine learning models is fundamentally dependent on the quality of input data. Data preparation presents significant challenges, particularly in handling missing values, detecting outliers, and effectively representing complex polymer structures. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of prevalent methodologies, synthesizing experimental findings from recent studies to establish best practices tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of polymer science and machine learning.

Handling Missing Data: A Comparative Analysis of Imputation Methods

Missing data is a common issue in scientific datasets, and the choice of imputation method can significantly impact the performance of subsequent machine learning models. The following analysis compares various statistical and machine learning-based imputation techniques.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Imputation Methods

To objectively evaluate imputation performance, researchers typically employ a standardized experimental protocol. A complete dataset is first selected, after which missingness is artificially introduced under controlled mechanisms (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) and at specific rates (e.g., 10%, 20%, 50%) [37] [38]. The imputation methods are then applied to reconstruct the dataset. Performance is quantified by comparing the imputed values to the known, original values using metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [37]. The ultimate test involves using the imputed datasets to train a machine learning model (e.g., a Support Vector Machine for predicting cardiovascular disease risk) and comparing the model's performance, often measured by the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve [37].

Quantitative Comparison of Imputation Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of imputation methods on a cohort study dataset (20% missing rate).

| Imputation Method | Category | MAE | RMSE | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Machine Learning | 0.2032 | 0.7438 | 0.730 |

| Random Forest (RF) | Machine Learning | 0.3944 | 1.4866 | 0.777 |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) | Statistical | Information Missing | Information Missing | Comparable to KNN |

| Decision Tree (Cart) | Machine Learning | Information Missing | Information Missing | Comparable to KNN |

| Multiple Imputation (MICE) | Statistical | Information Missing | Information Missing | Lower than KNN/RF |

| Simple Imputation | Statistical | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

| Regression Imputation | Statistical | High | High | Low |

| Cluster Imputation | Machine Learning | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

Table 2: Performance of local-similarity imputation methods in proteomic data (label-free quantification).

| Imputation Method | NRMSE (50% MNAR) | True Positive Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Low | Robust |

| Local Least Squares (LLS) | Low | Robust |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | Moderate | Effective |

| Probabilistic PCA (PPCA) | Varies with log-transform | Moderate |

| Bayesian PCA (BPCA) | Varies with log-transform | Moderate |

| Single Value Decomp (SVD) | Varies with log-transform | Moderate |

Key Findings and Recommendations

- Machine Learning Methods Show Superior Performance: KNN and Random Forest consistently achieve the lowest error rates (MAE, RMSE) and help maintain high predictive model performance (AUC) [37]. In proteomics, RF and LLS are robust across varying missing value scenarios [38].

- Multiple Imputation may be less suitable for ML: Contrary to traditional statistical consensus, one study found that Multiple Imputation (MICE) did not outperform simpler methods in supervised learning and was computationally more demanding [39].

- Consider the Data Type: For proteomic data with a high proportion of MNAR values, local-similarity methods (RF, LLS, kNN) are generally preferred. Global-similarity methods (e.g., SVD, PPCA) can see improved performance after data logarithmization [38].

Handling Outliers: A Comparative Analysis of Detection Algorithms

Outliers can skew model training and lead to inaccurate predictions. Here, we compare the efficacy of several machine learning-based outlier detection algorithms.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Outlier Detection

The evaluation of outlier detection methods often uses a benchmark of "quasi-outliers," defined by statistical thresholds like the 2σ rule (data points beyond two standard deviations from the mean) [40]. Researchers apply algorithms like k-Nearest Neighbour (kNN), Local Outlier Factor (LOF), and Isolation Forest (ISF) to datasets, such as those from flotation processes in mineral beneficiation. The mutual coverage of outliers identified by different methods is analyzed to determine which algorithm provides the most comprehensive detection. The final validation involves training models with and without the detected outliers and comparing the average prediction errors to quantify the impact of outlier removal on model accuracy [40].

Quantitative Comparison of Outlier Detection Methods

Table 3: Comparison of machine learning algorithms for outlier detection.

| Detection Method | Type | Key Principle | Efficacy in Flotation Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-Nearest Neighbour (kNN) | Distance-based | Distance to k-nearest neighbors | Covers outliers detected by other methods |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) | Density-based | Local density deviation from neighbors | Effective for local outliers |

| Isolation Forest (ISF) | Ensemble-based | Isolates anomalies with random partitions | Effective for high-dimensional data |

| Statistical (2σ Rule) | Statistical | Deviation from mean standard deviation | Serves as a benchmark ("quasi-outliers") |

Key Findings and Recommendations

- kNN Provides Broad Coverage: In an industrial flotation data study, the kNN method identified outliers that encompassed those found by other methods, suggesting it may offer the most extensive coverage [40].

- Excluding Outliers Improves Model Accuracy: The study confirmed that training machine learning models on data after the removal of detected outliers resulted in reduced average prediction errors [40].

- Context is Critical: Outliers in complex processes like flotation may not be simple errors but could indicate subtle process deviations. Therefore, detection should be followed by expert investigation to confirm their nature [40].

Polymer Representation for Machine Learning

Effectively representing polymers as structured data is a critical first step in building predictive models for polymer science.

Key Aspects of Polymer Representation

Machine learning applications in polymer science aim to establish quantitative relationships between a polymer's composition, processing conditions, structure, and its final properties and performance [1]. This involves representing complex, multiscale structural characteristics in a numerical format that algorithms can process. High-throughput experimentation is a key enabler, allowing for the systematic accumulation of large, standardized datasets on polymer synthesis and properties, which are essential for training robust ML models [1].

Application in Predictive Modeling

Once represented, this data can be used to train models for various tasks, including predicting the properties of a specified polymer structure or reversely designing structures with targeted functions (e.g., specific thermal, electrical, or mechanical properties) [1]. This data-driven approach helps uncover intricate physicochemical relationships that have traditionally been challenging to decipher.

Visualizing Data Preparation Workflows

The following diagrams outline standardized workflows for handling missing data and outliers, integrating the best practices derived from the comparative analysis.

Workflow for Handling Missing Data

Workflow for Handling Outliers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key computational tools and methodologies referenced in the experimental studies, which are essential for implementing the data preparation protocols outlined in this guide.

Table 4: Key research reagents and computational solutions for data preparation.

| Tool/Solution | Category | Function in Data Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Imputation Algorithm | Estimates missing values based on similar samples using distance metrics (e.g., Euclidean) [37]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Imputation Algorithm | Uses an ensemble of decision trees to predict and impute missing values [37] [38]. |

| Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) | Imputation Algorithm | Creates multiple imputed datasets to account for uncertainty in missing values [37]. |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) | Outlier Detection Algorithm | Identifies outliers by comparing the local density of a point to the densities of its neighbors [40]. |

| Isolation Forest (ISF) | Outlier Detection Algorithm | Isolates outliers by randomly selecting features and splitting values; anomalies are easier to isolate [40]. |

| Simple Imputer (Mean/Median/Mode) | Baseline Imputation | Provides a simple baseline by replacing missing values with a central tendency measure [37] [41]. |

| GridSearchCV | Model Selection Tool | Automates the search for the best imputation strategy and model hyperparameters via cross-validation [42]. |

| Tecovirimat | Tecovirimat, CAS:869572-92-9, MF:C19H15F3N2O3, MW:376.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Temocaprilat | Temocaprilat, CAS:110221-53-9, MF:C21H24N2O5S2, MW:448.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the evolving field of polymer informatics, the transition from chemical structures to machine-readable descriptors represents a fundamental bottleneck governing the accuracy and generalizability of predictive models. Feature engineering—the process of transforming raw chemical representations into meaningful numerical vectors—serves as the critical bridge connecting polymer chemistry with machine learning algorithms. Within the context of validating machine learning models for polymer science, the selection of appropriate feature encoding strategies directly controls a model's capacity to capture complex structure-property relationships, avoid overfitting, and extrapolate beyond training data distributions.

Traditional polymer design relying on empirical approaches and intuitive experimentation faces significant challenges in navigating the vast chemical space of possible monomer combinations, backbone architectures, and sidechain functionalities. The emergence of standardized digital representations like Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings and their polymer-specific variants (PSMILES) has enabled computational screening of polymer libraries. However, the conversion of these string-based representations into informative descriptors remains non-trivial, with different featurization strategies embodying distinct trade-offs between interpretability, information content, and computational efficiency.

This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary feature engineering methodologies through the lens of experimental validation, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate descriptor schemes based on specific research objectives, available data resources, and target polymer properties.

Fundamental Polymer Representations: From Chemical Structures to Digital Descriptors

String-Based Representations: SMILES and Beyond

The foundation of digital polymer chemistry begins with string-based representations that encode molecular structures in text format. The SMILES notation has emerged as a widely adopted standard, representing molecular graphs as linear strings of characters denoting atoms, bonds, branches, and ring structures. For polymers, specialized extensions like big-SMILES and PSMILES have been developed to address the repetitive nature and stochastic sequencing of macromolecular systems [43] [44]. These representations serve as the primary input for most feature engineering pipelines, with their syntax providing a compact, storage-efficient format for chemical structures.

The Featurization Landscape: Categories of Polymer Descriptors

The conversion of string representations to numerical descriptors occurs through multiple conceptual frameworks, each capturing distinct aspects of polymer chemistry:

- Chemical Descriptors: Quantify compositional attributes including heteroatom counts, ring structures, rotatable bonds, and hybridization states, which directly influence intermolecular interactions and bulk properties [43].

- Topological Descriptors: Encode structural connectivity patterns, such as sidechain branching density, backbone atom counts, and molecular flexibility parameters, which correlate with chain packing efficiency and dynamic behavior [43].

- Fingerprint-Based Descriptors: Binary vectors indicating the presence or absence of specific molecular substructures or functional groups, with Morgan fingerprints (also known as circular fingerprints) being particularly prevalent in polymer informatics [43] [44].

- Hierarchical Descriptors: Emerging approaches that separately characterize backbone, sidechain, and full polymer attributes, enabling targeted feature engineering for specific structure-property relationships [43].

- Learned Representations: Dense numerical vectors generated by neural network models like PolyBERT that capture complex chemical patterns through self-supervised learning on large unlabeled polymer datasets [43] [45].

Comparative Analysis of Feature Engineering Methodologies

Performance Benchmarking Across Descriptor Schemes

Experimental validation across multiple independent studies provides quantitative insights into the relative performance of different featurization strategies. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics from published benchmarks:

Table 1: Performance comparison of polymer descriptor schemes on benchmark tasks

| Descriptor Category | Specific Method | Prediction Accuracy (Typical R²/RMSE) | Computational Efficiency | Interpretability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Morgan Fingerprints | 0.72-0.85 (varies by property) [43] | High | Medium | High-throughput screening, classification [43] [44] |

| Traditional Chemical | RDKit 2D/3D Descriptors | 0.70-0.82 (varies by property) [46] | Medium-High | High | Structure-property analysis, QSPR [46] |

| Hierarchical | PolyMetriX Featurization | ~10% improvement over Morgan in generalization tests [43] | Medium | High | Backbone/sidechain analysis, robust extrapolation [43] |

| Learned Representations | PolyBERT | Superior to Morgan in low-similarity scenarios [43] | Low (training) / Medium (inference) | Low | Transfer learning, multi-task prediction [43] |

| Hybrid Approaches | 1DCNN-GRU with SMILES | 98.66% classification accuracy [47] | Medium | Medium | Sequence-property relationships, end-to-end learning [47] |

The SMILES-PPDCPOA framework, which integrates a one-dimensional convolutional neural network with gated recurrent units (1DCNN-GRU) for direct SMILES processing, demonstrates exceptional classification performance—achieving 98.66% accuracy across eight polymer property classes while completing tasks in just 4.97 seconds of computational time [47]. This hybrid architecture captures both local molecular substructures through convolutional operations and long-range chemical dependencies via recurrent connections, offering a balanced approach between structural sensitivity and computational practicality.

Specialized Architectures for Advanced Applications

Beyond conventional featurization approaches, specialized architectures have emerged to address particular challenges in polymer informatics:

Periodicity-Aware Learning: The PerioGT framework incorporates polymer-specific periodicity priors through contrastive learning, achieving state-of-the-art performance on 16 downstream tasks including the identification of polymers with potent antimicrobial properties [19]. This approach demonstrates that domain-informed architectural biases can significantly enhance generalization compared to generic molecular representations.